Abstract

Dementia is increasing globally, expected to affect 153 million people by 2050. Dance is an emerging non-pharmacological evidence-based intervention, that integrates artistic, aesthetic, and physical exercise domains. This umbrella review synthesizes evidence on the effects of dance on brain health in older adults with mild-cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis were selected according to the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome): older adults with MCI or dementia; dance interventions; comparison with no intervention or other types of interventions; brain health outcomes (cognitive, physical, and emotional domains). The 10 included systematic reviews indicated potential benefit of dance on cognition, compared to control conditions. The meta-analysis of meta-analysis showed significant effects on global cognition, increasing MoCA (SMD = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.91, p < 0,001) with high heterogeneity (I² = 67%); MMSE scores (SMD = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.27 to 0.47, p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I² = 0%); and, combined MMSE (SMD = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.87, p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Significant effects were also observed on cognitive domains, improving TMT-A scores (SMD = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10 to 0.36, p < 0,01) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 36.7%); and, TMT-B scores (SMD = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.32, p < 0,01) with low heterogeneity (I² = 8%). The overall quality of evidence remains weak: 3 included systematic reviews were rated as critically low-quality, and 7 as low quality. While dance interventions are promising for supporting brain health in older adults with MCI, few systematic reviews have focused on people with dementia. This umbrella review provides a comprehensive evidence synthesis and highlights critical research gaps. Future work should focus on establishing methodological rigor, expanding studies on dementia, and integrating dance into broader brain health frameworks through global, collaborative efforts. Registration: PROSPERO, CRD42024503578.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06483-7.

Keywords: Dance, Dementia, Cognition, Umbrella review, Brain health, Aging

Introduction

Dementia is increasing globally, expected to affect nearly 153 million people worldwide by 2050 [1, 2]. Dementia is a leading cause of disability, dependency, and death, impacting individuals, loved ones, healthcare systems, and society at large in countless physical, psychological, and financial ways [3, 4]. The annual global societal costs of dementia are estimated to be U$1.3 trillion, and this number is projected to double by 2030.

Non- pharmacological interventions play a critical role in addressing the cognitive, emotional, and functional needs of individuals with dementia and their caregivers [5]. Dance is a non-pharmacological evidence-based intervention that integrates artistic, aesthetic, and physical domains, holding cultural and emotional meaning. As a multimodal activity, dance couples multiple cognitive tasks, aerobic exercise and social engagement, gaining recognition among older adults [6], people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [7, 8] and people living with dementia [9, 10]. Dance is often cited as the preferred physical activity among diverse older adults [11]. Evidence highlights dance’s potential to enhance brain health by improving motor function, well-being, and cognition while reducing depression through aerobic fitness and creative engagement [12–21]. In addition to global cognition [6–8], dance interventions have also shown benefits on visuospatial ability, attention and recall abilities [7] in older people with MCI. Additionally, social engagement, positive mood, and physical activity are three of 14 modifiable risk factors for dementia [22], emphasizing the potential benefit of dance for brain health across the life course.

Despite this growing recognition of dance as influential on cognitive, physical and emotional domains of aging, there remains a paucity of understanding of the holistic impact of dance on brain health, hindering comparative analysis and evidence-informed practice recommendations. Dance, as a multi-modal activity, encompasses not only diverse types of interventional application, but also diverse delivery genres, such as social, folk, tap, and co-creative dance, among others. Additionally, from an epidemiological perspective, MCI and dementia present different clinical phenotypes making it difficult to systematically assess whether dance influences the trajectory and evolution of the syndromes.

Considering these complexities and the large number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the topic, this umbrella review aims to summarize the existing evidence on the effects of dance interventions on brain health (cognitive, physical, and emotional domains) of older people with MCI and dementia, evaluating systematic reviews and meta-analyses quality and providing standardized evidence. The resulting analysis will synthesize the evidence pertaining to the impact of dance on brain health, to inform evidence-based best practices as well as to identify gaps and need for further research.

Methods

Study design

This umbrella review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) [23]. In addition, it was registered in the International Prospective Registry of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), under the identifier CRD42024503578 [24, 25].

Eligibility criteria

According to the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) framework: Population: individuals ≥ 60 years old with MCI or dementia; Intervention: various dance interventions; Comparison: no intervention or other types of interventions; Outcomes: brain health (cognitive, physical, and emotional domains). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses written in English or Spanish were included if they analyzed randomized clinical trials, non-randomized clinical trials or quasi-experimental studies. No restrictions were placed on publication date. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded if they: (1) analyzed case-studies, protocols, case series or observational studies; (2) had no full text available, (3) included populations with diseases other than MCI or dementia and, (4) involved interventions that are not dance.

Search strategies

The systematic reviews were selected from PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and PsycINFO, extracting results from database inception through September 2024 and updated in May 2025. Relevant systematic reviews were identified through manual searches of the references cited in systematic reviews. A librarian provided specialized expertise, refining search strategies and enhancing the efficiency of database navigation.

The following keywords were used in the search strategy: “Aged”, “Older Adults”, “Health of the Elderly”, “Elderly”, “Dance”, “Dancing”, “Dance therapy”, “Cognitive Dysfunction”, “Cognitive Impairment”, “Cognitive Disorder”, “Mild Cognitive Impairment”, “Cognitive Decline”, “Mental Deterioration”, “Mental Health”, “Brain Health”, “Dementia”, “Amentia”, “Familial Dementia”, “Systematic Review”. The complete search strategy is available in a supplementary material (S) S1.

Study selection

Two independent and blinded reviewers (RAP and DS) screened titles and abstracts, and full-text articles using Covidence software. The reference lists of all relevant articles were also examined to identify additional eligible systematic reviews. Any disagreements between the reviewers were solved by a third reviewer (MK).

Data extraction

Standardized data extraction was conducted using a standardized approach by two independent and blinded reviewers (RAP and DS). In the case of disagreement, a third reviewer (MK) resolved the discrepancies.

The extracted information included the methodological characteristics of the included systematic reviews: title, authors and date, type of studies, population characteristics (age, sex), geographical location where the systematic reviews were conducted, intervention (duration, intensity, type), comparator and outcomes. The primary outcome were brain health domains - cognition, functional mobility, anxiety, depression, and loneliness [26].

Outcomes

This umbrella review included all systematic reviews addressing the effects of dance interventions on brain health in older adults with MCI or dementia. The following characteristics were considered for these key variables:

Dance interventions

Multiple dance styles that involves learning, attention, memory, emotion, rhythmic motor coordination, balance, gait, visuospatial ability, acoustic stimulation, imagination, improvisation, and social interaction [27].

Brain health

Defined as a “life-long dynamic state of cognitive, emotional and motor domains underpinned by physiological processes”, is “multidimensional and can be objectively measured and subjectively experienced”[26] .

Cognition

Ability to perceive, learn, plan and execute things, to communicate and express oneself through language and verbal skills [28].

Mild cognitive impairment

Transitional stage between healthy cognitive aging and dementia [29].

Dementia

Significant cognitive decline that interferes in autonomy in daily life activities [30].

Meta-analyses

The systematic reviews were summarized overall and by specific cognitive outcomes. A second-order meta-analysis (i.e., a meta-analysis of meta-analyses) was conducted to synthesize the results reported in the included systematic reviews. To enable comparability across studies that reported outcomes using different measurement scales, mean differences (MD) were converted to standardized mean differences (SMD). This transformation was necessary because some studies used different units or scales to assess the same underlying constructs (e.g., global cognition or executive function). For studies reporting MD along with sample sizes and confidence intervals, we first estimated the standard error of the MD using the width of the confidence interval. We then computed the pooled standard deviation based on the sample sizes of the intervention and control groups. Finally, the MD was divided by the pooled standard deviation to obtain the corresponding SMD. This standardization allows us to meta-analyze both MD- and SMD-based studies together and to interpret all effect sizes on a common, unitless scale. Difference between cognitive outcomes, including Trail Making Test A (TMT-A), Trail Making Test B (TMT-B), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and combined global cognition scores, were synthesized in random effects models and presented in forest plots as standardized differences in effect size. For timed tests, the direction of effect sizes was harmonized by multiplying values by − 1, so higher scores uniformly reflected better performance. Meta-analyses were conducted when at least three systematic reviews employed the same assessment. Heterogeneity was accessed by I² and was considered low (< 25%), moderate (between 25% and 50%) and high (> 50%). Additionally, meta-regressions were conducted to evaluate the influence of variables such as gender, level of cognitive impairment, time from diagnosis, type of diagnosis, and type of intervention on the cognitive outcomes, when sufficient data were available. All statistical analyses were performed using Metafor Package in the RStudio 2022.02.3.

Methodological quality and certainty of evidence

The methodological quality of each systematic review was evaluated using the Assessment of Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2), a tool that provides overall confidence ratings based on methodological rigor [31]. AMSTAR 2 evaluates quality across 16 specific criteria, including critical domains essential for determining the reliability and validity of the systematic review. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [32] was applied to assess the certainty of evidence and strength of the results. GRADE evaluates evidence considering four domains: objectivity, consistency, accuracy and reporting bias and the scores range from very low, low, moderate, and high.

Results

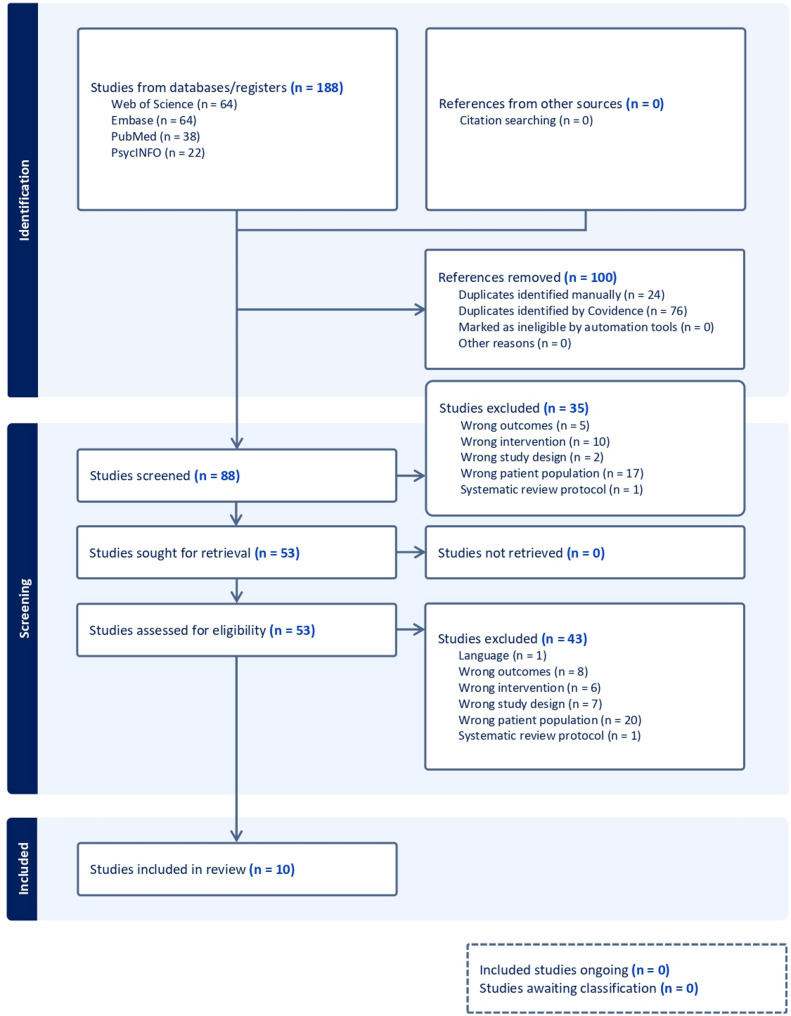

A systematic search initially identified 188 studies. Ten systematic reviews and meta-analyses met eligibility criteria for data extraction. The entire process, from database search to final inclusion of systematic reviews is described in Fig. 1. Details of the studies excluded during the full-text eligibility phase are provided in the supplementary file S2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Characteristics of the systematic reviews

The characteristics of the included systematic reviews are summarized in the supplementary file S3.

The systematic reviews were published between 2018 and 2023, with four published in 2021 [33–36]. Most of them were conducted in China [8, 36–40], several involved collaborations: Hong Kong, USA and China [37]; Colombia and Spain [41], and Singapore and Norway [34], one was in Singapore[35], and another in Canada [33].

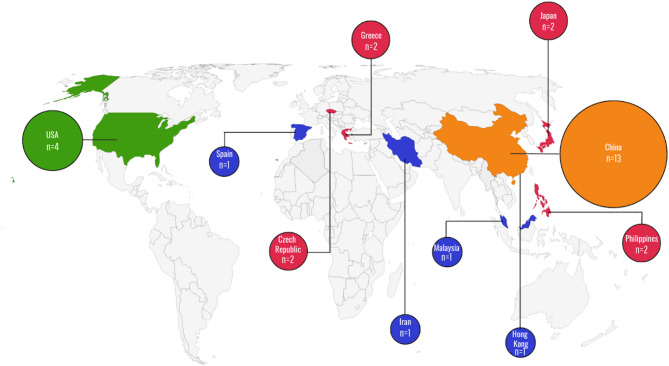

The distribution of individual studies (N = 29 for the 10 systematic reviews), can be seen in Fig. 2. Most of them (13) were in China and the geographic distribution is notable concentrated in the Global North.

Fig. 2.

Geographic distribution of included individual studies in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Geographic distribution of N=29 individual studies reported in the 10 systematic reviews which matched the inclusion criteria in the umbrella review ((P: MCI/Dementia; I: Dance; O: Cognition) represent a paucity of studies from the global south

Participants’ characteristics and interventions

The characteristics of the participants and interventions of the included systematic reviews are summarized in the supplementary file S4.

The total sample comprised 6,343 participants, with an average age ranging from over 60 to 85 years. Most participants were women.

The reviewed systematic reviews encompassed a diverse range of dance genres, including ballroom (all studies), salsa and tango [34, 37, 40], square dance [8, 34, 36, 37, 39, 41], modern dance [37], aerobic dance [8, 33, 36, 37, 39, 41], folk dance [34, 36–38], and dance therapy [37]. Details of the Dance Intervention Diversity and Distribution in the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses are provided in the supplementary file S5.

All the systematic reviews demonstrated the potential of dance on cognitive domains. However, some results are heterogeneous [41], indicating the presence of significant and non-significant findings.

The interventions ranged from 6 weeks to one year with a frequency of 1 to 7 times a week and ranging from 20 to 120 min. All systematic reviews showed results comparing dance intervention with a control group [8, 33–41], and 7 with active control groups [8, 34, 36, 38–41].

Outcomes and instruments

A broad range of cognitive domains were assessed, including cognitive function, memory, attention, and executive function. Various instruments were utilized, including global cognitive measures, such as the MMSE, MoCA, and Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog). Additionally, a variety of other cognitive tests that measured specific cognitive domains were employed.

Global cognition was examined in all systematic reviews, with MMSE and MoCA being the most used instruments. Positive effects of dance interventions on global cognition were consistently reported. However, Vega-Ávila et al. [41] found heterogeneous results.

Several cognitive domains were explored, including: Attention [8, 33–36, 39, 41] Executive functions [8, 33, 35–38, 40, 41] Language [8, 34–36, 41] Memory [8, 33–41]; Perceptual-motor function [35].

Memory was primarily assessed using the RBMT- Rivermead Behavioural Memory test [8, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41]. Short-term memory and immediate recall were assessed by DST - Digit Span Test [8, 33–35, 37, 39–41], and the WMS - Wechsler Memory Scale, to evaluate auditory, visual, and visual working memory [8, 33–35, 37, 40, 41]. The majority of the systematic reviews showed improvements on memory, except one [33] that showed little to no effects on this domain. However, the memory improvements were shown by different instruments and measures (e.g. delayed or immediate recall).

The TMT - Trail Making test A and B were listed in all systematic reviews to assess executive function, attention, psychomotor speed, and cognitive flexibility. Dance interventions showed improvements in attention and psychomotor speed [36, 39]. Enhancements in executive functions and cognitive flexibility were also reported [39, 40].

Most systematic reviews assessed quality of life (QoL), with the Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-36) and 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) [8, 34, 36]. Mixed results were observed for overall QoL, with Huang et al.[8] reporting both positive and non-significant outcomes, while Wu et al. [34] and Liu et al.[36] reported non-significant results. However, subgroup analysis using the SF-12 revealed a positive effect of dance on QoL [34, 36].

Four systematic reviews analyzed mental health, specifically depression and anxiety. Depression was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [8, 34, 36, 37] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) - depression subscale [8, 34, 36]. Dance demonstrated a positive impact, reducing depression levels in three systematic reviews [8, 36, 38], while one systematic review reported weak and non-significant effects [34]. Anxiety was assessed using the HADS - anxiety subscale [8, 36]. Two systematic reviews suggested potential effects of dance interventions in reducing anxiety [8, 36] while one study reported mixed findings [36]. Physical outcomes were also evaluated in some systematic reviews, focusing on balance and functional mobility.

Balance was measured using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) in four systematic reviews [34, 36, 37, 39]. Functional mobility was assessed by the Timed Up and Go test (TUG) in two systematic reviews [34, 36]. The results for physical outcomes were controversial. While some systematic reviews reported improvements in balance and functional mobility [37, 39], others found non-significant or mixed effects [34, 36].

All the outcomes and instruments used in the included studies are available in the supplementary file S6.

Certainty of evidence

Overall, the certainty of evidence in the global cognition and cognitive domains ranged from low to very low, with all systematic reviews presenting very low evidence for global cognition evaluated by MMSE and MoCA. One systematic review [40] provided low-quality evidence for global cognition assessed using the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-cog).

Regarding executive function, 10% of the systematic reviews showed high certainty of evidence [38], 40% low certainty [8, 34, 36, 39], and 50% very low certainty[33, 35, 37, 40, 41].

Other cognitive domains demonstrated moderate evidence on memory [8, 33, 40], complex attention [33], verbal fluency [40] and language [34].

Heterogeneity among studies was identified as the primary source of bias. Most systematic reviews exhibited a risk of bias, except one [38] which showed no significant bias.

The certainty of evidence assessment is available in the supplementary file S7.

Meta-analyses

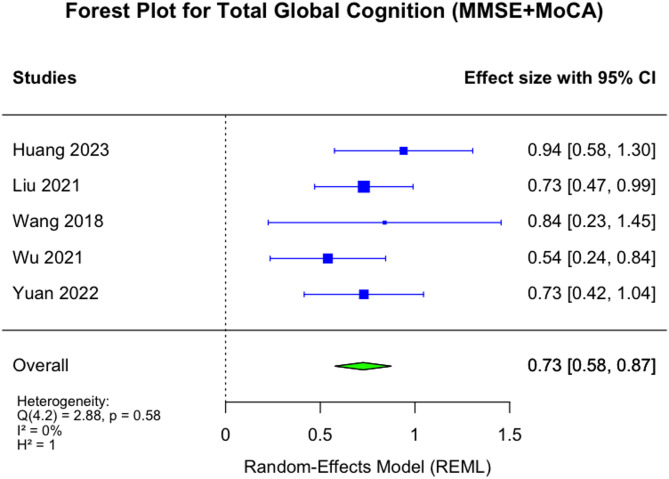

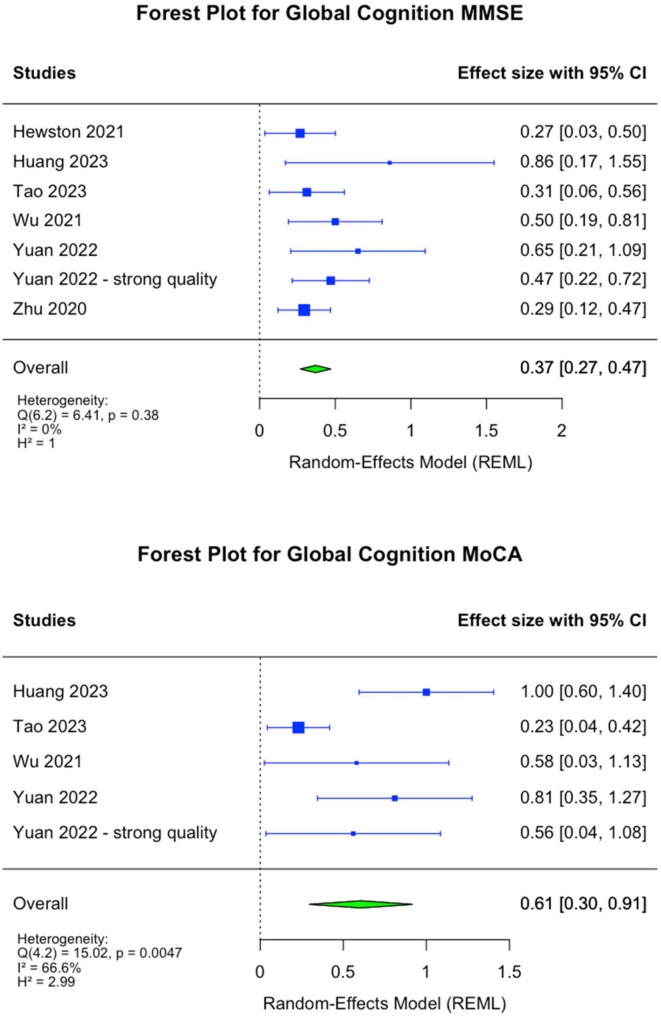

Effect sizes representing the standardized mean difference (SMD) between interventions are presented in Figs. 3, 4 and 5 with 95% confidence intervals and an overall pooled estimates. Meta-analyses showed significant effects of dance intervention on global cognition. The MoCA scores increased (SMD = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.91, p < 0,001) with high heterogeneity (I² = 66.6%); MMSE scores increased (SMD = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.27 to 0.47, p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I² = 0%); and, combined MMSE and MoCA scores increased (SMD = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.87, p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Significant effects were also observed on cognitive domains. The TMT-A scores improved (SMD = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10 to 0.36, p < 0,01) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 36.7%); and, TMT-B scores improved (SMD = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.32, p < 0,01) with low heterogeneity (I² = 8%). However, the observed heterogeneity should be interpreted with caution, as it may be influenced by the small amount of variability between studies and the small number of systematic reviews included in each meta-analyses [42].

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of global cognition (MMSE + MoCA) showing a significant positive effect of dance interventions

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of MMSE and MoCA changes analyzed separately, showing significant positive effects of dance interventions

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of changes in TMT-A and TMT-B showing significant positive effects of dance interventions. TMT-A and TMT-B were analyzed separately. The direction was harmonized by multiplying values by –1

Methodological quality

Three systematic reviews were classified as critically-low [8, 33, 40] while seven were rated as low [34–39, 41]. The most critical methodological weaknesses identified were the absence of a comprehensive literature search strategy and the failure to provide a list of excluded studies with accompanying justifications for their exclusion. The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews is available in the supplementary file S8.

The included systematic reviews demonstrated substantial overlap, indicating that several reviews included the same primary studies. Substantial overlap was observed between Huang et al. [8] [ and Yuan et al. [39] , as well as, between Liu et al. [36] and Tao et al. [37] , with each pair sharing eight overlapping studies. Of the 29 individual studies included across the 10 systematic reviews and meta-analyses assessed, five were repeatedly cited in most reviews: Lazarou et al.[43] was included in all systematic reviews (10); Doi et al. [44] was included in 8 out of 10; and Bisbe et al. [12], Qi et al. [45] and Zhu et al. [21] were each included in 6 out of 10 systematic reviews. The detailed overlap of included studies across systematic reviews and meta-analyses is presented in supplementary file S9.

Discussion

This umbrella review synthesizes evidence on the effects of dance on brain health outcomes in older people with MCI and dementia, showing significant improvements in global cognition and in some cognitive domains, such as memory, attention, psychomotor speed, executive function and cognitive flexibility. Dance has also shown positive effects on quality of life, depression, and anxiety, though findings on balance and functional mobility have been inconsistent.

Several systematic reviews showed dance benefits on brain health in people with MCI, but few examine people with dementia. Despite the quality and scope limitations of the included systematic reviews, this umbrella review provides a comprehensive overview of the current evidence and highlights critical areas for future exploration.

Quality of evidence

The overall quality of evidence supporting the effects of dance on cognition remains weak. Most cognitive domains had very low to low certainty of evidence, except for executive function and memory, with moderate to high certainty. These domains showed the most consistent positive outcomes, though study heterogeneity limits definitive conclusions. Global cognition, psychomotor speed and attention were the highest-consistent outcomes, but the need to further explore specific cognitive domains remains critical.

Population representation and context

Most of the systematic reviews originated from high-income countries, leaving the effectiveness of dance interventions unexplored in other regions, limiting generalizability to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where dementia is rapidly increasing [3, 46, 47]. In many LMICs, dance is already an integral part of daily life and cultural expression, which may influence both the acceptance and potential benefits of such interventions. However, this rich cultural dimension remains understudied, highlighting the need for further research to explore its impact and potential applications for brain health and dementia prevention.

Additionally, variables such as participants’ educational levels, socioeconomic status, and ethnic backgrounds were often underreported, highlighting significant gaps in representation considering that these factors can be relevant to decreased cognition and treatment access. These aspects are part of the 14 modifiable risk factors that influence brain health outcomes and should be prioritized in future research to ensure inclusivity and relevance [22]. Disclosing key variables (e.g., medications, comorbidities, environment) in reviews helps eliminate confounders and clarify evidence on brain health.

Intervention heterogeneity and standardization

Dance interventions varied widely in genre, intensity, and duration. The lack of standardized and well-described protocols limits replicability and accuracy of assessments. The absence of consensus on appropriate dosing and interventions underscores the need for rigorous and uniform guidelines in the design and reporting of dance studies, emphasizing that detailed reporting of protocols is crucial to improving replicability and comparability across studies. The role of novelty and participants’ dance experience remains an unexplored area with significant implications for tailoring interventions to individual needs.

Dance is an art form and involves creativity, aesthetics, embodiment, identity, belonging, affection, self-awareness, engagement and social interaction. [10, 48, 49, 56],. Studies illustrated the multiple cognitive [50, 51], emotional [52, 53] and social [54–56] domains addressed and encompassing multiple dance genres [50, 57, 58]. Given its popularity and high adherence rates, dance is considered a valuable non-pharmacological intervention to combat cognitive decline in people with neurodegenerative conditions [7, 51]. Dance interventions benefit older adults’ brain health, improving global cognition and memory, increasing hippocampal and gray matter volume in the left precentral and para hippocampal gyrus (crucial areas for memory and other cognitive processes) and altering peripheral neurotrophic factors (which play a role in neuronal growth and survival) [51].

All these aspects are not isolated and can influence each other. While this complexity is a strength, it is also a challenge for research design and analysis. To ensure consistency, applicability and replicability of future research, a multisectoral and interdisciplinary consensus is needed on a framework of dance within brain health that embraces this complexity while offering clear consensus on models, guidelines and analysis.

Comparators

To maximize determination of dance within the larger framework of exercise, arts and health/social interventions, comparators in future studies should represent a diversity of existing and accepted interventions for individuals living with MCI and dementia. Currently, the comparators are heterogeneous, with most involving no intervention or health education programs. Observing the comparators it was possible to categorized them into therapy, other forms of art, education, exercise, and regular lifestyle. Understanding the characteristics of these comparators helps identifying dance’s effectiveness, understanding the contexts in which can be integrated (therapy, art, education), and how it can be adapted to participants’ needs. This knowledge guides decisions on including dance on public health programs, reveals gaps in current knowledge, and suggests new directions for futures research focus on unexplored aspects.

Assessment tools

Most systematic reviews utilized cognitive assessment such as the MoCA and MMSE, but a wide range of other instruments was also employed, targeting various cognitive domains. All the instruments are widely used in clinical settings and research and are reliable and easy to administer.

Many of them are validated and adapted to use in LMICs and non-English-speaking countries, particularly MoCA, MMSE and TMT. However, the extent and quality of adaptation varies. Validating and adapting these instruments to different cultures would support the inclusion of underrepresented regions and enhance the comparability of study outcomes.

Developing a framework for cognitive assessments specific to dance interventions is critical. This includes identifying instruments that align with defined cognitive domains and are validated across diverse populations. Researchers should classify instruments within this framework to ensure consistency and clarity in evaluating cognitive outcomes.

A transdisciplinary and multisectoral consensus is needed on instruments to evaluate the objective and subjective impact of dance on brain health. These tools should reflect dance’s expected effects, align with validated neuroscience standards and cognitive models, and be equitable, cost-effective, and accessible to include research from LMICs.

Limitations and future research

This umbrella review faces some limitations, including substantial overlap, and considerable heterogeneity in the interventions design, participants characteristics and outcome measures. Overlap among reviews was quantified (supplementary file S9), but no methodological strategies were applied to address or adjust for this overlap during the synthesis process. This may bias effect estimates and should be considered when interpreting the findings. Furthermore, the lack of diverse dance practices across cultures makes it difficult to extrapolate results on brain health in older adults living with MCI or dementia. Additionally, although meta-analyses were conducted when sufficient studies with low heterogeneity were available, it was not possible to explore the influence of geographical region or gender distribution, which may limit the generalizability of this umbrella review findings.

Dance research is a relatively young field, and faces methodological challenges, including small or non-randomized sample sizes, high heterogeneity in participant characteristics, and multimodal intervention designs with different dance genres. Compared to physical activity, which is widely accepted within the medical community, dance studies struggle with recognition and funding, leading to compromised methodological quality. There is a conflict between umbrella review frameworks and the varied nature of dance interventions, leading to non-specific assessment methods and a high risk of bias. As a result, most included systematic reviews are rated low or very low quality.

Future research will benefit from a consensus on high-quality research guidelines, including blinding, clear recruitment reporting, well-defined intervention designs, and detailed participant demographics, lifestyle factors, and dance experience. Transparent reporting, alignment with existing studies, and addressing barriers between research and practice are crucial for advancing the field.

Given dance’s multimodal benefits - combining artistic expression, physical exercise, and strong adherence - expanding access to dance programs for people with dementia is essential. Future research should prioritize global diversity, incorporating participants from LMICs and various socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Culturally adapted assessment tools are necessary for inclusivity. Studies should differentiate the cognitive and physical benefits of different dance genres and compare lifelong versus late-life dance participation. Mixed-methods approaches can provide deeper insights into dance’s multifaceted impact.

While systematizing dance’s effects, it is important to preserve its multimodal nature. A structured framework is needed to analyze dance’s influence on brain health, balancing aerobic intensity, movement dynamics, coordination, and social engagement. It is also recommended to form a global consortium of experts in dance, neuroscience, and public health to standardize methodologies, guide research, and advocate for policy implementation.

Lastly, clear guidelines should be established to comprehensively and representatively demonstrate the impact of dance on brain health in adults with MCI and dementia, offering recommendations for practice.

Conclusion

Dance is a promising but underexplored intervention for improving brain health in older people with MCI and dementia, especially in LMICs. While evidence suggests potential benefits on brain health, significant gaps in research quality, population representation, and intervention standardization must be addressed.

Advancing this field requires a concerted effort to build a global research consortium, establish methodological rigor, and integrate dance into broader frameworks for brain health. Addressing these challenges through more funding and inclusive research is essential to advance the field.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. ANH is an Atlantic Fellow for Equity in Brain Health at the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI) and is supported with funding from GBHI, Alzheimer’s Association, and Alzheimer’s Society < GBHI ALZ UK-24-1068625>. The Authors thank the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI) and UCSF for supporting this work.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualisation: RAP, MK, DS, SPE, IEA, ANH. Data Curation: RAP, MK, DS. Formal Analysis: RAP, MK, DS, SPE, IEA. Funding Acquisition: ANH. Supervision: ANH. Writing – Original Draft Preparation: RAP, MK, DS, SPE, IEA, ANH. Writing – Review & Editing: RAP, MK, DS, SPE, SWL, MPC, PB, PT, EP, IEA, KLP, ANH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable. This manuscript is an umbrella review and does not report the generation or analysis of new datasets. All data supporting this work were obtained from previously published studies, which are cited within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s A. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:1598–1695. 10.1002/alz.13016 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Nichols E, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e105–25. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wimo A, et al. The worldwide costs of dementia in 2019. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023;19:2865–73. 10.1002/alz.12901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthurton L, et al. Dementia is a neglected noncommunicable disease and leading cause of death. Nat Rev Neurol. 2025;21:63–4. 10.1038/s41582-024-01051-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podolski OS, et al. The impact of dance movement interventions on psychological health in older adults without dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 2023;13. 10.3390/brainsci13070981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chan JSY, Wu J, Deng K, Yan JH. The effectiveness of dance interventions on cognition in patients with mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;118:80–8. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Yan Y, Luo Y, Lin R, Li H. Effects of dance therapy on cognitive and mental health in adults aged 55 years and older with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:695. 10.1186/s12877-023-04406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder H, Haussermann P, Fleiner T. Dance-specific activity in people living with dementia: a conceptual framework and systematic review of its effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2023;36:175–84. 10.1177/08919887221130268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaczmarska M. Valuing embodiment: insights from dance practice among people living with dementia. Front Neurol. 2023;14. 10.3389/fneur.2023.1174157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Harrison EA, et al. Perceptions, Opinions, Beliefs, and attitudes about physical activity and exercise in Urban-Community-Residing older adults. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720924137. 10.1177/2150132720924137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisbe M, et al. Comparative cognitive effects of choreographed exercise and multimodal physical therapy in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomized clinical trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;73:769–83. 10.3233/JAD-190552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackney ME, et al. Adapted Tango improves mobility, motor–cognitive function, and gait but not cognition in older adults in independent living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2105–13. 10.1111/jgs.13650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joung HJ, Lee Y. Effect of creative dance on fitness, functional balance, and mobility control in the elderly. Gerontology. 2019;65:537–46. 10.1159/000499402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller P, et al. Evolution of neuroplasticity in response to physical activity in old age: the case for dancing. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Murrock CJ, Graor CH. Effects of dance on depression, physical function, and disability in underserved adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2014;22:380–5. 10.1123/JAPA.2013-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson KK, Wong JS, Prout EC, Brooks D. Dance for the rehabilitation of balance and gait in adults with neurological conditions other than parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Heliyon. 2018;4:e00584. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehfeld K, et al. Dance training is superior to repetitive physical exercise in inducing brain plasticity in the elderly. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0196636. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vankova H, et al. The effect of dance on depressive symptoms in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:582–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verghese J, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2508–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y, et al. Effects of a specially designed aerobic dance routine on mild cognitive impairment. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1691–700. 10.2147/CIA.S163067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet. 2024;404:572–628. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gates M, et al. Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: development of the PRIOR statement. BMJ. 2022;378:e070849. 10.1136/bmj-2022-070849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belbasis L, Bellou V, Ioannidis JP. A. Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Med. 2022;1:e000071. 10.1136/bmjmed-2021-000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi GJ, Kang H. Introduction to umbrella reviews as a useful evidence-based practice. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2023;12:3–11. 10.12997/jla.2023.12.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, et al. Defining brain health: A concept analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;37. 10.1002/gps.5564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kshtriya S, Barnstaple R, Rabinovich DB, DeSouza JF. X. dance and aging: a critical review of findings in neuroscience. Am J Dance Ther. 2015;37:81–112. 10.1007/s10465-015-9196-7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma T, Antonova L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia: Deficits, functional consequences, and future treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:25–40. 10.1016/s0193-953x. (02)00084 – 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen RC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J Intern Med. 2014;275:214–28. 10.1111/joim.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hugo J, Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30:421–42. 10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shea BJ, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1013–20. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guyatt G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewston P, et al. Effects of dance on cognitive function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021;50:1084–92. 10.1093/ageing/afaa270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu VX, et al. The effect of dance interventions on cognition, neuroplasticity, physical function, depression, and quality of life for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;122:104025. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fong ZH, Tan SH, Mahendran R, Kua EH, Chee TT. Arts-based interventions to improve cognition in older persons with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:1605–17. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1786802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Su M, Jiao Y, Ji Y, Zhu S. Effects of dance interventions on cognition, psycho-behavioral symptoms, motor functions, and quality of life in older adult patients with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13. 10.3389/fnagi.2021.706609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Tao D, et al. The effectiveness of dance movement interventions for older adults with mild cognitive impairment, alzheimer’s disease, and dementia: A systematic scoping review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;92:102120. 10.1016/j.arr.2023.102120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S, et al. Effects of mind-body exercise on cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206. 10.1097/nmd.0000000000000912. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Yuan Y, Li X, Liu W. Dance activity interventions targeting cognitive functioning in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.966675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Zhu Y, et al. Effects of aerobic dance on cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020;74:679–90. 10.3233/JAD-190681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vega-Ávila GC, et al. Rhythmic physical activity and global cognition in older adults with and without mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. 10.3390/ijerph191912230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15. 10.1186/s12874-015-0024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Lazarou I, et al. International ballroom dancing against neurodegeneration: a randomized controlled trial in Greek community-dwelling elders with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32:489–99. 10.1177/1533317517725813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doi T, et al. Effects of cognitive leisure activity on cognition in mild cognitive impairment: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:686–91. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi M, Zhu Y, Zhang L, Wu T, Wang J. The effect of aerobic dance intervention on brain spontaneous activity in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a resting-state functional MRI study. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:715–22. 10.3892/etm.2018.7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2021).

- 47.De Marco M, et al. Disparity in the use of alzheimer’s disease treatment in Southern Brazil. Sci Rep. 2023;13:9555. 10.1038/s41598-023-36604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandes C. Corpo Em Movimento O SistemaAnnablume. 2002.

- 49.Miller J. Qual é o corpo Que Dança? Dança e Educação Somática Para Adultos e Crianças. São Paulo: Summus Editorial.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clifford AM, et al. The effect of dance on physical health and cognition in community dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arts Health. 2023;15:200–28. 10.1080/17533015.2022.2093929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hackney ME, Burzynska AZ, Ting LH. The cognitive neuroscience and neurocognitive rehabilitation of dance. BMC Neurosci. 2024;25:58. 10.1186/s12868-024-00906-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fong Yan A, et al. The effectiveness of dance interventions on psychological and cognitive health outcomes compared with other forms of physical activity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024;54:1179–205. 10.1007/s40279-023-01990-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koch SC, et al. Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes. A meta-analysis update. Front Psychol. 2019;10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Maraz A, Király O, Urbán R, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Why do you dance? Development of the dance motivation inventory (DMI). PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122866. 10.1371/journal.pone.0122866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarr B, Launay J, Dunbar RIM. Silent disco: dancing in synchrony leads to elevated pain thresholds and social closeness. Evol Hum Behav. 2016;37:343–9. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chappell K, et al. The aesthetic, artistic and creative contributions of dance for health and wellbeing across the lifecourse: a systematic review. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2021;16:1950891. 10.1080/17482631.2021.1950891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.dos Santos Delabary M, Komeroski IG, Monteiro EP, Costa RR, Haas AN. Effects of dance practice on functional mobility, motor symptoms and quality of life in people with parkinson’s disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:727–35. 10.1007/s40520-017-0836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krotinger A, Loui P. Rhythm and groove as cognitive mechanisms of dance intervention in parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0249933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. This manuscript is an umbrella review and does not report the generation or analysis of new datasets. All data supporting this work were obtained from previously published studies, which are cited within the manuscript.