Abstract

It is uncertain how much life expectancy of the Chinese population would improve under current and greater policy targets on lifestyle-based risk factors for chronic diseases and mortality. Here we report a simulation of how improvements in four risk factors, namely smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and diet, could affect mortality. We show that in the ideal scenario, that is, all people who currently smoke quit smoking, excessive alcohol use was reduced to moderate intake, people under 65 increased moderate physical activity by one hour and those aged 65 and older increased by half an hour per day, and all participants ate 200 g more fresh fruits and 50 g more fish/seafood per day, life expectancy at age 30 would increase by 4.83 and 5.39 years for men and women, respectively. In a more moderate risk reduction scenario referred to as the practical scenario, where improvements in each lifestyle factor were approximately halved, the gains in life expectancy at age 30 could be half those of the ideal scenario. However, the possibility to realize these estimates in practise may be influenced by population-wide adherence to lifestyle recommendations.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Risk factors

It is uncertain how much life expectancy of the Chinese population would improve under current and greater policy targets on lifestyle-based risk factors for chronic diseases and mortality behaviours. Here we report a simulation of how improvements in four risk factors, namely smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and diet, could affect mortality. We show that in the ideal scenario, that is, all people who currently smokers quit smoking, excessive alcohol userswas reduced to moderate intake, people under 65 increased moderate physical activity by one hour and those aged 65 and older increased by half an hour per day, and all participants ate 200 g more fresh fruits and 50 g more fish/seafood per day, life expectancy at age 30 would increase by 4.83 and 5.39 years for men and women, respectively. In a more moderate risk reduction scenario referred to as the practical scenario, where improvements in each lifestyle factor were approximately halved, the gains in life expectancy at age 30 could be half those of the ideal scenario. However, the validity of these estimates in practise may be influenced by population-wide adherence to lifestyle recommendations. Our findings suggest that the current policy targets set by the Healthy China Initiative could be adjusted dynamically, and a greater increase in life expectancy would be achieved.

Introduction

Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, including smoking, excessive alcohol use, low physical activity, and poor dietary habits, could lead to almost all chronic diseases, like cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic respiratory disease1–3. These behaviors consequently increase the risk of premature death4 and contribute substantially to the overall disease burden. In 2021, about 16% of global disability-adjusted life years were attributed to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors5. The financial burden of chronic disease treatment, along with workforce loss due to decreased productivity and premature death, significantly impedes socio-economic progress.

In response, many countries have developed national initiatives to promote healthy lifestyles, such as the U.S. Healthy People 2030, Health Japan 21, and Healthier Singapore6–8. In 2016, China put forward “Healthy China 2030” as a national strategy, articulating development goals to improve the lifestyle and health of its population9. Specific targets were further defined in the “Healthy China Initiative 2019–2030”10. Despite considerable efforts to date, the extent to which population health indicators, such as life expectancy (LE), would improve if the lifestyle behavior targets were achieved remains uncertain.

Previous studies indicated that if the entire population refrained from smoking and alcohol consumption, engaged in sufficient physical activity, and consumed 300 g of fruit daily, the LE at birth for the Chinese population would increase by 2.04, 0.43, 0.43, and 1.73 years, respectively11–14. The method used in the above studies was the aggregated data approach, which indirectly attributes a fraction of deaths to the exposures of interest, and the association estimates between the exposures and cause-specific mortality used in the analysis came from other studies15. Specifically, the effect sizes of the association were from meta-analyses in which the study population was predominantly European and American, potentially overestimating the impact of lifestyle modifications on LE in the Chinese population. Furthermore, this method only assesses the independent effect of each factor, not their combined effects. In 2016, Canadian researchers proposed a more flexible method, called the “Multivariable Predictive Approach”, to address this limitation. The researchers found that the Canadians’ LE at age 20 would increase by 6 years if they were non-smokers, non-drinkers or moderate drinkers, physically active, and had healthy dietary habits16.

In this study, we used data from the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) study, which followed 0.5 million adults for 15 years, and the China Nutrition and Health Surveillance (CNHS) with nationally representative samples, to comprehensively analyze the impact of changes in multiple lifestyle factors and their combined effects on LE of the Chinese population. For each lifestyle factor, we investigated the impact of different levels of improvement to better understand how much LE could be improved if the targets set in current policies were met, as well as the maximum room for LE improvement if stronger measures were taken. The study shows that implementing stricter measures would lead to a more substantial increase in LE among the Chinese population.

Results

Characteristics of the study populations

The CKB model derivation cohort included 140,135 men and 201,678 women, with mean ages at baseline of 52.4 ± 10.9 and 51.0 ± 10.5 years, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The validation cohort shared similar characteristics.

The simulation analysis included 31,515 men and 36,049 women from the CNHS, with mean ages of 55.5 ± 12.5 and 54.5 ± 12.3 years, respectively. Current smoking was reported by 51.6% of men and 2.4% of women. Excessive alcohol use was reported by 11.9% of men and 0.4% of women. Men had a higher physical activity level than women (16.3 vs. 13.7 MET-h/d). Women consumed less red meat and fish/seafood than men, but consumed more fresh fruits.

5-year mortality prediction model developed in the CKB population

During a median follow-up of 12.1 years (6.0 million person-years), the CKB documented 31,956 deaths in men and 24,593 deaths in women. Deaths in the derivation cohort were 21,361 and 16,444 for men and women, respectively. The predictors included in the prediction model and their formation were the same for men and women, except for marital status, which was only included in the men’s prediction model (Table 1). The correlation matrix of all predictor variables demonstrated weak correlations among variables, indicating minimal impact of collinearity on parameter estimation (Supplementary Fig. 1). We assessed the proportional hazards assumption using log-log survival plots for categorical variables and Schoenfeld residual tests for continuous variables, and no significant violation was observed. Further details of the included variables were listed in Supplementary Table 2, and the final model parameters were shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. In sensitivity analysis, using the whole population of each sex to repeat the development process, the same set of predictors was selected, and their coefficient estimates were consistent with those obtained from the derivation cohort (Supplementary Table 5). In progressively adjusted models, the effect sizes of lifestyle factors and other exposures remained almost consistent, except that only the effects of smoking and alcohol use were slightly attenuated in the fully adjusted model for men (Supplementary Table 6). This supported that the prediction model has appropriate specification, and the effect size estimates were robust.

Table 1.

HRs (95% CIs) of all-cause mortality for all predictor variables in the derivation dataset of China Kadoorie Biobank study for men and women

| Men (n = 140,135) | Women (n = 201,678) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | Deaths/PYs (/1000) | HRs (95% CIs) | Deaths | Deaths/PYs (/1000) | HRs (95% CIs) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Linear | -- | -- | 1.08 (1.08–1.08) | -- | -- | 1.08 (1.07–1.08) |

| Squared | -- | -- | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | -- | -- | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| Highest education | ||||||

| No formal school | 3911 | 29.2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 7594 | 12.7 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Primary school | 9489 | 18.0 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | 5468 | 7.3 | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) |

| Middle school | 4718 | 8.9 | 0.79 (0.75–0.83) | 2079 | 3.4 | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) |

| High school | 2173 | 7.6 | 0.67 (0.63–0.71) | 976 | 3.0 | 0.74 (0.69–0.80) |

| College/university | 1070 | 8.4 | 0.59 (0.54–0.63) | 327 | 3.0 | 0.69 (0.61–0.78) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 18,285 | 12.2 | 1.00 (Reference) | -- | -- | -- |

| Widowed | 2195 | 38.0 | 1.19 (1.14–1.25) | -- | -- | -- |

| Separated/divorced | 392 | 15.7 | 1.65 (1.50–1.83) | -- | -- | -- |

| Never married | 489 | 22.4 | 1.80 (1.64–1.97) | -- | -- | -- |

| Smoking* | ||||||

| Never | 4649 | 11.2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 14,984 | 6.4 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Former | 1541 | 14.5 | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 183 | 20.4 | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) |

| Current (number of cigarettes or equivalents per day) | ||||||

| <20 | 7469 | 15.5 | 1.24 (1.19–1.29) | 1063 | 19.9 | 1.31 (1.22–1.40) |

| ≥20 | 7702 | 12.7 | 1.34 (1.29–1.39) | 214 | 19.9 | 1.53 (1.34–1.76) |

| Alcohol intake† | ||||||

| Less than daily | 13,697 | 12.0 | 1.00 (Reference) | 15,944 | 6.8 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Current daily (g of pure alcohol per day) | ||||||

| 1–29 | 1116 | 14.9 | 1.02 (0.95–1.08) | 134 | 9.6 | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) |

| 30–59 | 1414 | 12.8 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 57 | 11.0 | 1.01 (0.77–1.31) |

| ≥60 | 5134 | 18.3 | 1.25 (1.21–1.30) | 309 | 13.2 | 1.14 (1.02–1.28) |

| Ln(physical activity level [MET-h/day]) | -- | -- | 0.91 (0.90–0.92) | -- | -- | 0.82 (0.81–0.84) |

| Food consumption (per 10 g/d) | ||||||

| Fresh fruits | -- | -- | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | -- | -- | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

| Red meat | -- | -- | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | -- | -- | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) |

| Fish/seafood | -- | -- | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | -- | -- | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 2122 | 32.4 | 1.55 (1.48–1.62) | 1449 | 14.9 | 1.53 (1.44–1.62) |

| 18.5–23.9 | 11,867 | 13.7 | 1.00 (Reference) | 7632 | 6.3 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 24.0–27.9 | 5757 | 10.8 | 0.85 (0.82–0.88) | 5071 | 6.3 | 0.89 (0.86–0.93) |

| ≥28 | 1615 | 11.2 | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 2292 | 8.1 | 0.93 (0.89–0.98) |

| Ln(systolic blood pressure [mmHg]) | -- | -- | 3.41 (3.12–3.74) | -- | -- | 3.73 (3.37–4.12) |

| Resting heart rate (beats/minute) | -- | -- | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | -- | -- | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Excellent/good | 7824 | 9.7 | 1.00 (Reference) | 4910 | 4.7 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Fair | 9746 | 14.6 | 1.17 (1.13–1.21) | 7735 | 7.1 | 1.17 (1.12–1.21) |

| Poor | 3791 | 28.9 | 1.75 (1.67–1.82) | 3799 | 14.4 | 1.64 (1.56–1.71) |

| Stroke at baseline | ||||||

| No | 19,849 | 12.6 | 1.00 (Reference) | 15,645 | 6.6 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 1512 | 48.9 | 1.59 (1.50–1.68) | 799 | 29.1 | 1.60 (1.49–1.72) |

| Cancer at baseline | ||||||

| No | 21,071 | 13.2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 16,183 | 6.8 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 290 | 51.2 | 2.10 (1.87–2.37) | 261 | 23.0 | 2.04 (1.80–2.31) |

| COPD at baseline | ||||||

| No | 17,194 | 11.6 | 1.00 (Reference) | 14,115 | 6.3 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 4167 | 31.9 | 1.34 (1.29–1.39) | 2329 | 16.3 | 1.38 (1.32–1.45) |

| Diabetes at baseline | ||||||

| No | 19,074 | 12.5 | 1.00 (Reference) | 13,730 | 6.1 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 2287 | 27.7 | 1.51 (1.44–1.58) | 2714 | 19.8 | 1.79 (1.71–1.87) |

| Baseline survival estimated at 5 years‡ | 0.984 | 0.992 | ||||

All predictor variables were included simultaneously in the model. Continuous predictor variables were centered as follows: age at 50 years, physical activity level at 20 MET-h/d, daily fresh fruits intake at 80 g, daily red meat intake at 50 g, daily fish/seafood intake at 20 g, systolic blood pressure at 120 mmHg, and resting heart rate at 80 beats/min.

PYs indicates person-years, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, MET-h/d metabolic equivalent task hours per day, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, -- not applicable.

*Former smoking status was defined as having quit smoking for reasons other than illness. Participants who had quit smoking due to illness were defined as current smoking status.

†Less than daily group included both never-regular drinkers and current weekly drinkers. Former alcohol drinkers were included in the heavy drinking category (≥60 g of pure alcohol per day).

‡Cox models were stratified by 10 regions. Baseline survival at 5 years (S0[5]) was calculated by pooling the S0(5) across regions weighted by the number of deaths by 5 years.

The prediction models for both men and women demonstrated good discrimination, with the overall area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) (95% confidence interval [CI]) of 0.800 (0.792–0.807) for men and 0.808 (0.798–0.817) for women in the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2). The calibration plots showed a close approximation of predicted and observed mortality risk by risk decile. However, the models modestly overestimated the death risk in high-risk groups. The calibration performance remained consistent across subgroups defined by educational level and marital status (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Age-specific prevalence of lifestyle factors in the CNHS population

Across all age groups of the CNHS population, men had a higher prevalence of current smoking and excessive alcohol use than women (Supplementary Fig. 5). Men’s smoking prevalence was highest in the 30–59 age group (over 50%), with a gradual decrease in the 60-and-over age group. Excessive alcohol use was highest (17.9%) among men aged 50–69. For both men and women, the 40–49 age group had the highest level of total physical activity, which gradually declined with age. In terms of dietary habits, women had lower intake than men for almost all foods and age groups, with the exception of fresh fruits, which women consumed more than men under the age of 70. Intake of all the food groups declined as men and women aged.

Impact of changes in lifestyle prevalence on LE for the whole population

In the base scenario, when the prevalence of all lifestyle factors of interest remained at the above level, the estimated period LE at age 30 (95% CI) was 45.46 (44.85–46.27) years for men and 47.00 (46.23–47.86) years for women (Table 2). When all lifestyle factors in the population were set to the ideal scenario, there was a significant reduction in the 5-year all-cause mortality risk for both men and women (Fig. 1), leading to an increase in LE for the whole population.

Table 2.

Life expectancy at 30 years and the gained life years under ideal and practical scenarios for lifestyle factor change in men and women

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy (95% CI), 30 y | Gained life years (95% CI) | Life expectancy (95% CI), 30 y | Gained life years (95% CI) | |

| Base scenario* | 45.46 (44.85-46.27) | -- | 47.00 (46.23-47.86) | -- |

| Simulated scenario | ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Ideal scenario | 46.13 (45.51–47.00) | 0.68 (0.44–0.91) | 47.05 (46.30–47.90) | 0.05 (0.00–0.09) |

| Practical scenario | 45.86 (45.27–46.70) | 0.40 (0.26–0.54) | -- | -- |

| Alcohol intake | ||||

| Ideal scenario | 45.61 (44.98–46.44) | 0.15 (0.08–0.23) | 47.01 (46.23–47.87) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) |

| Practical scenario | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Ideal scenario | 46.18 (45.58–46.95) | 0.72 (0.62–0.84) | 48.47 (47.78–49.23) | 1.47 (1.30–1.67) |

| Practical scenario | 45.99 (45.38–46.77) | 0.53 (0.46–0.62) | 48.09 (47.38–48.88) | 1.09 (0.96–1.25) |

| Dietary habits | ||||

| Ideal scenario | 49.08 (47.86–50.09) | 3.62 (2.72–4.67) | 51.27 (50.50–52.03) | 4.26 (3.55–5.08) |

| Practical scenario | 47.22 (46.31–47.95) | 1.76 (1.29–2.33) | 49.11 (48.38–49.73) | 2.11 (1.70–2.59) |

| All factors combined† | ||||

| Ideal scenario | 50.29 (49.26–51.18) | 4.83 (4.01–5.82) | 52.40 (51.77–53.00) | 5.39 (4.70–6.18) |

| Practical scenario | 48.07 (47.28–48.78) | 2.61 (2.15–3.17) | 50.10 (49.46–50.66) | 3.10 (2.67–3.59) |

The definitions of ideal and practical scenarios for each lifestyle factor are described in Table 3.

CI indicates confidence interval, -- not applicable.

*The exposure patterns for all lifestyle factors remained unchanged.

†All lifestyle factors were set to the ideal or practical scenarios.

Fig. 1. Distribution of 5-year mortality risk in the base and simulated scenarios for men and women.

In the base scenario (red), exposure patterns for all lifestyle factors remained unchanged. In the simulated scenario (blue), all factors were set to the ideal scenario described in Table 3. The vertical lines indicate the mean 5-year mortality risk for each scenario. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Reductions in the prevalence of current smoking and excessive alcohol use had an impact on the LE for men, but not for women (Table 2). When all males who currently smoke were assumed to have quit (ideal scenario), LE at age 30 would increase by 0.68 (95% CI: 0.44–0.91) years; when it was reduced to 20% (practical scenario), LE at age 30 would increase by 0.40 (0.26–0.54) years. In sensitivity analysis, when the whole population was assumed to never smoke, LE at age 30 would increase by 1.02 (0.88–1.17) years in men (Supplementary Table 7). If the tobacco control goal set out in Healthy China 2030, which is to reduce smoking prevalence in the Chinese population to 20%, was achieved only by reducing smoking prevalence in men, men’s LE at age 30 would increase by 0.14 (0.09–0.19) years.

In the ideal scenario for alcohol consumption, assuming that all people with excessive alcohol use were moderate drinkers, men’s LE at age 30 would increase by 0.15 (0.08–0.23) years (Table 2). When people with excessive alcohol use were assumed to be non-daily drinkers, LE at age 30 would increase by 0.17 (0.13–0.20) years (Supplementary Table 7).

Increases in total physical activity had a greater impact on LE in women than men (Table 2). In the ideal scenario, when participants under 65 and 65 or older increased their physical activity by 4 MET-h/d and 2 MET-h/d, respectively, LE at age 30 would increase by 0.72 (0.62–0.84) years for men and 1.47 (1.30–1.67) years for women. When the increased physical activity levels were half of the above (practical scenario), the increase in LE was slightly lower. In contrast, following the goal of Healthy China 2030, assuming that the proportion of individuals engaging in regular physical activity reached 40% in men and women, LE at age 30 would increase by only 0.17 (0.15–0.20) years for men and 0.38 (0.34–0.43) years for women (Supplementary Table 7).

Improved dietary habits had a greater impact on LE than the other lifestyle factors. In the ideal scenario, assuming that all participants ate 200 g more fresh fruits and 50 g more fish/seafood per day, LE at age 30 would increase by 3.62 (2.72–4.67) and 4.26 (3.55–5.08) years for men and women, respectively. When all participants were assumed to eat 100 g more fresh fruits and 20 g more fish/seafood per day (practical scenario), the gains in LE at age 30 were 1.76 (1.29–2.33) years for men and 2.11 (1.70–2.59) years for women.

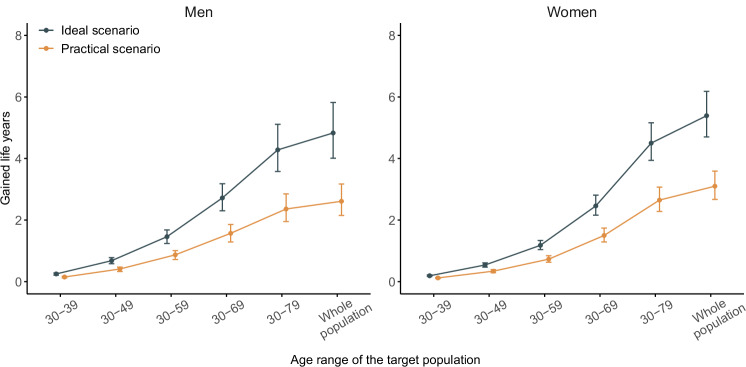

When all lifestyle factors were set to the ideal scenario, LE at age 30 (95% CI) would be 50.29 (49.26–51.18) years for men and 52.40 (51.77–53.00) years for women, an increase of 4.83 (4.01–5.82) and 5.39 (4.70–6.18) years over the base scenario, respectively (Table 2). In the practical scenario, the gain in LE at age 30 was 2.61 (2.15–3.17) years for men and 3.10 (2.67–3.59) years for women. The gain in LE increased with the age range of the target population for lifestyle interventions (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 2. Gained life years at age 30 for men and women from adopting combined low-risk lifestyle habits, with the target population having different age ranges.

The definitions of ideal (dark blue) and practical (dark yellow) scenarios for each lifestyle factor are described in Table 3. Results are derived from 31,515 men and 36,049 women with complete survey data on lifestyle factors in the China Nutrition and Health Surveillance (CNHS) study. Data are presented as point estimates of gained life years (centers of error bars) and the corresponding 95% confidence limits (error bars). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The current study found that population-wide lifestyle modifications could significantly increase LE in the Chinese population. When all lifestyle factors were set to the ideal scenario, that is, all people who currently smoke quit smoking, excessive alcohol use were reduced to moderate drink, people under 65 and those aged 65 and older increased their physical activity level by 1 h and half an hour per day of moderate-intensity physical activity, and all participants ate 200 g more fresh fruits and 50 g more fish/seafood per day, LE at age 30 would increase by 4.83 and 5.39 years for men and women, respectively. In the practical scenario, where improvements in each of the lifestyle factors were approximately halved, the gains in LE at age 30 for both men and women could be half of those in the ideal scenario. However, the validity of these estimates may be influenced by population-wide adherence to lifestyle recommendations.

The traditional aggregated data approach uses the association estimates between lifestyle and disease-specific mortality from other studies and then aggregates that information across all specific causes to calculate the total attributable deaths due to unhealthy lifestyles. The potential intrinsic link between different diseases may lead to an overestimation of total attributable deaths. Also, this approach cannot assess the combined impact of changing several interrelated lifestyle factors simultaneously. In this study, we adopted a new analytic strategy to address the limitations mentioned above15. We examined all-cause mortality and did not need to consider the association between lifestyles and cause-specific mortality. Furthermore, individual-level analysis is more flexible, allowing us to assess the impact of simultaneous changes in multiple factors on LE for the whole population.

Previous studies using the traditional approach revealed that nonsmoking and nondrinking, which approximated the ideal scenarios set in this study, resulted in 2.04- and 0.43-year gains in LE for the Chinese population, respectively11,12, which were greater than our estimates. In addition to the reason mentioned above, this difference could be because the association estimates between lifestyle and death were primarily from European and American populations, which were higher than those from Asian populations and the present study population1, resulting in an overestimation of the health benefits of lifestyle interventions in the Chinese population.

The current analytic strategy relied on all-cause mortality prediction models applicable to the general Chinese population. Only two previous studies based on general populations in Taiwan constructed all-cause mortality prediction models, with sample sizes of 2221 and 911 participants, respectively17,18. Small sample sizes limited their statistical power in modeling. In the current study, we used a large sample of the CKB population to develop 5-year sex-specific all-cause mortality risk prediction models. The dimensions of the included predictors were generally consistent with the model developed for the Canadian population described above16. The prediction models for both men and women had good discrimination, with AUCs of 0.8 or above. Nevertheless, the predicted risk was higher than the observed values in the high-risk group, especially in women. This also occurred in prediction models constructed based on other populations19,20. However, a slight overestimation of mortality risk in older age groups with higher mortality risk had little impact on the subsequent estimation of LE for the whole population21.

We used period LE in this study, which was calculated based on the predicted mortality risk derived from cross-sectional data. This metric measures the average number of years a synthetic cohort is expected to live if they experienced the current mortality pattern22. Traditional mortality burden studies commonly used cause-deleted period life tables to assess the impact of prevalent diseases or risk factors, such as unhealthy lifestyle examined in this study, on population lifespan23. These studies serve as a priority-setting reference for public health decision-making. However, cohort LE, an alternative measure of lifespan, is the actual average lifespan of a historic birth cohort. It only summarizes past mortality experiences and is often used to evaluate the health impact of historical events.

China’s current tobacco control target is to achieve a smoking prevalence of less than 20% among people aged 15 and older by 20309. Since the smoking prevalence was significantly higher in men than in women (51.6% in men and 2.4% in women in CNHS 2015), we assumed that this target could be achieved solely by reducing smoking prevalence in men to 40.1%, resulting in a maximum increase in LE at age 30 of 0.14 years. In the practical scenario, reducing male smoking prevalence to 20%, when the overall population prevalence was 10.6%, would result in a 0.4-year increase in LE at age 30. It should be noted that the above scenarios require people who currently smoke to quit smoking. Quitters continue to have a higher mortality risk than non-smokers for a long period. As a result, the improvement in LE under these scenarios remained limited. If stricter tobacco control policies and measures were implemented to prevent adolescents from taking their first puff, which is also known as the “tobacco-free generation” strategy24, Chinese men’s LE at age 30 would improve by 1.02 years.

In our study, reducing the prevalence of excessive drinking had a small impact on the LE. This is primarily due to a low prevalence of excessive alcohol use (11.9% in men and 0.4% in women in CNHS 2015) in comparison to other unhealthy lifestyle factors in the Chinese population. Nevertheless, as compared to other countries, China has a relatively high prevalence of excessive drinkers, especially among men. In contrast, only 5% of men in the U.S. drank excessively in 201825. China makes less effort to control alcohol availability and marketing26. In recent years, cultural and social factors have contributed to an increase in the drinking prevalence of the Chinese population27. Therefore, the future burden that alcohol consumption may cause must not be ignored.

According to the targets set in the national fitness plan, when the proportion of the population engaging in regular physical activity reached 40% (10.8% in men and 11.3% in women in CNHS 2015), LE at age 30 would increase by 0.17 and 0.38 years for men and women, respectively. In the present study, we set up simulated scenarios following a population-wide strategy. If the overall population’s physical activity level shifted towards a higher level, the improvement in LE would be even greater. In an ideal scenario, those under 65 years of age would engage in one more hour of moderate-intensity physical activity per day, while those aged 65 and above would engage in half an hour or more, increasing LE at age 30 by 0.72 and 1.47 years for men and women, respectively.

China’s current diet improvement target is for a minimum combined intake of 500 g of vegetables and fruits per day9. However, vegetables and fruits have distinct nutritional values and cannot substitute for one another, and the Chinese population consumes more vegetables than fruits28. Therefore, we set a specific target for fruit intake while also considering increases in seafood consumption. Compared to other lifestyle factors, modifying dietary habits by increasing intake of fresh fruits and seafood has the greatest impact on overall LE. The current consumption levels of both fresh fruits and seafood in the Chinese population are much lower than the recommendations in dietary guidelines, which could be the primary reason for this.

In this study, the life year gains from lifestyle improvements were less pronounced than in the Canadian population, where comparable lifestyle modifications were associated with a 6-year increase in LE at age 20. This discrepancy may arise from the smaller effect size of healthy lifestyle factors on all-cause mortality, which are inherently relative and depend on the underlying baseline risk. Apart from unhealthy lifestyles, the Chinese population faces more other adverse factors, such as unhealthy environmental exposures from their homes, workplaces, and surroundings29, which collectively contribute to a higher baseline mortality risk. Thus, the relative impact of lifestyle alone might be slightly diminished.

Several strengths characterize this study. First, this study applied a newly developed method to evaluate the impact of simultaneous improvements in multiple lifestyle factors on the overall population’s LE, generating research evidence specific to the Chinese population. Second, the CKB study has a large sample size, a long follow-up period, and a significant number of mortality events, allowing for sufficient statistical power in the development of the mortality risk prediction model and more reliable parameter estimation. Third, we used nationally representative data from the CNHS survey for simulation analysis, improving the findings’ applicability to the Chinese population.

Limitations inherent in population surveys may lead to estimation bias. In CKB, the variables used to construct the prediction model were predominantly self-reported and could be subject to non-differential misclassification bias, which may lead to underestimation of the effect sizes of the predictors. However, in a subsample of 1300 participants who completed the same questionnaire twice at a median interval of 1.4 years, we observed that the measurement errors for the lifestyle factors were within acceptable limits, except for fresh fruit consumption, which may be due to the seasonal availability of fresh fruits30,31. Besides, we used baseline predictor information and did not consider the possible changes during follow-up. This was primarily because repeated data collection is challenging in large-scale population survey, and most disease burden studies do not consider time-varying variables either. However, our earlier research utilizing resurvey data from a subset of the CKB population revealed that most participants maintained relatively consistent lifestyle patterns over long periods32. Lifestyle factors in CNHS were self-reported as well, which may be more likely to overestimate the proportion of individuals with healthy lifestyles. This optimistic estimate of lifestyle may result in underestimation of the impact of lifestyle modifications on LE for the whole population33.

Some other methodological limitations should also be noted. First, we only considered stochastic error when calculating CIs of LE, while neglecting other sources of error like sampling error, which may lead to underestimation of uncertainty. Second, the present analytic strategy was counterfactual, without accounting for the time-lag effect of lifestyle changes on mortality. However, given the natural development trend of LE in the Chinese population, if the simulated scenarios proposed in this study came true34, the gains in LE could be even higher.

In conclusion, this study reinforces the evidence that promoting healthy lifestyles can improve the LE of the whole Chinese population. To achieve a greater increase in LE, the current targets and indicators set by the Healthy China Initiative could be adjusted dynamically as necessary.

Methods

We used the same analysis strategy as the Canadian study16, and utilized two data sources: the CKB and CNHS (2015) (Supplementary Fig. 7). The CKB was used to develop a prediction model for the 5-year mortality risk that focused on the hazard of death related to lifestyle factors while accounting for other potential risk factors. The Ethical Review Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Beijing, China), the Peking University Health Science Center (Beijing, China), and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee, University of Oxford (UK) approved the study. The CNHS was used to apply the above prediction model to estimate the period-based LE of the whole population under various scenarios and was approved by the Ethical Committee of China CDC. Due to sex differences in LE, we performed separate analyses for men and women.

Data for model development and validation

The CKB is a nationwide population-based prospective cohort study including over 0.5 million adults. The study design has been detailed elsewhere35. In brief, 512,723 participants aged 30–79 were enrolled during 2004–2008 from five urban and five rural regions, covering a wide range of risk exposures, disease patterns, and levels of economic development. Two periodic resurveys were conducted on about 5% of randomly chosen surviving participants in 2008 and 2013–2014. All participants signed informed consent forms.

All participants were followed up for mortality immediately after baseline enrollment by linkage to the National Disease Surveillance Points (DSP) system, supplemented with active follow-up. The loss to follow-up was <1% before censoring on December 31, 2018.

Data for simulation analysis

The CNHS (2015–2017) was the latest round of cross-sectional surveys for Chinese national nutrition and chronic disease surveillance, with nationally representative samples from 302 survey sites across 31 provincial-level administrative divisions in the mainland of China. The adult survey was completed in 2015. Participants were selected using a stratified multistage cluster sampling scheme, as previously reported36. All participants had completed written informed consent forms.

Candidate predictors

In both the CNHS and CKB baseline surveys, all participants completed a questionnaire and had physical measurements taken. Candidate predictors were identified using the following rules: (1) ever included in mortality risk prediction models in previous studies37–41; (2) available in the CKB and CNHS surveys. We eventually pre-specified 22 candidate predictors, including age, education level, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, total physical activity level, dietary intake (fresh vegetables, fresh fruits, red meat, and fish/seafood), sleep duration, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, resting heart rate, self-rated health status, and personal medical histories (coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], asthma, and diabetes). We depicted in the Supplementary Material about the assessment of candidate predictors.

Definition of simulated scenarios

Referring to the action goals set in Healthy China 2030 and the recommended intakes of various foods in the Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents9,42, we predefined two simulated scenarios for each lifestyle factor: ideal and practical scenarios, with the goals set in the practical scenario being more achievable (Table 3). We also considered an alternative scenario for smoking, in which the whole population is assumed to never smoke. In addition, based on Healthy China 2030 which aims to reduce smoking prevalence in the whole population to 20%, we further assumed that this would be achieved only by reducing smoking prevalence in men from 51.6% to 40.1%. As a result, we recoded 11.5% of the males who currently smoke as quitters.

Table 3.

Definitions of the ideal and practical scenarios for each lifestyle factor

| Ideal scenario | Practical scenario | Alternative scenario | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | It is assumed that all people who currently smoke in the target age group will quit smoking. | It is assumed that the prevalence of current smoking in the target age group will reduce to 20% (only in men). | It is assumed that the whole population never smoke. |

| Alcohol intake* | It is assumed that all people with excessive alcohol use in the target age group will become moderate drinkers. | -- | It is assumed that all people with excessive alcohol use in the whole population will become non-daily drinkers. |

| Physical activity | It is assumed that all individuals in the target age group will increase their physical activity by 4 MET-h/d for those under 65 and 2 MET-h/d for those aged 65 or older. | It is assumed that all individuals in the target age group will increase their physical activity by 2 MET-h/d for those under 65 and 1 MET-h/d for those aged 65 or older. | -- |

| Dietary habits |

It is assumed that all individuals in the target age group will (1) eat 200 g more fresh fruits per day (2) eat 50 g more fish/seafood per day |

It is assumed that all individuals in the target age group will (1) eat 100 g more fresh fruits per day (2) eat 20 g more fish/seafood per day |

-- |

MET-h/d indicates metabolic equivalent task hours per day.

*Excessive alcohol use was defined as consuming ≥30 g of pure alcohol per day, and moderate alcohol use was defined as consuming <30 g.

Due to the low prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption in the CNHS population (men: 11.9%; women: 0.4%), we did not set a practical scenario for this factor. However, we considered an alternative scenario for alcohol consumption, assuming that all people with excessive alcohol use were non-daily drinkers.

Total physical activity level was modeled as a continuous measure, with 1 MET-h/d representing an increase in moderate-intensity physical activity of about 15 min per day43. In addition to the ideal and practical scenarios, we also referred to the goal of Healthy China 2030, which is to increase the proportion of individuals who engage in regular physical activity to 40%. Regular physical activity is defined as engaging in physical activity of moderate intensity or higher ≥3 times per week, each time lasting ≥30 min. The proportions of men and women in CNHS achieving this physical activity level were 2% and 1.2%, respectively, so we recoded an additional 38% of men and 38.8% of women who did not achieve this level of physical activity as having achieved it.

For dietary habits, the target values in the ideal scenario are the amounts of fresh fruits and fish/seafood that the population needs to consume to reach the upper limits of the dietary guideline recommendations. In contrast, those in the practical scenario are the amounts required to reach the lower limits of the recommendations. We did not simulate changes in red meat intake because the CNHS population already consumed more than the recommended level. The combined impact of changes in these lifestyle factors was estimated by setting all lifestyle factors to ideal or practical scenarios.

Statistical analysis

Development and validation of the prediction model

Two participants in the CKB were excluded due to missing BMI data, leaving 210,203 men and 302,518 women in the current study. We developed separate models for men and women. To reduce overfitting44, the models were fitted to a random two-thirds sample (derivation cohort: men 140,135 and women 201,678) and evaluated in the remaining one-third (validation cohort: men 70,068 and women 100,840). To improve prediction performance, we used the intake amount data from the second resurvey as a proxy measure of mean consumption for each frequency category at baseline45. Details on the calculations and results have been presented in the Supplementary Material and Supplementary Tables 8 and 9.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to develop models stratified by ten study regions, with follow-up time as the time scale. Participants were considered at risk from the baseline enrollment until the date of death, loss to follow-up, or December 31, 2018, whichever was earlier. We used backward elimination (P < 0.05 to retain) to select predictors. Due to the large sample size, most predictors were statistically significantly associated with mortality risk but only modestly improved the model’s predictive accuracy. We, therefore, subjected all remaining predictors to further selection with the Bayesian information criteria (BIC). If the BIC index decreased when the variable was removed, it was excluded from the model46. We used forward and bidirectional selection techniques rather than backward elimination to test the model’s stability. Two strategies selected the same set of predictors.

We used restricted cubic splines to test possible non-linear relationships between continuous variables and mortality risk. If nonlinearity was detected, the variables were transformed using the natural logarithm or converted to categorical variables. The formation was chosen when the model achieved the smallest BIC. All continuous variables were mean-centered to control for multicollinearity and provide a more straightforward interpretation of the regression estimates. Linear and squared terms of age were included to fit the non-linear increase in death hazard in older ages47,48. All two-way interactions were considered, but none significantly improved model performance. Finally, 17 and 16 predictors were kept in the models for men and women, respectively, both including six lifestyle factors, namely smoking status, alcohol consumption, total physical activity level, and daily intake amount of fresh fruits, red meat, and fish/seafood. Baseline survival at 5 years (S0[5]) was estimated by pooling the S0(5) across regions and weighting it by the number of deaths by 5 years49. Briefly, the 5-year all-cause mortality risk for an individual with risk factor X is:

where is the absolute risk of mortality in 5 years. S0(5) is the baseline survival probability at 5 years, and V equals to , where Xi is the value of predictor i, and is the beta coefficient for predictor i.

In the validation cohort, discrimination performance was assessed using the AUC, also known as the c-index. Calibration performance was graphically assessed by comparing the mean predicted risks over 5 years to the observed risks across deciles of predicted risks. The observed risks were obtained using Kaplan–Meier analyses. We also repeated the model development process using the whole population rather than the derivation cohort to test the model’s stability and parameter accuracy. We further examined whether the lifestyle effects were mediated by other variables by comparing three progressively adjusted models: (1) age and lifestyle factors only; (2) adding sociodemographic factors, including education level and marital status; (3) further adjusting for health indicators comprising self-rated health, baseline stroke, cancer, COPD, diabetes, BMI, systolic blood pressure, and resting heart rate.

Simulation of the impact of changes in lifestyle prevalence on LE for the whole population

The constructed model was applied to the CNHS population for simulation analysis. Participants were excluded if: (1) they could not be weighted due to lack of address information (n = 62); (2) they were younger than 30 years of age (n = 7289; in accordance with the CKB population used for model development); (3) they had missing data on the predictors (n = 3605); (4) they had implausible food intakes (n = 2230; fresh fruits >600 g/d, red meat >400 g/d, fish/seafood>200 g/d; the cut-off values were chosen based on the upper 99th percentile value). After these exclusions, 31,515 men and 36,049 women remained in the analysis.

With reference to the Canadian study cited above, we assessed the impact of changes in lifestyle prevalence using a cause-deleted period life table approach16,50. Unlike a typical period life table beginning with age- and sex-specific mortality rates, which are then converted to age- and sex-specific mortality risk, we constructed sex-specific 5-year abridged period life tables (30 to 85 years) using weighted mortality risk derived from the prediction model. When the prevalence of all lifestyle factors of interest remained at the level of the CNHS population, the obtained LE estimates were designated as the LE under “base scenario”. The LE under each simulated scenario was calculated using the same method and then compared to the base scenario to estimate the impact of lifestyle intervention on the whole population.

The CIs of LE were estimated using parametric bootstrapping with 500 runs, combining the stochastic error from the model parameters and the exposure variablity in the CNHS population.

We also demonstrated how lifestyle changes in specific age groups affect the LE of the whole population. Taking smoking as an example, we first used the 30–39 age group as the target population for tobacco control, then changed a certain proportion of individuals from a current to a former smoking status so that the prevalence of current smoking in this age group achieved the simulated scenario. Next, we gradually expanded the age range of the target population by 10 years (30–49, 30–59, 30–69, 30–79, and the whole population) and repeated the calculation of LE. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 15.0, StataCorp), and graphs were plotted using R version 4.0.3.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

The most important acknowledgment is to the participants in the study and the members of the survey teams in each of the 10 regional centers, as well as to the project development and management teams based at Beijing, Oxford and the 10 regional centers. This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82388102, LL) and Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0510101, 2023ZD0510100, JL). The CKB baseline survey and the first re-survey were supported by the Kadoorie Charitable Foundation in Hong Kong. The long-term follow-up has been supported by Wellcome grants to Oxford University (212946/Z/18/Z, 202922/Z/16/Z, 104085/Z/14/Z, 088158/Z/09/Z) and grants (2016YFC0900500) from the National Key R&D Program of China, National Natural Science Foundation of China (82192900, 81390540, 91846303, 81941018), and Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2011BAI09B01).

Author contributions

Q.S. and L.Z. are joint first authors. J.L. and L.L. conceived and designed the study, contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript for valuable intellectual content. L.L., Z.C., and J.C.: as the members of the CKB steering committee, designed and supervised the conduct of the whole study, obtained funding, and together with C.Y., D.S., Y.P., P.P., L.Y., Y.C., H.D., R.D., and M.B., acquired the CKB data. L.Z. and D.Y. designed and supervised the conduct of the CNHS. Q.S., L.Z., Y.Y., and Y.D. accessed, verified and analyzed the data. Q.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors had access to the data and have read and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. J.L., L.L., and D.Y. are the guarantors.

Data availability

CKB data are available to all bona fide researchers. Details of how to access and details of the data release schedule are available from www.ckbiobank.org/site/Data+Access. Researchers who are interested in obtaining the raw individual participant data related to this paper can contact pdc@kscdc.net. Please note that access will be granted after an evaluation of accordance with Chinese legislation. We anticipate that the data will become available within 8 weeks after requested access. As stated in the access policy, the CKB study group must maintain the integrity of the database for future use and regulate data access to comply with prior conditions agreed with the Chinese government. All approved users are required to sign a data use agreement that outlines specific restrictions to ensure data security and regulatory compliance. The raw data of the CNHS study are not publicly available due to data privacy regulations. Researchers may contact the corresponding author Dongmei Yu (yudm@ninh.chinacdc.cn) to request access to the summary data by providing methodologically sound scientific proposals. Access will be granted within approximately 8 weeks. A data use agreement must be signed before approval which stipulates that the data is allocated only for non-commercial research purposes. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Analysis code for this study is available at https://github.com/qiufen-code/lifestyle-simulation-study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qiufen Sun, Liyun Zhao.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

A full list of members and their affiliations appears in the Supplementary Information.

Contributor Information

Dongmei Yu, Email: yudm@ninh.chinacdc.cn.

Liming Li, Email: lmlee@vip.163.com.

Jun Lv, Email: lvjun@bjmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-64824-x.

References

- 1.Zhang, Y. B. et al. Combined lifestyle factors, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Epidemiol. Community Health75, 92–99 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin, G. et al. Genetic risk, incident gastric cancer, and healthy lifestyle: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol.21, 1378–1386 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan, K. H. et al. Tobacco smoking and risks of more than 470 diseases in China: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health7, e1014–e1026 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, K. et al. Healthy lifestyle for prevention of premature death among users and nonusers of common preventive medications: a prospective study in 2 US cohorts. J. Am. Heart Assoc.9, e016692 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brauer, M. et al. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet403, 2162–2203 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinman D. V. Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2030. In Proc. APHA 2017 Annual Meeting & Expo (Nov 4–Nov 8);2017: American Public Health Association (2017).

- 7.Nomura, S., Sakamoto, H., Ghaznavi, C. & Inoue, M. Toward a third term of Health Japan 21 - implications from the rise in non-communicable disease burden and highly preventable risk factors. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac.21, 100377 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foo, C. et al. Healthier SG: Singapore’s multi-year strategy to transform primary healthcare. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac.37, 100861 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Healthy China 2030. 2016.

- 10.State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Healthy China Action Plan (2019–2030). 2019.

- 11.Jiang, Y. Y. et al. [Deaths attributable to alcohol use and its impact on life expectancy in China, 2013]. Zhonghua liu xing bing. xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi39, 27–31 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, Y. N. et al. [Death and impact of life expectancy attributable to smoking in China, 2013]. Zhonghua liu xing bing. xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi38, 1005–1010 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, J. M. et al. [Effects of insufficient physical activity on motality and life expectancy in adult aged 25 and above among Chinese population]. Zhonghua liu xing bing. xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi38, 1033–1037 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi, J. L. et al. [Mortality attributable to inadequate intake of fruits among population aged 25 and above in China, 2013]. Zhonghua liu xing bing. xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi38, 1038–1042 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim, S. S. et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet380, 2224–2260 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manuel, D. G. et al. Measuring burden of unhealthy behaviours using a multivariable predictive approach: life expectancy lost in Canada attributable to smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, and diet. PLoS Med.13, e1002082 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, T. C. et al. Derivation and validation of 10-year all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality prediction model for middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling adults in Taiwan. PLoS ONE15, e0239063 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, W. J., Peng, L. N., Chiou, S. T. & Chen, L. K. Physical health indicators improve prediction of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among middle-aged and older people: a national population-based study. Sci. Rep.7, 40427 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng, S. F., Vaz, L., Qureshi, N. & Kai, J. Prediction of premature all-cause mortality: A prospective general population cohort study comparing machine-learning and standard epidemiological approaches. PLoS ONE14, e0214365 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lund, J. L. et al. Development and validation of a 5-year mortality prediction model using regularized regression and Medicare data. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf.28, 584–592 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang C. L., World Health Organization. Life Table and Mortality Analysis (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1979).

- 22.Luy, M., Di Giulio, P., Di Lego, V., Lazarevič, P. & Sauerberg, M. Life expectancy: frequently used, but hardly understood. Gerontology66, 95–104 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman, S. C. Formulae for cause-deleted life tables. Stat. Med6, 527–528 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puljević, C. et al. Closing the gaps in tobacco endgame evidence: a scoping review. Tob. Control31, 365–375 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boersma, P., Villarroel, M. A., Vahratian, A. Heavy Drinking Among U.S. Adults, 2018. NCHS Data Brief374, 1–8 (2020). [PubMed]

- 26.Hu, A. et al. The transition of alcohol control in China 1990-2019: Impacts and recommendations. Int. J. Drug Policy105, 103698 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manthey, J. et al. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030: a modelling study. Lancet393, 2493–2502 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, Y. C. et al. Vegetable and fruit consumption among chinese adults and associated factors: A Nationally Representative Study of 170,847 Adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci.30, 863–874 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO-UNEP Health and Environment Linkages Initiative. Environment and health in developing countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021.

- 30.Lv, J. et al. Adherence to healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.69, 1116–1125 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin, C. et al. The relative validity and reproducibility of food frequency questionnaires in the China Kadoorie Biobank Study. Nutrients14, 794 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han, Y. et al. Lifestyle, cardiometabolic disease, and multimorbidity in a prospective Chinese study. Eur. Heart J.42, 3374–3384 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauhoff, S. Systematic self-report bias in health data: impact on estimating cross-sectional and treatment effects. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol.11, 44–53 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai, R. et al. Projections of future life expectancy in China up to 2035: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health8, e915–e922 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, Z. et al. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int. J. Epidemiol.40, 1652–1666 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dongmei, Y. et al. China Nutrition and Health Surveys (1982−2017). China CDC Wkly.3, 193–195 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ajnakina, O. et al. Development and validation of prediction model to estimate 10-year risk of all-cause mortality using modern statistical learning methods: a large population-based cohort study and external validation. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.21, 8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross, R. K. et al. Validation of a 5-year mortality prediction model among U.S. medicare beneficiaries. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.68, 2898–2902 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi, L. C., Jackson, S. E., Lee, S. J., Wardle, J. & Steptoe, A. The development and validation of an index to predict 10-year mortality risk in a longitudinal cohort of older English adults. Age Ageing46, 427–432 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganna, A. & Ingelsson, E. 5 year mortality predictors in 498,103 UK Biobank participants: a prospective population-based study. Lancet386, 533–540 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bérard, E. et al. Ten-year risk of all-cause mortality: assessment of a risk prediction algorithm in a French general population. Eur. J. Epidemiol.26, 359–368 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chinese Nutrition Society. The Chinese Dietary Guidelines (Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, 2016).

- 43.Ainsworth, B. E. et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.43, 1575–1581 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moons, K. G. et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med.162, W1–W73 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du, H. et al. Fresh fruit consumption and major cardiovascular disease in China. N. Engl. J. Med.374, 1332–1343 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee, S. J., Lindquist, K., Segal, M. R. & Covinsky, K. E. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA295, 801–808 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahn, C., Hwang, Y. & Park, S. K. Predictors of all-cause mortality among 514,866 participants from the Korean National Health Screening Cohort. PLoS ONE12, e0185458 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mannan, H. R., Stevenson, C. E., Peeters, A. & McNeil, J. J. A new set of risk equations for predicting long term risk of all-cause mortality using cardiovascular risk factors. Prev. Med.56, 41–45 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang, S. et al. Development of a model to predict 10-year risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic heart disease using the China Kadoorie Biobank. Neurology98, e2307–e2317 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manuel D. G. et al. Seven more years: the impact of smoking, alcohol, diet, physical activity and stress on health and life expectancy in Ontario. In An ICES/PHO Report. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and Public Health Ontario (2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

CKB data are available to all bona fide researchers. Details of how to access and details of the data release schedule are available from www.ckbiobank.org/site/Data+Access. Researchers who are interested in obtaining the raw individual participant data related to this paper can contact pdc@kscdc.net. Please note that access will be granted after an evaluation of accordance with Chinese legislation. We anticipate that the data will become available within 8 weeks after requested access. As stated in the access policy, the CKB study group must maintain the integrity of the database for future use and regulate data access to comply with prior conditions agreed with the Chinese government. All approved users are required to sign a data use agreement that outlines specific restrictions to ensure data security and regulatory compliance. The raw data of the CNHS study are not publicly available due to data privacy regulations. Researchers may contact the corresponding author Dongmei Yu (yudm@ninh.chinacdc.cn) to request access to the summary data by providing methodologically sound scientific proposals. Access will be granted within approximately 8 weeks. A data use agreement must be signed before approval which stipulates that the data is allocated only for non-commercial research purposes. Source data are provided with this paper.

Analysis code for this study is available at https://github.com/qiufen-code/lifestyle-simulation-study.