Abstract

In multicellular organisms, developmental programmes must integrate with central cell cycle regulation to co-ordinate developmental decisions with cell proliferation. Hyperplasia caused by deregulated proliferation without significant change to other aspects of developmental behaviour is a probable step towards full oncogenesis in many malignancies. CDC25 phosphatase promotes progression through the eukaryotic cell cycle by dephosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase and, in humans, different cdc25 family members have been implicated as potential oncogenes. Demonstrating the direct oncogenic potential of a cdc25 gene, we identify a gain-of-function mutant allele of the Caenorhabditis elegans gene cdc-25.1 that causes a deregulated proliferation of intestinal cells resulting in hyperplasia, while other aspects of intestinal cell function are retained. Using RNA-mediated interference, we demonstrate modulation of the oncogenic behaviour of this mutant, and show that a reduction of the wild-type cdc-25.1 activity can cause a failure of proliferation of intestinal and other cell types. That gain and loss of CDC-25.1 activity has opposite effects on cellular proliferation indicates its critical role in controlling C.elegans cell number.

Keywords: cdc25/cell cycle/C.elegans/development/oncogene

Introduction

The Caenorhabditis elegans intestine consists of 20 cells, all of which are derived, by a largely invariant pattern of cell divisions during early embryogenesis, from the single blastomere E (see Figure 2) (Sulston et al., 1983). These are the only cells derived from the E blastomere and represent the entire C.elegans endoderm. The E blastomere and its sister cell MS present in the 8-cell C.elegans embryo are the daughters of the blastomere EMS. E and MS have distinct developmental fates, E giving rise exclusively to endodermal cells and MS giving rise primarily to mesodermal cells. The developmental asymmetry between the E and MS sisters requires an inductive polarizing signal to the parental cell EMS from another blastomere named P2 (Goldstein, 1992, 1995). In the absence of the P2 signal, both daughters of EMS adopt MS-like fates, thus the P2 signal is required to specify the endodermal fate of the E blastomere. Several maternal genes have been identified that are necessary for the correct specification of E and MS fates. These include the gene mom-2, a C.elegans homologue of Wnt required for the P2-derived induction of the E fate, and pop-1, which encodes an HMG domain protein, required for the correct specification of MS fates (Lin et al., 1995; Han, 1997; Rocheleau et al., 1997; Thorpe et al., 2000).

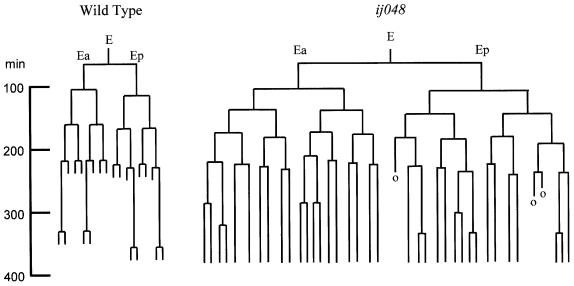

Fig. 2. The E cell lineage in wild type and cdc-25.1(ij48). Timing of cell cleavages in minutes, derived from the E blastomere. The invariant pattern of cleavages for wild type and one example of the variant pattern of the cdc-25.1(ij48) mutant are given. The cells marked ‘o’ could not be followed in the recording. There are no further cell divisions in the wild-type E lineage. We recorded to ∼400 min of embryonic development; any cleavages beyond this time in the mutant would not be detected.

Two genes encoding GATA transcription factors, end-1 and elt-2, have been identified involved in the normal execution of endodermal fate and hence acting downstream of the maternal E specification genes (Zhu et al., 1997; Fukushige et al., 1998). Both of these genes are expressed zygotically, the transcript of end-1 being detected first within the E blastomere itself and elt-2 one cell division later at the two-E cell stage. Genetic evidence suggests that they are likely constituents of a partly redundant network controlling endodermal fate in C.elegans, which may be conserved amongst all metazoans (Fukushige et al., 1998). Possible roles for the encoded transcription factors include the establishment and maintenance of endodermal patterns of gene expression. Various structural genes whose expression is restricted to the C.elegans intestine have multiple copies of GATA-like response elements within their 5′ regulatory regions (Larminie and Johnstone, 1996; Britton et al., 1998), and ectopic expression of elt-2 can induce the transcription of some intestine-specific structural genes in cells outside the E lineage.

Between the specification of the E blastomere itself and the execution of terminal fate in the 20 cells of the developed intestine is the precise pattern of cell divisions by which these 20 cells are born from E. Although all 20 intestinal cells express many common aspects of C.elegans endodermal fate, clearly 20 cells cannot be derived from a single progenitor by an identical pattern of cell divisions. At ∼300 min of development (Figure 2), the developing intestine consists of 16 cells, 12 of which undergo no further cell division and four of which undergo one further division, thus producing 20 cells. Thus there is asymmetry within the E cell lineage, some cells exiting the cell cycle one division before their sisters. Ultimately, this must involve the differential regulation of common central cell cycle regulators within sister cells, thus the C.elegans intestine offers a tractable system for a study of interactions between a developmental programme specifying differences between cells and common elements of the animal cell cycle. The central components of the animal cell cycle are the Cdc2-like cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdc2/cdks) and their associated cyclins (Morgan, 1995). Regulators of the Cdc2/cdks include the negative acting WEE1 kinase that provides inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdc2/cdks and its antagonist CDC25 phosphatase that removes negative acting phosphates from the Cdc2/cdks (Russell and Nurse, 1987; Featherstone and Russell, 1991; Kumagai and Dunphy, 1991, 1996; Jessus and Beach, 1992). As with other animals, C.elegans has multiple genes encoding these central cell cycle regulators; it has three wee-1 and four cdc-25 homologues, respectively. One possible point where specific developmental programmes may interface with the control of the cell cycle is the WEE1–CDC25 antagonistic partnership.

There are further differences in the pattern of DNA replication between different intestinal cells during post-embryonic development. Late in L1 larval development, most of the 14 more posterior intestinal cells, but not the six more anterior cells, undergo a nuclear division without cell division, producing binucleate cells (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977), and at the end of each larval stage most intestinal cell nuclei undergo endoreduplication such that the nuclei of the adult intestine have a typical ploidy of 32N (Hedgecock and White, 1985).

In an attempt to identify genes acting downstream of those necessary to specify E and involved in controlling the highly regulated pattern of cell and nuclear divisions of the E lineage, we used a standard genetic approach of performing mutant screens to detect animals with altered numbers of intestinal nuclei.

Results

Identification of C.elegans mutants with extra intestinal cells

The C.elegans strain IA109 (ijIs10) that carries an integrated cpr-5::gfp transgene was used for mutant screens. cpr-5 is a cysteine protease gene (Larminie and Johnstone, 1996) expressed specifically in the C.elegans intestine during larval and adult stages of development and acts as a marker for post-embryonic intestinal cell fate. The transgene causes green fluorescent protein (GFP) to be expressed specifically in intestinal cells; it is localized to nuclei by a nuclear localization signal present in the GFP (Figure 1B). This pattern of GFP expression was used to facilitate the detection of mutants with altered numbers of intestinal nuclei in post-embryonic development. As observations were made only on late larval and adult stages, mutants that resulted in embryonic or early larval lethality, such as no endoderm mutants, would not be detected in the screens that we performed. We performed an F2 screen, which permits the detection of either dominant or recessive zygotic mutants, but only dominant maternal mutants. Amongst the classes of mutant obtained were the two alleles ij48 and ij52, which cause the generation of extra intestinal cells during embryogenesis and are viable and fertile as adults. These alleles identify two different genes and display distinct genetic behaviours, the gene identified by allele ij48 acting maternally (see below) while that identified by ij52 is zygotic. The gene identified by ij52 is not discussed further here.

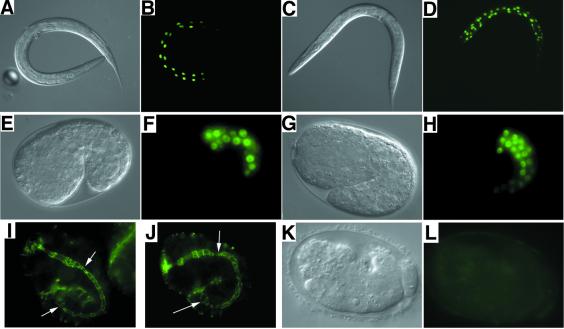

Fig. 1. Intestinal cells in wild type and cdc-25.1(ij48). (A), (C), (E), (G) and (K) are Nomarski images with respective GFP fluorescence counterparts, (B), (D), (F), (H) and (L). In all cases, GFP is localized to the nuclei of cells, in which it is expressed, by a nuclear localization signal. Expression of a cpr-5::gfp transgene in adults in the wild-type (A and B) and cdc-25.1(ij48) (C and D) backgrounds indicates additional intestinal nuclei present in the mutant. The expression of an elt-2::GFP transgene in wild-type (E and F) and cdc-25.1(ij48) (G and H) embryos indicates that extra nuclei expressing this intestinal marker are born during embryogenesis. The number of nuclei expressing this marker in the cdc-25.1(ij48) strain is typically 50–100% greater than wild type. Not all GFP-positive nuclei can be seen in any given focal plane. Immunofluorescence with the MH27 antibody marks the boundaries between various C.elegans epithelial cell types (Francis and Waterston, 1985), shown for embryos at the1.5-fold stage of development: wild-type (I) and cdc-25.1(ij48) (J). White arrows indicate the start and end of the intestine; staining in the pharynx is seen to the anterior (left). There are many more intestinal cell boundaries in cdc-25.1(ij48) by comparison with wild type, and their organization appears chaotic. (K and L) An example of an F1 embryo derived from a mother treated as an adult with cdc-25.1 RNAi by bacterial feeding.

ij48 mutants have additional nuclei expressing the cpr-5::gfp transgene when compared with wild type (Figure 1A–D). This is the result of an intestinal hyperplasia. The extra cells are born during embryogenesis (Figure 1E–H) and many or all of these cells participate in forming a functional intestine, as indicated by the more complex pattern of intestinal cell boundaries in the mutant (Figure 1I and J). Using two different markers of intestinal differentiation observable during embryonic development, an elt-2::GFP transgene (Fukushige et al., 1998) (Figure 1E–H) and an antibody ICB4 (Bowerman et al., 1992) (data not shown), we observe that mutant animals variably generate 30–45 cells expressing these intestinal fate markers during embryogenesis, by comparison with 20 in the wild type. The post-embryonic behaviour of the intestinal cells in the ij48 mutant appears to be relatively normal. The intestine is functional and ij48 animals grow normally and are similar in size to wild type as adults, with no indication of feeding defects. They do not look starved and do not show a tendency to form dauer larvae under standard culture conditions. [The dauer larva is an alternative L3 larval stage formed as a normal response to starvation (Riddle, 1988).] The intestinal nuclei of ij48 mutants increase in size during larval development, indicating rounds of endoreduplication. We do detect one minor difference in the post-embryonic behaviour of the intestinal nuclei in ij48 mutants. The nuclear division that occurs in wild type at the end of the L1 larval stage generating binucleate intestinal cells is delayed. For the five animals observed, no divisions were seen during L1 development but many divisions were observed during the L2 larval stage. The post-embryonic nuclear divisions that take place in the mutant are not synchronous, the process being more varied than in wild type. This may be an indirect effect of the ij48 lesion. Because there is no growth during embryogenesis and there are extra embryonic cell divisions in the E lineage in the mutant, the intestinal cells are smaller at hatch and hence have an altered cytoplasm to DNA ratio. The delay in the post-embryonic nuclear divisions in the intestinal cells could be a consequence of this.

Origin of extra intestinal cells in ij48 mutants

There are two potential explanations for the generation of extra cells during embryogenesis expressing the intestinal fate. They could either be the result of a variable pattern of extra cell divisions within the E lineage itself, or the result of a transformation to the intestinal fate of a variable number of cells from another lineage. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we performed cell lineage analysis of the ij48 mutant. We find many extra divisions of the cells derived from the E blastomere in ij48 mutant animals, sufficient to explain all of the extra cells expressing the intestinal markers (Figure 2). In the E lineage, there is a general shortening of the time between cell divisions in the mutant. Significantly, the E cell lineage in ij48 mutants is very varied between different embryos. Unlike that of almost all wild-type C.elegans somatic tissue development (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Sulston et al., 1983), the ij48 mutation causes the C.elegans intestine to develop by an indeterminate pattern of cell divisions. While strict cell cycle control is lost, other aspects of intestinal differentiation are retained, as indicated by the expression of terminal differentiation markers and by the functional nature of the intestine in mutants. Thus the ij48 defect is proliferative in nature, causing a loss of control of the cell cycle in E lineage cells, without significantly altering other aspects of terminal differentiated fate. As a control, the lineage of the D blastomere was determined in the mutant and found to be as wild-type; thus the proliferative defect caused by the ij48 lesion is not found in all cell types. Evidence that it is restricted to the E lineage is discussed below.

The ij48 allele is semi-dominant over wild type and identifies a maternal gene

The allele ij48 is highly penetrant with respect to the intestinal hyperplasia it causes; almost 100% of the F1 progeny of ij48 homozygotic mothers display the mutant phenotype. This allele shows a strict maternal pattern of inheritance as indicated by the following behaviour. For heterozygotic mothers of genotype ij48/+, the proportion of F1 progeny displaying mutant phenotype was from 22 to 96% in 20 broods analysed. The average was 76%. The F1 progeny are of three potential genotypes, ij48/ij48 homozygotes, ij48/+ heterozygotes and +/+ homozygotes, expected at standard Mendelian frequencies of 1:2:1. To determine whether the zygotic genotype was influencing the phenotype in these animals, we determined the genotype of the F1 progeny for two of the broods analysed. We found no correlation between the zygotic genotype and the outcome of phenotype in these F1 progeny, consistent with a strict maternal behaviour of this gene. Also consistent with its maternal behaviour, when the ij48 allele is mated in from a male, 100% of the F1 progeny display a wild-type phenotype. That the phenotype is observed in a proportion of progeny (<100%) of a heterozygotic mother is indicative of the allele’s partial dominance over wild type. We do not know the reason for the high variance in proportions of broods displaying phenotype from different, but genetically identical, mothers.

Using standard genetic methods, the allele ij48 was mapped to position 1.1 on chromosome I. We placed the allele ij48 over the deficiency hDf8 that maps to this region. For mothers of genotype ij48/hDf8, from 21 broods analysed, an average of 2.5% of the F1 progeny displayed mutant phenotype, compared with an average of 76% (see above) for progeny of ij48/+ mothers and almost 100% for progeny of homozygous ij48/ij48 mothers. That the mutant phenotype is modified by the presence of the deficiency hDf8 is consistent with the gene identified by allele ij48 being covered by this deficiency. We therefore conclude that the ij48/hDf8 heterozygotes are hemizygotic for the mutant copy of the gene identified by allele ij48. Our data indicate that the allele ij48 is a gain of function and it is sensitive to gene dose. Two mutant copies in ij48 homozygotic mutant mothers result in virtually 100% of the F1 progeny displaying the mutant phenotype. When the mutant gene dose is reduced to one in the mother by placing the mutant allele over a deficiency, only 2.5% of the F1 progeny display mutant phenotype. That ij48/+ heterozygotic mothers which have one mutant and one wild-type copy of the gene give 76% F1 progeny with mutant phenotype indicates that the wild-type copy of the gene can contribute together with the ij48 gain-of-function copy to produce extra intestinal cells. We therefore conclude that the allele ij48 is a hypermorph.

Cloning the gene identified by allele ij48

These data suggested a method for cloning the gene identified by allele ij48. The standard route to cloning a gene defined by mutation in C.elegans is to attempt phenotypic rescue with cosmid clones from the genomic region to which the mutation maps. This standard method can only be used for alleles recessive to wild type, and hence was not appropriate here. However, RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) can be used to reduce the amount of functional gene product in C.elegans in a highly gene-specific way (Fire et al., 1998; Timmons and Fire, 1998). When performed on adult C.elegans hermaphrodites, RNAi can reduce or remove the function of the targeted gene in the treated adults, the gene product supplied maternally to embryos and the zygotic function of the gene in the F1 progeny (Fire et al., 1998). In order to define a set of predicted genes that should include the gene defined by allele ij48, we refined its map position in the following way. As the data above indicated that it must be contained within deficiency hDf8, we determined by PCR amplification of genomic DNA sequences that the left-hand break point of this deficiency is between the C.elegans genome project predicted genes R10A10.1 and R10A10.2. By standard multifactorial genetic mapping, we showed ij48 to map to the left of let-607, which is contained within cosmid F57B10; thus the gene identified by ij48 is positioned between cosmid sequence R10A10 and F57B10. In several experiments, we failed to obtain recombination between ij48 and the gene let-604, which also maps to the left of let-607 and within the region covered by deficiency hDf8. We concluded that the gene identified by allele ij48 must be very close to let-604. We were able to demonstrate phenotypic rescue of let-604 with a group of genome project cosmid clones consisting of R10A10, F37E3, T23H2, K06A5 and C55B7, and selected from the predicted genes within these genome sequences a set to test by RNAi as candidates for the gene identified by the ij48 lesion.

We performed RNAi on a homozygotic ij48 strain on the set of selected genes and looked for suppression of the intestinal lineage defect in F1 progeny. We found one gene, previously described as cdc-25.1 (Ashcroft et al., 1998), for which RNAi gave suppression of the ij48 phenotype in a significant percentage of the F1 progeny of treated mothers. Reduction of wild-type cdc-25.1 activity in the developing embryo previously has been shown to cause various cell division defects in the embryo, including the generation of polyploid cells and cytoplasts, and resulting in embryonic lethality (Ashcroft et al., 1999). However, a proportion of the embryos produced by cdc-25.1 RNAi-treated mothers shortly after administration of RNAi survive through embryogenesis but develop into sterile adults, as a result of an incomplete cdc-25.1 RNAi effect during embryogenesis (Ashcroft et al., 1999). It is within this class of F1 survivors that we see suppression of the intestinal hyperplasia when cdc-25.1(ij48) mothers are treated with cdc-25.1 RNAi. In cdc-25.1 RNAi experiments generating F1 progeny of 693 dead embryos and 43 sterile F1 survivors, 18 of these survivors showed complete suppression of the cdc-25.1(ij48) intestinal hyperplasia. That cdc-25.1 RNAi can mimic the reduction of penetrance of phenotype seen when ij48 is placed over a deficiency strongly suggested ij48 to be a gain-of-function allele in cdc-25.1.

We cloned the cdc-25.1 coding sequences from an ij48 homozygotic strain and by sequencing found a single base difference in the cdc25.1 sequence in this genetic background by comparison with wild type. The gene has a single base substitution in the first exon at base 137 relative to ATG, and would cause a serine to phenylalanine substitution at residue 46 of the encoded protein. This is consistent with ij48 being an allele of cdc-25.1. Given the function of CDC25 proteins as positive-acting regulators of the cell cycle (Russell and Nurse, 1986), the ij48 phenotype of hyperplasia is consistent with a gain of function in this class of gene.

Our genetic data are consistent with a single mutation being responsible for the observed phenotype of intestinal hyperplasia. The original strain was backcrossed several times against wild type to remove unlinked mutations; however, this cannot rule out the possibility of a closely linked mutation being responsible or acting co-operatively with the detected lesion in cdc-25.1 to produce the phenotype. During the genetic mapping of ij48, we obtained recombination events on either side of cdc-25.1 and in close proximity to the gene; thus we can rule out anything but a very tightly linked alternative mutation being involved. To confirm that the identified lesion within cdc-25.1 is sufficient on its own to generate, and hence is responsible for, the intestinal hyperplasia, we introduced the mutant cdc-25.1 gene as a transgene into a wild-type strain of C.elegans. This efficiently generated the ij48 intestinal cell hyperplasia in the presence of chromosomal wild-type alleles in a semi-dominant manner, proving its direct oncogenic potential. Thus we conclude that ij48 is an allele of the C.elegans cdc25 homologue, cdc-25.1. As the mutant cdc-25.1(ij48) transgene is sufficient to cause the intestinal hyperplasia when introduced into a wild-type strain, this indicates that there is no requirement for mutation in any other gene in order to cause the oncogenic effect.

cdc-25.1 is required for normal embryonic proliferation of at least two C.elegans cell types

As discussed above, cdc-25.1 is essential in the developing embryo, and reduction of its activity by RNAi causes cell division defects that are not restricted to cells of the E lineage, indicating that the gene functions in other cell types. To confirm that reduction of the wild-type cdc-25.1 activity could have an opposite effect to the ij48 gain-of-function allele with respect to cellular proliferation, we administered cdc-25.1 RNAi to young adult hermaphrodites by the bacterial feeding method (Timmons et al., 2001) and examined their F1 progeny. For some genes, we have found that this method can be used to generate a spectrum of severity of RNAi effects that probably represent varying degrees of reduction of gene product in the treated animals. We used two strains of C.elegans, JR1838, which carries an elt-2::GFP transgene (Fukushige et al., 1998) and permits identification of intestinal cells by GFP expression, and IA105, which carries a dpy-7::GFP transgene (Gilleard et al., 1997), permitting identification of ectodermal cells. With both strains, the RNAi caused embryonic lethality in ∼90% of the F1 progeny of treated mothers, and sterile adults from most of the 10% survivors. The embryonic lethal class displayed a broad spectrum of effects generating variable numbers of cells before death, probably the result of varying degrees of reduction of cdc-25.1 activity by incomplete RNAi. Where a substantial number of cells were born, severe morphological defects were evident (Figure 1K). Using the C.elegans strain JR1838, ∼30% of the dying embryos had no cells expressing the intestinal marker (Figure 1K and L); however, other cell types were born as indicated by movement and partial morphogenesis of the affected embryos. In the remaining 70%, we observed a spectrum of between six and the wild-type 20 intestinal cells. We saw a similar spectrum of between zero and near wild-type numbers of ectodermal cells with cdc-25.1 RNAi performed on the strain IA105. Thus reduction of cdc-25.1 activity by RNAi can cause a reduction in the number of cells expressing intestinal cell fate in the developing embryo. This effect is not restricted to intestinal cells, as indicated by the effect seen on hypodermal cells. We did not test other cell types born during embryogenesis.

cdc-25.1 is essential post-embryonically for C.elegans germline proliferation

The phenocopy of sterility amongst the class of F1 progeny that escape embryonic lethality suggested that cdc-25.1 might also have a post-embryonic role in germline proliferation. These animals have a severe germline proliferation defect. Although RNAi was performed on the mothers, such RNAi can interfere effectively with both maternal and zygotic gene function in the F1 progeny in C.elegans (Fire et al., 1998). To test whether the germline proliferation defect was the result of interference of zygotic cdc-25.1 activity, wild-type embryos were allowed to develop normally and, after hatch, L1 larvae were placed on cdc-25.1 bacterial RNAi lawns and permitted to develop to adults, thus restricting the RNAi effect on these animals to post-embryonic development. More than 90% of these animals developed into sterile adults, indicating that cdc-25.1 has zygotic as well as maternal functions. We find that germline proliferation in these animals is severely reduced by comparison with wild type (Figure 3A and C).

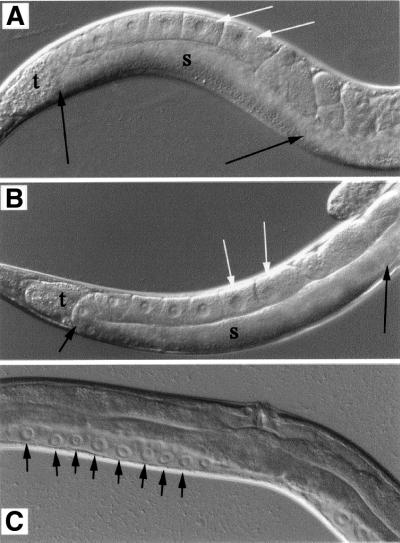

Fig. 3. Gonads of adult hermaphrodites. (A) Wild type and (B) cdc-25.1(ij48). Some developing oocytes are marked with white arrows; the syncytial arm of the gonad is delineated with black arrows and labelled ‘s’. This region contains several hundred germline nuclei in both wild-type and mutant. The turn of the gonad arm is labelled ‘t’. (C) A similar region of the anatomy of a sterile adult generated by post-embryonic cdc-25.1 RNAi by bacterial feeding. Individual germline nuclei are marked with black arrows. The reduction in the number of germline nuclei by this RNAi is varied in different animals, but the example shown is typical.

The cdc-25.1(ij48) proliferative defect is probably specific to E lineage cells

By RNAi, we demonstrate that reduction of wild-type cdc-25.1 can reduce the number of intestinal and ectodermal cells born during embryogenesis, and reduce germline proliferation during post-embryonic development; it is probable other cell types are also affected. The excessive proliferation associated with the cdc-25.1(ij48) allele in intestinal cells is not seen in all cell types where the gene function is required; cdc-25.1(ij48) mutants do not display excessive germline proliferation, germline cells exit proliferative mitosis appropriately and proceed through meiosis (Figure 3B), indicating that they are responsive to the anti-proliferative functions of the gld genes (Francis et al., 1995; Kadyk and Kimble, 1998). The pharynx and hypodermis of cdc-25.1(ij48) animals appear normal in embryogenesis, as indicated by the pattern of MH27 antibody staining (not shown), and the number of seam cells born is unaffected. Seam cells were observed using the GFP marker wIs51 from C.elegans strain JR667 that causes GFP to be expressed specifically in seam cells (a gift from Joel Rothman). As a control, the lineage of the blastomere D, which produces muscle, was determined in mutant embryos and found to be as wild type. Mutants are similar in size to wild type and movement is not affected. We are therefore unable to detect evidence of hyperplasia in any cell type other than intestine; however, we cannot exclude some minor differences.

The cdc-25.1(ij48) phenotype is not explained by the distribution of CDC-25.1 protein

Ashcroft et al. (1999) showed the CDC-25.1 protein to be present in the developing germline, oocytes and in all embryonic blastomeres. In the early embryo, the protein is detected in non-dividing nuclei and in a cell membrane-associated location; it is not present in dividing nuclei. Our immunolocalization data are consistent with those published with the exception that we detect the protein in most or all nuclei later in embryonic development than previously reported (Figure 4E–J). However, its abundance clearly declines as the number of embryonic cells increases, consistent with its provision as a maternal product. The detectable presence of the protein in the embryo is consistent with the timing of the generation of extra intestinal cells in the mutant, and the abundance of the protein in the developing germline is consistent with its essential role in germline proliferation. However, we detect no striking difference in the pattern or intensity of immunofluorescent detection of the CDC-25.1 protein in cells of the E lineage that could readily explain the tissue-specific nature of the cdc-25.1(ij48) phenotype (Figure 4). There is also no noticeable difference in the immunofluorescent localization of the CDC-25.1 protein in the ij48 mutant and wild type (Figure 4).

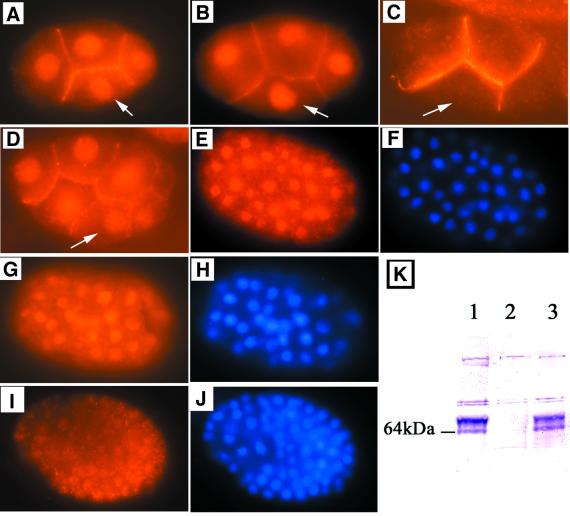

Fig. 4. Detection of the CDC-25.1 protein. Immunofluorescent detection of CDC-25.1 is shown in C.elegans embryos with anti-CDC-25.1 antibody: (A–E), (G) and (I). The embryos in (E), (G) and (I) were co-stained with DAPI to detect all nuclei, shown in (F), (H) and (J), respectively. (A) Wild type and (B) cdc-25.1(ij48), both at the 4-cell stage; the embryonic blastomere EMS is marked with a white arrow (this cell is the parent of the E and MS blastomeres). CDC-25.1 is detected in the nuclei of all four blastomeres at this stage in wild type and ij48. Staining of the boundaries of the cells is also seen. Both patterns of staining are competed by peptide B. (C) A 4-cell stage embryo produced with cdc-25.1 RNAi of the mother, by bacterial feeding of adults. The blastomere EMS is indicated with the white arrow. Nuclear staining of CDC-25.1 is lost, but cell boundary staining is retained. We see this pattern in many embryos produced shortly after mothers are transferred to bacterial cdc-25.1 RNAi lawns. As the cell boundary staining was also detected by Ashcroft et al. (1999) using an anti-CDC-25.1 antibody produced to a peptide sequence entirely different from that used here, it is almost certainly real. We conclude that the nuclear-localized CDC-25.1 is probably turned over more rapidly than that localized near the cell membrane in the early embryo. Both nuclear and cell boundary staining in the early embryo is lost after prolonged RNAi of mothers. (D) A wild type 7- or 8-cell embryo; the white arrow indicates the E blastomere and the cell to its immediate left is its sister MS. There is no obvious difference in the partitioning of CDC-25.1 from the EMS blastomere to its two daughters, MS and E. (E–H) Approximately 40- to 50-cell stage embryos, (E) and (F) are wild type, (G) and (H) are cdc-25.1(ij48). The CDC-25.1 protein is detected in most or all nuclei of both, as seen by comparing anti-CDC-25.1 staining in (E) and (G) with the DAPI co-stained images (F and H). (I) A wild-type embryo at about the 100-cell stage; some weak staining for CDC-25.1 is still present in most nuclei. (J) The DAPI co-stained image. A similar pattern is detected for cdc-25.1(ij48) (data not shown). (K) A western blot of total C.elegans protein from cultures enriched for adults, stained with the CDC-25.1 antibody used for immunofluorescence. Lane 1, a wild-type protein extract; lane 2, wild type treated predominantly as adults for 36 h by cdc-25.1 RNAi by bacterial feeding; lane 3, cdc-25.1(ij48).

We detect two major protein species with our anti-CDC-25.1 antibody by western blot (Figure 4K). As both species are depleted by cdc-25.1 RNAi (Figure 4K) and the detection of both is blocked efficiently by the peptide to which the antibodies were raised (data not shown), we believe both molecular weight species are the product of the cdc-25.1 gene. Both species are present in wild-type and in the cdc-25.1(ij48) mutant (Figure 4K). There is a slight difference in the relative intensity of the two species between wild type and mutant; however, the significance, if any, is unclear. Clearly, the mutation does not abolish one of the two species. In other systems, CDC25 proteins are subject to extensive regulatory phosphorylation (Patra et al., 1999), a possible explanation of the two molecular weight species detected here. The fact that the CDC-25.1 protein is almost undetectable by western blot on samples prepared from animals treated with cdc-25.1 RNAi indicates that the interference is effective.

The site of the cdc-25.1(ij48) lesion identifies a conserved motif

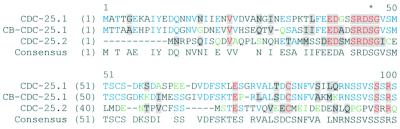

We compared the predicted amino acid sequence of CDC-25.1 with other nematode CDC-25 family members. CDC-25.1 from C.elegans shares 63% overall protein sequence identity with CB-CDC-25.1, its orthologue in the related nematode Caenorhabditis briggsae. It shares 23% identity with its C.elegans paralogue CDC-25.2, and considerably less with the two other C.elegans CDC-25 family members, CDC-25.3 and CDC-25.4 (Ashcroft et al., 1998). CDC-25.1 and CDC25.2 of C.elegans and CB-CDC25.1 of C.briggsae share the motif SRDSG in their N-terminal regions, the second serine being affected by the cdc-25.1(ij48) mutation (Figure 5). This motif is not present in the other two C.elegans family members. It seems probable that this short conserved sequence identifies a site of interaction with other proteins, and the tissue-specific nature of the cdc-25.1(ij48) hyperplasia may indicate that the site is critical for appropriate regulation in intestinal cells.

Fig. 5. Sequence comparison of the N-terminal regions of CDC25.1 and CDC25.2 of C.elegans and CDC25.1 of C.briggsae, performed using AlignX, a component of Vector NTI suite 6.0. Residues shared between two of the three proteins are indicated in blue, those shared between all three are boxed in grey. Ser46 of CDC-25.1, which would be substituted to phenylalanine by the ij48 lesion, is marked with an asterisk.

Discussion

cdc25 was first identified as a gene essential for progression through the cell cycle in Schizosaccharomyces pombe where its encoded phosphatase functions by activating CDC2 (Russell and Nurse, 1986). Both S.pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisae have a single cdc25 gene. Multiple cdc25 homologues have been found in a variety of multicellular eukaryotes, examples include STRING and TWINE of Drosophila melanogaster, STRING being required for mitosis (Edgar and O’Farrell, 1990) and TWINE specific for meiosis (Courtot et al., 1992). In mammals, three genes encoding family members have been identified and their encoded phosphatases probably act at distinct cell cycle checkpoints (Draetta and Eckstein, 1997).

In C.elegans, cdc-25.1 is one of four cdc25 homologues (Ashcroft et al., 1998). We show that the gain-of-function allele cdc-25.1(ij48) causes excessive proliferation of intestinal cells and its reduction by RNAi causes a failure of proliferation of a variety of cell types including intestinal cells. This opposite effect associated with loss and gain demonstrates that cdc-25.1 plays a critical role in the correct control of cell proliferation during C.elegans development. The phenotype of hyperplasia associated with a hypermorphic gain-of-function allele in cdc-25.1 is consistent with the known function of the CDC25 phosphatase family members as positive regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle (Russell and Nurse, 1986; Kumagai and Dunphy, 1991; Draetta and Eckstein, 1997). The human cdc25A and cdc25B genes have been shown to be capable of co-operating with activated RAS to cause oncogenesis (Galaktionov et al., 1995), and their overexpression has been found in some tumours (Hernandez et al., 1998). The hyperplasia caused by the cdc-25.1(ij48) lesion is not dependent on mutation of any other genes, as indicated by the ability of the mutant transgene to produce the intestinal hyperplasia efficiently when transformed into a wild-type strain of C.elegans. This demonstrates the direct oncogenic potential of this CDC25 family member in C.elegans. The suppression of the hyperplasia in a cdc-25.1(ij48) homozygote by partial cdc-25.1 RNAi demonstrates modulation of the oncogenic properties of this allele by administered RNAi.

That the extra cell divisions resulting in hyperplasia are restricted temporally to embryonic development is consistent with the demonstrated temporal abundance of the protein, being present during early embryogenesis but rapidly depleting during subsequent embryonic cell divisions. As discussed above, the protein is also abundant in the developing germline and continues to be abundant as germline nuclei mature into oocytes and proceed through fertilization. The cdc-25.1(ij48) allele shows a strict maternal pattern of inheritance consistent with its maternal supply to the developing oocyte and zygote. It is therefore probable that all of the CDC-25.1 protein present in the embryo is maternally supplied either as protein or as mRNA. There is no evidence for zygotic expression of the gene in the embryo. Thus the timing of extra cell divisions resulting in hyperplasia in the mutant is consistent with the temporal presence of the protein in the embryo.

The tissue-specific nature of the cdc-25.1(ij48) hyperplasia cannot be explained by the spatial localization of the protein in the early embryo. It is present in all early blastomeres and the ij48 lesion does not alter this localization. However, there is evidence that indicates that the cell cycle in C.elegans is differentially regulated in cells derived from different embryonic founder cells or blastomeres. A set of asymmetric cell divisions during early embryogenesis generates the five somatic founder cells from the zygote, AB, MS, E, C and D plus the germline founder P4. These blastomeres then undergo sets of cell divisions to produce the various tissues of the organism. The periodicity of the cell division cycles is distinct for the cell lineages derived from each somatic founder cell (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Sulston et al., 1983; Schnabel et al., 1997). Thus cell divisions between lineages derived from different blastomeres are asynchronous from the earliest stages of embryogenesis. Clearly, there must be a molecular basis to this distinct temporal regulation of the cell cycle in the cells derived from different blastomeres such that the central regulators of the cell cycle function at different periodicities. This aspect of cell cycle control is clearly defective in the cells derived from the E blastomere in cdc-25.1(ij48) mutants. When the E cell lineage is compared between the wild-type and cdc-25.1(ij48) mutant (Figure 2), it is evident that the cell cycle periodicity is shortened in the mutant. This shortening of the cell cycle periodicity is specific to the E lineage. Thus it is probable that the ij48 lesion identifies a site on CDC-25.1 necessary for the E-specific control of the cell cycle in C.elegans. The lesion would cause a serine to phenylalanine substitution at residue 46 of the encoded CDC-25.1 protein, the second serine of the conserved motif SRDSG. Both serine phosphorylation and sequences present in the N-terminal region of the CDC25 proteins of other organisms have been shown to be critical for CDC25 regulation and interaction with other proteins (Kumagai and Dunphy, 1996, 1999; Kumagai et al., 1998; Patra et al., 1999). That the amino acid residue affected by the mutation occurs within a short motif that is perfectly conserved between CDC-25.1 and CDC-25.2 of C.elegans and with CDC-25.1 of the related nematode species C.briggsae is also consistent with this being a site of interaction with another protein or proteins.

As indicated by previous studies (Ashcroft et al., 1999) and by the RNAi experiments presented here, the function of CDC-25.1 is required in multiple cell types including those of the E lineage, but not specific to this lineage. We have shown that it is also required in the ectoderm and the germline and is probably also required in other cell types. The fact that cell types other than those of the E lineage in cdc-25.1(ij48) homozygotes are unaffected indicates that the mutant CDC-25.1(S46F) protein is performing its role in a manner similar to wild type in these other tissues, as far as we can determine. There is certainly no similar shortening of the cell cycle in cells derived from blastomeres other than E. We therefore suggest that the motif SRDSG, conserved between three nematode CDC25 family members and altered to SRDFG in the cdc-25.1(ij48) mutant, is a region necessary for the E lineage-specific regulation of CDC-25.1, most probably a site of negative regulation of the molecule. It is probable that E tissue-specific regulators interact with this region, an interaction that is disrupted by the lesion, and that other regions of CDC-25.1 will be necessary for its correct regulation in other cell types. Thus the distinct periodicities of the cell cycle in cells derived from different C.elegans embryonic founder cells are achieved at least in part through tissue-specific regulation of a C.elegans CDC25. We are unable to detect by homology search conservation of the SRDSG motif in the sequence of any other CDC25s present in current databases. This sequence is within the non-catalytic N-terminal end of the protein, a region that is divergent between CDC25s of different organisms.

The wild-type somatic cell lineage of C.elegans is largely invariant (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Sulston et al., 1983). We show that the cdc-25.1(ij48) mutation causes the E cell lineage to develop in a pattern that is highly variable between different animals. We have counted between 30 and 45 intestinal cells being produced during embryogenesis in the mutant. The complex pattern of MH27 antibody staining in the intestine of the mutant by comparison with wild-type indicates many additional cell boundaries and thus that many of these extra cells are incorporated into the intestine. The process of morphogenesis of the C.elegans intestine has been well described previously (Leung et al., 1999). We have not determined how similar the actual process of morphogenesis of the intestine in cdc-25.1(ij48) mutants is to wild type; however, the healthy nature of these animals indicates that such intestines are functional. This is significant with respect to tissue morphogenesis in C.elegans. Although the morphogenesis process has evolved in the nematode to assemble tissues and organs from an effectively invariant cell lineage, and hence invariant number of cells, we show that it has the flexibility to deal successfully with many extra cells, at least as far as morphogenesis of the intestine is concerned.

Materials and methods

Strains

Caenorhabditis elegans culture was at 20°C, using standard methods (Lewis and Fleming, 1995). Some strains were obtained from the C.elegans Genetics Stock Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. The following strains were used: N2 Bristol wild type; CB61 dpy-5(e61); DR96 unc-76(e911); KR623 dpy-5(e61) let-602(h283) unc-13(e450);sDp2(I; f); KR727 dpy-5(e61) let-607(h402) unc-13(e450);sDp2(I; f); KR637 dpy-5(e61) let-604(h293) unc-13(e450);sDp2(I; f); KR1233 hDf8/dpy-5(e61) unc-13(e450); JR667 unc-119(e2498); wIs51; JR1838 wIs84 (a gift from J.Rothmann); IA109 ijIs10, IA123 cdc-25.1(ij48);ijIs10; IA268 cdc-25.1(ij48); and IA105 ijIs12.

Genetics

Standard genetic methods were used (Sulston and Hodgkin, 1988). The ij48 allele was isolated from a screen of 8000 chromosomes by ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis (Anderson, 1995) of the cpr-5::gfp integrated strain, IA109 ijIs10. ij48 was out-crossed three times and mapped to chromosome I at +1.1 by a combination of sequence-tagged sites (STS; Williams et al., 1992; Williams, 1995) and standard two- and multifactor genetic mapping (Sulston and Hodgkin, 1988). In several experiments, we failed to obtain recombination between ij48 and let-604. The deficiency hDf8 was found to cover ij48. The left-hand break point of hDf8 was mapped using a PCR-based approach. Sets of PCR primers (details can be obtained from the authors) were designed to amplify sequences from the genomic proximity of where we believed the approximate end point to be. PCR was performed on DNA prepared from hDf8 homozygotic dead embryos (homozygosity for this deficiency causes embryonic lethality) and from wild-type embryos as a control using standard methods (Williams, 1995). Thus sequences were tested for their presence or absence, and the left break point of hDf8 was mapped to cosmid sequence R10A10, between the predicted genes R10A10.1 and R10A10.2.

In experiments to test the allele ij48 with respect to dominance versus recessiveness and maternal versus zygotic behaviour, the genotypes of ij48/ij48 and ij48/+ mothers were distinguished by clonally plating their F1 progeny and observing the phenotypes of the F2 generation. The heterozygotes segregate 25% +/+ F1 progeny which produce 100% wild-type F2s, regardless of dominance or maternal affect considerations.

Transgenesis

For transgenic rescue of let-604, all cosmids were injected at 5 ng/µl using standard protocols (Mello and Fire, 1995). The C.elegans strain KR637 was used. Cosmids were gifts from the Sanger Centre.

Transgenesis with cdc-25.1 was with a linear 6.6 kb genomic DNA fragment containing the gene and flanking sequences, amplified by PCR from wild-type or ij48 mutant genomic DNA. To permit transgenic expression of a maternal gene, transgenesis by complex arrays was used (Kelly et al., 1997). Linear PCR-amplified cdc-25.1 DNA fragment was microinjected at concentrations between 2 and 10 ng/µl, and linearized total wild-type genomic C.elegans DNA was used as carrier at 100 ng/µl. To facilitate counting of intestinal cells, linearized elt-2::GFP plasmid pJM67 (Fukushige et al., 1998) was included in the DNA mix at 0.2 ng/µl.

RNAi

For suppression of the ij48 mutant phenotype, RNAi of candidate genes was performed by dsRNA injection of mothers (Fire et al., 1998). Details of oligos and genes can be obtained from the authors. Post-embryonic RNAi of cdc-25.1 and partial RNAi of embryos were performed by the bacterial feeding method (Fraser et al., 2000; Timmons et al., 2001).

CDC-25.1 antibodies

The two peptide sequences peptide A (CRYNGLNNPRDDPFG) and peptide B (NILYGLDDERRPKWV), coupled to keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH), were used to generate rabbit antibodies reactive to CDC-25. Antibodies were purified by immunoaffinity. Peptide B competed all immunoreactivity seen by immunofluorescence and the two major species detected by western blot (Figure 4K).

Microscopy

Immunofluorescence and general microscopy were by standard methods (Sulston and Hodgkin, 1988; Miller and Shakes, 1995). Four-dimensional microscopy for cell lineage analysis was as described previously (Schnabel et al., 1997).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank J.D.Barry for critical reading of the manuscript. The work was funded by an MRC Co-operative group component grant to I.L.J., and I.L.J. is an MRC Senior Fellow in Biomedical Sciences. I.L.J. and R.S. receive funding from a European Union TMR Research Network ERBFMRXCT980217; this funded the cell lineage analysis.

References

- Anderson P. (1995) Mutagenesis. In Epstein,H.F. and Shakes,D.C. (eds), Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 31–58.

- Ashcroft N.R., Kosinski,M.E., Wickramasinghe,D., Donovan,P.J. and Golden,A. (1998) The four cdc25 genes from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene, 214, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft N.R., Srayko,M., Kosinski,M.E., Mains,P.E. and Golden,A. (1999) RNA-mediated interference of a cdc25 homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans results in defects in the embryonic cortical membrane, meiosis and mitosis. Dev. Biol., 206, 15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B., Eaton,B.A. and Priess,J.R. (1992) skn-1, a maternally expressed gene required to specify the fate of ventral blastomeres in the early C.elegans embryo. Cell, 68, 1061–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton C., Mckerrow,J.H. and Johnstone,I.L. (1998) Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans gut cysteine protease gene cpr-1: requirement for GATA motifs. J. Mol. Biol., 283, 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtot C., Fankhauser,C., Simanis,V. and Lehner,C.F. (1992) The Drosophila cdc25 homolog twine is required for meiosis. Development, 116, 405–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draetta G. and Eckstein,J. (1997) Cdc25 protein phosphatases in cell proliferation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1332, M53–M63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar B.A. and O’Farrell,P.H. (1990) The 3 postblastoderm cell cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis are regulated in g2 by string. Cell, 62, 469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone C. and Russell,P. (1991) Fission yeast p107wee1 mitotic inhibitor is a tyrosine serine kinase. Nature, 349, 808–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu,S.Q., Montgomery,M.K., Kostas,S.A., Driver,S.E. and Mello,C.C. (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature, 391, 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis G.R. and Waterston,R.H. (1985) Muscle organization in Caenorhabditis elegans—localization of proteins implicated in thin filament attachment and i-band organization. J. Cell Biol., 101, 1532–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Barton,M.K., Kimble,J. and Schedl,T. (1995) gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics, 139, 579–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser A.G., Kamath,R.S., Zipperlen,P., Martinez-Campos,M., Sohrmann,M. and Ahringer,J. (2000) Functional genomic analysis of C.elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature, 408, 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushige T., Hawkins,M.G. and Mcghee,J.D. (1998) The GATA-factor elt-2 is essential for formation of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev. Biol., 198, 286–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K., Lee,A.K., Eckstein,J., Draetta,G., Meckler,J., Loda,M. and Beach,D. (1995) CDC25 phosphatases as potential human oncogenes. Science, 269, 1575–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard J.S., Barry,J.D. and Johnstone,I.L. (1997) cis regulatory requirements for hypodermal cell-specific expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle collagen gene dpy-7. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 2301–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B. (1992) Induction of gut in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Nature, 357, 255–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B. (1995) An analysis of the response to gut induction in the C.elegans embryo. Development, 121, 1227–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. (1997) Gut reaction to Wnt signaling in worms. Cell, 90, 581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock E.M. and White,J.G. (1985) Polyploid tissues in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol., 107, 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S. et al. (1998) cdc25 cell cycle-activating phosphatases and c-myc expression in human non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Cancer Res., 58, 1762–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessus C. and Beach,D. (1992) Oscillation of MPF is accompanied by periodic association between Cdc25 and Cdc2-cyclin-b. Cell, 68, 323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyk L.C. and Kimble,J. (1998) Genetic regulation of entry into meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development, 125, 1803–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W.G., Xu,S.Q., Montgomery,M.K. and Fire,A. (1997) Distinct requirements for somatic and germline expression of a generally expressed Caernorhabditis elegans gene. Genetics, 146, 227–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A. and Dunphy,W.G. (1991) The CDC25 protein controls tyrosine dephosphorylation of the CDC2 protein in a cell-free system. Cell, 64, 903–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A. and Dunphy,W.G. (1996) Purification and molecular cloning of Plx1, a Cdc25-regulatory kinase from Xenopus egg extracts. Science, 273, 1377–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A. and Dunphy,W.G. (1999) Binding of 14-3-3 proteins and nuclear export control the intracellular localization of the mitotic inducer Cdc25. Genes Dev., 13, 1067–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A., Yakowec,P.S. and Dunphy,W.G. (1998) 14-3-3 proteins act as negative regulators of the inducer Cdc25 in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larminie C.G.C. and Johnstone,I.L. (1996) Isolation and characterization of four developmentally regulated cathepsin B-like cysteine protease genes from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Cell Biol., 15, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung B., Hermann,G.J. and Priess,J.R. (1999) Organogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev. Biol., 216, 114–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.A. and Fleming,J.T. (1995) Basic culture methods. In Epstein,H.F. and Shakes,D.C. (eds), Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 3–29.

- Lin R.L., Thompson,S. and Priess,J.R. (1995) pop-1 encodes an hmg box protein required for the specification of a mesoderm precursor in early C.elegans embryos. Cell, 83, 599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C. and Fire,A. (1995) DNA transformation. In Epstein,H.F. and Shakes,D.C. (eds), Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 451–482.

- Miller D.M. and Shakes,D.C. (1995) Immunofluorescence microscopy. In Epstein,H.F. and Shakes,D.C. (eds), Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 365–394.

- Morgan D.O. (1995) Principles of cdk regulation. Nature, 374, 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra D., Wang,S.X., Kumagai,A. and Dunphy,W.G. (1999) The Xenopus Suc1/Cks protein promotes the phosphorylation of G2/M regulators. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 36839–36842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle D.L. (1988) The dauer larva. In Wood,W.B. (ed.), The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 393–412.

- Rocheleau C.E., Downs,W.D., Lin,R.L., Wittmann,C., Bei,Y.X., Cha,Y.H., Ali,M., Priess,J.R. and Mello,C.C. (1997) Wnt signaling and an APC-related gene specify endoderm in early C.elegans embryos. Cell, 90, 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell P. and Nurse,P. (1986) CDC25+ functions as an inducer in the mitotic control of fission yeast. Cell, 45, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell P. and Nurse,P. (1987) Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein-kinase homolog. Cell, 49, 559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel R., Hutter,H., Moerman,D. and Schnabel,H. (1997) Assessing normal embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans using a 4D microscope: variability of development and regional specification. Dev. Biol., 184, 234–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J. and Horvitz,H.R. (1977) Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol., 56, 110–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J. and Hodgkin,J. (1988) Methods. In Wood,W.B. (ed.), The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 587–606.

- Sulston J.E., Schierenberg,E., White,J.G. and Thomson,J.N. (1983) The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol., 100, 64–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe C.J., Schlesinger,A. and Bowerman,B. (2000) Wnt signalling in Caenorhabditis elegans: regulating repressors and polarizing the cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol., 10, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L. and Fire,A. (1998) Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature, 395, 854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L., Court,D. and Fire,A. (2001) Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene, 263, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B.D. (1995) Genetic mapping with polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. In Epstein,H.F. and Shakes,D.C. (eds), Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 81–96.

- Williams B.D., Schrank,B., Huynh,C., Shownkeen,R. and Waterston,R.H. (1992) A genetic-mapping system in Caenorhabditis elegans based on polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. Genetics, 131, 609–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.W., Hill,R.J., Heid,P.J., Fukuyama,M., Sugimoto,A., Priess,J.R. and Rothman,J.H. (1997) end-1 encodes an apparent GATA factor that specifies the endoderm precursor in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Genes Dev., 11, 2883–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]