Abstract

We have previously shown that the putative mammalian retromer components sorting nexins 1 and 2 (Snx1 and Snx2) result in embryonic lethality when simultaneously targeted for deletion in mice, whereas others have shown that Hβ58 (also known as mVps26), another retromer component, results in similar lethality when targeted for deletion. In the current study, we address the genetic interaction of these mammalian retromer components in mice. Our findings reveal a functional interaction between Hβ58, SNX1, and SNX2 and strongly suggest that SNX2 plays a more critical role than SNX1 in retromer activity during embryonic development. This genetic evidence supports the existence of mammalian retromer complexes containing SNX1 and SNX2 and identifies SNX2 as an important mediator of retromer biology. Moreover, we find that mammalian retromer complexes containing SNX1 and SNX2 have an essential role in embryonic development that is independent of cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor trafficking.

Keywords: embryonic lethality, Hβ58, vacuolar protein sorting, cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor, yolk sac

A membrane coat retromer complex mediates endosome-to-Golgi trafficking of the vacuolar hydrolase receptor Vps10p in yeast (1). Retromer complexes are comprised of Vps35p, Vps29p, Vps26p, Vps5p, and Vps17p. Mammalian orthologs for each of these proteins, except Vps17p, have been identified, thereby suggesting that mammalian cells may use a trafficking complex similar in molecular composition to the yeast retromer complex. Furthermore, recent studies employing cell lines indicate that mammalian retromer complexes participate in trafficking of the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR), the functional homolog of Vps10p, suggesting that the function of retromer complexes may also be conserved between yeast and mammals (2–4).

Sorting nexin (SNX) 1 and SNX2 are 63% identical at the amino acid level and are both mammalian orthologs of Vps5p (5). Despite their homology to Vps5p, the function of SNX1 and SNX2 in mammalian cells is poorly understood. Originally discovered in a screen designed to identify molecules involved in lysosomal sorting of the epidermal growth-factor receptor (6), SNX1 has also been shown to associate with a number of different receptors as well as other putative mammalian retromer components, including SNX2, in cultured cell lines (5, 7, 8). However, the functional implications of these interactions remain obscure, and it has been difficult to differentiate between potential roles for SNX1 and SNX2 in retromer complexes versus roles for these sorting nexins separable from retromer activity. In the present study, we sought to define the participation and activity of SNX1 and SNX2 in mammalian retromer complexes through genetic analyses in mice. We provide genetic evidence for the involvement of these sorting nexins in mammalian retromer complexes and reveal an essential role for SNX2 in retromer activity during embryonic development.

Methods

Animals. Generation of Snx1-deficient (Snx1tm1Mag) and Snx2-deficient (Snx2tm1Mag) mice was described in ref. 9. Hβ58-deficient (Vps26tm1Cos) mice were a gift from Frank Costantini (Columbia University, New York) and were identical in phenotype to those generated by a previously described gene trap, which was presumed to disrupt Hβ58 (10, 11). All mice were maintained on a mixed genetic background. For embryonic analysis, noon on the day of plug detection was counted as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5).

Genotyping. The Snx1 and Snx2 wild-type and targeted alleles were detected as described in ref. 9, except that PCRs for the different alleles were run separately. Genotyping primers and PCR conditions for Hβ58 amplification are described in Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

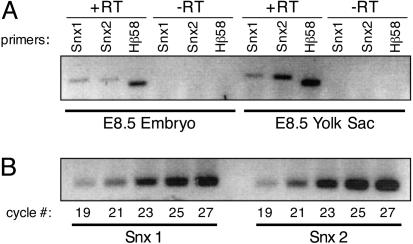

Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR. Total RNA was generated from a litter of E8.5 wild-type CD-1 embryos or their yolk sacs by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and were reverse transcribed, as described in Supporting Methods. One microliter of each RT reaction was amplified in a 50-μl PCR by using primers described in Supporting Methods. RT-PCRs were performed under identical conditions for 25 cycles and with a 55°C annealing temperature. PCR products were analyzed with multianalyst software (Bio-Rad). EST IMAGE clones nos. 578066 (Snx1) and 891452 (Snx2) were used as cDNA templates to compare the PCR amplification ability of the Snx1 and Snx2 primers used in the RT-PCRs.

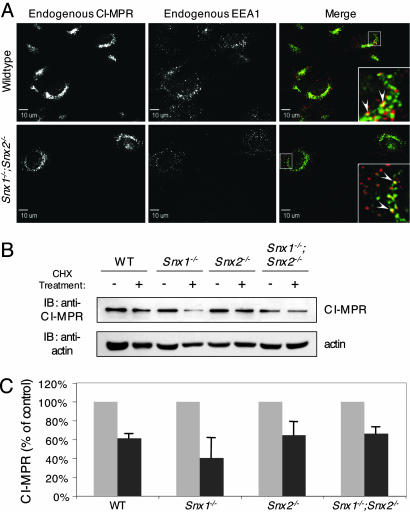

Cell Lines and Assays. Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated as described in ref. 9, except that Hβ58-/- embryos were dissected at E8.5. We established permanent, monomorphic, contact-inhibited MEF cell lines by subculturing cells continuously until they emerged from a crisis period of slow growth (≈25 passages) as described in ref. 12 and 13. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed as described in ref. 9 by using polyclonal (anti-rat) anti-CI-MPR antibodies provided by Nancy Dahms (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) and by J. Paul Luzio (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, U.K.), a monoclonal anti-EEA1 antibody (BD Biosciences), and AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Images were collected by using an Olympus DSU spinning disk confocal microscope configured with an IX71 fluorescent microscope fitted with a PlanApo ×60 oil objective and Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera. Fluorescent images of X-Y sections at 0.15 μm were collected sequentially by using Intelligent Imaging Innovations slidebook 4.1 software. The final composite images were created by using photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Western blots for CI-MPR detection were performed on lysates prepared from untreated cells or cells treated for 17 h with 40 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma). Western blots for mVPS35 detection were performed by using a polyclonal (anti-human) anti-Vps35 antibody (5) provided by Carol Haft (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda). Membranes were probed with an anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to control for equal loading of lysates. Immunoblots were developed with ECL-plus (Amersham Pharmacia), imaged by autoradiography, and quantified by using a Fluor-S Imager (Bio-Rad).

Yolk Sac and Visceral Endoderm Immunostaining. For analysis of CI-MPR localization in yolk sac cells, embryos and extraembryonic yolk sacs were dissected at E8.5, and yolk sacs were processed for whole-mount immunostaining. Isolation and preparation of visceral endoderm cells for analysis of CI-MPR localization is described in Supporting Methods. Yolk sacs and visceral endoderm cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy, as described in ref. 9 by using an anti-CI-MPR antibody from P. Luzio, and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired by using a Leica DML fluorescence microscope and spot rt software (Diagnostic Instruments).

Results and Discussion

Genetic Interactions of Mammalian Retromer Components. Mice doubly deficient for Snx1 and Snx2 were previously shown to die at midgestation with developmental delay, although the single mutants are fully viable (9). Mice deficient for the ortholog of Vps26p, Hβ58, die with a similar phenotype to Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- embryos (10, 11). To determine whether these genes are epistatic and provide genetic evidence for the existence of a mammalian retromer complex containing SNX1 and SNX2, we crossed Snx1, Snx2, and Hβ58 mutant mice together.

The viability of Snx1-/- and Snx2-/- mice indicates that the putative mammalian retromer complex does not require both SNX1 and SNX2 to function during development. Likewise, mice heterozygous for Hβ58 develop without any overt abnormalities. However, we recovered only 10% of expected Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- mice from Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx2-/- or Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx2+/- matings, indicating that 90% of Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos die during development (Table 1). This result demonstrates a strong genetic interaction between Snx2 and Hβ58 and suggests that SNX2 plays a critical role in retromer function during development. Conversely, no lethality was associated with Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- mice or embryos generated from Snx1+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1-/- or Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1+/- matings (Table 1), indicating that SNX1 has a weaker interaction with Hβ58 and the retromer complex compared with SNX2.

Table 1. Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos result in 90% lethality.

| Genotype | Live progeny (expected progeny) |

|---|---|

| Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/+ | 77 (51.25) |

| Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- | 61 (51.25) |

| Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/+ | 61 (51.25) |

| Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- | 6 (51.25) |

| Snx1+/-;Hβ58+/+ | 22 (20.25)* |

| Snx1+/-;Hβ58+/- | 15 (20.25)* |

| Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/+ | 25 (20.25)* |

| Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- | 19 (20.25)* |

Shown are the number of genotypes of live progeny from 28 litters generated by Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx2-/- or by Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx2+/- matings and 11 litters generated by Snx1+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1-/- or by Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1+/- crosses. Note the 90% lethality for Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- animals (P < 0.001 by χ2 test). *, the number of genotypes of live progeny from 11 litters generated by Snx1+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1-/- or by Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1+/- matings. No significant lethality was detected for Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- animals.

Although Snx1-/-;Snx2+/- mice are viable, 40% of Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- embryos were previously reported to die during development, indicating that SNX1 and SNX2 are not completely functionally redundant (9). Strikingly, we found that no Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- mice generated from Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1-/-;Snx2+/- matings survived development (Table 2). On the other hand, Snx1-/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- mice generated from Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- matings were viable (Table 2). Therefore, whereas SNX1 does not seem to have as critical a role in retromer activity as does SNX2, SNX1 appears to be present in retromer complexes during development as evidenced by its genetic interaction with Snx2 and Hβ58. These data provide genetic evidence that SNX1 and SNX2 have an important role in mammalian retromer activity.

Table 2. Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos result in 100% lethality.

| Genotype | Live progeny (expected progeny) |

|---|---|

| Snx1+/-;Snx2+/+;Hβ58+/+ | 29 (25) |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2+/+;Hβ58+/- | 30 (25) |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/+ | 52 (50) |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- | 53 (50) |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/+ | 16 (15) |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- | 0 (15) |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/+ | 27 (23.5)* |

| Snx1+/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- | 19 (23.5)* |

| Snx1-/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/+ | 28 (23.5)* |

| Snx1-/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- | 20 (23.5)* |

Shown are the number of genotypes of live progeny from 24 litters generated by Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1-/-;Snx2+/- matings and 11 litters generated by Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- matings. Note the complete lethality for Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- animals (P < 0.005 by χ2 test). The expected numbers account for 40% lethality of Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- embryos, as reported in ref. 9. *, the number of genotypes of live progeny from 11 litters generated by Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- × Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- matings. No significant lethality was detected for Snx1-/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- animals.

Embryonic Phenotypes. To determine the timing of Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- and Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryonic lethality and to compare the phenotypes of those embryos to the previously described phenotypes of Hβ58-/- and Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- embryos (9–11), we performed embryonic dissections (Fig. 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Live Snx2-/-; Hβ58+/- embryos were recovered as late as E18.5 with hemorrhage and occasional exencephaly. The hemorrhagic events were evident at different sites in the embryos; blood was occasionally observed in the head with accompanying exencephaly or craniofacial abnormalities, whereas other embryos displayed prominent blood in the abdomen rather than the head. Those Snx2-/-; Hβ58+/- embryos unaffected by hemorrhage and exencephaly (≈10%) did not display any overtly abnormal phenotypes and were viable and fertile after birth.

Alternatively, both Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- and 40% of Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- embryos died in two waves during development. Both classes of embryos displayed an early wave of lethality (≈E8.5) that was phenotypically similar to the lethality observed in association with Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- and Hβ58-/- embryos (9–11). These embryos were morphologically under-developed and appeared to undergo developmental delay beginning at E7.5. The second class of lethality observed with Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- and 40% of Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- embryos occurred ≈E13.5 and was associated with exencephaly. This phenotype, however, was more severe than the occasional exencephaly seen in Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos because lethality occurred several days later in the latter case. In both Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- and 40% of Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- embryos, the two waves of lethality at E8.5 and E13.5 are equally represented.

Our phenotypic and genetic data indicate that SNX2 is more critical for retromer function during development than SNX1, although SNX1 does participate in retromer activity as evidenced by the complete lethality associated with Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos versus the 90% lethality associated with Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos. This result is surprising because SNX2 has not been shown to interact with any of the putative retromer components other than itself and SNX1 (5, 14). The discrepancy between our genetic evidence for SNX2 participation in retromer activity and the lack of evidence for SNX2 interaction with retromer proteins may be explained by species or temporal differences in SNX2 participation in retromer activity. This discrepancy also may illustrate important systemic differences between animal models and cultured cell lines. Clearly, however, additional studies are needed to define the role of SNX2 in mammalian retromer complexes.

Snx2 mRNA Is More Abundant Than Snx1 mRNA in the Extraembryonic Yolk Sac During Development. Based on the severe lethality and phenotypes we observed in Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- and Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos but not in Snx1-/-;Hβ58+/- or Snx1-/-;Snx2+/-;Hβ58+/- embryos, we hypothesized that SNX2 is more abundant than SNX1 during development. To test this hypothesis, we performed RT-PCR on embryonic and extraembryonic tissues dissected from E8.5 wild-type embryos (Fig. 1A) by using primers that are equally capable of amplifying Snx1 or Snx2 cDNAs (Fig. 1B). Our results demonstrate that Snx2 mRNA is more abundant than Snx1 mRNA in the extraembryonic yolk sac at midgestation.

Fig. 1.

Snx2 mRNA is more abundant than Snx1 mRNA in extraembryonic yolk sacs at midgestation. (A) RT-PCR. Snx1, Snx2, and Hβ58 were amplified by RT-PCR from a litter of E8.5 wild-type embryos or their yolk sacs. (-RT) indicates mock RT reactions in which no reverse transcriptase was used. Equal amounts of +/-RT templates were used in each PCR, and identical amplification conditions were used for all samples. This experiment was repeated three times, and the quantitative averages of the data reveal that Snx2 mRNA is expressed at ≈72% of Snx1 mRNA levels in the embryo, but Snx2 mRNA levels are ≈225% of Snx1 mRNA levels in the yolk sac. (B) PCR amplification of Snx1 and Snx2 cDNA for assessing primer pair amplification ability. Snx1 or Snx2 cDNAs (0.15 ng) were PCR amplified with their gene-specific primers for varying numbers of cycles to demonstrate the comparable ability of the primers to amplify equal amounts of template.

The abundance of Snx2 mRNA in the E8.5 yolk sac is particularly interesting because Hβ58 has also been shown to be highly expressed in extraembryonic tissues from E6.5 throughout midgestation by in situ hybridization (10). Lee et al. hypothesized that normal expression of Hβ58 may be required in extraembryonic tissues for the proper development of embryonic ectoderm. This hypothesis arose from the paradoxical observation that Hβ58 depletion leads to growth retardation in the embryonic ectoderm at E7.5, although the gene is endogenously expressed at much lower levels there than in the extraembryonic visceral endoderm. The visceral endoderm and yolk sac as a whole have both nutritive and inductive effects on developing embryos (reviewed in refs. 15–17). Because Snx2 and Hβ58 are most highly expressed in the yolk sac at midgestation, we propose that retromer complexes play a critical role in that tissue by contributing to normal embryonic growth and development.

If retromer activity in the yolk sac is critical for normal embryonic development as we hypothesize, our phenotypic data may largely be explained by the availability of retromer components in extraembryonic tissues at midgestation. Retromer complexes can presumably contain either SNX1 or SNX2, as evidenced by the viability of Snx2-/- and Snx1-/- mice (9). When SNX2, which is more abundant than SNX1 in the yolk sac, is depleted and relatively low endogenous SNX1 levels are reduced by half, enough functional retromer complexes are still able to be assembled with the remaining SNX1 protein to support 60% of Snx1+/-;Snx2-/- embryonic survival beyond E13.5. However, if Hβ58 levels are also reduced by half in this context, the resulting Snx1+/-;Snx2-/-;Hβ58+/- embryos all die by E13.5, thereby demonstrating the importance of Hβ58 levels for retromer assembly at midgestation. Altogether, our molecular and genetic data indicate the significance of SNX1 and Hβ58 dosage levels in the yolk sac for retromer activity, which is revealed only in the context of SNX2 depletion.

CI-MPR Is Not Significantly Mistrafficked in Hβ58, Snx1-, or Snx2-Deficient Embryonic Fibroblasts, Yolk Sacs, or Visceral Endoderm. The three classes of phenotypes revealed by our genetic crosses indicate that three distinct checkpoints involving retromer function are critical for embryonic survival, suggesting that mammalian retromer complexes serve multiple roles during development. Mammalian cell culture systems implicate retromer complexes in trafficking of the CI-MPR from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network, analogously to the retrograde trafficking of Vps10p mediated by retromer complexes in yeast. Several recent reports have described defective CI-MPR trafficking in small interfering RNA-mediated SNX1- or Hβ58-depleted HeLa cells and in Hβ58-/- ES cells (2–4). These studies report severe CI-MPR mislocalization with an increased rate of degradation, presumably due to mistrafficking of CI-MPR to lysosomes when retromer components are depleted in cells. We therefore recognized the importance of determining whether CI-MPR mistrafficking could be responsible for the phenotypes seen in our embryonic models of retromer disruption.

To assess the status of CI-MPR localization and stability in our retromer-deficient embryos, we generated multiple MEF cell lines derived from wild-type, Hβ58+/-, Hβ58-/-, Snx1-/-, Snx2-/-, and Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- embryos. We found no evidence of significant CI-MPR mislocalization as assessed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy with primary or permanent mutant MEF cell lines (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In each case, endogenous CI-MPR was predominantly localized in a perinuclear site, indicative of its function in the trans-Golgi network, as has been observed in multiple cell lines of human and mouse origin (2). We failed to observe cell-surface localization of CI-MPR in our retromer-deficient MEFs as seen in Hβ58-/- ES cells (4), nor did we observe significant cytoplasmic dispersal of CI-MPR as observed in SNX1- or Hβ58-small interfering RNA-treated HeLa cells (2, 3). Furthermore, we did not find evidence of increased colocalization between endogenous CI-MPR and the early endosomal marker EEA1 in Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- fibroblasts (Fig. 2A), as had been seen in Hβ58-small interfering RNA-treated HeLa cells (4). To determine whether loss of retromer components affects CI-MPR stability in our MEF lines, we assessed CI-MPR degradation (Fig. 2 B and C). Immunoblot analyses of lysates prepared from untreated cells or cells treated for 17 h with cycloheximide show no indication of significant receptor degradation. Together, our results strongly imply that CI-MPR is not mislocalized nor mistrafficked to lysosomes and degraded in our MEF cells derived from retromer-deficient embryos.

Fig. 2.

CI-MPR sublocalization and stability is unaltered in wild-type versus retromer-deficient MEF cell lines. (A) CI-MPR/EEA1 colocalization. Low passage, primary wild-type and Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- MEF lines were fixed and stained for endogenous CI-MPR (green) and EEA1 (red) and imaged by confocal microscopy. Insets are magnifications of boxed areas, and arrowheads indicate coincident labeling. (B) CI-MPR protein levels in Snx1-/-, Snx2-/-, and Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- MEFs. High passage, immortalized MEF lines were either left untreated or were treated with 40 μg/ml cycloheximide diluted in αMEM for 17 h. Cell lysates were then immunoblotted with an anti-CI-MPR antibody, followed by an anti-actin antibody to control for equal loading. (C) Quantification of CI-MPR stability in Snx1-/-, Snx2-/-, and Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- MEFs. Three separate experiments, such as those shown in B, were quantified, and the data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of CI-MPR remaining (dark gray bars) compared with untreated controls (light gray bars).

The discrepancy between the lack of CI-MPR mislocalization observed in our MEFs and the mislocalization reported by others in SNX1- or Hβ58-depleted HeLa cells (2–4) could be due to species differences (mouse versus human cells), developmental stage differences (embryonic versus adult cells), cell-type differences (fibroblasts versus epithelium-like cells), or technical differences (targeted mutations versus RNA interference treatment). Species or developmental stage differences cannot, however, account for the dissimilarities seen in CI-MPR trafficking between our Hβ58-/- MEFs and the Hβ58-/- ES cells described by others in ref. 4. However, it is important to note that fibroblasts are distinct from undifferentiated ES cells. Furthermore, our Hβ58-/- MEF cells were derived from embryos carrying a targeted mutation of the Hβ58 gene, whereas the Hβ58-/- ES cells used in previous studies were derived from a transgene insertion trap mouse line (11, 18), and it is likely that other linked genes were affected. Thus, cell type differences or technical differences in the derivation of Hβ58-/- MEFs versus Hβ58-/- ES cells could account for the phenotypic differences observed in CI-MPR trafficking between our studies.

Although retromer appears to be disabled in our MEF lines, as evidenced by virtual depletion of the core cargo-binding retromer component mVPS35 in our Hβ58-/- cell lines (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), alternative proteins such as TIP47, Rab9, or PACS-1 (19–21) could potentially compensate for retromer loss in our MEFs, thereby masking any subtle CI-MPR mistrafficking phenotype we might otherwise observe. To exclude this possibility, we assessed CI-MPR localization by using our mutant embryos themselves, thereby circumventing issues of cell line derivation and maintenance. Because of the particularly high levels of endogenous Hβ58 and Snx2 expression in the extraembryonic yolk sac at the time during which mutant embryos begin to show developmental delay (Fig. 1 A and ref. 10), we hypothesized that the yolk sac would be an important site for assessing CI-MPR mislocalization if it were occurring and contributing to the lethality of our retromer-depleted embryos. We dissected and immunostained whole yolk sacs from E8.5 Hβ58+/- and Hβ58-/- littermates and yolk sacs from E8.5 Snx1-/- and Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- littermates (Fig. 3 A–D). We found no evidence of mislocalization of CI-MPR in mutant versus control yolk sacs. In all cases, CI-MPR was found in a perinuclear location, similar to what we observed in our MEF lines and to what others have reported in other wild-type cell lines (2–4). We took an additional step to assess CI-MPR localization in a subset of extraembryonic cells by dissecting and immunostaining visceral endoderm surrounding the epiblast of E6.5 control and mutant embryos (Fig. 3 E–H). We chose visceral endoderm for analysis because Hβ58 is highly expressed in this cell layer at E6.5 (10). We detected no difference in immunostaining of CI-MPR in visceral endoderm from Snx1-/- versus Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- littermate embryos or from wild-type versus Hβ58-/- littermate embryos and again found CI-MPR localized in a perinuclear site similar to what we had observed in our MEF lines and in control and mutant yolk sacs. Altogether, the normal localization of CI-MPR in our mutant yolk sacs and visceral endoderm cells corroborates the normal localization and stability of CI-MPR observed in our MEF lines, thereby making the possibility very unlikely that our MEF lines adapted to retromer depletion in culture by using a compensatory mechanism for CI-MPR trafficking.

Fig. 3.

CI-MPR localization is unaltered in control versus mutant extraembryonic tissues. (A–D) CI-MPR localization in E8.5 extraembryonic yolk sacs. Hβ58+/- versus Hβ58-/- and Snx1-/- versus Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- littermate embryos were dissected and genotyped, whereas their yolk sacs were subjected to whole mount immunofluorescence analysis with an anti-CI-MPR antibody (green). Yolk sacs were mounted on glass slides with mounting media containing DAPI (blue) before imaging. (Magnification: ≈×40.) (E–H) CI-MPR localization in E6.5 visceral endoderm cells. Visceral endoderm was separated from the epiblasts of Snx1-/- versus Snx1-/-;Snx2-/- and Hβ58+/+ versus Hβ58-/- littermate embryos at E6.5. The embryos were genotyped, whereas clumps of visceral endoderm cells were cytospun onto glass slides and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis with an anti-CI-MPR antibody (green) and mounting media containing DAPI (blue) before imaging. (Magnification: ≈×100.)

Our data strongly suggest that mistrafficked CI-MPR is not responsible for lethality of retromer-depleted embryos. Importantly, if increased turnover of the CI-MPR were responsible for the embryonic phenotypes seen in our mouse models of retromer depletion, we might predict that CI-MPR-/- embryos would share similar phenotypes with our genetic combinations of Snx1-, Snx2-, and Hβ58-deficiency. However, CI-MPR-/- embryos do not suffer any embryonic hemorrhage, exencephaly, or lethality but rather exhibit overgrowth and postnatal lethality associated with heart abnormalities (22–24). These studies provide strong genetic evidence that CI-MPR mistrafficking and depletion are not likely causes of the phenotypes observed in our retromer-depleted embryos and indicate that the mechanism of retromer function during development awaits further elucidation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Costantini for Hβ58-deficient mice; Nancy Dahms, Ann Erickson (University of North Carolina), and J. Paul Luzio for anti-CI-MPR antibodies; Sundeep Kalantry for technical assistance with visceral endoderm isolation; and Stormy Chamberlain for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a National Research Service Award fellowship (to C.T.G.) and National Institutes of Health grants (to T.M. and J.T.).

Author contributions: C.T.G. and T.M. designed research; C.T.G. performed research; C.T.G. and J.T. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; C.T.G., J.T., and T.M. analyzed data; and C.T.G. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CI-MPR, cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor; En, embryonic day n; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; RT, reverse transcription; SNX, sorting nexin.

References

- 1.Seaman, M. N., McCaffery, J. M. & Emr, S. D. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 142, 665-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arighi, C. N., Hartnell, L. M., Aguilar, R. C., Haft, C. R. & Bonifacino, J. S. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165, 123-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlton, J., Bujny, M., Peter, B. J., Oorschot, V. M., Rutherford, A., Mellor, H., Klumperman, J., McMahon, H. T. & Cullen, P. J. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 1791-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seaman, M. N. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165, 111-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haft, C. R., de la Luz Sierra, M., Bafford, R., Lesniak, M. A., Barr, V. A. & Taylor, S. I. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4105-4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurten, R. C., Cadena, D. L. & Gill, G. N. (1996) Science 272, 1008-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haft, C. R., de la Luz Sierra, M., Barr, V. A., Haft, D. H. & Taylor, S. I. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 7278-7287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, Y., Zhou, Y., Szabo, K., Haft, C. R. & Trejo, J. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1965-1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarz, D. G., Griffin, C. T., Schneider, E. A., Yee, D. & Magnuson, T. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3588-3600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, J. J., Radice, G., Perkins, C. P. & Costantini, F. (1992) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 115, 277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radice, G., Lee, J. J. & Costantini, F. (1991) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 111, 801-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aaronson, S. A. & Todaro, G. J. (1968) J. Cell Physiol. 72, 141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohout, T. A., Lin, F. S., Perry, S. J., Conner, D. A. & Lefkowitz, R. J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1601-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gullapalli, A., Garrett, T. A., Paing, M. M., Griffin, C. T., Yang, Y. & Trejo, J. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2143-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beddington, R. S. & Robertson, E. J. (1998) Trends Genet. 14, 277-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bielinska, M., Narita, N. & Wilson, D. B. (1999) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 43, 183-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jollie, W. P. (1990) Teratology 41, 361-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson, E. J., Conlon, F. L., Barth, K. S., Costantini, F. & Lee, J. J. (1992) Ciba Found. Symp. 165, 237-250; discussion 250-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz, E. & Pfeffer, S. R. (1998) Cell 93, 433-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riederer, M. A., Soldati, T., Shapiro, A. D., Lin, J. & Pfeffer, S. R. (1994) J. Biol. 125, 573-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan, L., Molloy, S. S., Thomas, L., Liu, G., Xiang, Y., Rybak, S. L. & Thomas, G. (1998) Cell 94, 205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, Z. Q., Fung, M. R., Barlow, D. P. & Wagner, E. F. (1994) Nature 464-467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lau, M. M., Stewart, C. E., Liu, Z., Bhatt, H., Rotwein, P. & Stewart, C. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 2953-2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludwig, T., Eggenschwiler, J., Fisher, P., D'Ercole, A. J., Davenport, M. L. Efstratiadis, A. (1996) Dev. Biol. 177, 517-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.