Abstract

Kinases modulate protein activities through phosphate group transfers, regulating cellular functions. Mutations in kinases are related to cancer initiation, progression, and recurrence. Kinase inhibitors, such as Crizotinib, have demonstrated efficacy against specific cancers; however, limitations and adverse effects necessitate the development and discovery of novel, potent inhibitors. This study employs Computer-Aided Drug Design techniques to develop natural product-based structures targeting the ROS1 Kinase Domain. Molecular fingerprints, molecular dynamics simulations, Docking, and quantum calculations are utilized for virtual screening and structure evaluation. A compound library is constructed, and candidates are screened based on Computer-Aided Drug Design techniques. Notably, one structure, named LIG48, demonstrated a substantial binding affinity and interactions with the ROS1 Kinase Domain and its mutant (G2032R ROS1 kinase domain). In addition, LIG48 and crizotinib remained within the mutated and wild-type ROS1 kinase domains in all replicas, for a total simulation time of 400 ns for each system. This research presents a promising and potentially effective route for designing kinase inhibitors that could address resistance and side effects associated with existing therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-22234-5.

Keywords: Computer-aided-drug-design, Crizotinib, Molecular dynamics simulations, Docking, Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase ROS, Protein simulation, MACCS

Subject terms: Computational models, Virtual drug screening

Introduction

Kinases are enzymes that play a crucial role in regulating cellular function by controlling protein activity through the transfer of phosphate groups to specific proteins1–3. Previous studies have shown that mutations in kinases are related to cancer initiation, promotion, progression, and recurrence due to their roles in cell proliferation, survival, and migration4–6. The importance of kinases in cancer and the discovery of imatinib, an effective kinase inhibitor against chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), led to the emergence of kinase inhibitors as potent agents for the treatment of various cancers7. Patients with lung cancer who harbor rearrangements in ROS1 exhibit a high response to treatment with the multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor Crizotinib8–10. Notably, fusion proteins resulting from chromosomal translocations involving kinase domains of ALK11 or ROS112 are of significant importance in the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma. Chromosomal translocations involving the kinase domain of ROS1 result in its constitutive activation. Subsequently, through the upregulation of the JAK/STAT, PI3K/AKT, and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways, cell proliferation, survival, and migration are increased13. Unfortunately, acquired resistance to Crizotinib through the G2032R mutation in ROS1 limits the efficacy of the drug14. Furthermore, Crizotinib has shown adverse events such as visual impairment, diarrhea, nausea, peripheral edema, constipation, vomiting, an elevated aspartate aminotransferase level, fatigue, dysgeusia, and dizziness15. In response to the limitations of Crizotinib, researchers have been developing alternative compounds such as ROS1 and ALK inhibitors. These efforts aim to improve the effectiveness and reliability of patient treatment options16,17. Considering that experimental techniques are high-cost and time-consuming18, computer-aided drug design (CADD) approaches such as docking and molecular dynamics simulation are impressive alternatives19. Molecular dynamics simulation is a computational technique that employs a force field and Newton’s law of motion to predict the forces acting between interacting atoms, compute the system’s total energy, and determine the positions and velocities of the particles over time. This technique can calculate various properties, such as free energy and kinetic measures, as well as other macroscopic quantities, which can be compared with experimental data. The advances in Molecular Dynamics Simulation have become increasingly helpful in drug design20,21. Docking, a simplified form of molecular dynamics simulation19, is another computational technique that can predict the enhancement or inhibition of proteins’ biological activity by inspecting Protein-small molecule (ligand), Protein-nucleic acid, or Protein–protein interactions22. In this work, we aimed to design natural-based structures that can potentially inhibit ROS1, overcome Crizotinib resistance, and reduce side effects. We took advantage of Molecular ACCess System keys (MACCS), which are a binary vector representation of molecules that utilizes 0 or 1 to denote the presence or absence of particular properties23 and computational methods such as Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations to avoid the high costs and time requirements associated with experimental techniques for novel drug discovery18. Through various simulations, examinations, and computational validations, we discovered that LIG48, a chemical compound composed of Cytosine, Proline, and Tryptophan, may alter the activity of the ROS1 Kinase Domain, similar to Crizotinib. ROS1 protein and ALK demonstrate significant homology in the ATP binding site15,24. Therefore, with a high probability, the mechanism of action of ROS1 is related to ATP and its binding sites. We can inhibit kinase activity with a ligand that can bind to the ATP binding site of the ROS1 Kinase domain, such as Crizotinib or our proposed ligand.

Method and theoretical calculations

Building a library of compounds based on amino acids and nucleobases

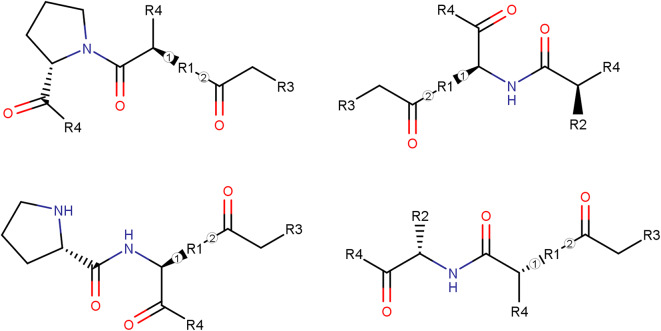

The naturally based structures were composed of three subcomponents: two amino acids and one nucleobase. The nucleobase was connected to one of the side chains of the amino acids by a carbonyl linker, specifically to N9 of Adenine and Guanine, and to N1 of Cytosine, Thymine, and Uracil. The described arrangement, as shown in Fig. 1, enabled the creation of a library containing 4800 compounds. A file in .smi format, including all the structures in SMILES representation, is provided in the supporting information. Structures composed of two amino acids and one nucleobase may serve as inhibitors of the ROS1 kinase domain because their combined features potentially allow them to interact with key regions within the ATP-binding pocket. The amino acid components might provide hydrophobic and polar contacts, while the nucleobase could offer aromatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions. For example, amino acids with side chains capable of hydrogen bonding or hydrophobic interactions—such as serine, threonine, or asparagine—might form contacts with the polar or charged residues of the DFG motif (like ASP169). Similarly, aromatic amino acids like phenylalanine or tyrosine could engage in stacking or hydrophobic interactions with the motif’s phenylalanine (PHE170). These interactions could help position the inhibitor within the binding site and potentially disrupt kinase activity.

Fig. 1.

R1: S, T, C, Y, W, D, E, N, Q, H, K, R (12 Amino Acids), R2: All 20 amino acids except proline, R3: A, T, C, G, or U, R4: both OH or NH2.

Virtual screening of the library

Three additional compounds, AstraZeneca Ligand 1 (PDB ID: 7Z5W), AstraZeneca Ligand 2 (PDB ID: 7Z5X), and Crizotinib (PDB ID: 3ZBF), were added to the library to assess the combination of MACCS and Tanimoto similarity23,25–27. Even though 2D fingerprints are simple representations of molecules, it has been reported that these types of feature representations can depict more efficacy than intricate features such as 3D structural patterns28,29. Based on a recent report30, MACCS fingerprints encompass numerous useful 2D features for virtual screening (VS) in drug design. The initial screening step was performed using the RDKit Library, employing MACCS fingerprints. These 166-bit binary vectors indicate the presence or absence of specific features in target chemical compounds23, and the Tanimoto similarity metric25–27 is widely regarded as one of the most practical measures of similarity31. The combination of Tanimoto similarity and MACCS fingerprints provided a numerical value based on the shared features and the number of total features in each chemical structure to measure the similarity between two different chemical compounds.

|

1 |

Variables: Na for the Total number of features in structure A, Nb for the Total number of features in structure B, and Nc for the number of shared features between structure A and B.

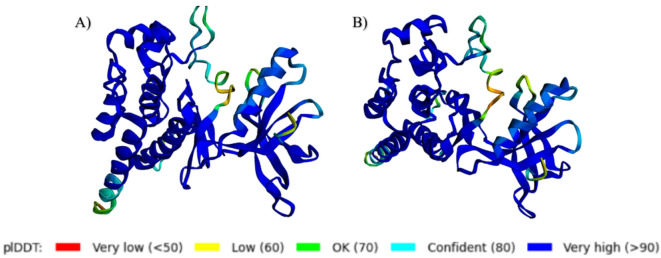

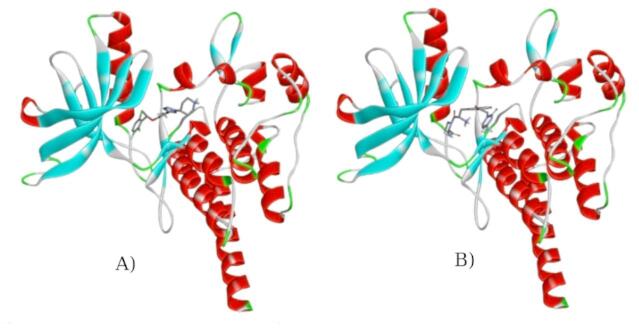

Reconstructing the ROS1 kinase domain

The available X-ray structure of the ROS1 kinase domain in complex with Crizotinib (PDB ID: 3ZBF) had missing sequences. Colabfold V 1.5.232–35 was used to reconstruct the complete 3D structure of the ROS1 kinase domain, both the wild-type and the mutant (G2032R). While options Tol: 0, number of recycles: 48, pairing strategy: complete, pair_mode: unpaired-paired, and template_mode: pdb100 were chosen, all other settings were kept at default values. The options were selected to maximize the accuracy of the protein structures. Structures A and B (predicted structures), shown in Fig. 2, were chosen for subsequent docking and molecular dynamics simulations.

Fig. 2.

Predicted structures of kinase domains of (A) ROS1 and (B) G2032R mutated ROS1 by Colabfold V 1.5.2. The 3D image was generated using Py3Dmol36.

The modeled missing residues are shown in Fig. 3. While the region containing two β-sheets and one α-helix, shown in the right panel of Fig. 3, is located far from the active site, residues 21, 22, and 23 are positioned closer to the ligand. Despite the long distance of these residues from the ligand (indicating that they are not part of the active site), they may still interact with the ligand, which will be examined in a later section using MMPBSA analysis. In addition, no disulfide bond was identified in the kinase domain of ROS1.

Fig. 3.

Modeled missing residues. The 3D image was generated using Mol*37.

Docking

The box center (X: 42.521, Y: 19.649, Z: 3.986) and box size (W: 18.823, H: 18.823, D: 18.823) for Docking were defined based on the location and the radius of gyration of Crizotinib in the 3ZBF structure, respectively. According to recent research, the box size based on the Radius of gyration increases the docking performance of AutoDock Vina38. Before minimization and to prepare LIG1-LIG50 for docking, the phmodel tool from the Open Babel Package39, which uses the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, was used to determine the dominant protonation state of the ligands at pH 7.4. 3D structures of the ligands were generated and minimized using the MMFF94s force field with 10,000 iterations. The final structures of LIG1-LIG50 were prepared using MGLTools40,41. LIG1-LIG50 were docked on structure A (ROS1 kinase domain), which was prepared for docking at pH 7.4 using MGLTools40,41, by AutoDock Vina42 with exhaustiveness set to 28. To perform blind docking, CB-Dock243,44, which outperforms other available docking platforms such as MTiAutoDock, SwissDock, COACH-D1, COACH-D2, and CB-Dock44, was used.

Evaluating toxicity using the LUMO–HOMO gap

In chemical structures with similar features, toxicity and chemical reactivity are proportional; higher reactivity typically corresponds to higher toxicity45. According to Tanimoto similarity, LIG48 and Crizotinib shared features and were 57% similar. Additionally, a larger HOMO–LUMO gap indicates lower chemical reactivity and higher kinetic stability, as adding electrons to a high-lying LUMO or removing electrons from a low-lying HOMO is an energetically unfavorable procedure46–48. To compare the HOMO–LUMO gaps of LIG48 and Crizotinib, structures were optimized using SPARTAN 1049. The initial conformational search was performed using the Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF). The geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were done using the DFT B3LYP 6–311 + G** basis set using SPARTAN 1049. The absence of imaginary frequencies confirmed that the optimized structures corresponded to the true minima.

Molecular dynamics (md) simulations

Protein MD simulation

The MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2020.150 OPLS-AA/M force field51 and LigParGen52–54 were employed to prepare topology files of the ligands and complexes. Parrinello-Raman55, V-rescale56, Particle Mesh Ewald57, LINCS algorithm58, and SPC/E59,60 were respectively utilized for barostat, thermostat, long-range electrostatic interactions, H-bond constraints, and water model for all NVT and NPT ensembles and MD simulations. The simulation boxes were defined as cubic, with all faces positioned 1.0 nm away from the closest atom of the systems. Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied to all simulations. Salt concentrations of 0.156 M were introduced using Na+ and Cl¯ ions to neutralize the systems and simulate body fluid conditions. Energy minimizations of complexes were conducted using the steepest descent algorithm to refine the structures and to remove steric clashes. Following the minimization steps, 100 ps of NVT and then 100 ps of NPT ensembles were used to equilibrate the system’s temperature and pressure. Finally, all systems were subjected to MD simulation times of 200 ns with a time step of 1 fs at a temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 bar. To ensure reproducibility and account for statistical variation61, two independent replicas were performed for each system under identical simulation conditions but with different random seeds. To assess stability, flexibility, compactness, secondary structures, and tertiary structures of proteins, plots of Root-Mean-Square-Deviation (RMSD), Root-Mean-Square-Fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of Gyration (Rg), Secondary Structure, and mean smallest distance were examined. Snapshots of MD simulations are available in Figure S3 (Rendered using VMD V1.9.362).

MD simulation and parametrization of ligands

Since LigParGen52 does not provide a penalty score; ligand validations were performed manually to ensure structural reliability. First, partial charges on electronegative atoms, obtained from LigParGen parameterization, were compared with those derived from Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6–311 + G** level, and the results showed good agreement except for Cl1 (Table S1 and Figure S1). To correct this, the charge of Cl1 was adjusted from − 0.0766 e to + 0.1200 e, and the excess charge was evenly redistributed across all non-hydrogen atoms to maintain charge neutrality. Second, 20ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the ligands in water were conducted under the same settings as the protein MD simulations. No bond breakage or significant deviations were observed, confirming the structural stability of the ligands.

MM/PBSA calculations

Binding free energies of Crizotinib and LIG48 on mutated and wild-type ROS1 proteins were calculated by the gmx_MMPBSA package63 using Molecular Mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area. Since gmx_MMPBSA was initially built for the AMBER force field and can convert OPLS topology files to AMBER format, free energy estimations were performed using the oldff/leaprc.ff99SB and leaprc.gaff force fields, at 300 K. The ionic strength of 0.156M, and frcmod.ions1lm_126_spce ions parameters were utilized. For free energy calculations, a total of 125 snapshots were collected from the last 125 ns of each replica, yielding 250 snapshots in total over a combined simulation time of 250 ns. Since the focus was on relative binding energies and the systems differed only slightly (Crizotinib has five rotatable bonds and LIG48 has 8, while the wild-type and mutant proteins differ by just a single residue), the entropy contributions were assumed to be small or consistent across systems. Therefore, entropy was not included in the free energy calculations.

Results and discussion

Library screening and similarity search

LIG1 (Crizotinib) and LIG18 (AstraZeneca ligand 2) had similarity scores of 1.00 and 0.583, respectively, to Crizotinib. Subsequently, the top 50 structures (LIG1-LIG50), shown in Figure S2, with the highest similarity scores, were selected for further evaluation using docking studies.

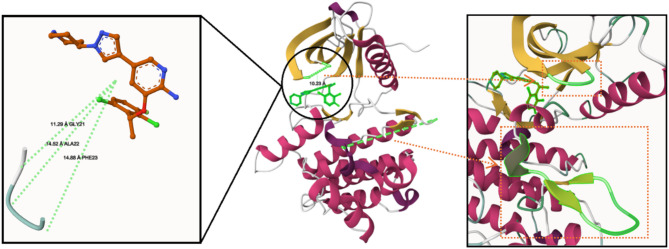

Docking

The docking results of 50 ligands and their structures are available in the supporting documents (Table S3 and Figure S2). After docking with AutoDock Vina42, eight structures, including LIG18 (AstraZeneca Ligand 2), were found to have higher binding affinities than Crizotinib toward ROS1 (Table 1). LIG42 and LIG48 had a similar pocket to that of Crizotinib (Fig. 4) and notably higher affinities than LIG1 (Crizotinib) (Table 2). LIG48 was chosen for its higher binding affinity compared to Crizotinib and LIG42 toward ROS1, as well as for having more interactions with ROS1 than LIG42 (Table 3). Docking of LIG48 and Crizotinib was performed on Structure B (G2032 mutated ROS1) using CB-Dock243,44. LIG48 again had a similar binding pocket to Crizotinib, as shown in Fig. 5, with a higher binding affinity (Table 4) and more interactions than LIG1 (Crizotinib) with the mutant ROS1 kinase domain (Table 5).

Table 1.

Docking results of AutoDock Vina.

| Rank | Ligand | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LIG48 | − 9.272 |

| 2 | LIG42 | − 8.961 |

| 3 | LIG18 (AstraZeneca Ligand 2) | − 8.95 |

| 4 | LIG31 | − 8.894 |

| 5 | LIG23 | − 8.821 |

| 6 | LIG10 | − 8.495 |

| 7 | LIG19 | − 8.447 |

| 8 | LIG27 | − 8.402 |

| 9 | LIG1 (Crizotinib) | − 8.27 |

Fig. 4.

Docking poses of (A) LIG1, (B) LIG42, (C) LIG48 with non-mutated ROS1 kinase domain resulted from CB-Dock2 The 3D image was generated using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer64.

Table 2.

CB-Dock2 Docking results (ROS1).

| Rank | Ligand | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LIG48 | − 9.1 |

| 2 | LIG42 | − 8.9 |

| 3 | LIG1 | − 8 |

Table 3.

Interactions of ligands with ROS1 resulted from CB-Dock2.

| Ligand | Interactions |

|---|---|

| LIG48 | LEU18 GLY19 VAL26 ALA45 GLU94 LEU95 MET96 GLU97 GLY98 GLY99 ASP100 THR103 LYS107 ARG150 ASN151 LEU153 PHE170 LEU172 ALA173 ILE176 TYR177 |

| LIG42 | LEU18 GLY19 VAL26 ALA45 GLU94 LEU95 MET96 GLU97 GLY98 GLY99 ASP100 THR103 LYS107 ARG150 ASN151 LEU153 PHE170 LEU172 ALA173 ILE176 TYR177 |

| LIG1 | LEU16 LEU18 GLY19 SER20 VAL26 GLU28 ALA45 GLU94 LEU95 MET96 GLU97 GLY98 GLY99 ASP100 ARG150 LEU153 LYS157 PHE170 LEU172 ALA173 ILE176 TYR177 |

Fig. 5.

Docking poses of (A) LIG1 and, (B) LIG48 with G2032R mutated ROS1 kinase domain resulted from CB-Dock2 The 3D image was generated using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer64.

Table 4.

CB-Dock2 Docking results of G2032R mutated ROS1.

| Rank | Ligand | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LIG48 | − 8.9 |

| 2 | LIG1 | − 8.3 |

Table 5.

Interactions of ligands with the G2032R mutated ROS1 resulted from CB-Dock2.

| Ligand | Interactions |

|---|---|

| LIG48 | LEU18 GLY19 VAL26 ALA45 LEU77 LEU93 GLU94 LEU95 MET96 GLU97 ARG99 ASP100 THR103 LYS107 ARG150 LEU153 PHE170 LEU172 ALA173 ILE176 TYR177 |

| LIG42 | LEU18 GLY19 VAL26 ALA45 LEU77 LEU93 GLU94 LEU95 MET96 ARG99 ASP100 THR103 ARG150 LEU153 PHE170 ALA173 ILE176 TYR177 |

| LIG1 | LEU18 GLY19 VAL26 ALA45 LEU77 LEU93 GLU94 LEU95 MET96 ARG99 ASP100 THR103 ARG150 LEU153 PHE170 LEU172 ALA173 ILE176 TYR177 |

Toxicity evaluation

Energies of HOMO and LUMO of Crizotinib and LIG48 were, respectively, − 5.52 eV, − 1.56 eV, − 6.36 eV, and − 1.61 eV, which indicated that LIG48 had a larger HOMO–LUMO gap, 4.75 eV, than Crizotinib, 3.96 eV, and subsequently LIG48 had lower reactivity. Therfore, LIG48 should have lower toxicity than Crizotinib. Optimized structures, including HOMO and LUMO orbitals, of Crizotinib and LIG48 are depicted in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

LUMOs and HOMOs of optimized structures of Top Crizotinib and Bottom LIG48 The molecular structure was rendered using Wavefunction Spartan 1049.

Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic profiling of the lead compound

The provided ligand (LIG48), with a molecular weight of 451.48 Da and a formula of C₂₂H₂₅N₇O₄, exhibited moderate molecular complexity, as indicated by the presence of 33 heavy atoms and a high degree of aromaticity (15 aromatic heavy atoms). Its topological polar surface area (TPSA) was calculated as 172.33 Å2, exceeding the well-known threshold of 140 Å2 for optimal membrane permeability. As a result, low gastrointestinal (GI) absorption and a lack of blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability were predicted. Drug-like characteristics were retained, as the hydrogen-bond donor (3) and acceptor (6) counts remained within acceptable ranges, along with a moderate number of rotatable bonds (8). No PAINS65, or Brenk66, alerts were detected, suggesting low toxicity and good pharmacological tractability. A bioavailability score of 0.55 was assigned, indicating moderate oral potential, and a synthetic accessibility score of 4.06 suggested that the ligand is reasonably synthesizable. Regarding physicochemical properties, slight hydrophilicity was indicated by a consensus Log P of − 0.25. Excellent aqueous solubility was predicted across multiple models, including an ESOL-predicted solubility of 7.72 mg/mL. Additionally, the ligand was not identified as a substrate for P-glycoprotein. It was not predicted to inhibit major cytochrome P450 enzymes, suggesting a low risk of drug–drug interactions and favorable metabolic stability. However, violations were noted in at least one criterion across all commonly used drug-likeness filters (Lipinski67, Ghose68, Veber69, Egan70, Muegge71), primarily due to its high polarity and/or molecular size. Overall, the ligand was considered a promising drug candidate, exhibiting excellent solubility, low toxicity, and a clean metabolic profile. SwissADME72 was used to generate the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties. All the provided data are presented in Table S4.

Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) analysis

RMSD (root-mean-squared deviation) values of protein backbones were utilized to investigate whether systems were equilibrated. According to Fig. 7, in all systems, between 75 and 200 ns, protein backbone RMSD values of Complexes of Crizotinib-ROS1, Crizotinib-mutant ROS1, LIG48-ROS1, and LIG48-mutant ROS1 fluctuated in the ranges of 0.147–0.275 nm, 0.137–0.309 nm, 0.203–0.363 nm, and 0.191–0.327 nm, respectively. During the last 125 ns of simulations, all structures had protein backbone fluctuations within a range of 0.172 nm, indicating that all systems were in equilibrium and converged states. Importantly, across the entire simulation, the ligands stayed within the active sites of proteins.

Fig. 7.

RMSD plots.

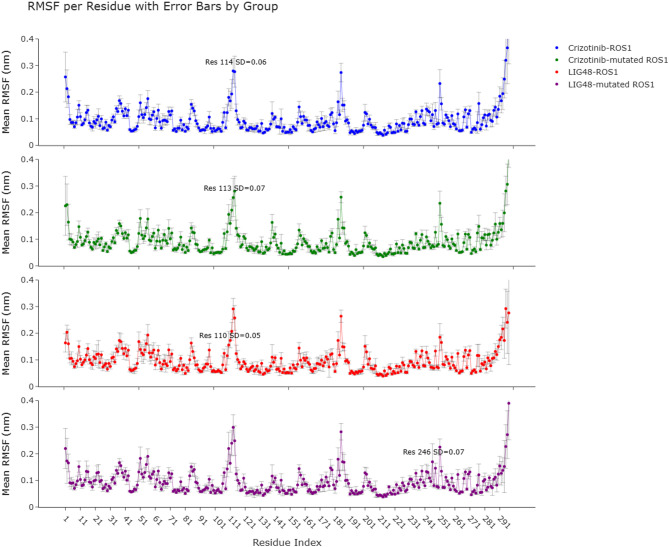

Root-mean-squared-fluctuation (RMSF) analysis

The last 125 ns of MD simulations from all replicas were used to plot the RMSF values of proteins, assessing protein flexibility. Since two replicas were performed for each system, a total of 250 ns of simulation data per system was analyzed. The last 125 ns of MD simulations from each of the two replicas were combined to yield a 250 ns trajectory per system, which was used to assess protein flexibility via RMSF analysis. This combined trajectory was divided into consecutive 10-ns windows, and RMSF was calculated for each window. The resulting values were used to determine the mean RMSF along with error bars. The maximum RMSF value is also highlighted in Fig. 8, excluding the five terminal residues at both the N- and C-termini from the analysis. As shown in Fig. 8, all systems had similar trends in RMSF plots. Mean values of RMSFs of Crizotinib-ROS1, Crizotinib-mutant ROS1, LIG48-ROS1, and LIG48-mutant ROS1 were 0.0948, 0.0910, 0.0950, and 0.0941, respectively. RMSF and protein flexibility are proportionally related. Higher RMSF means higher flexibility and vice versa. Additionally, there is a relationship between flexibility and enzyme catalytic activity: the lower the flexibility, the lower the catalytic activity73. According to the mean RMSF values, the flexibility of ROS1 and mutant ROS1 complexes with LIG48 more closely resembled that of the Crizotinib-ROS1 complex than the Crizotinib-mutated ROS1 complex, indicating a comparable catalytic activity.

Fig. 8.

RMSF plots.

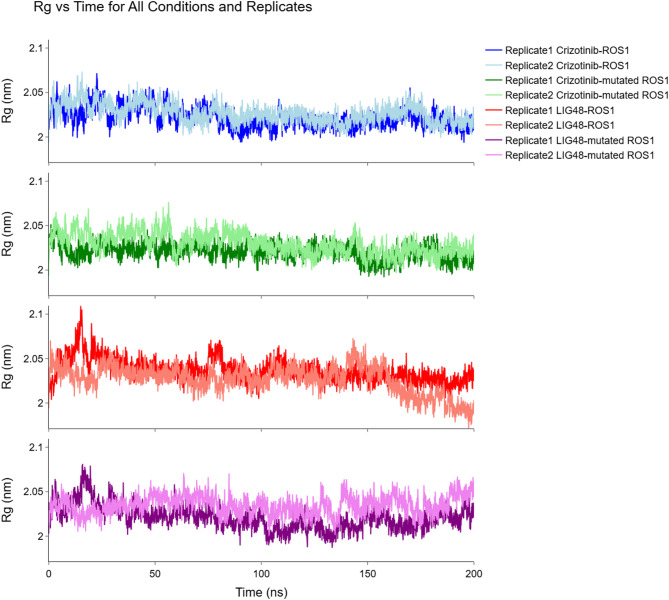

Radius of gyration (Rg)

Proteins must be folded into specific, three-dimensional structures to function correctly74, and protein compactness plays a crucial role in determining protein folding75. Furthermore, the radius of gyration is related to protein compactness76. Thus, the radius of gyration is an indicator of protein functionality. As depicted in Fig. 9, both mutant and non-mutant proteins, when complexed with Crizotinib and LIG48, displayed Rgs below 2.08 nm during the last 125 ns of the MD simulation for all replicas. Therefore, the folding of proteins and, as a result, the functions of proteins in all systems are almost similar. If the ROS1-Crizotinib complex has no functionality and is inhibited, the proteins in all three other complexes will also be inhibited, as they have similar plots of the Rgs.

Fig. 9.

Rg plots.

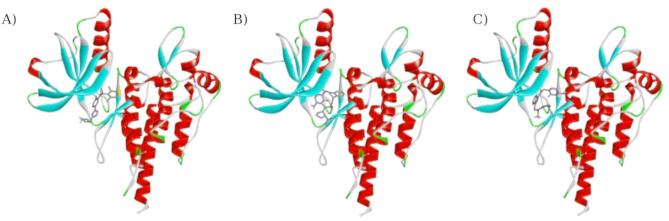

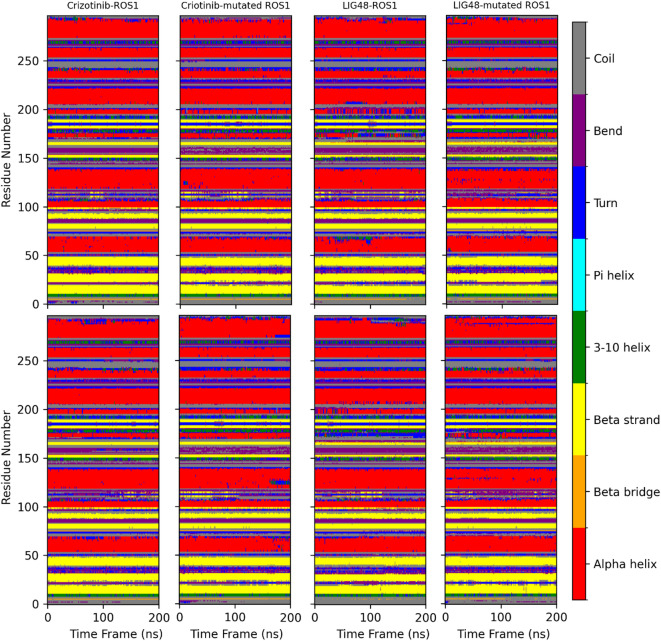

Secondary structure analysis

The secondary structure analysis focused on the last 125 ns of equilibrated MD simulations across all systems. The ROS1 kinase domain maintained a predominantly stable secondary structure throughout, with alpha helices and beta strands as the main features, thereby preserving the native fold. Coil, turn, and bend regions appeared sporadically in loop areas, as expected. Consistency between replicate simulations highlighted the robustness of the results, with no significant unfolding or global structural deviations observed. Local differences were noted between systems. In residues 20–27, β-sheets were more prevalent and coils were less frequent in the Crizotinib-ROS1 complex compared to the Crizotinib-mutant complex. ROS1 and mutant ROS1 bound to LIG48 exhibited increased bend conformations relative to their Crizotinib counterparts. Between residues 85–90, all systems except the Crizotinib-mutant complex displayed β-sheet and coil conformations, with that residue adopting coil only in the mutant complex. Residues 105–120 showed more coil and less bend in Crizotinib-ROS1 than Crizotinib-mutant ROS1, while LIG48-ROS1 mirrored the Crizotinib-ROS1 pattern. The LIG48-mutant complex briefly exhibited β-bridge conformations in two residues. A residue between 110–120 adopts a bend structure only in the Crizotinib-mutant complex, but coils in others. From residues 145–155, coils and 3-helix structures were more prevalent in the Crizotinib-ROS1 complex, whereas turns, bends, and β-sheets dominated in the Crizotinib-mutant complex. LIG48 complexes resembled the mutant but trended toward the wild-type Crizotinib profile. At residues 150–155, a residue showed both β-sheet and coil conformations in Crizotinib-ROS1 but only β-sheet in the mutant; LIG48 complexes resembled Crizotinib-ROS1, exhibiting coil and bend forms. Between residues 155–165, Crizotinib-ROS1 and LIG48-ROS1 had more turns and fewer bends than the mutant complexes. Residues 165–170 in Crizotinib-ROS1 exhibited both β-bridge and β-sheet conformations, whereas the mutant showed only β-sheet; the LIG48-mutant complex displayed a higher frequency of bends. Residues 170–175 and 180–190 further reflected these trends, with Crizotinib-ROS1 showing more bends and fewer turns than Crizotinib-mutant, and LIG48-mutant exhibiting increased turns and bends. Finally, between residues 205–210, turns were more frequent and α-helices were less common in the Crizotinib-ROS1 complex compared to the mutant complex. Apart from terminal residues, secondary structures were conserved mainly across all systems. Overall, the mutation G2032R and ligand replacement with LIG48 did not cause significant global changes but induced subtle local flexibility variations, particularly increased coil and turn content in the central region (~ residues 100–200) of the LIG48–mutant complex. These localized rearrangements may influence binding affinity and dynamics. The high reproducibility across replicas supports the structural stability and reliability of these findings (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Secondary structure plots for replica 1 (First row) and replica 2 (Second row).

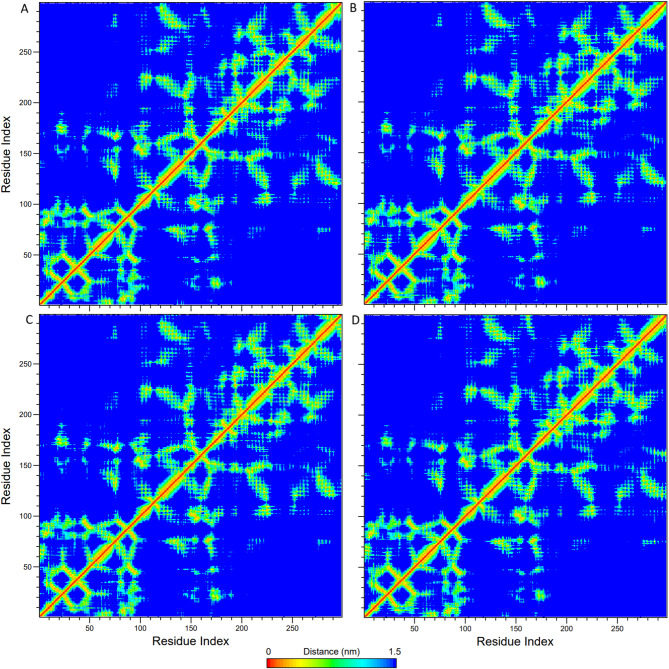

Tertiary structure analysis

Mean Smallest Distance plots were sketched for all proteins to investigate the tertiary structures. As depicted in Fig. 11, there were no noticeable differences between plots that would indicate tertiary structure differences in all MD simulations. All tertiary structures of proteins were assumed to be highly similar.

Fig. 11.

Mean Smallest Distance plots of (A) Crizotinib-ROS1 (B) Crizotinib-mutated ROS1, (C) LIG48-ROS1, and (D) LIG48 mutated-ROS1 complexes.

MM/PBSA calculations

As shown in Table 6, Crizotinib and LIG48 illustrated favorable binding energies to both the Mutated and Non-mutated ROS1 kinase domains.

Table 6.

Binding energies.

| Ligand | Binding energy to non-mutated ROS1 kinase domain (Kcal/mol) | Binding energy to mutated ROS1 kinase domain (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Crizotinib | − 32.29, Standard deviation (3.85) | − 26.19, Standard deviation (3.32) |

| LIG48 | − 19.17, Standard deviation (3.96) | − 15.68, Standard deviation (5.30) |

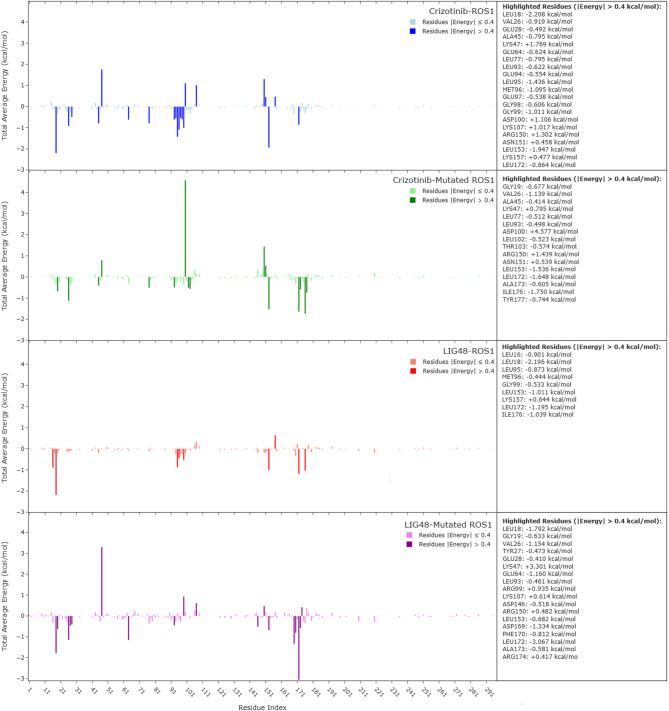

Total energy decomposition

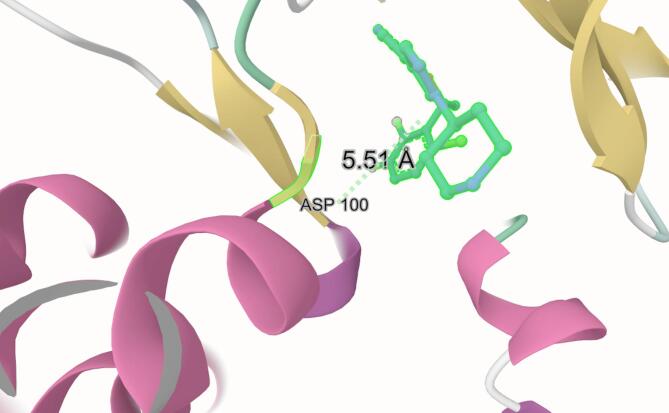

Energy decomposition analysis was performed using the gmx_MMPBSA package63, employing the Poisson–Boltzmann model with parameters consistent with those described in Sect. “Method and theoretical calculations”− 6–3 for binding free energy calculations (Fig. 12). The per-residue energy contributions were analyzed to identify key interactions between each ligand and the ROS1 kinase domain in both its wild-type and G2032R-mutated forms. Residues with average interaction energies greater than ± 0.4 kcal/mol were considered significant contributors to binding, whether stabilizing (negative) or destabilizing (positive). In the Crizotinib–ROS1 complex, residues with strongly favorable (stabilizing) interactions included LEU18, VAL26, GLU28, ALA45, GLU64, LEU77, LEU93, GLU94, LEU95, MET96, GLU97, GLY98, GLY99, LEU153, and LEU172, with interaction energies ranging from − 0.4 to − 2.2 kcal/mol. These residues are predominantly hydrophobic or polar uncharged, likely contributing to Crizotinib’s affinity via van der Waals and hydrophobic contacts, consistent with its binding deep within the ATP-binding cleft—a relatively non-polar pocket. Conversely, LYS47, ASP100, LYS107, ARG150, ASN151, and LYS157 exhibited unfavorable (positive) interaction energies, indicating electrostatic repulsion or conformational strain. Notably, ASP100—although not part of the DFG motif (residues 169–171)77 —is positioned within the ATP-binding pocket and may participate in Mg2⁺ coordination during catalysis. Its interaction with Crizotinib was mildly destabilizing in the wild-type system (+ 1.106 kcal/mol), and Fig. 13 reveals that Crizotinib remains in relatively close proximity to ASP100, with an average distance of 5.51 Å, highlighting the spatial relevance of this interaction despite its modest energetic penalty. In the mutated system, favorable interactions were diminished overall. Residues such as VAL26, ALA45, LEU77, LEU93, LEU102, THR103, LEU153, LEU172, ALA173, ILE176, and TYR177 retained their stabilizing contributions, but others—particularly MET96, GLU97, GLY98, and GLY99—lost their contributions, suggesting a reduction in both hydrophobic and polar compatibility. Most strikingly, ASP100 displayed a highly unfavorable interaction energy of + 4.577 kcal/mol in the G2032R-mutated complex, which was a dramatic increase compared to the wild-type. This destabilization likely arises from steric and electrostatic clashes introduced by the G2032R substitution, which places a bulky, positively charged arginine side chain in close proximity to ASP100. Supporting this, elevated repulsion was also observed from LYS47 (+ 0.795 kcal/mol) and ARG150 (+ 1.439 kcal/mol), further indicating that electrostatic conflict plays a major role in Crizotinib’s reduced efficacy against the mutant kinase. By contrast, the LIG48–ROS1 complex retained strong stabilizing interactions with residues LEU16, LEU18, LEU95, MET96, GLY99, LEU153, LEU172, and ILE176. Except for a modest repulsion from LYS157 (+ 0.644 kcal/mol), no highly unfavorable interactions were observed, suggesting that LIG48 is well accommodated in the binding pocket. Compared to Crizotinib, LIG48 forms similar favorable contacts but avoids the severe electrostatic penalties, reflecting a better fit under wild-type conditions. In the mutated system, LIG48 preserved or even enhanced its favorable interactions, notably with LEU18, GLY19, VAL26, TYR27, GLU28, GLU64, LEU93, ASP146, LEU153, ASP169, PHE170, LEU172, ALA173, and ILE176. Importantly, ASP169 and PHE170 are part of the DFG motif, and their strong negative contributions (− 1.334 and − 0.812 kcal/mol, respectively) suggest that LIG48 engages this critical regulatory region effectively. Although some unfavorable interactions were present—e.g., LYS47 (+ 3.301 kcal/mol), ARG99 (+ 0.935 kcal/mol), LYS107 (+ 0.614 kcal/mol), ARG150 (+ 0.482 kcal/mol), and ARG174 (+ 0.417 kcal/mol)—their magnitudes were generally modest compared to ASP100’s severe penalty in the Crizotinib–mutated ROS1 complex. These results suggest that LIG48 better tolerates the altered electrostatic landscape introduced by the G2032R mutation and may retain inhibitory activity where Crizotinib fails. In addition, residues 21, 22, and 23, which were modeled have shown no recognizable interaction with any of the ligands.

Fig. 12.

Energy Decomposition Analysis (Poisson-Boltzmann model).

Fig. 13.

ASP100–Crizotinib distance The 3D image was generated using Mol*37

Conclusion

In this work, natural-based structures were designed based on nucleobases and amino acids, and their abilities to act as an alternative to Crizotinib were examined using computer-aided drug design approaches. First, 2D fingerprints were used to find the most similar structures. In the next step, docking studies were used to compare the affinities and interactions of the designed structures with the original Crizotinib drug, identifying the best candidates. For further evaluation and examination of the toxicity, Quantum calculations were employed to use LUMO–HOMO gaps as indicators of toxicity. Final studies included MD simulations to reveal the final structure’s effectiveness and investigate the systems in dynamic conditions. Studies of MD simulations showed that systems of LIG48 (Fig. 14) complexed with wild-type and mutant ROS1 kinase domains were more similar to the system of Crizotinib complexed with wild-type ROS1 than systems including mutant ROS1 and Crizotinib were. Comprehensive energy decomposition analysis provided key mechanistic insights into how Crizotinib and LIG48 interact with both the wild-type and G2032R-mutated ROS1 kinase domains. Crizotinib’s binding relies mostly on interactions within the non-polar ATP-binding pocket. It is significantly compromised by the G2032R mutation, primarily due to a strongly repulsive interaction with ASP100, a residue likely involved in Mg2⁺ coordination during ATP hydrolysis. In contrast, LIG48 exhibited a more adaptable interaction profile, maintaining favorable contacts even in the mutated receptor and establishing strong interactions with the conserved DFG motif and adjacent hydrophobic residues, which are essential for kinase regulation. The diminished efficacy of Crizotinib in the G2032R mutant arises from electrostatic and steric clashes, particularly with ASP100, whereas LIG48’s broader and more flexible binding mode enables it to retain activity despite the mutation. These findings highlight the crucial role of second-shell residues such as ASP100 and the electrostatic plasticity of the kinase pocket in guiding inhibitor design. Moreover, free energy calculations derived from molecular dynamics simulations confirmed that both Crizotinib and LIG48 exhibit overall favorable (negative) binding energies toward both wild-type and mutant ROS1 kinase domains. The results of all computational calculations, including 2D fingerprint similarity, Docking, toxicity evaluation, physicochemical properties, and MD simulations, indicated that the proposed structure, LIG48, can be a potential alternative for Crizotinib, since it has shown favorable affinities towards ROS1 and mutant ROS1 and even lower toxicity compared to that of Crizotinib. MD simulations demonstrated that LIG48 can inhibit ROS1 and cause the ROS1 kinase domain to acquire a similar functionality, activity, secondary structure, and tertiary structure to that when it is complexed with Crizotinib. Furthermore, proteases hydrolyze peptide bonds even if the peptides are injected into the bloodstream. However, there are some strategies to reduce this hydrolysis. Modifications to the stereochemical configuration of peptides, alkylation of the backbone amide nitrogen, replacement of the charged C-terminal carboxylate with a neutral carboxamide, and addition of an uncharged pyroglutamyl residue to the N-terminus are methods that can exceptionally lengthen the half-life of peptides in the bloodstream78. Herein, we considered adding the nucleobase to the side chain of the amino acids as a modification to increase the half-life of our suggested structures. Together, these results suggest that future ROS1 inhibitors should aim to minimize unfavorable interactions with mutation-sensitive residues while enhancing engagement with conserved motifs, such as the DFG loop, to ensure robust inhibition across variant kinase forms.

Fig. 14.

The structures of LIG1 or Crizotinib, and LIG48 as a potential alternative for Crizotinib.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Sharif High-Performance Computing (HPC) Center and the Iranian National Science Foundation (INSF) for providing the computational resources for this research.

Author contributions

MJ. M. performed the project and wrote the main manuscript, and A. F. conducted his research and reviewed this manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coussens, L. et al. Multiple, distinct forms of bovine and human protein kinase C suggest diversity in cellular signaling pathways. Science233(4766), 1986. 10.1126/science.3755548 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manning, G., Whyte, D. B., Martinez, R., Hunter, T. & Sudarsanam, S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science10.1126/science.1075762 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabbro, D., Cowan-Jacob, S. W. & Moebitz, H. Ten things you should know about protein kinases: IUPHAR review 14. Br. J. Pharmacol.10.1111/bph.13096 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kittler, H. & Tschandl, P. Driver mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway: the seeds of good and evil. J. Dermatol.10.1111/bjd.16119 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer, G., Tarkowski, B. & Baccarini, M. Raf kinases in cancer-roles and therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene10.1038/onc.2011.160 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köstler, W. J. & Zielinski, C. C. “Targeting receptor tyrosine kinases in cancer”, receptor tyrosine kinases: Structure. Funct. Role Human Dis.10.1007/978-1-4939-2053-2_10/COVER (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kannaiyan, R. & Mahadevan, D. A comprehensive review of protein kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther.10.1080/14737140.2018.1527688 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergethon, K. et al. ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J. Clin. Oncol.10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6345 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies, K. D. et al. Identifying and targeting ROS1 gene fusions in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0550 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.“Clinical activity of crizotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring ROS1 gene rearrangement,” 2012. 10.1200/jco.2012.30.15_suppl.7508.

- 11.Soda, M. et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature10.1038/nature05945 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rikova, K. et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roskoski, R. “ROS1 protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of ROS1 fusion protein-driven non-small cell lung cancers. Pharmacol. Res.10.1016/j.phrs.2017.04.022 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Awad, M. M. et al. Acquired resistance to crizotinib from a mutation in CD74 – ROS1. New Eng. J. Med.10.1056/nejmoa1215530 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw, A. T. et al. Crizotinib in ROS1 -rearranged non–small-cell lung cancer. New Engl. J. Med.10.1056/nejmoa1406766 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakamoto, H. et al. CH5424802, a selective ALK inhibitor capable of blocking the resistant gatekeeper mutant. Cancer Cell10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.004 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama, R. et al. Therapeutic strategies to overcome crizotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancers harboring the fusion oncogene EML4-ALK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A10.1073/pnas.1019559108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers, S. & Baker, A. Drug discovery—An operating model for a new era. Nat. Biotechnol.10.1038/90765 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.L. Zheng, A. A. Alhossary, C. K. Kwoh, and Y. Mu, “Molecular dynamics and simulation,” in Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology: ABC of Bioinformatics, vol. 1–3, 2018. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20284-7.

- 20.Allen, M. P. & Tildesley, D. J. Computer Simulation of Liquids 2nd edn. (Oxford university Press, 2017). 10.1093/oso/9780198803195.001.0001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frenkel, D., Smit, B., Tobochnik, J., McKay, S. R. & Christian, W. Understanding molecular simulation. Comput. Phys.10.1063/1.4822570 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy, K., Kar, S. & Das, R. N. “Other related techniques”, understanding the basics of QSAR for applications in pharmaceutical sciences and risk. Assessment10.1016/b978-0-12-801505-6.00010-7 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durant, J. L., Leland, B. A., Henry, D. R. & Nourse, J. G. Reoptimization of MDL keys for use in drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci.10.1021/ci010132r (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davare, M. A. et al. Structural insight into selectivity and resistance profiles of ROS1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci U S A10.1073/pnas.1515281112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willett, P., Barnard, J. M. & Downs, G. M. Chemical similarity searching. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci.10.1021/ci9800211 (1998).9538517 [Google Scholar]

- 26.T. T. Tanimoto, “An Elementary Mathematical Theory of Classification and Prediction,” 1958.

- 27.Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone. New Phytol.10.1111/j.1469-8137.1912.tb05611.x (1912). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scior, T. et al. “Recognizing pitfalls in virtual screening: A critical review. J. Chem. Info. Model.10.1021/ci200528d (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willett, P. “Similarity-based virtual screening using 2D fingerprints. Drug Discov. Today10.1016/j.drudis.2006.10.005 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellor, C. L. et al. Molecular fingerprint-derived similarity measures for toxicological read-across: Recommendations for optimal use. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.11.002 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bajusz, D., Rácz, A. & Héberger, K. Why is Tanimoto index an appropriate choice for fingerprint-based similarity calculations?. J. Cheminform.10.1186/s13321-015-0069-3 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek, M. et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science373(6557), 2021. 10.1126/science.abj8754 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R. Evans et al., “Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer,” bioRxiv, 2022.

- 35.Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rego, N. & Koes, D. 3Dmol.js: Molecular visualization with WebGL. Bioinformatics10.1093/bioinformatics/btu829 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sehnal, D. et al. Mol∗viewer: Modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res.10.1093/nar/gkab314 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feinstein, W. P. & Brylinski, M. Calculating an optimal box size for ligand docking and virtual screening against experimental and predicted binding pockets. J. Cheminform.10.1186/s13321-015-0067-5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform.10.1186/1758-2946-3-33 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.M. Sanner, D. Stoffler, and A. Olson, “ViPEr, a visual programming environment for Python,” Proc. 10th Int. Python Conf., 2002.

- 41.Sanner, M. F. Python: A programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph Model17(1), 57–61 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.10.1002/jcc.21334 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang, X., Liu, Y., Gan, J., Xiao, Z. X. & Cao, Y. FitDock: Protein–ligand docking by template fitting. Brief. Bioinform.10.1093/bib/bbac087 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, Y. et al. CB-Dock2: improved protein-ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res.10.1093/nar/gkac394 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.J. R. Centre, I. for Health, C. Protection, D. Asturiol, and A. Worth, The use of chemical reactivity assays in toxicity prediction. Publications Office, 2011. 10.2788/32951.

- 46.Yoshida, M. & Ichi Aihara, J. Validity of the weighted HOMO-LUMO energy separation as an index of kinetic stability for fullerenes with up to 120 carbon atoms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.10.1039/a807917j (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aihara, J. I. Weighted HOMO-LUMO energy separation as an index of kinetic stability for fullerenes. Theor. Chem. Acc.10.1007/s002140050483 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aihara, J. I. Reduced HOMO-LUMO gap as an index of kinetic stability for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A10.1021/jp990092i (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shao, Y. et al. “Advances in methods and algorithms in a modern quantum chemistry program package. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.10.1039/b517914a (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindahl, Abraham, Hess, and van der Spoel, GROMACS 2020.1 Manual, 2020,10.5281/ZENODO.3685920

- 51.Robertson, M. J., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. Improved peptide and protein torsional energetics with the OPLS-AA force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput.10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00356 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dodda, L. S., De Vaca, I. C., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. LigParGen web server: An automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res.10.1093/nar/gkx312 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dodda, L. S., Vilseck, J. Z., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. 1.14∗CM1A-LBCC: Localized bond-charge corrected CM1A charges for condensed-phase simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b00272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.W. L. Jorgensen and J. Tirado-Rives, “Potential energy functions for atomic-level simulations of water and organic and biomolecular systems,” 2005. 10.1073/pnas.0408037102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys.10.1063/1.328693 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys.10.1063/1.2408420 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys.10.1063/1.464397 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hess, B., Bekker, H., Berendsen, H. J. C. & Fraaije, J. G. E. M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem.18(12), 1463–1472. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12%3c1463::AID-JCC4%3e3.0.CO;2-H (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chatterjee, S., Debenedetti, P. G., Stillinger, F. H. & Lynden-Bell, R. M. A computational investigation of thermodynamics, structure, dynamics and solvation behavior in modified water models. J. Chem. Phys.10.1063/1.2841127 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berendsen, H. J. C., Grigera, J. R. & Straatsma, T. P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem.10.1021/j100308a038 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knapp, B., Ospina, L. & Deane, C. M. Avoiding false positive conclusions in molecular simulation: The importance of replicas. J. Chem. Theory Comput.10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00391 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valdés-Tresanco, M. S., Valdés-Tresanco, M. E., Valiente, P. A. & Moreno, E. Gmx_MMPBSA: A new tool to perform end-state free energy calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput.10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00645 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D. S. BIOVIA, “Discovery Studio Visualizer v21.1.0.20298,” BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes.

- 65.Baell, J. B. & Holloway, G. A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med Chem.10.1021/jm901137j (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brenk, R. et al. Lessons learnt from assembling screening libraries for drug discovery for neglected diseases. ChemMedChem10.1002/cmdc.200700139 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.019 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghose, A. K., Viswanadhan, V. N. & Wendoloski, J. J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem.10.1021/cc9800071 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem.10.1021/jm020017n (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Egan, W. J. & Lauri, G. Prediction of intestinal permeability. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev.10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00004-2 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muegge, I. Selection criteria for drug-like compounds. Med. Res. Rev.10.1002/med.10041 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.10.1038/srep42717 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richard, J. P. Protein flexibility and stiffness enable efficient enzymatic catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.10.1021/jacs.8b10836 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vella, F. The cell. A molecular approach. Biochem. Educ.10.1016/s0307-4412(98)00065-x (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galzitskaya, O. V., Bogatyreva, N. S. & Ivankov, D. N. Compactness determines protein folding type. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol.10.1142/S0219720008003618 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lobanov, M. Y., Bogatyreva, N. S. & Galzitskaya, O. V. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol. Biol.10.1134/S0026893308040195 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lahiry, P., Torkamani, A., Schork, N. J. & Hegele, R. A. Kinase mutations in human disease: Interpreting genotype-phenotype relationships. Nat. Rev. Gene.10.1038/nrg2707 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D. Van Vranken and G. A. Weiss, Introduction to Bioorganic Chemistry and Chemical Biology. 2018. 10.1201/9780203381090

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].