Abstract

BACKGROUND

Reproductive-age women with intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) following uterine surgery may be asymptomatic or may experience light or absent menstruation, infertility, preterm delivery, and/or peripartum hemorrhage. Understanding procedure- and technique-specific risks and the available evidence on the impact of surgical adjuvants is essential to the design of future research.

OBJECTIVE AND RATIONALE

While many systematic reviews have been published, most deal with singular aspects of the problem. Consequently, a broadly scoped systematic review and selective meta-analyses identifying evidence strengths and gaps are necessary to inform future research and treatment strategies.

SEARCH METHODS

A systematic literature review was performed seeking evidence on IUA incidence following selected uterine procedures and the effectiveness of hysteroscopic adhesiolysis on menstrual, endometrial, fertility, and pregnancy-related outcomes. An evaluation of the impact of surgical adjuvants designed to facilitate adhesion-free endometrial repair was included. Searches were conducted in the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases following PRISMA guidelines and included English-language publications from inception to 8 November 2024. Inclusion criteria restricted articles to those reporting IUA epidemiology or related clinical outcomes. Risk of bias assessment used the US NIH tools for interventional and observational studies. Meta-analyses were conducted and reported only for outcomes where there were sufficient data. Per analysis, we report on proportions (with 95% CI), heterogeneity (I2), and the risk of bias for each study included.

OUTCOMES

The review identified 249 appropriate publications. The risks of new-onset IUAs following the removal of products of conception after early pregnancy loss, hysteroscopic myomectomy, and hysteroscopic metroplasty for septum correction were 17% (95% CI: 11–25%; 13 studies, I2 = 87%, poor to good evidence quality), 16% (95% CI: 6–28%; 8 studies, I2 = 93%, fair to good evidence quality), and 28% (95% CI: 13–46%; 8 studies, I2 = 91%, fair to good evidence quality), respectively. For primary IUA prevention with adjuvant intrauterine gel barriers, the relative risks were 0.45 (95% CI: 0.30–0.68; three studies, I2 = 0%, poor to good evidence quality), 0.38 (95% CI: 0.20–0.73; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair evidence quality), and 0.29 (95% CI: 0.12–0.69; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality), respectively, following the above potentially adhesiogenic procedures. Following adhesiolysis without adjuvants, the IUA recurrence rate was 35% (95% CI: 24–46%; 13 studies, I2 = 95%, poor to good evidence quality), similar to the rate of 43% for both those treated adjuvantly with an intrauterine balloon (95% CI: 35–51%; 14 studies, I2 = 85%, poor to good evidence quality), or an IUD (95% CI: 27–59%; four studies, I2 = 85%, fair to good evidence quality). The recurrence rate for secondary prevention with gel barriers was 28% (95% CI: 4–62%; three studies, I2 = 94%, good evidence quality). Notably, there was an excess rate of associated adverse obstetrical outcomes, including preterm delivery, placenta accreta spectrum, placenta previa, peripartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy, with evidence demonstrating the beneficial impact of adjuvant therapies on these outcomes.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS

This systematic review comprehensively analyzes IUA formation following uterine surgical procedures and adjuvant therapy effectiveness. Even following adhesiolysis, it is apparent that the basilar endometrial trauma thought to facilitate the formation of IUAs may persist and contribute to adverse reproductive outcomes. Many critical gaps remain in our knowledge of the pathogenesis, prevention, and management of endometrial trauma and IUAs.

PREGISTRATION NUMBER

PROSPERO (ID: CRD42023366218).

Keywords: intrauterine adhesions, endometrial trauma, hysteroscopy, placenta accreta spectrum, myomectomy, metroplasty, septum removal, retained products of conception, postpartum hemorrhage, infertility

Graphical abstract

Systematic review and selected meta-analyses of intrauterine adhesions related to endometrial trauma. IUA, intrauterine adhesions.

Introduction

Intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) are a manifestation of damage to the basilar layer of the endometrium that results in variable degrees of endometrial fibrosis. The adhesions present as bands of fibrous scar tissue that bind the surfaces of the uterine cavity, which comprises the endometrial cavity and cervical canal. In severe cases, the endometrial cavity can be completely obliterated with no underlying functional endometrium. The disorder was first described by Heinrich Fritsch in 1894 (Fritsch, 1894), then by Bass in 1927 (Bass, 1927), and Stamer in 1946 (Stamer, 1946), before Joseph Asherman published the two papers, in 1948 and 1950, which led to the eponymous syndrome known today (Asherman, 1948, 1950). Indeed, Asherman’s disease is now considered synonymous with IUAs, while the term Asherman’s syndrome should be used when IUAs are found in association with symptoms that may include infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, and light menstrual bleeding or amenorrhea (Yu et al., 2008b).

While typically caused by transcervical surgical procedures that injure the basilar endometrial layer, such as dilation and curettage (D&C), IUAs may also occur secondary to other uterine interventions such as abdominal myomectomy performed either laparoscopically or via laparotomy (Capmas et al., 2018; Bortoletto et al., 2022; Lagana et al., 2022), image-guided procedures for leiomyomas and adenomyosis such as uterine artery embolization (Toguchi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a), or even intra-abdominal procedures performed at the time of Cesarean delivery designed to treat postpartum hemorrhage (Zouaghi et al., 2023). Genital tuberculosis is a common cause of severe endometrial trauma and IUAs in endemic areas, specifically Africa and Asia, where it is estimated to comprise 20% of the etiologies of infertility cases (Sharma et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2021). In the developed world, including the USA and Europe, it is more common in immigrants from endemic areas but overall appears to be involved in <1% of women with infertility (Langer et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021).

Whereas minimal endometrial trauma and mild IUAs can be asymptomatic, more extensive trauma and associated severe IUAs are a known cause of light or absent menstruation (amenorrhea), in addition to other manifestations such as infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, and inability to access the endometrial cavity for diagnostic testing (Salazar et al., 2017). Even when IUAs are treated surgically, recurrence is common, and regardless, the underlying trauma to the endometrial basalis may not be corrected, and the functional endometrium may not be fully restored. When pregnancy occurs following treatment of IUAs, there is evidence of adverse obstetrical outcomes, including preterm delivery and postpartum hemorrhage (Deans et al. 2018; Hui et al., 2018; Hooker et al., 2020). A consequence of endometrial trauma may be impaired placental circulation, increasing the risk of growth restriction and preterm labor (Hooker et al., 2022). The absence of an intact decidualized endometrial basalis can lead to abnormal placental attachment to, or invasion of, the myometrium, a circumstance known as placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorder, and is associated with increased risks of peripartum hemorrhage and requires additional interventions, including blood transfusion, uterine artery occlusion, and hysterectomy (Deans et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Tavcar et al., 2023). These circumstances may result in substantial maternal and neonatal morbidity and related increased utilization of health care resources.

The initial approach to primary prevention of IUAs is the avoidance of endometrial infection and potentially traumatic intrauterine surgical procedures. However, in many cases, such procedures are necessary for optimal care. Consequently, it could be hypothesized that adopting surgical techniques designed and executed in fashions that minimize basilar endometrial trauma should reduce the risk of associated adhesions. In addition, following a potentially traumatic and adhesiogenic procedure, utilizing systemic and/or locally applied adjuvant therapies, including systemic pharmaceuticals, intrauterine barriers, and active intrauterine agents such as ‘biologics’, may facilitate optimal basilar endometrial repair without adhesion formation.

For women diagnosed with IUAs, hysteroscopically directed adhesiolysis is considered the treatment of choice. The measures taken to optimize basilar endometrial repair, thereby reducing the risk of reformation of IUAs, can collectively be called secondary prevention and, in addition to minimally traumatic dissection, include the adjuvant therapies already described as potentially applicable for primary prevention.

This systematic review and, where feasible, meta-analyses, synthesize the body of evidence examining the incidence of IUAs following potentially adhesiogenic uterine surgical procedures and the impact of the various techniques and adjuvants used for the primary and secondary prevention of IUAs. We also analyzed secondary surgical outcomes, such as the thickness of the endometrial echo complex (EEC), often referred to as endometrial thickness (EMT), and the impact on menstrual function as well as pregnancy outcomes, including adverse obstetrical and neonatal outcomes, such as preterm delivery, placenta previa, peripartum hemorrhage, and the related PAS disorder. Our scope did not include IUAs related to image-guided procedures, intraoperative procedures related to the treatment of peripartum hemorrhage at Cesarean section, or to infectious disease, in particular, tuberculosis. A glossary of the definitions and terms used in this review is found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Glossary of terms.

| Abdominal myomectomy | Removal of leiomyomas, usually from the uterus, performed abdominally either via laparotomy or under laparoscopic direction. Laparoscopic myomectomy may be performed with or without the use of an assistive device (e.g. the da Vinci® system). |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) | Non-gestational vaginal bleeding of uterine origin in the reproductive years that is abnormal in frequency, regularity, duration, and/or volume that includes bleeding between periods and unscheduled bleeding associated with the use of medications or intrauterine contraceptive devices. |

| Bipolar RF instrument | A radiofrequency (RF) electrosurgical instrument that contains both electrodes. During hysteroscopic surgery, this design allows function in electrolyte-containing distention media. |

| Cervical canal | The anatomical passage through the cervix, lined with columnar epithelium, connecting the vagina to the endometrial cavity. |

| Cervix | See Uterine Cervix. |

| Dilation and curettage (D&C) | A procedure involving serial expansion of the cervical canal using a set of dilators (dilation) followed by inserting a serrated instrument for blind mechanical removal of the endometrium, intracavitary lesions, and/or products of conception. Alternatively can also be performed using suction curettage for evacuation of uterine contents. |

| Electromechanical tissue removal instrument | A usually proprietary cylindrical hollow hysteroscopic instrument with a distal side fenestration surrounding an oscillating cylinder with an aligned fenestration that acts as a blade. When activated, tissue is drawn through the fenestration with suction where it is transected (morcellated) by the blade. The morcellated tissue is generally aspirated by suction to a remotely-located tissue trap. |

| Endometrial cavity | The potential space within the uterine corpus, lined with endometrium, is connected at the lateral cornua to each fallopian tube and caudally to the cervical canal. It comprises the largest component of the ‘uterine cavity’. |

| Endometrial echo complex (EEC) | The endometrium and its contents, if any, as seen typically on the sagittal view with transvaginal ultrasound and sometimes referred to as the ‘endometrial stripe’. It is measured from the endomyometrial interface anteriorly to the same interface posteriorly and includes any content visualized within the cavity between the endometrial layers. |

| Endometrial thickness (EMT) | The double layer of endometrium visualized sonographically as the EEC but absent any endometrial cavity content. It is generally used as a metric in infertility care and investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding. |

| Endometrial trauma | Damage to the endometrium, typically from surgical procedures. When this trauma damages the basilar layer of endometrium, it can result in the formation of intrauterine adhesions. Such trauma and enduring damage can also occur secondary to a chronic endometrial infection such as tuberculosis. |

| Endometrium | The layer of glands and stroma that lines the endometrial cavity. Receives and supports the early development of a pregnancy and, absent pregnancy, the superficial component (functionalis) partially sloughs during the process of menstruation. |

| Hysteroscopy/hysteroscopic | An endoscopic technique used to visually direct the performance of intrauterine diagnostic or operative procedures with instruments passed through the cervical canal. |

| IVF-ET | In vitro fertilization (IVF) and embryo transfer (ET). IVF refers to fertilization of an egg with sperm in a laboratory setting, while ET is the placement of a resulting embryo into the endometrial cavity via a catheter inserted through the cervical canal. |

| Intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) | Fibrous tissue abnormally attaching opposing sides of the endometrial cavity and/or cervical canal secondary to abnormal healing typically following basilar endometrial trauma. |

| Laparoscopy/laparoscopic | An abdominal endoscopic (telescopic) technique used to visually direct the performance of intraperitoneal diagnostic or operative procedures with instruments passed through small, ancillary ports. |

| Laparotomy/laparotomic | An intraperitoneal procedure performed through an abdominal incision large enough for the passage of the hand and/or standard surgical instruments. |

| Hysteroscopic metroplasty | Surgical (usually hysteroscopic) correction of congenital anomalies (Müllerian) of the uterus, most commonly of a septum, but may include remodeling for ‘T-shaped’, ‘Y-shaped’, or other dysmorphic congenital anomalies. |

| Monopolar RF instrument | A radiofrequency (RF) electrosurgical instrument that contains only one small diameter electrode designed to create the surgical tissue effect; the second is a large area electrode positioned remotely, typically on the thigh, designed to disperse the current preventing damage to the skin. During hysteroscopy, this design requires electrolyte-free distention media to function. |

| Myomectomy | Removal of a leiomyoma, almost invariably from the uterus. Myomectomy may be performed hysteroscopically (hysteroscopic myomectomy), vaginally (vaginal myomectomy), or abdominally (abdominal myomectomy via either laparotomy (laparotomic myomectomy) or under laparoscopic direction (laparoscopic myomectomy). Laparoscopic myomectomy may be performed with or without the use of an assistive device (e.g. the da Vinci® system). |

| Opposing leiomyomas | Submucous leiomyomas (e.g. FIGO Type 0, 1, or 2) situated adjacent to each other on opposite sides of the endometrial cavity. |

| Primary prevention (of IUAs) | Adjunctive surgical techniques, devices, medications, or other prophylactic interventions designed to facilitate endometrial repair following surgically induced endometrial trauma, thereby reducing or eliminating the risk of IUA formation. Primary prevention can also be considered to encompass avoidance of such procedures using expectant, medical or surgical management techniques. |

| Radiofrequency (RF) electrical energy | High frequency (300–500K Hz), alternating polarity electrical current used to create tissue effects (vaporization or coagulation) between two electrodes by rapid elevation of intracellular temperature. |

| Retained products of conception (RPOC) | Pregnancy tissue not completely expelled at the time of spontaneous miscarriage or delivery, or remaining in the endometrial cavity following attempted medical or surgical removal. |

| Second look hysteroscopy (SLH) | Refers to a repeat diagnostic hysteroscopic evaluation typically performed 4–12 weeks after a surgical procedure that may adversely impact the endometrium. The procedure is used to assess for the presence of IUAs or, following adhesiolysis, recurrent intrauterine adhesions. If found, adhesiolysis is typically performed during the same procedure. |

| Secondary prevention (of IUAs) | Adjunctive surgical techniques, devices, or other therapeutic and prophylactic interventions designed to be used in association with intrauterine adhesiolysis, thereby reducing or eliminating the risk of recurrent formation of IUAs. |

| Sonohysterography (SHG) | The performance of uterine ultrasound while instilling and distending the endometrial cavity with sonolucent contrast, usually gel or normal saline (also commonly referred to as gel infusion sonography ‘GIS’ or saline infusion sonography ‘SIS’). This imaging technique enhances the visualization of intracavitary lesions such as polyps, leiomyomas, and adhesions. |

| Uterus | The normally pear-shaped, muscular reproductive organ in the female pelvis comprising a corpus (body) and the cervix. It supports a pregnancy until maturity when its muscular function results in expulsion of the fetus through a fully dilated cervical canal. |

| Uterine cavity | The lumen within the uterus comprising the endometrial cavity and the contiguous cervical canal. |

| Uterine cervix | The fibromuscular cylindrical portion of the uterus connecting the uterine corpus to the vagina that contains the cervical canal. |

| Uterine corpus | The muscular ‘body’ of the uterus that is comprised of myometrium, surrounding serosa, and the roughly T or triangular-shaped endometrial cavity lined with endometrium. The uterine corpus attaches inferiorly to the uterine cervix and laterally, at the cornua, to the right and left fallopian tubes. |

Methods

Systematic review protocol and registration

This systematic literature review (SLR) was reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021) and conducted in alignment with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., 2011). The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews database (PROSPERO ID: CRD42023366218).

Search and study selection

An extensive systematic search of the English language literature regarding surgically induced IUAs was conducted using the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. The original search was run from inception to 16 December 2022, with no search filters applied for geographical location. A subsequent search of all three databases was performed on 8 November 2024, to capture subsequent candidate publications. Search strategies were developed using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and relevant keywords pertaining to the patient population, intervention, and the outcomes of interest. The search strategies, including all search terms, are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Additionally, the bibliographies of relevant SLRs identified in the search were hand-searched for potentially relevant publications.

Screening process

Studies identified in the database searches were reviewed by two independent reviewers at the title and abstract stage to be selected for full-text review. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, by a third independent reviewer and confirmed by the principal investigator (M.G.M.). Full-text review was also performed by both reviewers, with discrepancies generated and reconciled similarly by consensus, or if necessary, by the principal investigator. Studies identified through hand searches were immediately advanced to the full-text screening stage. The screening process was conducted based on predefined eligibility criteria for the study population, intervention, comparator, and study design (PICOS criteria).

The inclusion criteria, according to the PICOS framework, for the selection of studies were (i) published in English; (ii) population: pre-menopausal women of reproductive age; (iii) interventions: any intrauterine or abdominal surgical procedure that could affect the uterus, including the endometrial cavity, such as hysteroscopic or abdominal myomectomy by laparotomy or laparoscopy; in addition, all adjuvant treatments used in surgeries were considered eligible, as were all surgical tools; (iv) comparator: no specific comparator was required; (v) outcomes: IUA rates and severities, pregnancy-related outcomes, and menstrual outcomes; and (vi) study design: studies with sample sizes of <10 patients were excluded, as were narrative reviews, editorials, letters, opinion pieces, conference abstracts, and other systematic reviews.

The studies included following the full-text review were extracted by two independent reviewers into a Microsoft Excel-based (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington) Data Extraction Form (DEF). The DEF comprised five major sections: (i) study details (study title, author list, citations, and geographical region); (ii) methods (study design, study duration, and follow-up duration); (iii) procedural details (surgical procedures, index procedure, diagnostic procedures, techniques used, and adjuvant therapies utilized); (iv) patient demographics (population types, age, and total population); and (v) outcomes (primary and secondary outcomes and complications). Primary outcomes included the prevalence, incidence, and recurrence rate of IUAs and adhesion severity as diagnosed by direct visualization with hysteroscopy. Secondary obstetrical outcomes included rates of natural pregnancy, pregnancy following ART, live births, and miscarriages. Secondary gynecologic outcomes included EMT and menstrual function (graded as absent, light, regular, or heavy). Additional outcomes extracted were related to obstetrical complications, including preterm delivery, PAS disorders (comprising placenta accreta, increta, and percreta), as well as placenta previa and peripartum hemorrhage.

Selected authors extracted the data, emphasizing means, medians, ranges, and risk ratios (RRs) in the observed data. Outcomes reported at multiple time points were extracted at each point so that analysis and comparisons could be made afterward. This is commonly applied to endometrial outcomes (EMT and menstrual function) and adhesion scores pre- and post-adhesiolysis at the time of second-look hysteroscopy.

Study quality assessment

Assessment of study quality was conducted by three independent reviewers (D.S., J.K., and A.K.J.) supervised by M.G.M., using two quality assessment tools published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2021), the Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies Tool and the Quality Assessment of Observational Studies Tool, which were utilized to assess controlled intervention and observational studies, respectively. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved with discussion, and if a consensus was not reached, a third reviewer was consulted. In this assessment, the quality of each included study was rated as good, fair, or poor. Within each tool, the risk of bias (RoB) assessment was based on 14 items, with possible responses of ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Cannot Determine’, ‘Not Applicable’, ‘Not reported’, and ‘None of the above’. Records that received a ‘Yes’ for 11–14 items were categorized as ‘Good’, whereas those that scored 7–10 were deemed ‘Fair’, and finally, those that scored 1–6 were deemed ‘Poor’.

Evidence synthesis

Following data extraction, the available evidence within the literature was reviewed to determine which outcomes represented targets for meta-analysis or summary statistics as forms of evidence synthesis. Meta-analysis was preferably conducted on primary outcomes related to the risk of IUA formation, which was the focus of this review. The feasibility of meta-analysis of each outcome was determined according to the similarity among populations and study designs. For outcomes wherein comparisons were made, meta-analyses were limited to subsets of the included studies with head-to-head randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs. These included the efficacy of preventative adjuvants in reducing the incidence or recurrence of IUAs. For other outcomes, wherein no comparison was intended, or this comparison could not be informed using controlled trials due to gaps in the literature, observational studies were considered acceptable study designs for inclusion within a meta-analysis. Due to population and study design differences, meta-analysis results are presented without comparison between interventions. Finally, if results were not reported in enough detail or among publications not sufficiently similar in population or study design, these were summarized and presented descriptively herein.

Following the rationale mentioned above, comparative meta-analyses were conducted to analyze both the incidence and recurrence of IUAs in patients who did and did not receive preventative adjuvant treatments for primary and secondary IUA prophylaxis. These analyses were informed using the results of controlled interventional studies with similar populations and study designs. Other meta-analyses were conducted using a combination of observational and randomized control study results, including IUA-related outcomes and those related to pregnancy, menstrual function, and EMT.

Meta-analysis methodology

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.2.2 (Core, 2024). A single-arm meta-analysis was performed for effect measures calculated by counting the number of individuals who experienced an event. In these cases, results were reported by the included studies as proportions, representing the proportion of patients experiencing a given event. This method was applied to analyze the prevalence, incidence, and recurrence of IUAs. We used an inverse-variance method, a random effect model, to derive a pooled estimate for the outcomes. Using this methodology, each study was weighted based on the inverse of the variance of the effect estimate. Thus, studies with large sample sizes and smaller SEs were given more weight than those with small sizes and high SEs, enhancing the pooled estimate’s precision (Deeks et al., 2023).

To compare the effect of different interventions on outcomes, such as incidence and recurrence of IUAs, the proportion of patients experiencing an event (IUAs) in each arm (intervention type) was meta-analyzed comparatively to generate RRs. The pooled RR was calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel method, which derives the study weights using the number of events and non-events in the treatment and control groups (Harrer et al., 2021). This random effect model was preferred as it provides greater statistical precision compared with other available methods when binary events are analyzed (Deeks et al., 2023).

Finally, a standardized mean difference (SMD) was used as an effect measure for outcomes that evaluated continuous data. A SMD was used to combine the mean adhesion scores that were calculated using various scoring algorithms and EMT measurements. We used the Hedges’ g statistic for SMDs, as our analysis was conducted over a relatively small sample, and the studies had greater sample size variations in the experimental and the control arms (Harrer et al., 2021). The inverse variance approach was used to calculate the study weights in the pooled estimates. Given a high degree of heterogeneity among the included studies regarding the study design, effect measures, sizes, study population, and study interventions, a random effects model was used for the meta-analyses of all outcomes. Pooled outcomes from the analyses were reported along with their corresponding 95% CIs, with results presented as a forest plot. Additionally, the degree of heterogeneity was presented using I2 and τ2 statistics in each forest plot.

Literature summary through meta-analysis

Standardized exploration methodology

Standardized inclusion criteria were implemented for each outcome analyzed to ensure that studies were sufficiently homogenous and of sufficient quality for use in meta-analysis. These comprised a set of PICOS criteria for each meta-analysis and were based on study features, including population (generally the study patients’ disease or disorder), intervention (surgical technique or IUA-preventative adjuvant treatment), comparison made (if any), outcome reported and metrics used, and study design (RCTs or any design). Some criteria implemented stemmed from the understanding that RCTs represent the highest level of evidence for comparative effectiveness studies, allowing comparison of treatment outcomes amongst otherwise homogeneous groups of subjects. Therefore, meta-analyses of comparative effectiveness were limited to RCTs with direct head-to-head comparisons of the interventions of interest. The intended comparisons were between surgical techniques, tools, and adjuvant treatments designed to prevent or reduce the rate or severity of IUA formation. The rigorous nature of RCTs also provides consistency within treatment arms and standardized subject evaluations to yield more reliable conclusions. Where heterogeneity between studies was a concern, meta-analyses were limited to RCTs as a data set. These included the proportional meta-analyses of single arms of studies of IUA recurrence following adhesiolysis, which focused on surgical techniques or adjuvant treatments without comparisons.

The proposed study set for analysis was restricted to subjects who had undergone a diagnostic hysteroscopy capable of yielding an IUA diagnosis. This criterion was imposed to ensure all patients with IUAs could be identified, minimizing false negatives. Studies were excluded from analyses if IUAs were diagnosed using any method other than hysteroscopy. Studies were grouped according to the population studied, thereby facilitating meta-analysis. Pooled prevalence estimates were to be derived using a proportional meta-analysis by combining the findings from single-arm studies. We also sought to determine the prevalence of IUAs by severity, grouped categorically into ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, or ‘severe’ adhesions, and by reported mean/median adhesion scores (if provided).

Prevalence of IUAs

We sought to determine the background prevalence of IUAs among the general population and at-risk groups who had reportedly not undergone previous uterine surgeries.

Incidence and severity of IUAs following potentially adhesiogenic procedures and comparative efficacy of adjuvant therapies

The incidence of IUAs following potentially adhesiogenic uterine surgeries was estimated using single-arm proportional meta-analyses, which yielded a proportion of patients with IUAs following each procedure. These analyses were conducted separately for specific types of uterine procedures, including hysteroscopic metroplasty for septum correction, hysteroscopic myomectomy, and laparoscopic and laparotomic myomectomy. In addition, these analyses were performed for pregnancy-related procedures such as D&C for removal of products of conception (POC) following spontaneous pregnancy loss, as well as for removal of pregnancy tissue not completely expelled at the time of miscarriage or delivery or remaining in the endometrial cavity following attempted medical or surgical removal (known as retained products of conception; RPOC). Studies that evaluated patients with existing IUAs were excluded from these analyses.

Meta-analyses were further segregated according to subcategories of patients’ uterine conditions. Studies based on septum correction were also evaluated separately for those who experienced incomplete surgery, meaning less than total septal removal. Studies of patients with leiomyomas were initially subdivided according to the surgical approach to myomectomy, which could be either hysteroscopic or abdominal (laparoscopic or laparotomic). For meta-analyses, patients’ fibroid phenotypes were evaluated by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification (Munro et al., 2011; Munro et al., 2018), as well as other features such as leiomyoma size and number, and, when more than one, whether they were opposing or non-opposed within the endometrial cavity. Studies of patients who underwent myomectomy were further subdivided according to the technique used to perform the myomectomy, including whether radiofrequency (RF) electrosurgery with monopolar or bipolar instruments or electromechanical morcellation was utilized and whether cold-dissection techniques within the leiomyoma pseudocapsule were described. These subdivisions were applied due to the potential for these myomectomy techniques to result in different rates of IUA formation. Studies of patients who underwent D&C were subdivided according to the method used to perform the procedure and the time of pregnancy at which patients underwent surgery, categorized by pregnancy trimester.

Among these categories, meta-analyses of the incidence of IUAs were further subdivided according to study design, with analyses restricted to subsets of RCTs and non-RCTs and an unrestricted study design group. We permitted the ‘no adjuvant’ arms of the included studies to allow antibiotics and/or estrogens with or without progestins. The reasons for this decision were 2-fold. First, the available high-quality evidence suggests that these agents have no impact on measured adhesion outcomes (AAGL-ESGE, 2017; Yang et al., 2022b; Hanstede et al., 2023). Second, the frequency of antibiotic and estrogen preparations use was often the implied standard of care, and excluding studies that reported the use of these agents in each arm of a protocol would frequently preclude meta-analyses.

For each analysis described above, severity was also investigated using two methods for combination via meta-analysis. First, pooled incidence estimates were sought for each qualitative category of IUA severity, including mild, moderate, and severe, as described by the authors of each study. Second, mean and/or median IUA scores were sought in each standard IUA classification scale: March, European Society of Gynecological Endoscopy (ESGE), and American Fertility Society (AFS). To allow for meta-analyses of studies using different classification systems, the severities were re-categorized as mild, moderate, or severe following the protocol described by Hooker et al. (2014). While menstruation does not depend solely on IUA severity, given that AFS scores include menstrual outcomes, studies were investigated to determine whether menstrual outcomes were included in patients’ scores or omitted. Analyses were then conducted separately for studies that fit either category. Finally, we analyzed the relative effectiveness of various adjuvants for IUA prevention by evaluating changes in adhesion severity scores. In our review, we searched for randomized studies that evaluated the comparative effectiveness of adjuvant therapies in adhesion prevention and reducing adhesion severity. All adjuvant therapies were investigated and categorized into groups, including those that served as barrier methods, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and intrauterine balloons, application of biological agents (such as amnion graft, stem cells, and platelet-rich plasma), as well as dissolving or biodegradable barriers, such as intrauterine gels, mainly comprising some form of hyaluronic acid. Where estimates of comparative efficacy were not possible due to insufficient studies comparing the desired adjuvant treatments, proportional meta-analyses were conducted using single arms of each study that were treated with adjuvants within the same category.

Frequency and severity of IUA recurrence following adhesiolysis and comparative efficacy of adjuvant therapies

The data set for estimating the recurrence rate of IUAs comprised studies of patients who underwent hysteroscopic adhesiolysis for existing adhesions. To conduct adhesiolysis, surgeons typically use one or a combination of two types of instrumentation: ‘cold’ scissors, which use no energy source, or energy-based dissection with either monopolar or bipolar RF electrosurgical instrumentation. Because the choice of adhesiolysis technique could potentially affect the recurrence of IUAs, the plan for meta-analyses of studies evaluating recurrence was to conduct them separately according to the method used, in addition to meta-analyses of adhesiolysis using any technique. Understanding the limitations of heterogeneity inherent within surgical methodologies, we decided to optimize other aspects of study design by limiting these analyses to include RCTs only.

As executed for primary prevention of IUAs, we also attempted to meta-analyze the effectiveness of adjuvant therapies in secondary prevention of IUAs amongst patients undergoing hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. At the highest level, adjuvants were categorized as intrauterine barriers, intrauterine biologics, and systemic agents, comprising various designs, compositions, and durations of exposure or deployment. To support these meta-analyses, we searched for studies that evaluated the recurrence or severity of IUAs following adhesiolysis with the subsequent application of single or combined adjuvant therapies. For these analyses, studies were required to use an RCT design with at least two arms, comparing an adjuvant to another adjuvant, a combination of adjuvants, or no adjuvant. The resulting severity of adhesions was evaluated as described in the prior section, based on reported severity through either numerical or qualitative scales.

Early in the review process, it was evident that the vast majority of comparative studies utilized some combination of orally administered estrogen and progestin for a few months following adhesiolysis. While thought to facilitate the endometrial repair process, the rationale for this approach for those with functional ovaries and circulating levels of estradiol is unclear. It became apparent that excluding studies from analysis where the subjects in each arm received estrogen with or without progestin adjuvant therapy would severely limit our meta-analyses. While we decided to allow the use of estrogen-based hormonal adjuvants in the studies selected for our analyses, we separately looked to identify RCTs suitable for meta-analysis that compared post-surgical adhesion outcomes with and without gonadal hormonal adjuvants. We included only those that used one of the accepted IUA classification systems for adhesion severity. Where adhesion scores were not reported as a change from baseline as determined at the second-look hysteroscopy, the follow-up values were evaluated alone to assess the potential effect of adjuvant estrogens and progestins.

Pregnancy-related outcomes and comparative efficacy of adjuvant therapies

We sought to identify studies that reported pregnancy-related outcomes following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. These outcomes included pregnancy rates, miscarriage, and ectopic pregnancy, as well as obstetrical outcomes, including live birth, intrauterine growth restriction, premature labor and delivery, placenta previa, peripartum hemorrhage, retained placenta, and PAS. Where appropriate, studies were meta-analyzed to estimate the proportion of patients experiencing various adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The analysis of early pregnancy-related outcomes was bifurcated into primary and secondary prevention groups. The primary prevention group included studies that evaluated patients without prior IUAs undergoing uterine surgeries with known adhesiogenic risk, including hysteroscopic myomectomy, hysteroscopic metroplasty for septum correction, and surgical management of RPOC, with and without adjuvant therapies. The secondary prevention group included studies reporting on patients with known IUAs undergoing hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with and without adjuvant therapies. We further searched for studies assessing the effect of adjuvant therapies on obstetrical outcomes. Pregnancies and live births were reported as a proportion of all patients evaluated, while miscarriages were reported as a proportion of all pregnancies. Meta-analyses were further subdivided by study design.

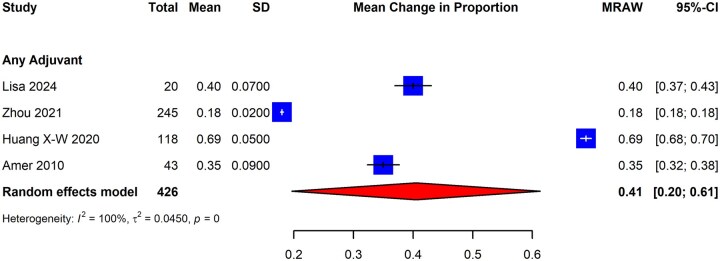

Menstrual outcomes

Patients with IUAs often present with reduced menstrual flow or amenorrhea, and surgical interventions with adhesiolysis may subsequently restore normal menstrual function (Amer et al., 2010; AAGL-ESGE, 2017; Huang et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2021). Studies included in the review evaluated the effectiveness of hysteroscopic adhesiolysis and adjuvant therapies in restoring normal menstruation. They were restricted to RCTs evaluating subjects with previously identified IUAs to improve the homogeneity of the studied population. As was the case for other outcomes, we also evaluated the impact of adjuvant therapies on menstrual outcomes in patients with IUAs.

These study outcomes were typically reported at baseline (i.e. before the index surgery) and at some follow-up time. Therefore, our analyses focused on deriving the estimates of patients with restoration of normal menstruation after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. This was calculated by deriving the mean difference between the proportion of patients achieving normal menstruation at follow-up and patients with normal menstruation at baseline. The SD for the calculated statistic was obtained using a published methodology (Berman, 2024). Studies were excluded from this analysis if they did not report on patients’ menstrual patterns, including amenorrhea, at baseline. We sought to analyze the proportion of patients with amenorrhea at the baseline who subsequently resumed normal menstruation following adhesiolysis. We also sought to analyze the proportion of patients reporting light (‘hypomenorrhea’) and infrequent (‘oligomenorrhea’) menstrual bleeding following adhesiolysis to combine findings using meta-analysis.

Endometrial thickness

Endometrial thickness (EMT) measures the endometrial echo complex (EEC) as assessed via ultrasound. A relatively thick EEC has been correlated with increased successful implantation and pregnancy maintenance rates (Baradwan et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2020). Therefore, we searched for studies investigating the change in EMT using the reported mean measurements at baseline and follow-up (Higgins et al., 2019). We derived the mean and SD using the methodology described in the Cochrane Handbook for studies that reported the statistics as median and interquartile range (Higgins et al., 2019). Finally, the calculated statistics were combined to derive the pooled SMD in EMT in the adjuvant arm compared to the non-adjuvant arm. We restricted our analysis to studies conducted using an RCT design. Additionally, studies were excluded from this analysis if they did not include a control arm (no adjuvants) as a comparator group.

Results

Literature search and screening

A search strategy was initially developed and run in PubMed (Supplementary Table S1), Embase (Supplementary Table S2), and Cochrane databases on 16 December 2022. The same search strategy was run again on PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane on 8 November 2024. After both searches were conducted, 788 articles were identified on PubMed, 1977 were identified on Embase, and 323 were identified on Cochrane. Before screening, 781 articles were removed due to duplication. In total, 2307 records received abstract screening, which excluded 1787 articles. Full-text screening took place with 450 articles, as 70 reports were not retrieved. There were 248 excluded articles from the full-text screening, resulting in 202 studies included. Hand searches also took place, with 285 articles identified and 269 reports retrieved. Full-text screening was performed on these publications, and 222 were excluded. The hand search resulted in 47 additional publications for an overall total of 249 included studies. A flow diagram of the process is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of studies identified in the systematic review.

Quality of evidence

Through the RoB assessment, study evidence quality ranged from poor to good. Most studies were of fair quality, with the second most considered to be of good quality. The smallest proportion of studies was evaluated to be of poor quality. The quality of evidence used for each meta-analysis is reported in the associated results section herein.

Background prevalence of IUAs

Observational study designs were included for this purpose, as no controlled trials were identified that quantified the prevalence of adhesions among a population before any therapeutic intervention. The review did not identify adequate studies evaluating background prevalence in individuals without previous uterine surgery. However, several studies were identified that reported data on the prevalence of IUAs amongst various at-risk groups (such as those with abnormal uterine bleeding, infertility, and recurrent pregnancy loss) who had undergone antecedent uterine curettage. Many of these studies were performed in developing countries with a relatively high prevalence of tuberculosis (Taylor et al., 1981; Valli et al., 2001; Aboulghar et al., 2011; Seckin et al., 2012; El Huseiny and Soliman, 2013; Elsokkary et al., 2018; Ajjammanavar et al., 2020; Ray-Offor and Nyengidiki, 2021). However, we did identify one study conducted in Italy that examined background prevalence among a population without a history of surgical intervention. This study identified 21 patients with IUAs among a population of 922, yielding a prevalence of 2% (Valli et al., 2001).

Incidence of IUAs among patients following potentially adhesiogenic procedures

Incidence of IUAs following hysteroscopic metroplasty for septa

The review identified eight eligible studies evaluating the incidence of new-onset IUAs in patients undergoing hysteroscopic metroplasty to correct a septum (four each using RCT and non-RCT designs) (Guida et al., 2004; Tonguc et al., 2010; Di Spiezio Sardo et al., 2011; Roy et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2016; Tafti et al., 2021; Hafizi et al., 2022). Two studies were excluded from the meta-analysis as one did not investigate the incidence of IUA after metroplasty, and the other did not have a non-adjuvant arm (Supplementary Table S3). We combined the non-adjuvant arms (inclusive of antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy use) to determine the pooled incidence. As presented in Fig. 2, the pooled incidence of new-onset IUAs post-septum correction was 28% (95% CI: 13–46%; eight studies, I2 = 91%, fair to good evidence quality). When assessed separately by RCT or non-RCT design, the incidence was 25% (95% CI: 5–52%; four studies, I2 = 85%, fair to good evidence quality) and 31% (95% CI: 9–58%; four studies, I2 = 95%, fair to good evidence quality), respectively. The measures for heterogeneity reveal substantial within-study variation in both the RCT and non-RCT subgroups. We did not identify adequate studies from the literature to evaluate adhesion severity amongst the patients undergoing metroplasty for septum correction. Additionally, we sought to study the incidence amongst the patients based on surgical technique (e.g. transection versus resection) or who had incomplete septal correction; however, sufficient studies were not available to derive the pooled estimates.

Figure 2.

Pooled results of meta-analysis for the incidence of IUAs following hysteroscopic metroplasty for septa. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; τ, tau. Events are cases where IUAs were found at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs.

All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Incidence of IUAs following hysteroscopic myomectomy

The review found eight eligible studies evaluating the incidence of new-onset IUAs in patients undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy (three and five using an RCT and non-RCT design, respectively) (Guida et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2008; Touboul et al., 2009; Di Spiezio Sardo et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013; Mazzon et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2020a; Bortoletto et al., 2022). Five other studies were excluded from the meta-analyses as the design did not include evaluation of subjects treated without adjuvants, the results contained inaccurate reporting, or the results were not stratified by approach (Supplementary Table S4).

The pooled incidence of new-onset IUAs post hysteroscopic myomectomy was 16% (95% CI: 6–28%; eight studies, I2 = 93%, fair to good evidence quality) (Fig. 3). Within the subgroups of studies conducted using either an RCT or non-RCT design, the incidence was 32% (95% CI: 21–45%; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality) and 10% (95% CI: 2–22%; five studies, I2 = 94%, fair to good evidence quality), respectively. The non-RCT subgroup had a significantly high degree of heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the incidence of IUAs following hysteroscopic myomectomy. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; τ, tau. Events include cases where IUAs were found at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

As a subsequent analysis, we meta-analyzed the included studies based on adhesion severity to estimate the proportion of post-myomectomy patients with mild, moderate, and severe adhesions as per the AFS classification system. As shown in Fig. 4, the incidence of mild IUAs was determined to be 0% (95% CI: 0–2%; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality) and 7% for moderate IUAs (95% CI: 0–27%; three studies, I2 = 85%, fair to good evidence quality), while the incidence of severe IUAs was 5% (95% CI: 0–25%; three studies, I2 = 87%, fair to good evidence quality). There were variable degrees of heterogeneity within groups.

Figure 4.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the severity of IUAs following hysteroscopic myomectomy, all study types. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; τ, tau. Events are cases with the corresponding degree of IUA severity identified at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs by category of adhesion severity using the AFS classification system. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Incidence of IUAs following abdominal myomectomy (laparoscopic or laparotomic)

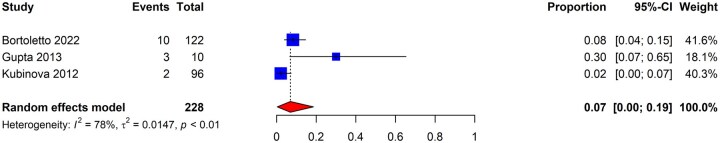

Only three eligible studies evaluated the incidence of new-onset IUAs amongst patients undergoing abdominal myomectomy (Kubinova et al., 2012; Gupta et al., 2013; Bortoletto et al., 2022). None of the studies were randomized trials; two were retrospective, and one was prospective. Bortoletto et al. (2022) evaluated a cohort of patients post laparoscopic myomectomy, whereas Gupta et al. (2013) evaluated subjects post laparotomic myomectomy. Kubinova et al. (2012) was a prospective study that evaluated patients after either myomectomy approach. No studies were excluded from the meta-analysis. As presented in Fig. 5, the overall incidence of new-onset IUAs post abdominal myomectomy was 7% (95% CI: 0–19%; three studies, I2 = 78%, fair evidence quality). There was significant within-study heterogeneity amongst the included studies. The study set was inadequate for conducting any additional analyses in this subgroup, such as by myoma phenotype. Unfortunately, insufficient studies reported on the severity of adhesions following abdominal myomectomy, and thus, this outcome could not be evaluated.

Figure 5.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the incidence of IUAs following abdominal myomectomy (laparoscopic and laparotomic), all study types. IUA, intrauterine adhesions; τ, tau. Events are cases where IUAs were found at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs. Bortoletto et al. (2022) retrospectively evaluated a cohort of patients post laparoscopic myomectomy, whereas Gupta et al. (2013) retrospectively evaluated subjects post laparotomic myomectomy. Kubinova et al. (2012) was a prospective study that evaluated patients after either myomectomy approach. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Incidence of IUAs following removal of RPOC post delivery (postpartum)

The review identified two eligible studies evaluating the incidence of new-onset IUAs in patients undergoing surgical intervention for suspected retained products following vaginal or cesarean delivery (Westendorp et al., 1998; Barel et al., 2015). One study was excluded due to the duplication of findings compared to those reported in Barel et al. (2015) (Supplementary Table S5). Figure 6 shows that the overall incidence of new-onset IUA post RPOC was 24% (95% CI: 15–34%; two studies, I2 = 16%, fair evidence quality). Both included studies were conducted using a retrospective study design. Barel et al. (2015) evaluated a cohort of patients who exclusively underwent a hysteroscopic approach to removal of RPOC. In contrast, Westendorp et al. (1998) included patients who exclusively underwent dilation and sharp curettage. The included studies had minimal within-study heterogeneity. The study set was inadequate for conducting any additional analyses in this subgroup, such as analysis by surgical technique.

Figure 6.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the incidence of IUAs following removal of retained products of conception post-delivery (postpartum), all study types. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; τ, tau. Barel et al. (2015) retrospectively evaluated subjects who exclusively underwent a hysteroscopic approach to removal of RPOC. Westendorp et al. (1998) retrospectively evaluated patients who underwent dilation with sharp curettage. Events include cases where IUAs were found at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Incidence of IUAs following removal of POC in the first trimester

The review identified 13 eligible studies to evaluate the incidence of IUAs in patients undergoing removal of POC following spontaneous pregnancy loss (three and 10 using RCTs and non-RCT study designs, respectively) (Golan et al., 1992; Friedler et al., 1993; Westendorp et al., 1998; Tam et al., 2002; Salzani et al., 2007; Cogendez et al., 2011; Kuzel et al., 2011; Seckin et al., 2012; Barel et al., 2015; Gilman et al., 2016; Hooker et al., 2017; Vatanatara et al., 2021; Sroussi et al., 2022). No studies that reported the outcome of interest in the identified population were excluded from the meta-analysis. Studies that reported on patients who underwent one or more surgical procedures to remove POC were included. We combined the non-adjuvant arms (inclusive of antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy use) to determine the pooled incidence and then separately analyzed studies based on study design (RCTs versus non-RCTs). As presented in Fig. 7, the pooled incidence of IUAs post first trimester evacuation of POC was 17% (95% CI: 11–25%; 13 studies, I2 = 87%, poor to good evidence quality). Within the subgroups of studies conducted using the RCT and non-RCT designs, the incidence was determined to be 30% (95% CI: 15–48%; 3 studies, I2 = 83%, poor to good evidence quality) and 14% (95% CI: 8–21%; 10 studies, I2 = 86%, poor to fair evidence quality), respectively. The RCTs had minimal within-study heterogeneity, while we observed greater heterogeneity among non-RCT studies. We did not identify any peer-reviewed studies evaluating the incidence of IUAs following elective termination of a viable first trimester pregnancy.

Figure 7.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the incidence of IUAs following removal of products of conception in the first trimester. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; τ, tau. Events include cases where IUAs were found at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs. All patients experienced spontaneous pregnancy loss. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

The study set was inadequate for conducting additional analyses in this subgroup; we were unable to distinguish outcomes between patients with scheduled and unscheduled (‘urgent’ or ‘emergent’) procedures. The analysis for severity of IUAs amongst patients who underwent removal of POC in the first trimester following spontaneous pregnancy loss revealed that the proportion of patients diagnosed with mild, moderate, and severe IUAs as per the AFS classification system was 13% (95% CI: 8–19%; seven studies, I2 = 66%, poor to good evidence quality), 7% (95% CI: 3–12%; seven studies, I2 = 75%, poor to good evidence quality), and 1% (95% CI: 0–3%; seven studies, I2 = 37%, poor to good evidence quality), respectively (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the severity of IUAs following removal of products of conception in the first trimester, all study types. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; τ, tau. Events are cases with the corresponding degree of IUA severity identified at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs by category of adhesion severity using the AFS classification system. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Recurrence of IUAs following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis

The review identified 50 eligible studies that evaluated the recurrence of IUA following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. Of those, only 13 included a cohort without adjuvant therapies and could be used to determine the IUA recurrence rate (two and 11 using RCT and non-RCT study designs, respectively) (Capella-Allouc et al., 1999; Acunzo et al., 2003; Zikopoulos et al., 2004; Robinson et al., 2008; Chang et al. 2010; Roy et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2013; Bhandari et al., 2015; Hanstede et al., 2015; Thubert et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019a; Fei et al., 2021; Fernandez et al., 2024). There were four studies excluded from the meta-analysis that did not utilize hysteroscopy for evaluation or had inadequate methodology (Supplementary Table S6). We combined the non-adjuvant arms (inclusive of antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy use) to determine the pooled recurrence rate and then separately analyzed studies based on study design (RCT versus non-RCTs). As presented in Fig. 9, the pooled recurrence rate in patients following adhesiolysis without adjuvant therapies was 35% (95% CI: 24–46%; 13 studies, I2 = 95%, poor to good evidence quality). Within the subgroups of studies conducted using either RCT or non-RCT design, the incidence was 53% (95% CI: 23–82%; two studies, I2 = 92%, good evidence quality) and 31% (95% CI: 22–41%; 11 studies, I2 = 94%, poor to good evidence quality), respectively.

Figure 9.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the recurrence of IUAs following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; τ, tau. Events are cases where recurrent IUAs were identified at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

We meta-analyzed the included studies that reported adhesion severity at the time of second-look hysteroscopy. Of the 13 studies with non-adjuvant arms, only five were adequate for meta-analysis (Acunzo et al., 2003; Thubert et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019a; Fernandez et al., 2024); all utilized the AFS classification system to provide numerical severity data to estimate the proportion of post-adhesiolysis patients with mild (Stage 1: scoring from 1 to 4), moderate (Stage 2: scoring from 5 to 8), and severe adhesions (Stage 3: scoring ≥9). As shown in Fig. 10A, the mean AFS score of recurrent IUAs post hysteroscopic adhesiolysis was 3.35 (95% CI: 2.11–4.58; five studies, I2 = 99%, poor to good evidence quality), corresponding to AFS Stage 1 (mild) adhesions.

Figure 10.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the severity of IUA following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis, all study types. (A) Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the mean IUA severity following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis utilizing the AFS classification system, all study types. IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; AFS, American Fertility Society; SD, standard deviation; MRAW, raw mean. (B) Pooled results of the meta-analysis for categorical IUA severity following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis, all study types. τ, tau. Each study utilized a different classification system: Acunzo et al. (2003) utilized AFS, Robinson et al. (2008) utilized March, and Bhandari et al. (2015) utilized ESGE. To allow for meta-analyses of studies using different classification systems, the severities were re-categorized as mild, moderate, or severe following the protocol described by Hooker et al. (2014). Events are cases with the corresponding degree of IUA severity identified at second-look hysteroscopy. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs by category of adhesion severity. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Additionally, only three studies with non-adjuvant arms reported on categorical IUA severity at the time of second-look hysteroscopy were adequate for meta-analysis (Acunzo et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2008; Bhandari et al., 2015); each study utilized a different classification system (AFS, March, and ESGE, respectively). To allow for meta-analyses of the studies, the severities were reconciled and re-categorized as mild, moderate, or severe using the protocol described by Hooker et al. (2014). As shown in Fig. 10B, the proportion of patients with mild adhesions was determined to be 25% (95% CI: 2–60%; three studies, I2 = 93%, fair to good evidence quality); for moderate adhesions, it was 25% (95% CI: 18–34%; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality), and for severe adhesions, it was 5% (95% CI: 0–27%; three studies, I2 = 92%, fair to good evidence quality). The study set was inadequate for conducting additional analyses in this subgroup. Surgical techniques were often insufficiently described in the literature; thus, we did not find adequate studies to estimate the pooled recurrence of IUAs based on surgical technique, and no associations can be made between the severity of IUAs and the surgical technique used.

Comparative effectiveness of adjuvant therapies for IUA prevention

In addition to the proportional analysis of the incidence and recurrence of IUAs, we also investigated the comparative effectiveness of adjuvant therapies in IUA prevention among the primary and secondary prevention subgroups. For these analyses, we only included RCT study designs with at least two arms, comparing an adjuvant to either no adjuvant, another adjuvant, or a combination of adjuvants.

Primary prevention of IUAs

The review identified a range of randomized trials that have evaluated the efficacy of adjuvant therapies for primary prevention of IUAs following potentially adhesiogenic procedures. In this analysis, we identified eight randomized trials that exclusively compared adjuvants with a non-adjuvant arm (inclusive of antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy use) (Guida et al., 2004; Tonguc et al., 2010; Di Spiezio Sardo et al., 2011; Hooker et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2020a; Tafti et al., 2021; Vatanatara et al., 2021; Sroussi et al., 2022). Three studies were excluded from the meta-analysis that did not meet this criterion (Supplementary Table S7). Summary data on included studies for meta-analysis of primary prevention can be found in Supplementary Table S8. Of the eight studies meeting inclusion criteria, three evaluated a cohort of patients post removal of POC in the first trimester following spontaneous pregnancy loss, three post hysteroscopic myomectomy, and four post hysteroscopic metroplasty; gel was utilized as the adjuvant therapy in all these studies except for one (Tonguc et al., 2010).

We executed a separate analysis for each potentially adhesiogenic procedure. Figure 11 presents the data selectively for the seven randomized trials that utilized gel as the adjuvant therapy, given the Tonguc et al. (2010) study was an outlier that evaluated the use of an IUD as adjuvant therapy and significantly altered the RR ratio within the hysteroscopic metroplasty subgroup (data for all four trials within the metroplasty subgroup are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1). As presented in Fig. 11, the RR of de novo IUA formation for patients undergoing primary prophylaxis with gel barrier adjuvants was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.30–0.68; three studies, I2 = 0%, poor to good evidence quality) following removal of POC in the first trimester for spontaneous pregnancy loss, 0.38 (95% CI: 0.20–0.73; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair evidence quality) following hysteroscopic myomectomy, and 0.29 (95% CI: 0.12–0.69; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality) following hysteroscopic metroplasty for septa. While various biodegradable gel prophylactic therapies were utilized in these studies, the addition of hyaluronic acid as a component of the gel barrier was noted in all studies except for one (Di Spiezio Sardo et al., 2011). There were inadequate studies reporting the severity of adhesions following adhesiolysis utilizing adjuvant therapy; thus, this outcome could not be evaluated. Furthermore, we did not find adequate studies to estimate the pooled recurrence of IUAs based on surgical technique.

Figure 11.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the comparative effectiveness of gel adjuvant therapies versus no adjuvant for primary prevention of adhesions following potentially adhesiogenic procedures (RCT study design only). IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; τ, tau. Events are cases where IUAs were identified at second look hysteroscopy. Adjuvant indicates cases receiving gel adjuvant. Control refers to cases receiving no adjuvant. While various biodegradable gel prophylactic therapies were utilized in these studies, the addition of hyaluronic acid as a component of the gel barrier was noted in all studies except for Di Spiezio Sardo et al. (2011). All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Secondary prevention of IUAs

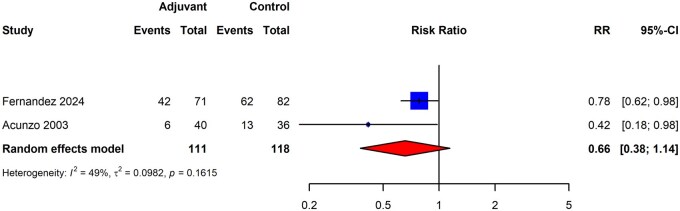

We analyzed the risk of IUA recurrence in the secondary prevention groups, comparing adjuvant therapies. We identified 18 randomized trials that evaluated the efficacy of adjuvant therapies in secondary prevention of IUAs following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis (Acunzo et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2015; Gan et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020, 2022b; Wang et al., 2020b, 2022a,b; Huang et al., 2020b; Pan et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2022; Hanstede et al., 2023; Fernandez et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2024). There were 25 studies excluded due to either non-RCT design, lack of diagnostic hysteroscopy for patient evaluation, unspecified technique of adhesiolysis, or other reasons (Supplementary Table S9). Summary data on included studies for meta-analysis of secondary prevention can be found in Supplementary Table S10. To be eligible for inclusion, all studies must have reported on the rate of IUA recurrence. Unfortunately, there were inadequate studies reporting on the severity of adhesions following adhesiolysis utilizing adjuvant therapies, and thus, this outcome could not be evaluated. Furthermore, we did not find adequate studies to estimate the pooled recurrence of IUAs based on surgical technique.

We identified only two RCTs (Acunzo et al., 2003; Fernandez et al., 2024) that exclusively compared a single adjuvant therapy to a non-adjuvant for secondary prevention of IUA recurrence post adhesiolysis; both utilized a biodegradable barrier for secondary prevention. Acunzo et al. (2003) utilized a traditional gel adjuvant, while Fernandez et al. (2024) positioned a hydrophilic polymer film within the endometrial cavity that expands in situ to form a biodegradable barrier. Based on our inclusion criteria, one otherwise eligible RCT that also utilized a biodegradable gel barrier (Mao et al., 2020) was excluded due to the methodological description of the study not requiring post-adhesiolysis hysteroscopy to determine the presence and severity of IUAs. Furthermore, the study protocol also included a repeat injection of hyaluronic acid into the endometrial cavity 5–7 days following the initial adhesiolysis. The authors did not respond to two e-mail attempts to resolve this issue. The resulting meta-analysis demonstrated a risk ratio of 0.66 for recurrence of IUA post hysteroscopic adhesiolysis (two studies, I2 = 49%, good evidence quality), though the 95% CI of 0.38–1.14 did not allow for a conclusion of benefit to be made (Fig. 12). However, to assess the effect of including the Mao et al. (2020) study, a separate meta-analysis was conducted that demonstrated a risk ratio of 0.78 (three studies, I2 = 46%, fair to good evidence quality) but the 95% CI of 0.53–1.14 still did not allow for a conclusion of benefit to be made (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 12.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the comparative effectiveness of biodegradable barriers versus no adjuvant for secondary prevention of adhesions following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis (RCT study design only). IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; τ, tau. Adjuvant indicates cases receiving a biodegradable barrier. Acunzo et al. (2003) utilized a traditional gel adjuvant, while Fernandez et al. (2024) positioned a hydrophilic polymer film within the endometrial cavity that expands in situ to form a biodegradable barrier. Control refers to cases receiving no adjuvant. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapies.

A meta-analysis was performed using all 18 randomized trials that evaluated the efficacy of different adjuvant therapies in the secondary prevention of IUAs. The review identified three adjuvant therapy subgroups eligible for meta-analysis: IUD, biodegradable barriers, and intrauterine balloons. As presented in Fig. 13A, the IUA recurrence rate for patients undergoing secondary prophylaxis was the lowest among patients treated with biodegradable barriers, with an overall rate of 28% (95% CI: 4–62%; three studies, good evidence quality). The recurrence rate was 43% for both intrauterine balloon (95% CI: 35–51%; 14 studies, poor to good evidence quality) and IUD (95% CI: 27–59%; four studies, fair to good evidence quality) adjuvant therapies post adhesiolysis. We found a high degree of heterogeneity amongst the studies evaluating the intrauterine balloon adjuvants (I2 of 85%), IUDs (I2 of 85%), and biodegradable barriers (I2 of 94%).

Figure 13.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the recurrence of IUAs following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with adjuvant therapy for secondary prevention of adhesions (RCT study design only). (A) Pooled recurrence of IUAs when using adjuvant therapies for secondary prevention of adhesions (RCT study design only). IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; τ, tau. Events are cases where recurrent IUAs were identified at second-look hysteroscopy for each specified adjuvant category. Proportion refers to the risk of finding IUAs at second-look hysteroscopy by adjuvant type. Within the biodegradable barriers, Wang Y.Q. et al. (2020) and Acunzo et al. (2003) utilized a traditional gel adjuvant, while Fernandez et al. (2024) positioned a hydrophilic polymer film within the endometrial cavity that expands in situ to form a biodegradable barrier. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy. (B) Pooled recurrence of IUAs when using adjuvant therapies for secondary prevention with and without the concomitant use of systemic estrogens and progestins (RCT study design only). RR, risk ratio. Events on the left are cases where recurrent IUAs were identified at second-look hysteroscopy with the specified adjuvant along with systemic estrogen/progestin. Events on the right are cases where recurrent IUAs were identified at second-look hysteroscopy when the specified adjuvant was used without a systemic estrogen/progestin. The adjuvant used by Hanstede et al. (2023) was an inert (copper removed) ‘T-shaped’ intrauterine contraceptive device, while Yang et al. (2022b) used an intrauterine Foley balloon. (C) Pooled mean difference in the severity of recurrent IUAs when using adjuvant therapies with and without the concomitant use of systemic estrogens and progestins using the AFS classification system (RCT study design only). A, adjuvant; H, hormones—systemic estrogen/progestin; MD, mean difference; RCT, randomized controlled trial; τ, tau. The adjuvant used by Hanstede et al. (2023) was an inert ‘T-shaped’ intrauterine contraceptive device while Yang et al. (2022b) used an intrauterine Foley balloon.

Additional meta-analysis was performed on the two RCTs that compared the adjuvant use of barriers (IUD and intrauterine balloon, respectively) with and without concomitant use of systemic estrogens and progestins to evaluate the impact of these gonadal steroids on IUA recurrence following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis (Yang et al., 2022b; Hanstede et al., 2023). The pooled risk ratio of IUA recurrence after adhesiolysis was 1.05 (95% CI: 0.76–1.47; two studies, poor to good evidence quality), as presented in Fig. 13B. The same studies were subjected to meta-analysis to determine whether systemic estrogens and progestins impacted the severity of recurrent adhesions. As published data in the study by Hanstede et al. (2023) were not sufficient for analysis, we contacted the author, who was able to provide patient-level data on the baseline and follow-up of patients in her study. This analysis relied on the follow-up data for these two studies, as a change from baseline to follow-up was not originally reported, and only summary statistics were available from Yang et al. (2022b). This was deemed feasible based on guidance from Cochrane (Higgins et al., 2019) as well as statistical tests that found no difference in baseline scores. The results of this meta-analysis are displayed in Fig. 13C, with a mean difference of 0.14 (95% CI: −0.31 to 0.60; two studies, I2 = 0%, poor to good evidence quality). In summary, these results suggest that the use of post-adhesiolysis systemic estrogen and progestin regimens does not significantly affect the severity of recurrent adhesions.

We next sought to compare the effectiveness of different adjuvants for secondary prevention of IUA recurrence in a head-to-head fashion, grouping them according to the following categories: gel, IUD, intrauterine balloon, biologic agents (e.g. plasma-rich protein), amnion graft, and various combinations of adjuvant therapies. We identified a total of seven eligible studies; three evaluated a combination of gel with intrauterine balloon compared to intrauterine balloon alone (Xiao et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2022), two evaluated a combination of amnion graft with intrauterine balloon compared to intrauterine balloon alone (Gan et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2022a), and two evaluated intrauterine balloon compared to IUD as adjuvant therapies (Lin et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022b). Unfortunately, we did not identify sufficient studies that exclusively compared other subgroups directly. Most head-to-head comparisons were impossible due to a lack of eligible studies making equivalent comparisons, leading to the exclusion of nine studies (Supplementary Table S11).

Figure 14 presents the meta-analyses for head-to-head adjuvant comparative efficacy that were feasible. The RR for the combination of gel with intrauterine balloon was found to be 0.78 (95% CI: 0.64–0.95; three studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality), which corresponds to a RR reduction of 22% over intrauterine balloon alone, signaling marginally greater efficacy of intrauterine balloons when used in combination with gel adjuvants for secondary prevention of adhesion recurrence. In addition, we compared head-to-head intrauterine balloon adjuvants directly with IUD adjuvants and determined the RR to be 0.88 (95% CI: 0.66–1.18; two studies, I2 = 0%, fair evidence quality), which reflects that there is no statistically significant difference between these two groups of adjuvant therapies when used alone. Finally, a comparison of the combination of amnion graft with intrauterine balloon versus intrauterine balloon alone determined the RR to be 0.61 (95% CI: 0.35–1.06; two studies, I2 = 0%, fair to good evidence quality), which again reflects no statistically significant difference between these two groups of adjuvant therapies.

Figure 14.

Pooled results of the meta-analysis for the comparative effectiveness of different adjuvant therapies for secondary prevention of adhesions following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis (RCT study design only). IUAs, intrauterine adhesions; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; τ, tau. Group A represents the first listed adjuvant while Group B represents the second listed adjuvant, e.g. in ‘Gel & Balloon vs Balloon’, Group A = Gel & Balloon and Group B = Balloon. Events are cases where recurrent IUAs were identified at second-look hysteroscopy for each specified category of adjuvant versus adjuvant. All cases could have received antibiotics and/or estrogen-based hormone therapy.

Pregnancy outcomes among patients following adhesiolysis

Early pregnancy