Abstract

Astragaloside (AST) has shown therapeutic potential against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, its poor water solubility and low bioavailability limit its clinical application. To overcome these challenges, we developed an AST-loaded zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (AST@ZIF) using supercritical fluid carbon dioxide (SCF-CO2) technology. This approach aimed to enhance the solubility, bioavailability, and anti-tumor efficacy of AST. Notably, this is the first study to employ SCF-CO2 as an anti-solvent through solution-enhanced dispersion by supercritical fluids (SEDS) for preparing drug-loaded ZIF-8. The resulting AST@ZIF-SEDS displayed a uniform hexagonal or cubic morphology, with AST transitioning from a crystalline to an amorphous state. Compared to AST@ZIF prepared using traditional methods (one-pot synthesis and solvent adsorption), AST@ZIF-SEDS demonstrated superior drug loading capacity, dispersibility, reduced residual solvent content, and improved stability. As a novel carrier, ZIF-8 effectively enhanced the solubility and bioavailability of AST while maintaining favorable biosecurity. In vivo studies further confirmed that AST@ZIF-SEDS significantly improved tumor inhibition compared with AST powder. In conclusion, SEDS technology represents a promising strategy for maximizing the therapeutic potential of ZIF-8 as a drug carrier. AST@ZIF-SEDS exhibited strong anti-tumor activity and holds potential as an effective treatment for NSCLC.

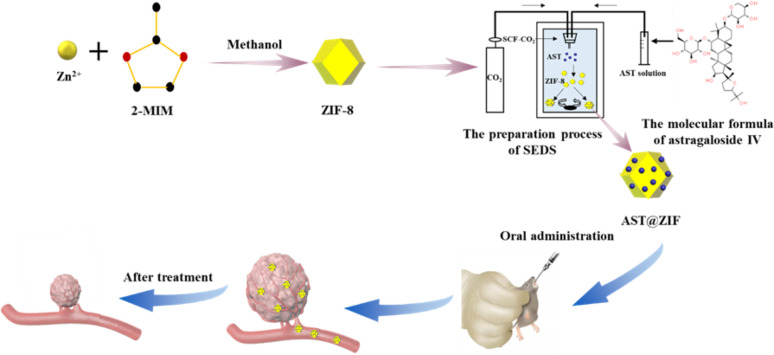

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Astragaloside IV, Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8, Solution-enhanced dispersion by supercritical fluids, Solubility, Non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is a malignant tumor with the highest morbidity and mortality rates in the world. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common form of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 80–85% of the total cases. Owing to the rapid progression and metastasis of NSCLC, most patients are already in the middle to late stages at the time of diagnosis, resulting in limited surgical opportunities and a high postoperative recurrence rate [1, 2]. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy are the primary treatments for NSCLC [3–5]. Currently, the dual-drug cisplatin regimen, including gemcitabine and vinorelbine [6, 7], is the standard regimen for the first-line of advanced NSCLC treatment, whereas docetaxel and pemetrexed monotherapy are used as the second-line treatment [8, 9]. However, these interventions targeting the different stages of NSCLC may still result in treatment failure owing to tumor micrometastasis, decreased patient compliance from toxicity and side effects, and the development of acquired drug resistance. The 5-year survival rate of patients with advanced NSCLC remains less than 15% [10, 11]. Therefore, the search for new chemotherapeutic drugs is a major issue that urgently needs to be addressed for the treatment of NSCLC.

Astragalus is a traditional Chinese medicine widely used for treating diseases such as diabetes, angiocardiopathy, and various cancers [12]. Modern pharmacology reveals its role in enhancing immunity, organ protection, reducing blood sugar, and exerting anti-tumor effects [13]. Astragaloside IV (AST), its primary active component, exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties. Notably, AST has shown efficacy against several cancers, including ovarian, liver, breast, colorectal, and lung cancers [14], by inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis, promoting apoptosis, enhancing immune function, and preventing drug resistance. It regulates critical pathways involved in epithelial–mesenchymal transformation and autophagy, such as the phosphoinositide‑3‑kinase/protein kinase B, Wnt/β‑catenin, mitogen‑activated protein kinase/extracellular regulated protein kinase, and transforming growth factor‑β/SMAD pathways [15]. Additionally, AST impedes lung cancer progression by curtailing tumor growth, invasion, migration, and angiogenesis, primarily through its influence on macrophage M2 polarization via the AMPK signaling pathway [16]. However, AST exhibits poor water solubility and low bioavailability following oral administration and gets distributed across multiple tissues and organs without specific tissue targeting, which limits its clinical application [17]. In recent years, researchers have developed different AST delivery systems, such as nanoparticles, liposomes, and hydrogels, to improve the water solubility and bioavailability of AST [18–20]. However, the drug loading efficiency of these delivery systems remains unsatisfactory, typically below 15%. Therefore, it is crucial to seek new delivery carriers to enhance the drug loading and water solubility of AST, consequently increasing its therapeutic efficacy.

Recently, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have attracted much attention as novel hybrid porous materials owing to their high specific surface area, abundant pore structures, structural and compositional diversity, and the ease of tailoring their pores as well as their physicochemical properties [21]. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8), a subclass of MOFs, in addition to the characteristics of MOFs, has unique characteristics. It is easy to synthesize, has a large specific surface area, high porosity, pH sensitivity, good thermal stability, low toxicity, and good biocompatibility, making it an ideal carrier for drug delivery, and has been used in anti-tumor, antibacterial, and hypoglycemic drugs [22–24]. Additionally, the encapsulation of poorly water-soluble drugs in ZIF-8, such as mebendazole, 5-fluorouracil, baicalin, and celastrol, that had previously been encapsulated, significantly improved their water solubility and bioavailability [25–28]. The conventional methods of ZIF-8 drug loading include one-pot synthesis (OPS) and solvent adsorption (SA) [29, 30]. However, these methods have several drawbacks, including the difficulty in controlling the product properties during preparation, uneven particle size distribution, large residual organic solvent generation, and challenges in achieving complete occupancy of the ZIF-8 pores with drug molecules [31, 32]. Supercritical fluid carbon dioxide (SCF-CO2) technology, with its superior properties, offers an interesting alternative for drug loading in nanodelivery systems, overcoming the shortcomings of conventional preparation methods. Its advantages include controllable particle size, minimal residual organic solvent, an efficient and fast preparation process, and the final product not requiring further purification. Additionally, the low viscosity and high diffusivity of supercritical fluids enable the efficient delivery of drug molecules into the pores of any given material, which can further improve drug loading [33, 34]. Researchers have reported the use of SCF-CO2 impregnation to load MOFs and ZIFs with drugs such as honokiol, curcumol, and carvacrol [35–37]. In these cases, the drugs exhibited good solubility in SCF-CO2, where SCF-CO2 functioned as a solvent during the preparation process. However, most drugs are insoluble in SCF-CO2, making them unsuitable for such methods. Solution-enhanced dispersion by supercritical fluids (SEDS) uses the anti-solvent properties of supercritical fluids to prepare particles. The principle of SEDS is based on the ability of SCF-CO2 to dissolve in a suitable solvent, while the solute has limited solubility in it. As the solution disperses rapidly in SCF-CO2, this enables the solute to achieve a high and fast supersaturated state to form small particles in the carrier [38, 39]. Currently, there are no relevant reports on the drug loading of MOFs using SEDS.

In this study, ZIF-8 was used as a drug carrier, and the insoluble drug AST was loaded using SEDS technology to improve its bioavailability and anti-tumor efficacy (Fig. 1). To verify the advantages of supercritical fluid technology, AST-loaded ZIF-8 (AST@ZIF) was also prepared by OPS and SA methods and compared with AST@ZIF-SEDS in many aspects. Prior to the preparation experiment, the solubility of AST in SCF-CO2 was assessed to ensure the feasibility of preparing AST@ZIF-SEDS. Subsequently, AST-ZIF was characterized using scanning electron microscopy, nitrogen adsorption/desorption, X-ray diffraction, and differential scanning calorimetry. In addition, the saturation solubility and dissolution rate of AST@ZIF were investigated, and the loading mechanism of ZIF-8 on the drug molecules was explored. Finally, we investigated the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of AST@ZIF to evaluate its therapeutic potential as a drug delivery system for NSCLC.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the formation of AST@ZIF-SEDS and its anti-tumor effect

Materials and methods

Materials

AST (purity ≥ 98%) was obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 2-Methylimidazole (2MIM) was purchased from Rhawn Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Zn(NO3)2•6H2O was bought from Shanghai McLin Bio-chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Analytical-grade methanol, ethanol, and other reagents were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium were purchased from Gibco Inc. (Grand Island, NY, USA). CO2 (purity ≥ 99.99%) was obtained from Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China). Sodium dodecyl sulfate, KH2PO4, and Na2HPO4 were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) and were of analytical grade for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Caco-2 cells were provided by the Cell Bank of Typical Culture Preservation Committee of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Healthy male Sprague-Dawley (SD) mice (200 ± 20 g) and BALB/c-nu mice (20 ± 2 g) were used in this study. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Principles of Animal Care, and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, prior to the study. The animals were supplied by the university’s Laboratory Animal Center and maintained at the hospital’s Animal Research Center. They were housed in standard cages at 25 ± 2 °C and 70 ± 5% relative humidity under natural conditions, with ad libitum access to food and water before the start of the experiments.

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis

AST was quantified on a Waters e2695 HPLC system (Waters Technologies, USA) with a Diamonsil Plus C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase was a mixture of acetonitrile and water (35:65, v/v), with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The detection wavelength was 203 nm, with the column temperature set at 30 °C. The quantified samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm filter membrane prior to automatic injection into the HPLC system.

AST solubilization in SCF-CO2

The solubility of AST was determined according to previous reports [40, 41]. The temperature and pressure ranges set in the experiment were 40–60 ℃ and 9–20 MPa, respectively. First, approximately 200 mg of AST powder was weighed and placed in a saturated kettle with a volume of 50 mL, and CO2 was introduced using a high-pressure pump to remove the remaining air in the kettle. Next, the system was heated to a predetermined temperature, while liquid CO2 was continuously supplied until the specified pressure was reached, allowing the system to stabilize for a period of time. Once the circulating pump was switched on, the AST powder was dissolved under constant desired conditions in contact with SCF-CO2 for approximately 90 min to reach solubility equilibrium. The valves at both ends of the collector were closed. Finally, the collector was disassembled and depressurized using a beaker containing 20 mL methanol, and the drug was dissolved. The collector was washed three times with methanol, and the rinsing solution was combined with the initial methanol solution. The AST concentration was determined using HPLC after diluting the collected solution.

Synthesis of pristine ZIF-8

ZIF-8 was synthesized according to a previously reported procedure with appropriate modifications [42]. In total, 0.60 g Zn (NO3)2•6H2O and 1.32 g 2-MIM were dissolved in a Cillin bottle with 20 mL methanol. The Zn (NO3)2•6H2O solution was then added dropwise to the 2-MIM solution and stirred for 5 min at a stirring speed of 1400 rpm at room temperature. ZIF-8 was spontaneously formed. The product obtained was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min, and the precipitate was washed three times with methanol. The white precipitate was collected and dried in an oven at 80 ℃ overnight to obtain the required ZIF-8.

Encapsulation of AST

SEDS method

The SCF-CO2 device was provided by Nantong Huaxing Petroleum Devices Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China). For the SEDS method, 500 mg of ZIF-8 was placed in a supercritical fluid unit reactor using a magnetic agitator. Once the reactor was closed, CO2 was introduced into the reactor, and the temperature and pressure were constantly adjusted until the reactor reached equilibrium. Subsequently, 10 mL of methanol solution containing different concentrations of AST were delivered into the reactor through a coaxial nozzle using a high-pressure constant flow pump. Simultaneously, a magnetic agitator was used to stir the system in the reactor at a speed of 300 rpm. When this solution was sprayed into the reactor filled with SCF-CO2, rapid diffusion occurred at the SCF-CO2 and solution interface. AST then precipitated and dispersed into ZIF-8 through rapid solvent extraction with SCF-CO2. After the solution injection was complete, the constant flow pump was switched off, and the reactor system was continuously stirred for a period of time. At the end of the process, the reactor was slowly decompressed to normal pressure, and CO2 was injected continuously for approximately 25 min to remove any residual methanol. The samples in the reactor (AST@ZIF-SEDS) were then collected. In this process, the effects of pressure (9–20 MPa), temperature (40–60 ℃), reaction time (20–120 min), and drug concentration (2–50 µg/mL) on the drug loading of AST@ZIF were investigated to optimize the experimental process. AST@ZIF was also prepared using the OPS and SA methods (AST@ZIF-SA) with modifications to optimize the conditions.

OPS method

AST@ZIF-8 was prepared using the OPS method (AST@ZIF-OPS), according to a previous report, with some modifications [43]. In detail, 10 mg of AST and 80 mg of Zn (NO3)2·6H2O were first dissolved in 4 mL of DMSO. The mixture was stirred for 30 min. Subsequently, 6 mL of an aqueous solution containing 800 mg of 2-MIM (Macklin, China) was added dropwise while stirring. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 14 min and subsequently washed three times with methanol to obtain AST@ZIF-8. The product was dried overnight in an oven at 80 ℃.

SA method

AST@ZIF-8 prepared by the SA method (AST@ZIF-SA) was optimized based on our previous experience in the preparation of drug-loaded MOFs [44]. Briefly, 10 mL of a methanol solution containing AST (30 mg/mL) was prepared and placed in 20-mL stopper brown glass bottles for ultrasonic dissolution. Next, 500 mg of blank ZIF-8 was added to the solution, and the mixture was heated on a magnetic stirrer at 55 ℃ with continuous stirring at 300 rpm for 12 h. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged (12000 rpm, 10 min) to collect the precipitate, which was washed three times with methanol. Finally, the product was dried in an oven at 50 ℃ for 12 h.

Determination of drug loading

To determine the weight of AST loaded in the collected AST@ZIF, AST@ZIF-8 was quantitatively weighed and dispersed in an appropriate volume of methanol, followed by ultrasonic treatment in a water bath for 10 min and centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 10 min). The supernatant was diluted with acetonitrile and analyzed using HPLC. This process was repeated three times to ensure complete extraction. The loading capacity of the AST was calculated using the following Eq. (1) [44]:

|

1 |

where WAST and WAST@ZIF were the weights of AST and AST@ZIF, respectively.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy

The morphological characterization of the samples was performed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a S-4800 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan), according to a previous report [42]. An appropriate amount of AST@ZIF-8 was evenly coated on the surface of the conductive adhesive for sample preparation and then placed on the table of the ion sputtering instrument. After the sample was sprayed with gold, its morphology was observed under an appropriate magnification. The particle size of each sample was measured using dynamic light scattering.

Nitrogen adsorption isotherm

The nitrogen adsorption experiment was performed according to the previous report [30]. An ASAP 2460 gas sorption analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA) was used to determine the specific surface areas and pore capacities of the samples. Approximately 200 mg of each sample was weighed and placed in a tube. The sample was degassed under vacuum (10−5 Torr) at 60 ℃ for 12 h before determination, and the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of the sample was measured in a liquid nitrogen bath (77 K).

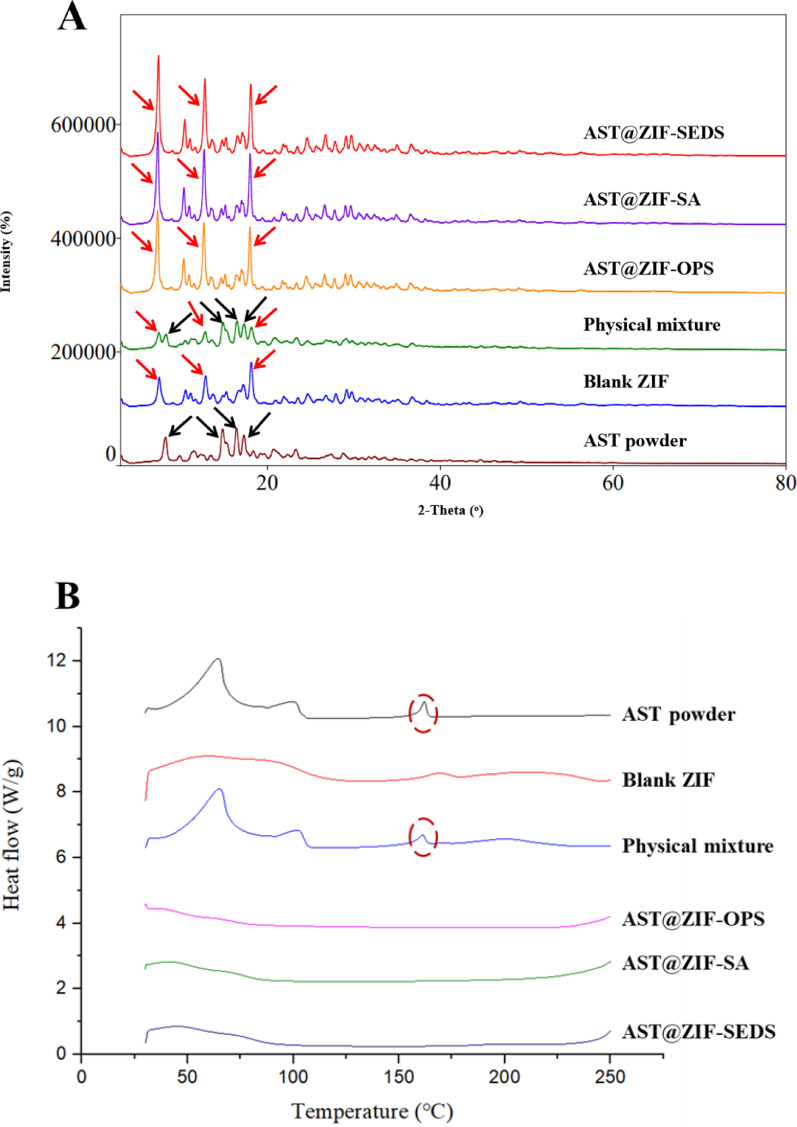

X-ray diffraction and differential scanning calorimetry

X-ray diffraction (XRD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were performed as reported previously [50]. An Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) was used for the crystallographic analysis of the samples. All the samples were irradiated by Cu-Kα radiation, with a tube voltage, tube current, scanning speed, and scanning angle range of 40 kV, 40 mA, 5 °/min, and 3–80°, respectively.

The samples were analyzed by temperature programming using a DSC 3 differential scanning calorimeter (Mettler-Toledo, Switzerland). The sample was placed in an aluminum crucible and heated from 30 ℃ to 300 ℃ at a heating rate of 10 ℃/min with a nitrogen flow rate of 30 mL/min.

Investigation of residual solvent

Residual solvent was investigated according to a previously published method [45]. The amount of residual methanol in AST@ZIF was determined using gas chromatography. An Agilent 7890 A gas chromatography system (California, USA) and an Agilent 19,091 N-2131 HP-INNOWAX gas chromatography column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.50 μm) were employed, using nitrogen as the carrier gas. The 15:1 split mode was used, while the injection port was operated at 200 ℃. The initial oven temperature was held at 40 ℃ for 1 min and then increased to 60 ℃ at a heating rate of 4 ℃/min, followed by an increase to 144 ℃ at 12 ℃/min for 1 min. The temperature of the hydrogen flame ionization detector was set at 220 ℃.

Stability study

The accelerated stability of the AST@ZIFs obtained using different preparation methods was evaluated by analyzing the numerical changes in particle size and drug loading over 6 months. The AST@ZIFs were placed at a temperature of 40 ± 2 ℃ and a relative humidity of 75 ± 5% for an accelerated test. Samples were collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 6-month time points.

Apparent solubility and in vitro dissolution test

Excess amounts of AST powder and AST@ZIF samples were added to 20-mL sealed glass vials, followed by the addition of 10 mL of each of the following solutions: purified water, pH 1.2 HCl solution, pH 6.8 phosphate buffer, and pH 7.4 phosphate buffer. The vials were transferred to a water bath shaker at 25 ℃ with a rotating speed of 100 rpm for 72 h. After equilibrium was reached, the samples were centrifuged and filtered through a 0.45-µm syringe filter. The filtrate was diluted with the same medium, and the concentration of AST was determined using HPLC to calculate the apparent solubility.

The in vitro release profile of AST was determined using the dialysis method [33]. To simulate the release of drugs in the body after oral administration, we used three release media with different pH values to simulate the release process of drugs under different pH physiological conditions in the human body. AST (5 mg) and equivalent AST@ZIF were placed in a cellulose membrane dialysis bag (molecular cutoff, 8–14 kDa) and dispersed in 1 mL of the release media. The dialysis bag was then immersed in 50 mL of pH 1.2 HCl solution (containing 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, w/w) and released for 2 h at 37 °C under constant stirring at 100 rpm. Thereafter, the dialysis bag was transferred to phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and released for 4 h. Finally, the pH of the phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was adjusted to 6.8 with phosphoric acid solution. One milliliter of release medium was then withdrawn at predetermined time points, and an equal volume of release medium at the same temperature was added simultaneously. The amount of AST released was determined using HPLC.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effects of the samples on intestinal and lung cell lines were assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Caco-2 cells were used to evaluate the in vitro intestinal toxicity of the samples, whereas A549 cells were tested for their susceptibility to the lung cancer cytotoxic effects of the samples. Both cell types were diluted to a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL and inoculated into 96-well plates. Then, various concentrations of blank ZIF-8, AST powder, and AST@ZIF were added to the 96-well plates. Following a 48-h incubation, 20 µL of CCK-8 was added to each well, and plates were incubated for an additional 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an Infinite M200 PRO microplate reader (Männedorf, Switzerland). The growth inhibition rate of Caco-2 and A549 cells was subsequently calculated based on these measurements.

In vivo pharmacokinetic study

For the pharmacokinetic study, 24 male SD rats, with body weights of 200 ± 20 g, were randomly divided into four groups. The mice were subjected to fasting for 12 h before the experiment, with free access to water. AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS were administered orally at a dose of 50 mg/kg [46]. Five hundred microliters of blood were collected from the eye socket vein into a 1.5-mL heparinized centrifuge tube at predetermined time points and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to separate the plasma. Plasma was extracted three times with a mixed solvent of ethyl acetate and n-butyl alcohol (95:5, v/v). The collected supernatant was dried using nitrogen at room temperature, and the residue was re-dissolved with 100 µL of methanol. The sample was centrifuged (12000 rpm, 10 min), and 20 µL was injected into an HPLC column for analysis.

Tissue distribution

Male BALB/c nude mice were reared for 7 days under specific pathogen-free conditions, followed by the subcutaneous injection of 200 µL of A549 cells, at a density of 5 × 106 cells/mL, into the right forelimb. The lengths and diameters of the transplanted tumors were measured using Vernier calipers. After tumor volumes reached approximately 80 mm3, mice were randomly divided into four groups (six per group), and each group received an oral dose of 40 mg/kg of AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, or AST@ZIF-SEDS [16]. After 12 h, the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and tumors of all mice were removed and stored at −80 ℃. AST concentrations in these tissues were subsequently measured using HPLC after protein precipitation.

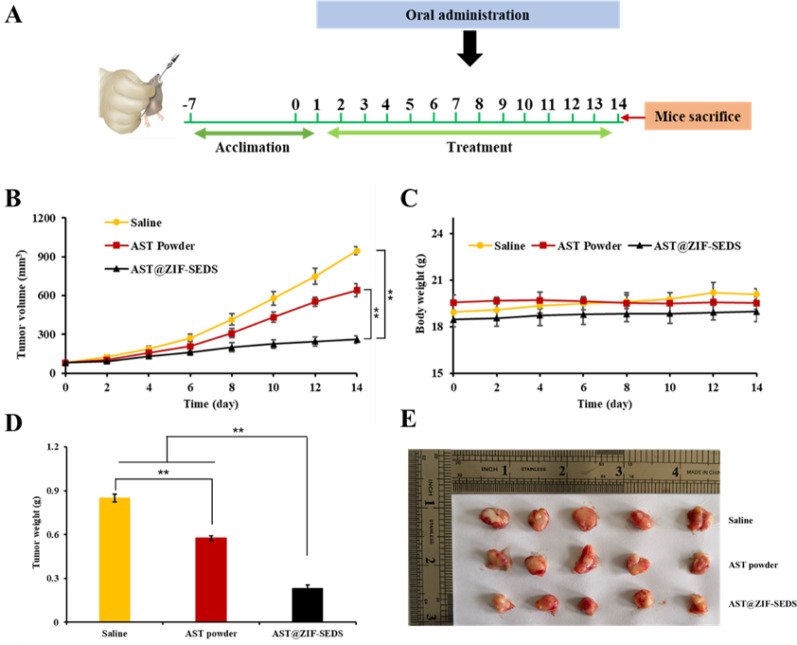

In vivo anti‑tumor activity

For determining in vivo anti-tumor activity, the tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into three groups (six animals/group) when the tumor volumes reached approximately 80 mm3. Group I (control group) received normal saline. Groups II and III were orally administered AST powder and AST@ZIF-SEDS, respectively, at a dose of 40 mg/kg AST per day for 14 consecutive days. All mice were sacrificed on day 14 after the last administration. The tumors were removed from all the mice, weighed, and photographed.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Pharmacokinetic parameters were analyzed using DAS 2.0 software (BioGuider Co., Shanghai, China). The statistical significance of the differences was tested using a one-way analysis of variance with SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 or P < 0.01.

Results

Solubility determination of AST

In the process of extraction and granulation using supercritical fluid technology, the solubility of substances in the supercritical fluid is a crucial factor in the experimental design. SEDS technology uses SCF-CO2 as the anti-solvent to prepare particles, requiring limited solubility of the solute in the SCF-CO2 to enable rapid precipitation. Therefore, to determine the feasibility of preparing AST@ZIF-SEDS, the solubility of AST in SCF was initially determined under different temperature and pressure conditions. Figure 2 shows the effects of pressure and temperature on the solubility of AST in SCF-CO2. The solubility of AST varied depending on the operating conditions. The solubility of AST increased with increasing pressure at the temperatures measured in the experiment. This could be attributed to the increasing density of CO2 with increasing pressure, thus enhancing the solvation performance of SCF-CO2. Under similar pressure conditions, solubility improved with the increase in temperature, except at 9 MPa. This phenomenon indicates that temperature has two opposite effects on solubility at this pressure (9 MPa), which has also been previously reported [47]. When the temperature increased, the density of supercritical CO2 decreased, and the solvation performance of SCF-CO2 decreased. However, the saturated vapor pressure of AST increased, which favored the increasing solubility. At 9 MPa, the intense competition between these two effects prevented a stable trend in the AST solubility. However, under high-pressure conditions, the change in AST saturated vapor pressure was the dominant factor. In summary, the solubility of AST varied from 0.211 mg/mol to 1.84 mg/mol under the range of experimental conditions. The low solubility of AST in SCF-CO2 indicates the feasibility of preparing AST@ZIF-SEDS.

Fig. 2.

Solubility of AST in SCF-CO2 as a function of (A) pressure, and (B) temperature

Preparation of AST@ZIF

To obtain greater drug loading, the effects of temperature, pressure, reaction time, and drug concentration on drug loading during SEDS preparation were investigated (Fig. 3). When other conditions remained unchanged, drug loading was positively correlated with an increase in the system temperature (Fig. 3A). When the system temperature was 50 ℃, the drug loading no longer increased, indicating the optimal preparation temperature. Drug loading increased with an increase in pressure (Fig. 3B). Maximum drug loading was observed when the system pressure reached 20 MPa (close to the upper limit of the instrument pressure). Therefore, 20 MPa was selected as the preparation pressure for subsequent experiments. Moreover, 60 min was selected as the optimal reaction time. Within a certain range, the loading capacity was significantly increased by increasing the drug concentration (Fig. 3D). With a further increase in drug concentration, the loading capacity of ZIF-8 approached saturation; therefore, the optimal drug concentration was chosen as 30 mg/mL.

Fig. 3.

(A) Influence of temperature, (B) pressure, (C) reaction time, and (D) drug concentration on the drug loading of AST@ZIF-SEDS (Data represents in the form with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01)

The preparation processes of the OPS and SA methods were optimized, and the drug loading of the products was compared with that of AST@ZIF-SEDS. The drug loading of AST@ZIF-OPS and AST@ZIF-SA was 17.70 ± 0.47% and 22.01 ± 0.79%, respectively, while that of AST@ZIF-SEDS was 33.15 ± 0.41%.

Characterization of AST@ZIF

The morphologies of AST@ZIF prepared using different methods were observed using SEM (Fig. 4A). AST@ZIFs were homogeneous hexagonal or cubic crystals with particle sizes of approximately 200 nm. The particle size (Fig. 4B) measurement revealed that AST@ZIF-SEDS had a slightly smaller particle size with a smaller PDI, indicating better dispersion, which is consistent with the SEM results.

Fig. 4.

(A) Scanning electron microscopy images and (B) particle size of AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption results are shown in Fig. 5. The BET surface area and desorption cumulative volume of the pores of blank ZIF-8 were 1483.7 m2/g and 0.519 cm3/g, respectively. The blank ZIF-8 adsorbed a large amount of N2 in the low-pressure region, which proved its microporous adsorption characteristics (Fig. 5A). After loading AST, the specific surface area of AST@ZIF decreased sharply, indicating that the pores of ZIF-8 were occupied by the drug molecules. The specific surface area of AST@ZIF-SEDS was the smallest, indicating a higher drug loading. The pore volume of AST also decreased sharply after drug loading, which is similar to other reports on the drug loading of ZIF-8 (Fig. 5B) [30].

Fig. 5.

(A) N2 adsorption isotherms and (B) pore size distribution of blank ZIF, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS

The XRD pattern (Fig. 6A) revealed a change in the AST crystal properties after loading in the ZIF-8. The AST powder existed in stable crystalline form with significant diffraction peaks at 8.18°, 14.80°, 16.42°, and 17.26°, which were still observed in the physical mixture. After drug loading, the characteristic diffraction peaks of AST were completely absent in AST@ZIFs, whereas the diffraction peaks of blank ZIF-8 at 7.48°, 12.84°, and 18.12° remained unchanged, suggesting that AST exists in an amorphous form in ZIF-8 and is encapsulated by ZIF-8 at the molecular level, resulting in a change from a crystalline to an amorphous state [48, 49].

Fig. 6.

(A) X-ray diffraction patterns and (B) differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of AST powder, physical mixture, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS

To further confirm the physical presence of AST in ZIF-8, the thermal behavior of AST after loading into ZIF-8 was characterized using DSC. As shown in Fig. 6B, AST has a melting point heat absorption peak at 161.833 ℃, indicating that AST powder exists in the form of crystals. All the drug endothermic peaks of AST@ZIF disappeared in the DSC spectra, indicating that the structural orientation of AST crystals changed owing to the successful inclusion of AST in the ZIF-8 pore channel. The AST molecules were distributed in an amorphous state in ZIF-8, which was in agreement with the XRD results [50]. In addition, the amorphous form of AST in AST@ZIF is expected to accelerate drug release and improve bioavailability [51].

Residual solvent

AST is a saponin compound with high polarity. It exhibits poor solubility in most solvents, but demonstrates significantly higher solubility in methanol. Meanwhile, methanol is the most commonly employed solvent in the synthesis of ZIF-8 [52]. Furthermore, ZIF-8 tends to undergo hydrolysis in aqueous or other polar solvents, whereas it remains more stable in methanol [53, 54]. Therefore, methanol was selected as the preferred solvent for the preparation of AST@ZIF-8. However, a significant amount of residual methanol exhibits neurotoxic properties and may lead to serious side effects [55]. Therefore, it was necessary to detect the methanol residues in the samples. The residual methanol concentrations of AST@ZIF-OPS and AST@ZIF-SA were 938.33 ppm and 686.67 ppm, respectively, whereas that of AST@ZIF-SEDS was 93.33 ppm, which is significantly lower. The residual methanol limit value stipulated in the ICH Q3C guidelines is less than 3000 ppm. The results show that SEDS has better solvent removal ability, suggesting that it is a safe and effective preparation technology for drug delivery systems.

Stability test

Stability is an important index for the evaluation of pharmaceutical preparations. The results of the accelerated stability tests (Fig. 7). From month 0 to month 6, the particle sizes of AST@ZIF-SA and AST@ZIF-OPS increased from 196 nm to 211 nm to 263 nm and 313 nm, respectively, whereas drug loading decreased from 22.01% to 19.78% and 17.68% to 13.92%, respectively. However, the particle size and drug loading of AST@ZIF-SEDS showed no significant difference in the changes during this period, which could be attributed to the smaller residual solvent content, which reduced the accumulation of the particles. The better loading of AST into the pores of ZIF-8 by SEDS technology resulted in better drug retention. These two advantages indicate that AST@ZIF-SEDS exhibits improved stability [56, 57].

Fig. 7.

Accelerated stability studies for AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS. The changes in (A) particle size and (B) drug loading from 0 month to 6 month (Data represents in the form with *P < 0.05)

Apparent solubility and in vitro dissolution

The solubility of drugs in physiological media determines the bioavailability of drugs [58]. AST is water-insoluble owing to its lattice energy constraints. Given the steric hindrance effect of ZIF-8 channels, the spatial orientation of AST molecules and the intermolecular force required for recrystallization are restricted, preventing the transformation of amorphous AST into a crystalline state. This enables ZIF-8 to possess a high drug loading capacity and efficiency while also increasing the solubility of AST [59]. The results are shown in Fig. 8A. The apparent solubilities of AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS in purified water increased by 5.28, 6.30, and 7.75 times, respectively, compared to AST powder. The enhancement of equilibrium solubility of drugs by AST loaded onto ZIF-8 could be attributed to a bimolecular mechanism by which AST forms nanoclusters in the large cavity of ZIF-8, which has been validated in previous studies on MOF drug delivery [60, 61]. Furthermore, the solubility of AST varies across different media. The apparent solubility of AST exhibits pH dependence. As pH increases, solubility gradually increases. This phenomenon may be attributed to the presence of multiple hydroxyl groups in the AST molecule, which undergo partial deprotonation under higher pH conditions, thereby moderately enhancing solubility [62]. Moreover, AST@ZIF-SEDS exhibited greater solubility than AST@ZIF-OPS and AST@ZIF-SA, which may have been due to its smaller particle size and higher dispersion.

Fig. 8.

(A) Solubility of AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS in pure water at 25 °C (Data represents in the form with *P < 0.05). (B) The in vitro release curves of samples in different simulated biological fluids

In addition to solubility, the degree and rate of dissolution are important for evaluating the preparation. To simulate the release of various groups of preparations in the human digestive tract, release media of different pH values were used for the in vitro release studies [63]. In the first 2 h, HCl solution at pH 1.2 was used to simulate the human gastric fluid environment, while pH 7.4 medium was used to simulate the pH of human intestinal fluid (pH 6.0–8.0) in the middle 4 h. pH 6.8 medium was used to simulate the neutral pH environment of the intestine in the lower part of the digestive tract during the subsequent release time. The in vitro release curves of the AST powder and AST@ZIF obtained using the different preparation methods are shown in Fig. 8B. AST powder exhibited lower cumulative drug release (less than 13%) in the pH 1.2 simulated gastric fluid release medium for the first 2 h. AST@ZIFs showed relatively rapid drug release in the first 2 h, with a cumulative release of more than 20% in the first 2 h, of which AST@ZIF-SEDS reached more than 30%. After continued release for 4 h in pH 7.4 medium, the cumulative release of AST powder and AST@ZIF-SEDS was approximately 22% and 56%, respectively. At pH 6.8, the drug release from all samples increased slowly with time. Among all the samples, AST@ZIF-SEDS had the highest cumulative release of approximately 93% in 24 h, whereas AST release was 42%. Therefore, the cumulative dissolution and drug release rates of AST significantly improved after loading onto ZIF-8.

In vitro cytotoxicity

Given that the preparation in this study was to be administered orally, Caco-2 cells with structures and functions similar to those of differentiated small intestinal epithelial cells were selected to investigate the cytotoxicity of different preparations. Figure 9A shows that the cell survival rate of all samples in the examined drug concentration range was above 80%, indicating that neither AST powder nor ZIF-8 had significant cytotoxic effects [64]. Moreover, AST loading onto ZIF-8 further reduced the cytotoxicity of the drugs, with AST@ZIF-SEDS showing the least cytotoxicity. At 100 µg/mL, the cell survival rate of AST@ZIF-SEDS reached more than 90%, which was higher than that of AST@ZIF-OPS and AST@ZIF-SA, suggesting improved drug encapsulation and lower solvent residues. These results indicate that AST@ZIF-SEDS has good biocompatibility and is well tolerated in the gastrointestinal tract.

Fig. 9.

Cytotoxicity of (A) Caco-2 cells and (B) A549 cells to AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS

The killing effect of the samples on A549 cells is shown in Fig. 9B. AST powder showed obvious inhibitory activity on the proliferation of A549 cells, and the inhibitory effect increased with the increase of drug concentration. Meanwhile, AST loaded onto ZIF-8 could enhance its killing effect. AST@ZIF-SEDS had the greatest inhibitory effect, possibly due to its smaller particle size and better drug loading effect [35], which increased drug uptake by A549 cells.

Pharmacokinetics study

ZIF-8 has been used to improve the bioavailability of several insoluble drugs [65, 66]. To further investigate the effect of AST loaded onto ZIF-8 using different methods on bioavailability in vivo, the pharmacokinetic behavior of AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS in male SD rats was studied. The mean plasma concentration–time profile is shown in Fig. 10, and the pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in Table 1. The peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC0−∞) of all AST@ZIF groups were significantly higher than those of the AST powder group. Among them, AST@ZIF-SEDS showed the most obvious improvement, which was reflected in its Cmax and AUC0−∞ being 3.06 times and 2.52 times higher than those of the AST powder group, respectively. Therefore, the oral bioavailability of AST was significantly improved with AST@ZIF prepared using SEDS technology. In addition, the time to reach the peak plasma concentration (Tmax) of the AST@ZIF-SEDS group was 0.75 h, which was earlier than that of the AST powder group. The results show that the in vivo absorption trends appeared consistent with in vitro release profiles, suggesting a potential correlation.

Fig. 10.

Mean plasma concentration-time profiles of AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS in SD rats after oral administration

Table 1.

Main Pharmacokinetic parameters of the indicated preparations in SD rats after oral administration (n = 6)

| Formulation of AST | Tmax (h) |

Cmax (µg/mL) |

AUC0−∞ (µg/mL·h) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

AST powder AST@ZIF-OPS AST@ZIF-SA AST@ZIF-SEDS |

1 (1, 1.5) 1 (0.75, 1) 1 (0.75, 1) 0.75 (0.75, 1)* |

0.32 ± 0.04 0.64 ± 0.11* 0.78 ± 0.05* 0.98 ± 0.11* |

3.24 ± 0.35 4.95 ± 0.78* 6.61 ± 0.97* 8.17 ± 0.51* |

Cmax, peak plasma concentration; Tmax, time to reach the peak plasma concentration; AUC0−∞, area under the plasma concentration-time curve. *p < 0.05, compared to the AST powder

Tissue distribution

To investigate the metabolic distribution of samples in vivo after oral administration, the concentration of drugs in various tissues was measured. The results (Fig. 11) showed that the AST powder group was mainly enriched in the liver and kidney but less enriched in tumor tissue. On the contrary, AST@ZIF was mainly enriched in tumor tissue, followed by liver and kidney; the SEDS group had the largest accumulation in tumor tissue. This may be due to a combination of EPR effect and cellular uptake, which is similar to other reports on the drug loading of ZIF-8 [67, 68]. High concentration of drugs in tumor tissue can enhance the efficacy and reduce the occurrence of adverse reactions.

Fig. 11.

Tissue distribution of AST powder, AST@ZIF-OPS, AST@ZIF-SA, and AST@ZIF-SEDS in tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice after oral administration

In vivo anti‑tumor activity

We constructed a lung cancer model of A549 cells to investigate the anti-tumor effects of AST@ZIF-SEDS in vivo. As shown in Fig. 12A, the tumor volume in the normal saline group increased the fastest with time, and AST administration could potentially contribute to inhibiting tumor growth, with a tumor inhibition rate of 32.14%. Compared to the AST powder group, the tumor growth rate of the AST@ZIF-SEDS group was significantly reduced, with a tumor inhibition rate of 72.74%, which was much more effective in inhibiting tumor growth. During the treatment period, the body weights of tumor-bearing nude mice in all groups showed a gradual increasing trend (Fig. 12B), and no significant weight loss occurred, indicating no obvious toxic reaction to the different preparations and the safe range of the dosage. Both the tumor weights (Fig. 12C) and excised tumor photographs (Fig. 12D) indicated that AST@ZIF-SEDS had a better in vivo tumor inhibition effect than AST, possibly because of the increased bioavailability of AST.

Fig. 12.

(A) Drug intervention plan. (B) A549 tumor growth profiles of nude mice in different groups after 14 day treatments (Compared with AST@ZIF-SEDS, **P < 0.01). (C) Body weight change of A549 tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice. (D) Tumor weights of different groups at the end of the 14 day treatments. (E) Images of the excised tumors collected from the different groups at the end of the 14 day treatments

Discussion

In this study, the SEDS technology was applied for the first time to load ZIF-8 with the anti-tumor active ingredient AST, resulting in the successful preparation of a drug delivery system (AST@ZIF-8). AST@ZIF-SEDS exhibits high drug loading capacity, favorable stability, low toxicity, and excellent anti-tumor activity.

The SEDS preparation process requires the drug molecules to have low solubility in the SCF-CO2, thus ensuring drug precipitation and rapid loading into the carrier upon contact. As verified through solubility measurement, AST exhibited extremely low solubility in the SCF-CO2, thus fulfilling the criteria for preparation. AST@ZIF-SEDS exhibited excellent dispersibility and a uniform hexagonal or cubic crystal morphology, consistent with findings reported by Tran et al. [30] and Li et al. [44]. AST@ZIF-SEDS demonstrated better dispersion, higher drug loading, less solvent residue, and better stability than those of conventional drug loading methods, such as OPS and SA. The results of nitrogen adsorption isotherm, XRD, and DSC analyses before and after drug loading indicated the successful loading of AST into ZIF-8. The nitrogen adsorption isotherm results showed that the specific surface area and pore volume of ZIF-8 decreased sharply after drug loading, suggesting effective drug packaging. XRD and DSC results further indicated that AST underwent a transition from a crystalline to an amorphous state within the carrier matrix. The presence of AST in an amorphous form is expected to facilitate faster drug release, as reported in a previous study. The drug loading of AST@ZIF-SEDS reached up to 33.15 ± 0.41%, significantly surpassing that of other drug delivery systems such as liposomes and hydrogels [19, 20], which typically exhibit drug loading below 15%. In clinical applications, high drug loading enhances therapeutic efficiency and reduces required dosages, making it a critical advantage. Stability and safety are also essential parameters for evaluating pharmaceutical formulations. Accelerated stability testing revealed no significant changes in particle size and drug loading of AST@ZIF-SEDS over a 6-month period. Additionally, residual solvent analyses and cytotoxicity assays confirmed the favorable safety profile of AST@ZIF-SEDS.

The poor water solubility of AST significantly limits its clinical efficacy. Therefore, the apparent solubility and in vitro dissolution of the formulation were systematically investigated in this study. The apparent solubility of AST@ZIF-SEDS was significantly higher than that of AST powder. This increase may be attributed to the formation of AST nanoclusters within the large cavities of ZIF-8, a bimolecular mechanism that has been theoretically and experimentally demonstrated in multiple studies on drug delivery systems using ZIF-8 as a carrier [60, 61]. In vitro release studies simulating the human gastrointestinal tract revealed that AST@ZIF-SEDS achieved a cumulative release of approximately 93% within 24 h, whereas the cumulative release of AST powder was only 42%. An enhanced dissolution of AST can significantly influence its bioavailability. Pharmacokinetic results further corroborated this finding, confirming that AST@ZIF-SEDS effectively enhances the oral bioavailability of AST.

The anti-tumor efficacy of AST has been well established, and numerous researchers have explored its incorporation into drug delivery systems to enhance its tumor-suppressing capabilities. For instance, Xu et al. [69] developed a hyaluronic acid-modified polydopamine nanomedicine loaded with AST to inhibit the growth and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer, achieving promising results. However, the drug loading capacity of this formulation is relatively low, necessitating the administration of larger doses, thereby leading to safety concerns. In this study, AST@ZIF-SEDS formulation demonstrated a significantly improved drug loading capacity. Consequently, a more favorable tumor inhibition effect was achieved with a reduced dosage, yielding a tumor inhibition rate as high as 72.74%, with no significant toxic effects.

Of note, the SEDS technique requires the use of low-flow CO2 during the preparation process. Although the hazards and environmental pollution caused by small amounts of CO2 are extremely limited, these issues still warrant attention. For instance, preparation in a relatively enclosed environment may lead to CO2 poisoning in humans [70]. Therefore, adequate ventilation must be maintained in the laboratory during the preparation process to avoid exposure to high concentrations of CO₂. Furthermore, as an emerging particle preparation technique, SEDS technology still faces several challenges in practical applications. These include high equipment requirements and significant sensitivity to temperature and pressure conditions [71]. Additionally, fundamental research on this technology remains insufficient, and large-scale industrial production has not yet been realized [72]. With the advancement of related disciplines and continued investigation into such methodologies, SEDS technology is expected to achieve broader application prospects in the field of pharmaceutical formulation due to its distinctive advantages.

Conclusion

In this study, AST@ZIF-8 was synthesized using SEDS technology, followed by a comprehensive evaluation. The results demonstrate that the SEDS technique offers significant advantages over conventional preparation methods. Specifically, the drug loading of AST@ZIF-SEDS reached up to 33.15 ± 0.41%, significantly enhancing the solubility and bioavailability of AST by 7.75-fold and 2.52-fold, respectively, compared to the AST powder. Furthermore, AST@ZIF-SEDS maintains good stability and safety, and its anti-tumor effect is superior to that of AST powder, with a tumor inhibition rate as high as 72.74%. However, certain limitations exist in the preparation and application of AST@ZIF-SEDS. For instance, using methanol as a solvent during the synthesis process may lead to potential toxicity and adverse effects. Moreover, improper handling of CO₂ in the SEDS process could pose operational safety risks. Additionally, the SEDS technique requires stringent preparation conditions, which currently hinders scalability and large-scale industrial production. Therefore, the clinical translation of AST@ZIF-SEDS faces the above-mentioned challenges that require further in-depth study. In conclusion, this study presents a novel strategy for loading ZIF-8 with insoluble drugs using SEDS technology to improve the solubility and bioavailability of drugs, offering promising insights for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of anti-tumor drugs.

Acknowledgements

All the authors are grateful for their assistance from the following research platforms: Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai Chenguan Technology Development Co., LTD, Yantai Institute of Pharmaceutical Science.

Author contributions

YFY and GY conceived and designed the study. GY, JYC, and CAG conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. GY, JYC, CAG, RW, LH, JW, and MYC conducted the data analysis. YFY supervised all aspects of the work. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 82204768, 82102902, and 81903141).

Data availability

The raw and processed data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted by adhering to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 8023, revised 1978). All experimental protocols were confirmed by the Institutional Review and Ethics Board of Ninth People’s Hospital, affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Consent to publish

All the listed authors have participated in the study, and have approved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gang Yang, Ji-Yuan Chen and Chun-Ai Gong contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Meyer ML, Fitzgerald BG, Paz-Ares L, Cappuzzo F, Jänne PA, Peters S, et al. New promises and challenges in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2024;404:803–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorin M, Prosty C, Ghaleb L, Nie K, Katergi K, Shahzad MH, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for nsclc: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10:621–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinfort DP, Kothari G, Wallace N, Hardcastle N, Rangamuwa K, Dieleman EMT, et al. Systematic endoscopic staging of mediastinum to guide radiotherapy planning in patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (SEISMIC): an international, multicentre, single-arm, clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12:467–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roeland EJ, Fintelmann FJ, Hilton F, Yang R, Whalen E, Tarasenko L, et al. The relationship between weight gain during chemotherapy and outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2024;15:1030–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaunzwa TL, Qian JM, Li Q, Ricciuti B, Nuernberg L, Johnson JW, et al. Body composition in advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10:773–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong WZ, Yan HH, Chen KN, Chen C, Gu CD, Wang J, et al. Erlotinib versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant treatment of stage IIIA-N2 EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer: final overall survival analysis of the EMERGING-CTONG 1103 randomised phase II trial. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SM, Schulz C, Prabhash K, Kowalski D, Szczesna A, Han B, et al. First-line atezolizumab monotherapy versus single-agent chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer ineligible for treatment with a platinum-containing regimen (IPSOS): a phase 3, global, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;402:451–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borghaei H, de Marinis F, Dumoulin D, Reynolds C, Theelen WSME, Percent I, et al. Sapphire: phase III study of sitravatinib plus nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou C, Chen G, Huang Y, Zhou J, Lin L, Feng J, et al. Camrelizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed as first-line treatment for advanced nonsquamous NSCLC: extended follow-up of camel phase 3 trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18:628–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Z, Xiao Z, Yu L, Liu J, Yang Y, Ouyang W. Tumor-associated macrophages in non-small-cell lung cancer: from treatment resistance mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;196:104284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memon D, Schoenfeld AJ, Ye D, Fromm G, Rizvi H, Zhang X, et al. Clinical and molecular features of acquired resistance to immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2024;42:209–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Chen Z, Chen L, Dong Q, Yang DH, Zhang Q, et al. Astragali radix (Huangqi): a time-honored nourishing herbal medicine. Chin Med. 2024;19:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salehi B, Carneiro JNP, Rocha JE, Coutinho HDM, Morais Braga MFB, Sharifi-Rad J, et al. Astragalus species: insights on its chemical composition toward pharmacological applications. Phytother Res. 2021;35:2445–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang Y, Chen B, Liang D, Quan X, Gu R, Meng Z, et al. Pharmacological effects of Astragaloside iv: a review. Molecules. 2023;28:6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen T, Yang P, Jia Y. Molecular mechanisms of astragaloside–IV in cancer therapy (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2021;47:13. 10.3892/ijmm.2021.4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu F, Cui WQ, Wei Y, Cui J, Qiu J, Hu LL, et al. Astragaloside IV inhibits lung cancer progression and metastasis by modulating macrophage polarization through AMPK signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xi Y, Wang W, Ma L, Xu N, Shi C, Xu G, et al. Alendronate modified mPEG-PLGA nano-micelle drug delivery system loaded with Astragaloside has anti-osteoporotic effect in rats. Drug Deliv. 2022;29:2386–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao X, Sun L, Wang J, Xu X, Ni S, Liu M, et al. Nose to brain delivery of Astragaloside IV by β-asarone modified Chitosan nanoparticles for multiple sclerosis therapy. Int J Pharm. 2023;644:123351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yue G, Wang C, Liu B, Wu M, Huang Y, Guo Y, et al. Liposomes co-delivery system of doxorubicin and Astragaloside IV co-modified by folate ligand and octa-arginine polypeptide for anti-breast cancer. RSC Adv. 2020;10:11573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng X, Zhang T, Wu Y, Wang X, Liu R, Jin X. mPEG-CS-modified flexible liposomes-reinforced thermosensitive sol-gel reversible hydrogels for ocular delivery of multiple drugs with enhanced synergism. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2023;231:113560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vodyashkin AA, Sergorodceva AV, Kezimana P, Stanishevskiy YM. Metal-organic framework (MOF)-a universal material for biomedicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frouhar E, Adibifar A, Salimi M, Karami Z, Shadmani N, Rostamizadeh K. Novel pH-responsive alginate-stabilized curcumin-selenium-ZIF-8 nanocomposites for synergistic breast cancer therapy. J Drug Target. 2024;32:444–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li N, Xie L, Wu Y, Wu Y, Liu Y, Gao Y, et al. Dexamethasone-loaded zeolitic imidazolate frameworks nanocomposite hydrogel with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects for periodontitis treatment. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16:100360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, Sudlow G, Wang Z, Cao S, Jiang Q, Neiner A, et al. Metal-organic framework encapsulation preserves the bioactivity of protein therapeutics. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7:e1800950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajaj T, Singh C, Gupta GD. Novel metal organic frameworks improves solubility and oral absorption of mebendazole: physicochemical characterization and in vitro-in vivo evaluation. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;70:103264. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anggraini S, Prasetija KA, Yuliana M, Wijaya CJ, Bundjaja V, Angkawijaya AE, et al. pH-responsive hollow core zeolitic-imidazolate framework-8 as an effective drug carrier of 5-fluorouracil. Mater Today Chem. 2023;27:101277. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mi X, Hu M, Dong M, Yang Z, Zhan X, Chang X, et al. Folic acid decorated zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) loaded with Baicalin as a nano-drug delivery system for breast cancer therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:8337–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou R, You Y, Zha Z, Chen J, Li Y, Chen X, et al. Biotin decorated celastrol-loaded ZIF-8 nano-drug delivery system targeted epithelial ovarian cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;167:115573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin S, Du X, Wang K, Wang D, Zheng J, Xu H, et al. Vitamin A-modified ZIF-8 lipid nanoparticles for the therapy of liver fibrosis. Int J Pharm. 2023;642:123167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran VA, Lee SW. Ph-triggered degradation and release of doxorubicin from zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF8) decorated with polyacrylic acid. RSC Adv. 2021;11:9222–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proenza YG, Longo RL. Simulation of the adsorption and release of large drugs by ZIF-8. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60:644–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng S, Zhang X, Shi D, Wang Z. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) for drug delivery: a critical review. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2021;015:221–37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Liang X, Peng Y, Liu G, Cheng HW. Supercritical fluids: an innovative strategy for drug development. Bioengineering. 2024;11:788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu W, Long J, Shi M. Resveratrol-loaded diacetate fiber by supercritical CO2 fluid assisted impregnation. Materials. 2022;15:5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.He Y, Hou X, Guo J, He Z, Guo T, Liu Y, et al. Activation of a gamma-cyclodextrin-based metal-organic framework using supercritical carbon dioxide for high-efficient delivery of Honokiol. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;235:115935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Zhang S, Deng Z, Zhang Y, Jiao Z. Preparation of curcumol-loaded magnetic metal-organic framework using supercritical solution impregnation process. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023;357:112612. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monteagudo-Olivan R, Cocero MJ, Coronas J, Rodríguez-Rojo S. Supercritical CO2 encapsulation of bioactive molecules in carboxylate based MOFs. J CO2 Util. 2019;30:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar R, Thakur AK, Kali G, Pitchaiah KC, Arya RK, Kulabhi A. Particle preparation of pharmaceutical compounds using supercritical antisolvent process: current status and future perspectives. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023;13:946–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gholivand S, Tan TB, Yusoff MM, Choy HW, Teow SJ, Wang Y, et al. Advanced fabrication of complex biopolymer microcapsules via RSM-optimized supercritical carbon dioxide solution-enhanced dispersion: a comparative analysis of various microencapsulation techniques. Food Chem. 2024;452:139591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia J, Zabihi F, Gao Y, Zhao Y. Solubility of glycyrrhizin in supercritical carbon dioxide with and without cosolvent. J Chem Eng Data. 2015;60:1744–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang G, Li Z, Shao Q, Feng N. Measurement and correlation study of Silymarin solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide with and without a cosolvent using semi-empirical models and back-propagation artificial neural networks. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2017;12:456–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Liu S, Wu Y, Xu X, Li Q, Yang M, et al. Curcumin doped zeolitic imidazolate framework nanoplatforms as multifunctional nanocarriers for tumor chemo/immunotherapy. Biomater Sci. 2022;10:2384–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu H, Liu Y, Chen L, Wang S, Liu C, Zhao H, Jin M, Chang S, Quan X, Cui M, Wan H, Gao Z, Huang W. Combined biomimetic MOF-RVG15 nanoformulation efficient over BBB for effective anti-glioblastoma in mice model. Int J Nanomed. 2022;17:6377–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Z, Yang G, Wang R, Wang Y, Wang J, Yang M, et al. γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic framework as a carrier to deliver triptolide for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12:1096–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun R, Hu C, Dou Q, Luan L. Simultaneous determination of nine residual solvents in Sorafenib Tosylate by gas chromatography. J AOAC Int. 2021;104(4):1005–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun S, Liu L, Song H, Li H. Pharmacokinetic study on the co-administration of abemaciclib and Astragaloside IV in rats. Pharm Biol. 2022;60:1944–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin J, Ning YY, Hu K, Wu H, Zhang Z. Solubility of p-nitroaniline in supercritical carbon dioxide with and without mixed cosolvents. J Chem Eng Data. 2013;58:1464–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazloum-Ardakani M, Shaker-Ardakani N, Ebadi A. Development of metal-organic frameworks (ZIF-8) as low-cost carriers for sustained release of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs: in vitro evaluation of anti-breast cancer and anti-infection effect. J Clust Sci. 2023;34:1861–76. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Han X, Qin XY, Zhang Y, Guo N, Zhu HL, et al. A solid preparation of phytochemicals: improvement of the solubility and bioavailability of Astragaloside IV based on β-cyclodextrin microencapsulation. Chem Pap. 2023;77:6491–503. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun R, Zhang A, Ge Y, Gou J, Yin T, He H, et al. Ultra-small-size Astragaloside-IV loaded lipid nanocapsules eye drops for the effective management of dry age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020;17:1305–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Z, Lv Y, Zheng G, Wu W, Che X. Chitosan/polylactic acid nanofibers containing Astragaloside IV as a new biodegradable wound dressing for wound healing. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2023;24:202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park KS, Ni Z, Côté AP, Choi JY, Huang R, Uribe-Romo FJ, et al. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang HX, Zhao M, Lin YS. Stability of ZIF-8 in water under ambient conditions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019;279:201–10. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fairen-Jimenez D, Moggach SA, Wharmby MT, Wright PA, Parsons S, Düren T. Opening the gate: framework flexibility in ZIF-8 explored by experiments and simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8900–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rafizadeh A, Bhalla A, Sharma N, Kumar K, Zamani N, McDonald R, et al. Evaluating new simplified assays for harm reduction from methanol poisoning using chromotropic acid kits: an analytical study on Indian and Iranian alcoholic beverages. Front Public Health. 2022;10:983663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kias F, Bodmeier R. Acceleration of final residual solvent extraction from poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles. Pharm Res. 2024;41(9):1869–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shim H, Sah H. Qualification of non-halogenated organic solvents applied to microsphere manufacturing process. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y, Liang Y, Yuhong J, Xin P, Han JL, Du Y, Yu X, Zhu R, Zhang M, Chen W, Ma Y. Advances in nanotechnology for enhancing the solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2024;18:1469–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng J, Liu Y, Wang M, Huang S, Liu M, Zhou Y, et al. Synthesis, crystal structures, and mechanochromic properties of bulky trialkylsilylacetylene-substituted aggregation-induced-emission-active 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives. Dyes Pigments. 2020;174:108094. [Google Scholar]

- 60.He Y, Zhang W, Guo T, Zhang G, Qin W, Zhang L, et al. Drug nanoclusters formed in confined nano-cages of CD-MOF: dramatic enhancement of solubility and bioavailability of Azilsartan. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu J, Wu L, Guo T, Zhang G, Wang C, Li H, et al. A ship-in-a-bottle strategy to create folic acid nanoclusters inside the nanocages of γ-cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks. Int J Pharm. 2019;556:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurnia KA, Harimurti S, Yung HK, Baraheng A, Alimin MA, Dagang M, et al. Understanding the effect of pH on the solubility of Gamavuton-0 in the aqueous solution: experimental and COSMO-RS modelling. J Mol Liq. 2019;296:111845. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hussain A, Shakeel F, Singh SK, Alsarra IA, Faruk A, Alanazi FK, et al. Solidified SNEDDS for the oral delivery of rifampicin: evaluation, proof of concept, in vivo kinetics, and in silico GastroPlus™ simulation. Int J Pharm. 2019;566:203–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diaz-Morales N, Cavia-Saiz M, Salazar G, Rivero-Pérez MD, Muñiz P. Cytotoxicity study of bakery product melanoidins on intestinal and endothelial cell lines. Food Chem. 2021;343:128405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai Y, Guan J, Wang W, Wang L, Su J, Fang L. pH and light-responsive polycaprolactone/curcumin@zif-8 composite films with enhanced antibacterial activity. J Food Sci. 2021;86:3550–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu Z, Zhang Y, Lu D, Zhang G, Li Y, Lu Z, et al. Antisenescence ZIF-8/resveratrol nanoformulation with potential for enhancement of bone fracture healing in the elderly. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023;9:2636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin W, Gong J, Ye W, Huang X, Chen J. Polyhydroxy fullerene-loaded ZIF‐8 nanocomposites for better photodynamic therapy. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 2020;24:1900–3. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang K, Cai M, Yin D, Zhu R, Fu T, Liao S, et al. Functional metal–organic framework nanoparticles loaded with polyphyllin I for targeted tumor therapy. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices. 2023;8:100548. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu F, Li M, Que Z, Su M, Yao W, Zhang Y, et al. Combined chemo-immuno-photothermal therapy based on ursolic acid/astragaloside IV-loaded hyaluronic acid-modified polydopamine nanomedicine inhibiting the growth and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11:3453–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura A, Ninomiya K, Fukasawa M, Ikematsu N, Kawakami Y. Accidental carbon dioxide poisoning due to dry ice during a funeral wake: an autopsy case. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2023;64:102298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Badens E, Masmoudi Y, Mouahid A, Crampon C. Current situation and perspectives in drug formulation by using supercritical fluid technology. J Supercrit Fluids. 2018;134:274–83. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu H, Liang X, Peng Y, Liu G, Cheng H. Supercritical fluids: an innovative strategy for drug development. Bioengineering. 2024;11(8):788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw and processed data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.