Abstract

Conventional suturing and stapling cause additional trauma, pain, and cost for patients. As alternatives, existing bioadhesives suffer from imprecise fabrication, limited wet tissue adhesion, and insufficient biological functionalities for effective wound management. This work proposes biomimetic hydrogel bioadhesives composed of modified natural tannic acid (TA), hyperbranched polylysine (HPL), and acrylic acid (AA), abbreviated PTLAs, to offer solutions for tissue adhesion under challenging environments (underwater, body fluids, cold, pressure), and for enhanced healthcare. These PTLAs are fabricated via 3D printing, enabling the precise and controlled production of bioadhesives that are customized in a personalized manner with great reproducibility. Inspired by molluscs, developed PTLAs exhibit robust wet and underwater tissue adhesion, outperforming commercial and many recently reported bioadhesives. Ex vivo lamb and in vivo rat models demonstrate ultrafast (5 s) and efficient sealing and hemostasis. Exceptional freeze resistance and pressure resistance further expand their applicability to extreme environments. Meanwhile, coupled with superior infection resistance, PTLAs ensure enhanced wound healthcare while sealing and hemostasis. Further, their self‐gelling feature supports dry powder adhesion/sealing applications, practical packaging, and long‐term storage. Overall, adaptive tissue‐like PTLAs present transformative potential as bio‐tapes, bio‐bandages, bio‐sealants, bio‐carriers, etc., paving the way for next‐generation bioadhesives design and enhanced healthcare solutions.

Keywords: 3D printing, healthcare, hemostasis, hydrogel bioadhesive, infection resistance, tissue adhesion

Biomimetic 3D‐printed hydrogel bioadhesives (PTLAs) are designed to address the limitations of existing bioadhesives, offering solutions for challenging tissue adhesion and enhanced healthcare. These PTLAs feature robust wet/underwater tissue adhesion/sealing, superior freeze/pressure and infection resistance, and adaptive self‐healing/gelling capacity, presenting transformative potential as bio‐tapes, bio‐bandages, bio‐sealants, bio‐carriers, etc., and inspiring next‐generation bioadhesives design.

1. Introduction

Employing bioadhesives instead of conventional suturing and stapling could significantly minimize additional trauma and reduce the pain and cost for patients.[ 1 ] Existing bioadhesives such as polycyanoacrylate and polyurethane‐based bio‐glues achieve rapid adhesion by forming a glassy and stiff interface with tissues, limiting dynamic movements.[ 2 ] Hydrogel bioadhesives with extracellular matrix (ECM)‐ and soft tissue‐like features are capable of flexible tissue adhesion and biomedical uses, as well as encapsulation of bioactive agents such as therapeutics, cells, and miRNAs.[ 3 ] However, achieving strong adhesion on wet tissue/organ surfaces is challenging in widespread biomedical fields such as injury, hemostasis, wound closure, tissue regeneration, target delivery, and post‐management.[ 4 ] Most reported hydrogel adhesives suffer from low biocompatibility, high swelling, limited physical/biological functionalities, slow adhesion formation, and poor mechanical match with tissues, especially in wet conditions.[ 2 , 5 ] Hydration film formed on tissue surfaces under wet microenvironments, acting as a weak boundary layer to prevent tissue adhesion; water molecules could interrupt and decrease the surface energy, and further break the interfacial interactions.[ 4a ] On the other hand, the presence of body fluids, such as arterial blood, during bleeding will significantly affect the adhesion behavior.[ 2b ] In addition to wet tissue adhesion and hemostasis, bioadhesives are also required to have a substantial capacity for healthcare, such as infection control, while hemostasis. Infection hinders platelet aggregation and clot maturation, leaving the wound vulnerable. Moreover, the wound is a fertile infection locale containing high adipose content that is nutrient‐rich for bacteria and other microorganisms.[ 6 ] Surgical site or other wound infections lead to the prolonged elevation of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and elongate the inflammatory phase.[ 7 ] The oxidative stress of adjacent tissues and the immune system will produce elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS),[ 8 ] an over‐accumulation of ROS will cause oxidative tissue damage and cell death, degrade ECM proteins, stimulate migration, and activate adhesion molecules, leading to tissue adhesion and scar tissue formation,[ 9 ] resulting in prolonged wound healing. Mature microbial biofilms that are shielded from the immune system and antibiotics, persistent infections can cause chronic ulcers and even chronic diseases.[ 10 ] In severe cases, uncontrolled wound infections can spread into the bloodstream, leading to sepsis.

Currently, bio‐inspired hydrogel adhesives have emerged as one of the most progressed bioadhesives, enabling on‐demand adhesion to wet tissue surfaces.[ 11 ] Natural molluscs, such as mussels and snails, can robustly adhere to any wet solid surface by generating adhesive byssus and mucus. Byssus is rich in catechol groups such as L‐3,4‐dihydroxyphenylalanine (L‐Dopa) in mussel foot proteins, while mucus contains intertwined positively charged proteins and anionic polymers, as shown in Figure 1a. Several remarkable catechol‐based wet adhesives have been developed, and the adhesion achieved through multiple interactions such as hydrogen bonding,[ 12 ] hydrophobic interactions,[ 13 ] metal coordination,[ 14 ] Π–Π interactions,[ 15 ] Michael addition,[ 16 ] etc. between L‐Dopa and the substrate.[ 17 ] Another promising class of catechol‐rich structures is polyphenols. Tannic acid (TA) is a natural polyphenolic compound found in abundant plants, such as oak bark, hemlock, tea, grapes, and coffee.[ 18 ] In terms of biological functions, it can inhibit the growth of various viruses and bacteria, as well as scavenge free radicals to reduce the release of inflammatory cytokines.[ 19 ] Additionally, TA facilitates the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and stimulates the production of collagen, thereby accelerating wound healing.[ 20 ] Owing to notable physical and biological functionalities, TA has been introduced in the formulations of numerous adhesive materials as an additive assembled through physical interactions to enhance adhesive capability.[ 2 , 11 , 21 ] However, adhesion under wet conditions, especially on wet tissue surfaces, is still challenging. Gao et al.[ 22 ] developed a medical adhesive TASK composed of tannic acid and silk fibroin; the adhesive strength of TASK on overhead projector films was increased about 100 times by involving TA. Unfortunately, when this adhesive was applied to wet tissues, such as rabbit liver, heart, and skin, its adhesiveness decreased by more than 20 times. On the other hand, TA‐loaded hydrogels are pH‐ and enzyme‐sensitive; free TA or hydrolysate gallic acid (GA) will diffuse out, altering the microenvironment and affecting biocompatibility in local areas,[ 23 ] which necessitates the need for a more stable adhesive system comprising such catechol‐rich moiety. In this context, Westerman et al.[ 24 ] reported a sustainably sourced adhesive system consisting of chemically crosslinked epoxidized soy oil, malic acid, and tannic acid. With the TA contribution, Soy‐mal‐tan exhibited leading adhesive strength against aluminium, steel, polyvinyl chloride, teflon, and wood, outperforming most current industrial products. This reveals that incorporating TA via stable covalent bonds can significantly enhance adhesion performance. While there are studies focusing on such stable adhesive systems, most of these adhesives lack the design of UV‐sensitive and printable catechol chemistry for precise fabrications and personalized applications. Recently, printed materials have been in great demand for advanced biomedical applications, including bioadhesives,[ 25 ] due to their advantages over traditional preparation techniques. Compared to traditional thermally induced free radical polymerization or other chemical reactions that usually require a few hours, printing occurs in a few minutes, significantly saving time. This allows bioadhesives to be prepared on‐site or in situ, avoiding advanced preparation and storage issues. Although the injectable bioadhesives solved this problem to some extent, the injection time is difficult to control. Moreover, uncertainty in the cross‐linking degree before and after injection can result in issues such as syringe blockage or uncontrolled precursor diffusion, highlighting the need for further investigation into the repeatability and reliability of such injectable systems.[ 26 ] In contrast, three‐dimensional (3D) printing technology can accurately create materials that are customized in a personalized manner with greater reproducibility,[ 27 ] ensuring consistent quality across batches.[ 28 ] At the same time, this additive manufacturing minimizes excess materials, which is more economical and environmentally friendly compared to bulk preparation methods. In terms of biological applications, the printing process can be performed in sterile environments, highly preventing contamination risks. For example, bioprinting can achieve cell‐laden/miRNA‐laden fabrications through mixing the miRNAs and live cells with precursor solution.[ 29 ] More importantly, 3D printing enables precise control over the microstructure of printed materials through layer‐by‐layer (LBL) additive manufacturing, allowing the creation of microporous architectures that closely mimic the spatial structure of natural biological tissues. Beyond that, the recent progress in advanced 4D/5D printing technologies has driven the development of responsive materials and design strategies capable of achieving precise and programmable shape changes upon external stimulations for demanding biomedical processes.[ 30 ]

Figure 1.

Design and fabrication of hydrogel bioadhesives. a) Schematic‐structural illustration of bio‐inspired adhesive from mussels and snails. b) Non‐covalent and covalent modifications of tannic acid. c) Synthesized hyperbranched polylysine. d) Acrylic acid. e) Schematic illustration of UV‐induced hydrogel bioadhesive formation. f) Transparent PTLA hydrogel prepared via UV‐induced facile photopolymerization. g) Chemical and physical interactions within the PTLAs. h) High‐resolution 3D printing of PTLA objects: Technion logo object (design, h1; 3D printed, h2 and h3), grid object (design, h4; 3D printed, h5 and h6), flower object (design, h7; 3D printed, h8 and h9; surface profile of printed flower, indicating smooth surface, h10), microneedle object (design, h11; 3D printed, h12), (h13) schematic illustration of shape memory program and mechanism, (h14) shape memory process of 3D printed PT5L3A flower object, indicating programable and rapid shape recovery capacity within 8 s. i) In situ ultrafast hydrogel formation within 10 s yields a stretchable hydrogel, with a UV wavelength of 395 nm. j) FTIR monitors the in situ hydrogel formation process and confirms the disappearance of C═C bonds after 12 s. k) PTLAs fabricated bio‐bandages and bio‐tape, strongly indicating their programmability and flexibility in fabrication.

Therefore, inspired by nature (Figure 1a), to improve tissue adhesion and achieve precise, stable bioadhesives design, we performed covalent methacrylate modification of catechol‐rich tannic acid (MTA3, Figure 1b) to make it UV‐sensitive and printable; non‐covalent modified tannic acid MTA1 and MTA2 were also synthesized for comparison studies. Meanwhile, facile green‐synthesized positively charged hyperbranched polylysine (HPL, Figure 1c) and anionic acrylic acid (AA, Figure 1d) were employed together for hydrogel bioadhesives preparation. HPL consists of both units of α‐poly‐l‐lysine (α‐PL) and ɛ‐poly‐l‐lysine (ɛ‐PL). Previous studies have explored that α‐PL can promote cell adhesion and proliferation.[ 31 ] ɛ‐PL has been approved as an antibacterial agent in a wide variety of products by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2004), which could inhibit bacterial growth by intervening in their metabolic processes;[ 32 ] with the positive charge, it can bind to the surface of the bacterial membrane and enhance the permeability of membrane and wall, triggering cell lysis and death.[ 33 ] On the other hand, various poly(acrylic acid)‐based adhesives have demonstrated rapid and robust wet tissue adhesion capacities,[ 5 , 34 ] which can be further enhanced by cooperating with HPL. Subsequently, all‐in‐one tannic acid‐based hydrogel bioadhesives (PTLAs) were fabricated via digital light processing (DLP)‐based 3D printing in high resolution. This precise printing allows PTLAs to be fabricated into control‐sized bio‐bandage, bio‐tape, patch, and complex‐shaped flower, grid, microneedle, etc., at micro‐ and millimeter scales. Meanwhile, compared to ordinary UV‐induced photopolymerization, 3D printed PTLAs exhibited a more uniform network arrangement and significantly enhanced mechanical performance. Moreover, these hydrogel bioadhesives could also be formed in situ, induced by a UV flashlight within 10 s, which enables the facile preparation and introduction of these PTLAs to targeted or irregular locations through minimally invasive procedures.[ 35 ] Inspired by natural molluscs, biomimetic PTLAs exhibit robust wet and underwater tissue adhesion performance over commercial bio‐glues, fibrin glue, histoacryl, and many recently reported advanced bioadhesives. Ex vivo lamb brain/lung and in vivo rat liver/heart models demonstrate ultrafast (within 5 s) and efficient sealing and hemostasis, while their outstanding antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antibiofilm capacities simultaneously ensure effective infection control. Meanwhile, the superior antifreeze (no freezing until −90 °C) and pressure resistance that significantly exceeds normal arterial blood pressure further expand their applicability to extreme environments. Further, the remarkable self‐gelling feature of PTLA dry powder offers potential sealing and adhesion applications using these bioadhesives as powder or dry patches, which are practical for packaging and long‐term storage. On top of that, in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility studies suggest the non‐toxic nature of these PTLAs, supporting a significant promise for enhanced tissue adhesion, hemostasis, and healthcare solutions.

2. Results

2.1. Design and Fabrication of PTLAs

Integrating the inspirations of natural adhesives, precise bioadhesives design, and enhanced physical and biological performance, in this work, we performed TA modifications (Figure S2, Supporting Information) using three different approaches and HPL preparation (Figure S8, Supporting Information) to design advanced hydrogel bioadhesives. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) characterizations proved the successful synthesis of MTA1 (Figures S3 and S7, Supporting Information), MTA2 (Figures S5 and S7, Supporting Information), MTA3 (Figures S6 and S7, Supporting Information), and HPL (Figure S9, Supporting Information); and zeta potential verified the positively charged nature of HPL (Figure S10, Supporting Information). Subsequently, transparent PTLA hydrogel (Figure 1f) was obtained via facile photopolymerization under a UV chamber (Figure 1e), confirming the photocurable capacity of this formulation, where the hydrogel networks were constructed through the integration of covalent bonding, Π–Π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and ionic interactions (Figure 1 g, Figures S11 and S12, Supporting Information). Next, as‐designed PTLA bioadhesives were fabricated by DLP‐based 3D printing. As seen in Figure 1h, this formulation can be 3D printed into various objects with different sizes in high resolution, such as “Technion Logo” (Figure 1h2,h3), grid (Figure 1h5,h6), flower (Figure 1h8,h9), and microneedle (Figure 1h11,h12). Surface profiles (Figure 1h10, Figure S13, Supporting Information) of the marked areas in the flower revealed smooth printed surfaces. Moreover, the shape memory behavior of printed PTLAs was examined using the PT5L3A flower as a model object. The temporary shape was obtained via mechanical deformation and subsequent −20 °C fixation and then programmed at 25 °C; the digital snapshots show that it can memorize its permanent shape in 8 seconds (Figure 1h14). Shape memory polymer (SMP) network contains covalent netpoints and dynamic switching segments. The netpoints determine the permanent shape of the SMPs; in other words, the crosslinking process during synthesis defines the permanent shape. Although switching segments is flexible and responsive to external stimuli, enabling shape fixation and programming.[ 36 ] The mechanism of most shape memory behaviors is the thermally induced and light‐induced effects.[ 37 ] In general, thermally induced SMPs have at least two separated phases, each with thermal transition (glass or melting) temperatures. The phase with higher Ttrans is responsible for the permanent shape, whereas the phase with lower Ttrans usually acts as a molecular switch for fixation.[ 38 ] In PTLA hydrogel objects, below the glass transition temperature, partial crystalline domains act as switching segments; upon heating over this transition, the object can recover to its permanent shape (Figure 1h13). In sum, these PTLAs exhibit thermally induced one‐way shape memory behavior. Additionally, this hydrogel bioadhesive could be formed in situ by exposing the precursor solution to a UV flashlight within 10 seconds (Figure 1i, Movie S1, Supporting Information), resulting in good stretchability. FTIR was utilized to track the process of hydrogel formation, and the gradual disappearance of peaks at 1615, 860, and 815 cm−1 distinctly proved the absence of the C═C bond after 12 s (Figure 1j). Overall, precise 3D printing techniques allow these PTLAs to be fabricated as versatile and practical bioadhesives in different forms, such as bio‐tapes and bio‐bandages for diverse biomedical tissue adhesion needs (Figure 1k).

2.2. Physical Properties of PTLAs

To optimize the formulations of PTLAs, we modulated the contents of components and photoinitiator and screened them based on their mechanical performance. The resulting hydrogels with different components were defined as PTxLyA, where x (3, 5, or 10) and y (3, 5, or 10) represent the ratios of MTA3 and HPL, respectively. According to stress–strain curves (Figure 2a; Figure S14a, Supporting Information) from universal tensile tests of nine different PTxLyA hydrogels (Table S1, Supporting Information), we opted for PT3L3A, PT5L3A, PT10L3A, PT5L5A, PT5L10A, and polyacrylic acid (PAA, control) for further studies. With an increase of MTA3, the crosslinking degree increased, and PT5L3A shows better mechanical strength and stretchability than PT3L3A. While further increases in crosslinking reduced the hydrogel's elasticity, PT10L3A exhibits a higher Young's modulus but fractures faster under force application compared to PT5L3A. On the other hand, the mechanical performance of PTLAs was reduced with an increase in HPL, as concluded from PT5L3A, PT5L5A, and PT5L10A. A high density of positive amine groups from HPL forms ionic interactions with carboxylic groups, which may compete with chemical crosslinking for rapid gelation, affecting further photopolymerization. Therefore, the increase in ionic interactions due to the higher HPL content results in a less chemically stable hydrogel network, leading to a decrease in mechanical performance and accelerated hydrolytic degradation. Overall, PT5L3A exhibits the most comprehensive mechanical properties, including stress, ultimate strain, Young's modulus, and toughness (Figure 2b), a conclusion similar to that from compression studies (Figure 2e,f). Meanwhile, PT5L3A hydrogels initiated by different ratios (0.3, 0.5, and 1 wt%) of photoinitiator 2,4,6‐trimethylbenzoyldiphenyl phosphine oxide (TPO) were assessed. Although the hydrogel with 0.5% TPO showed an ultimate strain of more than 1000%, we selected the PT5L3A‐1% TPO hydrogel, which exhibited approximately two‐fold (∼ 440 kPa) its stress and about 800% strain (Figure S14b, Supporting Information). Moreover, tension and compression studies of PT5L3A hydrogels at 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, and 70% of the components’ concentrations concluded that their strength is positively related to concentration, with a corresponding decrease in ultimate strain (Figure S14c,d, Supporting Information). Further, the mechanical properties and microstructures of UV‐induced and 3D printed PT5L3A hydrogels (Figure 2c,g) were compared. With 3D printing, significant improvements in mechanical performance (Figure 2d,h) are observed at both 50% and 70% concentrations compared to UV‐induced formed hydrogels; also, the morphology (Figure 2i–l) captured from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) indicates that 3D printing results in a more unified network arrangement with concentrated pore distributions (Figure 2m). For UV‐induced hydrogels, photopolymerization happens in a nonhomogeneous process;[ 39 ] UV light intensity decreases with depth due to absorption and scattering by the materials, which causes uneven initiation and inconsistent polymerization progress. In thicker samples, the surface polymerizes faster, while deeper areas may remain insufficiently polymerized. Thermal effects of polymerization can cause localized thermal gradients that lead to structural inhomogeneities, such as shrinkage and stress. In contrast, 3D printing through layer‐by‐layer additive manufacturing, each layer with controlled thickness (micrometre scale) and light exposure intensity/position that minimizes light attenuation and thermal effects, ensures uniform polymerization and material deposition, resulting in greater microstructural distribution, physicochemical and mechanical properties, and reproducibility.[ 39 ] More in formulations, MTA1 and MTA2 were designed for a comparative study in the stability of hydrogels from covalent and non‐covalent modified tannic acid. PT5L3A‐QI (from MTA1) and PT5L3A‐VI (from MTA2) hydrogels were prepared under the same conditions and studied for biodegradation together with all five PTLAs in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) at 37 °C for 4 weeks. More than 50% of PT5L3A‐QI and 35% of PT5L3A‐VI degraded after 2 weeks compared to 10%–15% degradation of PTLAs from MTA3 (Figure 2n), confirming that higher structural stability was contributed by covalent bonding than ionic interactions. MTA2 contains vinyl groups that can polymerize during hydrogel formation, whereas MTA1 is loaded only via hydrogen‐bonding interactions. After 4 weeks, PT5L3A‐VI and PT5L3A‐QI were degraded by approximately 75% and 90%, respectively, whereas PTLAs were degraded by only about 22%–30%. Then, a swelling study of PTLAs was conducted in PBS at 37 °C, and the samples reached equilibrium with swelling ratios of approximately 200% after 24 h (Figure 2o). The swelling capacities of these hydrogels are negatively correlated with the contents of MTA3 and HPL, depending on the crosslinking density. Following freeze‐tolerance evaluation (Figure 2p) revealed that all PTLAs could maintain their physical features until −31.02 °C. PT5L3A at 50% concentration exhibited a freezing point at −46.11 °C, whereas for 60% and 70% concentrations, no freezing was observed till −90 °C. The concentration‐dependent antifreeze behavior of PT5L3A hydrogels was discussed in Figure S15 (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Physical properties of PTLA hydrogel bioadhesives. Tensile study of PTLAs and PAA, strain rate 40 mm min−1, a) stress–strain curves, b) tensile performance. c) 3D printed rectangular PT5L3A hydrogel objects for tensile tests. d) Stress–strain curves of UV‐induced and 3D printed PT5L3A hydrogels (50% and 70%). Compression study of PTLAs and PAA, compressive rate 1 mm min−1, e) stress–strain curves, f) compressive performance. g) 3D printed cylindrical PT5L3A hydrogel objects for compression tests. h) Stress–strain curves of UV‐induced formed and 3D printed PT5L3A hydrogels (50% and 70%). Comparison studies of (d) and (h) demonstrate a significant mechanical improvement of PTLAs through 3D printing. Morphology analysis by SEM, i) PT5L3A‐50%, j) PT5L3A‐70%, k) 3D printed PT5L3A‐50%, l) 3D printed PT5L3A‐70%, m) comparison of pore distribution in four PTLAs networks, indicating more uniform and ordered porous structures in 3D printed hydrogels. n) In vitro biodegradation of PTLAs at 37 °C over 4 weeks, confirming the higher stability of PTLAs from covalent modification MTA3 compared to non‐covalent modifications MTA1 and MTA2, as well as the biodegradability of all PTLAs. o) Swelling study of PTLAs at 37 °C, showing low to moderate swelling ratios. p) DSC curves of PTLAs, indicating extremely freeze‐tolerance behavior. q) In situ self‐healing process of PT5L3A hydrogel, demonstrating rapid and efficient in situ self‐healing behavior. Rheological studies of PT5L3A hydrogel, r) oscillatory strain sweep between 0.1% and 1000% of strain at a frequency of 1 Hz, s) thixotropic study with a step‐strain sweep of low strain (1%) and high strain (350%), showing superior intrinsic self‐healing capacity and shear‐induced gel–sol transition behavior. t) Schematic illustration of self‐gelling behavior of dried PTLA powder. Self‐gelling studies of PT5L3A powder, u) with PBS, v) with dye water, w) stretching tests of self‐gelled PT5L3A, the outstanding stretchability and flexibility indicate efficient self‐gelling capacity of dried PTLAs powder within 3 min.

Further, an in situ self‐healing process was performed using PT5L3A (40%) as a model hydrogel (Figure 2q); rapid healing occurred within 5 s of applying pressure, and the healed sample showed notable stretchability. As discussed in Figure S14c (Supporting Information), the mechanical properties of PTLAs are highly related to their concentrations. PT5L3As at 30% and 40% concentrations exhibit soft and highly stretchable features, allowing for self‐healing to occur in situ with remarkable healing efficiency. With concentrations increasing to 50%, 60%, and 70%, the hydrogels become stiff, and self‐healing occurs in a time‐dependent manner. The time‐dependent self‐healing behavior of PT5L3As (50%) at healing times of 2, 4, and 6 h was investigated based on their mechanical properties; the stress–strain curves are presented in Figure S16a (Supporting Information). Compared to the original PT5L3A, after 4 h of healing, the stretchability of the healed PT5L3A recovers to approximately 53.24%, and its strength returns to 36.01%. After 6 h, stretchability and strength recover to approximately 74.88% and 54.38%, respectively (Figure S16b, Supporting Information). Furthermore, to track intrinsic self‐healing behavior, the thixotropic study (Figure 2s) was applied under alternative strains of 1% (linear viscoelastic region) and 350% (deformation region), where the strains were determined from the oscillatory strain sweep (Figure 2r). Almost 100% of storage and loss moduli recovered after 2 cycles, indicating well reconstruction of hydrogel networks. In PTLA hydrogel systems, the self‐healing mechanism primarily involves physical interactions, including hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, Π–Π stacking, and thermal effects. During healing, the broken hydrogen bonds between MTA, HPL, AA, and water will reassociate at the damaged zone. Ionic interactions between the positively charged HPL and negatively charged AA will be rebuilt in a short time, as will Π–Π stacking between MTAs. The recovered physical interactions will reconstruct the inter‐chain interactions for crosslinking. Meanwhile, thermal effects from external heating will accelerate the movement of polymer chains, promoting reassociation and crosslinking.[ 8b ] Moreover, as mentioned in Figure 1k, PTLAs can be fabricated into bioadhesives as bio‐bandage and bio‐tape forms, among other applications, for potential biomedical uses. Therefore, the storage of these hydrogel bioadhesives should be considered to prevent water loss and degradation that affect their physical performance. In general, fabricated PTLAs could be packaged in preloaded vials as ready‐to‐use formats or single‐use vacuum sealing packs and stored at 4–8 °C. The formats could be easily fabricated into hydrogel adhesives via UV‐induced crosslinking for in situ applications. Additionally, the single‐use vacuum sealing packaging strategy can help prevent moisture loss; meanwhile, the high content of hydrophilic moieties, such as carboxylic, hydroxylic, and positively charged amine groups, aids in moisture retention. With superior freeze tolerance, storage at low temperatures will not affect the hydrogel's features but may prevent degradation. However, the most practical and economical storage approach is to package them as dry hydrogel patches or powder, which can absorb and remove interfacial water, thereby forming adhesion on wet tissues or organs through a dry cross‐linking mechanism.[ 5a ] Therefore, we evaluated the self‐gelling capacity of dried PT5L3A hydrogel powder (Figure 2t) in the presence of PBS (Figure 2u) and dye water (Figure 2v), respectively. The efficient rehydration and physical crosslinking lead to rapid and controllable self‐gelling within 3 min at 37 °C. Self‐gelled samples exhibit elastic and flexible hydrogel properties, allowing them to be easily reshaped into another form with notable stretchability (Figure 2w).

2.3. In Vitro Biocompatibility and Cell Adhesion/Proliferation on PTLAs

As aforementioned, TA has been involved in the development of many hydrogel adhesives; however, toxicity is the primary concern with free TA. Free TA is highly acidic and toxic to cells. As shown in Figure 3a, TA at a 200 µg mL−1 concentration kills more than 80% of NIH/3T3 fibroblast cells. Hence, in this work, we introduced the methacrylate group into TA to achieve covalent crosslinking via UV to mitigate cytotoxicity. Additionally, Figure 3b demonstrates the highly biocompatible nature of HPL with more than 80% cell viability at 200 µg mL−1. In vitro cell cytotoxicity and morphology experiments, as well as in vivo subcutaneous implantation experiments (discussed later), were performed to evaluate the biocompatibility of the PTLAs. For in vitro cytotoxicity experiments, NIH/3T3 cells were cultured in 24‐well plates for 24 h and then directly treated with 20 mg of PTLAs; the group without treatment served as the control. Cell viability assay was performed using an Alamar Blue reduction kit and Calcein‐AM/Ethidium Homodimer‐1 for live‐dead staining. Results in Figure 3c depict that all PTLAs are biocompatible and exhibit cell viability of more than 80% up to 5 days, with no significant difference compared to control groups on day 3 and day 5. To examine cell morphology, cells fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) were stained with phalloidin and 4′6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize the actin filaments and nucleus. In PTLA groups, cells are well spread and elongated with proper shape, similar to control groups (Figure 3d,e, Figure S17a, Supporting Information). Further, given that TA and HPL have the capacity to promote cell adhesion and proliferation, we conducted a study of NIH/3T3 cell adhesion and proliferation on PTLAs (Figure 3f). Cell behavior on PT5L3A, PT5L5A, and PT5L10A hydrogels with different HPL contents was tracked via live‐dead assay and DAPI/Phalloidin staining. Hydrogel of PT5L3A formulation plus 1% gelatin was prepared as a positive control, in which gelatin has the arginyl‐glycyl‐aspartic acid (RGD) sequences of collagen that are highly effective for cell adhesion.[ 40 ] After 3‐ and 5‐day culture, live cells in multiple layers were observed due to the 3D microstructure of hydrogels, and a Z‐stack was performed for the Day 5 live‐dead assay (Figure 3g,h, Figure S17b,c, Movie S2, Supporting Information). The staining of the nucleus and actin filaments shows that these cells displayed a healthy, elongated shape with an evenly distributed pattern. The live‐dead images and cellular morphology prove the cell‐favorable matrix of PTLAs for fibroblast attachment and proliferation. A higher density of cells is present in PTLAs with increasing HPL, which contributes to a greater α‐PL content, resulting in more effective cell adhesion. The control hydrogel, PT5L3A with 1% gelatin, provides a cell‐favorable nature.

Figure 3.

In vitro biocompatibility, cell adhesion and proliferation on 3D printed hydrogel bioadhesives, and ROS scavenging studies. In vitro cell viability on NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts, a) TA, b) HPL, c) PTLAs, showing concentration‐dependent cell viability of TA and HPL, and non‐cytotoxic nature of PTLAs (direct‐contact). In vitro NIH/3T3 cell live‐dead assay and cellular morphology by direct contact with PT5L3A hydrogel on Day 3 and Day 5, d) control, e) PT5L3A, indicating excellent biocompatible nature. Live‐dead assay scale bar 300 µm, cellular morphology scale bar 150 µm. f) Schematic illustration of NIH/3T3 cell adhesion and proliferation on 3D printed PTLAs. Live‐dead assay and cellular morphology of NIH/3T3 cells on PTLAs on Day 3 and Day 5, g) PT5L3A hydrogel, h) PT5L3A hydrogel with 1% gelatin, showing efficient cell adhesion and proliferation, as well as healthy morphology. Live‐dead assay scale bar 300 µm, cellular morphology scale bar 150 µm. i) Peroxidase activity assay for ROS scavenging studies, TMB and GSH were studied as positive and negative controls, respectively. j) DCFDA assay for intracellular ROS scavenging studies, indicating superior ROS scavenging capabilities of TA, HPL, and PTLAs, scale bar 300 µm. Statistical Analysis: Two‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, and *, **, ***, **** were considered for p values <0.05, <0.01, <0.001, and <0.0001, respectively.

2.4. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of PTLAs

As discussed in the introduction, polyphenolic compound TA and positively charged HPL are well known for their ROS scavenging and bactericidal capacities. In this work, we have developed hydrogel bioadhesives with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, enabling safer and more effective wound management while achieving hemostasis. The antioxidant properties of PTLAs were assessed through their ROS scavenging capacity using peroxidase ‐ like activity assay and in vitro intracellular dichloro‐fluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) assay. In the peroxidase ‐ like activity assay (Figure 3i), 3,3,5,5‐tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was used as a probe to monitor the ROS scavenging activity, which could shift from colorless to blue oxidation color by interacting with ROS radicals.[ 41 ] Glutathione (GSH) is a well‐known antioxidant agent that has been studied as a positive control.[ 42 ] Minimal color change was observed in test groups as GSH, and the calculation from absorbance curves revealed that more than 99% of ROS radicals were quenched by TA and PTLAs, and approximately 95% by HPL. Moreover, the intracellular ROS scavenging properties of TA, HPL, and PT5L3A hydrogel were evaluated via DCFDA assay using hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a ROS‐generating agent (Figure 3j). The intracellular non‐fluorescent DCFDA could be oxidized by ROS and converted into detectable fluorescent 2,7‐dichlorofluorescein (DCF). From fluorescence microscopy, the control, GSH, TA, HPL, and PT5L3A‐treated groups exhibited negligible fluorescence compared to the intense fluorescence in the H2O2 group. Both results demonstrate the extensive ROS scavenging capabilities of TA, HPL, and PTLAs as designed.

Further, the broad‐spectrum antimicrobial performance of PTLAs was investigated using colony formation and live‐dead assays against the gram‐negative bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli) and the gram‐positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis), which is known as a model organism for studying biofilm formation.[ 43 ] As shown in Figure 4a and Figure S18a,b (Supporting Information), the absence of bacterial colony with no bacterial growth of E. coli and B. subtilis after direct contact on the hydrogels’ surface indicates an effective bactericidal nature of these hydrogels; a time‐dependent study concludes that PT5L3A hydrogel can efficiently kill both bacteria in 15 min. Fluorescence microscopic images (Figure 4b, Figure S18c, Supporting Information) from the live‐dead assay show uniform fluorescent cells in control groups, while orange/yellow (merge of green and red channels) cells were observed in hydrogel‐treated groups, reflecting membrane damage and cell death. This observation was further examined by SEM imaging; the bacterial cells displayed a smooth morphology with intact shape in control groups, whereas the hydrogel‐treated cells appeared in a rough, crumpled, ruptured, and collapsed morphology (Figure 4c). PTLAs with higher HPL contents resulted in more destructive cellular damage (Figure S18d, Supporting Information). Furthermore, 3D views of these bacterial cells were produced by high‐resolution atomic force microscopy (HR‐AFM). AFM has emerged as a precise in situ tool to visualize the 3D topographical data of individual bacteria at the nanoscale with unprecedented resolution, revealing surface details and cell integrity.[ 44 ] Figure 4d shows representative vivid 3D topographical images of control and hydrogel‐treated bacteria; the surface profiles of identified bacteria cells were obtained by cross‐section measurement (Figure 4e). Profile curves with a flat plateau of control bacteria confirm no apparent indentation and grooves on cell surfaces, while profile curves with undulation and dramatic height differences of treated bacteria verify significant changes of their surface topography. In more detail, the violin plots (Figure 4f) and a bar graph (Figure 4g) compute 45 individual bacteria from each group, indicating that PT5L3A treatment resulted in a statistically significant increase in bacterial surface roughness (Rq) and a decrease in bacterial cell height (H), with a large deviation. PT5L3A treated E. coli (Rq = 34.38 ± 18.97 nm, H = 147.34 ± 70.96 nm; n = 45), compared to control E. coli (Rq = 10.42 ± 4.97 nm, H = 365.33 ± 42.82 nm; n = 45); PT5L3A treated B. subtilis (Rq = 24.01 ± 10.25 nm, H = 212.06 ± 89.63 nm; n = 45), compared to control B. subtilis (Rq = 8.43 ± 4.21 nm, H = 360.08 ± 58.58 nm; n = 45). Finally, the antibiofilm capacity of PT5L3A hydrogel was evaluated using a crystal violet (CV) assay and SEM imaging. Biofilm is defined as a highly structured, surface‐associated microorganism community that exhibits distinct metabolic and physiological differences compared to planktonic brethren, significantly reinforcing the resistance to antimicrobial agents.[ 45 ] In this study, both control E. coli and B. subtilis bacteria formed uniform and dense biofilms under static conditions after 48 h, while no bacteria and biofilm were observed on the PT5L3A hydrogel surface (Figure 4h). Meanwhile, biofilm formation in control and hydrogel‐containing external environment was evaluated by CV assay, significant differences were detected in biofilm mass (Figure 4i), as well as from brightfield images (Figure 4j). Both results firmly clear the remarkable capacity of PT5L3A hydrogel for preventing biofilm formation.

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial and antibiofilm study of hydrogel bioadhesives. a) Colony formation assay of all PTLAs treated bacteria (gram‐negative E. coli and gram‐positive B. subtilis) after 4 h, and time‐dependent (15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 2 h, and 4 h) antibacterial capability of PT5L3A hydrogel, showing the absence of bacterial colony after treatment. b) Live‐dead assay fluorescent images of control and PT5L3A hydrogel‐treated E. coli and B. subtilis, indicating bacterial death after treatment, scale bar 75 µm. c) SEM morphology study of control and PT5L3A hydrogel‐treated E. coli and B. subtilis, exhibiting collapse and rupture of the bacterial membrane after treatment, scale bar 1 µm. Non‐contact HR‐AFM surface study of control and PT5L3A hydrogel treated E. coli and B. subtilis, d) representative 3D images, scale bar 1 µm, e) surface profiles of marked bacteria in (d), f) surface roughness (Rq), g) Z‐position (bacterial height H), the Rq and H were calculated from the central 40% of individual bacterial surface profile, resulted standard deviation represents the Rq and average mean represents the H, n = 45 for all the groups. The AFM results strongly indicate a significant change in the surface roughness of bacteria after treatment. Antibiofilm studies of PT5L3A hydrogel against E. coli and B. subtilis, h) SEM images of biofilm formation of control and on the hydrogel, scale bar 5 µm. Crystal violet (CV) assay for antibiofilm studies in control and hydrogel‐containing external environment, i) biofilm mass, j) brightfield images of CV‐stained biofilm, scale bar 75 µm. In sum, PTLAs could kill bacteria and prevent bacterial biofilm formation. Statistical Analysis: One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, and *, **, ***, **** were considered for p values <0.05, <0.01, <0.001, and <0.0001, respectively.

2.5. Ex Vivo Tissue Adhesion and Burst Pressure Studies of PTLAs

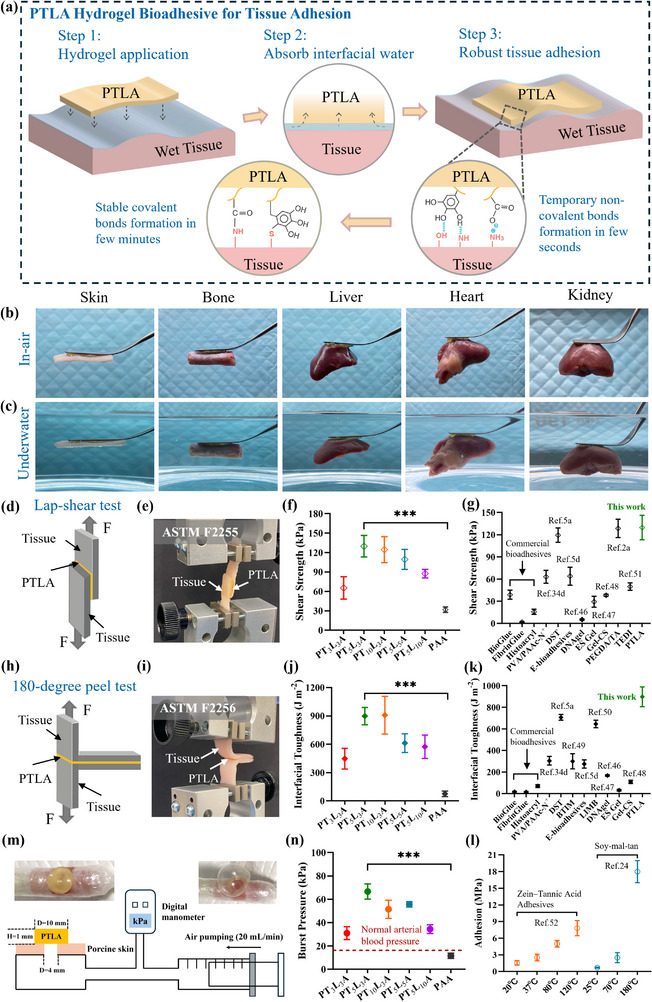

Inspired by the robust adhesion performance of natural molluscs (Figure 1a), in this work, we employed catechol‐rich polyphenol TA, positively charged HPL, and anionic AA for the design of bioadhesives. Figure 5a illustrates the application and mechanism of PTLA hydrogel for tissue adhesion. The PTLAs will absorb interfacial water whenever applied to a wet tissue surface; temporary non‐covalent bonds, such as hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions, form within a few seconds at the interface, followed by stable covalent bond formation in a few minutes to achieve robust tissue adhesion. Digital images exhibit the adhesion capacities of PT5L3A hydrogel against various animal tissues and organs, such as porcine skin, porcine bone, chicken liver, chicken heart, and lamb kidney, in the air (Figure 5b) and underwater (Figure 5c). Particularly, the robust adhesion took place underwater between PTLAs and tissue surfaces that enable to lift them (Movie S3, Supporting Information). To quantitatively assess the adhesive strength, we performed the standard lap‐shear test (ASTM F2255, Figure 5d,e, Movie S4, Supporting Information) and 180‐degree peel test (ASTM F2256, Figure 5h,i, Movie S5, Supporting Information) of PTLAs against porcine skin; PAA was tested as a control. Significant improvements in shear strength (Figure 5f) and interfacial toughness (Figure 5j) were achieved in PTLAs compared to PAA. Meanwhile, the adhesive strength of PTLAs depends on the MTA and HPL contents and highly relies on their mechanical performance, the energy dissipated by hysteresis. In PT3L3A, PT5L3A, and PT10L3A, both shear strength and interfacial toughness are positively related to MTA ratios; while in comparison of PT5L3A, PT5L5A, and PT5L10A, the adhesive strengths are consistent with their mechanical property trends (Figure 2a). In comparison to commercial tissue bioadhesives bio‐glue, fibrin glue, and histoacryl,[ 5b ] and recently reported bioadhesives PVA/PAAc‐N+,[ 34d ] DST,[ 5a ] E‐bioadhesives,[ 5d ] DNAgel,[ 46 ] ES Gel,[ 47 ] Gel‐CS,[ 48 ] PEGDA/TA,[ 2a ] BTIM,[ 49 ] LIMB,[ 50 ] and TEDI,[ 51 ] the PT5L3A hydrogel bioadhesive exhibits promising tissue adhesion capacities with a shear strength of 129.81 ± 16.64 kPa and interfacial toughness of 897.87 ± 91.27 J m−2 (Figure 5g,k). The robust tissue adhesive performance of PTLAs from rich non‐covalent hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions, and covalent amide and sulfide bonds formed between phenolic hydroxyl, carboxylic, and positively charged amine groups of bioadhesives and tissue surfaces (Figure 5a). Moreover, PTLAs are composed of chemically crosslinked methacrylate tannic acid MTA3 that contributed to excellent mechanical properties as well as tissue adhesiveness. As discussed in the introduction, this design that chemically crosslinks the tannic acid for improving adhesive performance was inspired by the state‐of‐the‐art adhesive soy‐mal‐tan reported by Westerman et al.,[ 24 ] which exhibited a leading adhesive performance among tannic acid‐based adhesives. Importantly, soy‐mal‐tan adhesive shows further significantly enhanced adhesion capacities with temperature increase (Figure 5l); a similar conclusion can be obtained from another chemically crosslinked zein‐tannic acid adhesive.[ 52 ] Further, the burst pressure of PTLAs and hydrogels adhered to punctured porcine skin was evaluated using an artificial device (Figure 5m). For tissue adhesion, especially hemostasis, the adhesives are required to rapidly adhere to the wound and stanch bleeding, which will challenge not only their capacity to seal the rupture via wet adhesion but also to withstand blood pressure.[ 53 ] Burst pressure tests are efficiently relevant to assessing the pressure‐resisting capacity of bioadhesives. In this study, like adhesive strength, a significant difference in burst pressure was observed between PTLAs and PAA (Figure 5n, Figure S19, Supporting Information). For PTLAs, the pressure‐resisting ability is closely related to mechanical performance trends; the burst pressure of hydrogels adhered to porcine skin is generally lower than that of hydrogels themselves, which may be attributed to the slight adhesion failure before reaching the hydrogels’ burst pressure. However, the pressure of the biosystems won't reach that level. As seen in Figure 5n, all samples with burst pressures exceeding the normal arterial blood pressure can be safely applied for hemostasis.

Figure 5.

Ex vivo tissue adhesion and burst pressure studies of 3D printed hydrogel bioadhesives. a) Schematic illustration of PTLAs for tissue adhesion. Digital images of PT5L3A hydrogel adhering to porcine skin, porcine bone, chicken liver, chicken heart, and lamb kidney, showing robust tissue adhesion performance, b) in air, c) underwater. Tissue adhesive strength of PTLAs against porcine skin, d) illustration of lap‐shear test model, e) setup for measurement of shear strength, f) shear strength of PTLAs and control PAA, g) comparison of shear strength between PTLAs, commercial tissue bioadhesives, and recently reported typical bioadhesives, such as PVA/PAAc‐N+,[ 34d ] DST,[ 5a ] E‐bioadhesives,[ 5d ] DNAgel,[ 46 ] ES Gel,[ 47 ] Gel‐CS,[ 48 ] PEGDA/TA,[ 2a ] and TEDI,[ 51 ] h) illustration of 180‐degree peel test model, i) setup for measurement of interfacial toughness, j) interfacial toughness of PTLAs and control PAA, with shear strength results together indicate a significant improvement of adhesive properties of designed hydrogel bioadhesives by introducing MTA3 and HPL, k) comparison of interfacial toughness between PTLAs, commercial tissue bioadhesives, and recently reported bioadhesives, such as PVA/PAAc‐N+,[ 34d ] DST,[ 5a ] BTIM,[ 49 ] E‐bioadhesives,[ 5d ] LIMB,[ 50 ] DNAgel,[ 46 ] ES Gel,[ 47 ] and Gel‐CS,[ 48 ] with shear strength results together demonstrating the leading tissue adhesive capabilities of PT5L3A hydrogel. l) Adhesive performance of reported state‐of‐the‐art tannic acid‐based adhesives,[ 24 , 52 ] adhesion capacities were improved with temperature increase. Burst pressure tests, m) schematic illustration of burst adhesion experimental procedure, snapshot images of before and after tests show promising ductility of PT5L3A hydrogel and its notable adhesive properties against porcine skin, n) burst adhesion pressure of PTLAs and PAA, significantly higher than normal arterial blood pressure demonstrate potential capabilities of PTLAs for hemostasis. Statistical Analysis: One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, and *, **, ***, **** were considered for p values <0.05, <0.01, <0.001, and <0.0001, respectively.

2.6. Ex Vivo Sealing, In Vivo Hemostasis, and In Vivo Biocompatibility Studies of PTLAs

Uncontrollable bleeding or hemorrhage during injury and surgery causes numerous deaths.[ 54 ] Previous ex vivo studies have revealed the leading wet tissue adhesion and pressure resistance of designed PTLAs. Here, we further evaluate their sealing and hemostasis capacities. First, we performed the ex vivo sealing test on a fresh lamb brain (Figure 6a), where the hydrogel patch was immediately adhered over the damaged tissue with mild pressing for 3–5 s (Figure 6b). To assess the sealing ability under water and high arterial pressure, we conducted an air‐leaking lung sealing experiment in a water bath (Figure 6c, Movie S6, Supporting Information). After hydrogel fixation (press for 3–5 s) over the damaged area of the lung lobe, no leakage was observed under water with continuous airflow. Ex vivo experiments suggest that these PTLAs are highly capable of stopping leakages and hemostasis. A real‐time in vivo hemostasis study (Figure 6d) further supported this conclusion. Before hemostasis, we assessed their hemocompatibility, a highly desirable feature for sealable hydrogel adhesives. The hemolysis results demonstrated that PTLAs are compatible with human blood (Figure 6e,f) (ISO document 10 993–5 1992). Then, the hemostasis evaluation of PT5L3A hydrogel was performed on the live rat liver in comparison to gauze and a commercial bioadhesive hydrocolloid dressing (HD), with the group without treatment serving as a control. In rat liver surgery tests, bleeding was induced by creating a 4 mm‐depth trauma on the right lobe, then test items were adhered to the bleeding site and held in situ with mild pressure for 5 s. As expected, continuous bleeding was observed in the control and gauze groups (Figure 6g,h) after 120 s, while PT5L3A halted bleeding immediately (Figure 6j, Movie S7, Supporting Information). However, for commercial HD, tissue adhesion failed in the presence of blood, and bleeding continued after 120 s (Figure 6i). Overall, PT5L3A bioadhesive exhibited the most efficient hemostasis capacity with minimum hemostatic time (Figure 6k) and minimal blood loss (Figure 6l) in significant differences compared to other groups. This conclusion was further proved by in vivo adhesion examination, where PT5L3A robustly adhered to the bleeding site and enabled full lift of the whole liver (Figure 6n,o), while commercial HD was easily detached from the tissue surface (Figure 6m). Moreover, the hemostasis capacity of PT5L3A bioadhesive was assessed on a more challenging live rat heart (Figure S20a,b), where the bleeding stopped after 20–30 s mildly press (Figure S20c, Supporting Information), and resulted in remarkable adhesion also could lift the heart (Figure S20d,e, Supporting Information). Moreover, Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) staining results of the liver (Figure S20f, Supporting Information) and heart (Figure S20g, Supporting Information) after hemostasis reveal distinct hemocyte aggregation at incision sites.

Figure 6.

Ex vivo sealing, in vivo hemostasis, and biocompatibility studies of 3D printed hydrogel bioadhesives. a) Schematic illustration of ex vivo sealing applications. b) PT5L3A sealing damaged lamb brain in air, showing notable adhesion on the wet brain surface. c) PT5L3A sealing damaged lamb lung lobe underwater, demonstrating robust adhesion to the lung surface under water and pressure. In vivo hemostatic evaluation of PT5L3A bioadhesive on rat liver, d) schematic illustration, e,f) hemolysis study of PTLAs against human blood, indicating excellent blood compatibility. Hemostasis performance on live rat liver within 120 s, g) control group without treatment, h) gauze, i) commercial HD, j) PT5L3A, k) hemostatic time, l) blood loss, clearly indicating the remarkable hemostatic performance of PT5L3A with minimum hemostatic time and minimal blood loss. In vivo tissue adhesion examination, m) commercial HD, n,o) PT5L3A. In vivo biocompatibility study of PT5L3A, p) schematic illustration and study process, q) Day 1, r) Day 8, s) Day 15, H&E staining images of rat skin, t) control day 8, u) PT5L3A day 8, v) control day 15, w) PT5L3A day 15, all the images with same scale bar of 200 µm. Statistical Analysis: One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, and *, **, ***, **** were considered for p values <0.05, <0.01, <0.001, and <0.0001, respectively.

Furthermore, in vivo biocompatibility studies (Figure 6p) were performed to validate the biocompatible nature (from the in vitro study) of PTLAs. 10 mm PT5L3A hydrogel discs were implanted into the subcutaneous tissue of 9‐week‐old rats (Figure 6q), and skin tissues were collected at day 8 (Figure 6r) and day 15 (Figure 6s) for histological evaluation. After 7 and 14 days, no abnormal depression, agitation, or anorexic behaviors were observed in the test groups’ rats. The body weights of all experimental rats increased slightly, with no significant difference between the test and control groups (Figure S21a, Supporting Information). Results of the H&E staining demonstrate that PT5L3A hydrogel induced a moderate range of inflammatory response, causing infiltration of immune cells at hydrogel sites, but no major damage and necrosis to the surrounding dermal and muscle layer was observed (Figure 6u,w). After 14 days, encapsulation of the affected hydrogel area with increased blood vessels and the onset of the capsule of granulation tissue, comprised of collagen and fibroblasts, were observed, suggesting adaptive tissue‐hydrogel reactions.[ 55 ] Control group rat skin samples exhibit minimal cellular inflammation, composed mostly of lymphocytes, an increased number of blood vessels, and a fine capsule around the affected area (Figure 6t,v). Meanwhile, clinically used fibrin bioadhesive has been reported to induce a mild chronic inflammatory infiltration containing plasma cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages, as observed in an in vivo study.[ 56 ] On the other hand, the inflammatory response of the PTLAs may be attributed to in vivo biodegradation, which subsequently affects the surrounding placement site of the hydrogel, causing infiltration of immune cells and phagocytic cells,[ 57 ] similar to reported chitosan‐ and gelatin‐based bio‐tape DST.[ 5a ] Developed PTLAs composed of modified tannic acid, polyacrylic acid, and hyperbranched polylysine are biodegradable with time through different mechanisms, including hydrolysis and enzyme‐assisted degradation. The enzymatic biodegradation of tannic acid and TA‐based hydrogels by esterases and tannase produces gallic acid and glucose,[ 58 ] which can be further metabolized by the body.[ 59 ] Chemically crosslinked TA‐based hydrogel PTLAs were designed to achieve slower biodegradation compared to physical crosslinking, thereby preventing the in‐situ accumulation of byproduct gallic acid. Polyacrylic acid is widely used as a platform in drug delivery, tissue engineering, biosensors, and other biomedical applications,[ 5 , 34 , 56 , 60 ] thanks to its biocompatible nature.[ 61 ] Copolymerized polyacrylic acid can be degraded via hydrolysis, oxidative degradation, and enzyme‐assisted degradation,[ 61 , 62 ] producing small organic acids, water, and CO2, which are non‐toxic and can be metabolized or excreted by the body.[ 61b,c ] Moreover, polycationic polylysine is well‐known and used for cell encapsulation and transplantation; however, it can provoke inflammatory responses due to high cationic charge, as reported,[ 63 ] similar to chitosan.[ 64 ] Therefore, physically crosslinked hyperbranched polylysine in PTLAs could be released first during hydrogel biodegradation and induce the foreign body response at the initial stage of implantation, as observed from H&E staining results. However, this response can be mitigated through further biodegradation.[ 65 ] The biodegradation of polylysine primarily occurs through enzymatic hydrolysis by peptidases into lysine and other non‐toxic amino acids, which can be metabolized by the body.[ 66 ] To further confirm in vivo biodegradation, the implanted hydrogels were collected at each termination, and their mechanical properties and micromorphology were investigated. As shown in Figure S21b (Supporting Information), the ultimate compressive strain at break of implanted PT5L3A after 7 days decreased to approximately 89% of the original hydrogel, and that of implanted PT5L3A after 14 days reduced to approximately 83%. In addition, compared to PT5L3A before implantation (Figure S21c, Supporting Information), the micromorphology of implanted PT5L3A on day 8 (Figure S21d, Supporting Information) and day 15 (Figure S21e, Supporting Information) reveals an increase in pore size, accompanied by partial disconnection of the networks. Both results indicate the in vivo biodegradation of PTLAs after implantation.

3. Discussion and Conclusion

Here, we report several biomimetic adaptive hydrogel bioadhesives (PTLAs) for challenging tissue adhesion, hemostasis, and healthcare. It is noteworthy that these PTLAs, composed of UV‐sensitive methacrylate‐modified tannic acid, hyperbranched polylysine, and acrylic acid, were fabricated via high‐resolution 3D printing. This precise fabrication technique allows for on‐demand personalized designs compared to traditional bulk preparations, significantly saves time and minimizes waste, and controlled thickness and distribution ensure consistent quality across batches. Meanwhile, 3D printed PTLAs exhibit programmable thermally induced one‐way shape memory capacity, which attracts eyes for potential active medical applications. For example, they could be fabricated to on‐demand implanted devices (as potential bioadhesives and/or other implants) and inserted into the body as temporary shapes in smaller sizes by minimally invasive surgery (MIS), then memorized into permanent shapes encoded with temperature changes, as reported by Lendlein and Langer.[ 67 ] Similar to light‐induced SMPs, Small et al. designed a laser‐activated shape memory device and placed it into a blood vessel via MIS, which coiled into the permanent shape upon laser activation, and then mechanically removed the blood clot.[ 68 ] Additionally, UV‐induced ultrafast formation within 10 s allows these bioadhesives to be prepared on‐site or in situ and applied to limited and irregular locations.

In addition to fabrications, PTLAs are designed to improve tannic acid stability and mitigate the toxic issues of TA‐based bioadhesives, with enhanced mechanical and adhesive performance. Inspired by natural mussels and snails, these biomimetic designs address the limitations of challenging tissue adhesion through the incorporation of rich catechol groups and ionic interactions. Temporary non‐covalent bonds form in a few seconds between adhesives and tissue surfaces, such as hydrogen bonding between the phenolic hydroxyl group, normal hydroxyl group, and primary amine, as well as ionic interactions between carboxylic and positively charged amine groups. These temporary bonds lead to the formation of ultrafast tissue adhesion. With the increase of time, stable covalent bonds such as amide between carboxylic and amine groups, and sulfide between thiol and polyphenol, are formed, which further ensure robust tissue adhesiveness. Therefore, PTLA bioadhesives demonstrate remarkable tissue adhesion, sealing, and hemostasis capabilities in challenging wet, underwater, and pressurized environments, as validated by ex vivo and in vivo models.

Furthermore, these PTLAs could simultaneously seal wounds and prevent infections, thereby avoiding oxidative damage and various inflammations that could lead to risks of wound tissue adhesion, scar tissue formation, prolonged wound healing, and even chronic diseases. Additionally, PTLAs provide a cell‐favorable matrix for fibroblast adhesion and proliferation. The cell‐favorable nature suggests the cell therapy potential of cell‐laden PTLAs, as well as the gene therapy potential of miRNA‐laden PTLAs for enhanced wound management through local immunomodulation. These are attributed to their inherent biological properties, which inhibit bacterial growth to prevent biofilm formation and scavenge free radicals for controlling wound infection and inflammation by polyphenol and hyperbranched polylysine, rather than those bioadhesives incorporating bioactive agents such as drugs[ 69 ] and nanocomponents.[ 70 ] These components play crucial roles in modulating biological functions, adhesion, and other physical properties, such as mechanical performance, freeze resistance, in situ self‐healing, and self‐gelling of PTLAs. Unlike commercially available bioadhesives such as bio‐glue, fibrin glue, histoacryl, etc., which suffer from weak mechanical strength,[ 5b ] limited wet surface adhesion, and insufficient biofunctions.[ 4a ] Moreover, these PTLAs feature superior freeze resistance (no freezing until ‐90 °C), providing solutions for hemostasis challenges of using hydrogel bioadhesives in extremely cold environments. Additionally, the self‐gelling property facilitates in situ dry powder application; the powder can absorb tissue surface water or body fluids, and efficient physical crosslinking leads to rapid self‐gelling at body temperature, forming hydrogel bioadhesives. Self‐gelled adhesives exhibit elastic and flexible hydrogel properties, ensuring in situ tissue adhesion, sealing leakages, and for hemostasis. Therefore, instead of conventional sealing packages and low‐temperature storage of hydrogel adhesives, the self‐gelling ability of PTLAs is practically essential for long‐term product storage in dry hydrogel patch or powder at room temperature; meanwhile, notable antioxidant capacity could prevent oxidative damage and degradation. Although in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility studies reveal the nontoxic nature of PTLAs, and ex vivo and in vivo models show possible applications, we note that their long‐term biodegradation and biocompatibility, as well as the biological response, should be further examined. Additionally, tuning physicochemical properties based on components as well as photoinitiators would be valuable.

In conclusion, these tissue‐like 3D printed PTLAs offer significant advantages compared to commercial and recently reported representative bioadhesives, including practical and precise fabrication techniques, exceptional tissue adhesion under challenging conditions, advanced biological functionalities, and adaptive physical features. All‐in‐one PTLAs pave the way for improved tissue adhesion, hemostasis, and healthcare, presenting transformative potential as bio‐tapes, bio‐bandages, bio‐sealants, bio‐carriers, etc., and setting the stage for next‐generation bioadhesives design.

4. Experimental Section

All details of materials, monomer preparations, characterizations, and additional data are provided in the supplementary information.

Preparation of PTLAs (In situ, UV‐Induced Polymerization, 3D Printing)

PTLAs were fabricated by UV‐initiated photopolymerization. Modified tannic acid (MTAs, 3, 5 or 10 wt%), hyperbranched polylysine (HPL, 3, 5 or 10 wt%), and acrylic acid (AA) were dissolved in deionized water (DW, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 wt%, respectively), 2,4,6‐trimethylbenzoyldiphenyl phosphine oxide (TPO, 0.3, 0.5, and 1 wt%, respectively) was used as photoinitiator.

In Situ Ultrafast Hydrogel Formation: The precursor solution was prepared and exposed under a UV flashlight (395 nm) for 10 s; meanwhile, the process was tracked by in situ FTIR.

UV‐Induced Hydrogel Formation: The robust hydrogels were prepared by exposing the precursor solution under a UV chamber (36 W, Ultraviolet Radiation Lamp, DR‐301C) for 30 min (thickness 0.1–1 mm; increasing thickness requests more polymerization time); the obtained samples were used for later characterization, mechanical, rheological, antifreeze, self‐healing, antimicrobial, etc. studies.

3D printing: The designed objects were printed from precursor solution using a digital light processing (DLP) printer (Asiga Max X, 385 nm, layer thickness 0.01–0.1 mm, light intensity 25 mW cm−2, exposure time 1.5 s), and the object's STL files were generated using SolidWorks software and further processed with Asiga Composer software. Subsequently, 3D printed objects were extracted and cleaned using ethanol and PBS and further cured under an Asiga post‐curing UV chamber for 10–30 min (depending on the thickness) for later mechanical, swelling, biodegradation, shape memory, cell culture, tissue adhesion, and ex vivo/in vivo studies.

PTLAs consisting of MTA1, HPL, and AA were named PTxLyA‐QI; PTLAs consisting of MTA2, HPL, and AA were named PTxLyA‐VI; and PTLAs consisting of MTA3, HPL, and AA were named PTxLyA; where x (3, 5, or 10) and y (3, 5, or 10) are the different ratios of MTA and HPL, respectively.

Swelling Study

Different freshly prepared PTLAs (W0 ) were immersed in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, 30 mL) and kept at 37 °C; the weight of each sample was recorded at regular intervals until it reached a constant value (W1 ). The swelling ratio (±SD, n = 3) was calculated as Equation 1:

| (1) |

In Vitro Biodegradation Study

Different dried PTLAs (W0 ) were immersed in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, 30 mL) and incubated (37 °C, 50 RPM) for a certain time; then, the liquid phase was removed, and the weight (W1 ) of each sample was recorded after lyophilization (CHRIST Alpha 2–4 basic lyophilizer). The biodegradation of PTLAs (±SD, n = 3) was calculated as Equation 2:

| (2) |

Mechanical Study

The mechanical properties study of PTLAs was conducted on a Universal Materials Testing Machine (50 N load cell, EZ‐LX, SHIMADZU) at room temperature (±SD, n = 3), following the standard methods ASTM D638 and ASTM D695 for tensile and compression tests, respectively, with modifications. Silicon oil was used to prevent moisture loss in the samples. For tensile testing, the hydrogel sample was freshly prepared to a size of 30 × 7 × 0.5 mm3 (length × width × thickness) and placed in the grips of the testing machine. Then, the load was applied until the specimen fractured at a tensile rate of 40 mm min−1. According to the stress–strain curve, tensile strength and strain were directly obtained. Young's modulus was equal to the slope of the linear elastic region, and tensile toughness was equal to the area under the curve. For compression, a cylindrical hydrogel sample was freshly prepared to a size of Ø10 × 7 mm2 (diameter × height) and placed in the middle of two compression platens. Then, the load was applied until the specimen fractured at a compressive rate of 1 mm min−1. The compressive strength and strain were directly obtained from the stress–strain curve; compressive stiffness was equal to the slope of the linear elastic region, and compressive toughness was equal to the area under the curve. In situ self‐healing process was performed using 40% PT5L3A as freshly prepared. Quantitative self‐healing behavior was evaluated through the mechanical properties using 50% PT5L3A. A freshly prepared cylindrical ribbon sample (Ø 6 × 30 mm2) was cut into two segments, then reassembled and set at 37 °C for 2, 4, and 6 h, respectively. After each time point, the mechanical properties of healed samples were examined by tensile tests at a strain rate of 40 mm min−1, and stress and strain recovery were compared to the original samples.

Rheological Study

Rheological studies of PTLAs were conducted on Anton Paar MCR 92 Rheometer (20 mm cone plate) at 25 °C. A strain sweep (strain: 0.01%–1000%; frequency: 1 Hz) was performed to detect the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) and deformation of the hydrogels under gradually increased strain application. Then, a frequency sweep (strain: 1%; frequency: 0.1–100 rad s−1) was conducted to assess the viscoelastic behavior. Further, the thixotropy test was performed via step‐strain sweep measurements (alternative application of strain 1% and 350%; 60 s for each cycle; frequency: 1 Hz) to evaluate intrinsic self‐healing capacity.

In Vitro Cytocompatibility Study

The cytocompatibility of the different hydrogels was evaluated using a direct‐contact model[ 60c ] between cells and the hydrogel. The NIH/3T3 cells were seeded into 24 well plates at 3 × 104 cells (Countless II automated cell counter, Thermo Fisher Scientific) per well containing the complete culture media (DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin, and 1% (v/v) amphotericin‐b solutions) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Before the treatment, as‐synthesized PTLAs (PT5L3A, PT5L5A, and PT5L10A) were washed with PBS for 1 day to remove any unreacted traces of monomers. Then, washed hydrogels were placed into the cultured cell wells and incubated for another 1, 3, and 5 days, respectively. At the same time, cells in fresh complete culture medium served as the control (±SD, n = 3).

Cell viability was determined via Alamar Blue assay on Day 1, Day 3, and Day 5. Treated NIH/3T3 cells were incubated in culture media containing 1 mg mL−1 dye for 3 h; then, the fluorescence intensity was measured at 560/590 nm (Biotek Synergy H1F1 Plate reader). The cell viability was calculated as in Equation 3:

| (3) |

Live‐dead assay (LDA) was performed to qualitatively evaluate cell viability after hydrogel treatment. Treated NIH/3T3 cells were stained with Calcein‐AM and ethidium homodimer‐1 (live‐dead cell staining kit) for 30 min. After staining, the cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (EVOS 5000 Thermo Fisher Scientific).

To visualize the F‐actin arrangement, treated NIH/3T3 cells were fixed with 3.7% methanol‐free paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 15 min, and 0.1% Triton X‐100 was used to permeabilize the cell membrane for another 15 min; after washing with PBS, the cells were stained with 10 µg mL−1 Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin for 30 min and colored with 1 µg mL−1 of 4,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min. Finally, the stained cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (EVOS 5000 Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell Adhesion and Proliferation on Hydrogel Study

As prepared PTLAs (PT5L3A, PT5L5A, PT5L10A, and hydrogel PT5L3A+1% gelatin was prepared as control) were washed and placed over the 24 well plates (bottom covered by vacuum grease, DOW CORNING); then, NIH/3T3 cells (4 × 104) with completed culture media were seeded over the hydrogels and incubated for 3 and 5 days, respectively. After incubation, the media were removed, and the hydrogels were stained for live‐dead cell viability evaluation and cellular morphology study. For the live‐dead assay, hydrogels containing cells were stained with Calcein‐AM and ethidium homodimer‐1 (live‐dead cell staining kit) for 1 h. For the cellular morphology study, hydrogels containing cells were fixed with 3.7% PFA solution for 45 min and 0.1% Triton X‐100 for another 10 min; after washing with PBS, stained with 10 µg mL−1 Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin for 45 min and colored with 1 µg mL−1 of 4,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) for 10 min. Lastly, the stained cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (EVOS 5000 Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Peroxidase Activity Assay

The peroxidase activity was determined by a colorimetric assay using 3,3′,5,5′‐tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) as a substrate, which generates a blue color in the presence of ROS radicals. Sodium acetate buffer (pH = 4.8, 400 µL), different antioxidant materials (TA: 1.5 mg mL−1; HPL: 5 mg mL−1; PTLAs: 50 mg mL−1; GSH: 1.5 mg mL−1), DW (200 µL), and H2O2 (30%, 50 µL) were mixed, and FeCl3 (30 mg mL−1, 20 µL) was used to generate radicals. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, TMB (400 µL) was added and shaken for another 30 min. Photographs were taken, and the absorbance of each sample was further read in a range of 400–800 nm (TMB absorbance at 650 nm) using a Biotek Synergy H1F1 plate reader. The ROS scavenging properties of the antioxidant materials were analyzed and compared based on the areas under the absorbance curves.

Intracellular ROS Scavenging

The intracellular ROS scavenging study was performed according to previous reports with certain modifications.[ 71 ] NIH/3T3 cells (3 × 104) were seeded into 24‐well plates containing complete culture media and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. To the cultured plate, different antioxidant materials (TA: 50 µg mL−1; HPL: 100 µg mL−1; PT5L3A hydrogel: 20 mg; GSH: 750 µg mL−1) were pretreated, respectively, and incubated for 1 h, followed by the addition of H2O2 (1 mM). The group without antioxidant material but with H2O2 treatment and the group without any treatment were defined as controls. After incubation for 45 min, the materials and media containing H2O2 were removed, and the wells were washed with PBS. Then, each group, including controls, was stained with DCFDA solution (30 µm in culture media, 200 µL) and incubated in the dark for 40 min. After staining, the excess DCFDA was removed, and the cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (EVOS 5000 Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antimicrobial Study

The antimicrobial activities of PTLAs were evaluated against Gram‐negative E. coli and Gram‐positive B. subtilis bacteria via direct‐contact assay according to our previous work.[ 8b ]

Direct‐Contact Colony Formation Assay

PTLAs were directly prepared inside the 96‐well plate and sterilized. Fresh med‐log phase bacteria E. coli and B. subtilis (106 CFU mL−1, 10 µL) were seeded on the hydrogels’ surface, and 10 µL of both bacteria suspensions were seeded inside empty wells as controls. Then, the plate was incubated at 37 °C (approximately 1 h) for medium evaporation to ensure that bacteria efficiently adhered to the hydrogels’ surface. Further, fresh LB broth (250 µL) was added and gently mixed for 1 m and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h (220 RPM). Lastly, 200 µL of the suspension over the hydrogel was transferred into 96‐well plates to establish the growth curves (37 °C, 20 hours, OD 600 nm, Biotek Synergy H1F1 Plate reader). An additional 10 µL was seeded on the LB agar plates and incubated for 12 hours. In addition, time‐dependent antimicrobial studies of PT5L3A hydrogel followed the same procedure, but with incubation times of 15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 2 h, and 4 h, respectively.

Live/Dead Assay

Following the colony formation assay, after 4 h of incubation, the suspension over the hydrogel was collected and centrifuged (5000 RPM, 5 min); the pelleted cells were stained with Syto‐9 (3 µm) and PI (15 µM) for 30 min. After staining, the samples were imaged using the EVOS microscope (EVOS 5000, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Following the colony formation assay, the suspended cells over the hydrogel were transferred and pelleted, then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h at 4 °C. Fixed cells were washed with 2 × PBS and dehydrated using gradient concentrations (30%, 50%, 80%, 100%) of ethanol. Further, the dehydrated cells inside the 100% ethanol were suspended on a silicon wafer, dried, and coated with gold (6 nm). Cells grown on standard plate surfaces were defined as controls. Finally, the morphology of bacterial cells was captured using an HR‐SEM (Zeiss Ultra Plus).

Atomic Force Microscopy

The surface details and cell integrity of control and PT5L3A hydrogel‐treated E. coli and B. subtilis were assessed via a non‐contact model using high‐resolution atomic force microscopy (HR‐AFM, Asylum). The sample preparation was the same as the SEM study. The surface topography was visualized utilizing an MFP‐3D Infinity AFM system with non‐contact cantilevers (240AC‐NA, 2 N m−1, 70 kHz, OPUS). For imaging, multiple 25 × 25 µm2 scans with a scan rate of 1 Hz were performed. The bacterial surface profiles were produced using the instrument software (WSxM 5.0 Develop 10.3), and surface roughness and bacterial height were calculated from the central 40% of each profile, where the average Z position value represents the bacterial height, and the standard deviation represents the surface roughness.

Antibiofilm Study

E. coli and B. subtilis suspensions (106 CFU mL−1) were seeded in 24‐well plates containing sterilized PT5L3A hydrogel, respectively, and the silicon wafer and empty well were also seeded as controls. The plate was incubated at 37 °C under static conditions for biofilm formation. After 48 h, the hydrogel and control silicon wafer were removed and washed twice with PBS to remove any nonadherent bacterial cells from the surface. Further, the washed hydrogel and wafer were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 hour, then washed with PBS, followed by dehydration using an ethanol gradient (30%, 50%, 80%, 100%), and prepared for SEM imaging (6 nm gold coating). Meanwhile, the biofilms in control empty and hydrogel‐containing wells were assessed via crystal violet (CV) assay according to our previous work.[ 8b ] The supernatant was removed, and the well was washed twice with PBS to remove any nonadherent bacterial cells. The remaining biofilm at the bottom and side walls was stained with 500 uL of CV solution (0.1% (w/v)) for 5 min, followed by 2 × PBS washing, and then imaged by an EVOS microscope (EVOS 5000 Thermo Fisher Scientific). The CV that adhered to the biofilm matrix was solubilized by adding 500 uL of glacial acetic acid solution (7% (v/v)); after 15 min, the absorbance was read at 590 nm (Biotek Synergy H1F1 Plate reader).

Tissue Adhesion Study

To assess the tissue adhesion performance, PTLAs were freshly prepared and applied to different fresh animal organs (skin, bone, liver, heart, and kidney) in the air and underwater, respectively, and the adhesion was visualized. For quantitative evaluation, the adhesion strength was measured against the porcine skin via both standard lap‐shear test (ASTM F2255) and 180‐degree peel test (ASTM F2256) using a Universal Materials Testing Machine (50 N load cell, EZ‐LX, SHIMADZU). First, fresh porcine skin was cleaned (0.01% w/v sodium azide) and cut into a rectangular bar (35 × 12 mm2) as substrate, and then freshly prepared PTLAs (12 × 12 mm2) were applied between two substrates and cured (500 g weight) for 5 min before the test. For different lap‐shear and 180‐degree peel tests, two porcine skin substrates were placed in different directions. Next, the test specimens were placed in the grips of the testing machine, and it was ensured that the long axis of the specimens coincided with the applied load. The load was applied until the failure of adhesion with a strain rate of 40 mm min−1. Shear strength was calculated by dividing the maximum force of the lap‐shear test by the sample (adhesion) area; interfacial toughness was determined by dividing the two times plateau force of the 180‐degree peel test by the width of the sample (±SD, n = 3).

Burst Pressure Study