Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) play important roles in transcriptional regulation and pathogenesis of cancer. Thus, HDAC inhibitors are candidate drugs for differentiation therapy of cancer. Here, we show that the well-tolerated antiepileptic drug valproic acid is a powerful HDAC inhibitor. Valproic acid relieves HDAC-dependent transcriptional repression and causes hyperacetylation of histones in cultured cells and in vivo. Valproic acid inhibits HDAC activity in vitro, most probably by binding to the catalytic center of HDACs. Most importantly, valproic acid induces differentiation of carcinoma cells, transformed hematopoietic progenitor cells and leukemic blasts from acute myeloid leukemia patients. More over, tumor growth and metastasis formation are significantly reduced in animal experiments. Therefore, valproic acid might serve as an effective drug for cancer therapy.

Keywords: cancer therapy/HDAC inhibitor/histone deacetylase/leukemia/valproic acid

Introduction

Local remodeling of chromatin and dynamic changes in the nucleosomal packaging of DNA are key steps in the regulation of gene expression, consequently affecting proper cell function, differentiation and proliferation. One of the most important mechanisms in chromatin remodeling is the post-translational modification of the N-terminal tails of histones by acetylation, which apparently contributes to a ‘histone code’ determining the activity of target genes (Strahl and Allis, 2000). Acetylation of histones and possibly other substrates is mediated by enzymes with histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. Conversely, acetyl groups are removed by histone deacetylases (HDACs). Both HAT and HDAC activities are recruited to target genes in complexes with sequence-specific transcription factors and their cofactors, e.g. corepressors such as N-CoR and SMRT, and coactivators (Chen and Evans, 1995; Hörlein et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1999). Nuclear receptors were the main examples of transcription factors recruiting HAT- and HDAC-associated cofactors depending on their status of activation by an appropriate ligand (Alland et al., 1997; Heinzel et al., 1997; Nagy et al., 1997; Glass and Rosenfeld, 2000). Other transcription factors such as Mad-1, BCL-6 and ETO have also been shown to assemble HDAC-dependent transcriptional repressor complexes (Laherty et al., 1997; Dhordain et al., 1998; Gelmetti et al., 1998; Lutterbach et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1998).

Inappropriate repression of genes required for cell differentiation has been linked to several forms of cancer, particularly to acute leukemia. In acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) patients, retinoic acid receptor (RAR) fusion proteins (e.g. PML–RAR or PLZF–RAR) resulting from chromosomal translocations can interact with components of the corepressor complex (Grignani et al., 1998; Guidez et al., 1998; He et al., 1998; Lin et al., 1998). The hypothesis that corepressor-mediated aberrant repression may be causal for pathogenesis in APL is supported by the finding that the differentiation block in cells transformed by PLZF–RAR is overcome by combined treatment with retinoic acid (RA) and trichostatin A (TSA), which inhibits HDAC activity. Furthermore, a PML–RAR patient who had experienced multiple relapses after RA therapy has been treated with the HDAC inhibitor phenylbutyrate, resulting in complete remission (Warrell et al., 1998).

HDAC inhibitors also appear to induce differentiation and/or apoptosis of transformed cells of non-hematopoietic origin without evidence for aberrant repression. Several structurally diverse HDAC inhibitors have been identified and their activity in transformed cells in vitro renders them prime candidates for cancer therapy (Marks et al., 2000; Krämer et al., 2001). However, some HDAC inhibitors (e.g. trapoxin) are of limited therapeutic use due to poor bioavailability in vivo as well as toxic side effects at high doses. Butyrate and phenylbutyrate are degraded rapidly after i.v. administration and therefore require high doses exceeding 400 mg/kg/day (Warrell et al., 1998). Furthermore, these compounds are not specific for HDACs as they also inhibit phosphorylation and methylation of proteins as well as DNA methylation (Newmark and Young, 1995).

Valproic acid (VPA, 2-propylpentanoic acid) is an established drug in the long-term therapy of epilepsy. Although VPA is well tolerated by patients, it can induce birth defects such as neural tube closure defects and other malformations when administered during early pregnancy (DiLiberti et al., 1984; Nau et al., 1991). Teratogenicity and antiepileptic activity appear to require different mechanisms of action because modifications of the molecule generate selective compounds with either teratogenic or antiepileptic activity (Nau et al., 1991). However, neither of the mechanisms of action is well understood at present (Löscher, 1999). During the search for mediators of VPA teratogenicity, attention had been drawn to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) because VPA induces proliferation of peroxisomes in the rodent liver (Horie and Suga, 1985; Göttlicher et al., 1992; Kliewer et al., 1994; Kersten et al., 2000). PPARδ is activated by VPA and its teratogenic derivatives (Lampen et al., 1999; Werling et al., 2001). The failure to show binding of VPA to PPARδ raised the possibility that VPA and its teratogenic derivatives activate the receptor by a mechanism distinct from binding as a ligand.

Here we show that VPA inhibits corepressor-associated HDACs at therapeutically employed concentrations and acts as a potent inducer of differentiation in several types of transformed cells.

Results

Relief of transcriptional repression by VPA

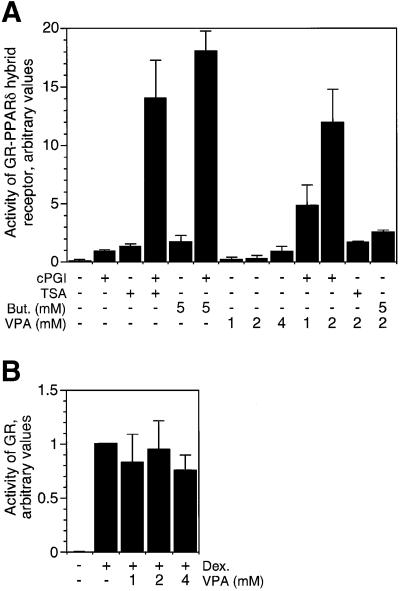

Induction of peroxisomal proliferation and activation of a glucocorticoid receptor (GR)–PPARδ hybrid receptor by VPA pointed towards PPARδ as a potential target of VPA (Werling et al., 2001). Activation of PPARδ by VPA (Figure 1A) could be caused by activation of the PPARδ ligand-binding domain and subsequent recruitment of coactivators (Xu et al., 1999). Alternatively, VPA could release PPARδ-dependent transcriptional repression and allow at least partial activation of reporter gene expression probably in conjunction with low levels of endogenous PPARδ ligands. To discriminate between these possibilities, synergism of VPA was tested together with either a bona fide ligand of PPARδ (cPGI2) or HDAC inhibitors (Figure 1A). The PPARδ ligand cPGI2 and VPA both activate the GR–PPARδ hybrid receptor. Since cPGI2 and HDAC inhibitors, such as TSA or butyrate, synergistically activate the GR–PPARδ hybrid receptor, an agonistic ligand alone is insufficient for full activation and derepression. VPA at concentrations of 1 or 2 mM acts synergistically with cPGI2 but not with TSA or butyrate (Figure 1A). Highly synergistic activation of the reporter gene by VPA together with cPGI2 and lack of synergism with TSA or butyrate indicates that VPA does not act like a ligand to PPARδ but rather like an inhibitor of repression. No synergism is found with receptors such as the GR (Figure 1B) or a PPARα fusion protein (data not shown) which do not recruit corepressor-associated HDACs.

Fig. 1. HDAC inhibitor-like activation of PPARδ by VPA. (A) A cell line expressing the ligand-binding domain of PPARδ fused to the DNA-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) together with a GR-controlled reporter gene was treated for 40 h with the PPARδ ligand cPGI2 (5 µM), VPA or the HDAC inhibitors sodium butyrate (But) and TSA (300 nM). Reporter gene activity was monitored by enzymatic assay for alkaline phosphatase. Values were normalized between experiments according to cPGI2-induced activity. (B) A cell line overexpressing full-length GR was tested as a control. Dexamethasone (1 µM) was used as a GR-specific ligand. Values are means ± SD from duplicate determinations in 2–5 independent experiments.

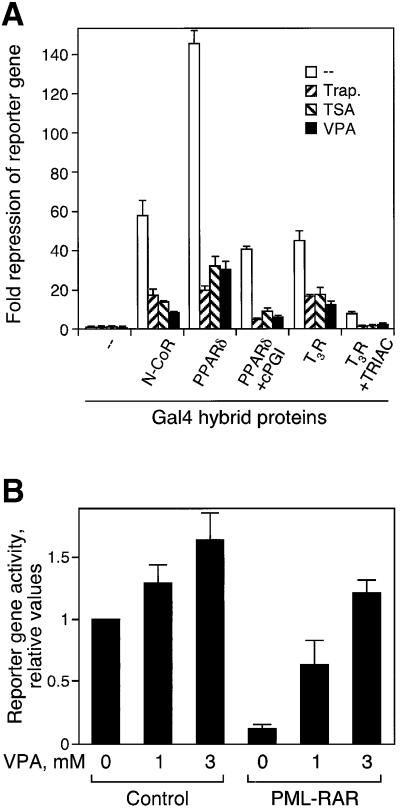

A direct assay for transcriptional repressor activity is based on repression of a high-baseline promoter. Many transcription factors including thyroid hormone receptor (TR), PPARδ and the corepressors N-CoR or mSin3 repress transcription of a promoter containing UAS elements when bound as fusion proteins with the heterologous DNA-binding domain of the Gal4 protein (Heinzel et al., 1997). In the absence of the Gal4 fusion proteins, the reporter has a high basal transcriptional activity due to the presence of binding sites for other transcription factors in the thymidine kinase promoter. The Gal4 fusion proteins strongly repress this activity (Figure 2). VPA at a concentration of 1 mM induces relief of this repression by Gal4 fusions of N-CoR, TR or PPARδ (Figure 2A), ETO or Mad1 (data not shown) as efficiently as established HDAC inhibitors. This relief of repression is also found after partial activation of nuclear receptors with their respective ligands (Figure 2A). Moreover, oncogenic RAR fusion proteins such as PML–RAR repress RAR-dependent reporter gene expression after transient transfection. This repression is relieved efficiently by VPA (Figure 2B). Thus, VPA affects the activity of several transcriptional repressors, suggesting that it acts on a common factor in gene regulation such as corepressor-associated HDACs rather than on individual transcription factors or receptors.

Fig. 2. VPA relieves HDAC-mediated transcriptional repression. (A) HeLa cells were co-transfected with a UAS-TK-luciferase reporter, an SV40 β-Gal control reporter and vectors expressing either the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (amino acids 1–147) or GAL4 fusions of N-CoR (amino acids 1–2453) or the ligand-binding domains of TRβ (amino acids 165–456) with or without TRIAC, or PPARδ (amino acids 138–440) with or without cPGI2, respectively. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with trapoxin (10 nM), TSA (100 nM) or VPA (1 mM) for 16–20 h. Subsequently, cells were harvested and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured. Results are represented as fold repression relative to GAL4. Values are means ± SD from triplicate determinations in two independent experiments. (B) Phoenix cells were co-transfected with the indicated expression vectors, using a luciferase reporter based on the human RARβ2 promoter (de Thé et al., 1990). VPA (1 or 3 mM) was added 18 h after transfections, and cells were analyzed for reporter activity after an additional 24 h.

HDAC inhibition by VPA

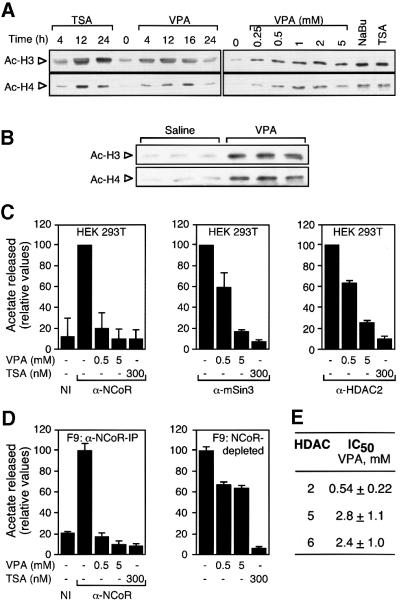

We tested whether VPA can lead to HDAC inhibition by analyzing the degree of histone acetylation in vitro and in vivo with an antibody specific for hyperacetylated histones H3 or H4 (Figure 3). Only minute amounts of acetylated histones are detected in untreated F9 teratocarcinoma or HeLa cells. Treatment with VPA at concentrations as low as 0.25 mM increases the amount of acetylated histone H4, and massive acetylation is found with 2 mM VPA (Figure 3A). This acetylation level is similar to that induced by 5 mM butyrate and slightly less than that by 100 nM TSA. Maximum bulk histone acetylation appears ∼12–16 h after addition of VPA. VPA treatment of mice also induces hyperacetylation of histones in spleen (Figure 3B). To test whether VPA directly inhibits HDAC activity, 3H-labeled acetylated histones were deacetylated using anti-N-CoR, anti-mSin3 or anti-HDAC2 immunoprecipitates from HEK293T (Figure 3C) and F9 (Figure 3D and data not shown) cell extracts as a source of HDAC enzymatic activity. Immunoprecipitates typically contain 25–30% (N-CoR) or 15–20% (mSin3) of the HDAC activity of whole-cell extracts. Already at a concentration of 0.5 mM, VPA inhibits N-CoR-associated HDAC activity almost as efficiently as TSA (300 nM) or sodium butyrate (1 mM, data not shown). As no further washing which could remove any component is performed after the addition of VPA, and since VPA does not induce dissociation of HDAC3 from the N-CoR immunoprecipitate (data not shown), enzyme inhibition is most likely to be due to direct effects on HDACs rather than disintegration of the complex. HDAC activities precipitated from both F9 and HEK293T cells with antibodies directed against mSin3 or HDAC2 are also inhibited by VPA, although slightly higher concentrations appear to be required (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3. VPA induces accumulation of hyperacetylated histone and inhibits HDAC activity. (A) HDAC inhibitors induce the accumulation of hyperacetylated histones H3 and H4. Both the time course and the required concentration for VPA-induced hyperacetylation were determined by western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts from F9 cells treated with VPA (1 mM if not indicated otherwise) in comparison with TSA (100 nM) and sodium butyrate (NaBu, 5 mM). Treatment was for 12 h or as indicated. Equal loading was confirmed by Coomassie Blue staining. Experiments were performed three times with similar results also in HeLa cells. (B) Histone hyperacetylation in vivo was determined by western blot analysis of histones H3 and H4 from mouse splenocyte nuclear extracts. Three mice each were injected i.p. with 25 ml/kg body weight of 155 mM solutions of NaCl or sodium valproate. Due to the short half-life of VPA in rodents, another dose (50%) was readministered after 5 h. Extracts were prepared 10 h after the initial dose. (C) HDAC activity was determined by the release of [3H]acetate from hyperacetylated radiolabeled histones. Activities were determined in the presence of the indicated compounds in immune precipitates from HEK293T cell extracts with antibodies directed against N-CoR, mSin3 or HDAC2. The HDAC activity which precipitated with a non-related immune serum (NI) was determined for control. Values are presented relative to the activity in the absence of HDAC inhibitors. The 100% values normalized for ∼1 mg of extract in representative experiments correspond to 1000 (N-CoR), 500 (mSin3) and 300 c.p.m. (HDAC2). Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (D) HDAC activity was determined in immune precipitates from F9 cell extracts with antibodies directed against N-CoR and in N-CoR-depleted extracts. Efficiency of N-CoR depletion was assessed by western blot for N-CoR in the IP pellet as well as in equivalent amounts of whole-cell extracts before and after depletion (data not shown). (E) IC50 values were calculated as those concentrations required for 50% inhibition of [3H]acetate release. HDAC assays were performed using immune precipitates from F9 cell extracts with antibodies directed against HDACs 2, 5 or 6. HDACs 5 or 6 were precipitated from extracts which had been depleted with antibodies directed against N-CoR, mSin3 and HDACs 1–3.

A significant difference between HEK293T and F9 cells is found when the sensitivity to VPA of N-CoR-depleted supernatants is analyzed. Those HDACs which remain in the N-CoR-depleted supernatant of HEK293T cells are inhibited by VPA as efficiently as those in the precipitate (data not shown). The N-CoR-depleted supernatant from F9 cell extracts, however, is only inhibited by <40% even in the presence of 5 mM VPA, although TSA inhibits this HDAC activity completely (Figure 3D). This finding suggests that the spectrum of HDACs which are not tightly associated with N-CoR differs between the two cell types and that not all HDAC isoforms may be inhibited with equal efficiency by VPA. Significant levels of class II HDACs 5 and 6 were detectable in depleted F9 but not in HEK293T cell extracts (data not shown), suggesting that in F9 cells a substantial fraction of HDACs 5 and 6 is not associated with N-CoR. The IC50 concentrations for HDACs 5 and 6 precipitated from F9 cell extracts depleted with N-CoR, mSin3 and HDAC 1–3 antibodies were determined as 2.8 and 2.4 mM VPA, respectively (Figure 3E). Nevertheless, TSA inhibits the HDACs 5 and 6 precipitates with efficiency similar to the class I HDAC precipitates. These results suggest that these class II HDACs may be significantly less susceptible to inhibition by VPA than class I enzymes, whereas many other HDAC inhibitors do not discriminate between isoenzymes.

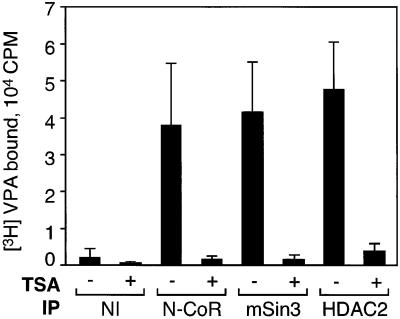

To investigate further the mechanism of HDAC inhibition, we performed binding studies with radiolabeled VPA. [3H]VPA binds to protein complexes precipitated with antibodies against N-CoR, mSin3 or HDAC2 in vitro (Figure 4). TSA has been shown to bind directly to the active site of a deacetylase (Finnin et al., 1999). Since TSA efficiently competes for binding of [3H]VPA, both compounds not only exert similar effects on HDAC activity but also appear to share identical or overlapping binding sites. Therefore, we speculate that the mechanism of HDAC inhibition by VPA involves blocking of substrate access to the catalytic center of the enzyme.

Fig. 4. Binding of VPA to corepressor or HDAC2 immunoprecipitates. Antibodies directed against N-CoR, mSin3 and HDAC2 co-precipitate substantial HDAC activity, most probably in the form of multiprotein complexes (Figure 3C). Immunoprecipitates from HEK293T cell extracts were incubated with 2 µCi of 3H-labeled VPA in the presence or absence of TSA (100 nM). Radioactivity retained after washing is shown. Values are means ± SD from three independent experiments carried out in duplicate.

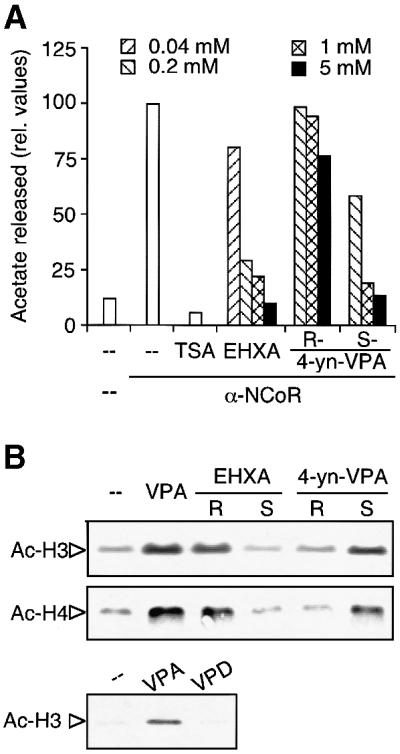

VPA has several activities which are unlikely to follow the same mechanisms of action. The antiepileptic activity and teratogenic side effects can be dissociated by appropriate modifications of the VPA molecule. Both stereoisomers of 4-yn-VPA (2-propinyl-pentanoic acid) exhibit identical low antiepileptic activity, although only one of them (S-4-yn-VPA) is teratogenic (Nau et al., 1991). Similarly, only one of the stereoisomers of the chemically related 2-ethylhexanoic acid (R-EHXA) is teratogenic, whereas S-EHXA is not (Hauck et al., 1990). Valpromide (VPD) is an even more potent antiepileptic drug than VPA but lacks substantial teratogenicity (Löscher and Nau, 1985; Radatz et al., 1998). Isomers of 4-yn-VPA and EHXA as well as VPA and VPD were used to test whether HDAC activity is associated with one of the previously known activities. HDAC activity in vitro is only inhibited by the teratogenic compounds S-4-yn-VPA, racemic EHXA (Figure 5A) and VPA (Figure 3 and data not shown). Also, accumulation of hyperacetylated histones H3 and H4 is induced only by the teratogenic stereoisomers of 4-yn-VPA and EHXA. Histone acetylation is not induced in cells treated with the non-teratogenic isomers or by VPD (Figure 5B). In summary, we identified several VPA-related compounds which clearly separate antiepileptic properties from HDAC inhibitory activity, whereas a strict correlation of HDAC inhibition and teratogenic activity was observed.

Fig. 5. HDAC inhibition by compounds related to VPA. (A) VPA and the related compounds EHXA, and R- and S-4-yn-VPA at the indicated concentrations were tested for HDAC inhibitory activity. Addition of TSA (100 nM) to the reaction served as a control. The assays were performed with N-CoR immunoprecipitates from HEK293T cells in duplicate (untreated enzyme activity 2205 c.p.m. = 100%). Precipitates of a pre-immune serum served as a negative control. (B) Accumulation of hyperacetylated histones H3 and H4 in F9 cells treated with compounds related to VPA was determined as described in the legend to Figure 3. Cells were treated for 12 h with 1 mM of VPA, R- or S-EHXA, R- or S-4-yn-VPA or VPD. One representative out of two similar experiments is shown.

Differentiation of transformed cells in vitro and in vivo

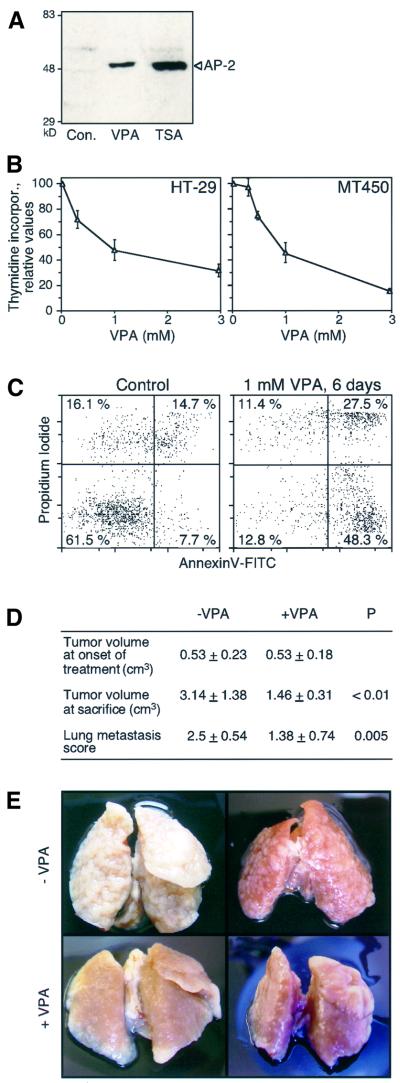

HDAC inhibitors apparently affect cells of hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic origin by inducing cellular differentiation and/or apoptosis. Thus several cell lines of epithelial origin were tested for responsiveness to VPA. In F9 teratocarcinoma cells, VPA induces a specific type of differentiation characterized by reduced proliferation, morphological alterations, marker gene expression and particularly the accumulation of the AP-2 transcription factor as a potential marker of neuronal or neural crest cell-like differentiation (Werling et al., 2001). This type of differentiation is indistinguishable from TSA-induced differentiation by morphological criteria and by accumulation of AP-2 (Figure 6A), suggesting that it is caused by the HDAC inhibitory properties of VPA or TSA. VPA impairs cell proliferation or survival as indicated by decreased incorporation of [3H]thymidine in F9 and P19 teratocarcinoma cells (Werling et al., 2001), HT-29 colon and MT-450 breast carcinoma cells (Figure 6B). In MT-450 cells, an initial delay in proliferation is followed by the appearance of apoptotic cells after 3–6 days of VPA treatment (Figure 6C).

Fig. 6. VPA induces cell differentiation and apoptosis in carcinoma cell lines and inhibits tumor growth and metastasis formation in the rat. (A) F9 teratocarcinoma cells were treated for 48 h with TSA (30 nM) or VPA (1 mM). The appearance of AP-2 protein as a specific marker of the VPA-induced type of F9 cell differentiation was as described (Werling et al., 2001). One out of two experiments with similar results is shown. (B) Thymidine incorporation into cultures of HT-29 colonic cancer or MT-450 breast carcinoma cells was tested as a parameter for cell proliferation. Cells were cultured for 72 h in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of VPA prior to analysis of [3H]thymidine incorporation. The graph shows the means ± SD from quadruple determinations. Similar results were obtained in two additional independent experiments. (C) The appearance of apoptotic cells in VPA-treated cultures of MT-450 cells was analyzed by staining of cell surface-exposed phosphatidylserine by FITC-conjugated annexin V after exclusion of necrotic cells by means of propidium iodide uptake (lower right quadrant of the graphs). Similar results were obtained in a second experiment. (D) Subcutaneous tumor growth and lung metastasis of MT-450 breast cancer cells were analyzed in rats treated with VPA or saline, respectively. Tumor volume was determined at day 21 (onset of VPA treatment) and day 43 (termination of experiment). Lung metastasis visible from the organ surface was scored. Scores: 0, no metastasis; 1, <50 metastases or all metastatic nodules <2 mm in diameter (lower frames); 2, many metastases >2 mm in diameter (upper right frame); 3, most of the lung’s surface consists of metastatic nodules (upper left frame). Values are means ± SD and significance of differences was calculated by Student t-test. (E) Pictures of two preparations each representative for control or VPA-treated rats are shown. The original height of the frames is 25 mm.

These results prompted us to study the effects of VPA on tumor growth and metastasis in the MT-450 rat breast cancer model. VPA delayed growth of the primary tumors. All rats of the control group showed metastasis and most of the lungs were full with metastases (Figure 6D). Metastasis was also found in VPA-treated rats. However, the size and number of metastases was much smaller compared with NaCl-treated rats (Figure 6E). In a dose finding experiment, our dosage protocol led to high initial serum levels (e.g. 3.6 mM at 1 h after i.p. injection) which rapidly dropped to levels (e.g. 0.25 mM at 4 h after i.p. injection) below those maintained during therapy of epilepsy in humans. In summary, this experiment shows that even though VPA serum levels cannot be maintained at the optimal effective range of >0.5 mM in rodents, VPA treatment nevertheless substantially decreases primary tumor growth and lung metastasis.

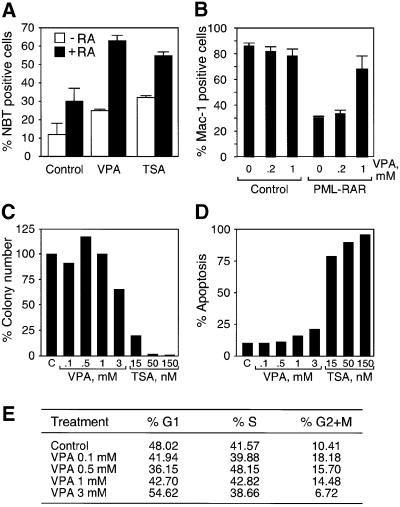

Aberrant recruitment of HDACs by several acute myeloid leukemia (AML) fusion proteins is required for their capacity to block myeloid differentiation (Minucci et al., 2001). Since AML cells are known to respond to treatment with HDAC inhibitors alone, or in synergistic combination with differentiating agents such as retinoids (Ferrara et al., 2001), we analyzed the effect of VPA on the AML Kasumi-1 cell line expressing the t(8;21) translocation product AML1/ETO, and on primary hematopoietic cells expressing the t(15;17) translocation product PML–RAR. Kasumi-1 cells are differentiated by RA as determined by the appearance of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT)-positive cells. VPA induces partial differentiation of Kasumi-1 cells on its own and remarkably enhances the differentiating effect exerted by RA. VPA is as efficient as TSA in inducing Kasumi-1 cell differentiation (Figure 7A). Murine hematopoietic progenitor (lin–) cells in culture show myeloid differentiation, as indicated by expression of the Mac-1 marker upon stimulation with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Differentiation is blocked by retroviral expression of the PML–RAR fusion protein and thus provides a suitable model for AML in primary cells (Grignani et al., 1998; Minucci et al., 2000). VPA (1 mM) almost completely reverts the differentiation block imposed by PML–RAR (Figure 7B). VPA treatment does not affect differentiation of cells which are left uninfected or transduced with the control PINCO vector (Figure 7B). We believe that in our case, in contrast to the effect of HDAC inhibition in PML–RAR-expressing NB4 cells (Lin et al., 1998), VPA suffices to relieve the differentiation block, because G-CSF and GM-CSF also act as differentiation inducers in combination with VPA (Kishi et al., 1998). As a control, the analysis of VPA-treated cells with an erythroid differentiation marker (Ter-119) did not reveal the presence of positive cells (data not shown). To analyze whether VPA might affect normal hematopoiesis by inhibition of cell proliferation or cytotoxicity, lin– cells were subjected to colony assays and assayed for the presence of apoptotic cells as well as cell cycle status (Figure 7C–E). Whereas TSA clearly inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis, VPA does not significantly affect the viability of hematopoietic stem cells even at 3 mM concentration.

Fig. 7. VPA relieves the differentiation block in Kasumi cells and in a murine PML–RAR model. (A) Kasumi-1 cells were treated for 5 days with VPA (1 mM) or TSA (50 nM) in the presence or absence of RA (1 µM). Viable cells were identified by trypan blue dye exclusion and the percentage of differentiated cells was determined by counting NBT-positive cells. Values are means ± SD from three experiments. (B) Lin– cells were isolated and transduced with the indicated vectors (control, PINCO vector encoding GFP alone; PML–RAR, expression of GFP and PML–RAR). GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS and seeded in methylcellulose plates in differentiation medium. Cultures were kept in the absence or presence of VPA (0.2 and 1 mM) for 8–10 days before differentiation was analyzed by expression of the myeloid differentiation marker Mac-1. (C) Lin– cells were plated in semi-solid medium in the presence of cytokines (IL-3, IL-6, SCF, G-CSF and GM-CSF) and the indicated concentrations of VPA or TSA. After 7 days, colonies were counted. (D and E) Lin– cells were grown for 36 h in liquid medium in the presence of cytokines, and then analyzed for the presence of apoptotic cells, or for cell cycle status after propidium iodide staining.

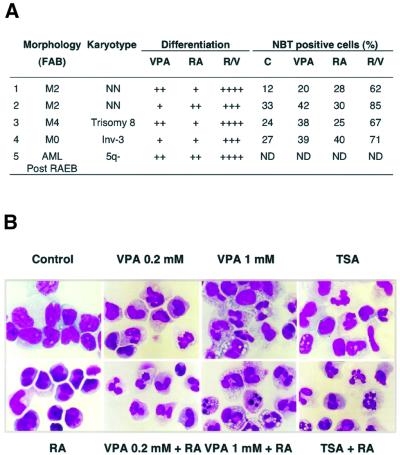

Based on the results obtained in Kasumi-1- and PML–RAR-expressing cells, we tested whether cultured leukemic blasts from five AML patients respond to VPA (Figure 8A). Remarkably, the combined RA/VPA treatment induces the appearance of cells with metamyelocyte- or neutrophil-like morphology and increases the number of positive cells in the NBT dye reduction assay up to 85% (Figure 8A). In all cases, RA/VPA treatment resulted in a comparable, if not higher, level of differentiation than the previously reported RA/TSA treatment (Ferrara et al., 2001). A representative selection of Giemsa-stained blast preparations from the first patient is shown (Figure 8B). Additionally, by morphological observation and by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of propidium iodide-stained nuclei, a higher number of cells apparently undergoing apoptosis was observed in VPA-treated samples than in TSA-treated blasts (Figure 8B and data not shown).

Fig. 8. VPA relieves the differentiation block in blast cells from AML patients. (A) Leukemic blasts of AML patients were cultured for 5 days in the absence or presence of RA and VPA (1 mM). Differentiation was evaluated by morphological criteria (+ 10–20%; ++ 20–40%; +++ 50–80%; ++++ 80–100% more mature metamyelocytes and granulocytes than control cultures) and by determination of the percentage of NBT-positive cells. Classification according to the French–American–British (FAB) nomenclature is given. Patients 1 and 2 represent newly diagnosed AML patients, whereas blasts of patients 3 and 4 were analyzed at relapse after chemotherapy. Patient 5 developed an AML after a refractory anemia with excess of blasts (RAEB). NN indicates a normal karyotype in leukemic blasts. ND, not determined. (B) Wright–Giemsa-stained primary blasts from the bone marrow of a newly diagnosed AML patient (patient 1 of A) were treated in culture for 5 days with RA (1 µM), VPA (0.2 or 1 mM), TSA (240 nM) as single agents or with a combination of RA and either VPA or TSA.

Discussion

This study shows that VPA relieves repression of transcription factors which recruit histone deacetylases. VPA causes hyperacetylation of the N-terminal tails of histones H3 and H4 in vitro and in vivo. It inhibits HDAC activity, most probably by binding to the catalytic center and thereby blocking substrate access. Furthermore, VPA induces differentiation and/or apoptosis of carcinoma cells, PML–RAR-transformed hematopoietic progenitor cells and leukemic blasts from AML patients. VPA also inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in animal experiments. Based on these data and existing clinical experience with VPA, we propose that it might serve as a well-tolerated drug for cancer therapy.

VPA has been used in the treatment of epilepsy for almost 30 years. It exhibits several additional biological activities, in particular beneficial effects in migraine as well as side effects such as teratogenicity and, rarely, liver toxicity, which follow different mechanisms of action (Rettie et al., 1987; Löscher, 1999). The mechanism of teratogenicity is clearly distinct from that of the antiepileptic activity because VPA derivatives exist which are preferentially either teratogenic, such as S-4-yn-VPA, or antiepileptic, such as VPD (Löscher and Nau, 1985; Nau et al., 1991; Radatz et al., 1998). We now show that VPA at concentrations of 0.3–1.0 mM, achieved in patient serum during therapy of epilepsy with a daily dose of 20–30 mg/kg, acts as a potent inhibitor of HDAC activity. For all of the VPA-related compounds tested so far, teratogenicity correlates with HDAC inhibition as determined either directly (this study) or indirectly as derepression of PPARδ (Lampen et al., 1999). This is consistent with the proposition that disruption of proper embryonic development by VPA but not the antiepileptic activity is due to HDAC inhibition. Despite the well-documented teratogenicity of VPA in humans, this adverse effect can only be reproduced properly in specific strains of mice and appears to depend strongly on genetic background (Nau et al., 1991; Faiella et al., 2000). While this manuscript was in preparation, inhibition of HDAC activity by VPA has also been reported by another group (Phiel et al., 2001). Interestingly, this study shows that VPA but not VPD is teratogenic in Xenopus embryos. This teratogenicity could be due to HDAC inhibition because TSA has a strikingly similar effect on the developing Xenopus embryo (Phiel et al., 2001). Although teratogenicity would hardly preclude use of VPA or other HDAC inhibitors in cancer therapy, the present study suggests that other HDAC inhibitors should also be analyzed for teratogenicity under suitable experimental conditions, to test whether HDAC inhibition in the embryo could be linked intrinsically to teratogenicity.

The HDAC inhibitor TSA alters mRNA abundance of up to 2% of the genes expressed in mammalian cells (Van Lint et al., 1996). Considering the toxicity of some HDAC inhibitors (e.g. trapoxin) in mammals, VPA shows surprisingly mild adverse effects in the adult even if serum levels exceed the normal therapeutic range during antiepileptic therapy. The moderate side effects of butyrate and VPA during clinical use suggest that HDAC inhibition per se is not linked to toxicity (Warrell et al., 1998) or obvious suppression of normal hematopoiesis. Furthermore, VPA does not significantly reduce the viability of normal hematopoietic precursor cells in culture (Figure 7C and D). This lack of acute toxicity of VPA may be due to more selective action than some substances initially isolated from microorganisms (Yoshida et al., 1995) which may have been optimized during evolution to kill eukaryotic organisms efficiently, possibly by other mechanisms in addition to HDAC inhibition. Moreover, our data suggest that VPA preferentially acts on corepressor-associated HDACs and inhibits class I more efficiently than class II enzymes HDACs 5 and 6 (Figure 3C–E). This restricted selectivity appears to suffice for induction of differentiation or apoptosis in transformed cells of hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic origin. Finally, the daily doses of VPA required to achieve therapeutic serum levels in patients (20–30 mg/kg) are moderate in comparison with the required doses of other available inhibitors such as butyrate or suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA; Warrell et al., 1998; Butler et al., 2000).

Corepressor-associated HDACs mediate repression by many transcription factors which play key roles in disorders of cell proliferation and differentiation. Inappropriate repression of target genes apparently is responsible for transformation of leukemic cells which harbor translocations leading to the expression of the PML–RAR, PLZF–RAR or AML1/ETO fusion proteins (Grignani et al., 1998; He et al., 1998; Lin et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1998). HDAC inhibitors could potentially be used in differentiation therapy of acute leukemias since combined treatment with RA and TSA can overcome the differentiation block in cells transformed by PML–RAR, PLZF–RAR or AML/ETO in vitro (Grignani et al., 1998; Lin et al., 1998; Lutterbach et al., 1998). Furthermore, primary blasts from the peripheral blood of several patients with primary or relapsed AML were differentiated successfully by treatment with VPA (Figure 8) as well as TSA (Ferrara et al., 2001). This principle also appears applicable to RA-refractory leukemias for which current therapeutic options are very limited (Cote et al., 2000).

Induction of differentiation by HDAC inhibitors in transformed cells does not appear to be limited to hematopoietic cells with aberrant regulation of transcription (Krämer et al., 2001). Our data indicate that other tumorigenic cell types also respond to VPA treatment. In these non-hematopoietic cells, even less is known about transcription factors and their relevant target genes possibly derepressed by HDAC inhibition during re-differentiation or apoptosis. Our study suggests that PPARδ among many other transcription factors is derepressed by HDAC inhibition. Increased PPARδ expression in colon cells caused by loss of the APC tumor suppressor has been associated with the pathogenesis of colonic cancer (He et al., 1999). It is unclear, however, whether changes in the expression levels of target genes by either increased activation or aberrant repression could play a role in tumorigenesis. Only in the latter case might a beneficial effect of HDAC inhibitors be expected. Additional targets may be defined by up-regulation of MHC class I and II and CD40 expression in the presence of HDAC inhibitors (Magner et al., 2000).

VPA is a well-tolerated drug even during long-term treatment. Yet, its HDAC inhibitory activity affects many types of transformed cells, and therefore we propose that it could be useful in cancer therapy. This novel clinical use of VPA may cause mild side effects mostly on the central nervous system. Although this would be acceptable, central nervous activity may be reduced while increasing the HDAC inhibitory activities by appropriate modification of the VPA molecule, as demonstrated by S-4-yn-VPA or derivatives with longer side chains (Lampen et al., 1999). In conclusion, we show that the established antiepileptic drug VPA inhibits HDACs, which may render VPA and related compounds useful for the modulation of gene activity during re-differentiation therapy of malignant diseases. We hope that results from experimental therapy will provide proof of principle for the effectiveness of VPA as an HDAC inhibitory drug in the near future.

Materials and methods

Assay for PPARδ transcriptional activity

The CHO reporter cell line expresses a fusion protein of the PPARδ ligand-binding domain with the N-terminal and DNA-binding domains of GR together with a GR-dependent MMTV long terminal repeat promoter (Göttlicher et al., 1992; Lampen et al., 1999). Similar cells expressing the full-length GR or a homologous reporter cell line for PPARα activation served as negative controls for specificity. PPARδ hybrid receptor-expressing cells were seeded at 20% confluence into 24-well culture dishes and treated in duplicates for 40 h with cPGI2 (5 µM, Biomol), HDAC inhibitors or VPA.

Transcriptional repression assay

Transcriptional repression was measured after transient transfection of HeLa cells with a Gal4 UAS TK luciferase reporter construct of high constitutive activity, as described (Heinzel et al., 1997). The high basal activity was repressed by co-expression of Gal4 fusion proteins with N-CoR or the ligand-binding domains of TR or PPARδ (Kliewer et al., 1994). HDAC inhibitors, VPA or receptor ligands were added 24 h after transfection and reporter gene activity was determined after an additional 24 h. Transcriptional repression was calculated as luciferase activity relative to the baseline of cells expressing the Gal4 DNA-binding domain.

Determination of histone H3 and H4 acetylation status

Accumulation of hyperacetylated histones H3 and H4 was analyzed in cell lysates by western blotting using antibodies directed against acetylated histones H3 and H4 (Upstate Biotechnology). Whole-cell lysates were prepared in denaturing SDS sample buffer and separated on 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gels.

HDAC assay

HDAC activity was measured either in immune precipitation supernatants or in immune precipitates with antibodies directed against N-CoR, mSin3 or HDAC2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using 3H-labeled hyperacetylated histone substrate as described (Heinzel et al., 1997). The HDAC inhibitor TSA, VPA or related carboxylic acids were added 15 min prior to addition of substrate and the reaction was continued for 2 h at 37°C.

VPA binding assay

Whole-cell extracts from HEK293T (250 µl) were incubated with antibodies and protein A/G–agarose for 2 h at 4°C. Precipitates were washed four times with NETN (0.05) buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40) and resuspended in 60 µl. If appropriate, samples were pre-incubated for 15 min with TSA (100 nM) prior to addition of 2 µCi of 3H-labeled VPA (55 Ci/mmol, Movarek Biochemicals). After incubation for 1 h at 20°C, immunoprecipitates were transferred to glass fiber filters and washed four times with 1 ml of cold NETN (0.05) buffer. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

PML–RAR-transformed hematopoietic stem cells

Transduction of murine hematopoietic progenitors was performed as described (Minucci et al., 2000). Murine hematopoietic progenitors were purified from the bone marrow of 129 mice based on the absence of lineage differentiation markers (lin–). Lin– cells were grown for 48 h in the presence of interleukin (IL)-3 (20 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml) and stem cell factor (SCF; 100 ng/ml), and then attached to non-tissue culture-treated plates coated with Retronectin (Takara-Shuzo). Cells were then transduced with the control retroviral vector PINCO, or PINCO–PML– RAR (Minucci et al., 2000). After 60 h, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS, and seeded in methylcellulose plates supplemented as above, plus G-CSF (60 ng/ml) and GM-CSF (20 ng/ml). Where indicated, sodium valproate (VPA, 0.2 or 1 mM) was added to the medium. After 8–10 days, cells were analyzed for the presence of the myeloid differentiation marker Mac-1 by FACS.

Differentiation of primary blasts from AML patients

Primary blast from bone marrow and/or peripheral blood of AML patients were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), treated with the HDAC inhibitors TSA or VPA, starting 1 h before the addition of RA as previously described (Ferrara et al., 2001). Cell differentiation and apoptosis were evaluated after 5 days of treatment by morphological examination of Wright–Giemsa-stained cytospins, NBT dye reduction assay and cell cycle analysis of cells stained with propidium iodide, as described (Ferrara et al., 2001).

Cellular differentiation assays

Indications for differentiation or apoptosis of tumorigenic cell lines were obtained by analyzing cell proliferation rate, cell morphology and expression of differentiation markers. Reduction of proliferation was shown in F9 teratocarcinoma, estrogen-independent MT-450 breast cancer and HT-29 colonic carcinoma cells. Cells were cultured for 72 h in the absence or presence of VPA prior to a 1 h [3H]thymidine (37 kBq) labeling period and determination of [3H]thymidine incorporation into DNA. Apoptotic cells were detected by flow cytometric analysis after staining of cells with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated annexin V (Becton Dickinson). The appearance of nuclear AP-2 protein as a specific marker of F9 cell differentiation was detected by western blot analysis as described (Werling et al., 2001).

Animal experiments

MT-450 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/10% FCS. Cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to subcutaneous injection of 5 × 105 cells per rat in 0.1 ml of PBS. Rats were left to grow primary tumors for 21 days. Groups of eight rats each were then treated daily by i.p. injection with either sodium valproate (155 mM) or saline. Each dosing was 1.25 mmol VPA/kg body weight or an equivalent volume of isotonic saline. Two doses per day were applied during 5 days of the week and one dose each during 2 days of the week.

Chemicals

VPA was obtained from Sigma/Aldrich. VPD was purchased from Lancaster Synthesis. R- and S-4-yn-VPA were obtained from Chemcon. Stereoisomers of EHXA were separated according to Werling et al., 2001,Hauck et al., 1990).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for technical assistance by M.Litfin, A.Careddu, A.Gobbi, S.Monestroli and S.Ronzoni. We thank A.Maurer and W.Wels for helpful discussions. P.Z. was supported by a fellowship from the Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe and M.G. by DFG grants GO-473/1,2. S.M. is funded by FIRC, and P.G.P. by AIRC and EEC.

References

- Alland L., Muhle,R., Hou,H.,Jr, Potes,J., Chin,L., Schreiber-Agus,N. and DePinho,R.A. (1997) Role for N-CoR and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature, 387, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler L.M. et al. (2000) Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, suppresses the growth of prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res., 60, 5165–5170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.D. and Evans,R.M. (1995) A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature, 377, 454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote S., Zhou,D., Bianchini,A., Nervi,C., Gallagher,R.E. and Miller,W.H.,Jr (2000) Altered ligand binding and transcriptional regulation by mutations in the PML/RARα ligand-binding domain arising in retinoic acid-resistant patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood, 96, 3200–3208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Thé H., Vivanco-Ruiz,M.M., Tiollais,P., Stunnenberg,H. and Dejean,A. (1990) Identification of a retinoic acid responsive element in the retinoic acid receptor β gene. Nature, 343, 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhordain P., Lin,R.J., Quief,S., Lantoine,D., Kerckaert,J.P., Evans,R.M. and Albagli,O. (1998) The LAZ3(BCL-6) oncoprotein recruits a SMRT/mSIN3A/histone deacetylase containing complex to mediate transcriptional repression. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4645–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLiberti J.H., Farndon,P.A., Dennis,N.R. and Curry,C.J. (1984) The fetal valproate syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet., 19, 473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faiella A., Wernig,M., Consalez,G.G., Hostick,U., Hofmann,C., Hustert,E., Boncinelli,E., Balling,R. and Nadeau,J.H. (2000) A mouse model for valproate teratogenicity: parental effects, homeotic transformations and altered HOX expression. Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara F.F. et al. (2001) Histone deacetylase-targeted treatment restores retinoic acid signaling and differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res., 61, 2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnin M.S., Donigian,J.R., Cohen,A., Richon,V.M., Rifkind,R.A., Marks,P.A., Breslow,R. and Pavletich,N.P. (1999) Structures of a histone deacetylase homologue bound to the TSA and SAHA inhibitors. Nature, 401, 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmetti V., Zhang,J., Fanelli,M., Minucci,S., Pelicci,P.G. and Lazar,M.A. (1998) Aberrant recruitment of the nuclear receptor corepressor–histone deacetylase complex by the acute myeloid leukemia fusion partner ETO. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 7185–7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C.K. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (2000) The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev., 14, 121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttlicher M., Widmark,E., Li,Q. and Gustafsson,J.Å. (1992) Fatty acids activate a chimera of the clofibric acid-activated receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 4653–4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grignani F. et al. (1998) Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-α recruit HDAC in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature, 391, 815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidez F., Ivins,S., Zhu,J., Söderström,M., Waxman,S. and Zelent,A. (1998) Reduced retinoic acid-sensitivities of nuclear receptor corepressor binding to PML- and PLZF-RARα underlie molecular pathogenesis and treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood, 91, 2634–2642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck R.S., Wegner,C., Blumtritt,P., Fuhrhop,J.H. and Nau,H. (1990) Asymmetric synthesis and teratogenic activity of (R)- and (S)-2-ethylhexanoic acid, a metabolite of the plasticizer di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. Life Sci., 46, 513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.Z., Guidez,F., Tribioli,C., Peruzzi,D., Ruthardt,M., Zelent,A. and Pandolfi,P.P. (1998) Distinct interactions of PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα with co-repressors determine differential responses to RA in APL. Nature Genet., 18, 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T.C., Chan,T.A., Vogelstein,B. and Kinzler,K.W. (1999) PPARδ is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell, 99, 335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel T. et al. (1997) A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature, 387, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie S. and Suga,T. (1985) Enhancement of peroxisomal β-oxidation in the liver of rats and mice treated with valproic acid. Biochem. Pharmacol., 34, 1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörlein A.J. et al. (1995) Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature, 377, 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten S., Desvergne,B. and Wahli,W. (2000) Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature, 405, 421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi K. et al. (1998) Hematopoietic cytokine-dependent differentiation to eosinophils and neutrophils in a newly established acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line with t(15;17). Exp. Hematol., 26, 135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer S.A., Forman,B.M., Blumberg,B., Ong,E.S., Borgmeyer,U., Mangelsdorf,D.J., Umesono,K. and Evans,R.M. (1994) Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 7355–7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer O.H., Göttlicher,M. and Heinzel,T. (2001) Histone deacetylase as a therapeutic target. Trends Endocrinol. Metab., 12, 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laherty C.D., Yang,W.M., Sun,J.M., Davie,J.R., Seto,E. and Eisenman,R.N. (1997) Histone deacetylases associated with the mSin3 corepressor mediate mad transcriptional repression. Cell, 89, 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampen A., Siehler,S., Ellerbeck,U., Göttlicher,M. and Nau,H. (1999) New molecular bioassays for the estimation of the teratogenic potency of valproic acid derivatives in vitro: activation of the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor (PPARδ). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 160, 238–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R.J., Nagy,L., Inoue,S., Shao,W., Miller,W.H.,Jr and Evans,R.M. (1998) Role of the histone deacetylase complex in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature, 391, 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W. (1999) Valproate: a reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic properties and mechanisms of action. Prog. Neurobiol., 58, 31–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W. and Nau,H. (1985) Pharmacological evaluation of various metabolites and analogues of valproic acid. Anticonvulsant and toxic potencies in mice. Neuropharmacology, 24, 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutterbach B. et al. (1998) ETO, a target of t(8;21) in acute leukemia, interacts with the N-CoR and mSin3 corepressors. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 7176–7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherey A.C., Gregoire,S., Tainturier,G. and Lhuguenot,J.C. (1992) Enantioselectivity in the induction of peroxisome proliferation by 2-ethylhexanoic acid. Chirality, 4, 478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner W.J., Kazim,A.L., Stewart,C., Romano,M.A., Catalano,G., Grande,C., Keiser,N., Santaniello,F. and Tomasi,T.B. (2000) Activation of MHC class I, II and CD40 gene expression by HDAC inhibitors. J. Immunol., 165, 7017–7024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P.A., Richon,V.M. and Rifkind,R.A. (2000) Histone deacetylase inhibitors: inducers of differentiation or apoptosis of transformed cells. J. Natl Cancer Inst., 92, 1210–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minucci S. et al. (2000) Oligomerization of RAR and AML1 transcription factors as a novel mechanism of oncogenic activation. Mol. Cell, 5, 811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minucci S., Nervi,C., Coco,F.L. and Pelicci,P.G. (2001) Histone deacetylases: a common molecular target for differentiation treatment of acute myeloid leukemias? Oncogene, 20, 3110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L., Kao,H.Y., Chakravarti,D., Lin,R.J., Hassig,C.A., Ayer,D.E., Schreiber,S.L. and Evans,R.M. (1997) Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A and histone deacetylase. Cell, 89, 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau H., Hauck,R.S. and Ehlers,K. (1991) Valproic acid-induced neural tube defects in mouse and human: aspects of chirality, alternative drug development, pharmacokinetics and possible mechanisms. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 69, 310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark H.L. and Young,C.W. (1995) Butyrate and phenylacetate as differentiating agents: practical problems and opportunities. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl., 22, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiel C.J., Zhang,F., Huang,E.Y., Guenther,M.G., Lazar,M.A. and Klein,P.S. (2001) Histone deacetylase is a direct target of valproic acid, a potent anticonvulsant, mood stabilizer and teratogen. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 36734–36741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radatz M., Ehlers,K., Yagen,B., Bialer,M. and Nau,H. (1998) Valnoctamide, valpromide and valnoctic acid are much less teratogenic in mice than valproic acid. Epilepsy Res., 30, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettie A.E., Rettenmeier,A.W., Howald,W.N. and Baillie,T.A. (1987) Cytochrome P-450-catalyzed formation of δ 4-VPA, a toxic metabolite of valproic acid. Science, 235, 890–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl B.D. and Allis,C.D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature, 403, 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lint C., Emiliani,S. and Verdin,E. (1996) The expression of a small fraction of cellular genes is changed in response to histone hyperacetylation. Gene Expr., 5, 245–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Hoshino,T., Redner,R.L., Kajigaya,S. and Liu,J.M. (1998) ETO, fusion partner in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia, represses transcription by interaction with the human N-CoR/mSin3/HDAC1 complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 10860–10865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrell R.P. Jr, He,L.Z., Richon,V., Calleja,E. and Pandolfi,P.P. (1998) Therapeutic targeting of transcription in acute promyelocytic leukemia by use of an inhibitor of histone deacetylase. J. Natl Cancer Inst., 90, 1621–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werling U., Siehler,S., Litfin,M., Nau,H. and Göttlicher,M. (2001) Induction of differentiation in F9 cells and activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ by valproic acid and its teratogenic derivatives. Mol. Pharmacol., 59, 1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Glass,C.K. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (1999) Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 9, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Horinouchi,S. and Beppu,T. (1995) Trichostatin A and trapoxin: novel chemical probes for the role of histone acetylation in chromatin structure and function. BioEssays, 17, 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]