Abstract

We show here that CD40 mRNA and protein are expressed by neuronal cells, and are increased in differentiated versus undifferentiated N2a and PC12 cells as measured by RT–PCR, western blotting and immunofluorescence staining. Additionally, immunohistochemistry reveals that neurons from adult mouse and human brain also express CD40 in situ. CD40 ligation results in a time-dependent increase in p44/42 MAPK activation in neuronal cells. Furthermore, ligation of CD40 opposes JNK phosphorylation and activity induced by NGF-β removal from differentiated PC12 cells or serum withdrawal from primary cultured neurons. Importantly, CD40 ligation also protects neuronal cells from NGF-β or serum withdrawal-induced injury and affects neuronal differentiation. Finally, adult mice deficient for the CD40 receptor demonstrate neuronal dysfunction as evidenced by decreased neurofilament isoforms, reduced Bcl-xL:Bax ratio, neuronal morphological change, increased DNA fragmentation, and gross brain abnormality. These changes occur with age, and are clearly evident at 16 months. Taken together, these data demonstrate a role of CD40 in neuronal development, maintenance and protection in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: apoptosis/CD40L/JNK/MAPK/neuron

Introduction

CD40 receptor (CD40) is a 45–50 kDa receptor that is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily, other members of which include TNFRI and II, and the low affinity p75 nerve growth factor (NGF) receptor (Grimaldi et al., 1992; Torres and Clark, 1992). Interaction of CD40 with its ligand, CD40 ligand (CD40L), has been shown to play a crucial role in cellular and humoral immune responses. For example, CD40 promotes priming of T-helper type I cells, and interaction between T-cell CD40L and B-cell CD40 results in B-cell proliferation and differentiation into antibody-secreting plasma cells (Xu et al., 1994; Foy et al., 1996). Additionally, we have shown that ligation of microglial CD40 leads to microglial activation as evidenced by TNF-α production and bystander neuronal injury (Tan et al., 1999). Initially, the CD40 receptor was thought to mediate immune cell signaling exclusively, as it was found to be expressed on a wide range of immune cells including monocytes, tissue macrophages, B cells and dendritic cells (van Kooten, 2000). Yet, CD40 has subsequently been localized to other cell types including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and, most recently, human cultured myoblasts (Mach et al., 1997; Brouty-Boye et al., 2000; Sugiura et al., 2000). Such evidence of CD40 expression on non-immune cell types suggests a broader role of CD40 in cellular biology.

Stimulation of CD40 by agonistic antibodies or via CD40L has been shown to promote proliferation, survival, differentiation and maturation in a variety of immune cells. For example, in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells, CD40L treatment results in proliferation and promotes long-term maintenance of these cells in vitro (Zhou et al., 2000). Additionally, ligation of B-cell CD40 promotes proliferation, survival and isotype switching in these cells, effects that are further regulated in an antagonistic manner by the T-helper type I cytokine IFN-γ and the T-helper type II cytokine IL-4 (Kilger et al., 1998; Hasbold et al., 1999). Similar effects of CD40 stimulation on promotion of proliferation and differentiation have also been shown in human keratinocytes, where ligation of CD40 brings about mitogenesis, secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increased profilaggrin (a marker of differentiation) content (Peguet-Navarro et al., 1997). Additionally, microglial cells, when exposed to CD40L, enter into the terminal maturation program (Fischer and Reichmann, 2001). Perhaps the most notable effects of CD40 stimulation on cellular differentiation and maturation are evidenced in dendritic cell studies. For instance, Flores-Romo and colleagues (1997) found that ligation of CD40 induced human cord-blood hematopoeitic progenitors to proliferate and differentiate into functional, mature dendritic cells. These cells were able to prime allogeneic naïve T cells independently of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (Flores-Romo et al., 1997), previously recognized as a requirement for promotion of dendritic cell proliferation, survival and maturation (Markowicz and Engleman, 1990).

Neuronal cells express a number of TNFR superfamily members, including p75 NGF receptor, and TNFRI and II (Chao, 1994; Botchkina et al., 1997). The functional repertoire of these other TNFR superfamily members on neurons includes processes modulated by CD40 in immune cells, such as regulation of differentiation and survival (Xu et al., 1994; Foy et al., 1996). However, CD40 expression on neurons has not yet been reported. We have now investigated CD40 expression on neuronal cells and demonstrate its expression and functionality on the surface of cultured neurons and neuron-like cells.

Results

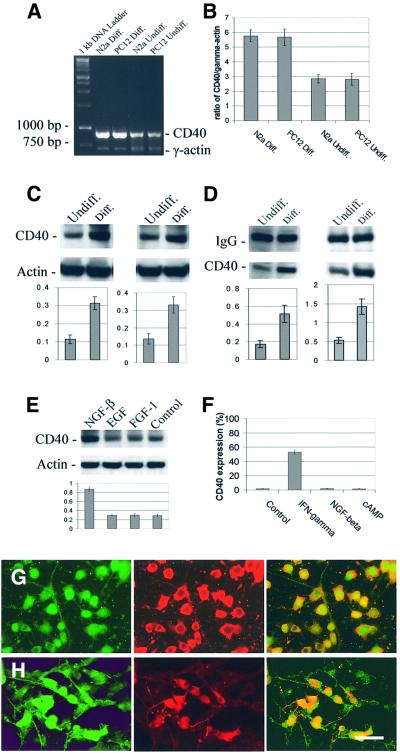

CD40 is constitutively expressed on neuron-like cells and neurons

In order to investigate whether CD40 might be expressed in cultured neuron-like cells, we first isolated total RNA from N2a or PC12 cells, either undifferentiated or differentiated into cells that morphologically and biochemically resemble neurons (Olmsted et al., 1970; Greene and Tischler, 1976), for reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analysis. Results show that CD40 mRNA is detected in both of these cell lines, and, most importantly, is increased in differentiated N2a and PC12 cells compared with undifferentiated cells (Figure 1A and B). Further, as shown in Figure 1C and D, CD40 protein is detected in N2a and PC12 cells and is markedly increased following differentiation. To test whether these effects were specific to NGF-β-induced neuronal differentiation as opposed to growth factors that do not promote neuronal differentiation, we treated PC12 cells with two other growth factors that are inefficient at promoting neuronal differentiation, endothelial growth factor (EGF) or fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-1, for the same time course (48 h). These growth factors do not affect CD40 expression (Figure 1E). We also treated CD40-expressing non-neuronal cells (microglial cells) with IFN-γ (a robust promoter of CD40 expression on microglia) (Tan et al., 1999), NGF-β or cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) for 48 h. Neither cAMP nor NGF-β is able to increase CD40 expression on microglia (Figure 1F). Finally, to evaluate further whether neuronal CD40 expression might be detectable on neuron-like cells in situ, we performed immunofluorescence staining on cultured N2a and PC12 cells. CD40 expression is clearly observable on neurofilament-positive differentiated N2a and PC12 cells, and is localized to the soma and, more weakly, the neurites (Figure 1G and H). CD40 is almost undetectable on undifferentiated N2a or PC12 cells using this method (data not shown).

Fig. 1. CD40 is expressed by neuron-like cells. (A) RT–PCR analysis of N2a and PC12 cells prior to (Undiff.) and after differentiation (Diff.) into neuron-like cells. (B) Histogram representing the ratio of CD40 signal to γ-actin [mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (SEM)], with n = 3 for each condition presented. Significant differences were noted between differentiated and undifferentiated N2a cells (p = 0.001), and between differentiated and undifferentiated PC12 cells (p <0.01). (C and D) CD40 protein expression by western blotting (C) and immunoprecipitation (D). Graph below immunoblots represents band density ratio (mean ± 1 SEM) of CD40 to actin (C) or CD40 to IgG (D), with n = 3 for each condition presented. N2a cells prior to and after differentiation are shown in (C) and (D) (left), and PC12 cells before and after differentiation are shown in (C) and (D) (right). Significant differences were found between undifferentiated and differentiated N2a and PC12 cells for (C) and (D) (p <0.01). (E) Western blot showing CD40 expression in PC12 cells that were treated with NGF-β, EGF or FGF-1, or went untreated (control) for 48 h. Graph below immunoblot represents band density ratio (mean ± 1 SEM) of CD40 to actin, with n = 3 for each condition presented. Only following NGF-β treatment is PC12 cell CD40 expression increased(p <0.001). (F) Flow analysis of CD40 expression on microglial cells that were treated with IFN-γ, NGF-β or cAMP, or went untreated (control) for 48 h. Data shown represent mean CD40 expression values (%) ± 1 SEM, with n = 3 for each group. Only after IFN-γ treatment do microglia upregulate CD40 (p <0.001). (G and H) Differentiated N2a cells (G) and PC12 cells (H) were doubly labeled with fluorescent antibodies that recognize neurofilament and CD40. (G and H) Left: CD40 (green) is detected by FITC-conjugated anti-CD40 antibody; middle: neurofilament (red) is detected by TRITC-conjugated anti-neurofilament (70 kDa) antibody; right: CD40 and neurofilament are co-localized as indicated by overlapping green and red signals (yielding a yellow signal). Bar denotes 50 µm (calculated for each panel).

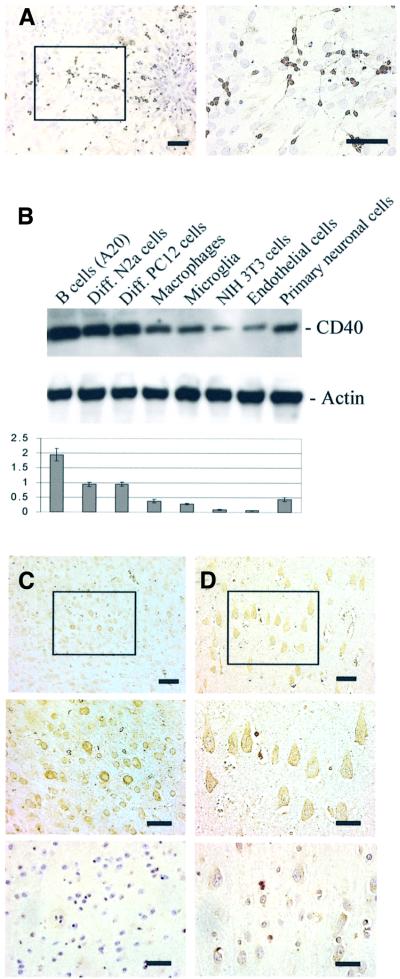

Having shown that cultured neuron-like cells express CD40, we wished to evaluate further whether primary cultured murine neurons might also express CD40. Having detected CD40 mRNA in these cells (data not shown), we performed immunocytochemistry for the detection of CD40 receptor on these cells. Similar to the data obtained for differentiated N2a or PC12 cells, neuronal cells express CD40 primarily on the cell body and, at a lower level, on neuronal processes (Figure 2A). CD40 has been reported to be expressed by a wide range of cell types, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, B lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages and microglia (Carson et al., 1998; Tan et al., 1999; Brouty-Boye et al., 2000). To compare expression levels of neuronal CD40 with these other cell types, we examined CD40 expression in a variety of cell types by western blotting. Expression levels in neuronal cells are lower than B cells (A20), but significantly higher than in endothelial cells and fibroblasts (NIH 3T3 cells) (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. CD40 expression in situ on neurons. (A) Immunocytochemistry was performed on murine primary cultured neuronal cells (left, bar represents 10 µm; right, bar represents 20 µm). Neurons are clearly positive for CD40 (brown). (B) Western blot analysis (top) of total protein prepared from neuron-like cells, primary cultured neurons and other cell types known to express CD40. Graph represents band density ratio of CD40 to actin (mean ± 1 SEM), with n = 3 for each condition presented. Results shown in (B) reveal that neuron-like cells and primary cultured neurons express CD40 at similar levels to microglia or macrophages, and at a relatively higher level than endothelial cells (p <0.01) or fibroblasts (NIH 3T3; p <0.01). (C) Immunohistochemistry was performed on vibratome sections of normal mouse (top and middle) or CD40-deficient mouse (bottom) brain temporal cortices [(8 months of age; n = 4 for each group (two males, two females)]. Bars denote 50, 30 and 30 µm for the top, middle and bottom, respectively. (D) Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections of human temporal cortex in the absence (top and middle) or presence (bottom) of CD40 blocking peptide [(64 ± 5 years of age; n = 3 (two males, one female)]. Bars denote 30, 15 and 15 µm for the top, middle and bottom, respectively. CD40 positive cells (brown) are neurons. Similar observations were made for each mouse or human brain section observed.

While CD40 is clearly detectable in adult mouse and human brain tissue homogenates using western blotting (data not shown), such analyses do not offer insight into which brain cells express CD40. Thus, we performed immunohistochemistry on adult mouse and human brain, and find that adult mouse (Figure 2C, top and middle) and human (Figure 2D, top and middle) cortical neurons stain positively for CD40. Neuronal CD40 expression is not ubiquitous in mouse or in human brain, but rather seems to be predominately expressed by most of the neurons in the dentate gyrus and hippocampus (particularly the pyramidal cell layer) and on ∼60% of cortical neurons. To rule out the possibility that neuronal cells non-specifically bound anti-CD40 antibody, two additional experiments were performed: we stained brains from CD40-deficient mice with anti-CD40 antibody, and we pre-absorbed the anti-human CD40 antibody with human CD40 blocking peptide. CD40 signal is undetectable in CD40-deficient mice (Figure 2C, bottom) and is markedly reduced in human brain when the blocking peptide is employed (Figure 2D, bottom).

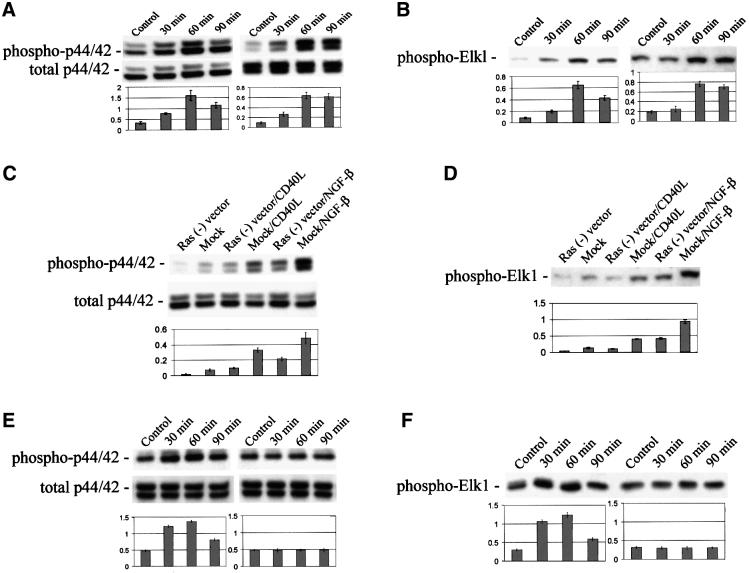

Ligation of CD40 stimulates p44/42 MAPK in cultured neuronal cells

We and others have shown that ligation of CD40 on microglia and B cells results in activation of p44/42 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and stress-activated protein kinases (Berberich et al., 1996; Tan et al., 2000). Thus, to evaluate the functionality of CD40 on neuron-like cells, we incubated N2a or PC12 cells with human recombinant CD40L at various time points (from 30 to 90 min) and measured p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation and activity by western blotting and immune complex kinase assay, respectively. Data show that CD40 ligation results in increased p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation in N2a (Figure 3A, left) and PC12 cells (Figure 3A, right), which plateaued at 60 min post-treatment. Analysis of p44/42 MAPK activity shows a similar pattern of results in N2a (Figure 3B, left) and PC12 cells (Figure 3B, right). It has been reported that the Ras signaling pathway is activated in B lymphocytes by CD40 receptor engagement (Gulbins et al., 1996). In addition, activation of the Ras-MAPK cascade plays a central role in NGF-β-induced PC12 cell differentiation (Thomas et al., 1992) and has been shown to oppose neuronal death following loss of trophic factor support in PC12 cells (Yan and Greene, 1998). To determine if CD40L-mediated p44/42 MAPK activation might be Ras-dependent, we transfected PC12 cells with a Ras dominant-negative vector and ligated CD40. Results show that CD40L-mediated phosphorylation (Figure 3C) and activity (Figure 3D) of p44/42 MAPK are significantly reduced in this condition, indicating that Ras is critically involved in CD40L-induced p44/42 MAPK activation.

Fig. 3. Ligation of CD40 on neuronal cells results in activation of p44/42 MAPK. (A) Western blot (top) shows phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK in cultured N2a (left) or PC12 cells (right) that were treated with CD40L for 30, 60 or 90 min, or went untreated (control) for 60 min, as indicated. Graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of phospho-p42:total p42 for the above, with n = 3 for each condition presented. Significant differences were noted when comparing control with 30 min CD40L treatment (p <0.05), or 60 or 90 min CD40L treatment (p <0.001). (B) Immune complex kinase assay (top) shows phosphorylation of the MAPK fusion protein, Elk1, in cultured N2a (left) or PC12 (right) cells that were treated as described in (A). Graph (bottom) summarizes band densities (mean ± 1 SEM) for the above, with n = 3 for each condition presented. Significant differences were found when comparing control with 30 min CD40L treatment (p <0.05), or 60 or 90 min CD40L treatment (p <0.001). (C) Western blotting (top) shows phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK in PC12 cells transfected with a pcDNA3 vector containing a Ras dominant-negative construct [Ras (–) vector] or pcDNA3 vector alone (Mock) that went untreated (control) or were treated with CD40L protein or NGF-β for 60 min. Graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of phospho-p42:total p42 for the above with n = 3 for each condition presented. (D) Immune complex kinase assay (top) shows phosphorylation of the MAPK fusion protein, Elk1, in transfected PC12 cells, according to treatment conditions described in (C). Graph (bottom) summarizes band densities (mean ± SEM) for the above, with n = 3 for each condition presented. A significant difference was noted when comparing CD40L-treated PC12 cells transfected with Ras (–) vector to CD40 ligated mock vector-transfected PC12 cells (p <0.001). A significant difference was also found between NGF-β-treated Ras (–) vector-transfected PC12 cells and mock vector-transfected PC12 cells that also received NGF-β treatment (p < 0.001). (E) Western blotting (top) shows phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK in murine primary cultured neuronal cells derived from wild-type (left) or CD40-deficient (right) mice that were treated with CD40L protein for 30, 60 or 90 min, or went untreated (control) for 60 min as indicated. Graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of phospho-p42:total p42 for the above with n = 3 for each condition presented. (F) Immune complex kinase assay (top) shows phosphorylation of the MAPK fusion protein, Elk1, in wild-type (left) or CD40-deficient (right) mouse-derived neuronal cells that were treated as described in (E). Graph (bottom) summarizes band densities (mean ± 1 SEM) for the above with n = 3 for each condition presented. For (E and F, left), significant differences were found when comparing control with 30 min CD40L treatment (p <0.05), or 60 or 90 min CD40L treatment (p <0.001). For (E and F, right), no significant differences were noted when comparing control with 30, 60 or 90 min CD40L treatment of CD40-deficient mice (p >0.05).

In order to evaluate further CD40-induced MAPK pathway activation, we ligated murine wild-type primary cultured neuronal cells with CD40L at various time points (30, 60 and 90 min as above). We then examined phosphorylation and activity of p44/42 MAPK. CD40 ligation results in increased p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 3E, left) and activity (Figure 3F, left) in these cells, again plateauing at 60 min post-treatment. To evaluate whether these effects were specific to the CD40–CD40L interaction, we ligated CD40 and determined p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation and activity in primary cultures of neurons derived from CD40-deficient mice. Data show that CD40L is unable to elicit p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 3E, right) or activity (Figure 3F, right) in CD40-deficient neurons.

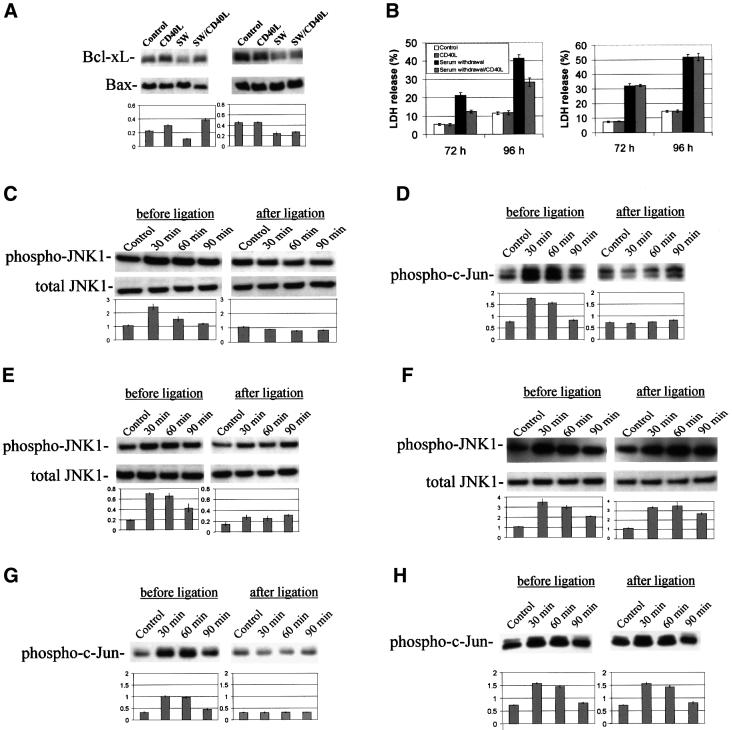

Ligation of CD40 in cultured neuronal cells rescues injury induced by serum withdrawal

Previous studies have shown that stimulation of CD40 with agonistic antibodies inhibits apoptosis in B cells (Lee et al., 1999; Andjelic et al., 2000). These data led us to investigate whether ligation of CD40 could rescue cell death induced by serum withdrawal in primary cultured neuronal cells. Thus, we treated wild-type (Figure 4A, left) or CD40-deficient (Figure 4A, right) neuronal cells with CD40L in the presence or absence of serum and prepared cell lysates 12 h later to examine the ratio of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL to pro-apoptotic Bax by western blotting (Boise et al., 1993; Schendel et al., 1998). Additionally, we collected cell culture media 72 and 96 h after incubation for the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. In addition to mitigating decreased Bcl-xL:Bax ratio, data show that ligation of CD40 markedly reduces neuronal cell injury induced by serum withdrawal in wild-type (Figure 4B, left), but not CD40-deficient (Figure 4B, right) neurons. Similar results were observed in differentiated PC12 cells after NGF-β withdrawal (data not shown).

Fig. 4. CD40 ligation rescues neuronal cell injury and inhibits JNK activation induced by NGF-β or serum withdrawal. (A) Western blotting (top) shows expression of Bcl-xL and Bax in wild-type (left) or CD40-deficient (right) primary cultured neurons that were incubated with serum (control) or were subjected to serum withdrawal (SW) in the presence or absence of CD40L for 12 h. Graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios of Bcl-xL:Bax (mean ± 1 SEM) for the above, with n = 3 for each condition presented. (A, left) Significant differences were noted between incubation of serum (control) in the presence or absence of CD40L (p <0.05), as well as between cells subjected to SW in the presence or absence of CD40L (p <0.001). (A, right) No significant between-group differences were found (p >0.05). (B) LDH release assay (mean ± 1 SEM, n = 3 for each condition presented) shows that CD40 ligation significantly (p <0.001) reduces LDH release in primary neuronal cells at 72 and 96 h post-withdrawal of serum (left), but no CD40L effect was noted in CD40-deficient primary neurons (right) (p >0.05). (C) Western blotting (top) shows phosphorylated JNK1 (p46) in differentiated PC12 cells after NGF-β withdrawal in the presence (right) or absence (left) of CD40L for 30, 60 or 90 min as indicated. Graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of phospho-JNK1:total JNK1 for the above with n = 3 for each condition presented. Significant differences were found when comparing ‘before’ with ‘after’ CD40L ligation at 30 or 60 min (p <0.01). (D) Immune complex kinase assay (top) shows phosphorylation of c-Jun fusion protein before (left) or after (right) CD40 ligation of differentiated PC12 cells, which were treated as described in (C). Graph (bottom) summarizes band densities (mean ± 1 SEM) for the above, with n = 3 for each condition presented. Significant differences were found when comparing ‘before’ with ‘after’ CD40L ligation at 30 or 60 min (p <0.001). (E and F) Western blotting (top) shows phosphorylated JNK1 (p46) in wild-type (E) or CD40 deficient (F) primary neuronal cells after serum withdrawal in the presence (right) or absence (left) of CD40L for the time points indicated. Graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of phospho-JNK1:total JNK1 for the above with n = 3 for each condition presented. For (E), significant differences were found when comparing ‘before’ with ‘after’ CD40L ligation at each time point (p <0.05). For (F), no significant between-groups differences were found (p >0.05). (G and H) Immune complex kinase assay (top) shows phosphorylation of c-Jun fusion protein before (left) or after (right) CD40 ligation of wild-type (G) or CD40-deficient (H) primary neurons that were treated as described in (E and F). Graph (bottom) summarizes band densities (mean ± 1 SEM) for the above, with n = 3 for each condition presented. For (G), significant differences were found when comparing ‘before’ with ‘after’ CD40L ligation at 30 or 60 min (p <0.01). For (H), no significant between-groups differences were noted (p >0.05).

CD40 ligation inhibits JNK activation in cultured neuronal cells following NGF-β or serum withdrawal

It is well known that the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway is involved in regulation of cell death and survival, and it has been demonstrated that JNK lies on the signaling pathway activated in neurotrophin withdrawal-mediated apoptosis (Bruckner et al., 2001; Eilers et al., 2001). Further, it has been shown that stimulation of the CD40–CD40L pathway differentially activates TNFR-associated factors, thereby modulating JNK activation in B cells (Leo et al., 1999). These data led us to ask whether CD40 ligation could modulate JNK activation in differentiated PC12 cells or primary cultured neuronal cells following NGF-β or serum withdrawal, respectively. We first subjected differentiated PC12 cells to NGF-β withdrawal and examined JNK phosphorylation and activity (c-Jun phosphorylation) by western blotting at 30, 60 and 90 min. Results show that CD40 ligation markedly inhibits JNK phosphorylation (Figure 4C) and activity (Figure 4D) induced by NGF-β withdrawal in differentiated PC12 cells across this time course. To validate this effect, we treated primary cultured neuronal cells with CD40L following serum withdrawal at the same time points and observe similar results (Figure 4E and G). Finally, to address whether the CD40–CD40L interaction specifically mediated these effects, we made primary cultures of neurons from CD40-deficient mice and treated them in a similar manner. In these cells, addition of CD40L is unable to inhibit either serum withdrawal-mediated phosphorylation of JNK (Figure 4F) or c-Jun phosphorylation (Figure 4H).

CD40 ligation promotes differentiation of PC12 cells into the neuronal phenotype

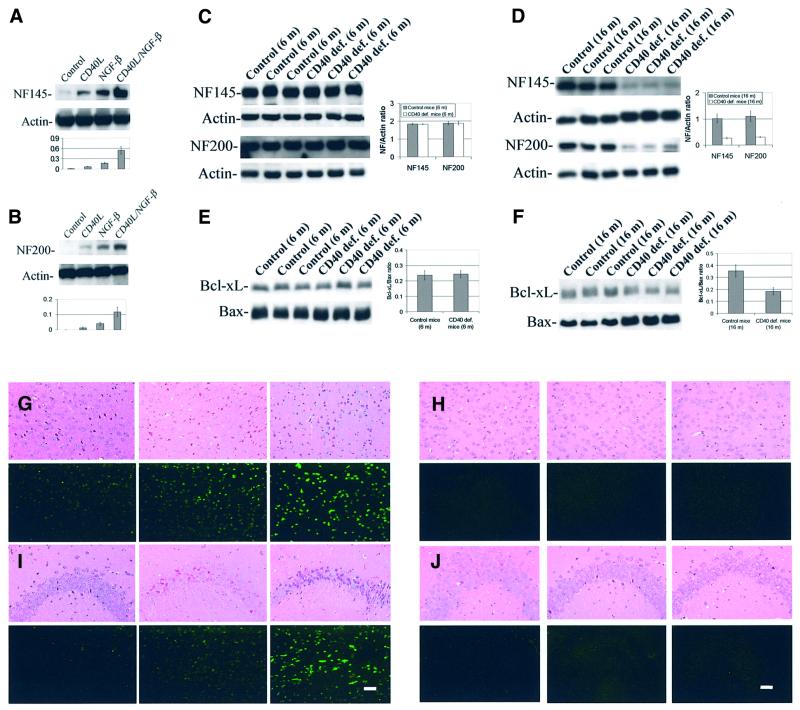

It has previously been shown that the p44/42 MAPK pathway is critically involved in NGF-β-induced differentiation of PC12 cells (Gomez and Cohen, 1991). Having shown that ligation of neuronal CD40 leads to increased phosphorylation and activity of p44/42 MAPK, we wished to evaluate the possibility that CD40 ligation might promote differentiation of PC12 cells into the neuronal phenotype. Thus, we treated undifferentiated PC12 cells with CD40L in the presence or absence of a sub-optimal dose of NGF-β (5 ng/ml) and measured neurofilament expression in these cells as a marker of neuronal differentiation. Results show that CD40 ligation significantly increases expression of the 145 and 200 kDa (Figure 5A and B) neurofilament isoforms. Additionally, when PC12 cells are co-treated with CD40L and NGF-β, neurofilament expression is synergistically enhanced (Figure 5A and B).

Fig. 5. CD40L promotes neuronal differentiation and opposes neuronal dysfunction. (A and B) Western blotting (above) shows increased 145 kDa (A) and 200 kDa (B) neurofilament (NF) isoforms in PC12 cells that were treated with CD40L and a sub-optimal dose of NGF-β (5 ng/ml), alone or in combination, or went untreated (control) for 72 h as indicated. The graph (bottom) summarizes band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of neurofilament to actin for the above with n = 4 for each condition presented. For (A and B), significant treatment effects were noted for CD40L (p ≤0.001) and NGF-β (p <0.001), and most importantly, a synergistic effect of co-treatment (p ≤0.01). (C and D) Western blotting shows the expression of neurofilament 145 kDa (top) and 200 kDa (bottom) isoforms from CD40-deficient or strain-matched control mouse brain homogenates at age 6 (C) or 16 months (D). (C and D, right) Graph summarizing band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of neurofilament to actin, with n = 6 (CD40 deficient) or n = 3 (control). For (C), no significant between-groups differences were noted for either neurofilament isoform (p >0.05). For (D), significant between-group difference was noted for both neurofilament isoforms (p = 0.001). (E and F) Western blotting shows the expression of Bcl-xL (top) and Bax (bottom) from CD40-deficient or strain-matched control mouse brain homogenates at age 6 (E) or 16 months (F). (E and F, right) Graph summarizing band density ratios (mean ± 1 SEM) of Bcl-xL:Bax with n = 6 (CD40 deficient) or n = 3 (control). For (E), no significant between-groups difference was noted (p >0.05). For (F), a significant difference was noted (p = 0.001). (G–J) Immunohistochemistry (haematoxylin–eosin, upper panels) and TUNEL reaction (lower panels) was performed on paraffin sections from temporal cortices (G and H) and hippocampi (I and J) of CD40-deficient mice at age 6 months (G and I, left; n = 3), 12 months (G and I, middle; n = 6) or 16 months (G and I, right; n = 6), or strain-matched control mice at age 6 months (H and J, left; n = 3), 12 months (H and J, middle; n = 3) or 16 months (H and J, right; n = 3). Haematoxylin–eosin and TUNEL-stained images are from similar regions of adjacent sections in each mouse. Bar = 50 µm.

Neurodegeneration is apparent in adult CD40-deficient mice

It has repeatedly been shown that CD40 plays a role in cellular survival, particularly in B cells and dendritic cells (Koppi et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1999; Andjelic et al., 2000). Our data thus far showed opposition of cell injury after CD40 ligation in cultured neuron-like cells and in neurons. In order to validate these findings in vivo, we examined brains of mice deficient for the CD40 receptor and their strain-matched controls. Decreased neurofilament expression is a marker of neuronal injury (Ray et al., 2000), and at 6 months of age, neurofilament isoform expression levels are similar in CD40-deficient and control mouse brains (Figure 5C). Yet, a different pattern of results is observed at an age of 16 months, where CD40-deficient mice have marked differences in both neurofilament isoforms (Figure 5D). To determine if this decrease in neurofilament expression might be associated with a pro-apoptotic response, we investigated the ratio of Bcl-xL to Bax protein. While this ratio is not significantly changed in brain homogenates from adult CD40-deficient mice at an age of 6 months (Figure 5E), we observe a significant difference between these groups at 16 months of age (Figure 5F). To validate whether neuronal apoptosis was occurring in aged CD40-deficient mice, we examined neuronal morphology after haematoxylin–eosin staining and performed TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) on CD40-deficient mouse brain sections and strain-matched controls at 6, 12 and 16 months of age. Data reveal neuronal morphological change and increased TUNEL reaction in both the neocortex (Figure 5G) and the hippocampus (note the neuron-dense CA1 region; Figure 5I) of mice deficient for the CD40 receptor compared with age- and strain-matched controls (Figure 5H and J). Neuronal dysmorphology and increased TUNEL reaction are primarily localized to the dentate gyrus and pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus, and in focal areas of the neocortex. To determine whether there was evidence for gross brain abnormality in these animals, we weighed their brains and found modest yet significant differences in wet weights of brains from CD40-deficient mice compared with strain-matched controls at 12 and 16 months of age (Table I). Furthermore, we quantified the lateral ventricle area in brain sections taken at similar brain levels (randomly choosing either the right or left ventricle for each brain section). A significant increase in ventricular area is evident in CD40-deficient mice compared with controls by 16 months of age [ventricle area (pixels × 103): 954.61 ± 196.70 versus 517.32 ± 22.10], providing evidence of ventriculomegaly. Taken together, these data suggest that the stress associated with aging elicits injury in vulnerable neurons deficient for CD40.

Table I. Wet mouse brain weight (mg ± 1 SEM).

| Age |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 16 months | |

| Wild-type mice | 486.21 ± 4.72 | 492.89 ± 2.67a | 482.18 ± 4.18a |

| CD40-deficient mice | 488.43 ± 3.76 | 453.13 ± 2.78 | 409.67 ± 4.11 |

ap <0.001 compared with strain- and age-matched controls.

Discussion

It has previously been reported that CD40 is expressed by a wide range of cell types, including B lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and human cultured myoblasts (Mach et al., 1997; Brouty-Boye et al., 2000; Sugiura et al., 2000; van Kooten, 2000). Recently, we and others have additionally shown that microglial cells express CD40 at low levels, and that this expression is markedly increased by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ (Carson et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 1998; Tan et al., 1999). Here, we report that CD40 is constitutively expressed by neurons and neuron-like cells, and CD40 is functional as indicated by activation of Ras-dependent p44/42 MAPK following ligation with CD40L. Under conditions of neuronal stress induced by growth factor withdrawal, we also find that CD40 ligation decreases JNK activation and activity, and mitigates pro-apoptotic response and neuronal demise. Furthermore, ligation of CD40 promotes differentiation into the neuronal phenotype. Finally, adult mice deficient for CD40 demonstrate neuronal cell dysfunction and gross CNS abnormalities with age, suggesting that CD40 signaling on neurons plays a physiological role in normal neuronal cell maintenance and confers resistance to aging-induced stress.

It is well known that CD40 signaling triggers activation of the MAPK cascade, resulting in distinct effects on different cell types. In this study, we show that stimulation of CD40 promotes neuronal differentiation, consistent with the pro-differentiating role of CD40 on B lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Of particular interest is the finding that ligation of neuronal CD40 activates p44/42 MAPK through the Ras pathway. It has previously been shown that expression of Ras family members strongly depends on developmental stage and correlates with neuronal differentiation (Ayala et al., 1989a,b). Additionally, there is evidence that activation of Ras and downstream p44/42 MAPK is a critical determinant of neuritogenesis and neuronal differentiation following stimulation with trophic factors such as brain derived neurotrophic factor and NGF (Zirrgiebel and Lindholm, 1996; Encinas et al., 1999). Thus, the suggestion arises that ligation of neuronal CD40 affects neuronal differentiation by promoting Ras/MAPK signaling.

As our findings suggested that neuronal CD40 might be involved in CNS development, we analyzed brains from wild-type mice at a variety of time points from 1 day ex utero to 24 months of age. Western blotting analysis clearly shows a pattern of CD40 expression that starts at a high level in 1-day-old animals, dramatically decreases by 1 month of age and continues to decrease until 6 months of age, but then increases through to 24 months of age (data not shown). While this type of analysis does not allow us to determine the cell types expressing CD40, these data nonetheless suggest that CD40 plays a role in the developing and aging central nervous system (CNS). Further studies that are designed to visualize CD40 on neurons and other cells in various brain regions are warranted to determine expression patterns of CD40 on particular subpopulations of cells throughout development and aging.

In addition to its role refereeing neuronal development, the CD40–CD40L interaction also seems to afford protection to neurons undergoing growth factor withdrawal-induced stress. We show that when NGF-β is withdrawn from differentiated PC12 cells or when primary cultures of cortical neurons are deprived of serum, reduction in the Bcl-xL:Bax ratio and LDH release can be opposed by CD40 ligation. The JNK pathway has clearly been shown to play a key role in regulation of neuronal apoptosis induced by growth factor withdrawal (Bruckner et al., 2001; Eilers et al., 2001). Thus, we investigated JNK activation and c-Jun phosphorylation in primary neurons after serum withdrawal, and data show that JNK and c-Jun phosphorylation rapidly ensue after serum withdrawal, and that this effect can be blocked by CD40 ligation. However, CD40 ligation does not mitigate JNK pathway activation in CD40-deficient primary neurons, showing the specificity of this effect to the CD40–CD40L interaction. Thus, much like its role in peripheral immune cells, the CD40–CD40L interaction on neuronal cells generally appears to be trophic, playing key roles in promoting neuronal differentiation, maintenance and survival.

To test further the possible importance of the CD40–CD40L interaction in providing trophic support for neurons, we evaluated whether CD40 receptor deficiency in vivo might have functional consequences. In brains of adult mice deficient for the CD40 receptor, we find decreased neurofilament isoform expression, a reduced Bcl-xL:Bax ratio, neuronal morphological change, increased DNA fragmentation, and gross brain abnormality with age. These effects are clearly evident by 16 months of age, suggesting that the CD40 pathway promotes neuronal maintenance and opposes aging-induced neuronal stress in vivo. Based on the effects of CD40 ligation on activation of the MAPK and JNK pathways, it is tempting to conclude that these brain abnormalities in CD40-deficient mice are due to interruption of neuronal CD40 signaling per se. However, we cannot yet rule out the contribution of other CD40-expressing CNS cells (i.e. microglia, endothelial and smooth muscle cells) to this effect. Nonetheless, either directly or indirectly as a consequence of CD40 deficiency, neuronal subpopulations in the cortex and hippocampus may later degenerate when subjected to the stress associated with normal aging.

Concerning CD40L expression in the CNS, we have found CD40L protein in the developing and aging mouse brain. CD40L is greatly increased in utero and in 1-day-old neonates, decreases through to 6 months of age, and then begins increasing modestly with age to 24 months (data not shown), generally paralleling CNS CD40 expression. However, one key question remains: what is the cellular source of CD40L in the brain? T cells express CD40L en masse upon activation, but the blood–brain barrier normally restricts T cells to the Virchow Robins space, thereby preventing direct contact between them and neurons in the brain parenchyma (except in the case of CNS autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalitis). Perhaps a more likely cellular source of CNS CD40L may be smooth muscle and endothelial cells lining cerebral microvessels, as it has previously been shown that these cells express both CD40 and CD40L (Mach et al., 1997). Additionally, while CD40L exists predominately in association with the cell membrane (Morris et al., 1999), secreted forms of CD40L are produced in the periphery and might be actively transported (transcytosed) across the blood–brain barrier. Clearly, future investigation into which cells supply CD40L to neurons is warranted. Nevertheless, our results represent the first step towards identifying CD40 on neurons and characterizing its role in neuronal biology.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

PC12 (adrenal pheochromocytoma) and N2a (neuroblastoma) cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). PC12 cells were grown in complete F12K medium and were induced to differentiate into neuron-like cells by the addition of 50 ng/ml NGF-β to complete medium for 3–5 days. N2a cells were grown in complete Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) and were induced to differentiate by serum withdrawal and the addition of 0.3 mM dibuturyl cAMP for 48–72 h. PC12 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 plasmid or pcDNA3 encoding H-Ras dominant-negative cDNA (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) using the Gene Therapy Systems kit (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, CA) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer.

Mouse primary culture neuronal cells were prepared as described previously (Chao et al., 1992; Tan et al., 1999). Briefly, cerebral cortices were isolated from CD40 receptor deficient or C57BL/6J (strain-matched) mouse embryos, between 15 and 17 days in utero (pregnant mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), and cortices were mechanically dissociated in trypsin (0.25%) after incubation for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were collected after centrifugation at 290 g, resuspended in EMEM (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10% horse serum, uridine (33.4 µg/ml; Sigma) and fluorodeoxyuridine (13.6 µg/ml; Sigma), and plated on collagen-coated 24-well tissue culture plates at 2.5 × 105 cells per well. More than 98% of these cells stained positive for neurofilament L (using rabbit anti-human neurofilament L antibody; Serotec Ltd, UK).

Western immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

For detection of CD40, primary cultures of cortical neurons or N2a or PC12 cells were plated in six-well tissue culture plates at 5 × 105 cells/well and differentiated (in the case of N2a and PC12 cells) as described above. After treatment, cell lysates were prepared, and western blotting was performed as described previously (Tan et al., 1999). Briefly, identical membranes were hybridized with an anti-CD40 (T-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-actin antibody followed by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. The luminol reagent (Santa Cruz) was then used to develop the blots. Immunoprecipitation was performed for detection of CD40 by incubating 200 µg of total protein of each sample with an anti-CD40 antibody (1:50; L-17; Santa Cruz) overnight with gentle rocking at 4°C, and 10 µl of 50% protein A–Sepharose beads were then added to the samples (1:10; Sigma) prior to gentle rocking for an additional 4 h at 4°C. Following washes with 1× cell lysis buffer, samples were subjected to western blotting as described above. p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation and activity were determined by western blotting and in-gel kinase assay as described previously (Tan et al., 2000) using antibodies against total or phospho-p44/42 MAPK or phospho-Elk1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). JNK phosphorylation and activity were determined using the SAPK/JNK assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology), using antibodies against total or phospho-JNK1 or phospho-c-Jun.

To examine neurofilament expression, brain homogenates were routinely prepared from CD40 receptor deficient mice (B6.129P2-Tnfrsf5™ 1kitk; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (Kawabe et al., 1994) and age-matched control mice (Jackson Laboratory). Western blotting was performed as described above using anti-neurofilament antibodies. Densitometric analysis was performed as described for all immunoblots (Tan et al., 1999). All quantitative data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc comparisons of means using Bonferroni’s or Dunnett’s T3 methods where appropriate, and t-test for independent samples was used to assess significance for single mean comparisons. Alpha levels were set at 0.05 for all analyses, which were performed using SPSS for Windows release 10.0.5.

Immunofluorescence and immunocytochemistry

For immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence studies, N2a or PC12 cells were cultured and differentiated as described above on glass coverslips in six-well tissue culture plates at 5 × 105 cells/well. After treatment, cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.1 M, pH 7.4) for 10 min at 4°C and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma). Following three rinses with PBS, these cultured cells were pre-blocked with serum-free protein blocking solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) prior to staining. The following antibodies were variously employed: rabbit anti-CD40 polyclonal antibody (1:200 dilution; StressGen, Victoria, BC), mouse anti-neurofilament (70 kDa) monoclonal antibody (1:200 dilution; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and anti-CD40 rabbit polyclonal IgG (L-17; 1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz). For immunocytochemistry, the LSAB+ kit (DAKO) was used and for immunofluorescence, the appropriate FITC- and TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were used. Fluorescence signals were observed by dark-field using an Olympus BX-60 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry

Adult human brain tissue was obtained from archived autopsy tissues from the James A.Haley Veteran’s Administration Hospital in Tampa. Human and adult mouse brain tissue sections were cut using a microtome or vibratome (human, 5 µm; mouse, 50 µm), and after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, endogenous peroxidase quenching (0.3% H2O2) and pre-blocking (5% normal goat serum), were processed for 20 min at room temperature prior to primary antibody incubation. Sections were incubated with L-17 (1:50 for mouse brain sections) or N-16 (1:50 for human brain sections; Santa Cruz) antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by an anti-rabbit biotinylated antibody for 15 min at room temperature prior to addition of a streptavidin-complex reagent containing HRP for 15 min at room temperature. For peptide neutralization tests, anti-CD40 antibody was incubated for 30 min with a 10-fold (w/v) excess of CD40 blocking peptide. To detect neuronal dysmorphology, brain sections from CD40 receptor deficient mice were stained with haematoxylin–eosin.

In situ TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling

The working procedure for TUNEL was performed as described previously for detection of DNA fragmentation in situ (Gold et al., 1993). Briefly, brain sections (5 µm) were dewaxed and rehydrated, followed by incubation in proteinase K (20 µg/ml in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5) for 20 min at 37°C, and three rinses in PBS. TUNEL reaction mixture (50 ml, containing 10% v/v of TUNEL enzyme and 90% v/v of TUNEL label; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was then added drop-by-drop onto brain sections and incubated in a humidified chamber for 90 min at ambient temperature. Sections were then washed three times in PBS, mounted and the fluorescence signal was observed by dark-field using an Olympus BX-60 microscope.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Diane Roskamp and Robert Roskamp for their generous support, which made this work possible.

References

- Andjelic S., Hsia,C., Suzuki,H., Kadowaki,T., Koyasu,S. and Liou,H.C. (2000) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and NF-κB/Rel are at the divergence of CD40-mediated proliferation and survival pathways. J. Immunol., 165, 3860–3867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala J., Olofsson,B., Tavitian,A. and Prochiantz,A. (1989a) Develop mental and regional regulation of rab3: a new brain specific ‘ras-like’ gene. J. Neurosci. Res., 22, 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala J., Olofsson,B., Touchot,N., Zahraoui,A., Tavitian,A. and Prochiantz,A. (1989b) Developmental and regional expression of three new members of the ras-gene family in the mouse brain. J. Neurosci. Res., 22, 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberich I., Shu,G., Siebelt,F., Woodgett,J.R., Kyriakis,J.M. and Clark,E.A. (1996) Cross-linking CD40 on B cells preferentially induces stress-activated protein kinases rather than mitogen-activated protein kinases. EMBO J., 15, 92–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise L.H., Gonzalez-Garcia,M., Postema,C.E., Ding,L., Lindsten,T., Turka,L.A., Mao,X., Nunez,G. and Thompson,C.B. (1993) bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell, 74, 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkina G.I., Meistrell,M.E., Botchkina,I.L. and Tracey,K.J. (1997) Expression of TNF and TNF receptors (p55 and p75) in the rat brain after focal cerebral ischemia. Mol. Med., 3, 765–781. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouty-Boye D., Pottin-Clemenceau,C., Doucet,C., Jasmin,C. and Azzarone,B. (2000) Chemokines and CD40 expression in human fibroblasts. Eur. J. Immunol., 30, 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner S.R., Tammariello,S.P., Kuan,C.Y., Flavell,R.A., Rakic,P. and Estus,S. (2001) JNK3 contributes to c-Jun activation and apoptosis but not oxidative stress in nerve growth factor-deprived sympathetic neurons. J. Neurochem., 78, 298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson M.J., Reilly,C.R., Sutcliffe,J.G. and Lo,D. (1998) Mature microglia resemble immature antigen-presenting cells. Glia, 22, 72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C.C., Hu,S., Molitor,T.W., Shaskan,E.G. and Peterson,P.K. (1992) Activated microglia mediate neuronal cell injury via a nitric oxide mechanism. J. Immunol., 149, 2736–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao M.V. (1994) The p75 neurotrophin receptor. J. Neurobiol., 25, 1373–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers A., Whitfield,J., Shah,B., Spadoni,C., Desmond,H. and Ham,J. (2001) Direct inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in sympathetic neurones prevents c-jun promoter activation and NGF withdrawal-induced death. J. Neurochem., 76, 1439–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas M., Iglesias,M., Llecha,N. and Comella,J.X. (1999) Extracellular-regulated kinases and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase are involved in brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated survival and neuritogenesis of the neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. J. Neurochem., 73, 1409–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H.G. and Reichmann,G. (2001) Brain dendritic cells and macrophages/microglia in central nervous system inflammation. J. Immunol., 166, 2717–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Romo L., Bjorck,P., Duvert,V., van Kooten,C., Saeland ,S. and Banchereau,J. (1997) CD40 ligation on human cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors induces their proliferation and differentiation into functional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med., 185, 341–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy T.M., Aruffo,A., Bajorath,J., Buhlmann,J.E. and Noelle,R.J. (1996) Immune regulation by CD40 and its ligand GP39. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 14, 591–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R., Schmied,M., Rothe,G., Zischler,H., Breitschopf,H., Wekerle,H. and Lassmann,H. (1993) Detection of DNA fragmentation in apoptosis: application of in situ nick translation to cell culture systems and tissue sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem., 41, 1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez N. and Cohen,P. (1991) Dissection of the protein kinase cascade by which nerve growth factor activates MAP kinases. Nature, 353, 170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene L.A. and Tischler,A.S. (1976) Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 73, 2424–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi J.C., Torres,R., Kozak,C.A., Chang,R., Clark,E.A., Howard,M. and Cockayne,D.A. (1992) Genomic structure and chromosomal mapping of the murine CD40 gene. J. Immunol., 149, 3921–3926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbins E., Brenner,B., Schlottmann,K., Koppenhoefer,U., Linderkamp,O., Coggeshall,K.M. and Lang,F. (1996) Activation of the Ras signaling pathway by the CD40 receptor. J. Immunol., 157, 2844–2850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasbold J., Hong,J.S., Kehry,M.R. and Hodgkin,P.D. (1999) Integrating signals from IFN-γ and IL-4 by B cells: positive and negative effects on CD40 ligand-induced proliferation, survival and division-linked isotype switching to IgG1, IgE and IgG2a. J. Immunol., 163, 4175–4181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe T., Naka,T., Yoshida,K., Tanaka,T., Fujiwara,H., Suematsu,S., Yoshida,N., Kishimoto,T. and Kikutani,H. (1994) The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity, 1, 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilger E., Kieser,A., Baumann,M. and Hammerschmidt,W. (1998) Epstein–Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation is dependent upon latent membrane protein 1, which simulates an activated CD40 receptor. EMBO J., 17, 1700–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppi T.A., Tough-Bement,T., Lewinsohn,D.M., Lynch,D.H. and Alderson,M.R. (1997) CD40 ligand inhibits Fas/CD95-mediated apoptosis of human blood-derived dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol., 27, 3161–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.H., Dadgostar,H., Cheng,Q., Shu,J. and Cheng,G. (1999) NF-κB-mediated up-regulation of Bcl-x and Bfl-1/A1 is required for CD40 survival signaling in B lymphocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 9136–9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo E., Welsh,K., Matsuzawa,S., Zapata,J.M., Kitada,S., Mitchell,R.S., Ely,K.R. and Reed,J.C. (1999) Differential requirements for tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor family proteins in CD40-mediated induction of NF-κB and Jun N-terminal kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 22414–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach F., Schonbeck,U., Sukhova,G.K., Bourcier,T., Bonnefoy,J.Y., Pober,J.S. and Libby,P. (1997) Functional CD40 ligand is expressed on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and macrophages: implications for CD40–CD40 ligand signaling in atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 1931–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowicz S. and Engleman,E.G. (1990) Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes differentiation and survival of human peripheral blood dendritic cells in vitro. J. Clin. Invest., 85, 955–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A.E., Remmele,R.L.,Jr, Klinke,R., Macduff,B.M., Fanslow,W.C. and Armitage,R.J. (1999) Incorporation of an isoleucine zipper motif enhances the biological activity of soluble CD40L (CD154). J. Biol. Chem., 274, 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V.T., Walker,W.S. and Benveniste,E.N. (1998) Post-transcriptional inhibition of CD40 gene expression in microglia by transforming growth factor-β. Eur. J. Immunol., 28, 2537–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted J.B., Carlson,K., Klebe,R., Ruddle,F. and Rosenbaum,J. (1970) Isolation of microtubule protein from cultured mouse neuroblastoma cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 65, 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguet-Navarro J., Dalbiez-Gauthier,C., Moulon,C., Berthier,O., Reano,A., Gaucherand,M., Banchereau,J., Rousset,F. and Schmitt,D. (1997) CD40 ligation of human keratinocytes inhibits their proliferation and induces their differentiation. J. Immunol., 158, 144–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S.K., Matzelle,D.D., Wilford,G.G., Hogan,E.L. and Banik,N.L. (2000) Increased calpain expression is associated with apoptosis in rat spinal cord injury: calpain inhibitor provides neuroprotection. Neurochem. Res., 25, 1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schendel S.L., Montal,M. and Reed,J.C. (1998) Bcl-2 family proteins as ion-channels. Cell Death Differ., 5, 372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T., Kawaguchi,Y., Harigai,M., Takagi,K., Ohta,S., Fukasawa,C., Hara,M. and Kamatani,N. (2000) Increased CD40 expression on muscle cells of polymyositis and dermatomyositis: role of CD40–CD40 ligand interaction in IL-6, IL-8, IL-15 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production. J. Immunol., 164, 6593–6600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Town,T., Paris,D., Mori,T., Suo,Z., Crawford,F., Mattson,M.P., Flavell,R.A. and Mullan,M. (1999) Microglial activation resulting from CD40–CD40L interaction after β-amyloid stimulation. Science, 286, 2352–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Town,T. and Mullan,M. (2000) CD45 inhibits CD40L-induced microglial activation via negative regulation of the Src/p44/42 MAPK pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 37224–37231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.M., DeMarco,M., D’Arcangelo,G., Halegoua,S. and Brugge,J.S. (1992) Ras is essential for nerve growth factor- and phorbol ester-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of MAP kinases. Cell, 68, 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres R.M. and Clark,E.A. (1992) Differential increase of an alternatively polyadenylated mRNA species of murine CD40 upon B lymphocyte activation. J. Immunol., 148, 620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooten C. (2000) Immune regulation by CD40–CD40-l interactions—2; Y2K update. Front. Biosci., 5, D880–D893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Foy,T.M., Laman,J.D., Elliott,E.A., Dunn,J.J., Waldschmidt,T.J., Elsemore,J., Noelle,R.J. and Flavell,R.A. (1994) Mice deficient for the CD40 ligand. Immunity, 1, 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C.Y. and Greene,L.A. (1998) Prevention of PC12 cell death by N-acetylcysteine requires activation of the Ras pathway. J. Neurosci., 18, 4042–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Gu,L., Holden,J., Yeager,A.M. and Findley,H.W. (2000) CD40 ligand upregulates expression of the IL-3 receptor and stimulates proliferation of B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in the presence of IL-3. Leukemia, 14, 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirrgiebel U. and Lindholm,D. (1996) Constitutive phosphorylation of TrkC receptors in cultured cerebellar granule neurons might be responsible for the inability of NT-3 to increase neuronal survival and to activate p21 Ras. Neurochem. Res., 21, 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]