Abstract

Background

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) represents a transitional stage to Alzheimer's disease (AD), making progression prediction crucial for timely intervention. Predictive models integrating clinical, laboratory, and survival data can enhance early diagnosis and treatment decisions. While machine learning approaches effectively handle censored data, their application in MCI-to-AD progression prediction remains limited, with unclear superiority over classical survival models.

Methods

We analyzed 902 MCI individuals from Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) dataset with 61 baseline features. Traditional survival models (Cox proportional hazards, Weibull, elastic net Cox) were compared with machine learning techniques (gradient boosting survival, random survival forests [RSF]) for progression prediction. Models were evaluated using C-index and IBS.

Results

Following feature selection, 14 key features were retained for model training. RSF achieved superior predictive performance with the highest C-index (0.878, 95% CI: 0.877–0.879) and lowest IBS (0.115, 95% CI: 0.114–0.116), demonstrating statistically significant superiority over all evaluated models (P-value < 0.001). RSF demonstrated effective risk stratification across individual biomarker categories (genetic, imaging, cognitive) and achieved optimal patient separation into three distinct prognostic groups when combining all features (p < 0.0001). SHAP-based feature importance analysis of RSF revealed cognitive assessments as the most influential predictors, with Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) achieving the highest importance score (1.098), followed by Logical Memory Delayed Recall Total (LDELTOTAL) (0.906) and Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS13) (0.770). Among neuroimaging biomarkers, Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) emerged as the leading predictor (0.634), ranking fifth overall. Feature importance ranking differed between classical and machine learning approaches, with FDG maintaining consistent importance across all models. RSF demonstrated excellent predictive calibration with positive net benefit across risk thresholds from 0.2 to 0.8.

Conclusions

The RSF model outperformed other methods, demonstrating superior potential for improving prognostic accuracy in medical diagnostics for MCI to AD progression.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12874-025-02689-w.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Survival analysis, Machine learning, Random survival forest

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition characterized by cognitive decline that significantly impairs daily activities, autonomy, and quality of life [1, 2]. Representing 60–80% of dementia cases [3], AD affects over 55 million individuals worldwide, with projections reaching 150 million by 2050 [4, 5]. As the seventh leading cause of death worldwide, AD and other forms of dementia contribute to one-third of deaths among the elderly, surpassing the combined mortality rates of breast and prostate cancer [6, 7].

Despite extensive clinical investigations spanning several decades, no therapeutic interventions currently exist for individuals diagnosed with AD, and available pharmacological options only delay disease progression [8]. For this reason, focusing on developing methods for predicting individuals at high risk of developing AD in its early stages, for the development of disease-modifying therapies, is important [9].

MCI represents a critical transitional stage before AD development, characterized by subjective cognitive complaints [10]. Research indicates that 10–15% of MCI patients progress to AD annually, with approximately 80% converting within six years [11, 12].

Early identification and progression prediction in MCI patients is crucial for timely interventions. Reliable predictive models integrating clinical, laboratory, and survival parameters can significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy and treatment decisions [12, 13].

Survival analysis is widely used in medical research to predict time-to-event outcomes and model covariate relationships [14]. Unlike binary classification models, survival analysis provides temporal progression information while handling censored data. This represents a critical advantage when outcomes become unobservable within study periods [15].

The semi-parametric Cox proportional hazards (CoxPH) regression model is the most widely used methodology for analysis censored survival data. It is commonly employed to identify prognostic covariates associated with survival and to predict the progression from MCI to AD, offering significant interpretability. However, this model assumes proportional hazards (PH), meaning that continuous covariates have a linear effect on the logarithm of the hazard, and the influence of these covariates is assumed to be independent of time. This assumption may not always hold when applied to real-world data [12, 16].

Machine learning survival methods have gained attention for their ability to model nonlinear relationships without traditional assumptions [6, 17]. Gradient Boosting Survival Analysis (GBSA) [18] and RSF [19] have shown superior performance over classical Cox regression in biomedical datasets [20, 21]. However, their complexity can limit interpretability compared to traditional approaches [22]. The Weibull model, on the other hand, offers interpretability and has also shown good performance in outcome prediction in recent studies [23, 24].

Although survival models hold significant potential for predicting MCI-to-AD progression, their application has remained limited, with most studies focusing on disease stage classification rather than time-to-event prediction. The primary objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive comparison of five survival modeling approaches including semi-parametric (CoxPH), parametric (Weibull), regularized (CoxEN), and machine learning techniques (GBSA, RSF) for predicting MCI-to-AD progression. To our knowledge, this represents the first investigation utilizing the complete eligible ADNI MCI cohort (n = 902 with at least one follow-up visit) with extended follow-up data spanning up to 16 years. This comprehensive approach provides significant advantages over previous studies that were constrained by limited 4-year follow-up periods or relied on pre-processed subsets of the available data [25–28], enabling more robust model evaluation and enhanced understanding of long-term progression patterns.

We systematically examined feature importance rankings across all five modeling approaches to reveal how classical statistical and machine learning frameworks differentially prioritize multimodal biomarkers. For the best-performing model, we conducted comprehensive interpretability analysis through SHAP values and Partial Dependence Plots (PDP), complemented by extensive clinical validation including risk stratification across individual biomarker categories and three distinct prognostic groups when combining all features, model calibration assessment, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) to demonstrate clinical utility for MCI-to-AD progression prediction.

Materials and methods

ADNI dataset

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public–private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD, and includes participants between the ages of 50 and 91, recruited at 63 research sites across the United States and Canada. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD.

The ADNI database is regularly updated, and as of early 2024, longitudinal data from over 2000 participants have been collected. The global literature boasts over 5600 ADNI publications [29].

In order to obtain permission for data usage, a request was sent along with an explanation of the research purpose. Written informed consent, including permission for analysis and data sharing, was obtained from all participants by ADNI at the time of enrollment. All work in this study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and ethical regulations set forth by the ADNI study and administered by the ADNI website. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1403.341).

Study population and data preprocessing

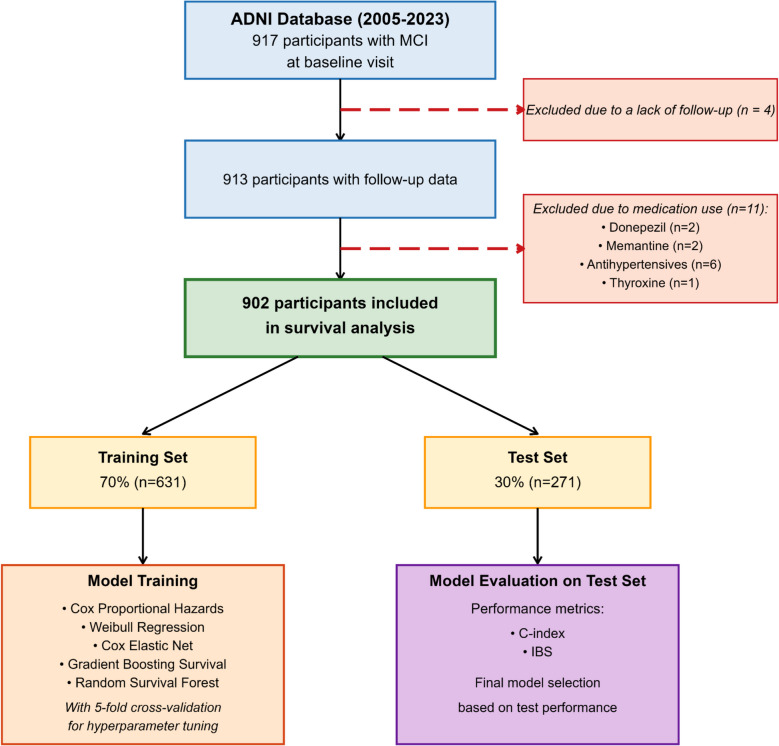

This study utilized the ADNIMERGE dataset from the ADNI database, which encompasses longitudinally collected data from all four phases of the ADNI project spanning 2005 to 2023. The dataset includes comprehensive variables such as demographic characteristics, biomarkers, clinical assessments, and neuroimaging measures. From the initial cohort of 917 participants diagnosed with MCI at baseline, 902 individuals with at least one follow-up visit were included following systematic exclusions for incomplete follow-up and potentially confounding medication use (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart illustrating the sequential selection, exclusion, and analytical workflow for baseline MCI participants in the ADNI cohort

Feature selection and imputation

Among the 61 features, 27 were removed due to missing values exceeding 25% in the MCI subset. For the remaining 34 features, we employed the nonparametric missForest method [30] using random forest predictions for imputation, which has demonstrated excellent performance in dementia-related datasets [31].

We built the Lasso Cox model to identify the best features for predicting the progression from MCI to AD. The Lasso Cox model shrinks coefficients toward zero, eliminating variables with little explanatory power or high correlation, and retains those with non-zero coefficients. The model has a tuning parameter (λ) to control the penalty strength, which can be optimized by cross-validation [14].

Used models for survival analysis

CoxPH

CoxPH regression is the most widely used model for predicting time-to-event outcomes from survival data, which was first proposed by Cox in 1972 and is often used as a popular model in medical research. In this semiparametric model, there is no need to specify the distribution of the baseline hazard, which is particularly advantageous when the hazard function is complex or unknown.

The CoxPH model assumes proportional hazards and linear log-hazard relationships—assumptions often violated in real-world data, motivating alternative approaches [32].

Weibull regression

In circumstances where the proportional hazards assumption is not tenable, parametric models which assume a specific probability distribution for survival times may more precise and prove to be fruitful. One of the most important probability distributions in survival data analysis is the Weibull distribution, which was first introduced by W. Weibull in 1951 for industrial reliability testing [33].

Cox penalised regression using elastic net

CoxEN extends the base CoxPH Model by incorporating Elastic Net regularisation, which applies a penalty to limit the overall weight assigned to predictor variables, reducing model complexity. This regularisation allows the model to shrink the coefficients of less important variables, potentially setting them to zero, as seen in some regularised regression approaches [34].

Gradient Boosting Survival Analysis (GBSA)

The Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) is an ensemble prediction method that iteratively enhances weak learners, such as decision trees, with each tree learning from the residuals of the preceding model. Each tree is constructed to minimize the residual error, thereby reducing the loss function at each iteration. GBM optimizes the loss function through gradient descent, building the model based on the negative gradient of the prior loss, where a lower loss value signifies improved prediction performance [35]. This framework has been adapted in the GBSA, which is specifically tailored for survival analysis and effectively manages censored data [18].

Random Survival Forests (RSF)

The random survival forest (RSF) [19], a widely used machine learning model for survival analysis, is an extension of the random forest algorithm (Breiman, 2001) [36] that is specifically designed to handle right-censored data. In the RSF, each tree is grown using independent bootstrap samples, where at each node, a subset of features is randomly selected. The node is then split using a survival criterion based on survival time and censoring status, typically applying the log-rank test to maximize the survival difference between daughter nodes. When a node becomes a leaf, RSF estimates both the cumulative hazard rate and survival probability based on all samples it contains. The cumulative hazard function is computed using the Nelson-Aalen estimator, and the final prediction for an individual is obtained by averaging the cumulative hazard estimates from all trees. Unlike traditional methods based on the CoxPH model, RSF does not rely on parametric assumptions, as it uses a nonparametric estimation approach for survival and risk functions, making it more flexible in handling complex data.

Model development and evaluation

After preprocessing, the data was randomly split into non-overlapping training (n = 631, 70%) and testing (n = 271, 30%) sets using stratified sampling based on event status to ensure balanced representation across both subsets. In this study, we developed five time-to-event models to predict the progression from MCI to AD, including three traditional survival methods (CoxPH, Weibull regression, CoxEN) and two ensemble learning approaches (RSF and GBSA).

We performed hyperparameter optimization for RSF, GBSA, and CoxEN models using fivefold cross-validation on training data, selecting parameter combinations that maximized C-index performance (Supplementary Table S1). Traditional models such as CoxPH and Weibull regression did not require hyperparameter tuning, as their parameters were determined analytically or through maximum likelihood estimation. Ultimately, the performance of all models was assessed based on the test set. The performance of the five models was compared using C-index and IBS.

The C-index is a metric used to evaluate how well a model predicts the order of survival times. It acts as a correlation coefficient, quantifying the degree of agreement between predicted survival risks and observed survival times. A C-index value of 1.0 indicates perfect prediction, where the model correctly ranks all individuals by their survival times. On the other hand, a value of 0.5 suggests that the model's predictions are no better than random guessing. The IBS evaluates the accuracy of a model's predicted survival probabilities by measuring the mean squared difference between these predictions and the actual observed survival outcomes over time. Scores range from 0 to 1, where lower values indicate better predictions. Models with an IBS below 0.25 are considered to perform well [37].

Statistical analysis was performed using R 4.2.1. Models were implemented using the survival, randomForestSRC, glmnet, and gbm packages.

Results

Participant characteristics and survival rate

During the follow-up period, 379 individuals (42.0%) progressed from MCI to AD, while 523 participants (58.0%) remained censored at the end of the observation period. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population, comparing Non-Converters and AD Converters, including 34 features such as demographic variables, gene expression, PET and MRI measures, and cognitive test results. Differences between the two groups were assessed using statistical tests for continuous variables (t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests) and tests for categorical variables (Chi-square or Fisher's Exact tests). Significant differences were observed between the two groups across most features (P-Value < 0.05), except for age, sex, education level, ethnicity, race, systolic, diastolic, Seated Pulse Rate (per minute), Respirations (per minute), NSAID and Intra-cranial volume (ICV) (P-Value > 0.05).

Table 1.

ADNI cohort baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | Non-Converters N = 523 Mean (SD)or n (%) |

AD Converters N = 379 Mean (SD)or n (%) |

Missing(%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age | 73.02 (7.57) | 73.83 (7.14) | 0.3 | 0.104a |

| Sex | 0 | 0.998c | ||

| Female | 209 (40%) | 152 (40.1%) | ||

| Male | 314 (60%) | 227 (59.9%) | ||

| Education_years | 15.90 (2.85) | 15.93 (2.75) | 0 | 0.878a |

| Marital_status | 0 | 0.038d | ||

| Unknown | 6 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Never married | 15 (2.9%) | 7 (1.8%) | ||

| Widowed | 52 (9.9%) | 42 (11.1%) | ||

| Divorced | 53 (10.1%) | 24 (6.3%) | ||

| Married | 397 (75.9%) | 306 (80.7%) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0 | 0.255c | ||

| Hisp/Latino | 20 (3.8%) | 9 (2.4%) | ||

| Not Hisp/Latino | 503 (96.2%) | 370 (97.6%) | ||

| Race | 0 | 0.179d | ||

| Other | 10 (1.9%) | 2 (0.5%) | ||

| Asian | 9 (1.7%) | 6 (1.6%) | ||

| Black | 22 (4.2%) | 10 (2.6%) | ||

| White | 482 (92.2%) | 361 (95.3%) | ||

| Clinical measurements | ||||

| Systolic | 134.46 (17.13) | 135.44 (18.10) | 0.3 | 0.408a |

| Diastolic | 75.45 (9.30) | 74.46 (9.98) | 0.3 | 0.127a |

| Seated pulse rate (per minute) | 64.92 (9.97) | 64.21 (10.27) | 0 | 0.298a |

| Respirations (per minute) | 16.50 (2.71) | 16.41 (2.71) | 0 | 0.598a |

| Medication variable | ||||

| NSAID | 0 | 0.054c | ||

| No | 270 (51.6%) | 171 (45.1%) | ||

| Yes | 253 (48.4%) | 208 (54.9%) | ||

| Gene expression | ||||

| ApoE_ε4 | 4 | < 0.001c | ||

| No ε4 allele | 314 (60%) | 140 (36.9%) | ||

| One or two copies of ε4 allele | 209 (40%) | 239 (63.1%) | ||

| PET measures | ||||

| FDG | 1.23 (0.12) | 1.15 (0.11) | 24 | < 0.001b |

| MRI measures | ||||

| Hippocampus | 7,026 (993) | 6,358 (999) | 15 | < 0.001b |

| WholeBrain | 1,044,238 (104,729) | 1,013,217 (112,439) | 3 | < 0.001b |

| Entorhinal | 3,719 (689) | 3,284 (721) | 15 | < 0.001b |

| Ventricles | 40,032 (22,253) | 43,776 (21,975) | 5 | 0.002b |

| ICV | 1,528,722 (154,077) | 1,550,756 (172,146) | 2 | 0.089b |

| Fusiform | 17,988 (2,467) | 16,764 (2,523) | 15 | < 0.001b |

| MidTemp | 20,189 (2,680) | 18,698 (2,767) | 15 | < 0.001b |

| Cognitive tests | ||||

| CDRSB | 1.34 (0.84) | 1.89 (0.95) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| ADAS11 | 9.10 (3.94) | 12.47 (4.52) | 0.2 | < 0.001a |

| ADAS13 | 14.61 (5.92) | 20.30 (6.29) | 0.5 | < 0.001a |

| ADASQ4 | 4.85 (2.28) | 6.82 (2.25) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| MMSE | 27.83 (1.79) | 27.06 (1.81) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| RAVLT_immediate | 36.53 (10.67) | 29.45 (8.18) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| RAVLT_learning | 4.59 (2.49) | 3.18 (2.34) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| RAVLT_forgetting | 4.39 (2.70) | 5.07 (2.21) | 0.1 | < 0.001a |

| RAVLT_perc_forgetting | 52.78 (35.08) | 74.75 (28.62) | 0.2 | < 0.001a |

| LDELTOTAL | 6.78 (3.20) | 4.08 (3.24) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| TRABSCOR | 107.35 (56.48) | 135.19 (74.16) | 1 | < 0.001a |

| FAQ | 2.22 (3.33) | 5.08 (4.72) | 1 | < 0.001a |

| mPACCdigit | −5.24 (3.55) | −8.22 (3.65) | 0 | < 0.001a |

| mPACCtrailsB | −4.78 (3.41) | −7.84 (3.47) | 0 | < 0.001a |

The aT-test and bMann-Whitney U test were used for continuous variables, while the cChi-square and dFisher's Exact tests were used for categorical variables

P-values less than 0.05 are bolded

The Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed a progression-free rate of 27% (95% CI: 20%–36%). The progression-free rates at 1, 4, and 8 years were 86% (95% CI: 84%–89%), 56% (95% CI: 52%–60%), and 39% (95% CI: 35%–45%), respectively. The median time to progression was 6 years (95% CI: 5–7 years), as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis summary

Feature selection

All baseline characteristics listed in Table 1 were incorporated into the Lasso Cox regression model. The vertical cutoff band at (s = 0.025) identifies the penalized model with minimized fivefold cross-validation error, as shown in Fig. 3a. The Lasso Cox regression analysis selected 17 best features with nonzero coefficients. After excluding highly collinear variables (Pearson correlation r > 0.70 or r < −0.70) to prevent overfitting, 14 final features were retained for model development. Each participant was characterized by these 14 baseline features, with two target outcomes: time-to-event (months from baseline to last follow-up visit) and progression status (conversion to AD or censored observation). The correlations between the final features are illustrated in Fig. 3b.

Fig. 3.

Feature selection. a The coefficient paths of the Lasso Cox model are shown, with a vertical blue line marking the optimal tuning parameter (s = 0.025). Features selected at this point are highlighted in green (positive coefficients) and red (negative coefficients). b The final 14 top features chosen by LASSO are displayed, after removing highly correlated features to ensure model accuracy

Evaluation and comparison of models performance

Table 2 summarizes the models' performance using the final 14 features (Fig. 3b), showing the optimal performance of the trained models based on the C-index and IBS metrics. Based on the C-index, RSF achieved the best performance with a score of 0.878 (95% CI: 0.877–0.879), followed by CoxPH with 0.863 (95% CI: 0.862–0.864), Weibull with 0.862 (95% CI: 0.861–0.863), CoxEN with 0.860 (95% CI: 0.859–0.861), and GBSA with 0.803 (95% CI: 0.802–0.804). Similarly, for the IBS metric, RSF demonstrated the best performance with a score of 0.115 (95% CI: 0.114–0.116), followed by Weibull and CoxPH, both achieving 0.120 (95% CI: 0.119–0.121), CoxEN with 0.143 (95% CI: 0.142–0.144), and GBSA with 0.165 (95% CI: 0.164–0.166). Statistical comparison using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons revealed that all models performed significantly different from the RSF reference model (P-value < 0.001 for both C-index and IBS metrics). Bootstrap resampling (n = 1000) was used to estimate CIs, with statistical significance set at P-value < 0.05. Ultimately, RSF was selected as the best-performing model for predicting the progression from MCI to AD using the final 14 features, demonstrating superior performance in both discrimination (C-index) and calibration (IBS) metrics.

Table 2.

Comparative performance metrics for survival models

| Model | C-index Mean (95% CI) |

IBS Mean (95% CI) |

C-Index P-value* |

IBS P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSF | 0.878 (0.877–0.879) | 0.115 (0.114–0.116) | Reference | Reference |

| Weibull regression | 0.862 (0.861–0.863) | 0.120 (0.119–0.121) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| CoxPH | 0.863 (0.862–0.864) | 0.120 (0.119–0.121) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| CoxEN | 0.860 (0.859–0.861) | 0.143 (0.142–0.144) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| GBSA | 0.803 (0.802–0.804) | 0.165 (0.164–0.166) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

*P-values were calculated using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons against RSF as reference model. Bootstrap resampling (n = 1000) was used to estimate confidence intervals. Statistical significance was set at P-value < 0.05

Model validation and performance evaluation

Figure 4 presents the validation of the RSF model performance for predicting progression from MCI to AD. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Panel A) demonstrate statistically significant risk stratification (P-value < 0.0001) with three distinct survival trajectories, where the high-risk group exhibited accelerated progression, the moderate-risk group showed intermediate outcomes, and the low-risk group maintained better survival outcomes. The calibration plot (Panel B) shows good agreement between predicted and observed overall survival probabilities across the range, with most data points positioned near the diagonal line of perfect calibration, demonstrating that the RSF model provides well-calibrated probability estimates. The DCA (Panel C) indicates that the RSF model offers clinical utility compared to treat-all and treat-none strategies, with positive net benefit observed across risk thresholds from 0.2 to 0.8, which assists in identifying MCI patients who would benefit from further evaluation or intervention.

Fig. 4.

Model Validation and Performance Evaluation of RSF Model. a Kaplan–Meier survival curves for three risk groups showing statistically significant stratification (P-value < 0.0001). b Calibration plot demonstrating agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities. c DCA showing clinical utility across risk thresholds from 0.2 to 0.8 compared to treat-all and treat-none strategies

Risk stratification performance by feature categories

Figure 5 displays the Kaplan–Meier curves for predicting the risk of conversion to AD in the training and test sets using the RSF model, which was selected due to its superior performance compared to other models. The analysis was conducted for the 14 top features, including (a) gene expression (ApoE_ε4), (b) PET (FDG), (c) MRI (Hippocampus, Entorhinal, Fusiform, MidTemp), (d) cognitive tests (LDELTOTAL, RAVLT_immediate, RAVLT_learning, RAVLT_perc_forgetting, CDRSB, FAQ, ADAS13, TRABSCOR), and (e) combined features (all 14 features). The median value was used as the cutoff point to categorize patients into low-risk and high-risk groups. Patients in the high-risk group had a significantly higher risk of conversion to AD than those in the low-risk group. Log-rank tests demonstrated significant stratification for all feature categories in both training and test sets (P-value < 0.001). The combination of all 14 features provided the most robust prognostic performance, allowing optimal stratification of patients for predicting progression from MCI to AD.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis using the RSF model for: (a) gene expression, (b) PET imaging, (c) MRI measures, (d) cognitive tests, and (e) combined features (all 14 features)

SHAP-based model interpretability and feature importance analysis

Model interpretability analysis using SHAP values based on training data (Fig. 6a-b) revealed that cognitive assessments far outweighed other measures in predicting dementia risk. FAQ emerged as the single most important predictor (mean |SHAP|= 1.098), followed closely by LDELTOTAL (0.906), ADAS13 (0.770), and RAVLT_perc_forgetting (0.668). The first neuroimaging biomarker, FDG ranked only fifth overall (0.634), with cognitive measures claiming 8 of the top 14 positions (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

SHAP Analysis for dementia risk prediction using RSF model. a Summary plot of SHAP values showing risk-increasing (red) and risk-decreasing (blue) effects, with features ranked by mean absolute SHAP importance. b Mean absolute SHAP importance by clinical domain (cognitive, imaging, genetic). c Individual SHAP contributions for lowest-risk patient (predicted risk = 0.001). d Individual SHAP contributions for highest-risk patient (predicted risk = 19.942)

Structural MRI measures had intermediate importance: Hippocampus (0.417), MidTemp (0.375), Fusiform (0.285), and Entorhinal (0.257). ApoE_ε4 ranked relatively low (11th; 0.296), indicating limited predictive value when comprehensive cognitive assessment was available.

Individual case examination illustrated these patterns clearly (Fig. 6c-d). The lowest-risk patient (predicted risk = 0.001) showed preserved cognitive function with FAQ = 0, RAVLT_immediate = 51, and LDELTOTAL = 8, generating protective SHAP effects (Fig. 6c). The highest-risk patient (predicted risk = 19.942) demonstrated widespread impairment with FAQ = 19, CDRSB = 3.5, and LDELTOTAL = 3, producing harmful SHAP contributions (Fig. 6d). This comparison reveals how combined impairments across multiple biomarker domains substantially increase predicted conversion risk.

These SHAP findings were validated through cross-model comparison across different survival modeling approaches (Supplementary Figures S1-S5). Classical survival models consistently ranked FDG first, while machine learning approaches favored FAQ. FDG maintained high importance across all frameworks, whereas MRI measures occupied middle positions regardless of modeling approach. ApoE_ε4 showed framework dependency, ranking second in classical models but dropping significantly in machine learning approaches.

Partial dependence analysis of biomarker survival effects

Figure 7 presents partial dependence plots derived from the RSF model for the 14 biomarkers, ordered by SHAP importance, demonstrating their individual effects on survival probability based on training data. FAQ showed a steep linear decline from 65 to 45% survival probability as functional impairment increased (Fig. 7a), while LDELTOTAL demonstrated a robust positive linear relationship increasing from 45 to 60% with better logical memory performance (Fig. 7b). ADAS13 exhibited the most dramatic linear decrease from 60 to 35% with worsening cognitive performance (Fig. 7c), and RAVLT_perc_forgetting displayed a relatively stable pattern with slight decline from 60 to 50%, suggesting minimal prognostic discrimination (Fig. 7d). FDG displayed the steepest positive linear relationship, increasing from 35 to 60% across the metabolic range (Fig. 7e), while RAVLT_immediate demonstrated consistent improvement from 45 to 60% with enhanced recall ability (Fig. 7f). CDRSB showed a notable linear decline from 60 to 45% with increasing dementia severity (Fig. 7g), and Hippocampus volume exhibited a positive linear association increasing from 45 to 60% (Fig. 7h). TRABSCOR demonstrated a similar positive linear pattern from 45 to 60% (Fig. 7i), as did MidTemp volume (Fig. 7j). ApoE_e4 genetic status revealed the expected binary risk pattern with non-carriers maintaining 60% survival probability compared to 50% for carriers (Fig. 7k), while Fusiform (Fig. 7l) and Entorhinal (Fig. 7m) volumes showed modest but consistent positive linear improvements from approximately 48–50% to 60%. Finally, RAVLT_learning exhibited a distinctive non-linear inverted U-shaped pattern with optimal survival probability (58%) at intermediate learning scores (2–3), declining to 50% at very low scores and returning to 52% at higher scores, suggesting a threshold effect where moderate learning performance provides the best prognostic value (Fig. 7n).

Fig. 7.

Partial dependence analysis of biomarker survival effects. a FAQ, (b) LDELTOTAL, (c) ADAS13, (d) RAVLT_perc_forgetting, (e) FDG, (f) RAVLT_immediate, (g) CDRSB, (h) Hippocampus, (i) TRABSCOR, (j) MidTemp, (k) ApoE_e4, (l) Fusiform, (m) Entorhinal, (n) RAVLT_learning. Individual biomarker relationships with survival probability derived from the RSF model, ordered by SHAP importance from highest to lowest. Each plot demonstrates the independent effect of biomarker values on predicted survival probability in MCI

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the performance of traditional survival models (CoxPH, Weibull regression, CoxEN) and machine learning approaches (GBSA, RSF) for predicting MCI-to-AD progression. We utilized the complete ADNI dataset spanning all four phases with comprehensive multimodal data including demographic, genetic, neuroimaging, and cognitive assessments. Following systematic feature selection using Lasso Cox regression and collinearity assessment, 14 optimal features were retained for model development (Fig. 2b). Most of the selected features are consistent with those identified in previous studies [11, 38].

Several key findings were observed in this study. Firstly, a comparison of the C-index and IBS across the five models showed that RSF achieved the highest predictive accuracy (C-index = 0.878, 95% CI: 0.877–0.879) and lowest IBS (0.115, 95% CI: 0.114–0.116), indicating superior model calibration and overall performance (Table 2). RSF was followed by CoxPH, Weibull regression, CoxEN, and GBSA in terms of predictive performance. Statistical comparison using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction revealed that all models demonstrated significantly inferior performance compared to the RSF reference model (p < 0.001 for both C-index and IBS metrics). Risk stratification using RSF effectively categorized patients into distinct prognostic groups, with Kaplan–Meier analysis showing significant survival differences across risk categories (Fig. 3a, p < 0.0001). The RSF model demonstrated excellent predictive calibration with good agreement between predicted and observed survival probabilities (Fig. 3b) and positive net benefit across risk thresholds from 0.2 to 0.8 (Fig. 3c), indicating substantial clinical utility for identifying patients requiring further evaluation. The results in this study were similar to those reported by some previous studies, where RSF consistently demonstrated superior performance in medical prediction tasks. Sarica et al. [25] compared tree-based survival models, including RSF, with the CoxPH model for predicting the conversion from MCI to AD, revealing that RSF achieved the highest accuracy (c-index 0.87), while CPH had the lowest (0.83). Similarly, Musto et al. [39] evaluated CPH, RSF, and SNN on the ADNI2 dataset, finding RSF to be the best-performing model with a c-index of 0.86. In another study, Stamate et al. [40] applied Random Forest, Elastic Net, and Cox models to predict dementia onset using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) cohort, with RSF again demonstrating superior performance in terms of both predictive accuracy and stability. These studies consistently highlight RSF as a superior model in predicting dementia-related outcomes. However, Wang et al. [41] used simulated data to compare CPH and machine learning survival models for dementia prediction, finding that both methods showed similar accuracy.

Accurate early identification of individuals at high risk for cognitive decline, particularly MCI-to-AD progression, is crucial for enabling timely interventions and improving disease management. The RSF model, owing to its superior performance compared to other models, was used to stratify MCI patients into low- and high-risk groups across both the training and test sets. The analysis was based on 14 key features encompassing genetic, imaging, cognitive, and combined measures, with the high-risk group exhibiting a significantly greater likelihood of conversion to AD (Fig. 4). Furthermore, combining these varied features enhanced prognostic performance (Fig. 4e), resulting in improved risk stratification and more accurate predictions of disease progression. This aligns with previous research on AD, which has shown that the inclusion of clinical variables, along with grey matter volumes of brain regions, boosts predictive accuracy (Nakagawa et al.) [42], while neuroimaging and genetic markers contribute to better prediction (Hou et al.) [43], and studies have confirmed that multimodal approaches outperform single-modality models in AD staging (Venugopalan et al. [44], Mirabnahrazam et al. [45]).

This study suggests that structured cognitive assessment may complement current dementia evaluation approaches. While neuroimaging and genetic testing are valuable diagnostic tools, our SHAP analysis of the RSF model revealed that cognitive assessments far outweighed other measures in predicting dementia risk, with FAQ emerging as the single most important predictor (mean |SHAP|= 1.098), followed closely by LDELTOTAL (0.906) and ADAS13 (0.770). The first neuroimaging biomarker, FDG, ranked only fifth overall (0.634), with cognitive measures claiming 8 of the top 14 positions, indicating that clinical measures could provide comparable or even superior predictive accuracy, with important implications for clinical decision-making and resource allocation. Partial dependence analysis further demonstrated FAQ's clinical utility, showing a steep linear decline from 65 to 45% survival probability as functional impairment increased, providing specific thresholds for clinical decision-making. The strong performance of FAQ in our analysis receives validation from research across different populations that has consistently demonstrated FAQ's strong diagnostic performance, with studies showing high sensitivity (80–94%) and good specificity (75–87%) for detecting cognitive impairment using optimal cut-off scores ranging from 5.6–6. These findings support that FAQ captures critical functional changes observable to families before clinical manifestation [46, 47]. A landmark study with 1,148 subjects demonstrated that specific FAQ items effectively discriminate between cognitively normal and MCI subjects and predict progression to cognitive impairment [48].

Our findings regarding LDELTOTAL, which emerged as the second most influential predictor in our SHAP analysis, are supported by comprehensive research highlighting its predictive value. Partial dependence analysis revealed LDELTOTAL's robust positive linear relationship, increasing survival probability from 45 to 60% with better logical memory performance, demonstrating clear prognostic value. A longitudinal analysis of 2,178 ADNI participants demonstrated that LDELTOTAL scores significantly discriminated between cognitive states and showed meaningful interactions with APOE-ε4 genotype during disease progression [49]. Additionally, an independent RSF study across NACC and ADNI cohorts identified LDELTOTAL among the top six predictors for clinical Alzheimer's dementia onset, reinforcing its critical role in capturing early memory consolidation deficits [50].

Contemporary longitudinal research has established ADAS-13 as a robust biomarker for tracking cognitive deterioration throughout the Alzheimer's disease continuum. Disease progression modeling demonstrates that individuals typically advance from preclinical AD to MCI over 7.8 years, requiring an additional 7.4 years to reach dementia, with ADAS-13 scores providing reliable trajectory assessment [51]. Our partial dependence analysis corroborates these findings, revealing that ADAS13 exhibits the most pronounced prognostic relationship among cognitive measures, with survival probability declining precipitously from 60 to 35% as cognitive performance deteriorates. Recent validation studies have confirmed ADAS-13's clinical effectiveness in identifying high-risk MCI populations, achieving an optimism-corrected concordance index of 0.830 [52], which substantiates its elevated ranking in our feature importance hierarchy.

Cross-model comparison of variable importance rankings revealed striking methodological differences in biomarker prioritization, highlighting fundamental disparities between traditional statistical and machine learning approaches (Supplementary Figures S1-S5). The three classical survival models demonstrated remarkable consistency, universally placing FDG as the primary predictor, followed by ApoE_ε4, ADAS13, and CDRSB in their top positions. FDG, a measure of brain glucose metabolism, shows reduced activity in regions affected by AD, serving as a marker for neurodegeneration [53, 54]. Partial dependence analysis confirmed FDG's robust prognostic value, displaying the steepest positive linear relationship among neuroimaging biomarkers, with survival probability increasing dramatically from 35 to 60% across the metabolic range (Fig. 6e). Additionally, ApoE_ε4 is a well-established genetic risk factor for AD, with individuals carrying two alleles exhibiting a higher risk and faster disease progression [53, 55, 56]. Numerous studies have identified these variables as critical biomarkers for assessing the risk of AD progression and the transition from MCI to AD [11, 55, 57–59].

In contrast, machine learning algorithms exhibited different feature importance patterns, consistently ranking FAQ as the most influential predictor while traditional neuroimaging and genetic biomarkers demonstrated reduced importance. These models place a stronger emphasis on cognitive and functional assessments, which may offer greater sensitivity in detecting early-stage Alzheimer's progression. Previous studies have shown that the FAQ, which evaluates instrumental activities of daily living, is an important tool in distinguishing between MCI and AD, as functional changes are often observed early in dementia [11, 25, 59]. Additionally, ADAS13, a task within the Cognitive Subscale of the AD Assessment (which includes 11 items), is frequently used to assess cognitive impairment and track disease severity [25, 60].

LDELTOTAL is another variable from neuropsychological tests that assesses an individual's ability to remember information after some time. Studies have associated LDELTOTAL with AD progression, highlighting its role in identifying cognitive decline [25, 60].

Individual case examination through SHAP analysis (Fig. 5c-d) illustrated these contrasting methodological approaches through two extreme patient profiles: the lowest-risk patient (predicted risk = 0.001) demonstrated preserved cognitive function with FAQ = 0, RAVLT_immediate = 51, LDELTOTAL = 8, and CDRSB = 1, generating protective SHAP effects across multiple cognitive domains. Conversely, the highest-risk patient (predicted risk = 19.942) exhibited comprehensive cognitive deterioration with FAQ = 19, RAVLT_immediate = 21, LDELTOTAL = 3, and CDRSB = 3.5, producing risk-increasing SHAP contributions across all assessed cognitive measures. This analysis demonstrates that the RSF framework exhibits superior performance compared to classical statistical approaches in identifying optimal predictive biomarker combinations.

This study had two main limitations. The first limitation was that the prediction models were constructed using ADNI data from MCI patients, which lacked diversity and was predominantly composed of white North-American participants. As a result, these models needed to be validated on independent cohorts from different countries and ethnic backgrounds, particularly non-white and non-western populations, to ensure their broader generalizability. The second limitation concerns the scope of analyzed variables. Our analysis utilized 34 variables following systematic exclusion of features with missing values exceeding 25% or those not measured in our study population. Several potentially influential factors including lifestyle behaviors (alcohol consumption, smoking, physical exercise), comprehensive medical history (depression, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes), and detailed comorbidity profiles were unavailable for analysis. These unmeasured confounding variables may have contributed to MCI-to-AD progression patterns and could potentially influence model performance and observed associations. Incorporating such factors could enhance the accuracy of survival prediction models for the progression from MCI to AD.

Conclusion

This study compared the performance of traditional survival models and machine learning approaches in predicting the progression from MCI to AD. While all methods demonstrated satisfactory performance, the RSF model outperformed other approaches and was ultimately selected as the best-performing model using the final 14 features. These findings highlight RSF's potential as an effective tool for improving MCI-to-AD prediction and supporting early clinical intervention strategies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Vice-Chancellor of Education at Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for their technical support, approval, and assistance with this work.

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- DAT

Dementia of Alzheimer's type

- ADI

Alzheimer’s disease international

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- CoxPH

Cox proportional hazards

- GBSA

Gradient boosting survival analysis

- RSF

Random survival forest

- CoxEN

Cox regression based on elastic net penalty

- ADNI

Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative

- C-index

Harrell’s concordance index

- IBS

Integrated brier score

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- ICV

Intra-cranial volume

- MidTemp

Middle tem poral gyrus

- CDRSB

Clinical dementia rating sum of boxes

- ADAS

Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale

- MMSE

Mini-mental state examination

- RAVLT

Rey auditory verbal learning test

- LDELTOTAL

Logical memory delayed recall total

- TRABSCOR

Trail making test part B

- FAQ

Functional activities questionnaire

- mPACCdigit

Modified preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with digit symbol substitution

- mPACCtrailsB

Modified preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with trails B

- NSAID

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Authors’ contributions

S.J., G.R., and L.T. contributed to the conception and design of the study, performed the methods, analysis the results, and drafted the manuscript. S.J., G.R., and L.T. interpreted the results. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported and approved by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Grant NO: 140305234181).

Data availability

The ADNI dataset can be accessed at [https://adni.loni.usc.edu](https:/adni.loni.usc.edu).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1403.341) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the ADNI study and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent, including permission for data analysis and sharing, was obtained from all participants or their guardians at the time of enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(1):59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(3):137–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrie HC. Epidemiology of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6(2):S3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L-K, Kuan Y-C, Lin H-W, Hu C-J. Clinical trials of new drugs for Alzheimer disease: a 2020–2023 update. J Biomed Sci. 2023;30(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirabnahrazam G, Ma D, Beaulac C, Lee S, Popuri K, Lee H, et al. Predicting time-to-conversion for dementia of Alzheimer’s type using multi-modal deep survival analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2023;121:139–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baytaş İM. Predicting progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia with adversarial attacks. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2024;28(6):3750–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Siedlecki-Wullich D, Català-Solsona J, Fábregas C, Hernández I, Clarimon J, Lleó A, et al. Altered microRNAs related to synaptic function as potential plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2019;11:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mofrad SA, Lundervold A, Lundervold AS, Initiative AsDN. A predictive framework based on brain volume trajectories enabling early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2021;90:101910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Zhang L, Qiao L, Shen D. Toward a better estimation of functional brain network for mild cognitive impairment identification: a transfer learning view. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2019;24(4):1160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grammenos G, Vrahatis AG, Vlamos P, Palejev D, Exarchos T, Initiative AsDN. Predicting the conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease using an explainable AI approach. Information. 2024;15(5):249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park M-K, Ahn J, Lim J-M, Han M, Lee J-W, Lee J-C, et al. A transcriptomics-based machine learning model discriminating mild cognitive impairment and the prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. Cells. 2024;13(22):1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsala A, Tsalikidis C, Pitiakoudis M, Simopoulos C, Tsaroucha AK. Artificial intelligence in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. A new era. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(3):1581–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 4th ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2023. 10.1201/9781003282525.

- 15.Wang P, Li Y, Reddy CK. Machine learning for survival analysis: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2019;51(6):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faraggi D, Simon R. A neural network model for survival data. Stat Med. 1995;14(1):73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shivaswamy PK, Chu W, Jansche M. A support vector approach to censored targets. In: Seventh IEEE international conference on data mining (ICDM 2007). IEEE; 2007:655–60.

- 18.Chen Y, Jia Z, Mercola D, Xie X. A gradient boosting algorithm for survival analysis via direct optimization of concordance index. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013;2013:1–873595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB, Blackstone EH, et al. Lauer MS. Random survival forests Ann Appl Stat. 2008;2(3):841–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abuhelwa AY, Kichenadasse G, McKinnon RA, Rowland A, Hopkins AM, Sorich MJ. Machine learning for prediction of survival outcomes with immune-checkpoint inhibitors in urothelial cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9):2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang X, Qiu H, Wang L, Wang X. Predicting colorectal cancer survival using time-to-event machine learning: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e44417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavalcante T, Ospina R, Leiva V, Cabezas X, Martin-Barreiro C. Weibull regression and machine learning survival models: methodology, comparison, and application to biomedical data related to cardiac surgery. Biology. 2023;12(3):442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolasseri AE. Comparative study of machine learning and statistical survival models for enhancing cervical cancer prognosis and risk factor assessment using SEER data. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):22203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarica A, Aracri F, Bianco MG, Vaccaro MG, Quattrone A, Quattrone A: Conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: A comparison of tree-based machine learning algorithms for survival analysis. In: International conference on brain informatics. Springer; 2023:179–90.

- 26.Fiford CM, Nicholas JM, Biessels GJ, Lane CA, Cardoso MJ, Barnes J. High blood pressure predicts hippocampal atrophy rate in cognitively impaired elders. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2020;12(1):e12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarica A, Pelagi A, Aracri F, Arcuri F, Quattrone A, Quattrone A. Sex differences in conversion risk from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: an explainable machine learning study with random survival forests and SHAP. Brain Sci. 2024;14(3):201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang M, Sajobi TT, Ismail Z, Seitz D, Chekouo T, Forkert ND, et al. A pragmatic dementia risk score for patients with mild cognitive impairment in a memory clinic population: development and validation of a dementia risk score using routinely collected data. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2022;8(1):e12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toga AW, Neu S, Sheehan ST, Crawford K, Initiative AsDN. The informatics of ADNI. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20(10):7320–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. Missforest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aracri F, Bianco MG, Quattrone A, Sarica A: Imputation of missing clinical, cognitive and neuroimaging data of Dementia using missForest, a Random Forest based algorithm. In: 2023 IEEE 36th international symposium on computer-based medical systems (CBMS). IEEE; 2023:684–8.

- 32.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology. 1972;34(2):187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weibull W. A statistical distribution function of wide applicability. J Appl Mech. 1951. 10.1115/1.4010337 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology. 2005;67(2):301–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001. 10.1214/aos/1013203451 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang D, Luan J, Liu B, Yang A, Lv K, Hu P, et al. Comparison of MRI radiomics-based machine learning survival models in predicting prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme. Front Med Lausanne. 2023;10:1271687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pena D, Suescun J, Schiess M, Ellmore TM, Giancardo L, Initiative AsDN. Toward a multimodal computer-aided diagnostic tool for Alzheimer’s disease conversion. Front Neurosci. 2022;15:744190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musto H, Stamate D, Pu I, Stahl D: Predicting Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis risk over time with survival machine learning on the ADNI Cohort. In: International Conference on Computational Collective Intelligence. Springer; 2023:700–12.

- 40.Stamate D, Musto H, Ajnakina O, Stahl D: Predicting risk of dementia with survival machine learning and statistical methods: results on the English longitudinal study of ageing cohort. In: IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. Springer; 2022:436–47.

- 41.Wang M, Greenberg M, Forkert ND, Chekouo T, Afriyie G, Ismail Z, et al. Dementia risk prediction in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: a comparison of Cox regression and machine learning models. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakagawa T, Ishida M, Naito J, Nagai A, Yamaguchi S, Onoda K. Prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease using deep survival analysis of MRI images. Brain Commun. 2020. 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hou X-H, Suckling J, Shen X-N, Liu Y, Zuo C-T, Huang Y-Y, et al. Multipredictor risk models for predicting individual risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venugopalan J, Tong L, Hassanzadeh HR, Wang MD. Multimodal deep learning models for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease stage. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mirabnahrazam G, Ma D, Lee S, Popuri K, Lee H, Cao J, et al. Machine learning based multimodal neuroimaging genomics dementia score for predicting future conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;87(3):1345–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin L, Ren Y, Wang X, Li Y, Hou T, Liu K. The power of the functional activities questionnaire for screening dementia in rural-dwelling older adults at high-risk of cognitive impairment. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;20:427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teng E, Becker BW, Woo E, Knopman DS, Cummings JL, Lu PH. Utility of the functional activities questionnaire for distinguishing mild cognitive impairment from very mild Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(4):348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshall GA, Zoller AS, Lorius N, Amariglio RE, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, et al. Functional activities questionnaire items that best discriminate and predict progression from clinically normal to mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(5):493–502. 10.2174/156720501205150526115003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fokuoh E, Xiao D, Fang W, Liu Y, Lu Y, Wang K. Longitudinal analysis of APOE-ε4 genotype with the logical memory delayed recall score in Alzheimer’s disease. J Genet. 2021;100(2):60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song S, Asken B, Armstrong MJ, Yang Y, Li Z, Initiative AsDN. Predicting progression to clinical Alzheimer’s disease dementia using the random survival forest. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023;95(2):535–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho SH, Woo S, Kim C, Kim HJ, Jang H, Kim BC, et al. Disease progression modelling from preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to AD dementia. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ge X, Cui K, Liu L, Qin Y, Cui J, Han H, et al. Screening and predicting progression from high-risk mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bogdanovic B, Eftimov T, Simjanoska M. In-depth insights into Alzheimer’s disease by using explainable machine learning approach. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcus C, Mena E, Subramaniam RM. Brain PET in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(10):e413–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarica A, Aracri F, Bianco MG, Arcuri F, Quattrone A, Quattrone A. Explainability of random survival forests in predicting conversion risk from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Inform. 2023;10(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shigemizu D, Akiyama S, Higaki S, Sugimoto T, Sakurai T, Boroevich KA, et al. Prognosis prediction model for conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease created by integrative analysis of multi-omics data. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2020;12:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gomar JJ, Conejero-Goldberg C, Davies P, Goldberg TE, Initiative AsDN. Extension and refinement of the predictive value of different classes of markers in ADNI: four-year follow-up data. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):704–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sörensen A, Blazhenets G, Rücker G, Schiller F, Meyer PT, Frings L. Prognosis of conversion of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia by voxel-wise Cox regression based on FDG PET data. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2019;21:101637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ho N-H, Jeong Y-H, Kim J. Multimodal multitask learning for predicting MCI to AD conversion using stacked polynomial attention network and adaptive exponential decay. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):11243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dansson HV, Stempfle L, Egilsdóttir H, Schliep A, Portelius E, Blennow K, et al. Predicting progression and cognitive decline in amyloid-positive patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2021;13:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The ADNI dataset can be accessed at [https://adni.loni.usc.edu](https:/adni.loni.usc.edu).