Abstract

Background

Parathyroid hormone plays a key role in muscle metabolism and function, yet its precise association with sarcopenia remains controversial. This meta-analysis evaluated the relationship between serum parathyroid hormone levels and the risk of sarcopenia.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science until April 2025 for observational studies on the link between parathyroid hormone levels and sarcopenia. Using random-effects models, we derived pooled odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and conducted subgroup analyses. Sensitivity analyses were performed to ensure robustness by excluding small or low-quality studies. Study quality was assessed with modified Newcastle–Ottawa scales, and publication bias was checked using funnel plot symmetry.

Results

This meta-analysis included 11 studies involving 4,759 participants, with mean ages ranging from 57.5 to 76.4 years and 50.37% of participants being female. Our meta-analysis showed a positive association between serum parathyroid hormone levels and the risk of sarcopenia (odds ratios = 1.10, 95% confidence intervals 1.03–1.17, P < 0.001). Subgroup analyses indicated a consistently positive association across diagnostic definitions and study settings, although the effect size was greater in studies using alternative diagnostic criteria (OR = 1.94, 95% confidence intervals 1.21–3.13) and in hospital-based populations (OR = 2.19, 95% confidence intervals 1.27–3.77). Sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of these findings, with no publication bias detected.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggests a potential positive association between elevated parathyroid hormone levels and sarcopenia risk. However, given the substantial heterogeneity and the observational nature of the included studies, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Further large-scale, prospective investigations are warranted to clarify the causal relationship and to explore whether targeting parathyroid hormone could contribute to sarcopenia prevention or management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13018-025-06405-8.

Keywords: Parathyroid hormone, Sarcopenia, Meta-analysis

Background

Sarcopenia, a geriatric syndrome characterized by the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, has increasingly been recognized as a significant health challenge among elderly populations worldwide [1–4]. Emerging evidence indicates that sarcopenia significantly increases the risk of falls, fractures, physical disability, postoperative complications, pain and all-cause mortality, imposing considerable burdens on healthcare systems and society [5–13]. However, there are currently no clearly effective clinical strategies for the treatment of sarcopenia [14]. Despite its clinical significance, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain incompletely understood, with emerging research highlighting endocrine dysregulation as a potentially critical contributor to sarcopenia pathogenesis [15, 16].

Parathyroid hormone (PTH), traditionally recognized for its role in regulating calcium-phosphate homeostasis and bone metabolism [17, 18], has been implicated in musculoskeletal metabolic processes. However, whether PTH exerts beneficial or detrimental effects on muscle remains controversial [19–23]. Mechanistic studies suggest PTH confers protection against muscle atrophy, with proposed mechanisms involving modulation of intracellular calcium dynamics and activation of adenylate cyclase-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-protein kinase A signaling pathway [24–26]. Paradoxically, epidemiological investigations report significant correlations between elevated PTH concentrations and both impaired muscle performance and reduced lean mass indices [27–30]. While considerable research has examined the relationship between PTH and sarcopenia, methodological differences concerning population characteristics, diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, and PTH assay techniques have contributed to inconsistent findings.

Meta-analysis as an effective means to synthesize the existing evidence may help fill this knowledge gap, but to our knowledge, no such study has systematically reviewed current evidence on the association between PTH levels and sarcopenia. Therefore, the aim of this study was to synthesize the accumulating evidence for the relation of PTH levels to sarcopenia risk using meta-analytic techniques.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Additional File 1) [31] and Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (Additional File 2) [32], with corresponding checklists provided in Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2. The analysis protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (registration number CRD420251017088).

Search strategy

Systematic searches were conducted across Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science from inception through April 2025. The search strategy included the following terms: (“Parathyroid Hormone” OR “Parathyroid Hormone” OR “parathormone”) AND ("sarcopenia" OR "sarcopeni*" OR "muscle mass" OR "fat free mass" OR "lean mass" OR "muscle function" OR "Muscle Strength" OR "muscular strength" OR "Muscle Strength" OR "handgrip strength" OR "grip strength" OR "Hand Strength" OR "Hand Strength"). Database-specific syntax adaptations are detailed in Additional File 3. No language restrictions were applied, with non-English articles translated using Google Translate [33]. Duplicate records were removed using EndNote reference manager (EndNote X9, Clarivate), followed by manual screening of reference lists from included studies and relevant reviews to identify additional eligible publications.

Eligibility criteria

Study eligibility followed the PICO framework, as detailed in Additional File 4. Eligible studies met the following criteria: (1) adult participants (≥ 18 years); (2) measured serum/plasma PTH levels as the exposure; (3) higher PTH levels compared with lower PTH levels, as defined within individual studies; (4) outcomes including sarcopenia diagnosis or its diagnostic components (muscle mass, strength, or physical performance); (5) observational designs (cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort studies). Studies were excluded if they were clearly irrelevant to the research question, did not assess PTH as the exposure, did not report sarcopenia or muscle-related outcomes, were non-human, or were case reports, letters, meeting abstracts, cost-effectiveness studies, reviews, or abstracts without full-text data. T

Study selection and data extraction

Following duplicate removal, two investigators independently screened titles/abstracts and subsequently evaluated full texts. Inter-rater agreement was substantial for initial screening (Kappa statistic was 0.85) and perfect for full-text assessment (Kappa statistic was 1.0), with disagreements resolved through consensus. Data extraction employed a standardized table capturing study characteristics including author, publication year, study design, population source and sample characteristics, participant demographics (age, sex and body mass index [BMI]), sarcopenia diagnostic criteria, and effect estimates. Desirable outcomes were explicitly defined as sarcopenia or its diagnostic components, including skeletal muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance.

We extracted the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) from included studies, quantifying the association between the PTH level with the risk of sarcopenia. Where studies reported multiple adjusted models, estimates from the most comprehensively adjusted analyses were prioritized [34]. Corresponding authors were contacted to obtain unreported effect estimates or methodological details.

Quality assessment and certainty of evidence

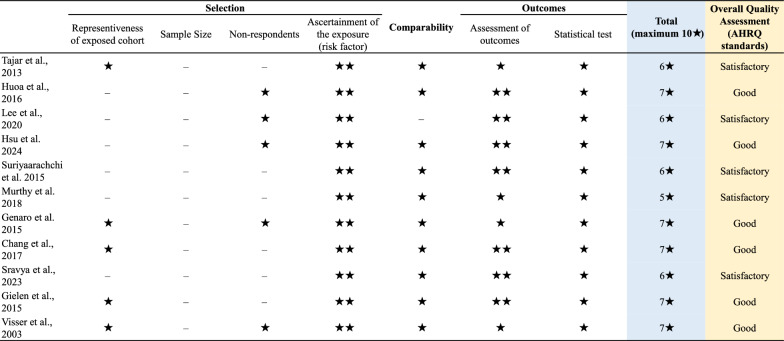

Methodological quality was rigorously evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), with an adapted version applied for cross-sectional studies and the standard version used for cohort studies [35]. The NOS quantifies bias risk across three domains: (1) participant selection (5 points), (2) group comparability (2 points), and (3) outcome/exposure ascertainment (3 points), yielding a maximum 10-star score. Studies were categorized as: unsatisfactory studies (0–4 points), satisfactory studies (5–6 points), good studies (7–8 points), or very good studies (9–10 studies). This quality stratification informed subsequent sensitivity analyses. Two investigators independently evaluated methodological quality. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion; persistent disagreements underwent final arbitration by the corresponding author (Haochen Wang).

Statistical analysis

We extracted ORs quantifying the association between PTH levels and sarcopenia risk. We employed random-effects models for all analyses, which account for potential heterogeneity across studies by assuming distinct yet related underlying effects. This approach yields results comparable to fixed-effects models when heterogeneity is absent while providing broader generalizability to diverse clinical contexts [36, 37]. Between-study variance (τ2) was estimated using the DerSimonian and Laird method. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran's Q test (significance threshold P < 0.05) and quantified via I2 statistics, where values > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity [38].

Subgroup analyses stratified studies by: (1) sarcopenia diagnostic criteria (the diagnostic criteria recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia or the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia vs. other definitions) and (2) population source (general population vs. hospital population) and (3) study design (cross-sectional vs. cohort). Publication bias was assessed through funnel plot symmetry evaluation [39, 40]. To provide a more comprehensive evaluation, Egger’s regression test was conducted to statistically assess small-study effects, and the trim-and-fill method was applied to estimate the potential influence of missing studies on the pooled effect size. Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding small-sample (n < 300) or low-quality studies (as defined by quality assessment) to evaluate result robustness. In addition, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the influence of each individual study on the pooled effect estimate. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) version 3.3.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Funnel plots were generated using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All visualizations were created with R version 4.4.2.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

Systematic searches yielded 2852 citations. Following duplicate removal, 1949 records underwent screening. After excluding 1905 ineligible studies during title and abstract assessment, 44 articles advanced to full-text evaluation. Eventually, eleven studies ultimately met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy employed in the literature search

Study characteristics are detailed in Table 1 and Additional File 5. The 11 included studies enrolled a total of 4759 participants (ranging from 105 to 1,504), with mean ages ranging from 57.5 to 76.4 years, confirming a predominantly elderly cohort. Females constituted 50.37% of participants. Mean BMI exceeded 25 kg/m2 in most studies (81.8%), with only two studies (18.2%) reporting values below this threshold. Four investigations (36.4%) sampled community-dwelling populations, while the majority (63.6%) utilized hospital-based cohorts. Sarcopenia diagnosis employed three different diagnostic criteria: EWGSOP (36.4%), AWGS (27.3%), and low appendicular skeletal muscle mass alone or other diagnostic criteria (36.4%). NOS assessment indicated all studies achieved quality scores ≥ 5, with six (54.5%) rated as good quality (quality scores ≥ 7) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies (N = 11)

| Studies | Study location | Study design | Sample size, n | Sarcopenia diagnosis | Population source | Mean age, SD | Female, % | BMI, SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tajar et al., 2013[30] | UK | Cross-sectional | 1,504 | Frailty status was determined using Fried’s phenotypic definition based on five criteria: exhaustion, weakness, slowness, low activity and sarcopenia | Community-dwelling | 69.4 (5.7) | 0% | 27.8 (4.0) |

| Huoa et al., 2016[29] | Australia | Cross-sectional | 205 | Gait velocity < 80 cm/second, grip strength < 20 kg for females and < 30 kg for males and height adjusted appendicular lean mass (ALM/ht2) < 5.5 kg/m2 (female) and < 7.26 kg/m2 (male) | Hospital (Falls patients) | 76.4 (5.4) | 73% | 34.9 (5.07) |

| Lee et al., 2020[28] | Korea | Cross-sectional | 131 | Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) criteria | Hospital (Hemodialysis patients) | 66.2 (10.5) | 46.8% | 23.3 (2.1) |

| Hsu et al., 2024[52] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 186 | Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) criteria | Hospital (peritoneal dialysis) | 57.5 (14.1) | 53.8% | 25.0 (4.1) |

| Suriyaarachchi et al., 2015[53] | Australia | Cross-sectional | 400 | European Working Group on Sarcopenia criteria | Hospital (falls or fracture) | 79 | 65% | None |

| Murthy et al., 2018[54] | Australia | Cross-sectional | 692 | Frail if they had three or more of the following frailty components: weight loss, weakness/ reduced muscular strength, slow walking speed, exhaustion, and low activity level | Hospital (falls or fracture) | 79 | 65% | 26.3 (3.7) |

| Genaro et al., 2015[55] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 105 | Sarcopenia was defined based on appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASMM) measurements. The cut-off corresponded to 5.45 kg/m2 in women | Community-dwelling | 70.6 | 100% | None |

| Chang et al., 2017[56] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | 449 | European Working Group on Sarcopenia criteria | Community-dwelling | 76.5 (6.2) | 49.60% | 24.1 (3.9) |

| Sravya et al., 2023[57] | India | Cross-sectional | 238 | Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) criteria | Hospital (T2DM patients) | 56.9 (6.0) | 48.70% | 27.2 (3.4) |

| Gielen et al., 2015[58] | Belgium | Cohort | 518 | European Working Group on Sarcopenia criteria | Community-dwelling | 60.0 (10.3) | 0% | 27.2 (3.7) |

| Visser et al., 2003[48] | Netherlands | Cohort | 331 | We defined sarcopenia as a loss of appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASMM) greater than 3% during follow-up | Community-dwelling | 73.9 (6.0) | 52% | 26.6 (4.0) |

SD: Standard Deviation; BMI: Body Mass Index; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus

Fig. 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies using the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale

Association between PTH and sarcopenia

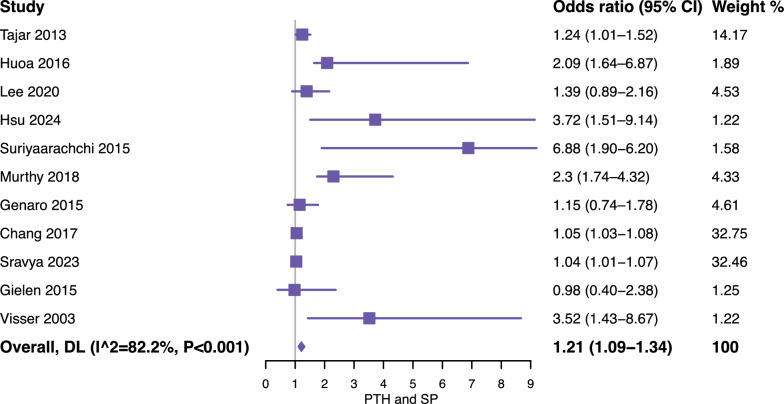

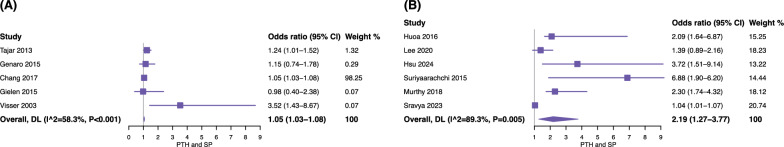

Meta-analysis of 4,759 participants suggested that elevated serum PTH levels may be associated with an increased risk of sarcopenia (OR = 1.21, 95% confidence intervals [CI] = 1.09–1.34). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed across the included studies (I2 = 82.2%), as shown in Fig. 3. Subgroup analyses further stratified studies by sarcopenia diagnostic criteria (EWGSOP or AWGS vs. others) (Fig. 4) and population source (community-dwelling population vs. hospital-based population) (Fig. 5), and the results were reported according to outcomes as follows: (1) for standard diagnostic criteria, the subgroup analysis involved 7 studies and 2,027 participants, and the results showed that the pooled OR = 1.10 (95% CI = 1.00–1.20, I2 = 81.1%) (Fig. 4A); (2) for alternative diagnostic criteria, the subgroup analysis involved 4 studies and 2,732 participants, with a pooled OR of 1.94 (95% CI = 1.21–3.13, I2 = 72.5%) (Fig. 4B); (3) the subgroup analysis of the community-dwelling population included 5 studies with 2,907 participants, with a pooled OR of 1.05 (95% CI = 1.03–1.08, I2 = 58.3%) (Fig. 5A); (4) the results of the hospital-based subgroup analysis, which included 6 studies and 1,852 participants, showed a pooled OR of 2.19 (95% CI = 1.27–3.77, I2 = 89.3%) (Fig. 5B). Subgroup analysis by study design indicated that elevated serum PTH levels were positively associated with increased sarcopenia risk in both study types. Specifically, the pooled odds ratio (OR) for cross-sectional studies was 1.35 (95% CI 1.12–1.62, I2 = 84.0%), and for cohort studies, the pooled OR was 2.24 (95% CI 1.12–4.48, I2 = 87.5%). These findings suggest that the overall association between higher serum PTH levels and sarcopenia risk is consistent across different study designs, and study design did not appear to be a major source of heterogeneity.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the association between parathyroid hormone and risk of sarcopenia. CI, confidence interval; DL, DerSimonian-Laird

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis stratified by definitions based on sarcopenia. A the diagnostic criteria recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia or the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia; B other diagnostic criteria, such as Frailty status. CI, confidence interval; DL, DerSimonian-Laird

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis stratified by population. A general population; B hospital population. CI, confidence interval; DL, DerSimonian-Laird

Sensitivity analyses and Publication bias

Sensitivity analyses restricted to high-quality studies demonstrated consistent findings, with a pooled OR of 2.19 (95% CI 1.27–3.77, I2 = 89.3%) (Fig. 6A), indicating that the association between elevated serum PTH levels and sarcopenia risk remained robust. Similarly, analyses confined to large-sample studies (n ≥ 300) confirmed result stability (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.05–2.39, I2 = 72.5%) (Fig. 6B). Additionally, no single study strongly influenced the overall causal association effects in the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (Additional File 6). These complementary approaches substantiated the robustness of our primary findings.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the sensitivity analysis: excluding studies with A small sample sizes (n < 300) and B studies of lower quality (as determined by the quality assessment). CI, confidence interval; DL, DerSimonian-Laird

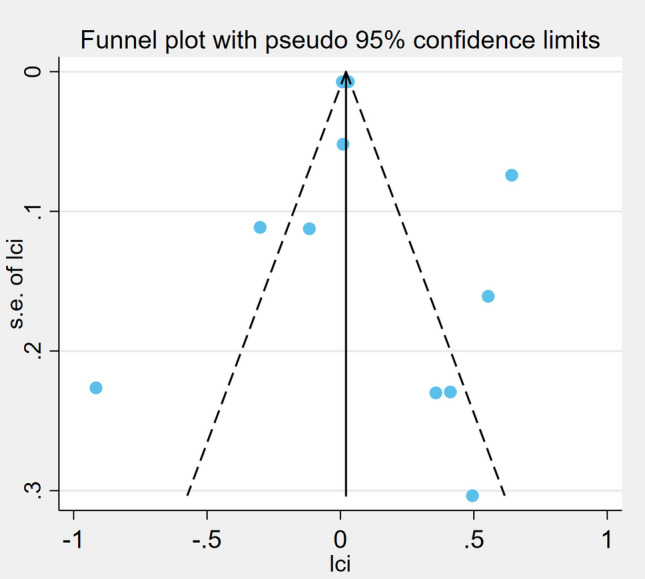

The publication bias was evaluated by a funnel plot, and the funnel plot symmetry indicated no publication bias (Fig. 7). This observation was further supported by Egger’s regression test (P = 0.27), indicating no significant small-study effects. The trim-and-fill analysis did not impute any potentially missing studies, suggesting that publication bias was unlikely to have materially influenced our findings.

Fig. 7.

Funnel plots of publication bias for meta-analysis of parathyroid hormone for sarcopenia

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis, 11 observational studies involving a total of 4759 participants were identified. This meta-analysis explored the association of PTH level and sarcopenia, suggested that higher serum PTH levels may be associated with an increased odd of sarcopenia. Moreover, the subgroup analysis (standard diagnostic criteria vs. alternative diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia; the general-based population vs. hospital-based population) and sensitivity analysis further confirmed that this outcome has good stability. However, given the substantial heterogeneity observed, these findings should be interpreted with caution and regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

PTH plays a crucial role in regulating calcium and phosphorus metabolism, with abnormal secretion potentially triggering metabolic disorders. PTH primarily mediates calcium-phosphate homeostasis through receptor interactions in renal and osseous tissues [41, 42]. Significantly, bones and skeletal muscles maintain anatomical and biochemical connections that establish a cohesive physiological system. Elevated serum PTH levels appear to impair skeletal muscle metabolism, as evidenced by the association between primary hyperparathyroidism and muscular dysfunction [43]. Therefore, PTH might also have substantial impacts on skeletal muscle. Although the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood, several ways may explain PTH's contribution to sarcopenia pathogenesis. First, given calcium’s established role in muscle contraction, PTH-mediated alterations in serum calcium represent the most direct pathway influencing skeletal muscle [44]. Second, both intact PTH and its N-terminal fragments modulate muscle protein metabolism by promoting proteolysis and increasing alanine/glutamine release, thereby perturbing amino acid metabolism [45]. Additionally, the metabolic effects of PTH may also indirectly impact muscle mass by affecting the energy metabolism of skeletal muscle [46]. Studies have shown that PTH can promote the browning of adipose tissue and energy expenditure by activating the protein kinase A pathway, a process linked to muscle consumption [47]. Finally, sarcopenia is characterized by age-associated declines in muscle strength and mass. Current hypotheses propose that age-related hormonal alterations may drive these degenerative changes, with circulating PTH concentrations demonstrating progressive increases with advancing age [48].

It is interesting to note that, while substantial clinical evidence has indicated the effects of PTH on skeletal muscle tissue, the underlying mechanisms of its biological impact on skeletal muscle remain poorly understood, with limited and contradictory evidence from basic in vitro studies. Preclinical studies demonstrate its capacity to simultaneously improve bone mineral density and skeletal muscle mass in osteoporosis models [49], while combinatorial therapies show enhanced efficacy against osteosarcopenia [50]. Meanwhile, research has also demonstrated the role of PTH in skeletal muscle regeneration. A study using mouse cell models has shown that PTH exhibits protective effects and plays a significant role in inducing muscle cell differentiation, accelerating myogenesis, and promoting myotube formation [51]. Despite methodological constraints inherent in preclinical investigations, characterized by exploratory study designs with limited observation windows and heterogeneous application of experimental protocols, the findings nonetheless provide novel mechanistic insights into the reciprocal regulatory relationship between PTH and sarcopenia. To arrive at solid conclusions, further large-scale prospective clinical studies, high-quality randomized controlled trials and meticulously planned basic research are essential.

To our knowledge, this work provides the most current quantitative assessment of the PTH-sarcopenia association in aging populations. However, our work was also subjected to several limitations. Initially, a significant number of the studies included were cross-sectional, which limits the ability to draw causal conclusions from our analysis. Therefore, the results need further confirmation through longitudinal or interventional research. Second, the number of included studies is limited, and the sample size is small. Our analysis results may be influenced by the limited sample size of the studies considered, and this situation may change as more evidence accumulates. Finally, substantial heterogeneity was observed in certain groups. Our subgroup analyses suggested that definition of diagnostic criteria and population source may not be the primary source of heterogeneity. Notably, studies using alternative diagnostic criteria or hospital-based populations exhibited higher odds of sarcopenia, which may reflect differences in case definition sensitivity, a higher baseline burden of comorbidities, or the inclusion of patients with more severe underlying conditions. These factors could contribute to the observed variability in risk estimates, while overall sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the primary findings. Therefore, further data are necessary to determine the potential origin of heterogeneity.

In this study, a positive association between elevated serum PTH levels and the increased risk of sarcopenia. Based on this, strategies managing PTH and parathyroid function are expected to play a preventive role in skeletal muscle health. Caution should be exercised when developing hormonal intervention recommendations for the elderly from the perspective of skeletal muscle loss management, with PTH requiring careful consideration. Our findings further suggest that PTH may serve as a predictive biomarker for assessing the risk of sarcopenia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis indicates a positive association between serum PTH levels and sarcopenia risk. These findings raise the possibility that PTH may serve as a modifiable risk factor and potential biomarker for sarcopenia. However, large-scale prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials are needed to validate and extend these findings before clinical recommendations can be made.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Everyone who contributed significantly to the work has been listed.

Disclaimer

The interpretation of these data is the sole responsibility of the authors.

Abbreviations

- PTH

Parathyroid hormone

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- MOOSE

Meta-analyses of observational studies in epidemiology

- BMI

Body mass index

- ORs

Odds ratios

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- CI

Confidence intervals

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Junyu Zhu and Haochen Wang Data curation: Junyu Zhu and Haochen Wang Formal analysis: Junyu Zhu and Haochen Wang Funding acquisition: Mingjie Shao Investigation: Junyu Zhu and Haochen Wang Methodology: Junyu Zhu and Haochen Wang Project administration: Haochen Wang Resources: Haochen Wang Software: Junyu Zhu and Liang Zhang Supervision: Haochen Wang Validation: Junyu Zhu, Liang Zhang and Mingjie Shao Visualization: Junyu Zhu, Liang Zhang and Mingjie Shao Writing – original draft: Junyu Zhu Writing – review and editing: Haochen Wang.

Funding

Hunan Natural Science Foundation–Outstanding Youth Foundation (2022JJ20099). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No competing interests. Transparency The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayer AA, Cooper R, Arai H, Cawthon PM, Ntsama Essomba MJ, Fielding RA, et al. Sarcopenia Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narici MV, Maffulli N. Sarcopenia: characteristics, mechanisms and functional significance. Br Med Bull. 2010;95:139–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YP, Kuo YJ, Hung SW, Wen TW, Chien PC, Chiang MH, et al. Loss of skeletal muscle mass can be predicted by sarcopenia and reflects poor functional recovery at one year after surgery for geriatric hip fractures. Injury. 2021;52(11):3446–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li C, Ji H, Cui D, Zhuang S, Zhang C. Association between sarcopenia on residual back pain after percutaneous kyphoplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng QY, Qin Y, Shi Y, Mu XY, Huang SJ, Yang YH, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in sarcopenia: a study from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2018. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1376544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gielen E, Dupont J, Dejaeger M, Laurent MR. Sarcopenia, osteoporosis and frailty. Metabolism. 2023;145:155638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson L, Degens H, Li M, Salviati L, Lee YI, Thompson W, et al. Sarcopenia: aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):427–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Peng L, You M, Shen B, Li J. Real-time multicomponent remote rehabilitation versus self-rehabilitation for sarcopenia: a randomized controlled trial protocol. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahran DG, Khalifa AA, Abdelhafeez AH, Farouk O. Sarcopenia and its associated factors among hip fracture patients admitted to a North African (Egyptian) Level one trauma center, a cross-sectional study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong RMY, Wong PY, Chau WW, Liu C, Zhang N, Cheung WH. Very high prevalence of osteosarcopenia in hip fracture patients: risk and protective factors. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu W, Duan F, Liu Z, Yang G, Li C, Wang R, et al. BMI-stratified cutoff values for spinal sarcopenia in Chinese adults based on CT measures: a multicentre study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao D, Fan M, Zhang W, Ma X, Wang H, Gao X, et al. The risk factors for low back pain following oblique lateral interbody fusion: focus on sarcopenia. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khani Y, Salmani A, Elahi M, Elahi Vahed I, Sadooghi Rad E, Bahrami Samani A, et al. Peri-operative protein or amino acid supplementation for total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gungor O, Ulu S, Hasbal NB, Anker SD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Effects of hormonal changes on sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: where are we now and what can we do?. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(6):1380–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing D, Liu F, Gao Y, Fei Z, Zha Y. Texture analysis of T1- and T2-weighted images identifies myofiber atrophy and grip strength decline in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic sarcopenia rats. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esbrit P, Alcaraz MJ. Current perspectives on parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related protein (PTHrP) as bone anabolic therapies. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(10):1417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goltzman D. Physiology of parathyroid hormone. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47(4):743–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somjen D, Weisman Y, Kohen F, Gayer B, Limor R, Sharon O, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D3–1alpha-hydroxylase is expressed in human vascular smooth muscle cells and is upregulated by parathyroid hormone and estrogenic compounds. Circulation. 2005;111(13):1666–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abboud M, Rybchyn MS, Liu J, Ning Y, Gordon-Thomson C, Brennan-Speranza TC, et al. The effect of parathyroid hormone on the uptake and retention of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in skeletal muscle cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujimaki T, Ando T, Hata T, Takayama Y, Ohba T, Ichikawa J, et al. Exogenous parathyroid hormone attenuates ovariectomy-induced skeletal muscle weakness in vivo. Bone. 2021;151:116029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Sun S, Zhou X, He M, Li Y, Liu C, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and parathyroid hormone improve muscle atrophy in estrogen deficiency mice. Ultrasonics. 2023;132:106984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iio R, Manaka T, Takada N, Orita K, Nakazawa K, Hirakawa Y, et al. Parathyroid hormone inhibits fatty infiltration and muscle atrophy after rotator cuff tear by browning of fibroadipogenic progenitors in a rodent model. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(12):3251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha P, Aarnisalo P, Chubb R, Poulton IJ, Guo J, Nachtrab G, et al. Loss of gsalpha in the postnatal skeleton leads to low bone mass and a blunted response to anabolic parathyroid hormone therapy. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(4):1631–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark LJ, Krieger J, White AD, Bondarenko V, Lei S, Fang F, et al. Allosteric interactions in the parathyroid hormone GPCR-arrestin complex formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16(10):1096–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutkeviciute I, Clark LJ, White AD, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP. PTH/PTHrP receptor signaling, allostery, and structures. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019;30(11):860–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin YL, Liou HH, Lai YH, Wang CH, Kuo CH, Chen SY, et al. Decreased serum fatty acid binding protein 4 concentrations are associated with sarcopenia in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;485:113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H, Kim K, Ahn J, Lee DR, Lee JH, Hwang SD. Association of nutritional status with osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and cognitive impairment in patients on hemodialysis. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29(4):712–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huo YR, Suriyaarachchi P, Gomez F, Curcio CL, Boersma D, Gunawardene P, et al. Phenotype of sarcopenic obesity in older individuals with a history of falling. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;65:255–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tajar A, Lee DM, Pye SR, O’Connell MD, Ravindrarajah R, Gielen E, et al. The association of frailty with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels in older European men. Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):352–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of google translate for abstracting data from non-english-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):677–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riva JJ, Noor ST, Wang L, Ashoorion V, Foroutan F, Sadeghirad B, et al. predictors of prolonged opioid use after initial prescription for acute musculoskeletal injuries in adults : a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):721–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells GA OCD, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if Nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses.

- 36.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Fixed or random effects meta-analysis? common methodological issues in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(6):676–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mannstadt M, Bilezikian JP, Thakker RV, Hannan FM, Clarke BL, Rejnmark L, et al. Hypoparathyroidism Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergwitz C, Juppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:91–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bislev LS, Langagergaard Rodbro L, Sikjaer T, Rejnmark L. Effects of elevated parathyroid hormone levels on muscle health, postural stability and quality of life in vitamin d-insufficient healthy women: a cross-sectional study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019;105(6):642–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berchtold MW, Brinkmeier H, Muntener M. Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity, and disease. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(3):1215–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baczynski R, Massry SG, Magott M, el-Belbessi S, Kohan R, Brautbar N. Effect of parathyroid hormone on energy metabolism of skeletal muscle. Kidney Int. 1985;28(5):722–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Rendina-Ruedy E, Rosen CJ. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) regulation of metabolic homeostasis: An old dog teaches us new tricks. Mol Metab. 2022;60:101480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas SS, Mitch WE. Parathyroid hormone stimulates adipose tissue browning: a pathway to muscle wasting. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017;20(3):153–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P, Longitudinal Aging Study A. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5766–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Sato C, Miyakoshi N, Kasukawa Y, Nozaka K, Tsuchie H, Nagahata I, et al. Teriparatide and exercise improve bone, skeletal muscle, and fat parameters in ovariectomized and tail-suspended rats. J Bone Miner Metab. 2021;39(3):385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brent MB, Bruel A, Thomsen JS. PTH (1–34) and growth hormone in prevention of disuse osteopenia and sarcopenia in rats. Bone. 2018;110:244–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimura S, Yoshioka K. Parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone type-1 receptor accelerate myocyte differentiation. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsu BG, Wang CH, Tsai JP, Chen YH, Hung SC, Lin YL. Association of serum intact parathyroid hormone levels with sarcopenia in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1487449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suriyaarachchi P, Gomez F, Curcio CL, Boersma D, Murthy L, Grill V, et al. High parathyroid hormone levels are associated with osteosarcopenia in older individuals with a history of falling. Maturitas. 2018;113:21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murthy L, Dreyer P, Suriyaarachchi P, Gomez F, Curcio CL, Boersma D, et al. association between high levels of parathyroid hormone and frailty: The Nepean Osteoporosis and Frailty (NOF) study. J Frailty Aging. 2018;7(4):253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Souza GP, de Medeiros PM, Szejnfeld VL, Martini LA. Secondary hyperparathyroidism and its relationship with sarcopenia in elderly women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(2):349–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang WT, Wu CH, Hsu LW, Chen PW, Yu JR, Chang CS, et al. Serum vitamin D, intact parathyroid hormone, and Fetuin A concentrations were associated with geriatric sarcopenia and cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sravya SL, Swain J, Sahoo AK, Mangaraj S, Kanwar J, Jadhao P, et al. Sarcopenia in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: study of the modifiable risk factors involved. J Clin Med. 2023;12(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Gielen E, O’Neill TW, Pye SR, Adams JE, Wu FC, Laurent MR, et al. Endocrine determinants of incident sarcopenia in middle-aged and elderly European men. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015;6(3):242–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.