Abstract

Casein kinase I (CKI) was recently reported as a positive regulator of Wnt signaling in vertebrates and Caenorhabditis elegans. To elucidate the function of Drosophila CKI in the wingless (Wg) pathway, we have disrupted its function by double-stranded RNA-mediated interference (RNAi). While previous findings were mainly based on CKI overexpression, this is the first convincing loss-of-function analysis of CKI. Surprisingly, CKIα- or CKIε-RNAi markedly elevated the Armadillo (Arm) protein levels in Drosophila Schneider S2R+ cells, without affecting its mRNA levels. Pulse–chase analysis showed that CKI-RNAi stabilizes Arm protein. Moreover, Drosophila embryos injected with CKIα double-stranded RNA showed a naked cuticle phenotype, which is associated with activation of Wg signaling. These results indicate that CKI functions as a negative regulator of Wg/Arm signaling. Overexpression of CKIα induced hyper-phosphorylation of both Arm and Dishevelled in S2R+ cells and, conversely, CKIα-RNAi reduced the amount of hyper-modified forms. His-tagged Arm was phosphorylated by CKIα in vitro on a set of serine and threonine residues that are also phosphorylated by Zeste-white 3. Thus, we propose that CKI phosphorylates Arm and stimulates its degradation.

Keywords: Armadillo/casein kinase I/proteasome/RNAi/Wnt

Introduction

Wnt signaling is essential for many aspects of development in invertebrates and vertebrates (reviewed in Cadigan and Nusse, 1997; Dale, 1998) and mutations in components of the Wnt pathway are oncogenic (reviewed in Polakis, 2000). A variety of studies in divergent organisms have set a general framework for the Wnt [Wingless (Wg) in Drosophila] pathway as well as revealing that players in this pathway are structurally and functionally conserved in various species. In this pathway, the stabilization of β-catenin/Armadillo (Drosophila homolog of β-catenin, Arm) protein is a key regulatory step. The Wnt/Wg ligand binds to the receptor, Frizzled, which activates an intracellular multi-modular protein, Dvl/Dishevelled (Dsh). Several Wnt/Wg pathway components, including Dvl/Dsh, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β)/Zeste-white 3 (ZW3), β-catenin/Arm, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein/Dapc and protein phosphatase 2A, have been shown to form a large multimeric protein complex on the scaffold protein Axin/Daxin (reviewed in Kikuchi, 1999). In the absence of Wnt/Wg signaling, GSK-3β/ZW3 phosphorylates β-catenin/Arm (Yost et al., 1996; Pai et al., 1997), targeting it to the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway for degradation (Aberle et al., 1997). Wnt/Wg inhibits GSK-3β/ZW3 function through the Dsh family proteins, thereby up-regulating β-catenin/Arm protein levels, β-catenin/Arm then forms a complex with the Tcf-Lef/D-Tcf family of transcription factors and activates transcription of Wnt/Wg target genes (reviewed in Hecht and Kemler, 2000).

Recently one isoform of the casein kinase I (CKI) family, CKIε, was identified as a positive regulator of the canonical Wnt pathway. Overexpression of CKIε in Xenopus embryos induced second axes, activated the transcription of target genes and rescued UV-treated embryos (Peters et al., 1999; Sakanaka et al., 1999). From epistasis analysis, CKIε appears to act between Dvl/Xenopus-dsh (Xdsh) and GSK-3β (Peters et al., 1999). Moreover, associations of CKIε, Axin and Dvl/Xdsh were also demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation experiments (Sakanaka et al., 1999). The kinase domain of CKIε was shown to directly bind to the PDZ (PSD95, discs large, Z0-1) domain of Xdsh (Peters et al., 1999; Mckay et al., 2001b). With the yeast two-hybrid assay, CKIε was shown to directly bind to the C-terminal portion of Axin (Mckay et al., 2001b; Rubinfeld et al., 2001). However, direct binding of CKIε to the DEP (Dsh, EGL-10, Pleckstrin) domain of Dvl and the association of CKIε with Axin via another unknown protein were reported (Kishida et al., 2001). On the other hand, direct phosphorylation of Dvl/Xdsh by several CKI isoforms and their involvement in Wnt-induced phosphorylation of Dvl have been shown (Mckay et al., 2001b). In line with these findings, a synergistic interaction of Dvl and CKIε in the activation of Wnt signaling has been reported (Kishida et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2001). However, in spite of intensive study, the mode of CKI action in Wnt signaling remains unclear.

Two recent papers suggest a more complicated mechanism. CKIε was shown to mediate, at least in part, Axin-dependent phosphorylation of APC, which stimulates APC to downregulate β-catenin (Rubinfeld et al., 2001). Moreover, Lee et al. (2001) have shown in Xenopus systems that a cytoplasmic fraction of Tcf3 competes with the Axin–APC–GSK-3β complex for β-catenin and thereby inhibits β-catenin degradation. CKIε phosphorylates Tcf3 and thus strengthens Tcf3–β-catenin interaction, which leads to β-catenin stabilization. In addition, CKIε stimulates the binding of Xdsh to GSK-3β binding protein (GBP) (Lee et al., 2001). These results suggest that CKIε regulates Wnt signaling in vivo by modulating the β-catenin–Tcf3 and the GBP–Xdsh interactions. However, it is not clear whether this new model is applicable to other organisms, such as Drosophila, which has no apparent GBP counterpart. On the other hand, several CKI isoforms have also been shown to act in the non-canonical Wnt pathway. Blocking CKI function inhibits embryonic morphogenesis and activates JNK (Mckay et al., 2001a).

Several CKI isoforms are present in both vertebrates and Drosophila, and these CKI family enzymes contain isoform-specific amino and carboxyl extensions plus highly conserved kinase domains. Recently, Mckay et al. (2001b) have reported that the CKI isoforms, α, β, γ and δ, could also activate the Wnt pathway in Xenopus embryos. The CKI family also functions in a variety of cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair and circadian rhythms (Santos et al., 1996; Price et al., 1998). However, the mechanisms conferring the different functions on the variety of isoforms are unknown.

In Drosophila, Zilian et al. (1999) found that the discs overgrown (dco) gene, which strongly affects cell survival and growth control in imaginal discs, encodes a homolog of mammalian CKIε and is identical to the previously cloned double-time (dbt) gene, which regulates the period of the circadian rhythms. The fact that alterations in Wnt signaling leading to elevations in β-catenin promote tumorigenesis in mammals, and the finding that CKIε modulates β-catenin protein expression in vertebrates, appear to be related to the observation that certain dco mutants show hyperplastic growth of imaginal discs. On the other hand, in Drosophila circadian clock regulation, the CKIε, Double-time protein, directly binds and phosphorylates the Period protein, thereby promoting its turn over (Price et al., 1998). Surprisingly, a recent study has indicated that both shaggy/zw3 and double-time participate in circadian clock control (Martinek et al., 2001) suggesting an underlying synergism between ZW3–GSK-3β and Double-time–CKIε. However, no dbt or dco mutant has been reported that shows a phenotype closely associated with the loss or gain of wg function. The reason for this is not clear. However, it is possible that the expression level of the CKIε isoform (dbt or dco) is relatively low, compared with that of other CKI isoforms, and thus loss of CKIε activity was masked by the activities of the other CKI isoforms. Furthermore, no Drosophila mutants for other CKI isoforms have been isolated. Therefore the roles of CKI in Wg signaling have not been explored extensively in Drosophila.

Here, we describe the use of a double-stranded RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) approach to study the function of Drosophila CKI in the Wg signaling pathway. Our results suggest that CKI functions as a negative regulator of Arm protein, by phosphorylating it on Ser and Thr residues in the N-terminus and targeting it for degradation.

Results

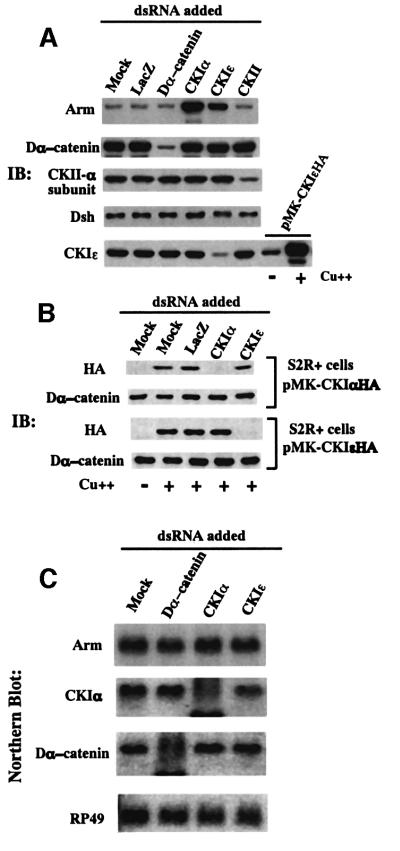

CKI-RNAi leads to accumulation of Arm protein in Drosophila Schneider S2R+ cells

Since loss-of-function studies are the key to revealing the actual function of Drosophila CKI in the Wg pathway, we used RNAi to disrupt the CKI gene expression in Drosophila Schneider S2R+ cells (Clemens et al., 2000). S2R+ cells were cultured in the presence of double-stranded (ds)RNA for CKIα, CKIε, Dα-catenin, casein kinase II catalytic (α) subunit (CKII-α) or LacZ for 3 days and then the protein levels in the cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting (Figure 1A). Addition of dsRNA for CKIε, Dα-catenin and CKII-α caused a selective decrease in the corresponding proteins. While previous studies with Xenopus, Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian systems reported that CKI is a positive regulator of Wnt signaling, both CKIα- and CKIε-RNAi markedly elevated Arm protein levels, suggesting that CKI functions as a negative regulator of Arm protein in Drosophila. CKIα-RNAi induced higher levels of Arm protein accumulation than CKIε-RNAi.

Fig. 1. RNAi-mediated disruption of Drosophila CKI gene expression leads to accumulation of Arm protein in Schneider S2R+ cells. (A) Western blot analysis of the lysates of cells incubated with dsRNA. In the bottom blot, lysates from the pMK-CKIε-HA transfectant induced with (+) or without (–) CuSO4 were used to demonstrate that the antibody against human CKIε recognizes Drosophila CKIε. (B) Specificity of CKIα- and CKIε-RNAi. The CKIα-HA or CKIε-HA transfectants were incubated with dsRNA for 60 h, and induced with CuSO4 for a further 12 h, before being subjected to western blotting. (C) Northern blot analysis showing specific degradation of the target mRNA by individual dsRNA.

We next clarified whether CKIα- and CKIε-RNAi were selective for each CKI isoform (Figure 1B). S2R+ cells expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged CKIα or CKIε were established and they were treated with CKIα- or CKIε-dsRNA. CKIα- and CKIε-dsRNA induced the selective disappearance of the corresponding protein isoform, indicating that isoform-RNAi is specific. This is consistent with the result of CKIε protein blotting (Figure 1A). These results indicate that depletion of either CKIα or CKIε protein alone can induce the Arm protein elevation, suggesting that CKI family proteins in general function in down-regulating Arm protein. Double-RNAi for both CKIα and CKIε isoforms led to a significantly higher level of Arm than that induced by CKIα- or CKIε-RNAi alone (data not shown). It should be noted that CKIα- and CKIε-RNAi did not affect the protein levels of Dsh (Figure 1A) or ZW3 (see Figure 5), indicating that the CKI-RNAi-mediated Arm elevation is not caused by modulating the protein levels of Wg signaling components upstream of Arm. Northern analysis revealed that CKIα- and Dα-catenin-dsRNA caused a selective reduction of the corresponding mRNA but did not affect Arm mRNA levels (Figure 1C). As CKIα-RNAi induced a more prominent Arm accumulation than CKIε-RNAi, CKIα was mainly used for later analyses.

Fig. 5. Epistatic analysis showing dsh and zw3 have little effect on CKIα-RNAi-mediated Arm elevation. To cultures of S2R+ cells, 7.5 µg of LacZ-, Dsh-, ZW3- or CKIα-dsRNA were added in combinations, so that the total amount of dsRNA per culture was equal to 15 µg. After a 3 day incubation, cellular extracts were subjected to western blot analysis.

CKIα-RNAi stabilizes Arm protein but does not affect the rate of Arm protein synthesis

The CKIα-RNAi-mediated Arm elevation could be caused by two mechanisms: CKIα-RNAi increased the rate of Arm protein synthesis or decreased the rate of Arm degradation. To distinguish between these possibilities we used pulse–chase analysis. In pulse (7 min)-labeled cells, similar amounts of Arm protein were made, irrespective of whether the cells were treated with CKIα- or LacZ-dsRNA (Figure 2A). Pulse–chase analysis over 200 min indicated that the Arm protein in cells treated with CKIα-dsRNA appeared to be stable, whereas in cells treated with LacZ-dsRNA, it decayed rapidly (Figure 2B and C). Hence, the Arm protein accumulation due to CKIα-RNAi appears to be largely a consequence of increased stability.

Fig. 2. CKIα-RNAi stabilizes Arm protein but does not affect the rate of Arm protein synthesis. (A) Fluorogram showing incorporation of radioactivity into total cellular proteins or immunoprecipitated Arm. (B) Pulse–chase analysis of Arm protein in S2R+ cells treated with LacZ- or CKIα-dsRNA. Fluorograms of anti-Arm immunoprecipitates sampled at the indicated chase time are shown. (C) Kinetics of Arm turnover in S2R+ cells incubated with LacZ- (open squares) or CKIα-dsRNA (filled squares). Pulse–chase data for labeled Arm were quantified by a BAS-2000, with time = 0 set as 100%.

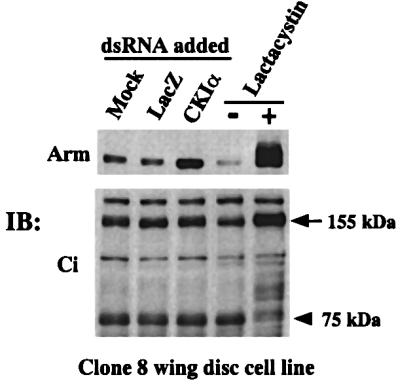

CKIα-RNAi stabilizes Arm protein but not the 155 kDa Cubitus interruptus protein in clone-8 wing imaginal disc cells

Arm normally undergoes phosphorylation by ZW3, associates with the F-box protein, Slimb, and is degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Jiang and Struhl, 1998). To investigate whether CKIα-RNAi selectively stabilizes Arm protein, we compared the effects of CKIα-RNAi on protein levels of Arm and the transcriptional regulatory protein Cubitus interruptus (Ci), a component of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. In the absence of Hedgehog signaling, the 155 kDa Ci protein is proteolytically processed by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway to produce a 75 kDa N-terminal protein (Aza-Blanc et al., 1997). For this analysis, the clone-8 cell line, in which Arm and Ci protein levels are regulated by Wg and Hedgehog signaling, respectively, was used. In clone-8 cells, CKIα-RNAi again stabilized Arm, but did not block processing of the 155 kDa Ci into 75 kDa Ci. However, treatment of this cell line with lactacystin, a specific inhibitor of the proteasome, led to stabilization of both Arm and the 155 kDa Ci proteins (Figure 3). These findings suggest that CKIα-RNAi selectively protects Arm from degradation.

Fig. 3. CKIα-RNAi stabilizes Arm but not the 155 kDa Cubitus interruptus (Ci) in clone-8 cells. Lysates from cells incubated with dsRNA were subjected to western blot analysis with anti-Arm antibodies or an antibody against the N-terminal portion of Ci. Cells incubated with or without 20 µM of lactacystin for 6 h were used to demonstrate that both Arm and the 155 kDa Ci are processed by proteasomes. An arrow and an arrowhead indicate the full-length Ci (155 kDa) and the proteolytically processed 75 kDa form, respectively.

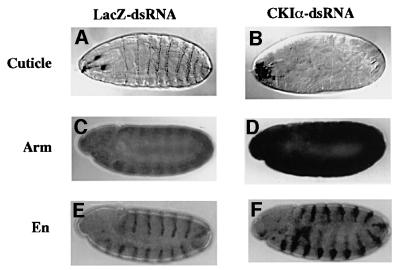

Disruption of CKIα function by RNAi produces a naked cuticle

The ventral epidermis of a wild-type Drosophila embryo is covered by a cuticle with a repeated pattern of denticle belts followed by the naked cuticle (like the embryo shown in Figure 4A). Wg signaling is required to elevate Arm protein levels and to specify the fate of the epidermal cells that secrete the smooth cuticle. Thus, a loss of Wg leads to a cuticle covered with denticles and lacking naked areas, while ubiquitous Wg causes a naked cuticle, without denticle structures (Noordermeer et al., 1992). Furthermore, Drosophila mutants for zw3 (Siegfried et al., 1992) or daxin (Hamada et al., 1999), as well as wild-type embryos injected with Daxin-dsRNA (Willert at al., 1999), all of which exhibit ubiquitous elevation of Arm protein, show the naked cuticle phenotype. Hence, RNAi-in vivo was performed to generate a ckIα-loss-of-function phenotype. Among 640 embryos injected with lacZ-dsRNA, only 45% survived to develop into larvae, because of damage from RNA injections. All of these larvae showed a cuticle phenotype indistinguishable from that of uninjected wild-type embryos (Figure 4A) and no larva with a naked cuticle was found. Among 820 embryos injected with CKIα-dsRNA, on the other hand, 38% survived to become larvae. Forty-five and 43% of these larvae showed completely and partially naked cuticle phenotypes, respectively, while the other 12% showed the cuticle phenotype of uninjected wild-type embryos (Figure 4B). Thus, we concluded that injection of CKIα-dsRNA led to a naked cuticle. To ascertain that CKIα-RNAi indeed elevates Arm protein levels and leads to Wg target gene (engrailed) activation in vivo, LacZ- or CKIα-dsRNA-injected embryos developed to stage 10 were stained with anti-Arm and anti-Engrailed antibodies. The high levels of Arm protein only found in the Wg domain in LacZ-RNAi embryos (Figure 4C), have extended to the whole segment in CKIα-RNAi embryos (Figure 4D). Moreover, as in heat-shock-Wg embryos which uniformly express Wg (Noordermeer et al., 1992), Engrailed expression domain in CKIα-RNAi embryos has broadened, indicating that the Wg target gene was activated (Figure 4F). These in vivo data indicated that the loss of CKIα function leads to a phenotype associated with Wg pathway activation, which is consistent with the idea that CKIα is a negative regulator of Wg signaling.

Fig. 4. Disruption of CKIα function by RNAi induces a naked cuticle, Arm protein elevation and expansion of the Engrailed expression domain. Cuticle preparation (A and B), immunostaining patterns of Arm (C and D) and Engrailed (E and F) in the embryos injected with LacZ- (A, C and E) or CKIα-dsRNA (B, D and F).

dsh and zw3 slightly influence the CKIα-RNAi-induced elevation in Arm

We used epistasis analysis to explore where CKI functions in the Wg pathway. In this analysis, the effects of Dsh- or ZW3-dsRNAs on CKIα-RNAi-mediated Arm elevation were analyzed (Figure 5). Consistent with the accepted notion of dsh and zw3 functions, Dsh- and ZW3-RNAi resulted in a slight decrease and increase in Arm protein levels, respectively. Compared with CKIα-RNAi, ZW3-RNAi induced the accumulation of much lower levels of Arm. As western blotting revealed that ZW3-RNAi led to a significant reduction in protein levels, this result was rather surprising, but the reason for it is unknown. Notably, both Dsh- and ZW3-RNAi had little effect on the CKIα-RNAi-induced Arm elevation, suggesting that dsh and zw3 play a minor role (Figure 5). Assuming that dsh and ckIα function in a linear pathway, these results suggest ckIα is downstream of dsh.

Overexpression of CKIα leads to hyper-phosphorylation of Arm and Dsh proteins

The RNAi-based loss-of-function analyses of CKIα described so far are all consistent with the notion that CKIα negatively regulates Arm protein levels. As a complementary approach, we examined the effect of overexpressing the wild-type or kinase-negative form of CKIα, as well as wild-type ZW3, on protein levels and biochemical properties of Arm, Dsh and ZW3 proteins. S2R+ cells transfected with pMK33 vector were used as the control. As Arm is rapidly turned over, analyses were performed in the presence and absence of lactacystin (Figure 6A).

Fig. 6. CKIα phosphorylates Arm in vivo and in vitro. (A) Overexpression of CKIα leads to the hyper-phosphorylation of Arm and Dsh protein. S2R+ transfectants that overexpressed the wild-type or kinase-negative form of HA-tagged CKIα or HA-tagged wild-type ZW3 were cultured in the presence or absence of CuSO4 for 14 h. Then the cells were incubated for a further 6 h in the presence or absence of lactacystin (20 µM). Cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis. Hyper-phosphorylated forms of Arm and Dsh are indicated by an open arrow and a closed arrow, respectively. The arrowhead indicates a marked increase in the phosphorylated forms of Arm upon CKIα induction, and this was detected only in the presence of lactacystin. (B) CKIα-RNAi decreased the amount of highly modified forms of Arm. The S2R+ cell cultures preincubated with LacZ- or CKIα-dsRNA for 30 h, were further incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of 20 µM lactacystin. Western blot of the cell lysates are shown. (C) In vitro kinase assay for CKIα. HA-tagged CKIα immunoprecipitated from cells treated with or without Wg was incubated with His-tagged Arm or a CKI substrate peptide. The upper panel is the autoradiogram showing the kinetcs of Arm phosphorylation. The lower panel shows the kinetics of the substrate peptide phosphorylation with the immunoprecipitates from Wg-treated (filled squares) and non-treated (open squares) cells.

In the absence of lactacystin, overexpression of the wild-type CKIα or kinase-negative form had little effect on the total Arm protein levels. Similar experiments with CKIε gave the same results (data not shown). In addition, overexpression of wild-type CKIα or CKIε could not block the Wg-induced Arm accumulation (data not shown). Drosophila CKI functions as a negative regulator of Arm (Figures 1A and 2) and the kinase-dead form of CKI was shown to be dominant-negative in Xenopus (Peters et al., 1999). Therefore, these results were contrary to our expectations that overexpression of wild-type CKI or the kinase-negative CKI would lead to a decrease or increase of Arm protein levels, respectively. The reason for this is not clear, but it is possible that the endogenous CKI activity is already sufficiently high to exert the maximum rate of Arm degradation in normal S2R+ cells. However, this failed to explain why the overexpressed kinase-negative forms of CKIα do not appear to compete effectively with endogenous CKI activity.

Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 6A, overexpression of wild-type CKIα induced the accumulation of low levels of hyper-phosphorylated (showing less electrophoretic mobility) forms of Arm (open arrow) and Dsh (closed arrow), but that of the kinase-negative form of CKIα or wild-type ZW3 did not. These mobility shifts were eliminated by treating the immunoprecipitates with phosphatase prior to electrophoresis, indicating that they were mainly due to phosphorylation (data not shown). On the other hand, overexpression of wild-type CKIα or the kinase-negative form did not affect ZW3 protein levels or shifted it on SDS–PAGE (Figure 6A). These results, together with CKIα-RNAi data (Figure 5), indicated that modulation of CKIα protein levels has little effect on ZW3 protein in S2R+ cells.

In the presence of lactacystin, several Arm species with lower electrophoretic mobility (representing various phosphorylated and poly-ubiquitylated forms) were detected in all samples. Notably, lactacystin accentuated the increase in phosphorylated forms of Arm (Figure 6A, showing unique electrophoretic mobility different from other phosphorylated and poly-ubiquitylated forms, indicated with an arrowhead), which was induced by expression of wild-type CKIα but not the kinase-negative form. In addition, overexpression of wild-type ZW3 led to slight increases in highly modified forms of Arm. The Arm species induced by CKIα- and ZW3-overexpression in the presence of lactacystin showed distinct mobility profiles on SDS–PAGE, suggesting that this CKIα-induced modification of Arm was due to its own kinase activity and not mediated by that of ZW3 (Figure 6A).

To demonstrate that endogenous CKIα, at least in part, participates in phosphorylation of Arm and thus induces its subsequent modification in intact S2R+ cells, we analyzed whether CKIα-RNAi decreased the amount of modified forms of Arm in the presence of lactacystin (Figure 6B). CKIα-RNAi again led to a marked Arm elevation in the absence of lactacystin. While western blots from lactacystin-treated cells showed that various modified forms of Arm were detected in the LacZ-RNAi cells as in pMK33 transfectants (Figure 6A). In the CKIα-RNAi cells, however, the amount of these modified forms was decreased, although some clearly remained. At the same time, the level of non-modified Arm (showing the highest mobility) was elevated. These results suggest that, in normal circumstances, a significant fraction of Arm is modified under the control of CKIα, further supporting the idea that CKIα downregulates Arm protein levels by phosphorylation.

Arm is phosphorylated in vitro by CKIα but its kinase activity is not affected by Wg signaling

To demonstrate that Arm is a substrate for CKIα and to examine the effect of Wg signaling on CKIα kinase activity, in vitro kinase assays were performed. HA-tagged CKIα was immunoprecipitated from S2R+ transfectants treated with or without Wg (Figure 6C). Western blots from these cell lysates revealed that the same amounts of HA-tagged CKIα were immunoprecipitated. Incubation of the immunoprecipitates with His-tagged Arm or a CKI peptide substrate in the presence of γ-32P-labeled ATP indicated that Arm is a good substrate for CKIα and that Wg signaling has little effect on its kinase activity. However, it is possible that in vivo Wg signaling regulates CKIα-mediated Arm phosphorylation by modulating a physical interaction between CKIα and Arm. Therefore, it is not clear in vivo whether Wg signaling affects CKI-mediated phosphorylation of its substrates, including Arm and Dsh.

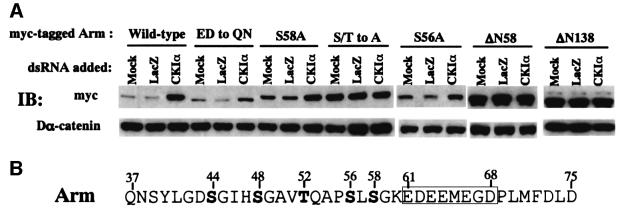

Identification of the sequence in Arm protein which is responsible for CKIα-RNAi-mediated Arm accumulation

To search for the sequence in Arm that responds to CKIα-RNAi, stable S2R+ cell lines expressing wild-type and various mutant forms of myc-tagged Arm were established and the effects of CKIα-RNAi (LacZ-RNAi was used as the control) on accumulation of these Arm mutant proteins were examined by western blotting (Figure 7A). Similar to endogenous Arm, wild-type Arm with the myc-tag was markedly stabilized by CKIα-RNAi. As phosphorylation of Arm at the N-terminus is known to determine its stability, we first analyzed Arm mutants lacking the N-terminal 58 or 138 amino acids. These two mutants, which are more stable than the wild-type, no longer responded to CKIα-RNAi, indicating that the target sequence for CKIα-RNAi resides in the N-terminal 58 amino acids. Therefore, we made a series of N-terminal mutants (Figure 7B). In the S/T to A mutant, the Ser and Thr residues originally identified as phosphorylation target sites for ZW3 (S at codon 44, 48, 56 and T at 52) were changed to Ala. In S56A and S58A, the Ser at 56 and 58, respectively, was changed to Ala. In the ED to QN mutant, a stretch of acidic amino acids (E and D) was replaced with Q and N (E at 61, 63, 64, 66 to Q and D at 62 to N). This mutant was produced because CKI is known to phosphorylate a Ser or Thr residue close to the acidic residues and this stretch of acidic amino acids is also conserved in β-catenin and plakoglobin.

Fig. 7. CKIα target sequence in Arm protein. (A) Stable S2R+ transfectants expressing various myc-tagged Arm proteins were incubated with 15 µg of LacZ- or CKIα-dsRNA for 60 h, and then incubated for a further 12 h in the presence of CuSO4. The cell lysates were then subjected to western blot analysis with antibody against the myc-epitope or Dα-catenin. The pMK-Arm-myc constructs used to establish cell lines are shown above the panels. (B) Amino acid sequence of Arm from codon 37 to 75 is shown. Ser and Thr residues mutated in some constructs are shown in bold. The box indicates a stretch of acidic amino acids.

Analyses with this series of Arm mutants revealed that protein levels of the S58A mutant were somewhat elevated even without CKI-RNAi, but this mutant responded to CKI-RNAi similarly to the wild-type Arm, while, the S56A mutant responded slightly less than the wild-type Arm. The S/T to A mutant no longer responded to CKIα-RNAi, while the ED to QN mutant responded much weaker than the wild-type Arm. These results suggest that CKIα directly or indirectly stimulates phosphorylation of Ser44, 48 and 56, as well as Thr52, thereby destabilizing Arm and that the stretch of acidic amino acids may facilitate this process. If so, we would expect the ED to QN mutant to be more stable than the wild-type Arm. Hence, the stabilities of the wild-type, S/T to A, S56A and ED to QN forms of Arm were compared (Figure 8). To confirm that the steady-state levels of each Arm protein reflected the stability of each protein, the transfection efficiency and Arm mRNA levels were monitored in transient and stable expression experiments, respectively. Both experiments demonstrated that the S/T to A mutant was the most stable with the S56A mutant second. The ED to QN mutant was more stable than the wild-type Arm, but less stable than the S/T to A mutant.

Fig. 8. The Arm ED to QN mutant protein is stable, compared with the wild-type. (A) Transient expression experiment: 0.2 µg of pAcLacZ, together with 0.2 µg of pMK33 vector or various pMK-Arm-myc constructs were introduced into S2R+ cells, and after 36 h CuSO4 was added for 12 h. Expression levels of myc-tagged Arm were analyzed by western blotting. Note relative β-galactosidase activities in the cell lysates were almost the same. (B) Stable expression experiments. Stably transfected cells (5 × 106) were plated and expression of various myc-tagged Arm was induced with CuSO4. Expression levels of myc-tagged Arm and Dα-catenin were analyzed (upper two panels). Total RNAs from these cells were subjected to northern blot analysis with Arm or RP49 probe (lower two panels).

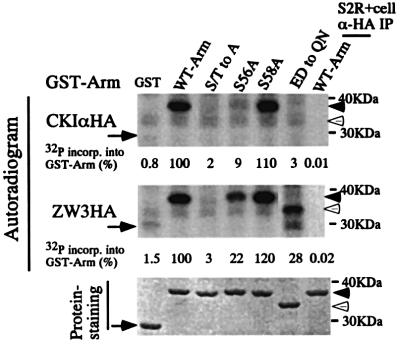

CKIα phosphorylates the same Ser and Thr residues in the N-terminal portion of Arm as ZW3

Next, we examined whether CKIα directly phosphorylates a set of Ser and Thr residues in the N-terminal region of Arm as ZW3 does. To this end, we generated a series of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Arm fusion proteins in which the N-terminal 39 amino acids (from codon 37 to 75) from the wild-type or mutant forms of Arm described above were fused to GST (our initial attempt using the whole Arm failed). CKIα-HA or ZW3-HA immunoprecipitated were used as enzyme preparations. 32P incorporation into these GST–Arm fusion proteins was analyzed by autoradiography (Figure 9). While naive GST was not phosphorylated by either CKIα or ZW3, the GST proteins containing the sequence from the wild-type Arm or S58A mutant were phosphorylated by CKIα to the same levels, indicating that S58 may not be phosphorylated. Fusion proteins with the S56A or the S48A and T52A double (data not shown) mutation were phosphorylated by CKIα at levels of 9 and 15%, respectively, of the fusion protein containing the wild-type Arm sequence. However, fusion proteins with the S/T to A or the ED to QN mutation were not phosphorylated by CKIα. These results indicate that the phosphorylation sites for CKIα are Ser44, 48 and 56, as well as Thr52 residues (among these, S56 seems to be the major phosphorylation site, whose phosphorylation affects those of the other three sites). A cluster of acidic amino acids is also required for this phosphorylation.

Fig. 9. In vitro kinase experiment to determine the major phosphorylation site for CKIα and ZW3 in the N-terminal region of Arm. Various GST–Arm fusion proteins were phosphorylated by CKIα-HA (upper panel) and ZW3-HA (middle panel). HA-immunoprecipitate from naive S2R+ cells was used as a negative control (the right lane in each panel). The same amount (10 µg) of GST or GST–Arm fusion proteins were used for each reaction (50 µl) and reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 10 min, before 10 µl of each was subjected to SDS–PAGE. The bottom panel shows the staining profiles of GST–Arm fusion proteins in the dried gel, from which the autoradiogram shown in the top panel was generated. The arrows and the arrowheads indicate the migration positions of plain GST and GST–Arm fusion proteins, respectively. The open arrow heads show the migration positions of a GST–Arm protein with the ED to QN mutation, which has a higher electrophoretic mobility. The amount of 32P incorporated into each GST–Arm fusion protein was expressed as a percentage of the amount incorporated into the protein containing the wild-type Arm sequence.

On the other hand, ZW3 phosphorylated the fusion proteins containing the wild-type sequence and the S58A mutation to the same levels, but not that containing the S/T to A mutation. The fusion protein with the S56A or the ED to QN mutation was phosphorylated by ZW3 at levels of 22 and 28%, respectively, of the fusion protein containing the wild-type Arm sequence, indicating that ZW3 did not necessarily require the cluster of acidic amino acids. As far as this in vitro experiment is concerned, prior phosphorylation of Arm from other kinases (known as priming kinases) does not appear to be essential for ZW3-mediated phosphorylation of these Ser and Thr residues. These results confirmed that CKIα can phosphorylate the same series of Ser and Thr residues in the N-terminal region of Arm as ZW3 does, which is consistent with the observation that the Arm S/T to A mutant no longer responds to CKIα-RNAi.

Discussion

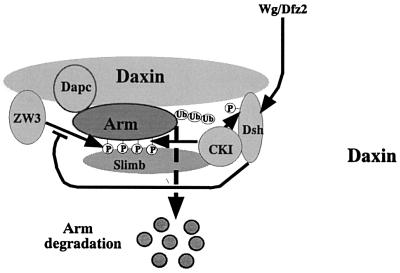

In this study, we have demonstrated that CKIα- and CKIε-RNAi elevated Arm protein levels in S2R+ cells by protecting Arm from degradation. In line with this, Drosophila embryos injected with CKIα-dsRNA showed a naked cuticle phenotype. In S2R+ cells, overexpression of wild-type-CKIα induced hyper-phosphorylation of Arm, while CKIα-RNAi inhibited these hyper-modifications. Moreover, the target sequence of CKIα-RNAi in Arm was found to be a series of Ser and Thr residues in its N-terminus, which was phosphorylated by CKIα in vitro. Thus, we propose that CKI phosphorylates Arm, which targets it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation in Drosophila. In vertebrates, CKIε, GSK-3β, Dvl, APC and Axin are known to form a complex (Sakanaka et al., 1999; Kishida et al., 2001; Rubinfeld et al., 2001). This suggests that CKI, ZW3, Dsh, Dapc and Arm could form a complex on Daxin in Drosophila. In addition, taking into account our finding that CKI binds to Slimb (unpublished result), we present a model of how CKI functions in the Wg pathway (Figure 10).

Fig. 10. Model depicting CKI function in the down-regulation of Arm protein. In this figure, CKI and ZW3 are shown to play redundant roles in the phosphorylation of Arm, which causes its ubiquitylation and rapid degradation. It is also possible that CKI phosphorylates Arm in the ubiquitylation machinery and thus strengthens Arm–Slimb interaction, which ensures Arm ubiquitylation. ZW3-mediated Arm phosphorylation is suppressed by Wg signaling via Dsh. The effect of Wg signaling on CKI-induced phosphorylation of Arm in vivo remains elusive. Direct association of CKI with Dsh is indicated in this figure, because overexpression of CKIα induced hyper-phosphorylation of Dsh (the function of this phosphorylation remains unclear, Figure 6A) and direct binding of these two proteins has been shown in vertebrates.

CKIε was proposed as a positive regulator of Wnt signaling in vertebrates, mainly based on the observation that overexpression of CKIε induced dorsal axis duplication in Xenopus and stimulated Tcf/lef reporter in mammalian cells. However, it should be noted that one component of a multimeric protein complex, when overexpressed, sometimes acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor (e.g. APC; Vleminckx et al., 1997). To avoid possible artifacts of overexpression studies, we performed a loss-of-function study using the highly effective method of RNAi in Drosophila.

We have shown previously that Wg/Wnt treatment rapidly induces hyper-phosphorylation of Dsh/Dvl in both Drosophila and mammalian cells (Lee et al., 1999). Here, we showed that CKIα overexpression led to hyper-phosphorylation of Dsh. Mckay et al. (2001b) have reported that Wnt-3a-induced Dvl phosphorylation was due to CKI, whereas PAR-1, a Dsh/Dvl-associated kinase, has been shown to phosphorylate Dsh/Dvl in response to Wg/Wnt (Sun et al., 2001). To resolve this issue, it is informative to see whether the Wg-induced phosphorylation of Dsh is affected by CKI- or PAR-1-RNAi.

A group of GSK-3β substrates are formed by prior phosphorylation from other kinases, an event known as ‘priming’, to generate the sequence S/T-X-X-X-S/T-PO4, where S/T corresponds to Ser or Thr and X to any other residues. In the case of glycogen synthase, CKII was assumed to be a priming kinase (Picton et al., 1982). In contrast, β-catenin is not known to require a priming phosphate and may rely on high affinity interactions in a multiprotein complex with GSK-3β. Recently, two groups have reported the existence of a phosphate-binding site in GSK-3β and showed that primed substrates require this site but non-primed ones do not (Dajani et al., 2001; Frame et al., 2001). However, we found that the GSK-3β target sequence in glycogen synthase (amino acid sequence from 640 to 661: SVPPSPSLSRHSSPHQSEDEEE) and the ZW3 target sequence in Arm (amino acid sequence from 44 to 68: SGIHSGAVTQAPSLSGKEDEEMEGD) share a combination of S/T-X-X-X-S/T repeats and a cluster of acidic amino acids. CKI was shown to phosphorylate a Ser or Thr residue C-terminal to a stretch of acidic residues (Flotow et al., 1991), but it also phosphorylates sites not matching this consensus. Actually, Ser56 of Arm, which is located to the N-terminus of the acidic residues cluster, is a major phosphorylation site for CKIα (Figure 9), and it corresponds to the residue with a priming phosphate in glycogen synthase (Ser656). In addition, CKI, ZW3 and Arm appear to form a complex. Thus, it is possible that CKI partly works as a priming kinase that phosphorylates any of the residues Ser56, Ser48 or Thr52 of Arm and thereby stimulates ZW3-mediated phosphorylation of Ser48, Ser44 or Thr52.

The cluster of acidic amino acids described above is conserved in β-catenin (amino acid sequence from 53 to 58: EEEDVD). Notably, mutations in this region have been reported in tumors. Of 37 independent anaplastic thyroid carcinoma samples, four had mutations (one case of E54 to K, two cases of E55 to K, and one case of D58 to N; Garcia-Rostan et al., 1999). One hepatoblastoma has been reported that had a 42 base pair deletion in β-catenin exon 3, which led to deletion of amino acids from S45 to D58 (Koch et al., 1999). Clearly, CKI mutations in certain tumors remain to be explored.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and transfections

The Drosophila S2R+ cell line (a line of Schneider S2 cells that respond to Wingless signaling; Yanagawa et al., 1998) and Drosophila wing imaginal disc cell line clone-8 were cultured as described (van Leeuwen et al., 1994). Expression plasmids were introduced into S2R+ cells using Effectine reagent (Qiagen). The transfectants generated with pMK33-based vectors were mixtures of stable S2R+ cell clones selected with hygromycin (200 µM). Expression of the transfected genes was induced by adding 0.5 mM CuSO4. The pMK-ZW3-HA plasmid and β-galactosidase assay with pAclacZ plasmid were as described previously (Yanagawa et al., 1997, 2000).

dsRNA production and RNAi procedures

The RNAi experiments in Drosophila S2R+ cells were performed as described previously (1 × 106 S2R+ cells were incubated for 3 days with 15 µg of dsRNA in each well of a six-well plate; Clemens et al., 2000). Individual dsRNAs were generated using a Megascript T7 transcription kit (Ambion) and the DNA templates, which were generated by PCR using sets of primers with T7 RNA polymerase binding sites. Primer sequences used to generate specific dsRNA were obtained as follows: Drosophila CKIα, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. U55848, sense primer (S-P) 457–480, anti-sense primer (AS-P) 1138–1161; CKIε, accession No. AF055583, S-P 65–89, AS-P 785–811; Dishevelled, accession No. L26974, S-P 240–259, AS-P 954–970; ZW-3, accession No. X53332, S-P 544–560, AS-P 1271–1292; CKII α subunit, accession No. M16534, S-P 259–285, AS-P 941–965; Dα-catenin, accession No. D13964, S-P 101–126, AS-P 799–828; LacZ, accession No. E00696, S-P 399–420, AS-P 1138–11162. For in vivo RNAi experiments, dsRNA for LacZ or CKIα was injected anteriorly or posteriorly into wild-type Drosophila (Canton S strain) embryos at a concentration of 2 µM. After a 48 h incubation at 18°C, the injected embryos were fixed and cuticle preparations made as described elsewhere (Willert et al., 1999).

Northern analysis

The probes for Dα-catenin, Arm and CΚΙα were 1.5 kb ClaI, 1.9 kb BamHI and 0.5 kb HincII fragments from the corresponding cDNA clones, respectively. A cDNA fragment of ribosomal protein, RP49, was used as a probe for the RNA loading control.

Immunoblot analyses and antibodies

The cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis as described previously (Yanagawa et al., 1997). Rabbit antibody against the N-terminal region of Ci (AbN; Aza-Blanc et al., 1997) and affinity-purified rabbit antibody against human CKIε (Fish et al., 1995) were gifts. The other antibodies used in this study were described previously (Yanagawa et al., 1997, 2000; Lee et al., 1999).

Whole-mount antibody staining of the embryos

Embryos injected with dsRNA for lacZ or CKIα were allowed to develop until stage 10–11. The embryos were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with monoclonal anti-Arm (N2-7A1) or anti-Engrailed (4D9) antibody using the Vectastain ABC kit and diaminobenzidine (Vector) as described previously (Noordermeer et al., 1992).

In vitro kinase assay

The stable pMK-CKIα-HA transfectants induced with CuSO4 for 14 h were co-cultured with S2-HS-Wg or plain S2 cells in the presence of CuSO4 for 3 h. From the lysates of these cells, HA-tagged CKIα was immunoprecipitated with the rabbit anti-HA antibody and protein A– Sepharose. The immune complexes were washed with lysis buffer and with kinase buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 75 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 µM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol) before being suspended in 80 µl of kinase buffer supplemented with 20 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) containing either 10 µg His-tagged Arm or 0.1 mM CKI substrate peptide (Sigma, C-2335). At 5, 10, 20 and 30 min after incubation at 30°C, 5 µl of the reaction mixture containing Arm were taken and subjected to SDS–PAGE. The 32P incorporated in Arm was detected by autoradiography. Peptide phosphorylation reactions were quantified by spotting 5 µl of reaction mixture on phosphocellulose filters (p81, Whatman). The filters were washed with 75 mM phosphoric acid and dried. Similar in vitro kinase assays were performed using ZW3- or CKIα-immunoprecipitates and the various GST–Arm fusion proteins. 32P incorporated in each substrate was quantitated using a BAS 2000 image-analyzer (Fuji film).

Pulse–chase analysis

S2R+ cells were treated for 3 days with 15 µg of dsRNA for CKIα or LacZ in six-well dishes. To determine the total protein synthesis rate, cells were pulse-labeled for 7 min with 0.8 mCi of [35S]methionine in 1 ml of M3 medium lacking methionine (Sigma). Fluorograms of the total cell lysate or the anti-Arm immunoprecipitates were prepared with En3hanceTM solution (NEN). For kinetic analysis of Arm turnover, the cells were pulse-labeled with 0.6 mCi of [35S]methionine in 1 ml of M3 medium lacking methionine for 10 min, and incubated in 1 ml of M3 medium supplemented with 25 mM unlabeled methionine containing 15 µg of CKIα- or LacZ-dsRNA. At the chase times indicated, the cells were lysed in 400 µl/well lysis buffer and centrifuged. Arm was immunoprecipitated from supernatants with 30 µl of monoclonal anti-Arm and 30 µl of goat anti-mouse IgG–Sepharose 4B (Zymed) before being subjected to SDS–PAGE.

Expression constructs

To add the HA epitope to the C-terminus of full-length Drosophila CKIα, the entire coding sequence of CKIα was amplified by RT–PCR with the single-stranded cDNA synthesized from Drosophila embryonic poly(A)+ RNA and the following set of primers: sense primer with XhoI site: 5′-TAGCTCGAGGAGCAGCTAGCCAGGATGGACAAG-3′, and anti-sense primer with SpeI site: 5′-CAGACTAGTGTCCGCGATCAGGGGCTTGCCGTT-3′. Similarly, a CKIε cDNA fragment was amplified using sense primer with XhoI site: 5′-TCACTCGAGAGAAACAGACGTAACAAAATGGAG-3′, and anti-sense primer with SpeI site: 5′-ACCACTAGTTTTGGCGTTCCCCACGCCACC-3′. The CKIα- and CKIε-RT–PCR products were double-digested with XhoI and SpeI before being cloned into the XhoI–SpeI-cleaved pMK33-HA. The resulting plasmids were named pMK-CKIα-HA and pMK-CKIε-HA, respectively. From these, plasmids expressing kinase-negative mutant of CKIα and CKIε (a lysine residue in the ATP-binding region was changed to arginine) were constructed using the Transformer™ site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech).

From myc-tagged Arm cDNA in pBluescriptII (Yanagawa et al., 1997), the various mutants described in Results were generated with QuickChange™ site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). These wild-type and mutant forms of myc-tagged-Arm cDNA were digested with BamHI and the resulting 2.7 kb fragments inserted into the BamHI site of PMK33. An Arm cDNA fragment encoding myc-tagged Arm lacking the N-terminal 58 amino acids was amplified by PCR and it was cloned into the BamHI site of pMK33. pMK-Arm-myc was double-digested with XhoI and EcoNI, then blunted and self-ligated. This plasmid, named pMK-del-Arm myc, expresses a myc-tagged Arm mutant with an N-terminal deletion that starts at the internal methionine 139.

To construct GST–Arm fusion proteins, DNA fragments encoding the N-terminal 39 amino acids (from codon 37 to codon 75) of wild-type and mutant forms of Arm were amplified using the sense primer with BamHI site: 5′-TGTGGATCCAGAATTCGTACTTGGGCGAC-3′, anti-sense primer with XhoI site: 5′-GAACTCGAGGTCCAGGTCGAACATAAG-3′ and wild-type and mutant forms of myc-tagged Arm cDNA. The fragments were double-digested with BamHI and XhoI before being ligated with BamHI–XhoI cleaved pGEX5X-3. The GST–Arm fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli XL1Blue and purified with glutathione–Sepharose CL4B beads (Amersham). His6-tag was added to the N-terminus of the full-length Arm protein as follows: the entire coding sequence of Arm was amplified by PCR using Arm cDNA, sense primer with BamHI site: 5′-ATCGGATCCATGAGTTACATGCCAGCCCAG-3′ and an anti-sense primer with a termination codon and a SalI site: 5′-TCGGTCGACCTAACAATCGGTATCGTACCA-3′. After the Arm PCR products were double-digested with BamHI and SalI, it was cloned into the BamHI–SalI-cleaved pQE30 (Qiagen). Escherichia coli was transformed with this plasmid, and under denaturing conditions, the His6 tagged-Arm protein was purified from the lysate using Ni–NTA agarose (Qiagen) and then refolded.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Y.Kitagawa for providing facilities. We also thank T.Tabata, C.V.C.Glover and D.Virship for anti-Ci and anti-Engrailed, anti-CKII and anti-CKIε antibodies, respectively. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan to S.-i.Y.

References

- Aberle H., Bauer,A., Stappert,J., Kispert,A. and Kemler,R. (1997) β-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. EMBO J., 16, 3797–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aza-Blanc P., Ramirez-Weber,F.-A., Laget,M.-P., Schwartz,C. and Kornberg,T.B. (1997) Proteolysis that is inhibited by Hedgehog targets Cubitus interruptus protein to the nucleus and converts it to a repressor. Cell, 89, 1043–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan K. and Nusse,R. (1997) Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev., 11, 3286–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens J.C., Worby,C.A., Simonson-Leff,N., Muda,M., Maehara,T., Hemmings,B.A. and Dixon,J.E. (2000) Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 6499–6503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajani R., Fraser,E., Roe,S.M., Young,N., Good,V., Dale,T.C. and Pearl,L.H. (2001) Crystal structure of glycogen synthase kinase 3β: structural basis for phosphate-primed substrate specificity and auto-inhibition. Cell, 105, 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale T.C. (1998) Signal transduction by the Wnt family of ligands. Biochem. J., 329, 209–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish K.J., Cegielska,A., Getman,M.E., Landers,G.M. and Virshup,D.V. (1995) Isolation and characterization of human casein kinase Iε (CKIε), a novel member of the CKI gene family. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 14875–14883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotow H. and Roach,P.J. (1991) Role of acidic residues as substrate determinants for casein kinase I. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 3724–3727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame S., Cohen,P. and Biondi,M. (2001) A common phosphate binding site explains the unique substrate specificity of GSK3 and its inactivation by phosphorylation. Mol. Cell, 7, 1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rostan G., Tallini,G., Herrero,A., D’Aquila,T.G., Carcangiu,M.L. and Rimm,D.L. (1999) Frequent mutation and nuclear localization of β-catenin in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res., 59, 1811–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada F. et al. (1999) Negative regulation of wingless signaling by D-Axin, a Drosophila homolog of Axin. Science, 283, 1739–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht A. and Kemler,R. (2000) Curbing the nuclear activities of β-catenin. EMBO Rep., 1, 24–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. and Struhl,G. (1998) Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signaling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature, 391, 493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A. (1999) Roles of Axin in the Wnt signaling pathway. Cell. Signal., 11, 777–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida M., Hino,S.-i., Michiue,T., Yamamoto,H., Kishida,S., Fukui,A., Asashima,M. and Kikuchi,A. (2001) Synergistic activation of the Wnt signaling pathway by DVl and casein kinase 1ε. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 33147–33155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A., Denkhaus,D., Albrecht,S., Leuschner,I., von Schweinitz,D. and Pietsh,T. (1999) Childhood hepatoblastomas frequently carry a mutated degradation targeting box of the β-catenin gene. Cancer Res., 59, 269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E., Salic,A. and Kirschner,M.W. (2001) Physiological regulation of β-catenin stability by Tcf3 and CK1ε. J. Cell Biol., 154, 983–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-S., Ishimoto,A. and Yanagawa,S.-i. (1999) Characterization of mouse Dishevelled (Dvl) proteins in Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 21464–21470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinek S., Inonog,S., Manoukian,A.S. and Young,M. (2001) A role for the segment polarity gene shaggy/GSK-3 in the Drosophila circadian clock. Cell, 105, 769–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckay R.M., Peters,J.M. and Graff,J.M. (2001a) The casein kinase I family: roles in morphogenesis. Dev. Biol., 235, 378–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckay R.M., Peters,J.M. and Graff,J.M. (2001b) The casein kinase I family in Wnt signaling. Dev. Biol., 235, 388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer J., Johnston,P., Rijsewijk,F., Nusse,R. and Lawrence,P.A. (1992) The consequences of ubiquitous expression of the wingless gene in the Drosophila embryo. Development, 116, 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai L.-M.S., Orsulic,S., Bejsovec,A. and Peifer,M. (1997) Negative regulation of armadillo, a wingless effector in Drosophila.Development, 124, 2255–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.M., Mckay,R.M., McKay,J.P. and Graff,J.M. (1999) Casein kinase I transduces Wnt signals. Nature, 401, 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton C., Woodgett,J., Hemmings,B. and Cohen,P. (1982) Multisite phosphorylation of glycogen synthase from rabbit skeletal muscle; phosphorylation of site 5 by glycogen synthase kinase-5 (casein kinase-II) is a prerequisite for phosphorylation of sites 3 by glycogen synthase kinase-3. FEBS Lett., 150, 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakis P. (2000) Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev., 14, 1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J.L., Saez,L., Blau,J., Rothenfluh,A., Abdodeely,M., Kloss,B. and Young,M.W. (1998) double-time is a novel Drosophila clock gene that regulates PERIOD protein accumulation. Cell, 94, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld B., Tice,D.A. and Polakis,P. (2001) Axin dependent phosphorylation of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein mediated by casein kinase Iε. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 39037–39045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka C., Leong,P., Xu,L., Harrison,S.D. and Williams,L.T. (1999) Casein kinase Iε in the Wnt pathway: regulation of β-catenin function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 12548–12552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos J.A., Logarinho,E., Tapia,C., Allende,C.C., Allende,J.E. and Sunkel,C.E. (1996) The casein kinase α gene of Drosophila melanogaster is developmentally regulated and the kinase activity of the protein induced by DNA damage. J. Cell Sci., 109, 1847–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried E., Chou,T.-B. and Perrimon,N. (1992) wingless signaling acts through zeste-white 3, the Drosophila homolog of glycogen synthase kinase-3, to regulate engrailed and establish cell fate. Cell, 71, 1167–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T.-Q., Lu,B., Feng,J.-J., Reinhard,C., Jan,Y.N., Fanti,W.J. and Williams,L. (2001) PAR-1 is a dishevelled-associated kinase and a positive regulator of Wnt signalling. Nature Cell Biol., 3, 628–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen F., Harryman-Samos,C. and Nusse,R. (1994) Biological activity of soluble wingless protein in cultured Drosophila imaginal disc cells. Nature, 368, 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleminckx K., Wong,E., Guger,K., Rubinfeld,B., Polakis,P. and Gumbiner,B.M. (1997) Adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein has signaling activity in Xenopus laevis embryos resulting in the induction of an ectopic dorsoanterior axis. J. Cell Biol., 136, 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K., Logan,C.Y., Arora,A., Fish,M. and Nusse,R. (1999) A Drosophila Axin homolog, Daxin, inhibits Wnt signaling. Development, 126, 4165–4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa S.-i., Lee,J.-S., Haruna,T., Oda,H., Uemura,T., Takeichi,M. and Ishimoto,A. (1997) Accumulation of Armadillo induced by Wingless, Dishevelled and dominant-negative Zeste-white 3 leads to elevated DE-cadherin in Drosophila clone 8 wing disc cells. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 25243–25251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa S.-i., Lee,J.-S. and Ishimoto,A. (1998) Identification and characterization of a novel line of Drosophila Schneider S2 cells that respond to wingless signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 32353–32359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa S.-i., Lee,J.-S., Matsuda,Y. and Ishimoto,A. (2000) Biochemical characterization of the Drosophila Axin protein. FEBS Lett., 474, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost C., Torres,M., Miller,J.R., Huang,E., Kimelman,D. and Moon,R. (1996) The axis-inducing activity and subcellular distribution of β-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev., 10, 1443–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilian O., Frei,E., Burke,R., Brentrup,D., Gutjahr,T., Bryant,P. and Noll,M. (1999) double-time is identical to discs overgrown, which is required for cell survival, proliferation and growth arrest in Drosophila imaginal discs. Development, 126, 5409–5420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]