Abstract

Tumor multidrug resistance (MDR) presents a major challenge to the efficacy of cancer chemotherapy. Pyroptosis, a form of regulated cell death distinct from apoptosis and unassociated with drug resistance, may restore tumor cells’ sensitivity to therapeutic drugs. Cinobufagin (CS-1) with efficient pyroptosis inducing capability showed the potential for the treatment of MDR cancer. However, the hydrophobic nature, low bioavailability, and possible toxic side effects under high dosage pose significant limitations on its clinical application. In this research endeavor, we have engineered a unique “chemo-gas” hybrid nanocomplexes (HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs) by wrapping CS-1 containing lipofilm onto manganese carbonyl hybrid Prussian blue nanoparticles (PBCO NPs) and modifying the targeting molecule HA on the surface. In vitro studies demonstrated that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, exhibiting high tumor-targeting capability, effectively induced pyroptosis in MCF-7/ADR cells through the Caspase-3/GSDME signaling pathway. In vivo assays indicated a strong inhibitory effect on MDR tumors with low CS-1 cardiotoxicity. In conclusion, this “chemo-gas” integrated therapy provides a new strategy for treating MDR tumors.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-025-03728-w.

Keywords: Multidrug resistant cancer, Pyroptosis, Cinobufagin, Gas therapy, Manganese carbonyl hybrid prussian blue nanoparticles

Background

Globally, breast cancer persists as the predominant cause of cancer-related mortality in women, with chemoresistance posing a major clinical challenge [1, 2]. Although apoptosis-inducing therapies form the cornerstone of conventional chemotherapy and targeted treatments, malignant cells develop multifaceted resistance through mechanisms such as ABC transporter-mediated drug efflux (e.g., P-glycoprotein), activation of error-free DNA repair pathways (e.g., homologous recombination), and epigenetic silencing of pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g., BAX and PUMA) [3, 4]. Therefore, targeting non-apoptotic programmed cell death mechanisms is a promising strategy to circumvent cancer drug resistance.

Pyroptosis is a pro-inflammatory programmed cell death mediated by gasdermin (GSDM) family proteins [5]. This biological process is marked by cell membrane perforation, the expulsion of intracellular components, and a strong inflammatory reaction. Distinct from apoptosis and mechanism of drug resistance, pyroptosis presents a potential therapeutic strategy for addressing drug-resistant breast cancer [6]. Cinobufagin (CS-1), a bufadienolide derived from toad skin glands, induces pyroptosis by activating Caspase-3 and cleaving GSDME, effectively eliminating multidrug-resistant tumors [7, 8]. However, CS-1’s cardiotoxicity limits its clinical application [9]. In theory, combining CS-1 with other drugs to reduce cardiotoxicity is a viable strategy for MDR tumor therapy [10, 11]. Recently, manganese carbonyl (MnCO), which can damage mitochondria and decrease drug efflux in tumor cells via generating CO [12, 13], has been used in combination therapy, such as chemotherapy, gas, etc [14–17]. Although MnCO has the potential to enhance the anti-tumor efficacy of CS-1 against multidrug-resistant (MDR) cancer, the poor tumor-targeting capabilities of both agents necessitate careful consideration for clinical translation.

In contrast to conventional therapeutic agents, which rely on passive diffusion for uptake by both normal and malignant cells, nanomedicines can be designed to specifically target tumor cells [18], thereby facilitating their extravasation and active infiltration into solid tumor tissues [19]. Consequently, nanotechnology presents a promising approach to minimize organ-related toxicity [20–22] and improve the antitumor efficacy of encapsulated therapeutics [23, 24]. Prussian blue nanoparticles (PB NPs) are FDA-approved oral agents for detoxification of radioactive cesium and thallium [25, 26]. Their notable biosafety profile and capacity for efficient drug loading have garnered significant interest in drug delivery [27]. Based on the previous studies [28, 29], we have developed a drug delivery system loaded with CS-1 and MnCO. First, MnCO was attached to the surface of PB NPs (PBCO NPs). Then, pH-responsive lipofilm was employed to encapsulate the CS-1 (CS-1-Lip NPs). The hydration between PBCO NPs and CS-1-Lip NPs in deionized water led to the formation of nanocomplexes (designated as Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs). In order to enhance tumor-specific accumulation, phospholipidated hyaluronic acid (DSPE-PEG2000-HA) was incorporated into the surface of the nanocomplexes to obtain HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs [30]. In addition, the pH-sensitive component of DSPE-PEOz2K within the lipofilm effectively regulates the release of CS-1 under the acidic microenvironment of tumors, promoting synergistic treatment of MDR tumors in conjunction with MnCO. This approach integrates chemotherapy and gas therapy, providing a promising strategy to overcome the physiological barriers associated with tumor tolerance to oxidative stress, aiming to combat MDR cancers.

Materials and methods

Materials

K₃[Fe(CN)₆]·3 H₂O and PVP were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Cinobufagin (CS-1) was supplied by Herbest Co., Ltd. Lecithin, cholesterol, manganese carbonyl (MnCO) and DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd. DSPE-PEOz2K was sourced from Xi’an Ruixi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Chlorin e6 (Ce6) was provided by Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. JC-1, ATP, GSH, and LysoTracker assay kit were obtained from Beyotime. ROS and Calcein AM/PI kit were acquired from Yeasen Biotech Co., Ltd.

Cell lines and animals

Cell lines (MCF-7, HepG2, A2780, MCF-7/ADR, HepG2/DDP, A2780/DDP, HUVEC) were sourced from Xiangya Central Laboratory. All cells were grown in base media (DMEM for MCF-7, HepG2; RPMI-1640 for A2780) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. Drug resistance was sustained by adding 50 ng/mL chemotherapeutic agents: doxorubicin to MCF-7/ADR, cisplatin to HepG2/DDP and A2780/DDP. Female BALB/c nude mice (Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd.) were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions.

Preparation of Prussian blue nanoparticles (PB NPs)

Potassium ferricyanide (660 mg) and PVP (10 g) were dissolved in 200 mL of hydrochloric acid aqueous solution (pH 2.0) within a conical flask. The mixture was stirred at 25 ℃ for 1 h, following by heating at 80 ℃ in an oil bath for 20 h. PB NPs were collected by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 25 ℃, 20 min) after discarding the supernatant.

Preparation of PBCO NPs

PB NPs (5 mg) and MnCO (10 mg) were combined in a brown bottle. Methanol (10 mL) was added, followed by homogenization via ultrasonication. The mixture was sonicated for homogenization, then magnetically stirred at 25 ℃ for 4 h. PBCO NPs were collected by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 25 ℃, 20 min) after supernatant removal.

Preparation of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs

Preparation of Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs: Lecithin (8 mg), cholesterol (1 mg), and DSPE-PEOz2K (0.5 mg) were dissolved in chloroform (5 mL) in a round-bottom flask, followed by addition of CS-1 (0.5 mg). Rotary evaporation (45 ℃, 20 min) removed the organic solvent to yield a homogeneous lipid film. This film was hydrated with deionized water (5 mL) containing PBCO NPs (2.5 mg) under rotary stirring (45 rpm, 37 ℃, 1 h) to form nanocomplexes (termed Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs). The resulting suspension was probe-sonicated (30 W, 2 min) to reduce particle size and then extruded ten times through a 0.22 μm polycarbonate membrane to ensure size homogeneity. Unencapsulated components were eliminated by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 20 min, 4 ℃). The purified Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs were finally resuspended in deionized water.

Surface functionalization of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs: DSPE-PEG2000-HA (320 µg, synthesized per prior methodology [31]) was introduced into purified Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs suspension under magnetic stirring (37 ℃, 500 rpm, 20 min). Hydrophobic interaction-driven conjugation yielded the final targeted nanocomplexes (termed HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs).

Detection of CO and ultrasound imaging ability

Detection of CO: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (Contain PB NPs 1 mg/mL) were added into PBS solutions with different pH values containing FL-CO-1/PdCl2, and samples were taken at different time points to determine the CO release amount.

Ultrasound imaging ability: BALB/c tumor-bearing mice were injected with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs via the tail vein. After 10 min of in vivo circulation, anesthesia with isoflurane, ultrasound imaging of the tumor site was performed (Mindray Resona R9).

Cell cytotoxicity assay

MCF-7, HepG2, A2780, and their drug-resistant variants (MCF-7/ADR, HepG2/DDP, and A2780/DDP) were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h incubation, cells were treated with CS-1 for 48 h. Viability was quantified using the following equation:

|

ROS assay

Intracellular ROS detection by confocal microscopy: MCF-7/ADR, HepG2/DDP, and A2780/DDP cells plated in 24-well plates for 24 h. Cells were then treated with PBS (control) or CS-1 for 12 h. After DCFH-DA staining per manufacturer’s protocol, fluorescence images were captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM).

Flow cytometric analysis: MCF-7/ADR cells were plated in 6-well plates (1 × 10⁵ cells/well) for 24 h. Cells were then treated for 24 h with PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, and HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (equivalent to 1 µM CS-1 and 20 µM MnCO). After trypsinization (EDTA-free), cells were stained with 10 µM DCFH-DA and analyzed for fluorescence intensity via flow cytometry.

Cell apoptosis assay

MCF-7/ADR cells were plated in 6-well plates (1 × 10⁵ cells/well) for 24 h. Cells were treated with PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (equivalent to 1 µM CS-1 and 20 µM MnCO, respectively) for 24 h. After EDTA-free trypsinization, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 100 µL binding buffer. Cell suspensions were stained with 5 µL Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 and 5 µL PI for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Apoptotic cells were quantified using a flow cytometer.

ATP assay

MCF-7/ADR cells were plated in 96-well plates (1 × 10⁴ cells/well) for 24 h. Following incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing PBS, CS-1 (1 µM), PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (with CS-1 and MnCO at 1 and 20 µM, respectively) for 24 h. The supernatant was collected, and ATP levels were quantified using an ATP Assay Kit by measuring luminescence intensity with a microplate reader.

Intracellular GSH detection

MCF-7/ADR cells were plated in 6-well plates (1 × 10⁵ cells/well) for 24 h adhesion. Cells were treated with PBS (control), free CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (1 µM CS-1, 20 µM MnCO) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to two cycles of rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen, each immediately followed by thawing in a 37 ℃ water bath. The lysates were then incubated on ice (5 min) and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 ℃). Supernatants were collected for glutathione quantification using a Total Glutathione Assay Kit.

Mitochondrial membrane potential detection

MCF-7/ADR cells were plated on glass coverslip-coated 24-well plates ( 5 × 104 cells/well) for 24 h adhesion. Cells were then treated with PBS, free CS-1 (1 µM), PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (equivalent to 1 µM CS-1 and 20 µM MnCO) for 8 h. JC-1 staining solution (5 µg/mL in buffer) was added and incubated at 37 ℃ for 20 min in a humidified 5% CO₂ incubator. After removing supernatants, cells were washed twice with JC-1 staining buffer (1X). Mitochondrial polarization was visualized via CLSM.

In vitro targeting and penetration assay

MCF-7/ADR cells were plated in 12-well plates for 24 h adhesion. Cells were treated with free Ce6 (10 µg/mL), Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, or HA + HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs (both containing 10 µg/mL Ce6 and 20 µg/mL PBCO NPs) for 2, 4, or 6 h. Following incubation, nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Cellular uptake was visualized and images were acquired using CLSM.

Penetration ability in tumor 3D spheroids: MCF-7/ADR cells (8 × 10³ cells/well) were seeded in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates and cultured for 7 days to form tumor spheroids. Mature spheroids were incubated with 200 µL of medium containing free Ce6 (10 µg/mL), Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs for 12 h. Spheroids were washed thrice with PBS (pH 7.4) and imaged via CLSM (Z-stack scanning at 20-µm intervals).

In vitro anti-tumor assay

Cell live/dead staining assay: MCF-7/ADR cells were plated on glass-bottom 24-well plates (5 × 10⁴ cells/well) for 24 h adhesion. Cells were treated with PBS, free CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (equivalent to 1 µM CS-1 and 20 µM MnCO) for 8 h. Calcein AM and PI were co-stained at 2 µM each and incubated at 37 ℃ for 30 min. Fluorescence imaging was performed using CLSM.

HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs killing ability in tumor 3D spheroids: MCF-7/ADR cells (8 × 10³/well) were seeded in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates and cultured for 7 d. Spheroids were treated with PBS, free CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (equivalent to 1 µM CS-1 and 20 µM MnCO) in 200 µL medium. Bright-field images were captured on days 0–5 post-treatment using an inverted microscope.

Tumor 3D spheroid live/dead staining: MCF-7/ADR cells (8 × 10³/well) were seeded in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates and cultured for 7 d. Spheroids were treated with PBS, free CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (equivalent to 1 µM CS-1 and 20 µM MnCO) in 200 µL medium for 8 h. Cells were co-stained with Calcein AM and PI (37 ℃, 30 min). Fluorescence imaging was performed using CLSM.

In vivo half-life and targeting assay

In vivo half-life assay: Female BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old) were administered Ce6 and HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs (all containing Ce6 at 2.5 mg/kg), and blood samples were collected at 0.5, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h respectively to obtain serum for determination of fluorescence intensity.

In vivo targeting analysis: MCF-7/ADR tumor-bearing nude mice were administered Ce6, Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, and HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs (all containing Ce6 at 2.5 mg/kg) respectively. Fluorescence distribution images were captured at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h respectively. The mice were then sacrificed, and the fluorescence distribution of their viscera and tumors was photographed.

Biocompatibility assay

Hemolysis analysis: Whole blood was collected from healthy female BALB/c mice via the orbital venous plexus. After centrifugation (3,000 rpm, 5 min), erythrocytes were washed thrice with PBS, to obtain purified red blood cells (RBCs). A 4% (v/v) RBCs suspension in PBS was prepared. The test samples were added to the suspension, which consisted of PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, at final concentrations of 1 µM for CS-1 and 20 µM for MnCO. The mixture was subsequently incubated at 37 ℃ for 4 h. RBCs lysed in pure water served as the positive control (100% hemolysis). Post-incubation, samples were centrifuged (3,000 rpm, 5 min), and supernatant absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Hemolysis percentage was calculated as: Hemolysis (%) = (1 - (experimental group OD540/pure water group OD540)) × 100%.

Coagulation analysis: Fresh whole blood from BALB/c mice was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min (4 °C) to isolate platelet-poor plasma. Plasma aliquots were incubated with thrombin, PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (1 µM CS-1, 20 µg/mL PBCO NPs) at 37 ℃ for 6 h. Optical density at 650 nm was measured using microplate reader.

Zebrafish maintenance and chemical treatment: Collected at 0.5 hpf, zebrafish embryos were maintained in an incubator at 28 ± 1 ℃ in Zebrafish embryo culture medium. PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, and HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (with CS-1 and MnCO concentrations of 1 µM and 20 µM, respectively) were added and incubated at 28 ± 1 ℃ for 96 h. Take photos of zebrafish embryos with an inverted fluorescence microscope every 24 h, and record the heartbeat, body length, and survival rate after the embryos hatch.

Investigation of in vivo anti-tumor efficiency on MDR tumor

Female BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old) were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 10⁷ MCF-7/ADR cells to establish xenografts. When tumors reached ~ 100 mm³, mice were randomized into four groups (n = 5/group): Group I (control), Group II (CS-1), Group III (PBCO NPs), and Group IV (HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs). Treatments were administered intravenously every 48 h. Upon termination, tumors were excised for histopathological analysis with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Ki-67 immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunofluorescence (IF) imaging.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was applied to determine significant differences between groups. Statistical significance thresholds were defined as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Results and discussion

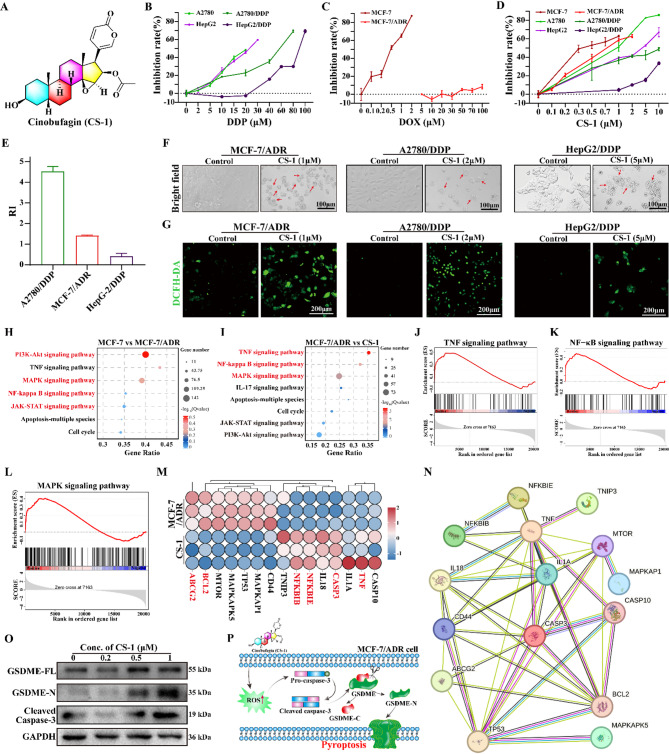

CS-1 induces pyroptosis-mediated cytotoxicity across diverse MDR cells

CS-1, the structure of which is depicted in Fig. 1A, demonstrated a wide-ranging anti-tumor activity [32]. By investigating the cytotoxicity of CS-1 on several MDR cell lines (MCF-7/ADR, A2780/DDP, and HepG2/DDP) as well as their respective parental counterparts, the three resistant cell lines demonstrated significant resistance to their corresponding chemotherapeutic agents (Fig. 1B-C), as previously reported [33–35]. On the contrary, CS-1 exhibited potent cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner against these resistant strains and their parental counterparts with IC50 values ranging from 1 to 5 µM (Fig. 1D). The resistance index (RI) of these cell lines was computed to be less than 5 to CS-1 (Fig. 1E), according to the formula of resistance index (RI) = IC50 of resistant cells/IC50 of parental cells [36]. Microscopic images demonstrated typical pyroptotic morphology in CS-1 treated cells, including cell swelling and the formation of large bubbles [37] (Fig. 1F). DCFH-DA probe staining assay visually demonstrated a significant increase in green fluorescence of three MDR cell lines after treatment with CS-1 for 12 h (Fig. 1G), reflecting the ability of CS-1 to induce high levels of ROS in MDR tumor cells.

Fig. 1.

CS-1 kill MDR tumor cells by inducing pyroptosis. (A) Chemical formula of CS-1. (B) Viability of A2780, A2780/DDP, HepG2, and HepG2/DDP cells following 24 h exposure to varying concentrations of cisplatin (DDP). (C) Viability of MCF-7 and MCF-7/ADR cells after 24 h treatment with different concentrations of doxorubicin. (D) Cytotoxicity of CS-1 across various cell lines (MCF-7, A2780, HepG2, MCF-7/ADR, A2780/DDP, HepG2/DDP) after 24 h treatment. (E) Drug resistance indexes (RI) to CS-1. (F) Morphological images of different cells. (G) Fluorescent images of different cells staining with ROS probe of DCFH-DA. (H) Bubble map of MCF-7 vs. MCF-7/ADR enrichment gene in KEGG pathway. (I) Bubble map of MCF-7/ADR vs. CS-1 enrichment gene in KEGG pathway. (J-L) GSEA analysis. (M) MCF-7/ADR vs. CS-1 heatmap. (N) MCF-7/ADR vs. CS-1 protein interaction network. (O) Western blot analysis of pyroptosis-associated proteins (GSDME, cleaved caspase-3) in MCF-7/ADR cells. (P) Schematic diagram of pyroptosis caused by CS-1

Considering the higher RI and sensitivity to CS-1 (RI = 1.425 ± 0.024), we conducted RNA-seq assay to thoroughly investigate the effect of CS-1 on the gene transcription in MCF-7/ADR cells. The volcano plot showed 4520 upregulated genes and 2256 downregulated genes in MCF-7/ADR cells relative to the MCF-7. In contrast, CS-1 treatment caused the upregulation of 1386 genes and the downregulation of 2175 genes (p ≤ 0.05, fold change ≥ 2) (Fig. S1A-B). The Venn diagram also showed 1943 intersecting genes with common changes among MCF-7, MCF-7/ADR and CS-1 group (Fig.S1C). Among these 1943 genes, 978 genes upregulated in MCF-7/ADR group were inhibited by CS-1, which were similar to those of MCF-7 group. Conversely, 248 genes downregulated in MCF-7/ADR group were upregulated by CS-1, which were similar to that of the MCF-7 group. KEGG assay indicated the high enrichment of drug resistance protein regulatory pathway of PI3K-AKT and apoptotic pathways of MAPK, NF-κB and JAK-STAT in MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig. 1H). In contrast, CS-1 treatment induced high enrichment of pyroptosis-related inflammatory pathways such as MAPK, NF-κB and TNF (Fig. 1I). GSEA analysis also demonstrated that CS-1 treatment caused the activation of pyroptosis-related inflammatory pathways such as TNF, MAPK, and NF-κB in MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig. 1J-L). Heatmap analysis of DEGs showed downregulation of Multidrug resistance-associated protein ABC transporters (ABCG2) and Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic protein in MCF-7/ADR cells with CS-1 treatment (Fig. 1M). PPI analysis indicated that TNF, a master regulator of inflammation, connected NF-κB with Caspase-3 (Fig. 1N). Therefore, we further indicated the related protein expression level of pyroptosis by western blot combining with our reported result [38]. Then, we detected the changes of pyroptosis-associated proteins in MCF-7/ADR cells after treatment with different concentrations of CS-1. As we expected, CS-1 significantly activated Caspase-3 and GSDME-N levels (Fig. 1O). In conclusion, CS-1 can effectively induce TNF related Caspase-3-dependent pyroptosis in MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig. 1P), while may inhibiting ABCG2 to enhance drug concentration, which is urgent for effectively killing tumor cells.

Preparation and characterization of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs

Our study revealed that CS-1 has manifested significant anti-tumor potential in MDR tumors, however, its clinical implementation is limited by the cardiotoxic potential of high-dose administration [39]. To preserve the antitumor efficacy of CS-1 against MDR tumors while minimizing cardiotoxicity, we adopted a combinational strategy of CS-1/CO. MnCO was used as a precursor for generating CO. MTT assay demonstrated MCF-7/ADR cell viability of 48.2% after the combinational treatment of 1 µM CS-1 and 40 µM MnCO (Fig.S2A-B). However, the low targeting and bioavailability of CS-1 and MnCO limit their clinical application. Thus, we engineered a tumor-targeted “chemo-gas” nanocomplexe (HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs) to address these questions. Figure 2A demonstrated that subsequent to lipid encapsulation and hyaluronic acid modification, a 9.5 nm thick film covered the surface of PB NPs. DLS analysis disclosed an increment in particle size subsequent to the encapsulation of MnCO by PB NPs (resulting in a size of 102.7 nm), lipid encapsulation (yielding a size of 157.1 nm), and HA modification (resulting in a size of 160.1 nm), as illustrated in Fig. 2B. Furthermore, alterations in potential were observed. Starting from PB NPs with a value of −28.6 ± 1.6 mV, it changed to PBCO NPs at −25.1 ± 1.2 mV, then to Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs at −36.9 ± 2.1 mV, and finally to HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs with a value of −37.56 ± 1.3 mV (Fig. 2C). Element mapping characterization results indicated that the manganese element in MnCO displays a high degree of overlap with the iron element in PB NPs, suggesting the effective loading of MnCO into PB NPs. Additionally, the detected phosphorus element signal further confirmed successful liposome encapsulation (Fig. 2D and S3A). The UV-vis absorption spectrum demonstrated characteristic peaks of MnCO and CS-1 at 340 nm and 290 nm, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2E. The FT-IR spectra of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs exhibited characteristic absorption peaks corresponding to lipid components (C = O at 1740 cm⁻¹, P = O at 1230 cm⁻¹, and CH₂/CH₃ at 2850 cm⁻¹), MnCO (C ≡ O at ~ 2080 cm⁻¹) and the cyanide bridges of PB NPs (C ≡ N at 2080 cm⁻¹) [40], further confirming the successful integration of hyaluronic acid-modified Lip-CS-1 with PBCO NPs (Fig. 2F). It is noteworthy that ultrasonic treatment hardly affects the release of CO from PBCO NPs (Fig.S3B). UV spectroscopy assay data indicated that the encapsulation efficiency of CS-1 and MnCO were 21.45 ± 4.3% and 69.03 ± 1.13%, respectively (Fig. 2G). Furthermore, the material remained stable for approximately three days in water, PBS, and DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS, which is conducive to its in-vivo drug action (Fig. 2H). Collectively, these results suggest the successful establishment of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis and characterization of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (A) TEM micrographs illustrating the sequential synthesis stages: PB NPs, PBCO NPs, Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, and HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (B) DLS and PDI values for the synthesized NPs at each stage. (C) Evolution of zeta potential throughout the synthesis stages. (D) Element mapping of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (E) UV-vis absorption spectra of the nanocomplexes and their precursors (CS-1, PB NPs, PBCO NPs, Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs), highlighting characteristic peaks. (F) FT-IR spectra of PB NPs, PBCO NPs, and HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (G) Encapsulation rates of CS-1 and MnCO at HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (H) The effect of different solvents on HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs stability

Functional characterization of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs

According to the design features of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, we first investigated the release characteristics of CS-1 and CO (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, the release rate of CS-1 from HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs attained 88.28 ± 1% in 72 h in an acidic environment (pH6.8), which was attributed to the insertion of pH-responsive molecule DSPE-PEOz2K into the lipofilm. Then, using the FL-CO-1/PdCl2 probe (Fig. 3C) [28], we evaluated the CO release capability under microenvironment condition (high levels of H2O2). As shown in Fig. 3D, the CO release profiles of Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs exhibited significant pH-dependent kinetics. Under physiological conditions (pH7.4 + 1 mM H2O2), the NPs demonstrated sustained but limited CO release, accumulating 18.5 ± 0.5 µM at 24 h with a near-linear progression. In stark contrast, an acidic microenvironment (pH5.4 + 1 mM H2O2) triggers rapid CO liberation, culminating in 70.5 ± 0.5 µM by 24 h – representing a 3.8-fold enhancement compared to neutral pH. Subsequently, the FL-CO-1 probe was utilized to further detect intracellular CO in cells subjected to treatment with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, with intracellular H2O2 serving as the substrate. While cells treated with PBS and CS-1 (1 µM) exhibited no increase in fluorescence, a significant enhancement of green fluorescence was observed in cells treated with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (1 µM CS-1, 20 µg/mL PBCO NPs). This enhancement was notably higher than that in cells treated with PBCO NPs (20 µg/mL), as illustrated in Fig. 3E-F. This result suggested that ROS induced by CS-1 can promote CO release behavior. In addition, the CO gas released by MnCO has the potential to form microbubbles within the organism. Owing to their relatively high acoustic impedance, these microbubbles can create a distinct contrast with the surrounding tissues and fluids [41], which provides the possibility for in vivo ultrasound imaging. As expected, an ultrasonic signal was detected in the sample containing 2 mM H2O2 and HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs solution (Fig. 3G). Conversely, no ultrasonic signal was detected in the H2O2 free sample. This result indicated that MnCO could be efficiently released in the high- H2O2 environment, which is similar to the tumor microenvironment (usually containing 100 µM-1 mM H2O2) [42].

Fig. 3.

Functional characterization of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (A) Schematic diagram of CS-1 release and CO generation from HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (B) pH-dependent release profile of CS-1 from HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (C) The working principle of CO probe (FL-CO-1). (D) The amount of CO released from HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (1 mg/mL PB NPs) at the presence of 1 mM H2O2 in PBS with different pH. (E-F) CLSM images (E) and corresponding fluorescence quantification (F) of MCF-7/ADR cells treated with PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (1 µM CS-1, 20 µg/mL PB NPs). Green fluorescence indicates CO release detected by FL-CO-1. (G) Ultrasound images of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs in the presence or absence of H2O2 in vitro. (H-I) CLSM images (H) and fluorescence quantification (I) of MCF-7/ADR cellular uptake of HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs over time (2, 4, 6 h). (J) CLSM images showing uptake in MCF-7/ADR cells incubated for 6 h with Ce6, Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs with free HA pre-treatment. (K) Fluorescence images demonstrating penetration into MCF-7/ADR 3D tumor spheroids after 24 h incubation with free Ce6, Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs. Bars are means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01

Previous studies indicated that HA surface modification enhances nanodrug targeting efficiency through CD44 interaction, a receptor highly expressed on tumor cells [43, 44]. To evaluate cellular uptake, Ce6-labeled HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs were employed. Results revealed a progressive increase in characteristic red fluorescence within tumor cells over time, peaking at 6 h (Fig. 3H-I). Compared to free Ce6 or Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO-treated MCF-7/ADR cells exhibited stronger fluorescence intensity. Conversely, pretreatment with free HA markedly reduced this fluorescence signal (Fig. 3J), confirming CD44-mediated uptake inhibition. Using MCF-7/ADR multicellular spheroids to mimic solid tumors, the red fluorescence at depths of 0 ~ 60 μm was substantially higher in HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO-treated samples than in free Ce6 or Lip-Ce6@PBCO groups (Fig. 3K). Consistent with previous reports [45], these results also demonstrated that HA could facilitate the entry of HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs into MCF-7/ADR cells via interaction with CD44. In conclusion, HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs demonstrate excellent targeting and penetration abilities, which hold great promise for tumor therapy.

HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs effectively kill tumor cells in vitro

The cytotoxicity of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs was initially assessed against MCF-7/ADR cells. As depicted in Fig. 4A, treatment with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs reduced cell viability to 50.5 ± 10%, significantly lower than that achieved with PBCO NPs (95.5 ± 0.69%) or CS-1 alone (68.3 ± 5.5%). Meanwhile, this kind of NPs can significantly inhibit the formation of cell colony (Fig.S4A). Additionally, Live/dead staining similarly demonstrated the most intense red fluorescence in MCF-7/ADR cells treated with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, which reflected the high cell death rate. In contrast, tumor cells treated with PBCO NPs and CS-1 exhibited moderate red fluorescence compared to the group treated with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. As a control group, almost all cells showed green fluorescence after PBS treatment (Fig. 4B). Consistent with these findings, FACS analysis demonstrated that the cell death rate in HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treated cells was 80.46%, which is significantly higher than that of CS-1 treated cells (60.92%) (Fig. 4C-D). To extend these observations to a more physiologically relevant model, 3D spheroids were employed. Following 5 days of treatment with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs, spheroids exhibited loose and disintegrated morphology (Fig. 4E), and live/dead staining showed predominant red fluorescence, confirming low cell viability (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these results highlight the outstanding tumor-killing capacity of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional models.

Fig. 4.

HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs effectively kill tumor cells in vitro. (A) MTT assay and of MCF-7/ADR cells after 24 h treatment with different treatment. (B) Live/dead staining CLSM images of MCF-7/ADR cells with different treatment for 16 h. (C-D) Flow cytometry analysis of MCF-7/ADR cells with different treatment for 16 h. (E) Bright-field image of MCF-7/ADR 3D tumor spheres with different treatment. (F) Live/dead staining CLSM images of MCF-7/ADR 3D tumor spheres with different treatment for 24 h. (G) Bubble map of PBS vs. HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs in KEGG pathway. (H) Heatmap of genes in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway after HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment. (I-J) GSEA analysis of HIF-1 and FoxO signaling pathway. (K) Heatmap of oxidative stress-related genes after HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment. (L) Protein interaction network of oxidative stress-related proteins after HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment. (Ⅰ: PBS, Ⅱ: CS-1 (1 µM), Ⅲ: PBCO NPs (20 µg/mL), and Ⅳ: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (1 µM CS-1 and 40 µM MnCO). Bars are means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Considering the improvement of efficacy of the nanodrug formulation, we further explored the changes in the genes of MCF-7/ADR before and after treatment. RNA-seq analysis revealed profound transcriptomic alterations in MCF-7/ADR cells following HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment. Venn diagram in Fig.S4B identified changes of 12,208 mRNAs following treatment with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. According to the standard of fold change ≥ 2 fold (p ≤ 0.05), HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs caused 1689 gene upregulation and 2298 gene downregulation in MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig.S4C). Meanwhile, KEGG analysis of these genes with reverse changes revealed that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs plays a significant role in the regulation of mitochondrial function-related PI3K-Akt pathway [46], the inflammation-related TNF, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways and oxidative stress-related HIF-1 and FoxO pathways, as well as the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathway (Fig. 4G). Among them, downregulation of OXPHOS-related genes (e.g., COX7C, ATP5F1D, MT-ND1, MT-ND4, and MT-ND6) strongly correlates with mitochondrial electron transport chain impairment, suggesting HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs induce oxidative stress via mitochondrial damage (Fig. 4H). Concurrent activation of HIF-1 (Fig. 4I) and FoxO pathways (Fig. 4J) further supports this hypothesis, as both pathways are redox-sensitive and amplify ROS accumulation under mitochondrial dysfunction. Heatmap analysis indicated the downregulation of antioxidant genes (NQO1, HSPA8, HSPD1, CAT) and mitochondrial fusion protein MFN1/MFN2, while upregulation of mitochondrial oxidative stress-related proteins (TNF, IL-18, IL-1β) in treated MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig. 4K). PPI analysis indicates the central role of HIF-1α, connecting MFN1/MFN2 with TNF, which is associated with Caspase-3-dependent pyroptosis (Fig. 4L). These findings collectively indicated that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs can effectively kill MDR breast cancer cells by inducing mitochondrial oxidative stress.

HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs activate pyroptosis via oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial damage

Given that CS-1 induces pyroptosis in vitro, along with our RNA-seq data following HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment, we investigated whether HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs could induce pyroptosis in MCF-7/ADR cells. The bright field images of cells treated with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs revealed the cell swelling characteristic of pyroptotic cells (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the staining result of T11 dyes, which can discriminate ruptured cell membrane from normal cell membrane, exhibited obvious membrane damage, cell swelling, and content leakage in MCF-7/ADR cells treated with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (Fig. 5A). TEM corroborated these findings, demonstrating significant plasma membrane damage in the HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs group (Fig. 5B). Consistent with membrane disruption, PI staining—which selectively labels cells with compromised membranes—showed markedly increased fluorescence intensity in HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs-treated cells compared to PBS group (Fig. 5C). As plasma membrane integrity loss facilitates the release of cytosolic contents, we quantified lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, a hallmark of pyroptotic cytotoxicity. HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment resulted in a significant elevation of LDH release (10.3 ± 2.3-fold increase relative to PBS group), confirming successful pyroptosis induction (Fig. 5D). Subsequently, we examined whether HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs-induced pyroptosis was dependent on the activation of caspase-3/GSDME pathway. This result was similar to the Fig. 1 and RNA-seq data showing that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs-activated caspase-3 triggers pyroptosis by cleaving GSDME (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs activate pyroptosis via oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial damage. (A) Confocal microscopy images of T11-stained MCF-7/ADR cells following treatment, assessing membrane integrity. (B) Representative bio-TEM micrographs of MCF-7/ADR cells after 8 h exposure to treatments. (C) PI fluorescence imaging of membrane integrity in treated MCF-7/ADR cells. (D) Quantification of LDH release in MCF-7/ADR cells. (E) Western blot analysis of GSDME and cleaved caspase-3 proteins in cells treated for 12 h. (F) Mitochondrial ultrastructure in MCF-7/ADR cells visualized by bio-TEM after 8 h treatment. (G) Mitochondrial morphology assessment using MitoTracker® Red CMXRos in treated cells after 8 h treatment. (H) Cytochrome c release analyzed by western blot after 12 h treatment. (I) JC-1 staining showing mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) changes after 8 h treatment. (J) Intracellular ROS detection via DCFH-DA fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry after 12 h treatment. (K) MitoSOX™ Red staining for mitochondrial superoxide production after 12 h treatment. (L) GSH levels measured after 24 h treatment. (M) extracellular ATP quantification post 24 h treatment. (N) MDA release in MCF-7/ADR cells after 24 h treatment. (O-P) Western blot analysis of p62, Nrf2, P-gp, and ABCG2 expression (12 h treatment). (Q) Schematic diagram of pyroptosis caused by HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. Bars are means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Next, we endeavored to reveal the underlying process through which HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs induces GSDME-mediated pyroptosis. Combined with the RNA-seq results, we investigated whether pyroptosis triggered by HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs necessitates mitochondrial dysfunction. Notably, TEM images revealed that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs significantly enhanced mitochondrial swelling in comparison to the control cells (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, mitochondrial fluorescence staining after treatment with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs also showed severe mitochondrial damage in the cells (Fig. 5G). Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) collapse, often associated with mitochondrial damage, triggers cytochrome c (Cyt C) release into the cytosol. Western blot analysis confirmed a significant increase in Cyt C release from mitochondria in HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs-treated cells (Fig. 5H). Assessment of ΔΨm using the JC-1 probe demonstrated the most intense green fluorescence (indicative of depolarization) in the HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs group compared to other treatments (Fig. 5I). Given the established role of mitochondrial dysfunction in ROS generation and the reported association between ROS and pyroptosis induction in cancer inhibition [47], we hypothesized that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs might elevate cellular ROS levels. Indeed, both fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry analysis confirmed a significant upregulation of intracellular ROS in HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs-treated cells, exceeding levels observed with CS-1 or PBCO NPs alone (Fig. 5J).

Considering that mitochondria are a major source of ROS, we proceeded to investigate whether HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs induces the generation of mitochondrial ROS in MCF-7/ADR cells. As expected, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment triggered a significant upregulation of mitochondrial ROS (Fig. 5K). To assess the resulting oxidative stress and its impact on antioxidant defenses, we measured key biomarkers. First, cellular glutathione (GSH) levels, a critical antioxidant essential for maintaining mitochondrial structural/functional integrity and protecting mitochondrial DNA from oxidative damage, plummeted by 54.9 ± 0.9% in treated cells (Fig. 5L). This severe depletion indicates a profound disruption of the cellular antioxidant system in MCF-7/ADR cells. Further evidence of mitochondrial damage was observed: 1) Extracellular ATP release, a marker of mitochondrial permeability transition, was significantly elevated in HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NP-treated cells compared to PBCO NP-treated controls (Fig. 5M); 2) Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, a well-established biomarker of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress [48], increased dramatically (8.7 ± 1.8-fold) in the NPs-treated MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig. 5N), confirming extensive oxidative membrane damage. Given the established link between oxidative stress sensing and the p62/Nrf2 pathway [49], we investigated their involvement. Western blot analysis revealed that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs significantly suppressed both p62 and Nrf2 protein levels in MCF-7/ADR cells (Fig. 5O), suggesting impaired activation of the endogenous antioxidant response. Importantly, and critically for overcoming MDR [50, 51], HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs significantly downregulated key MDR-associated efflux pumps, including P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and ABCG2 (Fig. 5P). This reduction functionally impairs drug efflux, a primary MDR mechanism. Collectively, these findings underscore the remarkable ability of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs to induce pyroptosis and circumvent drug efflux, thereby facilitating the elimination of multidrug resistant tumor cells (Fig. 5Q).

Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs in vivo

The pharmacokinetic profile of HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs was evaluated by monitoring Ce6 fluorescence intensity in blood samples post-injection. As shown in Fig. 6A, blood samples showed a gradual decrease in fluorescence intensity following intravenous injection. The NPs exhibited significantly prolonged circulation, with a half-life (t₁/₂) of 3.4 h in BALB/c nude mice – 2.3-fold longer than free Ce6 (1.5 h) (Fig. 6B). Real-time fluorescence imaging revealed distinct biodistribution patterns. HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs accumulated preferentially at tumor sites, with fluorescence intensity of Ce6 and Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs increasing progressively and plateauing at 6 h post-injection. Tumor fluorescence intensity in the HA-modified NP group consistently exceeded that of Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs and free Ce6 at 6, 8, and 12 h (Fig. 6C), demonstrating HA-mediated active targeting. In contrast, free Ce6 exhibited weak, rapidly declining fluorescence due to non-specific distribution while the fluorescent intensity of Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs was higher than that in the free Ce6 group due to the EPR effect, and HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs exhibited the strongest tumor fluorescent intensity. Ex vivo analysis at 12 h post-injection showed fluorescence signals primarily localized in the liver and lungs (Fig. 6D), attributable to hepatic metabolism and residual circulating NPs [52]. Notably, minimal cardiac fluorescence indicated reduced cardiotoxicity compared to free Ce6. Tumor fluorescence intensity in the HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs group was 2.6 ± 0.6-fold higher than in the free Ce6 group, confirming enhanced tumor targeting.

Fig. 6.

In vivo biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of Ce6-labeled HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs. (A) Time-dependent blood fluorescence intensity (FI) profiles of free Ce6 vs. HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs. (B) Pharmacokinetic parameters of Ce6 and HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs. (C) Fluorescence images of MCF-7/ADR tumor-bearing mice at various time points following administration of free Ce6, Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs, or HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs (2.5 mg/kg of equivalent Ce6). Tumor sites are denoted by yellow dashed line circles. (D) Fluorescence distribution of major organs and tumors after 12 h post-injection. (E) Ultrasound imaging of tumor in nude mice before and after with HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs injection for 10 min. Bars are means ± SD (n = 3)

We next evaluated the ultrasound imaging potential of HA@Lip-Ce6@PBCO NPs in vivo. Following intravenous injection into tumor-bearing mice, ultrasound imaging revealed a detectable acoustic signal at the tumor site, which was due to the stimulation of endogenous H2O2 in the tumor microenvironment (TME) triggering the release of CO from the NPs. This gas generation significantly amplified the intratumoral acoustic signal compared to pre-injection levels (Fig. 6E). The pronounced signal enhancement demonstrates both successful tumor-targeted delivery of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs and H2O2-responsive CO generation within the TME. Overall, these findings highlight the nanocomplexes’ strong targeting ability and prolonged blood half-life, essential for its therapeutic efficacy in animals.

HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs exhibit potent antitumor activity against multidrug-resistant cancer in vivo

Building on their in vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo tumor-targeting capabilities, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs in nude mice bearing MCF-7/ADR xenografts according to the regimen in Fig. 7A. Compared to PBS group, all treatment groups (CS-1, PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs) showed significantly reduced tumor volumes (Fig. 7B). Ex vivo analysis confirmed striking tumor growth inhibition by HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. Imaging and gravimetric quantification revealed a final tumor weight of 20.2 ± 9.4 mg in the HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NP group versus 112.8 ± 58.6 mg in PBS group (Fig. 7C-D), translating to a tumor inhibition rate (TIR) of 82.2% ± 5.4%. This efficacy significantly surpassed both free CS-1 (TIR: 54.3% ± 5.2%) and PBCO NPs (TIR: 49.5% ± 15.2%) (Fig. 7E). Critically, no significant body weight loss was observed across any group, supporting the biocompatibility of the nanomaterials (Fig. 7F). Moreover, H&E staining demonstrated extensive, demarcated tissue necrosis in all treatment groups (CS-1, PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs), contrasting sharply with the intact morphology and nuclear density of PBS-treated tumors (Fig. 7G). HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment induced the most pronounced reduction in cellular proliferation, evidenced by the lowest Ki67 expression (Fig. 7G). Furthermore, significant upregulation of the pyroptosis executioner GSDME and the apoptosis-to-pyroptosis switch marker cleaved caspase-3 was detected via immunofluorescence in HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NP-treated tumors (Fig. 7H-I). These results demonstrate that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs exhibit potent antitumor activity against MDR breast cancer in vivo.

Fig. 7.

In vivo anti-MDR tumor efficacy of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (A) Schematic illustration of MCF-7/ADR tumor implantation and the dosage regimen (I: PBS; II: CS-1; III: PBCO NPs; IV: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs). (B) Tumor growth curves. (C) The morphological images of tumors in different group. (D) Tumor weights in different group. (E) Tumor inhibitory rates (TIR) in the mice with different treatment. (F) Body weight change of mice. (G) H&E and Ki67 staining of tumor sections. (H-I) Immunofluorescence staining of cleaved caspase-3 and GSDME in tumor tissues. (J) Diagrammatic representation of A2780/DDP tumor implantation and the dosing schedule. (I: PBS group; II: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs group). (K) Tumor growth curves. (L) Excised tumor morphology. (M) Changes of tumor weight with different treatment. (N) TIR of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs treatment. (O) Body weight monitoring. (P) H&E and Ki67-stained tumor sections. (Q) Immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase-3&GSDME in different tumor sections. Bars are means ± SD (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

We further assessed therapeutic activity in an A2780/DDP (cisplatin-resistant) xenograft model using the same regimen (Fig. 7J). HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs achieved a final tumor volume of 38.0 ± 24.5 mm³, markedly smaller than those of PBS group (236.8 ± 59.5 mm³; Fig. 7K). Ex vivo tumor imaging and weight quantification corroborated this potent efficacy: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NP-treated tumors weighed 42.3 ± 12.5 mg, representing a 67.1% reduction compared to PBS group (128.7 ± 57.9 mg) (Fig. 7L-M). The corresponding TIR was 67.2% ± 6.0% (Fig. 7N). Body weight remained stable (Fig. 7O), and histological evaluation recapitulated the MCF-7/ADR findings: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NP-treated A2780/DDP tumors exhibited significant necrosis (Fig. 7P), minimal Ki67 staining (Fig. 7P), and strong induction of cleaved caspase-3 and GSDME characteristic of pyroptosis (Fig. 7Q). These results robustly demonstrate that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs efficiently inhibit the growth of MDR breast tumors and exhibit potent, broad-spectrum activity against diverse MDR cancers in vivo.

Biocompatibility and biosafety evaluation of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs

Given the critical importance of biocompatibility for clinical translation, we rigorously evaluated the safety profile of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs through multiple assays: hemolysis, platelet aggregation, cytotoxicity in normal cells, zebrafish embryo toxicity, and systemic toxicity in tumor-bearing mice. As shown in Fig.S5A-B, all tested formulations (PBS, CS-1, PBCO NPs, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs) exhibited excellent blood compatibility, with hemolysis rates below the 5% safety threshold after 6 h incubation with red blood cells (RBCs). Furthermore, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs significantly suppressed platelet aggregation, as evidenced by an optical density (OD650 nm) value of 94.8% compared to 48.6% for thrombin (Fig.S5C). MTT assays confirmed low cytotoxicity of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. Cell viability in VSMC, NIH/3T3, and H9c2 cells remained above 95% after 24 h exposure, significantly higher than free CS-1 and PBCO NPs in NIH/3T3 and H9c2 cells (Fig.S5D). In addition, zebrafish embryotoxicity testing revealed no significant differences in body length across treatment groups (Fig. 8A-B). Notably, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (122 beats per minute) mitigated the cardiotoxic effect observed with free CS-1 (130 beats per minute), demonstrating a significantly lower heart rate (Fig. 8C). This indicates the nanoformulation effectively reduces inherent cardiac adverse effects.

Fig. 8.

Biosafety evaluation of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs. (A) The microscopic images of zebrafish were treated with PBS, CS-1 (1 µM), PBCO NPs (40 µM), and HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs (n = 5). (B-C) Body length and heart rate of zebrafish with different treatments. (D) Complete blood count of each MCF-7/ADR tumor bearing mice group, including WBC, RBC, PLT, and HGB (I: PBS; II: CS-1; III: PBCO NPs; IV: HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs). (E) Analysis of blood biochemistry in each group of MCF-7/ADR tumor-bearing mice, focusing on liver function indicators such as AST and ALT, as well as kidney function markers like CRE and UREA. (F) H&E stained images of major organs in each group. Bars are means ± SD (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

In vivo biosafety assessment was essential for evaluating the clinical feasibility of nanomedicines. We investigated the effect of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs by performing whole blood cell count and liver and renal function analysis. In MCF-7/ADR-bearing mice, HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs showed good systemic safety profile. Complete blood counts revealed no adverse effects on RBC, PLT, or HGB levels. Importantly, treated mice exhibited a significant decrease in white blood cell (WBC) count compared with PBS, suggesting attenuation of the tumor-associated inflammatory response (Fig. 8D). Liver and kidney function markers (ALT, AST, CRE, URE) remained within normal ranges, confirming no hepatorenal toxicity (Fig. 8E). H&E staining of key organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney) showed no notable lesions or morphological changes (Fig. 8F). Collectively, these results demonstrate that HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs possess excellent biocompatibility, effectively reduced cardiotoxicity compared to the free drug, and low systemic toxicity, supporting their potential for further clinical development.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed a tumor-targeted nanomedicine system (HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs) that combines chemotherapy and gas therapy to combat MDR tumors. The results confirmed the function of HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs for efficient treatment of MDR tumors through pyroptosis, with minimal side effects on normal tissues. HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs inhibit MDR tumor growth through three primary aspects: (1) The modification with HA enhances the targeting capability of the nanomedicine, promoting drug accumulation at the tumor site and increasing the local drug concentration; (2) HA@Lip-CS-1@PBCO NPs could down-regulate Nrf2, thereby disrupting mitochondrial function and down-regulate intracellular ABC transporters, especially P-gp and ABCG2, to limit drug efflux and overcome multidrug resistance, thereby inhibiting the growth of MDR tumors; (3) The synergistic effect of CS-1 and CO could effectively inhibit the growth of MDR tumors by activating Caspase-3 and thereby activating GSDME-mediated pyroptosis. In conclusion, the “chemo-gas” integrated therapy presents a promising approach for the treatment of MDR tumors.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22478103); Key Project of Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2025JJ90010); Key Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (No. 23A0301); Science Project of the Education Department of Hunan Province (No. 24B0889).

Author contributions

W. Q.: Writing – original draft, Validation, Data curation; J. F.: Validation, Funding acquisition, Data curation; W. T.: Validation, Investigation; J. L.: Validation, Investigation; C. X.: Validation, Investigation; Y. C.: Validation, Investigation; C. T.: Validation, Investigation, Funding acquisition; B. L.: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hunan University (Approval No. SYXK-2023-0010).

Consent for publication

All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wensheng Qiu and Jialong Fan contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Chunyi Tong, Email: sw_tcy@hnu.edu.cn.

Bin Liu, Email: binliu2001@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment. JAMA. 2019;321(3):288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong X, Zheng L-W, Ding Y, et al. Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments [J]. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2025;10(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukowski K, Kciuk M, Kontek R. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su L, Chen Y, Huang C, et al. Targeting Src reactivates pyroptosis to reverse chemoresistance in lung and pancreatic cancer models. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15(678):eabl7895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao F. Gasdermins: making pores for pyroptosis [J]. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(10):620–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang Y, Wang Z, Li Q. Pyroptosis of breast cancer stem cells and immune activation enabled by a multifunctional prodrug photosensitizer. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:2405367. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long Y, Fan J, Zhou N, et al. Biomimetic Prussian blue nanocomplexes for chemo-photothermal treatment of triple-negative breast cancer by enhancing ICD. Biomaterials. 2023;303:122369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang S-Y, Gong S, Zhao Y, et al. PJA1-mediated suppression of pyroptosis as a driver of docetaxel resistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu SS, Lin YS, Liang WZ. Investigation of cytotoxic effect of the Bufanolide steroid compound Cinobufagin and its related underlying mechanism in brain cell models [J]. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021;35(10):e22862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang J, Ding N, Liu X, et al. Prognostic value of the baseline systemic immune-inflammation index in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: exploratory analysis of two prospective trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;32:750–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong L, Ding J, Zhu L, et al. Copper carbonate nanoparticles as an effective biomineralized carrier to load macromolecular drugs for multimodal therapy. Chin Chem Lett. 2023;34(9):108192. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Jing D, Yang J, et al. Glucose oxidase-amplified CO generation for synergistic anticancer therapy via manganese carbonyl-caged MOFs. Acta Biomater. 2022;154:467–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu D, Liu Z, Li Y, et al. Delivery of manganese carbonyl to the tumor microenvironment using tumor-derived exosomes for cancer gas therapy and low dose radiotherapy. Biomaterials. 2021;274:120894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong H, Chen G, Li T, et al. Nanodrug augmenting antitumor immunity for enhanced TNBC therapy via pyroptosis and cGAS-STING activation. Nano Lett. 2023;23(11):5083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Zhang R, Lu Y, et al. Acid-unlocked switch controlled the enzyme and CO in situ release to induce mitochondrial damage via synergy. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:2312416. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Dang J, Liang Q, et al. Thermal-responsive carbon monoxide (CO) delivery expedites metabolic exhaustion of cancer cells toward reversal of chemotherapy resistance [J]. ACS Cent Sci. 2019;5(6):1044–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opoku-Damoah Y, Xu ZP, Ta HT, et al. Ultrasound-responsive lipid nanoplatform with nitric oxide and carbon monoxide release for cancer sono-gaso-therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2024;7(11):7585–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han J, Dong H, Zhu T, et al. Biochemical hallmarks-targeting antineoplastic nanotherapeutics. Bioact Mater. 2024;36:427–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juthi AZ, Aquib M, Farooq MA, et al. Theranostic applications of smart nanomedicines for tumor-targeted chemotherapy: a review [J]. Environ Chem Lett. 2020;28(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su X, Zhang X, Liu W, et al. Advances in the application of nanotechnology in reducing cardiotoxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy [J]. Sem Cancer Biol. 2021;86:929–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song G, Chenlu Z, Junru L, et al. Exosome-based nanomedicines for digestive system tumors therapy [J]. Nanomedicine. 2025;20(10):1167–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y, Huang Y, Zhou F, et al. Macrophage-targeted nanomedicine for chronic diseases immunotherapy. Chin Chem Lett. 2022;33(2):597–612. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Z, Shang Y, Lin C, et al. Targeted covalent nanodrugs reinvigorate antitumor immunity and kill tumors via improving intratumoral accumulation and retention of doxorubicin [J]. ACS Nano. 2025;19(2):2315–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong T, Zhou W, Tan S, et al. A cooperation tale of biomolecules and nanomaterials in nanoscale chiral sensing and separation. Nanoscale Horiz. 2023;8(11):1485–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang P, Sun S, Bai G, et al. Nanosized Prussian blue and its analogs for bioimaging and cancer theranostics. Acta Biomater. 2024;176:77–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, Long Y, Fan J, et al. Biosafety and biocompatibility assessment of Prussian blue nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. Nanomedicine. 2020;15(27):2655–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Cheng L. Multifunctional Prussian blue-based nanomaterials: preparation, modification, and theranostic applications [J]. Coord Chem Rev. 2020;419:213393. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao C, Sun Y, Fan J, et al. Engineering cannabidiol synergistic carbon monoxide nanocomplexes to enhance cancer therapy via excessive autophagy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(11):4591–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long Y, Wang Z, Fan J, et al. A hybrid membrane coating nanodrug system against gastric cancer via the VEGFR2/STAT3 signaling pathway. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(18):3838–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Opoku-Damoah Y, Zhang R, Ta HT, et al. Simultaneous Light-Triggered release of nitric oxide and carbon monoxide from a Lipid-Coated upconversion nanosystem inhibits colon tumor growth [J]. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(49):56796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen B, Zhao Y, Lin Z, et al. Apatinib and Gamabufotalin co-loaded lipid/Prussian blue nanoparticles for synergistic therapy to gastric cancer with metastasis [J]. J Pharm Anal. 2023;14(5):100904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai C-L, Zhang R-J, An P, et al. Cinobufagin: a promising therapeutic agent for cancer [J]. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2023;75(9):1141–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng Y, Li X, Dong C, et al. Ultrasound-augmented nanocatalytic ferroptosis reverses chemotherapeutic resistance and induces synergistic tumor nanotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;32:2107529. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu C, Ding B, Zhang X, et al. Targeted iron nanoparticles with platinum-(IV) prodrugs and anti-EZH2 SiRNA show great synergy in combating drug resistance in vitro and in vivo [J]. Biomaterials. 2017;155:112–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Kou Q, Su Y, et al. Combination therapy based on dual-target biomimetic nano-delivery system for overcoming cisplatin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Q, Lv X, Dong Y, et al. IMB5036 overcomes resistance to multiple chemotherapeutic drugs in human cancer cells through pyroptosis by targeting the KH-type splicing regulatory protein. Life Sci. 2023;328:121941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao M, Sun Q, Zhang H, et al. Bioinspired nano-photosensitizer-activated Caspase-3/GSDME pathway induces pyroptosis in lung cancer cells. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(26):e2401616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao Z, Zhu Y, Yang P, et al. Pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics. 2022;12(9):4310–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bick RJ, Poindexter BJ, Sweney RR, et al. Effects of chan su, a traditional Chinese medicine, on the calcium transients of isolated cardiomyocytes: cardiotoxicity due to more than Na, K-ATPase blocking. Life Sci. 2002;72(6):699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao C, Tong C, Fan J, et al. Biomimetic nanoparticles loading with gamabutolin-indomethacin for chemo/photothermal therapy of cervical cancer and anti-inflammation [j]. J Controlled Release. 2021;339:259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Zhang J, Lv X, et al. Mitoxantrone as photothermal agents for ultrasound/fluorescence imaging-guided chemo-phototherapy enhanced by intratumoral H2O2-induced CO [j]. Biomaterials. 2020;252:120111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu L-H, Wan Y, Qi C, et al. Nanocatalytic theranostics with glutathione depletion and enhanced reactive oxygen species generation for efficient cancer therapy [J]. Adv Mater. 2021;33(7):e2006892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X, Zhou R, Hao Y, et al. A CD44-biosensor for evaluating metastatic potential of breast cancer cells based on quartz crystal microbalance. Sci Bull. 2017;62(13):923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang C, Chen Y, Zuo Y, et al. Dual targeting of FR + CD44 overexpressing tumors by self-assembled nanoparticles quantitatively conjugating folic acid-hyaluronic acid to the GSH-sensitively modified Podophyllotoxin [j]. Chem Eng J. 2025;505:159276. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang J, Tian X, Zhou M, et al. Shikonin and chitosan-silver nanoparticles synergize against triple-negative breast cancer through RIPK3-triggered necroptotic immunogenic cell death. Biomaterials. 2024;309:122608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao T, Zhang X, Zhao J, et al. SIK2 promotes reprogramming of glucose metabolism through PI3K/AKT/HIF-1α pathway and Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in ovarian cancer [J]. Cancer Lett. 2019;469:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Wu Z, Zhu M, et al. ROS induced pyroptosis in inflammatory disease and cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1378990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye B, Hu W, Yu G, et al. A cascade-amplified pyroptosis inducer: optimizing oxidative stress microenvironment by self-supplying reactive nitrogen species enables potent cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2024;18(26):16967–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moscat J, Karin M, Diaz-Meco MT. P62 in cancer: signaling adaptor beyond autophagy. Cell. 2016;167(3):606–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan J, To KKW, Chen Z-S, et al. ABC transporters affects tumor immune microenvironment to regulate cancer immunotherapy and multidrug resistance [J]. Drug Resist Updates. 2022;66:100905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Z-X, Teng Q-X, Yang Y, et al. MET inhibitor Tepotinib antagonizes multidrug resistance mediated by ABCG2 transporter: in vitro and in vivo study [J]. Acta Pharm Sinica B. 2021;12(5):2609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang A, Meng K, Liu Y, et al. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of nanocarriers in vivo and their influences [J]. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;284:102261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.