Abstract

Background

Nitrofurantoin is an antibiotic that demonstrates good efficacy in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially those caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC). However, recent reports about the emergence of nitrofurantoin resistance in UPEC are concerning. This study aimed to investigate the genetic diversity of nitrofurantoin-resistant UPEC isolates and their characteristics.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 235 UPEC isolates collected from Ahvaz, Iran were investigated for resistance to nitrofurantoin. To evaluate the mechanism of this resistance, two groups of chromosomal genes (nfsA, nfsB, and ribE) and plasmid genes (oqxA and oqxB) were investigated by PCR. The nfsA, nfsB, and ribE genes were sequenced and variations of them were analyzed. The phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the isolates were investigated.

Results

In total, six (2.55%) nitrofurantoin-resistant UPEC isolates were identified. The oqxA and oqxB genes and mutations in ribE were not detected. Several deleterious mutations in NfsA (G130D, S39G, H11Y, and ΔW77-F79), and NfsB (N42H, W46R, and H80Y), as well as several neutral mutations in both genes were detected. To our knowledge, the NfsB mutations N42H and H80Y have not been previously reported, suggesting potential novelty. All these isolates were multidrug-resistant (MDR). Although all were non-motile and non-hemolytic, some showed biofilm and cellulose production. Three isolates belonged to the B2 group, while the others belonged to the B1, A, and F groups. Pathogenicity islands (PAIs) IV536, ICFT073, IICFT073, and I536 were variably present. Incompatibility plasmid replicons Frep, FII, FIA, FIB, I1, and A/C were detected across isolates. Virulence-associated genes (VAGs) including iutA, fyuA, papG, traT, fimH, kpsMT II, papC, and afa/draBC were identified.

Conclusion

We concluded that in our studied isolates, deleterious mutation in chromosomal genes nfsA, nfsB, or both is likely drivers of resistance to nitrofurantoin and the changes caused by gene ribE and the presence of plasmid genes oqxAB are at the next levels of importance. Examination of the phenotypic and genetic characteristics of the isolates demonstrates that these mutations may occur in some isolates with high antimicrobial resistance and virulence, highlighting the need for broader studies to assess their epidemiological significance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12941-025-00832-5.

Keywords: Nitrofurantoin resistance, NfsA, NfsB, RibE, OqxA, OqxB, Uropathogenic Escherichia coli, Urinary tract infection

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common bacterial infections affecting humans. They are divided into either complicated or uncomplicated cases and are described with specific reference to the site of inflammation. Cystitis indicates inflammation of the urinary bladder, while pyelonephritis indicates inflammation of the renal pelvis and the kidneys. Escherichia coli is the most common cause of UTIs [1]. A subset of E. coli isolates that can enter and colonize the urinary tract and cause infection is known as uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC). These strains act as opportunistic intracellular pathogens, taking advantage of host susceptibility using a diverse array of virulence factors [2].

Knowledge of the common uropathogens, in addition to local susceptibility patterns, is essential for determining appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy of UTIs [3]. Currently, Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommend nitrofurantoin as a first-line drug for the treatment of these infections [4]. Nitrofurantoin, furazolidone, and nitrofurazone are the members of nitrofurans, a group of antimicrobial compounds, which are characterized by the presence of one or more nitro groups on a nitroaromatic or nitroheterocyclic backbone. These drugs display antimicrobial activity and are used clinically to treat different infections [5]. Nitrofurantoin (C8H6N4O5) is a synthetic antibiotic that is used in prophylaxis and for treating UTIs. This antibiotic is effective against most urinary tract pathogens. Despite its widespread use over decades, there is little resistance to it. In this sense, it is desirable for the treatment of uncomplicated lower UTIs [5].

Nitrofurans need to be reduced to become active. The nitro group combined with furan ring constitutes the active site of the drug, which requires activation by microbial nitroreductase enzymes. Two types of nitroreductase have been identified in E. coli, one of which (type I) is insensitive to oxygen, while the other (type II) is sensitive to oxygen and is inhibited in its presence. NfsA and NfsB, which are encoded by nfsA and nfsB genes, respectively, are nitroreductase I [5, 6]. Recent research highlights that nitrofurantoin resistance in UPEC is mainly due to chromosomal mutations, specifically in nfsA and nfsB genes, as well as in ribE, impacting nitroreductase activity. Furthermore, plasmid-mediated mechanisms like the oqxAB efflux pump genes exacerbate this resistance. In contrast, fosfomycin resistance arises from various mutations affecting drug uptake (e.g., uhpT, uhpA, glpT), the target enzyme (murA), or plasmid-mediated inactivation (e.g., fosA3) [7, 8]. Notably, around half of the studied UPEC strains show complex nitrofurantoin resistance mutations, including amino acid changes in NfsA, NfsB, and RibE, even without efflux genes present.

Intracellular bacterial nitroreductase flavoproteins can also produce the active form of the drug through reduction of the nitro group and resulting in the formation of intermediate metabolites. The resultant compounds are highly active, bind to bacterial ribosomes and obstruct several enzymes needed for the synthesis of DNA, RNA and other metabolic enzymes. Gene of ribE encodes lumazine synthase that is needed for riboflavin biosynthesis. Deletions in this gene are associated with nitrofurantoin resistance in laboratory mutants [9]. In addition to mutations in chromosomal genes, acquisition of plasmid-mediated efflux genes acrAB and oqxAB has been associated with clinically relevant levels of resistance to nitrofurantoin [10].

Recent reports about the emergence of nitrofurantoin resistance in UPEC are concerning. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the frequency of resistance to nitrofurantoin among UPEC isolates, the mechanism of this resistance, and the evaluation of phenotypic and genetic characters of these isolates.

Methods

Ethical

The ethics of the research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz according to Declaration of Helsinki (IR.SCU.REC.1403.031). All archived isolates were fully re-identified prior to analysis and were explicitly covered under ethics approval.

Collection of UPEC isolates and confirmation

This cross-sectional study analyzed UPEC isolates obtained from patients diagnosed with UTIs in Ahvaz, Iran, between 2019 and 2023. The selection criteria included confirmation of UPEC identity through standard microbiological tests, availability of complete metadata (including source of isolation and patient demographics), and temporal and geographical diversity. All isolates were randomly selected, and samples from people who had taken medication or isolates with cross-contamination or poor growth were excluded from the study. In the first step, 140 suspected UPEC isolates were collected from different laboratories and hospitals in Ahvaz city, Iran, from January 2022 to January 2023. Of these, 135 were confirmed as UPEC by conventional biochemical and microbiological tests including MacConkey, Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB), Triple Sugar Iron (TSI), Methyl Red-Voges-Proskauer (MR-VP), Sulfide Indole Motility (SIM), and Gram staining. The remaining 100 isolates were randomly selected from the bacterial archive of the Biology Department at Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz. These archived isolates were originally collected from UTI patients in Ahvaz between 2019 and 2022 and stored at − 80 °C in glycerol stocks. Prior to analysis, archived isolates were revived and re-confirmed using the same identification procedures as prospectively collected samples. To avoid duplication bias, only one isolate per patient was included in the study.

The following formula was applied to estimate the sample size:

Where n is the sample size, z is the confidence level (95%), p is the population proportion was considered 6.8% according to a previous study in Ahvaz [11], and d is the margin of error (0.05). The minimum sample size was 98; however, we evaluated 235 isolates for more accuracy.

Detection of nitrofurantoin-resistant UPEC isolates

The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method was applied uniformly across all isolates to investigate the susceptibility of UPEC isolates to nitrofurantoin. Zone diameters interpreted according to Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)-2023 urine-specific breakpoints (Susceptible ≥ 17 mm, Intermediate = 15–16 mm, Resistant ≤ 14 mm). After identifying nitrofurantoin-resistant or -intermediate UPEC isolates, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the drug was determined by broth microdilution method according to CLSI-2023 guidelines [12]. Broth microdilution assays were performed using cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth. The bacterial inoculum was standardized to 0.5 McFarland turbidity, corresponding to approximately 5 × 10⁵ CFU/mL in each well. Microtiter plates were incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 16–20 h under aerobic conditions. MIC breakpoints for nitrofurantoin were defined as ≥ 128, 64, and ≤ 32 µg/mL for resistant, intermediate, and susceptible UPEC isolates, respectively. Quality control (QC) was ensured using E. coli ATCC 25,922 as the reference strain. MIC values for the QC strain consistently fell within the acceptable CLSI range of 16–64 µg/mL for nitrofurantoin.

The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of the nitrofurantoin-resistant or -intermediate isolates was determined by antibiogram testing. The antibiotic discs used included Ampicillin, Amikacin, Aztreonam, Ceftriaxone, Ciprofloxacin, Cefepime, Cefoxitin, Gentamicin, Imipenem, Kanamycin, Meropenem, Nalidixic Acid, Piperacillin-Tazobactam, Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim, Ampicillin-Sulbactam, Tetracycline, Cefotaxime, and Ceftazidime. To ensure consistency, all antimicrobial susceptibility testing procedures were conducted under standardized laboratory conditions. Sensitivity or resistance was evaluated as recommended by CLSI-2023 [12].

Biofilm assay

Fresh culture of the isolates was prepared and adjusted to 0.5 McFarland. A 96-well polystyrene plate was prepared and 5 µL of each isolate was transferred to 200 µL of LB containing 0.45% glucose in each well. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After removing the supernatant, the cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 5 min and washed with PBS to remove the excess dye. To each well, 200 µL of ethanol 96% was added to solubilize the dye. Optical density was measured using an ELISA reader (BioRad) at 570 nm. The biofilms were categorized into three levels of weak, moderate, and strong, as previously mentioned [13, 14]. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Motility assay

An LB medium with 0.3% agar was prepared and one colony of each isolate was inoculated into the medium. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. The diameter of swimming zones was measured in mm [15].

Hemolysis assay

The isolates were cultured on blood agar containing 5% sheep blood. The clear hemolysis zone was measured after 24 h [16].

Congo red agar assay

Congo red agar medium was prepared by brain–heart infusion broth (BHI) (37 g/L) supplemented with sucrose (5%), and agar (10 g/L). Congo red solution (8 g/L; 100 X) was prepared separately from other medium constituents and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. After cooling the BHI agar medium to 55 °C, the dye was added. The isolates were inoculated on medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The morphology of colonies was recorded as follows: red, dry, and rough (rdar); pink, dry, and rough (pdar); brown, dry, and rough (bdar); smooth and white, dry, and rough (saw). Congo red can bind to cellulose and curli, a specific type of extracellular matrix. Both are consistent with to biofilm expression and an increase in virulence in E. coli. Curli and cellulose producers appear rdar colonies on agar, while curli and cellulose negative isolates are saw morphotype. Curli-positive, cellulose-negative isolates, express bdar colonies, while production of cellulose but not curli indicates pdar phenotype [15, 17].

Identification and investigation of Nitrofurantoin resistance genes using PCR

DNA extraction from nitrofurantoin-intermediate or -resistant UPEC isolated was performed by boiling method. Briefly, 2–3 pure colonies were inoculated into 2 mL of nutrient broth and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. One milliliter of each bacterial culture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The obtained precipitate was dissolved in 200 µL of sterile distilled water and boiled for 10 min. After centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 2 min, the supernatant was used as a source of DNA in the next steps [11].

To detect the mechanism of resistance to nitrofurantoin, two groups of chromosomal genes (nfsA, nfsB, and ribE) and plasmid genes (oqxA and oqxB) were investigated. Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700,721 was used as a positive control for the oqxAB gene. The previously described primers were used to amplify these genes (Table 1). Conditions for PCR reactions were applied as previously described [5, 18, 19]. The nfsA, nfsB, and ribE genes were sequenced by Sanger method and translated to protein sequences using Expasy tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/). These sequences were analyzed for the presence of deletion, insertion, non-sense, and non-synonymous mutations. E. coli train K12 was considered as reference strain (NP_415372.1 for nfsA, NP_415110.1 for nfsB, and NP_414949.1 for ribE). The PROVEAN (Protein Variation Effect Analyzer) software tool (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php) was used to predict the effect of identified changed amino acids on biological function of the protein [20].

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in the study

| Gene | Primer name | Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) | Melting Tm (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oqxA |

oqxA-F oqxA-R |

GCGTCTCGGGATACATTGAT GGCGAGGTTTTGATAGTGGA |

482 | 55 | 18 |

| oqxB |

oqxB-F oqxB-R |

CTGGGCTTCTCGCTGAATAC CAGGTACACCGCAAACACTG |

498 | 57 | 18 |

| ribE |

ribE-F ribE-R |

GCATTTAGTGGGTGCATGATC GGAACTGGTATTCAACATCAGCG |

700 | 58 | 19 |

| nfsA |

nfsA-F nfsA-R |

TTTTCTCGGTGTTTTGCTCA GCTGTATAGCGGCTTCACG |

960 | 56 | 1 |

|

nfsA-F1 nfsA-R1 |

ATTTTCTCGGCCAGAAGTGC AGAATTTCAACCAGGTGACC |

1036 | 56 | 1 | |

|

nfsA-F2 nfsA-R2 |

TCTTGCCCCACAGCTGATG CTTACACGAATAGAGCGTTCC |

893 | 58 | 1 | |

| nsfB |

nfsB-F nfsB-R |

CCCGCTAAATCTTCAACCTG AAAAGAGTGCGTCCAGGCTA |

913 | 57 | 1 |

|

nfsB-F1 nfsB-R1 |

CAACAGCAGCCTATGATGAC CTTCGCGATCTGATCAACG |

923 | 56 | 1 | |

|

nfsB-F2 nfsB-R2 |

TGCAAATCAGGAGAATCTGAG TGGTCTGGCTAAACGCGATC |

846 | 55 | 1 |

Identification of phylogenetic group

The phylogenetic group of the isolates was determined using the revised-Clermont phylotyping method. In the first step, a quadruplex PCR was applied to detect the presence of yjaA, chuA, arpA and TspE4.C2. If the phylogroup was indistinguishable, a complementary PCR was performed. In this way, the isolates were placed in one of the phylogenetic groups of A, B1, B2, C, D, E, F or Clade I. Primers and PCR conditions were applied according to study of Clermont et al. [21].

Plasmid replicon typing, virulence-associated genes (VAGs) and pathogenicity Islands (PAIs)

PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) assay was used for detection of plasmid replicons. Three panels of multiplex-PCR were used to detect 18 replicon types. The primers and PCR reaction conditions were applied as designed by Johnson et al. [22]. Briefly, the first panel included B/O, FIC, A/C, P, and T replicon types yielding 159, 262, 465, 534, and 750 bp fragments respectively. The second panel was done to detect K/B, W, FIIA, FIA, FIB, and Y replicon types with sizes of 160, 242, 270, 462, 702, and 765 bp. I1, Frep, X, HI1, N, HI2, and L/M replicon types were amplified in the third panel, yielding 139, 270, 376, 471, 559, 644, and 785 bp.

A group of 30 VAGs was investigated using five separate multiplex-PCR assays, which were designed using Johnson and Stell. These genes included traT, cvaC, papAH, papEF, papC, papG, papG allele I, I’a, II, and III, kpsMT II, kpsMT III, kpsMT K1, kpsMT K5, fimH, iutA, hlyA, fyuA, ibeA, sfaS, sfa/focDE, afa/draBC, bmaE, focG, cnf1, cdtB, nfaE, gafD, rfc, and PAI. Primers and PCR conditions were applied as previously described by Johnson and Stell [23].

PAI markers were detected using two multiplex-PCR assays as recommended by Sabate et al. PAI III536, PAI IV536 and PAI IICFT073 were investigated in the first multiplex, yielding 200, 287, and 421 bp fragments, respectively. In the second multiplex, five PAI markers including PAI IIJ96, PAI I536, PAI II536, PAI ICFT073, and PAI IJ96 were detected yielding 2300, 1802, 1042, 930 and 461 bp fragments, respectively [24].

Statistical analysis

The proportion of resistant isolates was calculated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the Clopper-Pearson exact method, appropriate for small sample sizes and binary outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (V: 10.1.1), with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

Nitrofurantoin-resistant UPEC isolates

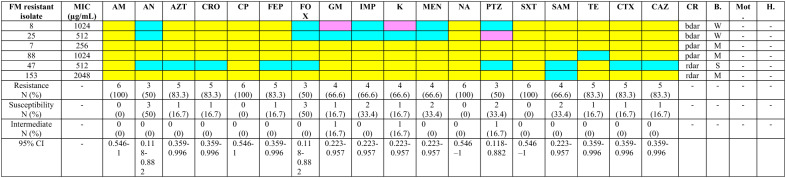

In total, 235 isolates were confirmed as UPEC. Out of these, 6 (2.55%; 95% CI: 0.94% to 5.45%) were identified as nitrofurantoin-resistant. None of them was nitrofurantoin-intermediate. The MIC of the drug for each isolate is shown in Table 2. These isolates were considered for the next stages of the study. The antimicrobial resistance pattern of these isolates is shown in Table 2. All were multidrug-resistant (MDR) (resistant to three or more categories of antimicrobial agents) (95% CI: 54.1%–100.0%). Resistance against ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was found in all six isolates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phenotypic characterization of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates

Yellow color: Resistant; Purple color: Intermediate; Blue color: Susceptible; FM Nitrofurantoin, MIC Minimum Inhibition Concentration, AM Ampicillin, AN Amikacin, AZT Aztreonam, CRO Ceftriaxone, CP Ciprofloxacin; FEP Cefepime, FOX Cefoxitin, GM Gentamicin, IMP Imipenem, K Kanamycin, MEN Meropenem, NA Nalidixic Acid, PTZ Piperacillin-Tazobactam, SXT Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim, SAM Ampicillin-Sulbactam, TE Tetracycline, CTX Cefotaxime, CAZ Ceftazidime, N Number, CI Confidence Interval, CR Congo Red, bdar brown, dry, and rough, pdar pink, dry, and rough, rdar red, dry, and rough, B Biofilm, W Weak, M Moderate, S Strong, Mot Motility, H Hemolysis, “ – ”: Negative

Phenotypic characterization of the nitrofurantoin-resistant UPEC isolates

All isolates were negative for motility and hemolysis. Congo red assay showed that two isolates (33.3%; 95% CI: 6.0%–75.9%) were rdar phenotype, consistent with production of both curli fimbria and cellulose. Two isolates (33.3%; 95% CI: 6.0%–75.9%) showed the pdar morphotype, consistent with cellulose production only, and two isolates (33.3%; 95% CI: 6.0%–75.9%) displayed the bdar morphotype, consistent with curli fimbriae production only. While Congo red morphotypes (rdar, bdar, pdar) are commonly used as phenotypic proxies for curli and cellulose production, it is important to note that phenotype does not necessarily equate to genotype. Without confirmatory molecular data (e.g., sequencing or expression analysis of csgA for curli and bcsA for cellulose), these morphotypes should be interpreted with caution. The biofilm assay showed that three (50.0%; 95% CI: 11.8%–88.2%), two (33.3%; 95% CI: 6.0%–75.9%), and one (16.7%; 95% CI: 0.4%–64.1%) isolates produce strong, moderate, and weak biofilms, respectively (Table 2).

Detection of Nitrofurantoin resistance genes and protein variation effect

PCR results for plasmid genes oqxA and oqxB showed that none of the isolates contain these genes; therefore, their resistance probably does not have a plasmid origin. PCR test was performed to multiply the chromosomal genes nfsA, nfsB and ribE, then these genes were sequenced. No change was observed in the amino acid sequences of the protein obtained from ribE for all isolates; therefore, the mechanism of nitrofurantoin resistance in the investigated isolates is not related to the mutation in this gene.

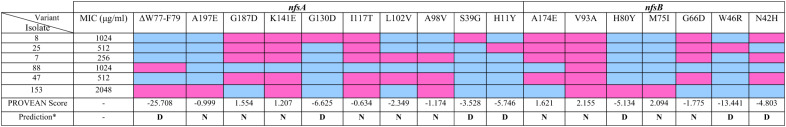

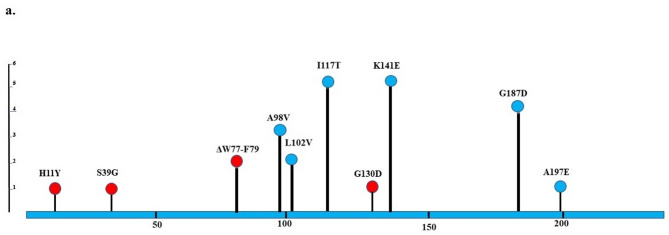

The nfsA sequencing revealed the changes in amino acid sequences of NfsA protein as follows: H11Y (one isolate), S39G (one isolate), A98V (3 isolates), L102V (2 isolates), I117T (5 isolates), G130D (one isolate), K141E (5 isolates), G187D (4 isolates), and A197E (one isolate) (Table 3; Fig. 1). A deletion mutation (ΔW77-F79) was found in two isolates. PROVEAN prediction revealed several deleterious mutations, including G130D, S39G, H11Y, and ΔW77-F79 (Supplementary Table 1). These mutations probably have huge effects on function of NfsA protein. However, all mutations were neutral in two isolates (Supplementary Tables 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Mutations in NfsA and NfsB genes of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates

*Cutoff= -2.5; N Neutral, D Deleterious, Blue: Absent Mutation, Pink: Present Mutation; MIC Minimum Inhibition Concentration

Fig. 1.

Lollipop plots show the NfsA/NfsB variants of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Any position with a mutation is shown as a circle. Red and blue circles indicate deleterious and neutral mutations, respectively. The length of the line indicates the number of mutations detected at that codon. The blue bar represents the entire protein. a NfsA; b NfsB

Sequencing of nfsB gene showed amino acid changes in the NfsB protein as follows: N42H, W46R, G66D, M75I, H80Y, V93A, and A174E. Also, V39A was found in all six isolates; however, the changes of H80Y, M75I, and W46R were detected in one isolate (Table 3; Fig. 1). Notably, NfsB mutations N42H and H80Y have not been previously reported to our knowledge, suggesting potential novel contributors to nitrofurantoin resistance. All isolates except 7B harbored deleterious mutations, which included N42H, W46R, and H80Y (Supplementary Tables 1 and Fig. 1).

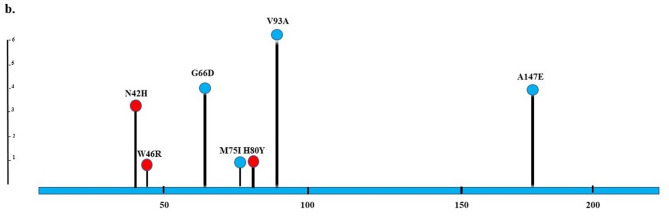

Phylogenetic groups, PAIs, and virulome

Phylogenetic analysis showed that three isolates belonged to the B2 group, while the others were B1, A, and F groups (Fig. 2). The content of PAIs is shown in Fig. 2. PAIs IV536, ICFT073, IICFT073, and I536 were found in five, four, one, and one isolates, respectively; however, other PAIs were not found. Isolate 25B harbored four PAIs, while isolate 47 had no PAI. Among 30 investigated VAGs, papA, iutA, fimH, fyuA, papC, traT, papG allele II, papG allele II and III, afa/draBC, and kpsMT II were found in two, four, two, three, two, three, two, one, one, and one isolates, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Heatmap generated according different genetic characters of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Characteristics that were negative in all isolates are not shown

Plasmid replicon typing profile

PBRT showed the presence of Frep, FII, FIA, FIB, I1, and A/C replicons among five, five, four, four, three, and two isolates, respectively. Isolate 47 did not carry any plasmids (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Nitrofurantoin is a chemotherapeutic and a synthetic antimicrobial compound of the nitrofuran family that was introduced into clinical practice in 1953 and is widely utilized in prophylaxis and treatment of UTIs. Nitrofurantoin is a broad-spectrum bactericidal antibiotic that usually stays active against drug-resistant uropathogens and is known as the first-line therapy for uncomplicated lower UTIs. An increase in nitrofurantoin prescription has not caused an apparent change in nitrofurantoin resistance, which remains consistently below 10% [25, 26].

Varying levels of nitrofurantoin resistance have been reported in studies from different countries. In our study, we found a resistance rate of 2.55% among UPEC isolates. Other studies in Iran showed frequencies of 4.6% (Ahvaz) [11], 6% (Isfahan) [27], and 4.8% (Shiraz) [28] for nitrofurantoin resistance. Asadi Karam et al. reported a nitrofurantoin resistance rate of approximately 4.2% among UPEC isolates in Tehran [29], while Fakhri-Demeshghieh et al. found rates ranging from 6% to 8% in pediatric populations across Iran [30]. Higher rates of resistance ranging from 12.6% to 23.3% were reported in some countries such as India, Brazil, China, and Kenya [31, 32], while lower resistance rates were reported in America (2.1) [33] and Europe (1%) [34]. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance data from 2023, nitrofurantoin resistance among MDR E. coli isolates in the United States reached 10.7%, based on over 15,000 clinical samples [35]. In a recent meta-analysis by Larkin et al., the worldwide resistance rate to nitrofurantoin among UPEC isolates was reported as 6.9%, while the pooled prevalence in Iran was slightly higher at 8.2% [36].

We investigated the possible mechanisms of nitrofurantoin resistance, focusing on plasmid versus chromosomal origins. Sequencing of nfsA genes revealed several neutral and deleterious mutations. We found nine amino acid substitutions and one amino acid deletion; however, nonsense and insertion mutations were not observed. Most mutations in NfsA were I117T (5 isolates), K141E (5 isolates), and G187D (4 isolates), which were predicted to be neutral by PROVEAN. These mutations have been reported previously [5, 10, 37–39], and in some studies, they were found in susceptible nitrofurantoin isolates [37–39]. Additional neutral substitutions included A98V (three isolates), L102V (two isolates), and A197E (one isolate), which, to our knowledge, have not been previously reported.

Three substitution amino acid mutations, including H11Y, S39G, and G130D were identified and were recognized by PROVEAN as deleterious mutations. H11Y was previously reported in some studies and was found only in nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates [38–41], while S39G and G130D, to our knowledge, have not been reported before. Two isolates showed ΔW77-F79 mutation, which was reported by Sekyere [10], while in the Sandegren and colleagues’ study W77*stop was observed [5]. This mutation was detected as deleterious by PROVEAN. Thus, four out of the six isolates each had at least one deleterious mutation in NfsA.

Sequencing of the nfsB gene revealed seven substitution amino acid mutations, including G66D (4 isolates), A174E (4 isolates), M75I (1 isolate), V93A (5 isolates), H80Y (1 isolate), W46R (1 isolate), and N42H (3 isolates). The first four were identified by PROVEAN as neutral mutations and were reported in other studies in nitrofurantoin-susceptible or -resistant isolates [5, 40, 42]. Dulyayangkul et al. believe that these mutations are not harmful enough to cause resistance [39]. Three other mutations were predicted as deleterious by PROVEAN. Dulyayangkul et al. showed that W46R led to the enzyme activity dropping to zero [39]. To our knowledge, two other predicted deleterious mutations (H80Y and N42H) have not been previously reported. One of the limitations of the present study is that the effect of these mutations on nitroreductase function and bacterial fitness was not investigated. However, considering the PROVEAN prediction, five out of the six nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates have deleterious mutations in the nfsA, nfsB, or both genes.

No change was observed in the amino acid sequence of protein derived from the chromosomal gene ribE in any of the nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates. It was reported in some other studies [19]. Similarly, plasmid-mediated genes oqxA and oqxB were also not found. Although, Ho et al. reported the high prevalence of efflux gene oqxAB among nitrofurantoin-intermediate or -resistant and believed that OqxAB is an important mechanism for nitrofurantoin resistance in E. coli [19]; however, in our study and some others, the resistance was not plasmid-mediated in origin [38, 39, 41].

Investigation of some phenotypic and genetic characteristics of nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates showed that all of these isolates were MDR and resistance to ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and nalidixic acid was observed in all of them. Although none were hemolytic and motile, some were biofilm producer, carried several VAGs, and PAIs. Except for one isolate, the others carried at least the F plasmid. These isolates belonged to different phylogenetic groups, which may contribute to their observed phenotypic and genetic diversity. The MDR profiles and presence of virulence factors in nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates raise concerns about their pathogenic potential. Although pathogenicity was not directly assessed, the clinical origin of these isolates from UTI patients underscores their relevance. Sandegren et al. reported that resistance to nitrofurantoin leads to a decrease in bacterial fitness and growth rate; nevertheless, it remains unclear whether this resistance also affects pathogenicity [5].

The presence of neutral mutations in both nfsA and nfsB genes, some of which were previously reported in susceptible isolates, indicates that not all mutations contribute directly to resistance. High-level resistance to nitrofurantoin requires the inactivation of both nfsA and nfsB genes. These two genes are far apart (287 kb distance), so simultaneous inactivation of both is unlikely and occurs in several steps [43]. Of the six isolates, four had deleterious mutations in both genes, but one isolate had a deleterious mutation only in the nfsB gene, and the mutations in one isolate were all neutral. Therefore, we cannot exactly demonstrate what caused resistance to nitrofurantoin in two isolates and suggests that additional mechanisms may be involved. Previous studies have shown that even functional alleles of nfsA and nfsB may be downregulated or rendered inactive through other genetic changes [39]. For example, Dulyayangkul et al. reported that six nitrofurantoin-resistant E. coli isolates had non-functional nfsA, but functional nfsB alleles. Furthermore, three carried both nfsA and nfsB functional alleles. They assayed enzyme activity of NfsA and NfsB in these isolates and found that the nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates with functional NfsA all had no detectable enzyme activity of NfsA. They concluded that these isolates, with functionally wild-type NfsB or NfsA/B, had genetic changes that led to downregulation of NfsA/B enzyme activity in other ways [39]. Similarly, Sorlozano-Puerto and colleagues, six nitrofurantoin-resistant isolates harbored NfsA protein compatible with wild type, while two had deleterious substitutions in NfsB. In their study, the exact cause of resistance in these isolates was not identified; however, the authors proposed that specific modifications in the NfsB protein (independent of prior nfsA mutations) could lead to functional alterations in nitroreductase activity [9, 40].

This study has several limitations. First, its focus on a specific geographic region and time frame may not capture broader epidemiological trends; nonetheless, the findings offer valuable insight into local resistance patterns and can inform regional antimicrobial stewardship efforts. Second, the lack of functional validation such as complementation, enzyme assays, or expression profiling limits the ability to directly confirm the role of nfsA/nfsB mutations in nitrofurantoin resistance. Third, promoter and regulatory regions of ribE were not examined, which may influence gene expression and contribute to resistance. Finally, the study did not include expression analysis of intrinsic efflux pumps like AcrAB-TolC or their global regulators (MarA, SoxS, Rob); although oqxAB was not detected, the potential role of native efflux mechanisms remains unaddressed.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that deleterious mutations in the chromosomal genes nfsA, nfsB, or both are likely drivers of resistance to nitrofurantoin. Alterations in ribE and the presence of plasmid genes oqxAB were not observed in our isolates, suggesting that these factors may play a limited or secondary role in nitrofurantoin resistance, at least in the studied population. Given the small number of resistant isolates and lack of functional assays, further validation (complementation and enzyme activity) is warranted.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1. Fig. 1. Location of amino acid substitutions in the NfsA and NfsB proteins of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Protein sequences from resistant isolates were aligned using BioEdit (V.7.2). Conserved residues are indicated by dots, and mutations are highlighted at specific positions. NP_415372.1 and NP_415110.1 are sequences of reference strains and the others are isolates studied. a. NfsA ; b. NfsB

Acknowledgements

The authors are very much thankful to Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz for the facilities to accomplish the present research project within time.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the experiment. SER and MRA designed and supervised the research study. ShN carried out the experiments Data analysis was performed by SER. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

Genome sequences data have been submitted to the NCBI database under the accession numbers of PX257814, PX257815, PX257816, PX257817, PX257818, PX257819, PX257820, PX257821, PX257822, PX257823, PX278701, PX278702, PX278703, PX278704, PX278705, PX278706, PX278707, and PX278708.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz (IR.SCU.REC.1403.031). Before collecting information, participants or parents (for children cases) were asked to read, accept and sign an informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Seyedeh Elham Rezatofighi, Email: elhamrezatofighi@gmail.com, Email: e.tofighi@scu.ac.ir.

Mohammad Roayaei Ardakani, Email: m.roayaei@scu.ac.ir, Email: roayaei_m@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Subashchandrabose S, Mobley HLT. Virulence and fitness determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3(4). 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0015-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Agarwal J, Srivastava S, Singh M. Pathogenomics of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2012;30(2):141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader MS, Loeb M, Leto D, Brooks AA. Treatment of urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance and new antimicrobial agents. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(3):234–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squadrito FJ, del Portal D. Nitrofurantoin. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL). StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed]

- 5.Sandegren L, Lindqvist A, Kahlmeter G, et al. Nitrofurantoin resistance mechanism and fitness cost in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(3):495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiteway J, Koziarz P, Veall J, et al. Oxygen-Insensitive nitroreductases: analysis of the roles of NfsA and NfsB in development of resistance to 5-Nitrofuran derivatives in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(21):5529–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jomehzadeh N, Saki M, Ahmadi K, et al. The prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes among Escherichia coli strains isolated from urinary tract infections in Southwest Iran. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:3757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jomehzadeh N, Ahmadi Kh, Rahmani Z. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases among uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates in Southwestern Iran. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2021;12(6):390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vervoort J, Xavier BB, Stewardson A, et al. An in vitro deletion in RibE encoding lumazine synthase contributes to Nitrofurantoin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekyere JO. Genomic insights into Nitrofurantoin resistance mechanisms and epidemiology in clinical Enterobacteriaceae. Future Sci OA. 2018;4(5):FSO293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zangane Matin F, Rezatofighi SE, Roayaei Ardakani M, et al. Virulence characterization and clonal analysis of uropathogenic Escherichia coli metallo-beta-lactamase-producing isolates. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2021;20:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33rd ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2023.

- 13.Toval F, Köhler CD, Vogel U, et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from hospital inpatients or outpatients with urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:407–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stepanović S, Vuković D, Hola V, et al. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by Staphylococci. APMIS. 2007;115:891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiebel J, Böhm A, Nitschke J, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics associated with biofilm formation by human clinical Escherichia coli isolates of different pathotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e01660–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nascimento JAS, Santos FF, Valiatti TB, et al. Frequency and diversity of hybrid Escherichia coli strains isolated from urinary tract infections. Microorganisms. 2021;9:693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldiris–Avila R, Montes–Robledo A, Buelvas–Montes Y. Phylogenetic Classification, Biofilm–Forming Capacity, virulence Factors, and antimicrobial resistance in uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC). Curr Microbiol. 2020;77:3361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez F, Rudin SD, Marshall SH, et al. OqxAB, a quinolone and olaquindox efflux pump, is widely distributed among multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of human origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4602–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho PL, Ng KY, Lo WU, et al. Plasmid-mediated OqxAB is an important mechanism for Nitrofurantoin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:537–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2745–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clermont O, Christenson JK, Denamur E, et al. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson TJ, Wannemuehler YM, Johnson SJ, et al. Plasmid replicon typing of commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. J Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):1976–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with Urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:261–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabaté M, Moreno E, Pérez T, et al. Pathogenicity Island markers in commensal and uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(9):880–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munoz-Davila MJ. Role of old antibiotics in the era of antibiotic resistance. Highlighted Nitrofurantoin for the treatment of lower urinary tract infections. Antibiot (Basel). 2014;3(1):39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahdizade Ari M, Dashtbin S, Ghasemi F, et al. Nitrofurantoin: properties and potential in treatment of urinary tract infection: a narrative review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1148603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirzarazi M, Rezatofighi SE, Pourmahdi M. M, Antibiotic resistance of isolated gram negative bacteria from urinary tract infections (UTIs) in Isfahan. Jundishapur J Microbiol 20136(8):1E.

- 28.Malekzadegan Y, Khashei R, Sedigh Ebrahim-Saraie H, et al. Distribution of virulence genes and their association with antimicrobial resistance among uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from Iranian patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asadi Karam MR, Habibi M, Bouzari S. Relationships between virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance among Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infections and commensal isolates in Tehran, Iran. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2018;9(5):217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fakhri-Demeshghieh A, Shokri A, Bokaie S. Antibiotic resistance of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) among Iranian pediatrics: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2024;53(3):508–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohapatra S, Panigrahy R, Tak V, et al. Prevalence and resistance pattern of uropathogens from community settings of different regions: an experience from India. Access Microbiol. 2022;4(2):000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khamari B, Bulagonda EP. Unlocking nitrofurantoin: Understanding molecular mechanisms of action and resistance in enterobacterales. Med Princ Pract. 2025;34:121–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez GV, Baird AMG, Karlowsky JA, et al. Nitrofurantoin retains antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant urinary Escherichia coli from US outpatients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(12):3259–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ny S, Edquist P, Dumpis U, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli isolates from outpatient urinary tract infections in women in six European countries including Russia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance & patient safety portal: multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli profile. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2023. https://arpsp.cdc.gov/profile/antibiotic-resistance/mdr-ecoli. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larkin C, Valappil SP, Palanisamy N. Global prevalence of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2025:dkaf305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Khamari B, Adak S, Chanakya PP, et al. Prediction of Nitrofurantoin resistance among Enterobacteriaceae and mutational landscape of in vitro selected resistant Escherichia coli. Microbiol Res. 2022;173:103889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mottaghizadeha F, Mohajjel Shojaa H, Haeilia M, et al. Molecular epidemiology and Nitrofurantoin resistance determinants of Nitrofurantoin-non-susceptible Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infections. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:335–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dulyayangkul P, Sealey JE, Lee WWY, et al. Improving Nitrofurantoin resistance prediction in Escherichia coli from whole-genome sequence by integrating NfsA/B enzyme assays. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2024;68(7):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorlozano-Puerto A, Lopez-Machado I, Albertuz-Crespo M, et al. Characterization of fosfomycin and Nitrofurantoin resistance mechanisms in Escherichia coli isolated in clinical urine samples. Antibiotics. 2020;9:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WanY ME, Leung RCY, et al. Alterations in chromosomal genes nfsA, nfsB, and RibE are associated with Nitrofurantoin resistance in Escherichia coli from the united Kingdom. Microb Genom. 2021;7:000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang F, et al. Unraveling the mechanisms of Nitrofurantoin resistance and epidemiological characteristics among Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52(2):226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vallée M, Harding C, Hall J, et al. Exploring the in situ evolution of Nitrofurantoin resistance in clinically derived uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023;78:373–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1. Fig. 1. Location of amino acid substitutions in the NfsA and NfsB proteins of nitrofurantoin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Protein sequences from resistant isolates were aligned using BioEdit (V.7.2). Conserved residues are indicated by dots, and mutations are highlighted at specific positions. NP_415372.1 and NP_415110.1 are sequences of reference strains and the others are isolates studied. a. NfsA ; b. NfsB

Data Availability Statement

Genome sequences data have been submitted to the NCBI database under the accession numbers of PX257814, PX257815, PX257816, PX257817, PX257818, PX257819, PX257820, PX257821, PX257822, PX257823, PX278701, PX278702, PX278703, PX278704, PX278705, PX278706, PX278707, and PX278708.