ABSTRACT

Background

In certain types of solid tumors, nuclear factor of activated T cell 5 (NFAT5) plays critical roles in tumor development and progression. However, the subtle regulatory mechanism of NFAT5 in particularly lung cancer has not been well characterized.

Methods

In this report, we measured the levels of interleukin‐8 (IL8) in NSCLC cell lines. The target gene of IL8 was verified by ChIP assay and Luciferase reporter assay. Moreover, the function and regulatory mechanism of IL8 in the progression of cancer were further investigated.

Results

ELISA assay showed that IL8 was significantly downregulated in NFAT5 silencing PC9 cells and HCC827 cells. NFAT5 silencing caused inhibiting effects on proliferation, migration, and invasion in NSCLC cell lines. Further analysis indicated that IL8 was a direct target gene of NFAT5, evidenced by the direct binding of NFAT5 to the promoter of IL8. Elevated IL8 further enhanced the activation of the canonical NF‐κB pathway.

Discussion

Our findings provide new insight into the mechanism of NSCLC progression. NFAT5 promotes cell growth and motility by regulating IL8 directly in NSCLC cell lines. Elevated IL8 expression causes enhancement of the NF‐κB signaling pathway partially through autocrine or paracrine effects. These findings provide a possible mechanism of the inflammatory environment on lung cancer progression.

Keywords: growth, IL8, migration, NFAT5, NF‐κB, NSCLC

Proposed mechanism for the role of NFAT5 in NSCLC progression. NFAT5 could promote cell growth and motility by regulating IL8 directly in NSCLC cell lines. Elevated IL8 expression caused enhancing NF‑κB signaling pathway partially through autocrine or paracrine effects.

1. Introduction

Lung cancer still remains the leading cause of cancer‐related mortality in China and the rest of the world [1], which is mainly composed of non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). According to the previous studies, NSCLC has been demonstrated to be a typical inflammation‐associated carcinoma. Chronic inflammation plays crucial roles in the promotion of carcinogenesis and metastasis, especially for those nonsmokers. It has been shown that interleukin‐8 (IL8), a strong pro‐inflammatory cytokine, contributes to lung cancer progression directly or indirectly [2].

Nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) family proteins were first identified in T cells. Later, it was found that NFAT was also expressed in other cells, including normal cells and cancer cells. Although NFAT5 also has a highly conserved Rel‐homology domain, it cannot be activated by calcineurin because of the lack of an NHR. Like NFAT1‐4, NFAT5 plays crucial roles in cancer initiation and migration [3]. It has been demonstrated that NFAT5 expression is an independent risk factor for disease‐free survival (DFS) of NSCLC patients who underwent surgical resection [4]. In the current study, we identified IL8 as the downstream target gene of NFAT5 in NSCLC cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Human lung adenocarcinoma PC9 cells and HCC827 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Both of them were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 g/mL streptomycin. They were incubated in a humidified incubator (37.0°C) with 5% CO2. NFAT5 targeting shRNA 5′‐TTTCCAT‐3′. Transfections were performed according to the protocol.

2.2. Protein Extraction

The proteins of cells were extracted using RIPA buffer. Protein concentrations were measured with a BCA protein assay kit. Equal amounts of protein lysate were loaded onto 8% or 10% SDS‐PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes.

2.3. Western Blotting

Total protein lysates were prepared from the cells and quantified using the BCA protein assay. Equal amounts of protein samples were resolved on an SDS‐PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, MA). Then, the membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following. The following antibodies were used: NFAT5 (ab3446; 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), NF‐κB p65 (#8242; 1:1000, CST, MA), MMP2 (ab92536; 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), beta‐Tubulin (ab314069; 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), GAPDH (ab8245; 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

2.4. Wound Healing Assay

Briefly, NSCLC cells (PC9 and HCC827) and those with NFAT5 knockdown were seeded overnight into 6‐well plates and grown until 100% confluency was achieved. Then, the monolayers of cells were wounded across the center of the well using a 10 μL pipette tip. The cells were washed twice to remove the detached cells and cell debris. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 24 h in the maintenance medium (RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 5‰ fetal bovine serum). Subsequently, wound closure or cell migration was assessed by capturing images using a light microscope.

2.5. Transwell Migration and Invasion Assays

The transwell migration assay and transwell invasion assay were conducted with a transwell chamber (Beyotime Biotechnology, Beijing, China). NSCLC cells suspended in 200 μL serum‐free RPMI‐1640 medium were seeded in the upper compartment of the chamber, and 600 μL RPMI‐1640 medium with 20% FBS was added to the lower compartment of the chamber. Then each group of cells was incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the migrating/invasive cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde fix solution (Beyotime Biotechnology, Beijing, China), stained with crystal violet staining solution (Beyotime Biotechnology, Beijing, China), and photographed under a light microscope. For the invasion assay, the upper compartment was precoated with 40 μL Matrigel. All other processes were the same as for the transwell migration assay.

2.6. Xenograft Model in Nude Mice

4–5‐week‐old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the SPF Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The mice were divided into two groups: the NC group and the NFAT5 silencing group. 1 × 107 PC9 cells were suspended separately and then injected into the right flank of a nude mouse subcutaneously. At the end of the study, animals were euthanized in CO2 atmosphere under sterile conditions by cervical dislocation. Tumor volumes were calculated, and the tumor xenografts were harvested.

2.7. ELISA for IL8

The level of IL8 in the culture supernatant was measured with an ELISA kit (Cat#: 1110802, Dakewe Biotech Co. Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The detection threshold limit for IL8 was 25 pg/mL.

2.8. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

The ChIP assay was performed using the ChIP‐IT Express Kit based on the manufacturer's instruction. PCR was performed by using the following primers that can identify both NFAT5 binding sites: NFAT5‐F‐500‐GCTCAAACTGCCAGCAAAAT‐30 and NFAT5‐50CA‐CAGGGTGTTCACAAATCG‐30.

2.9. Reporter Constructs and Luciferase Activity Analysis

The IL8 promoters were cloned from HCC827 and PC9 cells to encompass IL8 base pairs upstream of the transcriptional initiation sites. According to the manufacturer's instructions, direct site mutagenesis of NFAT5‐binding sites was performed using the QuikChange II XL Site‐Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). After 48 h, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity was assayed with the Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The in vitro data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 8.0 software, and values were presented as mean ± SEM. Student's t‐tests were used to analyze the statistical significance. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of NFAT5 Expression in NSCLC Cells

In recent years, increasing evidence indicates the significant roles of NFAT5 in NSCLC, especially in tumorigenesis and progression [5, 6]. It has been reported that NFAT5 is upregulated in certain types of solid tumors including NSCLC. In this study, the status of NFAT5 was examined in NSCLC cell lines. Western blot analysis showed that cell lines PC9 and HCC827 expressed high levels of NFAT5.

To establish the role of NFAT5 in growth and metastasis, we chose to stably silence NFAT5 in these two highly metastatic cell lines. HCC827 and PC9 were stably transduced with NFAT5 shRNA packaged lentivirus. Western blot analyses revealed that the HCC827 and PC9 cell lines had knockdown of NFAT5, respectively, compared with the negative control (Figure 1). These two cell lines were used throughout the study.

FIGURE 1.

The status of NFAT5 expression in HCC827 and PC9 cell lines and silencing of NFAT5 in these cells.

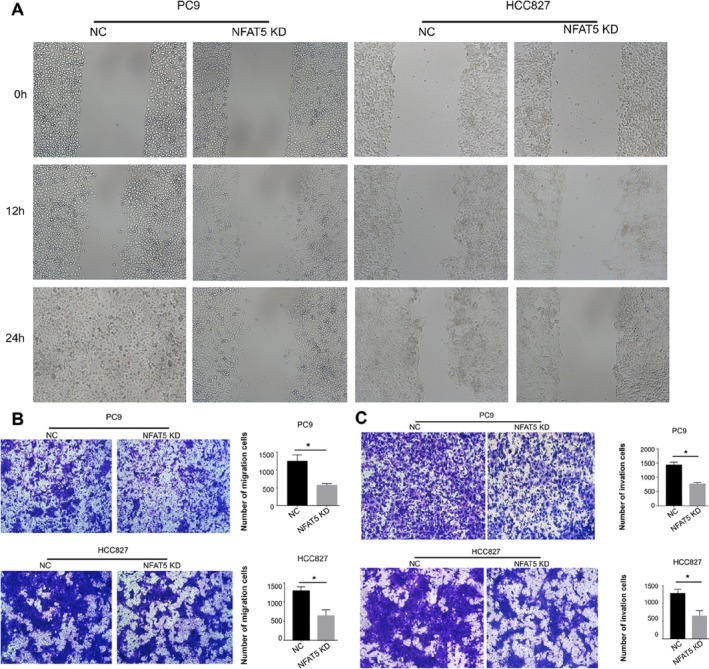

3.2. In Vitro Invasive Phenotype of NSCLC Cells Following NFAT5 Silencing

Next, transwell migration and wound healing assays were performed to measure the ability of HCC827 and PC9 cells. Compared with the NC group, NFAT5‐shRNA significantly reduced the migration efficiency of HCC827 and PC9 cells (Figure 2A,B). We also analyzed the ability of these cells to invade through Matrigel‐coated filters. A significant reduction in the number of invading NSCLC cells was observed after silencing NFAT5 in both cell lines (Figure 2C). Therefore, we speculated that NFAT5 is critical for the invasive phenotype of HCC827 and PC9 cells.

FIGURE 2.

(A) The cell migration ability of NSCLC cells was assessed by wound healing migration assay. (B) The cell migration ability of NSCLC cells was assessed by transwell migration assay. The data expressed as the mean ± SD (*p < 0.05). (C) Silencing of NFAT5 in both HCC827 and PC9 cell lines resulted in reduced invasion through Matrigel‐coated filters (*p < 0.05).

3.3. In Vitro and In Vivo Effect of NFAT5 on Tumor Growth

We next analyzed the role of NFAT5 on tumor growth in vitro. Colony formation assay was performed, and it was found that NFAT5‐shRNA cells were largely reduced compared to the NC group (Figure 3A). In the animal studies, we observed a significant decrease in tumor growth after silencing NFAT5 in PC9 cells. With limitations of tumorigenicity assay, we speculated that NFAT5 may also play roles of importance in tumor growth. However, we decided to focus our research on the potential downstream regulatory mechanism of NFAT5 on cell motility.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of NFAT5 on tumor growth. (A) Colony formation assay in PC9 and HCC827 cells expressing NFAT5‐NC and NFAT5‐shRNA. (B) Tumor growth was significantly decreased after silencing of NFAT5 in PC9 cells.

3.4. Identification of IL8 as Downstream Target Gene

We focused our attention on genes that were downregulated after silencing of NFAT5 because they were likely to be the tumor promoter genes. According to previous studies, NFAT5 can play cancer‐promoting roles directly or indirectly. As a transcription factor, NFAT5 may regulate gene expression by directly binding to certain promoter regions. It has been demonstrated that NFAT5 is an important component for the regulation of S100A4 in colon cancer cells under the condition of hyperosmotic stress [7]. It has also been reported that the expression of aquaporin‐5 (AQP5) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp 70) may be regulated by NFAT5 in lung adenocarcinoma cells [8, 9]. However, there is no direct evidence that they are regulated at the transcriptional level by NFAT5 in lung cancer research. Since the NFAT protein adopts a NF‐κB‐like structure upon binding to DNA, NFAT5 may cross‐regulate gene expression in certain cellular contexts [10]. As is well known, lung cancer is a typical inflammation‐associated carcinoma. In this study, certain cytokines such as IL8, TGF‐α, IL‐6, IFN‐γ, and so forth were measured by the ELISA test. The ELISA assay showed that there was a statistical difference in IL8 levels between NFAT5‐NC and NFAT5‐shRNA (Figure 4A). As for the rest of the cytokines, no significant statistical difference was observed in PC9 or HCC827 cell lines between the NFAT5‐NC and NFAT5‐shRNA groups. Thus, we conclude that IL8 is overexpressed in metastatic human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines and that the secretion of IL8 may be regulated by NFAT5.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of IL8 as NFAT5 downstream target genes. (A) Effect of NFAT5 on IL8 expression and secretion. ELISA assay for the secreted IL8 protein demonstrating that NFAT5 silencing reduced the secretion of IL8 in both PC9 and HCC827 NSCLC lines (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001). (B) ChIP of NFAT5 on the IL8 promoter. NFAT5 binds to the promoter region of IL8. Binding was lost when NFAT5 was silenced in PC9 cells. (C) In PC9 cells, silencing NFAT5 significantly reduced the luciferase activity driven by the wild‐type IL8 promoter compared with shRNA. Mutating NFAT5‐binding sites resulted in reduced promoter activity (**p < 0.001).

IL8 plays critical roles in the progression and metastasis of certain solid cancers, including lung cancer [11, 12, 13]. Based on ELISA data, we hypothesized that NFAT5 may contribute to lung cancer tumor growth and metastasis through the regulation of IL8. Next, we performed ChIP assays to verify the binding of NFAT5 to IL8 promoters. As shown in Figure 4B, NFAT5 bound to the promoter of IL8 in PC9 cells. When NFAT5 was silenced, no binding to the IL8 promoter was detected in the PC9 cell line. The ChIP assay confirmed that NFAT5 binds to the IL8 promoter and that binding is lost after NFAT5 silencing. To determine whether NFAT5 regulates IL8 at the transcriptional level, we used a dual luciferase reporter gene promoter assay designed so that the IL8 promoter was cloned in front of the luciferase. The promoter was designed with and without mutations in the IL8 promoter NFAT5‐binding site. As shown in Figure 4C, silencing NFAT5 resulted in a reduction of luciferase activity compared with the NC group. From the above findings, we conclude that the reduced promoter activity is a direct result of reduced binding of NFAT5 protein to the IL8 promoter.

3.5. IL8 Promotes Tumor Progression via the NF‐κB Pathway

It is well known that IL8 is a kind of secretome protein. Secreted by NSCLC cells, IL8 exerts its tumor‐promoting activity through autocrine or paracrine effects. Videlicet, NFAT5 elevates IL8 secretion levels by binding to the IL8 promoter directly, which in turn binds to its receptors or other tumor cell receptors and promotes tumor proliferation or mobility ultimately. It has been well established that IL8 can exert its activity via the NF‐κB pathway in certain types of solid tumors [14, 15, 16, 17]. Therefore, IL8, secreted by PC9 and HCC827 cells, may also promote proliferation and motility of lung cancer. To ascertain that, NF‐κB protein was measured by Western blot analysis in both PC9 and HCC827 cells with or without NFAT5 silencing. As shown in Figure 5A, NF‐κB protein, P65 in this study, decreased after NFAT5 knockdown. The expression level of P65 protein was consistent with that of NFAT5. It was observed that matrix metalloproteinases 2 (MMP2) also decreased in NFAT5 silencing cell lines. In previous studies, MMP9 and MMP2 were involved in lung jure in animal models [18, 19]. However, in this study, MMP9 was not downregulated in lung adenocarcinoma cells as the knockdown of NFAT5 did. In summary, NFAT5 may regulate lung cancer cell invasiveness via the NF‐κB pathway by modulating the expression of MMP‐2 mainly. Moreover, the roles of MMP‐2 in the invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells have been confirmed by precious studies [20, 21, 22, 23].

FIGURE 5.

Relationship between NFAT5 and NF‐κB. (A) Expression levels of both NF‐κB and MMP2 decreased in NFAT5 silencing lung cancer cells, compared to those of the NC group. (B) Expression levels of both NFAT5 and p‐P65 in NFAT5 silencing PC9 cells by addition of IL8 at different times. (C) Nuclear transition of p‐P65 in NFAT5 silencing PC9 cells was observed after IL8 was given.

To verify the hypothesis, we rescued the expression of NFAT5 in the PC9 cells. The data showed that p‐P65 was upregulated, combining with a rise in the expression level of NFAT5 (Figure 5B). Nuclear transition of p‐P65 in PC9 cells was also observed in this recovery experiment (Figure 5C), which was a very important step in the activation of the canonical NF‐κB pathway. Thus, we speculated that NFAT5 promotes tumor progression of NSCLC cancer by directly regulating IL8, which was responsible for the activation of the canonical NF‐κB pathway. MMP2 may also play a critical role in the invasion of PC9 and HCC827 cell lines.

4. Discussion

Roles of NFAT5 in the osmotic pressure regulation and immune regulation are well established. Recently, lung endothelial cells have been found to be a protective transcription factor required to adjust the transcriptome to cope with hypoxia for lung endothelial cells [24]. In certain types of solid tumors, including lung cancer, NFAT5 also plays critical roles in tumor development and progression. It has been reported that a range of miRNAs such as miR‐194, miR‐613, miR‐625‐5p, miR‐107, miR‐34a‐5p, and so on [5, 6, 25, 26, 27]. However, the subtle regulation mechanism of NFAT5 in particularly lung cancer needs further elucidation. It has also been reported that the expression of AQP5 and Hsp 70 may be regulated by NFAT5 in lung adenocarcinoma cells [8, 9]. However, there is no direct evidence that they are regulated at the transcriptional level by NFAT5 in lung cancer research. In this study, we demonstrated that NFAT5 expression positively correlated with the invasive phenotype in NSCLC cell lines. Unlike the repair proteins AQP5 and Hsp 70, certain cytokines such as IL8, TGF‐α, IL‐6, IFN‐γ, and so forth were measured by ELISA test in our study. The ELISA assay showed that IL8 expression positively correlated with the expression of NFAT5. Therefore, we focused on the identification of IL8 as a downstream target gene of NFAT5 in lung cell lines. ChIP assay, reporter constructs, and luciferase activity analysis in PC9 cells, promoter analyses, and ChIP assays demonstrated that NFAT5 binds to the promoter of IL8. This finding meets the need for the direct regulatory mechanism of NFAT5 in lung adenocarcinoma cells.

As the only member of the Rel/NFAT family to be activated by osmotic stress, NFAT5 has been concerned about the changes in the biological behavior of cancer cells under osmotic stress [7]. At present, NFAT5 is worthy of attention for bridging the inflammatory environment and tumor development. It is well known that cytokines in the tumor microenvironment belong to the secretome protein. Thus, IL8, which is regulated directly by NFAT5, exerts activities after secretion from a tumor cell through autocrine or paracrine effects. In other words, its roles in the tumor microenvironment inevitably involve the connection between tumor cells or the connection between tumor cells and other cells such as immune cells, cancer‐associated fibroblasts, and so forth [28, 29]. In the current study, we evaluated the promoting roles between tumor cells through the secretion of IL8. Nude mice were maintained to evaluate the in vivo effect of NFAT5 on tumor growth.

To our knowledge, the correlation between NFAT5 and NF‐κB had not yet been established for lung cancer. Since NFAT5 shares many structural features with both the NFAT and NF‐κB families of transcription factors, NFAT5 and NF‐κB pathways may cross‐regulate gene expression in certain cellular contexts [10]. Thus, as a unique transcription factor, NFAT5 may regulate not only the osmoprotective genes but also certain cytokine genes. Although it has been reported that NFAT5 may interact with p65 by immunoprecipitation [30], most studies suggested that NFAT5 can exert its activity as a transcription factor with independent functions but not just as an enhanceosome. Eight years ago, it was reported that NFAT5 served an important pathophysiological role in seawater inhalation‐induced acute lung injury by modulating NF‐κB activity. In the model of seawater inhalation‐induced acute lung injury, IL8 was markedly reduced when the expression of NFAT5 was reduced using a siRNA [31]. In the year 2024, it was reported that macrophages can induce cisplatin resistance and migration of cancer cells by increasing NFAT5 expression in cancer cells and enhancing NF‐κB signaling [32]. Thus, in the current study, we checked for a potential cross‐talk between NFAT5 and NF‐κB which was linked by IL8. As shown in this study, elevated secretion of IL8 increases the motility of NSCLC cells by activating the NF‐κB signaling pathway. As is well known, the expression of IL8 in certain cells can be modulated by NFκB [33, 34, 35]. Therefore, we can conclude that IL8 expression and secretion can be cross‐regulated by NFAT5 and NF‐κB in certain cellular contexts.

Cytokines such as IL8 and IL1β play an important role in cancer development and treatment response. However, IL8, which is in a complex regulatory network, is regulated by multiple factors and can be secreted by many sources. In lung cancer models, miR‐596‐3p exerts a critical role in brain metastasis by modulating the YAP1‐IL8 network [36]. In another study, IL‐8 production was dependent on NF‐κB, MEK/ERK MAP Kinases, activator protein‐1, or YY1 [12, 13, 37]. Besides cancer cells, IL‐8 can also be secreted by other cells such as macrophages and cancer‐associated fibroblasts [11, 38, 39]. Given such complex regulatory mechanisms and multiple cell sources, IL8 may not be a good therapeutic target. In 2024, canakinumab, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin‐1β, has not shown a DFS benefit in Patients With Completely Resected Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer [40]. Similarly, monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin‐8 have a long way to go for translating to clinical practice. With the advent of the era of immune checkpoints, bispecific antibody may bring a glimmer of light to the treatment of cancer [41].

In the current study, we try to inhibit the proliferation and migration of tumor by down‐regulating NFAT5. But so far, there is no specific inhibitor of NFAT5 available. As shown in this study, NFAT5 is located downstream of intracellular information transmission. Thus, the inhibitory effect targeting NFAT5 could be easily eliminated by intra or extra cancer cell crosstalk. Since the production of NFAT5 requires a lot of ATPs, metformin was added in animal models to evaluate the possible effect on NFAT5 from the energy dimension. However, no statistically significant difference was found between the NC group and metformin treatment group for NFAT5 expression. We speculate that NFAT5 contributes to meaning in expository studies but is insignificant in intervention studies. With the great progress of tumor treatment brought by immunotherapy, research on NFAT5 will not be limited by osmotic stress, nor limited to a single type of cells. Studies about NFAT5 will emphasize its roles in the microenvironment, esp. in relationships between tumor cells and immune cells.

In summary, we showed that NFAT5 could promote cell growth and motility by regulating IL8 directly in NSCLC cell lines. Elevated IL8 expression caused enhancing NF‐κB signaling pathway partially through autocrine or paracrine effects. These findings provide a subtle mechanism of the inflammatory environment on lung cancer progression.

Author Contributions

Jinliang Chen conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Ting Mei conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. Jingya Wang and Tingting Qin analyzed the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. Dingzhi Huang conceptualized, funded, and supervised the project. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Chen J., Mei T., Wang J., Qin T., and Huang D., “ NFAT5 Regulates IL8 to Promote Cell Growth and Migration in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Thoracic Cancer 16, no. 21 (2025): e70166, 10.1111/1759-7714.70166.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Jinliang Chen and Ting Mei contributed equally to this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Fuchs H. E., and Jemal A., “Cancer Statistics, 2021,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 7 (2021): 7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zarogoulidis P., Katsikogianni F., Tsiouda T., Sakkas A., Katsikogiannis N., and Zarogoulidis K., “Interleukin‐8 and Interleukin‐17 for Cancer,” Cancer Investigation 32, no. 5 (2014): 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shou J., Jing J., Xie J., et al., “Nuclear Factor of Activated T Cells in Cancer Development and Treatment,” Cancer Letters 361 (2015): 174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cho H. J., Yun H. J., Yang H. C., et al., “Prognostic Significance of Nuclear Factor of Activated T‐Cells 5 Expression in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Who Underwent Surgical Resection,” Journal of Surgical Research 226 (2018): 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Y., Mi Y., and He C., “2‐Methoxyestradiol Restrains Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Tumorigenesis Through Regulating circ_0010235/miR‐34a‐5p/NFAT5 Axis,” Thoracic Cancer 14 (2023): 2105–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu J., Wang H., Shi B., et al., “Exosomal MFI2‐AS1 Sponge miR‐107 Promotes Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression Through NFAT5,” Cancer Cell International 23 (2023): 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen M., Sastry S. K., and O'Connor K. L., “Src Kinase Pathway Is Involved in NFAT5‐Mediated S100A4 Induction by Hyperosmotic Stress in Colon Cancer Cells,” American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology 300 (2011): C1155–C1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo K. and Jin F., “NFAT5 Promotes Proliferation and Migration of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells in Part Through Regulating AQP5 Expression,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 465 (2015): 644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mijatovic T., Mathieu V., Gaussin J. F., et al., “Cardenolide‐Induced Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization Demonstrates Therapeutic Benefits in Experimental Human Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancers,” Neoplasia 8 (2006): 402–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stroud J. C., Lopez‐Rodriguez C., Rao A., and Chen L., “Structure of a TonEBP‐DNA Complex Reveals DNA Encircled by a Transcription Factor,” Nature Structural Biology 9 (2002): 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gu X., Zhu Y., Su J., et al., “Lactate‐Induced Activation of Tumor‐Associated Fibroblasts and IL‐8‐Mediated Macrophage Recruitment Promote Lung Cancer Progression,” Redox Biology 74 (2024): 103209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jin H., Liu C., Liu X., et al., “Huaier Suppresses Cisplatin Resistance in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer by Inhibiting the JNK/JUN/IL‐8 Signaling Pathway,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 319 (2024): 117270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu W. J., Wang L., Zhou F. M., et al., “Elevated NOX4 Promotes Tumorigenesis and Acquired EGFR‐TKIs Resistance via Enhancing IL‐8/PD‐L1 Signaling in NSCLC,” Drug Resistance Updates 70 (2023): 100987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fong Y. C., Maa M. C., Tsai F. J., et al., “Osteoblast‐Derived TGF‐beta1 Stimulates IL‐8 Release Through AP‐1 and NF‐kappaB in Human Cancer Cells,” Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 23 (2008): 961–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feng W., Xue T., Huang S., et al., “HIF‐1α Promotes the Migration and Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via the IL‐8‐NF‐κB Axis,” Cellular and Molecular Biology Letters 23 (2018): 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhai J., Shen J., Xie G., et al., “Cancer‐Associated Fibroblasts‐Derived IL‐8 Mediates Resistance to Cisplatin in Human Gastric Cancer,” Cancer Letters 454 (2019): 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang W., Zhang L., Yang M., et al., “Cancer‐Associated Fibroblasts Promote the Survival of Irradiated Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells via the NF‐κB Pathway,” Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 40 (2021): 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Villalta P. C., Rocic P., and Townsley M. I., “Role of MMP2 and MMP9 in TRPV4‐Induced Lung Injury,” American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 307 (2014): L652–L659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou P., Song N. C., Zheng Z. K., Li Y. Q., and Li J. S., “MMP2 and MMP9 Contribute to Lung Ischemia‐Reperfusion Injury via Promoting Pyroptosis in Mice,” BMC Pulmonary Medicine 22 (2022): 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ratajczak‐Wielgomas K., Kmiecik A., and Dziegiel P., “Role of Periostin Expression in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer: Periostin Silencing Inhibits the Migration and Invasion of Lung Cancer Cells via Regulation of MMP‐2 Expression,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (2022): 1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun J., Hu J. R., Liu C. F., et al., “ANKRD49 Promotes the Metastasis of NSCLC via Activating JNK‐ATF2/c‐Jun‐MMP‐2/9 Axis,” BMC Cancer 23 (2023): 1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang X., Tan Q., Xu J., et al., “Tumor‐Derived Exosomal linc00881 Induces Lung Fibroblast Activation and Promotes Osteosarcoma Lung Migration,” Cancer Cell International 23 (2023): 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q., Chen M., and Tang X., “Luteolin Inhibits Lung Cancer Cell Migration by Negatively Regulating TWIST1 and MMP2 Through Upregulation of miR‐106a‐5p,” Integrative Cancer Therapies 23 (2024): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laban H., Siegmund S., Schlereth K., et al., “Nuclear Factor of Activated T‐Cells 5 Is Indispensable for a Balanced Adaptive Transcriptional Response of Lung Endothelial Cells to Hypoxia,” Cardiovascular Research 120 (2024): 1590–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meng X., Li Z., Zhou S., Xiao S., and Yu P., “miR‐194 Suppresses High Glucose‐Induced Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Progression by Targeting NFAT5,” Thoracic Cancer 10, no. 5 (2019): 1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang M., Ke H., and Zhou W., “LncRNA RMRP Promotes Cell Proliferation and Invasion Through miR‐613/NFAT5 Axis in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Oncotargets and Therapy 13 (2020): 8941–8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tong Z., Wang Z., Jiang J., Tong C., and Wu L., “A Novel Molecular Mechanism Mediated by circCCDC134 Regulates Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression,” Thoracic Cancer 14 (2023): 1958–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fan G., Yu B., Tang L., et al., “TSPAN8(+) Myofibroblastic Cancer‐Associated Fibroblasts Promote Chemoresistance in Patients With Breast Cancer,” Science Translational Medicine 16 (2024): eadj5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lou M., Iwatsuki M., Wu X., Zhang W., Matsumoto C., and Baba H., “Cancer‐Associated Fibroblast‐Derived IL‐8 Upregulates PD‐L1 Expression in Gastric Cancer Through the NF‐κB Pathway,” Annals of Surgical Oncology 31 (2024): 2983–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee H. H., Sanada S., An S. M., et al., “LPS‐Induced NFκB Enhanceosome Requires TonEBP/NFAT5 Without DNA Binding,” Scientific Reports 6 (2016): 24921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li C., Liu M., Bo L., et al., “NFAT5 Participates in Seawater Inhalation‐Induced Acute Lung Injury via Modulation of NF‐κB Activity,” Molecular Medicine Reports 14 (2016): 5033–5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Song H. J., Kim Y. H., Choi H. N., et al., “TonEBP/NFAT5 Expression Is Associated With Cisplatin Resistance and Migration in Macrophage‐Induced A549 Cells,” BMC Molecular and Cell Biology 25 (2024): 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yin Y., Dai H., Sun X., et al., “HRG Inhibits Liver Cancer Lung Metastasis by Suppressing Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation,” Clinical and Translational Medicine 13 (2023): e1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fariña E., Daghero H., Bollati‐Fogolín M., et al., “Antioxidant Capacity and NF‐kB‐Mediated Anti‐Inflammatory Activity of Six Red Uruguayan Grape Pomaces,” Molecules 28 (2023): 3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guan X., Ning J., Fu W., Wang Y., Zhang J., and Ding S., “Helicobacter Pylori With trx1 High Expression Promotes Gastric Diseases via Upregulating the IL23A/NF‐κB/IL8 Pathway,” Helicobacter 29 (2024): e13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li C., Zheng H., Xiong J., et al., “miR‐596‐3p Suppresses Brain Metastasis of Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer by Modulating YAP1 and IL‐8,” Cell Death & Disease 13 (2022): 699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao M. N., Zhang L. F., Sun Z., et al., “A Novel microRNA‐182/Interleukin‐8 Regulatory Axis Controls Osteolytic Bone Metastasis of Lung Cancer,” Cell Death & Disease 14 (2023): 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quero L., Tiaden A. N., Hanser E., et al., “miR‐221‐3p Drives the Shift of M2‐Macrophages to a Pro‐Inflammatory Function by Suppressing JAK3/STAT3 Activation,” Frontiers in Immunology 10 (2019): 3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu J., Zhang Q., Wu J., et al., “IL‐8 From CD248‐Expressing Cancer‐Associated Fibroblasts Generates Cisplatin Resistance in Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 28 (2024): e18185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garon E. B., Lu S., Goto Y., et al., “Canakinumab as Adjuvant Therapy in Patients With Completely Resected Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer: Results From the CANOPY‐A Double‐Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 42 (2024): 180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Piper M., Hoen M., Darragh L. B., et al., “Simultaneous Targeting of PD‐1 and IL‐2Rβγ With Radiation Therapy Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Growth and Metastasis,” Cancer Cell 41 (2023): 950–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.