Abstract

Background

The primary source of carbon is one of the most fundamental questions regarding the development of microbial communities in serpentinite-hosted systems. The hydration of ultramafic rock to serpentinites releases large amounts of hydrogen and creates hyperalkaline conditions that deplete the environment of dissolved inorganic carbon. Metagenomic studies suggest that serpentinite-hosted microbial communities depend on the local redissolution of bicarbonate and on small organic molecules produced by abiotic reactions associated with serpentinization.

Methods

To verify these bioinformatic predictions, microbial consortia collected from the Prony Bay hydrothermal field were enriched under anoxic conditions in hydrogen-fed bioreactors using bicarbonate, formate, acetate, or glycine as the sole carbon source.

Conclusions

With the exception of glycine, the chosen carbon substrates allowed the growth of microbial consortia characterized by significant enrichment of individual taxa. Surprisingly, these taxa were dominated by microbial genera characterized as aerobic rather than anaerobic as expected. Our results indicate the presence of both autotrophic and heterotrophic taxa that may function as foundation species in serpentinite-hosted shallow subsurface ecosystems. We propose that an intricate feedback loop between these autotrophic and heterotrophic foundation species facilitates ecosystem establishment. Bicarbonate-fixing Meiothermus and Hydrogenophaga, as well as formate-fixing Meiothermus, Thioalkalimicrobium, and possibly a novel genotype of Roseibaca might produce organic compounds for heterotrophs at the first trophic level. In addition, the base of the trophic network may include heterotrophic Roseibaca, Acetoanaerobium, and Meiothermus species producing CO2 from acetate for a more diverse community of autotrophs. The cultivated archaeal community is expected to recycle CH4 and CO2 between Methanomicrobiales and Methanosarcinales with putative Woesearchaeales symbionts.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40793-025-00797-0.

Keywords: Serpentinization, Submarine alkaline vent, Hydrothermal system, Alkaliphile, Hydrogenotroph, Primary production, Carbon fixation, Origin of life

Background

Hydrothermal vents driven by serpentinization are a window into the past, possibly all the way back to the origin of life. Serpentinization, the hydration of mantle rock, most likely occurred on early Earth in ultramafic seafloor and peridotite exposures. On modern Earth, the resulting geochemical milieu characterized by strongly reducing, low-oxygen and hyperalkaline conditions hosts extremophile microbial communities growing independently of oxygen (O2) [1]. Elucidating their metabolism may be key to understanding the first life forms and the current limits of life [2].

The hydration of mantle rocks to serpentinites produces hydrothermal fluids enriched in hydrogen (H2) and hydroxide ions. While the released H2 constitutes a potent energy source for microbial metabolism, the elevated pH poses a fundamental energetic challenge to life. Firstly, it inverts the cell membrane potential, requiring particular adaptations to maintain the energetic driving force of the cell [3]. It has been shown that some alkaliphiles use Na+ instead of proton gradients or can concentrate protons at the cell surface [4]. Secondly, the elevated pH reduces the solubility of essential nutrients such as phosphorous [5] and drives the carbonate equilibrium away from dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC). The latter is usually vital for primary production, which constitutes the base of the trophic network. In hyperalkaline environments, however, carbon dioxide (CO2) delivered by surface inflow precipitates as calcium carbonate (CaCO3), forming carbonaceous hydrothermal chimneys over time and removing DIC from the pool of bioavailable carbon [6]. This phenomenon raises one of the main questions regarding the functioning of serpentinite-hosted microbial ecosystems: which carbon source can replace CO2 in primary production?

Various small organic acids and amino acids produced abiotically by serpentinization may hold the key to this issue. Formate and acetate are yielded in Fischer–Tropsch and Sabatier-type reactions catalyzed in the hydrothermal fluid [3, 7, 8]. Similarly, serpentinizing conditions have been shown to facilitate the abiotic synthesis of glycine [9, 10]. Formate, acetate, and glycine concentrations vary widely between serpentinized systems, but all three compounds are likely ubiquitous in such environments [7, 10, 11]. In addition, some serpentinite-hosted microorganisms have been shown to grow on solid CaCO3 [4, 12]. The physiological mechanism they employ probably involves the local redissolution of bicarbonate ions [4]. For organisms capable of such redissolution, the carbonaceous hydrothermal chimneys could provide a vast carbon source.

By definition, primary producers are autotrophic and use an inorganic carbon source that is converted into more complex carbohydrates via a carbon fixation pathway. For this reason, acetate and glycine in particular, but also formate, are not usually considered as primary carbon sources. Due to the lack of DIC, however, the concept of primary production in serpentinite-hosted ecosystems might need to be reconsidered. This is supported by the fact that all of the compounds mentioned above are derived from an abiotic source, which per se challenges the definitions of heterotrophy and autotrophy [13].

In this context, formate and bicarbonate can be interpreted as autotrophic carbon sources. Once accumulated in the pH-neutral cytoplasm, they are both converted into CO2 by the formate dehydrogenase or the carbonic anhydrase, respectively [14, 15]. The yielded CO2 can then be used in any of the seven known carbon fixation pathways to form acetyl-CoA or other precursors for respiration, fermentation, and heterotrophic metabolism. On the contrary, acetate and glycine cannot be metabolized through a canonical carbon fixation pathway and thus constitute heterotrophic carbon sources. Acetate is directly converted to acetyl-CoA by the acetyl-CoA synthetase or the acetate kinase and phosphate acetyltransferase [16, 17], while glycine is reduced to acetyl phosphate by the glycine reductase complex. The only known exception to this heterotrophic route is syntrophic acetate oxidation (SAO), where a symbiotic bacterium oxidizes acetate to CO2 and H2 or formate for an autotrophic methanogen or sulfate-reducer. However, SAO has only been described in a handful of taxa [18]. While heterotrophs are not typically regarded as primary producers, they might play a more fundamental role in the serpentinite-hosted trophic network than elsewhere. Lang et al. [19] proposed that heterotrophic foundation species could produce CO2 for a diverse community of autotrophs, including those without formate or bicarbonate uptake genes. Acetate- and glycine assimilating heterotrophs could thus be as essential for the trophic chain as bicarbonate- or formate-fixing autotrophs.

In the last decade, the metabolic potential of these hypothetical primary producers has mainly been explored through metagenomic approaches, leading to some exciting discoveries of novel routes for non-canonical carbon fixation pathways and hypotheses on ecosystem functioning [4, 10, 15, 16]. However, many of the concerned enzymes are bidirectional or have other metabolic functions, rendering it difficult to evaluate such hypotheses based on metagenomic predictions alone. This requires experimental evidence, for example by observing the metabolic activity of targeted communities in culture. However, the cultivation of serpentinite-hosted communities has proven problematic, mainly because the physicochemical conditions associated with serpentinization are challenging to reproduce in the laboratory. Previous attempts have focused on microcosm experiments, but produced contradictory results: For example, Kohl et al. [20] observed methane (CH4) production from bicarbonate, formate and acetate in microbial communities from The Cedars ophiolite, while the same experiment failed with microbial communities from the Tablelands ophiolite [21]. To bridge this gap, we performed cultivation experiments on natural serpentinite-hosted communities in controlled laboratory conditions. These communities were recovered from the shallow Prony Bay hydrothermal field [22] and enriched on a bioreactor platform, which allowed the control of various environmental parameters such as pH, temperature, and continuous gas supply (Fig. 1). Four hydrogenotrophic culture conditions were established, H2 representing the principal electron donor of the natural system, and each of these enrichment cultures was alimented with bicarbonate, formate, acetate, or glycine as the sole carbon source. Carbon consumption, growth, diversity, and taxonomic composition were compared between the microbial consortia to determine which carbon sources facilitate the development of microbial communities in serpentinizing conditions and which taxonomic groups are selected on them.

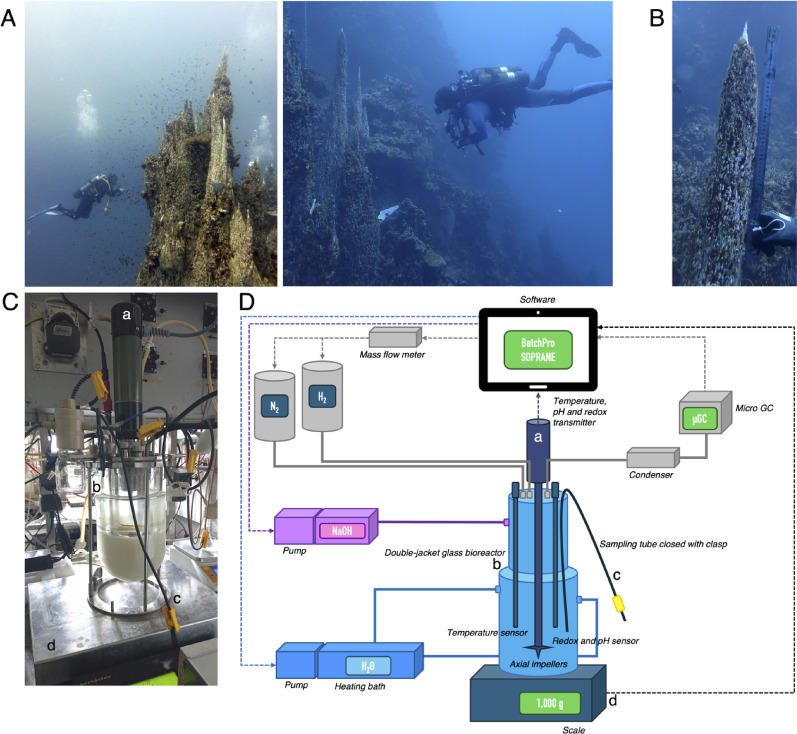

Fig. 1.

A The “Aiguille de Prony” which measures 38 m from top to bottom. The sampling location is shown in the photo to the right. B The chimney collected from the “Aiguille de Prony”. C Bioreactor used in cultivation experiments with a working volume of 1.5 L. D Schematic illustration of the bioreactor set-up. Pieces that are also visible in C are marked with letters

Material and methods

Study site

The shallow Prony Bay hydrothermal field is located at the southern end of New Caledonia [22]. As a coastal system, it comprises several sites from land to sea that reflect the geomicrobiological characteristics of terrestrial and marine serpentinite-hosted systems, respectively [5, 23–26]. The most prominent hydrothermal mount is the submarine “Aiguille de Prony”, a large carbonate massif (38 m high from its base at a depth of around 45 m, depending on the tide, to its summit) (Fig. 1A). The most active zone lies at a depth of 20 m, where numerous chimneys emit hydrothermal fluid. The concentration of DIC measured in the fluid remains below 1 mmol L−1, with pH values ranging from 10 to 11.3, Eh values ranging from − 540 to – 680 mV, and a temperature of around 35 °C measured in the endmember fluid [22, 27].

During a field campaign in 2022, the upper part (~ 50 cm long and max 20 cm in diameter) of a mature, active chimney was sampled by SCUBA divers. The chimney was covered with a watertight bag, letting the hydrothermal fluid accumulate for a few hours until the ambient seawater was entirely removed. The chimney was then sawed off, the bag hermetically sealed and transported to the field laboratory. The chimney was divided into slices of approximately 35 mm under sterile conditions. The outer layer was removed with a chisel (cleaned with alcohol and flame-sterilized using a Bunsen burner) to isolate the center of each slice. This part was ground with mortar and pestle (autoclaved) in an anaerobic chamber by adding hydrothermal fluid from the sampling site. The resulting slurry was aliquoted into hermetically sealed Schott bottles and stored under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere at 4–8 °C until inoculation of enrichment cultures.

Experimental set-up

Experiments were carried out in double-jacketed glass bioreactors (Pierre Guerin, France) with a working volume of 1.5 L (Fig. 1B). The vessels were first sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C during 20 min. 1 L of growth medium (see composition below) was sterilized by filtration (0.2 µm) and then directly added into the reactor via a tube connecting the reactor to the filter. To avoid precipitation in the growth medium, the pH was maintained at 7.0 during the filtration step. The reactor was agitated at 500 rpm, the temperature was continuously montitored by a probe (Prosensor pt 100, France) and maintained at 35 ± 2 °C via water circulation in the double jacket via a thermostat (Julabo, SE6, Switzerland). The pH, continuously mesured by an electrode (Mettler Toledo InPro 3253, Switzerland), was then increased to the setpoint of 10.5 by automatic addition of a buffer solution (1 M NaOH) with a peristaltic pump. The bioreactors were supplied with a continuous flow of H2 and N2 gas at 5 ml min−1 each by two thermal mass flow meters (Bronkhorst el flow, Netherlands) to maintain anaerobic conditions and provide a metabolic energy source. The outflow gas effluent was condensed using cold water from a cryostat (Julabo F25, switzerland) to prevent evaporation of the culture medium. All equipment (pH and temperature probe, massflow meter, agitation motor and thermostat) was connected to a Wago programmable logic controller (France) via a serial link (RS232/RS485), 4–20 mA analog loop or a digital signal. The programmable logic controller was connected to a computer for process monitoring and data acquisition (BatchPro software, Decobecq Automatismes, France).

Four culture conditions were inoculated with 35 ± 5 g of chimney slurry and supplied with 5 mM of sodium acetate, sodium formate, glycine, or sodium bicarbonate as the sole carbon source. The enrichment cultures were established in batch mode using 1 L of minimal growth medium, which was inspired by the natural composition of Prony Bay hydrothermal fluid [22]: 3.7 mM NH4Cl, 0.92 mM K2HPO4, 86 mM NaCl, 12 mM MgCl2(6H2O), 5 mM Na2S2O3(5H2O), 5 mM Na2SO4, 3 mM CaCl2(2H2O), 5 mL L−1 Balch’s trace element solution [28], 0.4 mL L−1 Balch’s vitamin solution [28] and 1 mL L−1 trace metal solution. The latter contained 1.42 g L−1 FeSO4, 1.6 g L−1 NiSO4 (6H2O), 38 mg L−1 Na2WO4(2H2O) and 3 mg L−1 Na2SeO3(5H2O) in the stock solution. The sulfate and thiosulfate salts present in the growth media were added as a source of electron acceptors (note that thiosulfate can also be used as an energy source).

Each culture condition was tested twice: the first experimental replicate included the enrichment cultures Ac1, Fo1, G1, Bc1 and the second experimental replicate the enrichment cultures Ac2, Fo2, G2, Bc2 (acetate being abbreviated to Ac, formate to Fo, glycine to G and bicarbonate to Bc). All enrichment cultures were maintained for 25 or 26 days and sampled every 2–3 days. Samples were immediately subdivided and prepared for different types of analysis.

Biochemical analysis

The consumption of acetate and formate was monitored via high-performance liquid chromatography (Dionex Ultimate 3000 from Thermofisher Scientific, USA). Samples were centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, 20 μL of the recovered non-diluted supernatant was injected into the column (Biorad HPX87H, USA) at 35 °C and eluted at 0.6 mL min−1 with a solution of 2.5 mM H2SO4. Detection was done by a refractive index detector (Iota2, Precision Instruments, France). In addition, the consumption of sulfate and thiosulfate as electron acceptors was measured via ion chromatography (Dionex ICS5000, USA). 10 μL of 1:10 diluted supernatant was injected into the column (Dionex AS9HC, USA) and eluted at 1 mL min−1 with a 9 mM buffer solution of Na2CO3 and NaHCO3. A suppressor (AERS500, Dionex, USA) was placed before the conductivity detector to improve the baseline signal. Both chromatographs were connected to a computer with the Chromeleon 7.2 software (Thermofisher, USA) for data recording and peak treatment.

Culture growth

The number of cells was monitored via fluorescence microscopy. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde (final concentration in sample 2%) and diluted with sterile growth media according to the cellular density. Subsequently, 2 mL of diluted sample was filtered onto white polycarbonate filters (0.2 μm porosity and 25 mm diameter from Nucleopore Whatman, USA), which were then rinsed with sterile growth medium using a vacuum pump. After filtration, the polycarbonate filters were placed on microscope slides for staining with 10–20 μL of 3.15 µM DAPI (diluted in mounting solution from CitiFluorTM AF1 Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA). Cells were counted in 15 random fields using an OLYMPUS BX-61 microscope with a filter at 372 nm (Evident, Japan). Samples were analyzed in duplicates. The number of cells was calculated with the formula

|

with xmean being the mean number of cells per field, Nfield being the total number of fields, D being the dilution and Vfiltered the volume of the filtered sample.

Alpha and beta diversity

The taxonomic composition at three different time points per culture (on the first day, in the middle, and on the last day), plus the inoculum of each experimental replicate, was assessed via 16S rRNA analysis. Approximately 14 mL of culture was centrifuged at 7000 rpm and 4 °C for 30 min. The pellet was recovered, and the DNA was extracted following the standard protocol of the ZymoBIOMICS DNA/RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, USA). The yielded DNA quantity and quality were evaluated on a NanoDrop One (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) and a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). Amplification and Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the 16S rRNA V3-V4 region was performed by MrDNA (Texas, USA) with two primer pairs targeting mostly bacteria (341F: 5-CCTACGGGNBGCWSCAG and 805R: 5-GACTACNVGGGTATCTAATCC) and archaea (344F: 5-AYGGGGYGCASCAGGSG and 806R: 5-GGACTACVSGGGTMTCTAAT) respectively. Library preparation was performed using the in-house bTEFAP® 16S assay, including PCR amplification, indexing, equimolar pooling, and purification prior to Illumina sequencing.

The bioinformatic analysis was performed in R and separately for each primer pair. Filtering and trimming of demultiplexed reads were performed in DADA2 [29], and samples with a low number of reads (< 180) were removed (one intermediate sample from the culture grown on glycine for bacterial sequences and one final sample each for the enrichment cultures grown on acetate, formate, bicarbonate and glycine for archaeal sequences). Denoised and dereplicated reads were merged into ASVs, allowing no mismatches in the overlapping region of forward and reverse reads. Taxonomic assignment of ASVs was performed based on the SILVA database version 138.1 [30] with a minimum bootstrap value of 60. The bacterial data set was rarefied to the minimum number of reads (11420) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The archaeal data set contained 766 bacterial ASVs, which were pruned to avoid bias in archaeal community analysis. Since archaea constitute only 1–10% of the prokaryotic community in the low-biomass Prony environment [23], cross-amplification of bacterial sequences with archaeal primers is not unexpected. Subsequently, the archaeal data set was rarefied to a depth of 12% (721 reads) (Supplementary Fig. 2B), preserving 88% of samples left after the initial quality control in DADA2 [29]. Alpha diversity indices were calculated using the microbiome package [31] and the Microbiota Process package [32]. Subsequently, a centered log-ratio transformation was performed on the read counts using the zCompositions package [33]. On the transformed data, an Aitchison distance matrix (k = 5) was constructed for both bacterial (Supplementary Fig. 3A) and archaeal (Supplementary Fig. 3B) sequences and visualized using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) with the vegan package [34]. To formally test for differences among groups, we applied permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using the adonis2 function, assessing the effects of carbon source, sampling timepoint, and experimental replicate on the observed variation. To ensure the validity of this analysis, a combined PERMANOVA model was calculated on the interaction of carbon source and sampling timepoint to inspect whether the data’s time series structure significantly affected the observed sample variation and whether it was reasonable to assess sample variability with separate models. Furthermore, analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed to verify if observed differences in distance were confounded by differences in dispersion amongst groups. To identify which ASVs were driving the individual variables’ effects on sample variation the most, coefficients for the respective variable groups were extracted from the PERMANOVA model using the adonis function of the vegan package [34]. ASV relative abundance was calculated with the phyloseq package by normalizing ASV read counts to total sample read counts [35].

Results

Culture growth

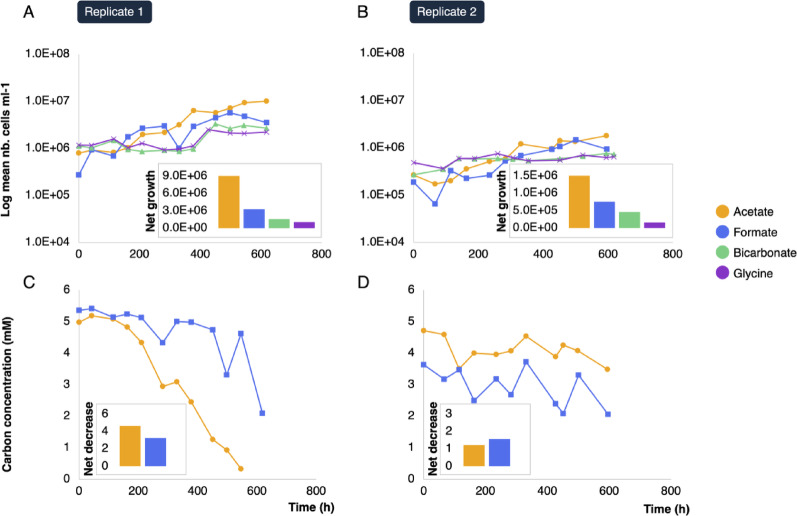

Cellular net growth was higher in the microbial consortia grown on acetate than on formate, bicarbonate and glycine which did not feature much growth. In the second replicate, net growth was reduced by an approximate factor of ten (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1A) and the net consumption of acetate and formate was much lower than in replicate 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1B). Cell morphologies included mostly cocci, bacilli and rods and did not vary significantly between culture conditions.

Fig. 2.

Microbial growth and carbon consumption in the first experimental replicate (A, C; enrichment cultures Ac1, Fo1, G1, Bc1) and in the second replicate (B, D; enrichment cultures Ac2, Fo2, G2, Bc2). The number of cells was counted via DAPI-staining and fluorescence microscopy. The concentration of acetate and formate in the respective consortia was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. The net increase of cells and the net decrease of acetate and formate (shown as inserts) were calculated as the difference between the first and last sampling timepoint

Alpha diversity

Overall, the number of bacterial taxa (853 ASVs before and 838 ASVs after rarefaction) was much higher than that of archaeal taxa (71 ASVs before and 66 ASVs after rarefaction). Bacterial alpha diversity and evenness of bacterial taxa were higher in the inoculum samples than the microbial consortia grown on glycine, followed by the consortia grown on formate, bicarbonate, and acetate (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 2A). Archaeal alpha diversity was higher in the microbial consortia grown on glycine, than the inoculum; it did not differ much between the consortia grown on formate, bicarbonate, and acetate. Evenness of archaeal taxa was higher in the inoculum than in the consortia grown on glycine, followed by the consortia grown on formate, acetate and bicarbonate (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Table 2B).

Fig. 3.

Alpha diversity and evenness calculated to the observed number of ASVs, the Shannon index and the Pielou index in bacterial A and archaeal B sequences from the inoculum (grey) and microbial consortia grown on acetate (yellow), formate (blue), bicarbonate (green) or glycine (purple). Values for the same conditions from both experimental replicates are combined

Beta diversity

Beta diversity showed considerable overlap between bacteria (Fig. 4A) and archaea (Fig. 4B) of the different microbial consortia. Nevertheless, significant differences in bacterial variation were observed by NMDS. According to PERMANOVA tests, the carbon source explained 29.12% of this variation, the time of sampling 22.3%, and the experimental replicate number 14.45%. The interaction between carbon source and sampling time was insignificant, with the individual effect of both variables remaining significant in the combined model, validating the statistical model used (Supplementary Table 3A). Two Rhodobacteraceae ASVs (one classified to the order level as Roseibaca) were the most significant drivers of sample dissimilarity by carbon source, indicated by their relatively high PERMANOVA coefficients (Fig. 5A). For the sampling time, a Meiothermus ASV was the most significant driver of sample dissimilarity (Fig. 5B). For the experimental replicate number, the most critical drivers of sample dissimilarity were two ASVs associated with Pseudahrensia and Dethiobacteraceae, respectively (Fig. 5C). ASVs driving sample similarity in both carbon source and sample time were associated with the cluster of uncultivated MSBL5 (Dehalococcoidia, Desulfovibrio and ML635J-40 aquatic group (Bacteroidales) taxa (Fig. 5A, B). For the archaea, the carbon source and replicate number had no significant effect on the distance matrix. Sampling time slightly affects community composition, explaining only 8.2% of the variance (Supplementary Fig. 3B). The most significant driver of sample dissimilarity according to the sampling time was an ASV identified as Woesearchaeales. Drivers of sample similarity were ANME-3 and Syntrophoarchaeaceae which are both associated with the Methanosarcinales (Fig. 5D). All ANOVA tests were non-significant, confirming the reliability of the variables’ effects on observed differences in bacterial and archaeal distance matrices.

Fig. 4.

Aitchison distance matrices (k = 5) constructed on bacterial A and archaeal B sequences from the inoculum (grey) and microbial consortia grown on acetate (yellow), formate (blue), bicarbonate (blue) or glycine (purple). Distance matrices were constructed using a non-metric multidimensional scaling on log-ratio transformed data. The name of enrichment cultures Ac1, Fo1, G1, Bc1 (corresponding to the replicate 1) and enrichment cultures Ac2, Fo2, G2, Bc2 (corresponding to the replicate 2) also indicated the sampling time (t0, t7, t12, t13, t16, t23, t25, t26)

Fig. 5.

Top ASVs driving significant effects of carbon source, sampling timepoint and experimental replicate on sample variation in bacterial A, B, C and/or archaeal D sequences. Different ASVs are color-coded according to the lowest taxonomic level to which they were assigned. Coefficients of variable groups were calculated in permutational multivariate analysis of variance tests; corresponding F values, p values and R2 value are given on the top right of each graph. Positive coefficients indicate an effect of the respective ASV on sample dissimilarity, negative coefficients indicate an effect on sample similarity. To enhance readability given the numerous color shades, key taxonomic groups are highlighted with symbols

Taxonomic composition

The evolution of the taxonomic composition over time in the different microbial consortia was consistent with alpha and beta diversity predictions. On all carbon sources except glycine, the bacterial community changed significantly over time, and enrichment of specific taxonomic groups was observed (Fig. 6A). The inoculum and samples from the first day of culture were mainly composed of the genera Acetoanaerobium and Roseibaca and a relatively smaller proportion of Methyloceanibacter, Truepera, Desulfovibrio, Caldicobacter, Filomicrobium, and Ruegeria. Acetate-grown enrichment cultures displayed a large proportion of Roseibaca and a small proportion of Halomonas after 12 (Ac2) and 14 (Ac1) days, respectively. The strong enrichment of Roseibaca was maintained until the end of the culture, next to a lesser enrichment of Meiothermus (Ac1 and Ac2). Formate-grown enrichment cultures also showed a strong enrichment of Roseibaca (Fo1 and Fo2) and a slighter enrichment of Meiothermus (Fo1) and Thioalkalimicrobium (Fo1) at the end of experiments, and a predominance of Acetoanaerobium (Fo2) after 12 days. On bicarbonate, the opposite was observed: a strong enrichment of Meiothermus, and a less pronounced (re-)enrichment of Roseibaca at the end of the culture (Bc1 and Bc2), next to an enrichment of Hydrogenophaga (exclusively observed in Bc1). On day 7, the culture was dominated by Halomonas next to Thioalkalimicrobium and Reinekea enrichments (Bc1), and on day 13, Roseibaca next to a slight enrichment of Halomonas (Bc2). Little development was observed on glycine: the community structure resembled the inoculum throughout the experiment in both replicates 1 and 2.

Fig. 6.

Taxonomic composition of bacterial A and archaeal B microbial consortia grown on acetate (Ac), bicarbonate (Bc), formate (Fo) or glycine (G) in the first (1) and second (2) experimental replicate over time. For each carbon source and experimental replicate, the taxonomic composition of up to three different timepoints is depicted, including the first day (t0), an intermediate day and the last day (t25 or t26) of the culture. In addition, the taxonomic composition of the inoculum used in the respective experimental replicate (INOC) is shown. For bacterial sequences, only genera with a relative abundance > 3% are depicted. For archaeal sequences, all orders are shown. Note that ANME-3 is a genus of the archaeal order Methanosarcinales (both depicted in the same color) which was also amplified by the bacterial primers. To enhance readability given the numerous color shades, key taxonomic groups are highlighted with symbols

The archaeal community (Fig. 6B) was strongly dominated by the order Methanosarcinales (ASV classified to the genus level as ANME-3) in the inoculum, next to a small proportion of Nitrosopumilales (INOC2). They were also predominant in all culture samples except for the end of the culture grown on bicarbonate, where a strong enrichment of Methanomicrobiales was observed (Bc2). In addition, a slight enrichment of Woesearchaeales was observed in the middle and at the end of the culture grown on acetate (Ac1 and Ac2) and formate (Fo1), as well as on day 7 of the culture grown on bicarbonate (Bc1). They were also present at the beginning (G2), middle, and end (G1) of the culture grown on glycine, but their relative abundance decreased over time.

Discussion

Taxonomic composition of the natural community

The natural bacterial community was dominated by several taxonomic groups that are commonly found in Prony Bay and other serpentinite-hosted environments. Acetoanaerobium is an anaerobic bacterium that can produce acetate from the fermentation of complex carbohydrates; it is one of the strains that has been isolated from Prony Bay hydrothermal chimneys [36]. Close relatives of Desulfovibrio, an anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacterium, have been found in Prony Bay, at the serpentinized Costa Rica Margin and in Lost City [15, 24, 37]. Likewise, the facultatively anaerobic chemoorganotroph Truepera has been documented in Prony Bay and in the Coast Range ophiolite [25, 38]. None of these marker taxa were significantly enriched in our culture conditions (except Acetoanaerobium on formate), suggesting that they rely on the metabolic products of other community members or that their growth is limited by other experimental conditions such as the presence of light promoting the growth of dominant phototrophs or the absence of complex organic growth substrates.

Carbon substrates facilitating microbial enrichments

All carbon sources facilitated culture growth and development except for glycine. The microbial consortium maintained on glycine featured a very low growth rate (Fig. 2), and diversity and evenness scores remained consistently elevated (Fig. 3), suggesting no significant enrichment of taxonomic groups specialized on the uptake of this compound. This was confirmed by the taxonomic composition of the consortia, which did not change much over time and remained similar to the natural community (Fig. 6). The use of glycine as a carbon source in a serpentinization context was proposed by Nobu et al. [10], who showed that glycine reductase genes are abundant in metagenomes from various serpentinite-hosted systems. The glycine reductase complex is a central enzyme in the reductive glycine pathway, a recently proposed seventh carbon fixation pathway [17]. While it is indeed possible for exogenous glycine to enter the glycine reductase complex via a membrane-bound transporter, it might also be produced as an endogenous intermediate in the reductive glycine pathway. Similar to the other carbon fixation pathways, the reductive glycine pathway starts with one molecule of CO2 that could be yielded from both formate [14] and bicarbonate [14, 15]. It is likely that in Prony Bay, the use of formate and bicarbonate as carbon sources is more favorable compared to glycine whose natural concentration is expected to be low [10]. This might explain the limited growth observed in this experimental condition.

Contrary to glycine, microbial growth was observed in enrichment cultures grown in presence of bicarbonate, formate and especially acetate (Fig. 2). This was accompanied by a steep decrease in diversity and evenness (Fig. 3), suggesting the enrichment of specific taxonomic groups consuming these carbon sources. This is confirmed by the evolution of the taxonomic composition of the enrichment cultures after the second and third week of incubation (Fig. 6). The main driver of sample dissimilarity according to carbon source was the Roseibacaceae family (Figs. 4 and 5).

Microbial taxa dominating the enrichment cultures

The consortia grown on acetate and formate were heavily dominated by the genus Roseibaca previously detected in the Aqua de Ney serpentinizing spring (Trutschel et al., 2022, 2023). Members of this genus are anoxygenic photoheterotrophs and rose-colored due to their bacteriochlorophyll pigments [39, 40]. They have previously been detected in Prony Bay, where their biofilms may be responsible for the dark-pink color of the chimney exteriors [25]. As all our enrichment cultures were incubated at O2 concentrations below 0.5%, the growth of Roseibaca, which is characterized as strictly aerobic, was quite unexpected (Supplementary Fig. 4). Since the experiments were performed in clear glass bioreactors, light could have favored the growth of oxygenic phototrophs locally supplying O2. However, no significant occurrence of cyanobacteria (the only bacterial group that performs oxygenic photosynthesis) was observed [41] (Fig. 6). The cultivated Roseibaca members may therefore be facultative anaerobes. The carbonaceous chimney wall is very porous, and at a depth where O2 becomes scarce, light might still penetrate. The bacteriochlorophyll pigments used in anoxygenic photosynthesis can absorb light at near-infrared wavelengths and facilitate photosynthesis in deep water or sediments [41]. In addition, the occurrence of normally strictly aerobic taxa in anoxic serpentinized fluids is a relatively common phenomenon and has been suggested to drive localized speciation of closely related populations along the steep O2 and redox gradients from surface waters to subsurface fluids [42].

Next to Roseibaca, the consortia grown on acetate and formate included a significant proportion of Meiothermus, previously detected in serpentinizing springs of New Caledonia [43, 44] in the Zambales Ophiolites, Philippines [45], and in the Samail Ophiolite, Oman [11]. The cultures alimented with formate additionally featured a slight enrichment of Thioalkalimicrobium, reclassified into Thiomicrospira [46]. Thioalkalimicrobium or Thiomicrospira were previously observed in the submarine Lost City and Prony Bay systems [7, 24, 47] and the terrestrial Aqua de Ney spring [48]. Their enrichment might be related to the thiosulfate consumption observed in formate-grown cultures (see Supplementary Fig. S1) as they are known as both thiosulfate- and H2-oxidizers [49]. The formate-grown enrichment cultures also displayed mid-term enrichment of Acetoanaerobium, an anaerobic genus previously isolated from Prony Bay [36]. The latter probably fermented organic compounds produced by the consortium during the first week and does not count amongst primary producers.

The consortia grown on bicarbonate was strongly dominated by the Meiothermus genus. Similar to Roseibaca, Meiothermus has been described as a strictly aerobic heterotroph; however, Munro-Ehrlich et al. [42] provided evidence that subsurface populations can undergo parapatric speciation and develop traits of facultatively anaerobic autotrophs, such as the gain of [NiFe] hydrogenases. Similar to these subsurface genotypes, it is likely that the Meiothermus population cultivated on bicarbonate grew chemoautotrophically by producing CO2 in the cytoplasm with H2 as electron donor. Besides Meiothermus, a significant enrichment of the chemoautotrophic Hydrogenophaga, a sister group of H2-oxidizing Serpentinimonas (a marker genus of serpentinization) which features bicarbonate-uptake genes, could be observed along with enrichment of Roseibaca [4, 50]. While Roseibaca are usually classified as photoheterotrophs, their consistent and significant growth on bicarbonate might suggest that we enriched a novel photoautotrophic genotype. In addition, the genus Halomonas was dominant in the second week of the first experimental replicate, a thiosulfate-oxidizing bacterium that is typically observed in serpentinite-hosted environments. As this genus is heterotrophic, however, it is unlikely that it used bicarbonate as a carbon source [48, 51, 52] (Fig. 6).

The initial archaeal community consisted almost exclusively of the ANME-3 cluster, which belongs to the Methanosarcinales. This group was not enriched but maintained throughout the entirety of the cultivation experiments on all carbon sources, with a predominance so strong that the taxonomic composition did not vary significantly between carbon sources (Fig. 6B). The Methanosarcinales are one of the most typical taxa associated with serpentinization-hosted ecosystems. Two phylotypes belonging to this group have been described. The Lost City Methanosarcinales (LCMS) are more closely related to ANME-3 (our most abundant ANME-3 ASV shares 95.31% sequence identity with the LCMS), while The Cedars Methanosarcinales (TCMS) are intermediate between the ANME-2c and Methanomicrobiales clusters [53, 54]. While ANME-3 are classified as anaerobic methane oxidizers (AOM), it has been shown that they possess all the genes necessary for methanogenesis and LCMS are usually described as methanogens [53]. In addition to the maintenance of Methanosarcinales, a slight enrichment of Woesearchaeales was observed on formate, bicarbonate and particularly acetate in the first experimental replicate. This enrichment accounted for an almost significant influence of the sampling time on the community structure (Fig. 5D). Since the abundances shown here are relative, the archaeal taxonomic composition may reflect an emerging symbiotic relationship between Methanosarcinales and Woesearchaeales. The Woesearchaeales are probably incapable of an independent lifestyle and have been suggested to establish symbiotic relationships with methanogens [55]. So far, only heterotrophic genotypes are known [55]. While only a handful of taxa have been shown to perform SAO, it might be possible that our Woesearchaeales ASV is able to oxidize acetate to CO2 and H2 in presence of a Methanosarcinales as syntrophic partner. In the second experimental replicate, a remarkable enrichment of Methanomicrobiales was observed on bicarbonate towards the end of the culture (81.44% ASV sequence identity with TCMS). This order is methanogenic [56] and probably outcompeted the symbiosis between Methanosarcinales and Woesearchaeales (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, a recent study reclassified TCMS as acetogenic Methanocellales featuring bicarbonate uptake genes [57]. It is thus likely that our ASV is able to fix bicarbonate as an autotrophic carbon source.

The consortium of foundation species

The predominance of phototrophic Roseibaca in two culture conditions suggests that our results most accurately represent the microbial community in Prony Bay’s shallow subsurface. The pronounced growth on acetate supports the foundation species theory proposed by Lang et al. [19]. Their original model was based on a high occurrence of sulfate reducers taking up formate and releasing CO2 in the deep-sea Lost City hydrothermal field. While it is likely that sulfate reducers (e.g. Desulfovibrio, Desulfonatronum) play an essential role in the deeper subsurface communities of Prony Bay, they were not enriched in the bioreactors despite sulfate and thiosulfate being the sole electron acceptors added to the cultures (Figs. 6 and 7A). On the contrary, at least two of the enriched taxa (Thioalkalimicrobium and Hydrogenophaga) have previously been reported to reduce nitrate, suggesting that the respiration of nitrate could play a role in this anaerobic natural system. The electron acceptor used by the cultivated consortia remains unclear (Fig. 7A). In the bioreactors alimented with acetate, the microbial consortium of putative heterotrophic foundation species was heavily dominated by the anoxygenic photoheterotroph Roseibaca, suggesting that this metabolic type plays a more important role in serpentinite-hosted environments than previously assumed. Besides Roseibaca, the putative consortium of heterotrophic foundation species included the heterotrophic genotype of Meiothermus [42]. Together, Roseibaca and Meiothermus may produce CO2 from acetate for various autotrophs on the first trophic level in the natural ecosystem (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Proposed metabolic network of the cultivable Prony Bay hydrothermal community. A Metabolic potential of enriched key taxa according to the references cited in the main text. B Hypothesized trophic relationships. Putative foundation species are shown next to metabolic categories, with symbols indicating all culture conditions they were enriched in. Note the following abbreviations: SAO for syntrophic acetate oxidation, Bc for bicarbonate (diamond), Fo for formate (circle), Ac for acetate (triangle)

Next to these putative acetate-assimilating foundation species, we cultivated potential autotrophic foundation consortia on bicarbonate and formate. On bicarbonate, this concerned the autotrophic Meiothermus genotype described by Munro-Ehrlich et al. [42] and the hydrogenotrophic Hydrogenophaga. It is likely that the same Meiothermus genotype is part of base of the trophic network cultivated on formate, alongside the thiosulfate-oxidizing autotroph Thioalkalimicrobium and potentially a novel photoautotrophic genotype of Roseibaca. Together, these bicarbonate- and formate-fixing autotrophs could produce organic compounds for heterotrophs on the first trophic level such as Acetoanaerobium and Halomonas (Fig. 7B).

A special case of such carbon cycling between heterotrophs and autotrophs constitutes the relationship between methanogens and methanotrophs: unidentified methanotrophs could establish a supply of CO2 for autotrophic methanogens and vice versa. The Methanomicrobiales might perform methanogenesis with bicarbonate as carbon source, thus constituting an autotrophic foundation species. The predominant Methanosarcinales on the other hand are likely dependent on CO2 that is locally released by other community members. While endogenous CO2 supply might be provided by acetate-oxidizing Woesearchaeales, external CO2 could rely on acetoclastic methanogenesis in addition to methanotrophy (Fig. 7B).

Conclusion

Specific taxonomic groups were successfully cultivated from a shallow submarine Prony Bay chimney sample in anaerobic bioreactors simulating in-situ conditions. These reactors were operated with artificial hydrothermal fluid under a continuous flow of H2 gas, supplemented with sulfate and thiosulfate as the sole electron acceptors, and bicarbonate, formate, acetate or glycine as the sole carbon source. The enrichment culture with glycine featured only minimal growth and the taxonomic composition barely changed compared to the initial diversity observed in the inoculum. This either suggests that glycine plays a minor role in the natural microbial ecosystem, or that the experimental conditions did not accurately reproduce the natural conditions. The latter is supported by the observation of the generally very low growth rates on glycine, which might have required longer incubation periods. The pronounced growth on acetate supports a modified version of the foundation species theory proposed by Lang et al. [19]. Heterotrophic foundation taxa such as Roseibaca and Meiothermus (heterotrophic genotype) may produce CO2 from acetate, facilitating the development of a diverse community of autotrophs, including those without bicarbonate and formate transporters or symbionts. Autotrophic foundation species might include bicarbonate-fixing Meiothermus (autotrophic genotype) and Hydrogenophaga, as well as formate-fixing Meiothermus, Thioalkalimicrobium and potentially a novel photoautotrophic genotype of Roseibaca producing organic compounds for heterotrophs such as Acetoanaerobium and Halomonas. In the archaeal community, this reciprocal relationship is illustrated by CO₂ and CH₄ cycling Methanosarcinales with putative acetate-oxidizing Woesearchaeales symbionts, as well as bicarbonate-fixing Methanomicrobiales. We propose that such a feedback loop contributes to the diversification of the serpentinite-hosted community and explains the presence of well-established microbial communities in environments depleted of DIC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participants of the 2022 field campaign to Prony Bay; firstly the scientific divers of the ENTROPIE & IMAGO units at the IRD Research Center Nouméa: Bertrand Bourgeois, John Butler, Magali Boussion and Mahé Dumas, without whom this campaign would not have been possible; Clarisse Majorel and Isabelle Biegala for welcoming and assistance in their lab at IRD Nouméa, and Véronique Perrin for her valuable help in resolving all administrative and logistical difficulties. We would like to thank Dr. Ariane Bize (INRAe Prose, Antony, France) for the training and discussions on DNA Stable Isotope Probing, which could not be included in this article but was greatly appreciated, and Marc Garel (Mediterranean Institute of Oceanology UMR 7294, Marseille, France) for the help with cell counting. Furthermore, we would like to thank the OMICS platform with Marc Garel and Fabrice Armougom (Mediterranean Institute of Oceanology UMR 7294, Marseille, France), who provided the workflow and source code that our bioinformatic pipeline is based on.

Author contributions

GE directed the project. GE and AP initiated and supervised the study. GE, REP, RMP and MQ collected the samples. GE, AP, RMP, SD, REP, YCB and MQ developed the experimental design. AR, RMP, SD, and AP performed the experimental work. RMP and AR performed the initial data analysis. RMP performed the final data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and read and approved the final version.

Funding

This study was financed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) as part of the MICROPRONY project (19-CE02-0020–02; P.I. GE). RMP was awarded a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Education and Scientific Research. GE received financial support (MLD) from the IRD to organize and carry out the sampling campaign at the Prony Bay site.

Data availability

The raw 16S rRNA sequencing data analyzed in this study is available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information repository under the BioProject accession PRJNA1223160. Please note that the sequences amplified with the 341F and 805R primer set are referred to as ‘bacterial’ in this paper, but as ‘prokaryotic’ in the NCBI database. The sample metadata used to analyze beta diversity is included in the article and its additional files. The bioinformatic pipeline developed for this study is available on github: https://github.com/jampoa/16S-alpha–beta-div.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Russell MJ, Hall AJ, Martin W. Serpentinization as a source of energy at the origin of life: Serpentinization and the emergence of life. Geobiology. 2010;8:355–71. 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sojo V, Herschy B, Whicher A, Camprubí E, Lane N. The origin of life in alkaline hydrothermal vents. Astrobiology. 2016;16:181–97. 10.1089/ast.2015.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCollom TM, Seewald JS. Serpentinites, Hydrogen, and Life. Elements. 2013;9:129–34. 10.2113/gselements.9.2.129. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki S, Kuenen JG, Schipper K, van der Velde S, Ishii S, Wu A, et al. Physiological and genomic features of highly alkaliphilic hydrogen-utilizing Betaproteobacteria from a continental serpentinizing site. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3900. 10.1038/ncomms4900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frouin E, Lecoeuvre A, Armougom F, Schrenk MO, Erauso G. Comparative metagenomics highlight a widespread pathway involved in catabolism of phosphonates in marine and terrestrial serpentinizing ecosystems. mSystems. 2022. 10.1128/msystems.00328-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrenk MO, Brazelton WJ, Lang SQ. Serpentinization, carbon, and deep life. Rev Mineral Geochem. 2013;75:575–606. 10.2138/rmg.2013.75.18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazelton WJ, Mehta MP, Kelley DS, Baross JA. Physiological differentiation within a single-species biofilm fueled by serpentinization. MBio. 2011;2:e00127–11. 10.1128/mBio.00127-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fones EM, Colman DR, Kraus EA, Stepanauskas R, Templeton AS, Spear JR, et al. Diversification of methanogens into hyperalkaline serpentinizing environments through adaptations to minimize oxidant limitation. ISME J. 2021;15:1121–35. 10.1038/s41396-020-00838-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ménez B, Pisapia C, Andreani M, Jamme F, Vanbellingen QP, Brunelle A, et al. Abiotic synthesis of amino acids in the recesses of the oceanic lithosphere. Nature. 2018;564:59–63. 10.1038/s41586-018-0684-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nobu MK, Nakai R, Tamazawa S, Mori H, Toyoda A, Ijiri A, et al. Unique H2-utilizing lithotrophy in serpentinite-hosted systems. ISME J. 2022. 10.1038/s41396-022-01197-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rempfert KR, Miller HM, Bompard N, Nothaft D, Matter JM, Kelemen P, et al. Geological and geochemical controls on subsurface microbial life in the Samail Ophiolite, Oman. Front Microbiol. 2017. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bird LJ, Kuenen JG, Osburn MR, Tomioka N, Ishii S, Barr C, et al. Serpentinimonas gen. nov., Serpentinimonas raichei sp. nov., Serpentinimonas barnesii sp. nov. and Serpentinimonas maccroryi sp. nov., hyperalkaliphilic and facultative autotrophic bacteria isolated from terrestrial serpentinizing springs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2021;71(8):004945. 10.1099/ijsem.0.004945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schönheit P, Buckel W, Martin WF. On the origin of heterotrophy. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:12–25. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KS, Ferry JG. Prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:335–66. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brazelton WJ, McGonigle JM, Motamedi S, Pendleton HL, Twing KI, Miller BC, et al. Metabolic strategies shared by basement residents of the lost city hydrothermal field. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88:e00929-e1022. 10.1128/aem.00929-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brazelton WJ, Thornton CN, Hyer A, Twing KI, Longino AA, Lang SQ, et al. Metagenomic identification of active methanogens and methanotrophs in serpentinite springs of the Voltri Massif, Italy. PeerJ. 2017;5:e2945. 10.7717/peerj.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Andrea I, Guedes IA, Hornung B, Boeren S, Lawson CE, Sousa DZ, et al. The reductive glycine pathway allows autotrophic growth of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5090. 10.1038/s41467-020-18906-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmers PHA, Vavourakis CD, Kleerebezem R, Damsté JSS, Muyzer G, Stams AJM, et al. Metabolism and occurrence of methanogenic and sulfate-reducing syntrophic acetate oxidizing communities in haloalkaline environments. Front Microbiol. 2018. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang SQ, Früh-Green GL, Bernasconi SM, Brazelton WJ, Schrenk MO, McGonigle JM. Deeply-sourced formate fuels sulfate reducers but not methanogens at Lost City hydrothermal field. Sci Rep. 2018;8:755. 10.1038/s41598-017-19002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohl L, Cumming E, Cox A, Rietze A, Morrissey L, Lang SQ, et al. Exploring the metabolic potential of microbial communities in ultra-basic, reducing springs at The Cedars, CA, USA: experimental evidence of microbial methanogenesis and heterotrophic acetogenesis. J Geophys Res Biogeosciences. 2016;121:1203–20. 10.1002/2015JG003233. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrill PL, Brazelton WJ, Kohl L, Rietze A, Miles SM, Kavanagh H, et al. Investigations of potential microbial methanogenic and carbon monoxide utilization pathways in ultra-basic reducing springs associated with present-day continental serpentinization: the Tablelands, NL. CAN Front Microbiol. 2014. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monnin C, Chavagnac V, Boulart C, Ménez B, Gérard M, Gérard E, et al. Fluid chemistry of the low temperature hyperalkaline hydrothermal system of Prony Bay (New Caledonia). Biogeosciences. 2014;11:5687–706. 10.5194/bg-11-5687-2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quéméneur M, Bes M, Postec A, Mei N, Hamelin J, Monnin C, et al. Spatial distribution of microbial communities in the shallow submarine alkaline hydrothermal field of the Prony Bay, New Caledonia: Microbial communities of Prony Hydrothermal Field. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2014;6:665–74. 10.1111/1758-2229.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postec A, Quéméneur M, Bes M, Mei N, Benaïssa F, Payri C, et al. Microbial diversity in a submarine carbonate edifice from the serpentinizing hydrothermal system of the Prony Bay (New Caledonia) over a 6-year period. Front Microbiol. 2015. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frouin E, Bes M, Ollivier B, Quéméneur M, Postec A, Debroas D, et al. Diversity of rare and abundant prokaryotic phylotypes in the Prony hydrothermal field and comparison with other serpentinite-hosted ecosystems. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:102. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trutschel LR, Chadwick GL, Kruger B, Blank JG, Brazelton WJ, Dart ER, et al. Investigation of microbial metabolisms in an extremely high pH marine-like terrestrial serpentinizing system: ney springs. Sci Total Environ. 2022;836:155492. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monnin C, Quéméneur M, Price R, Jeanpert J, Maurizot P, Boulart C, et al. The chemistry of hyperalkaline springs in serpentinizing environments: 1. the composition of free gases in New Caledonia compared to other springs worldwide. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2021;126:e2021JG006243. 10.1029/2021JG006243. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balch WE, Fox GE, Magrum LJ, Woese CR, Wolfe RS. Methanogens: reevaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:260–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: high resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3. 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D590–6. 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahti L, Shetty S. Microbiome. 2017. 10.18129/B9.BIOC.MICROBIOME.

- 32.Xu S, Zhan L, Tang W, Wang Q, Dai Z, Zhou L, et al. Microbiotaprocess: a comprehensive R package for deep mining microbiome. Innovation (Camb). 2023;4:100388. 10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palarea-Albaladejo J, Martín-Fernández JA. zCompositions — R package for multivariate imputation of left-censored data under a compositional approach. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2015;143:85–96. 10.1016/j.chemolab.2015.02.019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oksanen J, Simpson GL, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, et al. vegan: Community ecology package. 2024.

- 35.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bes M, Merrouch M, Joseph M, Quéméneur M, Payri C, Pelletier B, et al. Acetoanaerobium pronyense sp. nov., an anaerobic alkaliphilic bacterium isolated from a carbonate chimney of the Prony Hydrothermal Field (New Caledonia). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65(Pt_8):2574–80. 10.1099/ijs.0.000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers TJ, Buongiorno J, Jessen GL, Schrenk MO, Fordyce JA, de Moor JM, et al. Chemolithoautotroph distributions across the subsurface of a convergent margin. ISME J. 2023;17:140–50. 10.1038/s41396-022-01331-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabuda MC, Putman LI, Hoehler TM, Kubo MD, Brazelton WJ, Cardace D, et al. Biogeochemical gradients in a serpentinization-influenced aquifer: implications for gas exchange between the subsurface and atmosphere. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2021;126:e2020JG006209. 10.1029/2020JG006209. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milford AD, Achenbach LA, Jung DO, Madigan MT. Rhodobaca bogoriensis gen. nov. and sp. nov., an alkaliphilic purple nonsulfur bacterium from African Rift Valley soda lakes. Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:18–27. 10.1007/s002030000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Labrenz M, Lawson PA, Tindall BJ, Hirsch P. Roseibaca ekhonensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an alkalitolerant and aerobic bacteriochlorophyll a-producing alphaproteobacterium from hypersaline Ekho Lake. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59(Pt 8):1935–40. 10.1099/ijs.0.016717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanada S. Anoxygenic photosynthesis — a photochemical reaction that does not contribute to oxygen reproduction—. Microbes Environ. 2016;31:1–3. 10.1264/jsme2.ME3101rh. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munro-Ehrlich M, Nothaft DB, Fones EM, Matter JM, Templeton AS, Boyd ES. Parapatric speciation of Meiothermus in serpentinite-hosted aquifers in Oman. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1138656. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1138656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mei N, Postec A, Monnin C, Pelletier B, Payri CE, Ménez B, et al. Metagenomic and PCR-based diversity surveys of [FeFe]-hydrogenases combined with isolation of alkaliphilic hydrogen-producing bacteria from the serpentinite-hosted prony hydrothermal field. New Caledonia Front Microbiol. 2016. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quéméneur M, Mei N, Monnin C, Postec A, Wils L, Bartoli M, et al. Procaryotic diversity and hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in an alkaline spring (La Crouen, New Caledonia). Microorganisms. 2021;9:1360. 10.3390/microorganisms9071360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woycheese KM, Meyer-Dombard DR, Cardace D, Argayosa AM, Arcilla CA. Out of the dark: transitional subsurface-to-surface microbial diversity in a terrestrial serpentinizing seep (Manleluag, Pangasinan, the Philippines). Front Microbiol. 2015. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boden R, Scott KM, Williams J, Russel S, Antonen K, Rae AW, et al. An evaluation of Thiomicrospira, Hydrogenovibrio and Thioalkalimicrobium: reclassification of four species of Thiomicrospira to each Thiomicrorhabdus gen. nov. and Hydrogenovibrio, and reclassification of all four species of Thioalkalimicrobium to Thiomicrospira. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1140–51. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brazelton WJ, Ludwig KA, Sogin ML, Andreishcheva EN, Kelley DS, Shen CC, Edwards RL, Baross JA. Archaea and bacteria with surprising microdiversity show shifts in dominance over 1,000-year time scales in hydrothermal chimneys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(4):1612–7. 10.1073/pnas.0905369107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trutschel LR, Kruger BR, Sackett JD, Chadwick GL, Rowe AR. Determining resident microbial community members and their correlations with geochemistry in a serpentinizing spring. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1182497. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1182497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen M, Perner M. A novel hydrogen oxidizer amidst the sulfur-oxidizing Thiomicrospira lineage. ISME J. 2015;9:696–707. 10.1038/ismej.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willems A, Busse J, Goor M, Pot B, Falsen E, Jantzen E, et al. Hydrogenophaga, a New Genus of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria That Includes Hydrogenophaga flava comb. nov. (Formerly Pseudomonas flava), Hydrogenophaga palleronii (Formerly Pseudomonas palleronii), Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava (Formerly Pseudomonas pseudoflava and “Pseudomonas carboxy do flava”), and Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis (Formerly Pseudomonas taeniospiralis). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1989;39:319–33. 10.1099/00207713-39-3-319. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ventosa A, de la Haba RR, Arahal DR, Sánchez-Porro C. Halomonas. In: bergey’s manual of systematics of archaea and bacteria. Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2021. p. 1–111. 10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01190.pub2.

- 52.Alibaglouei M, Trutschel LR, Rowe AR, Sackett JD. Complete genome sequence of Halomonas sp. strain M1, a thiosulfate-oxidizing bacterium isolated from a hyperalkaline serpentinizing system, Ney Springs. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2023;12:e00508–23. 10.1128/MRA.00508-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brazelton WJ, Schrenk MO, Kelley DS, Baross JA. Methane- and sulfur-metabolizing microbial communities dominate the Lost City Hydrothermal Field ecosystem. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6257–70. 10.1128/AEM.00574-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki S, Ishii S, Wu A, Cheung A, Tenney A, Wanger G, et al. Microbial diversity in the Cedars, an ultrabasic, ultrareducing, and low salinity serpentinizing ecosystem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:15336–41. 10.1073/pnas.1302426110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu X, Li M, Castelle CJ, Probst AJ, Zhou Z, Pan J, et al. Insights into the ecology, evolution, and metabolism of the widespread Woesearchaeotal lineages. Microbiome. 2018;6:102. 10.1186/s40168-018-0488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rouvière P, Mandelco L, Winker S. A detailed phylogeny for the Methanomicrobiales. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:363–71. 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suzuki S, Ishii S, Chadwick GL, Tanaka Y, Kouzuma A, Watanabe K, et al. A non-methanogenic archaeon within the order Methanocellales. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4858. 10.1038/s41467-024-48185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw 16S rRNA sequencing data analyzed in this study is available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information repository under the BioProject accession PRJNA1223160. Please note that the sequences amplified with the 341F and 805R primer set are referred to as ‘bacterial’ in this paper, but as ‘prokaryotic’ in the NCBI database. The sample metadata used to analyze beta diversity is included in the article and its additional files. The bioinformatic pipeline developed for this study is available on github: https://github.com/jampoa/16S-alpha–beta-div.