Abstract

Long interspersed elements (LINEs) are ubiquitous genomic elements in higher eukaryotes. Here we develop a novel assay to analyze in vivo LINE retrotransposition using the telomeric repeat-specific elements SART1 and TRAS1. We demonstrate by PCR that silkworm SART1, which is expressed from a recombinant baculovirus, transposes in Sf9 cells into the chromosomal (TTAGG)n sequences, at the same specific nucleotide position as in the silkworm genome. Thus authentic retrotransposition by complete reverse transcription of the entire RNA transcription unit and occasional 5′ truncation is observed. The retrotransposition requires conserved domains in both open reading frames (ORFs), including the ORF1 cysteine– histidine motifs. In contrast to human L1, recognition of the 3′ untranslated region sequence is crucial for SART1 retrotransposition, which results in efficient trans-complementation. Swapping the endonuclease domain from TRAS1 into SART1 converts insertion specificity to that of TRAS1. Thus the primary determinant of in vivo target selection is the endonuclease domain, suggesting that modified LINEs could be used as gene therapy vectors, which deliver only genes of interest but not retrotransposons themselves in trans to specific genomic locations.

Keywords: endonuclease/LINE/non-LTR retrotransposon/SART1/telomeric repeat

Introduction

The recent progress of genome projects has revealed an abundance of transposable elements in higher eukaryotic genomes. In humans, ∼45% of the genome is comprised of transposable elements (Lander et al., 2001). Among these elements, DNA transposons account for only 3%. The most abundant group is long interspersed elements (LINEs), which make up 21% of the genome (Weiner et al., 1986; Smit et al., 1999). LINEs are a major class of retrotransposable elements, which transpose through the RNA intermediates by self-encoding reverse transcriptase (RT) activity. LINEs shape mammalian genomes through de novo disease formation, exon shuffling and mobilization of short interspersed elements (SINEs) and processed pseudogenes (Kazazian et al., 1988; Moran et al., 1999; Esnault et al., 2000). LINEs, also called non-long terminal repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons, use a less characterized transposition mechanism than LTR retrotransposons and retroviruses, which use LTRs as essential cis elements for reverse transcription (Boeke and Stoye, 1997).

LINEs can be classified into two subtypes (Malik et al., 1999). One subtype is characterized by the existence of a restriction enzyme-like endonuclease domain 3′ to the RT domain, and a single open reading frame (ORF) in most cases. This group has an evolutionarily ancient origin and in all cases retrotransposition is directed to specific target sequences. In vitro biochemical analysis of such an element, R2, led to the current model for non-LTR retrotransposition. The R2 ORF protein could make a specific nick on the target site of 28S rDNA and use this nick to prime reverse transcription of the RNA (Luan et al., 1993). This mechanism is termed target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT).

The other type of LINEs is hallmarked by the existence of an apurinic/apyrimidinic-like endonuclease (APE) domain 5′ to the RT domain, and two ORFs in most cases. This group shows a broader range of distribution among eukaryotes, and contains human L1, Drosophila I factor and silkworm R1 (Fawcett et al., 1986; Hattori et al., 1986; Xiong and Eickbush, 1988). This type of LINE encodes two poorly characterized ORF proteins. The ORF1 protein has been shown to form a cytoplasmic multimeric ribonucleoprotein complex (Hohjoh and Singer, 1996; Dawson et al., 1997; Pont-Kingdon et al., 1997) and to possess nucleic acid chaperone activity (Martin and Bushman, 2001). The second ORF encodes a protein with an N-terminal APE domain (Feng et al., 1996), a central RT domain (Mathias et al., 1991) and a C-terminal cysteine–histidine motif. An in vivo retrotransposition assay using a drug resistance marker was developed for human L1 to identify several ORF amino acid residues crucial for retrotransposition (Moran et al., 1996). However, the lack of insertion site specificity in L1 has hindered further analysis of the retrotransposition mechanism.

The TRAS/SART families have structures typical of the latter subtype of LINEs (Okazaki et al., 1995; Takahashi et al., 1997). They are highly transcribed in many tissues, driven by an internal promoter in the case of TRAS1 (Takahashi and Fujiwara, 1999). They are 6–8 kb in length with two overlapping ORFs and a 3′ poly(A) tail. TRAS1 and SART1 are 29.3% identical in the amino acid sequence of the RT domain. Although their gene organization is similar to that of human L1, TRAS1 and SART1 are unique in that they insert at specific nucleotide positions into the telomeric repeats, (TTAGG)n, of the silkworm, Bombyx mori (Okazaki et al., 1993; Sasaki and Fujiwara, 2000). The TRAS/SART families therefore offer a good model system to characterize the retrotransposition of the latter subtype of LINEs such as L1.

In this paper, we develop a novel assay to analyze in vivo LINE retrotransposition, using SART1 and TRAS1. We express the B.mori SART1 element under the control of the polyhedrin promoter from Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcNPV) in Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (Sf9) cells. Since S.frugiperda belongs to the same order, Lepidoptera, as B.mori and has the (TTAGG)n repeats at telomeres (Maeshima et al., 2001), the retrotransposition into the host cell (Sf9) chromosomal telomeric repeats is expected to occur. Using this heterologous expression system, we demonstrate by PCR that SART1 actually transposes into the telomeric repeats. The retrotransposition exhibits several features expected for SART1, such as insertion position specificity and 5′ truncation. Mutagenesis analysis shows the requirement of conserved motifs in both two ORFs for the retrotransposition. In contrast to human L1, SART1 retrotransposes by efficient trans-complementation through specific recognition of the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). We further show, using a SART1/TRAS1 chimeric element, that the APE domain exchange alters the insertion position in the manner predicted. The implications of these data for transposition mechanism, LINE and SINE evolution, and development of new gene delivery vectors will be discussed.

Results

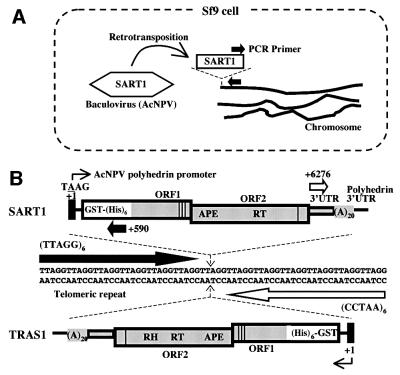

A PCR assay to detect in vivo SART1 retrotransposition

To detect in vivo SART1 retrotransposition, we expressed SART1 from AcNPV in Sf9 cells and monitored, using PCR, whether the silkworm SART1 transposed into the Sf9 chromosomal telomeric repeats (Figure 1A). In this heterologous expression system, we placed the SART1 ORF1/ORF2/3′UTR portion under the control of the AcNPV polyhedrin promoter (Figure 1B, top). For future biochemical analysis, the SART1 ORF1 was fused C-terminal to glutathione S-transferase (GST)–X5-(His)6-X31 (X denotes the vector-derived amino acid) with the position of ORF2/3′UTR kept native relative to ORF1. The SART1 poly(A) was followed by AcNPV-derived polyhedrin 3′UTR. Therefore, the SART1 transcript contains foreign sequences at the 5′ end and possibly at the 3′ end. We confirmed by SDS–PAGE of the Sf9 total proteins that each virus expressed the putative GST–His6-SART1 ORF1 fused protein (mol. wt ∼110 kDa; data not shown).

Fig. 1. A PCR assay for in vivo SART1 retrotransposition. (A) Schematic overview of the PCR assay. The hexagon represents the SART1-expressing AcNPV, which was infected into Sf9 cells. As illustrated, SART1 is expected to retrotranspose into the telomeric repeat of the Sf9 chromosomes. Black arrows indicate primers used in PCR to detect the junction between the transposed SART1 and the telomeric repeat. (B) Detailed scheme of the assay. The Sf9 telomeric repeat, (TTAGG/CCTAA)n, is shown in the middle. The schematic structure of SART1 expressed from AcNPV is shown at the top. The ORF1/ORF2/3′UTR is shaded in gray (not proportional to scale). APE and RT denote the endonuclease and reverse transcriptase domains, respectively. Vertical lines represent cysteine–histidine motifs near the C-termini of both ORFs. Note that the ORF1 is fused in-frame with the vector-derived GST–(His)6 gene for future biochemical analysis. The black rectangle represents the polyhedrin promoter that drives transcription. The SART1 3′UTR was followed by polyhedrin 3′UTR. Nucleotide position is numbered with the transcription initiation site (A of TAAG) defined as +1. White arrows denote a pair of primers, +6276 and (CCTAA)6, which were used in the experiment shown in Figure 2 to amplify the junction between the SART1 3′ ends and the telomeric repeats. Thick black arrows indicate a pair of primers, +590 and (TTAGG)6, which were used for the 5′ junction amplification in the experiment shown in Figure 3. The structure of TRAS1 expressed from AcNPV that was assayed in the experiment shown in Figure 6 is also shown at the bottom. RH denotes the RNase H domain. As indicated by dotted arrows, SART1 and TRAS1 insert between TT and AGG nucleotides with opposite orientations to each other relative to the telomeric repeat. Note that correct insertion positions have a one base uncertainty and that target site duplications have not been determined due to the repetitive nature of the poly(A) tail and the telomeric repeat.

The recombinant SART1–AcNPV was infected into the Sf9 cells. Seven, 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection, cells were pelleted, washed and the Sf9 total genomic DNAs were extracted. The purified DNA was subject to PCR to amplify the junctions between transposed SART1 elements and the Sf9 telomeric repeats. To amplify the 3′ junction, we used the +6276 primer complementary to the SART1 3′UTR (Table I), and the (CCTAA)6 primer (Figure 1B, top and middle). For the 5′ junction, likewise, the +590 primer complementary to the GST gene coding strand and the (TTAGG)6 primer were used.

Table I. List of primers.

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| +6276 | TGCCTACCTCACGAAGAAGTTGCGGTCA |

| +590 | ATTTTGGGAACGCATCCAGGCACATTGGGT |

| +6096 | AGAAAGAGAGTGCGACCCAAACTCAGTT |

| +5616 | AAGTGTGCCCCGTCTGTCTGTC |

| TRAS1 +6022 | GTAGTTAAGTATAGCGTAAGATATAGTCAGTAAG |

| SART1 S880 | AAAAAACCATGGGCAGTTATAAAGAAGAATTACCCCAG |

| SAX 3p Not1 | AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGG |

| SART1 S5995 | AGTCACTCGTCGCGGTG |

| SART1 A6221 | AAAAAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTACGGGAGCTGAGCG |

| SART1 1H626P | CACGCACTGGGCCCCGTGAGTGCCCG |

| SART1 2H228V | GGAGACGCTCTCCGACGTCCGCTACATTGGTTTC |

| SART1 2D699V | GGTCATCTGCTACGCCGTCGACACGCTGGTGACG |

| SART1 2C1007G | GCCCTCGAAGCGGGCCCGAGGTGGG |

| TRAS1 S2395 | AAAAAACCATGGGACGCGTCCTCACTGCAA |

| TRAS1 A7870 | AATAATAATAGCGGCCGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTAAGTCACTCTTTTCTCTGC |

| SART1 A3029 | TTTTTGCGGCCGCGCTGCTGGTCATTATTCGTCGTCCATTGGTGT |

| SART1 S3668 | AAAAAAAAGATCTGGAGTCTTCTTCGGTAACGACTTTGCCCTTTG |

| TRAS1 S3848 | AAAAAAAAAAGCGGCCGCCCCCTACAGAGTTTTGCAAG |

| TRAS1 A4527 | AAAAAAAGATCTTGGAGTCTAATATTGAATACCATACCG |

Underlined letters indicate restriction sites used for subcloning. Mutagenized nucleotides are boxed.

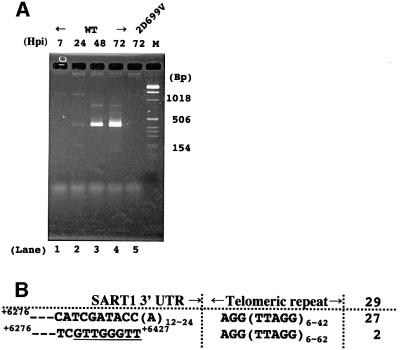

The 3′ junction between retrotransposed SART1 elements and the telomeric repeats is identical to that found in the Bombyx genome

To our surprise, after only 35 cycles of the 3′ junction PCR, we observed an intense band 24–72 h post-infection, suggesting highly efficient transposition in this system (Figure 2A). This time course accurately reflects the polyhedrin promoter expression, because the promoter is activated at 20–24 h post-infection (O’Reilly et al., 1992). The size, 400 bp, is in good accordance with that of the putative retrotransposed 3′ junction, 392 bp plus telomeric repeat length. We cloned total PCR products in lane 4 into a plasmid vector, and sequenced 29 clones (Figure 2B). All 29 clones were amplified correctly by the +6276 and (CCTAA)6 primers. Among them, 27 contained full-length 3′UTRs with poly(A) tails connected with the telomeric repeats. Importantly, the poly(A) tails of these 27 clones were directly adjoined to the AGG of the telomeric repeats, identical to the junction sequences found in the Bombyx genome (Takahashi et al., 1997). Similar results were produced in additional infection/PCR experiments. These results suggest that most of the SART1 clones arose by retrotransposition.

Fig. 2. 3′ junction analysis for retrotransposed SART1 elements. (A) A PCR amplification of the boundaries between the transposed SART1 3′ ends and the telomeric repeats. Sf9 genomic DNAs were extracted 7, 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection (Hpi) with AcNPV expressing wild-type SART1 or 2D699V. The purified DNAs were used as templates for PCR with a pair of primers, +6276 and (CCTAA)6, described in Figure 1B. The PCR products were subject to 3% agarose electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. A molecular size marker was run in the righthand lane; some of the base-pair sizes are indicated. (B) Nucleotide sequences of 29 clones from the 3′ junction PCR products shown in lane 4 of (A). The number of each type is shown on the right. Nucleotide positions are indicated with the polyhedrin transcription initiation site defined as +1. The octa nucleotide with homology to the telomeric repeat is underlined.

The other two clones, however, contained only the 5′-half 152 bp of the SART1 3′UTR. They were joined to the telomeric repeats at an octanucleotide, GTTGGGTT (underlined letters in Figure 2B). Since this octamer sequence is only one base different from the telomeric repeat, GTTAGGTT, these two SART1 clones may have arisen by recombinational events with endogenous Sf9 telomeric repeats. Transduction of 3′ flanking sequences was not observed, which has often been found for human L1 (Moran et al., 1999).

As a negative control, the Sf9 cells were infected with the SART1 2D699V–AcNPV, a mutant of the putative SART1 reverse transcriptase C motif, YADD, which is essential for catalytic activity. In this mutant, the aspartic acid residue at the ORF2 amino acid position 699 was substituted to a valine residue (see Figure 4A). The PCR assay for this mutant never detected retrotransposition (Figure 2A, lane 5). This result indicates that the transposition we detected was not mediated by endogenous Sf9 SART-like elements, but by authentic retrotransposition of the B.mori SART1 by its own RT activity.

Fig. 4. Requirement of the ORFs and 3′UTR for SART1 retrotransposition. (A) Schematic explanation of various mutant SART1–AcNPVs. The amino acid position of each missense mutant is shown (named so that, in the 1H626P mutant, for example, the histidine residue at the 626th amino acid position in ORF1 is substituted to proline). This position corresponds to the first histidine residue of the three continuous CCHC motifs in ORF1. The first methionine of the SART1 ORF1 is defined as the first, whereas in the case of ORF2 the amino acid residues preceding the first methionine in the overlapping ORF region are also counted in the number. The mutant that lacks the entire the 3′UTR and poly(A) sequence but still contains the following polyhedrin 3′UTR is denoted as Δ3′. The pair of primers, +6096 and (CCTAA)6, used for 3′ junction amplification are depicted as white arrows. (B) The 3′ junction PCR assay from the Sf9 cells infected with a single AcNPV containing the wild-type/mutant SART1 elements (lane 1–7) or co-infected simultaneously with two kinds of mutant SART1–AcNPVs (lane 8–14). The PCR products were subject to 2% agarose electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. A molecular size marker was run in the lefthand lane.

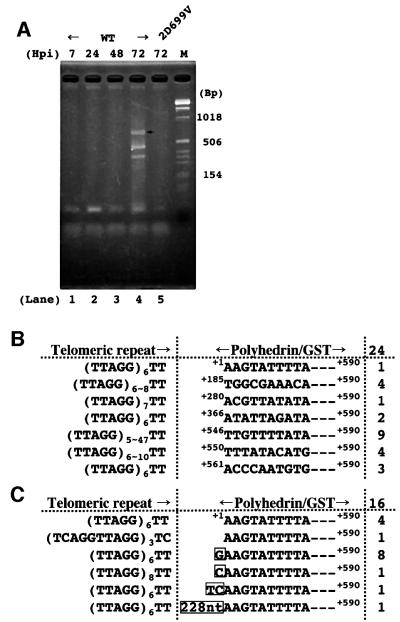

SART1 retrotransposes with frequent 5′ truncation and aberration

The amplification of the 5′ junction through 40 cycles of PCR gave rise to visible bands 72 h post-infection (Figure 3A). In striking contrast to the 3′ junction, several bands appeared. The size of the largest band (arrow in lane 4), ∼600 bp, was in good accordance with the putative full-length 5′ transposed product length, 590 bp plus the telomeric repeat (Figure 1B). We therefore suspected that this band represents full-length retrotransposition and that smaller bands are 5′ truncations arising from abortive reverse transcription. Cloning and subsequent sequencing of the whole PCR products in lane 4 confirmed our prediction (Figure 3B). All 24 clones sequenced were amplified by the (TTAGG)6 and +590 primers. All the clones were connected 3′ to the TT of (TTAGG)n, which is the same insertion position as in the Bombyx genome. In the largest clone, the telomeric repeat was adjoined precisely with the polyhedrin RNA 5′ end sequence, AAG (Figure 1B; Possee and Howard, 1987). This result strongly implies that the recombinant SART1 transposed through RNA. All the other 23 clones turned out to be variably 5′ truncated SART1 elements connected with the telomeric repeats. None of the 5′ bands was detected from the cells infected with SART1 2D699V–AcNPV (Figure 3A, lane 5).

Fig. 3. 5′ junction analysis for retrotransposed SART1 elements. (A) A PCR amplification of the boundaries between the transposed SART1 5′ ends and the telomeric repeats. The AcNPV-infected Sf9 genomic DNAs were amplified with a pair of primers, +590 and (TTAGG)6, depicted in Figure 1B. The PCR products were subject to 3% agarose electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. A molecular size marker was run in the righthand lane; some of the base-pair sizes are indicated. (B) SART1 retrotransposes with frequent 5′ truncation. Nucleotide sequences of 24 clones from the whole 5′ junction PCR products in lane 4 of (A) are shown. The number of each type is shown on the right. Nucleotide positions are indicated with the polyhedrin transcription initiation site defined as +1. (C) SART1 retrotransposes with 5′ aberration. The full-length 5′ junction PCR product that is indicated by an arrow in lane 4 of (A) was purified and cloned, and 16 clones were sequenced. Boxed nucleotides are not part of either the recombinant SART1 or the telomeric repeats.

In the Bombyx genome, we have previously found examples of duplication and aberration at the SART1 DNA 5′ ends (see figure 4 in Takahashi et al., 1997). To examine whether similar aberrant 5′ sequences were observed, we characterized the full-length retrotransposition products by extracting the largest band in lane 4 of Figure 3A (indicated by an arrow). Subcloning and sequencing of the 16 clones showed that the polyhedrin RNA 5′ end sequence, AAG, was directly joined to TT of the telomeric repeats in four clones, representing the canonical full-length retrotransposition (Figure 3C). In another clone, SART1 retrotransposed into 10mer repeats, (TCAGGTTAGG)n, which is only one nucleotide different from the telomeric repeat unit. Of the other 10 clones, eight had an extra G between the recombinant SART1 elements and the telomeric repeats. There was one case each of an extra C or TC. The G may arise commonly as a result of reverse transcription of the 5′ G cap (Hirzmann et al., 1993; Volloch et al., 1995). Alternatively, these added nucleotides may represent terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase activity of the SART1 RT. In the other clone, a 228 bp unknown sequence was added, which is difficult to explain. Although these variations were somewhat different from those found in the Bombyx genome, the existence of the 5′ truncation and aberration also supports the authentic retrotransposition of SART1 in this system.

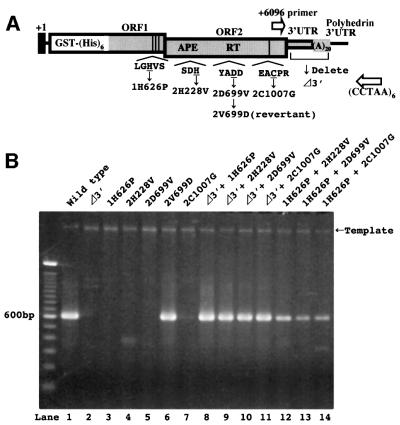

SART1 retrotransposition requires the 3′UTR and conserved motifs in both ORFs

SART1 is a typical LINE with two ORFs. ORF1 contains three C-terminal cysteine–histidine motifs, and ORF2 comprises an APE, a RT domain and one C-terminal cysteine–histidine motif (Figure 1B). To examine whether these conserved motifs are crucial for SART1 to retrotranspose in vivo, we generated a series of SART1–AcNPV constructs containing missense mutations at these conserved motifs, and assayed to determine whether these elements could transpose into the telomeric repeats (Figure 4A). We also made a SART1 Δ3′–AcNPV construct, which lacks the entire SART1 3′UTR but retains a downstream polyhedrin 3′UTR. For these elements, we conducted a 3′ junction PCR assay using the (CCTAA)6 and +6096 primers complementary to the SART1 ORF2 (Table I).

As shown in Figure 4B, none of these mutants could retrotranspose in vivo (lanes 2–5 and 7). This result indicates that the APE/RT domain plus the cysteine– histidine motif in the ORF2 is indispensable for in vivo SART1 retrotransposition, as was shown for human L1 (Moran et al., 1996). Disruption of the ORF1 cysteine– histidine motifs also abolished the retrotransposition. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that the LINE ORF1 cysteine–histidine motifs, which are widely conserved from many (but not all) LINEs to retroviruses, are crucial for retrotransposition. The SART1 retrotransposition also required the 3′UTR, suggesting that the sequence-specific recognition of the RNA 3′ end by the ORF proteins is essential for SART1 to retrotranspose. It should be noted that the SART1 5′UTR, which was replaced by the polyhedrin 5′UTR in the construct, is dispensable for retrotransposition.

These mutant SART1–AcNPVs were constructed by a two-step procedure: plasmid mutagenesis and virus generation. Although we confirmed that each mutant expressed a comparable amount of the putative SART1 ORF1 protein (data not shown), the mutant SART1 elements may have failed to retrotranspose because undesired deleterious mutations were introduced into other amino acid positions during the two steps. To exclude this possibility, we conducted two control experiments. First, as a control for plasmid mutagenesis, we re-mutated the valine residue in 2D699V–AcGHLTB to an aspartic acid (Figure 4A, 2V699D). The resulting plasmid should have the identical nucleotide sequence as wild-type SART1. The AcNPV made from this plasmid restored the wild-type level of retrotransposition (Figure 4B, lane 6), indicating that the retrotransposition deficiency in the 2D699V mutant is not due to any possible undesired mutations during plasmid mutagenesis.

As another control, we simultaneously infected two of these mutant viruses and assayed to determine whether retrotransposition occurred. If these mutants do not have mutations other than those we introduced, the two infected mutants might supply the ORF proteins and the RNAs to each other, resulting in retrotransposition by trans-complementation. As anticipated, the co-infections enabled SART1 retrotransposition to occur (Figure 4B, lanes 8–14). Approximately wild-type levels of signals were detected from the Δ3′ mutant co-infected with each of the ORF mutants (Figure 4B, lanes 8–11). This result suggests that the Δ3′ mutant still expresses functional ORF proteins that could act efficiently on the RNA 3′ end derived from each ORF mutant. Similarly, a somewhat reduced level of retrotransposition was observed in the ORF1 mutant, 1H626P, co-infected with each of the ORF2 mutants (Figure 4B, lanes 12–14), suggesting that 1H626P correctly produced the functional ORF2 protein, which accomplishes retrotransposition by trans-complementation with the ORF1 protein supplied from each ORF2 mutant. These analyses suggest that the retrotransposition deficiency seen in each mutant was not caused by experimental errors during the mutant AcNPV construction, but by the effect of the mutations we introduced.

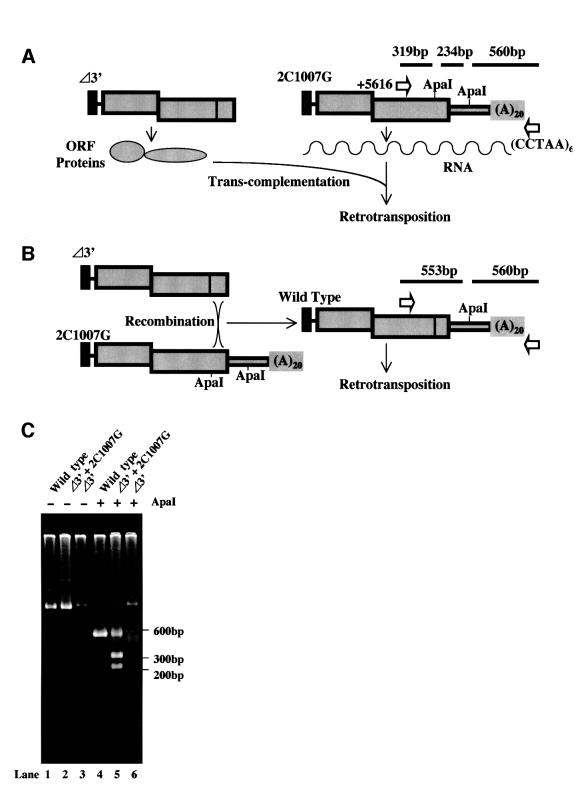

SART1 can retrotranspose by trans-complementation

The results presented above suggest that SART1 can retrotranspose by delivering its encoded proteins in trans to other SART1 RNA/protein molecules. There remains a less likely possibility, however, that the retrotransposition was subsequently caused by the wild-type SART1 element that had been generated through recombination between two mutant DNAs. To rule out this possibility, we characterized a 3′ PCR product derived from the co-infection of the Δ3′ and 2C1007G mutant (Figure 4B, lane 11). The size of the product suggests that only the wild-type length and not the Δ3′ element transposed. Upon the SART1 2C1007G–pAcGHLTB construction by plasmid mutagenesis, we introduced an ApaI restriction site in the 2C1007G mutant. If retrotransposition occurred through reverse transcription of the 2C1007G RNA by trans-complementation, the transposed DNA 3′ end should have an additional ApaI site at the mutagenized position in addition to one in the 3′UTR (Figure 5A). On the other hand, if the retrotransposition was subsequently caused by the wild-type SART1 generated by homologous recombination, the retrotransposed DNA product would have only one ApaI site in the 3′UTR (Figure 5B). We conducted a 3′ junction PCR using the (CCTAA)6 and +5616 primer complementary to ORF2 (Figure 5C). A 1.1 kb band was detected from the Sf9 cells infected with the wild-type SART1 (Figure 5C, lane 1) or with both of the two mutants simultaneously (Figure 5C, lane 2). ApaI digestion of the wild-type PCR product gave rise to two ∼550 bp bands (Figure 5C, lane 4), whereas digestion of the PCR product from double infection mutants gave three bands, as expected from trans-complementation (Figure 5C, lane 5). The amplification from cells infected solely with Δ3′ did not produce the band that could be digested with ApaI (Figure 5C, lanes 3 and 6). These experiments suggest that the SART1 retrotransposition observed with co-infection of two mutants is not due to re-generation of a wild-type SART1 by DNA recombination, but to trans-complementation between the two mutant SART1 elements. The lack of a 3′ deleted product suggests that the Δ3′ mutant deletes a critical cis element required for transposition.

Fig. 5. Co-infected SART1 mutants, Δ3′ and C1007G, retrotranspose by trans-complementation. (A) The trans-complementation mechanism, in which the ORF proteins derived from Δ3′ act on C1007G SART1 RNA, gives rise to the retrotransposed C1007G DNA. (B) Alternative possibility that DNA recombination near the ORF2 C-terminus between the two mutants generates wild-type SART1, which could subsequently retrotranspose. In (A) and (B), schematic structures of Δ3′ and C1007G are shown. Note that 2C1007G lacks the cysteine–histidine motif (indicated by a vertical line in the wild type and Δ3′), instead containing an additional ApaI site, near the ORF2 C-terminus. The primers, +5616 and (CCTAA)6, used for 3′ junction PCR are depicted as white arrows. The theoretical ApaI digestion fragments from the PCR products are shown as horizontal lines above the primers. (C) 3′ junction PCR products uncut (lanes 1–3) or cut with ApaI (lanes 4–6). Molecular sizes are shown on the right.

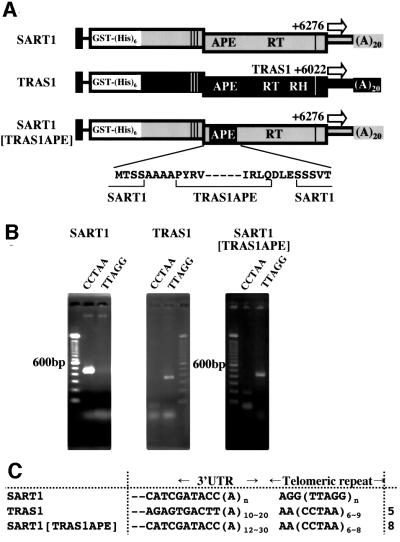

Exchange of the APE domain between TRAS1 and SART1 alters the insertion site specificity

A critical step in LINE retrotransposition is the nicking of target site DNAs, which are thought to serve as primers for reverse transcription. Because the APE protein expressed in bacteria cleaves the oligonucleotides containing the target site sequences in vitro (Feng et al., 1996), this domain is thought to be responsible for the target cleavage. However, this proposed function of the APE domain has not been proved in the context of in vivo retrotransposition, although this domain was vital for in vivo retrotransposition (Feng et al., 1996). To this end, we developed a novel approach using our system. TRAS1 is another retrotransposon, which inserts at a specific nucleotide position with the opposite orientation to SART1 relative to the telomeric repeats (Figure 1B; Okazaki et al., 1995). Taking advantage of the insertion sequence difference of these two elements, we constructed a chimeric SART1–TRAS1 APE element, in which the SART1 APE domain was replaced by TRAS1 APE and with the other SART1 portions kept native (Figure 6A). If the TRAS1 APE domain determines the target site of this chimeric retrotransposon, this element would insert at the same nucleotide position as TRAS1 but not as SART1 within the telomeric repeats.

Fig. 6. Target site alteration in a SART1/TRAS1 chimeric retrotransposon. (A) Schematic structures of SART1, TRAS1 and the SART1 with its APE replaced by TRAS1 APE. The portions derived from SART1 and TRAS1 are depicted in gray and black, respectively. RH indicates the TRAS1 RNase H domain. White arrows represent the +6276 (for SART1 and the chimeric element) and TRAS1 +6022 primers, which are used in combination with (CCTAA)6 or (TTAGG)6. The deduced amino acid sequence for the N- and C-terminal boundaries of the APE domain is presented below. AAAA and DLE are derived from the linkers used for plasmid construction. The boundaries of the APE domain are based on a previous phylogenetic study (Malik et al., 1999). (B) Orientation-specific amplification of the 3′ junctions of the three retrotransposons. The (CCTAA)6 and (TTAGG)6 primers used for PCR are denoted as CCTAA and TTAGG. (C) Nucleotide sequences of the 3′ junction PCR products in (B). Note that the 3′ junction sequences for SART1 are described in Figure 2B. The numbers of the clones are shown on the right.

First, we examined whether SART1 inserts in the telomeric repeats in a specific orientation relative to the telomeric repeats. We conducted a 3′ PCR assay using the +6276 primer, in combination with either the (TTAGG)6 or (CCTAA)6 primer (Figure 6B). As expected from the insertion orientation of SART1, a band was detected with the (CCTAA)6 but not with the (TTAGG)6 primer.

Next, we investigated whether TRAS1 can also retrotranspose in vivo and whether the TRAS1 insertion exhibits the opposite orientation specificity to SART1. We cloned the TRAS1 ORF1/ORF2/3′UTR portion downstream the polyhedrin promoter in the pAcGHLTB plasmid and generated an AcNPV expressing TRAS1 (Figure 1B, bottom). We carried out a 3′ PCR assay using the TRAS1 +6022 primer complementary to its 3′ UTR, in combination with each of the (TTAGG)6 and (CCTAA)6 primers (Figure 6B). In contrast to SART1, the band was detected with (TTAGG)6 but not with (CCTAA)6. This band was cloned and sequenced (Figure 6C). In all five clones, the 3′ end of TRAS1 was neighbored by the telomeric repeats with the poly(A) tails adjacent 5′ to the AA of (CCTAA)n. This insertion position is identical to that seen in the Bombyx genome. The retrotransposition was abolished when conserved amino acid residues were mutated (M.Osanai, H.Takahashi and H.Fujiwara, unpublished data). Therefore, TRAS1 is also retrotransposition competent and has the opposite insertion orientation specificity to SART1.

We then constructed the chimeric SART1–TRAS1 APE element, which was assayed with the 3′ PCR using the +6276 primer complementary to the SART1 3′UTR, in combination with each of the telomeric repeat primers. As shown in Figure 6B, this element showed the same insertion orientation as TRAS1 but opposite to SART1. Cloning and subsequent sequencing of the PCR product demonstrated that, in all eight clones sequenced, this element inserted at the exact same nucleotide position as TRAS1 (Figure 6C). This result provided in vivo evidence that the APE domain is the primary determinant for target site selection in LINE retrotransposition. This result also suggests that it is not the APE domain which recognizes the 3′UTR during transposition, as this is different in SART1 and TRAS1.

Discussion

In vivo retrotransposition assay

We demonstrated that both SART1 and TRAS1 are capable of retrotransposition in vivo. In vivo retrotransposition has been shown previously for some LINEs based on splicing out of artificial introns (Evans and Palmiter, 1991; Jensen and Heidmann, 1991; Pelisson et al., 1991; Kinsey, 1993). These experiments were, however, unable to identify amino acid residues crucial for retrotransposition. The human L1 marker selection assay succeeded in solving this problem (Moran et al., 1996). In this paper, we developed a novel assay to characterize in vivo LINE transposition, taking advantage of the insertion site specificity of SART1 and TRAS1. RNA-mediated transposition was strongly suggested by evidence that the transposed SART1 DNA contained exactly the RNA transcription unit. Our assay is convenient and directly linked to the retrotransposition reaction, because the retrotransposition can be detected by PCR within a few days and because the ORF domain exchange between SART1 and TRAS1 can clarify the domain functions. The retrotransposition events we detected in Sf9 cells are relevant to those seen in B.mori, in that the retrotransposition occurred at the same nucleotide position as seen in the silkworm genome (Okazaki et al., 1995; Takahashi et al., 1997) and the retrotransposition required conserved motifs in both ORFs.

The transposition mechanism of LINEs

In vitro biochemical analysis of the R2 element suggests that non-LTR retrotransposons transpose by the TPRT mechanism (Luan et al., 1993). Our assay provided several lines of in vivo evidence in favor of this model. First, we detected frequent 5′ truncation and aberration in the SART1 retrotransposition, while no such change was observed for the 3′ junction. Secondly, the SART1 retrotransposition required the 3′UTR but not the 5′UTR, suggesting that the recognition of the RNA 3′ end by the ORF proteins is crucial for retrotransposition, consistent with the in vitro experiment with R2 (Luan and Eickbush, 1995). Thirdly, the exchange of the APE domain altered the insertion site, suggesting that the primer for LINE reverse transcription is the target DNA, which was cleaved by the APE domain. Together with observations that the APE proteins cleave both of the target DNA strands in the order that is consistent with the TPRT model (Feng et al., 1998; Anzai et al., 2001), our experiments suggest that evolutionarily new LINEs such as SART1 and L1 also transpose by TPRT, as does R2. This idea is consistent with the fact that group II introns and telomerases, which are the most closely related to LINEs, also use the TPRT mechanism (Zimmerly et al., 1995; Blackburn, 1998).

Target site selection

Exchange of the APE domain alters the insertion site in the predicted way. This result argues that the primary determinant of LINE target site selection is the APE domain in vivo, as suggested by in vitro analysis (Feng et al., 1996). However, it remains uncertain whether DNA recognition by the APE domain can solely account for the target site selection in LINE retrotransposition. In fact, APE cleavage specificity appears insufficient to assure site-specific retrotransposition within the host genomes (Feng et al., 1998; Christensen et al., 2000; Anzai et al., 2001). Given that there are many poorly characterized domains such as zinc-finger motifs in LINE ORFs, it is not known whether the APE domain is fully responsible for target site specificity. If one takes into account that the genomic DNA is assembled as chromatin with many associated factors in vivo, other domains might be involved in target site selection through interaction with host chromatin proteins, as has been proved for some LTR retrotransposons (Kirchner et al., 1995; Xie et al., 2001) and as has been suggested for human L1 (Cost et al., 2001). For example, the TRAS1 ORF2 encodes a region that has weak homology with Myb-domain, which is found in many telomere-binding proteins midway between the APE and RT domain (Kubo et al., 2001). It might be that another domain such as this putative Myb domain assures the ‘telomere specificity’ by recognizing the telosomes, and then APE cleavage determines the insertion position. Mutagenesis and exchange experiments of other domains in the ORFs may give a clue to the answer to this question.

Survival mechanism of LINEs

As for human L1, only ∼0.05% of the 100 000 genomic copies are estimated to be capable of retrotransposition (Sassaman et al., 1997). L1 seems to have a survival mechanism termed cis preference, by which only the active copies with functional ORFs continue to retrotranspose. L1 ORF proteins are hypothesized to bind immediately to the RNA molecules that encode themselves, whereby only the unmutated L1 RNAs are maintained to retrotranspose (Boeke, 1997; Wei et al., 2001). Our analysis suggests, however, that the SART1 ORF proteins can effectively act on other SART1 molecules that do not encode active proteins. It should be noted that this result may be partly due to high protein concentration under baculoviral expression conditions. As for SART1, most Bombyx genomic copies are strongly conserved in sequence, with the few 5′ truncated copies probably formed by unequal crossovers within the telomeric regions (Takahashi et al., 1997), although SART1 retrotransposition in Sf9 cells was shown here to produce many 5′ truncated copies. Given the possibility of a recombinational mechanism to select for active copies, SART1 may not need a cis preference mechanism for survival in contrast to human L1. SART1 may bind to the RNA 3′ end with sequence-specific recognition as efficiently in trans as in cis.

Implication for SINE evolution

The LINE transposition machinery is thought to be responsible for retroposition of SINEs. This hypothesis is based on the facts that many SINEs and LINEs share the same RNA 3′ end sequences (Ohshima et al., 1996), that the R2 non-LTR retrotransposon specifically recognize its RNA 3′ end (Luan and Eickbush, 1995) and on other evidence (Jurka, 1997). However, human L1 does not depend on the RNA 3′ end sequence and frequently transduces the 3′ flanking genomic sequences by retrotransposition (Moran et al., 1996, 1999). This feature may have resulted in the dominance in the human genome of Alus and processed pseudogenes, which share only the poly(A) tail with L1 (Esnault et al., 2000). To better understand the functional basis of the transposition mechanism of SINEs and processed pseudogenes, we examined whether another LINE, SART1, depends on its RNA 3′ end. Our assay showed that the SART1 retrotransposition did depend on the 3′ end sequence and that no transduction of 3′ flanking sequences was found. It is highly unlikely that SART1 recognizes only the poly (A) RNA tail. If only the poly(A) tail were recognized, the SART1 Δ3′ construct that retains the polyhedrin 3′UTR would have retrotransposed. These lines of evidence support the hypothesis that there are two kinds of LINE, of which one recognizes the specific 3′UTR sequence and the other does not (Okada et al., 1997). In spite of the structural similarity to L1, SART1 is more similar to R2 in this respect. This result provides circumstantial evidence that LINE transposition machinery is responsible for SINE retroposition through the specific recognition of the common RNA 3′ end in most eukaryotic genomes.

Potential application for gene delivery vectors

In the 21st century, gene therapy is expected to provide a means to cure genetic diseases. This necessitates stable human expression vectors. At present, most gene delivery vectors are derived from retroviruses. These vectors have a problem in that they integrate randomly into the genomes, by which process essential genes may be disrupted. It is therefore important to develop a gene delivery vector that inserts into a specific location in the genome. To this end, mobile group II introns have been engineered to insert into specific sequences (Guo et al., 2000). Because these introns are derived from bacteria, however, it is questionable whether they can be successfully expressed and retrotransposed into the genome in living humans. On the other hand, LINEs have stably resided in animal genomes. LINEs are therefore good candidates for mammalian transformation vectors. In fact, human L1 can retrotranspose in mouse cells (Moran et al., 1996). Based on the result from the chimeric SART1/TRAS1, we propose that mammalian LINEs could be engineered to have target site specificity through the exchange of the APE domain borrowed from site-specific LINEs. Moreover, the incorporation of the SART1 3′UTR would have an advantage in that trans-complementation might allow separation of the ORFs from the sequences to be retrotransposed. It may be possible to develop these modified LINEs as harmless gene delivery vectors, which deliver only the genes of interest but not retrotransposons themselves to specific genomic locations, whereby harmful retrotransposition into essential genes can be avoided and stable protein expression can be achieved. One such safe genomic location may be the subtelomeric region.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The SART1 ORF1/ORF2/3′UTR portion was amplified by PCR from the genomic library clone, BS103 (Takahashi et al., 1997) with a pair of primers, SART1 S880 and SAX 3p NotI (Table I). PCR was conducted for 30 cycles using the Pfu Turbo™ DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR product was subcloned between the NcoI and NotI sites of the pAcGHLTB plasmid (PharMingen). The resulting plasmid, named SART1WT-pAcGHLTB, contained the 64 bp polyhedrin 5′UTR and the GST–X5-(His)6-X31 coding gene fused in-frame with MGSYKE of the SART1 ORF1 (note that serine is at the underlined position in the native SART1 ORF1), followed by the SART1 ORF2/3′UTR, and the polyhedrin 3′UTR. Point mutations were introduced into SART1WT-pAcGHLTB with four pairs of primers listed in Table I using the QuikChange™ Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). The SART1 Δ3′-pAcGHLTB plasmid was constructed from SART1WT-pAcGHLTB by digestion with AflII and NotI, between which sites was ligated the 200 bp ORF2 3′ end sequence that had been amplified by PCR with the primers SART1 S5995 and SART1 A6221. We confirmed the mutation of each plasmid by DNA sequencing. TRAS1WT-pAcGHLTB was constructed by cloning the TRAS1 ORF1/ORF2/3′UTR portion, which had been amplified from the genomic library clone, λB1 (Okazaki et al., 1995) with TRAS1 S2395 and TRAS1 A7870, into the NcoI and NotI site. SART1-pAcGHLTB containing TRAS1 APE was constructed as follows. First, the NotI and BglII sites of the SART1WT-pAcGHLTB were removed by NotI–BglII digestion, T4 DNA polymerase treatment and self-ligation. Secondly, all but the APE domain of SART1WT-pAcGHLTB was amplified by inverse PCR with the 5′-phospholylated primers SART1 A3029 and SART1 S3668. The amplified product was self-ligated and cloned. This construct, SART1 ΔAPE-pAcGHLTB, lacks the APE domain but instead contains a NotI and a BglII site derived from the two primers. Thirdly, the TRAS1 APE domain was amplified with TRAS1 S3848 and TRAS1 A4527, and cloned between the NotI and BglII sites of SART1 ΔAPE-pAcGHLTB.

Recombinant AcNPV generation

Sf9 cells were propagated as monolayer cultures at 27°C in TC-100 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Nihon-nosankougyou) in the presence of penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco-BRL). The recombinant baculovirus containing the wild-type/mutant SART1 ORF1/ORF2/3′UTR portion driven by the polyhedrin promoter was produced by co-transfection of the wild-type/mutant SART1-pAcGHLTB plasmid with the BaculoGold™ DNA (PharMingen) into the Sf9 cells using the Tfx-20 lipofection reagent (Promega). Four days later, the medium was collected and used for plaque purification and subsequent virus propagation, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PharMingen).

In vivo retrotransposition assay by PCR

Approximately 1 × 106 of Sf9 cells were infected in a 6-well plate with a SART1-containing AcNPV at a multiplicity of infection of 10 plaque forming units (pfu) per cell. As for the co-infection experiments, cells were infected with two AcNPVs at 5 pfu/cell. At various times post-infection, cells were scraped, pelleted at 1000 g for 5 min, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C, and the total genomic DNAs were purified with a standard method using proteinase K and SDS (Ausubel et al., 1994). The PCR assays were conducted with LA-Taq (Takara) in the presence of TaqStart Antibody (Clontech) using ∼10 ng of Sf9 DNA. The reaction mixture was denatured at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles (for the SART1 3′ junction) or 40 cycles (for the SART1 5′ junction, TRAS1 3′ junction and SART1/TRAS1 APE 3′ junction) of 98°C 20 s, 62°C 30 s, 72°C 1 min. Ten microliters from each mixture was subject to 2 or 3% agarose electrophoresis in TBE buffer and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. PCR products were cloned into the pGemT-easy vector (Promega) directly or after being excised using RECOCHIP (Takara) from the agarose gel. The cloned products were sequenced using Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an automatic DNA sequencer, ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer. Sequence analysis was carried out using DNASIS-Mac v. 3.7 (Hitachi).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to J.Boeke and M.Osanai for critically reading the manuscript. We thank K.Wakabayashi and K.Ishiguro for advice regarding baculoviral expression. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (MESCJ), and Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for Young Scientists.

References

- Anzai T., Takahashi,H. and Fujiwara,H. (2001) Sequence-specific recognition and cleavage of telomeric repeat (TTAGG)n by endonuclease of non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon TRAS1. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F.M., Brent,R., Kingston,R.E., Moore,D.D., Seidmen,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (1994) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene Publishing Associates/John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

- Blackburn E.H. (1998) Telomerase. In Gesteland,R.F., Cech,T.R. and Atkins,J.F. (eds), The RNA World, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 609–635.

- Boeke J.D. (1997) LINEs and Alus–the polyA connection. Nature Genet., 16, 6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke J.D. and Stoye,J.P. (1997) Retrotransposons, endogenous retroviruses, and the evolution of retroelements. In Coffin,J.M., Hughes,S.H. and Varmus,H.E. (eds), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 343–435. [PubMed]

- Christensen S., Pont-Kingdon,G. and Carroll,D. (2000) Target specificity of the endonuclease from the Xenopus laevis non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon, Tx1L. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 1219–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost G.J,. Golding,A., Schlissel,M.S. and Boeke,J.D. (2001) Target DNA chromatinization modulates nicking by L1 endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 573–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A., Hartswood,E., Paterson,T. and Finnegan,D.J. (1997) A LINE-like transposable element in Drosophila, the I factor, encodes a protein with properties similar to those of retroviral nucleocapsids. EMBO J., 16, 4448–4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault C., Maestre,J. and Heidmann,T. (2000) Human LINE retrotransposons generate processed pseudogenes. Nature Genet., 24, 363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.P. and Palmiter,R.D. (1991) Retrotransposition of a mouse L1 element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 8792–8795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett D.H., Lister,C.K., Kellett,E. and Finnegan,D.J. (1986) Transposable elements controlling I–R hybrid dysgenesis in D. melanogaster are similar to mammalian LINEs. Cell, 47, 1007–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q., Moran,J.V., Kazazian,H.H.,Jr and Boeke,J.D. (1996) Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell, 87, 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q., Schumann,G. and Boeke,J.D. (1998) Retrotransposon R1Bm endonuclease cleaves the target sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 2083–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Karberg,M., Long,M., Jones,J.P.,III, Sullenger,B. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2000) Group II introns designed to insert into therapeutically relevant DNA target sites in human cells. Science, 289, 452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M., Kuhara,S., Takenaka,O. and Sakaki,Y. (1986) L1 family of repetitive DNA sequences in primates may be derived from a sequence encoding a reverse transcriptase-related protein. Nature, 321, 625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirzmann J., Luo,D., Hahnen,J. and Hobom,G. (1993) Determination of messenger RNA 5′-ends by reverse transcription of the cap structure. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 3597–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohjoh H. and Singer,M.F. (1996) Cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes containing human LINE-1 protein and RNA. EMBO J., 15, 630–639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S. and Heidmann,T. (1991) An indicator gene for detection of germline retrotransposition in transgenic Drosophila demonstrates RNA-mediated transposition of the LINE I element. EMBO J., 10, 1927–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. (1997) Sequence patterns indicate an enzymatic involvement in integration of mammalian retroposons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 1872–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian H.H. Jr, Wong,C., Youssoufian,H., Scott,A.F., Phillips,D.G. and Antonarakis,S.E. (1988) Haemophilia A resulting from de novo insertion of L1 sequences represents a novel mechanism for mutation in man. Nature, 332, 164–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey J.A. (1993) Transnuclear retrotransposition of the Tad element of Neurospora. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 9384–9387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner J., Connolly,C.M. and Sandmeyer,S.B. (1995) Requirement of RNA polymerase III transcription factors for in vitro position-specific integration of a retroviruslike element. Science, 267, 1488–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y., Okazaki,S., Anzai,T. and Fujiwara,H. (2001) Structural and phylogenetic analysis of TRAS, telomeric repeat-specific non-LTR retrotransposon families in Lepidopteran insects. Mol. Biol. Evol., 18, 848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E.S. et al. (2001) Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature, 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan D.D. and Eickbush,T.H. (1995) RNA template requirements for target DNA-primed reverse transcription by the R2 retrotransposable element. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 3882–3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan D.D., Korman,M.H., Jakubczak,J.L. and Eickbush,T.H. (1993) Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell, 72, 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima K., Janssen,S. and Laemmli,U.K. (2001) Specific targeting of insect and vertebrate telomeres with pyrrole and imidazole polyamides. EMBO J., 20, 3218–3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik H.S., Burke,W.D. and Eickbush,T.H. (1999) The age and evolution of non-LTR retrotransposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol., 6, 793–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S.L. and Bushman,F.D. (2001) Nucleic acid chaperone activity of the ORF1 protein from the mouse LINE-1 retrotransposon. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias S.L., Scott,A.F., Kazazian,H.H.,Jr, Boeke,J.D. and Gabriel,A. (1991) Reverse transcriptase encoded by a human transposable element. Science, 254, 1808–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran J.V., Holmes,S.E., Naas,T.P., DeBerardinis,R.J., Boeke,J.D. and Kazazian,H.H.,Jr (1996) High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell, 87, 917–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran J.V., DeBerardinis,R.J. and Kazazian,H.H.,Jr (1999) Exon shuffling by L1 retrotransposition. Science, 283, 1530–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima K., Hamada,M., Terai,Y. and Okada,N. (1996) The 3′ ends of tRNA-derived short interspersed repetitive elements are derived from the 3′ ends of long interspersed repetitive elements. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3756–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada N., Hamada,M., Ogiwara,I. and Ohshima,K. (1997) SINEs and LINEs share common 3′ sequences: a review. Gene, 205, 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki S., Tsuchida,K., Maekawa,H., Ishikawa,H. and Fujiwara,H. (1993) Identification of a pentanucleotide telomeric sequence, (TTAGG)n, in the silkworm Bombyx mori and in other insects. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 1424–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki S., Ishikawa,H. and Fujiwara,H. (1995) Structural analysis of TRAS1, a novel family of telomeric repeat-associated retrotransposons in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 4545–4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly D.R., Miller,L.K. and Luckow,V.A. (1992) Baculoviral Expression Vectors: A Laboratory Manual. W.H. Freeman and Co., New York, NY.

- Pelisson A., Finnegan,D.J. and Bucheton,A. (1991) Evidence for retrotransposition of the I factor, a LINE element of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 4907–4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pont-Kingdon G., Chi,E., Christensen,S. and Carroll,D. (1997) Ribonucleoprotein formation by the ORF1 protein of the non-LTR retrotransposon Tx1L in Xenopus oocytes. Nucleic Acids Res., 5, 3088–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possee R.D. and Howard,S.C. (1987) Analysis of the polyhedrin gene promoter of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 10233–10248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T. and Fujiwara,H. (2000) Detection and distribution patterns of telomerase activity in insects. Eur. J. Biochem., 267, 3025–3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassaman D.M., Dombroski,B.A., Moran,J.V., Kimberland,M.L., Naas,T.P., DeBerardinis,R.J., Gabriel,A., Swergold,G.D. and Kazazian,H.H.,Jr (1997) Many human L1 elements are capable of retrotransposition. Nature Genet., 16, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A.F. (1999) Interspersed repeats and other mementos of transposable elements in mammalian genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 6, 657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H. and Fujiwara,H. (1999) Transcription analysis of the telomeric repeat-specific retrotransposons TRAS1 and SART1 of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2015–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Okazaki,S. and Fujiwara,H. (1997) A new family of site-specific retrotransposons, SART1, is inserted into telomeric repeats of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 1578–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volloch V.Z., Schweitzer,B. and Rits,S. (1995) Transcription of the 5′-terminal cap nucleotide by RNA-dependent DNA polymerase: possible involvement in retroviral reverse transcription. DNA Cell Biol., 14, 991–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Gilbert,N., Ooi,S.L., Lawler,J.F., Ostertag,E.M., Kazazian,H.H.,Jr, Boeke,J.D. and Moran,J.V. (2001) Human L1 retrotransposition: cis preference versus trans complementation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 1429–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A.M., Deininger,P.L. and Efstratiadis,A. (1986) Nonviral retroposons: genes, pseudogenes, and transposable elements generated by the reverse flow of genetic information. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 55, 631–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Gai,X., Zhu,Y., Zappulla,D.C., Sternglanz,R. and Voytas,D.F. (2001) Targeting of the yeast Ty5 retrotransposon to silent chromatin is mediated by interactions between integrase and Sir4p. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6606–6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. and Eickbush,T.H. (1988) The site-specific ribosomal DNA insertion element R1Bm belongs to a class of non-long-terminal-repeat retrotransposons. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerly S., Guo,H., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1995) Group II intron mobility occurs by target DNA-primed reverse transcription. Cell, 82, 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]