Abstract

Background

Migraine imposes a substantial global burden, with unmet patient-centered therapeutic needs. Rimegepant, a CGRP receptor antagonist, has trial-proven efficacy, but real-world evidence for its dual acute and preventive use in Chinese migraine populations is limited. This study evaluated its effectiveness in Chinese patients using patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

A multicenter, single-arm, prospective, non-interventional observational study was conducted across five hospitals in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China. A total of 120 adult migraine patients who were prescribed rimegepant for either acute (AT) or preventive treatment (PT) were enrolled. Patient-reported outcomes were assessed at baseline and after 4 weeks using Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), the European Five-Dimension Five-Level Health Scale (EQ-5D-5L) and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire - General Health (WPAI-GH). We employed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for within-group comparisons of pre- and post-treatment scale scores, with statistically significant defined as a two-tailed p-value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 120 migraine patients meeting all inclusion criteria were enrolled but 12 potential participants (10.0%) did not initiate rimegepant therapy. The study was completed by 108 patients (median age 37.0 (31.5,46.0) years; 83% female), including 89 in the AT group and 19 in the PT group. After 4 weeks, both groups showed significant improvements. In the AT group, the HIT-6 score decreased by 4.8 (95% CI: -6.1, -3.0), while TSQM scores increased in Effectiveness (20.6; 95% CI: 14.3, 26.8), Side Effects (12.6; 95% CI: 6.8, 18.5), and Global Satisfaction (16.2, 95% CI: -10.8, 21.5); for all comparisons to baseline, P < 0.0001. The PT group also showed an improvement in the HIT-6 (-5.8 [95% CI: -9.5, -2.2]) and improvements in TSQM (11.4 [95% CI: -0.8, 23.6] for Effectiveness, 13.2 [95% CI: -0.1, 26.4] for Side Effects,12.0 [95% CI: 0.2, 23.8] for Global Satisfaction). Both the AT and PT groups reported improvement in EQ-5D-5L VAS scores (3.6 [95% CI: 1.0, 6.2] and 7.6 [95% CI: 1.8, 13.5]) and improvement in WPAI-GH measures, including presenteeism (-10.6 and − 26.4) and overall work impairment (-11.3 and − 22.4); for all comparisons to baseline, P < 0.05). A clinically relevant improvement (≥ 6-point reduction in HIT-6 scores) was achieved by 52.6% of PT group and 34.1% of AT group. The PT group was relatively small, and due to the limited duration of follow-up, it may have demonstrated preliminary preventive effects.

Conclusions

Rimegepant demonstrated improvements across multiple patient-centered outcomes, including headache-related impacts (HIT-6), treatment satisfaction (TSQM), quality of life (EQ-5D-5L), functional capacity and work productivity (WPAI). Therapeutic benefits were observed in both AT and PT, with the PT group showing preliminary evidence of preventive effects, further supporting rimegepant’s dual indications in migraine management.

Trial registration

The study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06221267).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s10194-025-02197-8.

Keywords: CGRP receptor antagonist, Real-world data, Effectiveness, Migraine, Observational study, Therapeutic optimization

Introduction

Migraine is a highly prevalent and disabling neurological disorder, affecting nearly one billion people worldwide and peaking in mid-adulthood [1, 2]. In China, the 12-month prevalence reaches 9.3%, corresponding to approximately 130 million individuals [2, 3]. The disorder imposes a substantial disease burden through reduced quality of life, impaired productivity, and years lived with disability, making migraine a major public health concern in China and globally [2].

Rimegepant is an orally administered small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist (gepant) that exerts therapeutic effects by blocking CGRP ligand binding to their receptors [4, 5]. Several large-scale clinical trials have validated the efficacy and safety of rimegepant in treating migraine [6–8]. In May 2021, the indication for rimegepant was expanded to include the preventive treatment for episodic migraine in adults in the US. Currently, various international guidelines endorse rimegepant for both acute and preventive treatment of migraine [9–11]. However, these trials were conducted with strict inclusion criteria, which may limit the generalizability to real-world clinical settings—particularly for Chinese migraine patients.

Although there is existing clinical trial data demonstrate the efficacy of rimegepant in a Chinese population, data on its real-world effectiveness in alleviating migraines, improving QoL and patient-reported satisfaction remain scarce. We conducted a prospective, multicenter, single-arm, pre-post observational study to evaluate the effectiveness of rimegepant for both acute and preventive migraine management. Although the absence of a control group limits causal inference, the study provides a patient-centered evaluation of treatment impact under real-world clinical conditions based on patient-reported outcomes (PROs). At the time of study initiation, rimegepant had not been approved in Mainland China but was accessible through the “Hong Kong and Macao Medicine and Equipment Connect” policy in designated Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) hospitals, enabling access to innovative therapies prior to official New Drug Application (NDA) approval.

Methods

Study design

This is a prospective, multicenter, single-arm, non-interventional observational study that consecutively enrolled 120 adult migraine patients (aged >18 years) who were prescribed rimegepant (for acute or preventive treatment) from outpatient headache clinics across five hospitals in the GBA, China. The index date was defined as the initiation of rimegepant treatment, with all patients completing a standardized 4-week follow-up period to assess treatment outcomes. The study was preregistered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT06221267) on January 24, 2024, initiated on January 26, 2024, and concluded on June 30, 2024.

Participants

Patients were eligible for enrollment if they: (1) were ≥ 18 years of age; (2) had a confirmed diagnosis of migraine with or without aura according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3); and (3) were prescribed rimegepant for migraine treatment by their physicians. Patients were excluded from this study if they were treated with any -gepant within one month prior to the index date or with a diagnosis of secondary headaches or known allergy to the study medication. Patients were also excluded for severe communication disorders (e.g., vision, hearing, language, cognitive, memory, or consciousness impairments), uncontrolled/unstable cardiovascular diseases, acute cardiovascular events within 6 months before the index date (e.g., myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, percutaneous coronary intervention, cardiac surgery, stroke, and transient ischemic attack), or current pregnancy/lactation. Patient eligibility was independently assessed by two neurologists.

Procedures

Following a clinical assessment, the physicians determined the appropriate treatment regimen, either acute or preventive migraine treatment. Dosage regimens followed phase 3 trial recommendations: 75 mg as-needed for acute treatment (AT) and 75 mg every-other-day for preventive treatment (PT) [4, 6]. The maximum daily dosage was restricted to 75 mg within 24 h. Concomitant use of other migraine treatments was permitted. The medication regimen during the observation period will be recorded.

All participants underwent comprehensive baseline evaluation, including documenting of demographic characteristics, medical history, comorbidities, and migraine-specific features: disease burden, ICHD-3 classification, monthly attack frequency, pain severity on NRS, associated symptoms, and menstrual association in female patients. The use of migraine treatments within the 4 weeks prior to patient enrollment was recorded, including the proportion of patients who used migraine medications, and the specific medications administered. Throughout the 4-week study period, trained research staff conducted weekly telephone follow-ups to monitor actual medication usage, concomitant medications, migraine symptoms. Adverse events (AE) occurring during the observation period were reported and managed according to established protocols. Standardized patient-reported outcomes measures were administered at baseline and after 4 weeks of treatment. All clinical research data were securely integrated into a cloud-based electronic data capture (EDC) system with real-time synchronization and encryption.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were changes from baseline in:1. Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), 2. Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), 3. European Quality of Life 5-Dimensions 5-Levels (EQ-5D-5L), and 4. Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-General Health (WPAI-GH) scores after rimegepant treatment.

The HIT-6 is a validated PRO measure assessing headache-related disability across six domains. Each items utilizes a 5-point Likert-scale response option (“never”[6 points], “rarely” [8], “sometimes” [10], “very often” [11], and “always” [13]), yielding a total score ranging from 36 to 78 [12]. Based on previous HIT-6 evaluation criteria, the recommended responder definition for the HIT-6 total score in the chronic migraine (CM) population is a ≥ 6-point decrease [13] and the within-person minimally important change (MIC) in migraine patients has been reported to range from − 2.5 to -6 points [14], we defined a clinically relevant improvement as a ≥ 6-point reduction in total HIT-6 score, which served as an exploratory endpoint for rimegepant treatment response.

The TSQM is a psychometrically validated instrument assessing four key domains of medication experiences: Effectiveness (Q1-Q3), Side Effects (Q4-Q8), Convenience (Q9-Q11), and Global Satisfaction (Q12-Q14). This 14-item questionnaire generates standardized domain scores according to established scoring algorithms (see Table S1 for detailed calculation methods [15]).

To comprehensively assess treatment impact, additional PROs included the EQ-5D-5L and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-General Health (WPAI-GH), which evaluated health-related quality of life (QoL), functional status, and work productivity outcomes (Table S2) [16–18]. Exploratory analyses also included changes in concomitant medication use during the study period.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. For all efficacy endpoints, we calculated mean changes from baseline with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). No imputation was done for missing data. We employed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for within-group comparisons of pre- and post-treatment scale scores, with statistically significant defined as a two-tailed p-value < 0.05. The study population was stratified into two mutually exclusive cohorts based on treatment indication: AT for acute treatment and PT for preventive treatment.

The full analysis set (FAS) included all patients who received at least one dose of rimegepant according to their cohort assignment. Among these, the per-protocol (PP) subset included individuals who completed all scheduled study visits. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using the FAS, while efficacy outcomes were assessed in PP populations. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

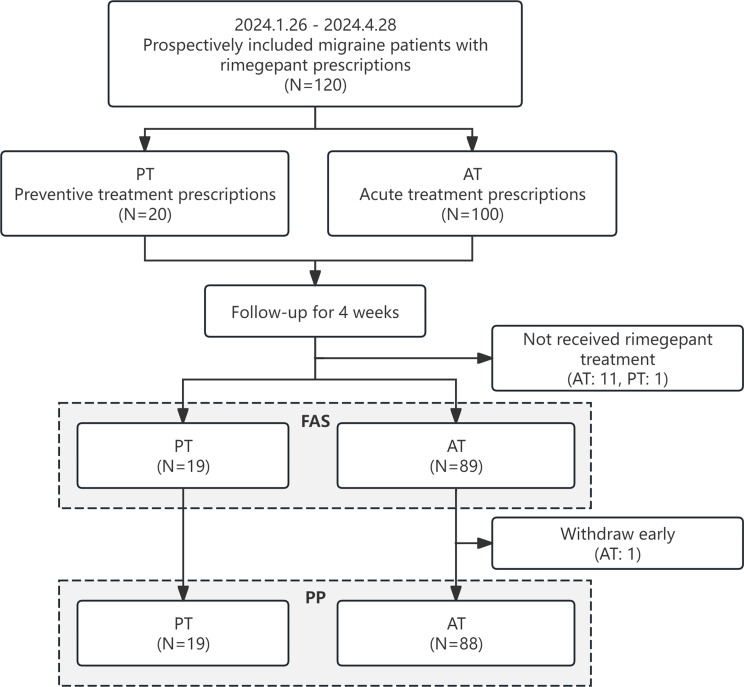

A total of 120 migraine patients meeting all inclusion criteria were enrolled between January 26, 2024, and April 28, 2024. Among these, 100 patients (83.3%) were prescribed rimegepant for AT and 20 (16.7%) for PT. Twelve potential participants (10.0%) did not initiate rimegepant therapy, and one AT patient discontinued during the 4-week follow-up period due to difficulties in complying with the completion of the questionnaires. The final analysis included 108 participants in the FAS and 107 in the PP population. (Fig. 1). Among patients in the PP population, the mean (SD) number of tablets used was 3.2 (3.1) in the AT group and 9.1 (5.0) in the PT group.

Fig. 1.

Study process. AT, acute treatment; PT, preventive treatment; FAS, full analysis set; PP, per protocol

Baseline characteristics

The overall study population (n = 108) had a median age of 37.0 (31.5, 46.0) years, with 83% being female. Among those female patients (n = 90), 67.8% reported an association between migraine attacks and menstrual cycle. In the AT group (n = 89), patients had a median age of migraine onset of 23.0 (17.0, 28.5) years with a mean of 8.1 (7.9) monthly migraine days (MMD). Migraine without aura was the predominant subtype (78.7%), and 85.4% of patients reported nausea as a common associated symptom. In the PT group (n = 19), the median age of onset was 18.0 (15.0,27.0) years with a higher mean MMD of 15.4 (9.8); chronic migraine was the most frequent diagnosis (57.9%). Frequent concomitant symptoms in this group included nausea (78.9%) and neck stiffness/pain (73.7%). Comorbidities across the entire cohort included insomnia (29.6%), anxiety (17.6%), and depression (8.3%), with lower rates of controlled cardiovascular disease (6.5%) and diabetes (2.8%). In addition, the proportion of patients with anxiety (36.8%) and depression (31.6%) is relatively high in the PT group. A family history of migraine was reported in 47.2% of all patients, with 44.9% in the AT group and 57.9% in the PT group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (FAS)

| Total (N = 108) | AT (N = 89) | PT (N = 19) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Median (Q1, Q3), years | 37.0 (31.5,46.0) | 37.0 (32.0,45.0) | 34.0 (29.0,54.0) | 0.6025 |

| Age groups, No. (%) | 0.4254 | |||

| 18–30 years | 24 (22.2) | 18 (20.2) | 6 (31.6) | |

| 31–45 years | 56 (51.9) | 49 (55.1) | 7 (36.8) | |

| 46–60 years | 21 (19.4) | 16 (18.0) | 5 (26.3) | |

| ≥ 61 years | 7 (6.5) | 6 (6.7) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Women, No. (%) | 90 (83.3) | 75 (84.3) | 15 (78.9) | 0.5177 |

| Menstrually-related migrainea, No. / total No. (%) | 61/90 (67.8) | 53/75 (70.7) | 8/15 (53.3) | 0.2227 |

| Age of migraine onset, Median (Q1, Q3), years | 22.0 (17.0,28.0) | 23.0 (17.0,28.5) | 18.0 (15.0,27.0) | 0.2044 |

| MMD, Mean (SD), days | 9.4 (8.7) | 8.1 (7.9) | 15.4 (9.8) | 0.0026 |

| No. (%) of MMD | 0.0142 | |||

| ≤ 3 | 29 (26.9) | 26 (29.2) | 3 (15.8) | |

| [4,14] | 55 (50.9) | 48 (53.9) | 7 (36.8) | |

| ≥ 15 | 24 (22.2) | 15 (16.9) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Migraine type, No. (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Without aura | 76 (70.4) | 70 (78.7) | 6 (31.6) | |

| With aura | 12 (11.1) | 10 (11.2) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Chronic | 19 (17.6) | 8 (9.0) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Others | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0(0.0) | |

| Concomitant symptom, No. (%) | ||||

| Nausea | 91 (84.3) | 76 (85.4) | 15 (78.9) | 0.4946 |

| Vomit | 55 (50.9) | 44 (49.4) | 11 (57.9) | 0.5033 |

| Photophobia | 65 (60.2) | 53 (59.6) | 12 (63.2) | 0.7706 |

| Phonophobia | 64 (59.3) | 52 (58.4) | 12 (63.2) | 0.7032 |

| Neck stiffness or pain | 59 (54.6) | 45 (50.6) | 14 (73.7) | 0.0661 |

| Concomitant diseases, No. (%) | ||||

| Controlled cardiovascular disease | 7 (6.5) | 5 (5.6) | 2 (10.5) | 0.6040 |

| Diabetes | 3 (2.8) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (5.3) | 0.4437 |

| Depression | 9 (8.3) | 3 (3.3) | 6 (31.6) | 0.0008 |

| Anxiety | 19 (17.6) | 12 (13.5) | 7 (36.8) | 0.0403 |

| Insomnia | 32 (29.6) | 25 (28.1) | 7 (36.8) | 0.4482 |

| Family history of migraine, No. (%) | 51 (47.2) | 40 (44.9) | 11 (57.9) | 0.3047 |

| Parents | 47 (43.5) | 38 (42.7) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Grandparents | 8 (7.4) | 6 (6.7) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Siblings | 7 (6.5) | 3 (3.4) | 4 (21.1) |

FAS, full analysis set; SD, standard deviation; MMD, total monthly migraine days

aThe prevalence of menstrually-related migraine was evaluated based on self-reported data among female patients

Values in bold are statistically significant

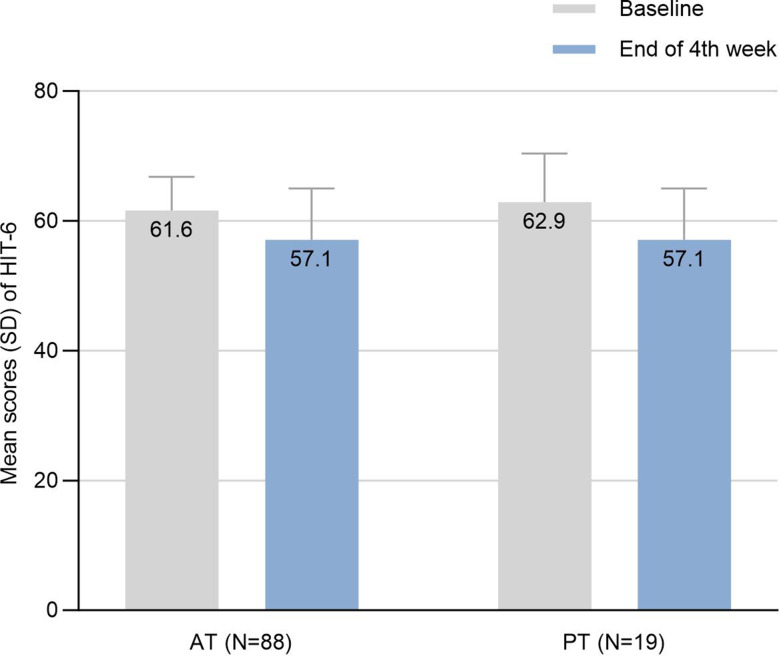

Headache impact outcomes: HIT-6

Both treatment cohorts demonstrated significant reductions in HIT-6 scores following 4-week of rimegepant therapy (Fig. 2). In the AT group, mean (SD) HIT-6 scores decreased from 61.6 (5.2) at baseline to 57.1 (7.9) post treatment (mean difference − 4.6; 95% CI: -6.1 to -3.0; P < 0.0001) as shown in Table 2. The PT group showed comparable improvement, with scores declining from 62.9 (7.5) to 57.1 (7.9) (mean difference, -5.8; 95% CI: -9.5 to -2.2; P = 0.0022). A clinically relevant improvement (≥ 6-point reduction in HIT-6 scores) was achieved by 52.6% of PT group and 34.1% of AT group. While the mean HIT-6 improvement did not reach the 6-point threshold, both AT and PT groups showed statistically significant improvements.

Fig. 2.

Mean scores and changes of HIT-6. SD, standard deviation; HIT-6, Headache Impact Test; AT, acute treatment; PT, preventive treatment

Table 2.

Variation in scale scores before and after Rimegepant treatment (PP)

| AT (N = 88) | PT (N = 19) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean changes (95% CI) | P | Mean changes (95% CI) | P | |

| HIT-6 | -4.6 (-6.1, -3.0) | < 0.0001 | -5.8 (-9.5, -2.2) | 0.0022 |

| TSQMa | ||||

| Effectiveness | 20.6 (14.3, 26.8) | < 0.0001 | 11.4 (-0.8, 23.6) | 0.069 |

| Side effects | 12.6 (6.8, 18.5) | < 0.0001 | 13.2 (-0.1, 26.4) | 0.044 |

| Convenience | 4.3 (0.4, 8.2) | 0.058 | 4.4 (-4.8, 13.6) | 0.383 |

| Global satisfaction | 16.2 (10.8, 21.5) | < 0.0001 | 12.0 (0.2, 23.8) | 0.048 |

| EQ-5D-5L | ||||

| VAS | 3.6 (1.0, 6.2) | 0.019 | 7.6 (1.8, 13.5) | 0.011 |

| Utility value | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.03) | 0.22 | 0.06 (0.01, 0.10) | 0.024 |

| WPAI-GH | ||||

| Absenteeismb | -4.2 (-8.1, -0.3) | 0.054 | -1.4 (-15.2, 12.4) | 0.81 |

| Presenteeismc | -10.6 (-18.7, -2.5) | 0.018 | -26.4 (-38.9, -13.9) | 0.0020 |

| Overall work impairmentc | -11.3 (-19.8, -2.9) | 0.021 | -22.4 (-35.0, -9.7) | 0.0020 |

| Activity impairment | -12.3 (-18.6, -6.0) | 0.0003 | -9.0 (-24.1, 6.2) | 0.16 |

PP, per-protocol; CI, confidence interval; AT, acute treatment; PT, preventive treatment; HIT-6, Headache Impact Test; TSQM, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication; EQ-5D-5L, European Five Dimensions Five Health Scale; VAS, visual analogue scale; WPAI-GH, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire - General Health

aTSQM: 106 cases were included in the analysis, including 87 in AT and 19 in PT;

bAbsenteeism: 67 cases were included in the analysis, including 55 in AT and 12 in PT;

cPresenteeism and Overall work impairment: 66 cases were included in the analysis, including 55 in AT and 11 in PT

Subgroup analyses of all patients revealed differential responses based on migraine characteristics: patients with aura showed higher response rates (50.0%) compared to those without aura (34.7%) or with chronic migraine (42.1%). Stratification by monthly migraine days (MMD) demonstrated a greater response in the subgroup with 4–14 MMDs (50.1%), exceeding responses in ≤ 3 MMDs (24.1%) and ≥ 15 MMDs (21.7%) subgroups. Among patients with menstrually-related migraine, response rates were 37.7% in the AT group and 50.0% in the PT group (Table 3).

Table 3.

The proportions of patients with ≥ 6-point improvement in HIT-6 (PP)

| Total (N = 107) | AT (N = 88) | PT (N = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, No. (%) | 40 (37.4) | 30 (34.1) | 10 (52.6) |

| Migraine type, No. / total No. (%) | |||

| Without aura | 26/75 (34.7) | 22/69 (31.9) | 4/6 (66.7) |

| With aura | 6/12 (50.0) | 5/10 (50.0) | 1/2 (50.0) |

| Chronic | 8/19 (42.1) | 3/8 (37.5) | 5/11 (45.5) |

| Others | 0/1 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 0/0 (NA) |

| MMD, No. / total No. (%) | |||

| ≤ 3 | 7/29 (24.1) | 6/26 (23.1) | 1/3 (33.3) |

| [4, 14] | 28/55 (50.1) | 22/48 (45.8) | 6/7 (85.7) |

| ≥ 15 | 5/23 (21.7) | 2/14 (14.3) | 3/9 (33.3) |

| Menstrually-related migraine, No. / total No. (%) | 24/61 (39.3) | 20/53 (37.7) | 4/8 (50.0) |

a. The prevalence of menstrually-related migraine was evaluated based on self-reported data among female patients

Treatment satisfaction: TSQM

After 4 weeks of rimegepant treatment, among all participants (n = 106), the mean (SD) TSQM scores were highest for the side effects domain (94.3 [16.5]), followed by convenience (76.6 [16.5]), and effectiveness (60.1 [23.4]). Based on our survey, 88.9% of the participants(n = 96) had experienced dissatisfaction with the efficacy or poor experiences with prior treatments before enrollment. We compared TSQM scores at baseline and after treatment and found that both treatment cohorts showed improvements following rimegepant therapy. In the AT group, effectiveness scores significantly increased from 41.3 (21.9) at baseline to 61.8 (23.2) after 4 weeks (mean change 20.6; 95%CI: 14·3 to 26.8; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). The PT group showed a comparable numerical improvement from 40.9 (18.1) at baseline to 52.4 (23.2) post-treatment (mean change 11.4; 95% CI: -0.8, 23.6), though this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.069).

Fig. 3.

Mean scores and changes of TSQM. (A) Effectiveness. (B) Side effects. (C) Convenience. (D) Global satisfaction. SD, standard deviation; TSQM, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication; AT, acute treatment; PT, preventive treatment

Significant improvements were observed in both groups for the “Side Effects” and “Global Satisfaction” domains. The AT group demonstrated a mean change of 12.6 (95% CI: 6.8 to 18.5; P < 0.0001) for Side Effects and 16.2 (95% CI: 10.8 to 21.5; P < 0.0001) for Global Satisfaction. Corresponding changes in the PT group were 13.2 (95% CI: -0.1 to 26.4; P = 0.044) and 12.0 (95% CI: 0.2 to 23.8; P = 0.048), respectively. While Convenience scores showed numerical increase in both cohorts, these changes did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

Health-related quality of life: EQ-5D-5L

Following rimegepant therapy, all treatment groups demonstrated significant improvements in quality of life as measured by the EQ-5D-5L scale, except that the utility value in the AT group did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4).The visual analogue scale (VAS) scores showed significant increases in both the AT group (mean change 3.6, 95% CI: 1.0 to 6.2; P = 0.019) and the PT group (mean change 7.6; 95% CI: 1.8 to 13.5; P = 0.011). The utility value improved by 0.01 (95% CI: -0.01 to 0.03, p = 0.218) in the AT group, which was not statistically significant. However, the PT group exhibited a statistically significant improvement in utility value (mean change 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.10; P = 0.024), as shown in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Mean scores and changes of EQ-5D-5L. (A) VAS. (B) Utility value. SD, standard deviation; EQ-5D-5L, European Five Dimensions Five Health Scale; VAS, visual analogue scale; AT, acute treatment; PT, preventive treatment

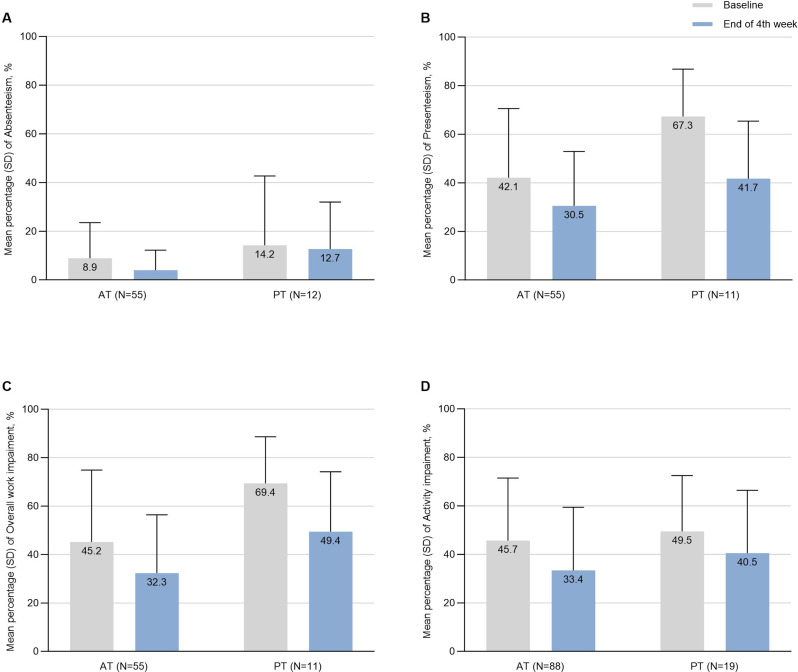

Quality of work: WPAI-GH

In the analysis of WPAI-GH scales, the AT group showed significant mean improvements in presenteeism (-10.6 [95% CI: -18.7 to -2.5]; P = 0.018), overall work impairment (-11.3 [95% CI: -19.8 to -2.9]; P = 0.021), and activity impairment score (-12.3 [95% CI: -18.6 to -6.0]; P = 0.0003). For the PT group, significant improvements were observed in presenteeism (-26.4 [95% CI: -38.9 to -13.9]; P = 0.0020) and overall work impairment (-22.4 [95% CI: -35.0 to -9.7]; P = 0.0020) (Fig. 5). Although decreased scores were noted in absenteeism for both cohorts, the changes were not statistically significant (-4.2 [95% CI: -8.1 to -0.3] for the AT group and − 1.4 [95% CI: -15.2 to 12.4] for the PT group, both P > 0.05). Similarly, no significant changes were observed in the activity impairment for the PT group (-9.0 [95% CI: 24.1 to 6.2], P = 0.16) (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Mean scores and changes of WPAI-GH. (A) Absenteeism. (B) Presenteeism. (C) Overall work impairment. (D) Activity impairment. SD, standard deviation; WPAI-GH, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire - General Health; AT, acute treatment; PT, preventive treatment

Change of concomitant medication

The frequency of concomitant migraine medication administration decreased substantially in both groups. NSAIDS utilization decreased significantly in both the AT group (from 67.0% to 15.9%, P < 0.0001) and PT group (from 36.8% to 0%, P = 0.0034). Similar patterns emerged for other analgesics, including ibuprofen (AT:55.7% to 12.5%; PT: 31.6% to 0%; both P < 0.01), aspirin (AT: 18.2% to 3.4%, P = 0.0016) and paracetamol (AT: 31.8% to 14.8%, P = 0.0075). Triptan utilization patterns showed marked reduction, with overall triptan consumption decreasing from 23.9% to 6.8% (P = 0.0017) in the AT group and from 68.4% to 42.1% (P = 0.10) in the PT group. Significant reductions were notable for specific triptans: rizatriptan (AT: 10.2% to 1.1%; PT: 47.4% to 15.8%, both P < 0.05) and zolmitriptan (AT: 21.6% to 5.7%, P = 0.0021). Caffeine-containing medication also declined significantly in the AT group (18.2% to 3.4%, P = 0.0016). While the PT cohort demonstrated comparable numerical reductions across most medication categories, statistical significance was only achieved for NSAIDs and rizatriptan (Table 4). Moreover, one patient in the PT group received concomitant treatment with Fremanezumab, a CGRP monoclonal antibody.

Table 4.

Concomitant medications at baseline and during Rimegepant treatment (PP)

| AT (N = 88) | PT (N = 19) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | During 4-week treatment | P | Baseline | During 4-week treatment | P | |

| Triptans, No. (%) | 21(23.9) | 6(6.8) | 0.0017 | 13(68.4) | 8(42.1) | 0.10 |

| Zolmitriptan | 19(21.6) | 5(5.7) | 0.0021 | 10(52.6) | 5(26.3) | 0.10 |

| Rizatriptan | 9(10.2) | 1(1.1) | 0.0092 | 9(47.4) | 3(15.8) | 0.036 |

| NSAIDS, No. (%) | 59(67.0) | 14(15.9) | < 0.0001 | 7(36.8) | 0(0.0) | 0.0034 |

| Ibuprofen | 49(55.7) | 11(12.5) | < 0.0001 | 6(31.6) | 0(0.0) | 0.0076 |

| Aspirin | 16(18.2) | 3(3.4) | 0.0016 | 3(15.8) | 0(0.0) | 0.071 |

| Flunarizine, No. (%) | 15(17.0) | 7(8.0) | 0.068 | 7(36.8) | 3(15.8) | 0.14 |

| Paracetamol | 28(31.8) | 13(14.8) | 0.0075 | 8(42.1) | 6(31.6) | 0.50 |

| Caffeine Tablets, No. (%) | 16(18.2) | 3(3.4) | 0.0016 | 3(15.8) | 0(0.0) | 0.071 |

Post hoc analysis of patient-reported outcomes based on monotherapy and concomitant therapy groups

Post hoc analyses were performed to further explore the impact of concomitant medications on the PROs, as shown in Table 5. The results revealed consistent trends in improvement across most of the scales, regardless of whether patients were in the monotherapy or concomitant therapy groups. In the AT group, patients receiving rimegepant monotherapy showed significant improvement in the TSQM dimensions of effectiveness, convenience, and global satisfaction compared to those receiving concomitant therapy (with all P < 0.05). In the PT group, patients on concomitant therapy demonstrated significantly less activity impairment in the WPAI-GH compared to the monotherapy group (P = 0.0369). Notably, no significant statistical differences were observed between the two groups on the remaining scales.

Table 5.

Post hoc analysis of Patient-Reported outcomes based on monotherapy and concomitant therapy groups

| AT (N = 88) | PT (N = 19) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monotherapy | concomitant therapy | monotherapy | concomitant therapy | |||

| Mean changes (95% CI) | P | Mean changes (95% CI) | P | |||

| HIT-6 | -5.3(-7.5, -3.1) | -3.7(-5.9, -1.4) | 0.1977 | -6.3(-13.5,1.0) | -5.5(-10.2, -0.9) | 0.9670 |

| TSQMa | ||||||

| Effectiveness | 29.3(21.7,36.8) | 9.4(-0.4,19.1) | 0.0009 | 7.6(-19.2,34.5) | 14.2(0.6,27.7) | 0.4326 |

| Side effects | 9.7(2.5,16.9) | 16.4(6.4,26.5) | 0.2804 | 6.3(-8.3,20.8) | 18.2(-3.9,40.3) | 0.3672 |

| Convenience | 7.5(3.1,11.9) | 0.1(-6.7,7.0) | 0.0414 | 7.6(-12.2,27.5) | 2.0(-8.6,12.6) | 0.4814 |

| Global satisfaction | 23.9(17.5,30.3) | 6.2(-2.1,14.5) | 0.0002 | 3.6(-22.0,29.1) | 18.2(6.0,30.4) | 0.3209 |

| EQ-5D-5L | ||||||

| VAS | 3.5(0.7,6.4) | 3.6(-1.2,8.5) | 0.4216 | 2.5(-7.2,12.2) | 11.4(3.5,19.2) | 0.1602 |

| Utility value | 0.02(-0.01,0.04) | 0.00(-0.04,0.05) | 0.5621 | 0.04(-0.04,0.12) | 0.07(0.00,0.13) | 0.4923 |

| WPAI-GH | ||||||

| Absenteeismb | -4.6(-9.8,0.7) | -3.6(-9.9,2.7) | 0.8955 | 3.9(-38.2,46.0) | -5.2(-12.3,1.8) | 0.1779 |

| Presenteeismc | -12.4(-24.9,0.0) | -7.7(-16.8,1.3) | 0.7870 | -20.0(-49.1,9.1) | -30.0(-47.7, -12.3) | 0.5004 |

| Overall work impairmentc | -13.5(-26.4, -0.6) | -8.0(-17.6,1.7) | 0.8026 | -8.0(-20.3,4.3) | -30.6(-47.8, -13.4) | 0.0882 |

| Activity impairment | -15.1(-24.7, -5.5) | -8.7(-16.7, -0.7) | 0.4239 | 6.3(-18.6,31.1) | -20.0(-39.5, -0.5) | 0.0369 |

Additionally, we conducted further stratified analyses based on different migraine subtypes for the improvement in HIT-6 scores. The detailed results are shown in Appendix Table S3. Due to the small sample size in the PT group, stratified analyses were only performed in the AT group. In the AT group, the responder rate was 36.7% for monotherapy and 30.8% for concomitant therapy. For subgroups of MMD 4–14, MMD ≥ 15, and MRM, the responder rates were 48.2% vs. 42.9%, 25% vs. 10%, and 41.4% vs. 33.3%, respectively.

Safety

At least one AE was reported in 13.0% of cases (14/108), and the majority were mild in intensity. The most common AEs (≥ 1%) included drowsiness (4.6%, n = 5), skin itching (2.8%, n = 3), stomach discomfort (1.9%, n = 2), and fatigue (1.9%, n = 2). No AEs led to discontinuation of the study drug.

Discussion

Common challenges to managing migraines include inadequate use of preventive strategies and overuse of analgesics, which result in suboptimal care [19–21]. As an oral small-molecule oral CGRP receptor antagonist, rimegepant offers a novel therapeutic approach for migraine patients. A previous study conducted in China demonstrated its efficacy in acute treatment of migraine, with significant reductions in the proportion of patients experiencing moderate-to-severe pain [22]. However, critical evidence gaps persist regarding its application in Chinese populations. First, study on the preventive treatment of migraine with rimegepant is still ongoing in the Chinese population. Second, there is paucity of evidence concerning its impact on patient-reported outcomes (PROs), which are increasingly recognized as crucial indicators of treatment success in migraine management.

This study represents the first real-world assessment of the efficacy and patient-centered benefits in Chinese migraine patients, encompassing both acute and preventive treatment. By incorporating validated PROs (HIT-6, TSQM, EQ-5D-5L, and WPAI-GH), we provide real-world evidence for evaluating treatment benefits and disease burden mitigation [23]. The HIT-6 was used to evaluate rimegepant’s efficacy in Chinese patients across both acute and preventive settings. A key methodological strength is our adoption of a more precise threshold: we defined responders as those with a ≥ 6-point reduction in HIT-6 scores, distinguishing clinically relevant improvement. Our findings (52.6% of patients achieving ≥ 6-point improvement in the PT group) align with U.S. studies showing 46.6–59.9% improvement with CGRP-targeted prevention [24, 25]. A multicenter, open-label rimegepant safety study conducted in China showed that as-needed (PRN) rimegepant reduced monthly migraine days (MMDs) [26]. After 12 weeks of PRN treatment, 41.4% and 20.4% of patients experienced >30% and >50% reductions in MMDs, respectively. The 34% responder rate observed in our AT group may also suggest the potential efficacy of PRN rimegepant in real-world clinical settings.

This study addresses a critical evidence gap by clarifying treatment satisfaction and other outcomes in Chinese adult migraine patients treated with rimegepant. Migraine significantly impairs patients’ quality of life, limiting work participation, social engagement, and family functioning [27]. Our findings also revealed that, compared to baseline, improvements in patients’ quality of life and work productivity were consistent with a trend towards higher patient satisfaction. This may suggest that patients’ treatment adherence and acceptance of rimegepant could be enhanced by improvements in their quality of life, potentially contributing to the long-term effectiveness of the treatment regimen. These findings align with international evidence while providing novel population-specific data. For instance, our observed quality of life improvements mirror those reported in EQ-5D-3L studies, particularly in patients with higher monthly migraine days (MMD) [7]. They also corroborate a head to head trial called CHALLENGE-MIG compared to galcanezumab showing rimegepant’s benefits in role function (restrictive: 26.7; preventive: 20.7) and emotional function (24.6), [28] with our real-world data extending these findings to routine clinical practice.

Subgroup analyses revealed novel insights into rimegepant’s efficacy across migraine subtypes. We observed differential response patterns, with a higher proportion of patients achieving clinically meaningful improvement (HIT-6 reduction ≥ 6 points) among those with migraine with aura in the AT group and migraine without aura in the PT group, which is not previously documented. Given the small sample size, this study represents the first exploratory analysis of rimegepant’s efficacy in menstrually-related migraine (MRM) among Chinese patients. MRM, affecting 42–61% of women with migraine, poses unique challenges due to its severity, duration, and treatment resistance [29]. Our cohort included 66 reproductive-aged women (18–45 years), of whom 67.8% had MRM. Mechanistically, estrogen and oxytocin regulate migraine-related brain regions (e.g., trigeminal ganglia), [30, 31] supporting CGRP-targeted therapies in hormonally influenced migraine. Our results align with reports of comparable -gepant efficacy in perimenstrual vs. non-perimenstrual migraine [32] but extend this to rimegepant specifically, with 37.7% (AT) and 50.0% (PT) response rates in MRM. While promising, these preliminary findings require confirmation in larger controlled studies to optimize MRM treatment protocols.

A registry-based study conducted in Denmark reported a substantial decline in the overuse of acute headache medications following the initiation of rimegepant [33]. Similarly, findings from a long-term rimegepant study indicated a trend toward reduced use of analgesics and antiemetics among patients receiving rimegepant [34]. Consistent with these observations, our study also demonstrated a decrease in the proportion of patients using commonly prescribed acute migraine medications—such as NSAIDs, triptans, paracetamol, and caffeine-containing medication—after four weeks of rimegepant treatment. This reduction may, in part, be attributed to the efficacy of rimegepant. However, the possibility of recall bias or study-related counseling effects cannot be ruled out. And the post hoc analysis may suggest that, regardless of the improvement seen across the scales or the responder rates in different acute treatment subgroups, the efficacy of rimegepant monotherapy is comparable to that of concomitant therapy.

Rimegepant embodies a major advancement in migraine therapy. While its approved indications are well established, evidence regarding its broader therapeutic potential remains insufficient, [35] underscoring the need for further high-quality research.

The incidence of AEs reported in this study was 13.0%, which is lower than that observed in phase III trials, [6, 8] further supporting the favorable safety profile of rimegepant. Moreover, most AEs were mild in severity. These findings provide additional evidence that rimegepant is both safe and well tolerated in the treatment of migraine.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, reliance on patient self-reports for dosage and administration may introduce recall bias or under-reporting. However, we used a per-protocol (PP) analysis set which excluded participants who did not actually initiate rimegepant therapy. Second, the single-arm observational design lacking an external control group restricts our ability to establish causal inference and makes the findings vulnerable to potential confounding factors. While the pre-post comparison design provides valuable real-world evidence, it inherently limits the precision and generalizability of our conclusions compared to randomized controlled trails. Third, the relatively small sample size, particularly in the PT group, increases the susceptibility of our results to outlier effects and reduces statistical power to detect modest treatment effects, potentially resulting in type II errors. Accordingly, the results of the PT group should be interpreted with caution to avoid overinterpretation. Fourth, this study was conducted in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area of China, which may have led to a selection bias toward patients who were more motivated and had relatively higher socioeconomic status, thus limiting the generalizability to the broader Chinese migraine population. Finally, the 4-week follow-up period is relatively short, particularly for the preventive group, where such a timeframe may capture only early treatment effects rather than sustained preventive efficacy. Future studies with larger cohorts and extended follow-up are needed to confirm rimegepant’s long-term therapeutic value in real-world settings.

Conclusions

This was the first multicenter real-world investigation of rimegepant in Chinese migraine patients. After 4 weeks of treatment, improvements were observed across headache impact, treatment satisfaction, quality of life, functional capacity, and work productivity—consistently in both acute and preventive regimens, with the preventive effects remaining preliminary. These findings support rimegepant as a valuable therapeutic option for Chinese migraine patients, addressing current unmet needs. Longer follow-up studies are warranted to strengthen this evidence and evaluate long-term efficacy and safety.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- QoL

Quality of life

- CGRP

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- PROs

Patient-reported outcomes

- GBA

Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area

- NDA

New Drug Application

- ICHD-3

International Classification of Headache Disorders-3

- AT

Acute migraine treatment

- PT

Migraine prevention

- MMDs

Monthly migraine days

- NRS

Numerical rating scale

- EDC

Electronic Data Capture

- HIT-6

Headache Impact Test

- TSQM

Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication

- EQ-5D-5L

The European Five Dimensions Five Health Scale

- WPAI-GH

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire - General Health

- SD

Standard deviation

- CI

Confidence interval

- FAS

Full analysis set

- PP

Per-protocol

Author contributions

YT, JW, JJ (Jingru Jiang), and YX conceived the study and designed the protocol. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. SP, JJ (Jie Jiang), and YZ did the statistical analysis. JW, JJ (Jingru Jiang), SP, ZL, and YL drafted the manuscript, and other authors critically revised the manuscript. JJ (Jie Jiang), YT, and YX accessed and verified the underlying data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Jinan University Project (40123262, File no. 89779897) to Jie Jiang which received funding from Pfizer to support this study as well as the development of this manuscript. In addition, support was provided by grants from the STI 2030 Major Projects (2022ZD0208900), Youth Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 82301568) to Jingru Jiang, STI 2030 Major Projects (2022ZD0211603), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82330099, 82530100) to Yamei Tang, the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province(2023B0303040003) to Yamei Tang, Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (2023A03J0708) to Yamei Tang, National Natural Science Foundation of China (82473563) to Yongteng Xu and Guangzhou Science and Technology Programme (2024A03J0911) to Yongteng Xu.

Data availability

There are ethical restrictions on sharing of de-identified data for this study. The ethics committee has not agreed to the public sharing of data as we do not have the participants’ permission to share their anonymous data.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with standards of Good Clinical Practice as defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation. The central institutional review board or ethics committee approved the study at each site, and patients provided written informed consent before any study procedures.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jinyuan Wang, Jingru Jiang, Sudan Peng, and Jie Jiang co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Yamei Tang, Email: tangym@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yongteng Xu, Email: xuyt5@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. (2017). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 390, 1211–1259. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. (2018). Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology, 17, 954–976. 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30322-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Yu S, Liu R, Zhao G, Yang X, Qiao X, Feng J, Fang Y, Cao X, He M, Steiner T (2012) The prevalence and burden of primary headaches in china: a population-based door-to-door survey. Headache 52:582–591. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.02061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, Conway CM, Forshaw M, Stock EG, Coric V, Lipton RB (2019) Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of Rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 394:737–745. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31606-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, Stock DA, Morris BA, Frost M, Dubowchik GM, Conway CM, Coric V, Goadsby PJ (2019) Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin Gene-Related peptide receptor Antagonist, for migraine. N Engl J Med 381:142–149. 10.1056/NEJMoa1811090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croop R, Lipton RB, Kudrow D, Stock DA, Kamen L, Conway CM, Stock EG, Coric V, Goadsby PJ (2021) Oral Rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 397:51–60. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32544-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, Conway CM, Forshaw M, Stock EG, Coric V, Lipton RB (2019) Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of Rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 394(10200):737–745. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31606-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu S, Kim BK, Guo A, Kim MH, Zhang M, Wang Z, Liu J, Moon HS, Tan G, Yang Q, McGrath D, Hanna M, Stock DA, Gao Y, Croop R, Lu Z (2023) Safety and efficacy of Rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine in China and South korea: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 22(6):476–484. 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00126-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS (2021) The American headache society consensus statement: update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 61:1021–1039. 10.1111/head.14153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eigenbrodt AK, Ashina H, Khan S, Diener HC, Mitsikostas DD, Sinclair AJ, Pozo-Rosich P, Martelletti P, Ducros A, Lantéri-Minet M, Braschinsky M, Del Rio MS, Daniel O, Özge A, Mammadbayli A, Arons M, Skorobogatykh K, Romanenko V, Terwindt GM, Paemeleire K, Sacco S, Reuter U, Lampl C, Schytz HW, Katsarava Z, Steiner TJ, Ashina M (2021) Diagnosis and management of migraine in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurol 17:501–514. 10.1038/s41582-021-00509-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ducros A, de Gaalon S, Roos C, Donnet A, Giraud P, Guégan-Massardier E, Lantéri-Minet M, Lucas C, Mawet J, Moisset X, Valade D, Demarquay G (2021) Revised guidelines of the French headache society for the diagnosis and management of migraine in adults. Part 2: Pharmacological treatment. Rev Neurol (Paris) 177:734–752. 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, Ware JE Jr., Garber WH, Batenhorst A, Cady R, Dahlöf CG, Dowson A, Tepper S (2003) A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 12:963–974. 10.1023/a:1026119331193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houts CR, Wirth RJ, McGinley JS, Cady R, Lipton RB (2020) Determining thresholds for meaningful change for the headache impact test (HIT-6) total and Item-Specific scores in chronic migraine. Headache 60:2003–2013. 10.1111/head.13946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smelt AF, Assendelft WJ, Terwee CB, Ferrari MD, Blom JW (2014) What is a clinically relevant change on the HIT-6 questionnaire? An Estimation in a primary-care population of migraine patients. Cephalalgia 34(1):29–36. 10.1177/0333102413497599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR (2004) Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a National panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:12. 10.1186/1477-7525-2-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo N, Liu G, Li M, Guan H, Jin X, Rand-Hendriksen K (2017) Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health 20:662–669. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X (2011) Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 20:1727–1736. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM (1993) The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics 4:353–365. 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton RB, Munjal S, Buse DC, Bennett A, Fanning KM, Burstein R, Reed ML (2017) Allodynia is associated with initial and sustained response to acute migraine treatment: results from the American migraine prevalence and prevention study. Headache 57:1026–1040. 10.1111/head.13115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (2012) Sumatriptan (oral route of administration) for acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:Cd008615. 10.1002/14651858.CD008615.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Géraud G, Keywood C, Senard JM (2003) Migraine headache recurrence: relationship to clinical, pharmacological, and Pharmacokinetic properties of triptans. Headache 43:376–388. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Z, Wang X, Niu M, Wei Q, Zhong H, Li X, Yuan W, Xu W, Zhu S, Yu S, Liu J, Yan J, Kang W, Huang P (2024) First real-world study on the effectiveness and tolerability of Rimegepant for acute migraine therapy in Chinese patients. J Headache Pain 25:160. 10.1186/s10194-024-01873-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pozo-Rosich P, van Veelen N, Caronna E, Vaghi G, Torres-Ferrus M, van der Arend BWH, Goadsby PJ, Ashina M, Wang SJ, Diener HC, Tassorelli C, Terwindt GM (2025) Guidelines of the international headache society for Real-World evidence studies in migraine and cluster headache. Cephalalgia 45:3331024251318016. 10.1177/03331024251318016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton RB, Pozo-Rosich P, Blumenfeld AM, Li Y, Severt L, Stokes JT, Creutz L, Gandhi P, Dodick D (2023) Effect of Atogepant for preventive migraine treatment on Patient-Reported outcomes in the Randomized, Double-blind, phase 3 ADVANCE trial. Neurology 100:e764–e777. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000201568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipton RB, Halker Singh RB, Mechtler L, McVige J, Ma J, Yu SY, Stokes J, Dabruzzo B, Gandhi P, Ashina M (2023) Patient-reported migraine-specific quality of life, activity impairment and headache impact with once-daily Atogepant for preventive treatment of migraine in a randomized, 52-week trial. Cephalalgia 51:3331024231190296. 10.1177/03331024231190296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M, Guo A, Wu J, Wang H, Zhang Y, Dong H, Liu J, Zhang B, Guo H, Yu T, Lu Z, Ma L, Fountaine RJ, Pixton GC, Zhong Q, Han X, Yu S (2025) Rimegepant for the acute treatment of migraine: A phase 3, multicenter, open-label, long-term safety and effectiveness study in adults from China. Cephalalgia 45(10):3331024251371686. 10.1177/03331024251371686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silberstein SD (2004) Migraine Lancet 363:381–391. 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)15440-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwedt TJ, Myers Oakes TM, Martinez JM, Vargas BB, Pandey H, Pearlman EM, Richardson DR, Varnado OJ, Cobas Meyer M, Goadsby PJ (2024) Comparing the efficacy and safety of galcanezumab versus Rimegepant for prevention of episodic migraine: results from a Randomized, controlled clinical trial. Neurol Ther 13:85–105. 10.1007/s40120-023-00562-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ansari T, Lagman-Bartolome AM, Monsour D, Lay C (2020) Management of menstrual migraine. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 20:45. 10.1007/s11910-020-01067-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krause DN, Warfvinge K, Haanes KA, Edvinsson L (2021) Hormonal influences in migraine - interactions of oestrogen, Oxytocin and CGRP. Nat Rev Neurol 17:621–633. 10.1038/s41582-021-00544-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aggarwal M, Puri V, Puri S (2012) Effects of Estrogen on the serotonergic system and calcitonin gene-related peptide in trigeminal ganglia of rats. Ann Neurosci 19:151–157. 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.190403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacGregor EA, Hutchinson S, Lai H, Dabruzzo B, Yu SY, Trugman JM, Ailani J (2023) Safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of perimenstrual migraine attacks: A post hoc analysis. Headache 63:1135–1144. 10.1111/head.14619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pellesi L, Do TP, Ernst MT, Hallas J, Pottegård A (2025) Adoption of Rimegepant in denmark: a register-based study on uptake, prescribing patterns and initiator characteristics. J Headache Pain 18(1):83. 10.1186/s10194-025-02028-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fullerton T, Pixton G (2024) Long-Term use of Rimegepant 75 mg for the acute treatment of migraine is associated with a reduction in the utilization of select analgesics and antiemetics. J Pain Res 15:17:1751–1760. 10.2147/JPR.S456006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells-Gatnik WD, Pellesi L, Martelletti P (2024) Rimegepant and atogepant: novel drugs providing innovative opportunities in the management of migraine. Expert Rev Neurother 24(11):1107–1117. 10.1080/14737175.2024.2401558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

There are ethical restrictions on sharing of de-identified data for this study. The ethics committee has not agreed to the public sharing of data as we do not have the participants’ permission to share their anonymous data.