Abstract

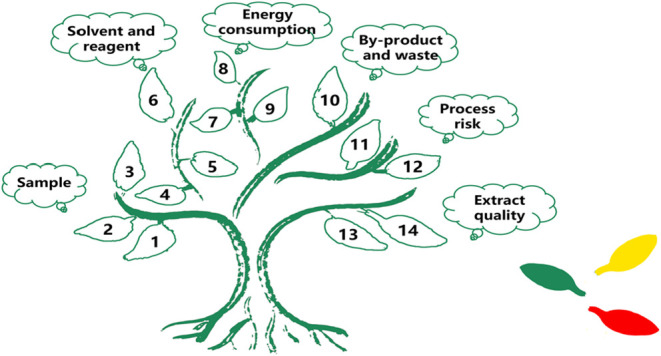

A comprehensive and intuitive evaluation tool, termed the Green Extraction Tree (GET), has been developed to assess the greenness of the sample preparation process in the green extraction of natural products. The assessment criteria integrate the 10 principles of green sample preparation with the 6 principles of green extraction of natural products, encompassing the entire natural product extraction process, including samples, solvents and reagents, energy consumption, byproducts and waste, process risk, and extract quality. The GET employs a “tree” pictogram to classify and evaluate the greenness of various aspects of the natural product extraction process, using three different color markers (green, yellow, red) to represent three distinct levels of environmental impact (low, medium, high) across different processes. In terms of quantitative analysis, the values 2, 1 and 0 are assigned to green, yellow, and red respectively, the final scores are used to conduct a horizontal comparison of the greenness of different processes. The evaluation procedure was conducted using an open-access toolkit that generates the GET pictogram corresponding to each extraction method, facilitating a visual assessment of the greenness of natural product extraction methods. Through five different extraction methods as case studies, the difference of greenness and extraction process to be improved of each method were successfully identified by GET. Additionally, compared to the other representative green assessment tools, GET presents a unique novel perspective and exhibits greater applicability to the natural product green extraction process.

Introduction

Against the backdrop of global sustainable development, the strategic concept of “Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets” has driven the deep integration of environmental protection awareness into high-impact fields such as the chemical industry, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and environmental biology. Meanwhile, since Anastas and Warner proposed the 12 principles of Green Chemistry (GC) in 1998, researchers have focused on reducing the use of dangerous reagents in chemical synthesis to reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances. As a critical branch of GC, Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) from the perspective of analytical chemistry is more concerned with the presence of samples, reagents, energy consumption, sample preparation and analysis methods and other steps resulting in contamination risks. Among them, the sample preparation process is cumbersome, time-consuming, and produces a lot of dangerous laboratory waste, which directly hinders the realization of GC goals. Therefore, Psillakis proposed the ten principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) and developed a roadmap for the comprehensive advancement of more environmentally friendly analytical methods, with green sample preparation serving as the foundational starting point.

While these principles have clarified the direction of GC development, researchers have further developed a series of greenness assessment tools to validate method sustainability. , By using a variety of “green index” evaluation criteria, the greenness of the novel analytical method can be evaluated to confirm whether the method meets the GAC standard. Gałuszka proposed the semiquantitative greenness assess tool called Analytical Eco-Scale (AES), which based on assigning penalty points to each aspect that decreases the procedure’s greenness. From the total score of 100, penalty points were given for each analysis parameter that did not meet the ideal in the analysis process. The higher the final score after deduction, the greener the method was. The Green Chemistry Centre of Excellence at the University of York and Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, have developed a unified measurement Toolkit (CHEM21 Toolkit) for assessing the sustainability of reactions. Based on the National environmental methods index (NEMI), Wasylka developed Green Analytical Procedures Index (GAPI) to evaluate the greenness of the entire analysis method from sample collection to the final product, through a specific symbol with five pictograms, the visualization shows the environmental impact involved in each step of the method. Subsequently, a modified GAPI (MoGAPI) and complex modified GAPI (ComplexMoGAPI) were launched to address the limitation of GAPI that it could not be used to calculate the total greenness score of different analytical methods. , AGREEprep, a sample preparation-specific metric, systematically evaluates the environmental impact of solvents, reagents, waste, energy, and sample throughput, using weighted scoring and visual pictograms for qualitative-quantitative analysis. Moreover, an alternative metric called Sample preparation metric of sustainability (SPMS) presents results in a clock-like diagram, displaying greenness scores for key preparation parameters, primarily for distinguishing closely related microextraction methods.

These greenness metric tools mainly focus on the development of green analysis methods. In addition to sample preparation, they also consider the instruments and technologies involved in sample collection and analysis, etc., and evaluate the accuracy, sensitivity, selectivity and precision of the developed separation analysis methods, which is conducive to the improvement of these methods. − However, their GAC-centric design limits specificity for natural product green extraction: they are tailored for pretreatment of biological/environmental samples (e.g., laboratory-scale liquid/solid microextraction) and fail to assess the unique environmental impacts of natural product extraction, such as raw material sustainability, extract quality stability, and industrial scalability. For example, in the research on the extraction of bioactive compounds from date palm waste, various novel extraction techniques were used, yet existing green assessment tools mainly based on the analysis process are difficult to fully achieve the green assessment of natural product extraction. Therefore, it is clear that special evaluation systems need to be developed to assess the greenness of natural product green extraction methods. Furthermore, there is a large range of parameters affecting the greenness of the preparation of natural product green extraction samples. The entire natural product extraction process comprises multiple unit operations, including raw material pretreatment and extract post-treatment. Among these, solid–liquid extraction process as the most critical unit operation, especially in the absence of optimization, which is often time-consuming and labor-intensive, but also consume large volumes of environmentally harmful petroleum-based solvents, while generating substantial waste. Meanwhile, the existing systems also overlook critical criteria for natural products, including target compound extraction efficiency, extract stability, and industrial application potential, making them unsuitable for evaluating or guiding the development of green extraction methods.

On the basis of GC, the concept of Green Extraction of Natural Products (GENP) proposed by Chemat in 2012. In view of the lack of assessment tools for natural product green extraction methods, this work mainly based on the concept and principle of GENP and integrates the ten principles of GSP, completed the development of a greenness metric tool called GET for natural product green extraction process, and take the representative natural product ginseng as an example to carry out a comprehensive and systematic comparison.

The greenness metric tool GET comprehensively evaluates the natural product extraction process using a total of 14 criteria from six aspects, including samples, solvents and reagents, energy consumption, byproducts and waste, process risk assessment and extract quality assessment. It uses a “tree” pictogram for visualization: six “trunks” represent the core dimensions, while “leaves” (color-coded green for low environment impact, yellow for medium, red for high) correspond to individual criteria. Quantitative scoring (2 points for green, 1 for yellow, 0 for red) enables horizontal comparisons of greenness across methods. Compared to existing tools, GET offers three key advantages. It prioritizes natural product extraction needs, such as avoiding endangered raw materials (e.g., wild ginseng) and assessing industrial scalability, addressing gaps in generic tools. And it differentiates critical parameters (e.g., energy consumption quantified to kWh per sample, solvent toxicity graded via NFPA scores) to avoid overgeneralization. In addition, its intuitive “tree” shaped assessment model and clear standard system provide a clear learning framework for students and novice researchers to understand the key elements of green extraction.

Notably, this work focuses on laboratory-scale extraction, with findings providing theoretical and technical references for industrial scaling. Laboratory extraction research is the basis of industrial extraction. Optimizing laboratory extraction conditions and validating greenness via GET could accelerate the translation of green extraction technologies to industrial production, promoting sustainable development in the natural product industry.

Metric Criteria

The GENP is designed to optimize the main input and output substances of the extraction process of natural products. On this basis, the six principles of GSP are integrated, while the innovative perspectives such as the extraction efficiency of target compounds and the prospect of industrial production in the extraction process of natural products are also increased, which together form the 14 criteria involved in GET tool, covering 6 aspects of the entire extraction process of natural products, including sample, solvent and reagent, energy consumption, byproduct and waste, process risk, and extract quality. The metric criteria of GET tool are summarized in Table and discussed in the following.

-

1.

Promote the use of renewable materials.

-

2.

Ensure sample stability and simplify sample storage.

-

3.

Minimize sample amounts.

-

4.

Use safer solvents and reagents.

-

5.

Minimize solvent and reagent amounts.

-

6.

Minimize additional sample preparation steps.

-

7.

Minimize energy consumption.

-

8.

Maximize sample throughput.

-

9.

Maximize the extraction efficiency of target compounds.

-

10.

Minimize byproduct and waste generation.

-

11.

Reduce the risk of health hazards.

-

12.

Reduce operational safety risks.

-

13.

Choose greener analytical detection techniques.

-

14.

Ensure the industrial production prospects.

1. Metric Criteria of Green Extraction Tree.

Criterion 1. Promote the Use of Renewable Materials

Medicinal natural products hold significant importance in the field of medicine, but overdevelopment often leads to the possibility of extinction, such as taxus chinensis, bear bile and other medicinal plants and animal materials. Support for the sustainable cultivation and exploitation of these species will help preserve biodiversity and meet growing market demand, which is also a key issue for sustainable industrial development. Thus, in developing green extraction methods for natural products, sustainable raw materials such as renewable resources and artificial cultivation are encouraged, while endangered species (e.g., wild ginseng, bear bile) must be avoided. For instance, artificially cultivated ginseng (with a 3–5 year growth cycle and standardized planting protocols) can replace wild ginseng in saponin extraction; this not only ensures a stable raw material supply but also prevents the ecological damage caused by overharvesting of wild populations. Additionally, biobased solvents (e.g., ethanol derived from sugar cane fermentation) are preferred over fossil-based solvents (e.g., petroleum-derived methanol) to align with the principle of renewable resource utilization. To avoid differences in judgments about “sustainability” and “renewability” caused by subjectivity, “sustainable/renewable” materials/solvents could be defined as resources that “can regrow” with a growth/regeneration cycle of ≤ 10 years. Examples include artificially cultivated ginseng and ethanol produced by sugar cane fermentation. Considering the above criteria, the environmental impact of the extraction process is divided into three levels:

Green: sustainable or renewable raw materials and extraction solvents.

Yellow: with 50% or more of materials and solvents as sustainable or renewable resources.

Red: with less than 50% of the materials and solvents as sustainable or renewable resources.

Criterion 2. Ensure Sample Stability and Simplify Sample Storage

Before the extraction of natural products, it is often necessary to deal with the physical and chemical changes that may occur during the collection, transportation and preparation of the sample to ensure that the sample is stable and does not degrade or decay. Proper storage of samples could ensure the quality of extracts, so it is also one of the key steps affecting the quality of the extraction process. The sample storage technology depends on the different types of samples, and can generally be divided into normal conditions (room temperature, dark, dry or ventilated indoor storage), physical conditions (refrigeration, freezing, vacuum) or chemical conditions (acidification, alkalization, preservative conditions), etc. Since the storage process of samples may involve energy consumption or the use of chemicals, the best choice in the preparation of natural product green extraction samples is to select samples with strong stability that can be stored under normal conditions, and the specific evaluation criteria are as follows:

Green: under normal conditions.

Yellow: under appropriate physical or chemical conditions.

Red: under appropriate physical and chemical conditions.

Criterion 3. Minimize Sample Amounts

Although solvent-free extraction is the best choice under the principle of GAC, considering the particularity of natural product extraction, solvents are often needed to complete the diffusion and exchange of bioactive ingredients in the sample. Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), pulsed electric field (PEF) and other methods to enhance the extraction process have been applied to the extraction of natural products. Among them, the size of sample often affects the amount of solvents, reagents, consumables, and energy consumption required. In the laboratory extraction, using smaller sample sizes significantly reduces the time and resource costs associated with the extraction process, while also increasing the potential for high-throughput and automated extraction processes. Compared with macro-scale extraction technologies, a range of microextraction techniques including liquid-phase microextraction, and magnetic solid-phase extraction are currently applied to the extraction of natural products with smaller sample size and less solvent. However, the extreme reduction of sample size will lead to the decline of the repeatability and stability of the extraction method, so the sample extraction scale should be reduced as far as possible on the premise of ensuring the repeatability of the extraction method:

Green: sample amounts <0.1 g.

Yellow: sample amounts 0.1–1g.

Red: sample amounts >1g.

Criterion 4. Use Safer Solvents and Reagents

Due to the high solubility and selectivity of organic solvents to compounds, the extraction of bioactive ingredients from natural products relies heavily on organic solvents. However, most organic solvents exhibit volatility, flammability, explosion risks and often possess biological toxicity, which is one of the reasons for environmental pollution and greenhouse effect, and most of the sources belong to nonrenewable resources. Considering safety, environmental and economic factors, the principles of GSP and GENP both refer to the use of safer green solvents or reagents. In the extraction of natural products, the green solvents reported so far mainly include water, supercritical carbon dioxide, biobased solvents, and eutectic solvents. Most petrochemical solvents belong to nongreen solvents, but ethanol is special. Although it comes from petrochemical raw materials, it has certain renewability (can be prepared by biological fermentation), and can be considered as a relatively green solvent under certain conditions, so it is classified as green. However, in addition to experimental researches such as analysis and detection, the ultimate goal of natural product extraction is its application in health fields such as pharmaceuticals, so the safety of green solvents should also be considered in solvent selection. Considering the feasibility of green solvents in extraction applications, the specific evaluation criteria for this part are as follows:

Green: green solvents and other safety reagents used.

Yellow: green solvents and other petrochemical solvents used.

Red: only petrochemical solvents used.

Criterion 5. Minimize Solvent and Reagent Amounts

While the sample size is confirmed, the solid–liquid ratio is often optimized in the development of natural product extraction methods, and the minimum extraction solvent is used as far as possible under the premise of ensuring the highest extraction efficiency. For instance, a higher ratio of solid to liquid (50 mL/g) compared to 20 mL/g may lead to excessive dilution of the raw material, affecting the extraction effect and reducing the quality of the extract, while the waste liquid will also increase the production cost and environmental impact.

In addition, in the extraction process, there are acid–base reagents used to adjust pH value. In the extraction and detection of some components, derivatization reagents may be used, such as phenyl isothiocyanate for amino acid detection; There are also organic solvents used for extraction and separation, such as hexane, ethyl acetate, etc. When using these reagents, they need to be selected according to the extraction target and sample characteristics, and at the same time follow the principle of minimizing the amount of use. Therefore, consistent with Criteria 3 for minimizing the sample size, reducing the scale of extraction solvent is helpful to reduce the extraction cost while reducing the impact on the environment.

Green: solvent and reagent amounts <10 mL (<10 g).

Yellow: solvent and reagent amounts 10–100 mL (10–100 g).

Red: solvent and reagent amounts >100 mL (>100 g).

Criterion 6. Minimize Additional Sample Preparation Steps

The sample preparation method in the extraction process of natural products usually consists of multiple extraction steps, the accumulation of each step may lead to sample loss and increase of operation steps, thus reducing the precision and repeatability of the extraction method. Simplifying extraction operations by integrating processes represents a key trend in sample preparation, one that exerts a positive influence on the greenness of methods. However, owing to the distinct physicochemical properties of certain compounds during the extraction of natural products, additional operations such as derivatization (for example, amino acids in ginseng can be determined by HPLC only after derivation), acid hydrolysis (for example, the protein and polypeptide in ginseng were hydrolyzed by hydrochloric acid to complete the detection of amino acids), dialysis (for example, the total polysaccharides in ginseng were extracted and purified), and digestion (for example, the determination of trace elements after the decomposition of organic matter in ginseng) should be carried out after sample extraction. In accordance with the eighth principle of GC, derivatization and other additional steps in the sample preparation process are best avoided, as these steps tend to consume large amounts of organic reagents and produce large amounts of waste liquid. Furthermore, it is designed to reduce the use of dangerous reagents, such as strong acids or bases used in derivatization and digestion reactions. Furthermore, additional steps such as derivatization reactions, can affect the repeatability of the analytical method. However, in some cases, derivatization is an indispensable step in the experiment. The greenness evaluation criteria for this part are as follows:

Green: no additional operations beyond the extraction step.

Yellow: simple treatments (liquid–liquid extraction, enrichment, etc.).

Red: advanced treatments (derivatization, hydrolysis, etc.).

Criterion 7. Minimize Energy Consumption

Sample preparation methods and techniques used in the extraction of natural products should be as energy efficient as possible. The principle of GENP suggests several ways to minimize energy consumption: recovering the energy released during extraction, optimizing existing processes, and developing novel processes. In the field of natural product extraction, most extraction methods rely on heating, but there is little research on the recycling of these excessive heat or energy. Basile et al. tried to recover excess heat during rosemary extraction, but the recovery process depended on the size of the heat exchanger. Therefore, when optimizing an existing process or developing an innovative process, the energy consumption advantages of the process and the potential for energy recovery should be considered as much as possible. However, there are intuitive benefits to optimizing existing processes, traditional extraction processes such as steam-distillation and heated reflux extraction (HRE) method have significant energy consumption characteristics, which provides greater optimization space for process energy consumption. For instance, the integration of ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE) with steam-distillation enhances the extraction efficiency of essential oils, while significantly reducing both extraction time and energy consumption. In addition, a range of emerging technologies applied to natural product extraction also contribute to enhancing extraction efficiency, shortening extraction time, and reducing energy consumption, such as MAE, PLE, PEF and other new technologies promote the innovation of extraction technology. These technologies not only have new process principles that traditional processes do not have, but even have the potential to promote the development of new products. Based on the calculation requirements of the total energy consumption of the extraction method in this criterion, the energy consumed (kWh) by each sample is used as the evaluation criteria in this part:

Green: energy consumption <0.1 kWh per sample.

Yellow: energy consumption 0.1–1 kWh per sample.

Red: energy consumption >1 kWh per sample.

Criterion 8. Maximize Sample Throughput

The sample preparation throughput in the extraction process is related to the energy consumption, production efficiency and economic cost in the extraction process. High-throughput extraction process can process more samples per unit time, which can not only enhance production efficiency and reduces time and energy consumption, while helping to reduce the reaction time and exposure risk of the extraction process. In the process of optimizing the sample extraction speed, the preparation time of a single sample in the extraction process could be reduced as much as possible, or parallel processing of multiple samples at the same time could also achieve the purpose of improving the sample preparation throughput. Evaluate the sample extraction throughput:

Green: sample throughput >10 samples h–1.

Yellow: sample throughput 5–10 samples h–1.

Red: sample throughput <5 samples h–1.

Criterion 9. Maximize the Extraction Efficiency of Target Compounds

The extraction efficiency of target compounds is a major indicator for the development of extraction processes for natural products and an effective way to evaluate the feasibility of innovative extraction processes. In the process of innovative process development, extraction conditions are optimized based on extraction efficiency, such as extraction time, solid–liquid ratio and other parameters. Furthermore, extraction efficiency can be employed to assess the reliability and stability of the extraction method, and a stable and efficient extraction method is more conducive to achieving repeatable extraction results, ensuring product quality and process stability. After the completion of innovative process development, researchers usually compare the new process with the existing process to evaluate the extraction parameters of different processes. For example, in the research of ginsenoside extraction, HRE method is often used as the traditional control method. The same sample was extracted separately by different methods, the extraction amount of the target compound was calculated, and the improvement of the extraction efficiency was evaluated by comparing the relative increase rate of the extraction amount between the developed process and the traditional process. In practice, it is necessary to repeat the research of innovative processes and traditional methods, and conduct several parallel experiments for each method to ensure the reliability of the data, and accurately reflects the differences in extraction efficiency between different methods.

Selecting the appropriate extraction process according to the application scenario, selecting the process with higher extraction efficiency can improve the yield of the extract, reduce the waste of raw materials, and reduce the production cost. For example, in CHEM21 Toolkit, reactant yield and extraction efficiency can be directly evaluated based on reaction mass efficiency and process mass intensity. On the premise that compounds are not transformed or degraded, the absolute content value of bioactive compounds in the natural products is relatively fixed, so the extraction efficiency of target compounds in the innovative process cannot be exponentially improved compared with the traditional process. The greenness evaluation criteria for this part are as follows:

Green: compared with existing methods increase by more than 10%.

Yellow: compared with existing methods increase by 5–10%.

Red: compared with existing methods increase less than 5% or no comparative data.

Criterion 10. Minimize Byproduct and Waste Generation

In addition to the target ingredients, the large amount of extraction solvents and reagents used in the extraction also produce byproducts and wastes that need to be recovered and processed, and the disposal of these byproducts and wastes requires additional resources and economic costs. Therefore, the development of natural product extraction methods should take into account the reduction or avoidance of byproducts and waste generation, which is also in line with the fourth principle of GSP and GENP. The byproduct produced in the extraction process has certain economic value, it can be used directly, or it can be used as a reactant in the production of another product. However, waste refers to other materials of no economic value that must be incinerated or landfilled in a waste treatment center to eliminate their environmental impact. By constructing a scientific classification management system for the byproducts and waste from natural product extraction, it is helpful to realize its reduction, resource recovery and harmless disposal. Due to the biodegradability of natural products, the key issue is to reduce the size of waste generated during the extraction process. Waste often includes solvents, reagents and disposable consumables used in the extraction process that have environmental hazards. In addition, if toxic substances contaminate the sample material during the extraction process, the contaminated sample itself should be disposed of as hazardous waste. For example, nontoxic natural products are extracted with pure water, both of which are degradable and environmentally friendly, so they do not need to be disposed of as waste; However, when methanol is used as the extraction solvent of natural products, both methanol and extraction products have biological and environmental toxicity, so they are the wastes produced in the extraction process. The greenness evaluation criteria for this part are as follows:

Green: byproduct and waste generation <1 mL (1g) per gram sample.

Yellow: byproduct and waste generation 1–10 mL (1–10 g) per gram sample.

Red: byproduct and waste generation >10 mL (>10 g) per gram sample.

Criterion 11. Reduce the Risk of Health Hazards

The extraction process not only needs to reduce the impact on the environment, but also needs to evaluate the health hazards of solvents and reagents used throughout the process, in order to safeguard operators’ health against potential hazard. To assess the hazard of the reagents used in the extraction process, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) reagent classification is used to assess the health hazards of the riskiest reagents. The following criteria are recommended:

Green: slightly toxic, slightly irritant; NFPA health hazard score = 0 or 1.

Yellow: moderately toxic; could cause temporary incapacitation; NFPA health hazard score = 2 or 3.

Red: serious injury on short-term exposure; known or suspected small animal carcinogen; NFPA health hazard score = 4.

Moreover, it should be noted that for extraction processes involving special equipment (e.g., microwave extractors, ultrasonic processors), the following assumptions are made in the absence of explicit equipment hazard information to ensure comprehensive health risk assessment: For microwave extractors: It is assumed that the equipment meets basic safety standards, within the safe range for short-term operation, and no additional health hazards beyond mild thermal discomfort from prolonged proximity. Otherwise, it will be rated as NFPA health hazard score 2. For ultrasonic processors: It is assumed that open-type ultrasonic equipment generates noise with the common range for laboratory-scale devices, which may cause mild auditory fatigue during continuous operation, and probe is intact with no risk of solution splashing (rated as NFPA health hazard score 2 if no equipment status data is provided).

Criterion 12. Reduce Operational Safety Risks

Criterion 11 mainly focuses on the health risks of the solvent and reagent used for the operator, while this criterion evaluates the safety risks in the extraction process for the flammability and reactivity of the solvent and reagent, so as to avoid the chemical and physical injuries of the operator such as combustion, explosion and corrosion. NFPA reagent classification is also used to assess the safety risk of the reagents with the greatest risk in the extraction process, and the following criteria are recommended:

Green: no special hazards; NFPA flammability or instability score = 0 or 1.

Yellow: a special hazard is used; NFPA flammability or instability score = 2 or 3.

Red: NFPA flammability or instability score = 4.

In addition, considering some high-pressure extraction equipment with safety risks, it is assumed that the equipment operates at a typical for laboratory-scale high-pressure microwave or pressurized liquid extraction, with no risk of severe pressure-related injuries (e.g., explosions) but requiring basic anti-impact gloves to prevent minor burns from heat dissipation (rated as NFPA health hazard score 2 if no pressure parameter is provided).

Criterion 13. Choose Greener Analytical Detection Techniques

After the extraction is completed, the quality evaluation of their extracts is often carried out to ensure that the products meet the specified quality standards, ensure the purity, active ingredient content and stability of the products. In the process of quality evaluation, it is necessary to further use one or more analytical testing instruments or techniques for analysis. The relatively simple analysis and detection technology with low energy consumption and less solvent and reagent consumption is also the guarantee of green evaluation. However, the choice of analytical detection technology still depends on the physicochemical properties of extracts and the needs of analytical performance. Referring to AGREEprep greenness score for various analytical testing techniques, the criteria for this part are as follows:

Green: simple, low-energy analytical devices (smart phones, spectrometers, etc.).

Yellow: commonly used chromatographic analysis, electrophoresis technology (gas chromatography, liquid chromatography, capillary electrophoresis technology, etc.).

Red: complex, advanced, high-energy analytical equipment (high-energy gas/liquid phase mass spectrometry, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry with high inert gas consumption, etc.).

Criterion 14. Ensure the Industrial Production Prospects

The extraction process innovation of natural products is often carried out in the laboratory on a small scale, and the guidance for industrial large-scale production is limited. It should be noted that industrial scale is not the only goal of natural product extraction in all cases, but in most practical application scenarios, the transformation of laboratory research results into industrial large-scale production is an important direction to promote the development of the natural product industry. For the extraction of some natural products with commercial value, industrial production can improve production efficiency, reduce costs and meet market demand. The consideration of industrial production prospects in the evaluation criteria of the GET tool is to encourage the development of green extraction methods with practical application potential. For some special natural product extraction, such as a small amount of extraction only for scientific research purposes, although large-scale industrial production is not pursued, the evaluation criteria can also provide a reference for its future development direction, such as considering the potential industrialization possibility when optimizing the extraction process. Therefore, this part of the criterion puts forward requirements for the industrial production prospects of innovative extraction processes:

Green: used in industrial production successfully.

Yellow: with potential for industrial production.

Red: laboratory scale research capability only.

Assessment Result

The GET tool utilizes a “tree” pictogram to classify and evaluate the greenness of various aspects of the extraction process of natural products, while using three different color markers (green, yellow, red) to represent three different levels of environmental impact (low, medium, high) in different processes. The six “tree trunks” in the “tree” (Figure ) respectively correspond to six aspects such as samples, solvents and reagents, energy consumption, byproducts and waste, process risk, and extract quality, etc. The “leaves” in different “trunks” represent multiple criteria in this aspect. Under the premise of meeting the greenness metric criteria, the “leaves” are filled with green. In terms of quantitative analysis, the values of 2, 1, and 0 were assigned to green, yellow, and red respectively, the total score (with a maximum of 28 points) was used to conduct a horizontal comparison of the greenness of different processes. The open access toolkit for Supporting Information allows researchers to achieve rapid comparison and analysis of the greenness of multiple extraction methods. By selecting the specific details of each step of the extraction method using this tool, the overall greenness score of the method will be calculated at the base of the tree trunk, enabling rapid quantitative comparison.

1.

Green Extraction Tree pictogram with description.

Assessment Application by GET

Ginseng, the root of Panax ginseng, boasts a long-standing medicinal history owing to its prominent biological activities. It is currently a crucial raw material for diverse functional foods and pharmaceuticals, with substantial global consumption. In this research, GET was used to evaluate the greenness of saponins in ginseng samples by different extraction method.

The mechanical-assisted extraction (MCAE) techniques for ginseng saponins were first assessed. In the MCAE method, 28 mL of pure water serves as the extraction solvent for a sample size of 1g. The extraction can be accomplished through vortex oscillation for 5 min following ball milling, with an energy expenditure of 0.75 kW/h * 0.1 h (planetary ball mill) + 0.018 kW/h * 0.1 h (vortex mixer). Calculated, the energy consumption per sample extraction process is less than 0.1 kWh, enabling the preparation of over 10 samples in 1 h. Given water’s role as the extraction solvent, its generated byproducts, waste, and process risks are deemed green. Although the MCAE process has not yet been employed in industrial production, the corresponding extraction equipment has successfully been applied to the ultrafine grinding of natural products, indicating potential for large-scale industrial production. Ultimately, based on the assignment results, the overall greenness score was 22 points.

The extraction process using the high-pressure MAE method employed 40 mL of 70% ethanol–water as the extraction solvent for 1 g of ginseng powder. After completing the extraction, the solution was repeatedly rinsed and filled to a final volume of 50 mL. Since ethanol is a renewable resource, it meets the green assessment criteria specified in Criterion 1. However, due to the inherent health risks and flammability associated with ethanol, which receive NFPA ratings of 2 for health and 3 for flammability, its green assessment in terms of process risks is classified as yellow. Moreover, since the extract itself poses health and flammability hazards, the resulting 50 mL of extract must be treated as hazardous waste. In the energy consumption assessment, assuming the high-pressure MAE system operates at a power of 1200 W, the energy consumption required for a single sample extraction process is estimated to be 0.2 kWh, allowing for the extraction completion of six samples per hour. Moreover, based on its comparative extraction efficiency with conventional methods, the process demonstrates an enhanced yield exceeding 10% due to the substantial conversion of malonylated saponins into their native forms. However, due to the high temperature and pressure requirements inherent in the extraction process, which demand sophisticated equipment and operational precision, the application of high-pressure MAE technology in industrial production remains relatively limited. In conclusion, the greenness score of this method was 18 points.

Similarly, reports have surfaced regarding the use of nonhigh-pressure MAE techniques in saponin extraction processes. This method involves the development of MAE (300W) extraction procedure using a larger scale ginseng sample (5.0 g) and 50 mL of 80% methanol–water solution. Additionally, to measure the content of saponins after extraction, the process incorporates complex operations such as washing with 50 mL of ether, extracting with 50 mL of water-saturated n-butanol, rotary evaporation drying, and redissolving with methanol, significantly increasing the quantity of generated waste. In the energy consumption assessment, although the extraction process itself is only 30 s, subsequent sample preparation steps such as liquid–liquid extraction add to both the extraction duration and energy consumption. Moreover, compared to other extraction methods, the efficiency increase is less than 5%; simultaneously, the methanol used in the extraction process carries NFPA health and flammability ratings of 2 and 3 respectively, posing moderate toxicity and flammability risks to operators. Currently, MAE technology has gained extensive application in industrial production, utilizing specialized microwave equipment, reactors, and extractors. By optimizing parameters such as microwave power, reaction time, and temperature for different extracts and raw material characteristics, it achieves control over the extraction process. However, in the application of saponin extraction, the technology faces challenges due to the extensive use of organic solvents like methanol and the complexity of the extraction method. Meanwhile, the overall greenness score of this method is 9 points.

In an alternate method employing PLE technology, saponins were extracted from ginseng (2 g) using methanol (25 mL) as the extraction solvent through the Dionex ASE 200 system, which enables simultaneous automated extraction of up to 24 samples. Methanol served as the extraction solvent, yielding red and yellow evaluations under Criterion 1, 4, 10, 11, and 12. Concerning energy consumption, the extraction operated at 500W with a duration of 15 min, but its high-throughput advantage (24 samples) resulted in green assessments under Criterion 7 and 8. However, as it did not compare extraction efficiency with other methods, it received a red evaluation under Criterion 9. Furthermore, PLE technology has already become a mainstream industrial production technique, where solvents, under pressurized conditions, can more effectively permeate and dissolve target components within natural products, thereby boosting extraction efficiency and yield. Based on the assignment results, the overall greenness score of this method is 14 points.

In the final method, PEF technology was employed for saponins extraction, combining 50 g of ginseng with 4 L of 70% ethanol–water solution for extraction under high-voltage pulses. The large scale of the sample and extraction solvent leads to significant environmental impact during the subsequent waste treatment process. In terms of energy consumption, extraction power for natural products typically ranges from several thousand to tens of thousands of watts, but given its short extraction time (2 min), the estimated energy consumption for a single sample extraction process is between 0.1–1 kWh, with an extraction efficiency improvement of approximately 8.18% compared to the common HRE method. Moreover, due to ethanol’s potential health and flammability risks, it is marked yellow in two process risk assessment criteria. Overall, as a nonthermal heat transfer extraction technique, PEF method, considering specific natural products raw material characteristics, extraction objectives, cell structure, and other factors, can efficiently extract bioactive components in extraction processes. However, the PEF technology for natural products is still in the laboratory research and exploration stage, with limited application in industrial production due to its high requirements for voltage intensity and equipment. Ultimately, the overall greenness score of this method is 16 points.

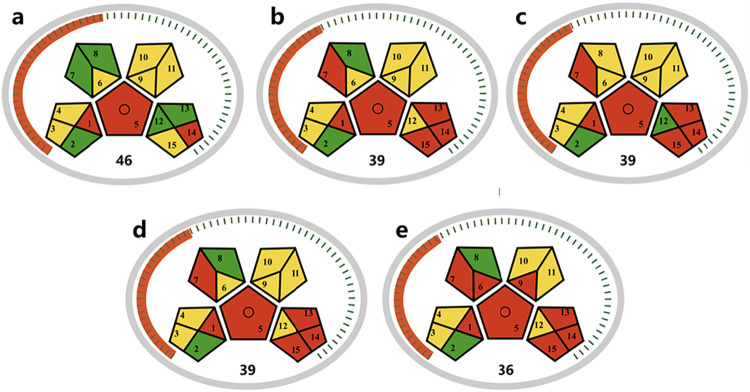

The evaluation results shown in Figure depict the greenness of five different extraction processes for saponins in ginseng, while the color distribution of the leaves allows for the identification of extraction processes that need improvement. The visualization results indicate that the MCAE (a) methods were the most environmentally friendly, although it still has 4 yellow leaves and 1 red leaves. Optimizing the sample amount and solvent can turn two “leaves” green; improving the extraction efficiency of target compounds can also address another red leaf. However, similar to other methods, the prospect of industrial production is closely linked to the industrial system of the entire method, and the result of Criterion 14 is determined when the method is selected. In addition, the selection of subsequent detection and analysis methods can also be further optimized, ultimately resulting in a green tree with all green leaves. In contrast, the MAE (c) methods were the least environmentally friendly among the evaluated methods, with 7 red leaves and 5 yellow leaves. There is significant room for improvement in the 7 red leaves (e.g., 5 g sample, methanol as solvent, waste liquid exceeding 100 mL). It is feasible to use 50% ethanol (renewable) as the solvent, reduce the amounts of sample and solvent, and simplify the post-treatment process by omitting ether washing and rotary evaporation, while simultaneously decreasing the volume of waste generation.

2.

Evaluation of green extraction profiles of saponins from natural products based on Green Extraction Tree: MCAE (a); high-pressure MAE (b); MAE (c); PLE (d); PEF (e).

Additionally, high-pressure MAE (b) method, as a green alternative for saponin extraction, is anticipated to achieve new breakthroughs in various aspects, including solvent and reagent usage, energy consumption, sample throughput, and the generation of byproducts and waste. In the case of the PLE (d) method, the overall score is mainly affected by extraction efficiency, and the sample and solvent consumption are also factors that reduce the greenness score. Seeking alternative solvents that balance environmental friendliness and solubility, supplementing experiments to verify extraction efficiency, and optimizing extraction parameters to reduce sample size are feasible improvement directions for this method. For the PEF method (e), focus should be placed on reducing the usage of sample/solvent and developing industrial equipment. Several new research directions will contribute to greener advancements in this method, such as the integration of multitechniques like PEF-ultrasound, the development of biobased solvent systems, and the design of continuous industrial equipment.

Assessment Tools Comparison

The differences between GET and classical green metric tools such as ComplexMoGAPI, Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI), and Analytical Green Star Area (AGSA) were compared. , Although ComplexMoGAPI has added the evaluation of preanalytical steps and supplemented a total score system on the basis of GAPI, it still takes the entire workflow of analytical methods as the evaluation object, mainly involving the ecological friendliness assessment of analytical chemistry processes. CaFRI, on the other hand, focuses on “carbon footprint assessment” and uses a “human footprint” as the visual carrier, which is applicable to all analytical scenarios requiring quantification of greenhouse gas emissions. However, compared with GET, it fails to meet the specific needs of natural product extraction processes. As a universal greenness assessment tool for analytical methods, AGSA strictly adheres to the 12 principles of GAC and intuitively presents greenness through the area of a star shape. Nevertheless, its evaluation dimensions still center on general analytical scenarios such as “in-situ measurements” and “simultaneous multi-component analysis” and cannot set specific standards for natural product extraction.

In contrast, the evaluation dimensions of GET are more aligned with the needs of natural product extraction. Among its 14 criteria, indicators such as “Promote the use of renewable materials” (avoiding endangered species like wild ginseng), “Ensure the industrial production prospects” (distinguishing between laboratory scale, potential industrialization, and established industrialization), and “Maximize the extraction efficiency of target compounds” (a green rating for an improvement of ≥10% compared to existing methods) directly serve the development and innovation of natural product extraction technologies. Additionally, GET’s energy consumption evaluation is precise to the unit of “kWh per sample”, which is significantly different from the general grading systems used by ComplexMoGAPI and AGSA.

Furthermore, in order to conduct a more comprehensive comparison, using the aforementioned five different methods for extracting saponins, we compared the assessment results of four other representative green metrics tools, including AES, MoGAPI, AGREEprep, and SPMS. In the AES tool, the MCAE method (a) scored 80 points in the Eco-Scale assessment, which is higher than or on par with the scores of 79, 69, 76, and 81 reported for the four novel mechanically assisted extraction methods of saponins using high-pressure-MAE (b), MAE (c), PLE (d), and PEF (e). Similarly, the MAE method (c) received the lowest greenness assessment, while the other four methods had relatively minor score variations. This discrepancy primarily results from the significant impact of the reagents used in each method on the scoring. For instance, MCAE lost 6 points due to the formic acid used as a mobile phase additive during the analysis of target components, whereas in other reported methods, toxic and flammable solvents such as methanol, ethanol, and n-butanol, which carry the same penalty points, were used in larger quantities as extraction solvents. This indicates that greenness of MCAE method (a) has been significantly underestimated. One of the shortcomings of using this tool for evaluating the greenness of natural product extractions is that it combines extraction and analysis processes, thereby lacking specificity for the sample preparation phase.

Same as AES, the MoGAPI tool covers the greenness assessment of the entire analytical method from sample collection to the final product. Figure shows the overall results of the assessment of the five methodologies considered. The MCAE method (a) remains the most environmentally friendly approach for saponin extraction, characterized by the highest number of green pictograms and the lowest number of red ones, with a total greenness score of 46. Its advantages primarily lie in the use of green solvents, low energy consumption, and minimal occupational hazards. Although there is reasonable relative consistency between the assessment results of MoGAPI and GET, there are notable differences in certain aspects. MoGAPI does not seem to distinguish the differences between methods any better than method GET. For instance, MoGAPI scores of high-pressure-MAE (b), MAE (c), and PLE (d) method all having the same total score (39), yet the PEF method (e) is surprisingly deemed the least green. Furthermore, even if there are significant improvements in certain aspects of the extraction process, these may not necessarily be reflected in the corresponding MoGAPI evaluation results. For example, despite the extraction process being designed to minimize the use of organic solvents, it cannot prevent the significant waste of organic solvents during the analysis phase. Therefore, the importance of developing a dedicated metric tool solely for the extraction process becomes evident when considering the amalgamation of sample extraction and analysis processes. The emergence of GET can effectively prevent improvements made in sample extraction from being overlooked by more general tools.

3.

Evaluation of green extraction profiles of saponins from natural products based on MoGAPI: MCAE (a); high-pressure MAE (b); MAE (c); PLE (d); PEF (e).

Unlike AES and MoGAPI, AGREEprep and SPMS focuses more on capturing greenness information during the sample preparation process. Figures and illustrate the greenness evaluation results of the above five methods using AGREEprep and SPMS. In AGREEprep, the MCAE method (a) and the MAE method (c) are rated as the most and least environmentally friendly methods, respectively, while the other three methods do not show significant differences in overall scores. AGREEprep focuses more on the greenness of analytical sample preparation than GET. The 10 criteria focus on the general aspects of analytical sample preparation, such as in situ sample preparation, solvent and reagent use, and material sustainability. And the 14 criteria of GET are more specific and cover the whole process of natural product extraction, from the sustainability of sample raw materials to the quality assessment of extracted products and the consideration of industrial production prospects. For example, in the sample process, AGREEprep only considers general aspects such as the sustainability of materials, while GET pays special attention to whether the raw materials of natural products are endangered species, emphasizing the protection and sustainable use of biodiversity. GET considers not only material sustainability, but also sample stability and storage conditions, which are particularly important for perishable natural products. Compared with AGREEprep, GET makes more detailed distinctions among different category criteria. For instance, in terms of samples and reagents, GET uses two major categories and five minor categories to score them separately, which helps researchers magnify and distinguish the differences in greenness among different methods. AGREEprep uniformly summarizes the common amounts of samples and reagents in “Criterion 5 Minimize Samples, chemical and material amounts”.

4.

Evaluation of green extraction profiles of saponins from natural products based on AGREEprep: MCAE (a); high-pressure MAE (b); MAE (c); PLE (d); PEF (e).

5.

Evaluation of green extraction profiles of saponins from natural products based on SPMS: MCAE (a); high-pressure MAE (b); MAE (c); PLE (d); PEF (e).

Similarly, the evaluation results of SPMS for the MCAE method (a) and the MAE method (c) are the same as those of AGREEprep. Meanwhile, it has better discrimination for the other three methods, especially separately marking the low-throughput drawback that PEF method (e) possesses. However, in the regulations on multiple criteria ranges, compared with GET, SPMS is not applicable to the green extraction of natural products. For instance, in its sample amount range criteria, there is no difference between extracting with a 0.1 g sample and a 1g sample, especially for some valuable samples. Furthermore, the threshold for the amount of extractant used is too small. If 10–100 mL of reagent is used in the extraction of natural products, it will only score 2 points for them. In addition, its evaluation criteria do not take into account the safety of operators involved in some extraction methods, such as high temperature, high pressure, toxicity, etc. This tool is certainly applicable to assessing the greenness of the sample preparation process, but it still needs improvement for the green extraction of natural products.

In addition, both AGREEprep and SPMS achieve quantitative assessment of greenness by quantifying various evaluation indicators. This quantitative approach indeed brings convenience to the assessment work. For example, it allows for an intuitive comparison of the greenness of different methods through specific scores. However, quantification may not necessarily be more advantageous than qualitative assessment. When researchers use quantitative tools to evaluate sample preparation methods, they may overly rely on the final scores, thus weakening the comparison of multiple aspects. For instance, when evaluating several sample preparation methods, one method may perform well in “use safer solvents and reagents” and “minimize sample, chemical and material amounts”, but poorly in “maximize sample throughput”, while another method may perform more evenly in all aspects. If judgments are made solely based on the scores given by the tools, the differences in different aspects of these methods may be overlooked, and it becomes impossible to comprehensively understand the advantages and disadvantages of each method. As a result, it is difficult to propose effective improvement measures for specific problems, and it is also not conducive to promoting the optimization and development of sample preparation methods in all aspects. Therefore, the characteristics of multiple tools should be comprehensively considered, and appropriate assessment tools should be selected according to specific situations.

Figure summarizes the results obtained by evaluating three representative sample extraction methods using the proposed GET tool, alongside the previously reported MoGAPI, AGREEprep, and SPMS metrics. Overall, compared with other tools, GET has a more powerful ability to assess the greenness of natural product extraction, and also has unified consistency and effectiveness. Moreover, the aim of optimizing methods is to make them greener, simpler, and more efficient, ideally leading to technological applications and cost reduction. However, existing tools do not currently incorporate standards such as extraction efficiency and industrial production prospects into its evaluation system. In contrast, the proposed GET tool addresses this gap in the development of green extraction methods for natural products. Of course, the combination of these metric tools developed for sample preparation can help identify weak links in the entire extraction process, facilitating the efficient transformation from old methods to new ones.

6.

Comparison between the results obtained applying the different metrics for MCAE (a); MAE (b); PEF (c).

Conclusions

Given the increasing demand and interest in green extraction, it is crucial to balance key parameters of the extraction process from a holistic perspective to achieve optimal workflows. However, despite more than a decade since the concept of GENP was proposed, tools for evaluating the extraction process remain an unmet challenge. Existing green assessment tools were primarily focused on the development of green analytical methods, and generic evaluation criteria may overlook the efforts made in optimizing the extraction process.

The GET proposed in this paper is the first tool specifically designed for the evaluation of green extraction processes in natural products. By integrating multiple principles of GSP and GENP, it encompasses 14 criteria across six aspects: samples, solvents and reagents, energy consumption, byproducts and waste, process risk assessment, and quality evaluation of extracts. This allows GET to be applied for comprehensive greenness assessment of any known or new extraction methods. The Excel program within the GET toolkit makes the evaluation process rapid and straightforward, with the output of colorful pictographs enabling visual comparison of greenness differences among different methods. This provides the simplest way to select the most environmentally friendly extraction method. Applying GET to five extraction methods for saponins from ginseng successfully identified differences in greenness among the methods and highlighted areas for improvement in the extraction processes. Moreover, compared to other current evaluation tools (AES/MoGAPI/AGREEprep/SPMS), GET demonstrates higher accuracy and specificity in assessing the greenness of the extraction processes.

However, the GET tool also has certain limitations. There are subjectivity issues in the practical application of its evaluation criteria. For example, when determining whether certain solvents or materials are sustainable or renewable resources, the boundaries are not clear enough. For complex natural product extraction systems, it is difficult to quantify some of the criteria. For instance, when assessing process risks, some potential risks that are difficult to quantify are likely to be overlooked. Moreover, the GET tool is mainly evaluated based on laboratory research data. When it comes to the transformation to industrial largescale production, due to the more complex actual production conditions, the accuracy and applicability of its evaluation results may be affected. Further research is needed to explore how to better adapt to industrial scenarios.

The extraction of natural products, while seemingly a straightforward chemical task, involves significant energy and material inputs for the separation, purification, and analysis of these bioactive compounds. To date, no perfect, green extraction technology has been discovered capable of handling the green separation of natural products effectively. The GET tool developed in this research aims to meticulously deconstruct the sample extraction preparation and analytical processes, and its introduction ensures that improvements in sample extraction are not overlooked by more generic tools, which is especially important for the development, improvement and evaluation of green extraction methods for natural products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82130115 and 82404861). The authors would like to thank Weixia Li, Mingliang Zhang, Chunling Zhang in First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Chinese Medicine and Linnan Li from Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine for their comments and support on the evaluation criteria. The authors would like to thank the reviewers and also the authors of all references.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c07167.

An open access toolkit allows researchers to achieve rapid qualitative comparison and analysis of the greenness of multiple extraction methods (XLS)

∥.

L.F. and W.F. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Anastas, P. T. ; Warner, J. C. . Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, 1998; pp 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gałuszka A., Migaszewski Z., Namieśnik J.. The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013;50:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2013.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Lorente Á. I., Pena-Pereira F., Pedersen-Bjergaard S., Zuin V. G., Ozkan S. A., Psillakis E.. The ten principles of green sample preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022;148:116530. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2022.116530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M. Y., Zheng X. Y., Zhang N., Guo Y. F., Liu M. C., Yin L.. Overview of sixteen green analytical chemistry metrics for evaluation of the greenness of analytical methods. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023;166:117211. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2023.117211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imam M. S., Abdelrahman M. M.. How environmentally friendly is the analytical process? A paradigm overview of ten greenness assessment metric approaches for analytical methods. Trends. Environ. Anal. 2023;38:00202. doi: 10.1016/j.teac.2023.e00202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gałuszka A., Konieczka P., Migaszewski Z. M., Namieśnik J.. Analytical Eco-Scale for assessing the greenness of analytical procedures. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012;37:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2012.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy C. R., Constantinou A., Jones L. C., Summerton L., Clark J. H.. Towards a holistic approach to metrics for the 21st century pharmaceutical industry. Green Chem. 2015;17:3111–3121. doi: 10.1039/C5GC00340G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Płotka-Wasylka J.. A new tool for the evaluation of the analytical procedure: green Analytical Procedure Index. Talanta. 2018;181:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour F. R., Płotka-Wasylka J., Locatelli M.. Modified GAPI (MoGAPI) Tool and Software for the Assessment of Method Greenness: Case Studies and Applications. Analytica. 2024;5:451–457. doi: 10.3390/analytica5030030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour F. R., Omer K. M., Płotka-Wasylka J.. A total scoring system and software for complex modified GAPI (ComplexMoGAPI) application in the assessment of method greenness. Green Anal. Chem. 2024;10:100126. doi: 10.1016/j.greeac.2024.100126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnowski W., Tobiszewski M., Pena-Pereira F., Psillakis E.. AGREEprep-Analytical greenness metric for sample preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022;149:116553. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2022.116553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González-Martín R., Gutiérrez-Serpa A., Pino V., Sajid M.. A tool to assess analytical sample preparation procedures: Sample preparation metric of sustainability. J. Chromatogr. A. 2023;1707:464291. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2023.464291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman R., Helmy R., Al-Sayah M., Welch C. J.. Analytical Method Volume Intensity (AMVI): a green chemistry metric for HPLC methodology in the pharmaceutical industry. Green Chem. 2011;13:934–939. doi: 10.1039/c0gc00524j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber Y., Törnvall U., Kumar M. A., Amin M. A., Hatti-Kaul R.. HPLC-EAT (Environmental Assessment Tool): a tool for profiling safety, health and environmental impacts of liquid chromatography methods. Green Chem. 2011;13:2021–2025. doi: 10.1039/c0gc00667j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks M. B., Farrell W., Aurigemma C., Lehmann L., Weisel L., Nadeau K., Lee H., Moraff C., Wong M. L., Huang Y., Ferguson P.. Making the move towards modernized greener separations: introduction of the analytical method greenness score (AMGS) calculator. Green Chem. 2019;21:1816–1826. doi: 10.1039/C8GC03875A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peris-Pastor G., Azorín C., Grau J., Benede J. L., Chisvert A.. Miniaturization as a smart strategy to achieve greener sample preparation approaches: A view through greenness assessment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024;170:117434. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2023.117434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roobab U., Aadil R. M., Kurup S. S., Maqsood S.. Comparative evaluation of ultrasound-assisted extraction with other green extraction methods for sustainable recycling and processing of date palm bioresources and by-products: A review of recent research. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025;114:107252. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2025.107252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemat F., Abert-Vian M., Fabiano-Tixier A. S., Strube L. J., Uhlenbrock, Gunjevic V., Cravotto G.. Green extraction of natural products. Origins, current status, and future challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;118:248–263. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemat F., Abert-Vian M., Cravotto G.. Green extraction of natural products: concept and principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:8615–8627. doi: 10.3390/ijms13078615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S. Sample Preparation Techniques in Analytical Chemistry; Wiley: NJ, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chemat F., Fabiano-Tixier A. S., Vian M. A., Allaf T., Vorobiev E.. Solvent-free extraction of food and natural products. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015;71:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2015.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Wu X., Cai C. W., Shao X. G.. Rapid determination of amino acids in ginseng by high performance liquid chromatography and chemometric resolution. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2014;30:578–581. doi: 10.1007/s40242-014-3543-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wen X., Wang C. Z., Li W., Huang W. H., Xia J., Ruan C. C., Yuan C. S.. Remarkable impact of amino acids on ginsenoside transformation from fresh ginseng to red ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2020;44:424–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang H. D., Yang F. F., Chen B. X., Li X., Huang Q. X., Li J., Li X. Y., Li Z., Yu H. S.. et al. Multi-level fingerprinting and cardiomyocyte protection evaluation for comparing polysaccharides from six Panax herbal medicines. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022;277:118867. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peake B. M., Tong A. Y. C., Wells W. J., Harraway J. A., Niven B. E., Weege B., LaFollette D. J.. Determination of trace metal concentrations in ginseng (Panax quinquefolius (American)) roots for forensic comparison using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass-Spectrometry. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015;251:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellumori M., Innocenti M., Binello A., Boffa L., Mulinacci N., Cravotto G.. Selective recovery of rosmarinic and carnosic acids from rosemary leaves under ultrasound-and microwave assisted extraction procedures. C. R. Chim. 2016;19:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2015.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, M. Sample Citrus Essential Oil: Flavor and Fragrance; Wiley: Weinheim, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aleman-Nava G. S., Gatti I. A., Parra-Saldivar R., Dallemand J. F., Rittmann B. E., Iqbal H. M. N.. Biotechnological revalorizatibn of Tequila waste and by-product streams for cleaner production - A review from bio-refinery perspective. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018;172:3713–3720. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Liu J., Zuo T. T., Hu Y., Li Z., Wang H. D., Xu X. Y., Yang W. Z., Guo D. A.. Advances and challenges in ginseng research from 2011 to 2020: the phytochemistry, quality control, metabolism, and biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022;39:875–909. doi: 10.1039/D1NP00071C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L. H., Fan W. X., Zhang Q., Liu L. C., Wang Z. Y., Mei Y. Q., Li L. N., Wang Z. T., Yang L.. Sustainable mechanochemical-assisted extraction of active saponins from plants with solid acid and alkalis. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023;11:17979–17989. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c05057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. T., You J. Y., Yu Y., Qu C. F., Zhang H. R., Ding L., Zhang H. Q., Li X. W.. Analysis of ginsenosides in Panax ginseng in high pressure microwave-assisted extraction. Food Chem. 2008;110:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J. H., Bélanger J. M. R., Paré J. R. J., Yaylayan V. A.. Application of the microwave-assisted process (MAP) to the fast extraction of ginseng saponins. Food Res. Int. 2003;36:491–498. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(02)00197-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J. B., Li S. P., Chen J. M., Wang Y. T.. Chemical characteristics of three medicinal plants of the Panax genus determined by HPLC-ELSD. J. Sep. Sci. 2007;30:825–832. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J. G., He S. Y., Ling M. S., Li W., Dong R., Pan Y. Q., Zheng Y. N.. A method of extracting ginsenosides from Panax ginseng by pulsed electric field. J. Sep. Sci. 2010;33:2707–2713. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour F. R., Nowak P. M.. Introducing the carbon footprint reduction index (CaFRI) as a software-supported tool for greener laboratories in chemical analysis. BMC Chem. 2025;19:121. doi: 10.1186/s13065-025-01486-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour F. R., Bedair A., Belal F., Magdy G., Locatelli M.. Analytical Green Star Area (AGSA) as a new tool to assess greenness of analytical methods. Sustainable Chem. Pharm. 2025;46:102051. doi: 10.1016/j.scp.2025.102051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam P., Shakeel F., Alshehri S., Igbal M., Foudah A. I., Alqarni M. H., Aljarba T. M., Alhaiti A., Bar F. A.. Comparing the greenness and validation metrics of traditional and Eco-friendly stability-indicating HPTLC methods for Ertugliflozin determination. ACS Omega. 2024;9:23001–23012. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c02399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.