Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) protein family acts as ‘epigenetic readers’ to identify the acetylation marks on histones that convert the acetylated lysine residues into observable phenotypes. BET proteins have gained attention due to their ability to modulate the transcription of pathology-related genes involved in cancer and autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes mellitus. However, targeting BET proteins may have secondary effects on other host cells. We aimed to elucidate possible secondary effects of BET inhibition on pancreatic beta cell function.

Methods

We studied the effect of the small-molecule BET inhibitor I-BET151 on pancreatic beta cells in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo. GTTs, ITTs and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assays were performed in healthy mice and a mouse model of diabetes following daily i.p. injections of I-BET151 for 2 weeks. Transcriptomic analysis was carried out on primary mouse islets, which were subjected to ex vivo I-BET151 treatment. Changes in expression were further validated in primary human islets.

Results

Administration of I-BET151 modestly but significantly increased glucose excursions and reduced insulin responses in both healthy mice and diabetic mice. We found that I-BET151 exposure significantly reduced the expression of Hnf4α (also known as Hnf4a; MODY1), Gck (MODY2), Hnf1α (also known as Hnf1a; MODY3), Glut2 and other genes essential for beta cell function in rat INS-1E insulinoma cells and in mouse primary islets and human islets. Global gene expression analysis in cells treated with I-BET151 showed a downregulation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)–Akt pathway. Downregulation of forkhead box protein O1, a downstream transcriptional factor of the PI3K–Akt pathway, partially rescued I-BET151-driven downregulation of Gck and insulin secretion. Likewise, islets from I-BET151-treated mice showed a modest reduction in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

Conclusions/interpretation

The results presented here suggest that BET inhibition therapy should be used with caution due to possible bimodal effects at high concentrations at the detriment of pancreatic beta cell function.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00125-025-06541-0.

Keywords: BET protein inhibitors, Beta cells, Epigenetic modulators, FOXO1, GCK, HNF4a, I-BET151, INS-1E, MODY, Pancreatic islets

Introduction

Bromodomains (BRDs) are evolutionarily conserved protein modules that act as ‘epigenetic readers’ to identify the acetylated lysine on histones and convert these signals into observable phenotypes [1]. The tandem bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins [2] comprise the ubiquitously expressed BRD2, BRD3 and BRD4 proteins and testes-specific BRDT proteins [1–3]. Inhibition of these proteins alters gene expression linked to cancer [3], type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune diseases [4].

The inhibition of BET proteins is facilitated by small-molecule inhibitors such as I-BET151 [5], JQ1 [6] and, among others, I-BET762 [7], which compete with binding for acetylated lysine on histones [8]. BET protein inhibitors have potential as therapy for various cancers; however, targeting epigenetic regulators may have secondary and unintended effects on other host cells [9–11]. Depending on the physiological context, BET proteins may directly repress gene expression or may release repression of gene expression with consequences on cell phenotype and fate [12]. For example, the BET protein inhibitors I-BET151 and JQ1 reduced erastin-mediated ferroptosis in fibrosarcoma and lung adenocarcinoma cells, while a selective block of BRD4 was found to reduce maturation of T helper (Th) 17 cells [13, 14].

In diabetes, Fu and colleagues showed that I-BET151 marginally enhanced pancreatic beta cell proliferation and regeneration in the NOD mouse model of type 1 diabetes [4, 15, 16]. Daily i.p. injection of NOD mice with I-BET151 (10 mg/kg) for 2 weeks increased expression of beta cell differentiation genes in NOD mice through dampening of pancreatic macrophage-driven inflammation. In a separate study on fetal mouse islet explants, BET inhibition was found to directly promote early endocrine fate differentiation, with increased gene expression of Ngn3, Neurod1, Mafa and Nkx6-1 [17]. These seemingly positive effects of BET inhibition were at some expense to beta cell development as JQ1 and I-BET151 treatment reduced Ins1 and Ins2 gene expression in mouse embryonic pancreatic explants and in human induced pluripotent cell (hiPSC)-derived pancreatic cells, respectively. JQ1 (≤400 nmol/l) increased insulin content in a human beta cell line EndoC-βH3 [18] and, in a separate study [19], increased basal and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), with no significant change in Ins1 expression, although Ins2 (the human insulin orthologue) was not reported in the rat beta cell line. These findings on beta cell function-related gene expression involved either endocrine progenitor cells or cell lines but not primary beta cells. Here, we evaluated the unexplored effects of I-BET151 on pancreatic beta cell functionality both in vivo, and mechanistically in vitro.

Methods

Cell culture

INS-1E cells (passage 87–100) were kindly provided by C. B. Wollheim [20]. INS-1E cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 5% (vol./vol.) FBS, 5.5 μmol/l β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mmol/l HEPES and penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics and seeded to 70% confluency prior to the start of experiments. All cells were cultured at 37°C in a Humidified incubator containing 5% CO2, with routine mycoplasma contamination detection performed monthly. I-BET151 treatment was carried out as described previously [5]. Dharmacon Rat FoxO1 Accell smartpool siRNA (Horizon Discovery, UK) and rat Gck mammalian overexpression plasmid (Twist Bioscience, USA) were incubated with 1 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 200 µl Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) unless stated otherwise.

Human islet culture

Human islets from donors without diabetes (see Human islets checklist in electronic supplementary material [ESM]) were procured from Prodo Labs (Prodo Labs, CA, USA) and cultured in Prodo Islet Media (Standard) overnight at 37°C in a Humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 prior to I-BET151 treatment.

Animal studies

C57BL/6J mice and homozygous diabetic (db/db) mice, BKS.Cg-Dock7m+/+ Leprdb/J mouse strain (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000642; https://www.jax.org/strain/000642) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained on a 12 h light–dark cycle with free access to food and water. Mice were randomly allocated to either control or experimental groups using simple randomisation method. For the in vivo treatment, 8-week-old C57BL/6J and BKS db/db mice were given an i.p. injection of either I-BET151 (10 mg/kg) or vehicle control (DMSO/[2-hydroxypropyl]-β-cyclodextrin) every morning for 3 weeks in a clean procedure room within the animal facility. To minimise animal stress, IPGTT, in vivo GSIS and ITT were performed across days in the third week, after two complete weeks of I-BET151 administration, while mouse islets were harvested at the end of week 3 (ESM Fig. 1). For the IPGTT, mice were fasted for 4 h and then given an i.p. injection of glucose (2.0 g/kg body weight). For in vivo assessment of GSIS, plasma samples were collected at 0 and 7.5 min after glucose injection for insulin determination by ELISA kit for mouse or rat insulin (Mercodia, Sweden). For the ITT, insulin (1 U/kg body weight) was administered to mice by i.p. injection after the mice had been starved for 4 h. All mice were handled as per institutional and national guidelines. All animal experiments were done with approval from institutional and university ethics committee (NTU IACUC no. A0373, no. A20026).

Mouse islets

Islets were isolated from mice by perfusing the pancreas with ice-cold collagenase (0.8 mg/ml) through the common biliary duct. Pancreas was extracted and incubated at 37°C for 5 min followed by washing and handpicking using a stereomicroscope as described previously [21].

GSIS assay

Batches of ten similar-sized islets were collected, washed and pre-incubated in 0.5% (wt/vol.) BSA-Krebs-Ringer HEPES-buffered saline (KRH) containing 2.8 mmol/l glucose (3G, low glucose condition) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. Following 3G conditioning, islets were then transferred to fresh 3G KRH for a Further 20 min followed by stimulation at a high glucose condition with KRH containing 11 mmol/l glucose (11G) (human islets) or 16.7 mmol/l glucose (16.7G) (mouse islets) for 20 min; islets were subsequently exposed to KRH containing 25 mmol/l KCl (high KCl condition) for a Further 20 min at 37°C. Insulin was then determined in the supernatant fractions incubated in low glucose, high glucose and high KCl conditions by ELISA (Mercodia, Sweden) while islet protein was determined in the pellet by BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). INS-1E cells were seeded in a six-well plate (5 × 105 cells per well) and cultured for 24 h prior to drug treatment. After treatment, cells were washed, incubated in 3G KRH at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h and GSIS was carried out similar to the procedure for islets. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Merck, USA) supplemented with Protease/Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology, USA).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analyses

After treatment, cells were lysed (RLT with β-mercaptoethanol) (Qiagen, Germany) and total RNA was isolated using RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The obtained total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). Gene expression levels were then measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using indicated gene-specific intron-spanning mouse/rat primer. Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used and the reactions were carried out in QuantStudio 6 Flex instrument (Applied Biosystems). The level of gene expression was normalised to that of β-actin. Samples with high Ct values indicating poor RNA quality or yield were excluded from the analysis. The number of experimental repeats are listed in corresponding figure legends.

RNA isolation and bulk RNA-seq

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy plus micro kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by RNA-seq library construction (Novogene, China). FASTQ files were obtained for 12 samples, consisting of six pairs of one control and one treated mouse. Basic quality control was conducted using the FASTQC (v0.11.9) [22] and MultiQC (v1.13) [23] utilities. We used STAR (v2.7.10a) [24] to map the reads to the mouse genome GRCm39 using GENCODE M30 annotations; featureCounts were then used to generate the gene counts [25]. The principal component analysis (PCA) plot revealed batch effects between sample pairs 1,2,3,4 and 5,6; we used the edgeR package (v3.38.4) to perform batch correction via the model.matrix() function [26]. edgeR and all subsequent analyses were run in the R environment (v4.2.1) [27]. Genes were considered to be significantly differentially expressed if the p value adjusted for false discovery rate <0.05. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were categorised into pathways according to their annotation in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [28–30] via the KEGG API function. Pathway activation significances were evaluated using a one-tailed hypergeometric test via the phyper function from the R ‘stats’ package.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting assays

Isolated pancreatic islets or INS-1E cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, lysed with RIPA buffer (Merck, USA) supplemented with a Protease/Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology) and the protein amount was determined in the supernatant fractions by the BCA method (Thermo Scientific Pierce, USA). Equal amounts of protein (25 µg) were separated over a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel with 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffering system and electrotransferred to PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, USA). Incubation with indicated antibodies in TBS with 5% non-fat milk was overnight at 4°C and secondary antibodies in TBS with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h. Protein bands were visualised using enhanced chemiluminescence (Cell Signaling Technology) and quantified using ImageJ (Version 2.1.0/1.54p) (NIH, USA). Sources and dilution of antibodies used can be found in ESM Table 1. Antibodies were validated in protein lysates of siRNA-knockdown or gene overexpressing INS-1E cells.

Glucokinase activity assay

Glucokinase (GCK) activity assay was performed using Glucokinase Activity Assay Kit (Fluorometric) (Abcam, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, INS-1E cells were seeded in a six-well plate and treated with either DMSO or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were lysed in the provided lysis buffer supplemented with 2.5 mmol/l dithiothreitol (DTT). The protein concentration was estimated using Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent (Bio-Rad, USA) and an equal amount of protein was loaded into a black 96-well plate. Reaction mix reagent was then added to each well and fluorescence (excitation λ 535 nm/emission λ587 nm) was measured with a plate reader in a kinetic mode for 65 min. GCK activity was then calculated as follows: sample GCK activity = extrapolated NADPH concentration / (reaction time × amount of protein added).

Immunofluorescence assay

INS-1E cells grown on a coverslip were treated with either DMSO or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were fixed in 4% (wt/vol.) paraformaldehyde, permeabilised with 1% Triton-X100, and stained with rabbit anti-forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) antibody (1:500) (Cell Signaling Technology), goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DAPI (1:2000). Z-stack confocal images were captured, and the mean fluorescence intensity of maximum projection images were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

Cut&Run qPCR assay

INS-1E cells were seeded on a six-well plate for 24 h prior to exposure to DMSO (vehicle control) or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h. Following the treatment, cells were trypsinised and 450,000 cells were fixed with 0.1% methanol-free formaldehyde (Thermo Scientific, USA), with 150,000 cells used for each reaction. Cut&Run assay was performed using Cut&Run Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with anti-FOXO1 (C29H4) rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) and negative control Rabbit (DA1E) mAb IgG XP Isotype Control (Cell Signaling Technology). Subsequently, qPCR was carried out on the Cut&Run FOXO1 antibody-targeted cleaved DNA eluate, rabbit isotype control antibody-targeted cleaved DNA eluate, and input DNA for putative FOXO1 binding sites in Gck and Ins2 promoter region.

Masking/blinding

No masking/blinding of experimenters was performed.

Statistical analysis

All data collected were subjected to normality testing (Shapiro–Wilk test) prior to analysis. Data, if normally distributed, were presented as mean ± SEM, with the number of experimental replicates listed in each corresponding figure legend. Non-normal data were presented as median with IQR. All data were analysed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.0) (Dotmatics, Boston, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t test, Mann–Whitney test, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett T-3 test or two-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak’s test; the threshold p value of <0.05 denoted statistical significance.

Results

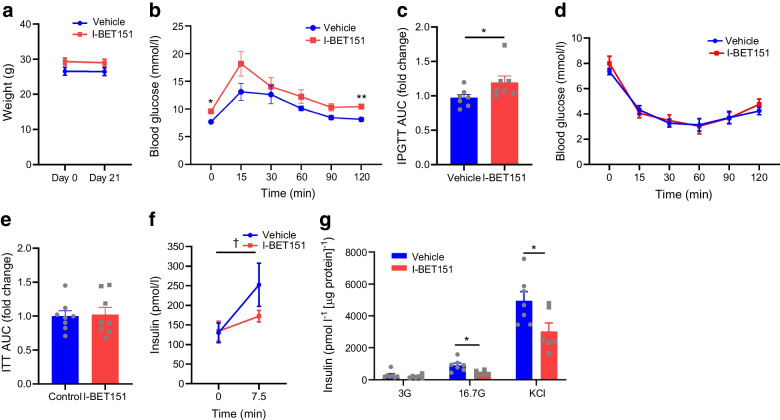

Inhibition of BET proteins via I-BET151 reduced insulin secretion in healthy C57B/6J mice

I-BET151 (10 mg/kg) [4, 31] or vehicle (DMSO/[2-hydroxypropyl]-β-cyclodextrin) was administered daily by i.p. injection to healthy 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice. Glucose tolerance, in vivo GSIS and insulin tolerance tests were performed after 2 weeks of daily I-BET151 injection before islets were harvested at the end of 3 weeks (ESM Fig. 1). While there was no significant change in body weight in healthy mice treated with I-BET151 (Fig. 1a), there was a slight but significant increase in glucose excursion following glucose load in the IPGTT (Fig. 1b, c). An ITT showed no significant difference across timepoints following insulin administration (Fig. 1d, e). However, we did find a significant reduction in plasma insulin following i.p. glucose administration in I-BET151-treated mice compared with the control-treated mice (Fig. 1f). Ex vivo islet insulin secretion following either high glucose or high potassium stimulation revealed significantly reduced insulin secretion in I-BET151-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1.

Reduced insulin secretion in healthy mice treated with I-BET151. (a) No change in body weight of 8-week-old C57BL6/J mice treated with an i.p. injection of either I-BET151 (10 mg/kg) or vehicle control (DMSO/[2-hydroxypropyl]-β-cyclodextrin) daily for 3 weeks, n=7. (b) Increased glucose excursion following bolus i.p. administration of glucose in mice treated with I-BET151 compared with vehicle, n=7. (c) Glucose AUC for the IPGTT shown in (b). (d) Modest and insignificant changes in insulin sensitivity of mice treated with I-BET151 compared with vehicle, n=8. (e) Glucose AUC for the ITT shown in (d). (f) In vivo insulin secretion following bolus glucose administration (2 g/kg) was significantly lower in I-BET151-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice, n=10. (g) Islets were harvested from I-BET151-treated and vehicle-treated mice and used for GSIS determination, n=6 or 7. Data are presented as means ± SEM, or as median ± IQR for non-normally distributed data. For comparison of two groups (e), p values were determined using unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. For comparison of two groups with non-normally distributed data (c), p value was determined using Mann–Whitney U test. For comparison of groups with two variables (a, b, d, f, g), p values were calculated with two-way ANOVA test with post hoc Sidak’s test. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 for I-BET151 vs vehicle; †p<0.05 for 7.5 min vs 0 min

Inhibition of BET proteins via I-BET151 exacerbated whole-body glucose homeostasis in the mouse model type 2 diabetes

Next, we administered diabetic BKS db/db mice as with healthy mice with the same i.p. dose of I-BET151 for 3 weeks, and performed IPGTT, in vivo GSIS assessment and ITT, as before (i.e. after 2 weeks of I-BET151 administration); islets were harvested after 3 weeks (ESM Fig. 1). While the db/db mice (mirroring type 2 diabetes) displayed minimal and non-significant weight loss (Fig. 2a), I-BET151 treatment significantly increased the already high glucose excursion at 15 min, 30 min and 60 min in the IPGTT when compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 2b, c). Further ITT analysis showed no significant difference, suggesting no changes in peripheral insulin resistance between I-BET151- and vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2d, e). We observed a significant decrease in plasma insulin following i.p. glucose load, suggesting that the observed impact of I-BET151 on blood glucose homeostasis leaned towards a beta cell-driven rather than a peripheral insulin resistance phenotype (Fig. 2f). This was further validated by the ex vivo GSIS assay of pancreatic islets harvested from the vehicle- and I-BET151-treated mice (Fig. 2g). Contrary to a prior report made on the beneficial impact of I-BET151 on beta cell function in NOD mice [4], I-BET151 in our hands reduced insulin secretion in both healthy mice and diabetic mice. Importantly, a difference between our mouse model and NOD mice is the inflammation status, with Fu and colleagues reporting a significant suppression of NF-κB transcripts in I-BET151-treated pancreatic CD45+ leukocytes [4]. On the contrary, we found no significant difference in serum TNF-α and IL-1β, two cytokines under the control of the NF-κB pathway, when comparing vehicle-treated db/db mice with I-BET151-treated db/db mice, or when comparing vehicle-treated db/db mice with their lean counterparts (ESM Fig. 2a, b), suggesting minimal impact on systemic inflammation. It is worth noting that ex vivo I-BET151 exposure of pancreatic islets led to a modest decrease in islet Tnf expression and a significant reduction in Il1b transcript expression (ESM Fig. 2c, d). This disparity between systemic inflammation and islet inflammatory transcripts suggests that indirect effects of I-BET151, through peripheral tissues, on islet beta cells cannot be ruled out.

Fig. 2.

I-BET151 treatment lowers beta cell Function in a type 2 diabetes mouse model (BKS db/db mice). (a) Modest but insignificant change in body weight of 8-week-old BKS db/db mice treated with an i.p. injection of either I-BET151 (10 mg/kg) or vehicle control (DMSO/[2-hydroxypropyl]-β-cyclodextrin) daily for 3 weeks, n=8. (b) Increased glucose excursion following bolus i.p. administration of glucose in mice treated with I-BET151 compared with vehicle, n=8. (c) Glucose AUC for the IPGTT shown in (b). (d) Modest and insignificant changes in insulin sensitivity of mice treated with I-BET151 compared with vehicle, n=8. (e) Glucose AUC for the ITT shown in (d). (f) In vivo insulin secretion following bolus glucose administration (2 g/kg) was significantly lower in I-BET151-treated mice than in vehicle-treated mice, n=6. (g) Islets from I-BET151-treated and vehicle-treated mice were harvested and used for GSIS determination, n=4. Data are presented as means ± SEM. For comparison of two groups (c, e), p values were determined using unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. For comparison of groups with two variables (a, b, d, f, g), p values were calculated with two-way ANOVA test with post hoc Sidak’s test. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 for I-BET151 vs vehicle; ††p<0.01 for 7.5 min vs 0 min

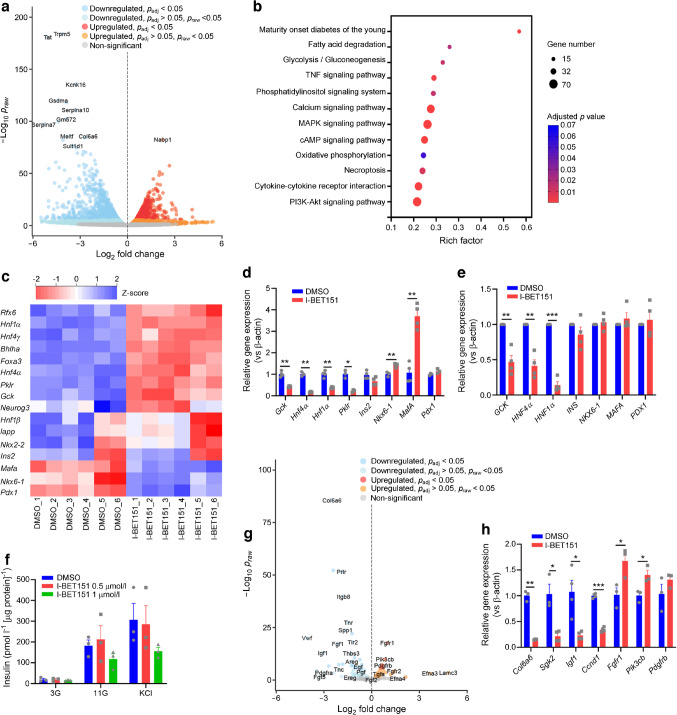

Ex vivo I-BET151 treatment of primary mouse and Human islets reveals dysregulation in MODY gene expression and phosphoinositide-3-kinase–Akt signalling

We next performed a bulk RNA-seq analysis on pancreatic islets isolated from healthy mice and exposed for 24 h to 1 µmol/l I-BET151, a concentration that impeded myeloma cell proliferation [32] and reduced transcription of Myc (a notable proto-oncogene) in islets (ESM Fig. 2e) [32]. Our RNA-seq analysis revealed 1888 significantly upregulated genes and 2418 significantly downregulated genes in I-BET151-treated islets (Fig. 3a). Further KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs identified MODY, TNF signalling, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, calcium signalling and phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)–Akt signalling as top signalling pathways altered in I-BET151 treated mice (Fig. 3b and ESM Fig. 3a–i). In addition, Rfx6, Hnf1α (also known as Hnf1a), Hnf4γ (also known as Hnf4g), Bhlha15, Foxa3, Hnf4α, Pklr, Gck, Neurog3, Hnf1β (also known as Hnf1b), Iapp and Nkx2-2 transcripts were also significantly downregulated in I-BET151-treated islets (Fig. 3c). The observed downregulation of MODY genes, including Hnf4α (MODY1), Gck (MODY2) and Hnf1α (MODY3), was further validated using qPCR (Fig. 3d). While a large proportion of MODY genes were downregulated, Mafa and Nkx6-1 were significantly upregulated (validated by qPCR) in islets exposed to I-BET151 (Fig. 3c, d). Importantly, mRNA levels of Ins2, the downstream target of Nkx6-1, MafA and Pdx1 [33–35], were unchanged in I-BET151- vs vehicle-treated islets (Fig. 3c, d), suggesting that the reduction in beta cell function was limited to genes involved in glucose sensing and insulin release with no observed impact on insulin transcripts. Similarly, ex vivo treatment of Human islets with 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h led to significant downregulation of HNF4α, GCK and HNF1α mRNA, while PDX1, NKX6–1, MAFA and INS mRNA remained unchanged (Fig. 3e). This observed downregulation of a subset of human beta cell genes translated to only a modest (p>0.05) reduction in insulin response to high glucose condition (11G), suggesting limited impact on Human beta cell Function, which accounts for only 60% of all Human islet cells, compared with 80% in mouse islets (Fig. 3f) [36].

Fig. 3.

Alteration of transcriptome in healthy islets treated with I-BET151. (a) Volcano plot of genes upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) in healthy mouse islets treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=6. (b) KEGG pathway clustering analysis of DEGs in healthy mouse islets treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=6. (c) Heatmap displaying upregulated (blue) or downregulated (red) genes clustered under the KEGG term ‘MODY’, n=6. (d) qPCR analysis of MODY genes in healthy mouse islets treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=3 or 4. (e) qPCR analysis of MODY genes in isolated human islets treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=4. (f) GSIS analysis of isolated human islets treated with either vehicle control (DMSO), 0.5 µmol/l I-BET151 or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=3. (g) Volcano plot of genes clustered under the KEGG term ‘PI3K/Akt signalling pathway’ that were upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) in healthy mouse islets exposed to either DMSO or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=6. (h) qPCR analysis of PI3K/Akt signalling pathway genes in healthy mouse islets treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=3 or 4. Data are presented as means ± SEM. For comparison of two groups (d, e, h), p values were determined using unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. For comparison of groups with two variables (f), p values were calculated with two-way ANOVA test with post hoc Sidak’s test. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001

PI3K–Akt signalling was another notable KEGG pathway term that emerged from the RNA-seq results, because it regulates insulin secretion and signalling (Fig. 3g) [37, 38]. It is also worth noting that IGF1 signalling through IGF receptor 1 (IGFR1)–Akt–FOXO1 was reported to increase GCK expression in beta cells [39], while the downregulation of PI3K–Akt–FOXO1 axis impaired insulin secretion in islets of post-severe burn dysglycaemia in rats [40]. During our RNA-seq analysis of I-BET151-treated mouse pancreatic islets, we found that I-BET151 significantly downregulated genes for growth factors (e.g. Igf1), PI3K activators within the extracellular matrix (e.g. Col6a6), cell cycle regulator (Ccnd1) and FOXO1 activity regulator (Sgk2) (Fig. 3g). Further, qPCR validated these changes in mouse pancreatic islets (Fig. 3h). Hence, the observed reduced beta cell function in I-BET151-treated islets could be, in part, due to dysregulated PI3K–Akt–FOXO1 signalling.

Downregulation of GCK by I-BET151 contributes to beta cell dysfunction

Exposure to I-BET151 (1 µmol/l) for 24 h significantly reduced insulin secretion in response to high glucose condition (16.7G) and high KCl (25 mmol/l) in INS-1E cells, a rat beta cell line (ESM Fig. 4a), suggesting that I-BET151 may lead to derangements in secretory pathways and not just glucose sensing. Similar to mouse islets, I-BET151 (0.1–1 μmol/l) exposure for 24 h significantly reduced mRNA expression of Myc (ESM Fig. 4b). I-BET151 (1 µmol/l) exposure for 24 h led to significant downregulation of MODY gene expression, including Gck, Hnf4α and Hnf1α (Fig. 4a), in a dose-dependent manner (0.1–1 µmol/l) (ESM Fig. 4c). I-BET151 (1 μmol/l) exposure for 4 h reduced the expression of genes associated with type 2 diabetes, including Tcf7l2, Grb14, Glis3, Xrcc4 and Manf (Fig. 4b). Changes in GCK, hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF) 4α and HNF1α protein levels were validated using western immunoblotting, with all three proteins being significantly reduced in INS-1E cells treated with I-BET151 for 24 h (but not 4 h) when compared with vehicle (Fig. 4c, d). However, not all genes were reduced. Pdx1, Ins1 and Ins2 were significantly increased in INS-1E cells treated with 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h (Fig. 4a), suggesting again that reduced beta cell function in I-BET151-treated cells is not driven by reduced insulin production (ESM Fig. 4d, e) but perhaps by a dysregulated metabolic amplification pathway that involves reduced expression of metabolism rate-limiting enzymes. It is worth noting that the observed increase in Pdx1, Ins1 and Ins2 transcript expression in INS-1E cells, which was not observed in I-BET151-treated primary islets (Fig. 3c–e), may translate to the observed modest increase in insulin release during fasting condition (3G) in I-BET151-treated INS-1E cells but not in primary islets (Fig. 1g and ESM Fig. 4a). Despite an increase in Pdx1, Ins1 and Ins2 transcript expression, the impact of I-BET151 on the reduction of insulin release during glucose stimulation (16.7G) in INS-1E cells is still consistent with our observation in primary islets (ESM Fig. 4a). Furthermore, Glut2, a downstream pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) effector gene, remained reduced, thereby suggesting that the compensatory increase in Pdx1 did not rescue the detrimental effect of I-BET151 on beta cell insulin response (Fig. 4a) [41]. Altogether, these findings support a partially dysregulated state of beta cells following I-BET151 exposure. Importantly, the dysregulation of MODY and type 2 diabetes genes was similarly observed following treatment of INS-1E cells with two other BET inhibitors, JQ1 and I-BET762 (ESM Fig. 4f–i).

Fig. 4.

I-BET151 diminishes the insulin response in INS-1E cells. (a) qPCR analysis of MODY gene expression in INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 4 h or 24 h, n=3–5. (b) qPCR analysis of type 2 diabetes GWAS genes, specifically Tcf7l2, Grb14, Glis3, Xrcc4 and Manf, in INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 4 h or 24 h, n=4. (c, d) Representative western immunoblot (c) and quantification (d) of HNF4α, HNF1α and GCK in INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 4 h or 24 h, n=5. (e, f) Western immunoblot (e) and quantification (f) of GCK in INS-1E cells transfected with either GCK mammalian expression vector (GCK-OE) or empty vector, prior to treatment with either DMSO or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=4. (g, h) GSIS assay in wild-type (g) and GCK-OE INS-1E cells (h), treated with either DMSO or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=5 or 6. Data are presented as means ± SEM. For comparison of more than two groups (a, b, d), p values were calculated with one-way ANOVA test with post hoc Dunnett’s T3 test. For comparison of groups with two variables (f, g, h), p values were calculated with two-way ANOVA test with post hoc Sidak’s test. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001. GWAS, genome-wide association study; WT, wild-type

Due to its apex role in the beta cell glucose sensing pathway, we further validated the reduction of GCK activity in I-BET151-treated INS-1E cells (ESM Fig. 4j). Transient overexpression of GCK in INS-1E cells (Fig. 4e, f) rescued I-BET151-induced decline in GSIS, with I-BET151 treatment significantly reducing insulin release during 16.7G stimulation in control-vector cells (Fig. 4g) but not in GCK-overexpressing (GCK-OE) cells (Fig. 4h). There was no difference in high-KCl-stimulated insulin secretion following I-BET151 treatment in both wild-type and GCK-OE cells (Fig. 4g, h). These findings suggest that the loss of GCK in I-BET151 treatment contributed to the reduced beta cell response to high glucose. As previously described, DMSO-treated (vehicle control) GCK-OE cells displayed significantly higher levels of insulin release at basal glucose levels (3G) while insulin release during high glucose stimulation (16.7G) was similar when compared with control cells (Fig. 4g) owing perhaps to the elevated rates of glycolysis especially in low glucose conditions [42].

I-BET151 downregulated GCK expression through the induction of FOXO1 protein

Hnf4α (MODY1), Gck (MODY2) and Hnf1α (MODY3) were consistently downregulated in both I-BET151-treated INS-1E cells and primary islets. A transcription factor common to these three MODY genes that was altered in the opposite direction (overexpressed) following I-BET151 treatment is FOXO1. FOXO1 has been reported to act antagonistically against HNF4α on glycolysis-related genes, including the glycolytic rate-limiting enzyme GCK [43]. Notably, a ChIP-seq analysis of FOXO1 in mouse pancreatic islets revealed a FOXO1 binding site in the promoter region of Gck [44]. Similarly, a FOXO1 binding site was also reported in the Gck promoter region in INS-1E cells [39]. In our study, we observed a significant increase in Foxo1 mRNA expression in INS-1E cells treated with 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h (Fig. 5a) and the total FOXO1 protein was significantly increased after treatment with I-BET151 for 4, 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5b–d). This induction of FOXO1 protein was also observed in I-BET151-treated mouse islets (Fig. 5e, f). Importantly, phosphorylated FOXO1 (inactive form) only marginally increased in tandem with total FOXO1 protein across all timepoints of I-BET151 treatment (Fig. 5b, d, e, g), suggesting that the unphosphorylated active form of FOXO1 may play a more prominent role following I-BET151 treatment. Indeed, we observed a significantly higher nuclear presence of FOXO1 in I-BET151-treated INS-1E cells compared with DMSO-treated cells (ESM Fig. 5a–c). Furthermore, Cut&Run qPCR for FOXO1 binding sites showed increased binding of FOXO1 to sites within 2 kb upstream of transcription start sites of downstream targets Gck and Ins2 (−1208 bp and −130 bp, respectively) in I-BET151-treated INS-1E cells (Fig. 5h and ESM Fig. 5d) [44, 45]. The knockdown of FOXO1 protein in INS-1E cells mitigated I-BET151-induced downregulation of GCK protein (Fig. 5i–k). Interestingly, this rescue of I-BET151-mediated downregulation of GCK via the knockdown of FOXO1 was independent of HNF4A and HNF1A, as both proteins were unchanged in I-BET151-treated FOXO1-knockdown cells and control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 5i, j). Importantly, GSIS analysis revealed a significant increase in insulin release in I-BET151-treated Foxo1 siRNA cells compared with I-BET151-treated control siRNA cells when stimulated by high glucose (16.7G) (Fig. 5k), suggesting that the I-BET151-mediated reduction of beta cell function through the downregulation of GCK protein was in part facilitated by FOXO1. Altogether, these findings suggest that FOXO1 is involved in I-BET151-mediated reduction in insulin secretion and that this effect occurs through a rescue of Gck expression.

Fig. 5.

I-BET151 mediates a decline in beta cell function through induction of FOXO1. (a) qPCR analysis of Foxo1 mRNA levels in INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 4 h and 24 h, n=8. (b) Representative western blot of FOXO1 and p-FOXO1 in INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 4 h, 24 h and 48 h. (c, d) Densitometric quantification of FOXO1 (c) and p-FOXO1/total FOXO1 (d) from the western blot images shown in (b), n=4. (e–g) Representative western blot of FOXO1 and p-FOXO1 (e), and densitometric quantification of FOXO1 (f) and p-FOXO1/total FOXO1 (g), in healthy mouse pancreatic islets treated with either vehicle control or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=4. (h) Cut&Run qPCR of FOXO1 binding on the Gck promoter region (1208 bp upstream of transcriptional start site) in INS-1E cells treated with DMSO or 1 µmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=4. (i, j) FOXO1-knockdown INS-1E cells, obtained by treating INS-1E cells with either 5 nmol/l control siRNA or Foxo1 siRNA for 24 h, were treated with 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h. A representative western blot of FOXO1, p-FOXO1, HNF4α, HNF1α and GCK (i) and their densitometric quantification (j) in control or FOXO1-knockdown INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h are shown, n=4. (k) GSIS assay in control and FOXO1-knockdown INS-1E cells treated with either vehicle control or 1 μmol/l I-BET151 for 24 h, n=9. Data are presented as means ± SEM. For comparison of two groups (f, g, h), p values were determined using unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. For comparison of more than two groups (a, c, d), p values were calculated with one-way ANOVA test with post hoc Dunnett’s T3 test. For comparison of groups with two variables (j, k), p values were calculated with two-way ANOVA test with post hoc Sidak’s test. *p<0.05,**p<0.01 and ***p<0.001

Discussion

BET inhibition remains a therapeutic avenue for a myriad of diseases including cancer and autoimmune diabetes [4, 46–49]. However, our study presents a potential drawback of BET inhibition regarding its impact on healthy and type 2 diabetes pancreatic beta cell function, with effects on whole-body glucose homeostasis. Exposure of beta cells to I-BET151, albeit at a single tested concentration that is known to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in myeloma cell line H2929 [32], downregulated a plethora of beta cell function-related genes, including MODY genes Gck, Hnf4α and Hnf1α in INS-1E cells and mouse primary islets and the same genes in human islets. At this relatively high dose (an anticancer working dose), Mafa and Nkx6-1 were upregulated, corroborating earlier findings; however, Ins2 transcripts remained unchanged in primary islets. The lack of change in Ins2 mRNA opposes earlier reports where BET inhibition either increased transcription and content of Ins1 and Ins2 or strongly reduced Ins1 expression [17, 19]. These discrepancies point towards BET inhibition having a possible bimodal effect whereby a loss of beta cell function genes triggers cellular insulin production at low doses of BET inhibitor, with this compensation being lost at high doses.

The observed downregulation of MODY genes in I-BET151-treated beta cells suggests a dysregulation of insulin secretion. Indeed, healthy mice displayed more severe glucose intolerance due to a lowered insulin response after 2 weeks of I-BET151 administration. However, this observed deleterious effect of I-BET151 on beta cell Function contradicts findings from a mouse model of autoinflammatory type 1 diabetes wherein I-BET151 increased insulin response. This difference could be explained by the highly proinflammatory environment in a type 1 diabetes setting and possibly that I-BET151 dampens whole-body inflammation more so than the endocrine pancreas [31]. Hu and colleagues showed this in myeloid-lineage-specific Brd4-knockout mice, with the mice being protected against high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and displaying an underlying reduction in systemic inflammation [50]. In our hands, mice treated with I-BET151 showed no changes in circulating TNF-α or IL-1β levels, confirming the need to balance dampening of systemic inflammation with reduction in expression of beta cell genes.

To understand the impact of I-BET151 on MODY genes, we further conducted a transcriptomic analysis, revealing that the PI3K–Akt pathway was affected by I-BET151. Multiple proteins in this pathway have been reported to lower mouse islet function. The reduction of stimulatory growth factors, such as IGF-1, impedes beta cell proliferation and increases its susceptibility to cell death through the PI3K–Akt–FOXO1 pathway [51–53]. I-BET151 decreased collagen-related factors, such as Col6a6, which has been implicated previously in high-fat-diet-induced beta cell dysfunction [54]. The downregulation of Ccnd1, a gene known to be repressed by FOXO1, further corroborates an I-BET151-mediated dysregulation of the PI3K–Akt–FOXO1 pathway [55, 56]. Of all the I-BET151-mediated DEGs, from Igf1 to Col6a6 and Ccnd1, Gck downregulation caught attention because it represents an important first step in glycolysis (i.e. phosphorylation of glucose), which would impede the beta cell GSIS pathway. We found that I-BET151 treatment of INS-1E cells reduced GCK activity, with reduced conversion of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate. Here, we show that FOXO1 protein was elevated in I-BET151-treated primary islets and INS-1E cells, with no significant difference found in the ratio of phosphorylated FOXO1 protein (inactive) to total FOXO1 protein, suggesting an increase in FOXO1 activity and corroborating observations in different cell lines [57, 58]. Furthermore, FOXO1 was also previously identified as a repressor of GSIS and multiple beta cell function-related genes, including Gck, Glut2, Pdx1 and Ins2 [43, 45, 59, 60]. Importantly, FOXO1 is tightly regulated by the PI3K–Akt pathway and I-BET151-mediated dysregulation of this pathway could potentially result in either increased nuclear retention or enhanced stability of FOXO1, consequently leading to the observed repression of Gck (Fig. 4a) [61]. Increased FOXO1 binding to the Gck promoter region and repression of Gck expression was indeed observed in I-BET151-treated cells, and this contributes to the loss of beta cell function. To confirm this, FOXO1 knockdown prevented I-BET151-induced decline in GCK protein and improved GSIS in INS-1E cells. Further work using primary mouse and human cells exposed to I-BET151 and FOXO1 modulation will be required to validate this.

In conclusion, while BET inhibitors prove to be an effective anticancer measure in clinical trials, it is vital to prepare for possible diabetogenic side effects. Further investigations into the impact of I-BET151-induced dysregulation of FOXO1 activity and MODY genes in other metabolic organs such as liver and muscle will provide a more holistic picture.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- 3G

2.8 mmol/l glucose

- 11G

11 mmol/l glucose

- 16.7G

16.7 mmol/l glucose

- BET

Bromodomain and extra-terminal

- BRD

Bromodomain

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- FOXO1

Forkhead box protein O1

- GCK

Glucokinase

- GCK-OE

GCK-overexpressing

- GSIS

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- HNF

Hepatocyte nuclear factor

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KRH

Krebs-Ringer HEPES-buffered saline

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Wollheim (Excellence of Diabetes Research in Sweden, Lund University, Sweden) for providing us the INS-1E cells. We also thank J. Feng (Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) for helping with the experiments involving the overexpression constructs and gene expression.

Data availability

Volcano plots of significant KEGG pathways listed in Fig. 3b can be found in the ESM. All other datasets are available from the corresponding author on request.

Funding

YA is supported by the Ministry of Education Singapore (MOE-T2EP30221-0003, 2019-T1-001-059, RG30/23) and the National Research Foundation (NRF2020-THE003-0006). This work was also partly supported by the LKCMedicine Healthcare Research Fund (Diabetes Research), established through the generous support of alumni of Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. DK is supported by the NUS Research Scholarship for his PhD. AKKT is supported by IMCB, A*STAR, HLTRP/2022/NUS-IMCB-02, OFIRG21jun-0097, CSASI21jun-0006, MTCIRG21-0071, H22G0a0005, I22D1AG053, HLCA23Feb-0031, SC36/19-000801-A044, H24G1a0015 and M24N2K0087. GAR is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (WT212625/Z/18/Z), MRC Programme grant (MR/R022259/1), Diabetes UK (BDA 16/0005485) and NIH-NIDDK (R01DK135268) project grants, a CIHR-Breakthrough T1D (formerly known as JDRF) Team grant (CIHR-IRSC TDP-186358 and JDRF 4-SRA-2023-1182-S-N), CRCHUM start-up funds and an Innovation Canada John R. Evans Leader Award (CFI 42649).

Authors’ relationships and activities

AKKT is a co-founder and shareholder of BetaLife Pte Ltd but is not employed by BetaLife Pte Ltd. GAR has received grant funding from, and is a consultant for, Sun Pharmaceuticals Inc. The authors declare that there are no other relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Contribution statement

QWCH and YA designed the study and wrote the manuscript. GAR and AKKT provided input on the study design. QWHC, DG, RC, HJB, XYC, SD, VST, DK, XW and DYT performed the experiments. JAM and BL analysed and generated figures for the RNA-seq data. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. YA supervised the project and is the guarantor of this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ntranos A, Casaccia P (2016) Bromodomains: translating the words of lysine acetylation into myelin injury and repair. Neurosci Lett 625:4–10. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taniguchi Y (2016) The Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal domain (BET) family: functional anatomy of BET paralogous proteins. Int J Mol Sci 17(11):1849. 10.3390/ijms17111849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyce A, Degenhardt Y, Bai Y et al (2013) Inhibition of BET bromodomain proteins as a therapeutic approach in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 4(12):2419–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu W, Farache J, Clardy SM et al (2014) Epigenetic modulation of type-1 diabetes via a dual effect on pancreatic macrophages and β cells. eLife 3:e04631. 10.7554/eLife.04631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson MA, Prinjha RK, Dittmann A et al (2011) Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature 478:529. 10.1038/nature10509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S et al (2010) Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468(7327):1067–1073. 10.1038/nature09504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicodeme E, Jeffrey KL, Schaefer U et al (2010) Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature 468:1119. 10.1038/nature09589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrieu G, Belkina AC, Denis GV (2016) Clinical trials for BET inhibitors run ahead of the science. Drug Discov Today Technol 19:45–50. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaidos A, Caputo V, Karadimitris A (2015) Inhibition of bromodomain and extra-terminal proteins (BET) as a potential therapeutic approach in haematological malignancies: emerging preclinical and clinical evidence. Ther Adv Hematol 6(3):128–141. 10.1177/2040620715576662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertz JA, Conery AR, Bryant BM et al (2011) Targeting MYC dependence in cancer by inhibiting BET bromodomains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(40):16669–16674. 10.1073/pnas.1108190108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazur PK, Herner A, Mello SS et al (2015) Combined inhibition of BET family proteins and histone deacetylases as a potential epigenetics-based therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Med 21(10):1163–1171. 10.1038/nm.3952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis GV (2001) Duality in bromodomain-containing protein complexes. Front Biosci 6:D849-852. 10.2741/denis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung K, Lu G, Sharma R et al (2017) BET N-terminal bromodomain inhibition selectively blocks Th17 cell differentiation and ameliorates colitis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(11):2952–2957. 10.1073/pnas.1615601114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang M, Liu K, Chen P, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang J (2022) Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) as an epigenetic regulator of fatty acid metabolism genes and ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis 13(10):912. 10.1038/s41419-022-05344-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehuen A (2015) A double-edged sword against type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 372(8):778–780. 10.1056/NEJMcibr1414708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson PJ, Shah A, Apostolopolou H, Bhushan A (2019) BET proteins are required for transcriptional activation of the senescent islet cell secretome in type 1 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 20(19):4776. 10.3390/ijms20194776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huijbregts L, Petersen MBK, Berthault C et al (2019) Bromodomain and extra terminal protein inhibitors promote pancreatic endocrine cell fate. Diabetes 68(4):761–773. 10.2337/db18-0224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu M, Kim I, Moran I et al (2024) Multiple genetic variants at the SLC30A8 locus affect local super-enhancer activity and influence pancreatic beta-cell survival and function. FASEB J 38(8):e23610. 10.1096/fj.202301700RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deeney JT, Belkina AC, Shirihai OS, Corkey BE, Denis GV (2016) BET bromodomain proteins Brd2, Brd3 and Brd4 selectively regulate metabolic pathways in the pancreatic beta-cell. PLoS One 11(3):e0151329. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merglen A, Theander S, Rubi B, Chaffard G, Wollheim CB, Maechler P (2004) Glucose sensitivity and metabolism-secretion coupling studied during two-year continuous culture in INS-1E insulinoma cells. Endocrinology 145(2):667–678. 10.1210/en.2003-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng X, Ho QWC, Chua M et al (2022) Destabilization of beta Cell FIT2 by saturated fatty acids alter lipid droplet numbers and contribute to ER stress and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119(11):e2113074119. 10.1073/pnas.2113074119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrews S (2010) FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available from: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed 8 Dec 2024

- 23.Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S, Kaller M (2016) MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32(19):3047–3048. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F et al (2013) STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29(1):15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frankish A, Diekhans M, Ferreira AM et al (2019) GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 47(D1):D766–D773. 10.1093/nar/gky955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26(1):139–140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

- 28.Kanehisa M (2019) Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci 28(11):1947–1951. 10.1002/pro.3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Ishiguro-Watanabe M (2023) KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 51(D1):D587–D592. 10.1093/nar/gkac963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa M, Goto S (2000) KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28(1):27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi X, Marmontel de Souza B, Sawatani T et al (2022) Mining the transcriptome of target tissues of autoimmune and degenerative pancreatic beta-cell and brain diseases to discover therapies. iScience 25(11):105376. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaidos A, Caputo V, Gouvedenou K et al (2014) Potent antimyeloma activity of the novel bromodomain inhibitors I-BET151 and I-BET762. Blood 123(5):697–705. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritz-Laser B, Gauthier BR, Estreicher A et al (2003) Ectopic expression of the beta-cell specific transcription factor Pdx1 inhibits glucagon gene transcription. Diabetologia 46(6):810–821. 10.1007/s00125-003-1115-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor BL, Liu FF, Sander M (2013) Nkx6.1 is essential for maintaining the functional state of pancreatic beta cells. Cell Rep 4(6):1262–1275. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Brun T, Kataoka K, Sharma AJ, Wollheim CB (2007) MAFA controls genes implicated in insulin biosynthesis and secretion. Diabetologia 50(2):348–358. 10.1007/s00125-006-0490-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cabrera O, Berman DM, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Berggren PO, Caicedo A (2006) The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(7):2334–2339. 10.1073/pnas.0510790103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang X, Liu G, Guo J, Su Z (2018) The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Biol Sci 14(11):1483–1496. 10.7150/ijbs.27173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manning BD, Cantley LC (2007) AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell 129(7):1261–1274. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida K, Murao K, Imachi H et al (2007) Pancreatic glucokinase is activated by insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocrinology 148(6):2904–2913. 10.1210/en.2006-1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B, Sun P, Shen C et al (2020) Role and mechanism of PI3K/AKT/FoxO1/PDX-1 signaling pathway in functional changes of pancreatic islets in rats after severe burns. Life Sci 258:118145. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waeber G, Thompson N, Nicod P, Bonny C (1996) Transcriptional activation of the GLUT2 gene by the IPF-1/STF-1/IDX-1 homeobox factor. Mol Endocrinol 10(11):1327–1334. 10.1210/mend.10.11.8923459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, Iynedjian PB (1997) Modulation of glucose responsiveness of insulinoma beta-cells by graded overexpression of glucokinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94(9):4372–4377. 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langlet F, Haeusler RA, Linden D et al (2017) Selective inhibition of FOXO1 activator/repressor balance modulates hepatic glucose handling. Cell 171(4):824–835. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo T, Kraakman MJ, Damle M, Gill R, Lazar MA, Accili D (2019) Identification of C2CD4A as a human diabetes susceptibility gene with a role in beta cell insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(40):20033–20042. 10.1073/pnas.1904311116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meur G, Qian Q, da Silva Xavier G et al (2011) Nucleo-cytosolic shuttling of FoxO1 directly regulates mouse Ins2 but not Ins1 gene expression in pancreatic beta cells (MIN6). J Biol Chem 286(15):13647–13656. 10.1074/jbc.M110.204248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrison CN, Gupta VK, Gerds AT et al (2022) Phase III MANIFEST-2: pelabresib + ruxolitinib vs placebo + ruxolitinib in JAK inhibitor treatment-naive myelofibrosis. Future Oncol 18(27):2987–2997. 10.2217/fon-2022-0484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilton J, Cristea M, Postel-Vinay S et al (2022) BMS-986158, a small molecule inhibitor of the bromodomain and extraterminal domain proteins, in patients with selected advanced solid tumors: results from a phase 1/2a trial. Cancers (Basel) 14(17):4079. 10.3390/cancers14174079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aggarwal RR, Schweizer MT, Nanus DM et al (2020) A phase Ib/IIa study of the Pan-BET inhibitor ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 26(20):5338–5347. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallagher SJ, Mijatov B, Gunatilake D et al (2014) The epigenetic regulator I-BET151 induces BIM-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest of human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol 134(11):2795–2805. 10.1038/jid.2014.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu X, Dong X, Li G et al (2021) Brd4 modulates diet-induced obesity via PPARgamma-dependent Gdf3 expression in adipose tissue macrophages. JCI Insight 6(7):e143379. 10.1172/jci.insight.143379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lingohr MK, Dickson LM, McCuaig JF, Hugl SR, Twardzik DR, Rhodes CJ (2002) Activation of IRS-2-mediated signal transduction by IGF-1, but not TGF-alpha or EGF, augments pancreatic beta-cell proliferation. Diabetes 51(4):966–976. 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kolodziejski PA, Sassek M, Bien J et al (2020) FGF-1 modulates pancreatic beta-cell functions/metabolism: an in vitro study. Gen Comp Endocrinol 294:113498. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2020.113498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agudo J, Ayuso E, Jimenez V et al (2008) IGF-I mediates regeneration of endocrine pancreas by increasing beta cell replication through cell cycle protein modulation in mice. Diabetologia 51(10):1862–1872. 10.1007/s00125-008-1087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wan S, An Y, Fan W, Teng F, Jiang Z (2023) Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals the underlying molecular mechanism in high-fat diet-induced islet dysfunction. Biosci Rep 43(7):BSR20230501. 10.1042/BSR20230501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ai J, Duan J, Lv X et al (2010) Overexpression of FoxO1 causes proliferation of cultured pancreatic beta cells exposed to low nutrition. Biochemistry 49(1):218–225. 10.1021/bi901414g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gupta D, Leahy AA, Monga N, Peshavaria M, Jetton TL, Leahy JL (2013) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and its target genes are downstream effectors of FoxO1 protein in islet beta-cells: mechanism of beta-cell compensation and failure. J Biol Chem 288(35):25440–25449. 10.1074/jbc.M113.486852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang L, Matkar S, Xie G et al (2017) BRD4 inhibitor IBET upregulates p27kip/cip protein stability in neuroendocrine tumor cells. Cancer Biol Ther 18(4):229–236. 10.1080/15384047.2017.1294291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan Y, Wang L, Du Y et al (2018) Inhibition of BRD4 suppresses tumor growth in prostate cancer via the enhancement of FOXO1 expression. Int J Oncol 53(6):2503–2517. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X, Yong W, Lv J et al (2009) Inhibition of forkhead box O1 protects pancreatic beta-cells against dexamethasone-induced dysfunction. Endocrinology 150(9):4065–4073. 10.1210/en.2009-0343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song MY, Wang J, Ka SO, Bae EJ, Park BH (2016) Insulin secretion impairment in Sirt6 knockout pancreatic beta cells is mediated by suppression of the FoxO1-Pdx1-Glut2 pathway. Sci Rep 6:30321. 10.1038/srep30321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martinez SC, Cras-Meneur C, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Permutt MA (2006) Glucose regulates Foxo1 through insulin receptor signaling in the pancreatic islet beta-cell. Diabetes 55(6):1581–1591. 10.2337/db05-0678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Volcano plots of significant KEGG pathways listed in Fig. 3b can be found in the ESM. All other datasets are available from the corresponding author on request.