Abstract

Background

Post-stroke delirium (PSD) is a common complication following cerebrovascular accidents and correlates with adverse clinical outcomes. The stress hyperglycemic ratio (SHR) is a recognized prognostic marker for cerebrovascular diseases, but its predictive value for PSD remains uncertain. This research aimed to explore the association between SHR and PSD in critically ill patients with ischemic stroke (IS).

Methods

Data were obtained from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. PSD assessment was performed via the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Units (CAM–ICU). Participants diagnosed with IS were categorized into four quartile groups (Q1–Q4) according to SHR levels. We evaluated the relationship between SHR and PSD using logistic regression modeling and restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis. Subgroup analyses were conducted to validate the consistency.

Results

Among 1389 patients (mean age 70.53 ± 14.96 years, 50.04% male), 30.60% developed PSD. The incidence of PSD increased with higher SHR quartiles (Q4: 44.83% vs. Q1: 20.50%, P < 0.001). Multivariate logistic analyses indicated that SHR was independently associated with PSD both as a continuous variable (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.01–2.86; P = 0.047) and a quartile-based variable (Q4: OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.07–2.54; P = 0.024). The RCS curves showed a linear association between SHR and PSD development (P for non-linearity = 0.286). Subgroup analyses suggested potential interactions between SHR and age, gender, and sepsis status (all P for interaction < 0.05).

Conclusions

Elevated SHR levels are independently associated with an increased risk of PSD in critically ill patients with IS, highlighting its role as a possible prognostic indicator. Early management in high-risk individuals may enhance clinical outcomes. Additional prospective studies are necessary to validate these results.

Keywords: Stress hyperglycemia ratio, Post-stroke delirium, Ischemic stroke, Intensive care unit, Hospital mortality

Background

Delirium manifests as a sudden confusional state involving rapid fluctuations in attention, awareness, or cognition (within hours to days), when other conditions or coma are ruled out [1]. It may result from diverse triggers, such as acute illness, medication use/withdrawal, trauma, or surgery [2, 3]. Prevalent across inpatient settings, delirium affects 20–50% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients and 50–70% of mechanically ventilated patients [4, 5]. Neurological disorders are significant predisposing factors for delirium. Approximately 55% of delirium patients exhibit brain lesions, while 16% show cerebral atrophy [6]. Post-stroke delirium (PSD) is a common complication occurring in the acute or subacute phase after a cerebrovascular accident. It affects about 25% of acute stroke patients [7]. PSD prolongs hospitalization, raises healthcare costs, and independently predicts worse long-term outcomes, including higher mortality, delayed recovery, and aggravated cognitive deficits [8].

Stress hyperglycemia, defined by a temporary increase in glycemia levels under physiological or pathological stress conditions, occurs even in non-diabetic individuals [9]. Among acute ischemic stroke (IS) patients, its prevalence ranges from 21 to 27% [10], with potentially higher rates in critical condition. Stress hyperglycemia is linked to adverse prognosis, including elevated cardiovascular risk, extended hospitalization, reduced survival, and increased delirium incidence among surgical patients, ICU admissions, and elderly inpatients [11, 12]. However, stress hyperglycemia is influenced by baseline glycemic status, limiting its reliability for assessing true glucose fluctuations under stress. The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) integrates acute glycemia levels with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements. Since HbA1c indicates the average glycemia levels over the previous 3 months, SHR could offer a more reliable evaluation of stress hyperglycemia [13]. Numerous studies have found SHR’s predictive value for cerebrovascular disease outcomes, encompassing mortality [14–16], neurological recovery [17], and consciousness levels [18]. Nevertheless, the ability of SHR to predict PSD development has not been fully explored.

The present work explored whether SHR correlates with PSD development in critically ill patients with IS. Early recognition of this connection might enable clinicians to implement preventive strategies and improve outcomes in susceptible individuals.

Methods

Data source

Our research employed patient records from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV version 3.1) database, which incorporates 546,028 admissions records from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center spanning the years 2008–2022 [19]. Author Junhui Zou acquired database access (No. 66659928) following completion of the training course provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and successful passage of the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) program. Since the data set contained no identifiable patient information, informed consent was not necessary.

Selection of participants

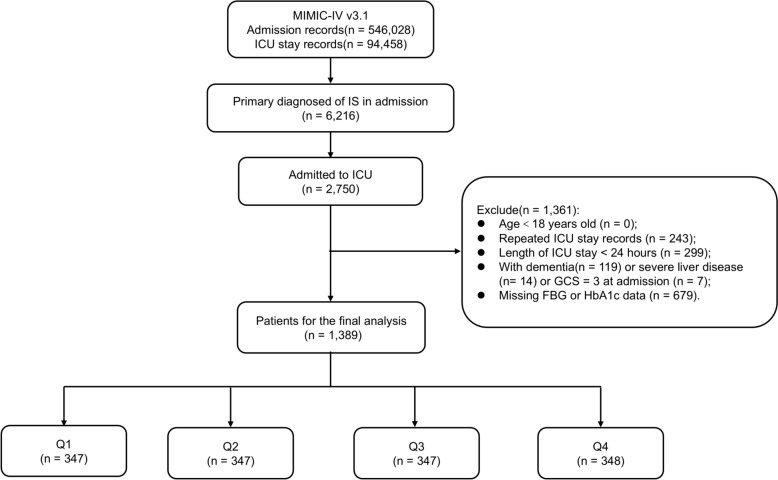

We analyzed 94,458 patients with ICU stay records. Based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and ICD-10), 2750 participants with a primary diagnosis of IS were recruited for the study. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) age < 18 years at first ICU admission(n = 0); (2) repeated ICU stay records for IS (only the initial record was analyzed; n = 243); (3) length of ICU stay < 24 h (n = 299); (4) the presence of dementia (n = 119), severe liver disease (n = 14) or a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score = 3 at ICU admission (n = 7), as these conditions could interfere delirium assessment; and (5) lack of recorded blood glucose (FBG) or HbA1c data in the first 24 h after ICU admission (n = 679). The final analysis involved 1389 eligible patients in this investigation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the present study. MIMIC-IV Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV, IS ischemic stroke, ICU intensive care unit, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c

Data collection

We extracted data using Structured Query Language (SQL) with PostgreSQL (version 15.12) and Navicat Premium (version 17). Since current evidence indicates that delirium development is associated with multiple factors, we included all available relevant variables [7, 20, 21]. The extracted variables included: (1) demographics: age, gender, and race. (2) Comorbidities: sepsis, hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, hyperlipidemia, renal failure, paraplegia, severe liver disease, dementia, malignant cancer, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). (3) Laboratory parameters: white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin concentration (Hb), platelet count (PLT), serum creatinine, sodium, potassium, anion gap (AG), international normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), FBG, HbA1c, and triglycerides (TG). (4) Vital signs: systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP), and mean blood pressure (MBP), heart and respiratory rate. (5) Severity of illness scores: sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Acute Physiology Score III (APSIII), and GCS score. (6) Treatments: mechanical thrombectomy (MT), ventilator time, intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV-tPA), mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drug, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam. (7) Length of stay (LOS) in the hospital and ICU. To compute SHR, the equation applied was: [FBG (mg/dL)/(28.7 × HbA1c (%)− 46.7)] [13]. For laboratory parameters, vital signs, and severity scores measured multiple times during hospitalization, we utilized the first recorded values within the first day of ICU stay records.

To limit bias, variables showing > 20% missing data were excluded. For the remaining variables (< 20% missing values), we performed multiple imputation [22].

Clinical outcomes

PSD development served as the primary outcome, which was measured by the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM–ICU). The CAM–ICU exhibited a sensitivity of 76% (95% CI 55–91%) and a specificity of 98% (95% CI 93–100%) for PSD screening, ensuring reliable diagnosis [23]. In the MIMIC database, trained nursing staff performed CAM–ICU assessments at least twice daily. This tool contains the following features: (1) acute change or fluctuating mental status, (2) Inattention, (3) Disorganized thinking, (4) Altered consciousness. A positive CAM–ICU result was confirmed when a patient exhibited features 1 and 2, along with either feature 3 or 4. Hospital mortality served as the secondary outcome.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed with t tests or ANOVA. Non-normally distributed data are expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) and analyzed using Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared with chi-square tests.

To explore the predictive value of SHR for clinical outcomes, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed, presenting outcomes in terms of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Three progressively adjusted models were built: model 1: unadjusted for any confounders; model 2: adjusted for age, gender, and race; model 3: additionally adjusted for comorbidities (sepsis, heart failure, arterial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, and CCI), laboratory parameters (WBC, RBC, Hb, potassium, AG, and AST), vital signs (heart rate and respiratory rate), severity scores (SOFA, GCS, and APS III), and treatments (IV-tPA, ventilator time, vasoactive drug, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam). In addition, prolonged hospitalization—particularly in the ICU—increases both exposure to delirium risk factors and its incidence [24–26]. Therefore, we included both hospital and ICU LOS as covariates in model 3 when exploring the relationship between SHR and PSD. To assess multicollinearity, we calculated variance inflation factors (VIFs) and excluded variables with VIF values > 5.

The potential non-linear relationship of SHR with clinical outcomes was evaluated using restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis. We conducted subgroup analyses to verify the findings and detect potential interaction effects, stratifying patients by age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years), gender, race, mechanical ventilation, sepsis, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, and diabetes. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess interaction effects. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.3), with statistical significance defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the 1389 enrolled patients was 70.53 ± 14.96 years, with males accounting for 50.04%. The median SHR value was 0.97(IQR: 0.84–1.15). 425 (30.60%) patients developed PSD during the ICU stay, and 158 (11.38%) died while hospitalized.

Patients were stratified into quartiles based on SHR values: Q1 (≤ 0.837), Q2 (0.837–0.996), Q3 (0.996–1.154), and Q4 (> 1.154), with Q1 serving as the reference group. Median SHR values were 0.75 (IQR 0.68–0.80) in Q1, 0.90 (IQR 0.87–0.93) in Q2, 1.04 (IQR 1.00–1.10) in Q3, and 1.30 (IQR 1.22–1.47) in Q4. Compared with Q1, Q4 patients had significantly higher WBC, AG, and AST levels; elevated heart and respiratory rates; increased illness severity scores and CCI; higher rates of sepsis, heart failure, diabetes, renal failure, and paraplegia; more frequently required mechanical ventilation and for longer durations, as well as more frequent administration of vasoactive and sedative–analgesic drugs (all P < 0.05). Comparison of LOS indicated that the groups with elevated SHR levels exhibited prolonged hospital and ICU stays (all P < 0.001). Both PSD incidence and hospital mortality rose across quartiles: PSD rates were 20.50%, 24.78%, 31.99%, and 44.83% (P < 0.001), while mortality rates were 5.76%, 7.78%, 13.26%, and 18.68% (P < 0.001). More details of the baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to SHR quartiles

| Categories | Overall (n = 1389) | Q1 (n = 347) | Q2 (n = 347) | Q3 (n = 347) | Q4 (n = 348) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 0.97 (0.84,1.15) | 0.75 (0.68,0.80) | 0.90 (0.87,0.93) | 1.04 (1.00,1.10) | 1.30 (1.22,1.47) | < 0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 70.53 ± 14.96 | 71.07 ± 14.64 | 69.69 ± 15.71 | 70.32 ± 14.90 | 71.02 ± 14.59 | 0.577 |

| Male (%) | 695 (50.04) | 167 (48.13) | 193 (55.62) | 172 (49.57) | 163 (46.84) | 0.098 |

| White (%) | 770 (55.44) | 196 (56.48) | 195 (56.20) | 203 (58.50) | 176 (50.57) | 0.180 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Sepsis (%) | 332 (23.90) | 58 (16.71) | 69 (19.88) | 94 (27.10) | 111 (31.90) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 786 (56.59) | 188 (54.18) | 203 (58.50) | 208 (59.94) | 187 (53.74) | 0.253 |

| Heart failure (%) | 275 (19.80) | 87 (25.07) | 56 (16.14) | 51 (14.70) | 81 (23.28) | 0.001 |

| Arterial fibrillation (%) | 576 (41.48) | 137 (39.48) | 136 (39.19) | 144 (41.50) | 159 (45.69) | 0.277 |

| COPD (%) | 207 (14.90) | 62 (17.87) | 49 (14.12) | 52 (14.99) | 44 (12.64) | 0.264 |

| Diabetes (%) | 442 (31.82) | 143 (41.21) | 102 (29.39) | 78 (22.48) | 119 (34.20) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 825 (59.39) | 215 (61.96) | 214 (61.67) | 201 (57.93) | 195 (56.03) | 0.304 |

| Renal failure (%) | 298 (21.45) | 88 (25.36) | 64 (18.44) | 61 (17.58) | 85 (24.43) | 0.019 |

| Paraplegia (%) | 942 (67.82) | 210 (60.52) | 226 (65.13) | 247 (71.18) | 259 (74.43) | < 0.001 |

| Malignant cancer (%) | 93 (6.70) | 24 (6.92) | 19 (5.48) | 27 (7.78) | 23 (6.61) | 0.679 |

| CCI | 6.45 ± 2.66 | 6.68 ± 2.77 | 6.20 ± 2.72 | 6.20 ± 2.60 | 6.72 ± 2.48 | 0.006 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||

| WBC (109/L) | 9.95 ± 3.94 | 8.82 ± 3.18 | 9.21 ± 3.19 | 10.22 ± 3.91 | 11.56 ± 4.71 | < 0.001 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 4.19 ± 0.68 | 4.20 ± 0.70 | 4.32 ± 0.62 | 4.14 ± 0.64 | 4.11 ± 0.73 | < 0.001 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.52 ± 2.05 | 12.26 ± 2.12 | 12.87 ± 1.90 | 12.55 ± 1.96 | 12.41 ± 2.17 | 0.001 |

| PLT (109/L) | 226.21 ± 80.26 | 232.64 ± 80.86 | 222.16 ± 77.17 | 223.13 ± 81.36 | 226.91 ± 81.48 | 0.302 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.02 ± 0.76 | 1.08 ± 1.08 | 1.01 ± 0.59 | 0.97 ± 0.61 | 1.02 ± 0.65 | 0.319 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 139.25 ± 3.71 | 139.93 ± 3.34 | 139.33 ± 3.78 | 139.22 ± 3.71 | 138.53 ± 3.89 | < 0.001 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.09 ± 0.63 | 4.04 ± 0.61 | 4.11 ± 0.63 | 4.12 ± 0.70 | 4.10 ± 0.58 | 0.397 |

| AG (mEq/L) | 13.88 ± 3.36 | 13.44 ± 3.10 | 13.72 ± 2.75 | 13.80 ± 2.91 | 14.55 ± 4.35 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.10 (1.10,1.30) | 1.20 (1.10,1.30) | 1.10 (1.10,1.20) | 1.10 (1.10,1.20) | 1.20 (1.10,1.30) | 0.253 |

| APTT (s) | 32.76 ± 17.29 | 35.29 ± 21.32 | 31.80 ± 15.54 | 32.02 ± 14.42 | 31.95 ± 16.93 | 0.019 |

| AST (IU/L) | 23.00 (18.00,32.00) | 21.00 (17.00,29.00) | 22.00 (18.00,29.00) | 24.00 (17.00,33.00) | 24.00 (18.00,33.00) | 0.008 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 18.00 (13.00,26.00) | 18.00 (12.00,26.00) | 17.00 (13.00,26.00) | 18.00 (13.00,26.00) | 19.00 (13.00,28.00) | 0.139 |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 132.45 ± 51.31 | 104.67 ± 32.51 | 116.99 ± 31.27 | 130.72 ± 39.04 | 177.29 ± 62.86 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c | 6.24 ± 1.45 | 6.80 ± 1.81 | 6.16 ± 1.22 | 5.95 ± 1.26 | 6.06 ± 1.30 | < 0.001 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 130.97 ± 173.99 | 136.38 ± 186.75 | 134.65 ± 201.31 | 123.66 ± 126.03 | 129.19 ± 173.10 | 0.768 |

| Vital signs | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 144.17 ± 24.19 | 143.06 ± 23.14 | 146.05 ± 24.52 | 144.58 ± 23.14 | 142.98 ± 25.83 | 0.287 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.09 ± 18.46 | 80.51 ± 18.14 | 82.00 ± 18.51 | 80.85 ± 18.54 | 81.01 ± 18.68 | 0.744 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 98.17 ± 17.96 | 97.53 ± 17.33 | 99.12 ± 18.09 | 98.34 ± 17.95 | 97.71 ± 18.49 | 0.646 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 80.38 ± 17.42 | 78.61 ± 15.95 | 78.84 ± 17.51 | 79.49 ± 17.30 | 84.59 ± 18.20 | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate(beats/min) | 18.60 ± 4.85 | 18.37 ± 5.06 | 18.20 ± 4.98 | 18.49 ± 4.64 | 19.33 ± 4.65 | 0.011 |

| Disease severity scores | ||||||

| SOFA | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,2) | 0.027 |

| APSIII | 34.97 ± 14.04 | 32.52 ± 12.86 | 33.21 ± 13.44 | 35.11 ± 14.30 | 39.05 ± 14.62 | < 0.001 |

| GCS | 14 (15,15) | 15 (14,15) | 15 (14,15) | 15 (13,15) | 15 (12,15) | 0.001 |

| Treatments | ||||||

| MT (%) | 42 (3.02) | 6 (1.73) | 9 (2.59) | 16 (4.61) | 11 (3.16) | 0.157 |

| IV-tPA (%) | 106 (7.63) | 27 (7.78) | 28 (8.07) | 33 (9.51) | 18 (5.17) | 0.185 |

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 763 (54.93) | 153 (44.09) | 175 (50.43) | 204 (58.79) | 231 (66.38) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator time (hours) | 4.00 (0.00, 33.50) | 0.00 (0.00, 19.84) | 0.25 (0.00, 23.01) | 7.00 (0.00, 40.10) | 16.73 (0.00, 45.00) | < 0.001 |

| Vasoactive drug (%) | 149 (10.73) | 25 (7.20) | 29 (8.35) | 40 (11.53) | 55 (15.80) | 0.001 |

| Dexmedetomidine (%) | 100 (7.20) | 17 (4.90) | 23 (6.63) | 19 (5.48) | 41 (11.78) | 0.002 |

| Midazolam (%) | 55 (3.96) | 8 (2.31) | 13 (3.75) | 9 (2.59) | 25 (7.18) | 0.003 |

| LOS | ||||||

| LOS ICU (days) | 2.94 (1.78, 5.62) | 2.59 (1.73, 4.83) | 2.70 (1.69, 4.86) | 2.99 (1.88, 5.72) | 3.63 (1.96, 6.90) | < 0.001 |

| LOS hospital (days) | 6.26 (3.65, 11.82) | 5.77 (3.17, 9.99) | 5.23 (3.43, 10.40) | 6.63 (3.86, 11.72) | 8.29 (4.64, 14.98) | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Hospital mortality (%) | 158 (11.38) | 20 (5.76) | 27 (7.78) | 46 (13.26) | 65 (18.68) | < 0.001 |

| PSD (%) | 425 (30.60) | 72 (20.50) | 86 (24.78) | 111 (31.99) | 156 (44.83) | < 0.001 |

SHR stress hyperglycemia ratio, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, PLT platelet, AG anion gap, INR international normalized ratio, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, TG triglyceride, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, MBP mean blood pressure, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, APSIII Acute Physiology Score III, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale, MT mechanical thrombectomy, IV-tPA intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, PSD post-stroke delirium, LOS Length of stay

Baseline characteristics of the non-PSD and PSD groups are shown in Table 2. The SHR levels were markedly elevated in the PSD group compared to the non-PSD group (median 1.05 vs. 0.93, P < 0.001). Patients in the PSD group were older and less likely to be white, with higher WBC, potassium, AG, and AST levels; faster heart and respiratory rates; higher disease severity scores and CCI; higher rates of sepsis, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, and also more frequently required mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, and sedative–analgesic drugs (all P < 0.05), but were less likely to undergo IV-tPA therapy (P = 0.029). Comparison of LOS indicated that patients with PSD had longer durations in both the hospital and ICU (all P < 0.001). All statistically significant parameters (P < 0.05) were considered potential confounders in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to non-PSD and PSD group

| Categories | Overall(n = 1389) | Non-PSD (n = 964) | PSD(n = 425) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 0.97 (0.84,1.15) | 0.93 (0.81,1.11) | 1.05 (0.88,1.27) | < 0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 70.53 ± 14.96 | 69.34 ± 15.11 | 73.21 ± 14.28 | < 0.001 |

| Male (%) | 695 (50.04) | 497 (51.56) | 198 (46.59) | 0.099 |

| White (%) | 770 (55.43) | 564 (58.51) | 206 (48.47) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Sepsis (%) | 332 (23.90) | 131 (13.59) | 201 (47.29) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 786 (56.59) | 556 (57.68) | 230 (54.12) | 0.240 |

| Heart failure (%) | 275 (19.80) | 155 (16.08) | 120 (28.24) | < 0.001 |

| Arterial fibrillation (%) | 576 (41.47) | 358 (37.14) | 218 (51.29) | < 0.001 |

| COPD (%) | 207 (14.90) | 138 (14.32) | 69 (16.24) | 0.399 |

| Diabetes (%) | 442 (31.82) | 301 (31.22) | 141 (33.18) | 0.511 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 825 (59.40) | 569 (59.02) | 256 (60.23) | 0.716 |

| Renal failure (%) | 298 (21.45) | 176 (18.26) | 122 (28.71) | < 0.001 |

| Paraplegia (%) | 942 (67.82) | 599 (62.14) | 343 (80.71) | < 0.001 |

| Malignant cancer (%) | 93 (6.7) | 65 (6.74) | 28 (6.59) | 1.000 |

| CCI | 6.45 ± 2.66 | 6.14 ± 2.62 | 7.16 ± 2.61 | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| WBC (109/L) | 9.95 ± 3.94 | 9.48 ± 3.79 | 11.03 ± 4.07 | < 0.001 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 4.19 ± 0.68 | 4.22 ± 0.66 | 4.13 ± 0.71 | 0.026 |

| Hb (g/dl) | 12.52 ± 2.05 | 12.62 ± 2.00 | 12.31 ± 2.15 | 0.009 |

| PLT (109/L) | 226.21 ± 80.26 | 225.90 ± 77.62 | 226.91 ± 86.04 | 0.828 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.02 ± 0.76 | 1.02 ± 0.81 | 1.02 ± 0.63 | 0.997 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 139.25 ± 3.71 | 139.27 ± 3.39 | 139.22 ± 4.37 | 0.835 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.09 ± 0.63 | 4.06 ± 0.61 | 4.16 ± 0.67 | 0.006 |

| AG (mEq/L) | 13.88 ± 3.36 | 13.52 ± 2.97 | 14.69 ± 4.00 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.10 (1.10,1.30) | 1.10 (1.10,1.20) | 1.20 (1.10,1.30) | 0.568 |

| APTT (s) | 32.76 ± 17.29 | 33.21 ± 17.59 | 31.75 ± 16.58 | 0.149 |

| AST (IU/L) | 23.00 (18.00,32.00) | 22.00 (17.00,30.00) | 24.00 (18.00,34.00) | 0.002 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 18.00 (13.00,26.00) | 18.00 (13.00,26.00) | 18.00 (13.00,27.00) | 0.799 |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 132.45 ± 51.31 | 127.25 ± 46.64 | 144.24 ± 58.95 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c | 6.24 ± 1.45 | 6.23 ± 1.44 | 6.26 ± 1.48 | 0.744 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 130.97 ± 173.99 | 127.73 ± 151.17 | 138.31 ± 217.06 | 0.297 |

| Vital signs | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 144.17 ± 24.19 | 144.20 ± 23.26 | 144.11 ± 26.21 | 0.950 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.09 ± 18.46 | 80.59 ± 17.98 | 82.23 ± 19.47 | 0.127 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 98.17 ± 17.96 | 97.90 ± 17.00 | 98.78 ± 19.98 | 0.400 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 80.38 ± 17.42 | 79.09 ± 16.94 | 83.32 ± 18.13 | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (beats/min) | 18.60 ± 4.85 | 18.18 ± 4.70 | 19.54 ± 5.06 | < 0.001 |

| Disease severity scores | ||||

| SOFA | 0.00 (0.00,1.00) | 0.00 (0.00,1.00) | 1.00 (0.00,2.00) | < 0.001 |

| APSIII | 34.97 ± 14.04 | 32.83 ± 13.91 | 39.84 ± 13.10 | < 0.001 |

| GCS | 15 (14,15) | 15 (14,15) | 14 (12,15) | < 0.001 |

| Treatments | ||||

| MT (%) | 42 (3.02) | 28 (2.90) | 14 (3.29) | 0.825 |

| IV-tPA (%) | 106 (7.63) | 84 (8.71) | 22 (5.18) | 0.029 |

| Mechanical ventilation (%) | 763 (54.93) | 434 (45.02) | 329 (77.41) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator time (hours) | 4.00 (0.00, 33.50) | 0.00 (0.00, 18.40) | 27.00 (2.35, 90.00) | < 0.001 |

| Vasoactive drug (%) | 149 (10.73) | 71 (7.37) | 78 (18.35) | < 0.001 |

| Dexmedetomidine (%) | 100 (7.20) | 21 (2.18) | 79 (18.58) | < 0.001 |

| Midazolam (%) | 55 (3.96) | 24 (2.49) | 31 (7.29) | < 0.001 |

| LOS | ||||

| LOS ICU (days) | 2.94 (1.78, 5.62) | 2.28 (1.65, 4.06) | 5.49 (2.83, 9.99) | < 0.001 |

| LOS hospital (days) | 6.26 (3.65, 11.82) | 5.02 (3.09, 8.57) | 11.78 (6.40, 19.50) | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Hospital mortality (%) | 158(11.38) | 85(8.82) | 73(17.18) | < 0.001 |

SHR stress hyperglycemia ratio, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CCI Charlson comorbidity index, WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, PLT platelet, AG anion gap, INR international normalized ratio, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, TG triglyceride, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, MBP mean blood pressure, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, APSIII Acute Physiology Score III, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale, MT mechanical thrombectomy, IV-tPA intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, LOS Length of stay

Association between SHR and clinical outcomes

We utilized logistic regression analysis to examine the predictive value of SHR in PSD development (Table 3). The data showed that elevated SHR levels were strongly associated with an increased risk of PSD in all three models: the unadjusted model 1 (OR 4.12, 95% CI 2.74–6.25, P < 0.001), partially adjusted model 2 (OR 3.89, 95% CI 2.58–5.93, P < 0.001), and fully adjusted model 3 (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.01–2.86, P = 0.047) when treated as a continuous variable. When analyzed by quartiles, the Q4 group had higher PSD risk than the Q1 group in model 1 (OR 3.10, 95% CI 2.23–4.35, P < 0.001), model 2 (OR 3.11, 95% CI 2.22–4.38, P < 0.001), and model 3 (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.07–2.54, P = 0.024), with a significant trend towards increasing risk as SHR levels increased (all P for trend < 0.05). Consistent findings were noted in both the univariate and multivariate logistic models of SHR and hospital mortality (Table 3). When evaluated either continuously or by quartile stratification, SHR was an independent predictor of hospital mortality (all P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis detecting the predictive value of SHR for clinical outcomes

| Model1 | P value | Model2 | P value | Model3 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | ||||

| PSD | ||||||

| Continuous variable per unit | 4.12 (2.74, 6.25) | < 0.001 | 3.89 (2.58, 5.93) | < 0.001 | 1.69 (1.01, 2.86) | 0.047 |

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Q2 | 1.26 (0.88, 1.80) | 0.206 | 1.30 (0.91, 1.87) | 0.152 | 1.14 (0.73, 1.77) | 0.573 |

| Q3 | 1.80 (1.28, 2.54) | 0.001 | 1.86 (1.32, 2.64) | < 0.001 | 1.36 (0.88, 2.11) | 0.161 |

| Q4 | 3.10 (2.23, 4.35) | < 0.001 | 3.11 (2.22, 4.38) | < 0.001 | 1.64 (1.07, 2.54) | 0.024 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.016 | |||

| Hospital mortality | ||||||

| Continuous variable per unit | 6.01 (3.61, 10.09) | < 0.001 | 5.57 (3.32, 9.43) | < 0.001 | 2.95 (1.64, 5.32) | < 0.001 |

| Quartiles | ||||||

| Q1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Q2 | 1.38 (0.76, 2.54) | 0.292 | 1.45 (0.79, 2.70) | 0.229 | 1.57 (0.81, 3.06) | 0.182 |

| Q3 | 2.50 (1.46, 4.41) | 0.001 | 2.69 (1.56, 4.79) | 0.001 | 2.33 (1.25, 4.45) | 0.009 |

| Q4 | 3.76 (2.26, 6.50) | < 0.001 | 3.83 (2.28, 6.70) | < 0.001 | 2.46 (1.34, 4.63) | 0.004 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | |||

Model 1: unadjusted

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, and race

Model 3: PSD adjusted for age, gender, race, LOS hospital, LOS ICU, sepsis, heart failure, arterial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, CCI, WBC, RBC, Hb, potassium, AG, AST, heart rate, respiratory rate, SOFA, GCS, APSIII, IV-tPA, Ventilator time, vasoactive drugs, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam; Hospital mortality adjusted for age, gender, race, sepsis, heart failure, arterial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, CCI, WBC, RBC, Hb, potassium, AG, AST, heart rate, respiratory rate, SOFA, APSIII, GCS, IV-tPA, Ventilator time, vasoactive drugs, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam

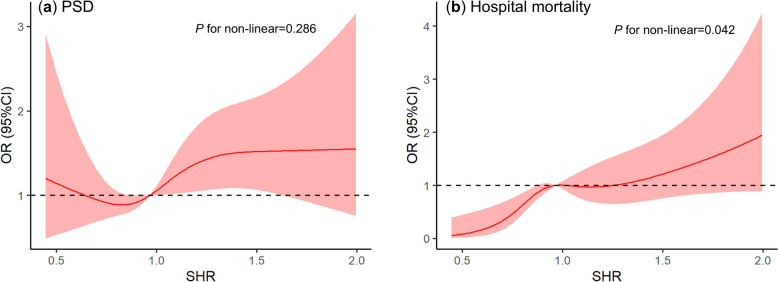

The adjusted RCS analysis indicated that higher SHR levels showed a linear correlation with greater PSD risk (P for non-linearity = 0.286; Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the RCS analysis identified a non-linear, positive association between SHR and hospital mortality (P for nonlinearity = 0.042; Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline analysis of SHR with clinical outcomes. a PSD; b Hospital mortality. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, SHR stress hyperglycemic ratio, PSD post-stroke delirium

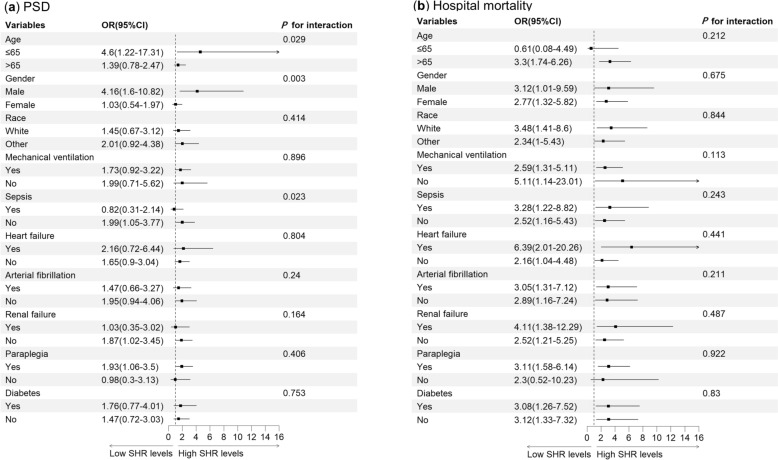

Subgroup analysis

The predictive value of SHR was further evaluated across multiple patient subgroups (Fig. 3). Notably, significant interaction effects were observed for age (P for interaction = 0.029), gender (P for interaction = 0.003), and sepsis (P for interaction = 0.023), suggesting that these factors may moderate the relationship between SHR and PSD. The association was more pronounced in subgroups, such as those aged ≤ 65 years (OR 4.60, 95% CI 1.22–17.31), males (OR 4.16, 95% CI 1.60–10.82), and patients without sepsis (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.05–3.77). No significant interactions were found for other subgroups, including race, mechanical ventilation, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, or diabetes (all P for interaction ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup forest plot for clinical outcomes. a PSD; b Hospital mortality. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, SHR stress hyperglycemic ratio, PSD post-stroke delirium

Subgroup analyses of SHR and hospital mortality showed no statistically significant interaction effects between SHR and any of the grouping factors (all P for interaction ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3b), indicating a consistent association across all subgroups, including those defined by age, gender, race, mechanical ventilation, sepsis, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, renal failure, paraplegia, and diabetes.

Discussion

PSD is a common complication in neurocritical patients. Our retrospective investigation found a 30.60% prevalence of PSD in severe IS cases. Elevated SHR levels were associated with higher PSD incidence. After adjusting for confounders, the linear association remained robust, suggesting that SHR represents a novel and independent predictor of PSD. In addition, SHR levels were significantly associated with hospital mortality, showing a stable non-linear relationship.

SHR has gained recognition as a reliable biomarker of stress hyperglycemia. Clinical studies have reported its association with adverse outcomes in specific populations, particularly cardiovascular disease patients. A recent meta-analysis and systematic review of 32 longitudinal studies suggested that elevated SHR is associated with higher all-cause mortality in cardiovascular patients, regardless of diabetes status [27]. Similar associations were observed in severe sepsis [28, 29], atrial fibrillation [30], and critically ill surgical patients [31]. The prognostic role of SHR in cerebrovascular diseases has also been extensively examined. A Chinese multicenter randomized controlled trial demonstrated that SHR is a predictor of poorer 90-day neurological recovery after acute large vessel occlusion stroke [17]. A prospective, multicenter observational study conducted by Shi et al. further suggested that in endovascular-treated large IS patients, elevated SHR correlates with worse neurological outcomes and higher symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage risk [16]. However, two observational MIMIC database analyses presented different associations between SHR and mortality. Chen et al. reported a linear correlation between SHR and hospital mortality in stroke patients [15], whereas Zhang et al. found a non-linear relationship with 30-day and 90-day mortality in IS patients [14]. This study also observed a non-linear association between SHR and mortality. These inter-study variations may stem from differences in inclusion/exclusion criteria and analytical approaches. Our current study employed stricter inclusion criteria by enrolling only patients with a primary diagnosis of IS, resulting in a relatively small but more rigorous enrolment population. However, as a retrospective cohort study, the observed associations require further validation through prospective investigations.

Glucose dysregulation is a recognized risk factor for delirium in the elderly [32] and ICU populations [33]. However, existing research on stress hyperglycemia and delirium has primarily examined surgical settings. A recent review reported that perioperative hyperglycemia is independently associated with increased incidence of postoperative delirium, especially in geriatric populations [34]. This association has been consistently observed across various surgical populations, such as patients receiving general thoracic surgery [35], coronary artery bypass grafting surgery [36, 37], acute aortic dissection surgery [38], and hip fracture surgery [39].

Despite this, few investigations have assessed the link between stress hyperglycemia and delirium outside surgical environments. An observational cohort study found a non-linear relationship between SHR and delirium among individuals ≥ 70 years of age, but only in those with HbA1c < 6.5% [40]. Liao et al. indicated that SHR may serve as a risk factor for delirium in elderly community-acquired pneumonia patients through a retrospective analysis [41]. This study represents the first exploration of the SHR–PSD relationship. Subgroup analyses suggested that this association varies significantly by age, gender, and sepsis status, providing important directions for future research.

The pathogenesis of delirium remains incompletely understood. Current evidence suggests that systemic inflammatory activation and cytokine dysregulation play crucial roles in delirium onset [6, 42]. Stress hyperglycemia shares common pathogenic mechanisms with inflammation, as both involve cytokine release, including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α [11, 43]. These conditions may form a vicious cycle that amplifies cytokine production [44]. The released cytokines can impair blood–brain barrier integrity, inducing neuroinflammation and disrupting neural networks [45, 46]. Furthermore, stress hyperglycemia results from heightened adrenal axis reactivity, excessive cortisol production, and glucocorticoid use—all factors that may cause cognitive and psychiatric impairments, including mood and memory disorders [47]. Stress hyperglycemia may also directly induce oxidative stress and intracranial endothelial dysfunction [9]. The interplay of these mechanisms ultimately contributes to delirium development.

Numerous studies have indicated that PSD may contribute to increased mortality, whether assessed over brief or extended periods [48–50]. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies suggested that PSD correlates with mortality and poor neurological outcomes, even after adjusting for pre-specified confounders [8]. Thus, early intervention for high-risk PSD patients may improve IS prognosis. Since PSD prevention relies more on management than medical treatment, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) recommends the ABCDEF bundle as the optimal strategy for critically ill delirium individuals [51]. The updated Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption (PADIS) guidelines further highlight subtype-specific delirium management, dexmedetomidine-based light sedation, and physical–psychological interventions [52].

This study found an easily accessible indicator for early PSD prevention and management. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, since all data were extracted from the MIMIC database, half of the participants in this single-center study were white, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Second, although we accounted for numerous potential risk factors for delirium, unmeasured confounders may still influence the outcomes. Third, due to the inherent limitations of our retrospective observational design, this study cannot establish causality. Future large-scale prospective studies are required for validation. Fourth, since stress hyperglycemia fluctuates rapidly during acute illness, further investigation is needed to determine whether SHR variability impacts PSD development.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings have important clinical implications. While this study reported SHR as an independent predictor of PSD, the adjusted ORs indicate a moderate strength of association. Therefore, SHR may be most valuable not as a standalone marker, but as part of a comprehensive risk-stratification strategy. Its clinical utility lies in its simplicity and rapid availability at admission, aiding clinicians in identifying high-risk patients who may benefit from closer monitoring and early application of delirium-prevention measures.

To improve predictive accuracy, future research should explore combining SHR with other relevant markers—such as inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., C-reactive protein or interleukin-6) and neuroimaging parameters (e.g., infarct volume, location, or pre-existing cerebral atrophy) [53]. Such a multifactorial model could offer more robust risk stratification and a more complete pathophysiological understanding, potentially leading to more precise clinical interventions.

Conclusions

This research observed a significant linear positive relationship between SHR levels and PSD development in critically ill patients with IS. Moreover, increased SHR levels were associated with greater hospital mortality. Early prevention and management in high-risk populations may decrease both PSD occurrence and hospital mortality. Future prospective trials should be conducted to verify these observations.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the MIMIC-IV program registry for providing and maintaining the MIMIC-IV database.

Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- PSD

Post-stroke delirium

- IS

Ischemic stroke

- SHR

Stress hyperglycemia ratio

- MIMIC

Medical information mart for intensive care

- NIH

National institutes of health

- CITI

Collaborative institutional training initiative

- ICD

International classification of diseases

- SQL

Structured query language

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- SOFA

Sequential organ failure assessment

- APSIII

Acute physiology score III

- MT

Mechanical thrombectomy

- IV-tPA

Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator

- CAM–ICU

Confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit

- IQR

Interquartile range

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

- RCS

Restricted cubic spline

- SCCM

Society of critical care medicine

- PADIS

Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption

Author contributions

PX and JW designed the study. JZ, GL, and CF extracted, collected, and analyzed data. The initial manuscript draft was prepared by JZ and subsequently revised by YF. Each author made equal contributions to the manuscript and consented to its publication.

Funding

None.

Data availability

All relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available from [https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/](https:/physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1). Following the completion of the training course provided by the NIH and successful passage of the CITI program, author Junhui Zou acquired database access (No. 66659928).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors gave their consent to publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Peng Xu, Email: nut8479@163.com.

Jun Wang, Email: wjgaogou@aliyun.com.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vlisides P, Avidan M. Recent advances in preventing and managing postoperative delirium. F1000Res. 2019. 10.12688/f1000research.16780.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mart MF, Roberson SW, Salas B, Pandharipande PP, Ely EW. Prevention and management of delirium in the intensive care unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42(1):112–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibb K, Seeley A, Quinn T, Siddiqi N, Shenkin S, Rockwood K, et al. The consistent burden in published estimates of delirium occurrence in medical inpatients over four decades: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Age Ageing. 2020;49(3):352–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, Shehabi Y, Girard TD, Maclullich AM, et al. Delirium. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu SB, Wu HY, Duan ML, Yang RL, Ji CH, Liu JJ, et al. Delirium in the ICU: how much do we know? A narrative review. Ann Med. 2024;56(1):2405072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang GB, Li HY, Yu WJ, Ying YZ, Zheng D, Zhang XK, et al. Occurrence and risk factors for post-stroke delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2024;99:104132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang GB, Lv JM, Yu WJ, Li HY, Wu L, Zhang SL, et al. The associations of post-stroke delirium with outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1798–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Yue K, Jiang Z, Wu X, Li X, Luo P, et al. Incidence of stress-induced hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 2023;13(4):556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagonigro E, Pansini A, Mone P, Guerra G, Komici K, Fantini C. The role of stress hyperglycemia on delirium onset. J Clin Med. 2025;14(2):407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Zeng X, Zou W, Chen M, Fan Y, Huang P. Predictive performance of stress hyperglycemia ratio for poor prognosis in critically ill patients: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts GW, Quinn SJ, Valentine N, Alhawassi T, O’Dea H, Stranks SN, et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Yin X, Liu T, Ji W, Wang G. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):20962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Xu J, He F, Huang AA, Wang J, Liu B, et al. Assessment of stress hyperglycemia ratio to predict all-cause mortality in patients with critical cerebrovascular disease: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi X, Yang S, Guo C, Sun W, Song J, Fan S, et al. Impact of stress hyperglycemia on outcomes in patients with large ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2024. 10.1136/jnis-2024-021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng Z, Song J, Li L, Guo C, Yang J, Kong W, et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia and outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023;29(8):2162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Guo L, Zhou Y, Yuan C, Yin Y. Stress hyperglycemia ratio as an important predictive indicator for severe disturbance of consciousness and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with cerebral infarction: a retrospective study using the MIMIC-IV database. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson AE, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, Gayles A, Shammout A, Horng S, et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ormseth CH, Lahue SC, Oldham MA, Josephson SA, Whitaker E, Douglas VC. Predisposing and precipitating factors associated with delirium: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2249950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shehabi Y, Howe BD, Bellomo R, Arabi YM, Bailey M, Bass FE, et al. Early sedation with dexmedetomidine in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2506–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC, White IR, Lee DS, Van Buuren S. Missing data in clinical research: a tutorial on multiple imputation. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(9):1322–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh M, Hamer O, Hill J. Diagnostic test accuracy of assessment tools for detecting delirium in patients with acute stroke: commentary of a systematic review. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2022;18(Sup5):S18-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laney LJ, Elliott R. Sleep disturbance in ICU: a pathway to delirium. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2025;90:104138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bo M, Bonetto M, Bottignole G, Porrino P, Coppo E, Tibaldi M, et al. Length of stay in the emergency department and occurrence of delirium in older medical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(5):1114–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pérez-Ros P, Plaza-Ortega N, Martínez-Arnau FM. Mortality risk following delirium in older inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2025;22(3):e70027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esdaile H, Khan S, Mayet J, Oliver N, Reddy M, Shah AS. The association between the stress hyperglycaemia ratio and mortality in cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan F, Chen X, Quan X, Wang L, Wei X, Zhu J. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study and predictive model establishment based on machine learning. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S, Shen H, Wang Y, Ning M, Zhou J, Liang X, et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: results from the MIMIC-IV database. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Q, Yang J, Wang W, Shao C, Hua X, Tang YD. The impact of the stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality and rehospitalization rate in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Yan Y, Sun L, Wang Y. Stress hyperglycemia ratio is a risk factor for mortality in trauma and surgical intensive care patients: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Keulen K, Knol W, Belitser SV, Van Der Linden PD, Heerdink ER, Egberts TC, et al. Diabetes and glucose dysregulation and transition to delirium in ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han Y, Ji B, Leng Y, Xie C. Inhibited hypoxia-inducible factor by intraoperative hyperglycemia increased postoperative delirium of aged patients: a review. Medicine. 2024;103(22):e38349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Özyurtkan MO, Yildizeli B, Kukuşçu K, Bekiroğlu N, Bostanci K, Batirel HF, et al. Postoperative psychiatric disorders in general thoracic surgery: incidence, risk factors and outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37(5):1152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirvani F, Sedighi M, Shahzamani M. Metabolic disturbance affects postoperative cognitive function in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(1):667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen H, Zhang P. The relationship between stress hyperglycemia ratio and the risk of delirium in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin YJ, Lin LY, Peng YC, Zhang HR, Chen LW, Huang XZ, et al. Association between glucose variability and postoperative delirium in acute aortic dissection patients: an observational study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu K, Song Y, Yuan Y, Li Z, Wang X, Zhang W, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus with tight glucose control and poor pre-injury stair climbing capacity may predict postoperative delirium: a secondary analysis. Brain Sci. 2022;12(7):951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song Q, Dai M, Zhao Y, Lin T, Huang L, Yue J. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and delirium in older hospitalized patients: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao J, Xie C, Shen X, Miao L. Predicting delirium in older adults with community-acquired pneumonia: a retrospective analysis of stress hyperglycemia ratio and its interactions with nutrition and inflammation. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2025;129:105658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Prasad NK, Shekhar A, Campbell NL, Gao S, et al. Biomarkers of delirium duration and delirium severity in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(3):353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arcambal A, Taïlé J, Rondeau P, Viranaïcken W, Meilhac O, Gonthier MP. Hyperglycemia modulates redox, inflammatory and vasoactive markers through specific signaling pathways in cerebral endothelial cells: insights on insulin protective action. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;130:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barth E, Albuszies G, Baumgart K, Matejovic M, Wachter U, Vogt J, et al. Glucose metabolism and catecholamines. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):S508–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cortese GP, Burger C. Neuroinflammatory challenges compromise neuronal function in the aging brain: postoperative cognitive delirium and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2017;322:269–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kealy J, Murray C, Griffin EW, Lopez-Rodriguez AB, Healy D, Tortorelli LS, et al. Acute inflammation alters brain energy metabolism in mice and humans: role in suppressed spontaneous activity, impaired cognition, and delirium. J Neurosci. 2020;40(29):5681–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris MA, Cox SR, Brett CE, Deary IJ, Maclullich AM. Cognitive ability across the life course and cortisol levels in older age. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;59:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pasińska P, Wilk A, Kowalska K, Szyper-Maciejowska A, Klimkowicz-Mrowiec A. The long-term prognosis of patients with delirium in the acute phase of stroke: PRospective observational POLIsh study (PROPOLIS). J Neurol. 2019;266:2710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rollo E, Brunetti V, Scala I, Callea A, Marotta J, Vollono C, et al. Impact of delirium on the outcome of stroke: a prospective, observational, cohort study. J Neurol. 2022;269(12):6467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dostovic Z, Smajlovic D, Ibrahimagic OC, Dostovic A. Mortality and functional disability of poststroke delirium. Mater Sociomed. 2018;30(2):95–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stollings JL, Kotfis K, Chanques G, Pun BT, Pandharipande PP, Ely EW. Delirium in critical illness: clinical manifestations, outcomes, and management. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(10):1089–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis K, Balas MC, Stollings JL, McNett M, Girard TD, Chanques G, et al. A focused update to the clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, anxiety, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2025;53(3):e711–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batra A, Chou SH. Advances in neurocritical care of stroke: present and future. Stroke. 2024;55(10):2528–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available from [https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/](https:/physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1). Following the completion of the training course provided by the NIH and successful passage of the CITI program, author Junhui Zou acquired database access (No. 66659928).