Abstract

Skin aging is a multifactorial biological process driven by the cumulative effects of oxidative stress, chronic low-grade inflammation, and progressive deterioration of barrier function. Among its pivotal regulatory nodes, the Vitamin D–Vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling axis acts as an integrative hub that senses and coordinates photic, redox, and metabolic cues to regulate immune homeostasis and structural integrity, thereby shaping the skin’s defensive and reparative capacity throughout aging. Disruption of this axis amplifies inflammaging, accelerates dermal and epidermal structural decline, and compromises cutaneous resilience against environmental insults. Phenotypic shifts in keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and T lymphocytes during aging are tightly linked to VDR-governed transcriptional programs and pathway crosstalk. Mechanistically, Nrf2-mediated antioxidant networks, Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signal interplay, stabilization of E-cadherin/β-catenin complexes, lipid metabolic remodeling, and reprogramming of immune tolerance collectively constitute the molecular basis through which Vitamin D mitigates skin aging. This review systematically delineates the critical role of the VDR axis in the onset and progression of skin aging and proposes its repositioning as a programmable molecular node for intervention, aiming to modulate inflammaging and maintain barrier homeostasis to slow the structural and functional decline of aging skin.

Keywords: Skin aging, Vitamin D, Oxidative stress, Inflammaging, Epidermal barrier function, Immune regulation

Introduction

The extension of human lifespan represents a major achievement of modern medicine and public health [1]. According to the United Nations’ 2024 World Population Prospects, the global population aged 65 years and older surpassed 850 million in 2024 and is projected to reach 1.6 billion by 2054, with its proportion rising from 10.3% to 15.5% of the global total [2]. Notably, by the late 2070 s, the number of elderly individuals is expected to exceed that of children under the age of 18 for the first time in history [2]. This profound demographic shift marks the advent of a new era characterized by population aging [3–5].Meanwhile, global average life expectancy has risen from 46.5 years in 1950 to 71.7 years in 2022, and is projected to reach 77.3 years by 2050 [2]. However, this increase in lifespan has not been paralleled by a commensurate improvement in quality of life. Mounting evidence indicates that gains in “healthy life expectancy” lag significantly behind total life expectancy, a disparity that is especially pronounced in the elderly population [6–10].

Aging is a progressive, multisystem degenerative process that begins in early adulthood and persists throughout the lifespan, ultimately contributing to a spectrum of functional disorders such as sarcopenia, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and skin aging [11–15]. As the largest organ of the human body, the skin serves not only as a barrier, defense, and sensory interface, but also as a key player in metabolic regulation. It constitutes the body’s first line of defense against the external environment, and as such, skin aging manifests with exceptional prominence [16–19]. Physiological studies have shown that skin aging is governed by both intrinsic factors (e.g., genetic background, hormonal fluctuations) and extrinsic factors (e.g., ultraviolet radiation, pollution, nutritional status) [20–22]. Characteristic manifestations include thinning of the stratum corneum, loss of elasticity, transepidermal water loss, sustained chronic inflammation, and impaired immune function [23–25].

The skin is composed of three primary layers—epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue—each possessing distinct structural and functional characteristics [26]. The epidermis is predominantly composed of keratinocytes, which function as a physical barrier and participate in immune surveillance [27]. The dermis is rich in fibroblasts, which produce extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as type I and III collagen, elastic fibers, proteoglycans, and structural glycoproteins, thereby endowing the skin with essential mechanical strength and elasticity [28]. Its dense vascular network not only supports nutrient delivery and metabolic exchange but also contributes to the maintenance of structural stability. The subcutaneous layer primarily consists of loose reticular connective tissue and adipose tissue; the latter serves as an energy reservoir, provides effective thermal insulation in cold environments, protects internal organs through mechanical cushioning, and connects to muscles and other supporting structures [29, 30]. Additionally, the skin harbors resident immune cells, pigment-producing melanocytes, and appendages such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands, rendering it not only a physical barrier but also a crucial interface for immune and metabolic regulation [31, 32]. With aging, cumulative alterations occur across all layers of this multilayered structure, resulting in impaired barrier integrity, diminished regenerative capacity, and increased susceptibility to environmental insults [33].

Clinically, skin aging is manifested by visible changes such as wrinkles, laxity, and hyperpigmentation [34]. These alterations can negatively impact body image, lower self-esteem, elevate depression and anxiety scores, and reduce overall life satisfaction [35–37]. Moreover, skin aging is often perceived as a visible marker of aging, eliciting gerontophobic emotions and social withdrawal [38]. Patients with pathologic cutaneous aging—particularly those with facial involvement—frequently exhibit heightened social anxiety, reduced self-evaluation, and subjective loneliness, with some developing body image disturbance [37]. Thus, the impact of skin aging extends beyond physiology, emerging as a critical determinant of psychological well-being and social functioning in the aging population. More importantly, the decline in barrier function and regenerative capacity renders aged skin more susceptible to infections, chronic pruritus, inflammatory dermatoses, and cutaneous neoplasms—all of which constitute major components of geriatric syndromes [39–42]. In this context of rapid global aging, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying skin aging and developing effective intervention strategies remain urgent challenges across dermatology, geriatric medicine, and public health.

Among various modifiable factors, nutritional status has gained increasing attention as a critical extrinsic determinant of skin health and aging [43, 44]. The skin is not only an essential organ for maintaining metabolic homeostasis but also serves as a central site for the synthesis and action of key nutrients, notably Vitamin D [45]. Vitamin D, traditionally recognized for its role as a fat-soluble hormone in maintaining systemic calcium–phosphate balance, also functions locally within the skin. It directly modulates keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, immune-inflammatory responses, antioxidant defenses, and barrier integrity, thus playing a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of skin aging [46–48]. Numerous clinical studies have confirmed that elderly individuals with low serum Vitamin D levels are more prone to exhibit aging-associated features such as xerosis, pruritus, increased wrinkling, and dyschromia, along with higher incidences of cutaneous infections and inflammatory dermatoses (e.g., senile eczema, psoriasis) [49–52].Emerging evidence further suggests a positive correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), underscoring its potential role in maintaining immune surveillance and cutaneous tumor defense [53].

Vitamin D has demonstrated multi-level regulatory effects in the clinical manifestations of skin aging. Its deficiency is not only a hallmark of cutaneous aging but also a potential trigger that accelerates the aging process. It is noteworthy that several studies have reported no association between genetically determined serum 25(OH)D levels and any phenotypic features of skin aging [54]. Moreover, clinical trials have shown that oral Vitamin D supplementation does not significantly improve disease severity, thereby challenging the hypothesis that systemic supplementation universally benefits the inflammation–remodeling axis in the skin [55]. In addition, practical limitations arise in contexts such as photoaging and photoprotection. For instance, topical calcitriol undergoes rapid photodegradation under UVA/UVB exposure, suggesting that Vitamin D is not intrinsically synergistic with phototherapy or sunlight, thereby complicating interpretations of its protective efficacy via topical delivery routes [56]. These conflicting or inconclusive findings indicate that the role of Vitamin D in skin aging is not unidirectional but rather context-dependent, shaped by dosage, local microenvironment, and dynamic regulation of molecular pathways. Therefore, it is crucial to systematically dissect and explore the molecular mechanisms through which Vitamin D influences skin aging. This review focuses on the core mechanistic roles of Vitamin D in skin aging, centering on three key pathways: modulation of oxidative stress, suppression of inflammatory responses, and maintenance of epidermal barrier function. We systematically delineate its molecular intervention networks and translational potential, aiming to provide a theoretical foundation and novel perspectives for precision nutritional interventions and preventive strategies against cutaneous aging.

Vitamin D metabolism and function

Vitamin D acquisition

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that exists predominantly in two forms: Vitamin D₂ (ergocalciferol) and Vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol) [57]. Vitamin D₃ can be synthesized in the skin upon exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation in the wavelength range of 290–315 nm, while both forms can also be obtained through dietary intake and intestinal absorption [58]. In the skin, Vitamin D₃ synthesis begins with the photolysis of 7-dehydrocholesterol (proVitamin D₃) in the plasma membrane of keratinocytes, forming preVitamin D₃ [59]. Under normal conditions, preVitamin D₃ undergoes spontaneous thermal isomerization to yield Vitamin D₃. However, excessive UV exposure leads to the formation of biologically inert isomers such as lumisterol and tachysterol [60]. Notably, approximately 90% of Vitamin D is derived from sunlight exposure, and its cutaneous synthesis is influenced by multiple factors including skin pigmentation, age, body mass index, sunscreen use, duration of exposure, and surface area exposed to sunlight [61, 62].

Orally ingested Vitamin D₂ and D₃ are primarily absorbed in the jejunum and ileum [63]. These compounds are typically integrated into mixed micelles formed with dietary fats and bile acids, although they may also be absorbed in the form of lipid droplets or vesicles [64, 65]. At pharmacological doses, Vitamin D can be absorbed via passive diffusion, whereas under physiological conditions, absorption predominantly depends on specific transport proteins such as scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1), Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 (NPC1L1), and cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) [66]. Once absorbed, Vitamin D is incorporated into chylomicrons via an apolipoprotein B (ApoB)-dependent pathway and transported into systemic circulation through the lymphatic system [67].Recent studies have also shown that Vitamin D can be exported via ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) into high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles, thereby entering the bloodstream as an HDL-bound lipophilic molecule [68].

Of particular interest, recent advances have revealed that the intestinal microbiome plays a crucial role in modulating Vitamin D absorption. Certain probiotic strains have been shown to enhance Vitamin D bioavailability by regulating the expression of intestinal transporters and improving gut barrier function [69–73]. In addition, Vitamin D can be absorbed via mixed micelles formed with bile acids and taken up through transmembrane transporters such as SR-BI and NPC1L1. In both human Caco-2 cell lines and murine models, inhibition of these pathways reduces Vitamin D₃ uptake and tissue distribution [66]. Further in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that bile acids, particularly taurocholic acid derivatives, enhance the oral bioavailability of Vitamin D by stimulating bile acid secretion and increasing bile hydrophobicity [74]. Interestingly, certain probiotic strains—such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) and Lactobacillus plantarum (LP)—have been shown to upregulate VDR expression and activity in host cells, leading to increased circulating levels of 25(OH)D [75, 76]. The loss of anti-inflammatory benefits of probiotics in VDR-deficient mice further supports the essential role of the “probiotic–VDR axis” in maintaining mucosal immune homeostasis [75]. The integration of Vitamin D absorption and VDR signaling provides a mechanistic link to aging-associated outcomes. In elderly individuals, lower serum 25(OH)D levels are correlated with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and systemic inflammation, while VDR dysfunction is associated with impaired bone metabolism and aging-related phenotypes [77, 78]. However, in generally healthy older populations, additional Vitamin D supplementation does not consistently reduce fracture risk, highlighting the importance of optimizing absorption efficiency and achieving adequate serum levels rather than excessive dosing [79]. Dietary components also have a marked influence on Vitamin D absorption. Foods rich in monounsaturated fatty acids have been shown to facilitate its uptake, whereas excessive intake of polyunsaturated long-chain fatty acids or dietary fiber may inhibit absorption [80].Although oral intake alone typically accounts for only 10–20% of the body’s Vitamin D requirements, dietary supplementation remains an important non-pharmacological intervention for individuals with limited sun exposure or impaired cutaneous synthesis [81].

Vitamin D metabolic pathway

Vitamin D₂ or D₃ can be obtained either through photochemical synthesis or dietary absorption. Once synthesized in the skin, Vitamin D₃ requires specific transport and hydroxylation processes for biological activation. The newly formed Vitamin D₃ diffuses passively from keratinocytes into dermal capillaries, where it rapidly binds to the high-affinity Vitamin D-binding protein (VDBP) in plasma, forming a VDBP–Vitamin D₃ complex that enters systemic circulation [82, 83]. In parallel, dietary Vitamin D (both D₂ and D₃) is incorporated into chylomicrons along with triglycerides, phospholipids, and cholesterol within intestinal epithelial cells. These chylomicrons are then released basolaterally via exocytosis into mesenteric lymphatics and ultimately reach systemic circulation via the thoracic duct [82, 84]. Chylomicron remnants are subsequently taken up by hepatocytes through receptor-mediated endocytosis, completing the initial transport and hepatic targeting of dietary Vitamin D [60, 85].

Upon entering circulation, Vitamin D undergoes two sequential hydroxylation steps catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes to become biologically active. The first hydroxylation occurs in the liver, where endoplasmic reticulum–localized CYP2R1 catalyzes the conversion of Vitamin D to 25-hydroxyVitamin D [25(OH)D], a key intermediate in the activation cascade [84, 86]. CYP2R1, owing to its high substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency demonstrated across multiple studies, is considered one of the principal enzymes mediating 25-hydroxylation of Vitamin D in vivo [87, 88]. Other enzymes, including CYP27A1, CYP3A4, and CYP2J3, may also contribute in tissue-specific contexts to maintain 25-hydroxylation homeostasis [89].

25(OH)D is the major circulating form of Vitamin D, characterized by a long half-life and stable serum concentration. As such, it is widely used as a reliable biomarker for assessing systemic Vitamin D status [90, 91]. However, the distribution of Vitamin D and its metabolites is tissue-specific, and local concentrations or biological activity may not correlate directly with serum levels, indicating that serum 25(OH)D alone may not fully reflect systemic Vitamin D sufficiency in all contexts [92, 93]. The 25(OH)D–VDBP complex is filtered by renal glomeruli and taken up into proximal tubule cells via endocytosis mediated by the megalin/cubilin receptor complex. There, it undergoes a second hydroxylation step [94, 95]. This reaction is catalyzed by mitochondrial 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1), producing 1α,25-dihydroxyVitamin D₃ [1α,25(OH)₂D₃], the biologically active form of Vitamin D [94, 95]. In contrast, CYP24A1 catalyzes the catabolic conversion of 25(OH)D and 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ to inactive metabolites, namely 24,25(OH)₂D₃ and 1,24,25(OH)₃D₃, respectively [96]. These hydroxylation steps are tightly regulated by systemic hormones. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) upregulates CYP27B1 and downregulates CYP24A1 to promote active Vitamin D synthesis, whereas fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) exerts opposing effects [97, 98].Additionally, serum phosphate, calcium levels, and 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ itself participate in feedback regulation, creating a dynamic and complex endocrine network [94].

Notably, CYP27B1 is also expressed in extra-renal tissues such as the placenta and prostate, where it facilitates local synthesis of 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ to modulate cellular functions via paracrine or autocrine signaling [96, 99]. This intracrine pathway operates independently of PTH and is instead driven by local inflammatory mediators such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [96, 99]. Ultimately, 1α,25(OH)₂D₃, bound to VDBP, enters target cells and binds to its nuclear receptor, the Vitamin D receptor (VDR). The VDR forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR), translocates to the nucleus, and regulates the transcription of genes involved in calcium-phosphate homeostasis, bone formation, immune modulation, and cell cycle control [84, 94, 100, 101]. Following its physiological action, 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ is further catabolized by CYP24A1 into final metabolites such as calcitroic acid and 1α,25(OH)₂D₃−26,23 lactone, which are subsequently excreted in bile or urine [96, 102].(Fig. 1).

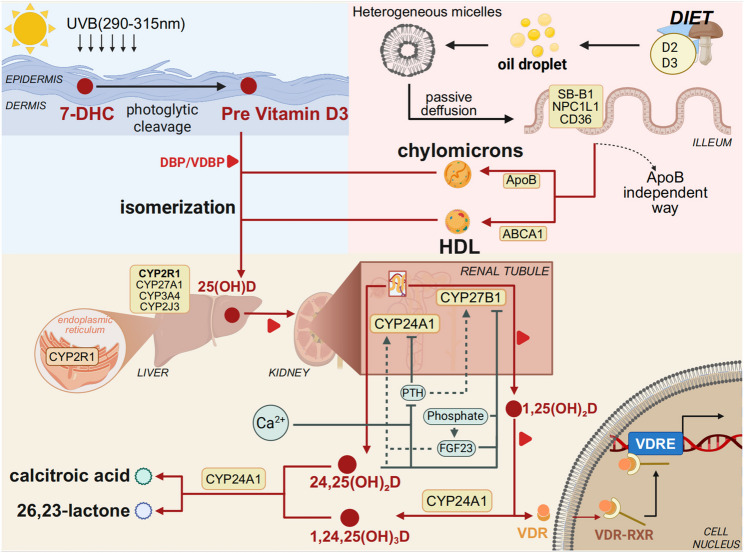

Fig. 1.

Obtention and metabolism of Vitamin D The processes of Vitamin D synthesis, absorption, and metabolism are closely interconnected. Upon exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation, the skin converts 7-dehydrocholesterol into Vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol). In addition, Vitamin D₂ or D₃ can be obtained from dietary sources, where these forms are absorbed in the small intestine along with dietary lipids and incorporated into chylomicrons, which enter the lymphatic system and subsequently the bloodstream. Regardless of whether Vitamin D is endogenously synthesized or exogenously acquired, it is first hydroxylated in the liver by 25-hydroxylases (e.g., CYP2R1) to form 25-hydroxyVitamin D [25(OH)D], the major circulating form. This is subsequently hydroxylated in the kidney by 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) to generate 1,25-dihydroxyVitamin D [1,25(OH)₂D], the biologically active form, which exerts its effects by binding to the Vitamin D receptor (VDR) to regulate a wide range of physiological processes

Endocrine and paracrine signaling of Vitamin D in the skin

The systemic endocrine axis of Vitamin D centers on hepatic 25-hydroxylation and renal 1α-hydroxylation. In the liver, 25-hydroxylation is primarily catalyzed by CYP2R1, producing [25(OH)D] [90]. Renal CYP27B1 is upregulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH) and negatively regulated by fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) and 1,25(OH)₂D₃ [103]. In contrast, FGF23 induces the expression of CYP24A1, promoting the catabolic inactivation of both 1,25(OH)₂D₃ and 25(OH)D, whereas PTH suppresses CYP24A1 expression, thereby attenuating their degradation [104, 105]. Meanwhile, skin cells also engage in paracrine and autocrine regulation. Studies have shown that keratinocytes, melanocytes, and immune cells express CYP27B1 and related hydroxylases, enabling local synthesis of active Vitamin D metabolites in response to UVB irradiation or inflammatory stimuli [106, 107]. These metabolites act through the Vitamin D receptor (VDR) in adjacent cells to finely modulate barrier integrity, immune tolerance, and antioxidant responses.

Recent studies have revealed that CYP11A1-mediated metabolism of Vitamin D and lumisterol in the skin generates novel secosteroids, which not only activate the Vitamin D receptor (VDR) but also bind to other nuclear receptors such as RORγ, AHR, and LXR, exhibiting multi-target biological effects [108]. These actions include activation of NRF2 and p53 pathways, inhibition of NF-κB/IL-17 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, thereby preserving skin integrity and physiological homeostasis. Moreover, experimental evidence demonstrates that calcitriol enhances the expression of multiple tight junction proteins—including claudin-4/7, occludin, and ZO-1—via activation of PI3K/Akt and atypical PKC (aPKC) signaling pathways, thereby significantly increasing transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) and reinforcing barrier homeostasis [109]. In addition, CYP24A1-mediated inactivation of Vitamin D has also been implicated as a critical factor in pathological skin processes. In hypertrophic scar–derived keratinocytes, CYP24A1 expression is markedly upregulated, promoting the transcription of pro-fibrotic genes; pharmacological inhibition of CYP24A1 reduces the expression of fibrosis-associated markers [110]. Taken together, while the endocrine axis determines systemic Vitamin D status, the cutaneous paracrine/autocrine network confers contextual and tissue-specific regulation. By upregulating NRF2, suppressing NF-κB/IL-17 signaling, and enhancing tight junction protein expression, this local network integrates oxidative stress, inflammation, and barrier remodeling, ultimately driving skin aging–associated processes.

The biological effects of activated 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ are mediated via its ligand-activated nuclear receptor, the VDR, which is broadly expressed across tissues and particularly enriched in skin cells. As a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily, VDR initiates transcriptional cascades upon ligand binding, serving as the central hub of Vitamin D signaling. The following section will explore the structural features and regulatory mechanisms of VDR, laying the molecular groundwork for understanding its roles in various skin cell types.

The function of the vitamin D receptor

The VDR is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and functions as a steroid hormone-like, ligand-dependent transcription factor [111]. Comprising 427 amino acids, VDR exhibits a highly conserved molecular structure characterized by a canonical DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a ligand-binding domain (LBD) [112]. The function of VDR depends not only on ligand binding with 1,25-dihydroxyVitamin D₃ but also on its dynamic interactions with coactivators (e.g., SRC-1, DRIP205/MED1), epigenetic enzymes (e.g., HDACs, LSD1, PRMT5), and corepressor/de-repressor complexes (e.g., NCoR/SMRT), which are recruited and reorganized in a ligand-inducible manner to mediate precise gene regulation [113–115]. Upon activation, VDR typically forms a heterodimer with RXR, and this complex binds with high affinity to Vitamin D response elements (VDREs), typically of the DR3 type(a direct repeat of the hexameric core sequence separated by three nucleotides), located in promoters or enhancers of target genes via a zinc finger–containing DNA-binding motif [116].The VDR–RXR complex then utilizes its AF-2 domain to recruit coactivators/corepressors and chromatin remodeling enzymes, orchestrating precise transcriptional programs involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, immune homeostasis, antioxidant defense, and barrier function [117–120].Given that the skin is a frontline environmental sensor chronically exposed to UV radiation, pathogens, and oxidative stress, the ability of VDR to bridge environmental cues and gene expression is particularly critical in this context.

Expression and functions of the vitamin D in the skin

Active Vitamin D exerts multilayered regulatory effects in the skin through its nuclear receptor, VDR, and these effects exhibit pronounced cell-type specificity. VDR is widely expressed across various cell types in both the epidermis and dermis, including keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and T cells. Variations in VDR expression levels, ligand responsiveness, and downstream coactivator recruitment collectively determine the cell-specific physiological functions mediated by Vitamin D signaling. In the following sections, we will delineate the expression profiles and functional mechanisms of the Vitamin D–VDR signaling axis distinct cutaneous cell types, thereby revealing its diverse biological roles in maintaining skin homeostasis and responding to aging-related stressors.

Keratinocytes

VDR displays marked cell type–specific expression patterns in the skin, suggesting that it may exert distinct regulatory functions across different cell populations [121, 122]. Among these, keratinocytes exhibit the highest levels of VDR expression, particularly within the basal and spinous layers of the epidermis [47]. Studies have shown that VDR deficiency severely impairs epidermal differentiation, leading to aberrant keratinization and disorganized expression of differentiation markers such as K1, K10, and involucrin. This is accompanied by increased transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and compromised barrier function [123]. In undifferentiated keratinocytes, VDR primarily regulates downstream target genes through interactions with the mediator (MED) complex [124].In more differentiated keratinocytes, VDR function is predominantly mediated via coactivators of the steroid receptor coactivator (SRC) family, particularly SRC2 and SRC3 [125]. MED1 is mainly localized to basal layer cells, whereas SRC3 is enriched in the granular layer, forming a complementary expression pattern [48]. Loss of MED1 significantly enhances keratinocyte proliferation and disrupts hair follicle cycling, while SRC3 deficiency impairs lipid metabolism–associated structures such as glucosylceramides and lamellar bodies, as well as 1,25(OH)₂D-induced ductin expression—phenotypes that partially mimic VDR deficiency [125–128]. Different VDR target genes exhibit coactivator-specific dependencies: for example, K1, K10, and involucrin are more dependent on DRIP205, whereas loricrin, filaggrin, and cathelicidin require SRC3 for optimal transcriptional activation [117, 129]. Thus, the stepwise recruitment of distinct coactivators by VDR during keratinocyte differentiation—from early proliferative regulation to terminal differentiation—constitutes a dynamic transcriptional control mechanism essential for maintaining epidermal structural integrity and functional homeostasis.

Melanocytes

Melanocytes are specialized epidermal cells derived from the neural crest, predominantly located in the basal layer of the skin, where they synthesize and transfer melanin to maintain pigment homeostasis in the skin, hair, and iris [130]. Early studies have demonstrated stable expression of VDR in normal human epidermal melanocytes (NHEMs), with its levels regulated by 1,25(OH)₂D₃, suggesting that active Vitamin D may exert distinct physiological roles in pigment cells via the VDR signaling pathway [131, 132]. VDR is expressed in both normal melanocytes and benign nevus cells; however, its expression progressively declines during the transition from benign nevi to dysplastic nevi and ultimately to melanoma. This trend implicates the loss of VDR signaling as a potential marker of melanocytic malignant transformation [133].

VDR plays a critical regulatory role in maintaining melanocyte homeostasis and photoprotection, particularly under ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure. Using a melanocyte-specific VDR knockout mouse model, Chagani et al. found that VDR deficiency significantly reduced the number of melanocytes following UVB exposure, as evidenced by decreased TYRP1-positive cells and diminished Fontana-Masson staining in the skin [134]. This phenomenon may originate at the melanoblast stage, as the proportion of PAX3-positive precursor cells was also significantly reduced in VDR-deficient mice, suggesting that VDR exerts essential functions during early melanocyte development [134]. Furthermore, after acute UVB exposure, melanocytes in VDR-deficient mice exhibited reduced proliferative activity (PCNA⁺/TYRP1⁺), increased numbers of cells positive for the DNA damage marker CPD, and a significantly elevated apoptotic index (TUNEL⁺/TYRP1⁺), highlighting the protective role of VDR in mitigating UVB-induced genotoxic stress and sustaining melanocyte viability [134]。.

Under H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress, the expression levels of β-catenin and its downstream effector CDH3 are markedly reduced in melanocytes, thereby weakening their antioxidant responses [135].Vitamin D treatment reverses this suppression by promoting Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK3β, thereby preventing β-catenin degradation and activating downstream transcriptional programs. This, in turn, significantly upregulates Nrf2 and MITF expression, contributing to redox homeostasis and promoting melanocyte differentiation and migration [135]. Notably, β-catenin silencing abolishes the protective effects of Vitamin D, leading to increased ROS levels, impaired migration, and elevated apoptosis, indicating that β-catenin activation is indispensable for Vitamin D–mediated cytoprotection. These findings uncover a pivotal crosstalk between Vitamin D signaling and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in melanocytes and underscore its therapeutic potential in managing oxidative stress and skin aging.

Additionally, Vitamin D inhibits activation of mitogenic pathways such as PI3K–Akt and RAS–ERK, which are frequently hyperactivated in melanoma [136]. Moreover, several polymorphic sites in the VDR gene, such as FokI and TaqI, have been associated with increased melanoma risk and functional variability in VDR activity, suggesting a genetic basis for individual susceptibility to Vitamin D regulation [137, 138]. Collectively, these findings emphasize the central role of the VDR signaling axis in constraining aberrant melanocyte proliferation, with its progressive dysfunction potentially serving as a key determinant in the malignant transformation of benign nevi to melanoma.

Langerhans cells

Vitamin D exerts multilayered immunomodulatory effects in the skin, particularly by regulating Langerhans cells (LCs), the principal antigen-presenting cell subset in the epidermis, thereby fine-tuning mucosal immune homeostasis. LCs express high levels of VDR, and their phenotype and functional state are profoundly influenced by local concentrations of 1,25(OH)₂D₃ [139].Studies have shown that 1,25(OH)₂D₃ significantly suppresses the expression of LC surface maturation markers (such as CD80, CD86, CD40, and MHC II) as well as the chemokine receptor CCR7, thereby reducing their migratory capacity to draining lymph nodes and their ability to activate naïve T cells [140]. This tolerogenic shift is dependent on VDR-mediated transcriptional programs, involving suppression of NF-κB signaling and upregulation of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, which collectively promote the development of a “semi-mature” tolerogenic LC phenotype capable of inducing Foxp3⁺ regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion and maintaining local immune homeostasis [141].

Beyond LCs, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ also modulates dermal CD14⁺ dendritic cells (dDCs), enhancing their CCR7-mediated migration and partial activation without promoting inflammatory cytokine release, and instead favoring the induction of IL-10⁺ Tr1-type Tregs [142]. In contrast, LCs under 1,25(OH)₂D₃ stimulation tend to induce Foxp3⁺ classical Tregs via the TGF-β/SMAD3 signaling pathway [142, 143]. Although 1,25(OH)₂D₃ does not significantly increase TGF-β expression in LCs, the inherently high basal levels of TGF-β in LCs enable them to retain their Treg-inducing capacity [142, 144]. Functional blockade experiments have further validated the critical role of the TGF-β/SMAD3 axis in this process [145, 146]. Under 1,25(OH)₂D₃ stimulation, LCs selectively upregulate inhibitory receptors such as ILT3 and ILT4, while downregulating maturation markers such as CD83, thereby enhancing their tolerogenic profile. Compared with dDCs, LCs show weaker IL-10 induction capacity, indicating a preference for TGF-β–driven immunomodulatory pathways [142].

The functional reprogramming of LCs by 1,25(OH)₂D₃ is highly dependent on the integration of skin microenvironmental cues. UVB exposure induces keratinocytes to synthesize 1,25(OH)₂D₃, which in turn promotes the secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β, thereby paracrinally shaping LC immunological behavior [139]. In VDR-deficient mice, LCs display a hypermature phenotype characterized by enhanced antigen presentation and proinflammatory features, providing additional evidence that 1,25(OH)₂D₃ serves as an “immune brake” in the cutaneous mucosal environment [147, 148]. This bidirectional regulatory mechanism underscores the “double-edged sword” nature of Vitamin D in balancing immunosuppression and immune homeostasis.

T cell

In the cutaneous immune system, T cells play a pivotal role in maintaining protective immunity and barrier homeostasis, as well as in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune skin disorders such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo [149–152]. Extensive studies have demonstrated that active Vitamin D and its receptor, VDR, serve as important regulators of T cell differentiation, functional programming, and immune homeostasis. Studies in VDR-deficient mice and human individuals with VDR mutations reveal that CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cell numbers remain largely unaffected and that natural CD4⁺FoxP3⁺ Tregs develop normally, suggesting that 1,25(OH)₂D₃/VDR is not essential for conventional T cell lineage development [153, 154]. However, further investigations reveal that VDR signaling is indispensable for the development and function of certain tissue-specific or unconventional T cell subsets, including invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells and CD8αα⁺ intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) [155, 156]. These subsets are primarily enriched at mucosal barrier sites such as the gut and skin, where they are essential for immune surveillance, tolerance induction, and barrier repair. Their reliance on VDR suggests that Vitamin D may mediate the immune adaptation of barrier-associated T cell populations through modulation of local microenvironmental signals.

Under steady-state conditions, naïve T cells express minimal or undetectable levels of VDR; however, upon activation via antigenic stimulation, VDR expression is rapidly upregulated [157–159]. This dynamic regulation allows active Vitamin D to intervene during the later stages of T cell activation, where VDR binds to Vitamin D response elements (VDREs) in the genome, reshaping the T cell transcriptional landscape and modulating cytokine expression, migratory behavior, and metabolic programming [160–162].

In CD4⁺ T helper cells, the 1,25(OH)₂D₃–VDR axis suppresses Th1/Th17-associated cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-17 A, and IL-22, while upregulating Th2-related cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, thus promoting a functional shift toward Th2 polarization [163–165]. This cytokine profile remodeling confers anti-inflammatory effects in several T cell–mediated autoimmune disease models, including experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), collagen-induced arthritis, and imiquimod-induced psoriasiform dermatitis, supporting the clinical potential of Vitamin D as an immunomodulatory agent in skin disease therapy [166, 167]. Additionally, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ promotes the expansion and functional enhancement of regulatory T cells (Tregs), not only by directly upregulating FoxP3 and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, but also by inducing a tolerogenic phenotype in dendritic cells, thereby indirectly facilitating Treg induction [168–173].Furthermore, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ inhibits the mTORC1 pathway and activates fatty acid oxidation, creating a favorable metabolic milieu for Treg differentiation—a combined epigenetic–metabolic regulatory mechanism that is emerging as a central feature of Vitamin D–mediated immunomodulation [174, 175].

In summary, Vitamin D, through its receptor VDR, exerts highly cell-type–specific regulatory effects across multiple skin cell populations(Fig. 2). Notably, these mechanisms not only collectively safeguard cutaneous structural and immunological integrity, but also orchestrate a dynamic regulatory network in response to exogenous stimuli (e.g., UV radiation, oxidative stress) and endogenous inflammation. With aging and the accumulation of chronic inflammation, this regulatory network becomes progressively impaired, manifesting as diminished antioxidant barrier capacity, enhanced cellular senescence phenotypes, and persistent low-grade inflammation, ultimately driving degenerative changes in epidermal structure and function. Accordingly, the following sections will focus on the mechanistic roles of Vitamin D in modulating oxidative stress responses, inflammatory signaling, and the deceleration of barrier aging in the skin, with the aim of elucidating its multilayered regulatory potential in cutaneous aging and pathology, and providing a theoretical foundation for future clinical intervention strategies.

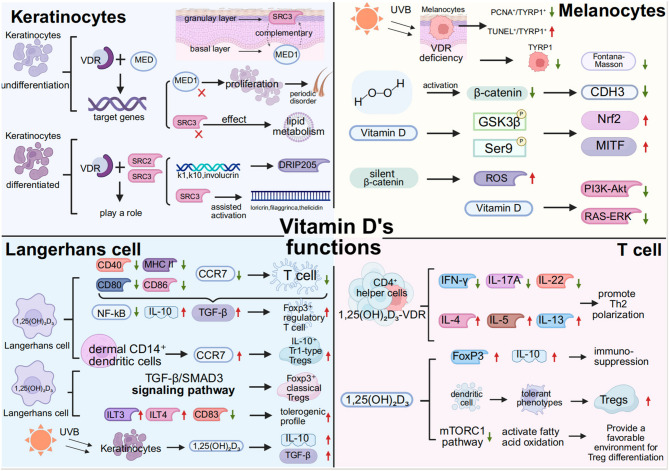

Fig. 2.

Molecualr mechanisms of Vitamin D action across four major skin cell populations In keratinocytes, active Vitamin D binds to its nuclear receptor VDR and subsequently forms a complex with the transcriptional coactivator MED1/DRIP205, thereby facilitating the transcription of target genes encoding barrier-associated structural proteins and antimicrobial peptides. Alternatively, VDR can interact with SRC2 and SRC3, engaging in an “assisted activation” process that jointly regulates keratinocyte differentiation and the maintenance of their functional integrity。In Langerhans cells, 1,25(OH)₂D₃, acting through VDR signaling, downregulates the expression of maturation markers CD80, CD86, CD40, and MHC II, as well as the chemokine receptor CCR7, thereby impairing their migration to draining lymph nodes and diminishing their ability to prime naïve T cells. This shift promotes the acquisition of a “tolerogenic phenotype.” In addition, Vitamin D can act on dermal CD14⁺ dendritic cells, where CCR7 upregulation facilitates the induction of IL-10⁺ Tr1-type regulatory T cells. Furthermore, Vitamin D drives the generation of Foxp3⁺ classical Tregs via the TGF-β/SMAD3 signaling pathway. By promoting the expression of ILT3, ILT4, CD83, IL-10, and TGF-β, Vitamin D plays a pivotal role in orchestrating immunosuppression and immune polarization. Following acute UVB exposure, melanocytes in VDR-deficient mice exhibit a marked reduction in proliferative activity (PCNA⁺/TYRP1⁺), accompanied by an increased number of CPD-positive cells, indicative of heightened DNA damage, and a significantly elevated apoptotic rate (TUNEL⁺/TYRP1⁺). Vitamin D, by promoting phosphorylation of GSK3β at the Ser9 residue, inhibits its repression of β-catenin–dependent transcriptional programs, thereby markedly inducing the expression of Nrf2 and MITF. These transcription factors respectively mediate the maintenance of redox homeostasis and regulate melanocyte differentiation and migration. Furthermore, Vitamin D can suppress the activation of canonical mitogenic pathways, including PI3K–Akt and RAS–ERK, thereby exerting a protective role against melanomagenesis.In CD4⁺ T helper cells, the 1,25(OH)₂D₃–VDR signaling pathway suppresses the expression of Th1/Th17-associated cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-17 A, and IL-22, while upregulating Th2-associated cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, thereby promoting a functional shift toward Th2 polarization. In addition, Vitamin D enhances the expression of FoxP3 and IL-10 to exert immunosuppressive effects. It can also inhibit the mTORC1 signaling pathway and activate fatty acid oxidation, creating a favorable metabolic environment for Treg differentiation

Oxidative stress in skin aging: role of vitamin D

As the body’s foremost barrier to the external environment, the skin is among the most heavily assaulted tissues by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [176, 177]. Oxidative stress is one of the earliest recognized and most fundamental drivers of cutaneous aging, orchestrating a continuum of cellular damage, inflammatory amplification, and extracellular matrix degradation. The persistent accumulation of ROS—arising from endogenous sources (e.g., mitochondrial leakage, enzymatic reactions) and exogenous insults (e.g., ultraviolet radiation, pollutants, tobacco)—can overwhelm the antioxidant defense threshold, triggering widespread oxidative damage targeting proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. This leads to disruption of cellular homeostasis and accelerates the aging process [178–182].

In the epidermis, ROS induce oxidative DNA lesions—including 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) formation, mitochondrial DNA damage, and telomere attrition—activating the p53-p21 pathway and leading keratinocytes toward cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [183, 184]. In the dermis, ROS activate signaling cascades such as AP-1 and NF-κB, upregulating matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9), thereby accelerating type I and III collagen degradation. This is accompanied by fibroblast phenotypic shifts and diminished collagen synthesis, culminating in dermal laxity and loss of tensile integrity [185, 186]. Beyond direct cellular damage, oxidative stress intensifies aging via “inflammaging”—a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state. ROS act as secondary messengers to activate inflammasomes such as NLRP3, promoting the release of IL-1β and IL-18, and fostering the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). This not only disrupts neighboring cells but also perpetuates a feedforward loop of oxidative stress, inflammation, and aging [187–189].

Emerging evidence indicates that 1,25-dihydroxyVitamin D₃ (1,25(OH)₂D₃) not only regulates calcium homeostasis and epidermal differentiation but also orchestrates antioxidant defense programs across diverse skin cell types via its nuclear receptor VDR. Mechanistically, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ facilitates the formation of VDR–RXR heterodimers, which are recruited to antioxidant response elements (AREs), inducing Nrf2 and its downstream targets—including HO-1, NQO1, and SOD2—and thereby enhancing ROS scavenging capacity [190, 191].

In keratinocytes, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ suppresses Nigericin-induced ROS production by activating antioxidant pathways such as NRF2–HO-1, thereby inhibiting NLRP1 inflammasome activation in Nigericin-stimulated normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) [192]. Consistent with previous evidence, NADPH oxidases—particularly NOX1—constitute the predominant source of ROS in keratinocytes under UVB irradiation [193]. These findings suggest that the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Vitamin D may be mediated, at least in part, through the suppression of NOX-dependent ROS generation. NOX1 activation exhibits a biphasic pattern post-UVB exposure, implicating it in DNA damage signaling and cell fate decisions [193].It is plausible that 1,25(OH)₂D₃ mitigates UVB-induced enzymatic ROS production by dampening NOX activity. While earlier studies indicated that 1,25(OH)₂D₃ exerts photoprotective effects independently of the glutathione system—primarily by inducing metallothionein expression for free radical scavenging [194]. Recent findings reveal its ability to upregulate structural genes such as glutathione S-transferases, thereby enhancing GSH metabolism and cellular detoxification across multiple cell types [195]. In melanocytes, Vitamin D inactivates GSK-3β, stabilizing β-catenin and promoting its nuclear translocation, thereby activating MITF and CDH3 to enhance melanogenesis and cell motility. This pathway synergistically engages β-catenin and Nrf2 to induce HO-1, conferring robust protection against H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress, including reduced apoptosis, attenuated lipid peroxidation, and restored antioxidant enzyme activities. These protective effects are abrogated upon β-catenin silencing or VDR deletion, underscoring the pathway’s dependency and essentiality [135]。.

Furthermore, 1,25(OH)₂D₃ enhances p53-mediated DNA repair responses to UVB-induced photodamage, attenuating oxidative lesions such as 8-OHdG and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs), and preserving genomic integrity [196]. UV-induced poly(ADP-ribose) (pADPr) accumulation via PARP1 activation is also significantly suppressed by 1,25(OH)₂D₃ through ERK dephosphorylation, ultimately reducing DNA damage [196]. Recent studies show that individuals with reduced or mutated VDR expression exhibit elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and decreased GSH/GSSG ratios in the skin, indicative of impaired antioxidant capacity and reaffirming the centrality of VDR signaling in maintaining redox homeostasis.

Through a VDR-dependent transcriptional network, multifaceted ROS detoxification pathways, and mitochondrial preservation, Vitamin D orchestrates a coordinated antioxidant barrier within the skin. This defense is critical for stress adaptation, barrier integrity, and photoprotection, providing a molecular rationale for the preventive and therapeutic applications of Vitamin D in skin aging, pigmentary disorders, and photo-induced dermatoses(Fig. 3).

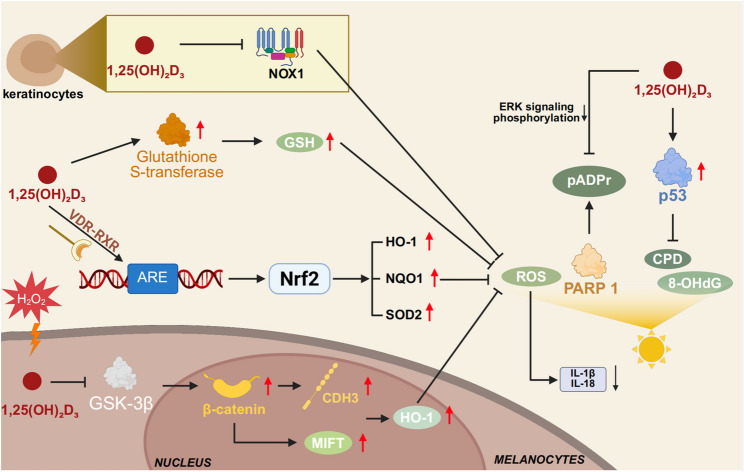

Fig. 3.

Regulatory mechanisms of Vitamin D in oxidative stress pathways of skin cells Vitamin D, through VDR-mediated transcriptional regulation, activates the Nrf2 pathway, thereby inducing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1, reducing NOX1 activity, diminishing ROS production, and suppressing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and IL-18. In parallel, it modulates GSH metabolism to enhance detoxification capacity. Moreover, Vitamin D promotes DNA repair and inhibits the formation of oxidative damage markers, working synergistically with the Nrf2 pathway to strengthen cellular antioxidant defenses. Collectively, these processes establish a multilayered barrier against oxidative stress in the skin, effectively mitigating oxidative injury

Inflammation and immunosenescence: vitamin D as a modulator

As the body’s primary barrier against the external environment, the skin undergoes not only structural deterioration during aging but also exhibits a pronounced state of chronic, low-grade, and persistent inflammation, known as inflammaging [197]. This process results from the interplay between immune senescence and sustained stress responses, and is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, persistent activation of inflammatory signaling pathways, and functional remodeling of immune cells [198]. Such an inflammatory milieu not only exacerbates the structural damage to both the epidermis and dermis, but also establishes a pro-aging microenvironment that underlies the pathogenesis of various age-related cutaneous disorders.

At the intracellular signaling level, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including JNK and p38, have been identified as central transducers of inflammatory signaling [199]. Interestingly, the VDR/RXR signaling axis exhibits substantial crosstalk with the MAPK pathways at multiple levels. This interaction may manifest as either synergistic activation or functional inhibition, with its precise effects being modulated by the nature of external stimuli, cellular context, and response dynamics [200, 201]. Accumulating evidence indicates that Vitamin D exerts its anti-inflammatory effect in part by inducing MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1), thereby suppressing p38 MAPK activation and inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in monocytes [202]. In fibroblasts, Vitamin D₃ supplementation has been shown to block the p38 MAPK pathway, thereby reducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 that are associated with the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [203]. A similar mechanism has been observed in endothelial cells, where 1,25(OH)₂D₃ attenuates inflammatory activation and p38 MAPK signaling, thus protecting against apoptosis and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators [204]. 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ facilitates the transcriptional activation of MKP5 by promoting the binding of the VDR/RXR heterodimer to the VDRE within the MKP5 promoter region [205].Building on this, 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ not only regulates downstream MAPK cascades via MKP5 upregulation but also interacts with transcription factors such as NF-κB, NFAT, and the glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) through its VDR/RXR complex, orchestrating a multi-level anti-inflammatory response。.

Experimental data have confirmed that activation of VDR suppresses NF-κB signaling and transcriptional activity in various skin cell types, including keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts, melanocytes, and cutaneous dendritic cells [206–209]. NF-κB comprises a family of ubiquitously expressed transcription factors that play a central role in inflammatory regulation, typically functioning as heterodimers. Under resting conditions, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm through binding with its inhibitory protein IκB, thus remaining in an inactive state [210]. Upon stimulation by bacterial products, pro-inflammatory cytokines, or cellular stress signals, the IκB kinase complex (IKK) becomes activated, leading to phosphorylation and ubiquitination of IκB, followed by its degradation via the proteasome pathway [211, 212]. This process liberates NF-κB dimers, enabling their nuclear translocation and subsequent binding to target gene promoters, thereby activating transcription of a broad array of inflammation-related genes—including pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β), anti-apoptotic molecules (e.g., Bcl-xL), and inflammatory enzymes (e.g., cyclooxygenase-2, COX-2)—ultimately contributing to immune defense, cell survival, and amplification of inflammatory responses [211, 212]. In keratinocyte-based experiments, calcipotriol was shown to elevate IκBα levels and inhibit its IL-17 A-induced degradation, thereby reducing the expression of downstream NF-κB target genes such as IL-8 and human β-defensin 2 (HBD2) [213]. Furthermore, in a human melanoma cell model established by Janjetovic et al., treatment with 1,25(OH)₂D₃ or 20(OH)D₃ significantly inhibited nuclear translocation and DNA-binding activity of the p65 subunit of NF-κB, along with a marked reduction in NF-κB–dependent reporter gene expression [214]. Notably, early studies demonstrated that 1α,25(OH)₂D₃ could inhibit the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB in human MRC-5 fibroblasts without preventing the nuclear translocation of its p50 or p65 subunits. This partial inhibition required de novo protein synthesis, suggesting the involvement of induced factors that interfere with NF-κB–DNA interactions [215]. Similar findings in epidermal keratinocytes indicate that active Vitamin D analogues reduce NF-κB DNA-binding activity, accompanied by IκBα upregulation and partial inhibition of subunit translocation—supporting the presence of a subunit-translocation–independent suppression mechanism in skin cells [207, 216]. Thus, Vitamin D appears to exert anti-inflammatory effects in the skin primarily through inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB pathway activation and DNA-binding activity. In addition, Vitamin D and its derivatives have been implicated in anti-inflammatory modulation via other signaling pathways, including JAK-STAT3, Nrf2-p53, COX-2/PGE₂, and NFAT [217–220]. Whether these pathways confer comparable anti-inflammatory effects within skin cells remains to be elucidated(Fig. 4).

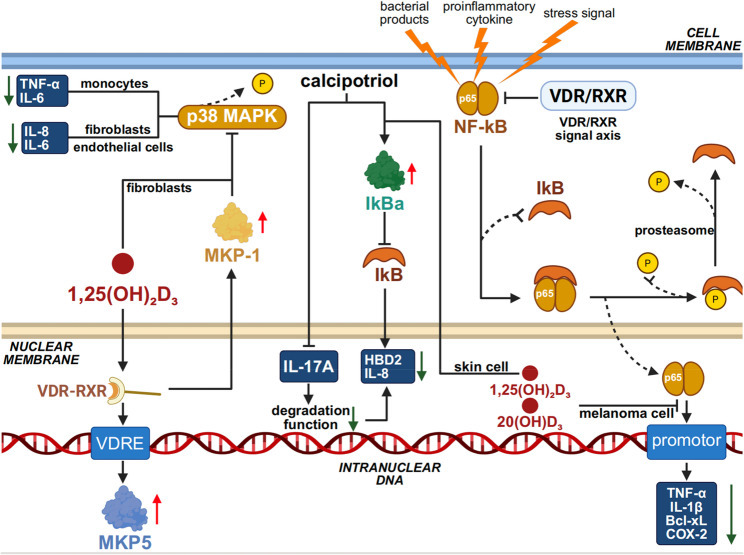

Fig. 4.

Vitamin D regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling in the skin Vitamin D mitigates inflammatory responses by inhibiting pro-inflammatory signaling pathways such as MAPK and NF-κB, thereby reducing the secretion of cytokines including TNF-α and IL-6, while simultaneously promoting the production of anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10. In addition, through the Vitamin D receptor (VDR), it directly regulates the transcription of inflammation-related genes, thereby suppressing excessive inflammatory reactions while preserving basal immune defense functions, ultimately achieving balanced regulation of inflammation

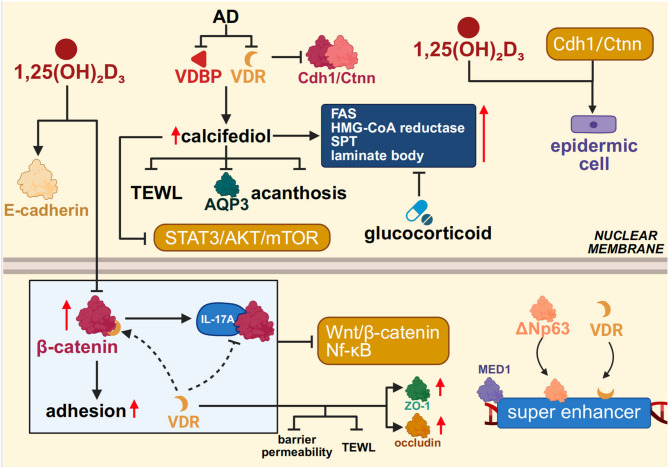

Vitamin D in the regulation of epidermal barrier function

Epidermal barrier homeostasis represents a tightly coordinated physiological state that integrates structural integrity, lipid metabolism, and antimicrobial defense [221].Within this intricate network, the Vitamin D/VDR signaling axis serves as a central regulatory node orchestrating the formation and maintenance of the epidermal barrier. Studies have shown that 1,25(OH)₂D₃ enhances intercellular adhesion among keratinocytes by upregulating E-cadherin expression and inhibiting β-catenin nuclear translocation, thereby stabilizing adherens junction complexes and reinforcing the integrity of tight junctions in the epidermis [222]. Mechanistically, this effect relies on direct interaction between VDR and the C-terminal domain of β-catenin, which competitively disrupts β-catenin’s formation of transcriptional complexes with T-cell factor (TCF), leading to suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity [223, 224]. In VDR-deficient animal models, tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and occludin are markedly reduced, accompanied by increased transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and enhanced barrier permeability. These findings suggest that VDR not only supports structural protein maintenance but also mitigates inflammatory damage to the barrier by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways [225].

Functional studies have further revealed that keratinocyte-specific VDR knockout (VDRKO) mice exhibit markedly delayed re-epithelialization following skin injury, accompanied by impaired migration and activation of follicular and epidermal stem cells [226]. Mechanistically, formation of the E-cadherin–β-catenin (Cdh1/Ctnn) complex is essential for maintaining stem cell polarity and coordinated migration, with its stability dependent on the synergistic regulation by VDR and extracellular calcium signals. VDR deficiency disrupts assembly of this complex, undermining the positional stability of stem cells within their niche and impairing their capacity for asymmetric division and establishment of front-rear polarity during collective migration [226, 227]. Analogous to the positive feedback loop formed by TGF-β1 and CD147 during epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in hepatocellular carcinoma, the Vitamin D–Cdh1/Ctnn axis maintains epidermal epithelial phenotype stability while enabling keratinocytes to transiently acquire migratory competence in response to injury [228]. Using a conditional VDR knockout model, Oda et al. demonstrated that VDR colocalizes with ΔNp63 at MED1-marked super-enhancer regions, cooperatively driving the mesenchymal lineage commitment of epidermal stem cells. Loss of ΔNp63 markedly attenuated the expression of key transcription factors responsible for 1,25(OH)₂D₃-induced epidermal fate determination [229]. This study highlights the crucial role of VDR and ΔNp63 co-occupancy at super-enhancer regions in orchestrating barrier repair.

Beyond maintaining structural stability under homeostatic conditions, Vitamin D also contributes to barrier reconstruction and immune homeostasis reprogramming under pathological stress. In atopic dermatitis (AD), a prototypical barrier-defective disorder, expression of VDBP and the VDR is broadly diminished in the epidermis, indicating impaired local responsiveness to Vitamin D signaling [230]. In DNCB-induced AD mouse models, systemic administration of the Vitamin D metabolite calcifediol markedly improved barrier function, evidenced by reduced transepidermal water loss, alleviation of stratum spinosum hyperplasia, and downregulation of the water-channel protein AQP3 [231]. Further mechanistic studies revealed that calcifediol inhibits the STAT3/AKT/mTOR pathway, suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine release and keratinocyte hyperproliferation, thereby simultaneously modulating barrier architecture and the immune microenvironment [231]. Concurrent upregulation of VDBP and VDR suggests the existence of a VDR-dependent positive feedback loop that reinforces skin barrier homeostasis. Collectively, these findings position Vitamin D not merely as a passive fat-soluble micronutrient, but as an integrative regulator of skin architecture, immunity, and metabolism, with pronounced potential to restore epidermal ecosystem balance under inflammatory stress.

Notably, Vitamin D also counteracts drug-induced barrier dysfunction, particularly exhibiting structural reparative capacity in the context of glucocorticoid therapy. Although topical glucocorticoids effectively attenuate inflammatory dermatoses, they concurrently suppress the expression of lipid-synthesizing enzymes and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), ultimately compromising epidermal permeability and innate immune barrier function [232, 233]. In murine models, topical application of the active Vitamin D₃ metabolite calcitriol significantly reverses glucocorticoid-induced barrier impairment. Mechanistically, calcitriol upregulates key lipid-synthesizing enzymes—including fatty acid synthase (FAS), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMG-CoA reductase), and serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT)—and promotes lamellar body maturation and secretion, thereby enhancing stratum corneum structural cohesion [234–236].

The role of Vitamin D in maintaining epidermal barrier function is multifaceted and synergistic. It reinforces the barrier by remodeling adhesion and tight junctions, regulating pro-inflammatory and proliferative signaling, enhancing lipid metabolism, and strengthening innate immune defenses. Disruption of this signaling axis predisposes the skin to persistent barrier breakdown and chronic inflammation, culminating in the onset and progression of dermatologic pathology(Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mechanisms of Vitamin D in enhancing skin barrier function Vitamin D maintains epidermal barrier integrity by enhancing keratinocyte adhesion, stabilizing tight junction proteins, and inhibiting pro-inflammatory pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB. It also promotes stem cell migration and re-epithelialization, ameliorates barrier dysfunction in conditions such as atopic dermatitis, and counteracts glucocorticoid-induced suppression of lipid synthesis by stimulating lipid production and lamellar body maturation. Through these actions, Vitamin D protects the barrier both structurally and functionally

Vitamin D–microbiome interactions in skin aging

With advancing age, the skin microbiome undergoes reproducible structural and functional shifts—characterized by altered community proportions of Cutibacterium and Staphylococcus species and reprogramming of metabolic pathways—concomitant with barrier fragility and low-grade chronic inflammation (inflammaging), a process tightly linked to dysregulation of host innate immune control [237]. Interestingly, early studies demonstrated that the Vitamin D receptor (VDR) binds to Vitamin D response elements (VDREs) to induce expression of the human antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene, thereby enhancing innate immune function in mammals [238]. Moreover, in the presence of muramyl dipeptide, Vitamin D synergistically induces NF-κB activity as well as the expression of DEFB2/HBD2 and cathelicidin, thereby constraining the overgrowth of opportunistic pathogens [239]. Classic studies established that TLR activation upregulates VDR and CYP27B1, leading to the production of LL-37 and strengthening antimicrobial defense [240]. In wounded skin, Vitamin D enhances the responsiveness of keratinocytes to TLR2 ligands, inducing antimicrobial peptide expression and activating barrier immunity [241]. Vitamin D also regulates the expression and release of serine proteases such as kallikrein-5/7 in keratinocytes, thereby facilitating the cleavage of the precursor protein HCAP18 into smaller active peptides [242]. Collectively, these mechanisms illustrate how the Vitamin D axis translates “danger sensing” from damage- or pathogen-associated signals into antimicrobial peptide expression and barrier immune responses. Both population and in vivo evidence indicate that oral Vitamin D supplementation increases cathelicidin levels in specific skin lesions, while topical Vitamin D analogues (e.g., calcipotriol) similarly enhance hCAP18/LL-37 expression in wound models, suggesting that correcting Vitamin D axis hyporesponsiveness may help reverse the age-associated phenotype of AMP deficiency and susceptibility [243, 244]. Steroid receptor coactivator 3 (SRC3) has been found to colocalize with cathelicidin expression in the epidermal granular layer and promotes transcription via its intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity [127]. Exogenous histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), such as butyrate and trichostatin A, synergize with Vitamin D to enhance cathelicidin and CD14 expression, simultaneously increasing the bactericidal capacity of keratinocytes against Staphylococcus aureus and elevating histone H4 acetylation levels [127]. Vitamin D also upregulates PTH1R in keratinocytes, and treatment with the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) further augments Vitamin D–induced CAMP expression [245]. These findings highlight the critical interplay between Vitamin D–VDR signaling and epigenetic mechanisms, including histone modifications and DNA methylation.

Moreover, the Vitamin D–VDR signaling pathway plays a pivotal regulatory role in the processes of autophagy and cellular senescence in skin cells. On the one hand, Vitamin D enhances the expression of core autophagy regulators such as Beclin-1 and LC3, thereby promoting autophagic activity in keratinocytes and sustaining epidermal homeostasis and barrier integrity [246]. On the other hand, within senescence-associated pathways, Vitamin D attenuates the activation of p38-MAPK and NF-κB, while concomitantly downregulating p16, p21, p53, and the secretion of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors [247]. Acting synergistically, these mechanisms alleviate UVB-induced premature senescence of keratinocytes at the cellular level and, at the tissue level, mitigate photoaging and inflammatory responses. Taken together, the Vitamin D–VDR axis orchestrates a dual regulatory network of autophagy and cellular senescence, thereby providing a molecular basis for maintaining skin homeostasis and delaying aging.

Clinical implications and interventions

An increasing body of evidence indicates that Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent among the elderly, particularly in individuals with insufficient sunlight exposure, impaired cutaneous synthesis, or chronic inflammatory skin conditions [248–250]. Although basic research has delineated the multifaceted roles of Vitamin D in modulating oxidative stress, immune tolerance, and epidermal barrier integrity, clinical evidence regarding its therapeutic efficacy in geriatric dermatologic conditions remains limited and heterogeneous. Nevertheless, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies have provided preliminary support for the potential benefits of Vitamin D supplementation in managing senile pruritus, atopic dermatitis (AD), and psoriasis [48, 251–253].

In elderly patients with idiopathic pruritus, oral supplementation with Vitamin D₃ significantly alleviated itch severity, which correlated with increased serum 25(OH)D levels and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α [252]. In patients with AD, multiple clinical studies have demonstrated that systemic Vitamin D₃ supplementation improves skin dryness and barrier dysfunction, with more pronounced efficacy observed in individuals with low baseline Vitamin D levels [254–256]. In an NC/Nga mouse model, topical application of the Vitamin D analogue calcipotriol increased filaggrin expression and reduced transepidermal water loss (TEWL), highlighting its potential in restoring epidermal barrier function in elderly patients with AD [257]. In psoriasis, adjuvant therapy with Vitamin D analogues has been shown to reduce disease severity scores and modulate the Th17/IL-23 inflammatory axis, suggesting potential utility in chronic immune-dysregulated dermatoses [258, 259]. However, substantial interindividual variability in therapeutic response remains a significant challenge for clinical application [260, 261].

From a therapeutic standpoint, systemic and topical Vitamin D interventions differ markedly in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties [262]. Topical application of calcipotriol primarily activates VDR signaling locally, exerting effects on keratinocyte differentiation, immune modulation, and inflammation control, with minimal systemic absorption and low risk of adverse effects—making it suitable for localized epidermal lesions [263]. In contrast, oral supplementation with Vitamin D₃ increases systemic 25(OH)D levels and modulates immune function, metabolic pathways, and cutaneous homeostasis via widespread VDR activation; however, attention must be given to the risks of hypercalcemia and metabolic adverse events, necessitating appropriate monitoring [264–266]. It is noteworthy that, although Vitamin D supplementation within the recommended intake range is generally safe, Vitamin D intoxication has increasingly drawn attention in the context of prolonged or intermittent high-dose regimens, with severe hypercalcemia as the central mechanism leading to neurological, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal complications [267]. Previous reports have established the tolerable upper intake level (UL) for adults at 4000 IU/day; however, evidence indicates that long-term daily supplementation with 3200–4000 IU may still increase the risk of hypercalcemia and other adverse events in a subset of individuals [268]. Acute Vitamin D toxicity is typically associated with daily intakes exceeding 10,000 IU, resulting in serum 25(OH)D concentrations above 150 ng/mL [269]. Chronic toxicity, by contrast, is linked to sustained daily intakes of 4000 IU or higher over several years, leading to serum 25(OH)D concentrations in the range of 50–150 ng/mL [270]. Importantly, high-dose regimens—particularly bolus or intermittent administration—have not demonstrated clear clinical benefits in randomized controlled trials [271, 272].On the contrary, several studies have suggested that such strategies may increase the risk of adverse outcomes, including falls [273, 274]. Collectively, this evidence indicates that routine high-dose Vitamin D supplementation is inadvisable in the general population; instead, maintaining a steady and moderate daily intake appears to be a more rational approach, balancing safety with potential benefits. Current clinical guidelines recommend tailoring Vitamin D dosing regimens based on age, baseline 25(OH)D levels, comorbidities, and risk factors, with a target serum 25(OH)D concentration of at least 30 ng/mL to ensure cutaneous and systemic health [275, 276].

Notably, polymorphisms in the VDR gene (e.g., FokI, TaqI, ApaI) have been linked to individual sensitivity to skin aging and variability in response to Vitamin D intervention, underscoring the importance of incorporating genetic background into nutritional strategies for elderly skin disorders [277–280]. Studies have shown that, among patients with psoriasis, individuals carrying the ApaI (rs7975232) CC genotype exhibit higher six-week clinical response rates to topical calcipotriol compared with those harboring other genotypes, suggesting an association between this locus and therapeutic response [281]. Furthermore, early clinical studies have reported that FokI, TaqI, and the A-1012G promoter polymorphism are positively associated with favorable responses to calcipotriol, lending support to the pharmacogenetic framework in which drug response is modulated by genetic background [282]. Notably, some investigations have observed no association between BsmI or ApaI polymorphisms and calcipotriol responsiveness, indicating that population stratification and phenotypic definitions may contribute to heterogeneity in reported outcomes [283]. Future strategies should prioritize genotype-informed Vitamin D supplementation and integrate metabolic profiling for personalized dose optimization. Moreover, the lack of large-scale, longitudinal clinical trials using skin-specific endpoints—such as TEWL, AMP expression, and histological markers of epidermal aging—hampers the translational application of Vitamin D in anti-aging dermatology. Therefore, advancing dermatology-focused clinical trials is essential to define the indications, optimal dosing window, and long-term safety profile of Vitamin D interventions, ultimately supporting evidence-based strategies for skin health management in the aging population (Tables 1 and 2, and 3).

Table 1.

Impact of VDR gene polymorphisms on skin diseases

| Polymorphic Loci |

Variant | Group | Dermatological diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FokI | rs2228570 | Han Chinese | Atopic Dermatitis(AD) | [284] |

| Not applicable | Melanoma | [285, 286] | ||

| Iranians | Vitiligo | [287] | ||

| Turks | Psoriasis | [288] | ||

| Adolescents in the Caribbean region of Colombia | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus(SLE) | [289] | ||

| PCOS patients | Seborrheic Dermatitis | [290] | ||

| PCOS patients | Acne Vulgaris | [290] | ||

| Han Chinese、Colombian Caribbean | Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria | [291, 292] | ||

| TaqI | rs731236 | Caucasian、White | Psoriasis | [293, 294] |

| Australians | Multiple Sclerosis | [295] | ||

| Colombian Caribbean | Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria | [292] | ||

| BsmI | rs1544410 | Europeans | Melanoma | [285, 296] |

| Arabian、East Asians | Vitiligo | [297, 298] | ||

| Turks | AD | [299] | ||

| Asians | Psoriasis | [288] | ||

| ApaI | rs7975232 | Turks、White | Psoriasis | [260, 288, 294] |

| Arabian、Indonesians | Vitiligo | [297, 300] | ||

| CDX2 | rs11568820 | Not applicable | Psoriasis | [301] |

| Tru9I | rs757343 | Not applicable | Alopecia areata | [302] |

| VDR SNP | rs2238136 | Spanish People | AD | [303] |

Table 2.

The role of Vitamin D deficiency in the pathogenesis and clinical progression of skin disorders

| Authors | Year | Dermatological diseases | Study design | Sample size | Experimental Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenssen M et al.[55] | 2023 | psoriasis | Randomized Controlled Trial(RCT) | 122 cases | Participants were proportionally allocated to receive Vitamin D (cholecalciferol, 100,000 IU as a loading dose, followed by 20,000 IU weekly) or placebo for a duration of 4 months. | Supplementation with Vitamin D did not affect the severity of psoriasis. |

| Lim SK et al.[304] | 2016 | acne | RTC | 160 cases (80 acne patients and 80 healthy controls) | Serum 25(OH)D levels were measured, and demographic data were collected. Patients with Vitamin D deficiency received oral cholecalciferol treatment at a dose of 1000 IU daily for 2 months. | 25(OH)D levels are negatively correlated with acne severity and show a significant negative correlation with inflammatory lesions. |

| Hassan AR et al.[305] | 2025 | keloids and hypertrophic scars | clinical trial | 30 patients with hypertrophic scars and keloids | Group 1: Patients with Vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency received a monthly systemic injection of Vitamin D (cholecalciferol 200,000 IU) for 3 consecutive months, along with oral calcium supplementation. Additionally, intralesional Vitamin D injections were administered at sites of hypertrophic scars and keloids. | The intralesional injection of Vitamin D in patients with hypertrophic scars and keloids enhances vascular distribution and elasticity in those with sufficient serum Vitamin D levels. However, in patients with serum Vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency, systemic Vitamin D administration does not result in changes in scar height or pigmentation. |

| Group 2: Patients with sufficient Vitamin D levels received only intralesional Vitamin D injections. | ||||||

| Mohamed AA et al.[306] | 2022 | CSU | RTC | 164 cases(77 patients with CSU and 67 healthy controls) | Seventy-seven CSU patients were randomly assigned to the treatment group and the placebo group. The treatment group received 0.25 µg of alfacalcidol daily, while the placebo group received oral placebo treatment for 12 weeks. | Compared to healthy individuals, patients with CSU are more prone to Vitamin D deficiency; therefore, alfacalcidol may serve as an adjunctive therapy in CSU management, with no reported adverse effects. |

| Mony A et al.[307] | 2020 | Chronic urticaria | RTC | 120 cases of chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients with Vitamin D deficiency | CU patients received supplementation of 60,000 IU Vitamin D every two weeks for 12 weeks, while the placebo group received matched placebo. | Supplementation of Vitamin D in CU patients with Vitamin D deficiency can significantly reduce disease severity, potentially by mitigating systemic inflammation. |

| Ahmed Mohamed A et al.[308] | 2021 | Acne vulgaris | RTC | 100 acne patients and 100 healthy controls | One hundred acne patients were randomly assigned to the treatment group and placebo group; the treatment group received 0.25 µg alfacalcidol daily, and the placebo group received placebo orally during the 3-month study period. | Alfacalcidol may exert beneficial effects in acne management, with no reported adverse effects. |

| Nabavizadeh SH et al.[309] | 2023 | CSU | RTC | 80 patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria | Participants were randomly allocated into low-dose (4200 IU/week, group 1) and high-dose (28,000 IU/week, group 2) Vitamin D3 supplementation groups for 12 weeks. | For patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria, Vitamin D supplementation therapy (28,000 IU/week) can be considered a safe and potentially beneficial treatment option. |

| Johansson H et al.[310] | 2021 | Patients with stage II melanoma | RTC | 104 newly resected stage II melanoma patients | Participants were randomly assigned to receive adjunctive Vitamin D3 treatment (100,000 IU every 50 days) or placebo for 3 years. | Although evidence suggests that 25-hydroxyVitamin D (25OHD) plays a role in melanoma prognosis, larger-scale Vitamin D supplementation trials in melanoma patients are still warranted. |

| De Smedt J et al.[311] | 2024 | cutaneous melanoma | RTC | 436 resected melanoma patients from stage IA to III (according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system). | A total of 218 patients received placebo treatment, while another 218 patients received monthly treatment with 100,000 IU of calcitriol for a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 42 months (treatment group). | For patients with CM, monthly supplementation of high-dose Vitamin D is safe and can sustain elevated levels of 25-hydroxyVitamin D during the treatment period; however, it does not improve recurrence-free survival, melanoma-specific mortality, or overall survival. |

| Mansour NO et al.[312] | 2020 | severe atopic dermatitis | RTC | 86 cases | Patients were randomly assigned to receive either Vitamin D3 supplementation at a dose of 1600 IU/day or placebo, in addition to baseline treatment consisting of twice-daily application of 1% hydrocortisone cream for 12 weeks. | Supplementation with Vitamin D may serve as an effective adjunctive therapy to improve clinical outcomes in severe atopic dermatitis. |

| El-Heis S et al.[313] | 2022 | atopic eczema | RTC | unknown | In the MAVIDOS trial, pregnant women were randomized to receive cholecalciferol (1000 IU/day) or matching placebo from approximately 14 weeks’ gestation until delivery. The primary outcome measure was neonatal whole-body bone mineral content. | Prenatal supplementation with cholecalciferol has been demonstrated to confer a protective effect against the risk of atopic eczema in infants, potentially mediated by increased levels of cholecalciferol in breast milk. |

| Rueter K et al.[314] | 2019 | Eczema | Double-blind randomized controlled trial | unknown | Neonates were randomly assigned to receive either Vitamin D supplementation (400 IU/day) or placebo until 6 months of age. A subset of infants also wore personal UV dosimeters to measure direct ultraviolet radiation exposure (290–380 nm). | This study is the first to demonstrate an association between increased direct ultraviolet (UV) exposure in early infancy and a reduced incidence of eczema and pro-inflammatory immune markers before six months of age. |

| Maslin D et al.[315] | 2020 | Eczema | double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | 195 infants born into families with first-degree relatives affected by allergic diseases | Among them, 86 infants were non-randomly assigned personal UV dosimeters to quantify UV exposure (290–380 nm) prior to 3 months of age. | Vitamin D supplementation in high-risk infants effectively elevated Vitamin D levels but did not reduce the incidence of eczema. |

| Exploratory post-hoc analysis of a non-randomized subset indicated an association between increased direct UV exposure and decreased eczema occurrence. | ||||||

| Stanley Xavier A et al.[316] | 2020 | Psoriasiform dermatitis | RTC | 72 cases | Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) were randomly assigned to receive either oral cholecalciferol tablets at a dose of 60,000 IU weekly or a matching placebo for 8 weeks, in addition to standard baseline treatment. | For patients clinically diagnosed with psoriatic dermatitis, supplementation with calcitriol for 2 months did not reduce disease severity. However, plasma IL-10 levels significantly improved after 2 months of treatment in both the placebo and calcitriol groups. |

| Lara-Corrales I et al.[317] | 2019 | AD | RTC | 130 cases | The first phase of the study enrolled AD patients aged 0 to 18 years, assessing disease severity and serum Vitamin D levels. Patients with renal, hepatic, or other dermatological conditions were excluded. Those with abnormal Vitamin D levels (< 72.7 nmol/L) were eligible for the second phase and were randomly assigned to receive either daily Vitamin D supplementation at 2000 IU or placebo. | Although Vitamin D (VD) levels correlated with atopic dermatitis (AD) severity, VD supplementation did not significantly improve the severity of specific dermatitis. |