Abstract

We have shown previously that cardiac G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels are inhibited by Gq protein-coupled receptors (GqPCRs) via phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) depletion in a receptor-specific manner. To investigate the mechanism of receptor specificity, we examined whether the activation of GqPCRs induces localized PIP2 depletion. When we applied endothelin-1 to the bath, GIRK channel activities recorded in cell-attached patches were not changed, implying that PIP2 signal is not diffusible but is a localized signal. To test this possibility, we directly measured lateral diffusion by introducing fluorescence-labeled phosphoinositides to a small area of the membrane with patch pipettes. After pipettes were attached, phosphatidylinositol 4-monophosphate or phosphatidylinositol diffused rapidly to the entire membrane, whereas PIP2 was confined to the membrane patch inside the pipette. The confinement of PIP2 was disrupted after cytochalasin D treatment, suggesting that the cytoskeleton is responsible for the low mobility of PIP2. The diffusion coefficient (D) of PIP2 in the plasma membrane measured with the fluorescence recovery after photobleaching technique was 0.00039 μm2/s(n = 6), which is markedly lower than D of phosphatidylinositol (5.8 μm2/s, n = 5). Simulation of PIP2 concentration profiles by the diffusion model confirms that when D is small, the kinetics of PIP2 depletion at different distances from phospholipase C becomes similar to the characteristic kinetics of GIRK inhibition by different agonists. These results imply that PIP2 depletion is localized adjacent to GqPCRs because of its low mobility, and that spatial proximity of GqPCR and the target protein underlies the receptor specificity of PIP2-mediated signaling.

Protein–lipid interactions have been increasingly appreciated in recent years. In particular, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) binds a wide variety of cellular proteins, including cytoskeletal proteins and ion channels, and evidence that the binding is essential for their functions is accumulating (1, 2). Because many proteins are known to be regulated by PIP2, the question arises as to how a particular protein, among many others, is selectively regulated by PIP2 changes generated by specific signals. In fact, the same question has been asked for many years in the context of the signaling role of Ca2+, i.e., “how are so many different Ca2+-dependent reactions selectively choreographed within a cell?” The results of numerous studies undertaken to answer this question have led to the idea that the secret lies in localization, i.e., cells have many means of generating intracellular Ca2+ signals, and the spatial proximities of these signals to the molecular targets of Ca2+ determine the specificity of Ca2+ action (3). However, it is not known whether this idea can be applied to PIP2-dependent signaling.

Because experimental methods of measuring or visualizing changes in PIP2 during signaling pathway stimulation remain problematic (4, 5), monitoring changes in the activities of PIP2-dependent target proteins serves as a useful means of investigating the nature of PIP2 signaling. We previously studied the kinetics of PIP2-mediated signaling in response to the activation of Gq protein-coupled receptors (GqPCRs) by monitoring the activities of PIP2-interacting ion channels, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels, and inwardly rectifying background K+ channels (6). We demonstrated that the PIP2 depletion profile reflected by GIRK channel inhibition is not consistent with the PIP2 depletion profile reflected by inwardly rectifying background K+ channel inhibition. These results can be explained if the activation of GqPCRs causes PIP2 depletion not uniformly but locally and if the activity of each channel reflects the local PIP2 level. In the present study, we examined changes in GIRK channel activity in a small patch of the membrane, while GqPCRs were activated in the rest of the membrane. The results obtained provide direct evidence of the localized nature of PIP2 signaling.

The mobility of a signal molecule is an important determinant of its temporal and spatial profile. The results of our previous study (6) imply that PIP2 depletion develops with a slow time course (with t1/2 values of the order of several tens of seconds). If such slow changes occur in a localized fashion, the mobility of PIP2 should be low. However, previous studies that have estimated the diffusion coefficient (D) of PIP2 or phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in cultured neuroblastoma or fibroblast cells with fluorescent labels suggest that their Ds are not low (≈0.5–2 μm2/s) (7, 8), and, thus, these species are as fast as freely diffusible membrane lipids. In the present study, we developed methods to measure the lateral mobility of PIP2 along the plasma membrane and found that, in fact, it is very low in mouse atrial myocytes. Using a diffusion model to simulate the temporal and spatial profiles of PIP2, we found that PIP2 diffusion profiles depend strongly on the distance from phospholipase C (PLC) when PIP2 mobility is low, and that the receptor specificity of PIP2-mediated signaling presented in our earlier work can be explained by differences in spatial proximities of GqPCRs and GIRK channel protein. These results suggest that the low mobility of PIP2 and the spatial proximity between the receptor and the PIP2-interacting molecular target determine the receptor-specific nature of PIP2-mediated signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cells. Mouse atrial myocytes were isolated by perfusing Ca2+-free normal Tyrode solution containing collagenase (0.14 mg/ml, Yakult Pharmaceutical, Tokyo) on a Langendorff column at 37°C as described (9). Isolated atrial myocytes were kept in high-K+, low-Cl- solution at 4°C until required for electrophysiological study or fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments.

Solutions and Chemicals. Normal Tyrode solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 5 mM Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Ca2+-free solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 5 mM Hepes, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The high-K+, low-Cl- solution contained 70 mM KOH, 40 mM KCl, 50 mM l-glutamic acid, 20 mM taurine, 20 mM KH2PO4, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, and 0.5 mM EGTA. The pipette solution for ruptured whole-cell patches contained 20 mM KCl, 110 mM potassium aspartate, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MgATP, 5 mM EGTA, and 0.01 mM GTP, titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH. For single-channel experiments, the bath solution contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Hepes, and 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4 (with KOH). And, the pipettes solution contained 140 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 (with KOH).

Acetylcholine (ACh) and endothelin 1 (ET-1) (both from Sigma) were dissolved in deionized water to produce a stock solution and stored at -20°C. On the day of the experiment one aliquot was thawed and used. When required, 10 μM glibenclamide was applied in the presence of ACh to inhibit the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. To ensure a rapid solution turnover, the rate of superfusion was kept >5 ml/min, which corresponded to 50 bath volumes (100 μl)/min. Fluorescent 4,4-dif luoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-propionic acid (BODIPY)-conjugated phosphatidylinositol (PI) phosphate derivatives [BODIPY FL C5,C6-PI, BODIPY FL C5,C6-PI(4)P, and BODIPY FL C5,C6-PI(4,5)P2], and histone polyamine carrier were purchased from Molecular Probes. Fluorescent 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD)-conjugated phosphatidylinositol phosphate derivatives [NBD-diC16-PI, NBD-diC16-PI(4)P, and NBD-diC16-PI(4,5)P2] were purchased from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City).

Voltage-Clamp Recording and Analysis. Single-channel activity was recorded in the cell-attached patch configuration with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Fire-polished pipettes (5–6 MΩ) were used. Channel activity was monitored at -80 mV at a sampling rate of 5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz. Single-channel records were analyzed with pclamp software. Parameters used for single-channel analysis included total open probability (NPo) and mean open time. Results are displayed as averages over 5-s bins.

Delivery of Fluorescent Phospholipids to Cells. Fluorescent phospholipids were dissolved in deionized water or DMSO to produce a stock solution (1 μg/μl) and stored at -20°C. On the day of the experiments one aliquot was thawed and used. Phosphoinositide–Shuttle phosphatidylinositol 4-monophosphate (PIP) complex was prepared by mixing 2 μl of 1 μg/μl phosphoinositide stock solution with 2 μl of 0.5 mM Shuttle PIP stock solution. Cells were incubated with complex solution for 30–45 min and then superfused with a standard bath solution. To determine the extent to which loaded fluorescent labels were metabolized within myocytes, we extracted membrane lipids from cells loaded with BODIPY-PIP2 and analyzed them by TLC. The results obtained shows that BODIPY-PIP2 is metabolized to some extent in myocytes to BODIPY-PIP and BODIPY-PI (PIP2/PIP/PI, 63:13:24% after 1 h, n = 3; Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

The localized delivery of fluorescent phospholipids to atrial myocytes was achieved by attaching a micropipette (tip resistance ≈3–4 MΩ) containing a NBD–labeled phospholipid-carrier complex to myocytes. Electrode attachment was confirmed by a fluorescent meniscus, which was a “stained” patch membrane touching NBD-labeled phospholipids directly.

TLC. TLC of extracted lipids was performed by using oxalateimpregnated silica gel as described (10), except that precautions were taken to minimize fluorescence bleaching during extraction and separation (by omitting strong acids and working under subdued lighting), so that fluorescent signals could be detected and quantified on TLC plates.

FRAP Measurement. FRAP was performed by using a Leica TCS-SP2 confocal microscope and the 488-nm line (BODIPY-PIP2) of aKr/Ar laser in conjunction with a ×63 water immersion objective. Spots were photobleached at full laser power (100% power, 100% transmission), and fluorescence recovery was monitored by scanning whole cells at low laser power (100% power, 0.6% transmission) at the indicated intervals until the intensity reached a steady plateau. Negligible bleaching occurred while imaging the recovery process at low laser power.

Statistics and Presentation of Data. Results are presented as means ± SE (n = number of cells tested). Statistical analyses were performed by using the Student t test, and differences between two groups were considered significant for P < 0.01.

Supporting Information. The equation used for FRAP analysis and the model equation used to simulate PIP2 depletion profiles (see Figs. 5 and 6) are published as Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. TLC analysis of extracted fluorescent lipids, the effect of cytochalasin D on the time courses of NBD-labeled PIP2 loading, and the spatial profiles of PIP2 concentrations are shown in Figs. 7–9, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

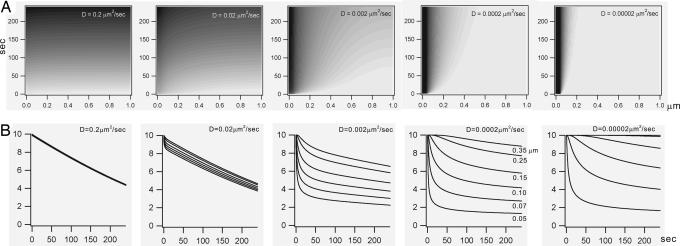

Fig. 5.

Effect of distance from the PLC domain on PIP2 depletion profiles. (A) Simulation results for temporal and spatial changes in [PIP2] during PLC activation (abscissa: distance from PLC in μm; ordinate: time in s). Concentration of PIP2 is represented by a gray scale. Parameters for numerical integration: Vmax of PLC = 20 μM/s; Km of PLC = 50% of initial [PIP2]; rmax = 1 μm; Δr = 10 nm; Δt = 0.2 ms; DPIP2 = ≈0.2–0.00002 μm2/s, as indicated. (B) Changes in PIP2 concentrations over time were calculated at 0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.15, 0.25, and 0.35 μm from the center of the PLC domain when the D value was given ≈0.2–0.00002 μm2/s, as indicated. Note that spatial differences in depletion kinetics increased as D decreased.

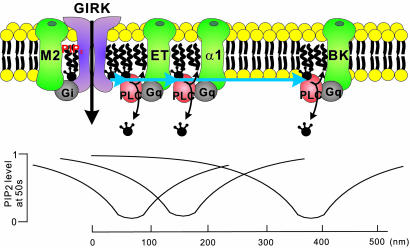

Fig. 6.

Model for the spatio-temporal coding of PIP2 signaling in cardiac myocytes. Activation of ET, α1 adrenergic, or BK receptors stimulated PLCβ, which caused PIP2 depletion. Complexes of ET receptors with GIRKs create high local change in [PIP2] in close proximity to GIRKs. Although BK receptors activate PLCβ and consequently deplete PIP2, they fail to inhibit GIRKs because they are physically excluded and remote from GIRK domains. Inhibition of GIRKs by remote GqPCRs is prevented by the low mobility of PIP2. Local changes in [PIP2] caused by the stimulation of ET, α1 adrenergic, or BK receptors were simulated by using the method described in Fig. 5 and [PIP2]at 50 s were plotted. The zero point on the abscissa represents the GIRK channel.

Results and Discussion

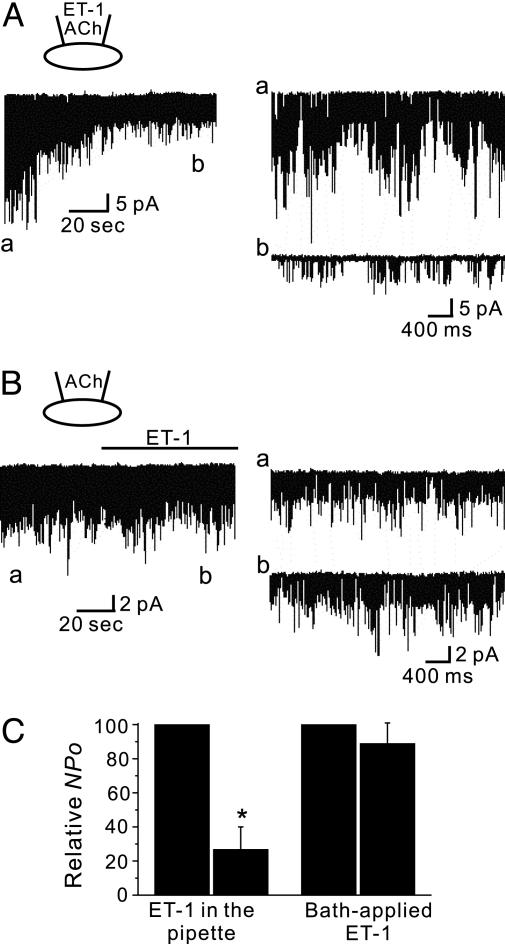

PIP2 Acts as a Localized Signal. To determine whether PIP2 depletion is localized to microdomains or whether PIP2 diffuses freely to produce a global signal, we used the experimental protocol first developed by Soejima and Noma (11) to confirm that Gβγ is a membrane-delimited and localized signal. We examined whether bath applications of ET-1 inhibited GIRK channel activity in cell-attached patches. Fig. 1A shows a representative single-channel recording of GIRK channels from a cell-attached patch of atrial membrane held at -80 mV when channels were activated by pipette applications of ACh. We first confirmed that the single-channel properties observed were compatible with the known features of heart cell GIRK channels (11–14). Mean slope conductance and mean open time were 42.4 ± 0.7 pS and 0.76 ± 0.04 ms, respectively (n = 5), and the decrease in open probabilities (NPo) caused by desensitization was 38.2 ± 7% (n = 7) during the first 2 min of recording. With ET-1 in the pipette, the decrease in NPo became more pronounced (Fig. 1A). NPo decreased from 0.14 ± 0.003 to 0.03 ± 0.01 during the first 2 min of cell-attached recordings (n = 5; P < 0.01), indicating that ET-1 inhibited GIRK channels located in the same patch membrane. By contrast, channel activities were unaffected when ET-1 was applied to the bath solution after the channel activity reached a steady state (Fig. 1B). NPo values before and after ET-1 application were 0.10 ± 0.05 and 0.09 ± 0.05, respectively, which were not significantly different (n = 5; P > 0.05); results are summarized in Fig. 1C. The failure of bath-applied ET-1 to inhibit GIRK channels in the patch membrane indicates that activation of GqPCR in the membrane outside the patch does not cause a significant reduction in PIP2 within the patch. These findings suggest that PIP2 does not diffuse freely along the cell membrane and that PIP2 depletion induced by the receptor-mediated mechanism occurs in a highly localized manner adjacent to GqPCR.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ET-1 applied with a patch pipette or into the bath. IGIRK was activated by the pipette application of ACh at a holding potential of -80 mV. (A) The application of ET-1 by patch pipette markedly decreased GIRK channel activity. (a and b) Single-channel currents on an expanded time scale are shown. (B) Bath application of ET-1 outside the patch pipette did not inhibit GIRK channels. ET-1 was applied to the bath for the indicated period. (C) Changes in open probability (NPo) after ET-1 was applied by the patch pipette (Left) or into the bath (Right). Values are means ± SEM for five cells. *, P < 0.01 vs. control.

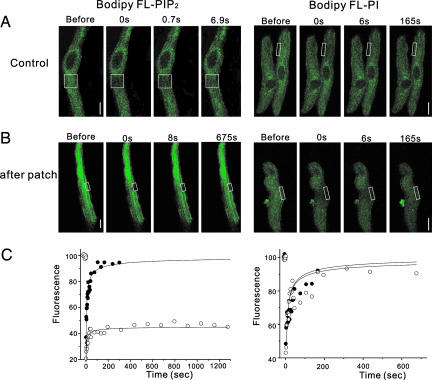

The Lateral Mobility of PIP2 in Cardiac Myocyte Membranes Is Extremely Low. The diffusion kinetics of PIP2 were studied by using the FRAP technique under a scanning confocal microscope in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells loaded with BODIPY-labeled PIP2 (7). The results of previous studies suggest that the diffusion rate of PIP2 is similar to those of other freely diffusible membrane labels, including 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine and BODIPY-labeled phosphatidylcholine (average ≈1–4 μm2/s) (15–17). When FRAP was performed on myocytes loaded with BODIPY-labeled PIP2, fluorescence recovered within 60 s without a significant immobile fraction (Fig. 2A Left), which is consistent with a previous observation in cultured neurons (7). When recovery curves were fitted by using a 1D diffusion equation (refs. 18 and 19 and see analysis of FRAP in Supporting Text) to determine the D, D was found to be 2.1 ± 0.1 μm2/s for PIP2 (Fig. 2C Left, •), which is similar to the published D values for these labels (7, 15–17).

Fig. 2.

FRAP revealed low PIP2 mobility. (A) Myocytes were loaded with BODIPY FL-PIP2 (Left) or BODIPY FL-PI (Right). Selected fluorescence images from typical sequences were recorded immediately after bleaching and at various times thereafter. Square boxes indicate the bleached areas. (Scale bars: 5 μm, Left;10 μm, Right.) (B) The same sequential images as shown in A after patch break-in. (Scale bars: 8 μm, Left; 10 μm, Right.) (C) Fluorescence intensities of BODIPY FL-PIP2 (Left) and BODIPY FL-PI (Right) in recovery after bleaching are plotted versus time. A least-squares fit of Eq. 1 (see Materials and Methods) to experimental data is indicated by the line. The curves display kinetics allowing the determination of a single D (see Materials and Methods). FRAP series before (•) and after (○) patch break-in are indicated.

However, it was not clear whether estimating the D of PIP2 in this way represents the lateral mobility of PIP2, because PIP2 labels were not well localized to the surface membrane but were found equally in cytoplasm. We suspected that free unbleached labels abundant in the cytosol or internal membranes incorporate rapidly into bleached spots and thus cause D to be overestimated. To avoid this problem and obtain an accurate measure of the lateral mobility of PIP2 along the membrane, a different experimental approach was required. So, we attempted to wash out free labels in cytosol by making whole-cell patches with an ordinary internal solution after myocytes were loaded with BODIPY-labeled PIP2. After patch break-in, fluorescence signals decreased gradually, and the signals from the central part of the cell image tended to diminish earlier than those on the periphery, indicating the presence of cytosolic-free labels that are readily washed out by dialysis with pipette solutions. In this configuration, FRAP was significantly delayed, and even after 20 min >60% of fluorescence was not recovered (Fig. 2 B and C Left). This delay was consistently observed when FRAP was performed >10 min after patch break-in (n = 8), which indicated that the fast recovery observed in PIP2-loaded cells (Fig. 2 A and C Left) was caused by free labels in the cytosol, and that the lateral mobility of PIP2 in surface membrane is extremely low. To exclude the possibility that low mobility of PIP2 shown in Fig. 2 Left is the result of an artifact produced by patch break-in or by some unexpected property of the fluorescent label, BODIPY, we performed the same series of experiments with BODIPY-labeled PI (Fig. 2 Right). In this case, when FRAP was performed, fluorescence recovered rapidly without significant immobile fraction, and this was not changed by patch break-in. D for PI was calculated to be 5.8 ± 0.3 μm2/s (n = 5).

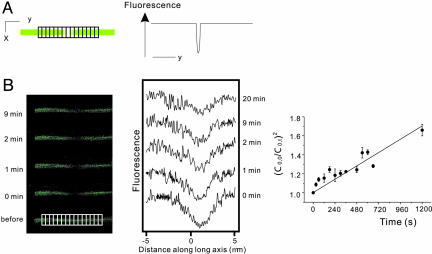

We could not determine D by using Eq. 1 (see Supporting Text) from the recovery profile shown in Fig. 2C Left (○), because the immobile fraction was too large (19). We used the method described by Mullineaux et al. (20) to fit the data, in which the images were integrated across the width of the longitudinal band in the x direction (Fig. 3A). From the images shown in Fig. 2B Left, single longitudinal bands were obtained as shown in Fig. 3B Left, and the fluorescence profiles were derived from the bands (Fig. 3B Center). Just after bleaching, ≈80–90% of fluorescence was lost at the center of the bleached spot and the bleaching profile was Gaussian, with a half-width (1/e2) of ≈1–4 μm. With time, the bleaching profile spread, becoming broader and shallower, indicating that unbleached PIP2 diffused into the bleached area. According to the 1D diffusion equation, the D of PIP2 can be calculated from time-dependent changes of the maximum bleach depth (ref. 20 and Supporting Text), as shown in the plots in Fig. 3B Right. D was calculated to be 0.00039 ± 0.000038 μm2/s (n = 6). These values are 104 times smaller than the value obtained before washout cytosolic fluorescence with patch pipettes.

Fig. 3.

Calculation of D for PIP2 from the time dependence of the maximum bleach depth. (A)(Left) The fluorescence from a cell is imaged in the x-y plane. The image shows a photobleached area across the cell membrane in the X direction. (Right) The image is integrated across the full width of the cell membrane in the X direction to give a 1D bleaching profile (fluorescence versus position on the long axis of the cell membrane). (B)(Left) Selected fluorescence images of single longitudinal band from the FRAP series shown in Fig. 2B Left. (Center) 1D bleaching profiles derived from the sequences of fluorescence images shown in Left.(Right) A plot of (C(y=0,t=0)/C(y=0,t)) against time in the measurement series shown in Left and Center should give a straight line with gradient  , where R0 is the initial half-width (1/e)2 of the bleach.

, where R0 is the initial half-width (1/e)2 of the bleach.

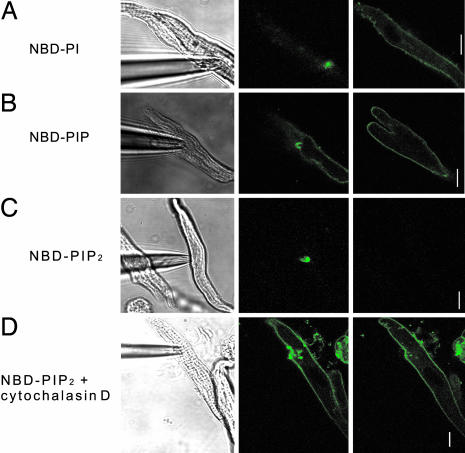

In spite of the fact that FRAP is a method used widely to measure diffusion of lipid molecules, we found that the reliability of the results seems to be limited because overloaded dyes are distributed in the area where the endogenous lipid molecules are not present or are metabolized to other forms in cells. To overcome these problems and visualize lateral diffusion more directly, we developed another technique. We attempted to introduce the dye locally by attaching the patch pipette filled with the solution containing dye to the surface membrane and monitored whether or not the entire cell membrane became fluorescent. Because the source of the dye is confined to the small area in the patch in this configuration, visualization of the entire cell membrane should represent that the dye was supplied by lateral diffusion. For this experiment, we found that NBD-labeled lipids are suitable, because they are practically nonfluorescent in aqueous suspensions, but become fluorescent in membranes (21), so that we could make sure whether loading of the dye to the membrane was successful by observing whether the area of the membrane inside the patch pipette became bright. When a patch pipette including NBD-labeled PI or PIP was attached to the myocyte, we could readily observe the bright fluorescence signals from the membrane patch, and then the entire membrane became visible, indicating that lateral mobility of these dyes is rapid (Fig. 4 A and B). Furthermore, the fluorescent intensity increased as time passed. However, when NBD-labeled PIP2 was included in the pipette, it was confined mostly in the patch membrane (Fig. 4C), indicating that NBD-labeled PIP2 is not as mobile as NBD-labeled PI or NBD-labeled PIP. To examine the possibility that the low mobility of PIP2 involves their binding to cytoskeletal proteins, we examined the effect of disrupting actin microfilament by using cytochalasin D. After treatment with cytochalasin D (10 μM), NBD-labeled PIP2 in the patch pipette rapidly diffused over the entire membrane (Fig. 4D), indicating that actin cytoskeletons are responsible for the low mobility of PIP2. It could be argued that the failure of PIP2 loading with the patch pipette is not caused by slow lateral diffusion, but by slow incorporation of PIP2 into the surface membrane. To exclude this possibility, we examined the time courses of PIP2 loading before and after cytochalasin D pretreatment and confirmed that incorporation of PIP2 into the surface membrane is not significantly affected by cytochalasin D pretreatment (Fig. 8).

Fig. 4.

Loading of fluorescent phosphoinositides via a patch pipette. Myocytes were attached to a patch pipette containing NBD-labeled PI (A), PIP (B), or PIP2 (C and D). The images in A, B, and D were taken <5 min after attachment, whereas images in C were taken after 15 min. All images were taken under identical conditions (100% power, 2% transmission). (Left) Electrode attachment to myocytes. (Center and Right) The fluorescent images taken at plane where meniscus or whole-cell image is most well visualized, respectively. (D) Cytochalasin D (10 μM) was pretreated for 3 h before pipette attachment. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

Simulation Study Shows Low Mobility of PIP2 Is a Key for Receptor-Specific Signal. To investigate how temporal and spatial profiles of PIP2 concentration changes are affected by the mobility of PIP2,we simulated the diffusion model. We assumed that (i) initially PIP2 molecules are homogeneously distributed over the 2D lipid bilayer (10 μM) (2) and undergo Fickian diffusion laterally as PIP2 is depleted by the activation of PLC; (ii) PLC is located at the origin (r = 0) of the 2D polar coordinates, and its enzymatic activity is spatially localized in a small domain (r < 50 nm; referred to as PLC domain), and each domain is 2 μm apart; and (iii) PLC activity follows the Michaelis–Menten equation with a constant Vmax (20 μM/s) (22) over the PLC domain with Km value of 5 μM (22). Time-dependent changes in [PIP2] at varying distances from the PLC domain were calculated over 4 min according to Eq. 11 (see Supporting Text), while D was varied from 0.2 to 0.00002 μm2/s. Details about the numerical scheme for calculating PIP2 diffusion in lipid bilayer are presented in Supporting Text. The results are illustrated (Fig. 5A) with a gray density gradient, so that the x axis and y axis represent spatial and time-dependent changes, respectively. At D = 0.2 μm2/s, concentration changes occurred almost uniformly and slowly progressed as time passed, indicating that PIP2 depletion induced by PLC is immediately filled up by diffusion. As D was decreased, depletion started around the PLC domain and spread toward periphery along time, resulting in characteristic spatial profiles changing with time. Localized fashion of PIP2 depletion became prominent at D = 0.0002 μm2/s, and the area of depletion did not spread over 300 nm from the center of the PLC domain even after 4 min. In Fig. 9, where we plotted spatial profiles of PIP2 concentrations calculated at 50, 120, and 240 s after PLC activation, it was noted that more profound depletion was achieved and more localized when the mobility was further decreased.

To demonstrate the effect of spatial distance from the PLC domain on PIP2 depletion profiles, changes in PIP2 concentrations calculated at various spatial distances from the PLC domain are illustrated in Fig. 5B. When D = 0.2 μm2/s, there was no spatial difference in depletion kinetics. Depletion profiles obtained at 0.05, 0.07, 0.1, 0.15, 0.25, and 0.35 μm from the center of the PLC domain were completely overlapped, and time courses were almost linear. At D = 0.02 μm2/s, the depletion rate near the PLC domain became faster than on the periphery, but the spatial difference was not yet large. When D was decreased to 0.002 μm2/s, the depletion time course showed two distinctive phases (the early fast and late slow phases) and the proportion of the fast phase got larger as the distance from the center grew smaller. When D was further decreased, the spatial difference in depletion kinetics grew larger, and the depletion kinetics at position remote from the center became distinctive from that near the center. At positions near the PLC domain, PIP2 depletion developed rapidly to a greater extent, whereas at positions remote from the PLC domain, depletion started after some lag period and progressed very slowly. Such slowing caused a decrease in the magnitude of depletion for a given time.

It is interesting to note that the depletion profiles at different positions became very similar with the receptor-specific patterns of GqPCR-mediated GIRK inhibition shown previously (figure 2D in ref. 6) at D = 0.0002 μm2/s (Fig. 5B). Rapid and profound inhibitions induced by ET-1 and prostaglandin F resemble depletion profiles at positions near PLC, whereas the inhibition by angiotensin II showing small magnitude and slow time course with the characteristic lag resembles depletion profiles at positions remote from PLC. Because this striking resemblance was found at the D value comparable with the value obtained by experiment (0.00025–0.00039 μm2/s), the idea that diffusion-limited localization of PIP2 is the mechanism of receptor-specific inhibition of GIRK could be further supported. In other words, PIP2 depletion is localized adjacent to GqPCRs because of its low mobility, and spatial proximity of GqPCR and the target protein underlie the receptor specificity of PIP2-mediated signaling. This idea is illustrated in Fig. 6. The GIRK channel senses PIP2 depletion induced by the activation of GqPCRs located at different distances, and the influence of each GqPCR depends on the coupling proximity of GqPCR with the channel. At low mobility, the GqPCR located at a distance more than several hundred nanometers from the channel can hardly affect channel activity. The closer the GqPCR is located, faster and greater inhibition can be induced.

It has been reported recently that PIP2 depletion is responsible for the mechanism of receptor-mediated inhibition of M channels, possibly encoded by KCNQ2/3 (23, 24). However, it was shown that inhibition of the M channel appeared when a muscarinic agonist was added to the bath solution, while channel activities were recorded in cell-attached mode (25, 26), which is inconsistent with our results. We do not know the reason for this discrepancy, but suggest the following explanations. First, this discrepancy may be caused by two important differences between M current and GIRK current. First, it has been shown that the affinity of M channels for PIP2 is markedly lower than the affinity of GIRK channels for PIP2 (24). This means that GqPCR-mediated M-current inhibition would appear at a smaller decrease in PIP2 concentration, and thus receptor activation could affect a larger area. Therefore, the receptor-mediated inhibition of M channels does not have a localized nature. Another difference is that M channels have low specificity for PIP2 and are activated by various PIPs with similar efficacy (24), whereas GIRK channels have a preference for PIP2 (27). Thus, it is possible that M channels may be affected by factors other than PIP2 that can diffuse more rapidly than PIP2. The second possibility concerns cell-type differences. Because there is no evidence that the physical properties of PIP2 are dissimilar from those of other membrane lipids (28), the low mobility of PIP2 observed in our study may represent the presence of some mechanism that restricts PIP2 movement. Then, if such a mechanism is not much developed in superior cervical ganglion neurons or oocytes overexpressing KCNQ2/3, PIP2 can diffuse more freely in M channel-expressing cells. Moreover, these two possibilities are not mutually exclusive, and both could be involved in the distinction between kinetics and localization of receptor-mediated M-current inhibition in neurons and those of GIRK inhibition in cardiac myocytes.

Although the role of PIP2 depletion in GqPCR-mediated signaling has been confirmed in various cellular processes, ranging from ion channel gating to cytoskeletal rearrangement, it remains controversial as to whether changes in [PIP2] really occur in response to GqPCR activation. One recent study using a nonradioactive HPLC method to quantify anionic phospholipids in intact heart tissue samples showed that total PIP and PIP2 levels do not change, or even increase, when GqPCRs are activated by carbachol, phenylephrine (PE), or ET-1 (4). Another discrepancy was found between the potencies of GqPCR-induced GIRK current inhibition presented in our earlier work (6) [ET-1 > prostaglandin F2α > PE > angiotension II > bradykinin (BK)] and PIP2 hydrolysis potencies measured in rat cardiomyocytes (ET-1 > BK ≈ PE, ref. 29). The present study provides an answer to these inconsistencies by providing experimental evidence with a theoretical basis. In our model, PIP2-mediated effects on target proteins are determined by changes in [PIP2] sensed at the position of the target protein, not by changes in total PIP2 content, and thus PIP2-mediated effects do not necessarily parallel PIP2 hydrolysis potency. Taken together, it can be concluded that the nature of PIP2-mediated signaling is determined by four factors; (i) receptor-mediated changes in PIP2 concentrations, (ii) PIP2 mobility, (iii) spatial proximity between a receptor and a PIP2-interacting molecular target, and (iv) the affinity of a PIP2-interacting molecular target for PIP2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Korea Research Foundation Grant 2003-041-E20008 and Ministry of Science and Technology Grant 2004-02433. J.-Y.Y. and D.L. were supported by the BK21 Program of the Korean Ministry of Education.

Author contributions: W.-K.H. designed research; H.C., Y.A.K., J.-Y.Y., D.L., and S.H.L. performed research; J.H.K. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; H.C. and W.-K.H. analyzed data; and H.C. and W.-K.H. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: GIRK, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+; GqPCR, Gq protein-coupled receptor; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIP, phosphatidylinositol 4-monophosphate; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; FRAP, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; ACh, acetylcholine; ET-1, endothelin 1; BODIPY, 4,4-difluro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-propionic acid; NBD, 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole; D, diffusion coefficient; BK, bradykinin.

References

- 1.Hilgemann, D. W., Feng, S. & Nasuhoglu, C. (2001) Science STKE 111, RE19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin, S., Wang, J., Gambhir, A. & Murray, D. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 31, 151-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augustine, G. J., Santamaria, F. & Tanaka, K. (2003) Neuron 40, 331-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasuhoglu, C., Feng, S., Mao, Y., Shammat, I., Yamamato, M., Earnest, S., Lemmon, M. & Hilgemann, D. W. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 283, C223-C234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irvine, R. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, R308-R310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, H., Lee, D., Lee, S. H. & Ho, W. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4643-4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rheenen, J. & Jalink, K. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell. 13, 3257-3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haugh, J. M., Codazzi, F., Teruel, M. & Meyer, T. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151, 1269-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, H., Youm, J. B., Ryu, S. Y., Earm, Y. E. & Ho, W. K. (2001) Br. J. Pharmacol. 134, 1066-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Traynor-Kaplan, A. E., Thompson, B. L., Harris, A. L., Taylor, P., Omann, G. M. & Sklar, L. A. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 15668-15673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soejima, M. & Noma, A. (1984) Pflügers Arch. 400, 424-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakmann, B., Noma, A. & Trautwein, W. (1983) Nature 303, 250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logothetis, D. E., Kurachi, Y., Galper, J., Neer, E. J. & Clapham, D. E. (1987) Nature 325, 321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurachi, Y., Ito, H. & Sugimoto, T. (1990) Pflügers Arch. 416, 216-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yechiel, E. & Edidin, M. (1987) J. Cell Biol. 105, 755-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulbright, R. M., Axelrod, D., Dunham, W. R. & Marcelo, C. L. (1997) Exp. Cell Res. 233, 128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacia, K., Scherfeld, D., Kahya, N. & Schwille, P. (2004) Biophys. J. 87, 1034-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellenberg, J. & Lippincott-Schwartz, J. (1999) Methods 19, 362-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellenberg, J., Siggia, E. D., Moreira, J. E., Smith, C. L., Presley, J. F., Worman, H. J. & Lippincott-Schwartz, J. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 138, 1193-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullineaux, C. W., Tobin, M. J. & Jones, G. R. (1997) Nature 390, 421-424. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chattopadhyay, A. (1990) Chem. Phys. Lipids 53, 1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sternweis, P. C., Smrcka, A. V. & Gutowski, S. (1992) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 336, 35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suh, B. C. & Hille, B. (2002) Neuron 35, 507-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, H., Craciun, L. C., Mirshahi, T., Rohacs, T., Lopes, C. M., Jin, T. & Logothetis, D. E. (2003) Neuron 37, 963-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrion, N. V. (1993) Neuron 11, 77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selyanko, A. A., Stansfeld, C. E. & Brown, D. A. (1992) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 250, 119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohacs, T., Lopes, C. M., Jin, T., Ramdya, P. P., Molnar, Z. & Logothetis, D. E. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 745-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner, M. L. & Tamm, L. K. (2001) Biophys. J. 81, 266-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clerk, A. & Sugden, P. H. (1997) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 29, 1593-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.