Abstract

Background

Recently published phase III clinical trials documented that darolutamide could improve the prognosis of patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC). This meta-analysis aims to assess the efficacy of darolutamide in mHSPC based on subgroups and reconstructed individual-level data.

Methods

Literature was searched using PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrials.gov. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS), while the secondary outcomes included risk to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and adverse event. The risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was selected as effect size. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier method and Cox hazards model based on the reconstructed individual patient data (IPD). Z test and Bonferroni correction were applied for the comparison between subgroups. I2 ≤ 50% was regarded as low heterogeneity.

Results

The data of 1974 patients from two III phase trials, ARASENS and ARANOTE, were analyzed. For 1-year OS, the risk of death was 0.56 (95% CI: 0.41–0.78) in the darolutamide group comparing with the placebo group. The risk of death were 0.76 (95% CI: 0.64–0.91) and 0.75 (95% CI: 0.67–0.85) in the darolutamide group for 2-year OS and 3-year OS respectively. Darolutamide also decreased the risk of progression to CRPC within 3 years. Moreover, darolutamide demonstrated consistent OS benefits across different subgroups stratified by demographic and clinical characteristics with acceptable safety profile. Survival analyses demonstrated darolutamide improved OS and delayed disease progression even after adjusting for background therapy.

Conclusions

Darolutamide provides survival benefits and postpones the progression from mHSPC to the castration-resistant phase. The consistent efficacy across subgroups suggest that darolutamide could be a promising addition to combination therapy for mHSPC. Further investigation using original IPD is warranted to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-03875-4.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Androgen deprivation therapy, Darolutamide, Prognosis, Outcome.

Introduction

In 2024, 299,010 new prostate cancer (PCa) cases were diagnosed in the United States, of which 35,250 cases died [1]. Treatment for PCa involves multidisciplinary approaches, including androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy [2–4]. Among them, ADT is the cornerstone in the management of PCa [5]. Although it has high response to ADT, metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (mHSPC) is still considered as an incurable progressive condition [6]. In recent years, the treatment of mHSPC has been changed with the development of novel androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPIs) and combination regimens [7–9]. Thus, effective strategies with novel ARPIs are promising to postpone the progression of mHSPC to terminal castration-resistant phase.

Darolutamide is a structurally distinct and highly potent non-steroidal androgen receptor antagonist, characterized by low blood-brain barrier penetration and few drug-drug interactions [10]. Based on the results of the ARAMIS trial, darolutamide has been approved in the treatment of patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) [10, 11]. Subsequent two high-quality trials, ARASENS and ARANOTE, assessed the efficacy and safety of darolutamide plus ADT with or without chemotherapy and provided positive results for applying darolutamide in mHSPC [12, 13]. Although with different background therapy, the efficacy of darolutamide in two trials were consistent. However, the efficacy of darolutamide in subgroups still need elucidation.

Thus, we conducted this meta-analysis to explore the efficacy of darolutamide in the overall population and specific subgroups of mHSPC by using the full analysis set and reconstructed individual-level data from ARASENS and ARANOTE.

Methods

Literature search

This meta-analysis was conducted in adherence to the PRISMA guidelines [14]. Included studies were identified through a systematic searchof PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library. The most recent search was conducted in March, 2025. The search strategy included: “Prostate neoplasms” OR “Prostate cancer” AND “Darolutamide” AND filters of “Randomized controlled trial” OR “Clinical trial”. Additional articles were reviewed and selected manually in the ClinicalTrials.gov according to search terms, and the disagreements were resolved via consensus. The specific protocol of this study was submitted to PROSPERO (CRD420251013432).

Literature selection and data extraction

The inclusion criteria of this meta-analysis are: (a) prostate adenocarcinoma was diagnosed histologically or cytologically. (b) mHSPC was established. (c) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) containing darolutamide arm. (d) Study reporting survival outcomes and curves. (e) studies published in English. The background therapy with or without docetaxel chemotherapy was not restricted. Retrospective studies, reviews, case reports, commentaries and letters were excluded.

Data extraction

The data of darolutamide armand control group were extracted for pooling. All extracted data included publication profiles, patient characteristics, treatment protocols, survival outcomes and adverse events. Data extracted from the full analysis set was used for comparison. If stratified event counts were not reported, they were extracted from the published Kaplan-Meier curves. Two authors (ZL and QX) independently reviewed and extracted the data of selected studies, and the third author (WZ) was designated to resolve any disagreements in this section.

IPD reconstruction

Since the original dataset only contained Kaplan-Meier survival data rather than individual patient data (IPD), we reconstructed time-to-event IPD through survival curves using inverted Kaplan-Meier method [15, 16]. This method allowed us to extract patient-level survival data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves when original IPD were uneasily available, ensuring accurate reconstruction of survival distributions. We extracted the data from Kaplan-Meier curves using Engauge Digitizer software (version 12.1). Aggregated survival data was converted into simulated IPD for survival modeling [17]. In this process, the survival probability at each time point was estimated based on the existing Kaplan-Meier curve, and then the IPD of time-to-event outcomes were simulated according to reported event counts and numbers at risk.

Outcomes and quality assessment

The primary outcome of this meta-analysis was overall survival (OS). The secondary outcomes were risk to CRPC, and the adverse event (AE) without specifying symptoms. The quality assessment of studies was performed by 2 independent reviewers (XG and WZ) based on Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias (RoB) tool of Review Manager software. Domains were evaluated using the RoB tool, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other bias. Reviewers assessed the risk of bias by categorizing as low, unclear or high. Any discrepancies in this section were discussed until an agreement was reached.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed based on the full analysis set and the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Stratified meta-analyses were conducted based on common subgroups across the included studies. The pooled risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was selected as effect size for comparing the efficacy of darolutamide with placebo. The RR were calculated based on the event counts and ITT populations. The effect size (ES) was pooled by using the Mantel-Haenszel method under fixed-effect model (Common effect model), or using the inverse-variance method with τ² estimated by the restricted maximum‐likelihood (REML) estimator under the random-effects model. Both the common effect model and random effects model were used in analyses, and only the results of common effect model were described through this meta-analysis. If variables were not reported, such as the event counts, they were estimated through available data, such as ITT patients and survival rates extracted from Kaplan-Meier curves. Z test was used in pairwise comparison to compare the pooled RRs across different subgroups. Moreover, Bonferroni correction was applied to control Type I error when multiple comparisons were conducted. Heterogeneity was evaluated by the Cochran’s Q test and I2 test. I2 ≤ 50% was considered as indicating low heterogeneity.

Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier method. The survival differences between groups were compared with the log-rank test, and hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI was estimated from the Cox model. Meanwhile, the primary potential confounding factor, background therapy with or without docetaxel, was adjusted in the Cox proportional hazards regression. Publication bias was not assessed due to the small number of studies. The Review Manager software, and R 4.4.2 (survival, survminer, IPDfromKM, metafor and ggplot2 packages) were used in this meta-analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

The flowchart of searching and selecting literature is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 436 studies were screened after duplicates were removed, and 33 studies were assessed for eligibility of inclusion. After the exclusion of 31 studies, 2 published III phase trials, ARASENS (NCT02799602) and ARANOTE (NCT04736199), were included. The data of 1974 patients were stratified and analyzed eventually. The characteristics of two trials are shown in Table 1. The RoB summary of included studies are revealed in Figure S1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of searching literature. Flowchart of literature search, screening, and inclusion for this meta-analysis. The detailed description on included trials are provided in Table 1

Table 1.

Characteristics of included phase III clinical trials

| Author | Publication date | Journal | Baseline clinical characteristics of included patients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClinicalTrials.gov number | Median Age (year) | Median PSA (ng/ml) | Gleason score | Darolutamide protocol | Background therapy | Median treatment duration of darolutamide (month) | Median follow-up (month) | ||||

| ARASENS | Smith MR, et al. | 2022 | N Engl J Med | NCT02799602 | 67 | 27.3 |

< 8: 240 (18.4%) ≥ 8: 1021 (78.2%) Data missing: 44 (3.4%) |

600 mg, twice daily | ADT + docetaxel | 41 | 43.1 |

| ARANOTE | Saad F, et al. | 2024 | J Clin Oncol | NCT04736199 | 70 | 21.3 |

< 8: 189 (28.3%) ≥ 8: 457 (68.3%) Data missing: 23 (3.4%) |

600 mg, twice daily | ADT | 24 | 25.3 |

| Trials | Outcomes of darolutamide group at cutoff date | Outcomes of placebo group at cutoff date | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT Patients | OS rate | CRPC incidence | Any AEs | Serious AEs | Grade 5 AEs | ITT Patients | OS rate | CRPC incidence | Any AEs | Serious AEs | Grade 5 AEs | ||

| ARASENS | 651 | 65.8% | 35.0% | 99.5% | 44.8% | 4.1% | 654 | 53.5% | 60.0% | 98.9% | 42.3% | 4.0% | |

| ARANOTE | 446 | 76.9% | 34.5% | 91.0% | 23.6% | 4.7% | 223 | 73.1% | 64.1% | 90.0% | 23.5% | 5.4% | |

ADT Androgen deprivation therapy, AEs Adverse events, CRPC Castration-resistant prostate cancer, ITT Intent-to-treat, NCT National clinical trial, OS Overall survival, PSA Prostate-specific antigen

The efficacy of darolutamide

The pooled RRs with 95% CIs were applied to compare the efficacy between darolutamide and placebo group. For 1-year OS, the risk of death was 0.56 (95% CI: 0.41–0.78, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.5847) in the darolutamide group comparing with placebo group (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the risk of death were 0.76 (95% CI: 0.64–0.91, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.5523) and 0.75 (95% CI: 0.67–0.85, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.4270) for 2-year OS and 3-year OS in the darolutamide group (Fig. 2, B and C). Although the risk of death in the darolutamide group at 1 year was lowest, no significant differences among three subgroups were detected (All P > 0.05), suggesting that darolutamide may have consistent long-term efficacy.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for OS benefit in subgroups stratified by followup duration. Forest plot showing the effects of darolutamide on 1-year (A), 2-year (B) and 3-year OS (C). OS Overall survival, RR Risk ratio

For CRPC events, darolutamide decreased the risk of progression to CRPC within 3 years. The pooled RR of 1-year risk to CRPC was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.39–0.53, I2 = 71.7%, P = 0.0601) in darolutamide group in comparison to placebo group (Figure S2A). Moreover, The pooled RRs of 2-year risk and 3-year risk to CRPC in darolutamide group were 0.48 (95% CI: 0.44–0.54, I2 = 5.9%, P = 0.3025) and 0.52(95% CI: 0.48–0.57, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9583), respectively (Figure S2, B and C). No significant differences among the three subgroups were found (All P > 0.05). Although the heterogeneity in pooled estimates of 1-year risk to CRPC was significant, other two subgroups demonstrated homogeneous results, suggesting the efficacy of darolutamide on delaying disease progression.

The safety of darolutamide

The incidences of any AEs, serious AEs, grade3-4 and grade 5 AEs were similar between darolutamide and placebo groups. Pooled estimates of any AEs and serious AEs were 1.02 (95% CI: 1.00-1.03, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9001) and 1.06 (95% CI: 0.94–1.18, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.7331) (Figure S3, A and B). The risk of grade3-4 and grade 5 AEs in darolutamide were 1.04 (95% CI: 0.96–1.13, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.8480) and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.64–1.49, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.6917) comparing with placebo(Figure S3, C and D). Thus, the addition of darolutamide did not increase the risk of AEs in general. Meanwhile, nervous system-related AEs as special interest were explored. The risk of mental-impairment disorder, depressed-mood disorder and cerebral ischemia were 1.70 (95% CI: 0.92–3.14, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.4617), 0.84 (95% CI: 0.49–1.46, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.5871) and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.31–1.69, I2 = 51.2%, P = 0.1521) comparing with placebo, respectively (Figure S4).

The stratified meta-analysis

We conducted stratified meta-analysis to explore the efficacy of darolutamide on OS across different subgroups. For age, darolutamide revealed the satisfactory efficacy of increasing survival by 34%, 8% and 29% in patients aged under 65, 65 to 74 and 75 to 84 respectively (Fig. 3, A to C). Although patients aged over 85 did not benefit from darolutamide for OS, this discrepancy may attribute to small sample sample size of this subgroup (Fig. 3D). For subgroups with different prostate specific antigen (PSA) level and Gleason score, darolutamide decreased risk of death in these subgroups. Among them, the risk of death of darolutamide subgroups with high and low PSA levels were 0.83 (95% CI: 0.69–0.99, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9945) and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.62–0.86, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.2620) respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). Darolutamide decreased the risk of death of subgroups with Gleason score < 8 and ≥ 8 (RR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.55–1.01, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.8198 and RR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.70–0.91, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.3621, respectively)(Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of OS benefit in subgroups stratified by age. Forest plot showing the effects of darolutamide on OS in different subgroups at age < 65 (A), 65–74 (B), 75–84 (C) and 85 (D). OS Overall survival, RR Risk ratio

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of OS benefit in subgroups stratified by PSA level and Gleason score. Forest plot showing the effects of darolutamide on OS in different subgroups with PSA level < median (A) and ≥ median (B), Gleason score < 8 (C) and ≥ 8 (D). OS Overall survival, PSA Prostate-specific antigen, RR Risk ratio

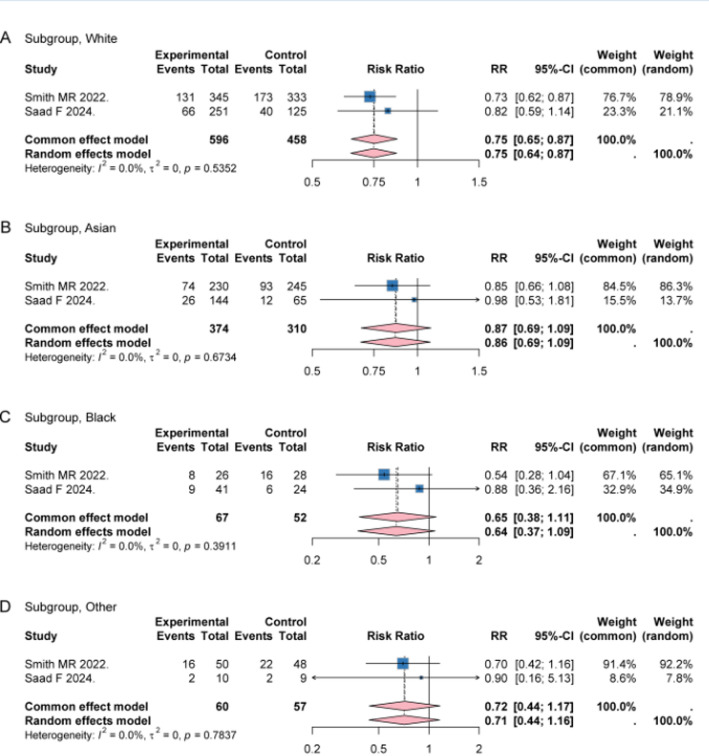

Darolutamide showed consistent efficacy of decreasing risk of death in subgroups with different race and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (Fig. 5 and Figure S5). Moreover, the pooled RR of OS among high-volume patients was 0.77 (95% CI 0.69–0.87, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.4981), consistent with the primary analysis, indicating that disease volume may not materially alter the estimated survival benefit of darolutamide (Figure S6). Additionally, for subgroups with or without visceral metastases, the pooled RRs of OS were 0.89 (95% CI: 0.71–1.12, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.7354) and 0.70 (95% CI: 0.62–0.80, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.5194) respectively (Figure S7). No significant heterogeneity and differences among subgroups were detected (All I2 < 50.0%, P > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Forest plots of OS benefit in subgroups stratified by race. Forest plot showing the effects of darolutamide on OS in different subgroups White (A), Asian (B), Black (C) and Other (D). OS Overall survival, RR Risk ratio

Subsequent life-prolonging anticancer therapy

The profiles of subsequent life-prolonging anticancer therapy was also explored. The pooled estimates of subsequent treatment with docetaxel, abiraterone, enzalutamide and cabazitaxel in darolutamide group were 0.80 (95% CI: 0.63–1.02, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.9025), 0.78 (95% CI: 0.66–0.93, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.3820), 0.54 (95% CI: 0.40–0.71, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.5042) and 1.02 (95% CI: 0.75–1.37, I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.7152) comparing with placebo, respectively (Figure S8). These results suggested that darolutamide treatment may decrease the subsequent treatment with docetaxel, abiraterone and enzalutamide, which reflect long-term efficacy of darolutamide in mHSPC.

Survival analyses

In this meta-analysis, the OS and risk to CRPC were analyzed by using the reconstructed IPD data. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed significant differences in OS and risk to CRPC between the darolutamide group and placebo group (Log-rank test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). The darolutamide group showed improved OS (HR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.62–0.84, P < 0.001)(Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, darolutamide decreased the risk of progression to CRPC (HR 0.39, 95% CI: 0.34–0.44, P < 0.001)(Fig. 6B). In Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, the survival benefit of darolutamide group remained unchanged after adjusting different background therapy. Taken together, these findings suggest that darolutamide provided survival benefits and delayed progression of mHSPC.

Fig. 6.

Survival curves of OS (A) and event-free to CRPC (B) containing the darolutamide group and the placebo group basing on reconstructed IPD. CRPC Castration-resistant prostate cancer, IPD Individual patient data, OS Overall survival, RR Risk ratio

Discussion

As one of the most prevalent cancers in males, PCa has a major health burden with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in metastatic phase [18]. ADT has been the cornerstone of treatment for PCa for a long time, particularly in the setting of mHSPC [19, 20]. Currently, ADT remains a mainstay in the management of mHSPC through reducing androgen levels and inhibiting androgen receptor signaling that is a pivotal role in driving tumor growth and metastasis [21]. Although most mHSPC patients initially have a favorable response to ADT, this condition inevitably progresses to CRPC that is lethal in most patients [22–24]. The progression of mHSPC to CRPC is a critical node in disease management, as it signifies a shift to a more aggressive, and heterogeneous state [24, 25]. In this regard, effective therapeutic option is crucial to improve the survival and quality of life for mHSPC patients.

The landscape of mHSPC treatment has evolved with the advent of novel ARPIs, such as apalutamide, enzalutamide, and darolutamide [26]. These agents have demonstrated superior efficacy in prolonging survival and delaying the progression in both non-metastatic and metastatic CRPC [27]. Apalutamide and enzalutamide have been shown to significantly extend OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in these populations, albeit with some central nervous system (CNS) side effects, such as fatigue, dizziness, and cognitive dysfunction [27, 28]. These adverse effects can significantly impair the quality of life of patients, particularly those who are elderly or have pre-existing cognitive impairments [29]. However, darolutamide is different from other androgen receptor inhibitors due to favorable pharmacokinetics profile [28]. Due to its lower blood-brain barrier penetration, darolutamide has fewer central nervous system AEs, providing a favorable option for elderly patients or those with cognitive impairments [30]. Moreover, the efficacy of darolutamide plus ADT, with or without chemotherapy, has been well documented in the ARASENS and ARANOTE trials [12, 13]. Thus, darolutamide has the potential to offer significant clinical benefits in terms of not only survival but also patient well-being, which is crucial in the management of mHSPC.

Our meta-analysis aimed to assess the efficacy of darolutamide in mHSPC patients by pooling data from two major phase III clinical trials, ARASENS and ARANOTE. Although background therapies used in the two trials were different, one involves the background ADT plus chemotherapy and the other involves ADT alone, our study found no significant heterogeneity in the pooled results. This consistency in outcomes was noteworthy, which may highlight the role of darolutamide across different combination protocols. Meanwhile, our analysis revealed that darolutamide significantly improved OS and reduced the risk of progression to CRPC. These findings are of great clinical significance, demonstrating that darolutamide can significantly delay the onset of CRPC regardless of chemotherapy, which might be important to optimize the treatment regimen of mHSPC. Moreover, due to CRPC is associated with poorer outcomes and limited treatment options, darolutamide may substantially alter the disease trajectory for mHSPC patients, offering a meaningful survival advantage.

The consistent efficacy of darolutamide across different patient subgroups were another important finding of this meta-analysis. Our results suggest that darolutamide provided substantial survival benefits at multiple time points (1-year, 2-year, and 3-year OS), emphasizing its long-term efficacy in mHSPC. Stratified analyses revealed that darolutamide were effective in improving OS in various subgroups defined by age, PSA level, Gleason score, and ECOG performance status. Specifically, darolutamide improved survival by 34% in patients aged under 65, by 8% in those aged 65 to 74, and by 29% in patients aged 75 to 84. Although the survival benefit was less pronounced in the elderly subgroup, this may be due to the smaller sample size and shorter follow-up in the ARANOTE trial. Darolutamide reduced the risk of death in patients with different PSA level and Gleason scores, which may highlight its broad applicability in mHSPC. These findings may suggest that darolutamide could benefit mHSPC patients regardless of key prognostic factors such as age, PSA or Gleason score. Furthermore, darolutamide demonstrated consistent efficacy across subgroups with different ECOG status, supporting its potential as a universal treatment option for mHSPC patients.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. Firstly, only two large phase III clinical trials were included, which represents a major limitation of the study. While these trials provide robust evidence, more RCTs across different geographic regions and demographic groups may provide deeper insights. Secondly, due to reconstructed data cannot fully replicate the granular details and nuances of original IPD, the use of reconstructed IPD in this meta-analysis may introduce bias in survival analyses. Future studies should aim to obtain original IPD to validate these findings and address the potential discrepancies associated with reconstructed IPD. Thirdly, a further limitation is that the ARANOTE trial enrolled both high- and low-volume patients, while ARASENS included only high-volume patients. Thus, we extracted data of subgroup with high-volume in ARANOTE trial and performed a subgroup meta-analysis. However, the lack of reconstructed IPD for these subgroups may biased the results of overall IPD analyses. Fourth, different background therapy of ARANOTE and ARASENS, with or without docetaxel use, may affect the overall results. Finally, as the therapeutic landscape of PCa continues to evolve, future studies could explore the combination of darolutamide with other emerging therapies, such as immunotherapies or novel targeted agents, to identify the most effective treatment regimens for mHSPC patients.

Conclusions

Darolutamide shows survival benefits and postpones the progression from mHSPC to the castration-resistant phase. The consistent efficacy across subgroups highlight that darolutamide might be a promising addition to the combination therapy for mHSPC. Further investigation containing original IPD is warranted to confirm these findings and optimize the combination regimen of mHSPC in clinical setting.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciate all investigators and participants of ARASENS and ARANOTE. Authors thank for the assistance of Dr. Xusheng Zhu of UCL.

Author contributions

(I)Conception and design: Fuxun Zhang; Qiang Fu; Geng Zhang; (II)Administrative support: Yong Jiao; Geng Zhang; (III)Provision of study materials or patients: Fuxun Zhang; Zhirong Luo; Qi Xue; Xuyan Guo; (IV)Collection and assembly of data: Fuxun Zhang; Zhirong Luo; Qi Xue; Yang Xiong; Xuyan Guo; (V)Data analysis and interpretation: Fuxun Zhang; Zhirong Luo; Qi Xue; Wei Zhang; Yang Xiong; (VI) Manuscript writing: Fuxun Zhang; Zhirong Luo; Pati-Alam Alisha; Uzoamaka Adaobi Okoli; (VII)Final approval of manuscript: Fuxun Zhang; Zhirong Luo; Qi Xue; Xuyan Guo; Qiang Fu; Wei Zhang; Yang Xiong; Pati-Alam Alisha; Uzoamaka Adaobi Okoli; Geng Zhang; Yong Jiao. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship in this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study is not a clinical trial, and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Fuxun Zhang and Zhirong Luo have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Geng Zhang, Email: zuibingling@163.com.

Yong Jiao, Email: jiaoyong2023@163.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu L, Pan J, Mou W, et al. Harnessing artificial intelligence for prostate cancer management. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(4):101506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaugier L, Morvan C, Pasquier D, et al. Long-term outcomes and patterns of relapse following high-dose elective salvage radiotherapy and hormone therapy in oligorecurrent pelvic nodes in prostate cancer: OLIGOPELVIS (GETUG-P07). Eur Urol. 2025;87(1):73–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azad AA, Kostos L, Agarwal N, et al. Combination therapies in locally advanced and metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2025;87(4):455–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, et al. Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain M, Fizazi K, Shore ND, et al. Metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer and combination treatment outcomes: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(6):807–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsaur I, Mirvald C, Surcel C. Triple therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2023;33(6):452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(2):121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang F, Luo Z, Xue Q et al. The efficacy of abiraterone in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a stratified meta-analysis based on subgroups of low or high disease volume and reconstructed individual patient data. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2025:Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Markham A, Duggan S, Darolutamide. First Approval Drugs. 2019;79(16):1813–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fizazi K, Shore N, Tammela TL, et al. Darolutamide in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(13):1235–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MR, Hussain M, Saad F, et al. Darolutamide and survival in metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(12):1132–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saad F, Vjaters E, Shore N, et al. Darolutamide in combination with androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer from the phase III ARANOTE trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(36):4271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, et al. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papadimitropoulou K, Stijnen T, Riley RD, et al. Meta-analysis of continuous outcomes: using Pseudo IPD created from aggregate data to adjust for baseline imbalance and assess treatment-by-baseline modification. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(6):780–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathianathen NJ, Lawrentschuk N, Konety B, et al. Cost effectiveness of systemic treatment intensification for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: is triplet therapy cost effective? Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7(4):870–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wala J, Nguyen P, Pomerantz M. Early treatment intensification in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(20):3584–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menges D, Yebyo HG, Sivec-Muniz S, et al. Treatments for metastatic Hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: systematic Review, network Meta-analysis, and Benefit-harm assessment. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5(6):605–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SS, Bian XJ, Wu JL, et al. Network meta-analysis of combination strategies in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2024;26(4):402–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teo MY, Rathkopf DE, Kantoff P. Treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:479–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raychaudhuri R, Lin DW, Montgomery RB. Prostate Cancer: Rev JAMA. 2025;333(16):1433–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raval AD, Chen S, Littleton N, et al. Real-world use of androgen-deprivation therapy intensification for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2025;135(3):408–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paolieri F, Sammarco E, Ferrari M, et al. Front-line therapeutic strategy in metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer: an updated therapeutic algorithm. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2024;22(4):102096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N. Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(3):354–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cattrini C, Caffo O, De Giorgi U, et al. Apalutamide, darolutamide and enzalutamide for nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC): a critical review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(7):1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenzel M, Nocera L, Collà Ruvolo C, et al. Overall survival and adverse events after treatment with darolutamide vs. apalutamide vs. enzalutamide for high-risk non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25(2):139–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lange M, Laviec H, Castel H, et al. Impact of new generation hormone-therapy on cognitive function in elderly patients treated for a metastatic prostate cancer: Cog-Pro trial protocol. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams SCR, Mazibuko N, O’Daly O, et al. Comparison of cerebral blood flow in regions relevant to cognition after enzalutamide, darolutamide, and placebo in healthy volunteers: a randomized crossover trial. Target Oncol. 2023;18(3):403–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.