Abstract

Background

Frailty is highly prevalent in older gastric cancer patients and seriously affects their prognosis, but gastric cancer-related frailty interventions are rare currently. The purposes of this study are to explore the willingness and preference of demanders, implementers, and administrators of frailty interventions for older gastric cancer patients based on stakeholder perspectives, and to analyze possible resistance in the intervention process.

Method

Older gastric cancer patients hospitalized in a tertiary hospital in Jiangsu Province from April to August 2023, as well as some healthcare professionals and administrators in this hospital, were selected for qualitative interviews. Colaizzi 7-step analysis was used for coding, categorizing, and extracting data.

Results

A total of 3 themes and 13 sub-themes were identified, including willingness to participate (Patients: very willing to participate in frailty interventions and eager to improve health conditions; Healthcare professionals: willingness to participate to improve patient health when time permits; Hospital administrators: willingness to participate in improving the health of patients as permitted by the hospital); preferences (Patients: preference for actionable, cost- and time-efficient interventions; Healthcare professionals: preference for staged, individualized, supervised interventions; Hospital administrators: preference for science-based, implementable, cost-effective interventions with oversight mechanisms); resistance (Patients: lack of self-awareness of health management, insufficient family support and fear of becoming the “burden”, insufficient social support and “no channel” for counseling; Healthcare professionals: lack of frailty expertise and intervention experience, limited energy of personnel and easy to lack of motivation; Hospital administrators: lack of standardized management system for frailty, and lack of frailty intervention feedback-evaluation system).

Conclusion

Administrators need to identify needs and preferences under different positions, address resistance that affect the frailty interventions, and provide a reference basis for the implementation of frailty interventions.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Frailty intervention, Willingness, Preference, Resistance, Qualitative study

Introduction

Gastric cancer remains one of the major threats to global public health due to its high morbidity and mortality [1]. With aging, gastric cancer patients over 60 years old account for 72.8% of all gastric cancer patients, contributing to a large group of elderly gastric cancer patients [2]. Such patients often suffer from frailty symptoms such as weight loss, fatigue, and weakness during their illness [3].

Frailty is a complex age-related clinical condition characterized by a decline in physiological capacity across several organ systems, with a resultant increased susceptibility to stressors [4]. Older gastric cancer patients have inherently lower physiological reserves due to advanced age, and the invasion of gastric malignancy and a series of stressors such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy acting on the organism make this population more susceptible to frailty, with a frailty incidence as high as 45.9% [5]. Most of the current studies have shown that frailty leads to a variety of adverse outcomes in gastric cancer patients, such as increased postoperative complications, increased toxic side effects of chemo-radiotherapy, decreased quality of life, increased mortality and burden of care [6, 7]. Therefore, it is necessary to implement frailty interventions in older gastric cancer patients as soon as possible to reduce the incidence of adverse outcomes.

Most of the current studies on frailty interventions focus on the older people in the community and nursing homes [8–10]. Considering the multidimensional nature of frailty and the complexity of care needs in older gastric cancer patients, interventions for older gastric cancer patients must reflect the priorities and constraints of all stakeholders involved. The concept of stakeholders refers to all individuals and groups that can influence the achievement of an organization’s goals or are affected by the process of an organization’s achievement of its goals [11]. Incorporating stakeholder perspectives enables a more realistic, patient-centered, and implementable approach to frailty management, which is especially important in resource-limited healthcare environments. However, currently, many interventions are implemented in a way that ignores the needs of the interests of various stakeholders and usually focuses on the preferences of individual stakeholders, a limited perspective that does not adequately reflect information about frailty interventions, making it difficult for interventions to be implemented in reality [12]. Especially in the process of frailty interventions for older gastric cancer patients, the willingness to participate, motivation, interests, and preferences of patients(demanders), healthcare professionals (implementers), and hospital administrators(administrators) are different, and there may be multiple conflicts of interest, so only by dissecting the interests of all parties and coordinating the development of interests can we promote the smooth implementation of frailty interventions.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to conduct semi-structured interviews with personnel of stakeholders (demanders, implementers, and administrators) involved in frailty interventions for older gastric cancer patients from the perspective of stakeholders, in order to clarify the differentiated interests under different positions, and to analyze in-depth the resistance factors affecting the implementation of frailty interventions, so as to provide a reference basis for the implementation of frailty interventions in later stages.

Method

Study design

This study adopted a phenomenological qualitative approach to capture the lived experiences and essence of stakeholders’ perceptions regarding frailty interventions through semi-structured interviews. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines [13]were followed.

Study setting

This study was conducted from April to August 2023 at a tertiary hospital in Jiangsu Province, China. In order to understand and analyze the stakeholders’ willingness, preference and possible resistance factors to frailty interventions for older gastric cancer patients, data were collected from three parties: older gastric cancer patients, healthcare professionals and hospital administrators.

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

The study was conducted by researchers with expertise and experience, including a male physician with twenty years of clinical experience in gastric cancer medicine and frailty expertise; two female PhDs with experience in geriatric oncology care and health management; and three female Masters of Science in Nursing (Clinical Research Assistants) with experience in qualitative interviewing and clinical interventions.

Study participants and sampling strategy

We adopted purposive sampling to recruit key stakeholders involved in frailty interventions, aiming to ensure broad representation across three groups: patients (demanders), healthcare professionals (implementers), and hospital administrators (decision-makers). Stakeholders for each category were selected based on the criteria in Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for recruitment of various stakeholders

| Stakeholders | Inclusion and exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Patients |

Inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosed with gastric cancer by gastroscopy and pathological examination; (2) aged ≥ 60 years; (3) assessed as frailty by Tilburg frailty scale(TFI ≥ 5); (4) be able to communicate simply in writing and verbal; (5) aware of their own diagnosis of the disease; and (6) voluntarily cooperated with the participation in the present study and signed an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria: (1) severe cardiac, hepatic and renal insufficiency; (2) physical disability; (3) tumors in other parts of the body. |

| Healthcare professionals |

Inclusion criteria: (1) officially employees of the hospital; (2) having three or more years of clinical work experience with elderly gastric cancer patients; (3) voluntarily participating in this study and signing the informed consent. Exclusion criteria: took leave or vacation in the last three months. |

| Hospital administrators |

Inclusion Criteria: (1) officially employed staff of the hospital; (2) having ten years or more experience in the management of patients; (3) voluntarily participating in this study and signing the informed consent. Exclusion criteria: took leave or vacation in the last three months. |

The sample size and group proportions were guided by data availability and thematic saturation, in line with Guest et al.’s recommendations [14]. Interviews continued until no new themes or concepts emerged. This process involved parallel interviews by multiple researchers, followed by iterative coding and theme comparison. To enhance diversity and richness, we ensured variation in participant background (e.g., age, gender, income, role), used an iterative data collection-analysis cycle, and maintained reflexivity. A semi-structured interview guide was developed and piloted prior to formal interviews.

Interview outlines developing

The interview guide was developed based on the study objectives, literature review, and expert consultation. Pre-interviews were conducted with two patients, two healthcare professionals, and one hospital administrator to refine the questions. The final interview outline is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outline of interviews with various stakeholders

| Stakeholders | Interview outlines |

|---|---|

| Patients | ①Have you been concerned about your problems during frailty your illness? ② Are you willing to participate in a frailty intervention related to frailty interventions?③If you are willing to participate, what kind of guidance content do you prefer for frailty interventions? ④If you are not willing to participate, what are the main reasons for not participating? ⑤Do you have any other ideas or suggestions for frailty interventions? |

| Healthcare professionals | ① Do you pay attention to the frailty problems of gastric cancer patients in your work? ② Are you willing to participate in the implementation of frailty interventions for gastric cancer patients? ③ If you are willing to participate, based on your clinical experience, what kind of interventions for older gastric cancer patients do you prefer? ④ If you are not willing to participate, what are the main reasons for not participating? ⑤ Do you have any other ideas or suggestions for frailty? |

| Hospital administrators | ① Do you pay attention to the frailty management of gastric cancer patients in your work? ② Are you willing to participate in the management of frailty interventions for gastric cancer patients? ③ If you are willing to participate, based on your management experience, what kind of intervention for older gastric cancer patients do you prefer? ④ If you are not willing to participate, what are the main reasons for not participating? ⑤ Do you have any other ideas or suggestions for frailty? |

While some questions (e.g., “Are you willing to participate in frailty interventions?”) were close-ended in form, they served as entry points for open-ended probing (e.g., “Can you explain why?” or “What type of intervention would you prefer?”), which elicited detailed, narrative responses. These rich qualitative insights formed the basis for our thematic analysis, and the binary answers themselves were not directly coded.

Before each interview, participants received written materials introducing the study purpose. At the start of the interview, researchers used a standardized script and visual aids to explain the concept of frailty and relevant interventions. For patients unfamiliar with the topic, additional lay-language explanations were provided to ensure basic understanding. This process helped reduce baseline knowledge differences and facilitated informed, meaningful responses.

Data collection

Phenomenological research was used to collect data through one-on-one semi-structured interviews. The researcher explained the purpose, significance and process of the study to the interviewees before the interviews, and then formally conducted the interviews and synchronized the recordings after obtaining the trust and consent of the interviewees. Each interview lasted about 20–40 min. During the interview, the researcher listened carefully to the interviewees’ expressions, encouraged them to fully express their own ideas and suggestions, and appropriately asked follow-up questions, restated and summarized, while observing the interviewees’ expressions, movements and other non-verbal feedback. Interviews were stopped when respondents’ information was repetitive and no new themes emerged from the analysis of the information, i.e., when the information was saturated [14].

To ensure psychological comfort, interviews were conducted in private settings with empathetic, non-judgmental language. When sensitive topics arose (e.g., family burden), interviewers used open-ended and gentle prompts, and participants were reminded they could skip any question or pause the interview.

To adhere to phenomenological principles, researchers engaged in bracketing by keeping reflexive diaries and holding regular peer discussions, in order to minimize the influence of preconceptions on data collection and interpretation.

Data analysis and coding (section2)

Audio recordings were transcribed within 24 h and verified for accuracy, then imported into NVivo 12.0 for analysis. Colaizzi’s 7-step phenomenological analysis method [15] was applied, which emphasizes extracting significant statements, formulating meanings, clustering into themes, and ultimately distilling the essence of participants’ lived experiences. This process goes beyond descriptive categorization, aligning with phenomenological principles of capturing the core meaning of lived experience.

To ensure analytical rigor, two researchers independently coded all transcripts and then met to compare coding decisions. Inter-coder reliability was enhanced through regular consensus meetings, during which discrepancies were discussed and resolved. A third researcher mediated any unresolved disagreements. An audit trail was maintained throughout the coding process, documenting decisions related to code development, theme refinement, and analytical memos. In addition, member checking was conducted by returning the preliminary findings to a subset of participants from each stakeholder group to confirm that the results accurately reflected their experiences and perspectives. No substantial revisions were requested, indicating consistency between participants’ intended meaning and the analytical interpretations.

Result

Participants

Semi-structured interviews were held with 10 older gastric cancer patients (demanders), 8 healthcare professionals (implementers), and 6 hospital administrators (administrators). Table 3 shows the characteristics of per respondent group such as age, gender and education level.

Table 3.

Characteristics of various stakeholders

| Item | Demanders | Implementers | Administrators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients(n = 10) | healthcare professionals (n = 8) |

hospital administrators (n = 6) | ||

| Age | 20~ | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 30~ | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| 40~ | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 50~ | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 60~ | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 70~ | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| Female | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| Education level | Primary and below | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Middle school | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| University and above | 1 | 8 | 6 | |

| Marital status | Married | 9 | 5 | 6 |

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Residence | Urban | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Rural | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Working experience | (3,5] years | - | 3 | 0 |

| (5,10]years | - | 3 | 0 | |

| Over 10 years | - | 2 | 6 | |

| professional position | Junior | - | 1 | 0 |

| Intermediate | - | 5 | 1 | |

| Senior | - | 2 | 5 |

Themes

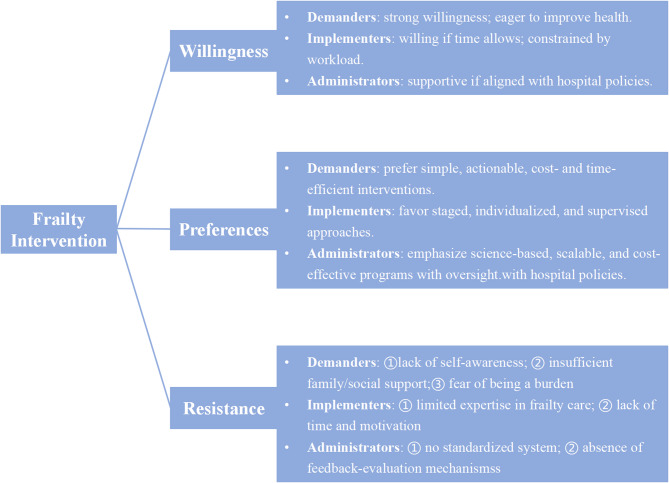

Through semi-structured interviews, 3 themes and 13 sub-themes were finally aggregated and analyzed based on the three research objectives of willingness to participate, preference for intervention and resistance to participation. The details are shown in Fig. 1. The identified themes represent not only categories of responses but the essential structure of stakeholders’ lived experiences of frailty interventions.

Fig. 1.

Summary of interview topics

Theme 1: willingness - differences in the strength of willingness to participate in frailty interventions

Sub-theme1: demanders (patients) are very willing to participate in frailty interventions and eager to improve their health conditions

The onset of gastric cancer is relatively insidious, and many patients often have no obvious clinical symptoms when they are diagnosed [16], and they are often at a loss as to what to do, coupled with the possibility of subsequent fatigue, weakness, and other frailty phenotype. They are extremely uncertain about their health conditions and prognosis, and at this time, many of them are eagerly seeking for various ways to improve their health conditions. So when the researcher suggested that there was such a frailty intervention for frailty interventions, they were undoubtedly like drowning people grasping at straws; they may not have understood what the frailty intervention was at all, but as long as they thought it was helpful and beneficial to their health, they were eager to participate in it.

Patient 8: “We are very happy to participate, this is helpful to our health, we all want to get better faster, we cooperate positively.”

Patient 10: “We are old, we don’t particularly understand frailty, but what you professionals suggest is definitely good for my health, we are positive to cooperate and participate.”

Sub-theme2&3: conditions permitting, implementers and administrators willing to participate in frailty interventions to improve the patient’s health status

Healthcare professionals and hospital administrators are the escorts of patients’ health status. Many older gastric cancer patients have a low level of education and they have little knowledge about the disease, and the attitude of healthcare professionals and administrators toward the patient may be decisive for the patient’s health. For frailty interventions, both implementers and administrators recognized its clinical value and expressed their willingness to participate in frailty interventions for patients and contribute to their health if conditions permit.

Healthcare professional 2: “Frailty interventions are necessary and we are happy to get involved to help patients improve their health if time permits”.

Administrator 3: “We have found that frailty in older gastric cancer is quite common and as managers we have a willingness to improve this provided that all intervention processes are in line with hospital regulations”.

Theme 2: preferences - differences in focus between parties’ preferences for frailty interventions

Sub-theme 4: patient prefer interventions that are actionable, cost-and time-efficient

Older gastric cancer patients over 60 years are mostly in the dual role changes caused by retirement and tumor, and they have difficulties in adapting to the current role perception, and are prone to dependency and reduced self-efficacy. They feel unconfident about their success in completing a certain intervention behavior, and usually prioritize the operability of the intervention, and they prefer interventions that are simple and routine, specific and detailed, and easy to achieve. In addition, this population has limited income and energy, and they also value the economic-time burden of the intervention as well as the substantial effects of the intervention, preferring frailty interventions with cost-and time-efficient and short-term benefits.

Patient 3: “I have a preference for simple exercise interventions like walking, we, the elderly, can only do simple and easy interventions, we can’t do the resistance exercises you just mentioned.”

Patient 5: “I want interventions that work. If I followed your interventions for months and not see results, then I definitely think this is useless and a waste of time and money.”

Patient 9: “I want specific guidance on interventions, such as diet, with more options listed for us to choose from. It would be like being at a restaurant and being given a specific menu to choose from.”

Sub-theme 5: healthcare professionals prefer interventions that are staged, individualized and supervised

The recommendations of healthcare professionals are determinants of frailty interventions. Most healthcare professionals felt that there was a need for staged, individualized frailty interventions based on the patient’s disease progression, and that there should be dedicated supervisory staff in the intervention to improve patient compliance.

Healthcare professional 3: “Based on my clinical experience over the years, I believe that whatever intervention is being developed must be based on the patient’s stage of progression.”

Healthcare professional 5: “I have done similar interventional studies before, and I think the most important about interventions is that they have to be supervised to evaluate whether the patient’s intervention is completed and how well it is completed. There is no way to ensure patient compliance if there is no supervision and evaluation.”

Sub-theme 6: hospital administrators prefer science-based interventions that are implementable, cost-effective and have oversight mechanisms

Hospital administrators’ attitudes toward the frailty intervention were the prerequisite for its implementation. All administrators agreed that the science of the intervention itself was fundamental to their decision-making; Secondly, whether the intervention was realistically implemented and whether it was cost-effective was also an important factor; Furthermore, administrators also believed that a good intervention required a monitoring-feedback mechanism, which was an important guarantee of the effective implementation of the intervention.

Administrator 1: “The first thing we consider is whether the frailty interventions are scientific or not, this is the most important thing, after all, these interventions are going to be used on the patient and we have to make sure that the patient is completely safe.”

Administrator 2: “Intervention science is one aspect, on the other hand, we also have to see whether the intervention is practical, in case the intervention design is very scientific, but the reality can not be realized, that means its still at the theoretical level; in addition, we will certainly also consider the economic effect, at the same time, there should be a feedback mechanism to form a standardized process.”

Theme 3: resistance - participants have diverse reasons for reluctance to engage in frailty interventions

Demanders

Sub-theme 7: lack of self-awareness of health management

Despite the strong willingness of patients to participate in frailty intervention, because of the disease-specific nature of gastric cancer, many patients are from rural areas and have low education levels, and they do not understand the intervention itself. In their perception, they were willing to participate in whatever the intervention was labeled as “good for their health”. Interviews revealed that many patients had a misperception of frailty, a subjective view of frailty as aging, and negative attitude toward the pathological changes and adverse experiences associated with gastric cancer. Although at first they expressed their willingness to participate in the frailty intervention, this misperception and negative attitude would invariably affect their subsequent behavior and reduce their compliance.

Patient 1: “When you get older, your physical strength deteriorates, leading to frailty. It’s like a machine, when you use it for a long time it gets old and has problems, it’s inevitable.”

Patient 7: “I feel that when my health is poor I need the frailty intervention, but when my health improves I no longer need this intervention.”

Sub-theme 8: insufficient family support and fear of becoming the “burden”

The economic condition of the family is an important determinant of the way and degree of participation in medical decision-making [17]. Many gastric cancer patients believe that tumor treatment itself has already brought a lot of financial burden to their families, and they are unwilling to add additional expenses. In addition, due to the poor physical function of older gastric cancer patients, it is difficult for them to complete the frailty interventions independently, and they need help support from family members. However, in recent years, the family size has been reduced and the living structure has been decentralized [18, 19], and many children do not live with the older, and the patients are also afraid of becoming the “burden” and do not want to bother their family members more.

Patient 2: “I am now hospitalized mainly to come for operation, other frailty related items will not be done first, itself I have to spend a lot of money on this disease, and subsequent chemotherapy.”

Patient 6: “ I don’t have much income, mainly rely on nation welfare, my children are very busy at work and it’s not easy to earn money, I don’t want to become the burden of my children.”

Sub-theme 9: insufficient social support and “no channel” for counseling

Social support is also an important factor influencing frailty interventions. Effective counseling pathways can contribute to the implementation of frailty interventions. Many patients felt that the lack of effective counseling and communication pathways with healthcare professionals during the discharge home period and the inability to get timely answers to questions they encountered could be a hindrance to the implementation of their frailty interventions.

P4: “Is there any counseling pathway to answer my questions if I have problems with the intervention after discharge.”

Implementers

Sub-theme 10: lack of frailty expertise and intervention experience

The lack of professional knowledge about frailty among healthcare professionals is one of the most important reasons hindering frailty interventions. Frailty is a syndrome affected by a variety of factors, so frailty intervention involves a wide range of content, including exercise, nutrition, psychology, rehabilitation and other areas of medicine, many healthcare professionals do not yet have such a comprehensive knowledge and intervention experience.

Healthcare professional 1: “My usual work is mainly focused on perioperative care of gastric cancer patients, and I have not received special training in this area of geriatric frailty, and my knowledge in this area needs to be strengthened.”

Healthcare professional 6: “There are quite a lot of areas of frailty interventions, some of which have not been touched at all, and it is still necessary to form a multidisciplinary team to carry out this work, and our gastric surgeon’s knowledge alone is definitely not enough.”

Sub-theme 11: limited energy of personnel, easy to lack of motivation

Healthcare professionals, as implementers of frailty interventions, are an important component of frailty interventions. The interviewed healthcare professionals all affirmed the value of frailty interventions, however, due to the existing heavy clinical workload, it is difficult to have extra energy and motivation to pay long-term attention to the problem of frailty in older gastric cancer patients.

Healthcare professional 4:“We have a lot of workload now, with nine patients to manage per nurse, there may be little extra time and energy to implement frailty interventions on a long-term basis.”

Healthcare professional 7:“To be honest, frailty interventions take a lot of time and people will definitely lack motivation if they are long term, after all, no one wants to add to their workload.”

Healthcare professional 8:“Frailty interventions need to be organized in a dedicated team to do it or rotate like a roster to designate people to guide the implementation of frailty interventions.”

Administrators

Sub-theme 12: lack of standardized management system for frailty

Currently, there is a wide variety of frailty screening and assessment tools, but they lack specificity, and the frailty screening and assessment tools for specific populations in specific settings are still unclear. Hospital management is still in the groping stage for frailty interventions, and has not yet developed a standardized management process and system, and there are still no standards for the selection of frailty screening and assessment tools and the timing of frailty intervention for older gastric cancer patients.

Administrator 4:“In fact, as a hospital administrator, I myself am not sure how to carry out frailty interventions and management for gastric cancer patients, because it is not like nutrition and pain that have formed a very mature management system with a very clear process. All frailty management are still in the exploratory stage.”

Administrator 6:“At present, the hospital has no special training in this aspect of frailty management, like the patient’s lung function training, thrombosis prevention, etc., the hospital has a set of standardized standards. But regarding frailty, it is not clear yet.”

Sub-theme 13: lack of frailty intervention feedback-evaluation system

Frailty is a continuous and dynamic process that covers the entire disease cycle from in-hospital to out-of-hospital [20]. Hospital administrators indicated that in-hospital frailty interventions could be guaranteed to be carried out, while out-of-hospital interventions were difficult to follow up and lacked a feedback-evaluation system to ensure the effectiveness of their interventions.

Administrator 5: “I am more concerned about how to know how well the discharged patients are completing the frailty interventions and how to observe the effect of the patients after they are discharged from the hospital.”

Discussion

Frailty is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients [7, 21], and early intervention for it can effectively improve the outcomes of patients. However, there are few studies on frailty interventions for gastric cancer patients. In this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 10 patients, 8 healthcare professionals, and 6 hospital administrators to understand the willingness to participate in frailty interventions, preferences, and perceived resistance to interventions among stakeholders, which provided a basis for our subsequent implementation of the intervention.

Fully harmonize preferences and synergize to promote healthy patient regression

Before the implementation of frailty interventions, it is necessary to fully consider the willingness preferences of all parties. The results of this study showed that the intensity of willingness to participate in frailty interventions varied among the three parties, with patients’ willingness to participate being very strong, while healthcare professionals and hospital administrators’ willingness was average. The imbalance in supply and demand for frailty intervention suggests that we need to increase the motivation of healthcare professionals and hospital administrators to participate in frailty interventions and try to make the willingness of the three parties to reach the same level before the implementation of the interventions. In terms of preferences for frailty interventions, there is a degree of variability in the preferences of the three parties, as they have different focuses on frailty interventions. Therefore, before intervention, we need to respect the preferences of stakeholders from different positions, fully consider the demands of all parties, integrate the needs of multiple parties, and consider the feasibility, economy, scientificity, and effectiveness of the intervention, so as to maximize the realization of the preferences of multiple parties, and to collaborate to promote the benign regression of the patient’s health outcomes [22].

Improvement of patients’ frailty cognitive level and reinforcement of health management beliefs

The results of this interview showed that most patients had a wrong perception of frailty, wrongly equating frailty with aging, which is consistent with the results of Wang et.al [23]. According to Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [24], behavioral change is influenced not only by knowledge, but also by self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social modeling. In the context of frailty intervention, enhancing patients’ understanding of frailty is a critical first step, but alone it is insufficient.To foster meaningful engagement, interventions should aim to strengthen patients’ self-efficacy—their belief in their ability to actively manage frailty. This can be achieved through goal-setting, positive feedback, and showcasing successful peer examples (observational learning). In addition, clear messaging about the benefits of interventions (e.g., faster recovery, improved strength) can enhance outcome expectations and motivate participation.

Therefore, healthcare professionals and administrators can incorporate these principles into health education strategies. Regular frailty-specific education using brochures, peer stories, videos, and interactive sessions can help reshape patients’ beliefs and promote behavior change. Furthermore, digital tools such as AI-assisted platforms and self-media can support continuous reinforcement, facilitate communication, and reduce the workload of providers while maintaining patient motivation. Grounding such efforts in SCT enhances both the credibility and effectiveness of patient-centered frailty interventions.

Actively promoting frailty specialized training and establishing positive incentives

Interviews revealed that insufficient knowledge of frailty was an important barrier factor affecting the implementation of their interventions. Wang et al. also showed that healthcare professionals did not receive professional training on frailty, and their understanding of frailty was superficial, so they were unable to provide professional guidance to patients [23]. Therefore, hospital administrators should actively carry out frailty-related training, strengthen the frailty training for healthcare professionals, improve their professionalism, form a multidisciplinary team to identify frail older gastric cancer patients at an early stage, and provide professional guidance, so as to prevent and slow down the process of frailty. In addition, long-term interventions will kill the enthusiasm of healthcare professionals, and it is recommended that hospitals establish positive incentives to provide mental or material incentives, including financial bonuses, professional development opportunities, or public recognition, to healthcare workers who actively implement frailty interventions, thereby increasing their motivation to implement frailty interventions, which in turn will improve patients’ health outcomes.

Improve the institutional process of frailty intervention and sound tumor-frailty prevention and treatment system

We found that there is a lack of unified and standardized management processes for frailty interventions in gastric cancer patients, and a more complete tumor-frailty prevention and treatment system has not yet been established. At this stage, there are numerous screening and assessment tools for frailty, but most of these tools lack specificity [25, 26]. In the future, we need to develop specific screening and assessment tools for frailty in the older oncology population and even in the older gastric cancer population, and to unify the evaluation indexes to increase the comparability between studies. Secondly, we need to clarify the timing of screening and assessment, and establish a scientific and efficient tumor-frailty prevention and treatment system to help older gastric cancer population cope with frailty scientifically. In addition, the results of our study showed that inadequate family social support is also a major barrier to frailty interventions. The Asia-Pacific Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Frailty emphasized frailty interventions for the population of older people with cancer [27], and thus implementing frailty interventions for this population is of great social significance and value. We call on governments around the world to increase funding for the health service system for older oncology patients, provide adequate social security, and also assist in the development and optimization of smart aging platforms and several other measures to guarantee the convenience of patients’ access to healthcare services and reduce the burden of care on the society and families.

Constructing a hospital-community-family tripartite linkage frailty management pattern to form a virtuous cycle

The results of the study show that the current management pathway regarding frailty interventions for gastric cancer patients is still imperfect, and there is an interaction gap between healthcare professionals and patients. In addition, the distribution of medical resources in China is not balanced, and most medical resources are concentrated in large tertiary hospitals. Against this background, most patients choose tertiary hospitals for treatment in order to obtain better medical resources and seek farther away from home. This suggests that we need to optimize the hierarchical diagnosis and treatment system, promote the sinking of high-quality medical resources, narrow the gap between large hospitals and community hospitals in terms of service and technology, eliminate the mistrust of patients to grass-roots community hospitals, and gradually form a “small illnesses to the community, serious illnesses into the hospital, and rehabilitation back to the community” [28] of the pattern of medical treatment. The community has set up a “bridge” between the hospital and the patient’s family, undertaking the continuity of treatment after the patient is discharged from the hospital. Therefore, we should construct and vigorously promote the hospital-community-family tripartite linkage frailty management pattern [29], in the vertical level of effective integration and distribution of health care resources to meet the needs of patients’ services, and to realize the benign cycle of patients’ home frailty management process. While the hospital-community-family model is promising, it requires strong infrastructure, digital connectivity and policy support. Therefore, there is a need to move forward with pilot projects and gradual implementation in the future to help assess feasibility and resource consistency in real-world settings.

Integrating stakeholder willingness, preferences, and resistance: s synthesis

Although willingness, preferences, and resistance were initially discussed as separate themes, our findings indicate they are deeply interconnected across stakeholder groups. Patients often demonstrated strong willingness to participate in frailty interventions, but this motivation was limited by resistance factors such as low self-efficacy, limited family support, and a lack of clear guidance. Healthcare professionals and administrators also expressed willingness, but this was conditional—shaped by workload, policy constraints, and the need for structured, evidence-based frailty interventions. Across all stakeholder groups, the tension between willingness and resistance emphasizes the critical importance of aligning stakeholder expectations and capacity. Preferences act as a mediating force between the two: where preferences are met, willingness can be translated into action and resistance reduced. Where preferences are ignored or conflict between groups, interventions may be stalled or rejected. Therefore, future frailty interventions should be co-designed with all stakeholders to achieve balance: matching patients’ expectations for feasibility with healthcare providers’ need for structure and administrators’ demand for efficiency. Only through coordinated engagement can frailty interventions be meaningfully implemented and sustained across the hospital-community-family triad.

Limitations and implications for future research

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single tertiary hospital in Jiangsu Province, China, and thus the transferability of the findings to other healthcare settings, including rural hospitals or different cultural contexts, may be limited. Second, although we achieved thematic saturation, the sample size (n = 24) was relatively small, especially given the potential heterogeneity of participants. Future studies could expand to include multiple institutions and more diverse participants to enhance the robustness and generalizability of findings. Nevertheless, our research contributes valuable insights by triangulating the views of demanders, implementers, and administrators on frailty interventions in the context of gastric cancer, a topic rarely addressed in current literature.

Conclusion

Based on the stakeholder perspective, this study conducted semi-structured interviews with older gastric cancer patients with frailty, healthcare professionals, and administrators to further understand the willingness to participate in frailty interventions, preferences, and possible resistance of each party, and summarized and analyzed 3 themes and 13 sub-themes. The results suggest that administrators need to identify the needs and preferences under different positions and address the resistance that affects the implementation of frailty interventions, which can inform the implementation of frailty interventions in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: Yinning Guo, Qin Xu; Acquisition of data: Yinning Guo, Shulin Song, Lingyu Ding, Lisi Duan; Analysis and interpretation of data: Yinning Guo, Shulin Song; Hanfei Zhu, Kang Zhao, Li Chen, Hui Hou; Drafting of the manuscript: Yinning Guo; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Qin Xu, Xinyi Xu, Ting Xu.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by project “The exploration of trajectories and intervention program of frailty for gastric cancer survivors based on the health ecology theory” supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No.82073407), Project“Research on the dynamic interaction mechanism and collaborative intervention strategies of multiple frailty subtypes in elderly cancer survivors”supported by NSFC (No: 72404140), Project “Research on the mechanisms and intervention strategies of dietary behaviors of older gastric cancer survivors on frailty development under multi-temporal-situational interactions”supported by Jiangsu Province Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Program(KYCX25_2198)and Project of “Nursing Science”Funded by the 4th Priority Discipline Development Program of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions(Jiangsu Education Department(2023)No.11).

Data availability

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University in China (Number: 2020 − 273). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Consent to participate was confirmed by signing an informed consent form prior to the start of the interview. All data were deidentified and stored in a password-protected network.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yinning Guo and Shulin Song contributed equally to this work and they are co-first authors.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [J]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer[EB/OL]. 2023. https://gco.iarc.fr/.

- 3.Wang N, Jiang J, Xi W, et al. Postoperative BMI loss at one year correlated with poor outcomes in Chinese gastric cancer patients [J]. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(15):2276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dent E, Martin FC, Bergman H, et al. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1376–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding L, Miao X, Lu J, et al. Comparing the performance of different instruments for diagnosing frailty and predicting adverse outcomes among elderly patients with gastric cancer [J]. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(10):1241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng Y, Zhao P, Yong R. Modified frailty index independently predicts postoperative pulmonary infection in elderly patients undergoing radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer [J]. Cancer Manage Res. 2021;13:9117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong JR, Choi JW, Ryu SY, et al. Relationship between frailty and mortality after gastrectomy in older patients with gastric cancer [J]. J Geriatric Oncol. 2022;13(1):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh TJ, Su SC, Chen CW, et al. Individualized home-based exercise and nutrition interventions improve frailty in older adults: a randomized controlled trial [J]. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angulo J, El Assar M, Álvarez-Bustos A, et al. Physical activity and exercise: strategies to manage frailty [J]. Redox Biol. 2020;35:101513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng Y, Zhang K, Zhu J, et al. Healthy aging, early screening, and interventions for frailty in the elderly. Biosci Trends. 2023;17(4):252–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.E F R. Strategic management:a stakeholder approach [M]. Boston: Pitman. 1984.

- 12.Lebcir R, Hill T, Atun R, et al. Stakeholders’ views on the organisational factors affecting application of artificial intelligence in healthcare: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e044074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations [J]. J Association Am Med Colleges. 2014;89(9):1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M. Using an example to illustrate Colaizzi′s phenomenological data analysis method [J]. J Nurs Sci. 2019;34(11):90–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SJ, Park J, Shin Y, et al. Deconvolution of diffuse gastric cancer and the suppression of CD34 on the BALB/c nude mice model. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang LL, DeVore AD, Granger BB, et al. Leveraging behavioral economics to improve heart failure care and outcomes [J]. Circulation. 2017;136(8):765–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang R, Wang H, Edelman LS, et al. Loneliness as a mediator of the impact of social isolation on cognitive functioning of Chinese older adults. Age Ageing. 2020;49(4):599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao T, Jin G, Guo Y. Empty-nest elderly households in China: trends and patterns. Popul Res. 2023;47(01):58–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao X, Guo Y, Chen Y, et al. Exploration of frailty trajectories and their associations with health outcomes in older gastric cancer survivors undergoing radical gastrectomy: a prospective longitudinal observation study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2024;50(2):107934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DU, Kwon J, Han J, et al. The clinical impact of frailty on the postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a propensity-score matched database study [J]. Gastric Cancer. 2022;25(2):450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbassi F, Walbert C, Kehlet H, et al. Perioperative outcome assessment from the perspectives of different stakeholders: need for reconsideration? Br J Anaesth. 2023;131(6):969–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, Guan X, Cong X, et al. Cognition and attitude of community health care workers and the elderly on frailty management: a qualitative research [J]. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2020;26(31):4313–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Liu Q, Qian Y. Application of frailty assessment instruments in different elderly populations:a review [J]. J Nurs Sci. 2022;37(24):89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie R. Fu W. Advances in research on frailty assessment tools [J]. Chin J Gerontol. 2021;41(18):4142–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dent E, Lien C, Lim WS, et al. The Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines for the management of frailty [J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(7):564–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.General Office of the State Council. Outline of the national health service plan (2015–2020). 2024. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-03/30/content_9560.htm.

- 29.Yang H, Wang P, Hou W, et al. Design and application of continuing care service platform under the linkage of hospital-community-family [J]. Chin J Nurs. 2016;51(09):1133–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.