Abstract

Background

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is common in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and is associated with a worse prognosis. Mechanical ventilation has been identified as a risk factor for renal damage in COVID-19. However, few studies have examined the specific ventilatory settings involved. We hypothesized that positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) may contribute to the onset of AKI. Our primary objective was to assess the relationship between PEEP levels and the development of AKI in critically ill patients with COVID-19-related ARDS.

Methods

We conducted an ancillary analysis of the international, prospective, multicenter COVID-ICU study, which included 4244 COVID-19 ICU patients across 149 intensive care units. For our study, only patients who underwent mechanical ventilation for at least 48 h and had normal renal function before intubation were included. The primary outcome was AKI, defined according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association between PEEP levels and the development of AKI (KDIGO score > 1).

Results

A total of 1,066 patients were included in the analysis. Among them, 510 (48%) developed AKI within the first 5 days after intubation. After multivariable adjustment, higher daily mean PEEP levels, averaged over the first 3 days of mechanical ventilation and treated as a continuous variable, were independently associated with the development of AKI (odds ratio [OR] 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.16). A PEEP level exceeding 15.2 cmH2O was significantly associated with the occurrence of AKI.

Conclusion

In patients with COVID-19-related ARDS patients, higher PEEP levels within the first 5 days after intubation were independently associated with AKI. These findings underscore the importance of ventilatory strategies to balance oxygenation and kidney protection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40560-025-00831-w.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Positive end-expiratory pressure, Mechanical ventilation, COVID-19, Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) profoundly impacted ICUs worldwide between 2020 and 2021, mainly through its severe form characterized by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1]. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is the most frequent organ failure associated with ARDS, occuring in 30–40% of patients [2] and in more than 50% of those with COVID-19 [3]. The onset of renal dysfunction is a well-established risk factor for mortality in ARDS, whether linked to SARS-CoV-2 [4] or not [2]. Moreover, AKI contributes to greater morbidity by prolonging mechanical ventilation [2], extending ICU and hospital stays, and increasing the risk of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease [5].

The pathophysiology of renal damage in ARDS remains incompletely understood [3]. Several studies have identified mechanical ventilation as an independent risk factor for AKI in ARDS [6], particularly in COVID-19 cases [7]. PEEP may contribute to renal dysfunction through hemodynamics mechanisms: elevated intrathoracic pressure can reduce venous return and cardiac output [3, 8, 9] while increased transpulmonary pressure may raise pulmonary vascular resistance and right-ventricular afterload [8, 10], promote venous congestion, and lower renal perfusion pressure [11]. In parallel, neurohormonal activation [12] and systemic inflammation [13] may disturb renal physiology.

Despite these pathophysiological concerns, PEEP also provides pulmonary benefits, including alveolar recruitment (counteracting derecruitment induced by low tidal volume protective ventilation), improved oxygenation and lung mechanics [14], and reduced cyclic opening/closing (atelectrauma) [15]. These benefits form the rationale for high-PEEP strategies in ARDS and may partly offset the potential risk of renal dysfunction. However, as highlighted by Gattinoni and Grasselli [16, 17], COVID-19–related ARDS shows marked heterogeneity in respiratory mechanics, with a non-negligible subset of patients retaining respiratory-system compliance > 50 mL·cmH2O⁻1 despite severe hypoxemia. In these less-recruitable phenotypes, increasing PEEP may provide limited ventilatory benefit while imposing greater hemodynamic burden and, potentially, harmful inflammatory effects [18]. A few small observational studies in COVID-19 reported inconsistent associations between PEEP and renal function [19–22].

We therefore hypothesized that higher PEEP levels may have a deleterious effect on renal function. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether PEEP levels were associated with the occurrence of AKI in patients with COVID-19–related ARDS. The secondary objectives were (i) to identify factors associated with 28-day mortality, and (ii) to perform a sensitivity analysis of the association between PEEP and AKI restricted to KDIGO stage 2–3, which are less prone to misclassification.

Methods

Study design, data source and patients

This study is an ancillary analysis of the COVID-ICU cohort [23], conducted between February 25, 2020 and May 4, 2020 during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-ICU cohort is a multicenter, prospective study conducted across 149 intensive care units (ICUs) in 138 hospitals across 3 countries (France, Switzerland and Belgium). It includes 4,244 patients aged over 16 years admitted to the ICU with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In this analysis, Day 1 was defined as the first day of mechanical ventilation for each patient. Only those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation for at least 48 h were included. Exclusion criteria comprised: patients who had received RRT or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) on Day 1 or earlier; those without daily PEEP values during the first 3 days of mechanical ventilation; patients mechanically ventilated for more than 24 h before ICU admission; those without creatinine data on Day 1; patients with chronic kidney disease; and those with renal dysfunction as indicated by the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score on Day 1.

Case definition

Renal function was assessed using the KDIGO classification [24] based solely on biological and RRT criteria, as daily urine output and prior creatinine values were not collected. Baseline creatinine was estimated, in accordance with guidelines [24], by back-calculation [25] of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula, assuming a baseline glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 75 ml/min/1.73 m2 for patients without chronic kidney disease (CKD). The maximum creatinine value and/or the use of RRT within the first 5 days following intubation (i.e., from Day 2 to Day 6) were used to define patients into two groups, using the KDIGO criteria for AKI: those who developed AKI within the first 5 days following intubation, and those who retained normal renal function. Patients who died before Day 6 without meeting KDIGO criteria for AKI were classified as not having AKI. The severity of renal dysfunction was further categorized according to the KDIGO stages. The severity of ARDS was assessed using the PaO2/FiO2 ratio and the Berlin criteria [1]. Ventilator-free days were calculated by taking into account the date of intubation and the date of successful extubation, excluding periods of temporary weaning. In the case of death within 28 days, the patient was considered to have no ventilator-free days.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) within the first 5 days following intubation, defined according to the KDIGO classification (any stage ≥ 1). Secondary outcomes included: (i) 28-day mortality, evaluated using a multivariable logistic regression model with prespecified adjustment covariates; (ii) a sensitivity analysis, in which AKI was redefined as KDIGO stage 2–3 only, as these stages are less prone to diagnostic uncertainty. This allowed us to test the robustness of the observed association between PEEP and renal outcomes.

Data collection

All data were recorded daily at 10 a.m. by the study investigators using a standardized electronic form. Patient characteristics collected at ICU admission included sex, age, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), active smoking status, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, bacterial co-infection, and comorbidities, including chronic kidney disease. Ventilator settings (FiO2, tidal volume, total PEEP, plateau pressure, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio); respiratory biomarkers (arterial blood gases, lactate levels); hemodynamic parameters (cumulative fluid balance, number of days on vasopressors, presence of right ventricular dysfunction) and rescue therapies (number of days in prone positioning and on inhaled nitric oxide) were collected and averaged across Days 1–3. Prognostic data included ARDS severity on Day 1, renal function and/or use of renal replacement therapy within the first 5 days, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, and ICU length of stay.

Ethical approval

The ethics committees of Switzerland (BASEC #: 2020-00704), the French Intensive Care Society (CE-SRLF 20–23), and Belgium (2020-294) approved the data collection protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysis

Data imputation

To account for missing values, we performed multiple imputation using the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) algorithm. This approach generates multiple plausible datasets by imputing missing data based on observed values while incorporating uncertainty through iterative regression modeling. Predictive mean matching (PMM) was used for continuous variables, and logistic or polytomous regression was applied for categorical variables. We generated five imputed datasets, a number commonly used in clinical research and adequate given moderate proportion of missing data. Although a larger number of imputations (e.g., 20) may further reduce Monte Carlo error, the results were stable across imputations, and combining five datasets using Rubin’s rules ensured valid statistical inference.

Multivariable logistic regression for acute kidney injury

A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to identify factors associated with the development of acute kidney injury (AKI). The explanatory variables were selected a priori based on clinical relevance and previous literature [3, 26–28] and included: (i) Demographics (age, sex, body mass index); (ii) Comorbidities notably cardiovascular history (hypertension, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure or diabetes); (iii) Organ support and severity markers during the first 3 days (PEEP, vasopressor use, lactate, tidal volume per predicted body weight, PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, driving pressure (ΔP), and Fluid balance).

Multivariable logistic regression for 28-day mortality

A second logistic regression model was built with 28-day mortality as the dependent variable. Adjustment covariates included: PEEP (day 1–3), age, sex, BMI, cardiovascular history, vasopressor use (day 1–3), initial ARDS severity, and the presence of AKI (within the first 5 days following intubation). Nonlinear associations with PEEP were similarly tested and visualized using restricted cubic splines.

Assessment of linearity and nonlinear modeling and visual representation of nonlinear effects

The linearity assumption of PEEP in the logit scale was formally evaluated in the multivariable logistic regression models for both acute kidney injury and 28-day mortality. Model fit was assessed by comparing linear and spline-based specifications using likelihood ratio tests, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). To illustrate the nonlinear effect of PEEP, adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated across the full range of PEEP values based on spline-predicted models. For graphical representation, all other covariates were fixed at their median (continuous variables) or most frequent category (categorical variables). The threshold was defined as the PEEP level at which the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the adjusted odds ratio exceeded 1, indicating a statistically significant increase in AKI or 28-day mortality.

Sensitivity analysis using severe AKI definition

To minimize potential misclassification bias related to mild AKI, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by restricting the AKI definition to KDIGO stages 2–3. The multivariable logistic regression was rerun with this outcome definition.

Sensitivity analysis excluding patients dying early after intubation

To ensure that our classification of patients who died within 5 days after intubation as not having acute kidney injury did not introduce bias, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients who survived at least 5 days after intubation. The multivariable logistic regression was then repeated with this revised outcome definition.

Software and data representation

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation), while categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages). Group comparisons were performed using the Student's t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. All analyses were performed using R v.4.3.0.

Results

Study population

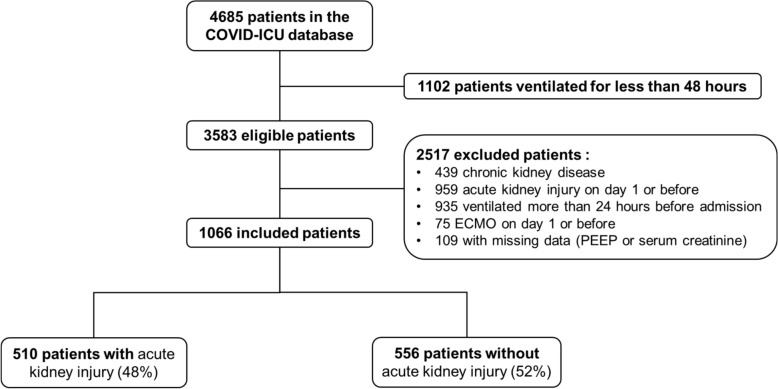

Of 3583 patients ventilated for at least 48 h, 1066 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Patients were predominantly male (73%), overweight (mean BMI 29 ± 6), with a mean age of 61 ± 12 years. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics at admission

| Total population | With AKI (n = 510) | Without AKI (n = 556) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61 ± 12 | 62 ± 12 | 61 ± 12 | 0.307 |

| Male sex | 780 (73) | 369 (72) | 411 (74) | 0.611 |

| BMI | 29 ± 6 | 29 ± 6 | 29 ± 6 | 0.927 |

| SAPS II | 40 ± 15 | 41 ± 16 | 39 ± 15 | 0.029 |

| No antecedents | 217 (20) | 93 (18) | 124 (22) | 0.116 |

| Active smoking | 29 (3) | 15 (3) | 14 (3) | 0.814 |

| Respiratory history | 202 (19) | 106 (21) | 96 (17) | 0.166 |

| COPD | 53 (5) | 27 (5) | 26 (5) | 0.747 |

| Asthma | 76 (7) | 40 (8) | 36 (6) | 0.454 |

| Cardiovascular history | 586 (55) | 288 (56) | 298 (54) | 0.379 |

| Hypertension | 454 (43) | 230 (45) | 224 (40) | 0.127 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 95 (9) | 42 (8) | 53 (9) | 0.525 |

| Congestive heart failure | 22 (2) | 14 (3) | 9 (2) | 0.292 |

| Diabetes | 249 (23) | 134 (26) | 115 (20) | 0.037 |

| Immunodepressiona | 91 (9) | 49 (10) | 42 (8) | 0.276 |

| Bacterial co-infection | 62 (6) | 28 (6) | 34 (6) | 0.761 |

The data are presented in numbers and percentages (%) or as mean ± standard deviation

AKI acute kidney injury failure, BMI body mass index, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SAPS II simplified acute physiology score II

aincludes: long-term immunosuppressive medications and/or corticosteroids, HIV infection, solid organ transplantation, active solid or hematological cancer

Acute kidney injury: incidence, morbidity and mortality

Of the 1066 patients, 510 (48%) developed acute kidney injury within the first 5 days after intubation. Diabetes was more prevalent in the AKI group (26 vs 20% in the non-AKI group, p = 0.037) (Table 1). The majority (61%) of AKI cases remained at KDIGO stage 1, while 19% progressed to stage 3, and 10% required RRT. Patients with AKI had higher 28-day mortality (28% vs. 19%, p = 0.001), a longer ICU stay (30 ± 18 vs. 24 ± 18 days, p < 0.001), and fewer ventilator-free days (7 ± 8 vs. 12 ± 9, p < 0.001) compared to those without AKI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prognosis and severity of acute kidney injury

| Total population | With AKI (n = 510) | Without AKI (n = 556) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial severity of ARDS at day 1a | 0.069 | |||

| Mild | 304 (29) | 140 (28) | 164 (30) | – |

| Moderate | 475 (45) | 216 (42) | 259 (47) | – |

| Severe | 287 (27) | 154 (30) | 133 (24) | – |

| Tidal volume, ml/kg of IBW at day 1 | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 0.644 |

| Static compliance, ml/cmH20 at day 1b | 36 (18) | 36 (17) | 36 (19) | 0.838 |

| Kidney function: | ||||

| Basal creatininec | 54 ± 15 | 53 ± 17 | 55 ± 14 | 0.105 |

| Severity of AKI from day 2 to 6 | ||||

| KDIGO 1 | 314 (29) | 314 (61) | – | – |

| KDIGO 2 | 98 (9) | 98 (19) | – | – |

| KDIGO 3 | 98 (9) | 98 (19) | – | – |

| RRT from day 2 to 6 | 54 (5) | 54 (10) | – | – |

| Prognosis: | ||||

| Mortality at 28 dayd | 252 (24) | 144 (28) | 108 (19) | 0.001 |

| Ventilator-free dayse | 10 ± 9 | 7 ± 8 | 12 ± 9 | < 0.001 |

| ICU length of stay | 26 ± 18 | 30 ± 18 | 24 ± 18 | < 0.001 |

Data are presented in numbers and percentages (%) or mean ± standard deviation

AKI acute kidney injury, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU Intensive Care Unit, MV mechanical ventilation, RRT renal replacement therapy

aaccording to Berlin criteria

bcalculated with static compliance = tidal volume / driving pressure

ccalculated using the formula:

d31 lost to follow-up not included in this table

etime between date of intubation and last successful extubation

Respiratory and hemodynamic parameters

Compared to patients without AKI, PEEP was significantly higher in the AKI group (11.4 ± 2.7 vs 10.8 ± 2.6 cmH2O, p < 0.001). Static lung compliance was similar in both groups (36.7 ± 17.4 vs 37.6 ± 18.4 ml/cmH2O, p = 0.413) while pH was lower (7.39 ± 0.06 vs 7.40 ± 0.05, p < 0.001) and lactate was higher (1.6 ± 0.9 vs 1.4 ± 0.7 mmol/L, p < 0.001) in the AKI group. From a hemodynamic perspective, patients with AKI required more days on vasopressors (1.8 ± 1.2 vs 1.6 ± 1.2 days, p < 0.03) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean respiratory and hemodynamic parameters from day 1 to day 3

| With AKI | Without AKI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory parameters | |||

| PEEP, cmH20 | 11.4 ± 2.7 | 10.8 ± 2.6 | < 0.001 |

| Tidal volume, ml/kg of IBW | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 0.387 |

| Plateau pressure, cmH20 | 24.4 ± 4.3 | 23.8 ± 34.2 | 0.021 |

| Driving pressure, cmH20a | 13.1 ± 4.0 | 12. ± 3.8 | 0.097 |

| Static compliance, ml/cmH20b | 36.7 ± 17.4 | 37.6 ± 18.4 | 0.413 |

| Blood gases | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 | 176 ± 66 | 180 ± 67 | 0.255 |

| pH | 7.39 ± 0.06 | 7.40 ± 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 45.0 ± 10.0 | 44.3 ± 8.3 | 0.169 |

| Bicarbonates, mmol/l | 26.3 ± 3.6 | 26.9 ± 3.3 | 0.002c |

| Lactate, mmol/l | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Rescue therapy | |||

| Number of days in PP | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.427 |

| Number of days NO | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.740 |

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||

| Number of days vasopressorsc | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.003 |

| RV dysfunction over 3 days, N (%)d | 22 (4) | 13 (2) | 0.102 |

| 24-h fluid balance (ml) | 1295 ± 903 | 1163 ± 768 | 0.010 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or numbers and percentages (%)

AKI acute kidney injury, PEEP positive expiratory pressure, IBW ideal body weight, PaO2/FiO2 arterial partial pressure of oxygen on fraction inspired in oxygen, PaCO2 arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, PP prone position, NO inhaled nitric oxide, RV right ventricle

a calculated with driving pressure = plateau pressure—total PEEP

b calculated with static compliance = tidal volume/driving pressure

c a Student's t test has been performed here

d if trans-thoracic ultrasound was performed

Risk factors associated with acute kidney injury

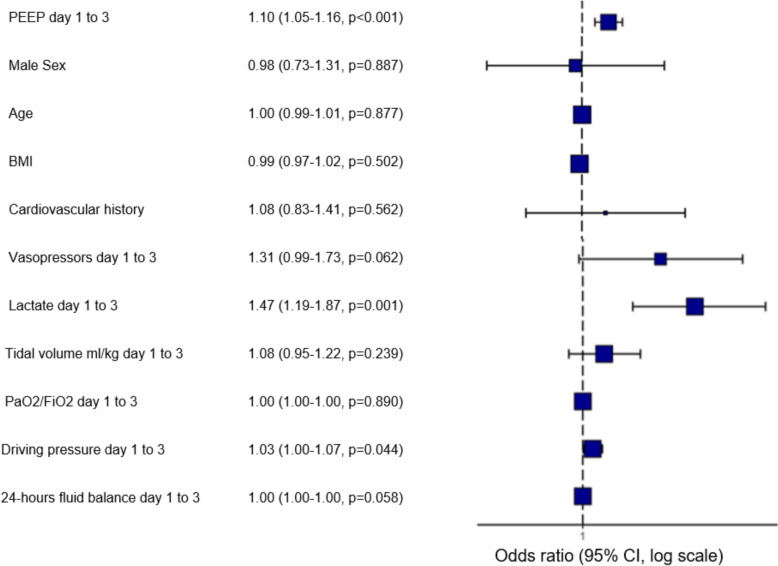

After adjusting for confounding factors, PEEP was significantly associated with the development of AKI within the first 5 days following intubation (odds ratio [OR] 1.10; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.05–1.16). The elevated lactate levels (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.19–1.87) and ΔP (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.00–1.07) were also significantly associated with AKI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Multivariable analyse of factors associated with AKI assessed within the first five days following intubation– PEEP in continuous variable

Risk factors associated with mortality at 28 days

In a multivariable analysis adjusted for mortality risk factors, the level of PEEP was not associated with 28-day mortality (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.94–1.06). However, the occurrence of AKI within the first 5 days following intubation was associated with increased mortality at 28 days (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.16–2.09), as well as the age (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02–1.05) and a “severe” ARDS at day 1 (OR 1.63; 95% CI 1.11–2.40) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Multivariable analyse of factors associated with mortality at day 28

Assessment of linearity and nonlinear modeling and visual representation of nonlinear effects

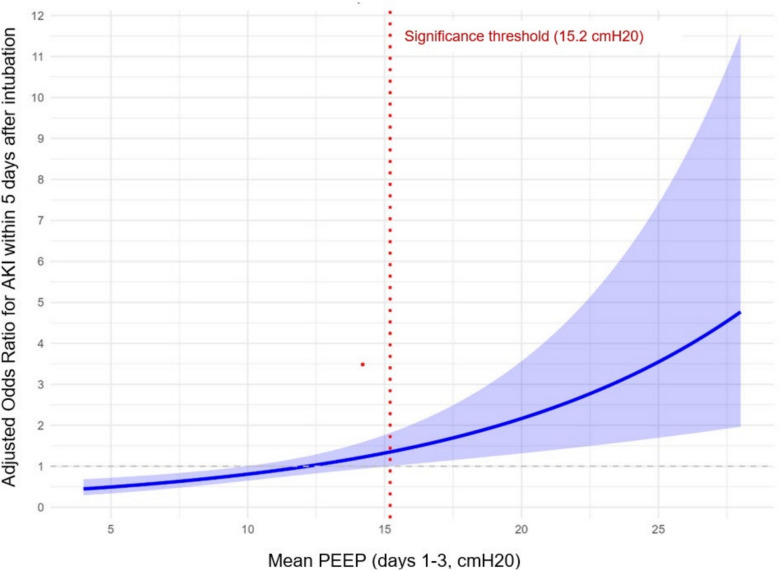

In the analysis of risks factors associated with AKI, the linear logistic regression model provided the best balance between fit and parsimony, with lower AIC (1453 vs. 1465) and BIC (1513 vs. 1605) values, although the spline model achieved a slightly higher log-likelihood (− 704 vs. − 715). However, the spline-based graphical representation suggested that beyond a PEEP level of 15.2 cmH₂O, there was a significant association between higher PEEP exposure and the occurrence of AKI (Fig. 4). For 28-day mortality, the linear model was again favored over the spline model, with lower AIC (1128.9 vs. 1130.4) and BIC (1178.6 vs. 1209.9), despite a marginally higher log-likelihood for the spline model (− 549 vs. − 554). Unlike in the AKI analysis, spline-based graphical representation did not show any significant association between PEEP exposure and mortality (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Nonlinear graphical depiction of the association between PEEP and AKI

Fig. 5.

Nonlinear graphical depiction of the association between PEEP and mortality at day 28

Sensitivity analysis using severe AKI definition

When AKI was defined as KDIGO stage 2 or 3 and models were adjusted for confounding factors, PEEP was associated with the development of AKI, although this association did not reach statistical significance (odds ratio [OR] 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.13) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Likewise, the spline-based graphical analysis indicated an increased risk of AKI with higher PEEP levels, but without identifying a significant threshold (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, elevated lactate levels (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.01–1.42) and increased ΔP (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.03–1.11) were both significantly associated with AKI (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Sensitivity analysis excluding patients dying early after intubation

When restricting the analysis to patients who survived at least 5 days after intubation, PEEP remained statistically significantly associated with the development of AKI within the first 5 days (odds ratio [OR] 1.11; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.16) after adjustment for confounders. Elevated lactate levels were also independently associated with AKI (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.18–1.90) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The spline-based graphical analysis also indicated that PEEP levels above 14.8 cmH₂O were significantly associated with an increased risk of AKI (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this ancillary study from a large international cohort of critically ill COVID-19 patients, 48% of mechanically ventilated patients developed de novo AKI within the first 5 days after intubation. Higher PEEP levels during the first 72 h were independently associated with AKI onset (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.05–1.16). PEEP > 15.2 cmH₂O was significantly associated with increased odds of AKI. Elevated lactate levels also associated with renal dysfunction. AKI was independently associated with higher 28-day mortality (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.16–2.09), but no significant link was found between PEEP levels and mortality (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.94–1.06).

PEEP has traditionally been set at a high level in patients with ARDS. In our cohort of COVID-19-related ARDS, mean PEEP levels during the early days of mechanical ventilation were 11.4 ± 2.7 cmH2O, reflecting standard clinical practice. While three major randomized trials have shown that high PEEP enhances oxygenation in ARDS patients [14, 29, 30], none—including our study—have demonstrated a mortality benefit. This discrepancy may be due to the underexplored adverse effects of high PEEP on extrapulmonary organs.

In this large cohort, after adjustment for multiple confounders, each 1 cmH₂O increase in PEEP was associated with a 10% higher odds of AKI. Given the high incidence of AKI (48%), odds ratios may overestimate risk ratios; thus, our estimates should be interpreted as odds, not risk. Using a spline-based graphical representation, we found that beyond a PEEP level of 15.2 cmH₂O, the risk of developing AKI was significantly increased. Our findings reinforce and extend prior literature on COVID-19, such as a secondary analysis of a Dutch multicenter cohort involving 468 patients [22] and an Italian case–control study involving 101 patients [19], both of which reported an association between PEEP and AKI with 1.5 to fivefold higher AKI in the high PEEP groups, respectively. Observational studies, including before-and-after observational studies [21, 31], have also suggested a positive relationship between PEEP and AKI. In the context of ARDS unrelated to COVID-19, only a retrospective study involving 27,248 patients from the MIMIC-III cohort [32] has demonstrated a similar association between increased PEEP and AKI, with each 1 cmH20 increase in PEEP associated with a roughly 1.2-fold increased risk of AKI. However, this result contrasts with other large-scale observational studies that failed to demonstrate this association in ARDS unrelated to COVID-19 [2, 27, 33].

Several factors may explain this discrepancy between COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ARDS studies. First, non-COVID-19 cohorts often include a heterogeneous range of ARDS etiologies and phenotypes [34]. Depending on the phenotype, patients respond differently to PEEP in terms of pulmonary recruitability [34–36]. The hemodynamic consequences of PEEP are inversely correlated with this recruitability [10, 37]. Some patients with higher pulmonary recruitability experience little or no hemodynamic effects from PEEP. Consequently, the association between PEEP and AKI is less pronounced in studies involving heterogeneous populations. In the context of COVID-19, although different ARDS phenotypes have been described [38], the study populations remain relatively homogeneous. Secondly, it has been noted that patients with COVID-19-related ARDS tend to have preserved pulmonary compliance [16, 17]. This may amplify the hemodynamic effects of high PEEP in this population as suggested by Grasso et al. [18] potentially leading to impaired renal blood flow [39] and reduced oxygen delivery to renal tissues [40]. Again according to Grasso et Al. [18] high PEEP in the context of preserved compliance could generate greater alveolar overdistension, thus increasing the systemic release of inflammatory mediators, which also affect renal physiology [13]. However, our study did not find any significant difference in pulmonary compliance between patients with and without AKI. Furthermore, the average compliance (36.6 ml/cmH20) was consistent with values observed in both non-COVID ARDS and other studies involving COVID-19-related ARDS [41, 42].

From a pathophysiological standpoint, it is noteworthy that right ventricular dysfunction, a potential mechanism linking PEEP and AKI in COVID-19, was observed less frequently in our cohort (3.2%) compared to non-COVID-19-related ARDS [43]. This almost certainly reflects under-ascertainment due to the lack of systematic echocardiographic screening and the limited time available during the epidemic surge, rather than a truly low prevalence in this critically ill population.

Elevated blood lactate levels were also independent predictors of AKI. This finding reflects overall severity of illness and have been identified as risk factor for AKI in other studies [2, 44]. Consistent with previous reports in the literature [4, 23, 26, 45] our analysis also underscores that AKI is a strong predictor of increased mortality in COVID-19 patients requiring mechanical ventilation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to establish an independent and temporal association between PEEP and AKI in COVID-19. We specifically observed the effect of PEEP during the first 72 h, as most studies on the topic [14, 29, 30]. Additionally, to account for other confounding factors that might arise between the exposure period and the occurrence or non-occurrence of AKI, we limited the observation of AKI to the period between day 2 and day 6. This approach ensured sufficient PEEP exposure for the potential development of AKI, while avoiding the misclassification of later AKI (after day 6) that is unlikely to be physiologically related to early PEEP levels. Thus, our study introduces a critical temporal element, which is often missing in other observational studies. This finding reinforces the association, as highlighted in previous editorials [46, 47]. Only Géri et al. in 2021 [7] have conducted a similar analysis with comparable results, albeit with a much smaller sample of non-COVID-related ARDS.

However, the positive association between PEEP and AKI should be interpreted with caution. Interestingly, while higher PEEP levels were independently associated with AKI, and AKI was strongly associated with increased 28-day mortality, PEEP itself was not directly related to mortality. Although AKI may partially mediate the relationship between PEEP and death, we included it in the mortality model because of its multifactorial determinants and strong association with mortality, to reduce residual confounding. Several explanations may account for this apparent paradox. First, the beneficial pulmonary effects of higher PEEP on lung mechanics and oxygenation—which may reduce mortality—may have been offset by renal adverse effects, yielding a neutral net effect on survival. Second, residual confounding by indication cannot be excluded: patients receiving higher PEEP were often those with more severe ARDS, which may have masked a direct effect of PEEP on mortality despite adjustment. Finally, it should be noted that in our cohort the majority of AKI cases were mild (61% at KDIGO stage 1) and therefore potentially reversible [48]. Such minor forms of AKI may increase incidence but not necessarily translate into excess mortality [49]. This interpretation is further supported by our sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1), which showed that the association between higher PEEP levels and AKI was no longer significant when restricting the outcome to KDIGO stage 2–3, the stages more likely to contribute to excess mortality. Additionally, insufficient PEEP may lead to significant lung derecruitment and atelectasis, increasing pulmonary arterial pressure, as demonstrated in both animal models [50] and clinical studies [37]. Taken together, these findings highlight the complexity of the relationship between PEEP, AKI, and outcomes. Therefore, an individualized PEEP and driving pressure strategy is crucial to balance its beneficial effects on ventilation while minimizing the risk of AKI. Nevertheless, our study highlights the importance of individualized monitoring and adjustment of driving pressure to reduce the risk of severe AKI in certain patients. While PEEP represents the applied end-expiratory pressure, ΔP directly reflects the interaction between tidal volume and respiratory system compliance. As previously demonstrated, driving pressure is a more accurate marker of lung stress and strain than PEEP, particularly in patients with reduced compliance and high mortality risk [51–53]. In our cohort, the association of ΔP—but not PEEP—with severe AKI (KDIGO stage 2–3) suggests that ΔP is likely a better indicator of injurious mechanical load on renal function in these patients.

Our study has several limitations that must be underlined. First, being an observational study causality cannot be conclusively established. Second, the large sample size and high clinical activity during the COVID-19 crisis led to missing data, which may have obscured additional confounding factors. Although data imputation methods were employed, these limitations should be considered. Despite prespecified adjustment for clinically relevant covariates, our multivariable logistic regression cannot account for unmeasured or unknown confounders. In addition, to minimize overadjustment and multicollinearity, we deliberately did not include pairs of closely related ventilatory variables in the same model (e.g., driving pressure and plateau pressure or PaO2/FiO2 ratio; vasopressors use and SOFA score), opting instead for a parsimonious specification centered on PEEP with core mechanics surrogates. This approach reduces variance inflation but may leave residual confounding by ventilatory mechanics or hemodynamic factors. Third, the mortality rate in our cohort (23%) was lower than that reported in the original COVID-ICU study or in the large "Lung Safe" study [54] partly to the exclusion of patients on ECMO, those with chronic kidney disease or with pre-existing renal dysfunction. These exclusions were made to focus on de novo AKI and to limit confounding factors. While this approach improves internal validity for the specific question of AKI, it may have introduced selection bias and therefore limits the generalizability of our findings. In particular, by excluding patients at highest baseline risk for both severe ARDS and AKI, it is plausible that the association we observed between PEEP and AKI actually underestimates the true effect in a broader, more heterogeneous ICU population. Consequently, the reported odds ratios should be interpreted as applying to a selected population without baseline renal dysfunction; extrapolation to all mechanically ventilated ICU patients should be done with caution.

Fourth, baseline creatinine was imputed using the MDRD back-calculation method, which, although validated [25], remains controversial and may have overestimated AKI incidence by about 10% [55]. Conversely, the non-use of the urine output criterion in the KDIGO classification, although also validated [56], may underestimate the incidence of AKI by approximately 15% [3, 57]. This bidirectional misclassification is particularly relevant for KDIGO stage 1 AKI, where small variations in creatinine or urine output largely drive classification. As a result, some patients may have been incorrectly classified as having or not having mild AKI, introducing uncertainty into the precise incidence of AKI. When restricting the outcome definition to more severe forms of AKI (KDIGO stages 2 and 3 only), which are less subject to misclassification, the association between higher PEEP levels and AKI was no longer statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 1). This finding further underlines the severe limitation related to potential misclassification. However, this result should be interpreted with caution, as the sensitivity analysis was underpowered due to the relatively small number of patients who developed severe AKI: n = 196 (38.4%). Fifth, classifying patients who died within 5 days after intubation as not having AKI may have introduced a misclassification bias. To address this concern, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients who survived at least 5 days, which produced results in line with the main analysis. These consistent findings support our methodological choice, as it minimizes the risk of overestimating the incidence of AKI.

Finally, only one daily PEEP measurement was recorded at 10 am and averaged over the first 3 days. Since PEEP is frequently adjusted throughout the day in response to oxygenation, hemodynamics, or prone positioning, this snapshot may not fully capture cumulative PEEP exposure over 72 h. This limitation may have introduced bias in the assessment of exposure. More dynamic or continuous PEEP measurements would be preferable to better capture the true exposure.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that higher PEEP levels are independently associated with AKI in patients with COVID-19–related ARDS. This highlights the need for clinicians to carefully balance the renal risks of elevated PEEP against its benefits for oxygenation. Prospective clinical trials are now required to validate these results and to establish evidence-based recommendations for PEEP management in COVID-19-related ARDS.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1. Figure 1 Multivariable analyse of factors associated with AKI (KDIGO stages 2–3) assessed within the first five days following intubation– PEEP in continuous variable. Figure 2 Nonlinear graphical depiction of the association between PEEP and AKI (KDIGO stages 2–3). Figure 3 Multivariable analysis of factors associated with AKI within the first five days following intubation in patients surviving at least 5 days post intubation– PEEP in continuous variable. Figure 4 Nonlinear graphical depiction of the association between PEEP and AKI in patients surviving within 5 days after intubation.

Acknowledgements

The authors are particularly grateful to all caregivers, COVID-ICU investigators and patients who have been involved in the study.

COVID-ICU Group on behalf of the REVA Network and the COVID-ICU Investigators: Alain Mercat, Pierre Asfar, François Beloncle, Julien Demiselle, Tài Pham, Arthur Pavot, Xavier Monnet, Christian Richard, Alexandre Demoule, Martin Dres, Julien Mayaux, Alexandra Beurton, Cédric Daubin, Richard Descamps, Aurélie Joret, Damien Du Cheyron, Frédéric Pene, Jean-Daniel Chiche, Mathieu Jozwiak, Paul Jaubert, Guillaume Voiriot, Muriel Fartoukh, Marion Teulier, Clarisse Blayau, Erwen L’Her, Cécile Aubron, Laetitia Bodenes, Nicolas Ferriere, Johann Auchabie, Anthony Le Meur, Sylvain Pignal, Thierry Mazzoni, Jean-Pierre Quenot, Pascal Andreu, Jean-Baptiste Roudau, Marie Labruyère, Saad Nseir, Sébastien Preau, Julien Poissy, Daniel Mathieu, Sarah Benhamida, Rémi Paulet, Nicolas Roucaud, Martial Thyrault, Florence Daviet, Sami Hraiech, Gabriel Parzy, Aude Sylvestre, Sébastien Jochmans, Anne-Laure Bouilland, Mehran Monchi, MarcDanguy des Déserts, Quentin Mathais, Gwendoline Rager, Pierre Pasquier, Jean Reignier, Amélie Seguin, Charlotte Garret, Emmanuel Canet, Jean Dellamonica, Clément Saccheri, Romain Lombardi, Yanis Kouchit, Sophie Jacquier, Armelle Mathonnet, Mai-Ahn Nay, Isabelle Runge, Frédéric Martino, Laure Flurin, Amélie Rolle, Michel Carles, Rémi Coudroy, ArnaudW. Thille, Jean-Pierre Frat, Maeva Rodriguez, Pascal Beuret, Audrey Tientcheu, Arthur Vincent, Florian Michelin, Fabienne Tamion, Dorothée Carpentier, Déborah Boyer, Christophe Girault, Valérie Gissot, Stéphan Ehrmann, CharlotteSalmon Gandonniere, Djlali Elaroussi, Agathe Delbove, Yannick Fedun, Julien Huntzinger, Eddy Lebas, Grâce Kisoka, Céline Grégoire, Stella Marchetta, Bernard Lambermont, Laurent Argaud, Thomas Baudry, Pierre-Jean Bertrand, Auguste Dargent, Christophe Guitton, Nicolas Chudeau, Mickaël Landais, Cédric Darreau, Alexis Ferré, Antoine Gros, Guillaume Lacave, Fabrice Bruneel, Mathilde Neuville, Jérôme Devaquet, Guillaume Tachon, Richard Gallot, Riad Chelha, Arnaud Galbois, Anne Jallot, LudivineChalumeau Lemoine, Khaldoun Kuteifan, Valentin Pointurier, Louise-Marie Jandeaux, Joy Mootien, Charles Damoisel, Benjamin Sztrymf, Matthieu Schmidt, Alain Combes, Juliette Chommeloux, CharlesEdouard Luyt, Frédérique Schortgen, Leon Rusel, Camille Jung, Florent Gobert, Damien Vimpere, Lionel Lamhaut, Bertrand Sauneuf, Liliane Charrrier, Julien Calus, Isabelle Desmeules, Benoît Painvin, Jean-Marc Tadie, Vincent Castelain, Baptiste Michard, Jean-Etienne Herbrecht, Mathieu Baldacini, Nicolas Weiss, Sophie Demeret, Clémence Marois, Benjamin Rohaut, Pierre-Henri Moury, Anne-Charlotte Savida, Emmanuel Couadau, Mathieu Série, Nica Alexandru, Cédric Bruel, Candice Fontaine, Sonia Garrigou, JulietteCourtiade Mahler, Maxime Leclerc, Michel Ramakers, Pierre Garçon, Nicole Massou, Ly Van Vong, Juliane Sen, Nolwenn Lucas, Franck Chemouni, Annabelle Stoclin, Alexandre Avenel, Henri Faure, Angélie Gentilhomme, Sylvie Ricome, Paul Abraham, Céline Monard, Julien Textoris, Thomas Rimmele, Florent Montini, Gabriel Lejour, Thierry Lazard, Isabelle Etienney, Younes Kerroumi, Claire Dupuis, Marine Bereiziat, Elisabeth Coupez, François Thouy, Clément Hofmann, Nicolas Donat, Anne Chrisment, Rose-Marie Blot, Antoine Kimmoun, Audrey Jacquot, Matthieu Mattei, Bruno Levy, Ramin Ravan, Loïc Dopeux, Jean-Mathias Liteaudon, Delphine Roux, Brice Rey, Radu Anghel, Deborah Schenesse, Vincent Gevrey, Jermy Castanera, Philippe Petua, Benjamin Madeux, Otto Hartman, Michael Piagnerelli, Anne Joosten, Cinderella Noel, Patrick Biston, Thibaut Noel, Gurvan L E Bouar, Messabi Boukhanza, Elsa Demarest, Marie-France Bajolet, Nathanaël Charrier, Audrey Quenet, Cécile Zylberfajn, Nicolas Dufour, Bruno Mégarbane, Sébastian Voicu, Nicolas Deye, Isabelle Malissin, François Legay, Matthieu Debarre, Nicolas Barbarot, Pierre Fillatre, Bertrand Delord, Thomas Laterrade, Tahar Saghi, Wilfried Pujol, PierreJulien Cungi, Pierre Esnault, Mickael Cardinale, VivienHongTuan Ha, Grégory Fleury, Marie-Ange Brou, Daniel Zafmahazo, David Tran-Van, Patrick Avargues, Lisa Carenco, Nicolas Robin, Alexandre Ouali, Lucie Houdou, Christophe Le Terrier, Noémie Suh, Steve Primmaz, Jérome Pugin, Emmanuel Weiss, Tobias Gauss, Jean-Denis Moyer, CatherinePaugam Burtz, Béatrice La Combe, Rolland Smonig, Jade Violleau, Pauline Cailliez, Jonathan Chelly, Antoine Marchalot, Cécile Saladin, Christelle Bigot, Pierre-Marie Fayolle, Jules Fatséas, Amr Ibrahim, Dabor Resiere, Rabih Hage, Clémentine Cholet, Marie Cantier, Pierre Trouiler, Philippe Montravers, Brice Lortat-Jacob, Sebastien Tanaka, AlexyTran Dinh, Jacques Duranteau, Anatole Harrois, Guillaume Dubreuil, Marie Werner, Anne Godier, Sophie Hamada, Diane Zlotnik, Hélène Nougue, Armand Mekontso-Dessap, Guillaume Carteaux, Keyvan Razazi, Nicolas de Prost, Nicolas Mongardon, Nicolas Mongardon, Meriam Lamraoui, Claire Alessandri, Quentin de Roux, Charles de Roquetaillade, BenjaminG. Chousterman, Alexandre Mebazaa, Etienne Gayat, Marc Garnier, Emmanuel Pardo, Lea Satre-Buisson, Christophe Gutton, Elise Yvin, Clémence Marcault, Elie Azoulay, Michael Darmon, HafidAit Oufella, Geofroy Hariri, Tomas Urbina, Sandie Mazerand, Nicholas Heming, Francesca Santi, Pierre Moine, Djillali Annane, Adrien Bouglé, Edris Omar, Aymeric Lancelot, Emmanuelle Begot, Gaétan Plantefeve, Damien Contou, Hervé Mentec, Olivier Pajot, Stanislas Faguer, Olivier Cointault, Laurence Lavayssiere, Marie-Béatrice Nogier, Matthieu Jamme, Claire Pichereau, Jan Hayon, Hervé Outin, François Dépret, Maxime Coutrot, Maité Chaussard, Lucie Guillemet, Pierre Gofn, Romain Thouny, Julien Guntz, Laurent Jadot, Romain Persichini, Vanessa Jean-Michel, Hugues Georges, Thomas Caulier, Gaël Pradel, Marie-Hélène Hausermann, ThiMyHue Nguyen-Valat, Michel Boudinaud, Emmanuel Vivier, Sylvène Rosseli, Gaël Bourdin, Christian Pommier, Marc Vinclair, Simon Poignant, Sandrine Mons, Wulfran Bougouin, Franklin Bruna, Quentin Maestraggi, Christian Roth, Laurent Bitker, François Dhelft, Justine Bonnet-Chateau, Mathilde Filippelli, Tristan Morichau-Beauchant, Stéphane Thierry, Charlotte Le Roy, MélanieSaint Jouan, Bruno Goncalves, Aurélien Mazeraud, Matthieu Daniel, Tarek Sharshar, Cyril Cadoz, Rostane Gaci, Sébastien Gette, Guillaune Louis, Sophie-Caroline Sacleux, Marie-Amélie Ordan, Aurélie Cravoisy, Marie Conrad, Guilhem Courte, Sébastien Gibot, Younès Benzidi, Claudia Casella, Laurent Serpin, Jean-Lou Setti, Marie-Catherine Besse, Anna Bourreau, Jérôme Pillot, Caroline Rivera, Camille Vinclair, Marie-Aline Robaux, Chloé Achino, Marie-Charlotte Delignette, Tessa Mazard, Frédéric Aubrun, Bruno Bouchet, Aurélien Frérou, Laura Muller, Charlotte Quentin, Samuel Degoul, Xavier Stihle, Claude Sumian, Nicoletta Bergero, Bernard Lanaspre, Hervé Quintard, EveMarie Maiziere, Pierre-Yves Egreteau, Guillaume Leloup, Florin Berteau, Marjolaine Cottrel, Marie Bouteloup, Matthieu Jeannot, Quentin Blanc, Julien Saison, Isabelle Geneau, Romaric Grenot, Abdel Ouchike, Pascal Hazera, Anne-Lyse Masse, Suela Demiri, Corinne Vezinet, Elodie Baron, Deborah Benchetrit, Antoine Monsel, Grégoire Trebbia, Emmanuelle Schaack, Raphaël Lepecq, Mathieu Bobet, Christophe Vinsonneau, Thibault Dekeyser, Quentin Delforge, Imen Rahmani, Bérengère Vivet, Jonathan Paillot, Lucie Hierle, Claire Chaignat, Sarah Valette, Benoït Her, Jennifer Brunet, Mathieu Page, Fabienne Boiste, Anthony Collin, Florent Bavozet, Aude Garin, Mohamed Dlala, Kais Mhamdi, Bassem Beilouny, Alexandra Lavalard, Severine Perez, Benoit Veber, Pierre-Gildas Guitard, Philippe Gouin, Anna Lamacz, Fabienne Plouvier, Bertrand P Delaborde, Aïssa Kherchache, Amina Chaalal, Jean-Damien Ricard, Marc Amouretti, Santiago Freita-Ramos, Damien Roux, Jean-Michel Constantin, Mona Assef, Marine Lecore, Agathe Selves, Florian Prevost, Christian Lamer, Ruiying Shi, Lyes Knani, SébastienPili Floury, Lucie Vettoretti, Michael Levy, Lucile Marsac, Stéphane Dauger, Sophie Guilmin-Crépon, Hadrien Winiszewski, Gael Piton, Thibaud Soumagne, Gilles Capellier, Jean-Baptiste Putegnat, Frédérique Bayle, Maya Perrou, Ghyslaine Thao, Guillaume Géri, Cyril Charron, Xavier Repessé, Antoine Vieillard-Baron, Mathieu Guilbart, Pierre-Alexandre Roger, Sébastien Hinard, Pierre-Yves Macq, Kevin Chaulier, Sylvie Goutte, Patrick Chillet, Anaïs Pitta, Barbara Darjent, Amandine Bruneau, Sigismond Lasocki, Maxime Leger, Soizic Gergaud, Pierre Lemarie, Nicolas Terzi, Carole Schwebel, Anaïs Dartevel, Louis-Marie Galerneau, Jean-Luc Diehl, Caroline Hauw-Berlemont, Nicolas Péron, Emmanuel Guérot, AbolfazlMohebbi Amoli, Michel Benhamou, Jean-Pierre Deyme, Olivier Andremont, Diane Lena, Julien Cady, Arnaud Causeret, Arnaud De La Chapelle, Christophe Cracco, Stéphane Rouleau, David Schnell, Camille Foucault, Cécile Lory, Thibault Chapelle, Vincent Bruckert, Julie Garcia, Abdlazize Sahraoui, Nathalie Abbosh, Caroline Bornstain, Pierre Pernet, Florent Poirson, Ahmed Pasem, Philippe Karoubi, Virginie Poupinel, Caroline Gauthier, François Bouniol, Philippe Feuchere, Florent Bavozet, Anne Heron, Serge Carreira, Malo Emery, AnneSophie Le Floch, Luana Giovannangeli, Nicolas Herzog, Christophe Giacardi, Thibaut Baudic, Chloé Thill, Said Lebbah, Jessica Palmyre, Florence Tubach, David Hajage, Nicolas Bonnet, Nathan Ebstein, Stéphane Gaudry, Yves Cohen, Julie Noublanche, Olivier Lesieur, Arnaud Sément, Isabel Roca-Cerezo, Michel Pascal, Nesrine Sma, Gwenhaël Colin, Jean-Claude Lacherade, Gauthier Bionz, Natacha Maquigneau, Pierre Bouzat, Michel Durand, Marie-Christine Hérault, Jean-Francois Payen

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% Confidence interval

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- ARDS

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- BMI

Body mass index

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ΔP

Driving pressure

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- KDIGO

Kidney disease improval global outcomes

- MDRD

Modification of diet in renal disease

- MV

Mechanical ventilation

- NO

Nitric oxide

- OR

Odds ratio

- PaCO2

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PaO2/FiO2

Ratio between arterial oxygen pressure to the fraction of inspired oxygen

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- PP

Prone position

- Pplat

Plateau pressure

- RBF

Renal blood flow

- RRT

Renal replacement therapy

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score

- SAPS II

Simplified acute physiology score II

- IBW

Ideal body weight

- RV

Right ventricle

- Vt

Tidal volume

Author contributions

Florent Bavozet (FB), Lionel Tchatat-Wangueu (LTW), and Léo Poirot (LP) conceived and designed the study and were involved in drafting the manuscript. FB performed the data retrieval. LTW, Isaure Breteau (IB) performed the statistical analysis. All the authors were involved in the interpretation of the data, in drafting the manuscript, and made critical revisions to the discussion section. All authors read and approved the final version to be published.

Funding

This study was funded by the Foundation AP-HP and the Direction de la Recherche Clinique et du Development and the French Ministry of Health. The REVA network received a 75 000 € research grant form Air Liquide Healthcare. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the institution.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committees of Switzerland (BASEC #: 2020-00704), the French Intensive Care Society (CE-SRLF 20-23) and Belgium (2020-294) approved the data collection protocol.

Consent for publication

All patients or close relatives were informed that their data were included in the COVID-ICU cohort.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Florent Bavozet, Email: fbavozet@ch-dreux.fr.

COVID ICU Group on behalf of the REVA Network and the COVID-ICU Investigators:

Alain Mercat, Pierre Asfar, François Beloncle, Julien Demiselle, Tài Pham, Arthur Pavot, Xavier Monnet, Christian Richard, Alexandre Demoule, Martin Dres, Julien Mayaux, Alexandra Beurton, Cédric Daubin, Richard Descamps, Aurélie Joret, Damien Du Cheyron, Frédéric Pene, Jean-Daniel Chiche, Mathieu Jozwiak, Paul Jaubert, Guillaume Voiriot, Muriel Fartoukh, Marion Teulier, Clarisse Blayau, Erwen L’Her, Cécile Aubron, Laetitia Bodenes, Nicolas Ferriere, Johann Auchabie, Anthony Le Meur, Sylvain Pignal, Thierry Mazzoni, Jean-Pierre Quenot, Pascal Andreu, Jean-Baptiste Roudau, Marie Labruyère, Saad Nseir, Sébastien Preau, Julien Poissy, Daniel Mathieu, Sarah Benhamida, Rémi Paulet, Nicolas Roucaud, Martial Thyrault, Florence Daviet, Sami Hraiech, Gabriel Parzy, Aude Sylvestre, Sébastien Jochmans, Anne-Laure Bouilland, Mehran Monchi, Marc Danguy des Déserts, Quentin Mathais, Gwendoline Rager, Pierre Pasquier, Jean Reignier, Amélie Seguin, Charlotte Garret, Emmanuel Canet, Jean Dellamonica, Clément Saccheri, Romain Lombardi, Yanis Kouchit, Sophie Jacquier, Armelle Mathonnet, Mai-Ahn Nay, Isabelle Runge, Frédéric Martino, Laure Flurin, Amélie Rolle, Michel Carles, Rémi Coudroy, Arnaud W. Thille, Jean-Pierre Frat, Maeva Rodriguez, Pascal Beuret, Audrey Tientcheu, Arthur Vincent, Florian Michelin, Fabienne Tamion, Dorothée Carpentier, Déborah Boyer, Christophe Girault, Valérie Gissot, Stéphan Ehrmann, Charlotte Salmon Gandonniere, Djlali Elaroussi, Agathe Delbove, Yannick Fedun, Julien Huntzinger, Eddy Lebas, Grâce Kisoka, Céline Grégoire, Stella Marchetta, Bernard Lambermont, Laurent Argaud, Thomas Baudry, Pierre-Jean Bertrand, Auguste Dargent, Christophe Guitton, Nicolas Chudeau, Mickaël Landais, Cédric Darreau, Alexis Ferré, Antoine Gros, Guillaume Lacave, Fabrice Bruneel, Mathilde Neuville, Jérôme Devaquet, Guillaume Tachon, Richard Gallot, Riad Chelha, Arnaud Galbois, Anne Jallot, Ludivine Chalumeau Lemoine, Khaldoun Kuteifan, Valentin Pointurier, Louise-Marie Jandeaux, Joy Mootien, Charles Damoisel, Benjamin Sztrymf, Alain Combes, Juliette Chommeloux, Charles Edouard Luyt, Frédérique Schortgen, Leon Rusel, Camille Jung, Florent Gobert, Damien Vimpere, Lionel Lamhaut, Bertrand Sauneuf, Liliane Charrrier, Julien Calus, Isabelle Desmeules, Benoît Painvin, Jean-Marc Tadie, Vincent Castelain, Baptiste Michard, Jean-Etienne Herbrecht, Mathieu Baldacini, Nicolas Weiss, Sophie Demeret, Clémence Marois, Benjamin Rohaut, Pierre-Henri Moury, Anne-Charlotte Savida, Emmanuel Couadau, Mathieu Série, Nica Alexandru, Cédric Bruel, Candice Fontaine, Sonia Garrigou, Juliette Courtiade Mahler, Maxime Leclerc, Michel Ramakers, Pierre Garçon, Nicole Massou, Ly Van Vong, Juliane Sen, Nolwenn Lucas, Franck Chemouni, Annabelle Stoclin, Alexandre Avenel, Henri Faure, Angélie Gentilhomme, Sylvie Ricome, Paul Abraham, Céline Monard, Julien Textoris, Thomas Rimmele, Florent Montini, Gabriel Lejour, Thierry Lazard, Isabelle Etienney, Younes Kerroumi, Claire Dupuis, Marine Bereiziat, Elisabeth Coupez, François Thouy, Clément Hofmann, Nicolas Donat, Anne Chrisment, Rose-Marie Blot, Antoine Kimmoun, Audrey Jacquot, Matthieu Mattei, Bruno Levy, Ramin Ravan, Loïc Dopeux, Jean-Mathias Liteaudon, Delphine Roux, Brice Rey, Radu Anghel, Deborah Schenesse, Vincent Gevrey, Jermy Castanera, Philippe Petua, Benjamin Madeux, Otto Hartman, Michael Piagnerelli, Anne Joosten, Cinderella Noel, Patrick Biston, Thibaut Noel, Gurvan L E Bouar, Messabi Boukhanza, Elsa Demarest, Marie-France Bajolet, Nathanaël Charrier, Audrey Quenet, Cécile Zylberfajn, Nicolas Dufour, Bruno Mégarbane, Sébastian Voicu, Nicolas Deye, Isabelle Malissin, François Legay, Matthieu Debarre, Nicolas Barbarot, Pierre Fillatre, Bertrand Delord, Thomas Laterrade, Tahar Saghi, Wilfried Pujol, Pierre Julien Cungi, Pierre Esnault, Mickael Cardinale, Vivien Hong Tuan Ha, Grégory Fleury, Marie-Ange Brou, Daniel Zafmahazo, David Tran-Van, Patrick Avargues, Lisa Carenco, Nicolas Robin, Alexandre Ouali, Lucie Houdou, Christophe Le Terrier, Noémie Suh, Steve Primmaz, Jérome Pugin, Emmanuel Weiss, Tobias Gauss, Jean-Denis Moyer, Catherine Paugam Burtz, Béatrice La Combe, Rolland Smonig, Jade Violleau, Pauline Cailliez, Jonathan Chelly, Antoine Marchalot, Cécile Saladin, Christelle Bigot, Pierre-Marie Fayolle, Jules Fatséas, Amr Ibrahim, Dabor Resiere, Rabih Hage, Clémentine Cholet, Marie Cantier, Pierre Trouiler, Philippe Montravers, Brice Lortat-Jacob, Sebastien Tanaka, Alexy Tran Dinh, Jacques Duranteau, Anatole Harrois, Guillaume Dubreuil, Marie Werner, Anne Godier, Sophie Hamada, Diane Zlotnik, Hélène Nougue, Armand Mekontso-Dessap, Guillaume Carteaux, Keyvan Razazi, Nicolas de Prost, Nicolas Mongardon, Nicolas Mongardon, Meriam Lamraoui, Claire Alessandri, Quentin de Roux, Charles de Roquetaillade, Benjamin G. Chousterman, Alexandre Mebazaa, Etienne Gayat, Marc Garnier, Emmanuel Pardo, Lea Satre-Buisson, Christophe Gutton, Elise Yvin, Clémence Marcault, Elie Azoulay, Michael Darmon, Hafid Ait Oufella, Geofroy Hariri, Tomas Urbina, Sandie Mazerand, Nicholas Heming, Francesca Santi, Pierre Moine, Djillali Annane, Adrien Bouglé, Edris Omar, Aymeric Lancelot, Emmanuelle Begot, Gaétan Plantefeve, Damien Contou, Hervé Mentec, Olivier Pajot, Stanislas Faguer, Olivier Cointault, Laurence Lavayssiere, Marie-Béatrice Nogier, Matthieu Jamme, Claire Pichereau, Jan Hayon, Hervé Outin, François Dépret, Maxime Coutrot, Maité Chaussard, Lucie Guillemet, Pierre Gofn, Romain Thouny, Julien Guntz, Laurent Jadot, Romain Persichini, Vanessa Jean-Michel, Hugues Georges, Thomas Caulier, Gaël Pradel, Marie-Hélène Hausermann, Thi My Hue Nguyen-Valat, Michel Boudinaud, Emmanuel Vivier, Sylvène Rosseli, Gaël Bourdin, Christian Pommier, Marc Vinclair, Simon Poignant, Sandrine Mons, Wulfran Bougouin, Franklin Bruna, Quentin Maestraggi, Christian Roth, Laurent Bitker, François Dhelft, Justine Bonnet-Chateau, Mathilde Filippelli, Tristan Morichau-Beauchant, Stéphane Thierry, Charlotte Le Roy, Mélanie Saint Jouan, Bruno Goncalves, Aurélien Mazeraud, Matthieu Daniel, Tarek Sharshar, Cyril Cadoz, Rostane Gaci, Sébastien Gette, Guillaune Louis, Sophie-Caroline Sacleux, Marie-Amélie Ordan, Aurélie Cravoisy, Marie Conrad, Guilhem Courte, Sébastien Gibot, Younès Benzidi, Claudia Casella, Laurent Serpin, Jean-Lou Setti, Marie-Catherine Besse, Anna Bourreau, Jérôme Pillot, Caroline Rivera, Camille Vinclair, Marie-Aline Robaux, Chloé Achino, Marie-Charlotte Delignette, Tessa Mazard, Frédéric Aubrun, Bruno Bouchet, Aurélien Frérou, Laura Muller, Charlotte Quentin, Samuel Degoul, Xavier Stihle, Claude Sumian, Nicoletta Bergero, Bernard Lanaspre, Hervé Quintard, Eve Marie Maiziere, Pierre-Yves Egreteau, Guillaume Leloup, Florin Berteau, Marjolaine Cottrel, Marie Bouteloup, Matthieu Jeannot, Quentin Blanc, Julien Saison, Isabelle Geneau, Romaric Grenot, Abdel Ouchike, Pascal Hazera, Anne-Lyse Masse, Suela Demiri, Corinne Vezinet, Elodie Baron, Deborah Benchetrit, Antoine Monsel, Grégoire Trebbia, Emmanuelle Schaack, Raphaël Lepecq, Mathieu Bobet, Christophe Vinsonneau, Thibault Dekeyser, Quentin Delforge, Imen Rahmani, Bérengère Vivet, Jonathan Paillot, Lucie Hierle, Claire Chaignat, Sarah Valette, Benoït Her, Jennifer Brunet, Mathieu Page, Fabienne Boiste, Anthony Collin, Aude Garin, Mohamed Dlala, Kais Mhamdi, Bassem Beilouny, Alexandra Lavalard, Severine Perez, Benoit Veber, Pierre-Gildas Guitard, Philippe Gouin, Anna Lamacz, Fabienne Plouvier, Bertrand P Delaborde, Aïssa Kherchache, Amina Chaalal, Jean-Damien Ricard, Marc Amouretti, Santiago Freita-Ramos, Damien Roux, Jean-Michel Constantin, Mona Assef, Marine Lecore, Agathe Selves, Florian Prevost, Christian Lamer, Ruiying Shi, Lyes Knani, Sébastien Pili Floury, Lucie Vettoretti, Michael Levy, Lucile Marsac, Stéphane Dauger, Sophie Guilmin-Crépon, Hadrien Winiszewski, Gael Piton, Thibaud Soumagne, Gilles Capellier, Jean-Baptiste Putegnat, Frédérique Bayle, Maya Perrou, Ghyslaine Thao, Guillaume Géri, Cyril Charron, Xavier Repessé, Antoine Vieillard-Baron, Mathieu Guilbart, Pierre-Alexandre Roger, Sébastien Hinard, Pierre-Yves Macq, Kevin Chaulier, Sylvie Goutte, Patrick Chillet, Anaïs Pitta, Barbara Darjent, Amandine Bruneau, Sigismond Lasocki, Maxime Leger, Soizic Gergaud, Pierre Lemarie, Nicolas Terzi, Carole Schwebel, Anaïs Dartevel, Louis-Marie Galerneau, Jean-Luc Diehl, Caroline Hauw-Berlemont, Nicolas Péron, Emmanuel Guérot, Abolfazl Mohebbi Amoli, Michel Benhamou, Jean-Pierre Deyme, Olivier Andremont, Diane Lena, Julien Cady, Arnaud Causeret, Arnaud De La Chapelle, Christophe Cracco, Stéphane Rouleau, David Schnell, Camille Foucault, Cécile Lory, Thibault Chapelle, Vincent Bruckert, Julie Garcia, Abdlazize Sahraoui, Nathalie Abbosh, Caroline Bornstain, Pierre Pernet, Florent Poirson, Ahmed Pasem, Philippe Karoubi, Virginie Poupinel, Caroline Gauthier, François Bouniol, Philippe Feuchere, Anne Heron, Serge Carreira, Malo Emery, Anne Sophie Le Floch, Luana Giovannangeli, Nicolas Herzog, Christophe Giacardi, Thibaut Baudic, Chloé Thill, Said Lebbah, Jessica Palmyre, Florence Tubach, David Hajage, Nicolas Bonnet, Nathan Ebstein, Stéphane Gaudry, Yves Cohen, Julie Noublanche, Olivier Lesieur, Arnaud Sément, Isabel Roca-Cerezo, Michel Pascal, Nesrine Sma, Gwenhaël Colin, Jean-Claude Lacherade, Gauthier Bionz, Natacha Maquigneau, Pierre Bouzat, Michel Durand, Marie-Christine Hérault, and Jean-Francois Payen

References

- 1.The ARDS Definition Task Force*. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–33. 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNicholas BA, Rezoagli E, Pham T, et al. Impact of early acute kidney injury on management and outcome in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a secondary analysis of a multicenter observational study*. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(9):1216–25. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabarre P, Dumas G, Zafrani L. Insuffisance rénale aiguë chez les patients COVID-19 en soins intensifs. Med Intensiv Reanim. 2021;30:43–52. 10.37051/mir-00069. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alenezi FK, Almeshari MA, Mahida R, Bangash MN, Thickett DR, Patel JM. Incidence and risk factors of acute kidney injury in COVID-19 patients with and without acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) during the first wave of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2021;43(1):1621–33. 10.1080/0886022X.2021.2011747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012;81(5):442–8. 10.1038/ki.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darmon M, Clec’h C, Adrie C, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and risk of AKI among critically ill patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(8):1347–53. 10.2215/CJN.08300813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geri G, Darmon M, Zafrani L, et al. Acute kidney injury in SARS-CoV2-related pneumonia ICU patients: a retrospective multicenter study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):86. 10.1186/s13613-021-00875-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fougères E, Teboul JL, Richard C, Osman D, Chemla D, Monnet X. Hemodynamic impact of a positive end-expiratory pressure setting in acute respiratory distress syndrome: importance of the volume status. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):802–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c587fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husain-Syed F, Slutsky AS, Ronco C. Lung-kidney cross-talk in the critically ill patient. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(4):402–14. 10.1164/rccm.201602-0420CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vieillard-Baron A, Matthay M, Teboul JL, et al. Experts’ opinion on management of hemodynamics in ARDS patients: focus on the effects of mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):739–49. 10.1007/s00134-016-4326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostermann M, Hall A, Crichton S. Low mean perfusion pressure is a risk factor for progression of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients—a retrospective analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:151. 10.1186/s12882-017-0568-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annat G, Viale JP, Xuan BB, et al. Effect of PEEP ventilation on renal function, plasma renin, aldosterone, neurophysins and urinary ADH, and prostaglandins. Anesthesiology. 1983;58(2):136–41. 10.1097/00000542-198302000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranieri VM, Giunta F, Suter PM, Slutsky AS. Mechanical ventilation as a mediator of multisystem organ failure in acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2000;284(1):43–4. 10.1001/jama.284.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meade MO, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, et al. Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(6):637–45. 10.1001/jama.299.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2126–36. 10.1056/NEJMra1208707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Rossi S, Chiumello D. COVID-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1299–300. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–81. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grasso S, Mirabella L, Murgolo F, et al. Effects of positive end-expiratory pressure in “high compliance” severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):e1332–6. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ottolina D, Zazzeron L, Trevisi L, et al. Acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients with Covid-19 infection is associated with ventilatory management with elevated positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). J Nephrol. 2022;35(1):99–111. 10.1007/s40620-021-01100-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basse P, Morisson L, Barthélémy R, et al. Relationship between positive end-expiratory pressure levels, central venous pressure, systemic inflammation and acute renal failure in critically ill ventilated COVID-19 patients: a monocenter retrospective study in France. Acute Crit Care. 2023;38(2):172–81. 10.4266/acc.2022.01494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beurton A, Haudebourg L, Simon-Tillaux N, Demoule A, Dres M. Limiting positive end-expiratory pressure to protect renal function in SARS-CoV-2 critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2020;59:191–3. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valk CMA, Tsonas AM, Botta M, et al. Association of early positive end-expiratory pressure settings with ventilator-free days in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 acute respiratory distress syndrome: a secondary analysis of the practice of VENTilation in COVID-19 study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38(12):1274–83. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.COVID-ICU Group on behalf of the REVA Network and the COVID-ICU Investigators. Clinical characteristics and day-90 outcomes of 4244 critically ill adults with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(1):60–73. 10.1007/s00134-020-06294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–84. 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Závada J, Hoste E, Cartin-Ceba R, et al. A comparison of three methods to estimate baseline creatinine for RIFLE classification. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(12):3911–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfp766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch JS, Ng JH, Ross DW, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):209–18. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panitchote A, Mehkri O, Hastings A, et al. Factors associated with acute kidney injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):74. 10.1186/s13613-019-0552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta S, Coca SG, Chan L, et al. AKI treated with renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19. JASN. 2021;32(1):161–76. 10.1681/ASN.2020060897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, et al. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):327–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa032193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercat A, Richard JCM, Vielle B, et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure setting in adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(6):646–55. 10.1001/jama.299.6.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lumlertgul N, Baker E, Pearson E, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):118. 10.1186/s13613-022-01094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leite TT, Gomes CAM, Valdivia JMC, Libório AB. Respiratory parameters and acute kidney injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a causal inference study. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(23):742. 10.21037/atm.2019.11.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lombardi R, Nin N, Peñuelas O, et al. Acute kidney injury in mechanically ventilated patients: the risk factor profile depends on the timing of Aki onset. Shock. 2017;48(4):411–7. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puybasset L, Cluzel P, Gusman P, Grenier P, Preteux F, Rouby JJ. Regional distribution of gas and tissue in acute respiratory distress syndrome. I. Consequences for lung morphology. CT Scan ARDS Study Group. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(7):857–69. 10.1007/s001340051274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1775–86. 10.1056/NEJMoa052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calfee CS, Delucchi K, Parsons PE, et al. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(8):611–20. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mekontso Dessap A, Charron C, Devaquet J, et al. Impact of acute hypercapnia and augmented positive end-expiratory pressure on right ventricle function in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(11):1850–8. 10.1007/s00134-009-1569-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1099–102. 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fogagnolo A, Grasso S, Dres M, et al. Focus on renal blood flow in mechanically ventilated patients with SARS-CoV-2: a prospective pilot study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36(1):161–7. 10.1007/s10877-020-00633-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barthélémy R, Beaucoté V, Bordier R, et al. Haemodynamic impact of positive end-expiratory pressure in SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory distress syndrome: oxygenation versus oxygen delivery. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126(2):e70–2. 10.1016/j.bja.2020.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Botta M, Tsonas AM, Pillay J, et al. Ventilation management and clinical outcomes in invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 (PRoVENT-COVID): a national, multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(2):139–48. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haudebourg AF, Perier F, Tuffet S, et al. Respiratory mechanics of COVID-19- versus non-COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):287–90. 10.1164/rccm.202004-1226LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mekontso Dessap A, Boissier F, Charron C, et al. Acute cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: prevalence, predictors, and clinical impact. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):862–70. 10.1007/s00134-015-4141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salahuddin N, Sammani M, Hamdan A, et al. Fluid overload is an independent risk factor for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: results of a cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):45. 10.1186/s12882-017-0460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1436–47. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rezoagli E, McNicholas B, Pham T, Bellani G, Laffey JG. Lung-kidney cross-talk in the critically ill: insights from the Lung Safe study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):1072–3. 10.1007/s00134-020-05962-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doig GS, McIlroy DR. Acute kidney injury in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: the chicken or the egg? Crit Care Med. 2019;47(9):1273–4. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benites MH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Kattan E, Cruces P, Retamal J. Ventilation-induced acute kidney injury in acute respiratory failure: do PEEP levels matter? Crit Care. 2025;29(1):130. 10.1186/s13054-025-05343-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoste EAJ, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(8):1411–23. 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duggan M, McCaul CL, McNamara PJ, Engelberts D, Ackerley C, Kavanagh BP. Atelectasis causes vascular leak and lethal right ventricular failure in uninjured rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(12):1633–40. 10.1164/rccm.200210-1215OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amato MBP, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):747–55. 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiumello D, Carlesso E, Brioni M, Cressoni M. Airway driving pressure and lung stress in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:276. 10.1186/s13054-016-1446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gattinoni L, Marini JJ, Collino F, et al. The future of mechanical ventilation: lessons from the present and the past. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):183. 10.1186/s13054-017-1750-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788. 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pickering JW, Endre ZH. Back-calculating baseline creatinine with MDRD misclassifies acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(7):1165–73. 10.2215/CJN.08531109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lombardi R, Nin N, Lorente JA, et al. An assessment of the acute kidney injury network creatinine-based criteria in patients submitted to mechanical ventilation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1547–55. 10.2215/CJN.09531010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orieux A, Boyer A, Dewitte A, Combe C, Rubin S. Insuffisance rénale aiguë en soins intensifs-réanimation et ses conséquences: mise au point. Nephrol Ther. 2022;18(1):7–20. 10.1016/j.nephro.2021.07.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1. Figure 1 Multivariable analyse of factors associated with AKI (KDIGO stages 2–3) assessed within the first five days following intubation– PEEP in continuous variable. Figure 2 Nonlinear graphical depiction of the association between PEEP and AKI (KDIGO stages 2–3). Figure 3 Multivariable analysis of factors associated with AKI within the first five days following intubation in patients surviving at least 5 days post intubation– PEEP in continuous variable. Figure 4 Nonlinear graphical depiction of the association between PEEP and AKI in patients surviving within 5 days after intubation.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the institution.