Abstract

HumanIslets.com supports diabetes research by offering easy access to islet phenotyping data, analysis tools, and data download. It includes molecular omics, islet and cellular function assays, tissue processing metadata, and phenotypes from 547 donors. As it expands, the resource aims to improve human islet data quality, usability, and accessibility.

Comprehensive molecular and physiological phenotyping of human islets can enable deep mechanistic insights for diabetes research, but access to this critical tissue remains limited. Improving the quality, accessibility, usability, and integration of such datasets remains an important goal.1 We established the HumanIslets.com Consortium to advance these goals together with the Alberta Diabetes Institute (ADI) IsletCore (http://www.isletcore.ca/). We introduce HumanIslets.com, an open resource that presently includes data on 547 human islet donors. Users can access linked datasets describing molecular profiles, islet functions, and donor phenotypes and perform statistical, visual, and functional analyses at donor, islet, or single-cell levels, taking into consideration potential confounders. HumanIslets.com provides a growing and adaptable set of resources and tools to support the diabetes and islet research community.

A need for accessible, adaptable, and user-friendly human islet resources

The use of islets from cadaveric donors has become a staple of diabetes research following the development and refinement of methods for their large-scale isolation. Recent improvements in the transparency of human islet reporting in research are critical for reproducibility and rigor.2 Human islets are increasingly used as comparators for stem cell-derived products for transplantation, in genomics studies at both islet and single-cell levels, and in research on type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D).1 However, as islet datasets grow in size and complexity, it has become essential to understand how both reported and overlooked donor and technical variables influence experimental outcomes. Ensuring transparent documentation of experimental parameters and analysis pipelines is vital, and reporting should adhere to findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) principles.3 Given the limited availability of islet tissue and the substantial resources required to collect and analyze large datasets, maximizing their use is paramount.

The past decade has witnessed major efforts to generate large amounts and diverse types of data from human islets that can be leveraged for insights into diabetes pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. In addition to the availability of data in publications, public data repositories, or controlled access repositories, three main approaches have emerged to improve data usability: (1) portals that aggregate raw or minimally processed datasets and images such as the Human Pancreas Analysis Program (HPAP; https://hpap.pmacs.upenn.edu), Pancreatlas (https://pancreatlas.org), and the nPOD data portal (https://portal.jdrfnpod.org); (2) provision of islet quality control and donor demographic data, such as through the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) – Human Islet Phenotyping Program (https://iidp.coh.org); or (3) tools for data analysis and visualization, largely in the genomics space, such as the Pancreatic Islet Regulome Browser (http://www.isletregulome.org), the Translational Human Pancreatic Islet Genotype Tissue-Expression Resource (TIGER) Data Portal (https://tiger.bsc.es), Islet Gene View (https://mae.crc.med.lu.se/IsletGeneView/), and https://www.isletgenomics.org/. However, broad usability of many datasets remains a challenge—one that has been recognized by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via support for programs like HPAP4 and upcoming human islet knowledgebase efforts.

Limitations of current human islet data resources can include low numbers of donors, little or no donor or technical meta-data, limited accessibility to underlying datasets, a lack of linked datasets from the same donors, insufficient transparency in methodology or analysis, narrow breadth of data types, or conversely, broad and deep datasets that are minimally processed or integrated and require advanced expertise for analysis. The ADI IsletCore is a biobanking and distribution program5 and, with the HumanIslets.com Consortium, is positioned to integrate and improve access to a wide and growing scope of data across a broad range of donors. Using a design-thinking approach,6 we developed an open-access online resource with tools focused on addressing the needs of the research community through iterative consultation within the HumanIslets.com Consortium. This revealed a desire for simple queries and common analysis tasks of well-organized and documented data using established and widely understood statistical methods via an interactive web interface, coupled with the ability to easily subset and export minimally processed data for more customized and sophisticated offline analyses.

HumanIslets.com overview

We present HumanIslets.com, an online resource with data from 547 human research islet preparations (as of August 2024) from donors aged 10 weeks to 84 years, including those without diabetes and those who lived with pre-diabetes, T2D, or T1D. The metadata encompass details on donor and pancreas processing, islet isolation, cell culture outcomes, static and dynamic insulin secretion, oxygen consumption, and electrophysiological outcomes for a cells and b cells. This rich context including 74 donor variables, technical details, and physiological characteristics is combined with comprehensive molecular characterization including RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), NanoString mRNA panels, mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics, and single-cell transcriptomics (e.g., patch-seq) on islets from the same donors. With intuitive support for data and metadata analysis at donor, islet, and single-cell levels, HumanIslets.com enables analysis of genes, proteins, and pathways while controlling for common influencing factors and offers download of data, results, and analysis pipelines for transparent and reproducible re-analysis. The web tool is organized into four views, Omics View, Feature View, Donor View, and Data Download, which are described in detail in a visual walkthrough tutorial accessible via the homepage. A key design feature is to link these views via interactive plots, so researchers can seamlessly move between global, systems biology perspectives, population overviews, and focused summaries of individual genes to facilitate hypothesis generation and knowledge integration.

Our goal is to provide a flexible, open, and user-friendly platform for exploring the relationship between donor characteristics, isolation parameters, and islet phenotypes and molecular datasets from many donors. This will benefit the broader diabetes and islet research community via built-in analysis pipelines with standardized options and outputs and users who are more experienced in data processing and analysis by providing ease of access to minimally processed data in a variety of formats. We attempt to offer meaningful analysis for both new and experienced users within the computing restrictions of a web server. For instance, raw data processing and some advanced analyses will require offline computation, and while the current pipeline was designed for maximum comparability across omics types, there may be more optimal analyses for each dataset or analysis context. Where appropriate repositories exist else-where, raw data (i.e., proteomics MS, sequencing FASTQ files) are not stored in the HumanIslets.com tool but are accessible with links in the site documentation. The HumanIsletsR Github repository (https://github.com/xia-lab/HumanIsletsR) provides all R functions used to perform analyses within the tool and all R scripts used to process each dataset. Time stamps and versioning are used for downloads and software release for reporting and reproducibility to accommodate the growing datasets and analytical functions.

Understanding biological and technical associations

Substantial donor-to-donor variability in isolated islets is well recognized.7 This results from both donor heterogeneity and variation in pancreas procurement and organ processing. It is known that these factors may impact isolation and experimental outcomes. Despite increasing availability of this information (see the IIDP Research Data Repository, for example), many donor, technical, or organ-related variables remain under-reported and are rarely, if ever, accounted for during downstream data analysis. Some of the less commonly reported metadata available for analysis within HumanIslets.com include both quantitative measures (e.g., organ digestion time, islet particle index) and qualitative assessments (e.g., organ consistency, fatty infiltration).

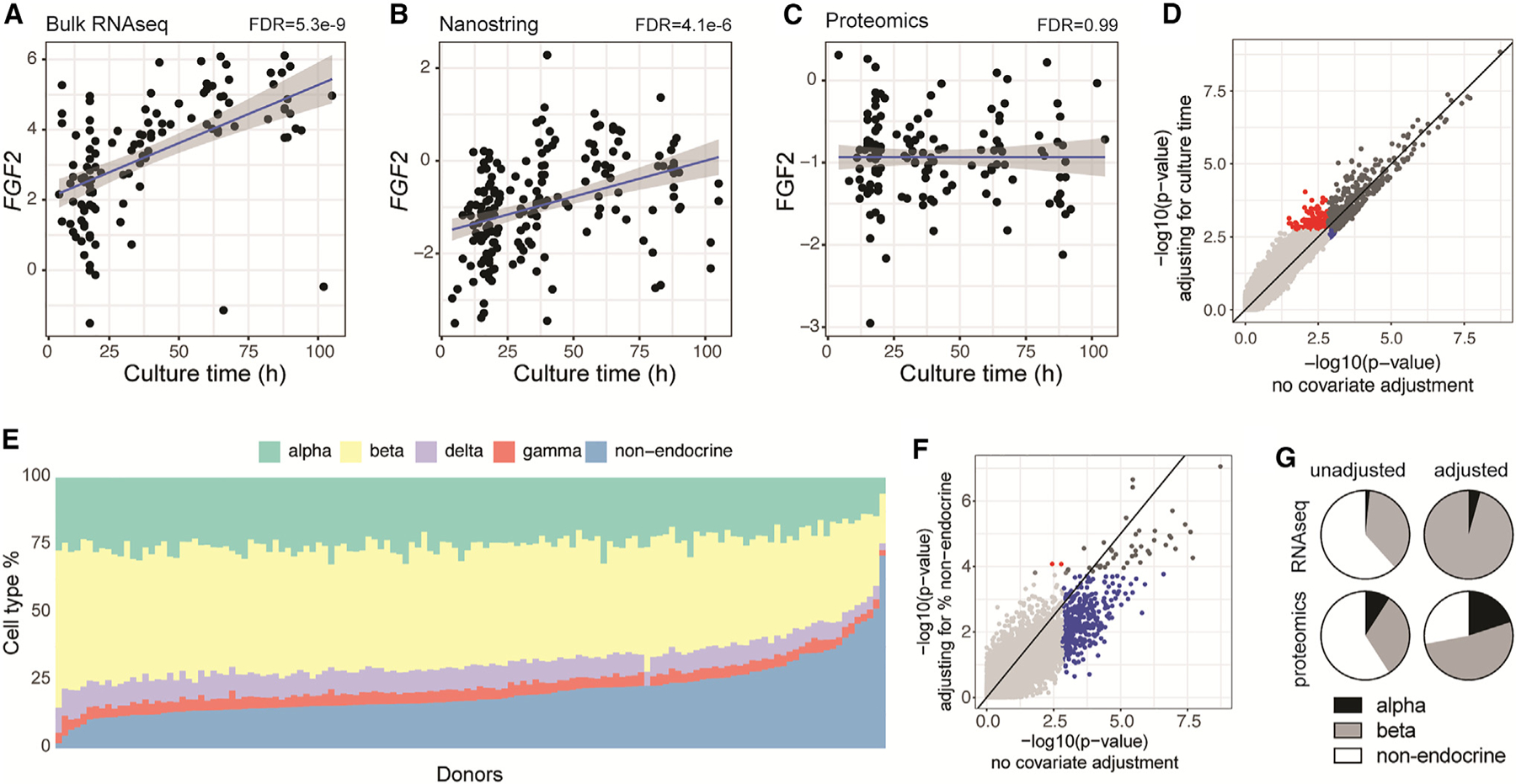

We find that ‘‘culture time’’ and ‘‘percent purity’’ should be carefully considered in the analysis and interpretation of data. Consistent with our recent observation,8 a large proportion of features associate with culture time in the bulk islet RNA-seq and NanoString data, but not islet bulk proteomics data (e.g., fibroblast growth factor 2 [FGF2]; Figures 1A–1C). This can be controlled for by including ‘‘culture time’’ (under ‘‘Cell Culture Outcomes’’) as a covariate when performing analysis on the Omics View page. Doing this improves the strength of the relationships between transcript expression and nearly every other variable and increases the number of transcripts associated with a diagnosis of T2D (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Corrections for culture time and non-endocrine cell proportions.

(A–C) Impact of culture time on expression of FGF2 measured by RNA-seq (A), NanoString (B), or proteomics (C).

(D) Impact of adjusting for culture time on gene-level p values for the association of bulk RNA-seq data and diabetes status (T2D vs. none). Transcripts were significant (FDR < 0.05) both with and without adjusting for culture time (dark gray), only when adjusting for culture time (red), only when not adjusting for culture time (blue), or not significant in either scenario (light gray).

(E) Cell-type distributions computed from proteomic data across donors, ranked by ‘‘non-endocrine’’ cell proportions.

(F) Impact of adjusting for the proportion of non-endocrine cells on protein-level p values for the association of bulk proteomics data and diabetes status (T2D vs. none). Proteins were significant (FDR < 0.05) both with and without adjusting for non-endocrine cells (dark gray), only when adjusting for non-endocrine cells (red), only when not adjusting for non-endocrine cells (blue), or not significant in either scenario (light gray).

(G) Adjusting for the proportion of non-endocrine cells increases the proportion of α and β cell-linked RNA-seq and proteomics features (adjusted p < 0.05) when comparing T2D versus no diabetes (non-adjusted RNA-seq, n = 117; adjusted RNA-seq, n = 90; non-adjusted proteomics, n = 134; adjusted proteomics, n = 134).

The association of preparation purity with many transcripts and proteins in the bulk omics data was initially surprising, since the islets were hand-picked to nearly 100% purity, and likely reflects non-endocrine cells that get trapped on islet surfaces. Indeed, bulk RNA-seq and proteomics features with the strongest positive and negative associations with purity have biased expression in endocrine and non-endocrine cell types, respectively. Since islet preparations from donors who lived with T2D are typically of lower purity, this may confound our ability to identify signals that are associated with impaired islet function. To address this, we implemented a deconvolution approach, detailed in the online web tool documentation, to estimate cell-type proportions based on proteomics data (Figure 1E) and included the ‘‘non-endocrine percentage’’ as a covariate during analysis. Although single-cell (sc)RNA-seq provides detailed gene expression profiles for individual cells, allowing a more precise analysis of cell-type-specific expression and heterogeneity, the scRNA-seq dataset used for visualizing cell-type-specific expression could not be used for cell-type estimates of our donors since it is a meta-analysis from various sources, not specifically matching ADI IsletCore donors. Although we have single-cell patch-seq data from these donors, the targeted collection process limits our ability to determine cell-type proportions or establish correspondence with bulk profile data. Finally, we found that marker gene-based deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq data was less reliable due to batch effects. In contrast, proteomics data, free from batch effects, provided ideal conditions for accurate analysis. This greatly reduces the number of bulk omics features identified as significantly different between donors who lived with T2D and those with no diabetes (Figure 1F) and successfully eliminated or greatly reduced significant features with non-endocrine biased expression by filtering out signals driven by differential amounts of trapped non-endocrine tissue in the T2D preparations (Figure 1G).

Our place in the human islet ecosystem: Now and the future

HumanIslets.com fills important gaps in the diabetes research landscape, complementing and significantly extending resources such as the HPAP-PancDB resource.4 PancDB facilitates the sharing of deep datasets (including imaging data) from donors who had T1D or T2D and matched controls with data from 171 donors currently. What we present here is larger and broader—focused on understanding population-level islet variation more generally (but also including diabetes). While PancDB is mostly aimed at dataset dissemination, our focus is on making data from ADI IsletCore preparations as usable and accessible as possible by the broadest spectrum of users, including extensive efforts to integrate usability and analysis tools. HumanIslets.com is tightly integrated with the ADI IsletCore biobanking program, which distributes research islets and other tissues, whereas HPAP is not connected to sample distribution. Our resource allows the comparison of data from external users with data available on the web tool and facilitates the searching of banked samples listed on the Donor View page and available in the ADI Islet-Core biobank.

While we include as much technical and donor metadata as possible, some important variables are not available. This may include information on self-reported gender or reproductive status, ethnicity, and exposure history, among potentially many others. Some of these gaps will be filled by our ongoing data collection effort, which presently includes plasma measurement of sex hormones, donor genotyping (including genetic ancestry and genetic risk scores for diabetes), prohormone processing, metabolomics, and the pancreatic accumulation of environmental contaminants and lipids. We expect these data will be added in an upcoming version of HumanIslets.com. It may also be possible to add additional datasets collected from archived islets and biopsies. We are eager for these samples to be leveraged for additional insights and welcome new contributors to join the HumanIslets.com Consortium. In time, we hope to allow all ADI IsletCore islet and tissue recipients to upload data for integration. Overall, the ongoing addition of donors and datasets to this resource will serve to greatly enhance the utility of HumanIslets.com in the coming years.

It is crucial to advance efforts and provide opportunities to promote access to and usability of datasets to accelerate research and maximize the substantial investments that underlie their collection. Data repositories play a critical role in data access,9 particularly considering initiatives such as the recently introduced NIH Data Management and Sharing Policy. Knowledge bases such as the T2D Knowledge Portal10 consolidate information to facilitate research and discovery. However, access to metadata can still be limiting, some non-standard data types are not easily deposited to current public databases (e.g., electrophysiology or insulin secretion data), and easy exploration of such phenotyping data remains a major limitation. We are committed through the HumanIslets.com Consortium and the ADI IsletCore to work collaboratively with the diabetes research community to improve data usability and establish standards in experimental protocols and reporting.

Conclusion

HumanIslets.com is a valuable resource for many scientists by enabling intuitive analysis and visual exploration of data and for computational biologists by providing straightforward downloading of minimally processed datasets. The resource will grow over time through the addition of new donors, new datasets, and new functions through user feedback as well as contributions from researchers with a shared interest in moving the human islet field forward in a collaborative and open manner.

CONSORTIA

The members of the HumanIslets.com Consortium are Ella Atlas, Austin Bautista, Jennifer E. Bruin, Alice L. Carr, Haoning H. Cen, Yi-chun Chen, Ma Enrica Angela Ching, Xiao-Qing Dai, Tina Dafoe, Theodore dos Santos, Cara E. Ellis, Jessica D. Ewald, Leonard J. Foster, Anna L. Gloyn, Aryana Hossein, Myriam P. Hoyeck, James D. Johnson, Jelena Kolic, Yao Lu, Francis Lynn, James G. Lyon, Patrick E. MacDonald, Jocelyn E. Manning Fox, Nadya M. Morrow, Erin E. Mulvihill, Andrew Pepper, Lindsay Pallo, Varsha Rajesh, Jason Rogalski, Shugo Sasaki, Seth A. Sharp, Nancy P. Smith, Aliya F. Spigelman, Han Sun, Swaraj Thaman, C. Bruce Verchere, Jane Velghe, Charles Viau, Kyle van Allen, Jessica Worton, Jordan Wong, Jianguo Xia, and Dahai Zhang.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The University of Alberta acknowledges that we are located on Treaty 6 territory and respects the histories, languages, and cultures of First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and all First Peoples of Canada, whose presence continues to enrich our vibrant community. We thank all families and donors for the generous gifts in support of diabetes and transplantation research and the Human Organ Procurement and Exchange (HOPE) program, Southern Alberta Organ and Tissue Donation Program (SAOTDP), Trillium Gift of Life Network (TGLN), BC Transplant, Quebec Transplant, and other Canadian organ procurement organizations for their efforts procuring pancreas for research. We appreciate the input of Viljem Pohorec (University of Maribor), Joan Camunas-Soler (Gothenberg), Jon Campbell (Duke University), and Jane Velghe (UBC). Data collection was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (186226 and 148451, P.E.M.; 168857, J.D.J.), Breakthrough T1D (2-SRA-2019-698-S-B, P.E.M.), the JDRF Center of Excellence at UBC (C.B.V., J.D.J., and F.C.L.), BCCHRI Child Health Integrative Partnership Strategy Funding (C.B.V., Dr. Megan Levings, and F.C.L.), the National Institutes of Health (U01-DK-120447, P.E.M.; U01-DK-123716, P.E.M. and A.L.G.; U01-DK105535, U01-DK085545, and UM-1DK126185, A.L.G.), and the Wellcome Trust (095101, 200837, 106130, and 203141, A.L.G.). Proteomics infrastructure and analysis were supported by the UBC Life Sciences Institute, Canada Foundation for Innovation, BC Knowledge Development Fund, and Genome Canada/BC (264PRO and 374PRO). Some data used in this web tool include patch-seq data and scRNA-seq used for cell-type expression analysis from the Human Pancreas Analysis Program (HPAP; RRID: SCR_016202) Database (https://hpap.pmacs.upenn.edu), a Human Islet Research Network (RRID: SCR_014393) consortium (UC4-DK-112217, U01-DK-123594, UC4-DK-112232, and U01-DK-123716). Consolidation of datasets and web tool development was supported by a research grant funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, JDRF Canada, and Diabetes Canada (5-SRA-2021-1149-S-B/TG 179092) to P.E.M. (Alberta), J.X. (McGill), J.D.J. (UBC), and J.E.B. (Carleton) with collaborators A.L.G. (Stanford), L.J.F. (UBC), E.A. (Ottawa), E.E.M. (Ottawa), F.C.L. (UBC), and C.B.V. (UBC).

Footnotes

Human research ethics approvals

Data collection and web tool development were performed with the approval of the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00013094; Pro00001754), the University of British Columbia (UBC) Clinical Research Ethics Board (H13-01865), the University of Oxford’s Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OxTREC ref. 2-15), the Oxfordshire Regional Ethics Committee B (REC ref. 09/H0605/2), or by the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics (IRB Protocol: 57310). All donors’ families gave informed consent for the use of pancreatic tissue in research.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

A.L.G.’s spouse is an employee of Genentech and holds stock options in Roche. A.R.P. serves on the Scientific Advisory Committee for Encellin Inc. J.X. is founder of XiaLab Analytics, which provides omics data science training and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gloyn AL, Ibberson M, Marchetti P, Powers AC, Rorsman P, Sander M, and Solimena M (2022). Every islet matters: improving the impact of human islet research. Nat. Metab 4, 970–977. 10.1038/s42255-022-00607-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart NJ, and Powers AC (2019). Use of human islets to understand islet biology and diabetes: progress, challenges and suggestions. Diabetologia 62, 212–222. 10.1007/s00125-018-4772-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, da Silva Santos LB, Bourne PE, et al. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018. 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapira SN, Naji A, Atkinson MA, Powers AC, and Kaestner KH (2022). Understanding islet dysfunction in type 2 diabetes through multidimensional pancreatic phenotyping: The Human Pancreas Analysis Program. Cell Metab 34, 1906–1913. 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyon J, Manning Fox JE, Spigelman AF, Kim R, Smith N, O’Gorman D, Kin T, Shapiro AMJ, Rajotte RV, and MacDonald PE (2016). Research-focused isolation of human islets from donors with and without diabetes at the Alberta Diabetes Institute IsletCore. Endocrinology 157, 560–569. 10.1210/en.2015-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soufan O, Ewald J, Zhou G, Hacariz O, Boulanger E, Alcaraz AJ, Hickey G, Maguire S, Pain G, Hogan N, et al. (2022). EcoToxXplorer: Leveraging design thinking to develop a standardized web-based transcriptomics analytics platform for diverse users. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 41, 21–29. 10.1002/etc.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kayton NS, Poffenberger G, Henske J, Dai C, Thompson C, Aramandla R, Shostak A, Nicholson W, Brissova M, Bush WS, and Powers AC (2015). Human islet preparations distributed for research exhibit a variety of insulin-secretory profiles. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 308, E592–E602. 10.1152/ajpendo.00437.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolic J, Sun WG, Cen HH, Ewald JD, Rogalski JC, Sasaki S, Sun H, Rajesh V, Xia YH, Moravcova R, et al. (2024). Proteomic predictors of individualized nutrient-specific insulin secretion in health and disease. Cell Metab 36, 1619–1633.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin D, McAuliffe M, Pruitt KD, Gururaj A, Melchior C, Schmitt C, and Wright SN (2024). Biomedical data repository concepts and management principles. Sci. Data 11, 622. 10.1038/s41597-024-03449-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costanzo MC, von Grotthuss M, Massung J, Jang D, Caulkins L, Koesterer R, Gilbert C, Welch RP, Kudtarkar P, Hoang Q, et al. (2023). The Type 2 Diabetes Knowledge Portal: An open access genetic resource dedicated to type 2 diabetes and related traits. Cell Metab 35, 695–710.e6. 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]