Abstract

Central neuropeptides are small proteins or peptides primarily produced and released by neurons. They act as neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and neuroregulators within the central nervous system (CNS). Numerous studies have demonstrated that these neuropeptides play a role in both normal neurophysiological processes and pathological conditions. Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the CNS, are crucial for maintaining brain function and health, and they contribute significantly to the development of CNS disorders—especially neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases. Previous research suggests that central neuropeptides influence astrocyte activity by regulating their proliferation, morphology, and secretory functions, among other aspects, thereby impacting the pathogenesis of these disorders. Based on preclinical evidence, both central neuropeptides and their receptors are emerging as promising targets for treating CNS disorders. In this review, we examine the effects of select central neuropeptides—including neuropeptide Y (NPY), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), cholecystokinin (CCK), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), angiotensin (Ang), oxytocin (OXT), orexin (OX)/hypocretin (HCRT), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)—on astrocyte state transitions. Our aim is to provide novel insights that could inform the clinical treatment of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Neuropeptide, Central nervous system, Astrocyte, Neurodegenerative disorders, Neuropsychiatric disorders

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) disorders—including neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions—are the leading cause of disability and the second leading cause of death worldwide. These disorders are mainly classified into three groups: neurodegenerative, neuropsychiatric, and cerebrovascular disorders. As the global population grows and ages, the social and economic burdens of CNS disorders continue to increase (Wang et al. 2022). Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and multiple sclerosis (MS), are marked by the progressive loss of synapses and neurons (Gupta et al. 2023). Neuropsychiatric disorders—ranging from depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder to autism spectrum disorders, headaches, and epilepsy—bridge the fields of neurology and psychiatry (Saleki et al. 2024). Together, these conditions pose major public health challenges, significantly impacting population health and socioeconomic development.

Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the CNS, are increasingly recognized for their active role in the onset and progression of CNS disorders (Sofroniew 2020). Since the concept of neuropeptides emerged last century, many have been identified, and their functions in the CNS have become a major focus in neuroscience research. Central neuropeptides have been shown to influence astrocyte proliferation, morphology, and secretory activity, thereby modulating their functional state (Chen et al. 2022; Krisch and Mentlein 1994; Masmoudi-Kouki et al. 2018). These interactions are particularly relevant in the context of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Understanding how central neuropeptides regulate astrocyte states may offer new insights into the mechanisms of these disorders and help identify potential therapeutic targets.

Central neuropeptides

Central neuropeptides are small proteins or peptides primarily synthesized and released by neurons, functioning mainly within the CNS (Bakos et al. 2016). By binding to specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), they modulate neuronal activity and contribute to a variety of physiological processes, including emotion regulation, pain perception, appetite control, sleep, learning, and memory (Beck and Pourié 2013; Neugebauer et al. 2020). These neuropeptides are produced through the cleavage of precursor molecules and stored in large dense-core vesicles at the presynaptic membrane before being transported to nerve terminals via axonal transport (Satao and Doshi 2024). Compared to classical neurotransmitters, central neuropeptides exhibit receptor affinities and selectivities roughly 1,000 times greater, allowing them to trigger biological effects at much lower concentrations (Merighi et al. 2011).

To date, over one hundred central neuropeptides have been identified and studied. However, there is no universally accepted classification system. Generally, two main approaches are used. Family-based classification: Groups include the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)/pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/glucagon (GCG) superfamily, the endogenous opioid peptide family, the vasopressin (VP)/oxytocin (OXT) family, the gastrin/cholecystokinin (CCK) family, and the neuropeptide Y (NPY)/peptide YY family. Discovery site classification: Neuropeptides are categorized by their sites of origin, such as pituitary-like peptides (e.g., VP, OXT, growth hormone), brain-gut peptides (e.g., substance P, enkephalins, VIP), and hypothalamic-releasing hormones (e.g., corticotropin-releasing hormone [CRH] and thyrotropin-releasing hormone) (Casello et al. 2022; Rana et al. 2022).

Astrocytes in CNS

Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cells in the CNS, accounting for 20–40% of all brain cells, and are essential for maintaining brain function and overall health. They protect the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), secrete neurotrophic factors to promote synaptogenesis, regulate neuronal differentiation, and support neuronal survival (Zhou et al. 2019). The morphological characteristics of astrocytes—such as cell size, process length and complexity, and polarization—are critical for normal CNS function and are tightly regulated by signals from neurons and other glial cells (Chai et al. 2017; Endo et al. 2022). This dynamic regulation underlies the adaptability of astrocytes and directly impacts their functional capacity.

Historically, researchers discovered that astrocyte morphology adapts dynamically in response to environmental changes, enabling these cells to cope with both physiological and pathological conditions (Pekny et al. 2016). Under normal conditions, astrocytes remain in a resting state with limited proliferation while secreting nutrients like lactate and cholesterol to support neuronal metabolism. In contrast, pathological changes in the CNS trigger astrocyte hypertrophy, excessive proliferation, and the release of various cytokines—a process known as reactive astrogliosis (Fig. 1). This reactive response significantly influences disease outcomes (Escartin et al. 2021; Ye et al. 2018). Although the consequences of reactive astrogliosis vary, an increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression is widely used as a marker of activated astrocytes (Linnerbauer et al. 2020). Other common markers include S100 calcium-binding protein β (S100β), complement component 3 (C3), cluster of differentiation receptor 109 (CD109), and connexin 30 (Cx30) (Jurga et al. 2021). Moreover, activated astrocytes can polarize into two distinct phenotypes, known as A1 and A2 astrocytes.

Fig. 1.

Central neuropeptides regulate astrocyte state transitions in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. The pathogenesis of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders is multifaceted, involving factors such as abnormal microglial activation, neurotransmitter dysregulation, neurodegeneration, demyelination, plaque aggregation and fibrillary tangles, vascular pathology, and chronic stress. These factors ultimately alter astrocyte morphology, leading to a cascade of pathological changes. Central neuropeptides are small proteins or peptides primarily synthesized and secreted by neurons within the CNS. By binding to specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), they modulate neuronal activity and participate in a wide range of physiological processes. Numerous studies have demonstrated that several central neuropeptides—including neuropeptide Y (NPY), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), cholecystokinin (CCK), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), angiotensin (Ang), oxytocin (OXT), orexin (OX)/hypocretin (HCRT), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)—influence the onset and progression of these disorders by regulating the state transitions of astrocytes. [Created with BioRender.com]

In neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, A1 astrocytes are typically considered detrimental; they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic factors such as C3, D-serine, nitric oxide (NO), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), thereby exacerbating disease progression (Clarke et al. 2018). In contrast, A2 astrocytes secrete neurotrophic factors—including cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1 (CLCF1), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-10 (IL-10)—that promote neuronal survival and recovery (Fan and Huo 2021). Numerous studies have indicated that, in the context of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, astrocytes are widely activated and tend to adopt the A1 phenotype (Zhai et al. 2024). Consequently, strategies aimed at suppressing abnormal astrocyte activation and controlling their polarization represent promising therapeutic targets.

Recent research highlights the critical interplay between central neuropeptides and astrocytes in maintaining CNS homeostasis (Nakamachi et al. 2011; Schwartz and Taniwaki 1994). Among these neuropeptides, NPY, VIP, PACAP, CCK, CRH, angiotensin (Ang), OXT, orexin (OX)/hypocretin (HCRT), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) have emerged as particularly promising drug candidates for treating neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Understanding how central neuropeptides regulate astrocyte morphology and function not only deepens our knowledge of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying these disorders but also opens the door to novel therapeutic strategies.

This review summarizes the latest research on the regulation of astrocyte states by central neuropeptides in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Specifically, it focuses on: (1) The fundamental roles of central neuropeptides; (2) Their effects on astrocyte proliferation, morphology, and secretory functions under both physiological and pathological conditions (Figs. 1 and 2); and (3) Their potential as therapeutic targets. Through a comprehensive analysis, this review aims to illuminate the synergistic roles of central neuropeptides and astrocyte states in brain function and to offer new perspectives for the diagnosis and treatment of related disorders.

Fig. 2.

Diverse effects of central neuropeptides on astrocytes via specific GPCRs. Astrocytes express a wide array of neuropeptide receptors, enabling central neuropeptides to finely regulate their function. For example, NPY, acting through Y1R, inhibits the release of iNOS and NO and reduces ROS production, while also stimulating its own secretion via mGluR activation. VIP and PACAP, through PAC1 receptors, promote the synthesis and release of NT-3, glutathione (GSH), ADNP, ADNF, and MIP, thereby providing neuroprotection; additionally, PACAP enhances ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a cAMP-dependent manner, leading to astrocyte proliferation and activation of GFAP gene expression. In contrast, Ang II, via AT1R, induces the release of inflammatory factors, suppresses GSH production, increases ROS generation, and triggers ferroptosis, while also promoting astrocyte growth through the activation of Src, Pyk2, and ERK1/2, and contributing to neuropsychiatric disorders via the β-arrestin2 pathway. ACE2 converts Ang II into Ang (1–7), which activates MasR to exert neuroprotective effects by downregulating p38MAPK-mediated inflammation, reducing inflammatory factor levels, and modulating astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammation through the lncRNA SNHG14/miR-223-3p/NLRP3 pathway. Moreover, orexin, acting through OXR, increases cAMP production and ERK1/2 phosphorylation while inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK pathways, thereby reducing astrocyte activation and apoptosis and alleviating neuroinflammation. GLP-1, via GLP-1R, suppresses the secretion of MMP, MCP-1, and CXCL-1, and lowers VEGF-A levels by inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 signaling to maintain BBB integrity. CCK, through CCKBR and mGluR5, elevates intracellular Ca²⁺ and ATP release, which regulates synaptic plasticity. OXT, via OXTR, inhibits the release of the NLRP3 inflammasome, thus modulating neuroinflammation, while CRH, acting through CRHR1, suppresses CXCL5 secretion by astrocytes, inhibiting synapse formation in hippocampal neurons. Finally, UCN2 promotes hippocampal synapse formation by inducing astrocytes to secrete NGF. [Created with BioRender.com]

Central neuropeptides and astrocyte proliferation

NPY and astrocyte proliferation

NPY is a 36–amino acid peptide widely expressed throughout the mammalian nervous system. It is particularly concentrated in brain regions involved in emotion and cognition, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and striatum (Duarte-Neves et al. 2016). Although NPY is primarily synthesized and released by GABAergic interneurons, it is also found in astrocytes and certain projection neurons. Moreover, NPY can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and enter the CNS from peripheral sources (Gøtzsche and Woldbye 2016).

To date, seven NPY receptors (Y1R, Y2R, Y4R, Y5R, Y6R, Y7R, and Y8R) have been identified in vertebrates, with five (Y1R, Y2R, Y4R, Y5R, and Y6R) present in mammals (Sundström et al. 2013). NPY plays essential roles in various physiological processes, including circadian rhythm regulation, neurogenesis, neuronal excitability and plasticity, appetite control, energy homeostasis, memory, learning, and emotional modulation (Geloso et al. 2015). Altered NPY levels have been observed in several neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. For instance, NPY expression is markedly reduced in the hippocampus of patients with AD (Kowall and Beal 1988), and similar reductions have been noted in AD mouse models in both the hippocampus and cortex (Ramos et al. 2006). Additionally, intracerebroventricular injection of NPY has been shown to reverse depressive-like behaviors and spatial memory impairments in AD mice via Y2R activation (dos Santos et al. 2013). In PD animal models, the loss of dopaminergic neurons corresponds with an increase in NPY neurons in the striatum, potentially serving as an early protective mechanism (Ma et al. 2014). Direct injection of NPY into the striatum has also been observed to prevent degeneration in the nigrostriatal pathway through Y2R-mediated mechanisms (Decressac et al. 2012).

Recent findings indicate that astrocytes themselves can synthesize NPY. Upon activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors, astrocytes release NPY via Ca²⁺-dependent exocytosis of dense-core granules (Ramamoorthy and Whim 2008). Studies have shown that knocking out the NPY receptor reduces the number of proliferating cells, migrating neuroblasts, and intermediate neurons in the olfactory bulb of mice, highlighting NPY’s crucial role in regulating adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone (SVZ) (Stanic et al. 2008). Moreover, a significant increase in bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)/GFAP double-labeled cells after lateral ventricle injection of NPY suggests that NPY enhances astrocyte proliferation in the SVZ through Y1R activation (Decressac et al. 2009).

VIP and PACAP and astrocyte proliferation

VIP is a 28–amino acid neuropeptide within the VIP/PACAP/GCG superfamily. It primarily acts through VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors and is also partially recognized by the PACAP-specific PAC1 receptor. PACAP shares 68% structural similarity with VIP and exhibits comparable neurotrophic effects (Zusev and Gozes 2004). Both VIP and PACAP play roles in the development and progression of various neurological disorders and offer neuroprotection against toxic insults such as ethanol, hydrogen peroxide, β-amyloid, and inflammatory cytokines. For example, in AD, overexpression of VIP enhances the phagocytosis of fibrillar β-amyloid by hippocampal microglia, thereby reducing amyloid deposition in the brain (Song et al. 2012). In PD, VIP treatment alleviates oxidative stress–induced neuronal damage by reducing lipid peroxidation and DNA fragmentation in the striatum, protecting neurons from apoptosis in a 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)–induced rat model (Tunçel et al. 2012). In HD, decreased expression of VIP and its VPAC2 receptor in the suprachiasmatic nucleus is linked to disrupted circadian rhythms (Fahrenkrug et al. 2007).

The effects of VIP and PACAP on astrocytes have been documented for decades. Early studies revealed that these neuropeptides are involved in astrocyte proliferation. For instance, when VIP and PACAP antagonists were administered to pregnant mice on embryonic days 17 and 18, a dramatic reduction in astrocytes was observed in the offspring’s upper cortical layers—an effect that could be reversed by VIP, PACAP, or VPAC2 agonists (Zupan et al. 1998). Further studies indicate that PACAP can stimulate astrocyte proliferation even at low concentrations, a process closely associated with MAPK activation. Picomolar concentrations of PACAP trigger the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 via a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)–dependent mechanism, which in turn stimulates intracellular cAMP production in developing cortical progenitor cells, leading to astrocyte generation and activation of GFAP gene expression (Moroo et al. 1998). Additionally, PACAP-induced cAMP production results in intracellular Ca²⁺ mobilization or increased extracellular Ca²⁺ influx, which then activates the downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator (DREAM) to stimulate GFAP gene transcription (Cebolla et al. 2008). The proliferative effect of PACAP can be reversed by cAMP antagonists or ERK inhibitors (Masmoudi-Kouki et al. 2007). Under pathological conditions, VIP and PACAP also play significant roles in regulating astrocyte proliferation. For example, in a 6-OHDA–induced PD rat model, the density of striatal astrocytes increased markedly, and VIP treatment reduced GFAP levels, thereby partially alleviating astrogliosis, and reversed motor dysfunction in PD rat models (Yelkenli et al. 2016). These findings suggest that the proliferative effects of VIP and PACAP on astrocytes are complex and not yet fully understood, warranting further investigation.

CRH and astrocyte proliferation

CRH is a 41–amino acid neuropeptide that belongs to the CRH peptide family, which also includes urocortin 1 (UCN1), urocortin 2 (UCN2), and urocortin 3 (UCN3). All these peptides exert their effects by binding to the CRH receptor (CRHR) (Matsoukas et al. 2024). The CRHR family comprises two subtypes, CRHR1 and CRHR2. CRH preferentially binds to CRHR1, while UCN1 can interact with both receptors. In contrast, UCN2 and UCN3 selectively bind to CRHR2, serving as the endogenous ligands for this receptor (Vuppaladhadiam et al. 2020).

CRH is mainly secreted by the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and plays a critical role in regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, especially in response to stress and emotional changes (Vale et al. 1983). Urocortins, however, are more widely distributed. In addition to their role in the HPA axis, they participate in feeding behavior, cardiovascular regulation, and other physiological processes (Monteiro-Pinto et al. 2019). Overexpression of CRH and CRHR1 has been closely linked to mental disorders such as anxiety and depression (Lv et al. 2024), while activation of the CRHR2 signaling pathway contributes to anxiolysis, stress recovery, and the maintenance of homeostasis (Wang et al. 2023a). CRH is involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases. Studies have shown that serum CRH levels are elevated in post-stroke depression (PSD) patients compared to healthy persons. This strongly suggests that the elevation of CRH levels is a key pathological factor in the occurrence of PSD. Moreover, In PSD rats, CRH activates the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway via CRHR1 in the prefrontal cortex, leading to increased p62 expression. Blocking CRHR1 enhances synaptic plasticity and alleviates depressive-like behaviors and cognitive impairments in these animals (Liu et al. 2024a). Similarly, in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) models, selective activation of CRHR2 in the paraventricular nucleus alleviates anxiety-like behaviors and slows disease progression (Tillinger et al. 2024).

CRH and urocortins also directly interact with astrocytes, modulating their inflammatory responses and neuroprotective functions (Deng et al. 2024a; Zheng et al. 2016). These interactions may help explain mechanisms underlying neuroinflammation and neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, CRH promotes astrocyte proliferation in a dose-dependent manner, as demonstrated by BrdU incorporation experiments. This mitogenic effect is more pronounced in immature astrocytes than in mature ones and can be inhibited by competitive CRHR antagonists (Ha et al. 2000). However, the precise mechanisms by which CRH affects astrocyte proliferation remain unclear and warrant further investigation.

Under cerebral ischemic conditions, increased expression of CRHR1 in the mouse hippocampus leads to significant proliferation of reactive astrocytes. Treatment with antalarmin, a CRHR1 blocker, notably reduces GFAP levels in the hippocampus, underscoring the role of CRHR1 in astrocyte reactivity (de la Tremblaye et al. 2017).

Ang and astrocyte proliferation

Ang represents a class of central neuropeptides derived from angiotensinogen (AGT). In the CNS, astrocytes synthesize both renin and AGT, and AGT is enzymatically processed by renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a crucial role in regulating blood pressure, fluid balance, and various organ functions. Within the RAS, ACE converts inactive angiotensin I (Ang I) into highly bioactive angiotensin II (Ang II) (Wright et al. 2013). Ang II exerts its effects by binding to specific receptors, including the AT1 receptor (AT1R) and AT2 receptor (AT2R) (Paz Ocaranza et al. 2020). Notably, Ang II-AT1R signaling mediates pro-inflammatory and pathological processes—such as neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and neurotoxicity—that contribute to tissue damage and functional impairments (Forrester et al. 2018). Conversely, when Ang II activates AT2R, it inhibits oxidative stress and inflammation, promotes cell survival, and enhances cognitive function (Bhat et al. 2021). This dual regulatory mechanism underscores the central role of the RAS in maintaining physiological and pathological balance.

The brain RAS is also involved in regulating cardiovascular functions such as blood pressure, cardiac output, and vascular tone (Volpe et al. 2002). Moreover, it plays a vital role in the development of various neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, including traumatic brain injury (TBI), MS, AD, PD, and stroke (Abiodun and Ola 2020). In neurodegenerative disorders like AD, PD, and MS, astrocytes often exhibit excessive activation and a pro-inflammatory phenotype. In contrast, astrocytes appear to perform distinct functions in TBI (Wang et al. 2021). Research has shown that neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) increases following TBI, although this occurs at the expense of astrocyte formation (Bielefeld et al. 2024). However, the specific mechanisms by which astrocytes contribute to these processes remain unclear.

Astrocytes are integral components of the brain RAS, and both Ang II and Ang III significantly influence their activity. Studies have demonstrated that Ang II and Ang III promote astrocyte proliferation. For example, Ang II stimulates astrocyte growth by activating non-receptor tyrosine kinases Src and Pyk2, which in turn activate ERK1/2 (Clark and Gonzalez 2007). Additionally, both Ang II and Ang III induce phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, leading to the proliferation of cultured rat astrocytes. Pre-treatment of brainstem astrocytes with the JNK inhibitor SP600125 significantly reduced the phosphorylation of JNK and the subsequent astrocyte proliferation induced by Ang II and Ang III (Clark et al. 2008, 2012).

OXT and astrocyte proliferation

OXT is a neuropeptide composed of nine amino acids and is primarily synthesized by hypothalamic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), supraoptic nucleus (SON), and other accessory nuclei. It is released into both the bloodstream and the brain (Iovino et al. 2021). OXT plays a crucial role in childbirth and lactation; during labor, it stimulates uterine smooth muscle contractions to facilitate delivery, and during lactation, it triggers mammary smooth muscle contractions to eject milk. Often referred to as the “love hormone,” OXT significantly influences bonding, social behavior, and mother–infant interactions (Marsh et al. 2021; Zik and Roberts 2015).

Beyond its role in social behaviors, OXT has emerged as an important factor in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders such as AD, anxiety disorders, and depression (Ghazy et al. 2023). For example, in APP/PS1 transgenic mouse models of AD, OXT reduces hippocampal glial activation and restores both social and non-social memory, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target for alleviating central inflammation and cognitive impairments in AD (Selles et al. 2023). Additionally, studies have shown that OXT can reverse the reduction of OXT receptor (OXTR) expression and glutathione levels in the striatum of HD rats, while also modulating anxiety and depression symptoms (Khodagholi et al. 2022).

In the brain, OXT interacts with both neurons and astrocytes. As early as 1992, OXTR were identified on astrocytes (Di Scala-Guenot and Strosser 1992). OXT promotes astrocyte proliferation, and evidence indicates that intracellular calcium plays a crucial role in this process. In vitro studies have shown that OXT induces intracellular Ca²⁺ oscillations in astrocytes, confirming that these cells directly respond to OXT signaling (Scala-Guenot et al. 1994). Recent research further revealed that optogenetically controlled release of OXT at axon terminals in the central amygdala (CeA) triggers local calcium transients in astrocytes via OXTR activation (Wahis et al. 2021). Although intracellular Ca²⁺ signaling is critical for astrocyte proliferation, direct evidence linking OXT-induced Ca²⁺ increases to astrocyte proliferation remains limited, similar to findings with PACAP. Nonetheless, studies have demonstrated that OXT administration significantly increases the expression of the GFAP gene and protein in the hippocampus of adult rats (Havránek et al. 2017). Moreover, OXT promotes astrocyte proliferation through ERK1/2 phosphorylation and protects astrocytes from oxidative stress, underscoring the importance of OXT and OXTR in maintaining astrocyte growth and vitality (Alanazi et al. 2020).

Central neuropeptides and astrocyte morphology

CCK and astrocyte morphology

CCK is a 33–amino acid neuropeptide highly expressed in both the peripheral nervous system and the CNS of mammals. In addition to its roles in digestive function and glucose metabolism, CCK is crucial for regulating neurotransmitter release and memory formation (Asim et al. 2024). Its effects are primarily mediated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which vary in distribution and function between the peripheral and central systems. In the periphery, CCK mainly interacts with the cholecystokinin A receptor (CCKAR) to facilitate digestion and nutrient absorption (Chen et al. 2004). In the CNS, the predominant active forms are CCK-8 sulfate (CCK-8 S) and CCK-8, which interact with the cholecystokinin B receptor (CCKBR) via autocrine, endocrine, and paracrine mechanisms. This interaction influences neurotransmitter release, emotional responses, pain perception, and memory processes (Agersnap et al. 2016; Lau et al. 2023; Meyer 2014). High levels of CCK are found in brain regions involved in feeding behavior, emotional regulation, and cognitive functions—such as the hypothalamus, hippocampus, cortex, striatum, and spinal cord (Rehfeld 2017) — with CNS concentrations of CCK being significantly higher than those of other central neuropeptides (Rehfeld 2021). Changes in brain CCK levels are essential for maintaining normal physiology and have been implicated in the pathophysiology of several neurodegenerative disorders. For instance, injecting a CCKBR antagonist into the motor cortex impairs motor learning in mice (Li et al. 2024), while activation of CCKBR ameliorates cognitive deficits. CCKBR agonists mitigate memory impairments in CCK-deficient and aged AD mice (Zhang et al. 2024), and CCK analogs improve learning and memory in AD mice by modulating hippocampal neuronal mitochondrial dynamics (Hao et al. 2024). Moreover, CCK is important for emotional regulation, influencing conditions such as panic attacks, PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Chronic stress activates CCKBR in the basolateral amygdala (BLA), whereas blocking CCKBR impairs long-term potentiation (LTP) formation while producing antidepressant-like effects (Zhang et al. 2023).

Astrocytes also express CCK receptors, which are involved in various physiological and pathological processes. Under normal conditions, CCK induces intracellular Ca²⁺ oscillations in cultured astrocytes, indicating that these cells are key targets of hippocampal CCK signaling (Müller et al. 1997). Activation of CCKBR and group 5 metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR5) in astrocytes increases intracellular calcium levels and triggers ATP release, thereby modulating GABAergic synaptic plasticity in the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in rats (Crosby et al. 2018). Calcium signaling is closely linked to astrocyte morphological changes and activation; as a vital intracellular second messenger, Ca²⁺ regulates various astrocytic activities. Since astrocytes are non-excitable cells, their activity largely depends on intracellular calcium elevation (Novakovic et al. 2023). For example, treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulates the expression and activity of L-type voltage-operated calcium channels (VOCCs) in primary cortical astrocytes. LPS also increases the number of reactive astrocytes, the proportion of proliferating cells, and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Blocking L-type VOCCs effectively inhibits the increase in cells positive for GFAP, S100β, vimentin, and nestin (Cheli et al. 2016).

Under pathological conditions, CCK influences astrocyte states and contributes to neurological disorders. Reduced CCK levels in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus lead to activation of A1 astrocytes, decreased proliferation of radial glia-like neural stem cells, reduced adult hippocampal neurogenesis, and upregulation of neuroinflammatory proteins. Chemogenetic activation of CCK-expressing interneurons can reverse these changes via astrocyte-mediated glutamatergic signaling cascades (Asrican et al. 2020). Similarly, exogenous CCK-8 supplementation suppresses A1 astrocyte activation and increases glutamatergic synaptic density in the hippocampus, effectively alleviating spatial learning and memory deficits in aged mice with delayed neurocognitive recovery (Chen et al. 2021). Additionally, CCK analogs reduce the coverage area of GFAP-positive astrocytes in the substantia nigra pars compacta of PD mouse models, decrease inflammatory cytokine levels, reverse dopamine neuronal and synaptic loss, and ultimately alleviate MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine)-induced impairments in motor and exploratory activity in mice (Zhang et al. 2022c).

OX/HCRT and astrocyte morphology

Orexin (OX), also known as hypocretin (HCRT), is a neuropeptide secreted by neurons in the lateral hypothalamus. There are two forms: orexin A (OXA, or hypocretin-1), composed of 33 amino acids, and orexin B (OXB, or hypocretin-2), composed of 28 amino acids (Sun et al. 2021b). Orexin acts through two G protein-coupled receptors, OX1R and OX2R, to regulate various central and peripheral functions. While OXA binds both receptors with similar affinities, OXB preferentially activates OX2R (Li et al. 2020). In the CNS, orexins are essential for regulating wakefulness, sleep, appetite, energy metabolism (Toor et al. 2021), and emotion and reward systems (Katzman and Katzman 2022). Peripherally, they modulate cardiovascular function (Jiao et al. 2024) and gastrointestinal activity via the autonomic and endocrine systems(Okumura and Takakusaki 2008). Because orexins are vital for maintaining wakefulness, their dysregulation is linked to neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, making them important research targets (Berhe et al. 2020; Fronczek et al. 2021).

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of OXA are significantly increased in AD patients (Liguori et al. 2014). Interestingly, one study found a positive correlation between CSF OXA levels and cognitive function in AD patients (Shimizu et al. 2020). However, in animal models, OXA appears to worsen spatial learning and memory deficits in AD mice, underscoring the complexity of the orexin system’s role in AD (Li et al. 2023). In PD, orexins exhibit neuroprotective effects on dopaminergic neurons; for instance, OXA significantly improves motor, sensorimotor, and muscle tone impairments in 6-OHDA-induced rats (Hadadianpour et al. 2017). Orexins are also implicated in psychiatric disorders: acute restraint stress activates hypothalamic OX neurons and raises OXA levels in the ventral tegmental area, potentially triggering relapse in addiction (Tung et al. 2016), and elevated CSF OX levels are found in patients with panic-related anxiety (Johnson et al. 2010).

Orexins also regulate diverse functions in astrocytes. Activation of OX1R stimulates cAMP synthesis in primary rodent astrocytes (Woldan-Tambor et al. 2011). Like Ca²⁺, cAMP is a key second messenger that initiates various downstream cellular processes. Elevated cAMP levels have been shown to transform flat, polygonal astrocytes into process-bearing, stellate cells (Won and Oh 2000). Furthermore, cAMP treatment reduces the number of GFAP-positive astrocytes by nearly 25% compared to controls, accompanied by a broad downregulation of genes involved in astroglial activation—such as those regulating hyperplasia, cytoskeletal rearrangement, immune responses, and scar formation (Paco et al. 2016).

In pathological conditions, orexin-mediated regulation of astrocytes plays a crucial role in disease progression. In sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE), compared to the sham group, the expression levels of OX1R and OX2R in the hippocampus are elevated in SAE mice (Guo et al. 2024b). Additionally, OXA, via OX2R rather than OX1R, reduces oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in the hippocampus, suppresses ERK/nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)–driven activation of microglia and astrocytes, reverses morphological changes such as enlarged cell bodies and shortened processes, and promotes the conversion of neurotoxic A1 reactive astrocytes to the neuroprotective A2 phenotype, ultimately enhancing cognitive function (Guo et al. 2024a, b). In ischemia-reperfusion injury, OXA mitigates excessive autophagy through the OX1R-mediated MAPK/ERK/mTOR pathway (Xu et al. 2021b) and reduces cortical astrocyte activation and apoptosis by suppressing OX1R-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling, thereby lowering GFAP expression and neuroinflammation (Xu et al. 2021a). In MS mouse models, OXA diminishes astrocyte activation and central demyelination (Becquet et al. 2019). The multifaceted roles of the orexin system in the nervous system make it a promising target for treating neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, and future research will further clarify its complex mechanisms and clinical applications.

GLP-1 and astrocyte morphology

GLP-1 is a neuropeptide composed of 30 amino acids, derived from the cleavage of the proglucagon molecule. It is primarily secreted by intestinal L cells in the periphery and by neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the CNS (Holst 2007; Secher et al. 2014). Neuronal projections from the NTS extend to multiple brain regions, including other brainstem areas as well as forebrain and midbrain limbic regions (Diz-Chaves et al. 2022).

GLP-1 plays a vital role in various physiological systems. Its glucose-lowering and anti-inflammatory effects have garnered significant attention in recent years. In the CNS, GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) signaling is essential for mediating the anorexigenic effects of GLP-1 analogs. When physiological doses of GLP-1 are administered intravenously during meals, subjects experience increased satiety and reduced food intake (Flint et al. 1998). Disruption of vagal afferent signaling hinders these anorexic effects, highlighting the importance of the vagus nerve in GLP-1-mediated satiety (Plamboeck et al. 2013). Additionally, GLP-1 and its receptors have been implicated in neurodegenerative disorders. Studies have shown that in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and PD, the expression level of GLP-1R in the CNS is significantly downregulated(Sun et al. 2021a; Wang et al. 2023b). In AD models,, the GLP-1R agonist liraglutide reduces activated microglia and cortical inflammation, alleviating AD symptoms (Mehdi et al. 2023). In PD, GLP-1R agonists protect against dopaminergic neuronal death induced by 6-hydroxydopamine, and administration of GLP-1 via the lateral ventricle protects mice from MPTP-induced neuronal loss (Li et al. 2009).

Recent research has also revealed that GLP-1 receptors are expressed on astrocytes, making them key targets of GLP-1 (Chowen et al. 1999). Activation of GLP-1R in NTS astrocytes enhances intracellular Ca²⁺ signaling and increases cAMP levels in cultured astrocytes (Reiner et al. 2016). Similar to neuropeptides such as CCK and orexin, GLP-1 may regulate astrocyte activation through modulation of intracellular Ca²⁺ and cAMP levels. In pathological conditions, the protective effects of GLP-1 on astrocytes are well documented. GLP-1R agonists significantly reduce GFAP-positive astrocytes and lower NLRP2 inflammasome expression, thereby improving cortical neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in AD mice (Zhang et al. 2022a). Moreover, dual receptor agonists targeting both GLP-1R and the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) resensitize insulin signaling in the brain and reduce activated astrocyte levels in the cortex and hippocampus of AD rats, ultimately ameliorating learning and memory impairments induced by streptozotocin (Shi et al. 2017).

In stroke models, GLP-1 and its receptor exert significant neuroprotective effects. Treatment with GLP-1 reduces the number of C3d/GFAP-positive A1 astrocytes in the ischemic perifocal region, decreases brain infarction volume, alleviates neuroinflammation, and mitigates BBB disruption, resulting in improved cognitive function (Zhang et al. 2022b). In a diffuse PD mouse model, GLP-1 agonists prevent dopaminergic neuron loss and motor dysfunction by inhibiting the microglia-mediated conversion of astrocytes to the A1 phenotype.

CRH and astrocyte morphology

Research shows that CRHRs on astrocytes modulate various cellular responses—including astrocyte activation and morphological changes—that are critical for neuroinflammation and neuroprotection. In models of ischemic brain injury, pre-treatment with antalarmin effectively reduces glucocorticoid secretion following ischemia-reperfusion injury, alleviates excessive astrocyte activation in the hippocampus, and provides neuroprotection. Antalarmin also improves spatial memory, reduces passive avoidance learning deficits, and mitigates anxiety-related behaviors, emphasizing the potential role of CRHR1 in neural injury and cognitive dysfunction (de la Tremblaye et al. 2017). Additionally, CRHR2 knockout zebrafish exhibit A1 astrocyte activation and display anxiety-like behaviors, indicating that CRHR2 deficiency can lead to astrocyte dysregulation and behavioral changes (Deng et al. 2024b). These findings suggest that CRHR1 and CRHR2 regulate astrocyte function under various physiological and pathological conditions, thereby influencing neural network structure and function.

Ang and astrocyte morphology

Ang II is implicated in various neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, and its impact on astrocyte morphology is particularly noteworthy. Treatment with ferrostatin-1 effectively inhibits Ang II-induced astrocyte activation, ferroptosis, and the expression of AT1R and inflammatory factors (Li et al. 2021). In addition to the classic ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis, the non-canonical ACE2/Ang (1–7)/Mas receptor (MasR) axis has gained attention. In this pathway, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) converts Ang II into Ang (1–7), which then binds to MasR to produce anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroprotective effects. Activation of the ACE2/Ang (1–7)/MasR axis effectively counteracts the pro-inflammatory actions of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis, showing great potential for disease prevention and treatment (Sriramula et al. 2015).

In models of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation, ACE2 activation significantly reduces astrocyte activation in the cortex and hippocampus, downregulates p38 MAPK-mediated inflammatory signaling, and lowers pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (Tiwari et al. 2023). Similarly, in PD models, ACE2 activation decreases glial cell activation, protecting neurons, astrocytes, and microglia from cytotoxicity. By reducing Ang II levels, ACE2 activation upregulates the ACE2/Ang (1–7)/MasR axis, thereby alleviating neuroinflammation in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNPC) and influencing disease progression(Gupta et al. 2022). Moreover, Ang (1–7) analogs regulate astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammation via the lncRNA SNHG14/miR-223-3p/NLRP3 pathway, rescuing cognitive dysfunction in AD mice (Duan et al. 2021).

OXT and astrocyte morphology

OXT plays a significant role in regulating brain functions, and its effects on astrocyte morphology are increasingly recognized. Notably, phenotypic changes in reactive astrocytes are closely linked to decreased OXTR expression (Knoop et al. 2022). Activation of OXTR leads to astrocytic membrane depolarization and increased Ca²⁺ release. Moreover, OXT acting on astrocytes can trigger the retraction of their processes from synapses—a change that may be associated with improved anxiety behaviors in rats (Knoop et al. 2022).

Studies have also shown that intranasal administration of OXT restores bilateral hippocampal OXTR expression, inhibits the overactivation of microglia and astrocytes, and alleviates depressive-like behaviors in models of neuropathic pain and autism (Liu et al. 2024b; Wang et al. 2018). These findings suggest that changes in CNS OXT levels can induce morphological alterations in astrocytes, which play an important role in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Central neuropeptides and astrocyte secretory functions

NPY and astrocyte secretory functions

NPY plays a crucial role in modulating astrocyte secretory functions, especially under conditions of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Research shows that NPY effectively reduces the production of nitric oxide (NO), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in astrocytes, thereby mitigating oxidative damage in the brain. Additionally, NPY inhibits LPS-induced calcium overload and decreases the release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα through Y1R (Chen et al. 2022).

Beyond its antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties, NPY also influences neurotrophic signaling pathways. Overexpression of NPY upregulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in astrocytes—a critical mediator of neuronal survival, plasticity, and repair. This increase in BDNF is linked to reduced astrocyte reactivity, as shown by lower GFAP expression and diminished release of inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α (Pain et al. 2022). These findings suggest that NPY may exert its neuroprotective effects by attenuating astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammation.

VIP and astrocyte secretory functions

VIP is a central neuropeptide that plays a key role in regulating astrocyte secretory functions and mediating neuroprotection. It exerts its effects through two distinct pathways. The direct pathway involves the activation of cAMP, while the indirect pathway operates independently of cAMP and relies on astrocytes as intermediaries. In this indirect mechanism, astrocytes contribute to VIP’s neuroprotective effects through their unique physiological and secretory properties (Deng and Jin 2017).

VIP’s neuroprotective actions are largely attributed to its stimulation of astrocytes to secrete neuroprotective proteins and cytokines, such as activity-dependent neurotrophic/neuroprotective protein (ADNP), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and various macrophage inflammatory proteins (Brenneman et al. 2003; Dejda et al. 2005; Deng and Jin 2017). Furthermore, VIP treatment significantly increases extracellular GSH levels in the striatum—a key antioxidant predominantly secreted by astrocytes—underscoring its regulatory impact on astrocyte activity (Yelkenli et al. 2016).

CRH and astrocyte secretory functions

CRH and urocortins (UCNs) play critical roles in modulating astrocyte secretory functions, which in turn affect synapse formation. Notably, UCN2 exhibits dual effects on synaptogenesis that depend on the presence of astrocytes. In isolated hippocampal neurons, UCN2 suppresses synapse formation, whereas in neurons co-cultured with astrocytes, it significantly promotes synaptogenesis. This astrocyte-dependent enhancement is mediated by the secretion of nerve growth factor (NGF) triggered by the activation of CRHR2. Blocking CRHR2 with the antagonist astressin2B abolishes these effects, as shown by unchanged levels of synapsin I and PSD95 proteins (Zheng et al. 2016).

Conversely, CRH inhibits the astrocytic secretion of CXCL5 via CRHR1 activation. CXCL5, a chemokine that promotes synaptogenesis, is pivotal for astrocytic modulation of neuronal connectivity. The suppression of CXCL5 by CRH leads to reduced synapse formation in hippocampal neurons; however, treatment with the CRHR1 antagonist antalarmin reverses this suppression, restoring synaptogenic activity (Zhang et al. 2018). These findings highlight the contrasting roles of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in astrocyte-mediated synaptic regulation.

OX/HCRT and astrocyte secretory functions

Orexins regulate a range of physiological functions in astrocytes. Activation of OX1R stimulates cAMP synthesis in primary rodent astrocytes, which triggers the release of neurotransmitters (Woldan-Tambor et al. 2011). Moreover, orexin A (OXA) reduces lactate production in hippocampal astrocytes, limits its transfer to neurons, and decreases BDNF expression. These changes impair adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function, leading to anxiety- and depression-like behaviors—a pattern that can be reversed by selectively blocking hippocampal OX1R (Chen et al. 2024). Additionally, orexins inhibit the production and release of inflammatory factors in astrocytes, including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and iNOS, thereby alleviating neuroinflammation. The multifaceted roles of the orexin system make it a promising target for treating neuropsychiatric disorders, and future research will further clarify its complex mechanisms and clinical applications.

GLP-1 and astrocyte secretory functions

Activation of GLP-1 receptors has shown promising effects on astrocyte-mediated functions in the CNS, especially under conditions of stress or injury. Research demonstrates that the long-acting GLP-1R agonist, Exendin-4 (Ex-4), reduces the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and C-X-C motif ligand-1 (CXCL-1) from astrocytes during oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R). These molecules are involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, immune cell recruitment, and inflammatory signaling; their reduction helps to attenuate neuroinflammation and tissue damage. Furthermore, Ex-4 modulates JAK2/STAT3 signaling, leading to a decrease in vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) expression, which is crucial for maintaining BBB integrity (Shan et al. 2019).

In mice pretreated with LPS to simulate AD-like neuroinflammation, GLP-1 agonists reduce amyloid-β deposition, glial activation, and the secretion of inflammatory molecules such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), TNF-α, IL-1β, and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). They also inhibit the activity of the inflammatory NF-κB/TLR4 and Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathways (Kopp et al. 2022).

Central neuropeptides as therapeutic targets

Pharmacological manipulation of central neuropeptides

Pharmacological manipulation of central neuropeptides has emerged as a promising strategy for treating various neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. These neuropeptides play a crucial role in modulating brain function, and their dysregulation has been implicated in diseases such as depression, anxiety, AD, MS, and PD (Rana et al. 2022; Shen et al. 2022). Numerous studies and reviews have explored the roles of neuropeptides in these disorders, aiming either to restore normal neuropeptide function or to enhance their therapeutic effects.

One well-studied approach involves using agonists and antagonists to selectively target neuropeptide receptors. For example, the effects of NPY on astrocytes have potential therapeutic implications for regulating neuroinflammation. In vitro studies have demonstrated that exogenous NPY reduces the inflammatory response of astrocytes to LPS by activating the Y1R. Pre-treatment with NPY significantly attenuates LPS-induced cytotoxicity in C8-D1A astrocytes, lowers GFAP expression, and suppresses the NF-κB signaling pathway by inhibiting the activation of the IKK/IκB/NF-κB p65 complex and preventing IκB degradation. Moreover, NPY reduces the expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1 proteins in these astrocytes (Pain et al. 2022).

Similarly, treatment with VIP, PACAP, or PAC1 receptor agonists effectively prevents motor deficits in MS mouse models and reduces GFAP expression in the corpus callosum. In vitro studies further indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects mediated by PAC1 are largely achieved through astrocytes (Jansen et al. 2024). Together, these mechanisms offer a promising direction for developing new therapeutic strategies for related disorders (Chen et al. 2022).

Gene therapy approaches

Gene therapy approaches have gained increasing attention as potential strategies to modulate the expression of neuropeptides and their receptors in the CNS. Unlike pharmacological treatments, which typically offer only transient effects, gene therapy can provide long-lasting or even permanent therapeutic outcomes by directly altering the genetic makeup of target cells. This method involves delivering genes that encode specific neuropeptides or their receptors into the CNS to either enhance or inhibit their expression (Sudhakar and Richardson 2019).

For example, in postpartum depression (PPD) models, decreased OXTR expression has been observed. Targeted knockout of OXTR in hippocampal astrocytes induces activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, revealing a novel role for the astrocytic OXTR-NLRP3 axis in PPD pathophysiology (Zhu and Tang 2020). Similarly, conditional knockout of AT1R in astrocytes significantly ameliorates amyloid β-induced cognitive dysfunction in AD models by suppressing the β-arrestin2 pathway in the hippocampus (Chen et al. 2023).

Gene therapy offers several advantages over traditional pharmacological treatments. It can target specific neuropeptides or receptors with high precision, potentially reducing the side effects associated with broad-spectrum drugs. Moreover, gene therapy may provide sustained therapeutic effects, which is particularly beneficial for chronic conditions requiring long-term treatment. However, challenges remain, including the safe and efficient delivery of genetic material to the CNS, potential immune responses to viral vectors, and ethical considerations surrounding genetic modifications (Tang and Xu 2020).

Central neuropeptides beyond CNS regions

Beyond their CNS functions, these neuropeptides play pivotal roles in peripheral physiology. For example, NPY regulates appetite, energy balance, and stress responses (Reichmann and Holzer 2016), while VIP and PACAP promote smooth muscle relaxation, vasodilation, and modulate immune responses (Iwasaki et al. 2019; Langer et al. 2022). Similarly, CRH and urocortins not only manage the HPA axis and stress responses in the brain but also influence cardiovascular function and metabolic processes in peripheral tissues (Parkes et al. 2001; Takefuji and Murohara 2019). Angiotensin peptides, derived from angiotensinogen, are essential components of the renin-angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure, fluid balance, and kidney function (Bhandari et al. 2022; Nakayama et al. 2023). Oxytocin, widely recognized for its roles in social bonding and emotional regulation, is also essential for childbirth and lactation (Buckley et al. 2023; Erickson and Emeis 2017). A recent study showed that human intestinal organoids produce oxytocin, indicating that the intestinal epithelium alone is capable of generating this neuropeptide (Danhof et al. 2023). Additionally, orexin not only regulates wakefulness and energy balance in the brain but also modulates appetite and metabolic functions in peripheral tissues (Hashimoto 2025). Finally, GLP-1, produced by both intestinal L cells and the brain, plays a critical role in maintaining glucose homeostasis and stimulating insulin secretion (Cabou and Burcelin 2011; Zheng et al. 2024).

Given the importance of brain-body communication in health and disease (Ma et al. 2025), these neuropeptides integrate central and peripheral signaling to orchestrate a wide range of physiological processes. By bridging the gap between the CNS and the body, they help maintain systemic homeostasis and offer novel therapeutic avenues. Their dual roles underscore the potential of targeting brain-body communication to restore normal neuropeptide function and alleviate symptoms associated with conditions such as AD, PD, depression, and anxiety.

Conclusion and future directions

This review underscores the critical role of central neuropeptides in regulating astrocyte function—impacting their proliferation, morphology, and secretory activities. The dynamic interplay between neuropeptides such as NPY, VIP, PACAP, CRH, angiotensin, oxytocin, orexin, and GLP-1 and astrocytes is essential for maintaining neural homeostasis. Disruptions in these signaling pathways are closely linked to the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders.

The evidence reviewed highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting these neuropeptide systems. Pharmacological agents, receptor agonists/antagonists, and emerging gene therapy approaches have shown promise in modulating astrocyte activity to mitigate neuroinflammation, promote neuroprotection, and improve synaptic function. For example, intranasal administration of NPY has demonstrated antidepressant effects in patients with major depressive disorder (Mathé et al. 2020), and GLP-1R agonists have been shown to reduce inflammation-related proteins in AD patients (Koychev et al. 2024). Notably, central neuropeptides influence multiple aspects of these disorders—including neuroinflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and neuroprotection—by modulating astrocyte states (Table 1 and Table 2). However, challenges remain regarding long-term safety, individual variability, and efficient delivery methods.

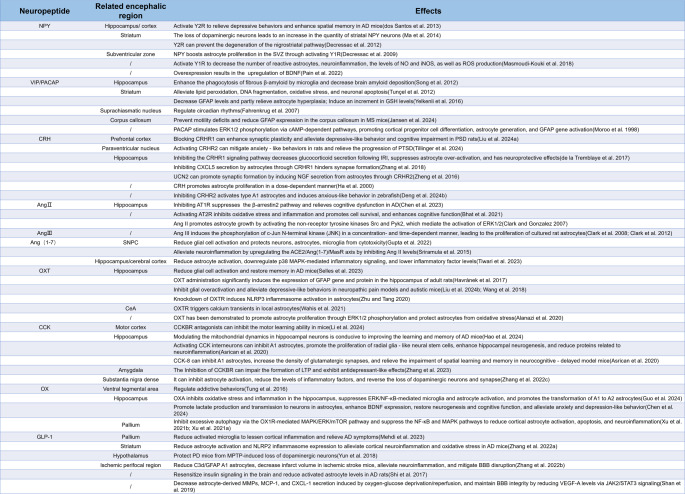

Table 1.

Summary of research on astrocyte state transitions mediated by central neuropeptides in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders

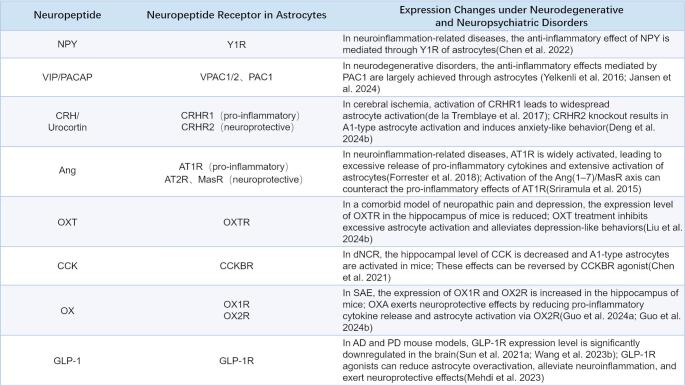

Table 2.

Summary of neuropeptide receptor expression changes in astrocytes under neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders

Looking ahead, future research should focus on elucidating the complex molecular mechanisms underlying neuropeptide-mediated astrocyte regulation. Advanced techniques such as optogenetics, chemogenetics, and single-cell transcriptomics will be crucial for dissecting cell-specific responses and refining therapeutic interventions. Moreover, exploring brain-body communication and the integration of peripheral signals could pave the way for comprehensive treatment strategies that address both central and systemic aspects of these disorders. With continued technological innovation and integrative research, central neuropeptides hold promise as a next-generation, multi-target therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgements

We thank BioRender (https://www.biorender.com) for creating the figures.

Author contributions

Writing - original draft and visualization, M.J.Y., M.J., and M.C.; Writing - review and editing, X.F. and J.J.Y.; Supervision, L.N.H. and J.J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China, Beijing, China (grant numbers U23A20421 and 82201338).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Neither generative AI nor AI-assisted technologies were used throughout the entire writing process.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Meng-jie Yang and Min Jia contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Li-ning Huang, Email: 27701226@hebmu.edu.cn.

Jian-jun Yang, Email: yjyangjj@126.com.

References

- Abiodun OA, Ola MS (2020) Role of brain Renin angiotensin system in neurodegeneration: an update. Saudi J Biol Sci 27:905–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agersnap M, Zhang MD, Harkany T, Hökfelt T, Rehfeld JF (2016) Nonsulfated cholecystokinins in cerebral neurons. Neuropeptides 60:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi MM, Havranek T, Bakos J, Cubeddu LX, Castejon AM (2020) Cell proliferation and anti-oxidant effects of Oxytocin and Oxytocin receptors: role of extracellular signal-regulating kinase in astrocyte-like cells. Endocr Regul 54:172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asim M, Wang H, Waris A, Qianqian G, Chen X (2024) Cholecystokinin neurotransmission in the central nervous system: insights into its role in health and disease. BioFactors 50:1060–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrican B, Wooten J, Li Y-D, Quintanilla L, Zhang F, Wander C, Bao H, Yeh C-Y, Luo Y-J, Olsen R, Lim S-A, Hu J, Jin P, Song J (2020) Neuropeptides modulate local astrocytes to regulate adult hippocampal neural stem cells. Neuron 108:349–366e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakos J, Zatkova M, Bacova Z, Ostatnikova D (2016) The role of hypothalamic neuropeptides in neurogenesis and neuritogenesis. Neural Plast 2016:3276383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B, Pourié G (2013) Ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, and other feeding-regulatory peptides active in the hippocampus: role in learning and memory. Nutr Rev 71:541–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becquet L, Abad C, Leclercq M, Miel C, Jean L, Riou G, Couvineau A, Boyer O, Tan Y-V (2019) Systemic administration of orexin A ameliorates established experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by diminishing neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflamm 16:64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhe DF, Gebre AK, Assefa BT (2020) Orexins role in neurodegenerative diseases: from pathogenesis to treatment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 194:172929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari S, Mehta S, Khwaja A, Cleland JGF, Ives N, Brettell E, Chadburn M, Cockwell P (2022) Renin-Angiotensin system Inhibition in advanced chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 387:2021–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat SA, Fatima Z, Sood A, Shukla R, Hanif K (2021) The protective effects of AT2R agonist, CGP42112A, against angiotensin II-Induced oxidative stress and inflammatory response in astrocytes: role of AT2R/PP2A/NFκB/ROS signaling. Neurotox Res 39:1991–2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeld P, Martirosyan A, Martín-Suárez S, Apresyan A, Meerhoff GF, Pestana F, Poovathingal S, Reijner N, Koning W, Clement RA, Van der Veen I, Toledo EM, Polzer O, Durá I, Hovhannisyan S, Nilges BS, Bogdoll A, Kashikar ND, Lucassen PJ, Belgard TG, Encinas JM, Holt MG, Fitzsimons CP (2024) Traumatic brain injury promotes neurogenesis at the cost of astrogliogenesis in the adult hippocampus of male mice. Nat Commun 15:5222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenneman DE, Phillips TM, Hauser J, Hill JM, Spong CY, Gozes I (2003) Complex array of cytokines released by vasoactive intestinal peptide. Neuropeptides 37:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley S, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Pajalic Z, Luegmair K, Ekström-Bergström A, Dencker A, Massarotti C, Kotlowska A, Callaway L, Morano S, Olza I, Magistretti CM (2023) Maternal and newborn plasma Oxytocin levels in response to maternal synthetic Oxytocin administration during labour, birth and postpartum - a systematic review with implications for the function of the Oxytocinergic system. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23:137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabou C, Burcelin R (2011) GLP-1, the gut-brain, and brain-periphery axes. Rev Diabet Stud 8:418–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casello SM, Flores RJ, Yarur HE, Wang H, Awanyai M, Arenivar MA, Jaime-Lara RB, Bravo-Rivera H, Tejeda HA (2022) Neuropeptide system regulation of prefrontal cortex circuitry: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Neural Circuits 16:796443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla B, Fernández-Pérez A, Perea G, Araque A, Vallejo M (2008) DREAM mediates cAMP-dependent, Ca2+-induced stimulation of GFAP gene expression and regulates cortical astrogliogenesis. J Neurosci 28:6703–6713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai H, Diaz-Castro B, Shigetomi E, Monte E, Octeau JC, Yu X, Cohn W, Rajendran PS, Vondriska TM, Whitelegge JP, Coppola G, Khakh BS (2017) Neural Circuit-Specialized astrocytes: transcriptomic, proteomic, morphological, and functional evidence. Neuron 95:531–549e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheli VT, Santiago González DA, Smith J, Spreuer V, Murphy GG, Paez PM (2016) L-type voltage-operated calcium channels contribute to astrocyte activation in vitro. Glia 64:1396–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Zhao CM, Håkanson R, Samuelson LC, Rehfeld JF, Friis-Hansen L (2004) Altered control of gastric acid secretion in gastrin-cholecystokinin double mutant mice. Gastroenterology 126:476–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yang N, Li Y, Li Y, Hong J, Wang Q, Liu K, Han D, Han Y, Mi X, Shi C, Zhou Y, Li Z, Liu T, Guo X (2021) Cholecystokinin octapeptide improves hippocampal glutamatergic synaptogenesis and postoperative cognition by inhibiting induction of A1 reactive astrocytes in aged mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 27:1374–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Liang Z, Yue Q, Wang X, Siu SWI, Pui-Man Hoi M, Lee SM (2022) A neuropeptide Y/F-like polypeptide derived from the transcriptome of Turbinaria peltata suppresses LPS-Induced astrocytic inflammation. J Nat Prod 85:1569–1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Gao R, Song Y, Xu T, Jin L, Zhang W, Chen Z, Wang H, Wu W, Zhang S, Zhang G, Zhang N, Chang L, Liu H, Li H, Wu Y (2023) Astrocytic AT1R deficiency ameliorates Aβ-induced cognitive deficits and synaptotoxicity through β-arrestin2 signaling. Prog Neurobiol 228:102489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Jin K, Dong J, Cheng S, Kong L, Hu S, Chen Z, Lu J (2024) Hypocretin-1/Hypocretin receptor 1 regulates neuroplasticity and cognitive function through hippocampal lactate homeostasis in depressed model. Adv Sci (Weinh) 11:e2405354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowen JA, de Fonseca FR, Alvarez E, Navarro M, García-Segura LM, Blázquez E (1999) Increased glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor expression in glia after mechanical lesion of the rat brain. Neuropeptides 33:212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Gonzalez N (2007) Src and Pyk2 mediate angiotensin II effects in cultured rat astrocytes. Regul Pept 143:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Guillaume G, Pierre-Louis HC (2008) Angiotensin II induces proliferation of cultured rat astrocytes through c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Brain Res Bull 75:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Nguyen C, Tran H (2012) Angiotensin III induces c-Jun N-terminal kinase leading to proliferation of rat astrocytes. Neurochem Res 37:1475–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LE, Liddelow SA, Chakraborty C, Münch AE, Heiman M, Barres BA (2018) Normal aging induces A1-like astrocyte reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:E1896-e1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby KM, Murphy-Royal C, Wilson SA, Gordon GR, Bains JS, Pittman QJ (2018) Cholecystokinin switches the plasticity of GABA synapses in the dorsomedial hypothalamus via astrocytic ATP release. J Neurosci 38:8515–8525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhof HA, Lee J, Thapa A, Britton RA, Di Rienzi SC (2023) Microbial stimulation of Oxytocin release from the intestinal epithelium via secretin signaling. Gut Microbes 15:2256043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Tremblaye PB, Benoit SM, Schock S, Plamondon H (2017) CRHR1 exacerbates the glial inflammatory response and alters bdnf/trkb/pcreb signaling in a rat model of global cerebral ischemia: implications for neuroprotection and cognitive recovery. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 79:234–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decressac M, Prestoz L, Veran J, Cantereau A, Jaber M, Gaillard A (2009) Neuropeptide Y stimulates proliferation, migration and differentiation of neural precursors from the subventricular zone in adult mice. Neurobiol Dis 34:441–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decressac M, Pain S, Chabeauti PY, Frangeul L, Thiriet N, Herzog H, Vergote J, Chalon S, Jaber M, Gaillard A (2012) Neuroprotection by neuropeptide Y in cell and animal models of parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 33:2125–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejda A, Sokołowska P, Nowak JZ (2005) Neuroprotective potential of three neuropeptides PACAP, VIP and PHI. Pharmacol Rep 57:307–320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng G, Jin L (2017) The effects of vasoactive intestinal peptide in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurol Res 39:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Guo A, Huang Z, Guan K, Zhu Y, Chan C, Gui J, Song C, Li X (2024a) The exploration of neuroinflammatory mechanism by which CRHR2 deficiency induced anxiety disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 128:110844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Guo A, Huang Z, Guan K, Zhu Y, Chan C, Gui J, Song C, Li X (2024b) The exploration of neuroinflammatory mechanism by which CRHR2 deficiency induced anxiety disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 128:110844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Scala-Guenot D, Strosser MT (1992) Oxytocin receptors on cultured astroglial cells. Kinetic and Pharmacological characterization of oxytocin-binding sites on intact hypothalamic and hippocampic cells from foetal rat brain. Biochem J 284(Pt 2):491–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Scala-Guenot D, Mouginot D, Strosser MT (1994) Increase of intracellular calcium induced by Oxytocin in hypothalamic cultured astrocytes. Glia 11:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diz-Chaves Y, Mastoor Z, Spuch C, González-Matías LC, Mallo F (2022) Anti-Inflammatory effects of GLP-1 receptor activation in the brain in neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci 23:9583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- dos Santos VV, Santos DB, Lach G, Rodrigues AL, Farina M, De Lima TC, Prediger RD (2013) Neuropeptide Y (NPY) prevents depressive-like behavior, Spatial memory deficits and oxidative stress following amyloid-β (Aβ(1–40)) administration in mice. Behav Brain Res 244:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan R, Wang SY, Wei B, Deng Y, Fu XX, Gong PY, E Y, Sun XJ, Cao HM, Shi JQ, Jiang T, Zhang YD (2021) Angiotensin-(1–7) analogue AVE0991 modulates Astrocyte-Mediated neuroinflammation via LncRNA SNHG14/miR-223-3p/NLRP3 pathway and offers neuroprotection in a Transgenic mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J Inflamm Res 14:7007–7019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Neves J, Pereira de Almeida L, Cavadas C (2016) Neuropeptide Y (NPY) as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis 95:210–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo F, Kasai A, Soto JS, Yu X, Qu Z, Hashimoto H, Gradinaru V, Kawaguchi R, Khakh BS (2022) Molecular basis of astrocyte diversity and morphology across the CNS in health and disease. Science 378:eadc9020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson EN, Emeis CL (2017) Breastfeeding outcomes after Oxytocin use during childbirth: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health 62:397–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escartin C, Galea E, Lakatos A, O’Callaghan JP, Petzold GC, Serrano-Pozo A, Steinhäuser C, Volterra A, Carmignoto G, Agarwal A, Allen NJ, Araque A, Barbeito L, Barzilai A, Bergles DE, Bonvento G, Butt AM, Chen WT, Cohen-Salmon M, Cunningham C, Deneen B, De Strooper B, Díaz-Castro B, Farina C, Freeman M, Gallo V, Goldman JE, Goldman SA, Götz M, Gutiérrez A, Haydon PG, Heiland DH, Hol EM, Holt MG, Iino M, Kastanenka KV, Kettenmann H, Khakh BS, Koizumi S, Lee CJ, Liddelow SA, MacVicar BA, Magistretti P, Messing A, Mishra A, Molofsky AV, Murai KK, Norris CM, Okada S, Oliet SHR, Oliveira JF, Panatier A, Parpura V, Pekna M, Pekny M, Pellerin L, Perea G, Pérez-Nievas BG, Pfrieger FW, Poskanzer KE, Quintana FJ, Ransohoff RM, Riquelme-Perez M, Robel S, Rose CR, Rothstein JD, Rouach N, Rowitch DH, Semyanov A, Sirko S, Sontheimer H, Swanson RA, Vitorica J, Wanner IB, Wood LB, Wu J, Zheng B, Zimmer ER, Zorec R, Sofroniew MV, Verkhratsky A (2021) Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat Neurosci 24:312–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrug J, Popovic N, Georg B, Brundin P, Hannibal J (2007) Decreased VIP and VPAC2 receptor expression in the biological clock of the R6/2 huntington’s disease mouse. J Mol Neurosci 31:139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YY, Huo J (2021) A1/A2 astrocytes in central nervous system injuries and diseases: angels or devils? Neurochem Int 148:105080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ (1998) Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest 101:515–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester SJ, Booz GW, Sigmund CD, Coffman TM, Kawai T, Rizzo V, Scalia R, Eguchi S (2018) Angiotensin II signal transduction: an update on mechanisms of physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 98:1627–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronczek R, Schinkelshoek M, Shan L, Lammers GJ (2021) The orexin/hypocretin system in neuropsychiatric disorders: relation to signs and symptoms. Handb Clin Neurol 180:343–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geloso MC, Corvino V, Di Maria V, Marchese E, Michetti F (2015) Cellular targets for neuropeptide Y-mediated control of adult neurogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci 9:85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazy AA, Soliman OA, Elbahnasi AI, Alawy AY, Mansour AM, Gowayed MA (2023) Role of Oxytocin in different neuropsychiatric, neurodegenerative, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 186:95–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gøtzsche CR, Woldbye DPD (2016) The role of NPY in learning and memory. Neuropeptides 55:79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Kong D, Luo J, Xiong T, Wang F, Deng M, Kong Z, Yang S, Da J, Chen C, Lan J, Chu L, Han G, Liu J, Tan Y, Zhang J (2024a) Orexin-A attenuates the inflammatory response in Sepsis-Associated encephalopathy by modulating oxidative stress and inhibiting the ERK/NF-κB signaling pathway in microglia and astrocytes. CNS Neurosci Ther 30:e70096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Kong Z, Yang S, Da J, Chu L, Han G, Liu J, Tan Y, Zhang J (2024b) Therapeutic effects of orexin-A in sepsis-associated encephalopathy in mice. J Neuroinflammation 21:131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Tiwari V, Tiwari P, Parul, Mishra A, Hanif K, Shukla S (2022) Angiotensin-Converting enzyme 2 activation mitigates behavioral deficits and neuroinflammatory burden in 6-OHDA induced experimental models of parkinson’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci 13:1491–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Advani D, Yadav D, Ambasta RK, Kumar P (2023) Dissecting the relationship between neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Neurobiol 60:6476–6529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha BK, Bishop GA, King JS, Burry RW (2000) Corticotropin releasing factor induces proliferation of cerebellar astrocytes. J Neurosci Res 62:789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadadianpour Z, Fatehi F, Ayoobi F, Kaeidi A, Shamsizadeh A, Fatemi I (2017) The effect of orexin-A on motor and cognitive functions in a rat model of parkinson’s disease. Neurol Res 39:845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Shi M, Ma J, Shao S, Yuan Y, Liu J, Yu Z, Zhang Z, Hölscher C, Zhang Z (2024) A cholecystokinin analogue ameliorates cognitive deficits and regulates mitochondrial dynamics via the AMPK/Drp1 pathway in APP/PS1 mice. J Prev Alzheimer’s Disease 11:382–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K (2025) Evaluating the safety of orexin receptor antagonists on reproductive health and sexual function. Mol Psychiatry 30:1161–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havránek T, Lešťanová Z, Mravec B, Štrbák V, Bakoš J, Bačová Z (2017) Oxytocin modulates expression of neuron and glial markers in the rat Hippocampus. Folia Biol (Praha) 63:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst JJ (2007) The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol Rev 87:1409–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovino M, Messana T, Tortora A, Giusti C, Lisco G, Giagulli VA, Guastamacchia E, De Pergola G, Triggiani V (2021) Oxytocin signaling pathway: from cell biology to clinical implications. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 21:91–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M, Akiba Y, Kaunitz JD (2019) Recent advances in vasoactive intestinal peptide physiology and pathophysiology: focus on the gastrointestinal system. F1000Res 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jansen MI, Mahmood Y, Lee J, Broome ST, Waschek JA, Castorina A (2024) Targeting the PAC1 receptor mitigates degradation of Myelin and synaptic markers and diminishes locomotor deficits in the Cuprizone demyelination model. J Neurochem 168:3250–3267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao H, Wang Y, Fu K, Xiao X, Jia MQ, Sun J, Wang J, Zhu G, Lyu D, Lu Q, Peng Y, Lv J, Su L, Gao Y (2024) An orexin-receptor-2-mediated heart-brain axis in cardiac pain. iScience 27:109067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PL, Truitt W, Fitz SD, Minick PE, Dietrich A, Sanghani S, Träskman-Bendz L, Goddard AW, Brundin L, Shekhar A (2010) A key role for orexin in panic anxiety. Nat Med 16:111–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurga AM, Paleczna M, Kadluczka J, Kuter KZ (2021) Beyond the GFAP-Astrocyte protein markers in the brain. Biomolecules 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Katzman MA, Katzman MP (2022) Neurobiology of the orexin system and its potential role in the regulation of hedonic tone. Brain Sci 12:150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khodagholi F, Maleki A, Motamedi F, Mousavi MA, Rafiei S, Moslemi M (2022) Oxytocin prevents the development of 3-NP-Induced anxiety and depression in male and female rats: possible interaction of OXTR and mGluR2. Cell Mol Neurobiol 42:1105–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoop M, Possovre ML, Jacquens A, Charlet A, Baud O, Darbon P (2022) The role of oxytocin in abnormal brain development: effect on glial cells and neuroinflammation. Cells 11:3899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kopp KO, Glotfelty EJ, Li Y, Greig NH (2022) Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and neuroinflammation: implications for neurodegenerative disease treatment. Pharmacol Res 186:106550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowall NW, Beal MF (1988) Cortical somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and NADPH diaphorase neurons: normal anatomy and alterations in alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 23:105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koychev I, Reid G, Nguyen M, Mentz RJ, Joyce D, Shah SH, Holman RR (2024) Inflammatory proteins associated with alzheimer’s disease reduced by a GLP1 receptor agonist: a post hoc analysis of the EXSCEL randomized placebo controlled trial. Alzheimers Res Ther 16:212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisch B, Mentlein R (1994) Neuropeptide receptors and astrocytes. Int Rev Cytol 148:119–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer I, Jeandriens J, Couvineau A, Sanmukh S, Latek D (2022) Signal transduction by VIP and PACAP receptors. Biomedicines 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lau SH, Young CH, Zheng Y, Chen X (2023) The potential role of the cholecystokinin system in declarative memory. Neurochem Int 162:105440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]