Abstract

Background

Traditional biological experiments for protein subcellular localization are costly and inefficient, while sequence-based methods fail to capture spatial dynamics of protein translocation. Existing deep learning models primarily rely on convolutions and lack global image integration, particularly in small-sample scenarios.

Methods

We propose ProteinFormer, a novel model integrating biological images with an enhanced pre-trained transformer architecture. It combines ResNet for local feature extraction and a modified transformer for global information fusion. To address data scarcity, we further develop GL-ProteinFormer, which incorporates residual learning, inductive bias, and a ConvFFN.

Results

ProteinFormer achieves state-of-the-art performance on the Cyto_2017 dataset for both single-label (91%  -score) and multi-label (81%

-score) and multi-label (81%  -score) tasks. GL-ProteinFormer demonstrates superior generalization on the limited-sample IHC_2021 dataset (81%

-score) tasks. GL-ProteinFormer demonstrates superior generalization on the limited-sample IHC_2021 dataset (81%  -score), with ConvFFN improving Accuracy by 4% while reducing computational costs.

-score), with ConvFFN improving Accuracy by 4% while reducing computational costs.

Conclusion

ProteinFormer and its GL-ProteinFormer variant show superior performance over existing convolution-based methods. By fusing biological images with transformer-based global feature modeling, the proposed approach offers a robust and efficient solution for protein subcellular localization, especially in data-limited settings.

Keywords: Protein subcellular localization, Biological images, Transformer, ResNet, ConvFFN

Introduction

One of the core areas of bioinformatics is proteomics [1]. Research shows a single human cell contains approximately  proteins [2], and 20–30% of proteins have multiple potential subcellular locations [3, 4]. Accurate protein subcellular localization is crucial for proteomics research—especially amid recent advances in single-cell and spatial proteomics technologies—and indispensable for prioritizing drug development targets [5, 6]. Protein mislocalization is associated with cellular dysfunction and disease [7–9].

proteins [2], and 20–30% of proteins have multiple potential subcellular locations [3, 4]. Accurate protein subcellular localization is crucial for proteomics research—especially amid recent advances in single-cell and spatial proteomics technologies—and indispensable for prioritizing drug development targets [5, 6]. Protein mislocalization is associated with cellular dysfunction and disease [7–9].

Methods for protein subcellular localization fall into three categories: traditional biological experiments, protein amino acid sequence-based approaches [10], and protein microscopic image-based methods [11, 12]. Traditional experiments are costly and inefficient, while sequence-based methods fail to capture dynamic changes in protein activity trajectories and function, limiting their use in studying localization dynamics. In contrast, 2D microscopic images provide intuitive, interpretable representations of proteins and their subcellular locations; with continuous advances in imaging technology [13], image-based prediction models have become a focused, widely concerned research area.

Over the past decade, various methodologies integrating microscopy images with machine learning and deep learning have been developed to analyze protein localization systematically [12, 14–16]. Many classical machine learning classifiers, such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) [17–20], have been used to build localization predictors. Traditional machine learning requires manual extraction of subcellular features (SLF [21]) from microscopic images, which is restricted by human prior knowledge and involves a cumbersome adjustment process. In recent years, deep learning models have gained significant attention for simplifying feature extraction [22, 23] and have been widely applied in fields including protein microscope image analysis [24, 25]. For example, the Loc-CAT algorithm classifies protein localization into 29 subcellular compartments [26]; DeepLoc evaluates protein localization in yeast [27]; ResNet achieves promising results on microscopic images from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) datasets [28]; Aggarwal et al. [29] proposes a stack-integrated deep learning model using integration techniques on HPA databases; Tu et al. [30] develops SIFLoc, a self-supervised pretraining method to enhance localization recognition in immunofluorescence microscopy images. In the past two years, high-performance deep learning models such as DeepLoc 2.0 [31], NetSurfP-3.0 [32], and ML-FGAT [33] have emerged. With the boom in single-cell research, protein localization with single-cell and spatial resolution has become critical [34]: Zhang et al. [35] proposes LocPro, a multi-label, multi-granularity framework integrating the pre-trained ESM2 model and PROFEAT features with a hybrid CNN-FC-BiLSTM architecture; HCPL [36] robustly localizes single-cell protein patterns from weakly labeled data to address cellular variability; Zhu et al. [37] develops cell-based techniques with pseudo-label assignment to explore localization patterns across diverse cells, accounting for intra-cell heterogeneity; Duhan and Kaundal [38] presents an extended deep learning method for species-specific localization prediction in Arabidopsis, exploring CNN-based algorithms and developing modules for 12 single-location, 9 dual-location classes, and membrane-type proteins.

In recent years, transformers leverage self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies between image regions, showing advantages in image processing. Liao et al. [39] proposes Swin-PANet, which achieves significant performance and interpretability in medical image segmentation; with the emergence of Vision Transformer (ViT [40]), transformers outperform state-of-the-art convolutional networks in vision tasks. Kanchan Jha et al. [41] use ViT and a language model to predict proteins and protein interactions, confirming the method’s effectiveness.

Deep learning applications in protein science advance rapidly. Recent studies have further advanced transformer-based and novel models for protein-related tasks. DeepSP [42] introduced a convolutional block attention module to capture protein occupancy profile changes for spatial proteomics, showcasing attention mechanism innovations. the Mamba architecture (based on state space models) enables efficient long-sequence modeling, with Vision Mamba (Vim) [43] as an efficient visual backbone (competitive on ImageNet/COCO tasks with better computation/memory efficiency than transformers). GraphMamba [44] combines graph structure learning with Mamba for hyperspectral image classification.

However, these methods have certain limitations. DeepSP [42] primarily relies on mass spectrometry-based spatial proteomics data, while Vision Mamba [43] and GraphMamba [44] are nascent computer vision architectures, not extensively tailored for biological image analysis (e.g., protein microscopic localization). Our ProteinFormer differs by proposing a principled end-to-end framework—specifically designed for and learning directly from 2D biological microscopy images via a transformer. Unlike methods dependent on non-image data or general vision architectures, ProteinFormer and its variant GL-ProteinFormer address unique protein microscopy data characteristics, with targeted modifications (residual attention, ConvFFN) for data-scarce settings defining our comparative advantage.

Inspired by transformer characteristics, this paper leverages transformers to model protein microscopic images. We propose ProteinFormer, a novel end-to-end model [45] for protein subcellular localization, whose core idea is to introduce a transformer architecture to model global image relationships. To cover common scenarios, we selected two protein microscope image datasets: For the Cyto 2017 dataset (sufficient samples [46]), ProteinFormer uses a ResNet model to extract features at four scales (high to low); all features except the lowest resolution undergo average pooling, are unified to the lowest resolution, and then concatenated. A transformer-based feature fusion model serializes 2D image features and inputs them into the transformer to learn class tokens for classification tasks. For the IHC 2021 dataset (limited samples [47]), we enhance ProteinFormer to propose GL-ProteinFormer—a transformer-based model with visual bias. Its feature extraction component is built with Swin-Transformer [48], using only the lowest-resolution features as initial inputs; these features are serialized and fed into the transformer, which learns attention residuals instead of full attention maps. Additionally, we redesign the transformer’s FFN component with convolutional layers (replacing fully connected layers) to build a predictive model suitable for small datasets. Comparative evaluations against mainstream vision classification models show that our GL-ProteinFormer performs better in protein subcellular localization tasks.

Materials and methods

Datasets

Cyto_2017 dataset

The Cyto_2017 dataset was originally released for the “2017 Cyto Challenge” at the International Society for Advancement of Cytometry (ISAC) conference. Comprising 20000 samples sourced from the Cell Atlas (a component of the Human Protein Atlas), this dataset features high-resolution fluorescence microscopy images. Each sample contains four channel-specific images: three reference channels highlighting subcellular structures (nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, and microtubules) and one protein-specific channel targeting the protein of interest. The primary task is to identify which of 13 major subcellular compartments contain the target protein, including multi-localization cases.

During preprocessing, samples with one corrupted channel were excluded, resulting in 18756 validated samples. The dataset exhibits significant class imbalance, containing 7272 single-label and 11484 multi-label samples. Both subsets were randomly partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio.

IHC_2021 dataset

The HPA serves as a core public resource for spatial proteomics, comprising six subrepositories: Tissue Atlas, Cell Atlas, Pathology Atlas, Blood Atlas, Brain Atlas, and Metabolic Atlas. Within this framework, the Tissue Atlas subrepository contains over 13 million immunohistochemistry (IHC) microscopy images covering 44 human tissues and organs.

Derived from the HPA Tissue Atlas, the IHC_2021 dataset was constructed to systematically characterize protein distribution across major human tissues and organs.

The dataset construction workflow comprised the following steps: Firstly, raw IHC microscopy images were extracted from the Tissue Atlas, excluding those specimens with protein expression levels annotated as “not detected”; Secondly, image annotations were curated from both the HPA and the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). All IHC microscopy images within the IHC_2021 dataset employ chemical staining where brown regions indicate protein localization and blue-purple regions denote DNA; Finally, protein and DNA channels were isolated using the Linear Spectral Unmixing (LIN) algorithm.

The IHC_2021 dataset comprises two distinct components: a single-label dataset and a mixed-label dataset. The single-label dataset contains 1386 images corresponding to 14 antibody proteins, annotated with 7 subcellular localization classes (endoplasmic reticulum, cytoskeleton, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, nucleoli, nucleus, vesicles). The mixed-label dataset includes an additional 24 antibody proteins (38 total), comprising 1743 images (531 multi-label samples and 1212 single-label samples). Its annotations extend to 9 subcellular classes, adding lysosomes and cytoplasm. For this study, two classification models were established using filtered subsets:

A 7-class single-label classification model trained on 2053 single-label images representing the 7 overlapping subcellular compartments common to both the Cyto_2017 and IHC_2021 datasets.

A 9-class multi-label classification model trained on the 531 multi-label images from the IHC_2021 multi-label dataset.

Strategies for class imbalance mitigation

Beyond the stratified sampling strategy, we further investigated the impact of class imbalance mitigation techniques on model performance, particularly for the multi-label task on the IHC_2021 dataset which exhibited more severe imbalance. We experimented with a class-weighted loss function during the training of GL-ProteinFormer. The weight  for each class i was computed inversely proportional to the class frequency in the training set:

for each class i was computed inversely proportional to the class frequency in the training set:  , where N is the total number of training samples,

, where N is the total number of training samples,  is the number of samples for class i, and K is the total number of classes. This approach assigns higher weights to minority classes, penalizing misclassifications on them more heavily.

is the number of samples for class i, and K is the total number of classes. This approach assigns higher weights to minority classes, penalizing misclassifications on them more heavily.

Our ablation studies indicated that while class-weighted loss slightly improved the Recall for underrepresented classes (e.g., lysosomes and vesicles), it occasionally led to a slight decrease in overall Accuracy and Precision, potentially due to increased overfitting on noisy samples from rare classes. Given that our primary goal was to achieve a balanced performance across all metrics, and considering the effectiveness of the stratified sampling itself, we ultimately retained the standard loss function for the reported results to ensure a fair comparison with other methods that did not employ such weighting. This decision underscores the challenge of handling extreme class imbalance in small-scale biological datasets and highlights the need for future work in this area.

Model architecture

Conventional CNN-based methods for protein subcellular localization often rely on average pooling for global feature extraction and neglect multi-scale information, leading to limited representational capacity. To address this, we propose ProteinFormer — an end-to-end transformer-based model for protein subcellular localization. Given transformer’s requirement for substantial training data, the model is initially developed on the Cyto_2017 dataset with abundant samples.

To enhance generalizability on the small-scale IHC_2021 dataset, we further introduce GL-ProteinFormer. This improved model incorporates visual inductive biases into the transformer architecture to strengthen feature extraction capabilities. To reduce the learning complexity of GL-ProteinFormer on limited data, two key enhancements are implemented: (1) Residual Attention: Learning residual mappings of attention matrices rather than full attention matrices, grounded in residual learning theory; (2) ConvFFN: Replacement of standard FFN layers with convolutional blocks to increase local feature extraction.

ProteinFormer model

ProteinFormer employs an end-to-end design integrating CNNs with the transformer architecture, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Its core structure comprises two synergistic modules:

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the ProteinFormer model

1. Multi-Scale Feature Extraction: A ResNet backbone generates four feature maps of progressively reduced resolutions. The three highest-resolution maps undergo average pooling for downsampling, aligned to the coarsest resolution, and concatenated along the channel dimension to form a unified multi-scale representation.

2. Global Feature Fusion: The concatenated features are serialized into tokens and processed by a transformer encoder. Self-attention mechanisms model long-range dependencies, with the learned class token serving as the classification basis.

Step1: Feature extraction and multi-scale fusion

The input protein microscopy image  (4 channels, spatial resolution

(4 channels, spatial resolution  ) undergoes multi-scale feature extraction through ResNet-based convolutional modules

) undergoes multi-scale feature extraction through ResNet-based convolutional modules  . The hierarchical features

. The hierarchical features  are computed as:

are computed as:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where  represent high-resolution features and

represent high-resolution features and  denotes the lowest-resolution feature.

denotes the lowest-resolution feature.

Let the spatial resolution of the input image be  , where H and W denote the height and width of the image respectively. The downsampling operation, denoted by

, where H and W denote the height and width of the image respectively. The downsampling operation, denoted by  , is implemented using strided convolutions with stride 2. The spatial resolutions of the feature maps satisfy:

, is implemented using strided convolutions with stride 2. The spatial resolutions of the feature maps satisfy:

| 5 |

and for  , follow the recurrence relations:

, follow the recurrence relations:

| 6 |

To integrate high-level semantics with low-level details, high-resolution features  are processed by average pooling to generate

are processed by average pooling to generate  , whose resolution is unified to the coarsest

, whose resolution is unified to the coarsest  :

:

| 7 |

These pooled features are then concatenated with the lowest-resolution feature  to form

to form  :

:

| 8 |

| 9 |

where  is a weight matrix, b denotes the bias vector, ReLU(

is a weight matrix, b denotes the bias vector, ReLU( ) is the activation function, and

) is the activation function, and  represents the feature after linear projection and ReLU activation (serving as the input to the subsequent Transformer encoder). Here,

represents the feature after linear projection and ReLU activation (serving as the input to the subsequent Transformer encoder). Here,  are channel numbers of

are channel numbers of  , and

, and  is the target channel number for linear projection.

is the target channel number for linear projection.

Step2: Token serialization and transformer encoding

The feature tensor  is serialized in a 1D token sequence. Non-overlapping

is serialized in a 1D token sequence. Non-overlapping  patches are projected via fully connected layers to generate L tokens denoted as

patches are projected via fully connected layers to generate L tokens denoted as  :

:

| 10 |

A learnable class token  is appended as a global representation carrier, forming the complete input sequence:

is appended as a global representation carrier, forming the complete input sequence:

| 11 |

The modeling of token dependencies is achieved through multi-head attention. During this procedure, the  tokens undergo linear transformations and are projected into three distinct feature spaces, namely Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V).The Attention operation can be expressed as:

tokens undergo linear transformations and are projected into three distinct feature spaces, namely Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V).The Attention operation can be expressed as:

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

where

.

.

The channel dimension is partitioned into H groups for parallel computation. The operation of Multi Head Attention can be expressed as:

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

A feed-forward network (FFN) further refines features:

| 19 |

The FFN here is a feed-forward neural network composed of multiple layers of perceptrons. Our transformer consists of several Attention modules. After passing through the Transformer network, we obtain a set of sequence features  . The class token

. The class token  , which is appended to the input sequence as a global representation carrier, is extracted as the classification basis. At this point,

, which is appended to the input sequence as a global representation carrier, is extracted as the classification basis. At this point,  has learned classification-related information from the image features while disregarding classification-irrelevant information. The class token

has learned classification-related information from the image features while disregarding classification-irrelevant information. The class token  is then linearly mapped to a N-dimensional distribution estimation vector

is then linearly mapped to a N-dimensional distribution estimation vector  . The specific operation is:

. The specific operation is:

| 20 |

where  .

.

Step 3: Loss function design

For single-label classification, the output distribution is normalized via Softmax, and cross-entropy loss is applied:

| 21 |

|

22 |

Here, B is the batch size, and  indicates whether sample j belongs to class i.

indicates whether sample j belongs to class i.

For multi-label classification, binary cross-entropy loss is used independently per class:

|

23 |

The predicted probability  corresponds to class i for sample j, with probabilities normalized independently across classes.

corresponds to class i for sample j, with probabilities normalized independently across classes.

GL-ProteinFormer model

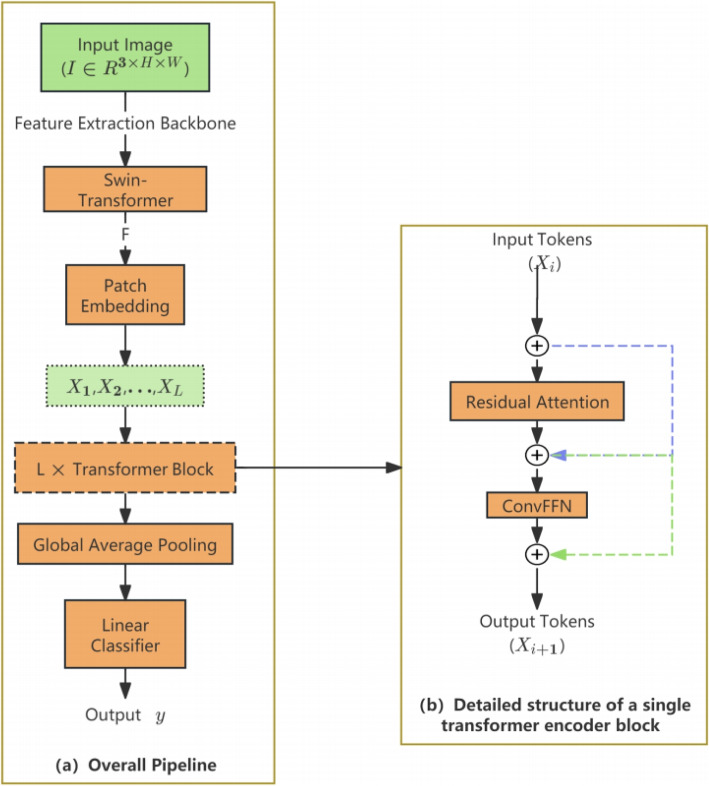

To address the characteristics of the small-scale IHC_2021 dataset (limited samples and reduced image dimensions), GL-ProteinFormer enhances ProteinFormer through a dual optimization strategy: (1) employing a lightweight Swin-Transformer backbone to reduce parameters. (2) incorporating residual attention and convolutional enhancement modules to mitigate overfitting risks. The overall architecture is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Architecture of the GL-ProteinFormer model. a Overall pipeline. An input protein microscopy image is first processed by a Swin-Transformer backbone to extract feature maps. The resulting lowest-resolution features are serialized into a sequence of tokens via a patch embedding layer. This token sequence is then processed by a stack of L identical Transformer encoder blocks (the detailed structure of a single block is shown in b). The output sequence from the final Transformer block is aggregated via global average pooling and passed through a linear classification head (CLS Head) to generate the final predictions. b Detailed structure of a single Transformer encoder block. The block consists of two main modules: a residual attention module (Eqs. 30–31) and a ConvFFN module (Eqs. 33–36), each followed by a residual connection and layer normalization. The residual attention module computes attention scores by incorporating the attention map from the previous block ( ). The ConvFFN module uses depthwise separable convolutions to reintroduce spatial inductive biases. The output is a refined token sequence of the same length, which is passed to the next block

). The ConvFFN module uses depthwise separable convolutions to reintroduce spatial inductive biases. The output is a refined token sequence of the same length, which is passed to the next block

Step 1: Feature extraction

The model processes protein microscopy images  (RGB format) from the IHC_2021 dataset. A Swin-Transformer backbone extracts the lowest-resolution feature map:

(RGB format) from the IHC_2021 dataset. A Swin-Transformer backbone extracts the lowest-resolution feature map:

| 24 |

where  and

and  denote the height and width of the feature map, respectively.

denote the height and width of the feature map, respectively.

Step 2: Feature serialization

The 2D feature map F is partitioned into non-overlapping  patches, which are linearly projected into a token sequence

patches, which are linearly projected into a token sequence  . The sequence length L is determined by:

. The sequence length L is determined by:

| 25 |

Step 3: Residual attention mechanism

To ease the optimization difficulty of the transformer model, this study introduces a residual learning concept: except for the initial Attention module, subsequent modules learn the residual between the current Attention and the target Attention, rather than directly learning the full Attention matrix. After this modification, only the first layer requires generating the complete Attention values.

(1) Base Attention mechanism

An input token sequence X is transformed into Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) representations via linear projections:

| 26 |

| 27 |

| 28 |

where

.

.

Token similarity is computed via Query-Key dot product, and new representations are generated by the weighted aggregation of Values:

| 29 |

(2) Residual Attention

For the i-th Attention module ( ), in addition to the L tokens obtained by the previous module, the Attention value obtained by the

), in addition to the L tokens obtained by the previous module, the Attention value obtained by the  th Attention module is also taken as the input:

th Attention module is also taken as the input:

| 30 |

| 31 |

where  is a zero matrix.

is a zero matrix.

Step 4: ConvFFN

Following global feature aggregation through Attention Modules, conventional transformers employ MLP-based FFN for feature fusion:

| 32 |

However, feature serialization discards critical spatial inductive biases (e.g., local connectivity, translation equivariance). Standard FFNs treat input tokens as independent units, failing to leverage inherent image structural priors that CNNs naturally preserve. To address this limitation, we design a ConvFFN that reconstructs visual inductive biases through embedded convolution operations, significantly improving generalization on small-scale datasets. The enhanced module concurrently maintains global information aggregation while augmenting local feature extraction capabilities.

ConvFFN Implementation:

Each ConvFFN module processes an input token sequence  through four stages.

through four stages.

(1) Channel dimensionality reduction: Linear projection  compresses channels:

compresses channels:

| 33 |

(2) Spatial structure reconstruction: We reorganize sequential features into 2D image features via the reshape operation:

operation:

| 34 |

(3) Convolutional Feature Extraction: Depthwise separable convolutions capture visual biases with lower parameter and costs than standard convolutions:

| 35 |

where h( ) is the ReLU activation function and the depthwise separable convolution uses a kernel size of 3

) is the ReLU activation function and the depthwise separable convolution uses a kernel size of 3 3, stride 1, and padding 1.

3, stride 1, and padding 1.

(4) Feature Restoration and Mapping: The features are recombined into a sequential form, and the channel dimension is restored to the original size C via linear mapping  :

:

| 36 |

The sequential features output from the final ConvFFN module undergo an average pooling operation, followed by a fully connected layer  to obtain the final class distribution prediction:

to obtain the final class distribution prediction:

| 37 |

Step 5: Loss functions

Single-label classification: Standard cross-entropy loss is employed. The network output is normalized via softmax, and the loss is computed between the normalized output distribution ( ) and the true distribution (y):

) and the true distribution (y):

| 38 |

|

39 |

Multi-label Classification:Binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss is used. Each class is treated as an independent binary prediction task. The BCE loss is defined as:

| 40 |

Results and discussion

Training process design

The number of model training epochs used in the experiment was set to 50. Use the Adam processor and select a fixed step size adjustment learning rate strategy (multiply the learning rate by 0.9 every 5 epochs).

For the ProteinFormer model trained on the Cyto_2017 dataset with sufficient sample size, the image pixels in this dataset are relatively large, so batch_size is set to 8. Set the initial learning rate  ,

,  , and weight decay is set to 0. For the GL-ProteinFormer model trained on the IHC_2021 dataset data set with insufficient sample size, the image resolution in this data set is relatively small, so batch_size is set to 64. Initial learning rate

, and weight decay is set to 0. For the GL-ProteinFormer model trained on the IHC_2021 dataset data set with insufficient sample size, the image resolution in this data set is relatively small, so batch_size is set to 64. Initial learning rate  ,

,  , weight decay is set to 0. Other network model hyperparameters of ProteinFormer model and GL-ProteinFormer model are shown in the Table 1.

, weight decay is set to 0. Other network model hyperparameters of ProteinFormer model and GL-ProteinFormer model are shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Network model hyperparameters

| Hyperparameters | ProteinFormer | GL-ProteinFormer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Name | Setting value | Setting value |

| C | Number of channels | 4 | 3 |

| P | Image blocks | 4 | 4 |

| Head | Learnable attention type | 8 | 8 |

| N | Number of categories | 13 | 7 (single label), 9 (multiple labels) |

|

Multi-scale feature channel |  |

- |

Hyperparameter impact mechanism

In this experiment, four evaluation indicators, Accuracy, Precision, Recall rate and  score (

score ( ) are used as evaluation criteria. Among them,

) are used as evaluation criteria. Among them,  score is closely related to Accuracy and Recall rate, and it is a comprehensive index of these two ratios.

score is closely related to Accuracy and Recall rate, and it is a comprehensive index of these two ratios.

Results and analysis of single - label classification task

To assess ProteinFormer on the Cyto_2017 dataset, we tuned key hyperparameters (learning rate, crop size, embedding size, transformer depth, pre - training) for single-label subcellular localization (predicting via max output value).

We compared three parameter initializations: no pre-trained weights, ImageNet-pre-trained (for visual transfer), and multi-label task-pre-trained (for task alignment). Random cropping standardized sizes but risked losing details, so we used patches to convert features to tokens. Tuning block embedding size balanced efficiency and fidelity.

Transformer depth trade-off: more layers modeled complex relationships but increased cost; we found optimal depths.

For GL-ProteinFormer, we tuned learning rate, transformer depth, and image scaling. Given small RGB dataset similarity to ImageNet, we tested ImageNet-pre-trained weights. We also explored scaled image processing to retain info.

The hyperparameter tuning experimental results of the model on the single-label task are presented in Table 2 (partially displayed). (1) For the ProteinFormer model, extensive attempts have revealed that setting the learning rate to  , random clipping size to 1024, and embedded patch size to 4 while utilizing a transformer with stacked 6-layer Attention modules leads to improved classification accuracy when pre-training weights from multi-label tasks are employed. (2) Similarly, for the GL-ProteinFormer model, it has been observed that setting the learning rate to

, random clipping size to 1024, and embedded patch size to 4 while utilizing a transformer with stacked 6-layer Attention modules leads to improved classification accuracy when pre-training weights from multi-label tasks are employed. (2) Similarly, for the GL-ProteinFormer model, it has been observed that setting the learning rate to  , scaling the image size to 256*256, and using a transformer with stacked 6-layer Attention modules yield better classification accuracy by loading ImageNet’s classification weights compared to not loading them.

, scaling the image size to 256*256, and using a transformer with stacked 6-layer Attention modules yield better classification accuracy by loading ImageNet’s classification weights compared to not loading them.

Table 2.

Experimental results and analysis of single label tasks

| ProteinFormer | Acc | Pre | Rec |  |

GL-ProteinFormer | Acc | Pre | Rec |  |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clipping sizea | 256 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.35 | learning rate |  |

0.76 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| 512 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.69 |  |

0.77 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||

| 1024 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 |  |

0.73 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.75 | ||

| patch sizeb | 2 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.84 | scaling sizec | 128 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 4 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 256 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||

| 8 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.9 | 0.83 | 512 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.79 | ||

| depthd | 1 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.82 | depthd | 1 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| 3 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 3 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.77 | ||

| 6 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 6 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||

| pre-traine | not loaded | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.51 | pre-traine | not loaded | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| imagenet | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | ImageNet | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||

| multi-label tasks | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

aThis means that the original images of different sizes are uniformly cut to the same size by random cropping before the image is input into the network

bThis means that the image features are serialized by patch into tokens and input into transformerwith non-overlapping patch sizes

cThis refers to the size of the image after scaling

dThis is the depth of transformer

eThis refers to the loading of pre-trained model parameters

Bold values indicate the best F₁-score achieved for a specific hyperparameter under investigation

Results and analysis of multi-label classification task

The same hyperparameter tuning experiment was conducted for the multi-label task, yielding consistent results. Additionally, a hyperparameter tuning experiment targeting the threshold value was performed specifically for the multi-label task. The distinction between the multi-label and single-label tasks lies in how the label distribution of network output is utilized to determine protein subcellular localization. Instead of directly assigning the maximum estimated value as the label, a threshold value  is employed to determine the specific subcells. If the model outputs a class i estimate that exceeds

is employed to determine the specific subcells. If the model outputs a class i estimate that exceeds  , it indicates that the protein belongs to class i, and vice versa. As a critical hyperparameter, setting an appropriate threshold significantly impacts classification performance. We perform experiments on

, it indicates that the protein belongs to class i, and vice versa. As a critical hyperparameter, setting an appropriate threshold significantly impacts classification performance. We perform experiments on  = {0.1,0.3, 0.5,0.7,0.9} in sequence. The ablation results of threshold values are shown in Table 3. For the ProteinFormer model,

= {0.1,0.3, 0.5,0.7,0.9} in sequence. The ablation results of threshold values are shown in Table 3. For the ProteinFormer model,  = 0.5 was selected according to the

= 0.5 was selected according to the  index of comprehensive evaluation, and

index of comprehensive evaluation, and  values were found to be between 0.79–0.82.79.82 without large fluctuations, so

values were found to be between 0.79–0.82.79.82 without large fluctuations, so  performance was robust to the threshold. Following similar evaluations for GL-ProteinFormer model, it was observed that optimal performance occurred at a threshold of 0.3.

performance was robust to the threshold. Following similar evaluations for GL-ProteinFormer model, it was observed that optimal performance occurred at a threshold of 0.3.

Table 3.

Multi-label experimental results and analysis

| Threshold | ProteinFormer | GL-ProteinFormer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall |  |

Accuracy | Precision | Recall |  |

|

| 0.1 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.60 |

| 0.3 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| 0.5 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.61 |

| 0.7 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.60 |

| 0.9 | 0.66 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.58 |

| Bold values indicate the best F₁-score achieved by each model (ProteinFormer and GL-ProteinFormer) across different thresholds | ||||||||

Performance comparison

The performance is compared with other methods on the Cyto_2017 dataset as shown in the Tables 4 and 5. The performance of the ProteinFormer model was evaluated in the single-label task against human experts, state-of-the-art methods and mainstream visual task methods. It is worth noting that even the worst-performing neural networks achieved significantly higher  values than human experts, highlighting the superiority of deep learning approaches. However, it should be acknowledged that deep learning models still rely on data annotation, supervision, and adjustment by human experts. Therefore, integrating the expertise of human professionals may lead to further improvements in performance. Furthermore, our method outperforms mainstream visual task methods with an impressive

values than human experts, highlighting the superiority of deep learning approaches. However, it should be acknowledged that deep learning models still rely on data annotation, supervision, and adjustment by human experts. Therefore, integrating the expertise of human professionals may lead to further improvements in performance. Furthermore, our method outperforms mainstream visual task methods with an impressive  value of 90

value of 90 , surpassing ResNet convolutional neural networks by 4 percentage points and Swin-Transformer and ViT by 5 percentage points respectively. It also slightly outperforms UniLoc (

, surpassing ResNet convolutional neural networks by 4 percentage points and Swin-Transformer and ViT by 5 percentage points respectively. It also slightly outperforms UniLoc ( value of 89%), demonstrating its competitive edge in capturing fine-grained subcellular patterns. This suggests that our approach is particularly well-suited for protein subcellular localization tasks.

value of 89%), demonstrating its competitive edge in capturing fine-grained subcellular patterns. This suggests that our approach is particularly well-suited for protein subcellular localization tasks.

Table 4.

Single-label performance comparison on the Cyto_2017 dataset

| Method | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ViT [40] | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| Swin-Transformer [48] | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.87 |

| GapNet-PL [49] | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.82 |

| Ensemble of experts [49] | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.60 |

| Ensemble of scholars [49] | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.57 |

| ResNet [50] | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| UniLoc [51] | 0.9 | 0.86 | 0.9 | 0.89 |

| ProteinFormer | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Bold values indicate the best performance for each metric (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F₁) among all compared methods | ||||

Table 5.

Multi-label performance comparison on the Cyto_2017 dataset

| Method | Precision | Recall |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ML-FGAT [6] | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| DeepLoc [28] | 0.79 | 0.45 | 0.52 |

| LocPro [35] | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Swin-Transformer [48] | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.76 |

| GapNet-PL [49] | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.78 |

| ResNet [50] | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| FCN-Seg [52] | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

| Convolutional MIL [53] | 0.71 | 0.40 | 0.47 |

| M-CNN [54] | 0.90 | 0.66 | 0.75 |

| DenseNet-121 [55] | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| ProteinFormer | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

Finally, we compared our method with the current top-performing method on this dataset, GapNet-PL. Our method demonstrated significant advantages in the comprehensive  score compared to GapNet-PL. This is attributed to the fact that our method achieved a Precision value of 88

score compared to GapNet-PL. This is attributed to the fact that our method achieved a Precision value of 88 , which is significantly higher than GapNet-PL, while our Recall value of 91

, which is significantly higher than GapNet-PL, while our Recall value of 91 is slightly lower by 4 percentage points. Both methods performed comparably in terms of accuracy. In the evaluation mode of the current dataset, our method achieved the best performance in three out of the key metrics.

is slightly lower by 4 percentage points. Both methods performed comparably in terms of accuracy. In the evaluation mode of the current dataset, our method achieved the best performance in three out of the key metrics.

The ProteinFormer algorithm is compared with advanced protein subcellular localization algorithms and mainstream image classification algorithms in the multi-label task. Our model demonstrates a 3 improvement in Precision value, a 6

improvement in Precision value, a 6 improvement in Recall value, and a 5

improvement in Recall value, and a 5 improvement in

improvement in  scores compared to the ResNet algorithm. When compared to the GapNet-PL algorithm, our algorithm achieves an equivalent Precision value but surpasses it by 5

scores compared to the ResNet algorithm. When compared to the GapNet-PL algorithm, our algorithm achieves an equivalent Precision value but surpasses it by 5 in Recall value and by 3

in Recall value and by 3 in

in  . While ML-FGAT (85%

. While ML-FGAT (85%  ) and LocPro (82%

) and LocPro (82%  ) achieve higher

) achieve higher  scores than ProteinFormer (81%), ProteinFormer exhibits a relatively more consistent balance between Precision and Recall: our model yields a Precision of 0.84 and Recall of 0.80, whereas ML-FGAT shows a larger disparity with a Precision of 0.87 and Recall of 0.83 (a 4-percentage-point gap as well, but with a higher Precision bias). This characteristic may help mitigate potential overemphasis on high-precision categories, which is beneficial for maintaining stable performance across both over-represented and under-represented subcellular compartments in proteomics datasets.

scores than ProteinFormer (81%), ProteinFormer exhibits a relatively more consistent balance between Precision and Recall: our model yields a Precision of 0.84 and Recall of 0.80, whereas ML-FGAT shows a larger disparity with a Precision of 0.87 and Recall of 0.83 (a 4-percentage-point gap as well, but with a higher Precision bias). This characteristic may help mitigate potential overemphasis on high-precision categories, which is beneficial for maintaining stable performance across both over-represented and under-represented subcellular compartments in proteomics datasets.

It should be noted that although our algorithm’s Precision value is lower than that of M-CNN and Swin-Transformer algorithms, considering their poor performance on Recall, our approach significantly outperforms them when evaluated using the  metric. In conclusion, our algorithm shows competitive performance relative to other comparative methods for multi-label tasks.

metric. In conclusion, our algorithm shows competitive performance relative to other comparative methods for multi-label tasks.

The performance is compared with other methods on the IHC_2021 dataset as shown in Table 6. To assess the performance of the GL-ProteinFormer model in single-label tasks, we conducted a comparative analysis with ResNet, Swin-Transformer, ViT, UniLoc, and LocPro. The comprehensive metrics demonstrate that GL-ProteinFormer outperforms other models in terms of  values, achieving an impressive 81

values, achieving an impressive 81 — surpassing UniLoc (79%) by 2 percentage points and LocPro (77%) by 4 percentage points. These findings underscore the advantages of integrating global and local subcellular localization tasks. Compared to Swin-Transformer, which exhibits slightly lower performance, our approach achieves a 5 percentage point increase in accuracy, a 4 percentage point increase in Precision, as well as a remarkable improvement of 6 percentage points in both Recall and

— surpassing UniLoc (79%) by 2 percentage points and LocPro (77%) by 4 percentage points. These findings underscore the advantages of integrating global and local subcellular localization tasks. Compared to Swin-Transformer, which exhibits slightly lower performance, our approach achieves a 5 percentage point increase in accuracy, a 4 percentage point increase in Precision, as well as a remarkable improvement of 6 percentage points in both Recall and  . While we acknowledge the effectiveness of feature extraction employed by Swin-Transformer, our enhancements to Attention learning style and FFN have evidently contributed to superior final results.

. While we acknowledge the effectiveness of feature extraction employed by Swin-Transformer, our enhancements to Attention learning style and FFN have evidently contributed to superior final results.

Table 6.

The performance comparison with other methods on the IHC_2021 dataset

| Method | Single-label | Multi-label | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall |  |

Accuracy | Precision | Recall |  |

|

| LocPro [35] | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| ViT [40] | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.55 |

| Swin-Transformer[48] | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.60 |

| ResNet [50] | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

| UniLoc [51] | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| GL-ProteinFormer | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

In multi-label tasks, we also observe that models incorporating global and local information perform exceptionally well. When compared to models solely relying on either global or local information alone, both GL-ProteinFormer and Swin-Transformer exhibit significantly better overall evaluation indicators. GL-ProteinFormer achieves an Accuracy of 77%, outperforming LocPro (73%) and trailing UniLoc (75%) by a small margin, while its  score (63%) is comparable to UniLoc (64%) and higher than LocPro (61%). It should be noted that mainstream classification models tend to yield lower evaluation scores when applied to multi-label tasks due to their inherent complexity involving independent modeling for multiple labels. Moreover, the problem of learning difficulties caused by insufficient sample size of the data set is more obvious in multi-label tasks. But overall GL-ProteinFormer still performs well.

score (63%) is comparable to UniLoc (64%) and higher than LocPro (61%). It should be noted that mainstream classification models tend to yield lower evaluation scores when applied to multi-label tasks due to their inherent complexity involving independent modeling for multiple labels. Moreover, the problem of learning difficulties caused by insufficient sample size of the data set is more obvious in multi-label tasks. But overall GL-ProteinFormer still performs well.

Mechanism analysis of GL-ProteinFormer’s enhancements

The marked superiority of GL-ProteinFormer on the IHC _2021 dataset (Table 6) stems from its two core architectural innovations, meticulously designed to counter the challenges of small-sample learning in vision transformers.

Residual attention for enhanced optimization stability

The standard self-attention mechanism requires learning a high-dimensional attention map from scratch, a process prone to instability and overfitting with limited data. Our residual attention reformulates this objective. By learning the residual  to the previous layer’s attention

to the previous layer’s attention  (Eq. 31), the model performs incremental, stable updates rather than modeling the full complexity in one step.

(Eq. 31), the model performs incremental, stable updates rather than modeling the full complexity in one step.

Theoretical insight into gradient stability

This approach is grounded in residual learning principles and fundamentally alters the optimization landscape. From a gradient perspective, the learning objective for a standard attention layer is to map directly from input tokens to a potentially vast and unstructured attention matrix. In contrast, our residual attention module learns to predict an update ( ) to a already reasonable prior (the previous layer’s attention

) to a already reasonable prior (the previous layer’s attention  ). This setup has two key benefits for few-sample learning: (1) Smaller Gradient Variance: The gradients of the loss with respect to the parameters are typically smaller and more stable, as the model is only learning a perturbation to an existing state rather than a completely new one from a random initialization. This mitigates the explosive gradients that can occur in deep transformers trained on small data. (2) Improved Gradient Flow: The identity connection from

). This setup has two key benefits for few-sample learning: (1) Smaller Gradient Variance: The gradients of the loss with respect to the parameters are typically smaller and more stable, as the model is only learning a perturbation to an existing state rather than a completely new one from a random initialization. This mitigates the explosive gradients that can occur in deep transformers trained on small data. (2) Improved Gradient Flow: The identity connection from  to

to  ensures that even if the learned update

ensures that even if the learned update  is small or zero in the early stages of training, the module still functions by propagating the previous layer’s information effectively. This alleviates the vanishing gradient problem, ensuring that lower layers receive meaningful supervisory signals throughout training.

is small or zero in the early stages of training, the module still functions by propagating the previous layer’s information effectively. This alleviates the vanishing gradient problem, ensuring that lower layers receive meaningful supervisory signals throughout training.

This stabilized optimization process is evidenced by GL-ProteinFormer’s significant performance gain over ViT (e.g., a +7% improvement in  -score on single-label tasks), which lacks such stabilization and struggles to learn effective attention maps from limited data.

-score on single-label tasks), which lacks such stabilization and struggles to learn effective attention maps from limited data.

Analysis of class imbalance and ablation studies

To quantitatively evaluate the impact of our design choices, we conducted extensive ablation studies on the IHC_2021 dataset. The results, summarized in Table 7, reveal several key insights:

Table 7.

Ablation study of key components and hyperparameters on the IHC_2021 single-label dataset

| Model variant/hyperparameter | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL-ProteinFormer (Full Model) | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| - w/o Residual Attention | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| - w/o ConvFFN (replaced with MLP) | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| - w/o ImageNet Pre-training | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

Scaling Size:

|

0.68 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

Scaling Size:

|

0.76 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| Transformer Depth: 1 Layer | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| Transformer Depth: 3 Layers | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

First, the choice of image size significantly impacts performance. Scaling images to  pixels yielded the best results, offering a optimal trade-off between retaining sufficient biological detail and maintaining computational efficiency. Smaller sizes (

pixels yielded the best results, offering a optimal trade-off between retaining sufficient biological detail and maintaining computational efficiency. Smaller sizes ( ) led to a substantial loss of information, while larger sizes (

) led to a substantial loss of information, while larger sizes ( ) did not provide commensurate performance gains given the increased computational cost.

) did not provide commensurate performance gains given the increased computational cost.

Second, the depth of the transformer module is crucial. A stack of 6 attention layers achieved the highest Accuracy, indicating that this depth is sufficient to model the complex relationships in protein images without overfitting the limited data.

Most critically, the ablation study confirms the necessity of our two key innovations. The Residual Attention mechanism stabilizes training by simplifying the learning objective, while the ConvFFN module effectively reintroduces spatial inductive biases that are lost during tokenization. The combination of both techniques contributes significantly to the final performance, as removing either component results in a noticeable drop in the  -score.

-score.

Computational efficiency

In response to computational efficiency analysis, we provide a comparative discussion based on model parameter counts, a fundamental metric of model complexity and storage footprint.

Nevertheless, a comparison of parameter counts offers valuable insights. The ResNet-50 baseline, as expected, has the lowest parameter count. The Swin-Transformer introduces a modest increase due to its self-attention mechanism. Our ProteinFormer model has higher complexity, which is attributed to its multi-scale feature fusion design. Crucially, GL-ProteinFormer, designed for efficiency on small datasets, maintains a parameter count comparable to Swin-T, while achieving significantly better Accuracy on the IHC_2021 dataset (81% vs. 75%  -score, Table 6). This suggests that our architectural improvements do not come with an excessive increase in model complexity. Moreover, our model is compatible with and can be efficiently deployed on our high-performance computing cluster equipped with NVIDIA A100 GPUs, which facilitates large-scale protein image analysis.

-score, Table 6). This suggests that our architectural improvements do not come with an excessive increase in model complexity. Moreover, our model is compatible with and can be efficiently deployed on our high-performance computing cluster equipped with NVIDIA A100 GPUs, which facilitates large-scale protein image analysis.

Visual feature analysis

The confusion matrix in Fig. 3A illustrates the multi-class classification performance of ProteinFormer. It is evident that the ProteinFormer model excelled in predicting protein subcellular localization, accurately identifying the majority of proteins such as actin microfilaments, centrosomes, Golgi apparatus, intermediate filaments, microtubules, nuclear membranes, nucleolus and nuclei. However, it struggled with proteins located on the endoplasmic reticulum and vesicles by frequently misassigning them to the subcellular location of cell fluid and vesicles respectively. Additionally, it often misclassified membrane-bound proteins as being present in the cell fluid compartment.

Fig. 3.

Confusion matrix and weight visualization. A Confusion matrix of the ProteinFormer model on the Cyto_2017 dataset test set. B Confusion matrix of the GL-ProteinFormer model on the IHC_2021 dataset single-label test set. C Visualization of the attention weights learned by the ProteinFormer model. The example images are sourced from the Cyto_2017 dataset, showcasing proteins localized to the Nucleus (top) and Mitochondria (bottom). Regions receiving higher attention by the model are represented by warmer colors (closer to red), while regions with lower attention are indicated by cooler colors (closer to blue). This demonstrates the model’s ability to focus on biologically relevant regions containing the target protein, rather than irrelevant background areas

The Attention mechanism within the transformer model enables automatic learning of important location information while distinguishing important location features and assigning corresponding weights accordingly. This mechanism also facilitates understanding of relationships between adjacent locations which aids categorical markers in comprehending object positions and relative relationships. Such relationships assist classification markers in capturing object features more effectively while reducing focus on background elements thereby enhancing classification performance. The visualization result depicted in Fig. 3C demonstrates how ProteinFormer allocates attention to regions containing proteins rather than irrelevant background areas during classification tasks; regions receiving higher attention are represented by colors closer to red whereas those receiving lower attention are indicated by colors closer to blue.

The Fig. 3B illustrates the estimated confusion matrix of model for multi-class protein prediction. Remarkably, this model demonstrates exceptional performance in accurately predicting proteins localized in the nucleolus and cytoskeleton. However, it encounters challenges when assigning proteins located in the Golgi apparatus and mitochondria, often resulting in misclassifications to subcellular locations such as vesicles, end reticulum, mitochondrial regions, and nucleolar areas.

Conclusion

Current state-of-the-art models for protein subcellular localization prediction primarily rely on deep learning techniques. However, these models are predominantly based on CNNs, which inherently struggle to capture global contextual information. To address this limitation, we propose an innovative approach integrating the transformer architecture for protein subcellular localization.

Given the substantial data requirements for pre-training transformer models effectively, we first investigated scenarios with sufficient data. We introduced ProteinFormer, a novel model that extracts multi-scale feature representations. These features are then processed by a transformer-based neural network to integrate global information comprehensively. This design overcomes the inability of prior CNN-centric methods to model long-range dependencies. We conducted ablation studies to optimize the model’s hyperparameters and rigorously evaluated its performance. Comparative assessments against mainstream methods and human expert benchmarks demonstrate ProteinFormer’s superior localization accuracy.

To enhance transformer applicability in data-scarce scenarios, we further refined its architecture. We developed GL-ProteinFormer, grounded in residual learning principles. This model simplifies attention mapping by learning attention residuals rather than complete attention matrices. Additionally, we redesigned the transformer’s FFN module, replacing fully connected layers with convolutional layers (ConvFFN). This modification introduces essential visual inductive biases (e.g., locality, translation invariance), reducing dependency on large datasets. Extensive ablation and comparative experiments confirm GL-ProteinFormer’s efficacy under data constraints, showing improved classification accuracy over existing methods and offering potential for small-sample learning.

Although our method achieves better results, it still has the following shortcomings:

Dataset imbalance: Small datasets exhibit severe sample imbalance, necessitating manual intra-class partitioning instead of random splits into training, validation, and test sets. We hope that future research focuses on and addresses the problem of dataset category imbalance.

Transfer learning adaptation: Protein microscopy images (often grayscale or 4-channel CMYK) differ significantly from 3-channel natural images. While ImageNet pre-training weights improve performance, more tailored transfer learning techniques for protein microscopy images require further exploration.

Small-sample learning efficacy: Although GL-ProteinFormer—via residual attention and ConvFFN-induced visual biases—outperforms mainstream methods, its accuracy lags behind models trained on large datasets. Additional small-sample learning approaches should be explored to enhance performance on limited data. Therefore, we plan to try other small-sample learning methods to further improve the classification accuracy on small datasets.

Building upon the current work, key avenues for future research include: addressing dataset imbalance in small samples through targeted strategies to reduce manual partitioning; exploring domain-specific pre-training on large biological image datasets (e.g., expanded HPA subsets) to better adapt to protein microscopy images; and integrating advanced small-sample learning techniques with GL-ProteinFormer to narrow the performance gap with large-dataset models, enhancing practical applicability in proteomics research.

Authors' contributions

Xinyi An and Huiping Liao: model building, designed and performed the experiments, drafted the paper, discussion. Wanqiang Chen and Yixin Li: discussion, proofread, revised, and wrote the final version of the paper. Guosheng Han: conceived the study, provided expertise, critical guidance and thought leadership, reviewed and revised the manuscript. Xianhua Xie: provided resources, developed methodology, reviewed and revised the manuscript. Cuixiang Lin:provided resources, developed methodology, reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hunan Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2023SK2051),

National Natural Science Foundation of China (12361099),

and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20212BAB201006).

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available. The Cyto 2017 dataset was obtained from the 2017 Cyto Challenge organized by the ISAC, which is part of the HPA. The IHC 2021 dataset was constructed based on IHC images from the HPA Tissue Atlas. All HPA-related data can be accessed via the official website http://www.proteinatlas.org.

Code availability

The source code for ProteinFormer and GL-ProteinFormer is available at: https://github.com/hangslab/ProteinFormer.

To ensure full reproducibility, we are currently preparing the final pre-trained model weights and detailed environment configuration files. These will be made publicly available upon acceptance of this manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xinyi An and Yixin Li these authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Guosheng Han, Email: hangs@xtu.edu.cn.

Xianhua Xie, Email: xxianhua@sina.com.

References

- 1.Christopher JA, Geladaki A, Dawson CS, Vennard OL, Lilley KS. Subcellular transcriptomics and proteomics: a comparative methods review. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2022;21(2):100185. 10.1016/j.mcpro.2022.100185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu YY, Yang F, Shen HB. Incorporating organelle correlations into semi-supervised learning for protein subcellular localization prediction. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(14):2184–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu YY, Yang F, Zhang Y, Shen HB. An image-based multi-label human protein subcellular localization predictor (ilocator) reveals protein mislocalizations in cancer tissues. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(16):2032–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu L, Yang J, Shen HB. Multi-label learning for prediction of human protein subcellular localizations. Protein J. 2009;28:384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou KC. Advances in predicting subcellular localization of multi-label proteins and its implication for developing multi-target drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(26):4918–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo T, Steen JA, Mann M. Mass-spectrometry-based proteomics: from single cells to clinical applications. Nature. 2025;638(8052):901–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S, Yang JS, Shin YE, Park J, Jang SK, Kim S. Protein localization as a principal feature of the etiology and comorbidity of genetic diseases. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7(1):494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florindo C, Ferreira BI, Serrão SM, Tavares ÁA, Link W. Subcellular protein localisation in health and disease. eLS. 2016:1–9. 10.1002/9780470015902.a0026400.

- 9.Samson ABP, Chandra SRA, Manikant M. A deep neural network approach for the prediction of protein subcellular localization. Neural Netw World. 2021;31:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao Z, Pan G, Sun C, Tang J. Predicting subcellular location of protein with evolution information and sequence-based deep learning. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22:515. 10.1186/s12859-021-04437-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakai K, Wei L. Recent advances in the prediction of subcellular localization of proteins and related topics. Front Bioinform. 2022;2:910531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou K, Wang S, Wang Z, Zou H, Yang F. Dual-signal feature spaces map protein subcellular locations based on immunohistochemistry image and protein sequence. Sensors. 2023;23(22):9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao H, Zou Y, Wang J, Wan S. A review for artificial intelligence based protein subcellular localization. Biomolecules. 2024;14(4):409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu GH, Zhang BW, Qian G, Wang B, Mao B, Bichindaritz I. Bioimage-based prediction of protein subcellular location in human tissue with ensemble features and deep networks. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinf. 2020;17(6):1966–80. 10.1109/TCBB.2019.2911566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding J, Xu J, Wei J, Tang J, Guo F. A multi-scale multi-model deep neural network via ensemble strategy on high-throughput microscopy image for protein subcellular localization. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;212:118744. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Wei L. Multi-scale deep learning for the imbalanced multi-label protein subcellular localization prediction based on immunohistochemistry images. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(9):2602–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng F, Zhao Z. Machine learning-based prediction of drug-drug interactions by integrating drug phenotypic, therapeutic, chemical, and genomic properties. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e2):e278–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zupan J. Introduction to artificial neural network methods: what they are and how to use them. Acta Chim Slov. 1994;41(3):327. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotsiantis SB. Decision trees: a recent overview. Artif Intell Rev. 2013;39(4):261–83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigatti SJ. Random forest. J Insur Med. 2017;47(1):31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Velliste M, Murphy RF. Automated interpretation of subcellular patterns in fluorescence microscope images for location proteomics. Cytometry A. 2006;69(7):631–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillani M, Pollastri G. Protein subcellular localization prediction tools. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;23:1–10. 10.1016/j.csbj.2024.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillani M, Pollastri G. Impact of alignments on the accuracy of protein subcellular localization predictions. Proteins. 2025;93(3):745–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwendi C, Moqurrab SA, Anjum A, Khan S, Mohan S, Srivastava G. A semantic privacy-preserving framework for unstructured medical datasets. Comput Commun. 2020;161:160–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xing F, Xie Y, Su H, Liu F, Yang L. Deep learning in microscopy image analysis: a survey. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2017;29(10):4550–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan DP, Winsnes CF, Åkesson L, Hjelmare M, Wiking M, Schutten R, et al. Deep learning is combined with massive-scale citizen science to improve large-scale image classification. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(9):820–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraus OZ, Grys BT, Ba J, Chong Y, Frey BJ, Boone C, et al. Automated analysis of high-content microscopy data with deep learning. Mol Syst Biol. 2017;13(4):924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang HY, Wu CL. Deep learning method to classification Human Protein Atlas. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-TW). IEEE; 2019. pp. 1–2.

- 29.Aggarwal S, Gupta S, Gupta D, Gulzar Y, Juneja S, Alwan AA, et al. An artificial intelligence-based stacked ensemble approach for prediction of protein subcellular localization in confocal microscopy images. Sustainability. 2023;15(2):1695. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu Y, Lei H, Shen HB, Yang Y. A self-supervised pre-training method for enhancing the recognition of protein subcellular localization in immunofluorescence microscopic images. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(2):bbab605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thumuluri V, Almagro Armenteros JJ, Johansen AR, Nielsen H, Winther O. Multi-label subcellular localization prediction using protein language models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W228-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Høie MH, Kiehl EN, Petersen B, Nielsen M, Winther O, Nielsen H, et al. Accurate and fast prediction of protein structural features by protein language models and deep learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W510–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Wang Y, Ding P, Li S, Yu X, Yu B. Identification of multi-label protein subcellular localization by interpretable graph attention networks and feature-generative adversarial networks. Comput Biol Med. 2024;170:107944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Digre A, Lindskog C. The human protein atlas—spatial localization of the human proteome in health and disease. Protein Sci. 2021;30(1):218–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Zheng L, Jiang W, LU M, XU H, DAI H, et al. A deep learning-based prediction of protein subcellular localization for promoting multi-directional pharmaceutical research. J Pharm Anal. 2025;15(1):101255. 10.1016/j.jpha.2024.101255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Husain SS, Ong EJ, Minskiy D, Bober-Irizar M, Irizar A, Bober M. Single-cell subcellular protein localisation using novel ensembles of diverse deep architectures. Commun Biol. 2023;6:522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Zhu XL, Bao LX, Xue MQ, Xu YY. Automatic recognition of protein subcellular location patterns in single cells from immunofluorescence images based on deep learning. Brief Bioinform. 2023;24(1):bbac609. 10.1093/bib/bbac609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duhan N, Kaundal R. Atsubp-2.0: an integrated web server for the annotation of Arabidopsis proteome subcellular localization using deep learning. Plant Genome. 2025;18(1):e20536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao Z, Xu K, Fan N. Swin transformer assisted prior attention network for medical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence. New York; Association for Computing Machinery: 2022. p. 491–7.

- 40.Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, Dehghani M, Minderer M, Heigold G, Gelly S, Uszkoreit J, Houlsby N. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

- 41.Jha K, Saha S, Karmakar S. Prediction of protein-protein interactions using vision transformer and language model. ACM-IEEE Trans Comput Biol Bioinforma. 2023;20(1):1–13. 10.1109/TCBB.2023.3334622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng W, Wang Y, Wang S, Fang Z, Li Y, Li Y, et al. Deepsp: a deep learning framework for spatial proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2023;22(7):2186–98. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang Z, Zhu X, Zhang X, Li Y, Li M, Hu X, et al. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. 2024. arXiv:2401.09417.

- 44.Li K, Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Wang L, Gao X. GraphMamba: An Efficient Graph Structure Learning Vision Mamba for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Baai Academic Repository; 2024.

- 45.Silver D, Hasselt H, Hessel M, Schaul T, Guez A, Harley T, et al. The predictron: End-to-end learning and planning. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2017. pp. 3191–3199.

- 46.Tárnok A. Cytometry is expanding. Cytometry A. 2017;91(7):649–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moroki T, Matsuo S, Hatakeyama H, Hayashi S, Matsumoto I, Suzuki S, et al. Databases for technical aspects of immunohistochemistry: 2021 update. J Toxicol Pathol. 2021;34(2):161–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Piscataway; IEEE: 2021. p. 10012–22.

- 49.Rumetshofer E, Hofmarcher M, Röhrl C, Hochreiter S, Klambauer G. Human-level protein localization with convolutional neural networks. In: International Conference on Learning Representations. 2018. https://www.OpenReview.net.

- 50.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway; IEEE: 2016. p. 770–8.

- 51.Chen H, Zhang Y, Li W, Wang X, Liu B. Unified protein localization via cross-modal pre-training. Nat Mach Intell. 2025. 10.1038/s42256-025-00985-4.

- 52.Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway; IEEE: 2015. p. 3431–40 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Kraus OZ, Ba JL, Frey BJ. Classifying and segmenting microscopy images with deep multiple instance learning. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(12):i52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Godinez WJ, Hossain I, Lazic SE, Davies JW, Zhang X. A multi-scale convolutional neural network for phenotyping high-content cellular images. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(13):2010–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, Weinberger KQ. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway; IEEE: 2017. p. 4700–8.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are publicly available. The Cyto 2017 dataset was obtained from the 2017 Cyto Challenge organized by the ISAC, which is part of the HPA. The IHC 2021 dataset was constructed based on IHC images from the HPA Tissue Atlas. All HPA-related data can be accessed via the official website http://www.proteinatlas.org.

The source code for ProteinFormer and GL-ProteinFormer is available at: https://github.com/hangslab/ProteinFormer.

To ensure full reproducibility, we are currently preparing the final pre-trained model weights and detailed environment configuration files. These will be made publicly available upon acceptance of this manuscript.