Abstract

The Aspergillus PacC transcription factor undergoes proteolytic activation in response to alkaline ambient pH. In acidic environments, the 674 residue translation product adopts a ‘closed’ conformation, protected from activation through intramolecular interactions involving the ≤150 residue C-terminal domain. pH signalling converts PacC to an accessible conformation enabling processing cleavage within residues 252–254. We demonstrate that activation of PacC requires two sequential proteolytic steps. First, the ‘closed’ translation product is converted to an accessible, committed intermediate by proteolytic elimination of the C-terminus. This ambient pH-regulated cleavage is required for the final, pH-independent processing reaction and is mediated by a distinct signalling protease (possibly PalB). The signalling protease cleaves PacC between residues 493 and 500, within a conserved 24 residue ‘signalling protease box’. Precise deletion or Leu498Ser substitution prevents formation of the committed and processed forms, demonstrating that signalling cleavage is essential for final processing. In contrast, signalling cleavage is not required for processing of the Leu340Ser protein, which lacks interactions preventing processing. In its two-step mechanism, PacC processing can be compared with regulated intramembrane proteolysis.

Keywords: PacC/proteolytic processing/signal transduction/transcription factor

Introduction

A number of transcription factors are synthesized as inactive precursors, which are activated by proteolytic processing in response to appropriate environmental signals. A subgroup, typified by NF-κB p105 (Ghosh et al., 1998) or yeast SPT23 and MGA2 (Hoppe et al., 2000), includes proteins which are substrates of limited proteolysis mediated by the proteasome. A second subgroup, typified by SREBP, undergoes regulated intra membrane proteolysis (Rip) (Brown and Goldstein, 1999; Brown et al., 2000). In Rip, a regulated primary cleavage that takes place outside the lipid bilayer is a prerequisite for a second intramembrane cleavage of a transmembrane protein. A third subgroup includes Drosophila Cubitus interruptus (Ci, the transducer of the Hedgehog signal; Ingham, 1998) and Aspergillus PacC (mediating pH regulation of gene expression; Tilburn et al., 1995). Members of this third subgroup share features of their zinc finger DNA-binding domains, and their respective processing proteases have unusual specificities in that their action does not appear to require the region encompassing the processing site (Methot and Basler, 1999; Mingot et al., 1999). This subgroup also includes the GLI metazoan homologues of Ci, which are key regulatory factors in development (Ruiz i Altaba, 1999). We address here the mechanisms underlying the proteolytic activation of PacC by exploiting the ease with which the lower eukaryote Aspergillus nidulans can be manipulated genetically.

The 674 residue zinc finger protein PacC (Figure 1A) is activated by limited proteolysis in response to the alkaline ambient pH signal, which is transmitted to the transcription factor via the six pal gene signal transduction pathway (Orejas et al., 1995; Mingot et al., 1999). The processed factor (the 248–250 N-terminal residues) localizes to the nucleus (Mingot et al., 2001) where it activates transcription of genes preferentially expressed under alkaline conditions and represses transcription of genes preferentially expressed under acidic conditions, in both cases through 5′-GCCARG-3′ sites in the promoters of the target genes (Tilburn et al., 1995; Espeso and Peñalva, 1996; Espeso et al., 1997; Espeso and Arst, 2000). Mutational inactivation of genes in the pal pathway (palA, B, C, F, H and I) or the pacC gene itself (pacC– and pacC+/– mutations) leads to an acidity-mimicking phenotype; gain-of-function pacCc mutations bypassing the need for the ambient pH signal lead to alkalinity mimicry (Caddick et al., 1986; Arst et al., 1994; Denison et al., 1995, 1998; Orejas et al., 1995; Tilburn et al., 1995; Negrete-Urtasun et al., 1997, 1999).

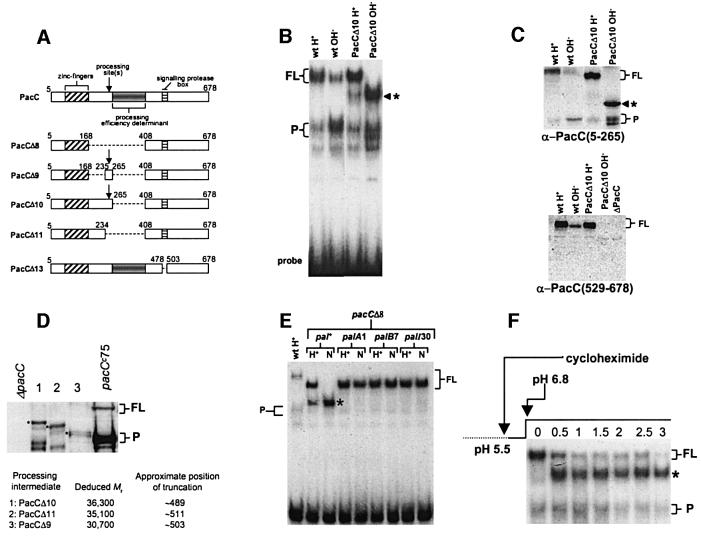

Fig. 1. (A) Schematic representation of PacC deletion mutations used in this work. To avoid confusion with earlier publications, numbering indicates amino acid positions on the basis of 678 residues, although translation starts at codon 5 (Mingot et al., 1999). (B) A processing intermediate is detected with PacCΔ10. EMSA shows PacC–DNA complexes corresponding to the different PacC forms. Strains and growth conditions are indicated. Here, and in all other panels, an asterisk indicates the processing intermediate; FL and P indicate full-length and processed form complexes, respectively. (C) Western blot analysis of protein extracts used in (B). Proteins were detected with the indicated antisera. The anti-PacC(529–678) antiserum was raised against the C-terminal PacC domain. (D) Deducing the approximate C-terminal residue of the processing intermediate. Protein extracts corresponding to the indicated mutant proteins were analysed by western blot with α-PacC(5–265) antiserum. The deduced molecular weight of the intermediates was used to estimate the approximate position of their C-terminal truncations. The pacCc75 translation product (Mr 45 478) was used as internal standard. (E) pH and pal dependence of the formation of the processing intermediate in pacCΔ8 strains. Protein extracts from acidic (H+) and neutral (N) growth conditions were analysed by EMSA. Neutral (pH 6.8) conditions leading to pH signalling were used as strains carrying palA1 or palB7 loss-of-function mutations do not grow at alkaline pH, and palI30 mutants grow poorly. (F) The translation product of PacCΔ10 and the processing intermediate show a precursor–product relationship. The relevant portion of an EMSA gel showing conversion of the PacCΔ10 translation product to the processing intermediate. Cells were grown under acidic conditions, incubated in the presence of cycloheximide for 30 min and shifted to neutral conditions also in the presence of cycloheximide. Numbers indicate hours after the pH shift.

The ambient pH signal regulates the accessibility of PacC to the processing protease. Upon translation, PacC adopts a ‘closed’ conformation, held together by the interaction of a C-terminal domain (interacting domain C, located within residues 529–678) with two domains upstream, which prevents processing under inappropriate circumstances (i.e. at acidic pH, resulting in the absence of pal signalling) (Espeso et al., 2000). When the pH signal is received (i.e. at alkaline ambient pH), the protein shifts to an ‘open’ (protease-accessible) conformation (Espeso et al., 2000). The mutant pacC+/–20205 product is deficient in the pH signal response and behaves as if locked in the ‘closed’ conformation. Single residue mutations, typified by pacCc69 (L340S), or pacCc truncating mutations removing the C-terminal <150 residue interacting domain C disorganize the ‘closed’ conformation, permitting the access of the protease to its target peptide bond(s) under any pH conditions (Espeso et al., 2000). These mutations lead to processing irrespective of ambient pH, which explains their alkalinity mimicry.

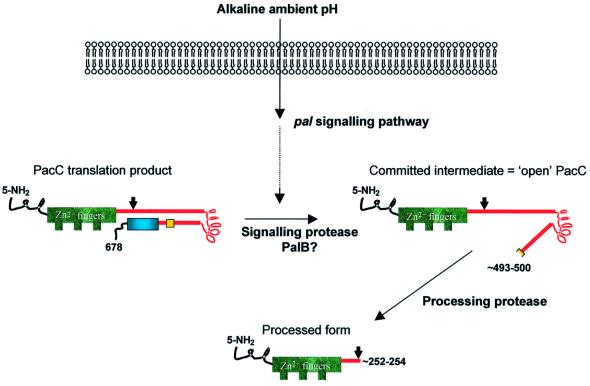

Evidence described in the following sections strongly supports a model in which the proteolytic processing activation of PacC takes place in two steps. In a first step, which is crucially regulated by ambient pH and requires the pal signalling pathway, including a signalling protease, the translation product is converted to a processing intermediate by proteolytic cleavage of the translation product after residues ∼493–500, within a conserved ‘signalling protease box’ (Figure 1A). This intermediate corresponds to the previously designated ‘open’ PacC form, lacks interacting region C (residues 529–678) and is committed to subsequent cleavage at residue(s) ∼252–254 by the processing protease, which, in contrast to the signalling protease, acts independently of ambient pH signalling (Mingot et al., 1999). This two-step mechanism is comparable with the two-step mechanism of Rip (Brown et al., 2000).

Results

Deletion of a processing protease efficiency determinant reveals an intermediate in PacC proteolytic activation

PacC C-terminal deletion analysis showed that residues 266–407, immediately downstream of the processing site (at residues ∼252–254), are required for efficient processing (Mingot et al., 1999). In agreement, PacCΔ10, a mutant PacC precisely deleted for this region (Figure 1A), showed accurate but inefficient processing under alkaline conditions, revealing a putative intermediate in the conversion of full-length PacC to the processed form (Figure 1B and C). This new PacC-derived polypeptide, intermediate in size between the mutant full-length and processed forms, is barely visible under acidic conditions but predominates under alkaline conditions, apparently accumulating at the expense of the primary translation product. This polypeptide results from endoproteolysis in the C-terminal region of PacC, as it lacks C-terminal epitopes (Figure 1C).

That this polypeptide is a true intermediate in the processing of PacC is supported by the following. First, intermediates, whose sizes are commensurate with the extents of the respective deletions, accumulated under alkaline conditions with PacCΔ8 (data not shown), PacCΔ9 and PacCΔ11, proteins sharing with PacCΔ10 a deletion of the 266–407 processing efficiency determinant (Figure 1D). We used the electrophoretic mobility of the mutant intermediates in western blots (with the exception of the PacCΔ8 intermediate, which is recognized inefficiently by the polyclonal antiserum used) to deduce the approximate position of the predicted cleavage between PacC residues 489 and 511 (Figure 1D). This strongly suggests that the different intermediates corresponding to the three different mutant PacC proteins result from cleavage at the same residue. Secondly, the PacCΔ8 protein, which is fully deficient in processing due to deletion of residues 169–407, is converted exclusively to the intermediate in response to pH signalling (Figure 1E). Thirdly, this conversion depends on the integrity of the pal signalling pathway (Figure 1E; also demonstrated for PacCΔ10 in double mutants with palA–, palB–, palF– and palI– alleles, data not shown). Fourthly, the translation product and the intermediate show a precursor–product relationship. pacCΔ10 mycelia were grown under acidic conditions and, after addition of a protein synthesis inhibitor, transferred to pH 6.8 medium (i.e. leading to pal signalling). Within 0.5 h under pal pathway-activating pH conditions, most of the translation product, strongly predominating at the time of the transfer, was converted to the intermediate (Figure 1F). This finding was confirmed using transient expression of PacCΔ10 under the control of the alcA promoter, following Mingot et al. (1999) (data not shown).

We concluded that the intermediate revealed with mutant proteins fully or partially deficient in processing would be the actual substrate of the processing protease. This intermediate is committed to processing, as it lacks the C-terminal interacting region C (within residues 529–678). The cleavage yielding this intermediate is pH dependent and requires the pal signalling pathway, including a signalling protease. As shown below, this signalling protease does not require the same sequence specificity and efficiency determinants in PacC as the processing protease, which, in contrast to the signalling protease, acts independently of ambient pH signalling (Denison et al., 1995; Orejas et al., 1995; Mingot et al., 1999).

The ‘open’ form of PacC lacks C-terminal sequences of the translation product

In view of the evidence for the existence of a processing intermediate lacking interacting region C, we looked for this intermediate in the wild-type. An obvious candidate was the ‘open’ PacC form described by Espeso et al. (2000). The unprocessed pacC product consists of ‘open’ and ‘closed’ forms. ‘Open’ PacC is defined as that unprocessed product whose corresponding protein– DNA complex can be supershifted in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) by GST::PacC(410–678) fusion protein (Figure 2A). The ‘open’ form conformation is such that interacting regions A and B are available for contacts with interacting region C provided by the GST fusion protein (Espeso et al., 2000).

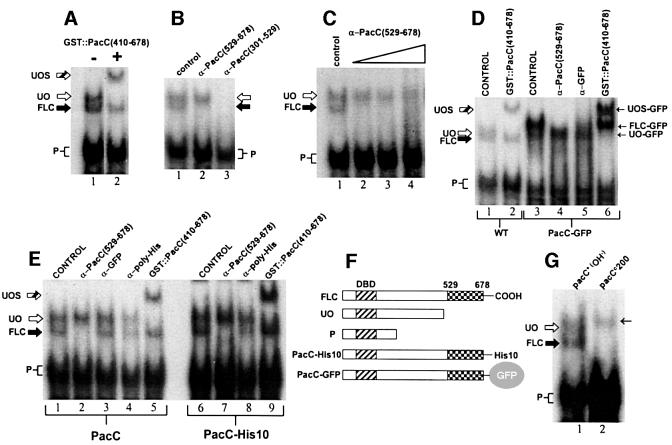

Fig. 2. The ‘open’ form of PacC lacks C-terminal residues. (A) Electrophoretic separation of protein–DNA complexes corresponding to the ‘open’ (UO) and full-length ‘closed’ (FLC) unprocessed forms of PacC. Only the ‘open’ form complex is supershifted (UOS, striped arrow) by addition of a PacC polypeptide containing interacting region C. P, processed form. (B) Inclusion of an antiserum raised against PacC residues 529–678 removes the ‘closed’ complex but not the ‘open’ complex, whereas an antiserum raised against PacC residues 301–529 removes both. (C) Excess α-PacC(529–678) antiserum does not interfere with the ‘open’ PacC complex. A 2, 4 or 6 µl aliquot of antiserum was added in the indicated samples. Control indicates no addition. (D) A C-terminal GFP tag is absent from ‘open’ PacC. ‘Open’ and ‘closed’ complexes of PacC(5–678)::GFP (see F) were resolved by EMSA. The ‘open’ PacC::GFP complex (UO-GFP), that is supershifted by addition of purified GST::PacC(410–678) (UOS-GFP, lane 6), is recognized neither by α-GFP antiserum nor by α-PacC(529–678) antiserum (see text), indicating that the tag has been removed together with C-terminal PacC epitopes. In contrast, the ‘closed’ PacC::GFP complex [FLC-GFP, not supershifted by GST::PacC(410–678), lane 6] is recognized by both antisera. Lane 1 shows the positions of the ‘open’ untagged PacC complex (UO), supershifted by GST::PacC(410–678), and the ‘closed’ untagged PacC complex (FLC). The mobilities of the ‘open’ form complexes of GFP-tagged and untagged PacC are equal, showing that both result from an endoproteolytic cleavage in the C-terminal region of PacC. (E) ‘Closed’ and ‘open’ form complexes of PacC tagged with His10 at the C-terminus. The ‘closed’ complex is recognized by either an α-PacC(529–678) or an α-poly-His antiserum, whereas neither recognizes the ‘open’ form complex, indicating that both the tag and C-terminal PacC sequences have been removed from the latter. (F) Schematic representation of the proteins used in the experiments shown in (A–E). (G) The mobility of the pacCc200 full-length protein (residues 5–578 plus threonine) complex (thin arrow) is markedly less than that of the wild-type ‘closed’ form complex and slightly less than that of the ‘open’ form complex.

In high-resolution EMSA, the ‘closed’ form complex shows a slightly greater mobility than the ‘open’ form complex (Figure 2A; Mingot et al., 2001). Inclusion of various anti-PacC antisera in the EMSA mixture specifically sequesters those protein–DNA complexes containing epitopes recognized by the antibodies. Figure 2B shows that both the slower (‘open’) and the faster (‘closed’) unprocessed PacC complexes (but not the pro cessed form complex) are removed by anti-PacC(301– 529) antiserum. In contrast, only the PacC form present in the faster unprocessed complex is recognized by anti- PacC(529–678) antiserum, even at high doses (Figure 2C). Therefore, the ∼150 C-terminal residues in the ‘open’ form are either inaccessible to the antibodies (which would be inconsistent with its ‘open’ conformation) or were removed from the protein on reception of the ambient pH signal.

To exclude artefacts resulting from possible differences in epitope accessibility, we tagged PacC with green fluorescent protein (GFP) or His10 after residue 678. Two complexes containing unprocessed forms were detected with a PacC::GFP protein extract, of which that with the greater mobility corresponds to ‘open’ PacC, as shown by its supershift in the presence of GST:: PacC(410–678) (Figure 2D, lanes 3 and 6). Note that, in contrast to the situation with untagged PacC, the PacC::GFP ‘open’ form complex has greater mobility than the ‘closed’ form complex as the marked loss of mobility caused by the 27 kDa GFP tag is greater than that resulting from the conversion of the ‘closed’ to the ‘open’ form, reversing the relative mobilities of the ‘open’ and ‘closed’ complexes. The ‘open’ PacC complex is resistant to anti-GFP antiserum, in contrast to the slower mobility ‘closed’ complex, which is sensitive both to this antiserum and to anti-PacC(529–678) (Figure 2D, lanes 4 and 5). Moreover, the mobility of the ‘open’ complex corresponding to PacC(5–678)::GFP is indistinguishable from that of ‘open’ untagged PacC (Figure 2D, lanes 1 and 3), showing that the GFP tag has been removed. We conclude that the ‘open’ PacC form is the product of an endoproteo lytic cleavage removing C-terminal residues from the primary translation product. This conclusion was confirmed further with C-terminally His-tagged PacC. Only the ‘closed’ form complex [i.e. that not supershifted by GFP::PacC(410–678)] (Figure 2E, lanes 6 and 9) was sensitive to anti-poly-His and anti-PacC(529–678) antisera (Figure 2E, lanes 7 and 8). The absence of C-terminal sequences in ‘open’ PacC agrees with our interpretation that this species corresponds to the processing intermediate.

These results provide an additional way to define the ‘open’ PacC form as the proportion of unprocessed PacC not recognized by α-PacC(529–678). The antiserum/EMSA assay was used with truncated proteins in a preliminary determination of the extent of the C-terminal truncation in the ‘open’ form. The pacCc200 translation product (residues 5–578 plus threonine) is recognized by this antiserum, in contrast to the mutant pacCc11 translation product (residues 5–540), which is not (data not shown). This shows that the C-terminus of ‘open’ PacC is, at a minimum, upstream of residue 578, 100 residues upstream from the C-terminus of the wild-type translation product.

pacCc200 is a strong alkalinity-mimicking mutation disrupting interacting region C. Therefore, its translation product is not protected from the processing protease by intramolecular interactions (Espeso et al., 2000) and is processed irrespective of ambient pH. The mobility of the pacCc200 translation product complex is markedly slower than that of the wild-type ‘closed’ (i.e. full-length) form (Figure 2G). This indicates that the conformational change resulting from the absence of interactions leads to a significantly decreased mobility of the corresponding EMSA complex, more than compensating the gain in mobility expected from the reduction in size. Therefore, the influence of the interactions possibly explains the apparent paradox that the complex of ‘open’ wild-type PacC lacking a C-terminal moiety has reduced mobility compared with the ‘closed’ form complex, in which PacC is intact.

The transition to the ‘open’ PacC form strictly correlates with appearance of a PacC intermediate truncated within residues 493–500

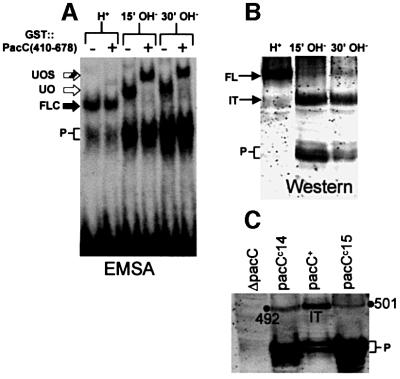

To show that alkaline pH signal reception leads to the formation of a processing-committed C-terminally truncated PacC and that this intermediate corresponds to the ‘open’ conformation, we cultured mycelia under acidic conditions and shifted them to alkaline conditions. Unprocessed ‘closed’ PacC was converted rapidly to the ‘open’ form within 15 min after the shift (Figure 3A), consistent with rapid reception of the ambient pH signal. Western analysis of these extracts using an α-PacC(5–265) antiserum raised against the N-terminal moiety of PacC showed that this correlated with the appearance, apparently at the expense of the translation product, of a PacC polypeptide of markedly reduced size (Figure 3B). Like the protein moiety of the ‘open’ PacC–DNA complex (see above), this polypeptide lacks C-terminal residues, as it reacted in western blots with α-PacC(301–529) but not with α-PacC(529–678) antiserum, and the intermediate of His10 C-terminally tagged PacC did not react with an anti-poly-His antibody, but reacted with α-PacC(301–529) (data not shown). Using truncated mutant proteins as internal standards in western blots (Figure 3C), we deduced that the C-terminus of this intermediate is located between residues 493 and 500, correlating well with that of the intermediate detected with mutants PacCΔ8, 10 and 11. These data strongly indicate that both polypeptides are the product of the same reaction. We conclude that the signalling protease cleavage site is localized within residues 493–500.

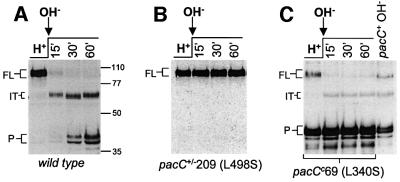

Fig. 3. The transition of the ‘closed’ to the ‘open’ PacC forms strictly correlates with the formation of a new PacC polypeptide. (A) Wild-type cells grown under acidic conditions (H+) were shifted to alkaline conditions (OH–) and protein extracts from the indicated time points were analysed by EMSA. The ‘open’ PacC form was revealed by the supershift assay with GST::PacC(410–678). Abbreviations are as in Figure 2. (B) Western analysis of extracts used in (A) with α-PacC(5–265) antiserum. FL, full-length PacC; IT, intermediate; P, processed form. (C) The C-terminal residue of the intermediate lies between residues 493 and 500. The primary translation products of two truncating pacCc alleles (leading to signal-independent processing) ending at residues 492 and 501, respectively, were used as internal standards to calibrate the size of the intermediate in a western blot where proteins were detected with α-PacC(5–265) antiserum. The size of the intermediate is clearly >492 residues and <501 residues.

We used a similar pH shift western analysis to show that the appearance, apparently at the expense of the translation product, of the wild-type intermediate is completely prevented by the palA1 mutation, even after long exposure to alkaline pH (Figure 4A and C), demonstrating, in agreement with Figure 1E for PacCΔ8, that the formation of the wild-type intermediate requires an intact pal signalling pathway.

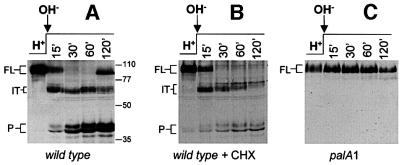

Fig. 4. Sequential conversion of the translation product into the intermediate and the processed form in a pH- and pal-dependent manner. (A–C) Wild-type or palA1 cells grown under acidic conditions (H+) were shifted to alkaline conditions (OH–). Where indicated (+ CHX), cycloheximide was added 30 min before the pH shift and maintained in the alkaline media. Protein extracts taken at the indicated time points after the pH shift were analysed by western blot with α-PacC(5–265) antiserum. FL, translation product; IT, intermediate; P, processed form.

Figure 4A and B shows pH shift experiments in the presence or absence of cycloheximide. The relatively high PacC levels occurring in the absence of cycloheximide after 30 min exposure to alkaline pH are probably due to the positive transcriptional autoregulation of pacC (an alkaline expressed gene; Tilburn et al., 1995) resulting in de novo PacC synthesis, as evidenced by the appearance of the full-length form after 120 min. The relatively low levels of PacC and the complete absence of the full-length form in the presence of cycloheximide after 30 min are consistent with its prevention of de novo protein synthesis.

In mycelia shifted to alkaline pH in the presence of cycloheximide, ∼50% of the wild-type translation product is converted to the intermediate within 15 min after the shift and, within 30 min the intermediate largely predominates (Figure 4B). These and the above data are fully consistent with a precursor–product relationship between the translation product and the intermediate, in agreement with data for PacCΔ10 (Figure 1F). The decrease in levels of the intermediate visible after 30 min (the minor mobility shift results from phosphorylation; J.Álvaro and T.Suárez, unpublished) correlated with an increase in the relative levels of the processed form (Figure 4B). As no translation product remains at 30 min, these data are fully consistent with a precursor–product relationship between the intermediate and the processed form. Moreover, the fact that pal– mutations (Figure 4C), two different pacC deletions removing the signalling protease target sequence and two missense mutations within this sequence (Figures 5, 6 and 7, see below) precluding pacC function block the signalling protease cleavage leading to the intermediate and, simultaneously, the formation of the processed form, establishes that, under normal circumstances, the translation product is converted to the processed form through the intermediate.

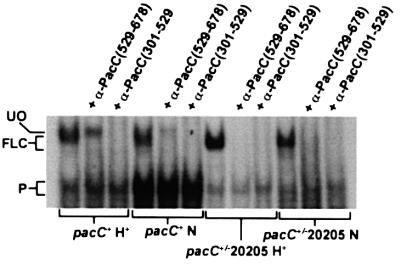

Fig. 5. The pacC+/–20205 product, permanently locked in the ‘closed’ conformation, is not converted to the processing intermediate. The relevant portion of an EMSA gel showing that the pacC+/–20205 product from either acidic or neutral growth conditions is recognized by both the α-PacC(529–678) and the α-PacC(301–529) antisera, indicating that, in contrast to the wild-type used as control, this mutant is unable to form the processing intermediate. FLC indicates the unprocessed wild-type and mutant PacC complexes.

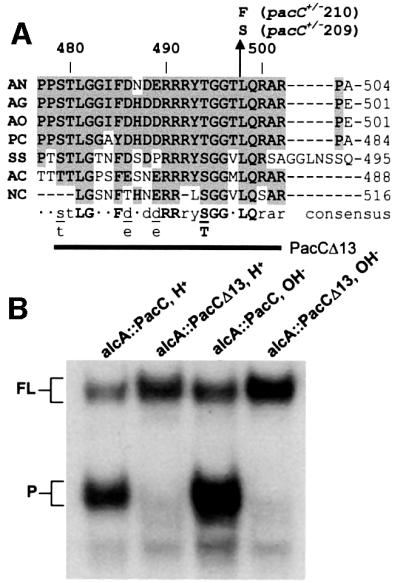

Fig. 6. The signalling protease box is essential for processing. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment showing the conserved sequence designated the signalling protease box. Identical and conserved (Phe/Tyr, Asp/Glu, Ser/Thr) residues are shadowed in grey. PacC sequences correspond as follows: AN, A.nidulans; AG, Aspergillus niger; AO, Aspergillus oryzae; PC, Penicillium chrysogenum; SS, Sclerotinia sclerotium; AC, Acremonium chrysogenum; NC, Neurospora crassa. Residue numbering for A.nidulans PacC is indicated above the sequence. The bold line corresponds to A.nidulans residues 479–502 removed by the PacCΔ13 deletion. (B) The relevant region of an EMSA gel showing that the PacCΔ13 deletion fully prevents processing.

Fig. 7. The pacC+/–209(L498S) mutation prevents both formation of the intermediate and processing. (A) Western analysis of PacC in extracts from pacC+ cells grown under acidic conditions (H+) and shifted to alkaline conditions, using α-PacC(5–265) antiserum. Samples were taken at the different time points indicated after the pH shift. FL, translation product; IT, intermediate; P, processed. (B) A similar experiment using mutant pacC+/–209 cells. (C) A similar experiment using mutant pacCc69 cells. In acidic growth conditions, the pacCc69(L340S) product is converted to the processed form without passing through the intermediate. An extract of an alkaline-grown wild-type is a control.

A ‘signalling protease box’ in PacC is essential for the proteolytic activation cascade

The above data show that upon ambient pH signalling, a protease cleaves a peptide bond in the C-terminal region of PacC, removing an ∼180 residue C-terminal fragment containing interacting region C. The resulting intermediate would be committed to processing due to disruption of the interactions maintaining the ‘closed’ conformation, which require residues 529–678. Indeed, mutant proteins truncated at, for example, residues 430, 492, 523 or 540 (i.e. lacking 248, 186, 155 or 138 C-terminal residues, respectively) are committed to processing at any ambient pH. The region containing the C-terminus of this committed intermediate is deleted by the pacC+/–20205 mutation (removing residues 465–540), which leads to an impaired ambient pH signal reception/response. The pacC+/–20205 product is almost completely locked in the ‘closed’ conformation (Espeso et al., 2000). It is fully recognized by the α-PacC(529–678) antiserum at both acidic and neutral (where signalling occurs) growth pH (Figure 5) and is therefore unable to be converted to the intermediate. In view of this strict requirement for the sequence containing the signalling protease cleavage site for the ‘closed’ to ‘open’ conformation transition, we scanned the region deleted by pacC+/–20205 for amino acid sequence conservation among proteins of the PacC family. We found a highly conserved region, designated the ‘signalling protease box’, within A.nidulans PacC residues 479–502 (Figure 6A). Deletion of this region in the PacCΔ13 mutant protein prevents processing (Figure 6B). In contrast to the wild-type, the mutant PacCΔ13 translation product is in the ‘closed’ conformation under pH signalling conditions, as determined by the EMSA/α-PacC(529–678) assay (data not shown).

Leu498 is crucial for the function of the signalling protease

The above data indicated that the absence of signalling protease cleavage leads to loss of PacC function by preventing processing. Amongst classically selected mutations, we identified two mutations in the signalling protease box, both leading to substitution of the completely conserved Leu498 (Figure 6A). pacC+/–209 is a stringent loss-of-function mutation resulting in a Leu498Ser substitution. In the wild-type, the full-length form predominating under acidic conditions is converted to the processing intermediate (and processed product) after shifting mycelia to alkaline pH (Figure 7A). In contrast, this conversion was completely blocked in the mutant (Figure 7B). pacC+/–210 is a weaker loss-of-function mutation resulting in a Leu498Phe substitution. In agreement with its less extreme phenotype, this mutation does not fully prevent processing (data not shown). These experiments show that a hydrophobic, preferably aliphatic, residue at position 498 within the signalling protease box is crucial for cleavage of the full-length form to the intermediate. Finally, as pacC+/–209 prevents the formation of both the intermediate and the processed form, these data demonstrate the role of signalling proteolysis in the formation of a physiological intermediate in the proteolytic processing activation of PacC.

The pacCc69 (Leu340Ser) mutation bypasses the need for the signalling protease step

pacCc69 leads to PacC processing at any ambient pH. Its Leu340Ser substitution within interactive region B (Espeso et al., 2000) disrupts the ‘closed’ PacC conformation. As in the wild-type, shifting cells to alkaline conditions rapidly leads to the formation of the intermediate at the expense of the full-length form (Figure 7C), showing that the mutation does not affect the signalling protease step. Also as in the wild-type, this C-terminally truncated form is largely absent under acidic growth conditions. However, in marked contrast to the wild- type, it is the processed form which predominates under acidic conditions (Figure 7A and C). It follows that this mutant full-length form, which lacks the interactions maintaining the inaccessibility to the processing protease, can be an efficient substrate for the processing protease. This is confirmed by the ability of the Leu340Ser substitution to suppress the pacC+/–20205 phenotype. This reinforces the conclusion that the signalling cleavage functions by disabling interactions leading to the ‘closed’ conformation.

Discussion

We show here that the proteolytic activation of PacC takes place by a cascade mechanism involving two sequential proteolytic steps. The translation product is first converted to a committed intermediate by a signalling protease in a pal pathway-dependent manner. This intermediate is the actual substrate of a subsequent pal-independent processing proteolysis (Figure 8). This two-step mechanism resembles Rip (regulated intramembrane proteolysis) in that a primary regulated cleavage is a prerequisite for the final cleavage. In contrast to Rip, however, there is no evidence that PacC processing takes place in a membrane.

Fig. 8. Two-step PacC processing model. The translation product is converted to a committed intermediate by removal of the C-terminal interacting region C (blue box) by the signalling protease, in a pal pH signalling pathway-dependent reaction. The signalling protease box, essential for this reaction, is shown in yellow. The resulting intermediate corresponds to the ‘open’ PacC conformation in our previous models (Espeso et al., 2000; Mingot et al., 2001). In agreement with our predictions, the interactions maintaining the protease-inaccessible conformation in the translation product have been disorganized by removal of the crucial C-terminal interacting region in this intermediate/‘open’ PacC, which is therefore committed to processing (see text for details). A thick arrow marks the position of the final processing site. The possible existence of an ‘open’ conformation of the translation product (and any relationship it might have to the committed intermediate and/or processed form) is too speculative to include at present (see text).

An overview of the two-step proteolytic activation

PacC is a 674 residue zinc finger transcription factor activated by proteolytic processing (Orejas et al., 1995). Under alkaline ambient pH conditions, the ∼425 C-terminal residues are removed by proteolysis. In inappropriate (i.e. acidic) circumstances, the PacC translation product is resistant to the activating proteolysis because a C-terminal domain of the protein (within residues 529–678) interacts with upstream domains blocking access to the processing protease. This protease-inaccessible form of the protein has been designated the ‘closed’ form (Mingot et al., 1999, 2001; Espeso et al., 2000) (Figure 8).

Signalling through the alkaline pH-sensing pal pathway leads to disorganization of the ‘closed’ conformation, rendering the protein accessible to the processing protease (Espeso et al., 2000). This form of PacC previously has been designated the ‘open’ form, to emphasize its accessibility to the processing protease. However, the molecular nature of this ‘open’ PacC form has remained elusive. We demonstrate here that ‘open’ PacC is actually a polypeptide lacking the ∼180 C-terminal residues. This polypeptide is a committed (i.e. pH signal-independent) processing intermediate originating from a proteolytic cleavage between residues 493 and 500 preceding the actual processing reaction. These residues occur in a region of high sequence conservation among the more closely related members of the PacC family, designated the signalling protease box. The signalling proteolysis leads to the ‘open’ conformation of PacC by removing the key processing-protecting interacting region C (Figure 8). In the wild-type, the steady-state pool of primary translation product present under acidic conditions is completely converted to the committed intermediate within 30 min of a shift to alkaline conditions.

The signalling protease is distinct from the processing protease and recognizes the conserved signalling protease box

Unlike the processing proteolysis, the signalling proteolysis is regulated by ambient pH and requires the integrity of the pal signalling pathway. Neither protease requires the sequence encompassing the processing protease site at residues ∼252–254 (Figure 1D and E; Mingot et al., 1999), but the signalling protease does require the signalling protease box, including residue Leu498 (Figures 6 and 7B). In marked contrast, this 479–502 signalling protease box is dispensable for the processing protease. In illustration, the 479–502 region is removed by the 465–540 deletion (pacC+/–20205), which explains why this mutant product is locked in the ‘closed’ conformation at any ambient pH (Espeso et al., 2000). Its pacCc2020507 intragenic suppressor leads to a Leu340Ser substitution, identical to that resulting from pacCc69 (Mingot et al., 1999). Leu340Ser disorganizes the intramolecular interactions maintaining the ‘closed’ PacC conformation and leads to pH-independent processing and alkalinity mimicry. The processing efficiency of the double mutant Leu340Ser, also deleted for residues 465–540, is indistinguishable from that of the single Leu340Ser mutant (Espeso et al., 2000), formally establishing that the processing protease does not require the signalling protease box. It should also be noted that there is efficient processing of proteins truncated slightly upstream of the signalling protease box, such as the pacCc75 (5–430) product (Mingot et al., 1999).

The product of the signalling protease reaction is a committed intermediate in the proteolytic activation cascade

The acquisition of accessibility by the PacC substrate to the processing protease is the key step in the regulation of its proteolytic activation. In our model (Figure 8), the action of the signalling protease removes interacting region C, which protects the translation product from the processing protease. The resulting truncated polypeptide, a committed intermediate in the proteolytic cascade, resembles the translation products of the major subclass of pacCc alleles which are processed efficiently at any ambient pH. These phenotypically extreme pacCc alleles truncate the protein between residues 407 and 578 inclusive (Tilburn et al., 1995; Mingot et al., 1999). In several cases, it has been shown that these truncating pacCc alleles are epistatic to pal– mutations at the level of their pH-independent processing (Denison et al., 1995; Orejas et al., 1995), demonstrating that the pal signal is no longer required after the C-terminal interacting domain C has been removed. In agreement with the commitment to processing of this intermediate, its significant accumulation occurs only with mutant proteins such as PacCΔ8, PacCΔ9, PacCΔ10 or PacCΔ11, which lack the 266–407 processing protease efficiency determinant and are therefore significantly impaired in processing.

The signalling protease step is a prerequisite for the processing protease step

The Leu498Ser substitution, involving a completely conserved residue within the signalling protease box, provides crucial evidence that signalling cleavage is, under normal circumstances, a prerequisite for the definitive processing step. This mutation, which almost certainly affects an essential residue for the activity of the signalling protease, prevents both the signalling cleavage and the processing cleavage steps. As expected, this mutant shows an extreme acidity-mimicking phenotype, indistinguishable from that of pacC+/–20205 or non-leaky pal loss-of-function mutations. The less extreme phenotype of a Leu498Phe substitution (pacC+/–210) provides corroboration.

For certain mutant proteins, however, the signalling step is not a prerequisite for processing. pacCc69 (L340S) is a prototype of a single amino acid substitution leading to pH-independent processing. Leu340Ser, within interacting domain B, disorganizes the ‘closed’ conformation by disrupting the interactions between the C-terminal domain C and the upstream domains (Espeso et al., 2000). In common with the wild-type, under acidic conditions, the signalling cleavage does not take place in this mutant. However, in contrast to the acidic-grown wild-type, the translation product is converted to the processed form, demonstrating that the crucial role of the cleavage step is to disrupt the ‘closed’ conformation by removing interacting region C. The fact that a full-length protein in which the protecting intramolecular interactions have been disabled can be a substrate of the processing protease might explain why processing is severely but not fully abolished in a null pal– background. This residual processing may be due to the presence of a small proportion of interaction-disrupted full-length PacC in equilibrium with the ‘closed’ form.

Implications of the two-step mechanism

The signalling cleavage step might be regulated at the level of the signalling protease activity and/or by the susceptibility of the PacC substrate to the protease. Our results establish that the pal signal is absolutely required for the signalling cleavage, but do not distinguish among these possibilities. A likely candidate for the signalling protease is the calpain-like cysteine protease encoded by palB. This would imply that the 479–502 signalling protease box is the PalB recognition site. The fact that calpain, which does not show strong sequence specificity for substrate cleavage, has some preference for leucine in position P2 of the target (Carafoli and Molinari, 1998) is very suggestive in view of the strong requirement of the signalling protease for Leu498.

PalB is conserved in several other ascomycetes, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Futai et al., 1999). In S.cerevisiae Rim101p (the PacC homologue), only the ∼100 C-terminal residues are removed proteolytically in a RIM pathway- (homologous to the Aspergillus pal pathway) dependent manner (Li and Mitchell, 1997; Xu and Mitchell, 2001). Only a single Rim101p cleavage step has been demonstrated, and Xu and Mitchell (2001) speculate that an analogous pH signal-dependent cleavage step (i.e. that leading to the committed intermediate demonstrated here) precedes the final processing step for Aspergillus PacC. Whether the signalling cleavage step described here is mechanistically analogous to Rim101p cleavage remains to be demonstrated. PacC final processing can occur in yeast but, despite the presence of the RIM pathway, only if signal transduction is bypassed (Mingot et al., 1999). This suggests that the processing protease is conserved in yeast even if it is not involved in Rim101p processing.

In contrast to the translation product, the intermediate described here (previously denoted the ‘open’ PacC conformation) shows preferential nuclear localization (Mingot et al., 2001). As it contains all the residues required for transcriptional regulation, we cannot exclude the possibility that this previously unnoticed polypeptide has a functional role in pH regulation, in addition to that of the processed form.

Our findings might have implications for other systems regulated by proteolytic processing, notably the transcription factor Cubitus interruptus. The processed Ci protein resulting from the absence of Hedgehog signalling is a transcriptional repressor, whereas a form derived from the translation product, whose processing is prevented in the presence of the morphogen, is a transcriptional activator. The dominant, Hedgehog-insensitive cicell-2 allele encodes a protein truncated at residue 975 of the 1386 residue translation product, and acts as a constitutive repressor (Methot and Basler, 1999). This would suggest that the truncated cicell-2 translation product is committed to processing, which would implicate residues 976–1386 in preventing processing in a Hedgehog-dependent manner, perhaps through intramolecular interactions similar to those ocurring in PacC.

Materials and methods

Aspergillus nidulans techniques

For A.nidulans gene designations, see Clutterbuck (1993). Phenotype testing of pacC mutations followed Tilburn et al. (1995) and references therein.

Mycelia for protein extraction were grown in sucrose-PPB adjusted to acidic (pH 5.5), neutral (pH 6.8) or alkaline (pH 7.8) pH values (Orejas et al., 1995), using 100 mM rather than 200 mM phosphate buffers. Alternatively, mycelia were grown in MMAD, which is Aspergillus minimal medium (Cove, 1966) with 5 mM urea, 1% glucose and 1× ‘yeast dropout’ solution (as recommended by Clontech). This medium was buffered as for sucrose-PPB.

In pH shift experiments, mycelia were grown for 16.5 h at 37°C under acidic conditions before the shift to alkaline pH. As more extreme pH values were required, we used MMAD buffered either at pH 4.2 with 0.5 M NaH2PO4 or at pH 8 with 0.25 M Na2HPO4 (Figure 3). For experiments in Figures 4 and 6, we used 3% sucrose-PPB buffered at pH 4.4 with 50 mM sodium citrate (final pH before the pH shift 4.3–4.4) or to pH 8.3 with 100 mM HEPES–NaOH (final pH 7.5–7.9). Where noted, cycloheximide was added to 0.2 (MMAD) or 0.5 mg/ml (PPB, where more substantial growth takes place) 30 min before pH shifts and was also present in the alkaline media. The presence of 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide inhibits protein synthesis by >90% (Morozov et al., 2000).

Novel pacC alleles

pacC alleles are described in Table I. pacC deletion alleles except pacCΔ13 were obtained by homologous gene replacement. pacCΔ13 almost certainly leads to molybdate hypersensitivity and therefore could not be selected using the protocol described below. Therefore, PacCΔ13 was expressed under the control of the alcAp promoter from a single-copy transgene integrated at argB (Mingot et al., 1999). All deletion alleles were constructed by PCR and verified by DNA sequencing to rule out the presence of PCR-induced mutations. A recombinant gene expressing PacC tagged with the His10-containing peptide GNSDDDDKGMG(H)10SSG (denoted PacC-His10, Figure 2) was also constructed by gene replacement. A recombinant strain expressing PacC tagged with GFP at its C-terminus has been described (Mingot et al., 2001).

Table I. Mutant pacC alleles characterized in this work.

| Allele | DNA mutationa | Mutant protein | Change in protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| pacCΔ8 | [del(1103–1187); del(1410–2179)] | (5–168)::(408–678) | Δ(169–407) |

| pacCΔ9 | [del(1103–1187); del(1410–1660); del(1754–2179)] | (5–168)::(235–265)::(408–678) | Δ(169–234, 266–407) |

| pacCΔ10 | [del(1103–1187); del(1476–1528); del(1754–2179)] | (5–265)::(408–678) | Δ(266–407) |

| pacCΔ11 | [del(1103–1187); del(1476–1528); del(1661–2179)] | (5–234)::(408–678) | Δ(235–407) |

| pacCΔ13 | [del(1103–1187); del(1476–1528); del(2393–2464)] | (5–478)::(503–678) | Δ(479–502) |

| pacCc15 | 2457ins27 | 5–500 + Ser | A501S; R502stop |

| pacC+/–209 | T2451C | Leu498Ser | L498S |

| pacC+/–210 | G2452T | Leu498Phe | L498F |

apacC coordinates as in GenBank Z47081 (Tilburn et al., 1995). Nucleotides 1103–1187 and 1476–1528 correspond to INV1 and INV2, respectively.

The alkalinity-mimicking pacCc15 allele was obtained serendipitously in a transformation experiment. pacC+/–209 and 210 are UV-induced mutations selected in a diploid of genotype areAr5 pyroA4 pantoB100/areAr5 inoB2 glrA1 fwA1 as enabling utilization of 10 mM γ-aminobutyric acid as nitrogen source in glucose minimal medium (see Arst et al., 1994). Haploid strains carrying pacC+/–209 and 210 were obtained by benlate-induced haploidization of the respective mutant diploids and subsequent outcrosses.

Gene replacements

The pacC gene replacement procedure is based on the extreme hypersensitivity to molybdate conferred by a ΔpacC mutation. Replacing the ΔpacC::pyr4 allele (Tilburn et al., 1995) homologously by mutant pacC alleles ranging from partial loss of function to gain of function results in increased resistance to molybdate. Plasmid pSpacC, a pBS-SK+ derivative containing the pacC gene from coordinates –825 to 3912, relative to the ATG, was used to introduce site-directed mutations. Position 3912 is located 925 bp downstream of the stop codon. Mutant pacC alleles plus flanking sequences were obtained as linear EcoRI–XbaI restriction fragments, which were used for transformation (Tilburn et al., 1983). Transformants were selected on plates containing 12.5 mM sodium molybdate, 10 mM uracil and 10 mM uridine. Those putatively carrying the desired gene replacement were confirmed by pyrimidine auxotrophy and Southern blotting analysis.

Protein extraction

Protein extractions were as described (Orejas et al., 1995) or as follows: lyophilized mycelium (0.25 g) was ground with a 1/4 inch ceramic sphere for 10 s in a FastPrep machine (BIO101) at minimal speed. A 1 ml aliquot of A50 buffer containing protease inhibitors (Mingot et al., 1999) was added and proteins were extracted by gently rotating the samples for 1.5 h at 4°C. Extracts were clarified by microcentrifugation at 14 000 r.p.m. and 4°C for 30 min.

Western analysis

Protein extracts (50 µg) were analysed by western blotting using 8 or 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels (Mingot et al., 1999). PacC forms were detected with a rat α-PacC(5–265) polyclonal antiserum (1/4000) directed against PacC residues 5–265, using a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rat IgM + IgG secondary antiserum (Southern Biotechnology, 1/4000), or with a mouse α-PacC(301–529) polyclonal antiserum (1/2000) directed against PacC residues 301–529, using peroxidase-coupled sheep anti-mouse IgG antiserum (1/4000; Sigma A5906) as secondary antiserum.

EMSA, supershift assays and antisera

EMSA was as described (Orejas et al., 1995), using 5 µg of protein and the 32P-labelled ipnA2 PacC-binding site (Tilburn et al., 1995). Protein–DNA complexes were resolved in 4 or 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. Supershift assays (Espeso et al., 2000) were performed with 2 µg of affinity-purified GST::PacC(410–678). Antisera recognizing epitopes in protein–DNA complexes were polyclonal rabbit α-PacC(529–678) antiserum (Orejas et al., 1995), rabbit anti-GFP antiserum (raised against purified His-tagged GFP), mouse monoclonal α-poly-His antibody (Clone His-1; Sigma A7028) or mouse α-PacC(301–529) antiserum. Unless otherwise indicated, 0.5 µl of His-1 or 2 µl of each polyclonal antiserum was added to the binding reactions.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank A.Akintade and E.Reoyo for technical assistance, and the CICYT, the BBSRC and the EU [through grants BIO2000-920 (M.A.P.), 60/P11494 (H.N.A.) and QLK3-CT-1999-00729 (M.A.P. and H.N.A.), respectively] for support. E.D., J.A., L.R. and E.A.E. held a Basque Government, a PFPI-MCyT fellowship, a BBSRC studentship and a MCyT postdoctoral contract, respectively.

References

- Arst H.N. Jr, Bignell,E. and Tilburn,J. (1994) Two new genes involved in signalling ambient pH in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet., 245, 787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.S. and Goldstein,J.L. (1999) A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells and blood. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 11041–11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.S., Ye,J., Rawson,R.B. and Goldstein,J.L. (2000) Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell, 100, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddick M.X., Brownlee,A.G. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1986) Regulation of gene expression by pH of the growth medium in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet., 203, 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E. and Molinari,M. (1998) Calpain: a protease in search of a function? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 247, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutterbuck A.J. (1993) Aspergillus nidulans. In O’Brien,S.J. (ed.), Genetic Maps. Locus Maps of Complex Genomes. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 3.71–3.84

- Cove D.J. (1966) The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 113, 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison S.H., Orejas,M. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1995) Signaling of ambient pH in Aspergillus involves a cysteine protease. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 28519–28522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison S.H., Negrete-Urtasun,S., Mingot,J.M., Tilburn,J., Mayer,W.A., Goel,A., Espeso,E.A., Peñalva,M.A. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1998) Putative membrane components of signal transduction pathways for ambient pH regulation in Aspergillus and meiosis in Saccharomyces are homologous. Mol. Microbiol., 30, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeso E.A. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (2000) On the mechanism by which alkaline pH prevents expression of an acid-expressed gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 3355–3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeso E.A. and Peñalva,M.A. (1996) Three binding sites for the Aspergillus nidulans PacC zinc finger transcription factor are necessary and sufficient for regulation by ambient pH of the isopenicillin N synthase gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 28825–28830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeso E.A., Tilburn,J., Sánchez-Pulido,L., Brown,C.V., Valencia,A., Arst,H.N.,Jr and Peñalva,M.A. (1997) Specific DNA recognition by the Aspergillus nidulans three zinc finger transcription factor PacC. J. Mol. Biol., 274, 466–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeso E.A. et al. (2000) On how a transcription factor can avoid its proteolytic activation in the absence of signal transduction. EMBO J., 19, 719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futai E., Maeda,T., Sorimachi,H., Kitamoto,K., Ishiura,S. and Suzuki,K. (1999) The protease activity of a calpain-like cysteine protease in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for alkaline adaptation and sporulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 260, 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., May,M.J. and Kopp,E.B. (1998) NF-κB and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 16, 225–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe T., Matuschewski,K., Rape,M., Schlenker,S., Ulrich,H.D. and Jentsch,S. (2000) Activation of a membrane-bound transcription factor by regulated ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent processing. Cell, 102, 577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham P.W. (1998) Transducing Hedgehog: the story so far. EMBO J., 17, 3505–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. and Mitchell,A.P. (1997) Evidence for proteolytic activation of Rim1p, a positive regulator of yeast sporulation and invasive growth. Genetics, 145, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methot N. and Basler,K. (1999) Hedgehog controls limb development by regulating the activities of distinct transcriptional activator and repressor forms of Cubitus interruptus. Cell, 96, 819–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingot J.M. et al. (1999) Specificity determinants of proteolytic processing of Aspergillus PacC transcription factor are remote from the processing site and processing occurs in yeast if pH signalling is bypassed. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1390–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingot J.M., Espeso,E.A., Díez,E. and Peñalva,M.A. (2001) Ambient pH signaling regulates nuclear localization of the Aspergillus nidulans PacC transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 1688–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov I.Y., Martínez,M.G., Jones,M.G. and Caddick,M.X. (2000) A defined sequence within the 3′ UTR of the areA transcript is sufficient to mediate nitrogen metabolite signalling via accelerated deadenyl ation. Mol. Microbiol., 37, 1248–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete-Urtasun S., Denison,S.H. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1997) Characteriz ation of the pH signal transduction pathway gene palA of Aspergillus nidulans and identification of possible homologs. J. Bacteriol., 179, 1832–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete-Urtasun S., Reiter,W., Díez,E., Denison,S.H., Tilburn,J., Espeso,E.A., Peñalva,M.A. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1999) Ambient pH signal transduction in Aspergillus: completion of gene characterization. Mol. Microbiol., 33, 994–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orejas M., Espeso,E.A., Tilburn,J., Sarkar,S., Arst,H.N.,Jr and Peñalva,M.A. (1995) Activation of the Aspergillus PacC transcription factor in response to alkaline ambient pH requires proteolysis of the carboxy-terminal moiety. Genes Dev., 9, 1622–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A. (1999) Gli proteins and Hedgehog signaling: develop ment and cancer. Trends Genet., 15, 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilburn J., Scazzocchio,C., Taylor,G.G., Zabicky-Zissman,J.H., Lockington,R.A. and Davies,R.W. (1983) Transformation by integration in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene, 26, 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilburn J., Sarkar,S., Widdick,D.A., Espeso,E.A., Orejas,M., Mungroo,J., Peñalva,M.A. and Arst,H.N.,Jr (1995) The Aspergillus PacC zinc finger transcription factor mediates regulation of both acid- and alkaline-expressed genes by ambient pH. EMBO J., 14, 779–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. and Mitchell,A.P. (2001) Yeast PalA/AIP1/Alix homolog Rim20p associates with a PEST-like region and is required for its proteolytic cleavage. J. Bacteriol., 183, 6917–6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]