Abstract

Tolerance to replication-blocking DNA lesions is achieved by means of ubiquitylation of PCNA, the processivity clamp for replicative DNA polymerases, by components of the RAD6 pathway. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae the ubiquitin ligase (E3) responsible for polyubiquitylation of the clamp is the RING finger protein Rad5p. Interestingly, the RING finger, responsible for the protein's E3 activity, is embedded in a conserved DNA-dependent ATPase domain common to helicases and chromatin remodeling factors of the SWI/SNF family. Here, we demonstrate that the Rad5p ATPase domain provides the basis for a function of the protein in DNA double-strand break repair via a RAD52- and Ku-independent pathway mediated by the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 protein complex. This activity is distinct and separable from the contribution of the RING domain to ubiquitin conjugation to PCNA. Moreover, we show that the Rad5 protein physically associates with the single-stranded DNA regions at a processed double-strand break in vivo. Our observations suggest that Rad5p is a multifunctional protein that—by means of independent enzymatic activities inherent in its RING and ATPase domains—plays a modulating role in the coordination of repair events and replication fork progression in response to various different types of DNA lesions.

INTRODUCTION

DNA as a chemically reactive molecule is subject to a variety of insults from exogenous as well as endogenous sources that require distinct strategies for their removal. One of the most dangerous DNA lesions is a double-strand break (DSB), which can be caused by ionizing radiation and also results from replication over single-strand breaks or from enzymatic activities during developmental processes such as meiosis, yeast mating type switching or the generation of diversity within the immune system. When left unrepaired, a DSB can cause permanent cell cycle arrest and ultimately cell death. Accordingly, several distinct mechanisms exist for its repair (1,2). On the one hand, a DSB can be repaired by direct ligation in a process termed non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), usually but not exclusively mediated by the Ku heterodimer, which binds to double-stranded DNA ends and facilitates ligation (3). Unless the termini are compatible and cohesive, NHEJ generally results in sequence deletions of varying sizes. On the other hand, accurate restoration of the broken ends can be achieved by means of homologous recombination (HR), provided that homologous sequences are present elsewhere in the genome (4). Finally, in a process called single-stranded annealing (SSA), internal complementary sequences on both sides of the break can anneal with each other in order to be ligated, resulting in the loss of intervening sequence (2). In yeast HR and SSA depend on the recombination factor Rad52p, which initiates the search for homology. Implicated in both HR and NHEJ is the multifunctional protein complex of Mre11p, Rad50p and Xrs2p (the MRX complex), which comprises both exo- and endonucleolytic as well as strand annealing activities (5–7).

In addition to those systems that remove lesions cells also possess mechanisms of damage bypass that enable them to complete DNA replication in the presence of unrepaired damage. The enzymatic system that controls damage bypass, the RAD6 pathway (8–10), comprises members of the ubiquitin conjugation system that cooperate in the modification of the eukaryotic processivity clamp for DNA polymerases, PCNA (encoded in yeast by POL30). Upon treatment of cells with DNA-damaging agents, PCNA is monoubiquitylated at a single lysine residue by a complex of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) Rad6p and the RING finger ubiquitin protein ligase (E3) Rad18p (11), resulting in the activation of damage-tolerant polymerases for translesion synthesis in yeast and mammalian cells (12–14). Monoubiquitylated yeast PCNA can be polyubiquitylated by the action of a second E2–E3 pair, the heterodimeric E2 Ubc13p-Mms2p in complex with the RING finger E3 Rad5p (11). By an unknown mechanism, this form of PCNA activates an error-free damage avoidance pathway that is believed to involve a switching of the replication machinery to the undamaged sister chromatid.

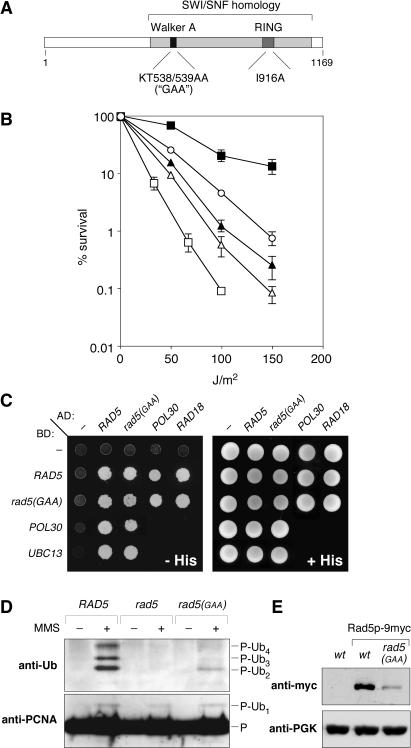

Several lines of evidence suggest a function of yeast Rad5p beyond its activity in damage tolerance. Deletion of RAD5 results in considerably higher sensitivities toward various types of DNA damage than deletion of UBC13 or MMS2 (15). Furthermore, rad5 mutants display several other phenotypes that are not shared by mutants of its cognate E2: they are highly sensitive to ionizing radiation (16), display elevated rates of spontaneous mitotic recombination and gross chromosomal rearrangements (17,18) but increased stability of simple repetitive sequences (19) and elevated levels of end-joining activity in a plasmid gap repair assay designed to distinguish between HR and NHEJ (20). Based on these observations it has been suggested that Rad5p contributes to DSB repair, possibly as a positive regulator of HR (20,21). The structure of the protein is highly unusual for an E3 enzyme: its RING domain, responsible for E3 activity and E2 interaction (15,22), is embedded in a conserved helicase-like domain of the SWI/SNF family, members of which include DNA and RNA helicases as well as chromatin remodeling factors (19,23) (Figure 1A). Although there is currently no evidence for a helicase activity of the purified protein, a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-stimulated ATPase activity of the purified protein was demonstrated in vitro (24).

Figure 1.

Characterization of a mutant in the RAD5 ATP-binding domain. (A) Domain structure of Rad5p. Conserved sequence motifs are indicated above the protein, sites of mutations relevant for this study below. (B) A mutant in the RAD5 ATP-binding motif, rad5(GAA), displays partial UV sensitivity that is additive to that of the E2 mutant ubc13. Survival after UV irradiation (254 nm) is plotted on a logarithmic scale. Error bars (standard deviations from four independent experiments) are indicated where they exceed the size of the plot symbols. Symbols: solid squares, wt; open squares, rad5; open circles, rad5(GAA); closed triangles, ubc13; open triangles, ubc13 rad5(GAA). (C) Mutation of the ATP-binding motif of Rad5p abolishes none of the associations relevant for ubiquitin conjugation. Interactions of the wild-type and the mutant protein with itself, Rad18p, Ubc13p and PCNA (encoded by POL30) were analyzed in the two-hybrid system. Positive interactions were detected by growth on histidine-free medium (−His). Fusions to the GAL4 activation and DNA-binding domains in the two-hybrid constructs are designated AD and BD, respectively. (D) The ATP-binding motif of Rad5p is not required for polyubiquitylation of PCNA. His-tagged PCNA (P) and its modified forms were detected by western blot after Ni-NTA pull-downs under denaturing conditions with or without treatment with 0.02% MMS in the indicated strains. (E) Western blot analysis of strains bearing chromosomally 9myc-tagged versions of the RAD5 ORF indicates reduced protein levels in the rad5(GAA) mutant compared to wt RAD5. Blots were re-probed with antibodies to phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) as a loading control.

Here we show that RAD5 contributes to DSB repair not by means of HR, but in a RAD52- and Ku-independent pathway mediated by the MRX complex. This function of RAD5 does not involve the ubiquitylation of PCNA and appears to be independent of the protein's ubiquitin ligase activity. In contrast, an intact ATP-binding domain of Rad5p is necessary for its action in DSB repair. We found that Rad5p physically associates with the ssDNA regions generated by the processing of a DSB in vivo. We thus propose that Rad5p acts as a modulator of DNA repair events that influences the coordination of strategies used by the cell in response to different types of lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of yeast strains and plasmids

Standard protocols were followed for the cultivation of yeast. A table of strains used for this study and details about their construction are available as Supplementary Data. Integrative plasmids bearing wild-type or mutant versions of RAD5 (YIp211-PRAD5-RAD5) have been described previously (22). The plasmid bearing the rad5(GAA) mutant was constructed analogously. Mutation of amino acids K538 and T539 to alanine was accomplished by PCR. Two-hybrid vectors bearing the mutant RAD5 gene or POL30 were constructed by inserting the respective open reading frames (ORFs) into pGAD424 and pGBT9 (Clontech). All other two-hybrid constructs have been described previously (15). Plasmid YCp111-LacZ::HIS3 is based on the centromeric shuttle vector YCplac111 into which the MET3 promoter, the LacZ ORF and a pGBT9-derived transcriptional terminator sequence was inserted. The HIS3 marker was inserted into the unique SacI site of the LacZ gene. Details about the plasmids and primers used are available upon request.

Measurements of sensitivities toward UV and gamma irradiation

Sensitivities toward UV irradiation were determined as described previously (15). For the determination of gamma sensitivities exponential yeast cultures were diluted and plated onto YPD at a density of approximately 200 cells/plate or at higher density, depending on the sensitivity of the strain. The plates were irradiated with a 137Cs source at a dose rate of 0.8 Gy/min. The plates were incubated at 28 or 30°C for 3 days, and the number of survivors was determined by colony counting. Averages and standard deviations were calculated from four independent experiments.

Detection of PCNA modifications

Ubiquitylated PCNA was detected in strains in which the endogenous POL30 gene was replaced by a His-tagged version. Extracts were prepared and Ni-NTA affinity pull-downs were performed under denaturing conditions as described previously (12). For the detection of PCNA modifications in response to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) exponential cultures were treated for 90 min with 0.02% MMS, and total extracts were prepared by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. Western blots were developed with an affinity-purified polyclonal anti-PCNA antibody. For the analysis of PCNA after introduction of EcoRI-mediated DSBs, a plasmid harboring the endonuclease under the control of the GAL1 promoter, YCpGal-RIb, was introduced (25), and the expression was induced by shifting the cells from selective glycerol to galactose medium for 3 h before extract preparation. Shifting to glucose medium served as a negative control. Flow cytometry was used to confirm the growth arrest induced by the nuclease.

Two-hybrid assays

Protein–protein interactions were analyzed in the two-hybrid system using the reporter strain PJ69-4A as determined previously (15). Growth on histidine-free medium was used as an indicator for positive interactions.

Plasmid repair assays

Plasmid YCp111-LacZ::HIS3 was digested with SacI. A mock digestion reaction was set up in parallel without adding enzyme. Both mixtures were used to transform yeast cells (2.5 µg DNA per 108 cells), and several dilutions of the transformation mixtures were plated onto leucine-free medium and incubated at 28°C for 3–4 days in order to determine transformation efficiencies of linear and circular vector. Plates with a convenient number of colonies were examined for the expression of β-galactosidase by an X-gal agarose overlay assay. White colonies were picked through the layer of agar and streaked onto histidine-free selective plates, and the number of HIS-prototrophic colonies was subtracted from the count of total and white colonies. This step proved necessary in those strains with very low overall repair efficiencies. Events of double transformations of isolated HIS3 fragment and digested vector were too rare to affect the results (S. Chen and H. D. Ulrich, unpublished data). Transformation efficiencies were calculated as the ratio of colonies arising from SacI-digested versus circular plasmid, and the percentage of incorrect repair products was determined as the ratio of white to the total number of LEU+ colonies after transformation with linearized plasmid. The assay was performed at least three times for each strain for the determination of averages and standard deviations, and for all strains the analysis was based on more than 1000 colonies in total derived from transformation with linear DNA.

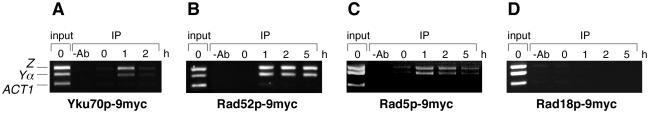

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and multiplex PCR

In a strain background harboring a galactose-inducible HO gene, proteins of interest were modified by a C-terminal 9myc-epitope introduced as a sequence tag within the original genomic context and were found to be active in vivo. Cells were grown in YP-glycerol medium at 28 or 30°C to an OD600 of ∼1.7, and galactose was added to a final concentration of 2% (w/v). At various times after induction, samples of ∼2 × 109 cells were collected and subjected to ChIP. The method for formaldehyde-mediated crosslinking and islolation of DNA was adapted from published protocols (26). The detailed procedure is available as Supplementary Data. Multiplex PCR was performed with samples of input and precipitated DNA, using primer pairs that amplified regions of 298 and 263 bp on either side of the break (Z region, 5′-TTATAGAGTGTGGTCGTGGC-3′/5′-CCCGTATAGCCAATTCGTTC-3′ at 0.5 µM; and Yα region, 5′-TGAGCATGTGAGGCCAAGCTG-3′/5′-TCAGCGAGCAGAGAAGACAA-3′ at 0.26 µM) and a primer pair that amplified 218 bp of the ACT1 gene (5′-TGGATTCCGGTGATGGTGTT-3′/5′-TTGTTCGAAGTCCAAGGCGA-3′ at 0.26 µM). Reactions were run for 30 cycles with an annealing temperature of 52°C, and products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

Polyubiquitylation of PCNA does not require the ATPase activity of Rad5p

We wished to determine whether the putative function of Rad5p in DSB repair was genetically separable from the protein's involvement in ubiquitin conjugation. In order to assess the role of its ATPase activity in this process we constructed a mutant in which the conserved ‘GKT’ sequence (amino acids 537–539) within the ATP-binding motif, the Walker type A box, was changed to ‘GAA’ (Figure 1A). Mutation of the conserved lysine within this motif had previously been shown to abolish all ATP-binding and hydrolytic activity in related ATPases (27–29). The resulting mutant, rad5(GAA), exhibited a mild UV sensitivity intermediate between that of the wt and a rad5 deletion (Figure 1B). Importantly, its sensitivity was additive to that of a ubc13 mutant, suggesting a defect in a repair pathway distinct from the PCNA-mediated error-free damage tolerance system.

As shown in Figure 1C, two-hybrid analysis revealed no defect in the association of the mutant protein with its interaction partners relevant for PCNA modification, Rad18p, Ubc13p, Rad5p itself and PCNA (11,15), suggesting that the overall structure of the protein is not grossly disturbed by mutation of its ATP-binding motif. We, therefore, directly examined whether DNA damage-induced ubiquitylation of PCNA occurred normally in the rad5(GAA) mutant. Upon treatment with MMS, PCNA polyubiquitylation was indeed observable in rad5(GAA) cells (Figure 1D). The lower levels of modified PCNA in the ATPase mutant may be due to a reduced in vivo concentration of the mutated protein (Figure 1E). This effect may also account for part of the UV sensitivity of the rad5(GAA) mutant; however, the additive relationship between rad5(GAA) and ubc13 argues that the observed phenotype is not exclusively due to reduced expression levels. In addition, the purified ATPase mutant protein was equally potent in stimulating Ubc13p-dependent ubiquitin chain synthesis as wild-type Rad5p (J. Parker and H. D. Ulrich, unpublished data), indicating that an intact ATP-binding motif is indeed dispensable for ubiquitin ligase activity of Rad5p.

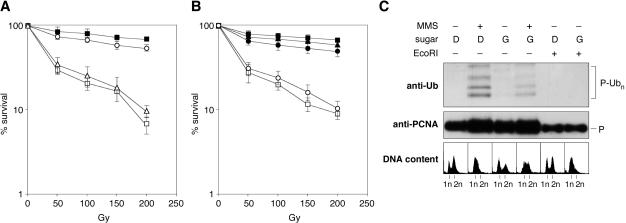

The Rad5p ATP-binding domain, but not the RING finger, is required for DSB repair

Whereas the rad5(GAA) mutant was only partially sensitive to UV irradiation, its sensitivity toward ionizing radiation was comparable to that of a rad5 deletion (Figure 2A and B). In contrast, a previously characterized mutation in the RING domain, rad5(I916A), which abolishes E2 interaction and causes a UV sensitivity comparable and epistatic to ubc13 (22), did not render the cells sensitive toward gamma irradiation (Figure 2A). This indicates that an intact RING finger, the prerequisite for E3 activity, is not required for Rad5p function in DSB repair. Similarly, deletion of UBC13 or mutation of the ubiquitylation site of PCNA, K164, did not result in significant sensitivity toward gamma irradiation, suggesting that ubiquitylation of PCNA is not important for efficient DSB repair (Figure 2B). Conversely, introduction of DSBs into the yeast genome by means of overexpression of the restriction endonuclease EcoRI did not result in detectable PCNA ubiquitylation, although it induced a complete growth arrest (Figure 2C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that RING-dependent polyubiquitylation of PCNA in cooperation with Ubc13p on the one hand and the ATP-dependent contribution to DSB repair on the other hand are distinct and separable functions of Rad5p.

Figure 2.

Consequences of DSBs for aspects of Rad5p function. (A) The rad5(GAA) mutation, but not the rad5(I916A) RING finger mutation, confers sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Survival was determined after gamma irradiation of the indicated strains in four independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Symbols: closed squares, wt; open squares, rad5; open circles, rad5(I916A); open triangles, rad5(GAA). (B) Defects in PCNA ubiquitylation do not lead to gamma sensitivity. Assays were performed as in (A), using a different strain background (see Supplementary methods and table). Symbols: closed squares, wt; closed triangles, ubc13; closed circles, pol30(K164R); open squares, rad5; open circles, rad5(GAA). (C) Induction of a DSB in the yeast genome by means of the endonuclease EcoRI does not result in ubiquitylation of PCNA. Yeast cells harboring His-tagged yeast PCNA (P) were grown in glycerol medium, transferred to either glucose (D) or galactose (G) medium and treated with 0.02% MMS as indicated. Where indicated, cells carried a plasmid encoding a galactose-inducible EcoRI endonuclease gene (YCpGal-RIb). Isolation and detection of His-tagged PCNA and its modified forms was performed as shown in Figure 1D. DNA contents were analyzed by flow cytometry to confirm cell cycle arrest upon treatment with MMS or induction of the nuclease.

RAD5 contributes to a DSB repair pathway dependent on the MRX complex

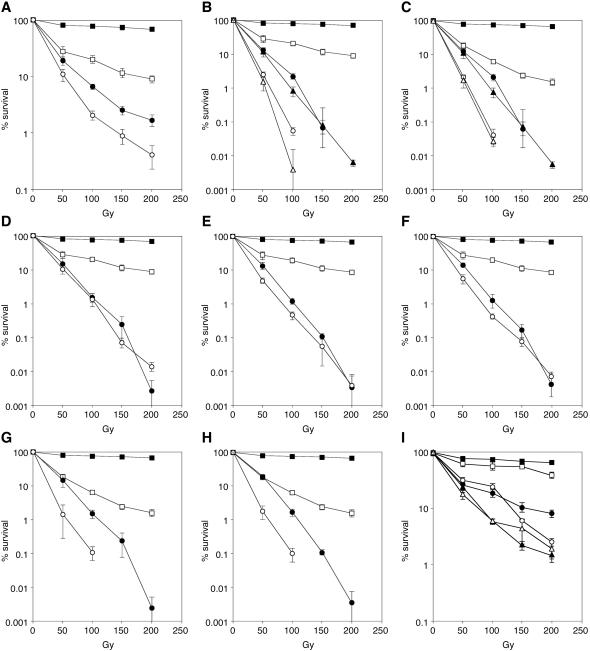

Whereas in the context of DNA damage tolerance the activity of Rad5p is strictly dependent on the presence of the ubiquitin ligase Rad18p, which catalyzes the attachment of the first ubiquitin moiety to PCNA, the two proteins appear to fulfill separate roles in DSB repair, judging by the additive effects of rad5 and rad18 mutants on gamma sensitivity shown in Figure 3A and observed previously (16). Based on the phenotype of rad5 mutants, it had been suggested that Rad5p may act as a positive regulator of recombination (20,21). In this case, an epistatic relationship would be expected between rad5 and mutants in recombination genes such as rad52 and rad51 with respect to their sensitivity toward ionizing radiation. However, we found instead that the effect of rad5 on gamma sensitivity was additive to that of both rad51 and rad52, suggesting that RAD5 contributes to a pathway of DSB repair distinct from RAD52-dependent HR (Figure 3B). A similar relationship was observed between HR mutants and rad18 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Genetic analysis of the gamma sensitivities of rad5 and rad18 mutants. Survival after exposure to ionizing radiation was determined in the indicated strains as in Figure 2A. (A) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad5; closed circles, rad18; open circles, rad5 rad18. (B) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad5; closed circles, rad51; open circles, rad5 rad51; closed triangles, rad52; open triangles, rad5 rad52. (C) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad18; closed circles, rad51; open circles, rad18 rad51; closed triangles, rad52; open triangles, rad18 rad52. (D) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad5; closed circles, mre11; open circles, rad5 mre11. (E) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad5; closed circles, rad50; open circles, rad5 rad50. (F) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad5; closed circles, xrs2; open circles, rad5 xrs2. (G) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad18; closed circles, mre11; open circles, rad18 mre11. (H) Closed squares, wt; open squares, rad18; closed circles, rad50; open circles, rad18 rad50. (I) Closed squares, wt; open squares, yku70; closed circles, rad5; open circles, rad5 yku70; closed triangles, rad18; open triangles, rad18 yku70.

We next examined the effect of the repair genes MRE11, RAD50 and XRS2, which appear to be involved in both HR and NHEJ (5–7). Deletion of RAD5 in an mre11 mutant did not result in an increased gamma sensitivity compared with the mre11 single mutant, indicating that the function of RAD5 in DSB repair depends on the presence of MRE11 (Figure 3D). Consistent with the action of Mre11p in a complex with Rad50p and Xrs2p, the same epistatic relationship was found between rad5 and rad50 or xrs2, respectively (Figure 3E and F). In contrast, a rad18 deletion had an additive effect on mutants of both mre11 and rad50 (Figure 3G and H), again indicating that RAD18 acts independently of RAD5 in DSB repair.

Finally, an involvement of RAD5 in Ku-dependent NHEJ was deemed unlikely because deletion of YKU70 enhanced the radiation sensitivity of a rad5 mutant (Figure 3I). The same effect had previously been observed for rad52 (30). Again, a RAD18-independent function is suggested by these observations, as deletion of YKU70 did not have an obvious effect on a rad18 mutant (Figure 3I). Thus, our data indicate that RAD5 cooperates with MRE11, RAD50 and XRS2 in an aspect of their function that is independent of RAD52-dependent HR and Ku-mediated NHEJ.

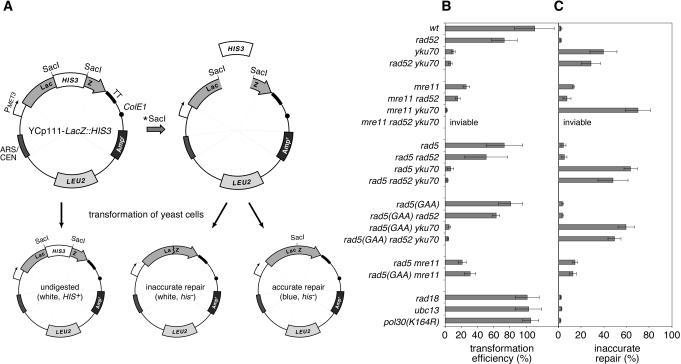

RAD5 contributes to the ligation of compatible cohesive DNA termini in vivo

As the MRX complex is implicated not only in Ku-dependent NHEJ, but also in a Ku-independent pathway, we used a plasmid repair assay to examine a possible contribution of RAD5 to NHEJ. Although Ku-independent activity of MRE11 as well as RAD5-dependent effects on HR and NHEJ were previously demonstrated with non-compatible ends (20,31), we chose an assay based on the recircularization of a linearized plasmid with compatible, cohesive 3′ overhangs without homology to genomic sequences (Figure 4A), because similar systems have been well characterized with respect to the effects of both RAD52 and Ku (32), which allows the establishment of their genetic relationships with RAD5 by epistasis analysis. In this system, comparison between transformation frequencies of linear versus uncleaved plasmid DNA allows an estimation of relative repair efficiencies (Figure 4B), and the accuracy of the process can be determined by a colony color assay based on the expression of active β-galactosidase only upon accurate rejoining of the termini (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Contribution of DNA repair factors to ligation of compatible cohesive plasmid termini. (A) The shuttle vector YCp111-lacZ::HIS3 harbors the β-galactosidase ORF, interrupted by the HIS3 marker, under the control of the yeast MET3 promoter and a transcriptional terminator (TT). Digestion with SacI removes the HIS3 marker, and transformation of the linear plasmid into yeast cells followed by selection on leucine-free medium allows the quantification of repair events. X-gal staining gives rise to blue colonies only when the HIS3 marker has been removed and the SacI sites have been joined accurately. White colonies arising from transformation with incompletely digested vector can be distinguished from those arising from inaccurate repair by selection on histidine-free medium. (B) Transformation efficiencies were calculated as the ratio of colonies arising from SacI-digested versus circular plasmid. Numbers greater than 100% result from the higher uptake efficiency of linear versus circular DNA. Averages and standard deviations were calculated from at least three independent sets of transformations. (C) The percentage of incorrect repair products after transformation with linearized plasmid was determined as the ratio of white to the total number of LEU+ colonies.

Deletion of RAD52 and YKU70 reproduced the expected defects in ligation efficiency and accuracy that had been observed previously (32). We also found a marked reduction in transformation efficiency and a significant increase in the percentage of incorrectly joined plasmids in an mre11 mutant, indicating that MRE11 contributes to accurate joining of compatible ends. Moreover, the deletion of MRE11 in a rad52 or yku70 background strongly exacerbated the effects of the single mutants, suggesting that MRE11 indeed functions at least in part independently of RAD52 and Ku. In fact, the triple mutant mre11 rad52 yku70 proved inviable, indicating an essential function to which all three genes contribute independently.

RAD5 was previously found to have no significant effect on ligation of compatible ends (21,33), and although the reduction in transformation efficiency that we observed in a rad5 mutant was indeed small (comparable to rad52), the proportion of incorrect ligation products was reproducibly enhanced in our system. Specifically, in yku70 and rad52 yku70 mutants deletion of RAD5 significantly reduced ligation efficiency and accuracy in a pattern similar to the mre11 mutant, suggesting that RAD5 contributes to Ku-independent end-joining. Again, the rad5(GAA) mutant behaved very similar to the rad5 deletion, implying that the function of the protein in this pathway is mediated by its ATPase activity. Moreover, rad5 or rad5(GAA) did not significantly affect the phenotype of an mre11 mutant, indicating that the genes cooperate in a common pathway. A rad18 deletion by itself did not show measurable defects in end-joining, and its effect on other end-joining mutants did not resemble that of rad5 mutants (data not shown). Finally, ubc13 and pol30(K164R) showed no defects in the end-joining assay, emphasizing once more that ubiquitination of PCNA plays no role in this process.

Rad5p associates with the ssDNA regions adjacent to a DSB

In order to assess whether the effect of RAD5 on end-joining was due to an indirect influence on other repair factors or whether Rad5p was directly involved at the site of a break, we monitored the in vivo association of the protein with the regions adjacent to a DSB by means of ChIP (34) and multiplex PCR. Similar to previous set-ups (35,36) a galactose-inducible HO endonuclease was used to introduce a single, sequence-specific DSB into the MAT locus of a strain in which repair by HR is impossible. In this well-defined situation, long stretches of ssDNA with free 3′ termini accumulate adjacent to the DSB over a period of several hours (36,37). According to their respective preferences for double-stranded DNA termini or ssDNA, Ku and Rad52p were found to associate with the DSB region at different times (Figure 5A and B). Consistent with the ssDNA-binding activity described previously for Rad5p (24), the protein was detected adjacent to the DSB with a kinetics similar to that of Rad52p. In contrast, Rad18p, which had also been characterized as an ssDNA-binding protein (38), was not found enriched at the DSB under these conditions, suggesting that the presence of Rad5p may indeed reflect a physiological relevance rather than merely a non-specific affinity for ssDNA. Moreover, association of Rad5p with the break region was dependent on the presence of Mre11p, but not of Ku, in support of the genetic interactions established above (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Association of repair factors with regions adjacent to a DSB. (A–D) ChIP assays were used to visualize the binding of the indicated proteins in a time course of up to 5 h after HO-mediated introduction of a DSB into the MAT locus. After formaldehyde-mediated crosslinking, proteins of interest were precipitated by means of their C-terminal 9myc-epitope integrated into the genomic locus. After reversal of the crosslinks and isolation of the associated DNA, multiplex PCR was performed on samples prepared from total cell extracts (input) and from material precipitated with the myc-specific antibody (IP). Precipitations without antibody (−Ab) served as negative controls. Z and Yα represent regions on either side of the DSB; amplification of a region within the ACT1 gene was used as a control for DNA unrelated to the DSB.

DISCUSSION

Rad5p cooperates with the MRX complex in DSB repair

The phenotype of rad5 mutants had long suggested an involvement of the gene in DSB repair (16,17,20,21). We have now demonstrated that this function of RAD5 is independent of RAD52-mediated HR or Ku-mediated NHEJ, but instead depends on the presence of the MRX complex, whose role in DSB repair is mechanistically not fully understood, despite the manifold DNA-processing activities reported (5–7). Apart from its contributions to HR and Ku-mediated NHEJ, the MRX complex has been implicated in an end-joining pathway distinct from Ku-dependent ligation (21,31), and our observation that the activity of RAD5 in the repair of radiation damage depends on MRE11, RAD50 and XRS2, but is independent of RAD52, RAD51 and YKU70, provides further support for an independent role of the MRX complex. Similar genetic relationships are observed with respect to the rejoining of compatible cohesive ends, although the effects of RAD5 in this context are minor and best visible in the absence of the Ku-dependent end-joining pathway.

Although the association of Rad5p with the regions adjacent to a DSB suggests an involvement of the protein at the site of the lesion, its physiological role in repair remains to be determined. Interestingly, as the MRX complex plays a critical role in the prevention or repair of replication-associated DSBs even in the absence of exogenous damage (39,40), the MRX-dependent function of Rad5p might similarly be relevant during DNA replication. Considering the protein's role in DNA damage tolerance at replication forks, it is attractive to speculate that Rad5p might act not only toward the bypass of a replication-blocking DNA adduct, but also when a nick in the template strand threatens to cause a DSB. Rad5p might thus react to different types of lesions with distinct actions inherent in its domain structure: in cooperation with Rad18p it induces a template switch of the replication fork by polyubiquitylation of PCNA in the context of error-free damage avoidance, whereas in the presence of a DSB it might facilitate Mre11p-dependent rejoining, independent of Rad18p. Based on this scenario, the RAD6 pathway could be viewed as a general surveillance system for the replication fork that monitors its progression and initiates the appropriate reaction when an obstacle is encountered.

Ubiquitin ligase and ATPase activities are separable aspects of Rad5p function

Importantly, the function of RAD5 in DSB repair can be genetically separated from the protein's involvement in mediating DNA damage tolerance by ubiquitylation of PCNA. We have shown that neither mutation of the PCNA modification site nor deletion of Rad5p's cognate E2, Ubc13p, significantly reduce the performance of the cell in DSB repair. From the notions that no other yeast E2 is known to cooperate with Rad5p (H. D. Ulrich, unpublished data) and that a mutant in the E2-binding surface of the Rad5p RING finger, I916A, displays no hypersensitivity to gamma irradiation either, we conclude that the protein's activity in DSB repair is in fact not dependent on ubiquitin ligation at all. Instead, we were able to attribute the DSB repair function of Rad5p to the presence of a conserved nucleotide binding motif within the protein's helicase-like domain. Structural and biochemical studies of related DNA-dependent ATPases have revealed that movement of these proteins along the DNA is driven by the ATP-hydrolytic activity inherent in the helicase-like domain, whereas other domains serve more specialized purposes such as the unwinding of DNA or RNA or the removal of nucleosomes (41,42). By analogy, it is likely that the contribution of Rad5p to DSB repair requires its ATP-driven movement on ssDNA.

Significance of the Rad5p domain structure

Finally, our observations raise the intriguing question of why two apparently unrelated activities, ubiquitin-dependent damage tolerance and ATP-dependent DSB repair, are combined in a single polypeptide. Interestingly, RAD5 is the only member of the RAD6 pathway for which no convincing mammalian homolog has yet been identified, which might indicate that a separation of functions into E3 and ATPase may have occurred in higher organisms. However, numerous proteins with a similar arrangement of RING and SWI/SNF domains can be found both in yeast and in higher eukaryotes, usually involved in transcription or chromatin remodeling (43). Whereas the relevance of the RING domain is unresolved in various mammalian transcription factors, such as HIP116/Zbu1, RUSH-1α and the matrix-associated actin-dependent regulators of chromatin (SMARCA) proteins (43), a function in ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis has been suggested in the case of the nucleotide excision repair factor Rad16p from yeast, where mutation of the RING domain resulted in a stabilization of the damage recognition protein Rad4p (44). Again, the significance of the SWI/SNF domain is not fully understood, but a possible function could be the generation of superhelical torsion to facilitate extrusion of the excised oligonucleotide during repair (45). In summary, although the mechanistic details of their function remain obscure for most of the RING finger ATPases, their peculiar domain arrangement suggests that a combination of E3 and DNA translocation activities might be a widely used link between the ubiquitin system and chromatin metabolism.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jim Haber for the strain JKM179, Jasper Rine for plasmid YCpGal-RIb and Regine Kahmann for generous support. Marie Anders and Margret Ludwig are acknowledged for technical assistance, Joanne Parker for sharing unpublished results, and Xiaohui Bi for help with initial experiments. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK and by grants from the BioFuture Programme of the German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the EMBO Young Investigator Programme. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Cancer Research, UK.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aylon Y., Kupiec M. DSB repair: the yeast paradigm. DNA Repair. 2004;3:797–815. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haber J.E. Partners and pathways: repairing a double-strand break. Trends Genet. 2000;16:259–264. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downs J.A., Jackson S.P. A means to a DNA end: the many roles of Ku. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:367–378. doi: 10.1038/nrm1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haber J.E. DNA recombination: the replication connection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Amours D., Jackson S.P. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of DNA repair and checkpoint signalling. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopfner K.P., Putnam C.D., Tainer J.A. DNA double-strand break repair from head to tail. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krogh B.O., Symington L.S. Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:233–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulrich H.D. Degradation or maintenance: actions of the ubiquitin system on eukaryotic chromatin. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:1–10. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.1.1-10.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence C. The RAD6 DNA repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: what does it do, and how does it do it? Bioessays. 1994;16:253–258. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broomfield S., Hryciw T., Xiao W. DNA postreplication repair and mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 2001;486:167–184. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoege C., Pfander B., Moldovan G.L., Pyrowolakis G., Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stelter P., Ulrich H.D. Control of spontaneous and damage-induced mutagenesis by SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation. Nature. 2003;425:188–191. doi: 10.1038/nature01965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kannouche P.L., Wing J., Lehmann A.R. Interaction of human DNA polymerase η with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe K., Tateishi S., Kawasuji M., Tsurimoto T., Inoue H., Yamaizumi M. Rad18 guides polη to replication stalling sites through physical interaction and PCNA monoubiquitination. EMBO J. 2004;23:3886–3896. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulrich H.D., Jentsch S. Two RING finger proteins mediate cooperation between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes in DNA repair. EMBO J. 2000;19:3388–3397. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedl A.A., Liefshitz B., Steinlauf R., Kupiec M. Deletion of the SRS2 gene suppresses elevated recombination and DNA damage sensitivity in rad5 and rad18 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 2001;486:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liefshitz B., Steinlauf R., Friedl A., Eckardt-Schupp F., Kupiec M. Genetic interactions between mutants of the ‘error-prone’ repair group of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their effect on recombination and mutagenesis. Mutat. Res. 1998;407:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith S., Hwang J.Y., Banerjee S., Majeed A., Gupta A., Myung K. Mutator genes for suppression of gross chromosomal rearrangements identified by a genome-wide screening in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9039–9044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403093101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson R.E., Henderson S.T., Petes T.D., Prakash S., Bankmann M., Prakash L. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD5-encoded DNA repair protein contains DNA helicase and zinc-binding sequence motifs and affects the stability of simple repetitive sequences in the genome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:3807–3818. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahne F., Jha B., Eckardt-Schupp F. The RAD5 gene product is involved in the avoidance of non-homologous end-joining of DNA double strand breaks in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:743–749. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis L.K., Westmoreland J.W., Resnick M.A. Repair of endonuclease-induced double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: essential role for genes associated with nonhomologous end-joining. Genetics. 1999;152:1513–1529. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulrich H.D. Protein–protein interactions within an E2-RING finger complex. Implications for ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7051–7058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisen J.A., Sweder K.S., Hanawalt P.C. Evolution of the SNF2 family of proteins: subfamilies with distinct sequences and functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2715–2723. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson R.E., Prakash S., Prakash L. Yeast DNA repair protein RAD5 that promotes instability of simple repetitive sequences is a DNA-dependent ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28259–28262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes G., Rine J. Regulated expression of endonuclease EcoRI in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: nuclear entry and biological consequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:1354–1358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.5.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hecht A., Grunstein M. Mapping DNA interaction sites of chromosomal proteins using immunoprecipitation and polymerase chain reaction. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:399–414. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies G.P., Powell L.M., Webb J.L., Cooper L.P., Murray N.E. EcoKI with an amino acid substitution in any one of seven DEAD-box motifs has impaired ATPase and endonuclease activities. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4828–4836. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.21.4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pause A., Sonenberg N. Mutational analysis of a DEAD box RNA helicase: the mammalian translation initiation factor eIF-4A. EMBO J. 1992;11:2643–2654. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richmond E., Peterson C.L. Functional analysis of the DNA-stimulated ATPase domain of yeast SWI2/SNF2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3685–3692. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.19.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siede W., Friedl A.A., Dianova I., Eckardt-Schupp F., Friedberg E.C. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku autoantigen homologue affects radiosensitivity only in the absence of homologous recombination. Genetics. 1996;142:91–102. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma J.L., Kim E.M., Haber J.E., Lee S.E. Yeast Mre11 and Rad1 proteins define a Ku-independent mechanism to repair double-strand breaks lacking overlapping end sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8820–8828. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8820-8828.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boulton S.J., Jackson S.P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku70 potentiates illegitimate DNA double-strand break repair and serves as a barrier to error-prone DNA repair pathways. EMBO J. 1996;15:5093–5103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegde V., Klein H. Requirement for the SRS2 DNA helicase gene in non-homologous end joining in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2779–2783. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.14.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orlando V. Mapping chromosomal proteins in vivo by formaldehyde-crosslinked-chromatin immunoprecipitation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolner B., van Komen S., Sung P., Peterson C.L. Recruitment of the recombinational repair machinery to a DNA double-strand break in yeast. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank-Vaillant M., Marcand S. Transient stability of DNA ends allows nonhomologous end joining to precede homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:1189–1199. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S.E., Moore J.K., Holmes A., Umezu K., Kolodner R.D., Haber J.E. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailly V., Lauder S., Prakash S., Prakash L. Yeast DNA repair proteins Rad6 and Rad18 form a heterodimer that has ubiquitin conjugating, DNA binding, and ATP hydrolytic activities. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23360–23365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costanzo V., Robertson K., Bibikova M., Kim E., Grieco D., Gottesman M., Carroll D., Gautier J. Mre11 protein complex prevents double-strand break accumulation during chromosomal DNA replication. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franchitto A., Pichierri P. Werner syndrome protein and the MRE11 complex are involved in a common pathway of replication fork recovery. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1331–1339. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.10.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singleton M.R., Wigley D.B. Modularity and specialization in superfamily 1 and 2 helicases. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1819-1826.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langst G., Becker P.B. Nucleosome remodeling: one mechanism, many phenomena? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1677:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chilton B.S., Hewetson A. Zinc finger proteins RUSH in where others fear to tread. Biol. Reprod. 1998;58:285–294. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramsey K.L., Smith J.J., Dasgupta A., Maqani N., Grant P., Auble D.T. The NEF4 complex regulates Rad4 levels and utilizes Snf2/Swi2-related ATPase activity for nucleotide excision repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:6362–6378. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6362-6378.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu S., Owen-Hughes T., Friedberg E.C., Waters R., Reed S.H. The yeast Rad7/Rad16/Abf1 complex generates superhelical torsion in DNA that is required for nucleotide excision repair. DNA Repair. 2004;3:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.