Abstract

SHY1 codes for a mitochondrial protein required for full expression of cytochrome oxidase (COX) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutations in the homologous human gene (SURF1) have been reported to cause Leigh’s syndrome, a neurological disease associated with COX deficiency. The function of Shy1p/Surf1p is poorly understood. Here we have characterized revertants of shy1 null mutants carrying extragenic nuclear suppressor mutations. The steady-state levels of COX in the revertants is increased by a factor of 4–5, accounting for their ability to respire and grow on non-fermentable carbon sources at nearly wild-type rates. The suppressor mutations are in MSS51, a gene previously implicated in processing and translation of the COX1 transcript for subunit 1 (Cox1) of COX. The function of Shy1p and the mechanism of suppression of shy1 mutants were examined by comparing the rates of synthesis and turnover of the mitochondrial translation products in wild-type, mutant and revertant cells. We propose that Shy1p promotes the formation of an assembly intermediate in which Cox1 is one of the partners.

Keywords: cytochrome oxidase/Leigh’s syndrome/MSS51/SHY1/SURF1

Introduction

SHY1, the yeast homologue of the human SURF1 gene, codes for a mitochondrial protein necessary for full expression of respiration and cytochrome c oxidase (COX) (Mashkevich et al., 1997). Mutations in SURF1 are responsible for most cases of Leigh’s syndrome (LS) associated with cytochrome oxidase deficiency (Tiranti et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998), a heterogeneous group of mitochondrial diseases with preferential neuropathological symptoms and morphological and histochemical defects in mitochondria (Leigh, 1951). Patients with Leigh’s syndrome have severely lowered levels of COX, although there are other variable biochemical defects associated with the disease (DiMauro and De Vivo, 1996; Rahman et al., 1996; Tiranti et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998). The similarity in the biochemical phenotypes of mitochondria from shy1 mutants and from Leigh patients implies a common function of the two gene products.

The precise function of Shy1p and Surf1p is not known. Studies on Surf1p have focused on its presumed role in COX assembly. Mitochondrial COX, the terminal enzyme of the respiratory chain, has three redox centers that catalyze a sequential transfer of electrons from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen. COX is located in the mitochondrial inner membrane and in yeast is made up of 12 different subunits. The catalytic core of the enzyme consists of three subunits derived from mitochondrial genes. The other nine subunits are products of nuclear genes. Assembly of COX is a complicated process that requires the assistance of numerous nuclear gene products. An understanding of their functions is only now beginning to emerge, mainly as the result of studies of yeast mutants (Glerum et al., 1996; Hell et al., 2000, 2001; Souza et al., 2000).

Unlike other assembly-defective strains of yeast that display a complete absence of COX (Glerum and Tzagoloff, 1998), shy1 mutants produce 10–15% fully assembled and functional COX. In addition to their lower COX content, shy1 mutants exhibit other alterations. For example, they have elevated levels of cytochrome c and their NADH cytochrome c reductase activity is two times higher than in wild type (Mashkevich et al., 1997). LS patients also have 10–30% of normal COX. Analysis of surf1 mutant cell lines by blue native gel electrophoresis indicates a partial block of COX assembly at an early step of the pathway, most likely before the incorporation of subunit II into the nascent intermediates composed of subunit I alone or subunit I plus subunit IV (Coenen et al., 1999; Tiranti et al., 1999).

To understand better the role of Shy1p/Surf1p in COX assembly we have isolated revertants of shy1 mutants with nearly normal growth properties on respiratory substrates. The revertants have been analyzed genetically and shown to have extragenic nuclear suppressors. The respiratory activities of mutants and revertants indicate that rescue of the respiratory defect correlates with an increase in the mitochondrial concentration of COX. The suppressor was cloned from a plasmid library constructed from the nuclear DNA of the revertant and identified to be MSS51, a yeast gene previously implicated to play a role in translation of COX subunit 1 (Cox1) (Decoster et al., 1990). In vivo or in organello labeling of mitochondrial translation products revealed substantially reduced expression of Cox1 in the mutant. The cytochrome oxidase deficiency is partially restored by the suppressor, which is proposed to increase translation of Cox1, thereby compensating for a Shy1p-dependent step in assembly of the enzyme.

Results

Properties of shy1 mutants and revertants

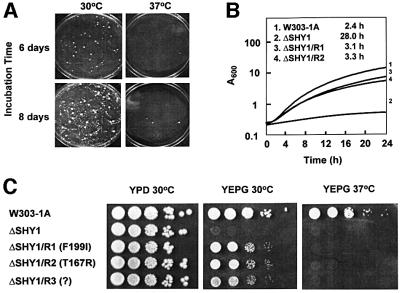

Both the point mutant W125 and the shy1 null mutant W303ΔSHY1/U2 (ΔSHY1) spontaneously convert to respiratory competence at a high frequency. When 107 cells are spread on rich glycerol medium (YEPG), revertant colonies appear after 4–5 days of incubation at 30°C. With prolonged incubation, the plates become overgrown with revertants (Figure 1A). Revertants also appear at 37°C, but they are fewer in number. Growth of two independent revertants (ΔSHY1/R1 and ΔSHY1/R2) on solid or in liquid YEPG is only slightly slower than the parental wild type (Figure 1B and C). The doubling time on glycerol was 2.4 h for the wild type, 3.3 h for the revertant and 28 h for the mutant.

Fig. 1. Growth properties of shy1 mutants and revertants. (A) The shy1 null mutant ΔSHY1 was plated at a density of 107 cells/plate on rich ethanol/glycerol (YEPG). The plates were photographed after 6 and 8 days of incubation at 30 and 37°C. (B) The respiratory-competent strain W303-1A, the shy1 null mutant ΔSHY1, and two independent revertants ΔSHY/R1 and ΔSHY/R2 were inoculated into liquid YEPG media and incubated with vigorous shaking at 30°C. Growth was monitored by absorbance at 600 nm. The doubling times for the different strains are indicated. (C) Serial dilutions of the respiratory-competent strain W303-1A, the shy1 mutant ΔSHY1, and three revertants ΔSHY/R1, ΔSHY/R2 and ΔSHY/R3 with the mss51 mutations indicated were spotted on YPD and YEPG plates and incubated at 30 and 37°C for 2–3 days.

Crosses of two independent revertants, ΔSHY1/R1 and ΔSHY1/R2, to the shy1 null mutant produced respiratory-competent diploid cells, indicating that the mutations behave as dominant suppressors. The suppressors were ascertained to be nuclear by two criteria. Revertants were converted to ρo/ρ– derivatives by treatment with ethidium bromide. Panels of the ρo/ρ– clones were crossed to the null mutants. The diploid cells issued from these crosses had the same phenotype as the haploid revertants, attesting to the nuclear nature of the suppressors. This was confirmed by tetrad analysis of diploid cells obtained from crosses of the revertants to the ΔSHY1 mutant. The meiotic spore progeny from 16 complete tetrads all had the URA3 marker for the shy1 null allele. Two spores in each tetrad were respiratory competent, consistent with the presence of a dominant nuclear suppressor. Dissections of tetrads obtained from crosses of the revertants to the parental wild-type strains (Ura–) failed to show co-segregation of the respiratory competence, and uracil prototrophy indicated that neither suppressor is linked to SHY1. The presence of the suppressors in a wild-type nuclear background (20% of the progeny) had no effect on respiration (data not shown).

Respiration in whole cells and in isolated mitochondria is partially restored in shy1 revertants

The ΔSHY1 strain respires at 20% of the wild-type rate in whole-cell assays using galactose or glucose as substrates (Figure 2A). This respiration is inhibited 59% by antimycin A (AA) and 93% by KCN. The respiratory activity of the revertant is increased to 78% of wild type and is completely sensitive to AA and KCN. These high in vivo respiration rates explain the ability of the revertant to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources. Even though mutant cells have 20% residual respiration, this activity is only partially sensitive to AA. The reduced oxidative capacity combined with partial sensitivity to AA helps to explain the mutant’s failure to grow on respiratory substrates. Identical results were obtained with the shy1 mutant containing partially deleted SHY1 (Mashkevich et al., 1997).

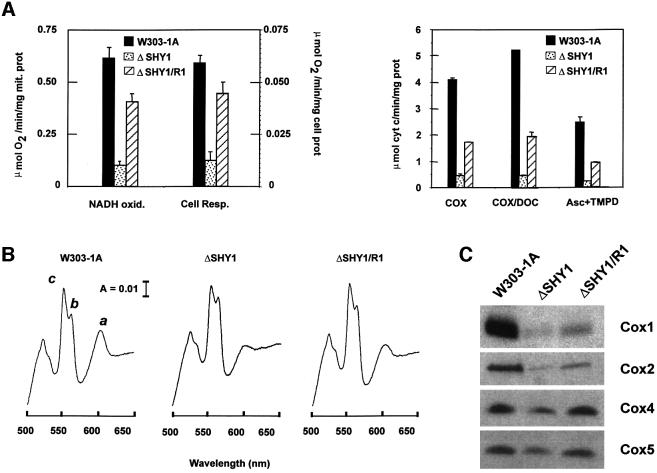

Fig. 2. Functional characterization of the shy1 null mutant and revertant. (A) In the left panel, mitochondria prepared from the wild type (W303-1A), from the shy1 mutant (ΔSHY1) and from the revertant (ΔSHY1/R1) were assayed polarographically for NADH oxidase (NADH oxid.). Respiration was also assayed in whole cells in the presence of glucose (Cell Resp.). The specific activities reported were corrected for AA-insensitive respiration. The bars indicate the mean ± SD from three independent sets of measurements. In the right panel, COX was assayed in frozen–thawed mitochondria (COX) and in mitochondria permeabilized with potassium deoxycholate (COX/DOC) by measuring oxidation of ferrocytochrome c at 550 nm. COX activity was also assayed polarographically by measuring the oxygen consumption rate in the presence of ascorbate plus TMPD. (B) Cytochrome spectra. Mitochondria were extracted at a protein concentration of 5 mg/ml with potassium deoxycholate under conditions that quantitatively solubilize all the cytochromes (Tzagoloff et al., 1975). Difference spectra of the reduced (sodium dithionite) versus oxidized (potassium ferricyanide) extracts were recorded at room temperature. The α absorption bands corresponding to cytochromes a and a3 have maxima at 603 nm (a). The maxima for cytochrome b (b) and for cytochrome c and c1 (c) are 560 and 550 nm, respectively. (C) Steady-state concentrations of COX subunits. Total mitochondrial proteins (30 µg) separated by 16.5% SDS–PAGE were transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with subunit-specific antibodies to COX subunits.

Respiration was also assayed polarographically in isolated mitochondria by measuring the rates of oxygen consumption with NADH as substrate. AA-sensitive oxidation of NADH in ΔSHY1 mitochondria was 14% of wild type (Figure 2A). This rate was four times higher in the ΔSHY1/R1 revertant. Even so, overall oxidation of NADH in the revertant was still only 60% of the wild-type rate (Figure 2A). The possibility that the growth defect of shy1 mutants is due to a lesion in oxidative phosphorylation was excluded by measurements of the phosphorylation efficiency in isolated mitochondria. The P/O values of wild-type and mutant mitochondria were 1.31 and 1.17, respectively, with succinate as the substrate.

Partial restoration of respiration in shy1 revertants is explained by an increase in COX

The mitochondrial concentration of cytochromes a and a3 is a reliable gauge of COX content and activity. Spectra of mitochondrial cytochromes indicated the revertants to have more ‘a’ type cytochromes than the mutant (Figure 2B). The increase in spectrally detectable cytochrome oxidase was also confirmed by direct enzyme assays. The COX activities of mutant and revertant mitochondria were assayed spectrophotometrically by measuring oxidation of ferrocytochrome c, and polarographically by monitoring oxygen consumption with ascorbate plus N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) as the substrate (Figure 2A). To maximize substrate availability in the spectrophotometric assay, mitochondria were permeabilized with low concentrations of deoxycholate. Under all assay conditions, the specific activities of COX in revertant mitochondria were approximately four times higher than in the mutant and ranged from 37 to 40% of wild type.

Consistent with the above results, western blot analysis of total mitochondrial proteins revealed a higher steady-state concentration of COX subunits in the revertant than in the shy1 null mutant (Figure 2C). This is not due to any effect of the suppressor on transcription or processing of the mitochondrially derived mRNAs (data not shown). Subunit 1 (Cox1), subunit 2 (Cox2) and subunit 3 (Cox3) were ascertained to be correctly inserted in the inner mitochondrial membrane, as demonstrated by their susceptibility to proteinase K digestion in [35S]methionine-labeled mitoplasts (data not shown). In such assays, proteins that are not inserted into the phospholipid bilayer of the inner membrane are protected against proteinase K due to their location on the matrix side of the membrane (Hell et al., 2000).

Identification of MSS51 as the suppressor

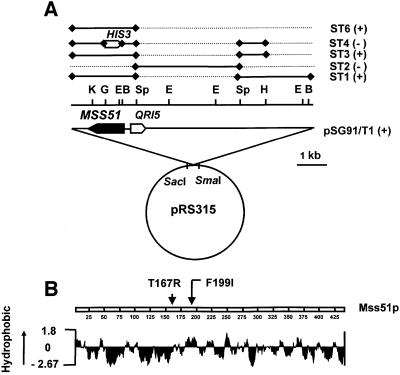

The extragenic suppressor in ΔSHY1/R1 was cloned by transformation of the shy1 null mutant with a genomic library constructed from the nuclear DNA of the revertant. Transformation of ΔSHY1 with the library yielded ∼70 000 clones, of which five were respiratory competent. Plasmids obtained from the respiratory-competent transformants were amplified in Escherichia coli and their nuclear DNA inserts characterized. Restriction mapping indicated all five plasmids to have identical or overlapping fragments of nuclear DNA. The sequences of the end points of the insert in one of the plasmids (pSG91/T1) localized it between coordinates 550118 and 558028 on chromosome XII (Figure 3A). This plasmid was used to subclone the suppressor by transferring different regions of the insert to the yeast integrative vector YIp351 (Hill et al., 1986) and testing the ability of the new constructs to confer respiration on ΔSHY1 (Figure 3A). The results of these transformations indicated that the region of DNA containing only MSS51 was sufficient to produce the revertant phenotype. The identification of MSS51 as the suppressor was confirmed by linkage analysis. Diploid cells issued from a cross of ΔSHY1/R1 to the mss51 point mutant E4-218 were sporulated and 14 tetrads were dissected. In every case, only two of the meiotic spore progeny were respiratory competent, indicating linkage of the suppressor to MSS51.

Fig. 3. Identification of MSS51 as the suppressor gene. (A) Restriction maps of pSG91/T1 and of subclones. The locations of the restriction sites for BamHI (B), EcoRI (E), BglII (G), HindIII (H), KpnI (K) and SphI (Sp) are shown above the nuclear DNA insert in pSG91/T1. The regions of the nuclear insert in pSG91/T1 subcloned in YIp351 are represented by the solid bars in the upper part of the figure. The discontinuous lines represent the regions of pSG91/T1 deleted in each subclone. The plus and minus signs indicate suppression or lack thereof, respectively, of the shy1 null mutant by the subclones. The MSS51 reading frame and the direction of transcription of the gene are indicated by the solid arrow. The direction of transcription of the adjoining QRI5 gene is shown by the open arrow for orientation purposes. (B) Hydropathy profile of Mss51p (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982). The arrows indicate the location of the suppressor mutations identified.

The sequence of MSS51 in pSG91/T1 disclosed a T595A transversion resulting in an F199I change in a hydrophobic region of the protein (Figure 3B). A second mutation in this region was identified in ΔSHY1/R2. The mutation in the latter revertant is a C500G base change resulting in the substitution of an arginine for a threonine at residue 162. The mss51F199I and mss51T167R alleles do not affect growth of an otherwise wild-type strain on non-fermentable substrates either at 30 or 37°C (data not shown). Suppression of the ΔSHY1 by both alleles, however, is temperature sensitive and is almost completely abolished at 37°C (Figure 1C).

The high frequency with which shy1 null mutants revert could indicate the existence of multiple suppressor genes. Alternatively, suppression activity could be conferred by different mutations in MSS51. Genetic analyses of seven revertants indicated that in all cases the suppressors were linked to MSS51. The revertants used in the linkage analysis included two revertants of an ‘a’ mating type ΔSHY1 mutant, three revertants of an α mating type ΔSHY1 mutant, and two revertants of the shy1 point mutant W125. The lower yield of revertants at 37°C (see Figure 1A) suggested that they might represent a different class of mutations. This turned out not to be the case, as mutations in two revertants isolated at the higher temperature were also linked to MSS51.

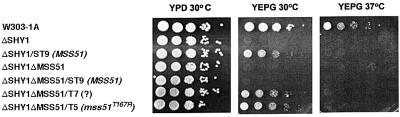

Suppression of shy1 mutants by wild-type MSS51

Wild-type MSS51 functions as a suppressor of shy1 mutants when present in two or more copies. Integration of MSS51 at the chromosomal LEU2 locus of shy1 mutants restores growth on rich glycerol/ethanol medium, although suppression is not as effective as the suppressor alleles (compare ΔSHY1/ST9 to ΔSHY1ΔMSS51/T5 or T7 in Figure 4). As expected, integration of the wild-type construct (pG91/ST9) in a mutant deleted for both SHY1 and MSS51 failed to restore respiratory growth (ΔSHY1ΔMSS51/ST9 in Figure 4). It is noteworthy that increasing the number of copies of MSS51 above two did not further improve the mutant’s ability to respire (data not shown).

Fig. 4. Suppression of the respiratory defect of shy1 mutants by wild-type and mutant MSS51. MSS51 was cloned in YIp351 and integrated at the chromosomal LEU2 locus of the shy1 null mutant. MSS51 and the two suppressor genes mss51T167R and mss51? were also integrated at the LEU2 locus of ΔSHY1ΔMSS51, a mutant construct with null mutations in MSS51 and SHY1. Serial dilution of the wild-type W303-1A, the single and double mutants and the transformants starting with 105 cells were spotted on rich glucose (YPD) and rich glycerol/ethanol (YEPG) plates and incubated at 30 and 37°C for 2.5 days.

Analysis of Cox1 in shy1 mutants and revertants

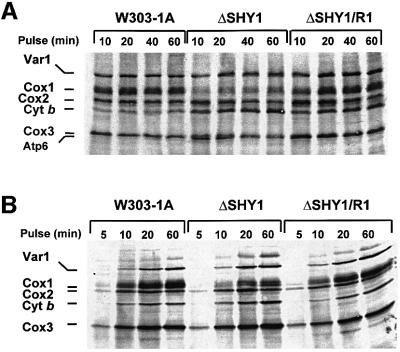

Mss51p is a specific translation factor for COX1 mRNA (Faye and Simon, 1983; Siep et al., 2000). Although mss51 mutants are blocked in processing of the COX1 pre-mRNA, this is probably secondary to the translation defect. The ability of wild-type and mutant forms of MSS51 to partially correct the COX deficiency of shy1 mutants suggested that the mechanism of suppression might, in some way, be related to expression of the mitochondrial COX1 gene. The effect of shy1 mutations on translation and/or stability of Cox1 were examined by pulse labeling of whole cells and isolated mitochondria with [35S]methionine. In both assays, Cox1 was visibly less labeled in the mutant than in wild type or the revertant (Figure 5A and B). The incorporation of [35S]methionine into the different mitochondrial translation products was quantitated in several independent in vivo and in organello experiments. The results, summarized in Table I, indicate that the label in Cox1, when normalized to cytochrome b, Cox2 (subunit 2) or Cox3 (subunit 3), is 3–4 times lower in the mutant than the wild type. Cox1 in the revertant was as well labeled as in wild type, even though the ratios reported in Table I are somewhat lower in the revertant because of a greater incorporation of [35S]methionine into the other subunits.

Fig. 5. Mitochondrial protein synthesis in shy1 null mutants and revertants. (A) In vivo labeling of mitochondrial DNA products. Wild-type (W303), mutant (ΔSHY1) and revertant (ΔSHY1/R1) cells were labeled with [35S]methionine at 30°C for the times indicated in the presence of cycloheximide. (B) In organello protein synthesis. Mitochondria isolated from the same strains were labeled with [35S]methionine at 30°C in the absence of cycloheximide. Equivalent amounts of total cellular or mitochondrial proteins were separated by PAGE on a 17.5% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and exposed to an X-ray film. The mitochondrial translation products are identified on the left. The migration of Cox2 relative to Cox1 differs from that seen in (A) because a different PAGE buffer system was used for the separation.

Table I. Cox1p expression in wild-type and shy1 mutants.

| Ratios |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 |

Exp. 2 |

Exp. 3 |

|||||||

| WT | ΔSHY1 | ΔSHY1/R1 | WT | ΔSHY1 | ΔSHY1/R1 | WT | ΔSHY1 | ΔSH1/R1 | |

| In organello | |||||||||

| Cox1/Cox2 | 4.43 | 1.55 | 3.78 | 4.57 | 1.28 | 3.98 | – | – | – |

| Cox1/Cox3 | 3.05 | 0.33 | 2.40 | 3.11 | 0.42 | 2.28 | 1.30 | 0.36 | 1.30 |

| Cox1/cyt b | 9.59 | 1.43 | 6.29 | 6.82 | 1.15 | 5.86 | 3.90 | 0.60 | 2.80 |

| In vivo | |||||||||

| Cox1/Cox2 | 1.46 | 0.55 | 1.27 | 0.93 | 0.46 | 1.13 | 1.27 | 0.27 | 0.96 |

| Cox1/Cox3 | 1.60 | 0.57 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 0.56 | 1.17 | 1.42 | 0.40 | 1.18 |

| Cox1/cyt b | 1.74 | 0.42 | 1.48 | 2.66 | 0.48 | 2.05 | 1.95 | 0.44 | 1.69 |

Mitochondrial translation products were labeled with [35S]methionine for 20 min at 23°C in organello and in vivo in the presence of cycloheximide as described in Materials and methods. Proteins were separated by PAGE on a 17.5% polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The radioactivity associated with Cox1, Cox2, Cox3 and cytochrome b was quantitated in a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The table reports the results of three independent experiments. Different preparations of mitochondria were labeled in each of the in organello experiments.

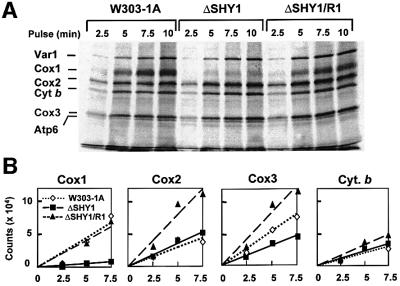

Most mitochondrial translation products, including Cox1, were maximally labeled under in vivo conditions after a 10 min pulse (Figure 5). To assess better the effect of the shy1 mutation on the amount of Cox1 available for assembly, the rate of incorporation of [35S]methionine into the different translation products was also measured at shorter times. The results of such experiments indicate that incorporation of [35S]methionine into Cox1 in the mutant is <20% of wild type, even at the earliest time points (Figure 6). This was not true of Cox2 or cytochrome b, both of which were labeled to approximately the same extent in the mutant and wild type. Although there was also less labeling of Cox3 in the mutant, the effect was not nearly as dramatic (<50% reduction) as with Cox1. Cox1 was equally well labeled in the revertant and wild-type cells during short pulses, as was the case when translation was allowed to proceed for longer times (Figure 5). Cox2 and Cox3 were also more labeled in the revertant than in wild type (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Kinetics of in vivo labeling of mitochondrial products during short pulses. (A) Wild-type (W303), mutant (ΔSHY1) and revertant (ΔSHY1/R1) cells were labeled with [35S]methionine. Total cellular proteins were extracted, depolymerized in sample buffer and separated on a 17.5% polyacrylamide gel. The labeling conditions, sample preparation and gel electrophoresis were identical to those described in Figure 5A. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and exposed to X-ray film. (B) The radioactivity associated with Cox1, Cox2 and Cox3, and with cytochrome b was also quantitated in a PhosphorImager. The results were analyzed by linear regression.

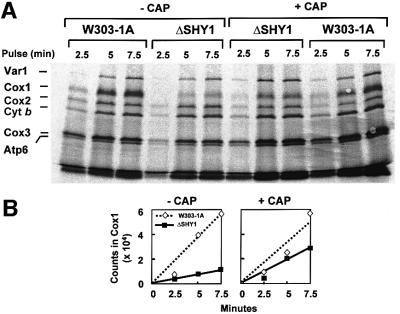

The poor labeling of Cox1 in the mutant could be due to an effect of the shy1 mutation on the rate of synthesis and/or turnover of the protein. A direct requirement of Shy1p for translation of Cox1 is unlikely in view of the rates measured in cells that had been allowed to incubate for 2 h in medium containing chloramphenicol prior to the in vivo assay. The incubation in chloramphenicol leads to an accumulation of cytoplasmically synthesized proteins that act to increase the translation rate, presumably by drawing newly synthesized mitochondrial products into their respective assembly pathways (Tzagoloff, 1971). In agreement with earlier studies, the chloramphenicol pre-incubation stimulated [35S]methionine incorporation into most mitochondrial products in the wild-type strain, including Cox3, cytochrome b and Atp6 (Figure 7A). This was also true of the mutant. In addition, the chloramphenicol pre-incubation doubled the incorporation of label into Cox1 in the mutant, but not in the wild type (Figure 7A and B). Similar results were obtained with the point mutant W125.

Fig. 7. Effect of chloramphenicol on the kinetics of in vivo labeling of mitochondrial products. (A) Cells were grown and labeled at 30°C as in Figure 6, except that one half of the culture was incubated in the presence of 2 mg/ml chloramphenicol during the last 2 h of growth (+ CAP). Cells were harvested from both media and washed twice with a solution containing 40 mM potassium phosphate plus 2% galactose prior to labeling. Samples were removed after the labeling times indicated. Total cellular proteins were separated on a 17.5% gel as in Figure 6. (B) The radiolabeled Cox1 was quantitated in a PhosphorImager and the results were analyzed by linear regression.

Turnover of mitochondrial translation products

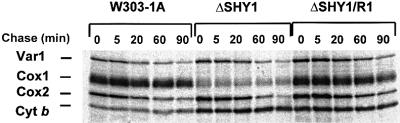

The results of the previous section suggested that the Cox1 deficit in shy1 mutants is not due to a direct role of Shy1p in translation, although an indirect effect on translation was not excluded. The deficit of Cox1 could be the result of increased turnover of Cox1. The stability of newly translated mitochondrial products was examined by pulse–chase experiments. Cells were pulsed with [35S]methionine at 30°C for 20 min in the presence of cycloheximide, and chased at the same temperature for different times following addition of puromycin and excess cold methionine. The products made during the pulse were relatively stable in all three strains for the first 5 min of the chase, but at longer times were progressively degraded (Figure 8). The exception was cytochrome b, whose concentration did not change even after 90 min of chase. While there was some decrease of Cox1 in the wild type and the revertant, the residual 20% of Cox1 in the mutant did not decrease further during the chase. In other experiments we observed some decrease of subunit 1 in the mutant, but less than in the wild type and the revertant. The explanation for the apparent greater stability of unassembled subunit 1 in the mutant is not clear, but could be related to its lower concentration compared with wild type or the revertant.

Fig. 8. Turnover of in vivo labeled mitochondrial translation products. Cells were grown and labeled for 20 min at 30°C with [35S]methionine as in Figure 5. The labeling reaction was terminated by addition of excess 80 mM cold methionine and 4 µg/ml puromycin (0 time). Samples of the cultures were collected after the incubation times at 30°C indicated and processed as in Figure 6.

Do Mss51p and Shy1p interact with each other and/or with COX subunits?

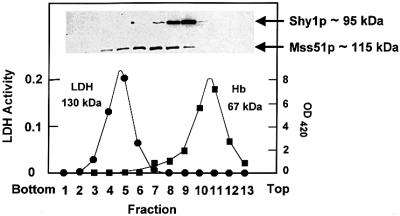

Shy1p and Mss51p are located in the mitochondrial inner membrane. To test whether they exist in a complex, wild-type mitochondria were extracted either with deoxycholate or laurylmaltoside and the properties of the solubilized proteins were examined by sedimentation through sucrose gradients.

The results of the sucrose gradient analysis indicated Shy1p and Mss51p to behave as distinct proteins. The mass of native Shy1p solubilized with deoxycholate was estimated to be 95 kDa, a value approximately two times higher than the mass of the monomer. Similarly, the value of 115 kDa obtained for the mass of native Mss51p is 2–3 times greater than that of the monomer. Each protein peaked in a separate fraction with a homogeneous distribution in the gradient (Figure 9). Identical values were obtained when Shy1p was extracted from mitochondria of a mss51 null mutant and conversely when Mss51p was extracted from a shy1 null mutant, confirming the absence of a stable complex of the two proteins.

Fig. 9. Sedimentation properties of Shy1p and Mss51p. Mitochondria (7 mg of protein) from the wild-type haploid strain W303-1A were solubilized in the presence of 1 M KCl and 1% KDOC. The clarified extract obtained by centrifugation at 200 000 gav for 15 min was mixed with hemoglobin and lactate dehydrogenase, and applied to 5 ml of a linear 10–25% sucrose gradient containing 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.1% Triton X-100. Following centrifugation for 14 h at 50 000 r.p.m. in a Beckman SW65 rotor, the gradient was collected in 13–14 equal fractions. Each fraction was assayed for hemoglobin (Hb) by absorption at 410 nm, and for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity by measuring NADH-dependent conversion of pyruvate to lactate. The distributions of Shy1p and Mss51p were assayed by western blot analysis. The masses of Shy1p and Mss51p were determined from the positions of the respective peaks relative to those of the markers (Martin and Ames, 1961).

The masses of Shy1p and Mss51p were also measured after extraction with laurylmaltoside. Shy1p sedimented as two distinct peaks, one of which corresponded to the 95 kDa species detected in deoxycholate extracts and the other to the 250 kDa complex previously reported by Nijtmans et al. (2001). Under these extraction conditions, however, all the Mss51p had a mass of 115 kDa (data not shown). These results suggest that if Shy1p and Mss51p are associated with each other, the complex is disrupted under the extraction conditions used for the sedimentation analyses. No evidence could be obtained for an interaction of Mss51p and Shy1p with a two-hybrid assay. We were also unable to detect a transient interaction of Shy1p and Mss51p with any of the mitochondrially encoded COX subunits. COX subunits labeled in organello in the absence or presence of cleavable cross-linkers failed to be enriched in pull-down experiments using antibodies against Mss51p or Shy1p.

Discussion

Mutations in SHY1, or its human homologue SURF1, produce similar biochemical phenotypes characterized chiefly by a deficit of COX. This has been inferred to indicate that the respiratory defect of shy1 mutants and LS patients is a consequence of impaired COX assembly (Tiranti et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998). Since shy1 mutants retain 10–15% functional COX, Shy1p either has a redundant function or simply increases the efficiency with which the enzyme is assembled.

Both shy1 null and point mutants revert spontaneously to respiratory competence. The revertants grow on respiratory substrates with a generation time only slightly longer than the parental wild type. AA- and cyanide-sensitive oxidation of NADH and succinate is increased by a factor of 4–5, corresponding to ∼40–45% of the rates measured in wild-type mitochondria. Mutants with less than half the oxidative capacity of wild-type cells, therefore, are able to grow almost normally on non-fermentable carbon sources. Whole-cell respiration of shy1 mutants with either glucose or galactose as substrate is ∼13% of wild type when corrected for the 41% antimycin-insensitive rate. It is not clear what components are involved in this alternate pathway, seen predominantly in the mutant. We have also noted that cell respiration in the revertant is increased to 80% of wild type, a value considerably higher than expected from the NADH oxidase activity measured in isolated mitochondria. The rate-limiting step in aerobic metabolism of sugars must, therefore, occur prior to oxidation of NADH.

The revertant phenotype can be accounted for by the observed increase in COX. Both spectrophotometric and polarographic assays of isolated mitochondria indicate 4–5 higher COX activity in the revertant. Comparable increases are seen in the spectra of ‘a’ type cytochromes and in the steady-state levels of COX subunits. The two sets of data demonstrate that reversion to respiratory competence is paralleled by a partial restoration in the expression of fully assembled and functional COX.

The suppressor activity of MSS51 has bearing on the nature of the biochemical defect in shy1 strains and opens new ways for exploring the function of Shy1p. MSS51 was first reported to code for a factor involved in splicing of the primary COX1 transcript, based on the finding that mss51 mutants harboring a mitochondrial COX1 gene with multiple introns are unable to process the primary transcript (Faye and Simon, 1983). In subsequent studies, mss51 mutants with an intronless variant of the gene were also found to be deficient in Cox1 despite their ability to express normal amounts of the COX1 mRNA (Decoster et al., 1990). Mss51p was consequently proposed to be a COX1 translation factor similar to other mitochondrial messenger-specific translation factors (Poutre and Fox, 1987; Costanzo et al., 1989; Haffter and Fox, 1992). The accumulation in mss51 mutants of incompletely processed COX1 transcripts is probably a secondary effect of their failure to translate intron-encoded products essential for self-splicing. A similar situation has been shown to occur in mutants unable to translate the intron bearing COB transcript for cytochrome b (Rödel et al., 1985; Muroff and Tzagoloff, 1990). Independent of whether Mss51p functions strictly in translation or also plays a direct role in processing of the COX1 primary transcript, its ability to partially suppress the COX defect of shy1 mutants implicates Shy1p either in expression or stability of Cox1. A requirement of Shy1p in RNA processing can be excluded based on the results of northern analyses showing normal levels of fully processed COX1 mRNA in shy1 mutants (data not shown).

Whole-cell assays of mitochondrial protein synthesis indicate 4–5 times less [35S]methionine incorporation into Cox1 in shy1 mutants. This was not true of the other translation products, which are as well and in some cases even more extensively labeled in the mutant than in wild type. The large decrease in Cox1 labeling is unlikely to be due to a direct requirement of Shy1p for translation of this protein since pre-incubation of mutant cells in the presence of chloramphenicol partially reversed the apparent translation defect. It is also difficult to rationalize how Shy1p could be a messenger-specific translation factor in view of its widespread occurrence in organisms with very different mitochondrial genetic and protein synthetic systems (Poyau et al., 1999).

Expression of Cox1, however, could be affected indirectly if its translation is coupled to a Shy1p-dependent downstream assembly event. This type of translational control, termed CES (control by epistasy of synthesis), has been described in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Wollman et al., 1999; Choquet et al., 2001). Recent studies of this system suggest that TCA, a protein factor required for translation of cytochrome f on chloroplast ribosomes, interacts not only with the mRNA, but also with the cytochrome f product. When bound to cytochrome f, it is incompetent in promoting translation. The release of TCA from the complex to a translationally active state occurs as a result of a competitive interaction of cytochrome f with subunit IV, its normal partner in the b6f complex (Choquet et al., 2001). A similar mechanism can be invoked to account for the observations reported here. For example, the efficacy of Mss51p as a Cox1-specific translation factor could be regulated by its interaction with subunit 1 or one of the other mitochondrially encoded subunits of COX. The availability of Mss51p for activation of Cox1 translation in this model would be regulated by Shy1p if the latter promotes an assembly step leading to the disengagement of Cox1 from Mss51. According to this model, suppression can be explained either by more efficient translation of the COX1 mRNA or by a lowered affinity of the mutant Mss51p (suppressor) for Cox1. Our inability to detect a Cox1–Mss51p complex and the apparent absence of Mss51p in other organisms, including mammalian mitochondria, tend to argue against, but do not exclude, this or a related mechanism.

The lowered expression of Cox1 in the mutant can also be explained by increased turnover of the protein. Accordingly, the conversion of newly synthesized Cox1 from a protease-labile to a protected state is coupled to an event catalyzed by Shy1p. For example, protection against protease degradation might simply follow membrane insertion of Cox1. Alternatively, protection against rapid degradation could be a consequence of an interaction of Cox1 with another component during the normal assembly pathway. Shy1p need not necessarily play a direct role in either process, but instead could influence the equilibrium towards the protected state by catalyzing a downstream event.

In this model, the 15–30% of newly synthesized Cox1 detected in the mutant represents the fraction of protein that escapes rapid proteolytic degradation by virtue of having made the transition to a protease-protected state in the absence of Shy1p. The fraction of protease-protected Cox1 is increased in the revertant due to more efficient translation of the protein in the presence of the suppressor or of an extra copy of the wild-type MSS51 gene. The larger pool of Cox1 available for assembly in the revertant compensates for the absence of Shy1p, but only partially. The slower or less efficient assembly of COX, and hence Cox1 utilization, in the absence of Shy1p, can explain the apparent discrepancy between the normal levels of newly synthesized Cox1 and the reduced steady-state levels of this protein in the revertant. In the revertant, therefore, only part of the available Cox1 is used for assembly. It is of interest that the relative amounts of radiolabeled Cox1 detected in wild-type, mutant and revertant cells after long-term chase (Figure 8) are comparable with the steady-state ratios of assembled COX in these strains. The turnover of what we referred to as protease-protected Cox1 in this experiment is a much slower process and is to be distinguished from the rapid turnover that leads to the Cox1 deficit in the mutant.

The genetic interaction of the MSS51 suppressors and SHY1 suggested the possibility that their products might interact physically. At present, however, evidence for the existence of such a complex could not be obtained by direct biochemical means or by two-hybrid tests.

The MSS51 suppressors reported here rescue the respiratory defect of shy1 but not of other COX-deficient mutants (our unpublished results), indicating that the function of Shy1p, and probably Surf1p as well, is closely related to some aspect of Cox1 metabolism. Specifically in the yeast model of Leigh’s syndrome we propose Shy1p/Surf1p to interact directly with Cox1 or with an assembly intermediate in which Cox1 is one of the interacting partners.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and media

The genotypes and sources of the S.cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table II. The compositions of the growth media have been described elsewhere (Myers et al., 1985).

Table II. Genotypes and sources of yeast strains.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| KL14-4A | a his4 trp2 | Tzagoloff et al. (1976) |

| D273-10B/A1 | α met6 | Tzagoloff et al. (1976) |

| CB11 | a ade1 | Ten Berge et al. (1974) |

| W303-1A | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | a |

| W303-1B | α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | a |

| W303 | a/α ade2-1/ade2-1 his3-1,15/his3-1/15 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 trp1-1/trp1-1 ura3-1/ura3-1 | W303-1A × W303-1B |

| W303ΔSHY1/U | α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 shy1::URA3 | Mashkevich et al. (1997) |

| aW303ΔSHY1/U | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 shy1::URA3 | Mashkevich et al. (1997) |

| W303ΔSHY1/U2 | α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 Δshy1::URA3 | this study |

| aW303SHY1/U2 | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 Δshy1::URA3 | this study |

| W303ΔMSS51 | α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 mss51::HIS3 | this study |

| aW303ΔMSS51 | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 mss51::HIS3 | this study |

| a E4-218 | a ade1 mss51 | Tzagoloff et al. (1975) |

| E4-218 | α mss51 | Tzagoloff et al. (1975) |

| aW303ΔSHY1, mss51 | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 Δshy1::URA3 mss51 | aW303ΔSHY1 × E4-218 |

| aW303ΔSHY1ΔMSS51 | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 Δshy1::URA3 mss51::HIS3 | W303ΔSHY1 × aW303ΔMSS51 |

| W125 | a ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 shy1 | Mashkevich et al. (1997) |

| C173/U1 | α ura3-1 shy1-1 | Mashkevich et al. (1997) |

aDr Rodney Rothstein, Department of Human Genetics, Columbia University.

Construction of W303ΔSHY1/U2, W303ΔMSS51 and the double mutant W303ΔSHY1ΔMSS51

W303ΔSHY1/U, the shy1 mutant used in the prior study (Mashkevich et al., 1997), contains the N-terminal coding sequence of the gene. To obviate possible complications stemming from a partial residual Shy1p function in this strain, a mutant (W303ΔSHY1/U2) with a deletion of the entire SHY1 was constructed. The phenotype of this strain is identical to that of the original mutant (Figure 2). This strain, henceforth abbreviated as ΔSHY1, was used in all the studies described here. The null allele (Δshy1::URA3) of W303ΔSHY1/U2 was made by cloning a HindIII fragment containing SHY1 in a modified pUC19 plasmid with a single HindIII site in lieu of the multiple cloning region. This construct was used as a template to delete the entire SHY1 sequence by PCR amplification of the flanking and vector sequences using the two bi-directional primers with SacI sites: 5′-GGCGGAGCTCGCCTAGTAGAGACATTGC and 5′-GGCGGAGCTCGGAAATATATGTAAACGGC. The SacI site was subsequently used to ligate a 1 kb fragment with the yeast URA3 gene. The mss51 null mutant was made by removing an ∼550 bp BglII–BamHI fragment containing the N-terminal half of the gene and substituting it with a 1 kb fragment containing the yeast HIS3 gene (Figure 3). Both the Δmss51::HIS3 and the Δshy1::URA3 alleles were recovered as linear fragments and substituted by the one-step gene replacement method for the respective wild-type genes in the respiratory-competent diploid strain W303 (Rothstein, 1983). Haploid progeny with the mutant alleles were recovered following sporulation of the diploid transformants. The double mutant W303ΔSHY1ΔMSS51 was obtained from a cross of the single mutants, followed by sporulation of the diploid cells and selection of haploid meiotic progeny with the appropriate markers.

Cloning and sequencing of the suppressor gene

A genomic library was constructed by ligating partial Sau3A fragments (7–10 kb) of nuclear DNA from the revertant W303ΔSHY1/R1 to the BamHI site of pRS315 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The library, consisting of ∼20 000 clones, was used to transform W303ΔSHY1/U2 and aW303ΔSHY1/U2 by the procedure of Schiestl and Gietz (1989). The respiratory-competent and leucine-prototrophic phenotypes of several clones obtained from the transformation co-segregated, indicating their dependence on autonomously replicating plasmids. Plasmid pSG91/T1, isolated from one of the transformants, was used to subclone MSS51 (Figure 3). The following primers were used to sequence the suppressor mutations in MSS51 in pSG91/ST6: MSS51-F1, 5′-CAGAACACTGTAGATTGCG; MSS51-F2, 5′-GGCAAAGATATTAACTACAC; MSS51-F3, 5′-CGTGCTGAAGCTCAATTGC; MSS51-R1, 5′-CCTGACAGAGGACAAGTGTAG; MSS51-R2, 5′-GGCAATTGAGCTTCAGCACG; MSS51-R3, 5′-GATGAAAGTTGGGCATGGC. Wild-type MSS51 was also cloned in the integrative plasmid YIp351 (pSG91/ST9) and in the multicopy plasmid YE24 (pG82/T1).

Measurements of oxidative phosphorylation

Mitochondria were prepared by the method of Faye et al. (1974), except that zymolyase 20000 instead of glusulase was used to digest the cell wall. Mitochondria used to measure phosphorylation were washed and stored in buffers containing 1 mg/ml defatted bovine serum albumin. The phosphorylation efficiency, or the ratio of micromoles of Pi esterified per microatom of oxygen utilized (P/O), was measured by the method of Beyer (1964). Briefly, oxygen consumed during the oxidation of succinate by mitochondria was monitored polarographically. The amount of ATP produced was determined from the amount of inorganic 32P appearing in an esterified form.

Mitochondrial protein synthesis, in vivo and in organello

The following procedure was used for in vivo labeling of mitochondria (K.Hell, personal communication). Cells were grown to an absorbance of 1–2 at 600 nm in 10 ml of medium containing yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% galactose and the appropriate prototrophic requirements. Cells equivalent to an A600 of 0.5 were harvested, pelleted by centrifugation, washed with 500 µl of 40 mM potassium phosphate pH 6 containing 2% galactose and resuspended in 500 µl of the same buffer. After incubation for 10 min at 30°C, 10 µl of a freshly prepared aqueous solution of cycloheximide (7.5 mg/ml) were added to inhibit cytoplasmic protein synthesis. The cells were incubated at 30°C for 2.5 min and 4 µl of [35S]methionine (10 Ci/ml) added. The reactions were terminated by addition of 500 µl of 20 mM methionine followed by 75 µl of a mixture containing 1.8 M NaOH, 1 M β-mercaptoethanol and 0.01 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Proteins were precipitated by addition of an equal volume of 50% TCA. The mixture was centrifuged and the pellet washed once with 0.5 M Tris micro base, twice with water, and resuspended in 50 µl of sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970).

Mitochondria prepared by the method of Herrmann et al. (1994) were used to label mitochondrial translation products with [35S]methionine as described (Hell et al., 2000) for 5, 10, 20 min and 1 h. The radiolabeled proteins were separated on a 17.5% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose and visualized by exposure to Kodak X-OMAT film.

Miscellaneous procedures

Standard procedures were used for the preparation and ligation of DNA fragments, and for transformation and recovery of plasmid DNA from E.coli (Maniatis et al., 1982). The preparation of yeast nuclear DNA and the conditions for the northern hybridizations were as described by Myers et al. (1985). Proteins were separated by PAGE in the buffer system of Laemmli (1970), and western blots were treated with antibodies against the appropriate proteins followed by a second reaction with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used for the final detection.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH research grant GM50187, and by a grant MDACU01991001 from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to A.B.).

References

- Beyer R.E. (1964) A protein factor required for phosphorylation coupled to electron flow between reduced coenzyme Q and cytochrome c in the electron transfer chain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 16, 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet Y., Wostrikoff,K., Rimbault,B., Zito,F., Girard-Bascou,J., Drapier,D. and Wollman,F.A. (2001) Assembly-controlled regulation of chloroplast gene translation. Biochem Soc. Trans., 29, 421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen M.J., van den Heuvel,L.P., Nijtmans,L.G., Morava,E., Marquardt,I., Girschick,H.J., Trijbels,F.J., Grivell,L.A. and Smeitink, J.A. (1999) SURFEIT-1 gene analysis and two-dimensional blue native gel electrophoresis in cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 265, 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M.C., Seaver,E.C. and Fox,T.D. (1989) The PET54 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: characterization of a nuclear gene encoding a mitochondrial translational activator and subcellular localization of its product. Genetics, 122, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decoster E., Simon,M., Hatat,D. and Faye,G. (1990) The MSS51 gene product is required for the translation of the COX1 mRNA in yeast mitochondria. Mol. Gen. Genet., 224, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S. and De Vivo,D.C. (1996) Genetic heterogeneity in Leigh syndrome. Ann. Neurol., 40, 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye G. and Simon,M. (1983) Analysis of a yeast nuclear gene involved in the maturation of mitochondrial pre-messenger RNA of the cytochrome oxidase subunit I. Cell, 32, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye G., Kujawa,C. and Fukuhara,H. (1974) Physical and genetic organization of petite and grande yeast mitochondrial DNA. IV. In vivo transcription products of mitochondrial DNA and localization of 23 S ribosomal RNA in petite mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol., 88, 185–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glerum D.M. and Tzagoloff,A. (1998) Affinity purification of yeast cytochrome oxidase with biotinylated subunits 4, 5, or 6. Anal. Biochem., 260, 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glerum D.M., Shtanko,A. and Tzagoloff,A. (1996) Characterization of COX17, a yeast gene involved in copper metabolism and assembly of cytochrome oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 14504–14509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffter P. and Fox,T.D. (1992) Suppression of carboxy-terminal truncations of the yeast mitochondrial mRNA-specific translational activator PET122 by mutations in two new genes, MRP17 and PET127. Mol. Gen. Genet., 235, 64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell K., Tzagoloff,A., Neupert,W. and Stuart,R.A. (2000) Identification of Cox20p, a novel protein involved in the maturation and assembly of cytochrome oxidase subunit 2. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 4571–4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell K., Neupert,W. and Stuart,R.A. (2001) Oxa1p acts as a general membrane insertion machinery for proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J., 20, 1281–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J.E., Myers,A.M., Koerner,T.J. and Tzagoloff,A. (1986) Yeast/E.coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast, 2, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J.M., Foelsch,H., Neupert,W. and Stuart,R.A. (1994) Isolation of yeast mitochondria and study of mitochondrial protein translation. In Celis,J.E. (ed.), Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook. Vol. I. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 538–544.

- Kyte J. and Doolittle,R.F. (1982) A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol., 157, 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh D. (1951) Subacute necrotizing encephalomyelopathy in an infant. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 14, 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T., Fritsch,E.F. and Sambrook,J. (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Martin R.G. and Ames,B.N. (1961) A method for determining the sedimentation behavior of enzymes: application to protein mixtures. J. Biol. Chem., 236, 1372–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashkevich G., Repetto,B., Glerum,D.M., Jin,C. and Tzagoloff,A. (1997) SHY1, the yeast homolog of the mammalian SURF-1 gene, encodes a mitochondrial protein required for respiration. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 14356–14364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroff I. and Tzagoloff,A. (1990) CBP7 codes for a co-factor required in conjunction with a mitochondrial maturase for splicing of its cognate intervening sequence. EMBO J., 9, 2765–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A.M., Pape,L.K. and Tzagoloff,A. (1985) Mitochondrial protein synthesis is required for maintenance of intact mitochondrial genomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J., 4, 2087–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijtmans L.G., Artal Sanz,M., Bucko,M., Farhoud,M.H., Feenstra,M., Hakkaart,G.A., Zeviani,M. and Grivell,L.A. (2001) Shy1p occurs in a high molecular weight complex and is required for efficient assembly of cytochrome c oxidase in yeast. FEBS Lett., 498, 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutre C.G. and Fox,T.D. (1987) PET111, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae nuclear gene required for translation of the mitochondrial mRNA encoding cytochrome c oxidase subunit II. Genetics, 115, 637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyau A., Buchet,K. and Godinot,C. (1999) Sequence conservation from human to prokaryotes of Surf1, a protein involved in cytochrome c oxidase assembly, deficient in Leigh syndrome. FEBS Lett., 462, 416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S., Blok,R.B., Dahl,H.H., Danks,D.M., Kirby,D.M., Chow, C.W., Christodoulou,J. and Thorburn,D.R. (1996) Leigh syndrome: clinical features and biochemical and DNA abnormalities. Ann. Neurol., 39, 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rödel G., Korte,A. and Kaudewitz,F. (1985) Mitochondrial suppression of a yeast nuclear mutation which affects the translation of the mitochondrial apocytochrome b transcript. Curr. Genet., 9, 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R.J. (1983) One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol., 101, 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiestl R.H. and Gietz,R.D. (1989) High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr. Genet., 16, 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siep M., van Oosterum,K., Neufeglise,H., van der Spek,H. and Grivell,L.A. (2000) Mss51p, a putative translational activator of cytochrome c oxidase subunit-1 (COX1) mRNA, is required for synthesis of Cox1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet., 37, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R.S. and Hieter,P. (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 122, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza R.L., Green-Willms,N.S., Fox,T.D., Tzagoloff,A. and Nobrega,F.G. (2000) Cloning and characterization of COX18, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae PET gene required for the assembly of cytochrome oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 14898–14902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Berge A.M., Zoutewelle,G. and Needleman,R.B. (1974) Regulation of maltose fermentation in Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. 3. Constitutive mutations at the MAL6-locus and suppressors changing a constitutive phenotype into a maltose negative phenotype. Mol. Gen. Genet., 131, 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiranti V. et al. (1998) Mutations of SURF-1 in Leigh disease associated with cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 63, 1609–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiranti V., Galimberti,C., Nijtmans,L., Bovolenta,S., Perini,M.P. and Zeviani,M. (1999) Characterization of SURF-1 expression and Surf-1p function in normal and disease conditions. Hum. Mol. Genet., 8, 2533–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzagoloff A. (1971) Assembly of the mitochondrial membrane system. Role of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic protein synthesis in the biosynthesis of the rutamycin-sensitive adenosine triphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem., 246, 3050–3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzagoloff A., Akai,A. and Needleman,R.B. (1975) Assembly of the mitochondrial membrane system. Characterization of nuclear mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with defects in mitochondrial ATPase and respiratory enzymes. J. Biol. Chem., 250, 8228–8235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzagoloff A., Akai,A. and Foury,F. (1976) Assembly of the mitochondrial membrane system XVI. Modified form of the ATPase proteolipid in oligomycin-resistant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett., 65, 391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollman F.A., Minai,L. and Nechushtai,R. (1999) The biogenesis and assembly of photosynthetic proteins in thylakoid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1411, 21–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z. et al. (1998) SURF1, encoding a factor involved in the biogenesis of cytochrome c oxidase, is mutated in Leigh syndrome. Nature Genet., 20, 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]