Abstract

The Arabidopsis shepherd (shd) mutant shows expanded shoot apical meristems (SAM) and floral meristems (FM), disorganized root apical meristems, and defects in pollen tube elongation. We have discovered that SHD encodes an ortholog of GRP94, an ER-resident HSP90-like protein. Since the shd phenotypes in SAM and FM are similar to those of the clavata (clv) mutants, we have explored the possibility that CLV complex members could be SHD targets. The SAM and FM morphology of shd clv double mutants are indistinguishable from those of clv single mutants, and the wuschel (wus) mutation is completely epistatic to the shd mutation, indicating that SHD and CLV act in the same genetic pathway to suppress WUS function. Moreover, the effects of CLV3 overexpression that result in the elimination of SAM activity were abolished in the shd mutant, indicating that CLV function is dependent on SHD function. Therefore, we conclude that the SHD protein is required for the correct folding and/or complex formation of CLV proteins.

Keywords: CLAVATA/GRP94/meristem/molecular chaperon/SHEPHERD

Introduction

Meristems are undifferentiated tissues of higher plants occurring at the shoot apex and root tip, where vigorous cell division occurs to produce cells for the developing plant body. The shoot apical meristem (SAM) is the source of all above-ground organs (Brand et al., 2001; Clark, 2001; and references therein), whereas the root apical meristem (RAM) is the source of the root systems (Aeschbacher et al., 1994; van den Berg et al., 1998). Cells at the SAM summit serve as stem cells that slowly divide and continuously displace daughter cells to the surrounding peripheral region, where they proliferate rapidly and are incorporated into differentiating leaf or flower primordia (Brand et al., 2001; Clark, 2001). As flowers derive originally from shoots, the apical part of the flower primordium is composed of meristematic tissue, referred to as the floral meristem (FM) (Running and Hake, 2001).

Genetic analyses using Arabidopsis mutants have identified genes involved in the maintenance of the SAM and FM. A mutation in the homeobox gene WUSCHEL (WUS) results in the mis-specification of stem cells and the premature termination of the SAM and FM after only a few organs have been formed. It is proposed that WUS-expressing cells act as an organizing center for the SAM and FM and signal overlying neighbor cells to specify them as pluripotent stem cells (Laux et al., 1996; Mayer et al., 1998).

The CLAVATA (CLV1, CLV2 and CLV3) genes promote the progression of peripheral stem cell daughters toward organ initiation. Mutations in any of these genes result in the delay of this progression, leading to an accumulation of stem cells and to a gradual increase in the size of the meristem domes of SAM and FM (Clark et al., 1993, 1995; Kayes and Clark, 1998; Laufs et al., 1998). The CLV1, CLV2 and CLV3 genes encode a transmembrane receptor-kinase, a receptor-like protein similar to CLV1 but lacking a cytoplasmic signaling domain, and a small, secreted polypeptide, respectively (Clark et al., 1997; Fletcher et al., 1999; Jeong et al., 1999). Biochemical analysis has revealed that CLV1 forms an active complex with CLV2, which is associated with a kinase-associated protein phosphatase (KAPP) and a Rho GTPase-related protein (ROP) (Trotochaud et al., 1999) and that CLV3 binds to the complex in vivo (Trotochaud et al., 2000). It has also been shown that the CLV3 binds to intact yeast cells expressing both CLV1 and CLV2 at the cell surface (Trotochaud et al., 2000). Thus, it is believed that CLV3 acts as the ligand for the CLV1/CLV2 complex and that the binding of CLV3 to CLV1/CLV2 is required for the formation of the active complex (Waites and Simon, 2000; Brand et al., 2001; Clark, 2001).

Since wus clv double mutants are almost indistinguishable from the wus single mutant, it has been proposed that WUS is a target for negative regulation by the CLV genes (Laux et al., 1996). When the CLV3 gene is overexpressed, WUS expression is eliminated from the shoot apex, which results in the wus phenotype (Brand et al., 2000). The elimination of WUS expression is fully dependent on the presence of functional CLV1 and CLV2 genes. Therefore, it was concluded that the active CLV complex works for the repression of WUS at the level of its transcription (Brand et al., 2000). Recently, it has been proposed that CLV3 expression is controlled by a negative feedback loop through WUS expression, and that the number of stem cells is determined by the parameters of WUS–CLV3 interaction (Brand et al., 2000; Doerner, 2000; Schoof et al., 2000; Waites and Simon, 2000; Brand et al., 2001; Clark, 2001).

Secreted proteins, such as CLV3, and large extracellular domains of membrane proteins, such as those of CLV1 and CLV2, are synthesized on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, enter into the ER lumen, and are transported to the plasma membrane by vesicular transport machinery. Along this pathway some proteins may require molecular chaperones for correct folding (Gething and Sambrook, 1992). Most of the ER-resident molecular chaperones are abundant proteins in the ER (Koch, 1987; Macer and Koch, 1988). Among them, an HSP90-like protein is designated as the glucose-regulated protein of 94 kDa (GRP94), which is also referred to as gp96, endoplasmin, ERp99, or HSP108 in many vertebrates (Argon and Simen, 1999; Lee, 2001). The requirement for this protein is increased in cells under ‘ER stress’, conditions in which unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, induced by phenomena such as glucose starvation or glycosylation inhibition (Kaufman, 1999). As in the case of cytosolic HSP90, GRP94 also has a role under non-stress conditions; for example, this protein binds to the unassembled immunoglobulin chains after a preceding prefolding step by another molecular chaperone, GRP78 (BiP) (Melnick et al., 1994). In addition, the mammalian GRP94 has been shown to bind a broad array of peptides, including those derived from normal proteins, as well as from foreign and altered proteins present in cancer or virus-infected cells (Nicchitta, 1998). Putative orthologs of GRP94 have been identified in higher plants, Madagascar periwinkle and barley. It was reported that these genes are slightly induced by heat shock treatment, pathogen infection or cell culturing, and that the Madagascar periwinkle protein is associated with the ER (Schröder et al., 1993; Walther-Larsen et al., 1993). However, their target proteins and their biological functions have never been identified.

In this paper, we report our functional analysis of the SHEPHERD (SHD) gene of Arabidopsis. A mutation in SHD causes a pleiotropic phenotype, namely, expansion of the SAM and FM, disorganized cell arrangement in the RAM, and defects in pollen tube elongation. Of these, the SAM and FM phenotype is indistinguishable from the phenotypes of the clv mutants. From genetic and molecular biological analysis, we show that the SHD gene encodes the ortholog of GRP94, and that the SHD protein is required for the activation of the CLV1/CLV2 receptor complex and/or the CLV3 ligand. The name SHEPHERD refers to a protein that helps the CLV proteins (sheep) to form a regular complex (flock).

Results

SHEPHERD gene is required for meristem function

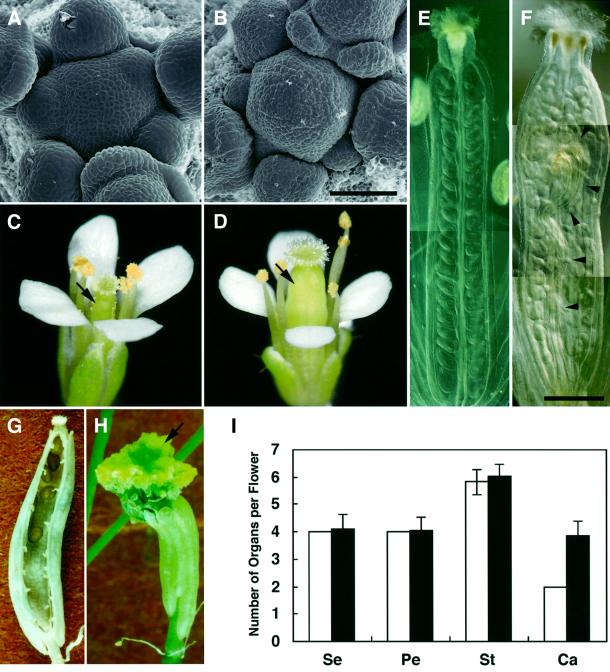

From 1500 lines of an Arabidopsis T-DNA insertional mutagenized population, we found a mutant, designated shepherd (shd), which is characterized by an enlarged dome-shaped SAM (Figure 1A and B). In the vegetative and young inflorescence stages, the SAM of the shd mutant appears taller than that of the wild type, while not remarkably larger in circumference. However, at a later stage, the inflorescence SAM becomes gradually fasciated. The shd mutation also affects the shape of the FM, from which a thick pistil is formed (Figure 1C and D). Under our standard growth conditions (22°C), the average number of carpels in shd flowers is 3.9 ± 0.5, which is nearly twice as many as is found in wild-type flowers (Figure 1E–I). In the interior of the thick pistils formed on the fourth whorl, shd flowers often form an additional (fifth) whorl of organs that develop into a gynoecium (Figure 1F and H). In a few flowers, the number of outer-whorl organs, sepals, petals and stamens is also increased. These features are similar to those observed in weak and intermediate alleles of clv (clv1, clv2 and clv3) mutants (Clark et al., 1993, 1995; Kayes and Clark 1998).

Fig. 1. SAM and FM phenotype of the shd mutant. (A and B) Wild-type (WS) SAM (A) and enlarged shd SAM (B). Bar: 50 µm. (C and D) Wild-type flower (C) and shd flower with a thick pistil (D). Arrows indicate pistils. (E and F) Wild-type pistil (E) and shd pistil (F) of fully opened flowers after clearing treatment. In the shd pistil, extra rows of ovules and fifth-whorl gynoecium (arrowheads) are apparent. Bar: 500 µm. (G) Seed pod of a shd plant consisting of four carpels. A front carpel has been removed. (H) Seed pod formed on a shd plant at a later growth stage. Fifth-whorl gynoecia (arrow) are enlarged and appear after breaking through the fourth-whorl carpels. (I) The number of organs in wild-type and shd mutant flowers. Bars represent the mean number of organs in flowers of the wild-type (WS; open bar) and the shd mutant (filled bar) plants grown at 22°C. At least 43 flowers detached from four primary inflorescences were counted for each mean. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Note that all wild-type flowers examined had four sepals, four petals and two carpels, so the standard deviations were zero. Se, sepal; Pe, petal; St, stamen; Ca, carpel.

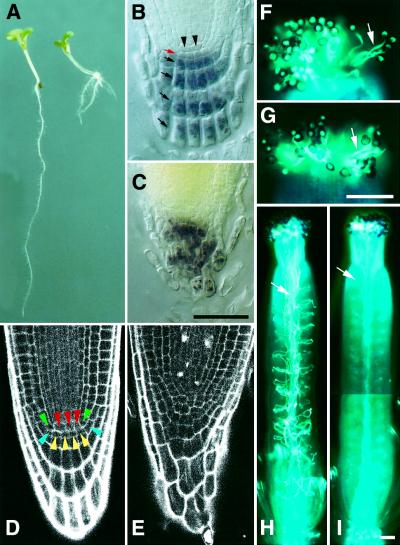

In contrast to the SAM- and FM-specific phenotype of clv mutants, the shd mutation also affects the activity of the RAM. Root elongation is reduced in shd seedlings, whereas the formation of lateral roots is enhanced (Figure 2A). In the RAM of the shd mutant, the stereotyped cell arrangement observed in the wild-type RAM is disorganized, and the central cells and surrounding initials are difficult to identify (Figure 2B–E). The root tissue most affected is the columella root cap, in which cell layers reflecting the synchronous cell division of columella initials have disappeared.

Fig. 2. RAM and pollen phenotypes of the shd mutant. (A) Seven-day-old seedlings of the wild type (WS, left) and shd mutant (right). Root elongation is reduced, whereas lateral root formation is enhanced in the shd seedling. (B and C) Arrangement of columella root cap cells in 11-day-old seedlings. Starch granules, a specific marker for differentiated columella cells, are visualized by starch staining. Four layers of differentiated columella cells (black arrows), columella initials (red arrow) and central cells (arrowheads) are visible in the wild-type root (B), whereas shd columella cells are disorganized (C). Bar: 50 µm. (D and E) Cell arrangement in the RAM region. Seven-day-old seedlings were examined using confocal laser scanning microscope. Central cells and typical arrangement of initial cells (van den Berg et al., 1998) are visible in the wild-type root (D), whereas the cell arrangement is disorganized and central cells cannot be identified in the shd root (E). Red, central cells; green, cortex/endodermis initials; blue, epidermis/lateral root cap initials; yellow, columella initials. (F and G) Germinated pollen grains attached to stigmas. Pollen tubes (arrows) are visualized by aniline blue staining. Wild-type (F) and shd (G) pollen grains were pollinated on dad1 stigmas. Bar: 100 µm. (H and I) Pollen tube elongation in pistils. Wild-type (H) and shd (I) pollen grains were pollinated on dad1 stigmas. In the shd mutant, only a few pollen tubes are growing in the pistil. Arrows indicate pollen tubes. Bar: 100 µm.

SHD also possesses gametophytic function

Backcrossed F1 plants recovered a complete wild-type phenotype, thus shd appears to be a recessive mutant. Genetic mapping using molecular markers revealed that the shd mutant carries a mutation mapped around the AG marker on chromosome 4 (data not shown). However, segregation of the shd mutation in backcrossed F2 progeny deviated from the 3:1 ratio expected for a single recessive mutation. Genotype analysis of these progeny revealed reduced inheritance of the shd mutation (Table I), suggesting that the shd mutation affects the function of gametophytes. To determine whether the male or female gametophyte is affected, we performed reciprocal crosses between heterozygote (SHD/shd) and wild-type (SHD/SHD) plants, and between heterozygote and shd mutant (shd/shd) plants (Table I). When heterozygotes were used as female parents, both SHD and shd genes were equally inherited by F1 progeny. However, when heterozygotes were used as male parents, the shd gene was rarely inherited. Thus, male gametophytes (pollen grains) require the function of the SHD gene for fertility.

Table I. Inheritance of shd mutation through male and female gametophytes.

| Crosses |

Generation | Genotypesa |

χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | SHD/SHD | SHD/shd | shd/shd | ||

| shd/shd | SHD/SHD | F2 | 261 | 279 | 42 | 165.8b |

| SHD/shd | SHD/SHD | F1 | 85 | 74 | – | 0.76c |

| SHD/SHD | SHD/shd | F1 | 149 | 3 | – | 140.2d |

| SHD/shd | shd/shd | F1 | – | 57 | 50 | 3.54e |

| shd/shd | SHD/shd | F1 | – | 160 | 9 | 134.9f |

aHygromycin B-sensitive seedlings, hygromycin B-resistant seedlings with wild-type phenotype in roots, and hygromycin B-resistant seedlings with mutant phenotype in roots are represented as SHD/SHD, SHD/shd and shd/shd genotypes, respectively.

bχ2 expected ratio, 1 SHD/SHD: 2 SHD/shd: 1 shd/shd; P <0.001.

cχ2 expected ratio, 1 SHD/SHD: 1 SHD/shd; P >0.05.

dχ2 expected ratio, 1 SHD/SHD: 1 SHD/shd; P <0.001.

eχ2 expected ratio, 1 SHD/shd: 1 shd/shd; P >0.05.

fχ2 expected ratio, 1 SHD/shd: 1 shd/shd; P <0.001.

To further define the defects of male gametophytes, pollen grains isolated from shd flowers were attached to the stigmas of male-sterile dad1 mutants, the anthers of which cannot dehisce at flower opening, thus rendering the dad1 mutants convenient when self pollination must be precluded (Ishiguro et al., 2001). The pollen grains germinated effectively on the stigmas, but the pollen tubes rarely elongated into the styles (Figure 2F–I). The same result was observed when wild-type stigmas were used for pollination. These results indicate that the SHD gene is required for pollen-tube elongation or penetration into the style.

Temperature sensitivity of the shd phenotype

To examine the effects of temperature on the phenotypic defects of the shd mutant, we grew the mutant plants under low (16°C), normal (22°C) and high (29°C) temperatures. At 29°C, the number of carpels was slightly increased and largely developed fifth-whorl gynoecia appeared more frequently inside the pistils (Figure 3F–H). In contrast, normal pistils consisting of two carpels were formed and no fifth-whorl gynoecia were observed in most flowers grown at 16°C (Figure 3B). All other phenotypes of the shd mutant were enhanced at high temperatures and suppressed at low temperatures (data not shown), suggesting that the effects of the shd mutation are induced in a temperature-dependent manner. However, it should be noted that the shd mutation is a null allele (see below).

Fig. 3. Temperature-sensitive alteration of pistil phenotype. (A) Wild-type (WS) flower grown at 16°C. (B) shd flower grown at 16°C. (C) Wild-type flower grown at 22°C. (D) shd flower grown at 22°C. (E) Wild-type flower grown at 29°C. (F) shd flower grown at 29°C. Front organs were removed to reveal the pistils. (A–F) are the same magnifications. Bar: 1 mm. (G and H) Cleared shd pistil of a flower grown at 29°C. (H) An enlargement of the boxed region in (G). Arrows indicate stigma-like structures of enlarged fifth-whorl gynoecium. Bar: 100 µm.

Molecular cloning of the SHD gene

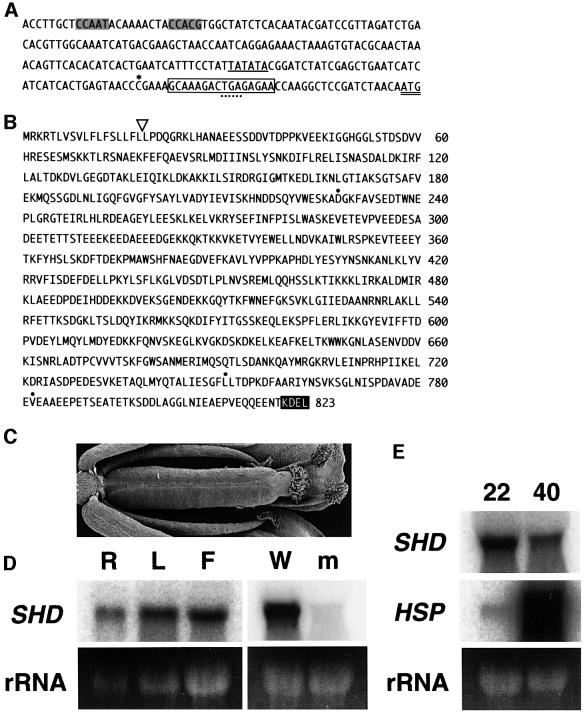

Plant sequences flanking the left and right borders of the T-DNA insertion in the shd mutant were isolated to construct primers for co-segregation analysis. We showed that 68 mutant plants isolated from a backcrossed F2 population contained homozygous T-DNA, indicating tight linkage between the shd mutation and the T-DNA insertion. The genomic region surrounding the T-DNA insertion was cloned and sequenced (Figure 4A). A single copy of T-DNA was inserted, in place of a 16 bp deletion, in a genomic region immediately upstream of the open reading frame of a predicted gene designated T22A6.20 (At4g24190) in the Arabidopsis genome initiative (AGI) databases. We determined the sequence of the longest expressed sequence tag (EST) clone corresponding to this gene, and confirmed that the T-DNA was inserted in the 5′ untranslated region of this gene.

Fig. 4. Structure and expression of the SHD gene. (A) Promoter and 5′-untranslated region of the SHD gene. The last three nucleotides represent the initiation codon for SHD protein (double underline). The boxed 16 bp region was substituted with a copy of T-DNA in the shd mutant, and was located downstream of the 5′ end of the longest cDNA clone (asterisk). An in-frame termination codon in the 5′-untranslated region is indicated by a dotted underline. A putative TATA box and a typical ER stress response element (ERSE) (Yoshida et al., 1998) are underlined and shaded, respectively. The DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession numbers for the SHD gene (WS ecotype) and SHD cDNA (EST clone 177P12T7, Columbia ecotype) are AB064527 and AB064528, respectively. (B) The deduced amino acid sequence of SHD in the Arabidopsis WS ecotype. The open triangle indicates the putative cleavage site of the predicted signal peptide. The C-terminal ER retention signal, KDEL, is highlighted. Three amino acid residues indicated by dots are substituted for N228, I751 and I782, respectively, in the counterpart of Columbia ecotype. (C) A flower from an shd plant transformed with the 6.7 kb XhoI–EcoRI fragment, which formed a pistil indistinguishable from wild-type pistils. (D) RNA gel blot analysis of SHD. Total RNA (10 µg) isolated from wild-type Arabidopsis organs (left panel) and 20 µg total RNA isolated from flower bud clusters (with shoot apices) of wild-type and shd (right panel) were blotted and probed with SHD cDNA. R, root; L, rosette leaves; F, flower bud clusters with shoot apices; W, wild type; m, shd mutant. The 25S rRNA bands visible on the ethidium bromide-stained gel were used as the loading control. (E) Expression of SHD and HSP81 genes after heat treatment. Total RNA (20 µg) isolated from rosette leaves of heat-treated (40°C) or control (22°C) seedlings was blotted and sequentially hybridized with the SHD probe (SHD) and the HSP81-1 probe (HSP). Because of their sequence similarity, the HSP81-1 probe detects mRNA of all HSP81 genes, i.e. HSP81-1 to HSP81-4. The 25S rRNA bands visible on the ethidium bromide-stained gel were used as the loading control.

The predicted SHD gene consists of 15 exons separated by 14 introns, and encodes a polypeptide composed of 823 amino acid residues (Figure 4B), which is homologous (48% identity) to the mammalian GRP94 protein across their entire amino acid sequences (Argon and Simen, 1999; Lee, 2001). Similar genes were previously identified from barley and Madagascar periwinkle (Schröder et al., 1993; Walther-Larsen et al., 1993). The sequence possesses both the characteristic N-terminal signal peptide and the C-terminal ER-retention signal, KDEL, indicating that this protein is localized in the ER. Thus, the predicted SHD protein appears to be an ortholog of GRP94. After removing the putative signal peptide, the molecular weight of this protein is calculated to be 92 000.

To confirm this gene is SHD, we transformed shd mutants with a 6.7 kb fragment containing the entire transcribed region (3.9 kb), the 5′ upstream region (1.6 kb) and the 3′ downstream region (1.2 kb). The transformants exhibited complete suppression of all mutant phenotypes (Figure 4C).

It was recently reported that there are seven members of HSP90 family genes (AtHsp90-1 to AtHsp90-7) in the Arabidopsis genome (Krishna and Gloor, 2001). Among them, only SHD (AtHsp90-7) has the structural features necessary for localization in the ER; thus SHD appears to be the only ortholog of GRP94 in Arabidopsis.

Expression of the SHD gene

Total RNA was collected from flower bud clusters (with shoot apices), rosette leaves and roots, and used for RNA gel blot analysis. SHD mRNA was detected in all tissues, which is consistent with the pleiotropic phenotype of the shd mutation (Figure 4D). No signal was detected in the RNA of mutant flower buds, as expected from the disruption of the SHD gene by a T-DNA insertion immediately downstream from the transcription initiation site (Figure 4A and D). This indicates that the shd mutation is a null allele.

To determine whether SHD gene expression is induced by heat treatment, we incubated plants at 40°C for 2 h and collected RNA from their rosette leaves. SHD mRNA was detected, but the amount was reduced in heat-treated plants, whereas the mRNA for HSP81 genes, which encode orthologs of cytosolic HSP90, was dramatically increased (Figure 4E). These results are consistent with the absence of known heat shock elements in the SHD promoter, which are highly conserved in the HSP81 promoters (Takahashi et al., 1992; Yabe et al., 1994). There seems to be a discrepancy between heat reduction of SHD gene and heat induction of other known plant and vertebrate GRP94 genes (Lee, 1987; Schröder et al., 1993; Walther-Larsen et al., 1993). However, at least vertebrate GRP94 genes also lack the heat shock element in their promoter, and thus the heat induction of these genes probably occurs through the induction of ER stress (Argon and Simen, 1999; Lee, 2001). It is likely that our heat treatment severely damaged Arabidopsis cells, which no longer responded to the ER stress.

Genetic interactions between SHD and other genes affecting meristem development

To identify the molecular function of the SHD gene product, we focused on the SAM and FM phenotype of the shd mutant. Since the SAM and FM phenotype of this mutant closely resembles those of the clv mutants, shd clv double mutants were generated to determine whether the shd mutant acts in the same genetic pathway as the clv mutants. If the SHD and CLV genes work in the same pathway to control SAM and FM development, then the shd clv double mutants should have a phenotype similar to a strong clv single mutant. If, however, CLV genes work in different pathways to control meristem development, then the shd clv double mutants might display novel or exaggerated phenotypes.

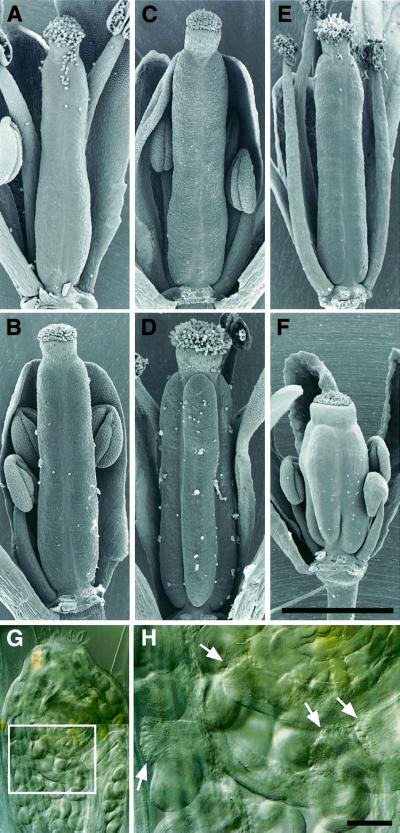

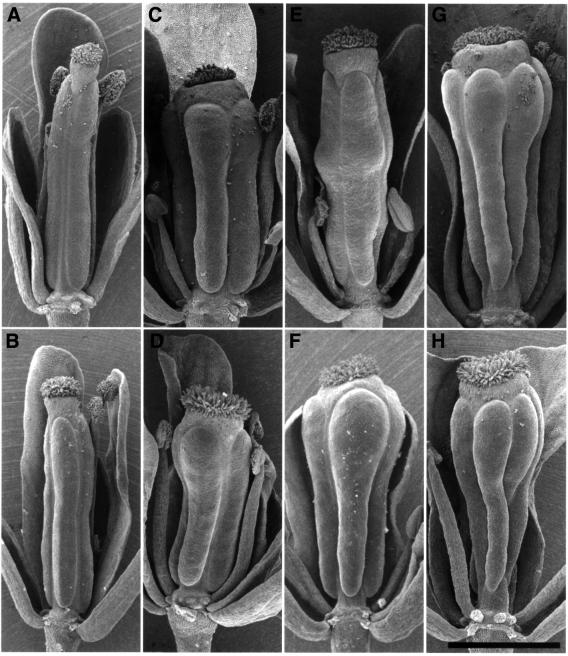

The pistil shapes of shd clv1-4 and shd clv3-1 are nearly identical to those of strong clv1-4 and intermediate clv3-1 single mutants, respectively (Figure 5C, D, G and H). The SAM sizes of these double mutants are also similar to those of clv single mutants (data not shown). In contrast, the pistil diameter of the shd clv2-1 double mutant is slightly increased compared with the shd single mutant or the clv2-1 single mutant, which is a null allele of CLV2 (Jeong et al., 1999), but the phenotypic abnormality is not as severe as strong clv1 and clv3 phenotypes (Figure 5E and F). SAMs of this double mutant are more enlarged than those of each single mutant (data not shown). From these results, we could infer that the genes SHD, CLV1 and CLV3 work in the same pathway to control SAM and FM development, whereas SHD and CLV2 work in different pathways. However, the three CLV genes are known to function in the same pathway in the regulation of meristem development (Clark et al., 1995; Kayes and Clark, 1998) and it has been proposed that the three CLV proteins work as a complex (Brand et al., 2001; Clark, 2001). Further more, an enhancement of the clv2 mutant SAM phenotype is also observed in a double mutation between clv2 and weak or intermediate alleles of clv1 or clv3 (Kayes and Clark, 1998). Therefore, we conclude that SHD and all three CLV genes work in the same pathway to control SAM and FM development.

Fig. 5. Pistil phenotype of the shd clv double mutants. (A) Wild type (WS). (B) shd mutant. (C) clv1-4 mutant. (D) shd clv1-4 double mutant. (E) clv2-1 mutant. (F) shd clv2-1 double mutant. (G) clv3-1 mutant. (H) shd clv3-1 double mutant. All clv single mutants and shd clv double mutants indicated possess the erecta mutation. Front organs were removed to reveal the pistils. Bar: 1 mm.

The wus clv double mutant shows a phenotype indistinguishable from the wus single mutant in SAM and FM development, which is interpreted as the negative regulation of WUS by the CLV genes (Schoof et al., 2000). Because SHD and CLV act in the same pathway, we anticipated that the shd wus double mutant would resemble the wus single mutant. Cell division at the SAM of the shd wus-1 double mutant ceased after the formation of about five leaves, and the mutant grew some adventitious shoots that seldom formed immature flowers (Figure 6C and E). The entire morphology of the shd wus-1 double mutant was indistinguishable from that of the wus-1 single mutant.

Fig. 6. Effects of shd mutation upon phenotypes of the wus mutant and 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant. (A–E) Shoot and SAM phenotype of shd wus double mutant. (A) Main shoot of a shd adult plant. (B) Adventitious shoot of a wus-1 adult plant. (C) Adventitious shoot of a shd wus-1 adult plant, which is indistinguishable from wus-1 shoots (B). (D) SAM of a shd plant. The growing shoot apex of the main shoot (yellow arrow) is found in the rosette center. (E) Defective SAM of a shd wus-1 plant. The SAM of the main shoot is arrested (red arrow) and adventitious buds (yellow arrowheads) are growing. (F–K) Effect of shd mutation on CLV3 constitutive expression. (F) Adventitious shoots of a 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant. (G) Main and lateral shoots of a 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant harboring the shd mutation. The morphology is indistinguishable from that of the shd mutant. (H) Arrested SAM of a 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant (red arrow). (I) SAM of a 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant harboring the shd mutation. The growing shoot apex of the main shoot (yellow arrow) is found in the rosette center. (J) Flower of a 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant. Most of the stamens and all carpels are missing. (K) Flower of a 35S::CLV3 transgenic plant harboring the shd mutation. The phenotype is indistinguishable from shd mutant flowers. Flowers possessing five petals are sometimes observed in shd mutants, irrespective of the 35S::CLV3 transgene.

SHD is required for CLV function

Transgenic plants overexpressing CLV3 resemble the wus mutant, through apparent repression of WUS activity (Figure 6F, H and J) (Brand et al., 2000). However, this phenotype was abolished when the 35S::CLV3 transgene was introduced into clv1 or clv2 mutants, indicating that CLV3 signaling occurs exclusively through a CLV1/CLV2 receptor-kinase complex (Brand et al., 2000). From their structural features, nascent proteins of both CLV1 and CLV2 should be transported to the ER and assembled within the pathway from the ER to the plasma membrane where the CLV1/CLV2 complex is thought to be localized. CLV3 is a putative small secretory protein that should also be produced in the ER. Therefore, it seems likely that one or more of the CLV proteins may require SHD protein to assist in their folding and/or complex formation. To examine this possibility, we introduced the 35S::CLV3 gene into the shd mutant. If at least one of the CLV proteins requires SHD, the active CLV complex should no longer be formed and the effects of CLV3 overexpression should be abolished in these transformants. All 25 35S::CLV3 primary (T1) transformants in a wild-type background showed a wus phenocopy (Figure 6F, H and J). In contrast, the SAM and FM of all 25 T1 transformants possessing the 35S::CLV3 transgene in a shd background were enlarged, and the entire morphology of the transformants was indistinguishable from that of the shd mutant (Figure 6G, I and K). Thus, we conclude that the SHD protein is required for the correct folding and/or complex formation of CLV proteins.

shd affects the expression of CLV3 and WUS genes

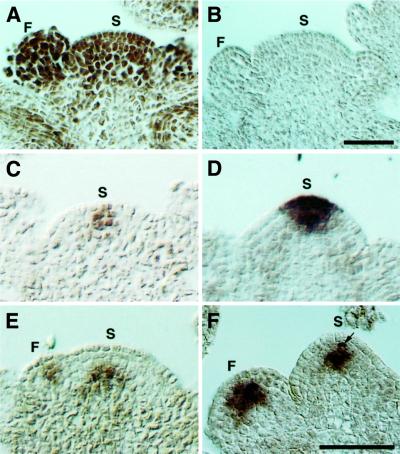

In situ hybridization was used to examine the expression pattern of SHD in the SAM and FM. SHD mRNA accumulated uniformly both in inflorescence SAM and in FM of wild-type Arabidopsis (Figure 7A). The signal was continuously detected after the floral organs were initiated, although it was slightly weakened.

Fig. 7. Expression pattern of SHD, CLV3 and WUS mRNA in the SAM and FM. (A) Wild-type (Ler) SAM and FM hybridized with an antisense SHD probe. SHD mRNA is distributed throughout the SAM and FM. (B) Wild-type SAM and FM hybridized with a sense SHD probe. (C) Wild-type SAM hybridized with an antisense CLV3 probe. CLV3 mRNA is localized in a few cells at the SAM. (D) shd SAM hybridized with an antisense CLV3 probe. The CLV3 expression domain is enlarged compared with the wild type (C). (E) Wild-type SAM and FM hybridized with an antisense WUS probe. WUS mRNA is detected in a small group of cells both in the SAM and FM. In the SAM, the WUS expressing cells localize underneath the three outermost cell layers. (F) shd SAM and FM hybridized with an antisense WUS probe. The WUS expression domains are enlarged both in the SAM and FM, and WUS mRNA is detected even in the third layer of the SAM, i.e. one cell layer up compared with the wild type (E). In this panel, a second-layer cell (arrow) in the SAM is also stained. (A) and (B) are the same magnifications, and (C–F) are the same magnifications. Bar: 50 µm. S, SAM; F, FM.

In clv mutants, the enlargement of the SAM and FM is due to central-zone expansion. To examine whether this is also true of the SAM and FM of shd mutants, we carried out in situ hybridization with a CLV3 probe, which is a molecular marker for stem cells (Fletcher et al., 1999). As expected, the expression domain of the CLV3 gene was markedly expanded in the SAM of this mutant, relative to the wild type (Figure 7C and D). Similar expansion was observed in the shd FM (data not shown).

In the SAM of wild-type plants, it was reported that WUS is expressed in a small group of cells in the center of the meristem, underneath the three outermost cell layers (Schoof et al., 2000). In the SAM of clv mutants, the WUS expression domain is broader than it is in the wild-type plants, and is shifted to the third and fourth cell layers from the surface, i.e. one cell layer up, as compared with the wild type (Schoof et al., 2000). From these results, it was inferred that CLV genes negatively regulate the WUS gene at the transcriptional level. In the shd mutant, WUS is expressed in the third and fourth layers of the SAM, and the number of WUS-expressing cells is increased (Figure 7E and F), which is quite similar to the observation in the SAM of clv mutants. The WUS expression domain is also expanded in the FM of shd mutant plants. These results demonstrating the altered expression of WUS in the shd mutant are consistent with the requirement for the SHD gene for CLV activity.

Discussion

In this paper, we have analyzed the pleiotropic effects of the shd mutation, namely expansion of SAM and FM, disorganized cell arrangement in RAM, and inhibition of pollen tube elongation into the style. SHD appears to encode the only ortholog of GRP94 in Arabidopsis. Since the shd mutation described here is a null allele, the phenotype of this mutant most likely reflects the range of target proteins that essentially require the SHD protein for folding or complex formation.

SHD function in the SAM and FM

To determine how SHD protein is involved in the regulation of SAM and FM homeostasis, we analyzed the genetic interactions between the SHD, CLV and WUS genes, since the SAM and FM phenotype of shd closely resembles those of the clv mutants. The phenotypes of the shd clv and shd wus double mutants strongly suggest that SHD and CLV act in the same pathway to repress the WUS gene. Our in situ hybridization data, in which both WUS and CLV3 genes were upregulated in the shd SAM, support the above hypothesis. It is noteworthy that the effects of CLV3 overexpression were abolished in the shd mutant background. This result, together with genetic evidence that the wus mutation is epistatic to the shd and clv mutations, indicates that the SHD gene is required for CLV function to suppress WUS gene expression. Although the signal transduction pathway between the active CLV complex and WUS gene transcription has not been identified, the involvement of proteins such as KAPP and ROP are predicted (Trotochaud et al., 1999; Brand et al., 2001; Clark, 2001). However, the subcellular localization of these proteins is the cytosol, which is separated from the ER. Therefore, it is unlikely that ER-resident SHD interacts with these other components of CLV signal transduction. It is most likely that SHD protein is necessary for the correct folding and/or complex formation of nascent CLV proteins in the ER. This is the first identification of the target protein(s) of GRP94 in plants that require GRP94 function, even under non-stress conditions.

SHD has specialized functions in multicellular organisms

The SHD gene is expressed in many organs of the plant body, since SHD mRNA was detected in all organs examined, including flowers, shoot apex, mature leaves and roots. Indeed, several phenotypes other than SAM and FM expansion were observed, including disorganization of the RAM and inhibition of pollen tube elongation. However, the mutation is not lethal and the mutant plant is healthy under normal growth conditions, strongly suggesting that the requirement for SHD protein is restricted, at least in non-stress conditions. It is interesting that the GRP94 has not yet been identified in a unicellular eukaryote (Lee, 2001), whereas other ER-resident molecular chaperones, such as a GRP78 (Kar2p) and a protein disulfide isomerase (Pdi1p) are essential for cell growth in yeast (Normington et al., 1989; Rose et al., 1989; Tachikawa et al., 1991). One possibility is that SHD is not necessary for cell growth itself but may, for example, be required for making functional proteins involved in cell–cell communication, which is required for the development of multicellular organisms. Indeed, in Arabidopsis, CLV proteins are involved precisely in cell–cell signaling in the SAM and FM tissues, and root cell organization and pollen tube elongation may also be highly dependent on cell–cell communication. Receptor kinases resembling CLV1 and CLV2 (encoded in the Arabidopsis genome as multigene families) and a putative ligand peptide resembling CLV3 may be candidates for the SHD target proteins in the RAM and pollen grains (Bisseling, 1999; Torii, 2000; Cock and McCormick, 2001). The limited requirement for SHD protein is consistent with the relatively narrow range of the target proteins of cytosolic HSP90 in animals (Pratt, 1997; Buchner et al., 1999; Mayer and Bukau, 1999), although the loss-of-function mutant of Drosophila HSP90 is lethal (Cutforth et al., 1994). In addition, the pleiotropic phenotype of the shd mutant can be interpreted as the result of the accumulation of ‘cryptic mutations’ in the Arabidopsis genome, which are corrected by the chaperone functions of SHD protein. Thus our finding seems to be an example of the theory of Rutherford and Lindquist in plants, in which HSP90 allows the cryptic mutations to accumulate in order to promote morphological evolution (Rutherford and Lindquist, 1998).

SHD requirement at high temperature

The extent of the defects in shd mutant is highly dependent on growth temperature, i.e. shd plants growing at higher temperatures show more severe defects. Since the shd mutation is a null allele, this temperature dependency does not reflect the stability of SHD protein, but indicates the extent of its requirement. It should be noted that no novel phenotypes were observed at higher temperatures, although the severity of the defects was increased. Therefore, the spectrum of proteins required for SHD function does not vary in relation to the growth temperature, but, rather, the structural defects of SHD target proteins increase at higher temperatures.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The shd mutant was identified in screens of T-DNA-transformed wild-type Wassilewskija (WS) plants. The dad1 mutant from WS has been described (Ishiguro et al., 2001). The clv1-4 and clv3-1 mutants have been described previously (Clark et al., 1993, 1995) and were kindly provided by Elliot M.Meyerowitz. The clv2-1 mutant (Koornneef et al., 1983; Kayes and Clark, 1998) was obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) at Ohio State University. The wus-1 mutant (Laux et al., 1996) was kindly provided by Thomas Laux. All clv and wus alleles were induced in the Landsberg erecta (Ler) ecotype. The WS ecotype was used as the wild-type, except for in situ hybridization experiments where the Ler ecotype was used. Plants were grown at 22°C under continuous illumination.

Microscopy

For observation of fifth-whorl gynoecia, pistils were fixed for 12 h in ethanol:acetic acid (9:1, v:v) at 4°C. After serial washing with 70, 50 and 30% ethanol, samples were cleared with chloral hydrate:glycerol:water (8:1:2, w:v:v). Cleared pistils were viewed with Nomarski optics. To examine cell organization in the RAM, roots of 7-day-old seedlings grown on agar plates (Okada and Shimura, 1992) were stained with 10 µg/ml propidium iodide solution and observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM410, Carl Zeiss). Roots were stained for starch as described previously (Fukaki et al., 1998). Pollinated pistils were stained with aniline blue as described (Ishiguro et al., 2001).

Scanning electron microscopy

Flowers and inflorescence tips were fixed in isoamyl acetate:ethanol (1:3, v:v) overnight at room temperature. The samples were then treated sequentially in fresh isoamyl acetate:ethanol (1:3) solution, isoamyl acetate:ethanol (1:1) and isoamyl acetate for 15 min each, and were dried with a critical point drier (JCPD-5, JEOL). After removal of obstructive organs, the samples were coated with osmium tetroxide by a plasma multi-coater (PMC-5000, Meiwa Shoji) and observed with a scanning electron microscope (JSM-5800, JEOL).

Molecular cloning of the SHD gene

To identify the genomic sequences flanking the T-DNA, we performed thermal asymmetric interlaced (TAIL) PCR (Liu et al., 1995). A 0.6 kb fragment and a 1.4 kb fragment were amplified from the right and left borders of the T-DNA, respectively. To confirm the cosegregation of the shd mutation and the T-DNA insertion, PCR amplification was performed with genomic DNA from F2 plants showing the shd phenotype, by using the three primers: L12-LCF1 (5′-GGCAAATCATGACGAAGCTA ACC-3′), L12-LCR1 (5′-GACATCGACTCAGACTCTCTGTC-3′) and PL1 (5′-TTTCGCCTGCTGGGGCAAACCAG-3′) for each reaction. A 0.5 kb fragment and a 0.3 kb fragment were amplified from SHD and shd alleles, respectively.

A full-length cDNA clone was obtained from the ABRC as EST clone 177P12T7, the 5′ end of which is indicated with an asterisk in Figure 4A.

Subcellular localization was examined using TargetP v1.01 at the Center for Biological Sequence Analysis (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/ services/TargetP/) and the PSORT www Server at the National Institute for Basic Biology (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp).

Complementation experiment

The 6.7 kb XhoI–EcoRI fragment, corresponding to nucleotides 1–6679 of SHD gene (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AB064527) was subcloned into the BamHI site of the binary vector pARK5-MCS, and introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (pGV2260). Trans formation of the shd mutant was carried out by a tissue culture method using 10 mg/l bialaphos to select for transformants (Akama et al., 1992). The binary vector pARK5 and the bialaphos were kindly provided by Hiroyuki Anzai.

Examination of SHD gene expression

Total RNA isolated by using Isogen reagent (Nippon Gene) was separated on a 1% agarose/formaldehyde denaturing gel, transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia) and probed with SHD cDNA. To assess heat induction, 19-day-old seedlings on agar plates were incubated in air incubators at 22°C or 40°C for 2 h. After treatment, rosette leaves were harvested and used for RNA preparation. A 1.1 kb EcoRI fragment of an HSP81-1 genomic clone (Takahashi et al., 1992) was kindly provided by Taku Takahashi and used as a probe for detecting the transcripts of the four HSP81 genes (HSP81-1 to HSP81-4).

Overexpression of CLV3

A CLV3 cDNA was prepared by RT–PCR using flower bud RNA and two PCR primers (CLV3F-Xba, 5′-CTCTCTAGAAAATGGATTCTAAAAGCTTTGTGCTAC-3′; CLV3R-Sac, 5′-TTAGAGCTCCAAGAGATTAGGTCAAGGGAGCTGA-3′) and cloned between XbaI and SacI sites of pIG221 plasmid (Ohta et al., 1990). Then the fragment including cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, CLV3 cDNA and nos terminator was subcloned onto pPZP221 vector. Transformation of wild-type WS and shd mutant was carried out by the vacuum infiltration method (Bechtold et al., 1993).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was carried out as described (Long and Barton, 1998). The SHD antisense and sense probes were prepared from the subclone of an EcoT14 I fragment corresponding to nucleotides 1906–2500 of the SHD cDNA (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AB064528). The CLV3 antisense probe was transcribed from the CLV3 cDNA clone described above. The WUS antisense probe has been described previously (Kaya et al., 2001) and was kindly provided by Hidetaka Kaya and Takashi Araki.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Keiko U.Torii, Ken Matsuoka, Ryuichi Nishihama, Ikuko Hara-Nishimura, Maki Kondo, Mikio Nishimura, Steven E.Clark, Elliot M.Meyerowitz, Thomas Laux, Hiroyuki Anzai, Taku Takahashi, Hidetaka Kaya, Takashi Araki, Ayumi Tanaka, Yoshibumi Komeda, Kokichi Hinata, Yasunori Machida, Yoshiro Shimura and all the members of the Okada laboratory, especially Ryuji Tsugeki, Toshiro Ito and Noritaka Matsumoto, for materials, helpful discussions and technical advice. We also thank Rie Ishiguro for invaluable technical assistance. We acknowledge the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center at Ohio State University for providing EST-clones and seed. This work was funded by the ‘Research for the Future’ Program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to S.I.; and supported by Grants-in-Aid for Special Research on Priority Areas [(No. 07281101 to S.I.) and No. 10182101 to K.O.)] and by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology (to S.I. and K.O.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. This work was also funded by the Research Institute of Seed Production to S.I. and from the Mitsubishi Foundation to K.O.

References

- Aeschbacher R.A., Schiefelbein,J.W. and Benfey,P.N. (1994) The genetic and molecular basis of root development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol., 45, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Akama K., Shiraishi,H., Ohta,S., Nakamura,K., Okada,K. and Shimura,Y. (1992) Efficient transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana: comparison of the efficiencies with various organs, plant ecotypes and Agrobacterium strains. Plant Cell Reports, 12, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argon Y. and Simen,B.B. (1999) GRP94, an ER chaperone with protein and peptide binding properties. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol., 10, 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N., Ellis,J. and Pelletier,G. (1993). In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C.R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Life Sciences, 316, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Bisseling T. (1999) The role of plant peptides in intercellular signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 2, 365–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand U., Fletcher,J.C., Hobe,M., Meyerowitz,E.M. and Simon,R. (2000) Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science, 289, 617–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand U., Hobe,M. and Simon,R. (2001) Functional domains in plant shoot meristems. BioEssays, 23, 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner J. (1999) Hsp90 & Co.—a holding for folding. Trends Biochem. Sci., 24, 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.E. (2001) Cell signalling at the shoot meristem. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 2, 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.E., Running,M.P. and Meyerowitz,E.M. (1993) CLAVATA1, a regulator of meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Development, 119, 397–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.E., Running,M.P. and Meyerowitz,E.M. (1995) CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development, 121, 2057–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S.E., Williams,R.W. and Meyerowitz,E.M. (1997) The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell, 89, 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock J.M. and McCormick,S. (2001) A large family of genes that share homology with CLAVATA3. Plant Physiol., 126, 939–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutforth T. and Rubin,G.M. (1994) Mutations in Hsp83 and cdc37 impair signaling by the sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase in Drosophila. Cell, 77, 1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner P. (2000) Plant stem cells: the only constant thing is change. Curr. Biol., 10, R826–R829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J.C., Brand,U., Running,M.P., Simon,R. and Meyerowitz,E.M. (1999) Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science, 283, 1911–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukaki H., Wysocka-Diller,J., Kato,T., Fujisawa,H., Benfey,P.N. and Tasaka,M. (1998) Genetic evidence that the endodermis is essential for shoot gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J., 14, 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M.J. and Sambrook,J. (1992) Protein folding in the cell. Nature, 355, 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S., Kawai-Oda,A., Ueda,J., Nishida,I. and Okada,K. (2001) The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCENCE 1 gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 13, 2191–2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S., Trotochaud,A.E. and Clark,S.E. (1999) The Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein required for the stability of the CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell, 11, 1925–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R.J. (1999) Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev., 13, 1211–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H., Shibahara,K.I., Taoka,K.I., Iwabuchi,M., Stillman,B. and Araki,T. (2001) FASCIATA genes for chromatin assembly factor-1 in Arabidopsis maintain the cellular organization of apical meristems. Cell, 104, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayes J.M. and Clark,S.E. (1998) CLAVATA2, a regulator of meristem and organ development in Arabidopsis. Development, 125, 3843–3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G.L.E. (1987) Reticuloplasmins: a novel group of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci., 87, 491–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M., van Eden,J., Hanhart,C.J., Stam,P., Braaksma,F.J. and Feensra,W.J. (1983) Linkage map of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Hered., 74, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P. and Gloor,G. (2001) The Hsp90 family of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Stress Chaperones, 6, 238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs P., Grandjean,O., Jonak,C., Kiêu,K. and Traas,J. (1998) Cellular parameters of the shoot apical meristem in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 10, 1375–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux T., Mayer,K.F., Berger,J. and Jürgens,G. (1996) The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development, 122, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.S. (1987) Coordinated regulation of a set of genes by glucose and calcium ionophores in mammalian cells. Trends Biochem. Sci., 12, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.S. (2001) The glucose-regulated proteins: stress induction and clinical applications. Trends Biochem. Sci., 26, 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.G., Mitsukawa,N., Oosumi,T. and Whittier,R.F. (1995) Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junctions by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J., 8, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J.A. and Barton,M.K. (1998) The development of apical embryonic pattern in Arabidopsis. Development, 125, 3027–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macer D.R. and Koch,G.L.E. (1988) Identification of a set of calcium-binding proteins in reticuloplasm, the luminal content of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci., 91, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K.F.X., Schoof,H., Haecker,A., Lenhard,M., Jürgens,G. and Laux,T. (1998) Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell, 95, 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M.P. and Bukau,B. (1999) Molecular chaperones: the busy life of Hsp90. Curr. Biol., 9, R322–R325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick J., Dul,J.L. and Argon,Y. (1994) Sequential interaction of the chaperones BiP and GRP94 with immunoglobulin chains in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature, 370, 373–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicchitta C.V. (1998) Biochemical, cell biological and immunological issues surrounding the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone GRP94/gp96. Curr. Opin. Immunol., 10, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normington K., Kohno,K., Kozutsumi,Y., Gething,M.J. and Sambrook,J. (1989) S. cerevisiae encodes an essential protein homologous in sequence and function to mammalian BiP. Cell, 57, 1223–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S., Mita,S., Hattori,T. and Nakamura,K. (1990) Construction and expression in tobacco of a β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene containing an intron within the coding sequence. Plant Cell Physiol., 31, 805–813. [Google Scholar]

- Okada K. and Shimura,Y. (1992) Mutational analysis of root gravitropism and phototropism of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Aust. J. Plant Physiol., 19, 439–448. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt W.B. (1997) The role of the hsp90-based chaperone system in signal transduction by nuclear receptors and receptors signaling via MAP kinase. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 37, 297–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M.D., Misra,L.M. and Vogel,J.P. (1989) KAR2, a karyogamy gene, is the yeast homolog of the mammalian BiP/GRP78 gene. Cell, 57, 1211–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Running M.P. and Hake,S. (2001) The role of floral meristems in patterning. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 4, 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford S.L. and Lindquist,S. (1998) Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature, 396, 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoof H., Lenhard,M., Haecker,A., Mayer,K.F.X., Jürgens,G. and Laux,T. (2000) The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems is maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell, 100, 635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder G., Beck,M., Eichel,J., Vetter,H.-P. and Schröder,J. (1993) HSP90 homologue from Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus): cDNA sequence, regulation of protein expression and location in the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Mol. Biol., 23, 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachikawa H., Miura,T., Katakura,Y. and Mizunaga,T. (1991) Molecular structure of a yeast gene, PDI1, encoding protein disulfide isomerase that is essential for cell growth. J. Biochem. (Tokyo), 110, 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Naito,S. and Komeda,Y. (1992) Isolation and analysis of the expression of two genes for the 81-kilodalton heat-shock proteins from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol., 99, 383–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii K.U. (2000) Receptor kinase activation and signal transduction in plants: an emerging picture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol., 3, 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud A.E., Hao,T., Wu,G., Yang,Z. and Clark,S.E. (1999) The CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase requires CLAVATA3 for its assembly into a signaling complex that includes KAPP and a Rho-related protein. Plant Cell, 11, 393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud A.E., Jeong,S. and Clark,S.E. (2000) CLAVATA3, a multimeric ligand for the CLAVATA1 receptor-kinase. Science, 289, 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg C., Weisbeek,P. and Scheres,B. (1998) Cell fate and cell differentiation status in the Arabidopsis root. Planta, 205, 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites R. and Simon,R. (2000) Signaling cell fate in plant meristem. Three clubs on one tousle. Cell, 103, 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther-Larsen H., Brandt,J., Collinge,D.B. and Thordal-Christensen,H. (1993) A pathogen-induced gene of barley encodes a HSP90 homologue showing striking similarity to vertebrate forms resident in the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Mol. Biol., 21, 1097–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe N., Takahashi,T. and Komeda,Y. (1994) Analysis of tissue-specific expression of Arabidopsis thaliana HSP90-family gene HSP81. Plant Cell Physiol., 35, 1207–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Haze,K., Yanagi,H., Yura,T. and Mori,K. (1998) Identification of the cis-acting endoplasmic reticulum stress response element responsible for transcriptional induction of mammalian glucose-regulated proteins. Involvement of basic leucine zipper transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 33741–33749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]