Abstract

Artificial light at night (ALAN) negatively affects a broad range of animal species, with severe implications for conservation policy development and strategic planning globally. Birds are one of the most widely used ecological indicator groups in monitoring environmental changes. However, most studies examining the effects of ALAN are focused on diurnal bird species. It would therefore be necessary to study these effects in more detail on species with at least crepuscular or nocturnal activity, since they may be more vulnerable. We investigated the effects of illumination on the nest box occupancy of the western barn owl (Tyto alba; hereafter barn owl) and tawny owl (Strix aluco) in illuminated vs. unilluminated church towers and the reproductive output in nest boxes in these towers by comparing the numbers of eggs and chicks fledged. We found reduced breeding presence in illuminated towers in both species but no difference in reproduction parameters for either of the species. Our results underscore that light pollution has a negative consequence on the nest box occupancy of barn owls and tawny owls due to reducing breeding site suitability. This raises the threat that artificial light at night may hinder the conservation of such nocturnal bird species whose reproduction may be increasingly connected to human settlements in the future.

Keywords: ALAN, Breeding site preference, Light pollution, Barn owl, Tawny owl, Reproduction

Introduction

Light pollution and artificial light at night (ALAN) exerts major effects on a broad range of animal species1,2, affecting circadian rhythms3–6, hormone levels7,8, sleeping9–11, migration12, feeding behaviour13,14, predation pressure15,16, and its effects also appear at the community level15,17–19. Nocturnal species could be more vulnerable than diurnal ones2. Nocturnal vertebrates could show reduced activity when exposed to ALAN20. The impact of ALAN has also been demonstrated on small mammal populations21–23, which is particularly important given that this group constitutes a key prey source for owls, especially for the two species examined in our study. ALAN can either reduce21,22 or increase23 foraging behavior and activity levels in small mammals, which may influence their predators. In bats, ALAN has been shown to cause a range of effects, from altering foraging activity to roost abandonment, and may also indirectly negatively affect juvenile growth rates24.

Despite the continuous growth of research on ALAN, there are still significant gaps in our knowledge25,26. One of the gaps is that, in general, we know little about the effects on nocturnal owls26. Studies of crepuscular and nocturnal birds primarily focus on the feeding behaviour. There are numerous examples of nightjars27–29 and owls30,31 hunting around artificial nocturnal light sources, such as the glow of street lamps or illuminated buildings. At first, it might seem that ALAN could positively impact insectivorous birds by promoting the aggregation of their food sources, however this is not sufficiently supported. For example, Morelli et al.32 found a negative relationship between ALAN and insectivorous birds. ALAN can affect not only the foraging behavior of nocturnal species but also the composition of the diet33. In the case of the nightjar, artificial light at night (ALAN) may increase nocturnal flight activity34. Beyond all this, ALAN has a conservation interest, as it can directly contribute to the decline in populations of nocturnal avian species35. With regard to reproduction, it is known that ALAN can accelerate gonadal development in birds36 and it could influence the breeding ecology and biology of birds37–39. Some previous studies have revealed a negative correlation between owl occurrence and ALAN in urban areas40,41. However, our understanding of the effects of artificial light at night on the reproduction of nocturnal birds such as owls remains limited.

In Europe, the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) and the Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) are common species. The Barn Owl is strongly associated with human settlements, with its nesting primarily occurring in human-made structures42. Despite being primarily a woodland species, the urbanization of the Tawny Owl is well-documented43–45. As both species can nest in human settlements, where light pollution is most significant, they are good subjects for studying the effects of ALAN on occupancy and breeding patterns of nocturnal birds.

The aim of our research was to investigate the potential effect of building illumination on nest box occupancy and reproductive success of both species. We hypothesized that ALAN decreases the box occupancy in both species, as it likely represents a disturbance for these nocturnal birds. Previous studies have shown negative correlation between tawny owl and illuminated areas26,41. Consistent with these findings, our hypothesis was that the Tawny Owl is likely to be more severely affected, as it is originally a woodland species that is less habituated to light pollution compared to the Barn Owl, which is already associated with human-made structures. We also predicted that breedings exposed to ALAN will exhibit lower reproductive success.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was carried out in Baranya County (4430 km2; 46°04′ N, 18°14′ E), located in southwestern Hungary. The rural county is characterized by small settlements surrounded by natural habitats and agricultural lands, rather than larger cities. In 96% of the 301 settlements, at least one church tower or chapel can be found. A total of 163 exterior nest boxes were placed in different buildings, of which 95% were church or chapel towers (the remaining 5% was placed in farm buildings or in the attics of large buildings), progressively from 1988 to 2019. The nest box dimensions were 100 × 50 × 50 cm in general but could differ according to the availability of space in the towers. Each box was placed behind the tower’s window with a 15 cm*15 cm hole as the entrance (Fig. 1). The artificial nest boxes were installed across 150 different settlements46. For this study, we used data only from nest boxes placed in church towers.

Fig. 1.

A An illuminated church tower currently occupied by barn owls. B Location of the nest box positioned behind the church window. The birds can only access the nest box, as it is closed off toward the interior of the building.

Data collection

Breeding data was gathered by volunteers (50–60 people) of the Baranya County Group of BirdLife Hungary based on a strict protocol46. We recorded the illumination state of each church along with the year of the installation of the illumination. We considered a tower unilluminated if it was not illuminated at all during the year or if it was illuminated only twice a year (i.e., at Christmas and Easter). In the other cases the towers were connected to the public lighting system, that means these buildings were illuminated every night. These were considered illuminated. As it was not possible to measure the light intensity of the towers’ illumination, we considered only their presence or absence in the following analysis. During the illumination of individual buildings, the property maintainers applied various methods and types of lighting. However, the nest boxes were always placed behind windows that had only a single entrance hole for the birds to fly in, and the boxes were closed on the side facing the interior of the building, preventing owls from entering the building itself. Since the boxes are connected to the outside environment only through the entrance hole, it can be stated that there is no direct lighting inside the box where breeding takes place.

For nest box occupancy, we used a presence/absence variable, and nest box was considered occupied if a clutch was found in it. For the analyses, we used the following breeding variables: clutch size (i.e., the number of eggs laid), fledgling number, and laying date (compared to the yearly median). In barn owls, second broods are known to be common in years with high food availability42,47–49, whereas in tawny owls this breeding behavior is very rare50. Importantly, only the first broods were used from a given nesting location. Furthermore, we excluded the cases of the respective variables where the laying date was uncertain, the clutch was not completed (due to interruption, e.g., predation, nest desertion), or the number of fledglings was uncertain (due to predation on owlets or nest abandonment by the parents). Accordingly, for clutch size and fledging number, we use data where the value was larger than 0.

We aimed to investigate if there were differences in the presence of barn owl or tawny owl breeding in the mirror of the illumination state of the church towers. The towers were only considered from the year when the given owl species first bred there. This is important because it’s possible that, after placing the boxes, there may be no owls in the area for years. (Our unpublished results suggested that the number of years from the date of nest box establishment to the date of first occupancy was not related to the illumination status of the tower.) According to this, for the presence/absence we had 952/1207, and 249/359 cases in the barn owl (1988–2019) and the tawny owl (1992–2019), from 122 locations in sum (meaning 119 and 45 locations for the barn owl and the tawny owl, respectively, with 42 overlapping locations between the two species).

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (Pest County Government Office, Department of Environmental Protection and Nature Conservation, Permit Nr. PE-KTF/97-13/2017).

Statistical methods

For analysing nest box occupancy, we applied generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) with binomial error distribution, logit link function, and Satterthwaite estimation for degrees of freedom. The presence/absence was the binary response variable, and the illumination state was the fixed factor. We also controlled for location by entering location identity as a random effect to account for potential location-specific variations (such as microhabitat or prey density) without confounding the effect of illumination, because location was not 1:1 with the nest box, as multiple nest boxes/towers were used across different years, hence locations were represented multiple times.

We used Chi-square tests to assess if there was a difference between the two species with respect to the association of presence or absence in unilluminated and also illuminated towers.

Additionally, we also conducted Wilcoxon matched pair tests in order to evaluate the potential changes with respect to the scores for presence in towers of which illumination states were altered since the owl’s first presence there. Hence, we calculated average presence scores for the relevant time periods in each tower (i.e., Nyears with presence/Ntotal years) separately for the illumination states. Typically, the direction of the status change was that the towers went from unilluminated to illuminated (with the exception of one case where it was subsequently darkened again; this data series was not used here). In addition, only sites were included in the analysis where the ratio between illuminated and unilluminated years was a maximum of 3:1 or a minimum of 1:3. Accordingly, our samples consisted of 21 and 7 paired observations in the barn owl and the tawny owl, respectively, and the relevant locations were represented by one data point per group.

We investigated if reproduction success in the first broods was associated with the illumination state (two levels: 0 = not illuminated, 1 = illuminated) of the towers. In order to do this, we conducted linear mixed models (LMMs) with normal error, identity link function, and Satterthwaite estimation for degrees of freedom. We used one of the reproductive variables (clutch size, fledging number) as a response variable, the illumination status of the church towers, and the laying date as fixed effects. Additionally, we controlled for year and location using these as random effects. We entered laying date as a fixed effect to control for the potential effects of the date on reproduction output. For fixed effects, we applied backward stepwise model simplification51. (However, with regard to the illumination state, we kept qualitatively the same results if we did not consider the laying date.) According to QQ-plots, model residuals were normally distributed.

We analyzed the data from the two owl species separately in all cases.

The analyses were performed in R 4.2.152. For the GLMMs and LMMs, we applied the glmer() and the lmer() functions, respectively, from the ’lme4’ package53, and the Anova () function from the ‘car’ package54. We obtained the conditional and marginal R2 values using the r.squaredGLMM() function from ’MuMin’ package55. The Chi-square tests were conducted using the chisq.test() function in R, the Wilcoxon matched pair tests were conducted using the wilcox,test() function.

The primary data supporting the results of this study are available at the Figshare digital repository56.

Results

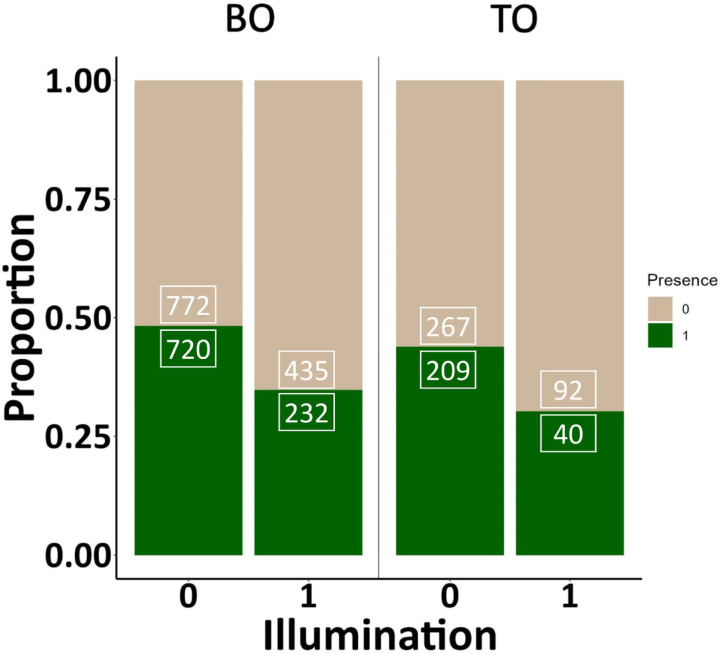

The GLMMs revealed in both species that the nest box occupancy was significantly higher in church towers with no illumination (see details on estimate(SE), Wald χ2, significance, conditional and marginal R2 in Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Association between presence of breeding barn owl and tawny owl in connection with the unilluminated versus illuminated state of church towers.

| Species | Explanatory variable | Estimate(SE) | Wald χ2(df) | R2m | R2c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barn owl | (Intercept) | 0.04(0.13) | 0.08(1) | |||

| Illumination | − 0.74(0.17) | 18.33(1) | *** | 0.03 | 0.31 | |

| Tawny owl | (Intercept) | − 0.09(0.22) | 0.16(1) | |||

| Illumination | − 0.86(0.35) | 6.14(1) | * | 0.03 | 0.32 |

According to the results, the presence was negatively associated with the illuminated state of the towers in both species. We provided marginal R2 (R2m) and conditional R2 (R2c) for fixed effects retained in the final model after backward stepwise model simplification.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. We applied generalized linear models with binomial error distribution and logit link function.

Fig. 2.

Proportions of the presence (drak green) and absence (light brown) of the barn owl (BO) and tawny owl (TO) in unilluminated (0) and illuminated (1) church towers. The numbers in the boxes refer to the sample size of the respective group.

According to the Chi-square tests, the two species showed no differences from each other with respect to presence/absence (unilluminated towers: χ2 = 2.57, df = 1, P = 0.10; illuminated towers: χ2 = 0.80, df = 1, P = 0.37).

The Wilcoxon matched pair tests revealed marginal effects on the average scores of presence (barn owl: W = 170, P = 0.060; tawny owl: W = 25, P = 0.078), suggesting a decreasing trend in presence in formerly unilluminated towers that have become illuminated. The median difference between ’pre-treatment’ and ’post-treatment’ scores was -0.29 and -0.53 for the barn owl and the tawny owl, respectively.

The investigated reproduction parameters were not associated with the illumination state of the towers in either species, and the laying was the only predictor that was slightly correlated with clutch size and fledging number (see details on estimate(SE), Wald χ2, significance, conditional and marginal R2 in Table 2, and the descriptive statistics of reproductive variables in Table 3).

Table 2.

Relationships of reproductive parameters with the illumination state of church towers in the barn owl and tawny owl.

| Species | Response variable | Explanatory variable | Estimate(SE) | Wald χ2(df) | R2m | R2c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barn owl | Clutch size | (Intercept) | 6.80(0.13) | 2886.67(1) | *** | ||

| Laying date | 0.01(0.00) | 16.94(1) | *** | 0.02 | 0.21 | ||

| Illumination | − 0.18(0.14) | 1.64(1) | |||||

| Fledgling number | (Intercept) | 4.72(0.15) | 951.59(1) | *** | |||

| Laying date | 0.01(0.00) | 15.82(1) | *** | 0.02 | 0.23 | ||

| Illumination | − 0.01(0.15) | 0.01(1) | |||||

| Tawny owl | Clutch size | (Intercept) | 4.40(0.16) | 780.15(1) | *** | ||

| Laying date | − 0.01(0.01) | 2.52(1) | |||||

| Illumination | − 0.28(0.29) | 0.34(1) | |||||

| Tawny owl | Fledgling number | (Intercept) | 3.16(0.14) | 542.21(1) | *** | ||

| Laying date | − 0.01(0.01) | 3.99(1) | * | 0.02 | 0.29 | ||

| Illumination | 0.08(0.26) | 0.08(1) |

We provided marginal R2 (R2m) and conditional R2 (R2c) for fixed effects retained in the final model after backward stepwise model simplification.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Terms retained in the final model are highlighted in bold.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of reproductive variables between two groups of the illumination state of church towers in the barn owl and tawny owl.

| Species | Illumination state | Reproduction variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barn owl | Illuminated | Clutch size | 6.94 | 1.47 |

| Fledging number | 4.86 | 1.60 | ||

| Not illuminated | Clutch size | 6.79 | 1.46 | |

| Fledging number | 4.88 | 1.61 | ||

| Tawny owl | Illuminated | Clutch size | 4.43 | 1.07 |

| Fledging number | 3.22 | 1.17 | ||

| Not illuminated | Clutch size | 3.89 | 1.02 | |

| Fledging number | 3.07 | 1.04 |

Discussion

Light pollution poses a serious threat to numerous species1,2,57 and our study indicates that also owls are negatively affected by ALAN. Our results revealed that nestbox occupancy probability was higher in unilluminated than illuminated towers, as a significantly lower number of breedings occurred in illuminated towers compared to unilluminated ones. However, illumination did not reduce the reproductive output (measured in clutch size and fledgling number) in either species.

Both bats and owls are nocturnal animals and often prefer the same buildings as resting and breeding sites58,59. Based on this, it can be assumed that the illumination of these buildings may have a similar impact on both groups. For bats, lighting of churches is known to directly lead to the abandonment of these buildings as roost sites60,61. In our study, in the case of towers previously unlit but later illuminated, we observed a marginal, not significant effect of illumination on the reduction in nesting events following the lighting. The fact that the abandonment of buildings as nesting sites due to lighting has less of an impact on these two owl species than on bats may stem from the possibility that these species are perhaps less sensitive to the quality of nesting sites than bats. It is known that the barn owl originally nested in hollow trees, but with their disappearance, it adapted to human-made structures. Today, it nests not only in churches and farm buildings but also in the attics of family houses, water towers, and even in loess cliffs42,62. The Tawny Owl, on the other hand, can nest on the ground, in abandoned twig nests, or even in haystacks, in addition to buildings and natural tree cavities63. Our hypothesis was that the effects of ALAN would impact the tawny owl more strongly than the barn owl, but we did not find such a difference. This may be explained by the fact that, although the tawny owl is originally a woodland species, it shows a high degree of urbanisation43–45, which likely enables it to tolerate light-polluted areas to some extent. However other studies26,41 demonstrated a negative association between the presence of tawny owls and ALAN in urban environments. One possible explanation is that the tawny owl shows a tendency toward urbanization but avoids areas with excessive light pollution. Illumination may affect owls not only directly, but also indirectly by influencing prey availability. Several studies have shown that ALAN can have an effect on small mammals21–23, for example by reducing their activity or foraging behavior21,22.

For crepuscular and nocturnal birds, we have little knowledge about the effects of ALAN on their breeding biology. In the case of the common nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) and common poorwill (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii), it is likely that the birds avoid areas polluted by ALAN due to the higher nest predation risk associated with it64. Our knowledge of the effects of ALAN on bird breeding biology is primarily related to diurnal bird species. These effects can be either positive37 or negative39. ALAN can influence the begging time of nestlings37, extend the time that parents spend bringing food37,65, advance the laying date38, and reduce the weight gain of the nestlings39. In our study, we did not find any evidence that ALAN affected the breeding success of the two owl species. The owls do not nest freely in any part of the building but rather in enclosed artificial nest boxes placed behind the windows. Since these boxes are closed (open only through the entry hole), light pollution likely has a reduced impact inside, exposing the eggs or chicks to only lower-intensity light stress. It is also possible that illumination may have different, potentially even positive, effects on owls. For example, by facilitating hunting which could explain why we do not observe a reduction in reproductive success. However, the fact that the building itself is illuminated may still disturb the birds in their choice of nesting site, even though the box remains quite dark. Supporting this, data on the presence-absence of nesting show a significantly negative effect when the building is illuminated.

We are aware of the limitations of our study: although we did not observe a significant effect on clutch size or fledging number, the effects of ALAN may manifest, for example, in the form of altered immune function66 or reduced body mass39.

In several regions, barn owl populations have been displaced from churches primarily due to renovations67,68, yet in Hungary, the majority of known breeding sites are still found in church towers46,62,68. Given the declining population trends of the barn owl in multiple regions42,69,70, church illumination adds an additional negative impact on this already vulnerable species.

Our results elucidate the broader ecological impacts of light pollution on nocturnal birds, contributing to our understanding of how ALAN influences life history traits and conservation outcomes for these species.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all members of the MME/BirdLife Hungary Baranya County Group and László Bank for their enormous efforts in the field work. Ida Horváth helped in creating the data base, Kata Fetzer, Diana Kovács and Csaba Őri in collecting data on church illumination. We are grateful to Ákos Klein for providing us with the photo used in Figure 1A. The research was funded by the Hungarian Nature Research Society (LGHTPLLTN/2017) and EFOP-3.6.2-16-2017-00014. This paper was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (BO/00213/25/8).

Author contributions

E.M., R.M. and G.H. gathered the field data, E.M., M.L., Z.S. and R.M wrote the main manuscript, M.L. and Z.S. prepared the figures, all authors participated in creating the database and reviewed the ms.

Data availability

The primary data supporting the results of this study are available at the Figshare digital repository10.6084/m9.figshare.27930849.v1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Miklós Laczi, Email: miklos.laczi@ttk.elte.hu.

Zoltán Schneider, Email: schneider.zoltan.bp@gmail.com.

Róbert Mátics, Email: bobmatix@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Falcón, J. et al. Exposure to artificial light at night and the consequences for flora, fauna, and ecosystems. Front. Neurosci.14, 602796. 10.3389/fnins.2020.602796 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders, D., Frago, E., Kehoe, R., Patterson, C. & Gaston, K. J. A meta-analysis of biological impacts of artificial light at night. Nat. Ecol. Evol.5, 74–81. 10.1038/s41559-020-01322-x (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brüning, A., Hölker, F., Franke, S., Preuer, T. & Kloas, W. Spotlight on fish: Light pollution affects circadian rhythms of European perch but does not cause stress. Sci. Tot. Environ.511, 516–522. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.12.094 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang, J. et al. The effects of artificial light at night on Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus): Behavioral rhythm disruption, melatonin suppression and intestinal microbiota alterations. Ecol. Indic.108, 105702. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105702 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulgar, J. et al. Endogenous cycles, activity patterns and energy expenditure of an intertidal fish is modified by artificial light pollution at night (ALAN). Environ. Pollut.244, 361–366. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.063 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amichai, E. & Kronfeld-Schor, N. Artificial light at night promotes activity throughout the night in nesting common swifts (Apus apus). Sci. Rep.9, 11052. 10.1038/s41598-019-47544-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moaraf, S. et al. Artificial light at night affects brain plasticity and melatonin in birds. Neurosci. Lett.716, 134639. 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134639 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupprat, F., Kloas, W., Krüger, A., Schmalsch, C. & Hölker, F. Misbalance of thyroid hormones after two weeks of exposure to artificial light at night in Eurasian perch Perca fluviatilis. Conserv. Physiol.9, coaa124. 10.1093/conphys/coaa124 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun, J., Raap, T., Pinxten, R. & Eens, M. Artificial light at night affects sleep behaviour differently in two closely related songbird species. Environ. Pollut.231, 882–889. 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.098 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raap, T., Pinxten, R. & Eens, M. Artificial light at night disrupts sleep in female great tits (Parus major) during the nestling period, and is followed by a sleep rebound. Environ. Pollut.215, 125–134. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.04.100 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raap, T., Sun, J., Pinxten, R. & Eens, M. Disruptive effects of light pollution on sleep in free-living birds: Season and/or light intensity-dependent?. Behav. Processes144, 13–19 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthreux, S. A. & Belser, C. G. Effects of artificial night lighting on migrating birds. In Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting (eds Rich, C. & Longcore, T.) 67–93 (Island Press, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lebbin, D. J., Harvey, M. G., Lenz, T. C., Andersen, M. J. & Ellis, J. M. Nocturnal migrants foraging at night by artificial light. Wilson J. Ornith.119, 506–508. 10.1676/06-139.1 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos, C. D. et al. Effects of artificial illumination on the nocturnal foraging of waders. Acta Oecol.36, 166–172. 10.1016/j.actao.2009.11.008 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mcmunn, M. S. et al. Artificial light increases local predator abundance, predation rates, and herbivory. Environ. Entomol.48, 1331–1339. 10.1093/ee/nvz103 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuñez, J. D. et al. Artificial light at night may increase the predation pressure in a salt marsh keystone species. Mar. Environ. Res.167, 105285. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2021.105285 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens, A. C. S. & Lewis, S. M. The impact of artificial light at night on nocturnal insects: A review and synthesis. Ecol. Evol.8, 11337–11358. 10.1002/ece3.4557 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grubisic, M. & van Grunsven, R. H. A. Artificial light at night disrupts species interactions and changes insect communities. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci.47, 136–141. 10.1016/j.cois.2021.06.007 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders, D. & Gaston, K. J. How ecological communities respond to artificial light at night. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Integr. Physiol.329, 394–400. 10.1002/jez.2157 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Touzot, M. et al. Artificial light at night disturbs the activity and energy allocation of the common toad during the breeding period. Conserv. Physiol.7, coz002. 10.1093/conphys/coz002 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bird, B. L., Branch, L. C. & Miller, D. L. Effects of coastal lighting on foraging behaviorof beach mice. Conserv. Biol.18, 1435–1439 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spoelstra, K. et al. Experimental illumination of natural habitat—An experimental set-up to assess the direct and indirect ecological consequences of artificial light of different spectral composition. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B370, 20140129 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann, J., Palme, R. & Eccard, J. A. Long-term dim light during nighttime changes activity patterns and space use in experimental small mammal populations. Environ. Pollut.238, 844–851 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone, E. L., Harris, S. & Jones, G. Impacts of artificial lighting on bats: a review of challenges and solutions. Mamm. Biol.80, 213–219. 10.1016/j.mambio.2015.02.004 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies, T. W. & Smyth, T. Why artificial light at night should be a focus for global change research in the 21st century. Glob. Change Biol.24, 872–882. 10.1111/gcb.13927 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanmer, H. J., Boothby, C., Toms, M. P., Noble, D. G. & Balmer, D. E. Large-scale citizen science survey of a common nocturnal raptor: urbanization and weather conditions influence the occupancy and detectability of the Tawny Owl Strix aluco. Bird Study68, 233–244 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson, H. D. Another reason for nightjars being attracted to roads at night. Ostrich74, 228–230 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debrot, A. O. Nocturnal foraging by artificial light in three Caribbean bird species. J. Carib. Ornithol.27, 40–41 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foley, G. J. & Wszola, L. S. Observation of Common Nighthawks (Chordeiles minor) and Bats (Chiroptera) Feeding Concurrently. Northeast. Nat.24, 26–28. 10.1656/045.024.0208 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30.James, D. J. & McAllan, I. A. The birds of Christmas Island, Indian ocean: a review. Aust. Field Ornithol.31(Supplement), S1–S175 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez, A., Orozco-Valor, P. M. & Sarasola, J. H. Artificial light at night as a driver of urban colonization by an avian predator. Landscape Ecol.36, 17–27. 10.1007/s10980-020-01132-3 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morelli, F. et al. Effects of light and noise pollution on avian communities of European cities are correlated with the species’ diet. Sci. Rep.13, 4361. 10.1038/s41598-023-31337-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunardi, V. O., Filho, J. B. P., Medeiros, F. H. F., Hadler, P. & Lunardi, D. G. Artificial light at night and the diet of a bird of prey in Caatinga. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Física17, 580–593 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evens, R. et al. Skyglow relieves a crepuscular bird from visual constraints on being active. Sci. Total Environ.900, 165760. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165760 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sierro, A. & Erhardt, A. Light pollution hampers recolonization of revitalised European Nightjar habitats in the Valais (Swiss Alps). J. Ornithol.160, 749–761. 10.1007/s10336-019-01659-6 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dominoni, D., Quetting, M. & Partecke, J. Artificial light at night advances avian reproductive physiology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.280, 20123017. 10.1098/rspb.2012.3017 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, J.-S., Tuanmu, M.-N. & Hung, C.-M. Effects of artificial light at night on the nest-site selection, reproductive success and behavior of a synanthropic bird. Environ. Pollut.228, 117805. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117805 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russ, A., Lučeničová, T. & Klenke, R. Altered breeding biology of the European blackbird under artificial light at night. J. Avian Biol.48, 1114–1125. 10.1111/jav.01210 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raap, T. et al. Artificial light at night affects body mass but not oxidative status in free-living nestling songbirds: An experimental study. Sci. Rep.6, 35626. 10.1038/srep35626 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marín-Gómez, O. H. et al. Nightlife in the city: Drivers of the occurrence and vocal activity of a tropical owl. Avian Res.11 (2020).

- 41.Orlando, G. & Chamberlain, D. Tawny Owl Strix aluco distribution in the urban landscape: The effect of habitat, noise and light pollution. Acta Ornithol.57, 167–179 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor, I. Barn Owls: Predator–Prey Relationships and Conservation (Cambridge University Press, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galeotti, P., Morimando, F. & Violani, C. Feeding ecology of the tawny owls (Strix aluco) in urban habitats (northern Italy). Bollettino Di Zoologia 58, 143–150. 10.1080/11250009109355745 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goszczyński, J., Jabłoński, P., Lesiński, G. & Romanowski, J. Variation in diet of tawny owl Strix aluco L. along urbanization gradient. Acta Ornithol.27, 113–123 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gryz, J. & Krauze-Gryz, D. Changes in the tawny owl Strix aluco diet along an urbanisation gradient. Biologia74, 279–285. 10.2478/s11756-018-00171-1 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bank, L., Haraszthy, L., Horváth, A. & Horváth, F. G. Nesting success and productivity of the common Barn-owl Tyto alba: Results from a nest box installation and long-term breeding monitoring program in Southern Hungary. Ornis Hung.27, 1–31 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martínez, J. A. & Lopéz, G. Breeding ecology of the barn owl (Tyto alba) in Valencia (SE Spain). J. Ornithol.140, 93–99. 10.1007/BF02462093 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Béziers, P. & Roulin, A. Double brooding and offspring desertion in the barn owl Tyto alba. J. Avian Biol.47, 235–244. 10.1111/jav.00800 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zabala, J. et al. Proximate causes and fitness consequences of double brooding in female barn owls. Oecologia192, 91–103. 10.1007/s00442-019-04557-z (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuberogoitia, I., Martínez, J. A., Iraeta, A., Azkona, A. & Castillo, I. Possible first record of double brooding in the tawny owl Strix aluco. Ardeola51, 437–439 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hegyi, G. & Laczi, M. Using full models, stepwise regression and model selection in ecological data sets: Monte Carlo simulations. Ann. Zool. Fenn.52, 257–279 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 52.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2022).

- 53.Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Soft.67, 1–48 (2015).

- 54.Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression 3rd edn. (Sage Publications, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartoń K. MuMin: Multi-Model Inference. (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMin.

- 56.Mátics, E., Laczi, M., Schneider, Z., Hoffmann, G. & Mátics, R. Data from: Artificial light at night (ALAN) negatively affects the nest site occupancy but does not influence breeding success in two sympatric owl species (2024). Figshare dataset.10.6084/m9.figshare.27930849.v1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Hölker, F., Wolter, C., Perkin, E. K. & Tockner, K. Light pollution as a biodiversity threat. Trends Ecol. Evol.25, 681–682. 10.1016/j.tree.2010.09.007 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bekker, D., Janssen, R. & Buys, J. First records of predation of grey-long-eared bats (Plecotus austriacus) by the barn owl (Tyto alba) in the Netherlands. Lutra57, 43–47 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palacios, M. B., Kitching, T., Wright, P. G. R., Schofield, H. & Glover, A. Exclusion of barn owls Tyto alba from a greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum roost in Devon, UK. Conserv. Evid. J.20, 8–12. 10.52201/CEJ20/JYDD7577 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boldogh, S., Dobrosi, D. & Samu, P. The effects of the illumination of buildings on house-dwelling bats and its conservation consequences. Acta Chiropterol.9, 527–534 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rydell, J., Eklöf, J. & Sánchez-Navarro, S. Age of enlightenment: long-term effects of outdoor aesthetic lights on bats in churches. R. Soc. Open Sci.4, 161077. 10.1098/rsos.161077 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein, Á., László, C. & Mátics, R. Gyöngybagoly (Tyto alba). in: Magyarország ragadozó madarai és bagjai 2. kötet. Sólyomalakúak és bagolyalakúak. (ed. Haraszthy L. & Bagyura J.) 9–39 (Magyar Madártani és Természetvédelmi Egyesület, Budapest, 2022).

- 63.Petty, S. J., Shaw, G. & Anderson, D. I. Value of nest boxes for population studies and conservation of owls in coniferous forests in Britain. J. Raptor Res.28, 134–142 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams, C. A., Clair, C. C. S., Knight, E. C. & Bayne, E. M. Behaviour and landscape contexts determine the effects of artificial light on two crepuscular bird species. Landsc. Ecol.39, 10.1007/s10980-024-01875-3 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Rush, S. A., Rovery, T. R. & Naveda-Rodríguez, A. American Robin (Turdus migratorius) feeding young at night in an area of artificial light. J. Ornithol.166, 303–305. 10.1007/s10336-024-02217-5 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ziegler, A.-K. et al. Exposure to artificial light at night alters innate immune response in wild great tit nestlings. J. Exp. Biol.224, jeb239350 10.1242/jeb.239350 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Poprach, K. The Barn Owl (S. Sweeney, Trans.). TYTO, Nenakonice, Czech Republic. (2010).

- 68.Klein, Á., Mátics, R. & Schneider, Z. Breeding and conservation status of the Western Barn Owl (Tyto alba) in Zala County, Hungary. An overview of 39 years of data. Ornis Hung.31, 203–216. 10.2478/orhu-2023-0030 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Colvin, B. A. Common Barn-Owl population decline in Ohio and the relationship to agricultural trends. J. Field Ornithol.56, 224–235 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martínez, J. A. & Zuberogoitia, Í. Habitat preferences and causes of population decline for Barn Owls Tyto alba: A multi-scale approach. Ardeola51, 303–317 (2004). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The primary data supporting the results of this study are available at the Figshare digital repository10.6084/m9.figshare.27930849.v1.