Abstract

Objective

Lidocaine is the standard dental local anesthetic, while mepivacaine is gaining use despite higher cost and limited comparative data. This study compared the anesthetic efficacy (onset, duration, success rate) of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine versus 2% mepivacaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine for inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) in healthy young adults. A secondary aim was to assess whether lidocaine could serve as a cost-effective alternative without reduced clinical performance, particularly when administered by undergraduate dental students.

Methods

A double-blind, randomized clinical trial was conducted involving 62 healthy dental students aged 19–21 years. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 2% lidocaine or 2% mepivacaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine via conventional IANB technique. The onset time was assessed by pin-prick and cold testing, while the duration of anesthesia was determined by participant self-report. Anesthetic success was defined as achieving effective anesthesia within 10 min post-injection. Adverse events were recorded throughout the study. Group comparisons were analyzed using independent t-tests and chi-square tests, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

The mean onset time was 5.17 ± 1.96 min for lidocaine and 5.52 ± 1.57 min for mepivacaine (P = 0.435). The mean duration of anesthesia was 214.25 ± 47.52 min for lidocaine and 234.32 ± 39.02 min for mepivacaine (P = 0.073). The success rate within 10 min was 78.6% for lidocaine and 91.2% for mepivacaine, though the difference was not statistically significant. Gender-based subgroup analysis showed no significant differences in anesthetic response. Both anesthetics were well tolerated, with only one minor adverse event reported in the mepivacaine group.

Conclusion

For inferior alveolar nerve blocks in healthy young adults, lidocaine and mepivacaine performed similarly in terms of onset, duration, and success rate when administered by undergraduate dental students. This suggests both agents provide predictable anesthesia. Given its lower cost and comparable performance, lidocaine may represent a cost-conscious option for routine dental anesthesia. More extensive research with diverse patient groups and operator experience levels is needed to confirm these findings and broaden their applicability.

Clinical trial registration

Registration number is “TCTR20250106002”, and date of registration is 06/01/2025, https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/show/TCTR20250106002.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-07123-7.

Keywords: Inferior alveolar nerve block, Dental anesthesia, Local anesthetics, Onset time, Duration, Randomized clinical trial

Introduction

Effective pain management is a cornerstone of dental practice, directly influencing patient comfort, procedural success, and treatment adherence. Local anesthetics, which reversibly block nerve conduction without affecting consciousness, are indispensable for achieving this goal [1, 2]. Among these agents, lidocaine, introduced in the 1940 s, remains the gold standard for dental anesthesia due to its well-established reliability and safety profile [3, 4]. Mepivacaine, a structurally similar amide anesthetic developed later, is theorized to offer faster onset and longer duration owing to its lower pKa, although clinical evidence supporting this claim remains inconsistent [5–7].

Despite their widespread use, comparisons between lidocaine and mepivacaine in mandibular anesthesia have produced conflicting results. Some studies report no significant differences in efficacy, while others suggest mepivacaine may have advantages in specific scenarios, such as reduced vasodilation or milder cardiovascular effects. Notably, regional usage further complicates interpretation: mepivacaine is utilized in both Thailand and China, attributed to its purported effects [8, 9], whereas lidocaine remains predominant in Western countries such as the UK and the US [1, 10]. This divergence is particularly notable given the higher cost of mepivacaine. For example, in Thailand, clinical use of 2% mepivacaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine has been reported more often than 2% lidocaine, although definitive evidence for superior clinical outcomes remains limited. This raises significant concerns regarding cost-effectiveness and evidence-based practice.

The existing literature is further limited by methodological heterogeneity, including variation in anesthetic concentrations, evaluation protocols, operator skill, and study populations. For example, Barath et al. (2015) [11] reported faster onset with mepivacaine in third molar extractions, while Allegretti et al. (2016) [12] found no significant difference between the agents in patients with irreversible pulpitis. Moreover, anecdotal claims that mepivacaine shortens chair time due to quicker onset remain largely unsubstantiated. Such inconsistencies highlight the need for controlled comparative studies in well-defined, healthy populations to clarify the relative merits of these anesthetic agents.

To address these ambiguities, this study investigated the comparative performance of 2% lidocaine and 2% mepivacaine (with 1:100,000 epinephrine, respectively) when administered as inferior alveolar nerve blocks in healthy young adults. Specifically, the study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of the two anesthetics by comparing the onset time and duration of action. It also aimed to assess clinical utility by comparing the success rate of achieving anesthesia within 10 min. Additionally, it explored practical implications, particularly whether lidocaine, being more affordable, may represent a cost-effective alternative without compromising efficacy. The primary objective was to compare the clinical efficacy of the two anesthetics and to explore whether lidocaine performs equivalently to mepivacaine under standardized conditions. The present study employed a double-blind, randomized design with standardized assessment protocols, including pin-prick testing and confirmation of pulpal anesthesia, to generate robust evidence to guide clinical decision-making. The findings were expected to balance scientific rigor with practical relevance, optimizing patient care and resource utilization in dental anesthesia.

Methodology

Study design and participants

This was a double-blind, randomized, pilot comparative trial conducted at the Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, designed as a comparative efficacy study and not as an equivalence or non-inferiority trial. Although the trial registry target was 250 participants, feasibility considerations limited enrollment to 100 fourth-year dental students enrolled in the Professional Development course. All participants were from the same school and academic year, within a narrow age range. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University (HREC-DCU-P 2024-001). The study design followed the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 guidelines and was registered with the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR20250106002) on January 06, 2025. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Participants aged 19–21 years. Healthy individuals with no reported pain. At least two intact mandibular teeth (first premolar and first molar) free from crowns, bridges, extensive restorations, severe caries, periodontal disease, trauma, or hypersensitivity. Participants were enrolled in inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) training and practiced on each other under supervision.

Exclusion criteria

Use of medications that could alter pain perception or interfere with anesthetic efficacy. Active infections or inflammation at the injection site. Anatomical abnormalities affecting IANB success (e.g., trismus, bifid mandibular canals, micrognathia). Failure to achieve anesthesia within 10 min or incomplete questionnaire data.

Eligibility-related exclusions

Of the 100 enrolled students, 20 were excluded due to missing questionnaire data.

Outcome-related failures

An additional 18 participants were excluded due to failed IANB or delayed onset.

The final sample comprised 62 participants (Supplementary Data S1).

Randomization and blinding

Participants were randomly assigned (block randomization, blocks of 10) to receive either 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Medicaine Inj. 2%; Hound Co., Ltd., Korea) or 2% mepivacaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Scandonest 2% Special; Septodont, France). To ensure blinding, syringes were de-identified by removing labels and marking volumes with a permanent marker. Both participants and assessors were blinded to the anesthetic used.

Injection protocol

Under supervision by oral and maxillofacial surgeons, students administered IANB to each other using a 27-gauge, 30-mm needle. Before initiating the trial, student operators underwent calibration sessions supervised by oral and maxillofacial surgeons to standardize technique. The conventional IANB technique was followed, using anatomical landmarks (coronoid notch, pterygomandibular raphe, pterygotemporal depression) to guide needle insertion (20–25 mm depth). Approximately 1.5 mL of anesthetic solution was injected slowly over one minute [5, 6]. The needle was then withdrawn and safely recapped. Aspiration was performed before injection to avoid intravascular administration. Participants were monitored immediately post-injection for potential adverse events; no complications occurred.

Onset of anesthesia

Anesthesia onset was defined as the time (in minutes) from the end of injection to complete numbness. Assessment was conducted every 30 s using a digital timer. Participants were questioned about sensation in the lip, tongue, and chin bilaterally. Pin-prick testing was performed using a 3 − 0 nylon monofilament suture to confirm numbness. Failure to achieve anesthesia within 10 min was recorded as an unsuccessful block. The questionnaire used in this study is provided in Supplementary Data S2.

Pulpal anesthesia assessment

Upon reporting numbness, pulpal anesthesia was assessed on the mandibular first premolar and first molar using Endo-Frost cold spray (Roeko, Coltene Whaledent, Switzerland) applied via cotton pellet. A lack of response indicated a successful nerve block. If sensation was reported, testing was repeated after 3 min.

Duration of anesthesia

Participants self-reported the time at which sensation returned using a standardized questionnaire. The total duration (in minutes) of anesthesia was calculated from the completion of the injection to the return of normal sensation.

Adverse event monitoring

Participants were monitored immediately after injection for potential adverse events, such as intravascular injection or nerve injury; no complications occurred. Additionally, participants were asked to report any adverse events at 4 h and 24 h post-injection. Documented effects included allergy, facial nerve paralysis, swelling, bruising, trismus, headache, nausea, and dizziness.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics, including mean ± standard deviation (SD) and standard error of the mean (SEM), were calculated for onset time and duration of anesthesia. While SD was used to reflect variability within each group, SEM was included to represent the precision of the sample mean and facilitate interpretation of intergroup comparisons, particularly in a pilot study setting with modest sample sizes. Data normality and variance assumption were assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Levene test, respectively, which confirmed a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. The means of onset and duration between the two anesthetic groups were compared using the independent t-test. A gender subgroup analysis was also performed using the same test, as an exploratory analysis based on possible body size differences between genders that could influence anesthetic duration. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical outcomes including participants identified the initial numbness site and success rates. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Of the 100 enrolled participants, 20 were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires. An additional 18 participants were excluded post-allocation due to failed or delayed anesthesia, resulting in a final sample of 62 participants (Supplementary Data S1), consisting of 18 males (29%) and 44 females (71%). The participants were divided into two groups: 28 individuals (45.2%) received 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Group A: 9 males, 19 females), and 34 individuals (54.8%) received 2% mepivacaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Group B: 9 males, 25 females).

Efficacy: onset time and duration of anesthesia

As shown in Table 1, the mean onset and duration of inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia were slightly longer with mepivacaine compared to lidocaine. No statistically significant differences were observed, and no substantial practical differences were identified between the two agents. However, formal equivalence cannot be claimed without pre-specified margins.

Table 1.

Comparison of onset time and duration of anesthesia between 2% Lidocaine and 2% mepivacaine (Both with 1:100,000 Epinephrine)

| Lidocaine (n = 28) Mean ± SD (95% CI) |

Mepivacaine (n = 34) Mean ± SD (95% CI) |

P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset Time (min) |

5.17 ± 1.96 (95% CI: 4.41–5.93) |

5.52 ± 1.57 (95% CI: 4.97–6.07) |

0.435 |

| Duration (min) |

214.25 ± 47.52 (95% CI: 195.82–232.68) |

234.32 ± 39.02 (95% CI: 220.71–247.93) |

0.073 |

*P-values from independent t-tests

Clinical utility: success rate within 10 min

As shown in Table 2, in evaluating the success of anesthesia onset within 10 min, the mepivacaine group demonstrated a higher success rate (91.2%) compared to the lidocaine group (78.6%). While this difference favored mepivacaine numerically, it was not statistically significant, suggesting that both anesthetic agents offer comparable clinical utility for inferior alveolar nerve blocks in healthy young adults (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical utility: success rate of anesthesia achievement within 10 min

| Success (≤ 10 min)* | 95% CI | Failure (> 10 min or no anesthesia) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine | 22/28 (78.6%) | 60.5% – 89.8% | 6/28 (21.4%) |

| Mepivacaine | 31/34 (91.2%) | 77.0% – 96.9% | 3/34 (8.8%) |

*Difference of success rate between groups was analyzed using chi-square test (P = 0.161)

Gender-Based comparison of onset and duration

As summarized in Table 3, subgroup analysis revealed no statistically significant gender-based differences in the onset or duration of anesthesia within either the lidocaine or mepivacaine groups, indicating consistent anesthetic performance across gender.

Table 3.

Gender-Based comparison of anesthetic efficacy in Lidocaine and mepivacaine groups

| Lidocaine Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n; %) | Mean | SD | SEM | P -value* | |

| Onset (min) | Male (9; 32.1) | 5.30 | 1.99 | 0.66 | 0.820 |

| Onset (min) | Female (19; 67.9) | 5.11 | 2.01 | 0.46 | |

| Duration (min) | Male (9; 32.1) | 195.22 | - | - | 0.053 |

| Duration (min) | Female (19; 67.9) | 223.26 | - | - | |

| Mepivacaine Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n; %) | Mean | SD | SEM | P -value* | |

| Onset (min) | Male (9; 26.5) | 5.56 | 1.71 | 0.57 | 0.943 |

| Onset (min) | Female (25; 73.5) | 5.51 | 1.56 | 0.31 | |

| Duration (min) | Male (9; 26.5) | 231.78 | 45.82 | 15.27 | 0.823 |

| Duration (min) | Female (25; 73.5) | 235.24 | 37.29 | 7.46 | |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted. (–) indicates the subgroup sample size was insufficient for stable SD/SEM calculation. Independent t-tests were applied to raw values for statistical comparisons. Missing values reflect reduced sample size due to incomplete questionnaire data

*P-values from independent t-tests

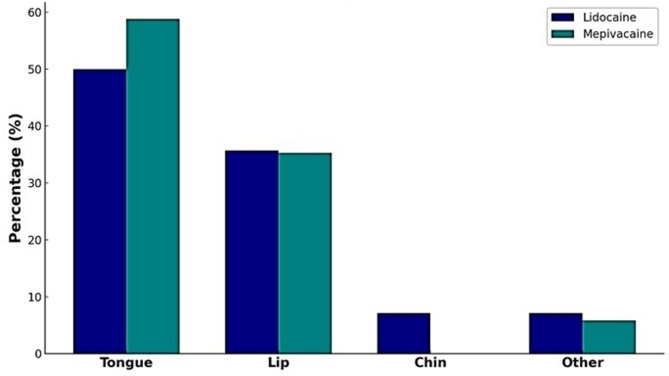

First perceived area of numbness

Participants were asked to identify the first anatomical area in which numbness was perceived following the injection. As depicted in Fig. 1, the tongue was the most frequently reported initial site of numbness in both groups: 50.0% in the lidocaine group and 58.8% in the mepivacaine group. The lip followed as the second most common site, with 35.7% in the lidocaine group and 35.3% in the mepivacaine group. Reports of numbness in the chin and other areas were relatively infrequent, indicating that both anesthetics follow a similar neuroanatomical distribution pattern in early onset. No statistically significant differences were observed across each site (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Participants Identified the Initial Numbness Site (Tongue, Lip, Chin, Or Other) Post-IANB Anesthesia. Percentages reflect the proportion of responses within each anesthetic group (lidocaine: n = 28; mepivacaine: n = 34). (P > 0.05, chi-square test between groups)

Adverse effects

The vast majority of participants (98.4%) experienced no adverse effects following the administration of either anesthetic. Only one participant (1.6%) in the mepivacaine group reported a transient, mild headache that was self-limiting and resolved spontaneously within a short period without the need for medication, while no adverse effects were observed in the lidocaine group. These findings confirm that both anesthetic formulations were well tolerated in this population.

Literature review

Several randomized controlled trials have investigated the comparative efficacy of lidocaine and mepivacaine in dental anesthesia, although findings remain inconclusive due to variations in study design and clinical context (Table 4). Barath et al. (2015) conducted a double-blind RCT on patients undergoing mandibular third molar surgery. They reported a significantly faster onset of anesthesia with 2% mepivacaine compared to 2% lidocaine, although duration differences were not statistically significant [11]. Visconti et al. (2016) also observed a higher success rate for mepivacaine using single-cartridge volumes in patients with irreversible pulpitis, suggesting potential benefits under specific clinical conditions [13].

Table 4.

Summary of randomized controlled trials comparing mepivacaine and Lidocaine

| Study Year (Country) |

Study Design Age (years) |

Comparison | Technique Method |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barath et al., 2015 (India) [11] |

Double-blind RCT (40–75 years) |

2% mepivacaine vs. 2% lidocaine + 1:80,000 epinephrine Mandibular third molar surgery |

IANB Onset measured every 30 s via pinprick; failure > 10 min = unsuccessful |

OOA: mepi 4.2 min, lido 4.6 min (p < 0.05) DOA: mepi 177.2 min, lido 166.7 min (p > 0.05) |

|

Visconti et al., 2016 (Brazil) [13] |

Double-blind RCT (18–50 years) |

2% mepivacaine vs. 2% lidocaine + 1:100,000 epinephrine Irreversible pulpitis |

IANB VAS and EPT after 10 min; failure = pain response |

SRA: mepi 52%, lido 33% (with single cartridge) |

|

Srisurang et al., 2011 (Thailand) [9] |

Double-blind RCT (13–60 years) |

2% mepi vs. 2% lido vs. 4% articaine + 1:100,000 epinephrine Maxillary teeth |

Infiltration Pinprick and EPT at 3, 5, and 60 min |

SRA: 4% articaine > mepi or lido (broader soft tissue spread) |

|

Tortamano et al., 2013 (Brazil) [14] |

Double-blind RCT (18–40 years) |

2% lido + 1:100k vs. 4% articaine + 1:100k or 1:200k epi |

IANB EPT at 1 min, then every 3 min until sensation returned |

OOA: lido 8.7 min DOA: lido 61.8 min |

|

Allegretti et al., 2016 (Brazil) [12] |

RCT (18–50 years) |

4% articaine vs. 2% lidocaine vs. 2% mepivacaine + 1:100,000 epinephrine Irreversible pulpitis |

IANB VAS and EPT were assessed at 10 min |

SRA: mepi 72.7%, lido 54.5% (p > 0.05) |

The notation “1:100k” and “1:200k indicates 1:100,000 and 1:200,000 concentrations of epinephrine

OOA Onset of Anesthesia, DOA Duration of Anesthesia, SRA Success Rate of Anesthesia, IANB Inferior alveolar nerve block, VAS Verbal analogue scale, EPT Electric pulp test

In contrast, Allegretti et al. (2016) found no statistically significant difference in the success rates among mepivacaine, lidocaine, and articaine when administered for IANB in similar cases of irreversible pulpitis, despite observing a numerically higher success rate for mepivacaine [12]. This highlights the inconsistencies across studies, likely influenced by patient population, clinical indication, and anesthetic delivery parameters.

Additional studies further underscore the complexity of this comparison. Tortamano et al. (2013) focused on different epinephrine concentrations combined with articaine and lidocaine [14], offering indirect insight into lidocaine’s efficacy under varied vasoconstrictor settings rather than direct comparisons with mepivacaine. Meanwhile, Srisurang et al. (2011) evaluated infiltration techniques in maxillary teeth and reported broader anesthesia with articaine compared to both lidocaine and mepivacaine; however, they did not explore IANB-specific efficacy [9].

Taken together, these RCTs provide some evidence for the potential clinical advantages of mepivacaine in specific scenarios. However, methodological heterogeneity, differing anesthetic concentrations, and variability in clinical protocols limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions. These inconsistencies underscore the need for standardized, well-controlled trials, such as the present study, to clarify the relative performance of lidocaine and mepivacaine under uniform conditions.

Discussion

This study investigated the comparative efficacy of 2% lidocaine and 2% mepivacaine, each combined with 1:100,000 epinephrine, for inferior alveolar nerve block in a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. While a preference for mepivacaine appears to exist among Thai dentists based on usage patterns, such a preference lacks consistent support from the literature. Previous studies have reported conflicting results, often confounded by methodological variations [7, 8, 14–16]. The present study contributes novel insights by directly comparing these two agents in a homogeneous Thai cohort, a population underrepresented in existing literature, while incorporating cost-effectiveness considerations.

To address prior inconsistencies, we employed a rigorous and multi-modal methodology, including subjective numbness reporting, objective pin-prick testing with a 3 − 0 nylon monofilament suture, and confirmation of pulpal anesthesia using Endo Ice. Standardized onset assessment across these modalities was designed to enhance objectivity and minimize bias.

Our findings revealed no statistically significant differences in onset time or duration of anesthesia between lidocaine and mepivacaine (Table 1), and no substantial practical differences were identified. However, formal equivalence cannot be claimed without pre-specified margins. The slightly longer onset times observed compared to product leaflets or previous studies [7] likely reflect the comprehensive evaluation protocol employed in this trial. By demonstrating comparable efficacy at a lower cost, these results challenge regional preferences for mepivacaine and provide evidence to optimize resource allocation in dental practice.

The success rates for achieving anesthesia within 10 min were 78.6% for lidocaine (22/28) and 91.2% for mepivacaine (31/34), a difference that was numerically in favor of mepivacaine but not statistically significant (Table 2). These findings are consistent with those of Srisurang et al., who also conducted a randomized, double-blind study [9]. A key methodological difference is that their trial used a single operator, whereas the present study employed multiple calibrated injectors under the supervision of oral and maxillofacial surgeons to minimize operator-related variability. Despite calibration, inter-operator differences cannot be entirely excluded and may have influenced outcomes. Notably, their trial did not report onset or duration data, which limits direct comparison.

Previous trials by Barath et al. (2015) and Tortamano et al. (2013) also demonstrated variability in onset and duration of anesthesia, underscoring the difficulty of cross-study comparisons due to heterogeneity in methodologies, anesthetic formulations, and definitions of success [11, 14]. In our study, gender-based subgroup analysis showed no statistically significant differences in either onset or duration within or between groups (Table 3). Females demonstrated numerically longer durations, which may reflect differences in body size relative to the fixed 1.5 mL injection volume. Such subgroup observations, however, are limited by small sample size and should be interpreted with caution. The pattern of sensory distribution, as reported by participants, was also comparable between agents, with the tongue being most frequently affected, followed by the lip and chin (Fig. 1). This suggests similar neuroanatomical diffusion characteristics between lidocaine and mepivacaine.

Our results are broadly in line with the Cochrane review by St. George et al. [4], which highlighted the uncertainty surrounding anesthetic success in mandibular molars with irreversible pulpitis and emphasized the lack of standardized data on onset and duration. Su et al. (2014), in a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials, concluded that mepivacaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine demonstrated higher effectiveness overall [8]. Similarly, Visconti et al. reported higher success with mepivacaine (86%) compared with lidocaine (67%), but their study was restricted to patients with irreversible pulpitis using only a single cartridge, limiting comparability to our findings in healthy volunteers [13]. Further complicating cross-study interpretation is the lack of uniformity in manufacturer-reported product information. For instance, the leaflet for lidocaine (Medicaine Inj. 2%; Hound Co., Ltd, Korea; distributed in Thailand by Schumit) specifies an onset of 3–4 min and a duration of approximately 2 h, whereas the leaflet for mepivacaine (Scandonest 2% Special; Septodont) provides no such quantitative details. These inconsistencies highlight the importance of independent, standardized clinical evaluations.

Both agents were well tolerated, with only one participant in the mepivacaine group reporting a transient headache, and no adverse effects were observed in the lidocaine group. Beyond clinical performance, the economic aspect is also of practical importance. Lidocaine is generally less expensive than mepivacaine and, given the comparable efficacy observed in this study, may represent a cost-conscious choice in routine dental practice, particularly in high-volume or resource-limited settings. A formal cost-effectiveness analysis is warranted to further support evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice.

Study limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, of the 100 enrolled participants, 20 were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires, and an additional 18 participants were excluded post-allocation due to failed or delayed anesthesia, resulting in a final sample of 62 participants. This relatively high number of dropouts is a limitation as it reduced statistical power and could potentially introduce selection bias, thus impacting the generalizability of our findings. Second, the relatively small sample size (n = 62) limits statistical power to detect subtle differences between anesthetic agents, and the findings should therefore be interpreted cautiously until replicated in larger-scale trials. Third, the study population consisted exclusively of healthy dental students aged 19–21. This narrow demographic may not represent the broader dental patient population, particularly older individuals or those with systemic comorbidities, which restricts the generalizability of the results. Fourth, the investigation focused solely on the conventional IANB technique and did not compare outcomes with alternative approaches such as the Gow-Gates or Akinosi methods [17], which may influence anesthetic onset and success rates. Finally, while administration was supervised by calibrated dental students in a controlled academic environment, inter-operator differences cannot be entirely excluded and may have influenced outcomes, further highlighting that these conditions do not fully reflect the variability in practitioner technique and experience encountered in everyday clinical practice.

Another limitation is that anesthetic duration was determined primarily by participant self-report, which is inherently subjective and susceptible to recall bias. The absence of objective sensory testing at fixed intervals reduces the reliability of these data. Furthermore, anesthetic efficacy was not assessed during actual dental procedures involving pain stimuli, such as extractions or endodontic therapy, thereby limiting the applicability of the findings to scenarios requiring profound analgesia.

Pharmacokinetic measurements were also not undertaken; such data could have provided mechanistic insight into systemic absorption and tissue diffusion characteristics. Adverse events were monitored only up to 24 h post-injection, so rare or delayed complications may have been missed. Finally, the relatively high number of post-allocation exclusions further reduced the effective sample size, compounding the limitation of statistical power.

These limitations underscore the need for future research that includes more heterogeneous patient populations, evaluates alternative anesthetic techniques, and incorporates broader clinical outcomes to validate and extend the present findings. Standardized injections by multiple operators add real-world variability; however, subsequent trials may benefit from single-operator protocols for tighter control. Collectively, our results further emphasize the importance of standardized methodologies and larger, more diverse clinical trials to resolve inconsistencies in existing literature and to confirm both the clinical and economic implications suggested by this pilot study.

Conclusion

This randomized, double-blind clinical trial demonstrated that 2% lidocaine and 2% mepivacaine, each with 1:100,000 epinephrine, provide comparable efficacy for inferior alveolar nerve block in healthy young adults. No statistically significant differences were observed in onset time, duration of anesthesia, or success rates within 10 min of administration. These findings bridge the gap between anecdotal preferences and evidence-based practice, offering the first multimodal evaluation of these anesthetics in a homogeneous Asian cohort.

Findings indicate that lidocaine may be a cost-effective alternative without compromising efficacy in similar patient populations, potentially support its use in routine dental practice, particularly in high-volume or resource-limited settings. However, the study’s limitations, including a relatively small sample size, homogeneous population, reliance on self-reported outcomes, and absence of procedural pain stimuli, necessitate cautious interpretation. Large-scale studies involving more diverse patient populations, alternative injection techniques, and clinically relevant procedures are warranted to validate these findings and inform evidence-based anesthetic selection in dental practice, thereby enhancing generalizability.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

TP acknowledges Chulalongkorn University Office of International Affairs and Global Network Scholarship for International Research Collaboration. ChatGPT was used to check the grammar of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- IANB

Inferior alveolar nerve block

Authors’ contributions

SP contributed to the conceptualization, conducted the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. SCho and SChi conducted the study, collected and analyzed the data. KSF revised the manuscript draft, SPro, ST, and SC performed data analysis. TP was involved in data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and gave final approval.

Funding

This research was supported by Health Systems Research Institute (68 − 032, 68 − 059), Faculty of Dentistry (DRF69_005), Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University (HEA_FF_68_008_3200_001).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University (HREC-DCU-P 2024-001). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant institutional guidelines and regulations. The study design followed the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 guidelines and was registered with the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR20250106002) on January 06, 2025. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Logothetis DD. Local anesthesia for the dental hygienist. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

- 2.Nagendrababu V, Pulikkotil SJ, Suresh A, Veettil SK, Bhatia S, Setzer FC. Efficacy of local anaesthetic solutions on the success of inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with irreversible pulpitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int Endod J. 2019;52(6):779–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker DE, Reed KL. Local anesthetics: review of Pharmacological considerations. Anesth Prog. 2012;59(2):90–101. quiz 2–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St George G, Morgan A, Meechan J, Moles DR, Needleman I, Ng YL, et al. Injectable local anaesthetic agents for dental anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):Cd006487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas DA. An update on local anesthetics in dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68(9):546–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malamed SF. Handbook of local anesthesia. 7th ed. St. Louise, MO: Mosby; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moussa N, Ogle OE. Acute pain management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2022;34(1):35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su N, Liu Y, Yang X, Shi Z, Huang Y. Efficacy and safety of mepivacaine compared with lidocaine in local anaesthesia in dentistry: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int Dent J. 2014;64(2):96–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srisurang S, Narit L, Prisana P. Clinical efficacy of lidocaine, mepivacaine, and articaine for local infiltration. J Investig Clin Dent. 2011;2(1):23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vieira WA, Paranhos LR, Cericato GO, Franco A, Ribeiro MAG. Is mepivacaine as effective as lidocaine during inferior alveolar nerve blocks in patients with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2018;51(10):1104–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barath S, Triveni VS, Sai Sujai GV, Harikishan G. Efficacy of 2% mepivacaine and 2% Lignocaine in the surgical extraction of mesioangular angulated bilaterally impacted third molars: a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allegretti CE, Sampaio RM, Horliana AC, Armonia PL, Rocha RG, Tortamano IP. Anesthetic efficacy in irreversible pulpitis: a randomized clinical trial. Braz Dent J. 2016;27(4):381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visconti RP, Tortamano IP, Buscariolo IA. Comparison of the anesthetic efficacy of mepivacaine and lidocaine in patients with irreversible pulpitis: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Endod. 2016;42(9):1314–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tortamano IP, Siviero M, Lee S, Sampaio RM, Simone JL, Rocha RG. Onset and duration period of pulpal anesthesia of articaine and lidocaine in inferior alveolar nerve block. Braz Dent J. 2013;24(4):371–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho JTF, van Riet TCT, Afrian Y, Sem K, Spijker R, de Lange J, et al. Adverse effects following dental local anesthesia: a literature review. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2021;21(6):507–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh P. An emphasis on the wide usage and important role of local anesthesia in dentistry: A strategic review. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2012;9(2):127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas DA. Alternative mandibular nerve block techniques: a review of the Gow-Gates and Akinosi-Vazirani closed-mouth mandibular nerve block techniques. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:S8-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.