Abstract

Dual SMAD inhibition is a robust and widely adopted protocol for directing human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) toward neuronal lineages by blocking transforming growth factor–beta and bone morphogenetic protein pathways. Suppressing transforming growth factor–beta and bone morphogenetic protein signaling enables efficient and reproducible induction of neuroectoderm, serving as the foundation for generating diverse brain region–specific neuronal subtypes. This review outlines the mechanistic basis and major achievements of the dual SMAD inhibition strategy, including its application in 2 recent clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease, and its role in preclinical studies targeting conditions, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), retinal degeneration, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In addition to its significant contribution to the generation of transplantation-ready grafts from hPSCs, the protocol serves as a valuable platform for disease modeling across various neurological and metabolic disorders. The key strengths include high efficiency, technical simplicity that enables precise control of cell fate using small molecules, versatility in both 2- and 3-dimensional culture systems, and reproducibility across various hPSC lines. This review also addresses key limitations, such as restricted gliogenic capacity and limited neural progenitor cell expansion. Future research should focus on incorporating emerging technologies to advance stem cell–based applications. Overall, dual SMAD inhibition represents a powerful and versatile platform for stem cell–based neuroscience and regenerative medicine.

Keywords: Disease modeling, Human pluripotent stem cells, Neuronal differentiation, Regenerative medicine, Signal pathway

INTRODUCTION

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) can differentiate into virtually all cell types in the human body, making them invaluable platforms for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and developmental biology (Simonson et al., 2015, Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006, Thomson et al., 1998, Zhu and Huangfu, 2013). Early success in clinical transplantation of fetal ventral midbrain tissue in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) provided a proof-of-concept for cell replacement therapy (Kordower et al., 1995, Lindvall et al., 1990). However, this approach is limited by ethical concerns, donor scarcity, and variability in tissue quality (Turner and Kearney, 1993). Consequently, the generation of functionally equivalent cells from renewable and ethically acceptable sources such as pluripotent stem cells has emerged as a central objective in stem cell research. The invention of hiPSC technology has broadened the scope of stem cell applications in patient-specific disease modeling and personalized medicine (Rowe and Daley, 2019). Guiding the differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into specific functional cell types is critical for therapeutic and investigative applications. In neuroscience, achieving reliable and efficient neuronal differentiation is a major technological challenge.

Initial protocols for generating neurons from embryonic stem cells were developed using mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) through embryoid body (EB) formation or stromal cell coculture (Kawasaki et al., 2000, Lee et al., 2000). Early attempts to translate these murine protocols to hESCs showed promise but struggled to produce neuronal populations meeting the rigorous standards for clinical applications (Perrier et al., 2004, Yan et al., 2005). This limitation was later attributed to fundamental differences in the pluripotency states between mESCs and hESCs, with mESCs in a naive pluripotency stage, whereas hESCs are in primed pluripotency stages resembling murine postimplantation stages (Weinberger et al., 2016). The use of murine feeder cells in stromal cell cocultures raises safety concerns due to the risk of xenogenic contamination, emphasizing the need for human-specific, feeder-free differentiation strategies for clinical translation.

The introduction of the dual SMAD inhibition protocol was a major turning point. By simultaneously inhibiting bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and transforming growth factor–beta (TGF-β)/Activin/Nodal pathways, this method directs hPSCs toward a neuroectodermal fate with high efficiency and purity (Chambers et al., 2009, Wattanapanitch et al., 2014). This has become a foundational protocol for human neuronal differentiation that has enabled significant breakthroughs in stem cell research. Two recent Nature studies reported successful Phase I clinical trials of hPSC-derived midbrain dopamine neurons (mDAs) in patients with PD using protocols based on dual SMAD inhibition (Sawamoto et al., 2025, Tabar et al., 2025). This protocol has also supported the generation of diverse neuronal subtypes for a broad range of applications, including preclinical and clinical transplantation, disease modeling, and developmental studies (Kim et al., 2023, Macečková Brymová et al., 2025, Park et al., 2024, Sun et al., 2024).

This review aims to elucidate the core features and underlying mechanisms of the dual SMAD inhibition protocol and summarize its key achievements. These include its role as a foundational strategy for brain region–specific differentiation protocols, translational potential in generating grafts for disease treatment, and contribution to modeling human development and disease. Finally, we critically assess the current limitations of this protocol and propose future directions for advancing hPSC-based differentiation strategies.

MECHANISM OF DUAL SMAD INHIBITION IN NEURONAL DIFFERENTIATION FROM HPSCS

The dual SMAD inhibition protocol represents a cornerstone method for efficiently directing hPSCs toward a neuronal lineage. This strategy builds upon insights from developmental biology, particularly the understanding of key signaling pathways—TGF-β and BMP—that are critical for lineage specification of pluripotent cells. By precisely modulating these signals, dual SMAD inhibition selectively promotes ectodermal differentiation while suppressing alternative mesodermal and endodermal fates (Chambers et al., 2009).

During embryonic development, the formation of the 3 germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm—is orchestrated by a complex interplay of signaling pathways, primarily those of the WNT/β-catenin, FGF, TGF-β, and BMP families (Kiecker et al., 2016, Ozair et al., 2013). These pathways act in a spatiotemporally regulated manner to initiate lineage specification. Even though FGF signaling does not directly induce mesoderm, it helps establish cellular competence to respond to TGF-β cues. Meanwhile, canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling establishes dorsal identity and initiates the expression of early Nodal genes, indirectly contributing to mesendoderm induction. TGF-β/Activin/Nodal signaling is central to mesendoderm induction through the activation of SMAD2/3. A high level of TGF-β activation promotes endoderm, while an intermediate level induces mesodermal fate. Although the regulation of the dorso-ventral patterning of the mesoderm is considered the primary role of BMP signaling, it also exhibits weak mesoderm-inducing activity through SMAD1/5/8 activation. BMP signaling promotes mesodermal and extraembryonic lineage commitment and represses neural identity within the ectoderm.

During early development, active TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways prevent neuronal differentiation by maintaining pluripotency or diverting cells toward mesodermal and endodermal lineages (Wattanapanitch et al., 2014). The dual SMAD inhibition protocol induces neuronal fate in hPSCs by simultaneously blocking both pathways, thereby eliminating the signals necessary for pluripotency and mesendodermal fate induction. TGF-β and BMP pathways converge on a common intracellular signaling module, the SMAD proteins, which transmit extracellular signals to the nucleus upon their phosphorylation (Wrana, 2000). Phosphorylated SMAD proteins form a complex with SMAD4 and translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate gene expression.

A cell-permeable small molecule, SB431542, inhibits TGF-β signaling by selectively targeting Activin receptor–like kinases ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7, thereby suppressing SMAD2/3 activation and its downstream events (Ozair et al., 2013). Noggin, an endogenous BMP antagonist, binds to and sequesters BMP ligands, preventing them from binding to BMP receptors (Böhnke et al., 2022). In addition to Noggin, chemical replacements are often used because of their greater reproducibility, higher purity, and lower cost than recombinant Noggin. Synthetic small-molecule inhibitors, such as dorsomorphin and its more potent analog, LDN193189, inhibit the intracellular BMP pathway by targeting ALK2/3/6 receptors, thereby blocking the phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 (Cuny et al., 2008).

The outcome of dual SMAD inhibition is the robust and reproducible induction of the neural fate (Wattanapanitch et al., 2014). In the absence of TGF-β and BMP signaling, hPSCs exit the pluripotent state and default to a neuroectodermal lineage (Fig. 1). Notably, dual SMAD inhibition not only suppresses mesendodermal differentiation and promotes neural specification but also attenuates cellular proliferation, likely due to the loss of mitogenic input from TGF-β signaling. This contributes to increased homogeneity and purity of the neuronal population and minimizes the risk of residual undifferentiated cells.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the dual SMAD inhibition mechanism for neural induction of human pluripotent stem cells. The TGF-β/Activin/Nodal pathway is inhibited by SB431542 through blockade of ALK4/5/7 receptors, while the BMP pathway is suppressed by Noggin, LDN193189, or dorsomorphin. Noggin inhibits BMP signaling by binding to BMP ligands and preventing their interaction with BMP receptors. In contrast, LDN193189 and dorsomorphin act downstream by directly inhibiting the BMP type I receptors ALK2/3/6. Together, these inhibitors prevent SMAD2/3 and SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation, thereby blocking mesendodermal and pluripotency-associated transcriptional programs and promoting default neural induction.

In conclusion, dual SMAD inhibition provides a robust, mechanistically well-defined protocol for efficient neural differentiation of hPSCs. Through controlled treatment with small molecules, such as SB431542, dorsomorphin, and LDN193189, researchers can obtain a neural progenitor cell (NPC) population from hPSCs with purities above 80% (Chambers et al., 2009). This approach has become indispensable in developmental biology research and holds significant promise for therapeutic applications, including regenerative medicine and disease modeling.

ACHIEVEMENTS

Foundation of Various Brain Region–specific Protocols

The human brain consists of multiple anatomically and functionally distinct regions, each responsible for specialized tasks, such as maintaining body homeostasis, coordinating muscle movement, and forming memories (Marshall and Morriss-Kay, 2004). These regions are populated by diverse neural cell types unique to each brain region and are interconnected through intricate neural circuits. During development, the specification of these regions is orchestrated by distinct sets of patterning cues that guide spatial and temporal differentiation (Jia and Meng, 2021, Liu and Niswander, 2005). This dual SMAD inhibition protocol lays the groundwork for subsequent protocols aimed at generating brain region–specific neuronal subtypes in vitro. In the absence of external patterning cues, neuroectodermal cells derived from dual SMAD inhibition adopt a default anterior (forebrain) identity, predominantly giving rise to cortical neurons (Vallier et al., 2004). Refinement of this protocol significantly improves the purity and yield of cortical neuron differentiation (Dannert et al., 2023).

To generate neuronal populations representative of more caudal brain regions, additional patterning signals must be introduced to guide progenitor fate along the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes. Small molecules that activate the WNT, FGF, and retinoic acid (RA) signaling pathways function as caudalizing agents, shifting their identity toward posterior neural fates (Kudoh et al., 2002, Li et al., 2005, Perrier et al., 2004, Ye et al., 1998). In contrast, sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling promotes ventralization, whereas the canonical WNT and BMP pathways support dorsalization (Tao and Zhang, 2016, Ye et al., 1998). Precise control of the timing and concentration of these cues enables reproducible and regionally defined neural patterns. For example, combining dual SMAD inhibition with graded doses of the WNT pathway agonist CHIR99021 results in dose-dependent regional specification, with lower concentrations preserving forebrain characteristics and higher doses driving differentiation toward midbrain and hindbrain fates (Kirkeby et al., 2012, Lu et al., 2016).

The combination of dual SMAD inhibition with the ventralizing SHH signal has been utilized to generate floor plate populations, which are specialized cells located at the ventral midline of the neural tube. These cells play a crucial role in embryonic development by serving as both progenitors and sources of morphogenetic signals that guide the differentiation of adjacent neural cells (Placzek and Briscoe, 2005). In the midbrain, the floor plate serves as a progenitor of dopamine neurons. Protocols incorporating dual SMAD inhibition, SHH, and caudalizing agents—such as FGF8 and CHIR99021—have been shown to robustly induce the specification of midbrain floor plate identity, which is characterized by coexpression of transcription factors FOXA2 and LMX1A. These populations subsequently mature into functional mDAs, making this strategy highly valuable for PD studies (Kim et al., 2021, Kriks et al., 2011). Furthermore, the combination of dual SMAD inhibition with other signaling molecules has been widely applied to generate other neuronal subtypes (Table 1) such as hypothalamic, serotonin, and motor neurons (Chen et al., 2023, Du et al., 2015, Lu et al., 2016, Merkle et al., 2015, Tao et al., 2024, Valiulahi et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Dual SMAD inhibition–based protocols and targeted pathways for neuronal subtype differentiation

| Cell type Brain region |

Strategy | Signaling pathway | Key markers | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical neurons Telencephalon |

Day 0-9 Day 0-9 |

SB431542 10 µM LDN193189 0.25 µM |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) |

vGLUT1 NMDAR1 GAD67 |

Dannert et al. (2023) |

| Hypothalamic neurons Diencephalon |

Day 0-9 Day 0-9 Day 0-9 Day 2-7 Day 2-7 Day 8-14 |

SB431542 10 µM LDN193189 100 nM XAV939 2 µM SAG 1 µM Purmorphamine 1 µM DAPT 5 µM |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) WNT (i) SHH (a) Notch (i) |

POMC AGRP HCRT |

Chen et al. (2023) |

| Dopamine neurons Mesencephalon |

Day 0-6 Day 0-6 Day 0-6 Day 0-10 |

SB431542 10 μM LDN193189 250 nM SHH 500 ng/ml CHIR99021 0.7 µM (day 0-3); 7.5 µM (day 4-9); 3 µM (day 10) |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) SHH (a) WNT (a) |

FOXA2 LMX1A NURR1 TH |

Kim et al. (2021) |

| Norepinephrine neurons Metencephalon |

Day 0-4 Day 0-5 Day 0-5 Day 6-9 |

SB431542 2 µM DMH1 2 µM CHIR99021 1 µM Activin A 25 ng/ml (day 6-8); 125 ng/ml (day 9) |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) WNT (a) |

NET MAO COMT ADRA2 |

Tao et al. (2024) |

| Rostral serotonin neurons Metencephalon |

Day 0-20 Day 0-20 Day 0-20 Day 7-20 Day 14-20 |

SB431542 2 µM DMH1 2 µM CHIR99021 1.4 µM SHH 1,000 ng/ml FGF4 10 ng/ml |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) WNT (a) SHH (a) FGF (a) |

TPH2 5-HT GATA2 FEV |

Lu et al. (2016) |

| Caudal serotonin neurons Myelencephalon |

Day 0-4 Day 0-9 Day 1-6 Day 1-13 |

SB431542 10 µM LDN193189 200 nM Purmorphamine 2 µM RA 2 µM |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) SHH (a) RA (a) |

TPH2 5-HT GATA3 FEV |

Valiulahi et al. (2021) |

| Motoneurons Spinal cord |

Day 0-12 Day 0-12 Day 6-12 Day 6-12 |

SB431542 2 µM DMH1 2 µM CHIR99021 3 µM RA 0.1 µM Purmorphamine 0.5 µM |

TGF-β (i) BMP (i) WNT (a) SHH (a) RA (a) |

HB9 ISL1 CHAT |

Du et al. (2015) |

(a), activation; (i), inhibition.

The emergence of a wide array of brain region–specific differentiation protocols based on the dual SMAD inhibition strategy underscores its importance in neural induction (Fig. 2). This approach reliably facilitates the generation of regionally defined neuronal subtypes with high precision across diverse spatial identities. Its remarkable versatility, efficiency, and reproducibility make it a pivotal platform for basic neurodevelopmental research and translational applications in disease modeling using hPSCs.

Fig. 2.

Region-specific neuronal subtypes derived from human pluripotent stem cells using dual SMAD inhibition–based protocols. Dual SMAD inhibition alone induces dorsal forebrain cortical neurons, while the addition of specific morphogens, such as SHH, WNT, FGF8, RA, or Activin A, directs differentiation toward distinct neuronal identities, including hypothalamic, midbrain dopamine, hindbrain serotonin and norepinephrine, and spinal cord motor neurons. The combination of signaling cues reflects developmental patterning along the rostro-caudal and dorso-ventral axes of the central nervous system.

Generation of Functional Graft for Transplantation Studies

Building on its foundational role in establishing region-specific neural differentiation protocols, the dual SMAD inhibition strategy has emerged as a pivotal platform for generating reliable and clinically relevant graft sources for transplantation studies. By enabling efficient and reproducible induction of the neuroectoderm from hPSCs, this protocol provides a consistent starting point for producing defined neuronal subtypes suitable for therapeutic applications to treat various diseases. Clinical trials employing hPSC-derived cells generated using dual SMAD inhibition protocols have marked major milestones in the treatment of PD (Sawamoto et al., 2025, Tabar et al., 2025). Beyond PD, dual SMAD inhibition has been utilized in preclinical studies to treat other diseases such as retinal degeneration, ALS, SCI, and epilepsy (Bershteyn et al., 2023, Laperle et al., 2023, Macečková Brymová et al., 2025, Sun et al., 2024).

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra (Puspita et al., 2017). Cell replacement therapies aim to restore the loss of dopamine neurotransmission by transplanting dopamine-producing neurons into the brains of patients (Kordower et al., 1995, Lindvall et al., 1990). Transplantation of fetal midbrain tissue has demonstrated therapeutic potential for PD; however, it faces critical limitations, including ethical concerns, variable clinical outcomes, immunological rejection risks, and adverse effects, such as graft-induced dyskinesia (Barker et al., 2013, Greene et al., 2021). mDAs generated from hPSCs have emerged as a promising alternative to overcome these issues. Extensive preclinical studies using animal models have validated the safety and efficacy of mDA progenitors generated using a dual SMAD inhibition–based protocol as a source of transplants (Kirkeby et al., 2023, Park et al., 2024, Piao et al., 2021). These studies demonstrated successful graft survival, integration, and significant improvement in motor function, paving the way for subsequent clinical trials in patients with PD. A recent preclinical study also explored the possibility of autologous transplantation by assessing the graft potential of hiPSC-derived mDA cells from 4 patients with sporadic PD using a protocol based on dual SMAD inhibition (Jeon et al., 2025). Safety was confirmed across all tested cell lines; however, mDA cells from 1 patient did not lead to behavioral improvements in animal models, highlighting individual variability. Nevertheless, these findings led to the approval of a clinical trial involving 8 patients with sporadic PD, which is set to begin in 2025.

Two recent landmark clinical trials have underscored the safety and feasibility of transplanting dopamine neurons derived from hESCs and hiPSCs using dual SMAD inhibition–based protocol (Sawamoto et al., 2025, Tabar et al., 2025). A Phase I clinical study of hESC-derived dopamine progenitors demonstrated graft survival, dopamine production, and no significant adverse effects. Similarly, a Phase I/II clinical trial employing hiPSC-derived progenitors reported increased dopamine uptake in the putamen, absence of tumorigenicity, and favorable clinical outcomes. These studies signify substantial progress toward establishing hPSC-derived dopamine neuron transplantation as a viable, ethically acceptable, and clinically effective treatment for PD (Sawamoto et al., 2025, Tabar et al., 2025).

Retinal degeneration encompasses a group of diseases characterized by progressive retinal deterioration leading to vision impairment and potential blindness (Sharma and Jaganathan, 2021). The advanced stages of these diseases are characterized by progressive damage or dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. Although currently no effective treatment exists for this condition, several clinical trials have shown visual improvement in patients following transplantation of hPSC-derived RPE cells generated via spontaneous differentiation and EB formation (Mandai et al., 2017, Riemann et al., 2020, Schwartz et al., 2015).

A comprehensive pipeline for developing a clinical-grade RPE patch from hiPSCs was established in 2019, resulting in a triphasic differentiation protocol that incorporates mild dual SMAD and FGF inhibition to enhance RPE induction, followed by WNT or TGF activation and prostaglandin E2 treatment to achieve functional maturation (Sharma et al., 2019, Sharma et al., 2022). The dual SMAD inhibition–based protocol yielded consistent and efficient generation of RPE cells across all hiPSC clones and the absence of residual pluripotent cells. A biodegradable scaffold was used to create a polarized RPE monolayer that closely resembled native RPE and displayed robust epithelial characteristics. As shown in animal models with defective RPE, transplanted RPE patches adhered to the subretinal space, maintained a monolayer architecture, preserved photoreceptors, and improved visual function, with a recent study further demonstrating their survival and integration in immunosuppressed minipigs (Macečková Brymová et al., 2025, Sharma et al., 2022, Sharma et al., 2019). Although RPE cells generated via dual SMAD inhibition have not yet progressed to clinical trials, this protocol demonstrated consistent differentiation efficiency across multiple hiPSC lines and promising outcomes after transplantation (Macečková Brymová et al., 2025).

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord. This degeneration leads to muscle weakness, paralysis, and ultimately, respiratory failure. There is currently no cure for ALS. Current medications can only modestly slow disease progression or alleviate symptoms, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic approaches (Zhang et al., 2025). Two Phase I clinical trials by Mazzini et al. demonstrated the long-term safety and feasibility of transplanting standardized human fetus–derived neural stem cells (NSCs) into patients with ALS. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of NSCs in patients with ALS (Mazzini et al., 2015, Mazzini et al., 2019). Later, a preclinical study transplanted hiPSC-derived NSCs into the spinal cords of SOD1G93A ALS rats (Forostyak et al., 2020). NPC-iPSCs were generated from the IMR90 human fibroblast line by lentiviral reprogramming and were differentiated via dual SMAD inhibition. Transplantation in asymptomatic and early symptomatic rats delayed disease onset, preserved motor neuron populations, and significantly prolonged the lifespan of the treated rats. Notably, the transplanted cells remained largely undifferentiated near the host motor neurons, suggesting a nonreplacement mechanism of action. Another preclinical study developed a clinical-grade hiPSC–derived NPC product engineered to secrete glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), termed iNPC-GDNF (Laperle et al., 2023). Using a dual SMAD inhibition protocol, iNPCs were generated from hiPSCs and were stably transduced with GDNF using a lentiviral vector. In the SOD1G93A ALS rat model, intraspinal transplantation of iNPC-GDNF resulted in robust survival, sustained GDNF production, and significant preservation of motor neurons, without evidence of tumorigenicity.

SCI occurs when the spinal cord is damaged by physical trauma or disease (Ribeiro et al., 2023). Due to the limited regenerative ability of the central nervous system, SCI often leads to permanent disability. Secondary injury is a progressive series of pathological changes that lead to further tissue damage beyond the initial injury site and may occur hours, days, or even weeks after the primary trauma (Ribeiro et al., 2023). The activation of spinal cord NSCs following SCI helps mitigate damage to the surrounding tissues, primarily through the generation of astrocytes, while only a small fraction differentiates into oligodendrocytes and neurons (Li et al., 2023). To address this issue, several cell types have been investigated for SCI treatment, including NSCs, Schwann cells, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, neural crest cells, motor neurons, and mesenchymal stem cells (Gao et al., 2022, Neirinckx et al., 2014, Sun et al., 2024, Zipser et al., 2022).

Motor neurons derived from neuromesodermal progenitors (NMPs) have been suggested for SCI treatment based on an earlier study that identified NMPs as the origin of the spinal cord, opposing the classic hypothesis of a shared origin for the brain and spinal cord (Sun et al., 2024). They first generated self-renewing NMPs by culturing hESCs with dual SMAD inhibitors in combination with CHIR99021, bFGF, and EGF. To differentiate them into motor neurons, NMPs were cultured in the presence of SHH and RA. Transplantation of these motor neurons into SCI model mice resulted in major behavioral improvement after 2 weeks and a higher BMS than in the control 5 weeks after transplantation (Sun et al., 2024). In a separate study, a dual SMAD inhibition strategy was used to generate neural crest cells for transplantation into SCI rat models (Jones et al., 2021). Neural crest cells were generated by lowering the initial cell density to 60% to 80% confluence, in contrast to the near-confluent conditions (∼100%) typically required for neuronal induction (Chambers et al., 2013, Chambers et al., 2009).

Collectively, these clinical and preclinical studies highlight the vital role of dual SMAD inhibition–based protocols in generating safe and effective graft alternatives from hPSCs for transplantation therapies across a wide spectrum of diseases (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the studies reported here specifically evaluated the safety of grafts derived using dual SMAD inhibition or modified protocols, with no observed teratoma formation, thereby supporting their suitability for clinical applications.

Fig. 3.

Applications of dual SMAD inhibition–based differentiation in regenerative medicine. Human pluripotent stem cell–derived neural cells generated via dual SMAD inhibition have advanced to both clinical and preclinical stages across various disorders. Clinical trials are ongoing for Parkinson’s disease using dopamine neurons, while preclinical studies have demonstrated therapeutic potential in models of retinal degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and other conditions using retinal pigment epithelial cells, neural stem cells, motoneurons, and neural crest cells, respectively.

Disease and Developmental Modeling Study

In addition to its potential applications in generating safe and region-specific grafts for transplantation studies, the dual SMAD inhibition protocol has become a crucial tool in human development and disease modeling research. By directing hPSCs toward a neuroectodermal fate, this protocol enables the in vitro reconstruction of early developmental trajectories under defined and reproducible conditions (Chambers et al., 2009). Its capacity to produce highly pure populations of specific neural subtypes makes it an ideal platform for modeling regionally distinct brain development and investigating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying various neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Protocol versatility across hESC and hiPSC lines further enhances its value in patient-specific disease modeling, allowing researchers to uncover pathogenic mechanisms and evaluate therapeutic responses in human-relevant systems.

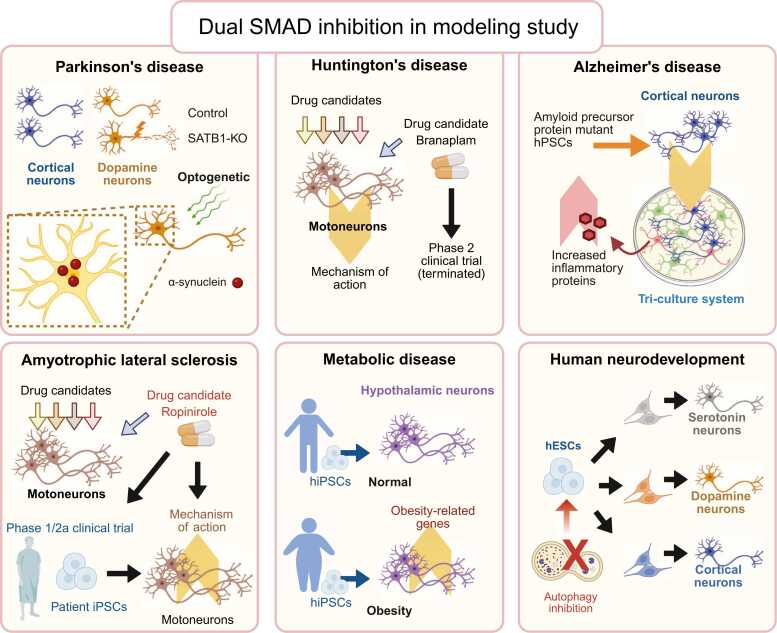

Various derivatives of dual SMAD inhibition protocols have been used to investigate the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases, including PD, ALS, and Huntington’s disease. A study utilizing a SATB1 knockout hESC line—a known genetic risk factor for PD—demonstrated selective induction of cellular senescence in mDA neurons, but not in cortical neurons derived from the same SATB1 knockout line (Riessland et al., 2019). Both neuronal subtypes were generated using derivatives of the dual SMAD inhibition protocol, underscoring the utility of this approach for faithfully modeling the selective vulnerability observed in PD. Another study incorporated an optogenetic approach to accelerate α-synuclein accumulation in dual SMAD inhibition–derived mDA neurons, mimicking age-associated α-synuclein accumulation observed in patients with late-onset PD (Kim et al., 2023, Mazzulli et al., 2011). The high purity of cortical neurons generated via the dual SMAD inhibition protocol enabled the establishment of a triculture system comprising microglia, astrocytes, and cortical neurons, all of which were fully derived from hPSCs carrying mutations in the amyloid precursor protein and their isogenic controls (Guttikonda et al., 2021). This model effectively recapitulated AD-associated neuroinflammation, as demonstrated by the increased expression of the inflammatory protein C3 in astrocytes under pathological conditions.

A major milestone in ALS research is the completion of a phase 1/2a clinical trial evaluating the dopamine D2 receptor agonist ropinirole, which was previously identified using hiPSC-derived motor neurons generated via a dual SMAD inhibition–based protocol (Fujimori et al., 2018, Morimoto et al., 2023). The trial demonstrated a slowing in disease progression, as measured by the revised ALS Functional Rating Scale and a prolonged period without disease progression in treated patients (Morimoto et al., 2023). In the same study, patient-derived hiPSCs were differentiated into motor neurons using a similar protocol to investigate the mechanism of action of the drug. Another notable application of dual SMAD inhibition–based differentiation involved the use of hiPSC-derived cortical neurons to investigate the mechanism of action of branaplam, a drug candidate for Huntington’s disease (Krach et al., 2022). Branaplam, a modulator of alternative splicing, has advanced to a phase 2 clinical trial, which was later terminated because of concerns about peripheral neuropathy in treated patients (Estevez-Fraga et al., 2024). Despite the discontinuation of the trial, this study demonstrated the utility of dual SMAD inhibition–derived cortical neurons in modeling Huntington’s disease phenotypes and evaluating therapeutic mechanisms in vitro (Krach et al., 2022).

In addition to neurodegenerative diseases, the dual SMAD inhibition protocol and its derivatives have been applied to model other diseases, as well as fundamental aspects of human development, as demonstrated by studies on Hirschsprung’s disease, Timothy syndrome, and Batten disease (Birey et al., 2022, Fan et al., 2023, Ofrim et al., 2024). One notable example involves the generation of hypothalamic neurons from hiPSCs derived from individuals with either normal or extremely high body mass index using a dual SMAD inhibition–based protocol (Rajamani et al., 2018). Hypothalamic neurons are key regulators of hunger and satiety within the CNS, responding to peripheral signals, such as ghrelin and leptin. This study revealed the upregulation of obesity-associated signature genes and altered hormonal responsiveness in hypothalamic neurons derived from obese individuals, demonstrating the relevance of this model for studying obesity-related hypothalamic dysfunction. In the context of infectious diseases, Yang et al. (2024) used a dual SMAD-based protocol to demonstrate the susceptibility of hPSC-derived mDA neurons to SARS-CoV-2 infection (Yang et al., 2024). This study identified 3 drug candidates capable of mitigating virus-induced cellular senescence in these neurons. Additionally, our recently published study employed dual SMAD inhibition to differentiate hPSCs into serotonin, dopamine, and cortical neurons to investigate the role of autophagy in early neuronal development (Vidyawan et al., 2025). Their findings implicated WNT signaling as a mediator that temporally regulates neuronal differentiation.

Collectively, these studies underscore the versatility of dual SMAD-based protocols for modeling diverse human biological processes and pathologies, including neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic dysregulation, viral infections, and neurodevelopment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Applications of dual SMAD inhibition in disease modeling using human pluripotent stem cells. The protocol has enabled the generation of disease-relevant neuronal subtypes, including cortical, dopamine, motoneurons, and hypothalamic neurons, for modeling neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and ALS, as well as metabolic disease and human neurodevelopment. The resulting models have facilitated drug screening and disease and drug mechanism studies and contributed to the development of patient-specific hiPSC-derived neurons, highlighting the protocol’s broad utility in modeling both neurodegenerative and developmental conditions.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Given the importance of dual SMAD inhibition in establishing brain region–specific differentiation protocols, its significant contribution to transplantation studies, and its broad applicability in modeling human development and diverse diseases, it is necessary to critically evaluate its relative strengths and limitations (Fig. 5). This section provides a balanced assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of the dual SMAD inhibition strategy and offers insights into areas where refinement can lead to better outcomes in future studies.

Fig. 5.

Overview of the strengths and limitations of the dual SMAD inhibition strategy. The protocol offers high purity, efficiency, and reproducibility, along with rapid differentiation, ease of use, precise control of cell fate, and adaptability to both 2D and 3D platforms. However, it is constrained by limited gliogenic capacity, lack of expandable neural progenitor stages, reduced effectiveness in naive-state cells, and additional requirements for functional maturation and aging-related modeling. 2D, 2-dimensional; 3D, 3-dimensional.

Differentiating hPSCs using a dual SMAD inhibition strategy allows researchers to identify a critical developmental time window during which neuronal subtype specifications can be precisely controlled via additional patterning cues. This temporal control enabled highly efficient and directed neural differentiation. Notably, many protocols originally established in 2-dimensional (2D) cultures using dual SMAD inhibition have been successfully adapted to 3-dimensional (3D) culture systems, giving rise to neurospheres and brain region–specific organoids that retain similar regional identities (Jo et al., 2016, Rosebrock et al., 2022, Valiulahi et al., 2021). Dual SMAD inhibition serves as a foundational step in numerous organoid protocols, including those for generating cortical, midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal organoids (Jo et al., 2016, Kim et al., 2025, Rosebrock et al., 2022, Valiulahi et al., 2021). The establishment of these regionally patterned organoids has further enabled the development of assembloids and composite organoid systems that model interactions between distinct brain regions that model specific functions (Andersen et al., 2020, Paşca, 2019, Sloan et al., 2018). A recent study published in Nature brought this advancement further by generating assembloids composed of four organoid types: cortical, diencephalic, dorsal spinal cord, and somatosensory, which were derived from the same hiPSC line (Kim et al., 2025). Notably, all but the somatosensory organoids were differentiated using the protocols based on dual SMAD inhibition.

One principle of embryonic development is that homogeneous neighboring cells can adopt distinct cell fates. For example, the inner cell mass, the origin of hESCs, gives rise to 3 germ layers: the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm (Itskovitz-Eldor et al., 2000, Thomson et al., 1998), and the neuroectoderm diversifies into a wide array of neuronal and glial cell populations representing all brain regions (Ozair et al., 2013). Although this heterogeneity is essential for in vivo development, it can be a significant drawback in certain in vitro applications, such as transplantation or disease modeling, where mixed cell populations may complicate the interpretation of results. The dual SMAD inhibition protocol employs small molecules, such as dorsomorphin and SB431542, to selectively target and inhibit TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways by directly interacting with cell surface receptors (Chambers et al., 2009, Ozair et al., 2013). This targeted receptor-level modulation prevents extracellular signals from initiating divergent intracellular cascades, thereby ensuring that cell fate decisions are consistently driven by specific, predefined intracellular signaling events. By minimizing external variability, this approach significantly enhances the uniformity and predictability of neuronal differentiation outcomes of hPSCs, which has contributed to its successful application in transplantation studies.

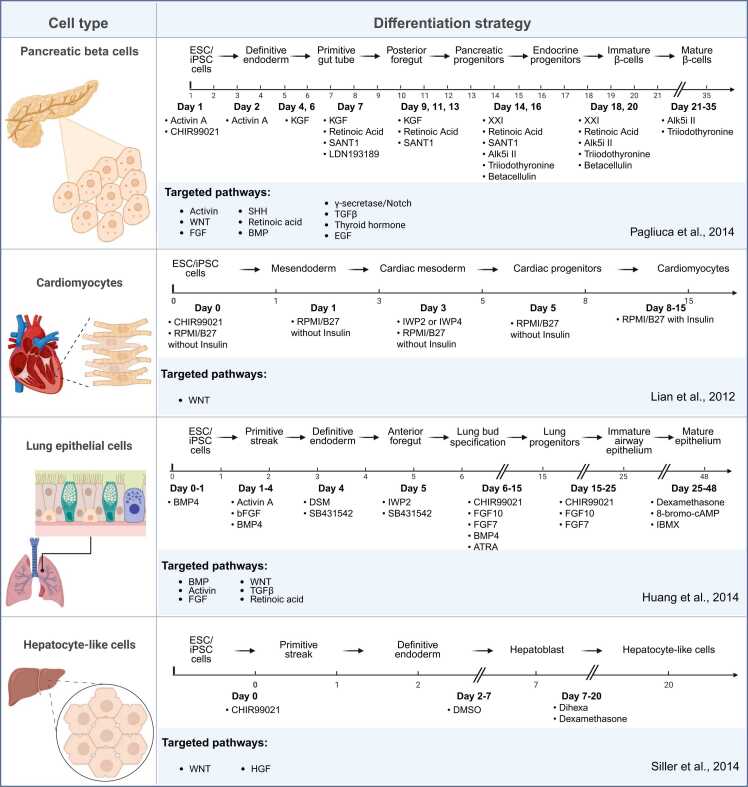

This strategy of controlling cell fate by manipulating intracellular signaling with small molecules has laid the groundwork for protocols utilizing other defined small molecules, such as purmorphamine and CHIR99021. Purmorphamine activates the hedgehog receptor smoothened by directly binding to the receptor, which in turn activates the GLI family of transcription factors to induce ventral neural identity, including the floor plate and mDA neurons (Kriks et al., 2011, Prajapati et al., 2024). CHIR99021, a selective inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3β, stabilizes β-catenin and activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby promoting caudalization and posterior neural identities, such as spinal cord neurons (Sun et al., 2024, Tan et al., 2015). Through the direct and defined modulation of these key developmental pathways at the intracellular level, these small molecules enable the controlled, efficient, and reproducible specification of distinct neural subtypes from hPSCs, extending the conceptual framework originally established by dual SMAD inhibition. Furthermore, the success of this small–molecule-based strategy has inspired its application beyond neural differentiation. Similar approaches have been employed to generate a variety of cell types, including lung epithelial and pancreatic beta cells, through the precise modulation of lineage-specific signaling pathways (Huang et al., 2014, Pagliuca et al., 2014).

A major advantage of the dual SMAD inhibition protocol is its ability to induce neuronal differentiation with high purity (>80%) within a relatively short timeframe and with reduced technical complexity compared with other existing methods (Chambers et al., 2009). For instance, the stromal cell coculture method using MS5 feeder cells requires continuous maintenance of stromal layers and precise control of coculture conditions, with neural induction typically occurring over approximately 4 weeks (Perrier et al., 2004). In contrast, dual SMAD inhibition enabled neural induction within 11 d and the generation of mature neurons within 2 to 3 weeks (Chambers et al., 2009). While EB formation can also yield neurons within approximately 3 weeks, this method often produces highly heterogeneous cell populations, necessitating additional enrichment steps to isolate neuronal cells (Zhang et al., 2001).

Despite its numerous advantages, the dual SMAD inhibition strategy can be further improved. The high purity of the generated neurons can be less ideal in settings where heterogeneous cell populations are desired. Originally designed primarily to induce neuronal differentiation, the dual SMAD inhibition protocol has not yet been optimized for glial cell formation (Otero et al., 2023, Patel et al., 2019). Epigenetic analyses have demonstrated that NPCs exhibit neurogenic potential during early embryonic brain development, but progressively transition to gliogenic competence, giving rise first to astrocytes and subsequently to oligodendrocytes at later developmental stages (Adefuin et al., 2014). The rapid induction of neuronal identity inherent in dual SMAD inhibition protocols restricts the necessary proliferative phase during which NPCs acquire gliogenic potential.

The establishment of NPC lines capable of proliferation, cryopreservation, and immediate availability for transplantation would facilitate the translation from preclinical studies to clinical applications (Kobayashi et al., 2023). This highlights another significant limitation of dual SMAD inhibition: the near absence of a prolonged proliferative NPC stage owing to rapid neuronal programming. To address these limitations, a recent study integrated 3D-culture systems to generate expandable NPC populations with an enhanced gliogenic potential (Nam et al., 2025). This study established a dual SMAD-based protocol to generate neural organoids from hPSCs, which were subsequently dissociated to isolate NPC populations. These NPCs were then expanded under monolayer culture conditions in the presence of the mitogens EGF and FGF2, thereby maintaining their proliferative capacity and promoting the acquisition of astrogenic potential. After multiple passages, the astrocyte progenitors effectively differentiated into mature astrocytes upon mitogen withdrawal.

Although the dual SMAD inhibition protocol has consistently demonstrated robust efficacy across hPSC lines, there have been no reports of the successful production of comparable results in less-primed pluripotent cells, such as mESCs. Supporting this, a study has shown that SMAD2/3 inhibition reduces Nanog expression in mouse epiblast stem cells, which exhibit a primed pluripotency state, but not in naive-state mESCs (Greber et al., 2010). This finding suggests that dual SMAD inhibition may not achieve equivalent neural induction efficiency in naive pluripotent cells. Therefore, applying dual SMAD-based protocols to naive pluripotent cells requires caution and potentially additional reprogramming or priming steps to achieve lineage-specific differentiation.

Another limitation of dual SMAD inhibition relates to its widespread application in the modeling of neurodegenerative diseases, many of which exhibit late-onset characteristics in aged neurons (Puspita et al., 2017, Sharma and Jaganathan, 2021, Zhang et al., 2025). Dual SMAD inhibition predominantly focuses on early-stage fate determination rather than on neuronal maturation. However, this limitation is not exclusive to the dual SMAD inhibition approach, and significant efforts have recently been dedicated to accelerating neuronal aging and maturation in vitro (Hergenreder et al., 2024, Miller et al., 2013, Riessland et al., 2019). One innovative approach utilizes insights gained from Hutchinson-Gilford progeroid syndrome, also known as progeria syndrome. In patients with progeria syndrome, a mutant variant of lamin A, progerin, induces a premature aging phenotype. Leveraging this phenomenon, 1 study transiently introduced truncated progerin, using synthetic RNA, during the differentiation of hiPSCs into mDAs via dual SMAD inhibition (Miller et al., 2013). This approach successfully induced aging-associated phenotypes characterized by increased DNA damage and elevated mitochondrial oxidative stress. Additionally, a recent notable effort was directed toward accelerating neuronal maturation using cortical neurons generated with dual SMAD inhibition (Hergenreder et al., 2024). Through compound screening, they identified a combination comprising two lysine-specific demethylase 1 inhibitors, an L-type calcium channel agonist, and a telomerase-like 1 inhibitor disruptor. This cocktail markedly accelerated neuronal maturation and functional properties across cortical neurons derived from multiple hPSC lines, demonstrating a promising strategy for addressing the maturation constraints associated with dual SMAD inhibition protocols.

In summary, the dual SMAD inhibition protocol marks a pivotal advancement in stem cell–based neural differentiation, enabling the efficient and reproducible generation of diverse neuronal subtypes. Its integration into both 2D- and 3D-culture systems has facilitated the development of region-specific organoids and assembloids, advancing brain development and disease modeling. Although the protocol has some limitations, particularly in capturing the full complexity of neural differentiation and maturation, ongoing refinements and complementary strategies continue to enhance its usefulness in both basic research and regenerative medicine.

CLOSING: FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF DIFFERENTIATION STRATEGY

Over the past 16 years, dual SMAD inhibition has played a transformative role in stem cell science, particularly in the efficient and reproducible generation of homogeneous neuronal populations from hPSCs. However, as the field progresses, it will be critical to consider next-generation strategies that build upon these strengths and address the limitations of this fundamental method.

A promising direction lies in the complementary integration of dual SMAD inhibition in brain organoid systems. Although dual SMAD inhibition produces high yields of homogeneous neuronal populations, organoid systems offer a more complex 3D architecture that better recapitulates in vivo developmental processes (Zhang et al., 2022). Organoids allow for the generation of heterogeneous cell populations, including neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, thereby offering a model system that is highly representative of brain tissue development (Fig. 6). These 2 methods are not mutually exclusive; rather, the versatility of the dual SMAD inhibition strategy makes it suitable for the initial establishment of region-specific neuronal differentiation protocols (Dannert et al., 2023, Du et al., 2015, Kriks et al., 2011, Valiulahi et al., 2021). With minimal adjustments, these protocols can be adapted to 3D systems to generate multiregion organoids, ultimately enabling assembloid formation that recapitulates complex neural circuits (Andersen et al., 2020, Jo et al., 2016, Kim et al., 2025, Rosebrock et al., 2022, Valiulahi et al., 2021).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of 2D- and 3D-culture systems based on dual SMAD inhibition strategy. While 2D-culture systems offer homogeneous populations, high throughput, and optimal compatibility with AI-based imaging platforms, 3D organoids better recapitulate developmental complexity, multicellular interactions, and generation of heterogeneous populations. Dual SMAD inhibition serves as a foundational protocol in both systems, enabling applications in gene editing, disease modeling, and hybrid workflows that begin in monolayer and transition into 3D systems. Dual SMAD inhibition also supports scalable industrial applications in both monolayer and organoid systems. AI, artificial intelligence.

Concurrently, technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning, are reshaping how data are processed and interpreted in stem cell science (Choudhury et al., 2025, Moen et al., 2019). Deep learning algorithms can automate and enhance image-based analyses by recognizing complex cellular patterns, classifying cell states, outlining individual cells, and tracking dynamic behaviors in live-cell imaging (Kong et al., 2022, Moen et al., 2019). These analytical capabilities are particularly compatible with dual SMAD inhibition protocols that utilize monolayer culture systems to provide optimal conditions for AI-based high-speed imaging. In parallel, the application of gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, has facilitated hPSC reporter line generation, enabling live-cell analysis and precise monitoring of lineage commitment and cellular identity (Puspita et al., 2024). Notably, dual SMAD inhibition has consistently shown robust and reproducible performance across a wide range of hPSC lines to the neuronal lineage, including genetically modified reporter lines, making it a versatile platform well-suited for integration with AI-driven analytical pipelines.

Although this method was established more than a decade ago, the fundamental characteristics of dual SMAD inhibition remain highly relevant, including industrial applications. Beyond neuroscience, the principle underlying dual SMAD inhibition, the precise control of signaling pathways to direct cell fate, has also influenced differentiation strategies for other cell types (Fig. 7), such as cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, pancreatic beta, and lung epithelial cells, marking it as a paradigm-shifting contribution to the field (Huang et al., 2014, Lian et al., 2013, Pagliuca et al., 2014, Siller et al., 2015). As stem cell–based technologies move closer to clinical and commercial implementation, differentiation strategies must be evaluated not only for biological relevance but also for their reproducibility, scalability, and compatibility with automated systems. Future studies should focus on refining and integrating these protocols with the emerging tools to meet the growing demands of biomedical research and regenerative medicine.

Fig. 7.

Differentiation strategies for generating various cell types from human pluripotent stem cells using small–molecule-based protocols. Schematic overview of representative protocols for deriving lung epithelial cells, hepatocyte-like cells, pancreatic β-cells, and cardiomyocytes. Each timeline illustrates the sequential application of signaling modulators and growth factors at defined developmental stages, targeting key pathways such as WNT, BMP, Activin/Nodal, FGF, TGF-β, RA, SHH, thyroid hormone, and Notch.

Funding and Support

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) of the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (grant numbers NRF-2021R1A2C1005940 and NRF-2019R1A5A8083404). All the figures were created using Bio-Render.com.

Author Contributions

Magdalena Deline: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Lesly Puspita: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Jae-won Shim: Supervision, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Adefuin A.M.D., Kimura A., Noguchi H., Nakashima K., Namihira M. Epigenetic mechanisms regulating differentiation of neural stem/precursor cells. Epigenomics. 2014;6(6):637–649. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J., Revah O., Miura Y., Thom N., Amin N.D., Kelley K.W., Singh M., Chen X., Thete M.V., Walczak E.M., et al. Generation of functional human 3D cortico-motor assembloids. Cell. 2020;183(7):1913–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.017. e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker R.A., Barrett J., Mason S.L., Björklund A. Fetal dopaminergic transplantation trials and the future of neural grafting in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershteyn M., Bröer S., Parekh M., Maury Y., Havlicek S., Kriks S., Fuentealba L., Lee S., Zhou R., Subramanyam G., et al. Human pallial MGE-type GABAergic interneuron cell therapy for chronic focal epilepsy. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(10):1331–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.08.013. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birey F., Li M.Y., Gordon A., Thete M.V., Valencia A.M., Revah O., Paşca A.M., Geschwind D.H., Paşca S.P. Dissecting the molecular basis of human interneuron migration in forebrain assembloids from Timothy syndrome. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29(2):248–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhnke L., Zhou-Yang L., Pelucchi S., Kogler F., Frantal D., Schön F., Lagerström S., Borgogno O., Baltazar J., Herdy J.R., et al. Chemical replacement of noggin with dorsomorphin homolog 1 for cost-effective direct neuronal conversion. Cell. Reprogram. 2022;24(5):304–313. doi: 10.1089/cell.2021.0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S.M., Fasano C.A., Papapetrou E.P., Tomishima M., Sadelain M., Studer L. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27(3):275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S.M., Mica Y., Lee G., Studer L., Tomishima M.J. In: Human Embryonic Stem Cell Protocols. Turksen K., editor. United States: Humana Press; New York: 2013. Dual-SMAD inhibition/WNT activation-based methods to induce neural crest and derivatives from human pluripotent stem cells; pp. 329–343. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.C., Mazzaferro S., Tian T., Mali I., Merkle F.T. Differentiation, transcriptomic profiling, and calcium imaging of human hypothalamic neurons. Curr. Protoc. 2023;3(6) doi: 10.1002/cpz1.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury M., Deans A.J., Candland D.R., Deans T.L. Advancing cell therapies with artificial intelligence and synthetic biology. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2025;34 doi: 10.1016/j.cobme.2025.100580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuny G.D., Yu P.B., Laha J.K., Xing X., Liu J.F., Lai C.S., Deng D.Y., Sachidanandan C., Bloch K.D., Peterson R.T. Structure–activity relationship study of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18(15):4388–4392. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannert A., Klimmt J., Cardoso Gonçalves C., Crusius D., Paquet D. Reproducible and scalable differentiation of highly pure cortical neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells. STAR Protoc. 2023;4(2) doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z.W., Chen H., Liu H., Lu J., Qian K., Huang C.L., Zhong X., Fan F., Zhang S.C. Generation and expansion of highly pure motor neuron progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6(1):6626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez-Fraga C., Tabrizi S.J., Wild E.J. Huntington’s disease clinical trials corner: March 2024. J. Huntingtons Dis. 2024;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.3233/JHD-240017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Hackland J., Baggiolini A., Hung L.Y., Zhao H., Zumbo P., Oberst P., Minotti A.P., Hergenreder E., Najjar S., et al. hPSC-derived sacral neural crest enables rescue in a severe model of Hirschsprung’s disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(3):264–282. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forostyak S., Forostyak O., Kwok J.C.F., Romanyuk N., Rehorova M., Kriska J., Dayanithi G., Raha-Chowdhury R., Jendelova P., Anderova M., et al. Transplantation of neural precursors derived from induced pluripotent cells preserve perineuronal nets and stimulate neural plasticity in ALS rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(24):9593. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori K., Ishikawa M., Otomo A., Atsuta N., Nakamura R., Akiyama T., Hadano S., Aoki M., Saya H., Sobue G., et al. Modeling sporadic ALS in iPSC-derived motor neurons identifies a potential therapeutic agent. Nat. Med. 2018;24(10):1579–1589. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Guo Y., Biswas S., Li J., Zhang H., Chen Z., Deng W. Promoting oligodendrocyte differentiation from human induced pluripotent stem cells by activating endocannabinoid signaling for treating spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022;18(8):3033–3049. doi: 10.1007/s12015-022-10405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber B., Wu G., Bernemann C., Joo J.Y., Han D.W., Ko K., Tapia N., Sabour D., Sterneckert J., Tesar P., et al. Conserved and divergent roles of fgf signaling in mouse epiblast stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(3):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene P.E., Fahn S., Eidelberg D., Bjugstad K.B., Breeze R.E., Freed C.R. Persistent dyskinesias in patients with fetal tissue transplantation for Parkinson disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):38. doi: 10.1038/s41531-021-00183-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttikonda S.R., Sikkema L., Tchieu J., Saurat N., Walsh R.M., Harschnitz O., Ciceri G., Sneeboer M., Mazutis L., Setty M., et al. Fully defined human pluripotent stem cell-derived microglia and tri-culture system model C3 production in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2021;24(3):343–354. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00796-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenreder E., Minotti A.P., Zorina Y., Oberst P., Zhao Z., Munguba H., Calder E.L., Baggiolini A., Walsh R.M., Liston C., et al. Combined small-molecule treatment accelerates maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024;42(10):1515–1525. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-02031-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S.X.L., Islam M.N., O’Neill J., Hu Z., Yang Y.G., Chen Y.W., Mumau M., Green M.D., Vunjak-Novakovic G., Bhattacharya J., et al. Efficient generation of lung and airway epithelial cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32(1):84–91. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itskovitz-Eldor J., Schuldiner M., Karsenti D., Eden A., Yanuka O., Amit M., Soreq H., Benvenisty N. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into embryoid bodies compromising the three embryonic germ layers. Mol. Med. 2000;6(2):88–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J., Cha Y., Hong Y.J., Lee I.H., Jang H., Ko S., Naumenko S., Kim M., Ryu H.L., Shrestha Z., et al. Pre-clinical safety and efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived products for autologous cell therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2025;32(3):343–360.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2025.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S., Meng A. TGFβ family signaling and development. Development. 2021;148(5) doi: 10.1242/dev.188490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., Xiao Y., Sun A.X., Cukuroglu E., Tran H.D., Göke J., Tan Z.Y., Saw T.Y., Tan C.P., Lokman H., et al. Midbrain-like organoids from human pluripotent stem cells contain functional dopaminergic and neuromelanin-producing neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19(2):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I., Novikova L.N., Wiberg M., Carlsson L., Novikov L.N. Human embryonic stem cell–derived neural crest cells promote sprouting and motor recovery following spinal cord injury in adult rats. Cell Transplant. 2021;30 doi: 10.1177/0963689720988245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Mizuseki K., Nishikawa S., Kaneko S., Kuwana Y., Nakanishi S., Nishikawa S.I., Sasai Y. Induction of midbrain dopaminergic neurons from ES cells by stromal cell–derived inducing activity. Neuron. 2000;28(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecker C., Bates T., Bell E. Molecular specification of germ layers in vertebrate embryos. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73(5):923–947. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Imaizumi K., Jurjuț O., Kelley K.W., Wang D., Thete M.V., Hudacova Z., Amin N.D., Levy R.J., Scherrer G., et al. Human assembloid model of the ascending neural sensory pathway. Nature. 2025;642:143–153. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08808-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.S., Ra E.A., Kweon S.H., Seo B.A., Ko H.S., Oh Y., Lee G. Advanced human iPSC-based preclinical model for Parkinson’s disease with optogenetic alpha-synuclein aggregation. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(7):973–986. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.05.015. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.W., Piao J., Koo S.Y., Kriks S., Chung S.Y., Betel D., Socci N.D., Choi S.J., Zabierowski S., Dubose B.N., et al. Biphasic activation of WNT signaling facilitates the derivation of midbrain dopamine neurons from hESCs for translational use. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(2):343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.01.005. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkeby A., Grealish S., Wolf D.A., Nelander J., Wood J., Lundblad M., Lindvall O., Parmar M. Generation of regionally specified neural progenitors and functional neurons from human embryonic stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Rep. 2012;1(6):703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkeby A., Nelander J., Hoban D.B., Rogelius N., Bjartmarz H., Storm P., Fiorenzano A., Adler A.F., Vale S., Mudannayake J., et al. Preclinical quality, safety, and efficacy of a human embryonic stem cell-derived product for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, STEM-PD. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(10):1299–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.08.014. e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Shigyo M., Platoshyn O., Marsala S., Kato T., Takamura N., Yoshida K., Kishino A., Bravo-Hernandez M., Juhas S., et al. Expandable sendai-virus-reprogrammed human iPSC-neuronal precursors: in vivo post-grafting safety characterization in rats and adult pig. Cell Transplant. 2023;32 doi: 10.1177/09636897221107009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W., Fu Y.C., Holloway E.M., Garipler G., Yang X., Mazzoni E.O., Morris S.A. Capybara: a computational tool to measure cell identity and fate transitions. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29(4):635–649.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2022.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower J.H., Freeman T.B., Snow B.J., Vingerhoets F.J.G., Mufson E.J., Sanberg P.R., Hauser R.A., Smith D.A., Nauert G.M., Perl D.P., et al. Neuropathological evidence of graft survival and striatal reinnervation after the transplantation of fetal mesencephalic tissue in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332(17):1118–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krach F., Stemick J., Boerstler T., Weiss A., Lingos I., Reischl S., Meixner H., Ploetz S., Farrell M., Hehr U., et al. An alternative splicing modulator decreases mutant HTT and improves the molecular fingerprint in Huntington’s disease patient neurons. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):6797. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34419-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriks S., Shim J., Piao J., Ganat Y.M., Wakeman D.R., Xie Z., Carrillo-Reid L., Auyeung G., Antonacci C., Buch A., et al. Dopamine neurons derived from human ES cells efficiently engraft in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2011;480(7378):547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh T., Wilson S.W., Dawid I.B. Distinct roles for Fgf, Wnt and retinoic acid in posteriorizing the neural ectoderm. Development. 2002;129(18):4335–4346. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laperle A.H., Moser V.A., Avalos P., Lu B., Wu A., Fulton A., Ramirez S., Garcia V.J., Bell S., Ho R., et al. Human iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells secreting GDNF provide protection in rodent models of ALS and retinal degeneration. Stem Cell Rep. 2023;18(8):1629–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Lumelsky N., Studer L., Auerbach J.M., McKay R.D. Efficient generation of midbrain and hindbrain neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18(6):675–679. doi: 10.1038/76536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Luo W., Xiao C., Zhao J., Xiang C., Liu W., Gu R. Recent advances in endogenous neural stem/progenitor cell manipulation for spinal cord injury repair. Theranostics. 2023;13(12):3966–3987. doi: 10.7150/thno.84133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.J., Du Z.W., Zarnowska E.D., Pankratz M., Hansen L.O., Pearce R.A., Zhang S.C. Specification of motoneurons from human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23(2):215–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X., Zhang J., Azarin S.M., Zhu K., Hazeltine L.B., Bao X., Hsiao C., Kamp T.J., Palecek S.P. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8(1):162–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O., Brundin P., Widner H., Rehncrona S., Gustavii B., Frackowiak R., Leenders K.L., Sawle G., Rothwell J.C., Marsden C.D., et al. Grafts of fetal dopamine neurons survive and improve motor function in Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1990;247(4942):574–577. doi: 10.1126/science.2105529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A., Niswander L.A. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling and vertebrate nervous system development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6(12):945–954. doi: 10.1038/nrn1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Zhong X., Liu H., Hao L., Huang C.T.L., Sherafat M.A., Jones J., Ayala M., Li L., Zhang S.C. Generation of serotonin neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34(1):89–94. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macečková Brymová A., Rodriguez-Jimenez F.J., Konrad A., Nemesh Y., Thottappali M.A., Artero-Castro A., Nyshchuk R., Kolesnikova A., Müller B., Studenovska H., et al. Delivery of human iPSC-derived RPE cells in healthy minipig retina results in interaction between photoreceptors and transplanted cells. Adv. Sci. 2025;12(20) doi: 10.1002/advs.202412301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai M., Watanabe A., Kurimoto Y., Hirami Y., Morinaga C., Daimon T., Fujihara M., Akimaru H., Sakai N., Shibata Y., et al. autologous induced stem-cell–derived retinal cells for macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376(11):1038–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.C., Morriss-Kay G.M. Functional anatomy of the human brain. J. Anat. 2004;205(6) 415-415. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini L., Gelati M., Profico D.C., Sorarù G., Ferrari D., Copetti M., Muzi G., Ricciolini C., Carletti S., Giorgi C., et al. Results from phase I clinical trial with intraspinal injection of neural stem cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a long-term outcome. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019;8(9):887–897. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini L., Gelati M., Profico D., Sgaravizzi G., Projetti Pensi M., Muzi G., Ricciolini C., Rota Nodari L., Carletti S., Giorgi C., et al. Human neural stem cell transplantation in ALS: initial results from a phase I trial. J. Transl. Med. 2015;13(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0371-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzulli J.R., Xu Y.H., Sun Y., Knight A.L., McLean P.J., Caldwell G.A., Sidransky E., Grabowski G.A., Krainc D. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell. 2011;146(1):37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle F.T., Maroof A., Wataya T., Sasai Y., Studer L., Eggan K., Schier A.F. Generation of neuropeptidergic hypothalamic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2015;142(4):633–643. doi: 10.1242/dev.117978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.D., Ganat Y.M., Kishinevsky S., Bowman R.L., Liu B., Tu E.Y., Mandal P.K., Vera E., Shim J., Kriks S., et al. Human iPSC-based modeling of late-onset disease via progerin-induced aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(6):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen E., Bannon D., Kudo T., Graf W., Covert M., Van Valen D. Deep learning for cellular image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2019;16(12):1233–1246. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto S., Takahashi S., Ito D., Daté Y., Okada K., Kato C., Nakamura S., Ozawa F., Chyi C.M., Nishiyama A., et al. Phase 1/2a clinical trial in ALS with ropinirole, a drug candidate identified by iPSC drug discovery. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(6):766–780. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.04.017. e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y.R., Kang M., Kim M., Seok M.J., Yang Y., Han Y.E., Oh S.J., Kim D.G., Son H., Chang M.Y., et al. Preparation of human astrocytes with potent therapeutic functions from human pluripotent stem cells using ventral midbrain patterning. J. Adv. Res. 2025;69:181–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neirinckx V., Cantinieaux D., Coste C., Rogister B., Franzen R., Wislet-Gendebien S. Concise review: spinal cord injuries: how could adult mesenchymal and neural crest stem cells take up the challenge? Stem Cells. 2014;32(4):829–843. doi: 10.1002/stem.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofrim M., Little D., Nazari M., Minnis C.J., Devine M.J., Mole S.E., Gissen P., Lorvellec M. Characterization of two human induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from Batten disease patient fibroblasts harbouring CLN5 mutations. Stem Cell Res. 2024;74 doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2023.103291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero M.G., Bell S., Laperle A.H., Lawless G., Myers Z., Castro M.A., Villalba J.M., Svendsen C.N. Organ-chips enhance the maturation of human iPSC-derived dopamine neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(18):14227. doi: 10.3390/ijms241814227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozair M.Z., Kintner C., Brivanlou A.H. Neural induction and early patterning in vertebrates. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2013;2(4):479–498. doi: 10.1002/wdev.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliuca F.W., Millman J.R., Gürtler M., Segel M., Van Dervort A., Ryu J.H., Peterson Q.P., Greiner D., Melton D.A. Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159(2):428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Park C.W., Eom J.H., Jo M.Y., Hur H.J., Choi S.K., Lee J.S., Nam S.T., Jo K.S., Oh Y.W., et al. Preclinical and dose-ranging assessment of hESC-derived dopaminergic progenitors for a clinical trial on Parkinson’s disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31(1):25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2023.11.009. e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paşca S.P. Assembling human brain organoids. Science. 2019;363(6423):126–127. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A.M., Wierda K., Thorrez L., van Putten M., De Smedt J., Ribeiro L., Tricot T., Gajjar M., Duelen R., Van Damme P., et al. Dystrophin deficiency leads to dysfunctional glutamate clearance in iPSC derived astrocytes. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):200. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0535-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier A.L., Tabar V., Barberi T., Rubio M.E., Bruses J., Topf N., Harrison N.L., Studer L. Derivation of midbrain dopamine neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101(34):12543–12548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao J., Zabierowski S., Dubose B.N., Hill E.J., Navare M., Claros N., Rosen S., Ramnarine K., Horn C., Fredrickson C., et al. Preclinical efficacy and safety of a human embryonic stem cell-derived midbrain dopamine progenitor product, MSK-DA01. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(2):217–229.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placzek M., Briscoe J. The floor plate: multiple cells, multiple signals. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6(3):230–240. doi: 10.1038/nrn1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati A., Mehan S., Khan Z., Chhabra S., Das Gupta G. Purmorphamine, a smo-shh/gli activator, promotes sonic hedgehog-mediated neurogenesis and restores behavioural and neurochemical deficits in experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 2024;49(6):1556–1576. doi: 10.1007/s11064-023-04082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puspita L., Chung S.Y., Shim J. Oxidative stress and cellular pathologies in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Brain. 2017;10(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13041-017-0340-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puspita L., Juwono V.B., Shim J. Advances in human pluripotent stem cell reporter systems. IScience. 2024;27(9) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamani U., Gross A.R., Hjelm B.E., Sequeira A., Vawter M.P., Tang J., Gangalapudi V., Wang Y., Andres A.M., Gottlieb R.A., et al. Super-obese patient-derived iPSC hypothalamic neurons exhibit obesogenic signatures and hormone responses. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(5):698–712. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.009. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro B.F., da Cruz B.C., de Sousa B.M., Correia P.D., David N., Rocha C., Almeida R.D., Ribeiro da Cunha M., Marques Baptista A.A., Vieira S.I. Cell therapies for spinal cord injury: a review of the clinical trials and cell-type therapeutic potential. Brain. 2023;146(7):2672–2693. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann C.D., Banin E., Barak A., Boyer D.S., Ehrlich R., Jaouni T., McDonald R., Telander D., Keane M., Ackert J., et al. Phase I/IIa clinical trial of human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE, OpRegen) transplantation in advanced dry form age-related macular degeneration (AMD): interim results. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020;61(7):865. [Google Scholar]

- Riessland M., Kolisnyk B., Kim T.W., Cheng J., Ni J., Pearson J.A., Park E.J., Dam K., Acehan D., Ramos-Espiritu L.S., et al. Loss of SATB1 induces p21-dependent cellular senescence in post-mitotic dopaminergic neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25(4):514–530. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.013. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosebrock D., Arora S., Mutukula N., Volkman R., Gralinska E., Balaskas A., Aragonés Hernández A., Buschow R., Brändl B., et al. Enhanced cortical neural stem cell identity through short SMAD and WNT inhibition in human cerebral organoids facilitates emergence of outer radial glial cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022;24(6):981–995. doi: 10.1038/s41556-022-00929-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R.G., Daley G.Q. Induced pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20(7):377–388. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0100-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto N., Doi D., Nakanishi E., Sawamura M., Kikuchi T., Yamakado H., Taruno Y., Shima A., Fushimi Y., Okada T., et al. Phase I/II trial of iPS-cell-derived dopaminergic cells for Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2025;641(8064):971–977. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08700-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S.D., Regillo C.D., Lam B.L., Eliott D., Rosenfeld P.J., Gregori N.Z., Hubschman J.P., Davis J.L., Heilwell G., Spirn M., et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy: follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):509–516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Jaganathan B.G. Stem cell therapy for retinal degeneration: the evidence to date. Biologics. 2021;15:299–306. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S290331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Bose D., Montford J., Ortolan D., Bharti K. Triphasic developmentally guided protocol to generate retinal pigment epithelium from induced pluripotent stem cells. STAR Protoc. 2022;3(3) doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Khristov V., Rising A., Jha B.S., Dejene R., Hotaling N., Li Y., Stoddard J., Stankewicz C., Wan Q., Zhang C., et al. Clinical-grade stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelium patch rescues retinal degeneration in rodents and pigs. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11(475) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller R., Greenhough S., Naumovska E., Sullivan G.J. Small-molecule-driven hepatocyte differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(5):939–952. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson O.E., Domogatskaya A., Volchkov P., Rodin S. The safety of human pluripotent stem cells in clinical treatment. Ann. Med. 2015;47(5):370–380. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1051579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan S.A., Andersen J., Pașca A.M., Birey F., Pașca S.P. Generation and assembly of human brain region–specific three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13(9):2062–2085. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P., Yuan Y., Lv Z., Yu X., Ma H., Liang S., Zhang J., Zhu J., Lu J., Wang C., et al. Generation of self-renewing neuromesodermal progenitors with neuronal and skeletal muscle bipotential from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. Methods. 2024;4(11) doi: 10.1016/j.crmeth.2024.100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]