Abstract

There is a growing interest in using resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) to investigate language processing and recovery in post-stroke aphasia due to its limited dependence on an individual's ability to follow directions and perform tasks, or the severity of their aphasia. However, the test-retest reliability of RSFC in people with aphasia has not been established, raising questions about the strength and validity of inferences based on this technique. In this study, we examined the reliability of RSFC at the level of individual edges (i.e., connections) in 14 adults with chronic aphasia due to left-hemisphere stroke. Intraclass correlations (ICCs) between two resting-state scans obtained over a few days were computed for every edge in a whole-brain network and several cognitive and language subnetworks. Based on median ICCs, reliability was fair at longer scan durations (10–12 min) and better in most subnetworks than the whole brain. Reliability was also positively associated with connectivity strength and had a weak negative relationship with inter-node distance (i.e., the distance between the regions that form an edge). Edges in the right hemisphere were more reliable than those in the left hemisphere and between hemispheres, though all three sets of edges were fairly reliable. The results indicate that edge-level RSFC is acceptably reliable for continued use in aphasia research but highlight the need for strategies to ensure that inferences are based on valid results, such as using sufficiently long scans and focusing analyses on established subnetworks, especially in longitudinal contexts.

Keywords: Aphasia, Resting state, fMRI, Functional connectivity, Test-retest reliability

1. Introduction

Aphasia, a language disorder often caused by stroke, affects more than two million adults in the United States (Simmons-Mackie, 2018). Aphasia interferes with everyday communication, prevents return to work (Graham et al., 2011) and has dramatic consequences for health-related quality of life (Lam and Wodchis, 2010). For several decades, functional MRI (fMRI) has been critical to the investigation of the neural substrates of post-stroke language processing. It has been used to localize and characterize language functions in people with aphasia (PWA), to monitor changes in brain function over the course of recovery or in response to intervention, and to inform theories of language recovery and rehabilitation (see Simic et al., 2023; Wilson and Schneck, 2020, for recent reviews and meta-analysis of this literature).

The majority of aphasia neuroimaging research has utilized task-based paradigms, in which participants perform language activities intended to engage relevant regions of the brain. Recently, however, resting-state fMRI has become an increasingly popular and appealing alternative to task-based fMRI. During resting-state fMRI, participants lie in the MRI scanner and remain awake, but are not engaged in an overt, externally driven task. While a variety of techniques are used to analyze resting-state fMRI data, a common approach is to compute functional connectivity, or correlations in the blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) timeseries between voxels and/or anatomically or functionally defined regions (i.e., clusters of voxels) throughout the brain. These correlations may be used in subsequent statistical analyses, for example, to investigate associations between functional connectivity and behavioral measures or differences in functional connectivity between groups of subjects (e.g., patients vs. controls). Correlation-based functional connectivity can also serve as the basis for network analyses that aim to describe the organization and characteristics of brain networks, subnetworks, and individual nodes within a network (Bullmore and Sporns, 2009; Rubinov and Sporns, 2010). Functional connectivity can also be derived from data acquired using task-based fMRI paradigms (Fair et al., 2007), an approach that has been used in some studies of post-stroke language rehabilitation (Johnson et al., 2020; Tao and Rapp, 2019). Nevertheless, resting-state paradigms are particularly appealing for studying aphasia for several reasons, as outlined by Klingbeil and colleagues (2019). For example, resting-state scans do not depend on a participant's ability to perform a task, making them accessible to individuals with moderate and/or severe aphasia or regardless of their unique deficit profile. Additionally, Klingbeil and colleagues note that whereas task-based paradigms are meant to drive activation in a specific region or set of regions at the exclusion of others (i.e., language but not visual, motor, or attention processing areas), a single resting-state scan can provide information about the many networks associated with a variety of cognitive functions or domains. Also, because they do not require participant training or specialized software or hardware (like sensitive MRI-compatible microphones or manual response systems), resting-state state scans can be performed on virtually any MRI scanner. Collectively, these qualities make resting-state fMRI a feasible addition to routine clinical MRI protocols (Klingbeil et al., 2019). We would also add that for the same reasons, resting-state scans can likely be more easily incorporated into large, multi-site research studies than task-based paradigms and, since it is not dependent on task performance or response accuracy, resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) may be more useful than task-based fMRI for tracking changes in brain function—especially at the level of systems/networks—over time and in response to treatment.

A number of studies have employed resting-state fMRI specifically to investigate aphasia. For example, several studies reported that PWA have abnormal functional connectivity relative to controls in various networks or individual connections (e.g., Balaev et al., 2016; Ramage et al., 2020; Sandberg, 2017; Yang et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2014). Associations between functional connectivity in PWA and their language abilities and/or treatment outcomes have also been reported (e.g., Baliki et al., 2018; Billot et al., 2022; Bitan et al., 2018; Marangolo et al., 2016; Ramage et al., 2020; van Hees et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014). These papers provide a few examples of how resting state functional connectivity is being employed to provide insight into aphasia and language recovery. However, to evaluate the extent to which the implications of studies like these are valid and replicable, and especially to determine if RSFC can and should be used to index language recovery in longitudinal contexts, its test-retest reliability in people with aphasia must be established.

Test-retest reliability characterizes the stability or consistency of an instrument or variable across repeated measurements and therefore has implications for how changes in that variable are interpreted. For example, if functional connectivity is observed to change after a patient receives treatment, it is critical to know if a similar change could have occurred by chance (i.e., absent intervention) before attributing the change to the treatment.

The test-retest reliability of functional connectivity in neurologically healthy individuals (i.e., those with no history of stroke or brain damage) has been a topic of interest for more than a decade. A meta-analysis of 25 papers found the reliability of individual functional connections (also referred to as edges) was poor, on average (Noble et al., 2019). It is possible that the low level of reliability reflects instability in the cognitive processes that take place during scanning. In a resting state paradigm, these processes are unknown, unmeasured, and may fluctuate considerably from one session to another depending on factors like the time of day or a participant's emotional or psychological state. However, Noble and colleagues also identified several variables that are likely associated with better reliability, including the amount of data obtained (i.e., longer scan durations/more data > shorter durations/less data), time between sessions (i.e., shorter inter-session intervals > longer inter-session intervals), scanning with eyes open (as opposed to closed), edges' participation in functional subnetworks (i.e., edges connecting regions in the same subnetwork > edges connecting regions in different subnetworks), edge strength (i.e., stronger edges > weaker edges), and specific choices made in the applied data processing and analysis procedures (Noble et al., 2019, 2021). The majority of studies in Noble et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis had relatively short scan durations and relatively long inter-scan intervals. Moreover, in a brain network comprising several modular subnetworks, there are logically far more edges between subnetworks than within them; collectively, these factors may explain why average reliability was poor in the meta-analysis. Importantly, however, despite the low average reliability across studies, a few studies reported reliability in the fair-to-good range, and several of the same factors described above (especially those that are methodological in nature) represent mechanisms by which reliability can likely be improved.

Crucially, whether resting-state functional connectivity is reliable in PWA is currently unknown, as is the extent to which it might be influenced, or even optimized, by variables associated with reliability in healthy controls. Likewise, the degree to which findings from control studies generalize to PWA is uncertain, for several reasons. Stroke survivors, including PWA, may have an abnormal hemodynamic response relative to healthy controls (Bonakdarpour et al., 2007; Pineiro et al., 2002; Siegel et al., 2017), and Higgins and colleagues found that task-related functional activation was less reliable in PWA than healthy controls (Higgins et al., 2020). Furthermore, given the nature of their deficits and the location of their strokes, PWA are likely to experience different patterns of functional organization and reorganization from controls and other stroke survivors, which could make the language subnetwork in PWA particularly less stable. Finally, to our knowledge, no study yet has explicitly examined the reliability of functional connectivity in individuals with aphasia. Given that resting-state paradigms are already in use with PWA, it is critical to evaluate the reliability of functional connectivity in this population. Furthermore, it will be valuable to determine if variables associated with reliability in controls similarly affect reliability in PWA—especially those variables that can be manipulated to enhance reliability.

Therefore, to investigate RSFC in aphasia, we analyzed a convenience sample of data from 14 participants in an ongoing aphasia therapy trial. Of note, participants in the clinical trial also completed post-treatment scans, and one of the sub-aims of that study is to examine changes in resting-state functional connectivity associated with treatment; however, only pre-treatment data were included in the present study.

While small, our sample was well-suited to address the questions of interest given the design of the larger clinical trial from which the data were obtained: participants underwent resting-state fMRI on two separate days without treatment in the intervening period; scan durations and inter-scan intervals were tightly controlled, and all participants met the same behavioral and demographic inclusion criteria (see section 2.1, below). Certainly, prospective studies on this topic should include more participants, but our sample is sufficient to provide preliminary insights and a methodological framework for future research, especially since functional connectivity studies of PWA have already been published and more are underway. With all of this in mind, the specific goals of the present study were to evaluate and characterize the edge-level test-retest reliability of functional connectivity in individuals with chronic aphasia, and to determine if and how any of several variables are associated with reliability. Variables of interest included:

-

•

Scan duration, given that resting state scan durations vary across aphasia studies and, as noted above, longer scan durations have been found to increase test-retest reliability (with diminishing returns) in healthy controls;

-

•

Edge strength (i.e., the magnitude of the correlation coefficient for a given edge), which is of interest because some connectivity and network construction approaches threshold weaker connections in order to focus subsequent analyses on more robust connections. Investigating the relationship between edge strength and reliability could help provide insight into whether these thresholding techniques risk excluding weak but reliable (and therefore potentially meaningful) connections;

-

•

Inter-node distance, or the physical distance between the nodes whose correlation constitutes an edge, which has been shown to relate to behavior and differentiate between controls and (non-aphasic) clinical populations (e.g., Alexander-Bloch et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014);

-

•

Membership of edges in known subnetworks (i.e., groups of nodes and/or edges purported to support the same cognitive functions). Various subnetworks have been investigated in prior aphasia connectivity studies (Balaev et al., 2016; Billot et al., 2022; Marcotte et al., 2013; Naeser et al., 2020), so it is of interest to determine if some networks (and, thus, inferences based on their properties) are more reliable than others;

-

•

Hemispheric distribution of edges, or whether an edge is in the left hemisphere, right hemisphere, or extends between the hemispheres. Our investigation of this property was motivated by the fact that aphasia is most typically caused by a left-hemisphere stroke, so the integrity of the two hemispheres differs considerably in this population and could plausibly have an impact on the reliability of functional connections. Additionally, there has been much debate about the contributions of the left and right hemispheres to language recovery and rehabilitation, and connectivity-based inferences about the roles of the hemispheres should ideally account for potential differences in their reliability.

We hypothesized that edges would tend to have poor to fair test-retest reliability and that reliability would be positively associated with longer scan durations, stronger connectivity, shorter physical distances between the nodes incident with the edges, membership in established subnetworks, and being located within the intact right hemisphere.

2. Materials and methods

This study was conducted at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) in Pittsburgh, PA, USA. All research activities were approved by the VAPHS Institutional Review Board. Informed consent to participate and be included in the study was obtained from all participants and documented in writing. Data sharing restrictions of the host institution for this research prevent public sharing of the dataset, but a de-identified dataset can be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

2.1. Participants

Participants in this study were a subset of individuals enrolled in an aphasia treatment trial at VAPHS between May 2021 and August 2023 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04215952). Inclusion criteria for the larger trial included: age ≥18 years; aphasia due to left-hemisphere stroke at least six months prior to enrollment; self-report of English as a first or primary language; auditory comprehension sufficient for participation in the experimental treatment as indicated by a Spoken Language Comprehension Modality Summary T-score of at least 40 on the Comprehensive Aphasia Test (CAT) (Swinburn et al., 2004); and naming impairment severe enough to allow for the selection of treatment stimuli in accordance with the trial's treatment protocol. Exclusion criteria included the presence of severe motor speech disorder, progressive neurological illness, prior central nervous system injury or disorder, significant and unmanaged behavioral or psychiatric illness, significant and unmanaged drug or alcohol dependence, and inability to participate in 3-4 h of daily language treatment over a three-week period. The clinical trial was still in data collection when the present study was submitted, but many aspects of the larger trial design have been detailed by Babiak et al. (2025).

In addition to meeting the criteria listed above and enrolling in the clinical trial, participants in the present study were MRI-eligible and completed two resting-state fMRI scans prior to receiving any treatment. As noted previously, all data analyzed and reported here were collected before participants received treatment when both language abilities and brain function were assumed to be relatively stable due to the chronicity of their aphasia.

Seventeen participants with aphasia were enrolled in the clinical trial during the relevant period. Two participants were excluded from the present study because they could not safely undergo MRI scanning, and one was excluded due to falling asleep during the resting-state scans. Thus, 14 adults with chronic aphasia were included in the present study (10 male/4 female; mean age = 63.18 years, SD = 10.80 years); see Table 1 for demographic data and Fig. 1 for a lesion distribution map. Their aphasia severity was slightly above the mean relative to the larger population of adults with aphasia, as indicated by their average mean modality T-score on the CAT.

Table 1.

Participant demographic data. CAT = Comprehensive Aphasia Test mean modality T-score. Number of Damaged (Excluded) ROIs indicates the number of ROIs with >10 % damage, which were subsequently excluded from analysis using the liberal network construction approach described in section 2.3.3.

| Subject | Age (years) | Sex | Months Post-Onset of Aphasia | Lesion Volume (cc) | CAT | Days Between Scans | Number of Damaged (Excluded) ROIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 53.16 | F | 103.30 | 125.03 | 45.67 | 4.00 | 24.00 |

| 10 | 53.80 | M | 28.20 | 129.74 | 53.92 | 2.00 | 29.00 |

| 13 | 45.71 | M | 22.10 | 25.30 | 63.92 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| 17 | 75.62 | F | 35.30 | 39.36 | 48.00 | 4.00 | 9.00 |

| 18 | 77.09 | F | 48.00 | 68.39 | 44.92 | 4.00 | 14.00 |

| 20 | 62.38 | M | 63.00 | 94.87 | 52.00 | 4.00 | 22.00 |

| 21 | 64.88 | M | 122.30 | 27.72 | 57.92 | 4.00 | 9.00 |

| 22 | 74.97 | M | 87.90 | 155.19 | 51.00 | 2.00 | 26.00 |

| 23 | 74.87 | M | 124.70 | 34.82 | 56.83 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| 29 | 67.06 | F | 267.00 | 39.90 | 58.30 | 5.00 | 7.00 |

| 30 | 72.05 | M | 13.40 | 107.01 | 51.90 | 5.00 | 29.00 |

| 37 | 60.37 | M | 21.00 | 52.90 | 57.10 | 4.00 | 13.00 |

| 38 | 53.53 | M | 38.00 | 89.20 | 45.10 | 2.00 | 24.00 |

| 40 | 49.05 | M | 87.00 | 168.04 | 45.30 | 4.00 | 30.00 |

| M | 63.18 | - | 75.80 | 82.68 | 52.28 | 3.71 | 17.43 |

| SD | 10.80 | - | 66.90 | 48.62 | 6.00 | 0.99 | 9.80 |

Fig. 1.

Participant lesion map. The color bar reflects the number of subjects with a lesion in each voxel, with dark red indicating fewer subjects and pale yellow indicating more subjects. Lines on the reference brain at right show the vertical position of slices, with the bottom line corresponding to the left-most slice.

2.2. Study design

At study enrollment and again several days later, participants were administered the Comprehensive Aphasia Test by a speech-language pathologist to assess their aphasia severity. Participants completed two MRI sessions (i.e., session 1 and session 2), separated by an average of 3.71 days (SD = 0.99; range = 2–5 days). Participants did not receive speech-language therapy during the time between MRI sessions.

2.3. MRI methods

2.3.1. Data acquisition

MRI data were acquired with a Siemens 3T Prisma scanner with a 64-channel head coil at the CMU-Pitt Brain Imaging Data Generation and Education (BRIDGE) Center in Pittsburgh, PA. At session 1, T1 MPRAGE and T2 FLAIR structural scans were completed. At sessions 1 and 2, two 6-min T2∗ resting-state functional scans were obtained with a brief (∼30 s) break in between, during which research staff verified that the participant was awake and comfortable continuing the session. During resting-state scans, participants were presented with a white fixation cross on a black background and instructed to remain awake with eyes open.

Acquisition parameters for the T1 structural images were as follows: TR = 2300ms, TE = 1.99ms, 176 sagittal slices, 1 mm3 voxels, matrix = 256 x 256, flip angle = 9°, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2 with 24 reference lines in the phase encoding direction. Parameters for T2 FLAIR were: TR = 6000ms, TE = 388ms, TI = 2200ms, 208 sagittal slices, 1 mm3 voxels, matrix = 256 x 240, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2 with 32 reference lines in the phase encoding direction. T2∗ resting-state functional sequence parameters were: TR = 1000ms, TE = 30ms, 78 axial slices (auto-aligned to the AC-PC line), 2.5 mm3 voxels, matrix = 86 x 86, flip angle = 64°, multi-slice interleaved acquisition with multi-band acceleration factor of 6, scan duration = 6 min/run (360 vol/run). To allow for correction of geometric distortions in the functional images, a Siemens double-echo gradient field map sequence was acquired immediately before the first resting-state scan at each session, with TR = 761ms, TE 1 = 4.87 ms, TE 2 = 7.33ms, and the same geometry as the resting-state sequences.

Several other functional and diffusion-weighted imaging sequences were completed as part of the larger clinical trial, but they are not described here because they are not relevant to the present study.

2.3.2. Preprocessing

Each participant's T1 and T2 FLAIR structural images were coregistered using SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12). Lesion masks were drawn by the lead author on the T1 image, with reference to the T2 FLAIR as needed, using MRIcron or MRIcroGL (Rorden and Brett, 2000). SPM12's FieldMap Toolbox was used to derive an unwarped field map from the Siemens field map images. Next, SPM12's Realign & Unwarp and Slice Timing functions were used to correct for head motion, geometric distortion (using the field map), and slice timing differences in the functional images, and the T1 structural image and lesion mask were coregistered to the mean functional image. Functional images were normalized to MNI space using SPM12's normalization function and T1 structural images and lesions masks were normalized to MNI space using the MR segment-normalize routine with enantiomorphic normalization (Nachev et al., 2008) from the Clinical Toolbox for SPM (Rorden et al., 2012). SPM12's segmentation function was applied to the normalized structural images to obtain gray matter, white matter, and CSF masks.

2.3.3. Defining nodes and edges for the connectivity network

An essential step in functional connectivity analysis is defining the brain space/network to analyze, which often begins by selecting a set of regions (or nodes) that represent the anchor points between which functional connectivity will be calculated. Nodes can be defined as individual voxels or as groups of voxels organized according to anatomical structure or functional properties. While numerous schemas have been developed for this purpose, we elected to use a functional parcellation created by Power et al. (2011), which we subsequently refer to as the Power parcellation and/or Power network. The Power parcellation comprises 264 functional nodes distributed throughout the brain (including cortical and subcortical structures), which were identified using a meta-analytical approach. It has been used in several aphasia studies (e.g., Baliki et al., 2018; Tao and Rapp, 2019; Chen et al., 2021), as well as investigations of the reliability of resting-state connectivity and network characteristics (Cao et al., 2014; Xiang et al., 2020).

For the present study, we used custom scripts for MATLAB (https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html) and the MarsBar Toolbox (Brett et al., 2002) to create 264 10 mm diameter spherical regions of interest (ROIs) centered at the locations identified by Power et al. To account for participants' lesions, we intersected each subject's lesion mask with the 264 ROIs and deleted any overlap from the ROIs, following a method described in Johnson et al. (2019). This procedure resulted in a unique set of ROIs for each participant that consisted of only the spared portion of each sphere. We calculated the proportion of each spared ROI relative to its original volume and ROIs that were less than 90 % spared were flagged for exclusion from subsequent analyses using two approaches.

In the first, liberal approach, ROIs that were more than 10 % damaged were excluded on a subject-by-subject basis and functional connectivity was computed among all pairs of surviving, spared ROIs for each subject; edges that were not present in at least half the sample (i.e., 7 subjects) were then subsequently excluded from further analysis.

In the second, conservative approach, ROIs that were more than 10 % damaged in any subject were excluded from analysis across the entire sample, and functional connectivity was computed among all pairs of surviving ROIs.

The liberal approach had the advantage of retaining more data (i.e., more ROIs and edges) than the conservative approach, though all subjects did not contribute to all reliability estimates (since some ROIs and edges were spared in some subjects and excluded in others). In contrast, the conservative method established consistency in the size of the network across subjects and ensured that all subjects contributed to the reliability estimates for every edge.

2.3.4. Computing functional connectivity

Functional connectivity was computed on a subject-by-subject basis using the CONN Toolbox (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012). Subjects' preprocessed, normalized structural and functional images and lesion-adjusted ROIs (as described in sections 2.3.2, 2.3.3, respectively) were provided as input to CONN. Outliers in the functional images were identified using CONN's default intermediate detection thresholds, which flag as outliers those volumes with framewise displacement greater than 0.9 mm or global BOLD signal changes above 5 standard deviations from the mean BOLD signal (Nieto-Castanon, 2020b). Next, to account for the effects of potential confounds in the BOLD signal, CONN's default denoising pipeline was applied (Nieto-Castanon, 2020a). This pipeline uses the aCompCor method (Behzadi et al., 2007) to identify principal components of the signal in white matter (WM) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (i.e., signals of no interest). The first five WM and CSF components, as well as the subject's realignment (motion) parameters, volumes flagged as outliers in the previous step, and session effects (i.e., session 1 vs. session 2) were regressed from the BOLD signal in each voxel, and the data were subsequently temporally bandpass filtered at 0.008–0.09 Hz.

Next, CONN was used to calculate bivariate correlations in the denoised BOLD time series between every pair of ROIs (based on the average timeseries within each ROI) in the network for each subject. These correlation coefficients were Fisher transformed to allow for second-level inference. Within each session, the two resting-state runs were concatenated, resulting in a total of 12 min of data (720 vol) per session. Separate connectivity coefficients were derived for session 1 and session 2. This method assumes that connections are bidirectional (i.e., the coefficient for ROI 1 → ROI 2 = the coefficient for ROI 2 → ROI 1); thus, redundant connections and self-connections (which by their nature have a correlation coefficient of 1) were excluded from subsequent analysis.

To support our investigation of the relationship between test-retest reliability and scan duration, we used an approach modeled after Birn et al. (2013). Specifically, within each session, the data from runs 1 and 2 were trimmed and concatenated in the order in which they were acquired in order to obtain 10 timeseries ranging from 3 to 12 min long (i.e., 60 to 720 vol) in 1-min increments. Outlier detection, denoising, and calculation of functional connectivity were performed for each duration/timeseries, as described above.

2.3.5. Characterizing test-retest reliability

Because edges (i.e., functional connections) are a foundational unit of functional connectivity and given our group's potential interest in exploring edge-level connectivity in future studies, we set out to characterize the reliability of individual edges in the Power network and various subnetworks. The reliability metric we selected was the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979), which has been widely used in neuroimaging and more general reliability research (Koo and Li, 2016; Noble et al., 2021). There are several formulations for the ICC, which vary depending on the structure and nature of the data and the purpose of the analysis (see Koo and Li, 2016, for an overview), but in general, the ICC quantifies the ratio of between-subjects variance (i.e., the variance of interest) to the total variance plus error (Noble et al., 2021; Shrout and Fleiss, 1979). In the present study, we used the two-way random effects, single-rater ICC model for absolute agreement (ICC(2,1)), which treats both subjects and raters (i.e., the scanner, which is performing the measurements) as random effects, since they were drawn from the larger populations of people with aphasia and scanners, respectively. This form of ICC is computed via the following formula:

where is between-subjects variance, is between-sessions variance, and is the residual variance.

To be clear, for the analyses described in section 2.3.6, below, we obtained the ICC for every available edge (i.e., all edges except those excluded due to subjects’ lesion damage) in the Power network and various subnetworks.

2.3.6. Analyses and statistics

After functional connectivity data were processed and computed in CONN, they were transferred to R (R Core Team, 2023; RStudio Team, 2019) for further analysis; the ‘irr’ package was used to compute ICCs (Gamer et al., 2019) and ‘ggplot2’ was used for visualizations (Wickham, 2016). R code for complex data management and analysis was generated with assistance from Perplexity (https://www.perplexity.ai/), an AI-driven search engine that utilizes several large language models and provides sources for its responses. Analyses based on AI-generated code were carefully verified by comparing results to those from simplified code generated by the first author.

The following sections describe the procedures used to address each of the aims of the study.

2.3.6.1. Reliability of resting-state functional connectivity and its association with scan duration

To evaluate the test-retest reliability of RSFC in PWA, we calculated the ICC for every edge in the Power network after excluding damaged ROIs per the liberal and conservative approaches described in section 2.3.3. This analysis was performed using each of the timeseries datasets ranging in 1-min increments from the first 3 min obtained at both MRI sessions up through the maximal 12 min acquired at each session. For each scan duration, we examined the distribution of edge-level ICCs and two measures of their central tendency (mean and median). ICCs were interpreted using the following benchmarks: <0.4 = poor; 0.4 to 0.59 = fair; 0.6 to 0.74 = good; ≥0.75 = excellent (Cicchetti and Sparrow, 1981).

To examine the relationship between reliability and scan duration, we performed a linear regression with median ICC as the dependent variable and scan duration as the independent variable.

2.3.6.2. Associations between reliability and edge strength and inter-node distance

To determine if stronger functional connections (i.e., those with larger magnitude connectivity coefficients) were more reliable than weaker connections, we first calculated the mean connectivity coefficient for every edge (averaging over subjects) in the maximal (12-min) dataset at session 1 and, separately, session 2. We found that the average coefficients at session 1 and 2 were highly correlated (r = 0.90), so we subsequently averaged the session 1 and session 2 coefficients to obtain an average (over subjects and sessions) connectivity coefficient for every edge. Next, we ran a linear regression where edge ICC values were the dependent variable, and the absolute value of edge strength was the independent variable.

To determine if the reliability of edges was associated with their inter-node distance (i.e., the physical distance between the nodes comprising an edge), we calculated the Euclidean distance in mm between the coordinates at the center of every pair of ROIs and then regressed the edges’ ICCs on these distances.

2.3.6.3. Reliability in known cognitive and language-related subnetworks

A benefit of using the Power parcellation to define the network in this study is that Power and colleagues (2011) assigned their nodes to 13 functional subnetworks (which they referred to as systems). To assess the reliability of edges in these subnetworks, we identified the surviving (i.e., non- or minimally damaged) nodes in each subnetwork, extracted the ICCs among their edges, and examined their distributions and median ICCs.

Notably, Power et al. (2011) did not identify a language-specific subnetwork, but given the population of interest and the nature of their deficits, we sought to evaluate the reliability of a language network. The localization of language functions in the brain has been widely investigated and many regions have been linked to both typical and post-stroke language processing. While it was beyond the scope of this study to evaluate the many language atlases/parcellations that have been proposed, we investigated two language subnetworks that were defined using different approaches.

The first language network was defined based on Roger et al. (2022), who identified a subset of 131 of Power et al.’s (2011) ROIs that constituted nodes in a “general language connectome,” which Roger et al. referred to as LANG, as well as four subnetworks within LANG, to which they attributed several specific linguistic functions. Notably, LANG was not a fully connected network and instead comprised a subset of approximately 3470 edges (E. Roger, personal communication, August 23, 2024). For the present study, we started with the list of LANG edges (provided by E. Roger, August 26, 2024) and computed ICCs for all of those that were present and considered intact in our sample of PWA.

For the second language network, we started with several language parcels (i.e., functionally defined brain areas with a high probability of containing language-responsive tissue across subjects) that were created and used by Fedorenko and colleagues in their extensive research on language in the brain (e.g., Fedorenko et al., 2010; Pereira et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2023). Using custom Matlab scripts, we identified and retained the subset of ROIs from the Power network that intersected with any of the Fedorenko parcels (which are publicly available at https://evlab.squarespace.com/resources), and then computed ICCs for all of the edges formed by the pairwise combinations of those ROIs. As with the Power subnetworks, we examined the distributions and median values of ICCs for edges in the Roger- and Fedorenko-based language subnetworks.

The procedures above provided insight into the reliability of edges in 15 subnetworks (13 Power subnetworks and two language subnetworks), but they did not indicate if those functionally relevant subnetworks were more reliable than random subnetworks. Thus, we performed a subsequent analysis using permutation tests, wherein for each subnetwork, we selected 2000 sets of randomly chosen edges whose functional connectivity strength and inter-node distance were matched to those of the edges in the actual subnetwork. Each random set was also equal in size (edge count) to the subnetwork in question. Next, we computed the ICCs of the edges in each of the 2000 sets, as well as the median ICC of each set, resulting in an empirical null distribution. We compared the median ICC for the true subnetwork (as identified in the initial subnetwork reliability analysis) to the empirical null distribution, calculating the proportion of median ICCs from the random subnetworks that were greater than the true median ICC for the corresponding subnetwork; that proportion was interpreted as a p-value representing the probability of obtaining a median ICC at least as extreme as the real ICC from a randomly constructed subnetwork with similar properties (i.e., by chance). The p-values for each subnetwork, and corresponding q-values (FDR-corrected p-values) were compared to an a priori alpha of 0.05 to determine significance.

We also sought to evaluate how the reliability of subnetworks compared to that of the entire brain. Using the ‘boot’ package in R (Canty and Ripley, 2024), we used nonparametric bootstrapping to estimate 95 % confidence intervals around the difference between the median ICC of each subnetwork and the full network (Efron and Tibshirani, 1986). Specifically, we used random sampling with replacement to create 1000 samples (n = 14 per sample) from our original participant sample. For each of these bootstrap samples, the following statistics were computed: the ICC of every edge in the whole-brain network and the corresponding median ICC; the ICCs of the edges in each cognitive and language subnetwork and their respective median ICCs; and the difference between each subnetwork median and whole-brain network median. For each subnetwork, the differences between the subnetwork and whole-brain median ICCs were rank ordered and the 25th and 975th values were taken as the limits of the 95 % confidence interval. Confidence intervals that included 0 were interpreted as evidence of no difference in the reliability between a subnetwork and the whole network, while those that excluded 0 were interpreted as indicative of a statistically significant difference in reliability.

2.3.6.4. Reliability of edges by hemisphere

We explored the reliability of edges based on the location of their nodes by sorting the Power network into three subsets: one for edges whose incident nodes were both in the left hemisphere, one for edges whose incident nodes were both in the right hemisphere, and one with one incident node in each hemisphere. We computed the ICCs for each of those subsets and examined their distributions and median ICCs. To evaluate the probability of obtaining median ICCs as extreme as those derived from the analysis above, we used the same permutation testing approach as described in section 2.3.6.3 for the analysis of subnetwork reliability (i.e., we constructed 2000 randomly drawn strength- and inter-node distance-matched networks of equal size to the actual left-, right, and interhemispheric networks described here, calculated the individual and median ICCs of edges in all 2000 sets, and compared the median ICCs from the actual hemispheric subnetworks to the random subnetworks).

To determine if reliability differed according to edge location, 95 % confidence intervals around the differences in median ICCs for left-sided, right-sided, and interhemispheric edges were constructed using nonparametric bootstrap resampling. In short, for each of the bootstrap samples generated to compare the subnetworks to the whole brain, individual and median ICCs were also obtained for left-hemisphere, right-hemisphere, and interhemispheric edges, as were the pairwise differences between the medians (i.e., right hemisphere – left hemisphere, right hemisphere – interhemisphere, left hemisphere – interhemisphere). As above, the differences were rank ordered and the 25th and 975th values were taken as limits of the 95 % confidence intervals, with confidence intervals that excluded 0 interpreted as indicating a significant difference between hemispheres.

3. Results

3.1. Network construction

Using the conservative approach to network construction described in section 2.3.3, 66 of the Power network ROIs were excluded from analysis across the group, leaving a total of 198 ROIs and 19,503 unique edges for analysis after excluding redundant and self-connections. In contrast, the more liberal method of retaining ROIs on a subject-by-subject basis and excluding edges that were not present in at least half the sample produced a network comprising 260 ROIs and 33,209 edges. The ROIs retained after each approach are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

All the primary test-retest reliability analyses were performed on datasets defined using both the liberal and conservative approaches. Though not identical, the results were generally consistent between the two approaches; thus, the results for the liberal approach are reported in the main text, and results for the conservative approach are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

3.2. Test-retest reliability

3.2.1. Overall reliability and scan duration

The test-retest reliability of edges in the Power network for durations from 3 to 12 min is shown in Fig. 2 and corresponding summary statistics are in Table 2. Based on mean ICC values, the average edge had poor reliability (<0.4) for scan durations from 3 to 11 min and fair reliability (>0.4) at 12 min. However, the median was arguably a more appropriate measure of central tendency in this case, given that the data distributions across edges at all durations were negatively skewed. Based on the median values, the typical edge had poor reliability from 3 to 9 min of scan time and fair reliability from 10 to 12 min.

Fig. 2.

Test-retest reliability in the Power network after excluding damaged ROIs/edges using the liberal exclusion approach. Histograms show the number of edges across the range of ICCs (Frequency) for 33,209 edges at scan durations of 3–12 min. Mean and median ICCs for each duration are shown in the top left and right corners, respectively, and are represented by the dashed red (mean) and solid blue (median) lines on each histogram.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of reliability by scan duration. Q1/Q3: first and third quartiles.

| Scan Duration (minutes) | ICC Statistics |

Percentage of Edges with ICCs in Qualitative Benchmark Ranges |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Poor (<0.4) | Fair (0.4–0.59) | Good (0.6–0.74) | Excellent (≥0.75) | |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.19 | −0.03 | 0.39 | 74.06 | 17.34 | 5.48 | 1.12 |

| 4 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 69.91 | 20.68 | 7.43 | 1.98 |

| 5 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 65.45 | 22.26 | 9.56 | 2.73 |

| 6 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 60.93 | 24.04 | 11.31 | 3.72 |

| 7 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.51 | 60.22 | 24.19 | 11.79 | 3.81 |

| 8 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.54 | 55.96 | 25.59 | 13.60 | 4.86 |

| 9 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.57 | 52.26 | 26.84 | 14.84 | 6.06 |

| 10 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 49.61 | 27.15 | 16.19 | 7.05 |

| 11 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.61 | 46.62 | 27.55 | 17.35 | 8.49 |

| 12 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.62 | 44.59 | 27.96 | 18.44 | 9.01 |

Based on the histograms and summary statistics described above, reliability appeared to increase in conjunction with scan duration, but a plot of median ICCs against duration suggested the relationship might not be strictly linear (Fig. 3). We therefore constructed a model to regress the median ICC on linear and quadratic terms for duration, which fit the data better than the linear model (linear model AIC = −54.07, quadratic model AIC = −62.94). The quadratic model revealed a significant positive relationship between median ICC and the linear term for duration (β = 0.046, SE = 0.006, p < 0.001), meaning that reliability did, indeed, increase with duration. However, the quadratic term was significantly negatively associated with ICC (β = −0.001, SE = 0.000, p = 0.008), indicating that the rate of increase in the median ICC tapered off toward higher durations.

Fig. 3.

Reliability (median ICC) by scan duration. Error bars represent 1st and 3rd quartiles. Blue trendline shows the predicted median ICC across durations based on the regression model described in the main text.

In reviewing the results depicted in Fig. 2, it was clear that a considerable proportion of edges had negative ICCs, regardless of scan duration. Because negative ICCs are challenging to interpret, prior resting state functional connectivity investigations have treated them as 0 (i.e., not at all reliable) by adjusting negative variance components to zero (producing an ICC = 0), directly converting negative ICCs to 0, or otherwise restricting interpretations to positive ICCs (e.g., Kong et al., 2007; Song et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2014; Andellini et al., 2015; Dufford et al., 2021). To evaluate the impact that converting negative ICCs to 0 could have on our data, as well as future studies of test-retest reliability in PWA, we conducted a two-part follow-up analysis. First, we ran a linear regression to determine if the number of edges with negative ICCs was associated with scan duration. Second, we converted all negative ICCs to 0 and recalculated the measures of central tendency (mean and median) as reported above.

The regression model indicated there was a significant negative association between scan duration and negative ICCs (β = −613.01, SE = 59.03, p < 0.001), such that for each additional minute of scan time, the number of edges with negative ICCs decreased by about 613. The second part of the analysis indicated that when negative ICCs were converted to 0, the mean ICC at each duration increased slightly and the standard deviation shrunk; in contrast, there was virtually no impact on the median and first and third quartiles (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of converting negative ICCs to 0 on measures of central tendency and variability of test-retest reliability. Bold and italics indicate summary statistics whose value changed when negative ICCs were converted to 0.

| Scan Duration | # of Negative ICCs | Original ICC Summary Statistics |

ICC Summary Statistics After Converting Negatives to 0 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Mean | SD | Median | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| 3 | 9605 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.19 | −0.03 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.39 |

| 4 | 7648 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.44 |

| 5 | 6348 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.48 |

| 6 | 5520 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.51 |

| 7 | 5363 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.51 |

| 8 | 4725 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.54 |

| 9 | 4211 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.57 |

| 10 | 3742 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.59 |

| 11 | 3384 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.61 |

| 12 | 3098 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.62 |

Because the initial analyses showed that reliability was highest for the longest scan duration, all subsequent analyses were performed using the 12-min dataset without converting negative ICCs to 0; a depiction of edge-level ICCs for the full network at 12 min relative to their locations in the brain is provided in Supplementary Fig. 2.

3.2.2. Reliability and edge strength

As noted previously and shown in Fig. 2, the distribution of ICCs was negatively skewed, so a Fisher transformation was applied to normalize them before regressing them on other variables. ICCs for 2/33,209 edges could not be transformed because they were below −1, so they were subsequently omitted from analyses of the Fisher-transformed ICCs.

An initial regression model with reliability of edges (Fisher-transformed ICCs) in the 12-min dataset as the dependent variable and edge strength (the absolute value of the average correlation coefficient at session 1 and session 2) as the independent variable was concerning for heteroscedasticity and non-normality of the residuals, so several polynomial models were constructed. Ultimately, the best-fit model, as indicated by AIC, included linear, quadratic, and cubic terms for edge strength. The linear and quadratic terms were significantly positively associated with reliability (linear term: β = 1.48, SE = 0.10, p < 0.0001; quadratic term: β = 1.12, SE = 0.52, p = 0.03), while the cubic term was significantly negatively associated with reliability (β = −3.85, SE = 0.71, p < 0.0001). Together, these effects indicate that edge reliability increased with strength to a point, then slowed down and decreased as strength continued to increase (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Edge reliability relative to strength and inter-node distance. Trendlines show predicted Fisher-transformed ICC values based on the models described in the text.

3.2.3. Reliability and inter-node distance

The regression model between edges’ reliability (Fisher-transformed ICCs) and inter-node distance revealed a weak but significant negative association (β = −0.002, SE = 0.00, p < 0.0001), meaning reliability decreased by 0.002 for each 1 mm increase in the distance between two nodes (Fig. 4B).

3.2.4. Reliability in cognitive and language subnetworks

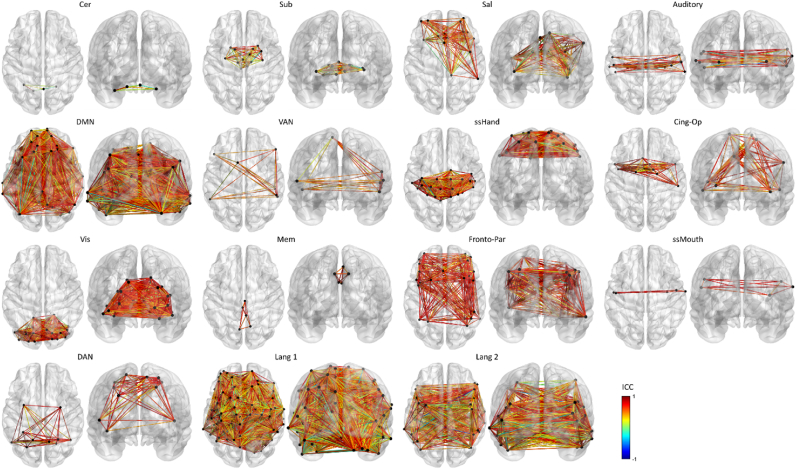

After excluding ROIs and edges due to damage as described in the methods, we calculated edge-level and median ICCs in each of the 13 Power subnetworks and the Roger- and Fedorenko-based language subnetworks. Edge-level ICCs are shown by subnetwork in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 6 and Table 4, based on median ICCs, the reliability of the typical edge was excellent (≥0.75) in two subnetworks, good (0.6–0.74) in six subnetworks, and fair (0.4–0.59) in six subnetworks, and in all but one instance (the cerebellar subnetwork), the subnetworks had higher median ICCs than the full Power network.

Fig. 5.

Reliability of edges in cognitive and language subnetworks. Results are presented in ascending order of reliability (median ICC) for the cognitive subnetworks first, followed by the two language subnetworks. Colors represent ICC values, with dark blue indicating the lowest reliability and dark red indicating the highest reliability. Subnetwork abbreviations/acronyms: Cer: cerebellar; Sub: subcortical; Sal: salience; DMN: default mode network; VAN: ventral attention network; ssHand: hand somatosensory-motor; Cing-Op: cingulo-opercular control; Vis: visual; Mem: memory retrieval; Fronto-Par: fronto-parietal control; ssMouth: mouth somatosensory-motor; DAN: dorsal attention network; Lang 1: Roger-based language network; Lang 2: Fedorenko-based language network.

Fig. 6.

Histograms showing ICCs for edges in the Power subnetworks (rows 1–3; row 4, panel 1) and language subnetworks (row 4, panels 2 and 3). Dashed vertical lines mark the median ICC for each subnetwork. Subnetwork abbreviations/acronyms: Cer: cerebellar; Sub: subcortical; Sal: salience; DMN: default mode network; VAN: ventral attention network; ssHand: hand somatosensory-motor; Cing-Op: cingulo-opercular control; Vis: visual; Mem: memory retrieval; Fronto-Par: fronto-parietal control; ssMouth: mouth/face somatosensory-motor; DAN: dorsal attention network; Lang1: Roger-based language network; Lang2: Fedorenko-based language network.

Table 4.

Reliability in cognitive and language subnetworks, including results of the permutation testing-based estimates of statistical robustness of subnetwork reliability. Results are listed in ascending order of reliability (median ICC) for the cognitive subnetworks first, followed by the two language subnetworks. Subnetwork abbreviations/acronyms: Cer: cerebellar; Sub: subcortical; Sal: salience; DMN: default mode network; VAN: ventral attention network; ssHand: hand somatosensory-motor; Cing-Op: cingulo-opercular control; Vis: visual; Mem: memory retrieval; Fronto-Par: fronto-parietal control; ssMouth: mouth/face somatosensory-motor; DAN: dorsal attention network; Lang 1: Roger-based language network; Lang 2: Fedorenko-based language network. q-values: p-values after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Bold values indicate significance at p or q < 0.05.

| Subnetwork | Subnetwork Size (ROIs/Edges) | Median ICC | Q1 | Q3 | # Random Subnetworks w/Median ICC ≥ Actual Median | p-value (Probability of Random Median ICC ≥ True Median ICC) | q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cer | 4/6 | 0.199 | 0.043 | 0.376 | 2000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Sub | 13/78 | 0.460 | 0.234 | 0.642 | 1586 | 0.793 | 0.850 |

| Sal | 18/153 | 0.562 | 0.418 | 0.684 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Auditory | 11/52 | 0.578 | 0.408 | 0.744 | 50 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

| DMN | 57/1584 | 0.578 | 0.422 | 0.703 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| VAN | 8/27 | 0.601 | 0.420 | 0.719 | 51 | 0.026 | 0.032 |

| ssHand | 30/435 | 0.611 | 0.452 | 0.733 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Cing-Op | 14/90 | 0.627 | 0.498 | 0.726 | 37 | 0.019 | 0.031 |

| Vis | 31/465 | 0.647 | 0.509 | 0.743 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Mem | 5/10 | 0.656 | 0.548 | 0.761 | 150 | 0.075 | 0.087 |

| Fronto-Par | 24/270 | 0.699 | 0.589 | 0.785 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ssMouth | 5/10 | 0.754 | 0.622 | 0.828 | 51 | 0.026 | 0.032 |

| DAN | 11/52 | 0.756 | 0.616 | 0.821 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Lang 1 | 126/3121 | 0.455 | 0.236 | 0.634 | 20 | 0.010 | 0.019 |

| Lang 2 | 37/627 | 0.533 | 0.333 | 0.685 | 5 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

Next, we examined the robustness of the subnetwork median reliability coefficients by comparing them to median ICCs from 2000 random networks of equal size, with edges matched for functional connectivity strength and inter-node distance. With and without FDR-correction for multiple comparisons, the reliability of 12/15 subnetworks was greater than would be expected by chance. Fig. 7 shows true subnetwork median ICCs relative to distributions of the median ICCs from the corresponding random subnetworks; associated p- and q-values are reported in Table 4.

Fig. 7.

Distribution of median ICCs from random subnetworks corresponding to cognitive and language subnetworks. Median ICCs from the actual subnetworks are marked with vertical dashed lines. Subnetwork abbreviations/acronyms: Cer: cerebellar; Sub: subcortical; Sal: salience; DMN: default mode network; VAN: ventral attention network; ssHand: hand somatosensory-motor; Cing-Op: cingulo-opercular control; Vis: visual; Mem: memory retrieval; Fronto-Par: fronto-parietal control; ssMouth: mouth/face somatosensory-motor; DAN: dorsal attention network; Lang 1: Roger-based language network; Lang 2: Fedorenko-based language network.

Finally, we compared the reliability of each subnetwork to that of the whole-brain network. Eleven out of 15 bootstrap confidence intervals for differences between subnetwork and whole-brain median ICCs excluded 0 (see Table 5), indicating that most cognitive and language subnetworks were more reliable than the whole-brain network.

Table 5.

Bootstrap confidence intervals for the differences between the median ICCs of subnetworks and the whole-brain network, derived from nonparametric bootstrap resampling. Subnetwork abbreviations/acronyms: Cer: cerebellar; Sub: subcortical; Sal: salience; DMN: default mode network; VAN: ventral attention network; ssHand: hand somatosensory-motor; Cing-Op: cingulo-opercular control; Vis: visual; Mem: memory retrieval; Fronto-Par: fronto-parietal control; ssMouth: mouth/face somatosensory-motor; DAN: dorsal attention network; Lang 1: Roger-based language network; Lang 2: Fedorenko-based language network. q-values: p-values after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Confidence intervals that excluded 0 are marked in bold.

| Subnetwork (vs. whole brain) | True difference of medians (subnetwork median – whole-brain median in original sample) | 95 % confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Cer | −0.241 | −0.486, 0.091 |

| Sub | 0.020 | −0.188, 0.226 |

| Sal | 0.122 | 0.037, 0.196 |

| Auditory | 0.138 | −0.025, 0.286 |

| DMN | 0.138 | 0.086, 0.189 |

| VAN | 0.161 | 0.049, 0.262 |

| ssHand | 0.171 | 0.099, 0.236 |

| Cing-Op | 0.187 | 0.098, 0.279 |

| Vis | 0.207 | 0.084, 0.276 |

| Mem | 0.216 | 0.025, 0.353 |

| Fronto-Par | 0.259 | 0.210, 0.316 |

| ssMouth | 0.314 | 0.119, 0.407 |

| DAN | 0.316 | 0.153, 0.379 |

| Lang 1 | 0.015 | −0.014, 0.035 |

| Lang 2 | 0.093 | 0.020, 0.132 |

3.2.5. Reliability of edges by hemisphere

The reliability of edges within the left and right hemisphere and spanning the two hemispheres is shown in Fig. 8 and Table 6. All three sets of edges (left hemisphere, right hemisphere, and interhemispheric) had median values in the fair range (0.4–0.59). Based on comparisons to randomly generated networks of equal size, the median edge in the right hemisphere was significantly more reliable than would be expected by chance (q = 0.000) Reliability in left-hemisphere and interhemispheric edges was not different from chance.

Fig. 8.

Top row: Reliability of edges by hemisphere. Colors are as in Fig. 5, above. Middle row: Histograms showing reliability (ICCs) of edges by hemisphere. Bottom row: Histograms of median ICCs from random networks of edges corresponding to the actual number of edges in each hemisphere or running between hemispheres and matched for edge strength and inter-node distance to the actual edges within/between hemispheres. Dashed vertical lines indicate the actual median ICCs for each hemisphere. Inter: interhemispheric edges; Left: edges in the left hemisphere; Right: edges in the right hemisphere.

Table 6.

Reliability of edges by hemisphere, including estimates of statistical robustness based on comparison to random networks of equal size. q-values: p-values after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

| Hemisphere | Network Size (ROIs/Edges) | Median ICC | Q1 | Q3 | # Random networks w/Median ICC ≥ Actual Median | p-value (Probability of Random Median ICC ≥ True Median ICC) | q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interhemispheric | 260/16,836 | 0.429 | 0.216 | 0.608 | 2000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Left | 122/6920 | 0.438 | 0.207 | 0.620 | 1086 | 0.543 | 0.815 |

| Right | 138/9453 | 0.459 | 0.254 | 0.630 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Bootstrap confidence intervals for the differences between median ICCs of edges within or between hemispheres confirmed that right-hemisphere edges were significantly more reliable than left-hemisphere and interhemispheric edges, while the difference between left-hemisphere and interhemispheric edges was not significant (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Bootstrap confidence intervals for the differences between the median ICCs of edges within/between hemispheres, derived from nonparametric bootstrap resampling. Confidence intervals that excluded 0 are marked in bold.

| Comparison | True difference of medians | 95 % confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Right – Left | 0.021 | 0.006, 0.060 |

| Right – Interhemispheric | 0.030 | 0.018, 0.047 |

| Left – Interhemispheric | 0.009 | −0.015, 0.022 |

4. Discussion

For a number of reasons (e.g., lack of dependence on task performance, accessibility across severity levels, limited peripheral equipment requirements), resting-state functional connectivity is an appealing technique for studying neural function and monitoring changes over time and after intervention in individuals with aphasia. However, to determine how viable and informative the technique is, especially in longitudinal contexts (e.g., to evaluate treatment-related changes in brain and language function), it is crucial to establish its test-retest reliability and identify variables that may make it more or less reliable. While RSFC reliability has been investigated in neurologically healthy adults, no study to date has explicitly tested its reliability in adults with chronic aphasia. To address this gap, we examined the test-retest reliability of edge-level resting state functional connectivity in 14 adults with chronic (>6 months post-onset) post-stroke aphasia. Associations between reliability and several variables were explored, and analyses were conducted within a network of regions distributed throughout the entire brain, as well as in functional subnetworks and within and between hemispheres.

In general, we found that the reliability of edges in people with aphasia was variable, ranging from poor to excellent, with the distribution of ICCs—and corresponding measures of central tendency—increasing as scan duration increased. Functional connectivity strength and the distance between regions forming an edge were also associated with reliability, such that stronger connections were more reliable than weaker ones (with gains tapering off at longer durations), and edges between regions that were more proximal to each other were somewhat more reliable than those that were more distant from each other. Edges in a majority of functionally defined subnetworks were more reliable than the full network and more reliable than would be expected by chance, and edges within and between the hemispheres also tended to be fairly reliable, with greater reliability in the intact right than damaged left hemisphere. These findings and their potential implications are discussed in further detail below.

4.1. Edge resting-state reliability is variable in aphasia

With respect to the whole-brain network analyzed in this study, the optimal (i.e., most reliable) outcome was obtained using 12 min (the full amount available) of data per session and the liberal approach to handling damaged ROIs and edges (i.e., excluding ROIs on a subject-by-subject basis and retaining edges that were considered undamaged in more than 50 % of participants). These conditions yielded mean and median ICCs across the entire Power network in the “fair” range, and a distribution in which the reliability of approximately 55 % of edges was fair or better. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, our results suggest a more optimistic view of RSFC reliability than Noble et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis of 25 studies, which estimated an average edge-level ICC of 0.29. One explanation for the difference between our results and Noble et al.‘s is that their meta-analysis combined data from studies that varied widely in methodology, including network parcellation schemes and scales of connectivity analysis, whereas our results are based on a uniform approach. However, even focusing the comparison on a subset of 10 studies with parcellation and analysis methods most similar to ours (i.e., whole-brain, ROI-to-ROI) yields a poor average ICC (0.28) (Faria et al., 2012; Fiecas et al., 2013; Noble et al., 2017; Noble et al., 2017; Pannunzi et al., 2017; Parkes et al., 2018; Shehzad et al., 2009; J. Wang et al., 2017; J.-H. Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2017). Thus, the differences between our results and Noble et al.‘s may also be attributable to variability in other design elements, such as acquisition parameters, scan duration (or data quantity), time between scans, and preprocessing procedures, which are likely correlated with reliability (Noble et al., 2019).

While our results suggest a tendency for fair reliability in PWA, it is important to recognize that even under the optimal circumstances, 45 % of edges had poor reliability. Thus, researchers measuring edge-level RSFC in PWA over repeated scans must recognize the real possibility that a change in a given edge may well be due to normal variability in functional connectivity rather than a meaningful change that can be attributed to intervention or recovery, and thus, strong inferences should be made with caution. Likewise, edge-level inferences from cross-sectional studies should also be considered with some skepticism, as relationships between, say, a behavioral measure and connectivity in a given edge may be unreliable or invalid if the underlying connectivity measure is, itself, unreliable. To be clear, this does not mean that conclusions from prior RSFC studies of PWA are necessarily invalid; in fact, relatively few aphasia studies have explicitly focused on ROI-to-ROI functional connectivity in a whole-brain network. More often, analyses have focused on subnetworks or key regions defined and selected based on the literature or via methods like independent components analysis (ICA) or measures of regional spontaneous brain activity (Balaev et al., 2016; Billot et al., 2022; Bitan et al., 2018; Falconer et al., 2024; Ramage et al., 2020; Sandberg, 2017; Stockbridge et al., 2023; Xie et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2014). Others have used graph theoretic techniques to distill brain-wide connectivity into summary measures that characterize the organization or overall connectivity of the network (e.g., Duncan and Small, 2016; Baliki et al., 2018; Riccardi et al., 2023). However, the present finding of variable and generally moderate reliability is relevant to the broader literature because ROI-to-ROI connectivity matrices often serve as the basis for graph theory and related network-level analyses. Further, the approach used here is conceptually similar to several of the other techniques noted above. Thus, at the very least, investigations of the reliability of other RSFC methods (e.g., voxel-to-voxel and seed-to-voxel connectivity, the use of ICA or amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations to define subnetworks or ROIs, graph theoretical metrics, etc.) are warranted.

An additional finding that bears mentioning is that the distribution of ICCs was negatively skewed (this was true for the full 12-min dataset, as well the shorter, incremental datasets). As such, the median is preferable to the mean as a descriptive statistic of the central tendency of RSFC reliability since it is less sensitive to extreme values across the distribution. And when we converted negative ICCs to 0, the mean increased by a few hundredths of a point (0.02–0.06, depending on scan duration), which in one case (11 min) was enough to move it across the threshold from poor to fair reliability. In contrast, the median was unaffected by the handling of negative ICCs. In sum, the median is a more stable, less sensitive measure than the mean and should be reported in future reliability papers to allow for informative comparisons between studies.

4.2. Reliability of functional connectivity in aphasia is associated with several variables

4.2.1. Scan duration/data quantity

An important result of this study is that edge-level RSFC in PWA was positively associated with the duration of imaging sessions used in the analysis. Scan duration is integrally correlated with the volume of data collected/analyzed, and studies in non-clinical populations have shown that longer durations and more data per subject (obtained, for example, via faster sampling rates) are each associated with greater reliability (see Noble et al., 2019, for a discussion). In the present study, within-session data were obtained via two back-to-back 6-min resting-state scans. Given the brevity of the break between scans (typically ∼30 s or less), we have treated the data as though they were obtained from a series of increasingly longer scans (hence our use of the term “scan duration” throughout this manuscript). However, since study staff checked in with participants during the break, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that our results are more indicative of the relationship between the amount of data and reliability than scan duration and reliability.

Regardless of one's interpretation of the above, we found that reliability increased incrementally with scan duration (i.e., as more data were introduced to the analysis), though the regression model and visual inspection of median ICCs indicate that gains in reliability started to taper off at 11–12 min. Since we had a maximum of 12 min of data per session, we do not know if reliability truly plateaued at 12 min or if it could be meaningfully improved at even longer durations, nor are we positioned to identify an optimal scan duration (or data volume) for RSFC in PWA. Nevertheless, our data clearly suggest that “more is better” up to at least 12 min/720 volumes. Some have advocated for collecting a minimum of 20 min based on studies involving stroke survivors and controls (Siegel et al., 2017), but many previous RSFC studies in PWA have used shorter scan durations (<10 min). Our results suggest that the community might consider increasing durations to at least 12 or more minutes (likely split between multiple runs to provide participants with a break) moving forward; that is likely the minimum benchmark we will employ in our own research in the future.

4.2.2. Edge strength and inter-node distance

Edge-level RSFC reliability in PWA was positively associated with connectivity strength to a point, but the relationship leveled off when strength reached about 0.4 and eventually trended back down. To some extent, it may be that model estimates of the relationship in stronger edges were less accurate than for low- and moderate-strength edges because there were far fewer high-strength edges in the dataset. At the same time, the results point to a potentially complex relationship between strength and reliability, such that it would be inaccurate to assume that all weak edges are unreliable, and all strong edges are very reliable. This bears mentioning because brain network analysis strategies often involve excluding weak connections out of concern that they may be spurious and retaining stronger (and presumably more reliable and meaningful) connections. Our results broadly support this approach: thresholding based on edge strength should result in the retention of mostly reliable edges, though a substantial proportion of highly reliable (but weak) connections would be excluded. Ultimately, further research focused specifically on the reliability of network-level properties derived from various thresholding techniques is needed to determine if there is an optimal network characterization strategy for use in PWA.

Unlike edge strength, the relationship between reliability and inter-node distance was more straightforward: shorter edges associated with two nearby ROIs tended to be slightly more reliable than longer edges. This result likely reflects that functional connectivity, to some extent, indirectly reflects anatomical connectivity, with previous studies having shown that functional connectivity is stronger between closer, more directly connected regions than more distant and/or disconnected regions (Honey et al., 2009; Salvador et al., 2005). Our results indicate that, at least in PWA, edges between anatomically proximal ROIs are also more reliable than their more distant counterparts, likely owing in part to the proximity between their incident ROIs.

4.3. Cognitive and language subnetworks are more reliable than the whole-brain network

Fourteen of 15 functionally defined subnetworks had higher median ICCs than the full network, and bootstrap confidence intervals revealed that 11 subnetworks were significantly more reliable than the full network. Additionally, 12 subnetworks were more reliable than would be expected by chance (and a 13th, the memory retrieval subnetwork, was trending), relative to random networks matched for size, edge strength, and inter-node distance, suggesting these are robust and reliable findings. In their meta-analysis and review, Noble et al. (2019) found that fronto-parietal and default mode networks (FPN and DMN, respectively) were most frequently cited as having good reliability. In our sample of PWA, the FPN had the third highest median reliability among subnetworks. The DMN was less reliable than other subnetworks, but still had a statistically robust median ICC of 0.578. Also consistent with the non-clinical literature, the cerebellar and subcortical subnetworks were the least reliable subnetworks in our sample. Overall, this analysis provides evidence that the same subnetworks whose presence is well-established in healthy controls are reliably present in PWA, even in the context of damage after stroke and even when removing numerous ROIs due to damage as in the conservative analysis described in the supplementary materials.

With respect to the language subnetworks, both fell in the fair range for reliability, but the language network based on Fedorenko's language parcels was somewhat more reliable than Roger et al.‘s LANG network. A potential explanation for this difference is that LANG is a more generalized language network comprising the strongest connections among regions that are widely distributed throughout the brain and believed to support a range of cognitive-linguistic functions (monitoring, decoding, semantics, etc.). In contrast, our second language network consists of regions that intersect with Fedorenko's more circumscribed, classically perisylvian-oriented language parcels. Each of these networks may be suitable for future investigations of language processing and recovery in PWA, but our results indicate that edges in the Fedorenko-based network are the more reliable of the two. Notably, the reliability of both language subnetworks indicates that the language system (more generally) is relatively stable even after damage, given that all participants in this study had aphasia due to left-hemisphere stroke.

More generally, our results suggest that edges in established subnetworks are more stable than those chosen randomly across the whole-brain network. Therefore, future RSFC studies in PWA may be able to mitigate risks to validity by investigating a priori-selected cognitive and/or language subnetworks rather than making edge-level inferences based on a whole-brain analysis.

4.4. Reliability is fair within and between both hemispheres

Perhaps unsurprisingly, edges in the intact right hemisphere were more reliable than those in the damaged left hemisphere, as well as those spanning the hemispheres. Despite the statistical significance of this finding, the median reliability of edges on the ipsilesional side and those involving ipsilesional regions was fair, suggesting that it may be reasonable to include edges on the damaged side in resting-state studies involving people with aphasia.

4.5. Limitations

The sample size in the present study was fairly small, so it is likely that some ICC estimates are relatively imprecise, especially those in the liberal analysis that may have included as few as seven participants. This concern is somewhat mitigated by the similarity of the results from the conservative analysis, in which the full sample contributed to all of the ICC calculations. Still, studies of edge-level RSFC reliability in larger samples of PWA are needed to validate our results.

Additionally, our results and conclusions are limited to the specific methods we used. We are unable to comment on how different brain atlases or network construction methods, functional connectivity metrics (e.g., partial correlations) and methods (e.g., seed-to-voxel, voxel-to-voxel), or preprocessing decisions impact RSFC reliability in PWA. It is likely that each of these variables would impact reliability measures, but more research is needed to determine how.

Finally, because this study used a convenience sample from an aphasia treatment trial, it did not include healthy control participants. While we tentatively considered our results relative to the literature on healthy controls in section 4.1, we cannot draw strong conclusions about how the reliability of RSFC in PWA compares to that of similar adults who have never had a stroke, especially for the subnetworks that were uniquely examined in the present study (e.g., the language subnetworks and connections within and between the hemispheres). Subsequent research involving PWA and demographically matched controls subjected to the same imaging and analysis protocols is needed to determine conclusively if RSFC in PWA is consistent with or deviates from that of people who do not have aphasia.

4.6. Conclusions

This study shows that the reliability of RSFC in individuals with post-stroke aphasia is acceptable, but well short of excellent, at the level of individual edges. It is improved by longer scan times, stronger functional connectivity (to an extent), and limiting analyses to known cognitive and language subnetworks.

There are several implications of the results discussed above, especially with respect to future RSFC studies involving PWA. First, with respect to reliability, longer scans (i.e., more data) are better. We did not identify an optimal scan duration or data quantity, but a minimum of 12 min appears advisable. Second, analyses based on established subnetworks are likely to be more reliable—and arguably more valid—than those based on a whole-brain network, at least at the level of individual edges. If whole-brain edgewise analyses are conducted, skepticism is warranted regarding inferences based on just one or a few edges. Third, researchers who use RSFC to monitor treatment effects would be well-advised to use strategies to mitigate the threat of mistaking normal fluctuations/instability in RSFC for meaningful, treatment-related changes. For example, they could demonstrate that changes from pre-to post-treatment exceed those that occur between multiple pre-treatment scans or that changes in treated patients exceed those in a group of untreated patients scanned with the same frequency as the treated group. Finally, additional research is needed to investigate the reliability of other functional connectivity and data processing methods besides the ones used in this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jeffrey P. Johnson: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Michael Walsh Dickey: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Jason W. Bohland: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. William D. Hula: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Funding