Abstract

Haemophilus influenzae (Hi), an obligate upper respiratory tract commensal/pathogen, uses phase variation (PV) to adapt to host environment changes. Switching occurs by slippage of nucleotide repeats (microsatellites) within genes coding for virulence molecules. Most such microsatellites in Hi are tetranucleotide repeats, but an exception is the dinucleotide repeats in the pilin locus. To investigate the effects on PV rates of mutations in genes for mismatch repair (MMR), insertion/deletion mutations of mutS, mutL, mutH, dam, polI, uvrD, mfd and recA were constructed in Hi strain Rd. Only inactivation of polI destabilized tetranucleotide (5′AGTC) repeat tracts of chromosomally located reporter constructs, whereas inactivation of mutS, but not polI, destabilized dinucleotide (5′AT) repeats. Deletions of repeats were predominant in polI mutants, which we propose are due to end-joining occurring without DNA polymerization during polI-deficient Okazaki fragment processing. The high prevalence of tetranucleotides mediating PV is an exceptional feature of the Hi genome. The refractoriness to MMR of hypermutation in Hi tetranucleotides facilitates adaptive switching without the deleterious increase in global mutation rates that accompanies a mutator genotype.

Keywords: Haemophilus/microsatellite/mismatch repair/phase variation/Pol I

Introduction

High frequency gain and loss of the expression of virulence determinants is an intrinsic feature of many bacterial pathogens. This reversible switching of surface antigens, referred to as phase variation (PV), was originally coined to describe the switching of Salmonella flagella antigens (Andrewes, 1922). This process is stochastic and driven by highly mutable loci that generate repertoires of phenotypic variants from which the fittest variant is selected. These hypermutable loci have been called contingency loci to explain their role in facilitating bacterial adaptation to the dynamic and unpredictable changes in the host environment (Moxon et al., 1994). There are many mechanisms of hypermutation in contingency loci, but one of the commonest is mediated by changes in the number of repeats within simple sequence repeat tracts (microsatellites) located in either the promoter or open reading frame (ORF) of a gene (Moxon et al., 1994; Bayliss et al., 2001). These loci, referred to as simple sequence contingency loci, are found in comparatively high numbers in the genomes of many pathogenic bacteria, including Haemophilus influenzae (Hi), Neisseria meningitidis (Nm), Helicobacter pylori (Hp) and Campylobacter jejuni (Cj) (Hood et al., 1996; Saunders et al., 1998, 2000; Parkhill et al., 2000). A critical role in pathogenesis has been proposed for some of these loci (see Saunders et al., 1998; Bayliss et al., 2001; Linton et al., 2001). The rate of PV of contingency loci is predicted to be a major factor controlling the genetic diversity of bacterial populations (De Bolle et al., 2000) and this diversity may have a major influence on fitness and virulence (Bayliss et al., 2001). Thus, an understanding of the processes that control the mutation rates of simple sequences in these organisms is central to unravelling the contribution of phase-variable genes to the biology of these bacteria.

Hi is a ubiquitous commensal of the human upper respiratory tract, but also includes strains with the potential to cause invasive diseases such as meningitis. Hi can phase vary a number of its surface determinants including many of the carbohydrate epitopes of its lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS is a major pathogenic determinant of this bacterium and the PV of parts of this molecule is likely to have an impact on the ability of Hi to cause disease (Hood and Moxon, 1999). The genome of strain Rd contains 12 tetranucleotide repeat tracts of >6 repeat units, all of which are within ORFs and most of which modulate expression of surface components (Hood et al., 1996). Additionally, some Hi strains have loci containing penta- and heptanucleotide repeat tracts (van Belkum et al., 1997; Dawid et al., 1999). Surprisingly, only one locus, hif, has a dinucleotide repeat tract (van Ham et al., 1993) and none have mononucleotide repeat tracts. In contrast, many of the simple sequence contingency loci of other phase-variable bacteria, notably Neisseria sp. and Hp (Saunders et al., 1998, 2000), contain mononucleotide repeat tracts.

PV rates are known for a number of the simple sequence contingency loci of Hi, and rates appear to correlate with the length of the repeat tract (De Bolle et al., 2000). Few studies, however, have looked at the effect of trans-acting factors on PV rates in Hi and the only finding to date is that recA mutations do not have an effect (Dawid et al., 1999). Studies of simple sequence contingency loci in other PV bacteria have indicated roles for Rho transcription termination factor (Lavitola et al., 1999) and mismatch repair genes, mutS and mutL (Richardson and Stojiljkovic, 2001), in controlling PV rates of Nm. Mutation rates of simple sequences, termed microsatellites, have been examined in detail in yeast, using both artificial and native sequences, and in Escherichia coli (Ec), using reporter constructs containing artificial microsatellites. These studies have implicated roles for mismatch repair (MMR), proof-reading by the replicative DNA polymerase, processing of Okazaki fragments, and other pathways, in modulating the mutation rates of microsatellites with unit lengths of 1–3 nucleotides (Sia et al., 1997; Strauss et al., 1997; Tran et al., 1997; Kokoska et al., 1998; Morel et al., 1998). In the few studies of tetranucleotide repeat tracts, mutation rates of these tracts are increased by MMR mutations in yeast (Sia et al., 1997), but not in Ec (Eckert and Yan, 2000). We have investigated the effect of trans-acting factors on mutation rates of tetranucleotide repeat tracts in Hi, an organism in which such tracts are the major mechanism of PV. We show that mutations in polI, but not seven other genes whose products are involved in DNA metabolism, destabilize tetranucleotide repeat tracts of PV reporter constructs and increase deletions of repeats in these tracts.

Results

Construction and analysis of Hi DNA metabolism mutants

Potential trans-acting factors for PV in Hi were identified by considering effects of trans-acting mutations on the mutation rates of microsatellites in other systems. Based on this analysis, we constructed mutations in the Hi homologs (Table I) of the following Ec genes: MMR genes (mutS, mutL, mutH and dam), a nucleotide excision repair gene (uvrD), a transcription-coupled repair factor (mfd), a recombinase (recA), Pol I (polI or polA), a replication/repair-associated DNA helicase (rep), the proof-reading subunit of Pol III (dnaQ) and the SOS repressor (lexA). Insertion mutations were made in recA and uvrD by inserting an antibiotic cassette into a restriction site in the central part of the cloned gene (Table I). Insertion/deletion mutations were made in the other genes by cloning 5′ and 3′ fragments of the genes that were not co-linear and inserting an antibiotic cassette between them (Table I). Hi strain Rd was transfected with these clones and transformants were isolated in which the wild-type (wt) chromosomal gene was replaced with the mutated gene for eight of the genes, but not for rep, dnaQ and lexA, possibly because mutations in these genes are lethal in Hi.

Table I. Oligonucleotide primers used to construct mutations in DNA metabolism genes of Hi.

| HI gene numbera | E.coli homologue (% similarity)a | Insertion site of antibiotic cassetteb (size of deletion) | Sequencesc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0707 | mutS (84%) | 1288–1345 (57 bp) | 5′CCGAATTCCAACAACATACGCCAATG [19–39] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTCAGCAATCACGCCACC [1288–1270] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTGGAAAACCTAGAAAAACG [1345–1364] | |||

| 5′CGCCAAGGCTTGTTTAGGGC [2553–2534] | |||

| 0067 | mutL (67%) | 904–929 (25 bp) | 5′CCGGATCCTATTAAAATTCTTTCCCC [4–23] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTGACATCTACATCGTGCGG [904–883] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTTCATCAACAACGCCTC [929–948] | |||

| 5′CGGAATTCGTCTAATAAAGGCTGCC [1884–1865] | |||

| 0403 | mutH (81%) | 355–475 (120 bp) | 5′CGGAATTCTCAAGCACATGCAAATC [(–)664–(–)645] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTCAATGGGCATCCAAAG [355–337] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTGGCSAAATTAGATCAAATTAC [475–497] | |||

| 5′CCGGATCCAATTTTACGCCCTTTGTTAG [1495–1474] | |||

| 0209 | dam (71%) | 530–551 (21 bp) | 5′CCGGATCCCTCGTGTTAAACGCAATTC [(–)45–(–)25] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTTCACAGCATAAAAACACCGC [530–511] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTGCCGATAAGGATTCGGTG [551–570] | |||

| 5′TTTTATGGGGCAGAATTCGC [1419–1400] | |||

| 0856 | polI (77%) | 1049–1715 (666 bp) | 5′CGGAATTCACAAGTACAGCCCACTC [151–169] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTTTCAATCCAGCGGG [1049–1031] | |||

| 5′CAATCTAACGAAATTGCCTC [1672–1691] | |||

| 5′CCGGATCCCAATTTTGTCCAACACC [2781–2761] | |||

| 1188 | uvrD (83%) | 1106d | 5′CCGAATTCCGCCTAAACAGGCTTG [425–443] |

| 5′CCGGATCCACATTAATCACTGTGCC [2087–2068] | |||

| 0600 | recA (86%) | 521d | 5′CGGGATCCCCATCCTCTTTACTGAA [(–)123–(–)104] |

| 5′TTATTGCGGAGCTCGAATTC [1220–1201] | |||

| 1258 | mfd (83%) | 1915–1987 (72 bp) | 5′GCCGGAGCAAACGCTGTTTG [831–850] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTCAGTTTTACCAAAACCC [1915–1896] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTAGCCCAACAGCATTATG [1987–2005] | |||

| 5′CGGAATTCTGCTTTACTCTCTGC [3122–3103] | |||

| 0137 | dnaQ (77%) | 250–951 (701 bp) | 5′CGGGATCCAATCGCCAAAACGGACG [(–)719–(–)698] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTGGGCAACTTCTTTGAATTC [250–229] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTATCTCGGAGTGGTAGTTC [951–971] | |||

| 5′CGCATCATCAATTAATGCCG [2070–2051] | |||

| 0649 | rep (83%) | 818–834 (16 bp) | 5′CGGGATCCTCAACAACAACAAGCC [11–30] |

| 5′CGAAGCTTAATCACGTTCAAACG [818–799] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTCAACCCAGCGTATTTTGC [834–853] | |||

| 5′TGCCCTCCTCCATACCAATC [1732–1713] | |||

| 0749 | lexA (85%) | 37–276 (239 bp) | 5′CCGAATTCTGAGCCATGTTCAACTACC [(–)802–(–)782] |

| 5′CTAAGCTTCACTTCTTGTTGGCGTGCGG [33–14] | |||

| 5′CGAAGCTTGCAGAGCAGCATATTGAAGC [277–299] | |||

| 5′CGGGATCCGAAACTGCACCACATAGTAC [1227–1208] | |||

| 0855 | b3109 (75%) | 160–187 (27 bp) | 5′CGGAATTCCAATCTAACGAAATTGCCTC [(–)1136–(–)1117] |

| 5′CGGATATCTTGCTTCAATGCGTTCAGGTG [160–140] | |||

| 5′CGGATATCGGATTGGGCGTTGCTGTGCC [187–206] | |||

| 5′CCGGATCCAGCCCATTTGGCTATGACGC [1472–1452] |

aGene numbers, homologous Ec K12 genes and percentage similarities are taken from the TIGR Microbial database (www.tigr.org) and their analysis of the Hi Rd genome sequence.

bNumbers indicate nucleotide positions relative to the initiation codon.

cPrimers are ordered 1–4 from top to bottom for each gene. Most of the 1 and 4 primers contain either EcoRI or BamHI restriction sites at the 5′ end, and most of the 2 and 3 primers contain HindIII restriction sites at the 5′ end. In the cases where these sites are lacking in the primers, or only two primers were used, restriction sites in the native sequences were utilized. Numbers in parentheses indicate the position of the primers relative to the initiation codon for the gene, with negative numbers indicating a position that is 5′ to this codon.

dIn these cases, the tetracycline cassette was inserted at this position and no deletion was made.

Growth curves were performed with these eight mutants and, apart from polI mutants, doubling times were similar to strain Rd (data not shown). RdΔpolI mutants exhibited, relative to strain Rd, up to 3-fold higher doubling times, 2- to 3-fold lower plating efficiencies (i.e. c.f.u./OD490 unit), but similar amounts of protein per OD490 unit (data not shown). These results indicated that RdΔpolI mutants were forming filaments with an average size of 2–3 cells/filament and examination under phase contrast light microscopy revealed the presence of filaments ranging up to 20 µm in length (single cells being ∼1 µm in length). A similar phenotype has been observed when Ec polI null mutants are grown on rich media (Joyce and Grindley, 1984). RdΔpolI mutants also exhibited heterogeneity in colony size and elongated growth times for colonies on plates.

Global mutation rates were measured for the Hi mutants by measuring the frequency of generation of nalidixic acid-resistant variants (Table II). The mutS, mutL and mutH mutants exhibited 3- to 4-fold higher mutation rates than strain Rd. These rates were significantly different as shown by the non-overlapping confidence intervals (Table II). Higher rates for mutSLH mutants were expected because their products are involved in MMR, but the absence of an increase in rates for dam mutants was unexpected and suggests that MMR in Hi may not follow the canonical Ec model. The 2.5-fold higher rate for the polI mutant was not significant but may indicate that Pol I has a critical role in error correction during DNA replication.

Table II. Spontaneous mutation rates of Hi mutant strains.

| Strain | NalR mutation rate (× 10–9)a |

|---|---|

| Rd | 1.79 (1.0) {2.57–0.99} |

| RdΔmutS | 6.9 (3.9) {13.15–2.62} |

| RdΔmutL | 6.09 (3.4) {14.8–3.74} |

| RdΔmutH | 6.86 (3.8) {12.55–3.62} |

| RdΔpolI | 4.54 (2.5) {25.51–1.59} |

| RdΔrecA | 2.9 (1.6) {4.28–2.38} |

| RdΔmfd | 0.88 (0.5) {1.82–0.62} |

| RdΔuvrD | 0.98 (0.5) {2.98–0.58} |

| RdΔdam | 1.13 (0.6) {3.54–0.93} |

aFrequencies of nalidixic acid resistance were determined for at least 10 colonies of Rd and each of the mutant strains. Mutation rates were derived using the median frequency according to Drake (1991) and are expressed as the number of nalidixic acid-resistant bacteria produced per cell per division. Numbers in parentheses are the fold increase over wild type. Numbers in curly brackets are 95% confidence intervals calculated as described by Kokoska et al. (1998).

Tetranucleotide repeat-mediated PV rates of Hi DNA metabolism mutants

Most of the simple sequence contingency loci in Hi contain tetranucleotide repeat tracts. The influence of trans-acting factors on this major mechanism of PV in Hi was investigated by transferring the mutations described above into strains carrying mod–lacZ fusions with tetranucleotide repeat tracts of 38 or 17 5′AGTC repeat units (R), RdGΔZ38R and RdGΔZ17R, respectively (De Bolle et al., 2000), and measuring the switching rates of these constructs (Table III). Switching from ON-to-OFF occurred at rates similar to those of the parental constructs for all the mutants, including those in MMR genes, except polI mutants which exhibited 30- and 49-fold higher rates than the parental constructs (Table III). The fact that these rates were significantly different from those of parental constructs was shown by non-overlapping confidence intervals (Table III) and a statistical analysis, which yielded P <0.0001 (using a Mann–Whitney non-parametric rank sum test) for comparisons between frequencies of variants of polI mutants and equivalent parental strains. The possibility that this increase was due to the polI mutation interfering with expression of downstream genes was investigated by constructing a mutation in hi0855 (Table I). This gene encodes a conserved hypothetical protein, and its initiation codon is 15 bp 3′ to the termination codon of polI. PV rates for the RdΔhi0855GΔZ38R mutants were similar to those of parental constructs (Table III), indicating that the increased rates observed with polI mutants were not attributable to polar effects on hi0855. Pleiotrophic effects are common in DNA replication mutants and Ec polI mutants are known to induce the SOS response (Morel et al., 1998). As RecA protein is essential for induction of the SOS response (for a review see Little, 1993), we investigated a possible role of the SOS response by attempting to inactivate recA in RdΔpolI strains. Strains were transformed with pUCΔrecAchl and two mutants were obtained, RdΔpolIΔrecAchlGΔZ17R and RdΔpolIΔrecAchlGΔZ29R. These mutants exhibited ON-to-OFF PV rates similar to the parental polI mutants (Table III) suggesting that SOS induction in these mutants is not responsible for the elevated tetranucleotide- mediated PV rates.

Table III. Influence of mutations in DNA metabolism genes on the rates of PV of tetranucleotide repeat tracts in Hi.

| Relevant genotypea | Direction of switching |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ON-to-OFF |

OFF-to-ON |

|||||||

| No. of 5′AGTC repeats | Mutation rate (× 10–4)b | No. of 5′AGTC repeats | Mutation rate (× 10–4) | No. of 5′AGTC repeats | Mutation rate (× 10–4) | No. of 5′AGTC repeats | Mutation rate (× 10–4) | |

| Wt | 38 | 2.03c {3.41–1.44} [1.00] | 17 | 0.54c {0.70–0.29}[1.00] | 37 | 1.24c {1.36–0.75} [1.00] | 18 | 0.36c {0.48–0.18} [1.00] |

| ΔmutS | 38 | 2.45 {3.49–1.88} [1.21] | 17 | 0.64 {0.83–0.46} [1.19] | 37 | 0.84 {1.31–0.70} [0.68] | ||

| ΔmutL | 38 | 2.28 {2.85–2.69} [1.12] | 17 | 0.41 {0.64–0.24} [0.76] | 37 | 0.93 {1.19–0.73} [0.74] | ||

| ΔmutH | 38 | 1.88 {3.60–1.67} [0.93] | 17 | 0.61 {0.79–0.42} [1.12] | 37 | 1.83 {2.97–1.24} [1.48] | ||

| ΔpolI | 35 | 62.16 {72.6–45.6} [30.6] | 17 | 26.53 {43.5–13.3} [49.1] | 37 | 11.66 {17.5–7.23} [9.40] | 21 | 16.01 {25.1–11.1} [44.5] |

| 31 | 14.05 {19.4–12.4} [11.33] | 16 | 4.87 {18.3–2.16} [13.5] | |||||

| ΔrecA | 41 | 2.52 {3.94–1.73} [1.24] | 17 | 1.09 {1.65–0.86} [2.01] | 37 | 1.47 {2.12–1.09} [1.18] | ||

| 35 | 3.17 {26.8–1.70} [1.56] | |||||||

| Δmfd | 38 | 2.49 {2.88–2.23} [1.23] | 17 | 0.52 {0.83–0.37} [0.97] | 37 | 0.91 {8.01–0.78} [0.74] | ||

| Δdam | 38 | 3.13 {3.51–2.59} [1.54] | 17 | 0.87 {1.09–0.37} [1.60] | 39 | 4.33 {5.22–1.85} [3.50] | ||

| 36 | 3.89 {6.81–2.15} [3.14] | |||||||

| ΔuvrD | 38 | 3.59 {3.99–2.71} [1.77] | 17 | 0.60 {0.84–0.37} [1.11] | 37 | 1.61 {2.65–1.27} [1.30] | ||

| Δhi0855 | 38 | 2.20 {18.3–1.50} [1.08] | 17 | 0.52 {1.46–0.33} [0.96] | 37 | 0.70 {0.88–0.58} [0.56] | ||

| 35 | 1.33 {21.2–0.70} [0.87] | |||||||

| ΔpolI ΔrecA | 29 | 55.0 {145.9–45.1} [27.1] | 17 | 34.6 {40.3–27.7} [64.1] | ||||

aPhase variation reporter strains carrying mutations in other genes were constructed by transforming RdGΔZ38R or RdGΔZ17R (i.e. Hi strains carrying in-frame mod–lacZ fusions containing 38 or 17 5′AGTC repeats) with plasmid constructs, pUCΔmutS, pUCΔmutL, pUCΔmutH, pUCΔpolI, pUCΔrecA, pUCΔmfd, pUCΔdam, pUCΔuvrD or pUCΔhi0855, which all contain a tetracycline resistance cassette. PolI/recA double mutants were constructed by transforming RdGΔZ35RΔpolI or RdGΔZ17RΔpolI with pUCΔrecAchl, which contains a chloramphenicol resistance cassette. Out-of-frame or OFF variants were derived from these strains.

bMutation rates were derived from the median frequency of variants by the method of Drake (1991). Median frequencies were determined from the analysis of at least 16 colonies for most of the strains apart from the following, in which eight were analysed: 35R and 41R ΔrecA; 37R, 31R, 21R and 16R ΔpolI; 37R Δmfd; 39R and 36R Δdam; 38R, 35R and 17R Δhi0855; and 38R ΔpolIΔrecA. Numbers in curly brackets are 95% confidence intervals calculated according to Kokoska et al. (1998). Fold increase in mutation rates relative to the parental rates are given in square brackets.

cValues as reported previously by De Bolle et al. (2000).

Rates of switching from OFF-to-ON were also measured for variants of all the mutants (Table III) and elevated rates were only observed for OFF variants of RdΔpolIGΔZ38R, being 9- and 11-fold higher than parental rates for constructs with 37 and 31 repeats, respectively (Table III). These data indicated that the polI mutation also increased OFF-to-ON switching rates, and further evidence for this result was obtained by measuring switching from OFF-to-ON for variants derived from constructs containing 17 repeats. Rates were 13- and 44-fold higher for constructs with 16 and 21 repeats, respectively, than those derived for RdGΔZ18R (Table III). These rates for OFF-to-ON switching of polI mutants were significantly different from those of equivalent parental constructs (P <0.0005 for constructs with 37 or 31 repeats and P <0.002 for constructs with 21 or 16 repeats, calculated as above).

Ratios of ON-to-OFF to OFF-to-ON PV rates for Rd mod/lacZ reporter strains with repeat tracts of equivalent lengths (38R:37R, 32R:31R, 23R:24R and 17R:18R; mutation rates were assumed to be independent of repeat number) occur within a narrow range, 1.6:1–1.5:1 (De Bolle et al., 2000). For RdΔpolI reporter strains, higher ratios were observed with OFF-to-ON switching rates derived from OFF variants, in which the insertion of a single repeat unit produced a mod/lacZ ORF (i.e. 5.3:1 for 35R:37R, 4.4:1 for 35R:31R and 5.4:1 for 17R:16R; derived from the data in Table III) whereas parental ratios were obtained if deletion of a single repeat unit produced a mod/lacZ ORF (i.e. 1.7:1 for 17R:21R). The three-fold difference between these ratios indicated that the ∼40-fold increase in ON-to-OFF switching rates of RdΔpolI reporter strains (Table III) was due to 10- and 30-fold increases, respectively, in the rates of insertions and deletions. This phenomenon was investigated further by analysing alterations in repeat tracts.

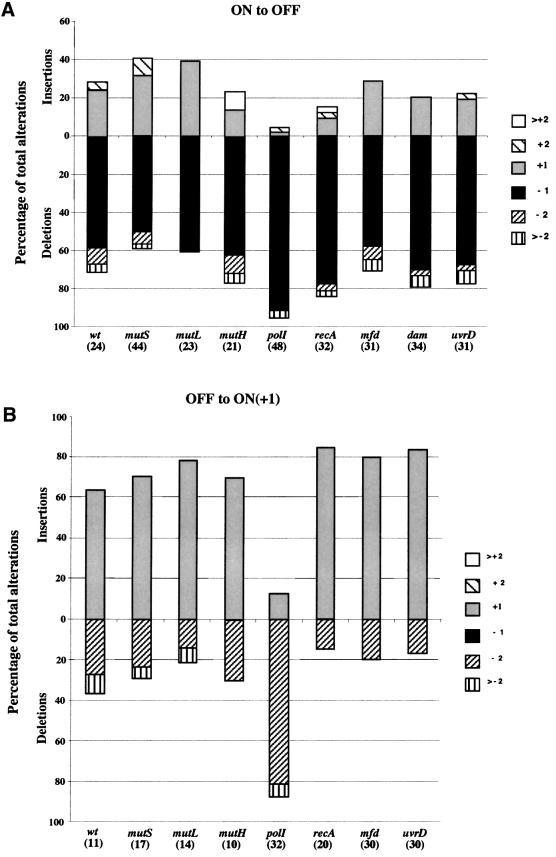

Switching in Rd mod/lacZ reporter strains correlates with changes in the number of tetranucleotide repeat units; 90% of ON-to-OFF phase variants exhibiting single repeat unit changes and the ratio of deletions to insertions being 2:1 (De Bolle et al., 2000). Alterations in the repeat tracts of variants derived from mutant strains were investigated and all variant colonies had alterations in the length of the repeat tract with the proportion of one repeat unit alterations in ON-to-OFF variants being similar to the parental strains (Figure 1). However, compared with equivalent Rd strains, RdΔpolI mod/lacZ reporter strains exhibited a significantly greater number of deletions (Figure 1). The ratio of deletions to insertions for ON-to-OFF switching (Figure 1A) was 23:1 for RdΔpolI GΔZ35R, which was significantly higher than the 1.6:1 ratio for RdGΔZ38R (by Fisher’s exact test P = 0.005, Odds ratio 9.47, 95% confidence intervals 1.79–50.18). The ratio for RdΔpolIGΔZ17R was 10:1 (data not shown), which was not significantly different from the 4:1 ratio of RdGΔZ17R (De Bolle et al., 2000) but indicated that 2.5-fold more deletions had occurred in this strain. This value was closer to the 3-fold increase in deletions over insertions predicted for the polI mutants from the PV rates (see above). This result may indicate either that the higher increase (14-fold) in deletions observed with constructs with 38 repeats was an overestimation or that the increase in the number of deletions may decrease as the length of the repeat tract was reduced. Values for the other mutants ranged from 1:1 to 6:1 (Figure 1A) and 2:1 to 7:1 (data not shown) for constructs with 38 and 17 repeats, respectively, and were not significantly different from those of equivalent Rd strains.

Fig. 1. Influence of trans-acting factors on the types of alterations occurring in tetranucleotide repeat tracts in Hi. Alterations in the 5′AGTC repeat tracts of phase-variant colonies were classified as either insertions or deletions of the repeat units (i.e. an increase or decrease, respectively, in the number of repeat units) and as changes of one, two or more repeat units. The numbers of variants in each class were expressed as a percentage of the total number examined. Relevant genotypes and total number of variants examined for (in parentheses) each strain are indicated below each column. (A) ON-to-OFF switching. Parental colonies contained 38 (wt and most of the mutants) or 35 (ΔpolI) 5′AGTC repeats. Data for the ΔrecA mutants is the combined data for parental colonies containing either 41 or 35 5′AGTC repeats. (B) OFF-to-ON switching in which the +1 reading frame produces a Mod–LacZ fusion protein. Parental colonies contained, in most cases, 37 5′AGTC repeats. Data for the wt and ΔpolI strains is the combined data for parental colonies containing either 37 or 31 repeats [in the former case, the data were reported previously (De Bolle et al., 2000)].

Ratios of deletions to insertions were also determined for OFF variants that required a +1 or a –2 repeat unit shift to produce a Mod–LacZ fusion protein (Figure 1B). The ratio was 6:1 for polI mutants (combined data for RdΔpolGΔZ34R and RdΔpolGΔZ31R), which was significantly different from the parental ratio of 1:2 (combined data for strains RdGΔZ37R and RdGΔZ31R, De Bolle et al., 2000; P = 0.0022, Odds ratio 12.25, 95% confidence intervals 2.5–61.6). Ratios for the other mutants ranged from 1:2 to 1:6 (all 37R; see Figure 1B) and were not significantly different from the parental ratio. The ratio for RdΔpolGΔZ16R, for which there was no comparable parental data, was 3:1 (data not shown). Finally, a ratio was determined for OFF variants of polI mutants containing 21 repeats that required a +2 or –1 shift. This ratio of 16:1 (data not shown) was not significantly higher than the parental ratio of 7:1 (combined data for strains RdGΔZ24R and RdGΔZ18R from De Bolle et al., 2000) but indicated that there was a 2-fold increase in deletions.

Inactivation of mutS increases Hi dinucleotide repeat-mediated PV rates

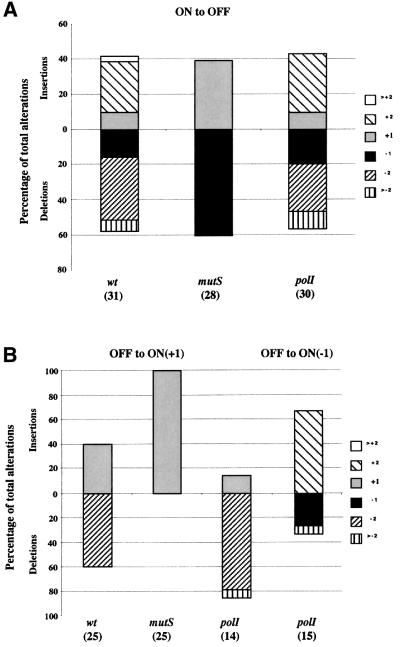

Since PV of the Hi pilus is driven by a dinucleotide repeat tract consisting of nine 5′TA repeats (van Ham et al., 1993) and MMR mutations are known to increase the mutation rates of such tracts in other organisms, it was of interest to see whether PV rates mediated by dinucleotide repeat tracts were affected by MMR mutations in Hi. A mod–lacZ fusion carrying 20 5′AT dinucleotide repeat units was constructed and transferred into strains Rd, RdΔmutS and RdΔpolI. PV rates in RdGΔZ–AT20R strains (Table IV) were within the range of rates observed for the RdGΔZ strains with 23 and 17 5′AGTC repeats (Table III; De Bolle et al., 2000), suggesting that dinucleotide and tetranucleotide repeat tracts, containing similar numbers of repeat units, phase vary at similar rates in Hi. Rates for RdΔmutS dinucleotide mod/lacZ reporter strains were significantly higher than those of control strains for both directions of switching (Table IV; P <0.0001, calculated as for the tetranucleotide repeat tracts). Rates for the RdΔpolI mutants were not significantly different from the controls (Table IV). Thus, dinucleotide repeat tracts were destabilized by loss of MMR but not polI. The types of mutational events producing variants were analysed as described above. Interestingly, for the ON-to-OFF direction of switching, the Rd and RdΔpolI dinucleotide mod/lacZ reporter strains exhibited ∼2-fold more two, rather than one, repeat unit changes, whilst in equivalent ΔmutS strains, all the changes were by a single repeat unit (Figure 2). One possible explanation is that dinucleotide repeat tracts form 4 bp single-stranded (ss) DNA loops (i.e. two unpaired repeat units) that cannot be corrected by MMR. These results also indicate that a large number of mutational events occur in dinucleotide repeat tracts, which are corrected by MMR. Dinucleotide repeat tracts may, therefore, be more prone to mutation than tetranucleotide repeat tracts.

Table IV. Influence of mutations in DNA metabolism genes on the rates of PV of dinucleotide repeat tracts in Hi.

| Relevant genotypea | Direction of switching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ON-to-OFF |

OFF-to-ON |

|||||

| No. of 5′AT repeats | Mutation rate (× 10–4)b | Fold increase over wt | No. of 5′AT repeats | Mutation rate (× 10–4) | Fold increase over wt | |

| wt | 20 | 0.89 {1.06–0.51} | 1.0 | 22 | 0.66 {0.84–0.50} | 1.0 |

| ΔmutS | 20 | 23.97 {24.3–21.7} | 26.8 | 19 | 11.20 {13.8–9.23} | 17.0 |

| ΔpolI | 20 | 1.74 {2.74–0.99} | 1.9 | 18 | 1.15 {3.46–0.68} | 1.7 |

| 19 | 1.10 {1.82–0.37} | 1.6 | ||||

aDinucleotide PV reporter constructs were constructed by transforming Rd (wt), RdΔmutS and RdΔpolI with pGΔZ20AT (i.e. a plasmid carrying an in-frame mod–lacZ fusion containing 20 5′AT repeats). Out-of-frame or OFF variants were derived from these strains.

bMutation rates were derived from the median frequency of variants by the method of Drake (1991). Numbers in curly brackets are 95% confidence intervals calculated according to Kokoska et al. (1998). Median frequencies were determined from the analysis of 16 colonies for all the strains apart from RdGΔZ18ATΔpolI and RdGΔZ19ATΔpolI, in which case only eight colonies were analysed.

Fig. 2. Types of alterations occurring in dinucleotide repeat tracts in Hi strains carrying mutations in mutS or polI. Alterations were analysed and are presented as described for Figure 1. Relevant genotypes of and total number of variants examined for (in parentheses) each strain are indicated below each column. (A) ON-to-OFF switching. The parental colonies contained 20 5′AT repeats. (B) OFF-to-ON switching in which either the +1 (columns 1–3) or –1 (column 4) reading frame produces a Mod–LacZ fusion protein. Parental colonies contained 22 5′AT (wt), 19 5′AT (ΔmutS or ΔpolI, column 3) or 18 5′AT (ΔpolI, column 4) repeats.

Inactivation of polI elevates PV rates of a naturally phase-variable Hi LPS epitope

In order to investigate whether inactivation of polI increases the mutation rates of other tetranucleotide repeat tracts in the Hi genome, we measured the PV rates of a LPS epitope whose synthesis is controlled by loci containing tetranucleotide repeats. This epitope, a digalactoside modification of LPS, is present in strain Eagan but not strain Rd and is recognized by monoclonal antibody (Mab) 4C4. Addition of this digalactoside is dependent on three phase-variable genes, lgtC, lic2A and lex2A (Hood and Moxon, 1999; R.Aubrey, A.D.Cox, D.W.Hood, M.A.Herbert, C.D.Bayliss, K.Makepeace, J.C.Richards and E.R.Moxon, in preparation), which contain 23 5′GACA, 17 5′CAAT and 18 5′GCAA repeats, respectively. Mutations in polI were constructed in strain Eagan by transforming this strain with either chromosomal DNA derived from strain RdΔpolI or pUCΔpolIkan. EaganΔpolI mutants grew slowly on plates and exhibited reductions in plating efficiency as observed for RdΔpolI mutants. PV rates were measured by transferring colonies to nitrocellulose and probing these filters with Mab4C4. PV rates for Mab4C4 were compared for EaganΔpolI mutants and strain Eagan. For strain Eagan, the ON-to-OFF switching rate was 1.2 × 10–4 mutations/division and that for OFF-to-ON was 2-fold lower. For the EaganΔpolIkan mutant, the comparable rates were 10-fold (P = 0.0006 using the Mann–Whitney non-parametric rank sum test) and 30-fold higher than those of strain Eagan (this latter value was, however, derived from the analysis of only two colonies). For the EaganΔpolItet mutant, the OFF-to-ON switching rate was 8-fold higher than that of strain Eagan (P = 0.0003, as above). PV rates of a dinucleotide repeat tract were also investigated in strain Eagan by measuring pilus PV, the expression of which is controlled by nine 5′TA repeats. Rates of pilus switching were determined using a polyclonal serum specific for the Eagan pilus (Gilsdorf et al., 1990). The rate of switching from OFF-to-ON was 7.1 × 10–6 mutations/division for strain Eagan, whereas the rates for the EaganΔpolIkan and EaganΔpolItet mutants were 2.6- and 2.1-fold higher, respectively. These mutants contained the same number of dinucleotide repeats as strain Eagan (data not shown). This result suggests that this polI mutation produces similar effects on dinucleotide-mediated PV rates in Hi strains Eagan and Rd, whilst the heightened Mab4C4 PV rates indicates that other, possibly all, Hi tetranucleotide repeat tracts are destabilized by mutation of polI.

Discussion

PV mediated by simple sequences or microsatellites is a common feature of many bacteria, but, in Hi, a conspicuous feature is the predominance of tetranucleotide repeat tracts. In this report, we show that mutation of Hi polI, but not of seven other Hi genes, whose products are involved in MMR or other pathways of DNA repair or recombination, increases PV rates mediated by a tetranucleotide repeat tract. Conversely, loss of MMR activity, but not of polI activity, increased PV rates mediated by a dinucleotide repeat tract. This is the first report of a trans-acting factor that alters PV rates in Hi, and also demonstrates that this bacterial species has apparently uncoupled the hypermutability of tetranucleotides that mediate PV from some important MMR functions. In the context of the biology of commensal and virulence behaviour of pathogenic bacteria, these findings are of particular interest because it has been proposed that mutations in MMR genes are an important source of adaptive evolution (Oliver et al., 2000; Giraud et al., 2001).

RdΔpolI mutants were viable, but exhibited reduced growth rates and filament formation. This latter phenotype complicates analysis of mutation rates. PV frequencies were determined for individual colonies by plating serial dilutions of the colony, counting the number of variant and parental colonies that were formed on these plates, and then estimating, from these numbers, the proportion of variants in the diluted colony. If filaments are present in the diluted colony, then multiple cells form one colony, and if only parental cells are in filaments, then PV frequencies would be overestimated. However, variant cells are generated by both mutational events and cell division. If cell division is the dominant event (i.e. generating 90% or greater of variant cells), then variants are as likely to be present in filaments as parental cells. In this paper we have assumed that there was an equal proportion of variant and parental cells in filaments and that therefore RdΔpolI mod/lacZ PV rates were comparable with those of the parental strains. The observation that PV rates of RdΔpolIGΔZ–AT20 (and related variants) were identical to those of RdGΔZ–AT20 (Table IV), is an empirical demonstration that this assumption is valid.

Inactivation of polI increased mutation rates of a tetranucleotide repeat tract in Hi (Table III). Hi Pol I is likely to have the same or similar functions as the Ec enzyme because these species are relatively closely related and their polI genes are 77% similar (Table I). Ec Pol I has 5′>3′ exonuclease, 3′>5′ exonuclease and DNA polymerase functions, with the latter two being activities of the ‘Klenow’ fragment (encoded by the 3′ portion of the gene). Strain RdΔpolI has a deletion of amino acid residues 348–571 in polI and an antibiotic cassette inserted at this position in the gene. 5′>3′ exonuclease activity is likely encoded by residues 171–277 and it is possible, therefore, that strain RdΔpolI retains some 5′>3′ exonuclease activity, although it is also likely that no activity is present due to disruption of transcription by the 2.7 kbp tetracycline cassette. In Ec, loss of either the polymerizing or 5′>3′ exonuclease activity of Pol I increased the mutation rates of dinucleotide repeat tracts (Morel et al., 1998). However, only loss of 5′>3′ exonuclease activity increased mutation rates independently, and then only partially, of the induction of SOS response. Depression of SOS (by inactivation of lexA), in the absence of other mutations, also destabilized these microsatellites in Ec (Morel et al., 1998). Major potential sources of mutations in these microsatellites during an Ec SOS response are the SOS inducible ‘error-prone’ DNA polymerases, encoded by polB, dinB and umuC/umuD. The Hi genome sequence lacks homologues of each of these genes (Eisen and Hanawalt, 1999; McKenzie and Rosenberg, 2001) and it therefore seems less likely that the Hi SOS response has a role in destabilization of microsatellites. Our inability to inactivate the Hi lexA homologue (despite the Hi genome lacking a sulA homologue, whose inactivation is required for deletion of lexA in Ec) prevented a direct investigation of any possible effect of the Hi SOS response. However, a possible contribution of the SOS response to the elevated PV rates of the polI mutants was investigated by generating RdΔpolI strains carrying insertional mutations of recA as absence of the RecA protein should prevent induction of the Hi SOS response. These mutants displayed PV rates similar to the parental ΔpolI strains (Table III), suggesting that SOS induction is not responsible for the elevated tetranucleotide PV rates in Hi polI mutants. Whilst a contribution from induction of another stress-related system or some other indirect pleiotropic effect cannot be excluded, it seems most likely that the destabilization of tetranucleotide repeat tracts observed for Hi polI mutants was due to perturbation of a process in which Pol I is intimately involved.

Ec Pol I is involved in both nucleotide excision repair (performing ‘gap’ repair DNA synthesis in conjunction with DNA helicase II, the product of uvrD; for a review see Sancar 1996) and processing of Okazaki fragments (Okazaki et al., 1971). Tetranucleotide repeat tracts were not destabilized by mutation of uvrD in Hi, indicating that inactivation of nucleotide excision repair does not increase the mutation rates of such tracts. Our results suggest, therefore, that polI mutations in Hi increase mutation rates of tetranucleotide repeat tracts through perturbation of lagging strand DNA synthesis. Surprisingly, dinucleotide repeat tracts were not destabilized in RdΔpolI mutants. One possibility is that more mutations were produced in these tracts, but were repaired by MMR and, therefore, were not detected. A second explanation is that the shorter length of the dinucleotide repeat tracts, i.e. 40 bp (20 5′AT) compared with 64 (16 5′AGTC) or 152 bp (38 5′AGTC), decreased the probability of these tracts being near to the ends of Okazaki fragments, the proposed site of mutation (see below). In yeast, Okazaki fragments can be processed by 5′ flap endonuclease and/or DNA polymerase δ (Jin et al., 2001) and mutation of these enzymes destabilizes microsatellites (Kokoska et al., 1998). Thus, it appears that accurate and efficient Okazaki fragment processing is critical for maintenance of low mutation rates for microsatellites of both eukaryotes and prokaryotes.

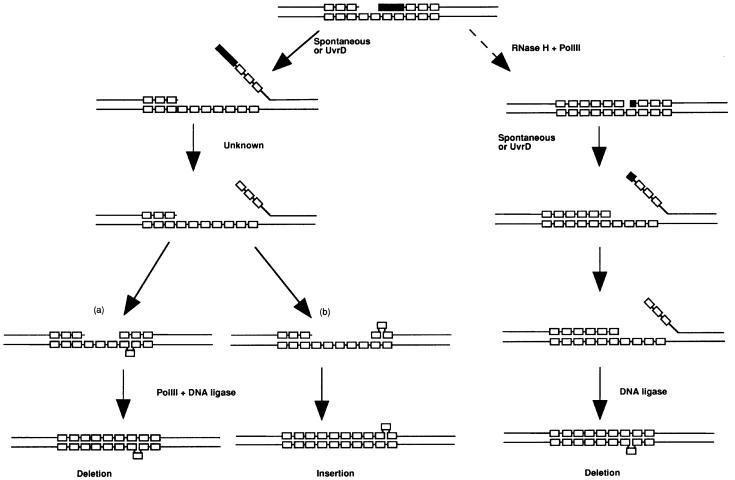

Analysis of tract alterations in 5′AGTC tracts of RdΔpolI mutants demonstrated a significant increase in deletions of repeat units as compared with non-mutant Rd strains (Figure 1). Intriguingly, it has also been reported that DNA polymerase δ mutants exhibit a higher proportion of deletions in microsatellites than wild-type strains (Kokoska et al., 1998). There are a number of possible mutually inclusive mechanisms. First, reduced proof-reading of Okazaki fragments due to the absence of the 3′>5′ and 5′>3′ exonuclease activities of Pol I could decrease repair of ‘slippage’ events. Secondly, delayed joining of Okazaki fragments could increase the probability of strand separation thereby producing more ‘slippage’ events. Thirdly, Pol I deficiencies may result in error-prone joining of Okazaki fragments such that more mutations in repeat tracts are created. However, none of these hypotheses predict that the majority of changes will be deletions of repeat units. Recently, Moolenaar et al. (2000) proposed an alternative pathway for repair of Okazaki fragments, a central feature of which is that the 5′ ends of Okazaki fragments are unwound by UvrD, a 3′>5′ DNA helicase. We propose two possible adaptations of this model to account for the high proportion of deletions in tetranucleotide repeat tracts of Hi polI mutants (Figure 3). In the first model (left diagram), lagging-strand DNA synthesis generates ‘large gaps’ between the Okazaki fragments. The 5′ end of the downstream fragment is unwound allowing removal of all the ribonucleotides and then re-anneals out of register with the template strand but closer to the 3′ end of the adjacent Okazaki fragment. This would result in deletions of repeats because the loops always occur on the template strand. The gap between these two fragments is then polymerized by DNA polymerase III. This template is repaired more efficiently than one in which the loop is on the primer strand (which would create an insertion) because less DNA synthesis is required. The second model is based on the observations that RNA primers are removed in a two-stage process, the first stage of which is shortening by RNase H (Qiu et al., 1999), and that in Ec polA4113 mutants Okazaki fragments retaining 1–3 ribonucleotides persist (Ogawa and Okazaki, 1984). Thus, the first step in this model (Figure 3, right diagram) is that lagging-strand DNA synthesis generates a small nucleotide (0–8) gap adjacent to the 5′ end of an Okazaki fragment that retains 1–3 ribonucleotides. As in the first model, this 5′ end is then unwound and removal of the remaining ribonucleotides can then proceed. In many cases, removal of these ribonucleotides will generate a four (or possibly eight) nucleotide gap. If this occurs, re-annealing with displacement of one or more repeat unit(s) in the template strand (i.e. a deletion) will enable end-joining without further need for polymerization. A similar model was proposed by Okazaki et al. (1971) to explain the increase in deletions observed in Ec polI mutants (Coukell and Yanofsky, 1970). We favour this second model as it obviates the need to speculate on the reasons why DNA polymerase III polymerizes small gaps more efficiently than large gaps, a feature of the first model.

Fig. 3. Models for generation of deletions in Hi tetranucleotide repeat tracts by polI-deficient Okazaki fragment processing. The lagging strand of DNA synthesis is depicted. DNA strands are represented by individual lines, repeat units by open rectangles and RNA primers by filled rectangles. The left diagram shows Okazaki fragments processing for large gaps between the fragments. Step 1: the 5′ end of the downstream Okazaki fragment disassociates from the template strand either spontaneously or as a result of UvrD 3′>5′ DNA helicase activity (as proposed by Moolenaar et al., 2000). Note, large gaps between Okazaki fragments facilitate loading of UvrD onto the template strand and favour unwinding of the downstream fragment. Step 2: removal of the RNA primer by an unknown pathway. Step 3: re-annealing of the primer strand with displacement of one or more repeats in either (a) the template strand or (b) the primer strand. Step 4: gap-filling DNA synthesis performed by Pol III (the only other DNA polymerase encoded by the Hi genome) possibly acting distributively, such that templates with small gaps (a) are filled more efficiently than those with large gaps (b) and sealing of the nick by DNA ligase. The right diagram shows Okazaki fragment processing for templates with small gaps between the fragments. Step 1: removal of the RNA primer by the action of RNase H and gap-filling by Pol III possibly during lagging-strand DNA synthesis prior to disassociation of the holoenzyme. Note, the two Okazaki fragments are separated by a gap of 0–2 nucleotides and the downstream fragment retains 1–3 ribonucleotides. Step 2: unwinding of the 5′ end of the downstream Okazaki fragment either spontaneously or due to the action of UvrD. Step 3: removal of ribonucleotides by an unknown pathway. This step may generate a four nucleotide gap between the ends of two Okazaki fragments. Step 4: re-annealing of the primer strand with displacement of one repeat in the template strand, producing a nicked DNA molecule that is sealed by DNA ligase.

LPS is a major determinant of pathogenesis and many epitopes of this molecule are phase variable. PV of the lic1 locus, whose products synthesize and add phosphorylcholine to LPS, is associated with the occurrence and persistence of Hi in rat and chinchilla models of infection (Weiser et al., 1998; Tong et al., 2000). Thus, PV is likely to be critical for the fitness and virulence of Hi strains in vivo. A theoretical model indicates that strains with high PV rates generate diversity more rapidly by increasing production of variants that exhibit switches in single and multiple PV genes (De Bolle et al., 2000). Through effects on switching rates of single genes or on generation of diversity, trans-acting factors that globally increase rates of PV may influence fitness of this or other bacteria with similar adaptive switching mechanisms. The demonstration that polI mutations increase mutation rates of 5′AGTC repeats and switching rates of an LPS epitope is an indication that Pol I is a factor that globally regulates PV in Hi. However, the polI mutants used in this study exhibit growth defects in vitro that may compromise fitness in vivo. We are currently investigating the role of polI in modulating PV rates and fitness by identifying polI polymorphisms in strains representative of the natural population, and constructing artificial point mutations in this gene.

Multiple simple sequence contingency loci have been found in the genomes of a number of bacterial species. In this context, the Hi genome is unique because it contains almost exclusively tracts consisting of tetranucleotide, or longer, repeat units (Hood et al., 1996; van Belkum et al., 1997; Dawid et al., 1999), whereas, in contrast, the Nm, Hp and Cj genomes, for example, contain multiple loci with mono- or dinucleotide repeat tracts (Saunders et al., 1998, 2000; Parkhill et al., 2000). A striking observation of this work is that Hi MMR does not influence PV rates mediated by tetranucleotide repeat tracts (Table III), but does control PV rates dependent on dinucleotide repeat tracts (Table IV). This result indicates that PV rates of the majority of Hi simple sequence contingency loci are independent of MMR, but are affected by the intrinsic mutability resulting from changes in the length of the tetranucleotide repeat tract (De Bolle et al., 2000). In contrast, PV rates of the majority of loci in Nm are dependent on both tract length and MMR (Richardson and Stojiljkovic, 2001). One consequence of this difference is that mutations in MMR genes may occur more frequently in species reliant on short nucleotide repeats for PV than in Hi or other species where longer repeats are typical. The reasons why such an effect may arise include the following. First, MMR mutations dramatically increase mutation rates of microsatellites containing repeat units of one or two nucleotides. If, as discussed above, global regulators of PV make a major contribution to fitness, then strains with mutations in MMR genes may occur frequently in populations of PV bacteria in which switching is driven by short nucleotide repeats. Secondly, mono- and dinucleotide repeat tracts produce large numbers of slippage events that are repaired by the MutSLH pathway. Multicopy ssDNA molecules containing mismatches cause titration of the MutS protein and enhance mutation rates in Ec (Maas et al., 1996). Thus, a large number of long mono- and/or dinucleotide repeat tracts within a genome could limit the efficiency of MMR activity and lead ultimately to mutation of MMR genes. Interestingly, mutations in MMR genes have recently been found in natural isolates of Nm (Richardson and Stojiljkovic, 2001), and the genome sequences of Cj and Hp lack homologues of all the MMR genes (Eisen and Hanawalt, 1999). Absence of MMR functions gives rise to ‘mutator’ phenotypes, strains with substantially increased global mutation rates. Mutators are found in natural populations of Ec, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium (Matic et al., 1997; LeClerc et al., 1998; Oliver et al., 2000). It has been suggested that mutators may facilitate adaptation to environmental fluctuations by increasing the supply of beneficial mutations, but this hypermutable state must be traded off against the production of deleterious events that have negative effects on fitness (Taddei et al., 1997; Giraud et al., 2001). Intriguingly, Richardson and Stojiljkovic (2001) found some Nm mutants in which PV rates were elevated but global mutation rates remained the same, a further indication that there may be selection against the deleterious effects of a global increase in mutation rates. We propose that Hi has evolved tetranucleotides to maintain the fitness advantages of localized hypermutation while avoiding the deleterious effects implicit in coupling simple repeats to MMR functions.

Materials and methods

Strains

Hi strain RM118, termed Rd herein, is a derivative of strain KW-20, which was used for the sequencing project (Fleischmann et al., 1995) and strain Eagan (RM153) is a type b strain (Anderson et al., 1972). Strains RdGΔZ38R and RdGΔZ17R were created previously (De Bolle et al., 2000). These strains were grown at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) supplemented with either haemin (10 µg/ml) and NAD (2 µg/ml) in liquid media or Levinthal supplement on solid media.

Ec strain DH5α was used to propagate plasmids and was grown at 37°C in Luria–Bertani broth supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/ml), kanamycin (50 µg/ml), tetracycline (12 µg/ml) or chloramphenicol (30 µg/ml).

Inactivation of DNA metabolism genes

The general strategy was to design four oligonucleotide primers (Sigma-Genosys) for each locus (see Table I), which permitted the 5′ end of the gene to be amplified by one pair of primers and the 3′ end by the other pair. The outer primers of each pair carried either a BamHI or an EcoRI site at the 5′ end and the inner primers had a HindIII site at the 5′ end. The PCR products were cloned into PCR2.1 and then released by digestion with either BamHI and HindIII or EcoRI and HindIII. These fragments were then used in a three-way ligation with EcoRI and BamHI-digested pUC18ΔHindIII. These plasmids were linearized with HindIII and ligated to a HindIII fragment carrying a tetracycline cassette (derived from plasmid pHVT1; Danner and Pifer, 1982). A clone of the Hi recA gene interrupted by a chloramphenicol cassette (derived from pACYC184, as described by Kraib et al., 1998) was also created. Plasmid constructs were checked by restriction digestion and sequencing the ends of the inserts, using primers that generate sequences across the multiple cloning site. Automated sequencing was performed with Big-Dye (Perkin Elmer) sequencing kits and an ABIprism 377 (Perkin Elmer) autosequencer. This process created clones of the required Hi genes (see Table I and Results) that were interrupted by an antibiotic cassette and, in nine cases, contained a small deletion.

These plasmids were linearized by digestion with SalI or BamHI and used to transform competent Hi (Herriott et al., 1970). Transformants were selected on BHI plates containing 3 µg/ml tetracycline or 2 µg/ml chloramphenicol. Transformants were checked by hybridizing Southern blots with probes generated using PCR amplification products obtained with the outer two primers for each gene and then labelled with the DIG (digoxigenin) system (Boehringer Mannheim).

Construction of a dinucleotide repeat PV reporter strain

The first step was to create a mod–lacZ fusion construct in which the 5′AGTC repeats were replaced with a multiple cloning site. The region upstream of the repeats was amplified from chromosomal DNA of Hi strain Rd using primers H1RNH2 (De Bolle et al., 2000) and MCS1MOD (5′-CACCGGTACCAGATCTCGAGACGCGTTTATTGCGTTTAAAATAAATT) and the product was cloned into PCR2.1. The mod fragment was released from this plasmid by digestion with KpnI and HindIII and inserted into the same sites in pGreslacZ (De Bolle et al., 2000). A kanamycin cassette was then inserted into the BamHI site downstream of lacZ, as described by De Bolle et al. (2000). The resultant plasmid, pGΔZMCS, contained a mod–lacZ fusion, in which the repeats had been replaced with restriction sites for MluI, XhoI and BglII. The second step was to clone a dinucleotide repeat tract into this plasmid. Two oligonucleotides were designed; primer A had a unique region, a Sau3A site, 20 5′AT repeats and another Sau3A site (5′-TCTCGAGATC {AT}20GATCTGGTACCGGTGGGTG), and primer B (5′-CACCCACCGGTACCAGATC) was complementary to the unique region of primer A. These primers were annealed by mixing 0.5 nmol of primer A with 2 nmol of primer B in 50 µl of 1× standard saline citrate (0.15 M NaCl, 15 mM sodium citrate pH 7) and then incubating the mix consecutively at 96°C for 3 min, 65°C for 10 min, 37°C for 10 min and room temperature for 10 min. Primer B was extended by incubating 5 µl of annealed primers with 10 U Klenow in a 30 µl reaction mix of 1× buffer L (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithioerythritol) (Boehringer Mannheim) and 1 mM dNTPs (2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates) for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by incubating at 65°C for 10 min and then 5 µl of buffer A [33 mM Tris–acetate pH 7.9, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 66 mM potassium acetate, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] (Boehringer Mannheim), 3 µl of Sau3A (10 U/µl) and 12 µl of water were added. This reaction was incubated at 37°C for 2 h followed by 10 min at 65°C. Annealed and digested primers were ligated to pGΔZMCS that had been linearized with BglII. Transformants were selected in Ec using kanamycin and then plasmids were confirmed by sequencing. Plasmids were linearized with ScaI and used to transform competent Hi. Transformants were selected using 10 µg/ml of kanamycin and checked as described above.

Global mutation rate assay

Hi strain Rd or mutant strains were grown on BHI plates overnight. Individual colonies were then transferred into 5 ml of BHI broth and incubated for ∼8 h or overnight (for the RdΔpolI mutants). Dilutions (10–6 and 10–7) were plated onto BHI to estimate the total number of bacteria in the culture, and aliquots (500 µl) onto BHI containing 5 µg/ml nalidixic acid in triplicate to estimate the number of nalidixic acid-resistant bacteria. Mutation frequencies were determined for at least 10 colonies of each mutant. Mutation rates were estimated from these frequencies using the median value by the method of Drake (1991).

Assays for PV rates and mutations in repeat tracts of reporter constructs

PV frequencies, determined as described previously (De Bolle et al., 2000), were measured for eight colonies of two separate transformants (i.e. a total of 16 colonies) for each mutant of each tract size (and for both directions of switching). If the median frequencies differed by less than two-fold for the two transformants, the combined frequencies were used to estimate PV rates (De Bolle et al., 2000). Alterations in the 5′AGTC repeat tracts were determined by PCR amplification of repeat tracts from parental and revertant colony preparations (De Bolle et al., 2000) and either sequencing or gene scanning of the products. For gene scanning, PCR amplification was performed with primer MODP2 and 5′ fluorescently labelled versions of primer LACZB1 (De Bolle et al., 2000). Repeat tracts of parental colonies were amplified with MODP2/LACZB1tet whilst those of revertant colonies were amplified with MODP2/LACZB1fam or MODP2/LACZB1hex. The products of these PCR reactions were mixed together in equal proportions, diluted 1:10 and then 1 µl was mixed with 1.5 µl of deionized formamide, 0.25 µl of loading dye and 0.25 µl of a standard dye mix (GeneScan 2500 TAMRA Size Standard, Applied Biosystems). These samples were denatured by incubating at 95°C for 3 min before electrophoretic analysis using an ABIprism 377 (Perkin Elmer) autosequencer. Gels were analysed using the ABI GeneScan 3.1 program (Perkin Elmer). Fluorescently labelled PCR products derived from samples of known sequence were used as standards on each gel in order to determine the number of repeats in each product. Statistical analyses of PV frequencies and proportions of deletions and insertions were performed with the program Instat 2.0.

Assay for PV rates of an LPS epitope

A polI mutation in Hi strain Eagan was constructed by transforming this strain with chromosomal DNA prepared from either strain RdΔpolI or plasmid pUCΔpolIkan (i.e. the same construct as described above except that the tetracycline cassette was replaced with a kanamycin cassette derived from pUC4kan). Two transformants, EaganΔpolItet (derived from RdΔpolI) and EaganΔpolIkan (derived from pUCΔpolIkan), were obtained and checked by Southern blot analysis (see above). PV experiments were performed as described previously (De Bolle et al., 2000), except that phase variants were detected by transferring colonies from plates onto nitrocellulose filters and probing these filters with antisera as described by Roche and Moxon (1995). The antisera were either a 1:200 dilution of Mab4C4 (kindly provided by E.J.Hansen) followed by a 1:2000 dilution of an anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase conjugate, or a 1:2500 dilution of R38 (a polyclonal rabbit antiserum specific for the Eagan pilus, a kind gift from Janet Gilsdorf) followed by a 1:2000 dilution of an anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugate.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professors E.J.Hansen and Janet Gilsdorf for generous provision of antisera. We also thank Xavier De Bolle for constructing pGΔZMCS and Saba Ghori for help with measuring PV rates. This work was supported by a programme grant from the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Anderson P., Johnston,R. and Smith,D. (1972) Human serum activities against Haemophilus influenzae, type b. J. Clin. Invest., 51, 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrewes F.W. (1922) Studies in group agglutination I. J. Pathol. Bacteriol., 25, 505. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss C.D., Field,D. and Moxon,E.R. (2001) The simple sequence contingency loci of Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis. J. Clin. Invest., 107, 657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coukell M.B. and Yanofsky,C. (1970) Increased frequency of deletions in DNA polymerase mutants of Escherichia coli. Nature, 228, 633–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner D.B. and Pifer,M.L. (1982) Plasmid cloning vectors resistant to ampicillin and tetracycline which can replicate in both E. coli and Haemophilus cells. Gene, 18, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawid S., Barenkamp,S.J. and St Geme,J.W.,III (1999) Variation in expression of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW adhesins: a prokaryotic system reminiscent of eukaryotes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 1077–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bolle X., Bayliss,C.D., Field,D., van de Ven,T., Saunders,N.J., Hood,D.W. and Moxon,E.R. (2000) The length of a tetranucleotide repeat tract in Haemophilus influenzae determines the phase variation rate of a gene with homology to type III DNA methyltransferases. Mol. Microbiol., 35, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake J.W. (1991) A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 7160–7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert K.A. and Yan,G. (2000) Mutational analyses of dinucleotide and tetranucleotide microsatellites in Escherichia coli: influence of sequence on expansion mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2831–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen J.A. and Hanawalt,P.C. (1999) A phylogenomic study of DNA repair genes, proteins, and processes. Mutat. Res., 435, 171–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R.D. et al. (1995) Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science, 269, 496–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsdorf J.R., McCrea,K.W. and Forney,L.J. (1990) Conserved and nonconserved epitopes among Haemophilus influenzae type b pili. Infect. Immun., 58, 2252–2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud A., Matic,I., Tenaillon,O., Clara,A., Radman,M., Fons,M. and Taddei,F. (2001) Costs and benefits of high mutation rates: adaptive evolution of bacteria in the mouse gut. Science, 291, 2606–2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herriott R.M., Meyer,E.M. and Vogt,M.J. (1970) Defined nongrowth media for stage II development of competence in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol., 101, 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood D.W. and Moxon,E.R. (1999) Lipopolysaccharide phase variation in Haemophilus and Neisseria. In Brude,H., Opal,S.M., Vogel,S.N. and Morrison,D.C. (eds), Endotoxin in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, NY, pp. 39–54.

- Hood D.W., Deadman,M.E., Jennings,M.P., Bisercic,M., Fleischmann,R.D., Venter,J.C. and Moxon,E.R. (1996) DNA repeats identify novel virulence genes in Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 11121–11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.H., Obert,R., Burgers,P.M., Kunkel,T.A., Resnick,M.A. and Gordenin,D.A. (2001) The 3′→5′ exonuclease of DNA polymerase δ can substitute for the 5′ flap endonuclease Rad27/Fen1 in processing Okazaki fragments and preventing genome instability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 5122–5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce C.M. and Grindley,N.D.F. (1984) Method for determining whether a gene of Escherichia coli is essential: application to the polA gene. J. Bacteriol., 158, 636–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoska R.J., Stefanovic,L., Tran,H.T., Resnick,M.A., Gordenin,D.A. and Petes,T.D. (1998) Destabilization of yeast micro- and minisatellite DNA sequences by mutations affecting a nuclease involved in Okazaki fragment processing (rad27) and DNA polymerase δ (pol3-t). Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 2779–2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraib A., Schlor,S. and Reidl,J. (1998) In vivo transposon mutagenesis in Haemophilus influenzae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 64, 4697–4702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavitola A., Bucci,C., Salvatore,P., Maresca,G., Bruni,C.B. and Alifano,P. (1999) Intracistronic transcription termination in polysialyltransferase gene (siaD) affects phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol., 33, 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClerc J.E., Payne,W.L., Kupchella,E. and Cebula,T.A. (1998) Detection of mutator subpopulations in Salmonella typhimurium LT2 by reversion of his alleles. Mutat. Res., 400, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton D., Karlyshev,A.V. and Wren,B.W. (2001) Deciphering Campylobacter jejuni cell surface interactions from the genome sequence. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 4, 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J.W. (1993) LexA cleavage and other self-processing reactions. J. Bacteriol., 175, 4943–4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas W.K., Wang,C., Lima,T., Hach,A. and Lim,D. (1996) Multicopy single-stranded DNA of Escherichia coli enhances mutation and recombination frequencies by titrating MutS protein. Mol. Microbiol., 19, 505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matic I., Radman,M., Taddei,F., Picard,B., Doit,C., Bingen,E., Denamur, E. and Elion,J. (1997) Highly variable mutation rates in commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli. Science, 277, 1833–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie G.J. and Rosenberg,S.M. (2001) Adaptive mutations, mutator DNA polymerases and genetic change strategies of pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 4, 586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar G.F., Moorman,C. and Goosen,N. (2000) Role of the Escherichia coli nucleotide excision repair proteins in DNA replication. J. Bacteriol., 182, 5706–5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel P., Reverdy,C., Michel,B., Ehrlich,S.D. and Cassuto,E. (1998) The role of SOS and flap processing in microsatellite instability in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 10003–10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon E.R., Rainey,P.B., Nowak,M.A. and Lenski,R. (1994) Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Biol., 4, 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T. and Okazaki,T. (1984) Function of RNase H in DNA replication revealed by RNase H defective mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 193, 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki R., Arisawa,M. and Sugino,A. (1971) Slow joining of newly replicated DNA chains in DNA polymerase I-deficient Escherichia coli mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 68, 2954–2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A., Canton,R., Campo,P., Baquero,F. and Blazquez,J. (2000) High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science, 288, 1251–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J. et al. (2000) The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature, 403, 665–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Qian,Y., Frank,P., Wintersberger,U. and Shen,B. (1999) Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase H(35) functions in RNA primer removal during lagging-strand DNA synthesis, most efficiently in cooperation with Rad27 nuclease. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8361–8371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A.R. and Stojiljkovic,I. (2001) Mismatch repair and the regulation of phase variation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol., 40, 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche R.J. and Moxon,E.R. (1995) Phenotypic variation of carbohydrate surface antigens and the pathogenesis of Haemophilus influenzae infections. Trends Microbiol., 3, 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A. (1996) DNA excision repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 65, 43–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders N.J., Peden,J., Hood,D. and Moxon,E.R. (1998) Simple sequence repeats in the Helicobacter pylori genome. Mol. Microbiol., 27, 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders N.J., Jeffries,A.C., Peden,J.F., Hood,D.W., Tettelin,H., Rappouli,R. and Moxon,E.R. (2000) Repeat-associated phase variable genes in the complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58. Mol. Microbiol., 37, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia E.A., Kokoska,R.J., Dominska,M., Greenwell,P. and Petes,T.D. (1997) Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on repeat unit size and DNA mismatch repair genes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 2851–2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss B.S., Sagher,D. and Acharya,S. (1997) Role of proofreading and mismatch repair in maintaining the stability of nucleotide repeats in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei F., Radman,M., Maynard-Smith,J., Toupance,B., Gouyon,P.H. and Godelle,B. (1997) Role of mutator alleles in adaptive evolution. Nature, 387, 700–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H.H., Blue,L.E., James,M.A., Chen,Y.P. and DeMaria,T.F. (2000) Evaluation of phase variation of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae lipooligosaccharide during nasopharyngeal colonization and development of otitis media in the chinchilla model. Infect. Immun., 68, 4593–4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H.T., Keen,J.D., Kricker,M., Resnick,M.A. and Gordenin,D.A. (1997) Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 2859–2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belkum A., Scherer,S., van Leeuwen,W., Willemse,D., van Alphen, L. and Verbrugh,H.A. (1997) Variable number of tandem repeats in clinical strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun., 65, 5017–5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ham S.M., van Alphen,L., Mooi,F.R. and van Putten,J.P. (1993) Phase variation of H.influenzae fimbriae: transcriptional control of two divergent genes through a variable combined promoter region. Cell, 73, 1187–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser J.N., Pan,N., McGowan,K.L., Musher,D., Martin,A. and Richards,J.C. (1998) Phosphoylcholine on the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae contributes to persistence in the respiratory tract and sensitivity to serum killing mediated by C-reactive protein. J. Exp. Med., 187, 631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]