Abstract

Aspergillic acid, a hydroxamate-containing pyrazinone derived from leucine and isoleucine, is a hallmark metabolite of Aspergillus flavus, which also produces the potent carcinogen aflatoxin. Its biosynthesis is governed by the recently characterized asa gene cluster. While A. flavus consistently produces aspergillic acid, its domesticated relative Aspergillus oryzae has long been considered a non-producer. Here, we compared the asa cluster activity and metabolite output in A. flavus NRRL 3357 and two A. oryzae strains (RIB40 and NRRL 3483) under amino acid–rich conditions. In A. flavus, asa genes were strongly induced in casein peptone medium, resulting in robust production of aspergillic acid, deoxyaspergillic acid, and iron-chelating ferriaspergillin. A. oryzae RIB40 showed no transcriptional activation or metabolite production. By contrast, A. oryzae NRRL 3483 exhibited clear asa cluster induction and detectable accumulation of deoxyaspergillic acid and trace aspergillic acid sufficient to form ferriaspergillin. Notably, the disproportionate buildup of deoxyaspergillic acid revealed a bottleneck in downstream tailoring steps. These results demonstrate that A. oryzae retains strain-specific, conditionally inducible aspergillic acid biosynthesis, highlighting evolutionary attenuation of secondary metabolism in domesticated fungi. This work establishes a framework for dissecting regulatory and enzymatic constraints in the asa pathway, highlighting the potential of hidden biosynthetic clusters for natural product discovery and biotechnological applications.

Keywords: Aspergillic acid, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus flavus, Asa gene cluster

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Biotechnology, Microbiology

Introduction

Fungal secondary metabolism generates structurally diverse compounds that mediate ecological interactions, drive pathogenicity, and serve as a rich reservoir of bioactive natural products1. These metabolites are typically encoded within biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that house modular enzymes, cluster-specific transcription factors, and auxiliary proteins. In many fungi, BGCs remain transcriptionally silent under standard laboratory conditions, requiring specific environmental or nutritional cues for activation2. One such metabolite is aspergillic acid, a hydroxamate-containing pyrazinone identified initially as an antibiotic from Aspergillus flavus. Its structure (C12H20N2O2, 224.3 g/mol) arises from the condensation of leucine and isoleucine, followed by oxidative tailoring reactions3. A. flavus consistently produces aspergillic acid, whereas its domesticated, food-fermenting relative Aspergillus oryzae has long been regarded as a non-producer, mirroring its loss of aflatoxin biosynthetic capacity. Consequently, aspergillic acid production has been viewed as a key trait distinguishing toxigenic A. flavus from food-safe A. oryzae. Yet emerging evidence suggests that certain A. oryzae strains may retain cryptic potential for aspergillic acid biosynthesis under specific culture conditions4,5.

Aspergillic acid biosynthesis is governed by the asa gene cluster, which includes asaA (ankyrin-repeat protein), asaB (GA4 desaturase family protein), asaC (NRPS-like enzyme), asaD (cytochrome P450), asaR (C6-type transcription factor), and asaE (putative transporter)6,7. Functional analyses in A. flavus have established asaC as essential for metabolite production, with asaR required for cluster-wide transcriptional activation. Additionally, asaA modulates the expression of asaC and asaD, while global regulators such as VeA and LaeA act as positive regulators and NsdC functions as a repressor6. Chemically, the pathway proceeds from deoxyaspergillic acid (C12H20N2O, 208.3 g/mol), formed by AsaC, to aspergillic acid via hydroxylation by AsaD, and further to hydroxyaspergillic acid (C12H20N2O3, 240.3 g/mol) through AsaB. A defining property of aspergillic acid is its ability to chelate ferric iron (Fe3+), yielding the characteristic red ferriaspergillin complex (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and proposed biosynthetic pathway of aspergillic acid in Aspergillus flavus. Schematic overview comparing aspergillic acid biosynthesis in A. flavus (producer) and A. oryzae (non-producer or weak producer). Cultures were grown in liquid media under two conditions: glucose minimal medium (GMM) and casein peptone (CP). Aspergillic acid is synthesized from the amino acid precursors L-leucine and L-isoleucine, which condense to form deoxyaspergillic acid via asaC (NRPS-like enzyme). Subsequent hydroxylation by asaD (cytochrome P450) yields aspergillic acid, which is further modified by asaB (desaturase family enzyme) to produce hydroxyaspergillic acid. A defining feature of aspergillic acid is its ability to chelate ferric iron (Fe3+), forming the characteristic red ferriaspergillin complex6. Chemical structures of intermediates and products are shown (ChemDraw).

In this study, we compared aspergillic acid biosynthesis across A. flavus NRRL 3357 and two A. oryzae strains, RIB40 and NRRL 3483. Using qRT-PCR, we tracked expression dynamics of key asa genes (asaC, asaD, asaB, asaR). As expected, A. flavus exhibited strong but transient asa induction in casein peptone medium, leading to abundant metabolite production. A. oryzae RIB40 remained transcriptionally silent, confirming its inability to produce aspergillic acid. Strikingly, A. oryzae NRRL 3483 displayed partial asa activation under the same conditions, accompanied by detectable metabolite accumulation. These results underscore the evolutionary attenuation of secondary metabolism in domesticated fungi while revealing that some A. oryzae strains retain cryptic but conditionally inducible biosynthetic capacity.

Results and discussion

Comparison of the aspergillic acid biosynthetic gene cluster in A. flavus and A. oryzae

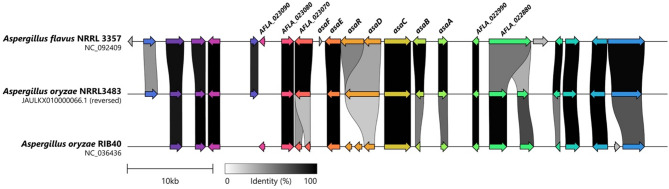

To investigate differences in aspergillic acid biosynthesis at the genomic level, the asa gene cluster was identified in A. flavus NRRL3357, A. oryzae RIB40, and A. oryzae NRRL3483 using antiSMASH, and the clusters were visualized and compared with clinker (Fig. 2). Core cluster genes, including asaA, asaB, asaC, and asaE were conserved across all strains. Notably, A. oryzae NRRL3483 shared higher sequence identity for asaA and asaB with A. flavus NRRL3357 than with A. oryzae RIB40, highlighting the importance of considering intraspecies, strain-level variation when evaluating secondary metabolite biosynthetic potential.

Fig. 2.

Comparative organization of the aspergillic acid biosynthetic gene cluster in Aspergillus flavus NRRL3357, A. oryzae NRRL3483, and A. oryzae RIB40. Biosynthetic gene clusters were predicted using antiSMASH and visualized with clinker, aligned around asaC (putative NRPS-like enzyme). Gene identities were assigned based on BLASTn matches to sequences reported by Lebar et al.6. Conserved core genes (asaA, asaB, asaC, asaE) and structural variations in asaR and asaD highlight strain-specific differences in cluster architecture between A. flavus and A. oryzae.

Expanding upon the 12 genes identified by Lebar, et al.6, the antiSMASH-predicted clusters encompassed 19–23 genes, many of which were highly conserved among the three strains. However, notable discrepancies were observed in asaR and asaD. Relative to the A. flavus NRRL3357 reference, asaR and asaD appeared as a single fused gene in A. oryzae NRRL3483, whereas in A. oryzae RIB40 they were fragmented into three distinct genes. BLAST analysis of the genomic region spanning asaR and asaD did not provide strong evidence supporting a true gene fusion, suggesting that the observed differences are more likely due to annotation artifacts. This structural variability accounts for the lower sequence identity of asaR and asaD across the strains, although their functions have been well characterized in previous studies supported by transcriptional evidence. In addition, asaF (uncharacterized protein) was absent in both A. oryzae strains, and several other genes were either split or missing. Such discrepancies likely reflect incomplete annotation of the asa cluster in A. oryzae, and further transcriptomic analyses will be required to refine the gene models and confirm their roles in aspergillic acid biosynthesis.

Expression dynamics of the asa gene cluster in both A. flavus and A. oryzae

To assess whether A. oryzae retains the ability to activate aspergillic acid biosynthesis, we compared asa cluster expression across A. flavus NRRL 3357 and two A. oryzae strains, RIB40 and NRRL 3483. Cultures were grown in glucose minimal medium (GMM) as a baseline control and in casein peptone (CP), a nutrient-rich medium enriched in peptides and free amino acids such as leucine and isoleucine, the known precursors of aspergillic acid. qRT-PCR analysis revealed a clear, time-dependent activation of the asa biosynthetic genes in both A. flavus and A. oryzae NRRL 3483 when cultured in CP medium, while A. oryzae RIB strain exhibited minimal or no induction (Fig. 3). At day 2, asaC and asaD from A. flavus were already highly induced (~ 3800- and ~ 2000-fold, respectively) (Fig. 3a), with transcription peaking at day 3, where asaD exceeded 11,000-fold induction accompanied by high expression levels of asaB, asaC, and asaR (Fig. 3b). By days 4 and 5, transcript levels declined to moderate or near-baseline values, indicating a shut-down phase following peak secondary metabolite production (Fig. 3c–d). Closer examination of transcriptional patterns revealed a sequential activation of the asa cluster in both A. flavus NRRL 3357 and A. oryzae NRRL 3483. AsaC was induced earliest, consistent with its role as the NRPS-like enzyme catalyzing the condensation of leucine and isoleucine. asaB expression followed, indicating early engagement of hydroxylation steps, and asaD peaked later (day 3), coinciding with maximal conversion of deoxyaspergillic acid to aspergillic acid. This cascade suggests that precursor supply is established first through asaC, followed by tailoring enzymes that complete pathway biosynthesis.

Fig. 3.

Expression dynamics of aspergillic acid biosynthetic genes in Aspergillus flavus and A. oryzae under casein peptone (CP) medium relative to glucose minimal medium (GMM). Relative transcript levels of asaB, asaC, asaD, and asaR were quantified by qRT-PCR in A. flavus NRRL3357 and A. oryzae strains RIB40 and NRRL3483 after (a) 2, (b) 3, (c) 4, and (d) 5 days of culture. Expression ratios are presented as fold change in CP medium compared to GMM (baseline = 1) and presented in log scale. CP medium, enriched in peptides and amino acids such as leucine and isoleucine, was used to assess induction of the asa cluster. Statistical significance was calculated using t-tests (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Interestingly, A. oryzae NRRL 3483 also showed measurable induction of asa genes in CP medium, with a transcriptional profile qualitatively resembling that of A. flavus, albeit at much lower overall levels. By contrast, A. oryzae RIB40 remained transcriptionally silent under both control and CP media, with no significant expression changes across all time points. This mirrors the situation observed in the aflatoxin cluster: while A. oryzae retains the full aflatoxin biosynthetic gene cluster but carries disabling mutations (such as a non-functional aflR regulator) that prevent toxin biosynthesis9. Similarly, the failure of RIB40 to induce asaC suggests a regulatory block at the earliest stage, potentially linked to differences in asaR activity or global regulators such as VeA and LaeA. Together, these results demonstrate that activation of the asa cluster in A. oryzae is strain-dependent and that CP medium not only supplies precursor amino acids but also creates a metabolic context favorable for secondary metabolism. Moreover, they highlight that both the strength and the timing of cluster gene induction are critical for determining final metabolite output. Future research exploring forced expression of asaR and comparative promoter analysis of asaC between these strains will be essential to clarify whether the observed differences are due to asaR activity or promoter-level regulation.

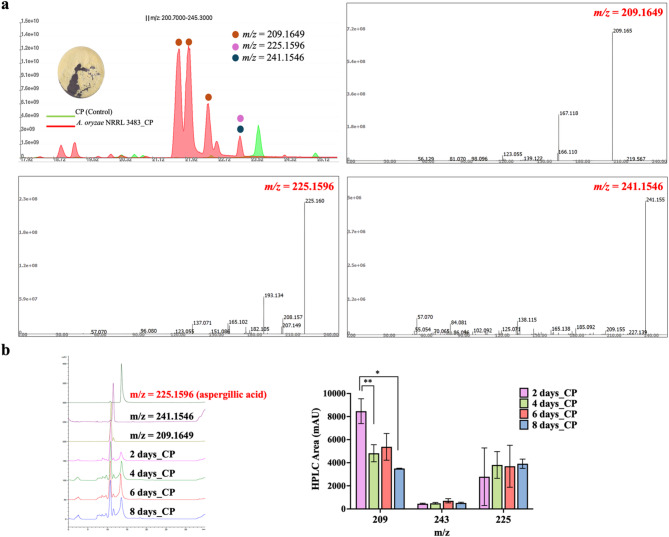

Detection of aspergillic acid and its analogues

To determine whether this transcriptional activation observed in A. oryzae NRRL 3483 resulted in aspergillic acid biosynthesis, culture extracts from CP medium were analyzed by LC–MS/MS (Fig. 4a). The extracts exhibited a faint yellow coloration, consistent with previous descriptions of aspergillic acid containing fractions10. From the extracted-ion chromatograms and MS/MS fragmentation profiles, the detected ions were assigned to deoxyaspergillic acid (m/z 209.1649, [M + H]+), aspergillic acid (m/z 225.1596, [M + H]+), and a putative hydroxylated derivative (m/z 241.1546, [M + H]+). The fragmentation pattern of deoxyaspergillic acid resembled that of aspergillic acid but lacked hydroxyl-related fragment ions, whereas the m/z 241.1546 signal showed neutral losses indicative of hydroxyl substitution. For aspergillic acid, the MS/MS spectrum showed diagnostic fragments at m/z 207.1495 (–H2O) and m/z 165.1023 (–C3H8O). This stepwise fragmentation (225 → 207 → 165) is a pattern previously reported for aspergillic acid under positive ionization11. Taken together, these data validate the structural assignments and align with published fragmentation profiles, despite the current unavailability of authentic standards in the United States. These ions were absent or negligible in CP medium alone as control, indicating that A. oryzae NRRL 3483 synthesized detectable levels of aspergillic acid related metabolites under amino acid rich conditions. HPLC quantification across a time course (2–8 days) demonstrated that metabolite levels remained relatively constant, without the sharp induction–peak–decline pattern observed from qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 4b). This suggests that A. oryzae. NRRL 3483 retains residual capacity for aspergillic acid biosynthesis. However, in addition to aspergillic acid, deoxyaspergillic acid (m/z 209.1649) was consistently detected at higher relative abundance compared to aspergillic acid. As the direct product of asaC, deoxyaspergillic acid lacks the N-hydroxyl group and requires further modification by asaD. The accumulation of deoxyaspergillic acid, coupled with only trace detection of aspergillic acid, suggests that although asaC is transcriptionally active in A. oryzae NRRL 3483, downstream tailoring steps catalyzed by asaD and asaB are weakly expressed or inefficient. The imbalance in metabolite profiles is consistent with the qRT-PCR data, where asaC showed the strongest induction relative to asaD and asaB. These results indicate that the pathway in A. oryzae NRRL 3483 is at least partially functional, but stalls at the deoxyaspergillic acid intermediate due to insufficient downstream activity.

Fig. 4.

Detection of aspergillic acid and related metabolites in Aspergillus oryzae NRRL3483 cultured in casein peptone (CP) medium. (a) LC–MS/MS analysis showing total ion chromatograms (TIC) of fractionated extracts from CP medium alone (control, green) and A. oryzae NRRL 3483 grown in CP (red) within the m/z range 200.7–245.3. Labeled peaks correspond to extracted-ion signals at m/z 209.1650 (putative deoxyaspergillic acid, [M + H]+), m/z 225.160 (putative aspergillic acid, [M + H]+), and m/z 241.155 with representative MS/MS fragmentation spectra shown. (b) HPLC analysis of metabolite extracts over a time course (2–8 days) (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

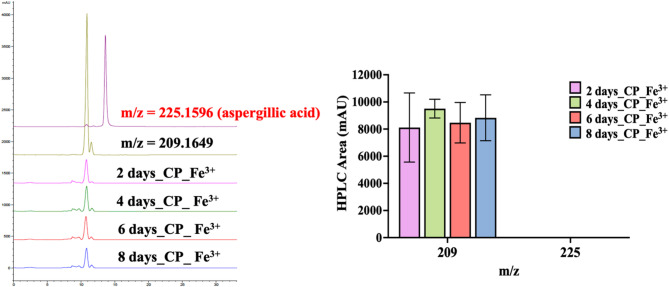

A property of aspergillic acid is its ability to chelate Fe3+ ions, forming the characteristic red ferriaspergillin complex6. In this study, a rapid qualitative assay was performed by adding ferric ammonium citrate directly to cultures of A. oryzae NRRL 3483 while growing in CP medium (Fig. 5). The extracts produced a visible red complex, indicating the presence of a metabolite capable of Fe3+ binding. HPLC analyses further supported this observation: although deoxyaspergillic acid was abundant, only aspergillic acid contributed to ferriaspergillin formation, since deoxyaspergillic acid lacks the hydroxamate group required for Fe3+ binding. These results demonstrate that CP medium (rich in leucine and isoleucine) can trigger partial activation of the asa pathway in A. oryzae NRRL 3483, generating sufficient aspergillic acid.

Fig. 5.

Iron chelation assay and HPLC analysis of aspergillic acid production in A. oryzae NRRL3483. Culture supernatants from A. oryzae NRRL 3483 grown in CP medium were supplemented with ferric ammonium citrate to assess ferriaspergillin complex formation. A visible red coloration indicated the presence of aspergillic acid capable of Fe3+ chelation. Complementary HPLC analysis quantified aspergillic acid and deoxyaspergillic acid levels.

Conclusion

This study provides a comparative framework for understanding aspergillic acid biosynthesis in A. flavus and A. oryzae. In A. flavus, the asa cluster was strongly induced in casein peptone medium, resulting in abundant production of aspergillic acid and its derivatives, along with robust iron-chelating activity. By contrast, A. oryzae strains displayed divergent behaviors: RIB40 remained transcriptionally silent and produced no detectable metabolites, whereas NRRL3483 activated the asa cluster, producing trace aspergillic acid and deoxyaspergillic acid sufficient for ferriaspergillin formation. These findings demonstrate that both environmental conditions and genetic background shape fungal secondary metabolism, and that domesticated A. oryzae retains a strain-specific, cryptic capacity for aspergillic acid biosynthesis. The disproportionate accumulation of deoxyaspergillic acid in NRRL3483 suggests a bottleneck in downstream tailoring steps, suggesting the need to investigate the regulatory and enzymatic controls governing flux through the aspergillic acid pathway.

As the asa cluster has only recently been identified, future research should focus on dissecting its regulatory architecture, exploring the enzymatic mechanisms underlying incomplete pathway activity, and expanding comparative analyses across diverse A. oryzae lineages and related Aspergillus taxa. Such efforts will clarify whether partial retention of aspergillic acid biosynthesis is strain-specific or broadly conserved. Ultimately, these insights will enhance our understanding of secondary metabolism in domesticated fungi and lay the groundwork for harnessing cryptic biosynthetic clusters in natural product discovery and biotechnological innovation.

Materials and methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

The fungal strains used in this study included Aspergillus flavus NRRL 3357 (a well-characterized aspergillic acid producer) and Aspergillus oryzae strains RIB40 and NRRL 3483. Stock cultures were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates for 4 days at 30 °C to induce sporulation. Conidia were harvested from PDA cultures by using 0.1% (v/v) Tween-80 solution. Spore suspensions were filtered through sterile Miracloth (Millipore Sigma, USA) to remove hyphal clumps and debris, and the concentration of spores was determined with a hemocytometer. Spore suspensions were then diluted to the desired inoculum density. Two liquid media were utilized to assess production of aspergillic acid. The first was Glucose Minimal Medium (GMM) as control, a defined minimal medium containing D-glucose as the primary carbon source, sodium nitrate as the nitrogen source, and a standard trace element solution. Per liter, GMM contained 10 g glucose, 50 mL of a 20 × nitrate salt solution (20 × nitrate salt: 120 g NaNO3, 10.4 g MgSO4·7H2O, 10.4 g KCl, and 30.4 g KH2PO4 per liter), and 1.0 mL of a 1000 × trace element solution (1000 × trace elements: 22 g ZnSO4·7H2O, 11 g H3BO3, 5 g MnCl2·4H2O, 5 g FeSO4·7H2O, 1.6 g CoCl2·5H2O, 1.6 g CuSO4·5H2O, 1.1 g (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, and 50 g Na2EDTA per liter). GMM is widely used as a model medium in fungal genetics and physiology, providing a controlled baseline for assessing secondary metabolism. The second was casein peptone medium (CP) is nutrient-rich, with casein hydrolysate as its principal nitrogen and carbon source. CP medium was prepared by dissolving 20 g of casein peptone in 1 L of deionized (DI) water. It supplies abundant peptides and free amino acids, including leucine and isoleucine12, which serve as precursors for aspergillic acid biosynthesis. CP was therefore chosen to test whether precursor availability and nutrient richness could promote activation of the biosynthetic pathway. For liquid culture, each flask (250 mL Erlenmeyer) containing 150 mL of medium was inoculated with spores to a final concentration of 5 × 105 conidia/mL. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. Time-course experiments were conducted by harvesting samples at 2, 3, 4, and 5 days post-inoculation to monitor gene expression and metabolite production over time.

Comparison of the aspergillic biosynthetic gene cluster between A. flavus and A. oryzae

Lebar et al.6 previously identified 12 genes in the aspergillic acid biosynthetic gene cluster of A. flavus NRRL3357, and their nucleotide sequences were retrieved from the European Nucleotide Archive (www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/EED55027-EED55038, EMBL-EBI, UK). To locate these genes, the genome sequences of A. flavus NRRL3357 (GCA_009017415.1), A. oryzae RIB40 (GCA_000184455.3), and A. oryzae NRRL3483 (GCA_034767915.1) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, Bethesda, USA). BLASTn analyses were conducted by querying the 12 genes against the genomes, using an e-value cut-off of 1e−513. The clustering of these 12 genes was confirmed based on BLASTn hits, and their respective chromosomes or contigs were identified.

Once the gene cluster was located, the corresponding chromosome or contig was analyzed with the online fungal antiSMASH tool (v8.0.2; https://fungismash.secondarymetabolites.org/) to predict the complete aspergillic acid biosynthetic cluster14. As the reference genome strains, the input data for A. flavus NRRL3357 and A. oryzae RIB40 were directly fetched from NCBI under the accession numbers NC_092409 and NC_036436, respectively. On the contrary, the sequence of A. oryzae NRRL3483 (GenBank: JAULKX010000066.1) has not been characterized, so gene prediction must be conducted prior to antiSMASH analysis. AUGUSTUS v3.5.0 was used for gene prediction, with A. oryzae as the reference species15. The AUGUSTUS input sequence file and the corresponding GFF output file were then submitted to antiSMASH for secondary metabolite cluster identification. Following antiSMASH analysis, the GenBank files of the predicted aspergillic acid biosynthetic clusters were downloaded and processed with clinker v0.0.31 to visualize and compare the clusters across the three strains16. BLASTn was conducted on the predicted cluster genes to match with the 12 genes previously studied by Lebar et al.6.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis

At each time point, fungal mycelia were harvested from the culture by filtration through four layers of Miracloth (Millipore Sigma, USA). The biomass was gently pressed to remove residual liquid, exposed to liquid nitrogen to freeze mycelia, lyophilized, and stored at − 80 °C until use. RNA was extracted from freeze-dried mycelia using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed by spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio), and only samples with high purity were used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis through the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Reverse transcription was performed at 25 °C for 10 min, 37 °C for 120 min, and 85 °C for 5 min, then held at 4 °C. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out on an Applied Biosystems real-time PCR system using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, USA). Thermal cycling conditions were: Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) activation at 50 °C for 2 min, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. All primer sets were designed and were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, USA). For A. flavus, β-tubulin was selected as the reference gene, while β-actin was used for A. oryzae. Primer sequences for target genes (asaC, asaD, asaB, asaR) and reference genes are provided in Table 1. Each biological sample was analyzed in triplicate qPCR reactions. Relative transcript levels from qRT-PCR were calculated using the comparative Ct (Δ∆Ct). First, the cycle threshold (Ct) value of each target gene was normalized to that of the reference gene to obtain ΔCt for both treatment and control samples. The difference between these two values (ΔΔCt) was calculated as17:

|

|

|

|

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR analysis of aspergillic acid biosynthetic genes.

| Primers | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| asaC-qF | CGGGTGTTTATCGGCTCTATC |

| asaC-qR | GCTAGGGACCTTCTGGTATTTG |

| asaD-qF | GTCCTGGAATCTGGTGTTCTT |

| asaD-qR | CTCTGGGCGATATGTGCTATT |

| asaR-qF | GGAACGGAGTCTGACGATTT |

| asaR-qR | CCGTGGAGTACCTATGACTTTG |

| asaB-qF | TGAGACCTGCTTGAACTATTGG |

| asaB-qR | GAAGAACGTAACTGGTGCGA |

| β-tubulin-qF (A. flavus) | CTTTCCCTCGTCTTCACTTCTT |

| β-tubulin-qR (A. flavus) | GACGAAGTAGGTCTGGTTCTTG |

| β-actin-qF (A. oryzae) | GACTTCGAGCAGGAGATTCAG |

| β-actin-qR (A. oryzae) | CCATGACGATGTTACCGTAGAG |

Target genes include asaC, asaD, asaR, and asaB, along with housekeeping genes (β-tubulin for A. flavus and β-actin for A. oryzae).

This approach compares the expression of a gene of interest in treated samples relative to a control condition. Statistical significance of expression differences was evaluated by t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns not significant).

Extraction of aspergillic acid and HPLC analysis

To extract aspergillic acid and its analogs in culture, we employed a liquid–liquid extraction protocol adapted from Park et al.18. At each time point, an equal volume of ethyl acetate was added to the culture filtrate and the mixture was vigorously shaken overnight to partition organic-soluble metabolites. Following phase separation, the ethyl acetate (upper) layer was collected, combined, and evaporated under a gentle air. The residue was reconstituted in 10 mL of 15% aqueous methanol, and an equal volume of n-hexane was added and mixed to partition away non-polar impurities. The upper hexane layer was discarded, and the lower methanolic layer (containing aspergillic acid and other moderately polar metabolites) was dried and dissolved with 2 mL 100% methanol. Fractionation of the extract was performed by reversed-phase chromatography (Millipore Sigma, USA), beginning with a high aqueous phase and progressing to an acetonitrile gradient. Aspergillic acid and its analogs were most enriched in fractions eluting with 60% water and 40% acetonitrile. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to detect aspergillic acid was performed with slight modification19. on an Agilent 1100 system equipped with a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 reversed-phase column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm particle size). The column was maintained at 30 °C. The mobile phase consisted of a linear gradient from 75:25 water: acetonitrile (with 0.1% formic acid) to 60:40 water:acetonitrile over 30 min, at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Eluting compounds were detected using a diode array UV–Vis detector set at 310 nm. Chromatograms were analyzed with Agilent software, and peak areas were integrated to estimate relative metabolite levels. Authentic standards of aspergillic acid and deoxyaspergillic acid were not available, so identification relied on spectral characteristics and mass spectrometric data.

Determination of aspergillic acid by LC–MS/MS

In addition to HPLC–DAD analysis, extracts were examined by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC–HRMS). Data were acquired on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer interfaced with a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Analyses were conducted in the Department of Food Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (Dr. Bolling’s laboratory). Dried extracts were reconstituted in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of water and acetonitrile prior to injection. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH-C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The mobile phases consisted of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid. The gradient program was as follows: 0–5 min, 90% B; 5–25 min, linear decrease to 10% B; 25–27 min, decrease to 2% B; 27–32 min, hold at 2% B; 32–35 min, return to 90% B; 35–37 min, re-equilibration at 90% B. Mass spectra were recorded through MAVEN v2.11.4.F in positive ion mode across an m/z range of 200.7–245.3.

Iron chelation (ferriaspergillin) assay

To qualitatively assess the presence of aspergillic acid in fungal cultures, an iron chelation assay was performed based on the characteristic formation of the ferriaspergillin complex. Aspergillic acid chelates ferric ions (Fe3+), producing a distinct red-colored ferriaspergillin complex. Ferric ammonium citrate was added at the initial cultures following a modified protocol of Lebar, et al.6. Metabolite extraction was carried out as described in the section “Extraction of aspergillic acid and HPLC analysis”, without the additional step of reversed-phase chromatography for fractionation. The final residue was dissolved in methanol to a concentration of 1 mg/mL and subjected to chromatographic quantification to confirm the presence or absence of aspergillic acid.

Acknowledgements

LC–MS/MS analyses were performed in the Department of Food Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in Dr. David Bolling’s laboratory.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: D.C., X.F., J.H.Y., and H-S. Park; Investigation: D.C., and H-S. Park.; Writing—original draft: D.C.; Writing—review and editing: X.F., H-S. Park; and J-H.Y.; Funding acquisition: J-H.Y.; Supervision: H-S. Park., and J-H.Y. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Michael and Winona Foster Predoctoral Fellowship awarded to D.C., the Hatch Project (No. 7000326) from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, awarded to J.-H.Y., and Food Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Keller, N. P. Fungal secondary metabolism: Regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.17, 167–180. 10.1038/s41579-018-0121-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mózsik, L., Iacovelli, R., Bovenberg, R. A. L. & Driessen, A. J. M. Transcriptional activation of biosynthetic gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.10.3389/fbioe.2022.901037 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutcher, J. D. Aspergillic acid: An antibiotic substance produced by Aspergillus flavus: III. The structure of hydroxyaspergillic acid. J. Biol. Chem.232, 785–795. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77398-0 (1958). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis, F. et al. Biofilm mode of cultivation leads to an improvement of the entomotoxic patterns of two Aspergillus species. Microorganisms8, 705. 10.3390/microorganisms8050705 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishimura, A., Okamoto, S., Yoshizako, F., Morishima, I. & Ueno, T. Stimulatory effect of acetate and propionate on aspergillic acid formation by Aspergillus oryzae A 21. J. Ferment. Bioeng.72, 461–464. 10.1016/0922-338X(91)90055-L (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebar, M. D. et al. Identification and functional analysis of the aspergillic acid gene cluster in Aspergillus flavus. Fungal Genet. Biol.116, 14–23. 10.1016/j.fgb.2018.04.009 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgianna, D. R. et al. Beyond aflatoxin: Four distinct expression patterns and functional roles associated with Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolism gene clusters. Mol. Plant Pathol.11, 213–226. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00594.x (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald, J. C. Biosynthesis of hydroxyaspergillic acid. J. Biol. Chem.237, 1977–1981. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)73969-6 (1962). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He, B. et al. Functional genomics of Aspergillus oryzae: Strategies and progress. Microorganisms7, 103. 10.3390/microorganisms7040103 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutcher, J. D. Aspergillic acid: An antibiotic substance produced by Aspergillus flavus: I. General properties; formation of desoxyaspergillic acid; structural conclusions. J. Biol. Chem.171, 321–339. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)41131-8 (1947). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saldan, N. C. et al. Development of an analytical method for identification of Aspergillus flavus based on chemical markers using HPLC-MS. Food Chem.241, 113–121. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.065 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilmour, S. R., Holroyd, S. E., Fuad, M. D., Elgar, D. & Fanning, A. C. Amino acid composition of dried bovine dairy powders from a range of product streams. Foods13, 3901. 10.3390/foods13233901 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform.10, 421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blin, K. et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res.53, W32–W38. 10.1093/nar/gkaf334 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics24, 637–644. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilchrist, C. L. M. & Chooi, Y.-H. clinker & clustermap.js: Automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics37, 2473–2475. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab007 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park, S. C. et al. Sortase a-inhibitory metabolites from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. Mar. Drugs18, 359. 10.3390/md18070359 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebar, M. D. et al. Small NRPS-like enzymes in Aspergillus sections Flavi and Circumdati selectively form substituted pyrazinone metabolites. Front Fungal Biol.3, 1029195. 10.3389/ffunb.2022.1029195 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon request.