Abstract

The transcription of the Escherichia coli fis gene is strongly activated during the outgrowth of cells from stationary phase. The high activity of the promoter of the fis operon requires the transcription factor IHF. Previously, we identified a divergent promoter, div, located upstream of the fis promoter. In this study we demonstrate that at least two additional promoters, designated fis P2 and fis P3, are located in the control region of the fis operon. The fis P2 and div promoters overlap completely, whereas fis P3 and div P are arranged as face-to-face divergent promoters. We show that the div and the tandem fis promoters counterbalance each other, such that their activity is kept on a lower than potentially attainable level. Furthermore, we demonstrate an unusual activation mechanism by IHF, involving a coordinated shift in the balance of promoter activities. We infer that these coupled promoters represent a regulatory module and propose a novel ‘dynamic balance’ mechanism involved in the transcriptional control of the fis operon.

Keywords: activation/divergent promoter/fis/IHF/tandem promoters

Introduction

The transcription initiation regions of bacterial genes and operons often contain multiple promoters (for a recent review see Opel et al., 2001). Although the requirement for this organization is not always obvious, in many cases it is apparent that the coupling of multiple promoters to a single operon increases the flexibility in the adjustment of gene expression to particular growth conditions. Notably, such arrangments are often found in regulatory regions of genes with pleiotropic functions. For example, the rRNA operons contain two tandem promoters, one of which is constitutively expressed, whereas the other is strongly activated on nutritional shift-up to enable rapid cell growth (Sarmientos et al., 1983; Gourse et al., 1986; Liebig and Wagner, 1995). Of the two tandem promoters driving the expression of the crp gene coding for the global transcriptional regulator, CRP, only one requires DNA negative supercoiling and is subject to stringent control (González-Gil et al., 1998; Johansson et al., 2000). Four of the five tandem promoters in the cydAB operon involved in oxygen regulation are differentially utilized in response to changes in oxygen availability (Govantes et al., 2000). Finally, the tandem promoters of the topA gene involved in the homeostatic control of DNA supercoiling utilize multiple initiation σ factors in adaptation to different growth conditions (Qi et al., 1997).

Furthermore, depending on their arrangement, the multiple promoters themselves can interact with each other in different ways. One such example is topological coupling between divergent promoters, which is explained by the twin-supercoiled domain model of Liu and Wang (1987). In this model, the frictional drag of transcribing polymerase induces a downstream domain of positive supercoiling and an upstream domain of negative supercoiling. The latter facilitates DNA untwisting and thus increases the initiation rate of an upstream promoter (for review see Lilley, 1997). However, if the divergent promoters overlap each other, they can interfere, causing repression (Aiba, 1983; Hanamura and Aiba, 1991). Promoter interference can also occur with tandem promoters when a high initiation frequency of an upstream promoter ‘occludes’ a downstream promoter (Adhya and Gottesman, 1982; Zhang and Bremer, 1996; for review see Goodrich and McClure, 1991). It is conceivable that these various interactions between closely spaced promoters, especially when coupled to selective effects of transcription factors, have a potential for assembling regulatory circuits.

FIS is a pleiotropic regulator involved in the coordination of cellular metabolism with DNA topology during adaptation of cells to rapid growth conditions (Nilsson et al., 1992; González-Gil et al., 1996; Schneider et al., 1999). Recently, we identified a divergent promoter, div, in the upstream region of the promoter of the fis operon (Nasser et al., 2001). The transcription of fis increases sharply on the outgrowth of cells from stationary phase and then decreases steeply in mid-exponential phase (Ball et al., 1992; Ninnemann et al., 1992), whereas the div promoter activity declines on activation of fis expression. The div promoter is not associated with any meaningful ORF and interferes with fis transcription both in vitro and in vivo, but the detailed mechanism of this interference is not understood.

In this study, we demonstrate that the regulatory region of the fis operon contains, in addition to previously characterized fis and div promoters, at least two tandem promoters, P2 and P3, transcribing in the fis direction. We show that the tandem fis promoters respond coordinately to suboptimal transcription conditions in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the div and the tandem fis promoters are tightly coupled and their activities can be coordinately changed by a single transcription factor. Our findings suggest the involvement of a module of multiple coupled promoters in the transcriptional control of the fis operon. From these data we propose a novel ‘dynamic balance’ mechanism of transcription regulation.

Results

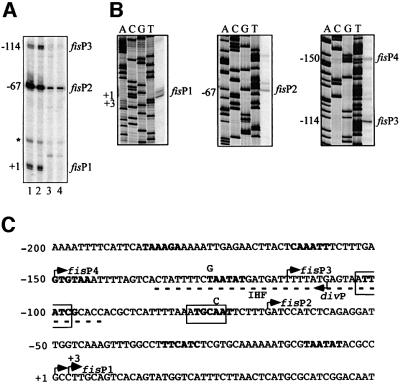

By analysing transcription of the fis operon in exponentially growing CSH50 cells, we detected two messages in addition to the previously described transcript (Figure 1A; Ball et al., 1992; Ninnemann et al., 1992). These additional transcripts were also growth phase regulated and their 5′-ends were mapped to positions –67 and –114 with respect to the transcription initiation start point of the fis operon at +1 (Figure 1C). The transcript starting at –67 was most abundant and already highly expressed 5 min after subculturing overnight cultures in fresh medium (the procedure termed hereafter nutritional shift-up). By contrast, the two other transcripts achieved their maximum levels only after 15 min, but all three messages decreased strongly 60 min after the shift-up. To discriminate whether these additional transcripts represent processing products or independent initiation events, in vitro transcription reactions were carried out with the fisP–lacZ fusion construct pWN1, containing the extended fis promoter region from position –308 to +106 (Nasser et al., 2001). By primer extension of the transcription products, three novel messages were detected, two of which (initiating at positions –67 and –114) coincided with those identified in vivo (Figure 1B). We thus infer that at least two tandem promoters initiating at –67 and –114 (denoted P2 and P3, respectively) in addition to the previously identified promoter (hereafter denoted P1) are present in the regulatory region of the fis operon. The deduced fis P2 promoter region overlaps div completely, whereas fis P3 and div are arranged as face-to-face divergent promoters with their initiation sites separated by 5 bp (Figure 1C).

Fig. 1. The upstream region of the fis promoter contains additional transcription initiation sites. (A) Primer extension analysis of total RNA from CSH50 cells using the primer ORF13′. Lanes 1, 2, 3 and 4 correspond to the products obtained with RNAs extracted from cells 5, 15, 60 and 150 min after the shift-up. fis P1 corresponds to the previously described promoter. The novel transcripts initiating at –67 and –114 are indicated. The minor transcript indicated by an asterisk is probably a processing product and has not been studied further. (B) Primer extension analysis of the transcripts produced from pWN1 in vitro. The concentration of RNAP in these reactions was 25 nM. The primer extension products corresponding to fis P1, fis P2 and fis P3 + fis P4 are indicated. The dideoxy sequencing ladder performed with the same primers on pWN1 is shown. (C) Sequence of the fis promoter region. The dotted line indicates the binding region for IHF. The RNAP binding elements (–10 and –35 hexamers) of the div promoter are boxed, those of the fis promoters are indicated in bold. The start points of transcription are shown by broken arrows. The ‘down’ mutations introduced in the RNAP recognition elements of div (–35 hexamer, –75A/C) and fis P3 (–10 hexamer, –126T/G) promoters are indicated by C and G above the substituted A and T, respectively.

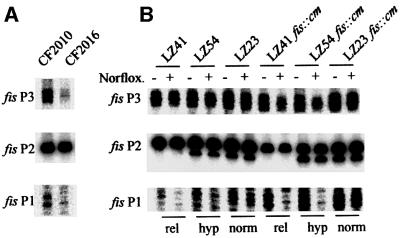

To test whether these multiple promoters may have distinct physiological roles, we used two simple approaches that change the transcription conditions of cellular promoters in vivo. It has been shown that the fis P1 promoter is subject to stringent control (Ninnemann et al., 1992). We therefore analysed the tandem fis promoter activities in the strain CF2010 and its derivative CF2016, which carries a polymerase altered in its interaction with stringent promoters by mutation (Zhou and Jin, 1998). Primer extension analysis of RNA isolated from exponentially growing cells demonstrated that in the CF2016 strain with ‘stringent’ polymerase, only fis P2 was transcribed efficiently, whereas fis P1 and fis P3 activities were substantially reduced (Figure 2A). The fis P1 promoter is also very sensitive to changes in negative superhelical density of DNA (Schneider et al., 2000). We therefore measured next the amount of different fis P transcripts in isogenic strains LZ54, LZ41 and LZ23, in which addition of the topoisomerase inhibitor norfloxacin allows the establishment of different overall negative superhelical densities in vivo (Zechiedrich et al., 1997; Schneider et al., 2000). We found that both the relaxation and hypernegative supercoiling of DNA reduced the fis P1 and fis P3 transcription to different extents, whereas the activity of fis P2 remained high (Figure 2B). Essentially similar dependence of promoter activity on superhelical density was observed in fis mutant derivatives of these strains (Figure 2B), ruling out the role of FIS autoregulation in this effect (Ball et al., 1992). We thus infer that the tandem fis promoters respond coordinately to the impairment of transcription conditions in vivo: fis P1 and P3 promoters decrease with altered polymerase and suboptimal template quality, whereas P2 remains largely insensitive to these changes.

Fig. 2. Effects of the altered quality of RNAP and of template DNA topology on the activity of the chromosomal fis promoters in vivo. (A) Chromosomal fis promoter activities in the isogenic strains C2010 and C2016. The latter strain carries the ‘stringent’ polymerase with rpoB114 mutation (Zhou and Jing, 1998). (B) Chromosomal fis promoter activities at different overall DNA superhelical densities in strains with mutant gyrase and/or topoisomerase IV alleles. Addition of norfloxacin leads to relaxation of DNA (rel) in strain LZ54 and its fis derivative, and to hypernegative supercoiling (hyp) in strain LZ54 and its fis derivative, whereas the superhelical density in strains LZ23 and LZ23 fis::cm remains largely unaffected (norm). Norfloxacin was added for 5 min to strains grown in early exponential phase (OD = 0.1). The transcripts originating from fis P1, P2 and P3 were detected as in Figure 1A. The superhelicity of DNA was estimated from the overall superhelical densities of plasmids isolated from the respective strains (Schneider et al., 2000).

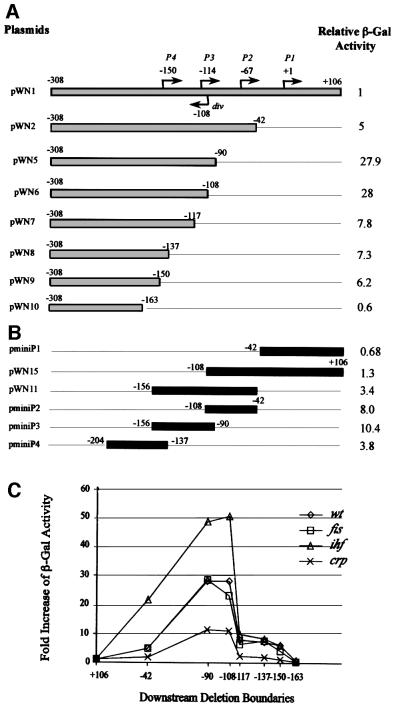

To gain more insight into the regulation of tandem fis promoters, we performed deletion analyses using the fisP–lacZ fusion construct pWN1. A deletion to position –42, removing the fis P1 promoter, led to a 5-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity (pWN2 in Figure 3A), consistent with high activity of fis P2 observed in vivo. However, removal of the fis P2 promoter by deletion to positions –90 (pWN5) or –108 (pWN6) led to a further >5-fold increase, such that in total β-galactosidase activity increased 28-fold compared with that of the fis extended promoter (pWN1). Notably, this latter deletion also removes the overlapping div promoter (see Figure 1C). Further deletions to positions –117 (pWN7), –137 (pWN8) and –150 (pWN9) all decreased β-galactosidase activity by 3- to 4-fold, but it was still substantially higher than that produced from the fis extended promoter. Only after deletion to position –163 (pWN10), which removes the putative upstream promoter initiating at –150 (denoted hereafter as P4; see Figure 1B and C), did the β-galactosidase activity decrease strongly, and further deletions did not change these low levels of β-galactosidase produced (data not shown). Thus, the successive deletions to positions –42 and –90/–108, removing first the fis P1 and then the overlapping P2/div promoter regions, derepress the remaining fis promoters.

Fig. 3. Deletion analysis of the fis–lacZ promoter fusion. (A) The extended promoter fusion construct pWN1(–308 to +106) and deletion mutants are represented by gray horizontal bars. The β-galactosidase activity of pWN1 is normalized to 1. The broken arrows indicate transcription initiation sites. The downstream deletion boundaries are indicated on the right side of the horizontal bars and correspond to the fis–lacZ fusion junctions. The relative β-galactosidase activities (ratios) of overnight cultures containing corresponding lacZ fusion constructs are indicated. The ratios obtained in three separate experiments varied by <15%. (B) The relative β-galactosidase activities of the minimal promoter constructs and constructs containing two contiguous promoters. Indications and normalization are as in (A). (C) Relative β-galactosidase activities of deletion mutants in different genetic backgrounds. The β-galactosidase activity of the extended fis promoter fusion construct pWN1(–308 to +106) is normalized to 1 separately for each mutant strain, allowing comparison of relative activities of deletion mutants within, but not between, the different genetic backgrounds.

Since fis expression is known to be modulated by three DNA architectural proteins, IHF, CRP and FIS itself (Ball et al., 1992; Ninnemann et al., 1992; Pratt et al., 1997; Nasser et al., 2001), the differences in relative β-galactosidase activities of deletion mutants could be explained by binding of these regulatory proteins. We therefore analysed the deletion mutants in the fis, ihf and crp mutant cells. We observed that although the inactivation of these regulators clearly modulated the relative β-galactosidase activities of deletion mutants, the overall pattern remained essentially unchanged (Figure 3C). These data suggest that the pattern obtained reflects intrinsic differences in the activities of deletion mutants and is not determined uniquely by these regulatory proteins.

To evaluate the relative strengths of tandem fis promoters, we created minimal promoter–lacZ fusion constructs by cloning the sequences from +106 to –42 (pminiP1), from–42 to –108 (pminiP2; we note that this construct also contains the overlapping div promoter), from –90 to –156 (pminiP3) and also from –137 to –204 (pminiP4), upstream of the lacZ gene. Consistent with deletion analyses, with the exception of fis P1 all these minimal promoter constructs demonstrated higher β-galactosidase activities than the extended fis promoter (Figure 3B). Notably, both the P2 and P3 promoters were more active on minimal constructs than on the construct pWN11 comprising the regions of overlapping fis P2/div and fis P3 promoters. Likewise, the P2 promoter was more active on the minimal construct than on the construct pWN15 comprising the regions of overlapping fis P2/div and fis P1 promoters. This indicates the possibility of competitive interactions between these promoters.

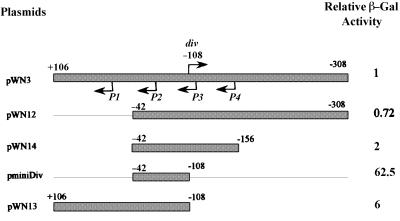

To understand the role of the div promoter in these interactions, we carried out deletion analyses using the construct pWN3, which is identical to pWN1 but contains the extended fis promoter (+106 to –308) region in opposite orientation with respect to the lacZ reporter gene, thus allowing β-galactosidase activity produced from the div promoter to be measured. Deletion of the region between +106 and –42 containing the fis P1 promoter had only a small, if any, effect on β-galactosidase activity produced from the div promoter (Figure 4, compare pWN3 and pWN12). Nevertheless, the same deletion substantially increased div P activity in the absence of the fis P3 and P4 promoters (compare pWN13 with pminiDiv), suggesting that the effect of the +106 to –42 region is context dependent. Deletion of the div downstream region comprising the fis P4 promoter led to a >2-fold increase in div P activity (compare pWN12 and pWN14), whereas deletion of the fis P3 promoter region led to an additional 30-fold increase (compare pWN14 and pminiDiv), indicating that the P3 promoter exerts a strong negative effect on div P activity. Again, in the presence of the region between +106 and –42, comprising the fis P1 promoter and downstream sequences, this increase was less pronounced (compare pWN3 and pWN13). Thus, the negative effects exerted by both the downstream and upstream regions on β-galactosidase activity produced from the div promoter are context dependent. We infer that in the context of the extended fis promoter (+106 to –308), the major negative effect is exerted by the P3 promoter since it represses, though to different extents, the div promoter both in the presence and absence of the region comprising fis P1 (compare pWN3 with pWN13, and pWN14 with pminiDiv).

Fig. 4. Deletion analysis of the div–lacZ promoter fusion pWN3. The β-galactosidase activity of pWN3 is normalized to 1. The denotions are as in Figure 3A. The ratios obtained in three experiments varied by <15%.

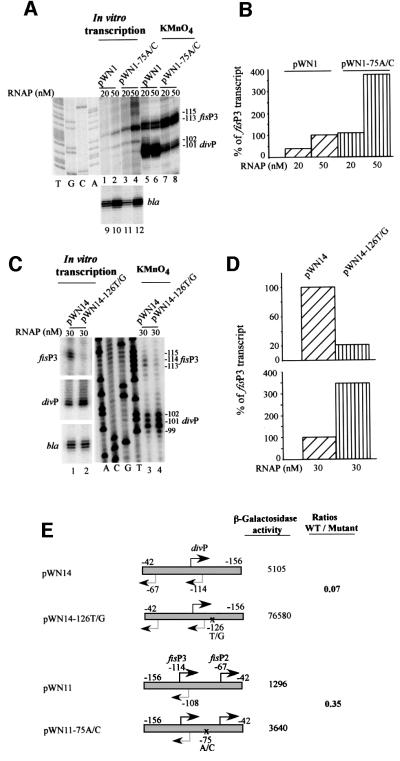

Taken together, our deletion analyses presented in Figures 3 and 4 indicate that the face-to-face fis P3 and div promoters may counteract each other. This predicts that inactivation of one of these promoters (e.g. by mutation) should increase the activity of the other. To test this hypothesis, we used a construct carrying a ‘down’ mutation in the –35 element of the div promoter (–75A/C), which abolishes div transcription in vitro (Nasser et al., 2001). We observed that this mutation increased the permanganate reactivity of the fis P3 promoter DNA, indicative of RNA polymerase (RNAP) open complex formation and also fis P3 transcription in vitro (Figure 5A and B). In turn, we next introduced a ‘down’ mutation in the putative –10 region of the P3 promoter (a T to G transversion at position –126, see Figure 1C) to impair its activity. As expected, this mutation decreased the opening and transcription of the P3 promoter in vitro, whereas both the opening and the transcriptional activity of the div promoter were increased (Figure 5C and D). Similar reciprocal effects of these promoter mutations were observed in vivo (Figure 5E). We thus infer that the div and fis P3 promoters counterbalance each other such that their activity is kept on a lower than potentially attainable level.

Fig. 5. Analysis of the mutual effects of ‘down’ mutations in the RNAP recognition elements of the fis P3 and div promoters in vitro and in vivo. (A) In vitro effect of the ‘down’ mutation in the –35 hexamer of the div promoter on the fis P3 promoter opening and transcription. Lanes 1 and 2, transcription of fis P3 from pWN1; lanes 3 and 4, transcription of fis P3 from pWN1-75A/C; lanes 5 and 6, permanganate reactivity of the fis P3 and div promoters on pWN1; lanes 7 and 8, permanganate reactivity of the fis P3 and div promoters on pWN1-75A/C; lanes 9, 10 and 11, 12, transcription of the bla promoter from pWN1 and pWN1-75A/C respectively (an internal control). The concentration of RNAP is indicated. The dideoxy sequencing ladder performed with the same primer on pWN1 is shown on the left. (B) Quantitative analysis of fis P3 activity on pWN1 and pWN1-75A/C. The data were normalized to the value obtained for pWN1 at 50 nM RNAP, which was set at 100%. (C) In vitro effect of the ‘down’ mutation in the –10 element of the fis P3 promoter on div promoter opening and transcriptional activity on pWN14 and pWN14-126T/G. The concentration of RNAP is indicated. The dideoxy sequencing ladder performed with the same primer on pWN14 is shown. (D) Quantitative analysis of div activity on pWN14 and pWN14-126T/G. The data were normalized to the value obtained for pWN14 at 30 nM RNAP, which was set at 100%. (E) In vivo effects of ‘down’ mutations in the RNAP recognition elements of the fis P3 and div promoters. Representation and indications are as in Figure 3A. Only those promoters that contribute to the measured β-galactosidase activities are indicated. The point mutations are indicated by crosses on the top or bottom strand of DNA. The ratios (WT/Mutant) obtained in three separate experiments varied by <15%.

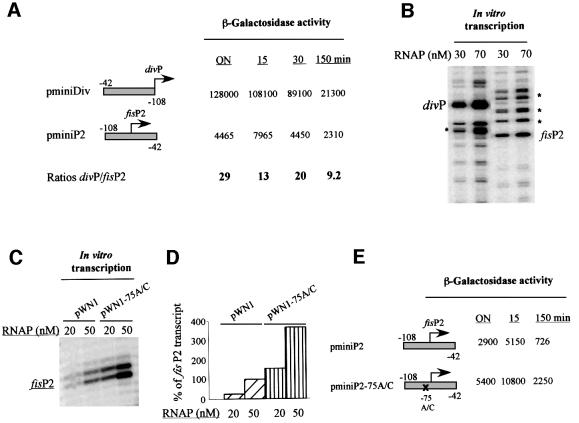

We note, however, that the β-galactosidase activities measured from pWN11 and pWN11-75A/C (Figure 5E) actually reflect the contribution of both the fis P3 and P2 promoters. To address the question of the relationships between the overlapping div and fis P2 promoter activities, we first measured their relative activities using the same minimal DNA fragment comprising the overlapping fis P2 and div promoters (–42 to –108) inserted in two opposite orientations upstream of the lacZ gene. The β-galactosidase measurements showed that, depending on the growth stage, the activity of the div promoter exceeded that of fis P2 by 9- to 29-fold (Figure 6A). A comparison of div P and fis P2 transcriptional activities in vitro showed that the div promoter is also a stronger promoter in vitro (Figure 6B). Furthermore, we found that on the extended promoter template pWN1, the ‘down’ mutation of div P increases P2 activity in vitro (Figure 6C and D) and in vivo (Figure 6E), consistent with competitive interactions between these overlapping promoters.

Fig. 6. Comparative analysis of the fis P2 and div promoters. (A) The β-galactosidase activities of pminiDiv and pminiP2 were measured in overnight cultures (ON) and 5, 30 and 150 min after the shift-up. The ratios (div P/fis P2) are shown below. (B) In vitro transcription of the fis P2 and div promoters from pWN11 and pWN14 was monitored by primer extension using the same radiolabelled primer in order to directly compare the respective promoter activities. The concentrations of RNAP used in the reactions are indicated. Note the additional transcripts (asterisks) increasing with RNAP concentration and presumably due to aberrant initiation within the presumably flexibile DNA stretch of ∼40 bp in length containing the overlapping P2 and div promoters. (C) The effect of ‘down’ mutation in div P on the transcription of the fis P2 promoter. The constructs used to monitor transcription in vitro and the RNAP concentrations are indicated. (D) Quantitative analysis of fis P2 activity on pWN1 and pWN1-75A/C. The data were normalized to the value obtained for pWN1 at 50 nM RNAP, which was set at 100%. (E) The β-galactosidase activities of pminiP2 and pminiP2-75A/C carrying a ‘down’ mutation in div P. The abbreviations are as in (A).

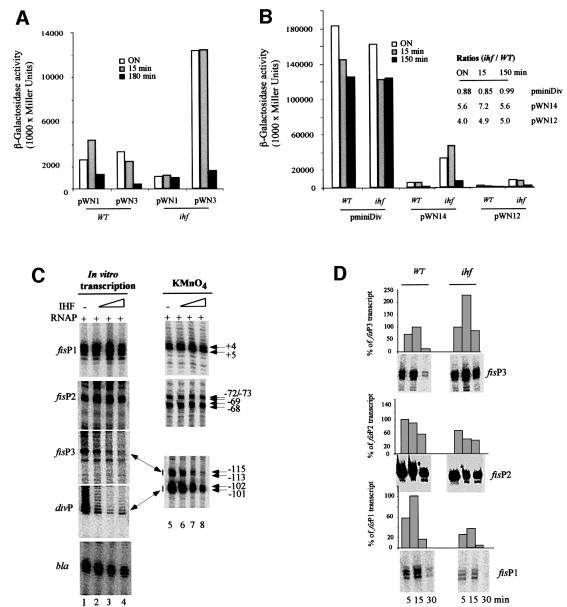

Since fis P2 is the strongest among the tandem fis promoters in vivo, we asked how this high activity could be maintained in the presence of limitations imposed in the context of extended fis promoter region. Previous studies implicated IHF in the maintenance of high levels of fis expression (Pratt et al., 1997). We therefore investigated the activating effect of IHF both in vivo and in vitro. As expected, in mutant strains lacking IHF, the β-galactosidase activity produced by the extended fis promoter construct pWN1 decreased. However, the β-galactosidase activity produced by the div promoter construct pWN3 increased by >5-fold, suggesting that IHF represses div (Figure 7A). Furthermore, we found that IHF repressed div P on pWN12 and pWN14 but not on the pminiDiv construct, implicating the sequences between –108 and –156 in mediating repression (Figure 7B). The in vitro transcription and permanganate reactivity assays carried out using pWN1 demonstrated that addition of IHF not only activates the fis P1, as expected, but also the fis P2 promoter, whereas both P3 and div promoters were strongly repressed (Figure 7C). Consistent with this finding, elevated levels of fis P3 and lowered amounts of fis P2 and fis P1 transcripts were detected in ihf mutant cells in comparison to wild type in vivo (Figure 7D). From these data, we infer that IHF is involved in the maintenance of the high activity of the fis P2 promoter in vivo.

Fig. 7. Effect of IHF on the fis and div promoter activities. (A) The β-galactosidase activities of pWN1 and pWN3 measured in the cultures of CSH50 and CSH50Δihf cells. The β-galactosidase activities of overnight (ON) cultures and 15 and 180 min after the shift-up are shown. (B) The β-galactosidase activities of pminiDiv, pWN14 and pWN12 measured in the cultures of CSH50 and CSH50Δihf cells. The activity ratios (ihf/WT) and the corresponding constructs are indicated. (C) The effect of IHF addition on promoter opening and transcription in vitro. The concentration of RNAP was 20 nM; the concentration of IHF was 2 nM in lanes 2 and 6, 5 nM in lanes 3 and 7, and 50 nM in lanes 4 and 8. The transcription of the fis P1, P2, P3 and bla (used as an internal control) promoters was evaluated from pWN1; the div promoter transcription was measured from pWN14. (D) Primer extension of mRNA isolated from CSH50 and CSH50Δihf cultures 5, 15 and 30 min after the shift-up. The reactions were carried out as in Figure 1A. The amount of the transcripts was normalized to the maximal values obtained in wild-type cells for fis P1 (15 min), fis P2 (5 min) and fis P3 (15 min), which were each set at 100%.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is the identification of a module of multiple coupled promoters in the regulatory region of the fis operon, implying that the control of fis expression is much more complex than anticipated. Although we have not explicitly addressed the particular physiological roles of the tandem fis promoters described here, they respond coordinately to deviations of transcription conditions from optimum in vivo. Furthermore, the balance of their activities is coordinately switched by the transcriptional activator of fis expression, IHF. We propose that this organization of multiple promoters in a coupled module potentially provides for a factor-independent mechanism of transcription regulation by RNAP itself. We denote the latter as a ‘dynamic balance’ regulation.

The fis transcription unit contains at least three tandem promoters

Of the three fis promoters identified besides P1 (P2, P3 and P4), the relevance of P4 in vivo remains unclear and therefore we focused primarily on the P2 and P3 promoters. The putative –35 and –10 elements of the P3 promoter, GTGTAA and TAATAT, are separated by a suboptimal 18 bp spacer and deviate from the consensus –35 (5′-TTGACA-3′) and –10 (5′-TATAAT-3′) elements in five out of 12 positions (Figure 1C; Lisser and Margalit, 1993). Notably, the –10 element of P3 is identical to that of fis P1. Furthermore, both these promoters use a less favourable pyrimidine nucleotide for initiation (Liu and Turnbough, 1994; Walker et al., 1999). It is thus possible that these similarities account for the apparent coherence in the response of P1 and P3 promoters to the alterations of DNA superhelical density and RNAP quality observed in vivo. We note, however, that one of the major determinants of both supercoiling sensitivity and stringent control, the GC-rich discriminator sequence (Travers, 1980; Ninnemann et al., 1992; Figueroa-Bossi et al., 1998; Schneider et al., 2000), is present in fis P1 but absent in fis P3. The putative –35 and –10 hexamers of the fis P2 promoter, TTATCG and TGCAAT, are also separated by an 18 bp spacer and deviate from the consensus in five out of 12 positions. However, the fis P2 promoter is largely insensitive to negative effects of suboptimal superhelical density and altered polymerase quality. This promoter also shows an extensive DNA untwisting in the AT-rich discriminator region on binding RNAP (T-68, T-69, T-72 and T-73; Figure 6C) and, in contrast to P1 and P3, uses a favourable purine nucleotide for initiation. Another peculiarity is that the –10 element of P2 almost coincides (in five out of six positions) with the –35 element of overlapping div promoter and, vice versa, the –10 element of div P coincides (in five out of six positions) with the –35 element of P2 (Figure 1C). Given the separation between initiation sites of P2 and P3 of ∼4.5 helical turns, this organization places div P face to face with the fis P3 promoter, with their initiation sites separated only by half a helical turn. This unique arrangement of three promoters over a DNA stretch of ∼85 bp prompted us to investigate the interactions between fis P2, fis P3 and div P in more detail.

The div and the tandem fis promoters are coupled

We studied the interactions between the div P and tandem fis promoters in vivo using transcriptional fusions with the lacZ gene on multicopy plasmids. Since the plasmid copy number may vary in different mutant strains, we separately compared the relative promoter activities of deletion constructs within each genetic background. To avoid possible variation due to different mRNA stability dependent on the particular fis (or div) promoter–lacZ junction sequence in the transcriptional fusions (Liang et al., 1998), we verified the critical genetic data either by measuring the transcriptional activity in vitro or from chromosomal fis promoters in vivo. We note that the chromosomal transcripts were detected using a primer complementary to a region in ORF1 upstream of the fis gene and, therefore, their apparent abundances may not reflect their contribution to translatable fis message.

Our genetic analyses revealed that a deletion of the region from +106 to –42 encompassing the fis P1, and a further deletion to –90/–108 encompassing the over lapping P2 and div promoters, both unmask a high activity of the upstream fis promoters. A qualitatively similar pattern was observed in wild type and three mutant strains lacking the known transcriptional regulators of the fis promoter activity, IHF, CRP and FIS itself. This argues that the repression cannot be uniquely ascribed to any of these factors, but rather is modulated by them.

Previous studies indicated that a deletion of the region between +7 and +107 derepresses the minimal fis P1 promoter by ∼2-fold (Pratt et al., 1997). Although this suggests an existence of repressing factor(s) targeting the region between +7 and +107, we cannot exclude the possibility that, in addition, the fis P1 promoter itself could limit the transcription from the upstream P2 promoter to a certain extent. This notion is consistent with the 6-fold lower β-galactosidase activity of the construct pWN15 containing both the P1 and P2 promoters in comparison to the minimal P2 promoter construct pminiP2 (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we have shown here that in the absence of fis P3, the region between +106 and –42 comprising the fis P1 promoter reduces β-galactosidase activity produced from the div promoter 10-fold (Figure 4). These observations are consistent with limitations imposed by the downstream region comprising the fis P1 promoter on both the P2 and div promoters.

The repressing effect exerted by the region between –42 and –90/–108 on the fis P3 promoter is clearly due to the activity of the div promoter, whereas the latter is itself repressed by fis P3. This notion is supported by both our in vivo and in vitro analyses. First, the disruption of the face-to-face arrangement of div and fis P3 promoters substantially increases the β-galactosidase activity of both promoters (Figures 3A and 4). Secondly, the introduction of ‘down’ mutations in the RNAP recognition elements of the div and fis P3 promoters reciprocally increases the RNAP open complex formation and transcription in vitro, suggesting that these two promoters counterbalance each other. Notably, the –75A/C ‘down’ mutation in the –35 region of div P also impairs the match of the fis P2 promoter –10 element to the consensus, yet it increases the activity of P2. One possible explanation is that since div P appears to be much stronger than fis P2, the net effect of the mutation that abolishes div transcription in vitro (Nasser et al., 2001) results in increased P2 activity. Furthermore, in the context of the extended promoter, this mutation also increases the activity of fis P1 (Nasser et al., 2001). Taken together, these data argue for a tight coupling of the div and the tandem fis promoters.

We cannot exclude the possibility that topological coupling is involved in the complex interactions between these multiple promoters. However, while this mechanism easily applies to two gene promoters organized as divergent transcription units (for review see Opel et al., 2001), the organization of divergent promoters in the fis control region is much more complex. Three types of arrangement can be discerned here, including the closely spaced (div and fis P1), overlapping (div and fis P2) and face-to-face (div and fis P3) divergent promoters. Furthermore, in the case of topological coupling, inactivation of one of the promoters is predicted to impair the activity of the coupled promoter (Opel et al., 2001), whereas inactivation of fis P3 activates div P and, vice versa, inactivation of div P activates all of the three fis promoters (this study; Nasser et al., 2001). We think it unlikely that the ‘down’ mutation in div P could have a direct activating effect on all three fis promoters (Goodrich and McClure, 1991), or that activation of one of the tandem fis promoters subsequently activates the others. The observed higher β-galactosidase activities of minimal fis promoters in comparison to constructs containing two contiguous fis promoters (Figure 3B) are rather indicative of competitive interactions. For example, the α-CTD of RNAP bound at P2 could use the AT-rich sequence around the start point of P3 as a proximal UP element (Ross et al., 1993) and thus occlude binding of RNAP at P3.

The ‘dynamic balance’ model

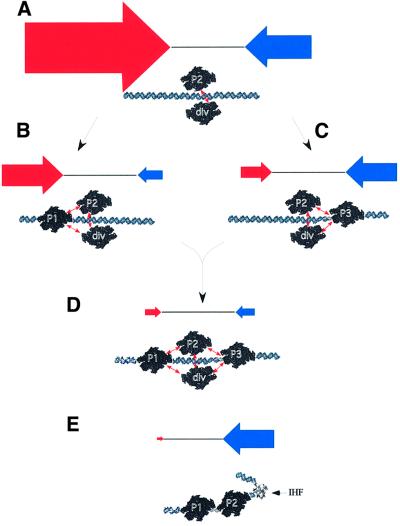

Our data can be explained by a ‘dynamic balance’ mechanism, which implies the assembly of the module of coupled promoters by sequential joining of competing promoter regions. We assume that the basal element of the module is the sequence comprising the overlapping fis P2 and div promoters. The transcription of both these promoters is high, but from our data the div promoter activity exceeds that of P2 by at least by an order of magnitude (Figure 8A). The addition of the fis P1 promoter region to this basal element decreases the activity of both div and P2 promoters by competition and also shifts their balance, yet the div promoter is still transcribed more strongly (Figure 8B). By contrast, addition of the P3 promoter region to the basal element not only decreases the div and P2 promoter activities, but also, by being a strong competitor of div P, shifts the balance in favour of fis transcription (Figure 8C). In the context of the extended promoter, the transcription from the overlapping fis P2 and div promoters is lowest, being counterbalanced by negative effects now exerted by both the P3 and P1 promoter regions (Figure 8D). The model predicts that activation of P1 and P3 should correlate with reduction of the fis P2 activity and, vice versa, high levels of fis gene expression could be maintained from P2 under conditions repressing the fis P1 and P3 promoters. This is exactly what we observe under respectively optimum (Figure 1) and suboptimum (Figure 2) transcription conditions in vivo. This regulation is essentially homeostatic, and also allows a rapid and precise adjustment of fis promoter activities by shifting the dynamic balance.

Fig. 8. Dynamic balance model of regulation of fis operon transcription. (A–D) The sequential joining of promoter regions to the basal element (A) results both in the repression and shifts in the balance of transcription, leading to the establishment of a new dynamic balance in the context of the extended promoter (D). This balance can be perturbed on binding of a transcriptional factor (E), by changes in general transcription conditions or by promoter mutation. The RNAP molecules interacting with fis P1, P2, P3 and div promoters are indicated. The coupling (competitive interactions) between the promoters is indicated by connecting double arrows. Horizontal blue and red arrows indicate the relative strengths of transcription in fis and div directions, respectively. With the exception of (A), the sizes of the arrows within each pair are roughly approximated to values obtained by β-galactosidase assays. For details see the text. (E) Coordinated switch of the fis promoter activities by IHF. In this model, the sharp bend (U-turn) introduced by IHF (Rice et al., 1996) on binding to the site centred at –114 precludes binding of RNAP at fis P3 and div promoters with resultant ‘chanelling’ of transcription towards fis P2 and P1. For details see the text.

Regulation of fis transcription by IHF

The mechanism of activation of fis transcription by IHF appears to be such an example of shifting the balance of relative activities of the fis P3, P2, P1 and div promoters. In line with previous observations, we have found that IHF increases the β-galactosidase activity produced from the fis promoter (Pratt et al., 1997), but, as shown here, concomitantly and strongly represses the div promoter. This latter effect is wholly consistent with the previously observed inverse correlation between the div P and fis P activities during the first 15 min after the nutritional shift-up (Nasser et al., 2001). Furthermore, the effect of IHF on tandem fis promoters is selective, since IHF increases the transcription of fis P2 and P1 but reduces that of fis P3 in vivo. This notion is further reinforced by our in vitro data clearly showing that IHF specifically increases both the opening and transcription of P2 and P1 promoters, but strongly represses those of div and P3. The repression by IHF requires sequences between –108 and –156, consistent with a role for the IHF binding site centred at –114 shown to be involved in activation of fis transcription (Pratt et al., 1997). This IHF binding site overlaps the initiation start points and –10 regions of both the fis P3 and div promoters (Figure 1C). Repression of RNAP binding by interaction of IHF with a site overlapping the promoter has also been observed with bacteriophage λ pcin promoter (Griffo et al., 1989). We propose that bending of DNA by binding of IHF at this site may preclude the interaction of polymerase with both the P3 and div promoters, supporting early activation of P2 (Figure 8E). The activation could then be a result of both the relief of limitations imposed by div P and fis P3 on P2, and stabilization of favourable local geometry for binding of RNAP at the P2 and, perhaps, P1 promoters. Thus, IHF appears to ‘channel’ transcription by shifting the balance, as predicted by the dynamic balance mechanism. We emphasize, however, that the regulation of fis expression is a complex phenomenon subject to growth phase-dependent and stringent control, and involving in addition to IHF the effects of other factors such as FIS itself, CRP, the superhelical density of DNA and, perhaps, NTP pools (this study; Ball et al., 1992; Ninemann et al., 1992; Pratt et al., 1997; Walker et al., 1999; Schneider et al., 2000; Nasser et al., 2001).

There are many examples of the organization of gene regulatory regions as coupled overlapping and face-to-face divergent promoters, which in concert with transcription factors, allow balanced gene expression (Aiba, 1983; Jagura-Burdzy and Thomas, 1997; González-Gil et al., 1998; Rhee et al., 1999; for review see Opel et al., 2001). However, the div promoter located in the fis control region is not associated with any meaningful ORF, a situation reminiscent of the role of the CRP-dependent divergent promoter involved in the complex control of crp expression and suggesting an entirely regulatory function (Aiba, 1983; Hanamura and Aiba, 1991). Notably, the tandem crp P1 and P2 promoters differ in their sensitivity to superhelical density and stringent control (González-Gil et al., 1998; Johansson et al., 2000). It is conceivable that such modules of multiple coupled promoters represent a transcription factor-independent regulation mechanism mediated by interactions between RNAP molecules. Such mechanisms could have co-evolved with factor-dependent regulation. Alternatively, the control by transcription factors could have been superimposed on primordial RNAP-dependent homeostatic regulation mechanisms in the course of evolution.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and enzymes

Chemicals and enzymes used in this work were obtained from commercial sources.

Bacterial strains, growth conditions and plasmids

Bacterial strains used in this study were Escherichia coli K12 derivatives. The genotype of CSH50 is ara Δ(lac pro) thi rpsL (Miller, 1972). The construction of CSH50 Δfis is described elsewhere (Koch et al., 1988). The strain CSH26 Δihf was kindly provided by C.Koch. Strains CF2010 and CF2016 are MG1655 derivatives, and were kindly provided by M.Cashel. Strains LZ41 (parCK84kan) and LZ54 (gyrAL834 zei-3143::Tn10kan) are RS2λ [pyrF287 nirA trpR72 iclR7 gal25 rpsL195 topA10 λ(P80xis1 cI857)] derivatives. Strain LZ23 (gyrAL834 zei-723::Tn10) is a C600 (F- thr-1 leu-6 thi-1 lacY1 supE44 tonA21A) derivative. The strains with mutant gyrase and/or topoisomerase IV alleles were kindly provided by L.Zechiedrich and were grown at 30°C. The fis– derivatives of LZ41, LZ54 and LZ23 were obtained by phage P1 transduction using the strain CSH50fis:cm described in González-Gil et al. (1998). All strains were grown in 2× YT medium (16 g of tryptone, 10 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl per litre, pH 7.4). Single colonies were isolated on YT plates (8 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, 15 g of agar per litre).

The constructs pWN1, pWN1-75A/C and pWN3 are described by Nasser et al. (2001). pWN1 (fis promoter–lacZ fusion) contains a fis promoter fragment encompassing positions –308 to +106 (relative to the fis operon transcriptional start at +1). pWN1-75A/C contains the same fis promoter fragment as pWN1 in which an A-to-C base substitution was introduced at position –75 (see Figure 1C) by a two-step PCR method. pWN3 (div promoter–lacZ fusion) contains the same DNA fragment as pWN1 inserted in opposite orientation with respect to the lacZ reporter gene (+106 to –308). The fragments comprising different deletions of the fis and div promoter regions, and their respective constructs are represented in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. All these fragments were PCR amplified and cloned in EcoRI–NruI sites of ptyrTlac (Schneider et al., 1999). Thereby, the tyrT promoter of ptyrTlac was replaced by these fis or div promoter DNA sequences. To construct pWN14-126T/G, the primers pdiv-126T/G comprising positions –156 to –117 and containing a T-to-G base substitution at –126 on the top strand (5′-GCCTATCGCGACTTTGAGTGTAAATTTTAGTCACTATTTTCGAATATGATG-3′) (NruI site underlined) and pfis-42EcoRI (5′-CGGAATTCTTTGACCAATCCTCTGAG-3′) (EcoRI site underlined) were used for the PCR reactions on the pWN1 template. The resulting PCR product was cloned in EcoRI–NruI sites of ptyrTlac.

Proteins

RNAP was from Boehringer Mannheim. Purified IHF was kindly provided by Dr F.Boccard.

RNA isolation and primer extension analysis

Total E.coli RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNAeasy kit. The concentration of RNA in different samples was detected spectrophotometrically, normalized for each sample and verified on a reference gel, using rRNA as loading control. The primers used for specific detection of mRNA were 5′ end-labelled ORF13′ (5′-AGGTCTGTCTGTAATGCCAG-3′), pfis+60 (5′-CTGAGCTGATATTGTCCG-3′) and pfis+9 (5′-CTGCAAGGCGGCGTATATTAC-3′), which anneal to mRNA molecules at positions –106 to –87, +60 to +43 and +9 to –12 relative to the fis operon transcriptional start, respectively. The radiolabelled primers (0.4 pmol) were annealed with 5–10 µg of RNA and reverse transcription was performed with Superscript II (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The extension products were resolved on a 6% sequencing gel and visualized by phosphoimaging. The length of the transcripts was identified using the corresponding dideoxy sequencing reactions as a reference.

In vitro transcription

Supercoiled plasmids were used for in vitro transcription and primer extension reactions according to Lazarus and Travers (1993). The mRNA obtained after in vitro transcription was divided into equal parts and used for primer extension by Superscript II (Gibco-BRL) with radioactively end-labelled primers for detection of different fis P, the div P and bla transcripts. The transcription of the fis promoters from pWN1 was evaluated by primer extension using the primers ORF13′ for fis P1 and fis P2, and fis+9 for fis P3 and P4; the primer Δ61+90 (5′-AAGTGCCACCTGACGTCTAAG-3′) for div P; and the primer bla3B4 (5′-CAGGAAGGCAAAATGCCGC-3′) for bla. The transcripts generated from div and fis P3 on pWN14 were detected by primer extension using the primers lacZ+473′ (5′-GCAGGGTAGCCAAATGC-3′) and Δ61+90, respectively. The latter primer was used to directly compare the amount of mRNA transcribed from div and P2 promoters on pWN11 and pWN14, respectively. After primer extension, the samples were loaded onto 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The transcripts were identified and visualized as described above and quantified using ImageQuant software. The data derived from at least three independent experiments were averaged before normalization.

Potassium permanganate reactivity assay

The reactions for potassium permanganate reactivity assays were performed with supercoiled templates. The reactions were performed similarly to those used for in vitro transcription, with minor modifications: plasmid DNA (1 µg) and proteins as indicated were incubated in 100 µl of a buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol and 100 µM each GTP and CTP. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, 0.1 vol. of 100 mM potassium permanganate solution was added for 15 s to the reaction mixtures containing DNA and proteins. The reactions were stopped by addition of 0.1 vol. of 14 M β-mercaptoethanol, 8 µg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA and sodium acetate to 0.3 M, precipitated with 3 vols of ice-cold ethanol and washed twice with 70% ethanol. The reaction products were solubilized in water and divided into two halves. Each half was used as a template for five cycles of amplification by Taq polymerase with 5′-radiolabelled primers to reveal the modified bases. The amplification products were analysed on 6% sequencing gels. The signals due to permanganate reactivity of bases were visualized, identified and quantified as described above.

β-galactosidase assay

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in fresh 2× YT medium. Triplicate samples taken at the times indicated were assayed for β-galactosidase activity following the protocol of Sadler and Novick (1965). β-galactosidase units were multiplied by 1000 to make them equivalent to those of Miller (1972).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank F.Boccard for purified IHF protein, M.Berkenkopf for technical assistance and R.Kahmann for critical comments. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SFB 397.

References

- Adhya S. and Gottesman,M. (1982) Promoter occlusion: transcription through a promoter may inhibit ist activity. Cell, 29, 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiba H. (1983) Autoregulation of the Escherichia coli crp gene: CRP is a transcriptional repressor for its own gene. Cell, 32, 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball C.A., Osuna,R., Ferguson,K.C. and Johnson,R.C. (1992) Dramatic changes in FIS levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 174, 8043–8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Bossi N., Guerin,M., Rahmouni,R., Leng,M. and Bossi,L. (1998) The supercoiling sensitivity of a bacterial tRNA promoter parallels its responsiveness to stringent control. EMBO J., 17, 2359–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Gil G., Bringmann,P. and Kahmann,R. (1996) FIS is a regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 22, 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Gil G., Kahmann,R. and Muskhelishvili,G. (1998) Regulation of crp transcription by oscillation between distinct nucleoprotein complexes. EMBO J., 17, 2877–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J.A. and McClure,W.R. (1991) Competing promoters in prokaryotic transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci., 16, 394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourse R.L., de Boer,H. and Nomura,M. (1986) DNA determinants of rRNA synthesis in E.coli: growth rate dependent regulation, feedback inhibition, upstream activation, antitermination. Cell, 44, 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govantes F., Orjalo,A.V. and Gunsalus,R.P. (2000) Interplay between global regulatory proteins mediates oxygen regulation of the Escherichia coli cytochrome d oxidase (cydAB) operon. Mol. Microbiol., 38, 1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffo G., Oppenheim,A. and Gottesman,M.E. (1989) Repression of the λ pcin promoter by integrative host factor. J. Mol. Biol., 209, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanamura A. and Aiba,H. (1991) Molecular mechanism of negative autoregulation of Escherichia coli crp gene. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 4413–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagura-Burdzy G. and Thomas,C.M. (1997) Dissection of the switch between genes for replication and transfer of promiscuous plasmid RK2: basis of the dominance of trfAp over trbAp and specificity for KorA in controlling the switch. J. Mol. Biol., 265, 507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson J., Balsalobre,C., Wang,S.-S., Urbonaviciene,J., Jin,D.J., Sonden,B. and Uhlin,B.E. (2000) Nucleoid proteins stimulate stringently controlled bacterial promoters: a link between the cAMP-CRP and the (p)ppGpp regulons in Escherichia coli. Cell, 102, 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C., Vanderkerckhove,J. and Kahmann,R.(1988) Escherichia coli host factor for site-specific DNA inversion: cloning and characterisation of the fis gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 4237–4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus L.R. and Travers,A.A. (1993) The E.coli FIS protein is not required for the activation of tyrT transcription on simple nutritional upshift. EMBO J., 12, 2483–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S.-T., Dennis,P.P. and Bremer,H. (1998) Expression of lacZ from the promoter of the Escherichia coli spc operon cloned into vectors carrying the W205 trp–lac fusion. J. Bacteriol., 180, 6090–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebig B. and Wagner,R. (1995) Effects of different growth conditions on the in vivo activity of the tandem ribosomal promoters P1 and P2. Mol. Gen. Genet., 249, 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley D.M.J. (1997) Transcription and DNA topology in eubacteria. In Eckstein,F. and Lilley,D.M.J. (eds), Mechanisms of Transcription. Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology, Vol. 11. Springer, Germany, pp. 191–218.

- Lisser S. and Margalit,H. (1993) Compilation of E.coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 1507–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. and Turnbough,C.L.,Jr (1994) Effects of transcriptional start site sequence and position on nucleotide-sensitive selection of alternative start sites at the pyrC promoter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 176, 2938–2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.F. and Wang,J.C. (1987) Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 7024–7027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Nasser W., Schneider,R., Travers,A. and Muskhelishvili,G. (2001) CRP modulates fis transcription by alternate formation of activating and repressing nucleoprotein complexes. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 17878–17886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson L., Verbeek,H., Vijgenboom,E., van Drunen,C., Vanet,A. and Bosch,L. (1992) FIS-dependent trans activation of stable RNA operons of Escherichia coli under various growth conditions. J. Bacteriol., 174, 921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninnemann O., Koch,C. and. Kahmann,R. (1992) The E.coli fis promoter is subject to stringent control and autoregulation. EMBO J., 11, 1075–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opel M., Arfin,S.M. and Hatfield,G.M. (2001) The effects of DNA supercoiling on the expression of operons of the ilv regulon of Escherichia coli suggest a physiological rationale for divergently transcribed operons. Mol. Microbiol., 39, 1109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt T.S., Steiner,T., Feldman,L.S., Walker,K.A. and Osuna,R. (1997) Deletion analysis of the fis promoter region in Escherichia coli: antagonistic effects of integration host factor and Fis. J. Bacteriol., 179, 6367–6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Menzel,R. and Tse-Dinh,Y-Cn. (1997) Regulation of Escherichia coli topA gene transcription: involvement of a σs-dependent promoter. J. Mol. Biol., 267, 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee K.Y., Opel,M., Ito,E., Hung,S., Arfin,S.M. and Hatfield,G.W. (1999) Transcriptional coupling between the divergent promoters of a prototypic LysR-type regulatory system, the ilvYC operon of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14294–14299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice PA, Yan, S, Mizuuchi,K. and Nash,H. (1996) Crystal structure of an IHF–DNA complex: a protein-induced DNA U-turn. Cell, 87, 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W., Gosink,K.K., Salomon,J., Igarishi,K., Zou,C., Ishihama,A., Severinov,K. and Gourse,R.L. (1993) A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science, 262, 1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler J.R. and Novick,A. (1965) The properties of repressor and the kinetics of each action. J. Mol. Biol., 12, 305–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmientos P., Sylvester,J.E., Contente,S. and Cashel,M. (1983) Differential stringent control of the tandem E.coli ribosomal RNA promoters from the rrnA operon expressed in vivo in multicopy plasmids. Cell, 32, 1337–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R., Travers,A., Kutateladze,T. and Muskhelishvili,G. (1999) A DNA architectural protein couples cellular physiology and DNA topology in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 34, 953–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R., Travers,A. and Muskhelishvili,G. (2000) The expression of the Escherichia coli fis gene is strongly dependent on the superhelical density of DNA. Mol. Microbiol., 38, 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers A.A. (1980) Promoter sequence for the stringent control of bacterial ribonucleic acid synthesis. J. Bacteriol., 141, 973–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker K.A., Atkins,C.L. and Osuna,R. (1999) Functional determinants of the Escherichia coli fis promoter: roles of –35, –10 and transcription initiation regions in the response to stringent control and growth phase dependent regulation. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1269–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechiedrich E.L., Khodursky,A.B. and Cozzarelli,N.R. (1997) Topoisomerase IV, not gyrase, decatenates products of site-specific recombination in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev., 11, 2580–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. and Bremer,H. (1996) Effects of Fis on ribosome synthesis and activity and on rRNA promoter activities in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 259, 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.N. and Jin,D.J. (1998) The rpoB mutants destabilising initiation complexes at stringently controlled promoters behave like ‘stringent’ RNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 2908–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]