Abstract

To develop radiomics models based on baseline multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data and clinical characteristics to predict 6-month progressive disease (PD) status in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients receiving targeted therapy, enabling long-term prognostication for early stratification of high-risk mortality groups. Eighty-eight metastatic GIST patients undergoing targeted treatment were included in this study and randomly divided into a training cohort and a validation cohort in a ratio of 2:1, comprising 32 disease progression (PD)-positive patients and 56 PD-negative patients. Follow-up computed tomography (CT) or MRI scans obtained 6 months after the baseline MRI were used to determine progressive disease (PD) status according to RECIST 1.1 criteria. Radiomics features were extracted from baseline T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (CE-T1WI), and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences. Correlation-based feature selection, information gain, and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression were employed in a ten-fold cross-validation to select relevant image features. The radiomics score (Radscore), calculated from the three MRI sequences, along with statistically significant clinical characteristics between the PD-positive and PD-negative groups in both cohorts, were used in multilogistic logistic regression to build the radiomics models. Potential variables for stratifying metastatic GIST patients into distinct mortality risk categories were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, with both dichotomous (Radscore, radiomics predictions and 6-month PD status) and trichotomous (mitotic count and current tumor distribution) classification approaches. The radiomics model, integrating Radscore, mitotic count per 50 high-power fields (HPFs), and current tumor distribution, demonstrated robust discriminatory performance with area under the curves (AUCs) of 0.847–0.974. This integrated model achieved high predictive accuracy for 6-month PD status, yielding classification rates of 94.4% in the training cohort and 84.2% in the testing cohort. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated significant mortality risk stratification (all p < 0.05) for both continuous and categorical variables across cohorts. Specifically, dichotomized variables including Radscore (cutoff > -1.01), radiomics predictions (cutoff > -2.49), and 6-month PD status, along with the trichotomized mitotic count (< 5, 5–10, > 10 per 50 HPFs), effectively discriminated high-risk patients. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed cohort-specific prognostic patterns, with PD status at 6 months demonstrating the highest predictive accuracy in the training cohort (C-index = 0.782, 95% CI 0.750–0.814), while mitotic count emerged as the strongest predictor in the testing cohort (C-index = 0.819, 95% CI 0.767–0.870). Radiomics models integrating baseline MRI and clinical data provide accurate short-term prognostication of 6-month PD status in metastatic GIST patients, facilitating early risk stratification. However, while the model predicts PD status as a marker of early treatment failure, it does not replace the established prognostic value of PD status itself for long-term survival outcomes. These models may guide personalized therapy adjustments in the short term, but long-term risk assessment should rely on comprehensive clinical-pathological evaluation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-22386-4.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, Radiomics, Magnetic resonance imaging, Overall survival, Targeted treatment

Subject terms: Cancer, Gastroenterology, Medical research, Oncology

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), the most common mesenchymal tumor originating of the digestive tract, arising from interstitial cells of Cajal and poses significant clinical challenges due to its metastatic potential. Approximately 40% of patients develop metastatic disease, for which tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting KIT/platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) mutations remain cornerstone therapies1–3. However, heterogeneous TKI responses driven by mutation diversity and therapeutic complexity necessitate objective tools to predict early treatment failure and optimize personalized strategies.

Imaging plays a pivotal role in GIST management, yet conventional modalities like computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) face limitations. While CT texture analysis and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET metabolic changes have shown prognostic value4,5, their reliance on subjective Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria and FDG avidity restricts universal applicability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), has emerged as a superior modality for early response assessment, especially in non-FDG-avid tumors6–8. Despite these advances, traditional imaging analyses predominantly focus on semantic features, overlooking the wealth of quantitative data embedded within multidimensional images.

This gap underscores the promising role of radiomics as a high-throughput analytical method capable of extracting subvisual imaging features to characterize tumor heterogeneity9. While CT-based radiomics has been explored for imatinib response prediction10, the integration of multi-parametric MRI (T1-weighted imaging [T1WI], T2WI, apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC]) remains uncharted territory in metastatic GIST. Current studies prioritize risk stratification or mitotic index prediction11,12, leaving a significant unmet need for the early identification of non-responders to facilitate timely therapeutic adjustments.

In this study, we present the first radiomics investigation leveraging baseline multi-parametric MRI (T2WI, contrast-enhanced T1WI, ADC) combined with clinical variables to predict 6-month progressive disease (PD) in metastatic GIST. Our machine learning-driven models are designed to (1) outperform conventional imaging metrics in PD prediction and (2) enable mortality risk stratification, ultimately minimizing treatment delays and toxicity.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, and the requirement for written informed consent was waived. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

All participants in this study were of Chinese ethnicity. Medical images, including MRI and CT, along with clinical data of consecutive patients from January 2019 to April 2023 were retrospectively enrolled. The inclusion criteria were: (1) pathologically confirmed GIST without evidence of other tumor types; (2) metastatic GIST with at least one target lesion ≥ 10 mm; (3) total targeted therapy duration exceeding 6 months after baseline MRI examination; and (4) baseline MRI and follow-up CT or MRI at 6-month intervals. Patients were excluded if they (1) had severe complications requiring treatment interruption or loss to follow-up; or (2) lacked complete MRI sequences and clinical data. We hypothesized our models would achieve an accuracy of 0.80 for predicting disease progression (PD), based on prior studies with PD prediction accuracies of 0.72–0.886. The assumed PD prevalence was 40% based on these prior studies6, while the null hypothesis prevalence was 0.5. Using a sample size estimation formula for diagnostic test accuracy12, we determined at least 21 PD positive and 13 PD negative patients would be required to detect the expected accuracy of 0.80 with 95% confidence and 90% power.

Therapeutic response evaluation

Previous studies have found RECIST 1.1 criteria to be more suitable than Choi and volumetry criteria for evaluating treatment effects in metastatic GIST13. Therefore, we utilized RECIST 1.1 to assess treatment response 6 months after the baseline MRI. Patients were then categorized into two groups: those with progressive disease (PD) according to RECIST 1.1 were classified as PD-positive, while those exhibiting a complete response, partial response, or stable disease were classified as PD-negative.

MR image acquisition and radiomics feature extraction

Abdominal MR images were acquired using 1.5T Amira or 3.0T Prisma systems (Siemens, Germany) with a 13-channel abdominal coil. All patients underwent standard clinical imaging protocols including T2WI, contrast-enhanced T1WI (CE-T1WI), and DWI. The parameters for each MRI sequence are summarized in supplementary Table S1. MR images of all study cases were imported into the lesion segmentation and radiomics analysis software 3D-SLICER (Version 3.8.0, http://www.slicer.org). First, T2WI, CE-T1WI and ADC map images were preprocessed with resampling (1 × 1 × 1 mm voxel size), N4 bias field correction14, and image normalization by the 3D-SLICER software as previously described15. Second, the largest metastatic tumor was manually segmented on each sequence by an abdominal radiologist (with 7 years of experience) blinded to clinical data. The tumor volume of interest (VOI) was delineated slice-by-slice, carefully avoiding vessels, air, and artifacts. Finally, 1,223 radiomic features were extracted from the VOIs using 3D-SLICER’s Segmentation and PyRadiomics modules. Features included: (1) First Order Statistics (234 features); (2) Shape-based (3D) (14 features); (3) Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) (312 features); (4) Gray Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM) (208 features); (5) Gray Level Size Zone Matrix (GLSZM) (208 features); (6) Gray Level Dependence Matrix (GLDM) (182 features); and (7) Neighboring Gray Tone Difference Matrix (NGTDM) (65 features).

Radiomics analysis and statistical analysis

Radiomics analysis and statistical analyses were conducted using Weka (version 3.8.3), R software (version 3.4.3) and MedCalc software (version 18.0)16–18. Univariate analysis of clinical characteristics was performed with the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. All statistical tests were two-tailed and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The inter- and intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated to evaluate the consistency of radiomics features extracted based on tumor volumes of interest (VOIs) delineated by two radiologists. Radiologist 1 (TX Z, with 7 years of experience) first completed VOIs for all cases. Radiologist 2 (MH C, with 13 years of experience) then outlined VOIs for 30 randomly selected patients to assess inter-observer repeatability. Radiologist 1 also re-delineated the VOIs for the same 30 patients after one month to evaluate intra-observer repeatability. Radiomics features with ICC ≥ 0.75 were considered reproducible and retained for analysis.

Feature dimensionality reduction and selection were conducted on the training cohort through the following steps: (1) Z-score Normalization: Features were normalized using Z-score normalization to eliminate dimensional effects19; (2) Handling Missing Values: Missing values in 377 texture features for 3 cases were filled using the median value; (3) Feature Selection: The feature selection pipeline employed correlation-based feature selection (CFS) and information gain (InfoGain) to eliminate redundant features while preserving discriminative power, followed by LASSO regression to optimize model sparsity and generalizability in our high-dimensional, small-sample cohort20,21. CFS and InfoGainAttributeEval were utilized within a ten-fold cross-validation cycle. Since filter-based methods like CFS and InfoGain rank features independently of classifiers, hyperparameter tuning was not necessary; (4) The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Regularization: Hyperparameter optimization was conducted within the training cohort to prevent overfitting. For LASSO regression, the regularization strength (λ) was determined by tenfold cross-validation, maximizing the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Optimal radiomics features selected from the candidate features were used to calculate radiomics scores (Radscore); (5) Univariate Analysis: Differences in clinical data between the PD-positive and PD-negative groups were compared using univariate analysis.

A radiomics model was developed to classify PD-positive and PD-negative GIST cases by integrating the Radscore (derived from LASSO-selected imaging features) and significant clinical predictors through multivariate logistic regression. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit of the nomogram. Model performance was evaluated on the independent test set with bootstrapping (1000 iterations) to calculate optimism-adjusted metrics, including the area under curve (AUC), accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). A baseline clinical model was developed using standard logistic regression methodology with mitotic count and tumor distribution as predictors, and was evaluated on the test cohort. AUCs were statistically compared using the DeLong method.

Post-MR monitoring and survival analysis

The primary outcome was PD status at 6 months, as early prediction of treatment response is critical for timely clinical decision-making. To ensure standardized follow-up, all patients underwent CT or MR examinations every 3–6 months after the initial MR examination at enrollment, with a minimum follow-up period of 6 months. The secondary endpoint was overall survival (OS), defined as the interval between the initial MR exam and the date of death or the last follow-up. Given that OS analysis requires longer-term data, variables were first analyzed for PD classification to prioritize early clinical utility, followed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to evaluate their prognostic value for OS. Specifically, potential variables associated with mortality risk were assessed by plotting survival curves and comparing group differences using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank tests.

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 88 GIST patients were recruited and randomly divided into a training cohort and a validation cohort in a ratio of 2:1, including 32 PD-positive patients and 56 PD-negative patients (Fig. 1). Statistically significant differences were observed in current tumor distribution and mitotic count per 50 high-power fields (HPFs) between the PD-positive and PD-negative groups in both cohorts (p < 0.05). Specifically, the PD-positive group was more likely to have multi-organ involvement, whereas over 60% of PD-negative patients had single-organ disease. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, primary tumor site, tumor rupture, national institutes of health (NIH) grade and tumor components in either cohort. Other characteristics, such as prior surgical resection of primary tumor, Ki67, number of lesions, largest target lesion size, and treatment protocol, differed between the two groups in only one of the cohorts. The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patient recruitment.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study cohorts.

| Clinical characteristics | Training cohorts (N = 58) | Testing cohorts (N = 30) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NON-PD Group | PD Group | p value | NON-PD Group | PD Group | p value | |

| Age, mean ± sd | 55.88 ± 13.48 | 58.43 ± 13.45 | 0.678 | 54.17 ± 5.78 | 51.14 ± 13.18 | 0.597 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.933 | 1.000 | ||||

| Male | 27 (46.6%) | 14 (24.1%) | 16 (53.3%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| Female | 11 (19%) | 6 (10.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Primary tumor site of GIST, n (%) | 0.255 | 0.299 | ||||

| Stomach | 14 (24.1%) | 4 (6.9%) | 6 (20%) | 4 (13.3%) | ||

| Small intestine | 18 (31%) | 14 (24.1%) | 12 (40%) | 6 (20%) | ||

| Colorectal or Peritoneum | 6 (10.3%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Surgical of primary tumor | 0.012* | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 22 (37.9%) | 18 (31%) | 16 (53.3%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| No | 16 (27.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Tumor rupture, n (%) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 5 (8.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| No | 33 (56.9%) | 18 (31%) | 15 (50%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| NIH, n (%) | 0.133 | 0.104 | ||||

| Very low | 3 (5.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Low | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Intermediate | 14 (24.1%) | 4 (6.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| High | 21 (36.2%) | 16 (27.6%) | 11 (36.7%) | 12 (40%) | ||

| Mitotic count per 50HPFs, n (%) | 0.026* | < 0.001* | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 19 (32.8%) | 5 (8.6%) | 14 (46.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||

| 6–10 | 4 (6.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| > 10 | 15 (25.9%) | 15 (25.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | 9 (30%) | ||

| Ki67, n (%) | 0.151 | 0.002* | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 18 (31%) | 6 (10.3%) | 13 (43.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| 5–20 | 9 (15.5%) | 3 (5.2%) | 5 (16.7%) | 6 (20%) | ||

| > 20 | 11 (19%) | 11 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (13.3%) | ||

| Current tumor distribution, n (%) | < 0.001* | 0.035* | ||||

| Liver metastasis | 6 (10.3%) | 2 (3.4%) | 5 (16.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Multiple organ metastasis | 8 (13.8%) | 16 (27.6%) | 7 (23.3%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| Peritoneal metastasis | 24 (41.4%) | 2 (3.4%) | 6 (20%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Lesions number, n (%) | 0.012* | 0.431 | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 24 (41.4%) | 6 (10.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | ||

| 6–10 | 2 (3.4%) | 6 (10.3%) | 5 (16.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| > 10 | 12 (20.7%) | 8 (13.8%) | 6 (20%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Largest target lesion size, n (%) | 0.847 | < 0.001* | ||||

| < 5 cm | 6 (10.3%) | 4 (6.9%) | 7 (23.3%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| 5–10 cm | 14 (24.1%) | 6 (10.3%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| > 10 cm | 18 (31%) | 10 (17.2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Tumor components, n (%) | 0.183 | 1.000 | ||||

| Solid component < 10% | 6 (10.3%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Solid component < 50% | 15 (25.9%) | 4 (6.9%) | 7 (23.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | ||

| Solid component ≥ 50% | 17 (29.3%) | 14 (24.1%) | 11 (36.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | ||

| Treatment protocol, n (%) | 0.026* | 0.112 | ||||

| Imatinib | 15 (25.9%) | 4 (6.9%) | 8 (26.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||

| Sunitinib/Anlotinib | 4 (6.9%) | 8 (13.8%) | 6 (20%) | 7 (23.3%) | ||

| Third line and Others | 19 (32.8%) | 8 (13.8%) | 4 (13.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | ||

| OS, n (%) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | ||||

| Survival | 29 (50%) | 3 (5.2%) | 13 (43.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Death | 9 (15.5%) | 17 (29.3%) | 5 (16.7%) | 12 (40%) | ||

| OS Time (MR), mean ± sd | 44.39 ± 15.08 | 21.63 ± 9.82 | < 0.001* | 40.17 ± 15.35 | 21.17 ± 8.09 | 0.002* |

Notes: p values were calculated using univariate analysis to assess associations of characteristics with progressive disease (PD) status in cohorts receiving targeted therapy for metastatic GIST; *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Selection of extracted radiomics features

The median inter-observer ICC values based on the radiomics features extracted from T2WI, CE-T1WI and ADC sequences were 0.958, 0.885, and 0.918, respectively. The median intra-observer ICC values were 0.968, 0.892, and 0.920, respectively. Intra-observer variability was minimal, with a median ICC greater than 0.89 for all sequences, confirming the segmentation reproducibility among individual readers. Features with ICC ≥ 0.75, indicating good inter- and intra-observer agreement, comprised 81.6% (998/1223), 67.0% (819/1223), and 77.8% (951/1223) from each sequence, respectively. These reproducible features are retained for subsequent analysis.

The CFS method with a probability threshold of ≥ 50%, combined with InfoGainAttributeEval employing a threshold of 0.2 average merit, was used to eliminate redundant and irrelevant features. Following this, the LASSO regression was adopted for further imaging feature selection. These steps were integrated into a ten-fold cross-validation iteration cycle to reduce case partition bias and variance. A radiomics score (Radscore) reflecting the predictors of PD status was then calculated for each segmented lesion. Feature dimensionality reduction identified four discriminative radiomics features across multi-sequence MRI, comprising wavelet-LLH_gldm_ DependenceNonUniformityNormalized from contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, wavelet-LHL_glrlm_LowGrayLevelRunEmphasis from T2-weighted imaging,, and two features from apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping: wavelet-LLH_glszm_ ZonePercentage and wavelet-HLL_firstorder_RobustMeanAbsoluteDeviation. These high-dimensional texture features22 (Table 2), extracted through wavelet transformation, demonstrated statistically significant differences between PD-positive and PD-negative groups (Mann–Whitney U test, all p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Image features selected using CfsSubsetEval + BestFirst followed by InfoGainAttributeEval + Ranker feature selection methods for the Radscore calculation.

| Seq | Image filtering | Feature class | Radiomics feature |

Group PD Negative M (P25, P75) |

Group PD Positive M (P25, P75) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2WI | wavelet-LHL | glrlm | LowGrayLevelRunEmphasis | 0.037 (−0.333, 0.882) | −0.421 (−0.962, −0.275) | 0.004* |

| T1WI | wavelet-LLH | gldm | DependenceNonUniformityNormalized | −0.074 (−0.195, 0.020) | 0.229 (0.076, 0.305) | < 0.001* |

| ADC | wavelet-LLH | glszm | ZonePercentage | 0.186 (−0.226, 0.376) | 0.672 (0.402, 0.876) | < 0.001* |

| ADC | wavelet-HLL | firstorder | RobustMeanAbsoluteDeviation | −0.285 (−0.290, −0.284) | −0.281 (−0.282, −0.278) | 0.002* |

Glrlm, gray-level run length matrix; gldm, gray-level dependence matrix; glszm, gray-level size zone matrix. Notes: p values were calculated to compare radiomic features between the progressive disease (PD)-positive and PD-negative groups. *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Performance of single characteristic and radiomics models

The final integrated radiomics model included clinical variables retained through univariate screening (p < 0.05) and multivariable regression (p < 0.05), specifically mitotic count per 50 HPFs and tumor distribution (single-organ vs. multi-organ). Alongside a radiomic signature (Radscore) derived from four wavelet-transformed texture features rigorously selected through LASSO regression across multiple MRI sequences. Comparative analyses revealed the baseline clinical model (using only mitotic count and tumor distribution) demonstrated moderate predictive performance, with AUCs of 0.879 (95% CI: 0.795–0.963) in the training cohort and 0.778 (95% CI: 0.573–0.983) in validation. The radiomics model exhibited excellent discriminative performance with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.974 (95% CI: 0.893–0.998) in the training cohort. Furthermore, the model demonstrated strong calibration accuracy, as evidenced by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (p = 0.9451), confirming good agreement between predicted probabilities and actual clinical outcomes. Comparative analysis using DeLong’s test revealed statistically superior predictive capability (all p < 0.05) with absolute AUC improvements of 10.8% compared to the clinical model (ΔAUC = + 0.108), 21.1% relative to the optimal single radiomic feature (T1WI-derived wavelet-LLH_gldm_DependenceNonUniformityNormalized; ΔAUC = + 0.17), and 36.6% versus tumor distribution assessment alone (ΔAUC = + 0.261). The superior predictive performance of the radiomics model was consistently maintained during validation when compared against individual clinical and radiomic characteristics. Comprehensive performance evaluations, including detailed ROC analyses and nomogram visualization for clinical application, are presented in Fig. 2 and Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Nomogram and ROC curves for predicting disease progression of metastatic GIST. Nomogram (a) for predicting PD status in metastatic GIST patients. ROC curves for Radscore, single radiomic feature, single clinical feature, and the nomogram predicting PD status after 6 months of treatment in the training cohort (b-c).

Table 3.

The predictive performance of nomogram compared to each single parameter and clinical model for determining disease progression status in GISTs.

| Parameter | Cohort | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2WI (glrlm) | Training Cohort | 0.900 | 0.632 | 0.563 | 0.923 | 0.724 | 0.729 (0.593–0.865) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.889 | 0.750 | 0.842 | 0.818 | 0.833 | 0.782 (0.595–0.970) | |

| T1WI (gldm) | Training Cohort | 0.850 | 0.763 | 0.654 | 0.906 | 0.792 | 0.804 (0.688–0.920) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.500 | 0.833 | 0.818 | 0.526 | 0.633 | 0.588 (0.378–0.798) | |

| ADC (glszm) | Training Cohort | 0.700 | 0.947 | 0.875 | 0.857 | 0.862 | 0.788 (0.635–0.941) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.722 | 0.833 | 0.867 | 0.667 | 0.767 | 0.810 (0.643–0.977) | |

| ADC (firstorder) | Training Cohort | 0.850 | 0.789 | 0.680 | 0.909 | 0.810 | 0.747 (0.605–0.890) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.500 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.571 | 0.700 | 0.727 (0.539–0.915) | |

| Mitotic count per 50HPFs | Training Cohort | 0.750 | 0.605 | 0.500 | 0.821 | 0.655 | 0.664 (0.533–0.796) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.778 | 0.917 | 0.933 | 0.733 | 0.833 | 0.880 (0.754–1.000) | |

| Current tumor distribution | Training Cohort | 0.900 | 0.632 | 0.563 | 0.923 | 0.724 | 0.713 (0.587–0.840) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.333 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.500 | 0.600 | 0.583 (0.399–0.768) | |

| Clinical model | Training Cohort | 0.921 | 0.550 | 0.795 | 0.786 | 0.793 | 0.879 (0.795–0.963) |

| Validation Cohort | 1.000 | 0.586 | 0.783 | 1.000 | 0.833 | 0.778 (0.573–0.983) | |

| Nomogram | Training Cohort | 0.974 | 0.850 | 0.925 | 0.944 | 0.931 | 0.974 (0.893–0.998) |

| Validation Cohort | 0.889 | 0.750 | 0.842 | 0.818 | 0.833 | 0.847 (0.669–0.952) |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the curve.

Risk stratification and survival prediction

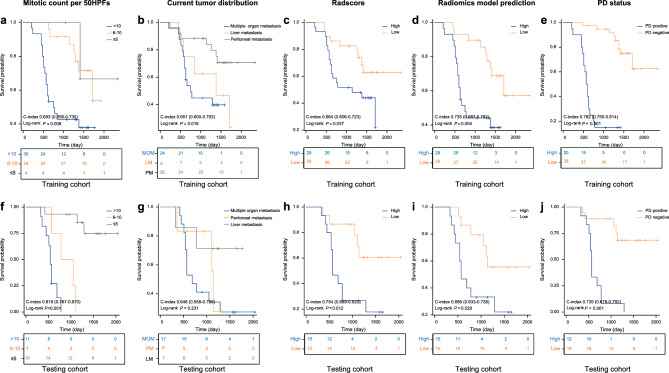

In the training cohort, the median overall survival (OS) for PD-positive and PD-negative patients were 19.5 months and 47.5 months, respectively. The 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 90.0%, 25.0%, 15.0%, and 15% for PD-positive patients, compared to 100%, 97.4%, 94.7%, and 76.3% for PD-negative patients. Similarly, in the testing cohort, the median OS for PD-positive and PD-negative patients were 19 months and 39.5 months, respectively, with 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 91.7%, 25.0%, 8.3%, and 0% for PD-positive patients, and 94.4%, 88.9%, 83.3%, and 72.2% for PD-negative patients. Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that Radscore > −1.01, radiomics predictions > −2.49, PD status at 6 months post-baseline MRI, and key clinical data (e.g., mitotic count per 50 HPFs) effectively identified patients at higher mortality risk in both cohorts (p < 0.05). However, clinical data regarding current tumor distribution was only significant in the training cohort. To further validate the prognostic value of these variables, we performed univariate Cox regression analysis. In the training cohort, PD status demonstrated the highest predictive power for survival (C-index = 0.782, 95% CI 0.750–0.814), followed by radiomics nomogram predictions (C-index = 0.735, 95% CI 0.687–0.782), mitotic count (C-index = 0.693, 95% CI 0.556–0.730), and Radscore (C-index = 0.664, 95% CI 0.606–0.723). In the testing cohort, mitotic count showed the strongest association with mortality risk (C-index = 0.819, 95% CI 0.767–0.870), followed by PD status (C-index = 0.735, 95% CI 0.678–0.792) and Radscore (C-index = 0.754, 95% CI 0.689–0.820) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to mitotic count per 50HPFs, current tumor distribution, Radscore predicted and radiomics model (nomogram) predicted disease progression, and PD status at 6months after baseline MRI in the training cohort (a-e) and testing cohort (f-j).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that multi-parameter MRI-based radiomics models, leveraging advanced machine learning algorithms, offer significant prognostic insights into both targeted therapy response and overall survival (OS) in metastatic GIST. Three key findings emerge: First, high-dimensional texture features extracted from T2WI and ADC sequences (Table 3) outperformed conventional clinical characteristics in predicting early therapeutic efficacy, highlighting the added value of quantitative imaging biomarkers. Second, integrative radiomics models combining multi-sequence MRI data achieved superior predictive accuracy compared to single-modality imaging or clinical variables alone, suggesting synergistic prognostic information across imaging phenotypes. Third, although the model predicts PD status as an early endpoint, PD status itself retains irreplaceable value for long-term risk stratification. Clinically, this supports a two-step strategy: utilizing baseline radiomics for early therapy adjustments, followed by continuous monitoring of PD status for survival prognosis.

Consistent with our findings, previous studies based on single MRI sequences have demonstrated the potential of MRI features in evaluating the response to targeted therapy in GISTs6. Notably, our study investigated multiple MRI sequences simultaneously (T2WI, CE-T1WI, and ADC), resulting in more comprehensive and efficient outcomes. Functionally, ADC images provide information about tissue cellularity, CE-T1WI images reveal tumor vascularization and proliferative activity, and T2WI images primarily reflect the water content of lesions, which is associated with cystic degeneration and necrosis7,23. Previous research has indicated that tumor vascularization and tissue cellularity are linked to the sensitivity of GISTs to targeted therapy7,22. Additionally, decreased proliferating cells and micro-vessel density, alongside increased apoptotic cell density and tumor necrosis, have been observed in GISTs under targeted therapy. Hence, we speculate that the improved performance of our combined models is due to the rich and complementary features extracted from multiple sequences, as suggested in previous research24,25. Despite the promising results, these findings are preliminary and strongly advise against clinical implementation of the model until rigorous external validation and prospective trials confirm its utility in diverse populations.

The predictive performance of our multi-parameter MRI-based radiomics model was better than those of previous studies6,7, which might be related to the rich information provided by 3D-VOI analysis, the combination of multiple sequences, and the radiomics-based machine learning model24,26. The radiomics approach enables the extraction of numerous multidimensional features from medical images that are invisible to the naked eyes. In our study, four texture features were selected for building the combined model, while geometric features were excluded, suggesting their limited discernibility for response assessment. This finding aligns with previous studies reporting that tumor size alteration is not meaningful for early prediction of GIST response to targeted therapy6. The features selected in our study primarily describe tissue heterogeneity22, which may indicate more complex liquid components such as mucoid degeneration, necrosis and hemorrhage at different stages, widely scattered in the lesions of the PD-negative group (Fig. 3). These findings corroborate previous reports establishing the prognostic value of tumor heterogeneity in GIST5,6. While CT-based radiomics studies have achieved promising results (AUCs 0.85–0.92)27,28, our MRI-based approach offers distinct advantages including superior soft tissue contrast for heterogeneity evaluation, more stable multi-sequence feature analysis, and reliable applicability for contrast-contraindicated patients through non-enhanced T2WI-derived features28,29. The growing field of radiomics has seen increasing interest in both cross-modal approaches combining CT and MRI30,31 and deep learning methods, though we intentionally employed traditional machine learning to maintain feature interpretability for clinical translation, accommodate our moderate cohort size (n = 88), and enable direct comparison with established clinical models32–35. Future research directions could productively explore hybrid models that combine our validated radiomic features with deep learning architectures while preserving clinical interpretability, potentially further enhancing predictive performance for GIST treatment response assessment.

Fig. 3.

Baseline MRI characteristics and radiomics analysis comparing two metastatic GIST patients with differential treatment responses. The upper panel (a-f) shows Patient 1 who achieved stable disease, while the lower panel (g-l) displays Patient 2 who experienced progressive disease. For each patient, we present comprehensive imaging evaluation including anatomical sequences (T2-weighted imaging [T2WI; a/g] and equilibrium-phase contrast-enhanced MRI [CE-MRI; b/h]) and functional sequences (diffusion-weighted imaging [DWI; b = 800 s/mm2; c/i] with corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC] maps [d/j]). The segmentation workflow illustrates manual tumor delineation (e/k) and subsequent reconstruction of 3D regions of interest (ROIs; f/l) used for radiomics analysis. Notably, Patient 1 demonstrated higher T2WI signal heterogeneity, suggesting complex tissue architecture potentially reflecting mucoid degeneration, necrosis, or hemorrhage, along with lower CE-MRI feature values indicating reduced vascularization and permeability. In contrast, Patient 2 exhibited inverse imaging patterns consistent with more aggressive tumor biology, including different vascularization patterns and tissue characteristics that correlated with subsequent disease progression. These radiomics features provide valuable insights into the underlying tumor biology and help explain the differential treatment responses observed clinically.

Several potential confounders may influence treatment response assessment in our study, including treatment heterogeneity (e.g., variations in targeted therapy regimens and dose adjustments), biological factors such as tumor molecular subtypes and variability in timing of response assessment. While stratified analysis would be valuable to account for these factors, our current sample size (n = 88) limits our ability to perform such subgroup analyses without risking overfitting or loss of statistical power. Future large-scale, prospective studies with standardized treatment protocols and comprehensive molecular profiling are needed to better control for these potential confounders.

A previous study highlighted shorter survival among GIST patients with both liver and peritoneal disease compared to those with disease in only one organ36. Similarly, our study revealed significant differences in current tumor distribution, mitotic count per 50 HPFs, and overall survival (OS) between PD-positive and PD-negative groups (Table 1). Notably, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that current tumor distribution significantly differed only in the training cohort. Mitotic count per 50 HPFs, Radscore, radiomics predictions, and PD status at the 6-month follow-up after baseline MRI effectively identified patients at increased risk of mortality in both the training and testing cohorts (Fig. 4), underscoring the predictive potential of our radiomics model based on baseline multi-parameter MRI, specific clinical characteristics, and PD status for stratifying high-risk groups in metastatic GIST. A key highlight of our study is the use of only baseline MRI data to build the predictive model, enhancing its early applicability and convenience in clinical practice, while also potentially optimizing patient treatment plans. Intriguingly, the elevated C-index of mitotic count in the testing cohort (0.819 vs. 0.693 in training) underscores potential sampling variability or subgroup heterogeneity, warranting external validation in larger multi-center datasets. Although our model achieves robust short-term prediction of 6-month PD status, it is not intended to supersede PD status itself for long-term prognostication. Future studies should investigate serial radiomics profiling to capture tumor evolution dynamics, thereby bridging short-term predictions with longitudinal survival outcomes.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the single-center design, modest sample size (n = 88), and imbalanced group distribution (PD-positive vs. PD-negative ratio 1:1.75) may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability. External validation through large-scale, prospective multi-center, balanced cohorts is essential to confirm our findings. Second, the manual segmentation of volumes of interest (VOIs), while ensuring radiologist expertise input, remains time-intensive and operator-dependent. Future implementations should integrate AI-powered segmentation tools (e.g., nnU-Net or DeepMedic) and automated feature extraction algorithms to enhance efficiency and reproducibility. Third, as a patient-centric analysis, we evaluated only the dominant lesion per patient, potentially overlooking inter-lesion heterogeneity. Subsequent research should adopt lesion-based stratification or multi-lesion radiomics analysis to better capture tumor complexity. Fourth, although prognostic, wavelet-based radiomic features (e.g., glcm Entropy) lack direct molecular or mechanistic validation. This reflects a broader limitation in radiomics, where mathematical surrogates for pathophysiology require validation through multi-omics integration. Future work must prioritize spatial transcriptomics and radiomic-pathologic mapping to resolve these relationships.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that radiomics models incorporating baseline multi-parameter MRI features and key clinical characteristics can accurately predict treatment response in metastatic GIST patients receiving targeted therapy. The model’s ability to stratify high-risk groups carries important clinical implications, potentially serving as a decision-support tool for personalized therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor;

- PD

Progressive disease;

- T2WI

T2-weighted imaging;

- CE-T1WI

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging;

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging;

- ADC

Apparent diffusion coefficient;

- AUC

Area under the curve;

- TKIs

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors;

- OS

Overall survival;

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator;

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

Author contributions

Guifang Lin, Lili Wang and Yongjian Zhou designed the research study and performed the research; Guifang Lin and Tianxiu Zou wrote the manuscript and collected data; Quanjian Zhu, Fenxia Yang and Dongwei Ruan contributed new Software and analytic tools; Wang LL and Zheng B analyzed the data; Minghong Chen and Weiwen Lin provided methods; Yiming Liao, Jiangao Xie and JingMing Chen searched literature; Yongjian Zhou managed the project. All authors have read and approve the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by 1. Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (2021Y9054; 2023Y9175); 2. Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (2022QH1038).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval (2023KJT007) was obtained from the ethics review board of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital; the requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Guifang Lin, Quanjian Zhu, Fenxia Yang and Tianxiu Zou are equal contributions first authors.

Contributor Information

Lili Wang, Email: 751501231@qq.com.

Yongjian Zhou, Email: zhouyjbju2@163.com.

References

- 1.Strauss, G. & George, S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr. Oncol. Rep.27, 1–10 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serrano, C. et al. 2023 Geis Guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol.15, 17588359231192388 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkataraman, V., George, S. & Cote, G. M. Molecular advances in the treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Oncologist28, 671–681 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barat, M. et al. Ct and Mri of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: New trends and perspectives. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J.75, 107–117 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weeda, Y. A. et al. Early prediction and monitoring of treatment response in gastrointestinal stromal tumors by means of imaging: A systematic review. Diagnostics12, 2722 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang, L. et al. Non-Gaussian diffusion imaging with a fractional order calculus model to predict response of gastrointestinal stromal tumor to second-line sunitinib therapy. Magn. Reson. Med.79, 1399–1406 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang, L., Zhang, D., Zheng, T., Liu, D. & Fang, Y. Predicting the progression-free survival of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after imatinib therapy through multi-sequence magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom. Radiol.49, 801–813 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revheim, M. et al. Multimodal functional imaging for early response assessment in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Acta. Radiol.63, 995–1004 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCague, C. et al. Introduction to radiomics for a clinical audience. Clin. Radiol.78, 83–98 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu-Hai, W. et al. Prediction of recurrence-free survival and adjuvant therapy benefit in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on radiomics features. Radiol. Med. (Torino)127, 1085–1097 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang, L. et al. Mri texture-based models for predicting mitotic index and risk classification of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging.53, 1054–1065 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, X. et al. Postoperative adjuvant imatinib therapy-associated nomogram to predict overall survival of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Front. Med.9, 777181 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, J. et al. Ct Features combined with recist 1.1 criteria improve progression assessments of sunitinib-treated gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Eur. Radiol.34, 3659–3670 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dovrou, A. et al. A segmentation-based method improving the performance of N4 bias field correction On T2Weighted Mr imaging data of the prostate. Magn. Reson. Imaging101, 1–12 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trojani, V., Bassi, M. C., Verzellesi, L. & Bertolini, M. Impact of preprocessing parameters in medical imaging-based radiomic studies: A systematic review. Cancers16, 2668 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raza, M. S. & Qamar, U. Practical Data Science with Weka 393–448 (Springer International Publishing AG, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, W. et al. Comparing three-dimensional and two-dimensional deep-learning, radiomics, and fusion models for predicting occult lymph node metastasis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma based On Ct Imaging: A multicentre, retrospective. Diagnostic Study. Eclinicalmedicine67, 102385 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, L. et al. Value of a combined magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics-clinical model for predicting extracapsular extension in prostate cancer: A preliminary study. Transl. Cancer Res.12, 1787–1801 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zwanenburg, A. Standardisation and harmonisation efforts in quantitative imaging. Eur. Radiol.33, 8842–8843 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhassan, S. et al. Cfs-Ae: Correlation-Based feature selection and autoencoder for improved intrusion detection system performance. J. Internet Services Info. Secur.14, 104–120 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, P. et al. Machine learning models predicts risk of proliferative lupus nephritis. Front. Immunol.15, 1413569 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue, A. et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A comprehensive radiological review. Jpn. J. Radiol.40, 1105–1120 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu, Q. et al. Texture analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient maps: Can it identify nonresponse to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for additional radiation therapy in rectal cancer patients?. Gastroenterol. Rep.12, goae035 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jing, G. et al. Predicting mismatch-repair status in rectal cancer using multiparametric mri-based radiomics models: A preliminary study. Biomed Res. Int.2022, 1–11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao, H. et al. Mri-Based radiomics models for predicting risk classification of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Front. Oncol.11, 631927 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, L. et al. Deep learning and radiomics to predict the mitotic index of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on multiparametric Mri. Front. Oncol.12, 948557 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitrovic-Jovanovic, M. et al. The utility of conventional Ct, Ct perfusion and quantitative diffusion-weighted imaging in predicting the risk level of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: A prospective comparison of classical Ct features, Ct perfusion values, apparent diffusion coefficient and intravoxel incoherent motion-derived parameters. Diagnostics12, 2841 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, Y. et al. Prediction of Ki-67 expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors using radiomics of plain and multiphase contrast-enhanced Ct. Eur. Radiol.33, 7609–7617 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du, J., Yang, L., Zheng, T. & Liu, D. Radiomics-Based predictive model for preoperative risk classification of gastrointestinal stromal tumors using multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging: A retrospective study. Radiologie64, 166–176 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, J. et al. Comparison of Mri and Ct-Based radiomics and their combination for early identification of pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced gastric cancer. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging58, 907–923 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng, M. et al. Comparison of Mri and Ct based deep learning radiomics analyses and their combination for diagnosing intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Sci. Rep.15, 9629 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, P. et al. Preoperative Ct-based radiomics and deep learning model for predicting risk stratification of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Med. Phys.51, 7257–7268 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rengo, M. et al. Development and validation of artificial-intelligence-based radiomics model using computed tomography features for preoperative risk stratification of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Pers. Med.13, 717 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie, Y. et al. Different radiomics models in predicting the malignant potential of small intestinal stromal tumors. Eur. J. Radiol. Open13, 100615 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barat, M. et al. Ct and Mri of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: New trends and perspectives. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J.75, 107–117 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer, S. et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients with Gist Undergoing Metastasectomy in the Era of Imatinib – Analysis of Prognostic Factors (Eortc-Stbsg Collaborative Study). Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (Ejso).40, 412–419 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.