Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to elucidate how psychological distress, self-control, and sustainable healthy eating behaviors interact to shape food addiction, by simultaneously modeling their direct and indirect effects in adult population.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 985 adults (mean age: 28.8 ± 10.9) from community health centers in Elazığ, Turkey. Standardized instruments measured depression, anxiety, stress (DASS-21), self-control, sustainable healthy eating, and food addiction (YFAS). Statistical analyses included logistic regression and structural equation modeling (SEM).

Results

Food addiction prevalence was 34.9%. Individuals with food addiction had significantly higher mean depression, anxiety, and stress scores, and lower self-control (37.1 ± 4.3 vs. 40.2 ± 4.3, p < 0.001) and sustainable healthy eating scores (15.0 ± 3.9 vs. 17.6 ± 4.7, p < 0.001) compared to those without addiction. Logistic regression indicated that anxiety (OR[95% CI] = 1.27 [1.20–1.34]) was the strongest predictor, while higher self-control (OR = 0.92[0.88–0.95]) and sustainable eating (OR = 0.94[0.90–0.97]) reduced risk. The final model explained 44% of the variance. SEM showed that self-control and sustainable eating behaviors significantly mediated the relationship between stress and food addiction.

Discussion

Anxiety exerts the strongest direct influence on food addiction, while self-control and sustainable dietary habits serve as key mediators, particularly in the stress–food addiction pathway. These findings underscore the need for multidimensional interventions that integrate psychological and behavioral strategies to effectively prevent and manage food addiction.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-025-01428-2.

Keywords: Food addiction, Anxiety, Stress, Depression, Self-control, Sustainable eating

Plain language summary

This study investigated how psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), self-control, and sustainable healthy eating behaviors interact to influence food addiction among 985 adults in Türkiye. About one-third of participants met the criteria for food addiction, and those individuals showed higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, along with lower self-control and poorer adherence to healthy and sustainable eating habits. Statistical analyses revealed that anxiety was the strongest direct predictor of food addiction, while depression and stress affected it mainly through reduced self-control and unhealthy dietary patterns. Low self-control was also associated with a decline in sustainable eating behaviors, which in turn increased vulnerability to food addiction. These findings suggest that food addiction is not only a behavioral issue but also deeply connected to emotional regulation and lifestyle habits. Promoting mental well-being, strengthening self-control, and encouraging sustainable, balanced diets may help prevent or manage food addiction more effectively, supporting both personal health and broader public health goals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-025-01428-2.

Introduction

Food addiction is a complex phenomenon that affects individuals across all age groups and has significant implications for both individual and public health [1]. The widespread availability of highly palatable, energy-dense foods, particularly refined and ultra-processed products, has led to notable changes in eating behavior. This has fostered the emergence of addiction-like behavioral patterns associated with these foods [2]. In parallel, the rising prevalence of eating disorders worldwide has drawn increasing attention, as these conditions are associated with serious health risks, including obesity, metabolic disturbances, and impaired psychosocial functioning [3]. Their growing public health impact underscores the need for a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and contributing factors. While existing literature has predominantly focused on how changes in the food industry affect the addictive potential of certain foods, it is now increasingly recognized that food addiction has a multifactorial etiology. Today, it is understood not merely as a physiological problem but as a psychobiological process closely linked to psychological well-being, self-control, and emotional regulation [4, 5].

Recent studies have highlighted the strong association between food addiction and various psychological conditions such as depression, anxiety, and chronic stress, demonstrating that these factors significantly influence individuals’ eating behaviors [5, 6]. Individuals experiencing depression and anxiety often engage in maladaptive eating behaviors as a coping mechanism, whereas chronic stress has been shown to increase compulsive eating tendencies and lead to a loss of control over dietary habits [7, 8]. Moreover, depression has been linked to heightened cravings for high-sugar and high-fat foods, which in turn exacerbate mood fluctuations and reinforce addictive-like eating cycles [9]. Anxiety, on the other hand, is associated with emotional dysregulation that predisposes individuals to binge-eating episodes [10]. Together, these mechanisms illustrate how overlapping psychological vulnerabilities can synergistically contribute to the development and persistence of disordered eating behaviors.

Meanwhile, current approaches to combating food addiction increasingly emphasize the importance of sustainable dietary habits. Ultra-processed and energy-dense foods, which are considered to have a high potential for addiction, conflict with the principles of sustainable nutrition and contribute to a negative feedback loop between emotional distress and unhealthy eating behaviors [10]. In contrast, sustainable dietary practices that promote the consumption of whole and minimally processed foods such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains are associated with improved metabolic profiles, reduced risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes, and enhanced mental well-being, may mitigate some of the psychological challenges linked to food addiction [11, 12]. Notably, a recent mediation study demonstrated that adherence to a diet rich in fruits and vegetables was indirectly linked to lower addictive eating tendencies through improvements in mood and stress regulation [13]. Thus, the adoption of sustainable and health-conscious food choices may play a pivotal role in reducing the prevalence and impact of food addiction.

The multifaceted etiology of food addiction, involving the interactive roles of biological, psychological, and behavioral factors, necessitates a multidimensional, holistic and interdisciplinary approach rather than an analysis based solely on isolated variables. However, a review of the existing literature reveals that these determinants are often examined independently, and that comprehensive studies addressing variables such as psychological well-being, stress, anxiety, self-regulation capacity, and sustainable healthy eating habits in conjunction are notably limited. For instance, several studies have demonstrated associations between food addiction and psychological distress, particularly depression and anxiety [14], while others have examined the role of self-regulation in maladaptive eating behaviors [15] or the link between sustainable dietary practices and psychological well-being [16]. However, these strands of evidence have rarely been integrated into a single model that simultaneously captures the interplay of all these variables. In this context, the present study specifically aims (i) to determine the direct associations between depression, anxiety, and stress with food addiction symptoms; (ii) to examine whether reduced self-regulation mediates the relationship between psychological distress and maladaptive eating behaviors; and (iii) to evaluate whether adherence to sustainable healthy eating practices moderates the impact of psychological distress on food addiction. Through the use of structural equation modeling, the study examines three primary components: first, the direct effects of the subcomponents of psychological distress on food addiction; second, the indirect effects of reduced self-regulation on the transformation of psychological distress into maladaptive eating behaviors; and third, the possible moderating role of strong sustainable eating habits in weakening or strengthening this relationship. By quantifying both direct and indirect effect sizes among the variables, the study provides a more integrated model to explain the biopsychosocial mechanisms of food addiction. The findings are expected to contribute to more accurate identification of individual risk factors and to support the development of effective, evidence-based intervention strategies that can be applied at the societal level.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted over a six-week period between March and May 2025 in all three community health centers located in Elazığ, Turkey. These centers provide primary healthcare services and serve a diverse population, making them suitable settings for community-based research. Data collection was performed through structured face-to-face interviews, administered by trained researchers following standardized protocols to ensure accuracy and reliability. Participants were approached after their medical appointments and invited to a designated private room within the health centers, where the study was explained in detail and written informed consent was obtained. Ethical approval was obtained from **BLINDED** University Non-Interventional Ethics Committee (Approval No: 2025/04–22). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participant rights, voluntary participation, and data confidentiality. Before data collection, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, emphasizing their right to withdraw at any stage without consequence.

Participants

A total of 985 individuals between 18 and 59 years of age participated in the study. Inclusion criteria required participants to be cognitively capable of completing the questionnaire and willing to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included individuals with severe psychiatric or neurological conditions, extreme body composition values, recent pregnancy-related conditions, ongoing use of nutritional supplements, use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications within the last six months, adherence to restrictive dietary patterns, multiple chronic diseases, or any other clinically significant systemic disorders.

To enhance transparency regarding participant flow, 1296 individuals were initially invited to participate. Of these, 122 declined participation, 29 were classified as morbidly obese (BMI > 45.0 kg/m²), 52 reported current use of nutritional supplements, and 108 had multiple chronic diseases. After applying these exclusions, 985 participants were included in the final analysis.

Sample size estimation was conducted a priori using G*Power 3.1, based on reference studies evaluating the associations between psychological factors and food addiction [14]. Assuming a small-to-moderate effect size (r = 0.15), α = 0.05, and desired power (1–β) = 0.95, the required sample size was estimated as approximately n = 572. To ensure robustness, we targeted a larger sample. The final analytic sample of 985 participants substantially exceeded this threshold, providing a statistical power of 0.99, thus ensuring reliable detection of even small-to-moderate associations.

Data collection and instruments

A structured questionnaire was used to obtain data on demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, anthropometric measurements, and validated psychometric scales assessing eating behaviors and psychological states. The questionnaire recorded demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and education level, as well as anthropometric measurements (height, weight, waist circumference) using standardized protocols to ensure accuracy. Information regarding lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity was also collected. Chronic disease status was ascertained based on self-report.

Depression anxiety stress scale-21 (DASS-21)

Psychological distress was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), a widely validated 21-item self-report measure. Participants rated each item on a four-point Likert scale, indicating how much each statement applied to them over the past week. The scale provides three subscale scores (depression, anxiety, and stress), with higher scores reflecting greater symptom severity [17]. In this study, DASS-21 subscale scores were treated as continuous variables, without classification into severity categories. The Turkish version of the DASS-21 has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeding 0.80 for all subscales, supporting its reliability and cultural applicability in Turkish populations [18].

Brief self-control scale (BSCS)

The Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS), originally developed by Tangney et al. [19] was adapted to Turkish by Nebioğlu et al. (2012) to measure individuals’ capacity to regulate their own thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Although the original scale contains 13 items, the Turkish validation comprises 9 items, each rated on a five-point Likert-type scale. Higher total scores indicate stronger self-control. In the Turkish adaptation study, the internal consistency coefficient (cronbach’s alpha) was 0.83, and the test–retest reliability over a three-week interval was 0.88, suggesting robust psychometric properties [20].

Sustainable and healthy eating (SHE)

The Sustainable and Healthy Eating (SHE) Behaviors Scale, originally developed by Żakowska-Biemans et al., was adapted and validated for the Turkish adult population by Köksal et al. [21]. The scale consists of 34 items across eight subdimensions, including Healthy and Balanced Nutrition, Quality Labels, Meat Reduction, Local Food, Low Fat, Animal Welfare, and Seasonal Foods, with responses rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate stronger adherence. The Turkish validation study demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.912 for the overall scale and subscale-specific values ranging from 0.764 to 0.901. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) revealed a seven-factor structure explaining 67% of the total variance, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed good model fit (χ²/SD = 2.593, CFI = 0.915, RMSEA = 0.067). Additionally, test–retest reliability yielded an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.832, affirming the robustness of the scale for evaluating sustainable and healthy eating behaviors in the Turkish adult population [21].

Yale food addiction scale (YFAS)

Food addiction was assessed using the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), originally developed by Gearhardt et al. [11] and validated for Turkish use by Buyuktuncer et al. [22]. The scale was designed to evaluate addictive-like eating behaviors based on criteria adapted from the DSM-IV substance dependence model. The YFAS modifies the seven core symptoms of substance dependence to assess food addiction over the past 12 months. These symptoms include: (1) consuming food in larger amounts and for longer periods than intended, (2) repeated unsuccessful attempts to reduce or control intake, (3) excessive time spent obtaining, consuming, or recovering from food, (4) neglecting social, occupational, or recreational activities due to eating, (5) continued consumption despite awareness of adverse consequences, (6) increased tolerance requiring greater amounts of food to achieve the same effect, and (7) withdrawal-like symptoms upon reducing intake. Each of the seven symptom domains in the YFAS is scored as 0 (absent) or 1 (present). Two scoring methods were used: (1) a continuous symptom count score, obtained by summing the scores across all seven symptom domains, providing a numerical measure of food addiction severity, and (2) a binary classification, where individuals meeting ≥ 3 symptoms along with clinically significant impairment or distress were categorized as having food addiction (1: present, 0: absent). This approach allows for both severity-based (continuous) and diagnostic (categorical) assessments of food addiction.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version of 22) and JASP (Version of 0.19.3). Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, with continuous data reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical data as frequencies and percentages (n, %). The raincloud plots were used to visualize the distribution of depression, anxiety, distress, self-control, and sustainable and healthy eating (SHE) scores between individuals with and without food addiction. Independent t-tests were used to compare these continuous variables, while Pearson’s chi-square test was applied to categorical variables. Effect sizes were reported as Cohen’s d for continuous variables and Cramér’s V for categorical variables, with effect size interpretations as follows: small (Cramér’s V = 0.10–0.29), moderate (0.30–0.49), and strong (≥ 0.50). To assess associations between psychological distress, self-control, SHE, and food addiction, correlation analysis was conducted using JASP, and results were visualized with a heatmap correlation matrix. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were classified as weak (0.10–0.29), moderate (0.30–0.49), and strong (≥ 0.50) [23].

Following the correlation analysis, logistic regression models were conducted to examine the predictive value of depression, anxiety, distress, self-control, and SHE on food addiction, adjusting for age and BMI. For these analyses, the categorical YFAS classification (dependence present/absent) was applied. Model fit indices were assessed using Deviance, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), likelihood ratio test (Δχ²), and Nagelkerke R². Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and Wald test values were reported for each predictor, with higher OR values indicating a greater likelihood of food addiction. Additionally, model performance metrics were evaluated, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1 score [23]. To enhance visualization, inferential plots illustrating the logistic regression results were generated in JASP. Potential confounders were identified a priori from the literature and based on observed associations. Variables with at least moderate effect sizes or that materially changed model estimates were considered for inclusion. Based on these criteria, age and BMI were retained in the adjusted model, while sex and other sociodemographic variables did not materially alter the results and were therefore not included to maintain model parsimony.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to evaluate the direct and indirect relationships between depression, anxiety, distress, self-control, sustainable and healthy eating (SHE), and food addiction. In these analyses, the continuous YFAS symptom-count score—reflecting addiction severity—was used. A path diagram was constructed to illustrate standardized regression coefficients (β) for each relationship, with self-control as the first mediator and SHE as the second mediator, linking psychological distress to food addiction. The model tested both direct effects of depression, anxiety, and distress on food addiction and indirect effects through self-control and SHE. Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was used for parameter estimation, with significance determined via bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (95% CI, 5,000 resamples). The fit of the SEM model was evaluated using Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), with CFI/TLI values >0.90, RMSEA < 0.08, and SRMR < 0.05 indicating an acceptable model fit. Standardized path coefficients were reported along with standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals (CI), z-values, and p-values to assess the strength and significance of each association. Additionally, explanatory power was evaluated using R² values, indicating the proportion of variance explained for each dependent variable in the model. The analysis also examined mediation effects, assessing whether self-control and SHE significantly explained the relationships between psychological distress and food addiction. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant [23].

Results

The comparison of general characteristics between individuals with and without food addiction, as assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale, revealed significant differences across several variables (Table 1). Participants with food addiction were younger (25.9 ± 9.6 vs. 30.1 ± 10.9 years, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.39) and had a higher prevalence of high school education (29.1% vs. 22.0%, p = 0.003). Alcohol consumption was significantly more common in the food addiction group (21.8% vs. 10.5%, p < 0.001), and they had a higher prevalence of chronic disease (26.2% vs. 18.4%, p = 0.004). Mean BMI (24.9 ± 4.3 vs. 23.6 ± 3.9 kg/m², p < 0.001, cohen’s d = 0.32) and waist circumference (83.8 ± 15.7 vs. 79.9 ± 14.3 cm, p < 0.001, cohen’s d = 0.26) were significantly higher in the food addiction group. Additionally, a lower proportion of individuals with food addiction were physically active (28.2% vs. 21.7%, p = 0.022). These findings suggest that food addiction is associated with younger age, higher BMI and waist circumference, increased alcohol use, greater prevalence of chronic disease, and lower physical activity levels.

Table 1.

Comparison of general characteristics between individuals with and without food addiction based on the Yale food addiction scale

| Total (n = 985) | No Addicition (n = 641) | Addicition (n = 344) | Effect size/p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.8 ± 10.9 | 30.1 ± 10.9 | 25.9 ± 9.6 | 0.59/< 0.001*** |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 648 (66.5%) | 219 (34.2%) | 118 (34.3%) | 0.002/0.966 |

| Male | 337 (33.5%) | 422 (65.8%) | 226 (65.7%) | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 132 (13.4%) | 101 (15.7%) | 31 (9.0%) | 0.120/0.003** |

| High school | 241 (24.5%) | 141 (22.0%) | 100 (29.1%) | |

| Associate degree | 133 (13.5%) | 80 (12.5%) | 53 (15.4%) | |

| Undergraduate | 479 (48.6%) | 319 (49.8%) | 160 (46.5%) | |

| Smoke | ||||

| User | 314 (31.9%) | 212 (33.1%) | 102 (29.7%) | 0.060/ 0.166 |

| Non-user | 626 (63.5%) | 405 (63.2%) | 221 (64.2%) | |

| Former | 45 (4.6%) | 24 (3.7%) | 21 (5.1%) | |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 142 (14.4%) | 67 (10.5%) | 75 (21.8%) | 0.154/< 0.001*** |

| No | 843 (85.6%) | 574 (89.5%) | 269 (78.2%) | |

| Chronic disease | ||||

| No | 777 (78.9%) | 523 (81.6%) | 254 (73.8%) | 0.091/0.004** |

| Yes | 208 (21.1%) | 118 (18.4% | 90 (26.2%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 4.1 | 23.6 ± 3.9 | 24.9 ± 4.3 | 0.427/< 0.001*** |

| WC (cm) | 81.1 ± 14.8 | 79.9 ± 14.3 | 83.8 ± 15.7 | 0.261/< 0.001*** |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Sedentary | 749 (76.1%) | 502 (78.3%) | 247 (71.8%) | 0.073/0.022* |

| Active | 236 (23.9%) | 139 (21.7%) | 97 (28.2%) | |

BMI, Body mass index; WC, waist circumference. Group comparisons were conducted using independent t-tests for continuous variables, with Cohen’s d reported as the effect size. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test, with Cramér’s V as the effect size. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

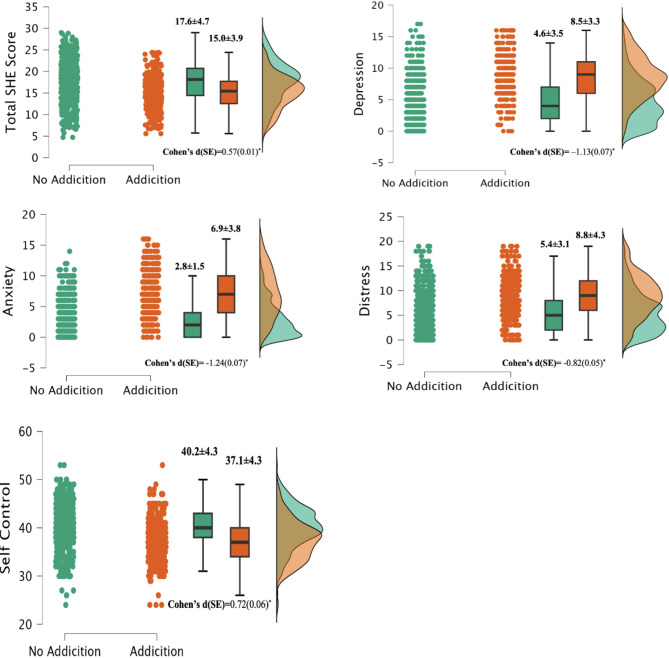

Figure 1 presents the comparison of total sustainable healthy eating (SHE) score, depression, anxiety, distress, and self-control between individuals with and without food addiction using raincloud plots. The all variables exhibited statistically significant differences between the groups. The total SHE score was lower in the food addiction group (15.0 ± 3.9) compared to the non-addiction group (17.6 ± 4.7), with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d= -0.57), suggesting a meaningful reduction in sustainable healthy eating behaviors among individuals with food addiction. Depression, anxiety, and distress scores were notably higher in the food addiction group, with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d= -1.13, -1.24, and − 0.82, respectively), indicating strong associations between negative psychological states and food addiction. Self-control was lower in individuals with food addiction (37.1 ± 4.3) compared to those without (40.2 ± 4.3), with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.72). These findings highlight the considerable psychological and behavioral differences between individuals with and without food addiction.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of Total Sustainable Healthy Eating Score, Depression, Anxiety, Distress, and Self-Control Between Individuals With and Without Food Addiction. Raincloud plots display the distribution, boxplots, and individual data points for Total SHE Score, Depression, Anxiety, Distress, and Self-Control across food addiction groups. Values are presented as mean ± SD, and comparisons were conducted using independent t-tests with Cohen’s d as the effect size. Effect sizes were classified as small (d = 0.2–0.49), moderate (d = 0.5–0.79), and large (d ≥ 0.80).SHE, Sustainable Healthy Eating. *p<0.05

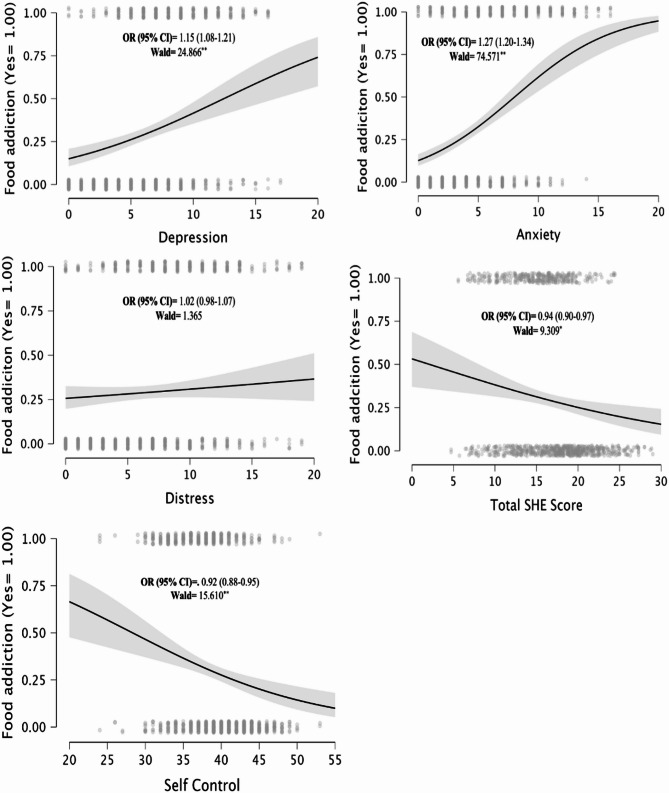

Logistic regression analysis, adjusted for age and BMI, demonstrated significant associations between psychological and behavioral factors and food addiction risk (Fig. 2). Higher depression (OR[95% CI] = 1.15 [1.08–1.21], Wald = 24.866) and anxiety (OR[95% CI] = 1.27 [1.20–1.34], Wald = 74.571) were positively associated with food addiction, with anxiety exhibiting the strongest effect. Distress level was not significantly associated with the risk of food addiction (OR [95% CI] = 1.02 [0.98–1.07], p > 0.05). In contrast, higher total SHE scores (OR[95% CI] = 0.94 [0.90–0.97], Wald = 9.309) and greater self-control (OR[95% CI] = 0.92 [0.88–0.95], Wald = 15.610) were negatively associated, indicating that adherence to sustainable healthy eating behaviors and greater self-regulation tend to be linked with lower food addiction scores. The final model significantly improved fit compared to the null model (Δχ²= 378.793, p < 0.001) and explained 44% of the variance in food addiction (Nagelkerke R²= 0.440). Model performance was robust, with high classification accuracy (78.4%), strong discriminative ability (AUC = 0.849), and high specificity (86.4%), although sensitivity was moderate (63.4%) (Table 2). These findings underscore the associations between psychological distress, self-regulation, and food addiction, reinforcing the necessity of integrating mental health and dietary quality into preventive and therapeutic research perspectives.

Fig. 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis of the Associations Between Psychological Factors, Sustainable Healthy Eating, and Self-Control With Food Addiction. Inferential plots illustrate the logistic regression relationships between depression, anxiety, distress, total sustainable healthy eating (SHE) score, and self-control with food addiction, adjusted for age and BMI. The solid black line represents the predicted probability of food addiction, with the shaded area indicating the 95% confidence interval (CI). Odds ratios (OR) and Wald statistics are reported for each predictor, with higher OR values indicating greater likelihood of food addiction. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 2.

Model summary and performance metrics of the logistic regression analysis for food addiction

| Model summary | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Deviance | AIC | BIC | Δχ² | Nagelkerke | p |

| M0 | 1274.53 | 1276.52 | 1281.40 | |||

| M1 | 890.74 | 857.73 | 837.12 | 378.79 | 0.440 | < 0.001 |

| Performance metrics | ||||||

| AUC | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Presicion | F1 score | |

| Value | 0.849 | 0.784 | 0.634 | 0.864 | 0.715 | 0.672 |

M₀ represents the null model, while M₁ includes depression, anxiety, distress, total sustainable healthy eating (SHE) score, and self-control, adjusted for age and BMI. Lower AIC and BIC values indicate better model fit. The likelihood ratio test (Δχ²) assesses model improvement, and Nagelkerke R² represents the explained variance. Performance metrics include classification accuracy, AUC (area under the curve), sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score

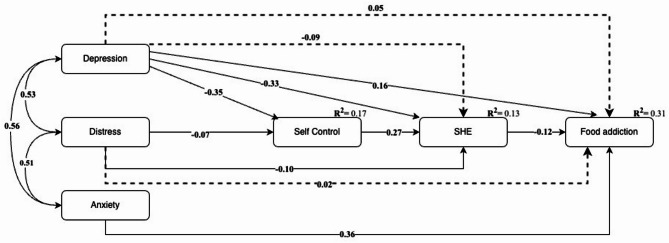

The structural equation modeling results (Fig. 3) illustrate the direct and indirect relationships between depression, distress, anxiety, self-control, SHE, and food addiction, with all reported paths being statistically significant. Depression, distress, and anxiety were positively correlated, with depression exerting direct negative effects on both self-control (β= -0.35) and SHE (β= -0.33), suggesting that higher depression levels are associated with lower self-regulation and adherence to sustainable eating behaviors. Anxiety exhibited a significant direct effect on food addiction (β = 0.36), marking it as a key psychological predictor. Self-control played a mediating role, negatively associated with food addiction (β= -0.10) while positively influencing SHE (β = 0.27), highlighting its regulatory function in dietary behavior. SHE was inversely associated with food addiction (β= -0.12), further supporting the protective role of sustainable eating patterns. The indirect pathways (dashed lines) confirmed that depression and distress contribute to food addiction through reductions in self-control and sustainable eating practices. Model fit indicators showed satisfactory explanatory power, with self-control (R²= 0.17), SHE (R²= 0.13), and food addiction (R²= 0.31) capturing substantial variance. Supplementary Table presents the standardized path coefficients corresponding to the structural equation model depicted in Fig. 3, summarizing the direct and indirect relationships among psychological factors, self-control, sustainable healthy eating (SHE), and food addiction.

Fig. 3.

Path Analysis of the Relationships Between Psychological Factors, Self-Control, Sustainable Healthy Eating, and Food Addiction. The structural equation model illustrates the direct and indirect pathways between depression, distress, anxiety, self-control, sustainable healthy eating (SHE), and food addiction. Solid arrows represent statistically significant direct effects, while dashed arrows indicate indirect effects through mediating variables. Bidirectional arrows denote correlations between psychological factors. The numbers on the paths correspond to standardized regression coefficients (β), and R² values indicate the explained variance for each endogenous variable. All reported relationships are statistically significant

The path analysis results (Table 3) demonstrate that heightened distress (β [95% CI] = 0.28 [0.22–0.34], z = 9.708, p < 0.001) and depression (β [95% CI] = 0.16 [0.08–0.23], z = 4.864, p < 0.001) each revealed significant direct effects on food addiction. Indirect effects highlighted self-control as a key mediator. Depression significantly affected food addiction through self-control (β [95%CI] = 0.04 [0.02–0.06], z = 3.322, p < 0.001), whereas its indirect effect via SHE alone was not significant (β [95%CI] = 0.02 [− 0.01–0.02], p = 0.117). Distress also exerted an indirect effect through self-control (β = 0.05 [0.03–0.07], z = 5.675, p < 0.001), but not through SHE alone (β [95%CI] = 0.01 [− 0.00–0.01], z = 1.361, p = 0.173). When self-control and SHE were considered jointly, the total indirect effect of stress reached β = 0.06 (z = 6.744, 95%CI = 0.03–0.10, p < 0.001). Similarly, depression’s combined indirect effect through both self-control and SHE was strongest (β[95%CI] = 0.07[0.05–0.11], z = 8.012, p < 0.001). Anxiety’s total indirect effect was negligible (β [95%CI] = − 0.00[− 0.04–0.01], p = 0.975), reinforcing that its influence on food addiction is primarily direct. The fit indices further supported the robustness of the model, with a comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.94, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.92, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of 0.044, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.042 (95%CI= [0.04–0.05], all indicating an excellent fit according to conventional cutoffs. The SEM examining psychological factors, self-control, SHE, and food addiction demonstrated excellent fit (CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.044, RMSEA = 0.042).

Table 3.

Direct, indirect, and total indirect effects of psychological factors on food addiction mediated by Self-Control and sustainable healthy eating (SHE)

| Predictor | Effect type | Estimate (SE) | z value | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression → Food addiction | Direct effects | 0.16 (0.02) | 4.864 | 0.08–0.23 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety → Food addiction | 0.36 (0.04) | 10.961 | 0.29–0.42 | < 0.001 | |

| Distress → Food addiction | 0.28 (0.02) | 9.708 | 0.22–0.34 | < 0.001 | |

| Depression → Self control → Food addiction | Indirect effects | 0.04 (0.01) | 3.322 | 0.02–0.06 | < 0.001 |

| Depression → SHE → Food addiction | 0.02 (0.00) | 1.568 | -0.01-0.02 | 0.117 | |

| Anxiety → Self control → Food addiction | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.676 | -0.01-0.01 | 0.499 | |

| Anxiety → SHE → Food addiction | -0.01 (0.00) | -1.135 | -0.01-0.00 | 0.256 | |

| Distress → Self control → Food addiction | 0.05 (0.00) | 5.675 | 0.03–0.07 | < 0.001 | |

| Distress → SHE → Food addiction | 0.01 (0.00) | 1.361 | -0.00-0.01 | 0.173 | |

| Depression → Self control → SHE → Food addiction | Total indirect effects | 0.07 (0.01) | 8.012 | 0.05–0.11 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety → Self control → SHE → Food addiction | -0.00 (0.00) | -0.03 | -0.04-0.01 | 0.975 | |

| Distress → Self control → SHE → Food addiction | 0.06 (0.01) | 6.744 | 0.03–0.10 | < 0.001 |

Values represent standardized regression coefficients (β) with standard errors (SE) in parentheses. Direct effects indicate the immediate influence of independent variables on food addiction. Indirect effects represent mediated pathways through self-control and/or SHE, while total indirect effects summarize cumulative mediating influences. Statistically significant pathways (p < 0.05) are highlighted. CI = Confidence Interval

Discussion

The most striking finding of this study was that anxiety emerged as the strongest direct psychological predictor of food addiction, whereas the effects of depression and distress were mainly indirect through reductions in self-control. Self-control itself demonstrated a dual protective function: it directly reduced addictive eating symptoms and simultaneously promoted sustainable healthy eating behaviors that lowered vulnerability. Consistent with prior research, individuals with food addiction reported higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, alongside lower scores in self-control and sustainable eating, highlighting the emotional and regulatory challenges they face. Structural equation modeling further confirmed that self-control and sustainable eating act as sequential mediators in the stress–food addiction pathway, underscoring their central role in shaping both psychological and behavioral outcomes.

Anxiety and depression are among the primary psychological determinants of food addiction [24, 25]. Huang and colleagues reported a direct association between anxiety and food addiction, highlighting that this relationship is negatively influenced by unhealthy dietary choices. Increased anxiety levels tend to drive individuals toward highly rewarding and comforting foods, thereby reinforcing the addiction cycle [24]. Similarly, Wattick et al. emphasized that both anxiety and depression are linked to poor dietary quality and food addiction [7].

Although depression is also known to influence eating behaviors, its effects are generally reported to occur through more indirect pathways. For instance, depression in individuals with obesity has been suggested to trigger addiction-related eating behaviors. Conversely, frequent consumption of highly processed foods with addictive potential has been proposed to increase the risk of developing depression [26–28]. Neurobiological studies further indicate that both depression and food addiction share common alterations in the brain’s reward circuitry, including dopaminergic and serotonergic dysregulation, which may explain their bidirectional association. Depressive symptoms such as anhedonia and emotional dysregulation increase vulnerability to compulsive eating as a maladaptive coping strategy, while repeated exposure to hyperpalatable foods may exacerbate depressive states by reinforcing these neural imbalances [29, 30]. Epidemiological evidence also supports this connection, showing higher prevalence of food addiction symptoms among individuals with clinical depression, even after adjusting for obesity and other confounders [28, 31]. Furthermore, the study by Brytek-Matera and colleagues found that food addiction scores were particularly pronounced among individuals with high levels of anxiety [10]. These findings suggest that anxiety may play a stronger role than other mood disorders in provoking maladaptive eating behaviors and food addiction.

The persistent worry and intense stress accompanying anxiety are thought to directly influence craving behaviors, thereby contributing to food addiction. This may be explained by the inherent characteristics of anxiety, such as heightened physiological arousal and the urgent drive for immediate relief. In this context, eating, particularly the consumption of highly palatable foods, can temporarily reduce anxiety through its anxiolytic effects, reinforcing a direct link between anxiety and food addiction without the involvement of mediating mechanisms. Additionally, the tendency of individuals with high anxiety to use food consumption as both an avoidance strategy and a self-regulatory mechanism during stressful situations further supports this notion [24, 32].

Although chronic stress is known to influence food addiction, this relationship is reported to occur more indirectly through anxiety. Stress-related triggers have frequently been shown to exacerbate anxiety symptoms, which in turn increase food addiction behaviors [33]. The findings of Gordon and colleagues also support this perspective, emphasizing that food addiction prevalence is higher among individuals reporting elevated anxiety levels, whereas the impact of stress appears relatively limited [34].

When considering the existing literature alongside the findings of this study, it becomes evident that anxiety plays a more decisive role in triggering food addiction compared to depression and stress. The dominant effect of anxiety on eating behaviors develops through interactions with emotional distress, maladaptive coping strategies, and difficulties in psychological regulation. Therefore, interventions targeting food addiction should focus on anxiety-specific psychological components, necessitating the development of more specific and individualized strategies that prioritize psychological well-being rather than relying solely on general mental health approaches.

Food addiction is a complex behavioral issue directly linked not only to psychological factors but also to sustainable dietary practices and self-regulatory capacities. Individuals prone to food addiction often exhibit a marked preference for highly processed, energy-dense, and nutrient-poor foods, which consequently reduces the consumption of essential components of sustainable diets such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains [35, 36]. This dietary pattern not only contributes to adverse health outcomes at the individual level but also perpetuates intensive agricultural systems dependent on industrial production practices. These systems accelerate environmental resource depletion, diminish biodiversity, and undermine long-term sustainability goals [37]. Therefore, food addiction should be understood not merely as an issue of individual eating behavior but as a multidimensional public health concern with significant implications for both population health and ecological sustainability.

The relationship between food addiction and sustainable dietary practices extends beyond simple food preferences to encompass the impact of addictive eating behaviors on self-regulation mechanisms. Intense cravings for highly palatable, energy-dense foods can reinforce binge eating patterns, perpetuating the cyclical nature of food addiction and sustaining unhealthy eating habits [38]. Such addiction-like urges toward specific foods not only undermine individual efforts to adhere to balanced, health-promoting diets but also hinder progress toward broader environmental sustainability goals [2, 39]. Within this framework, self-control emerges as a pivotal factor in both managing food addiction and promoting healthier eating behaviors. Individuals who identify as food-addicted often report impaired behavioral regulation in response to food cues [6]. While low self-control facilitates poor dietary choices and contributes to the persistence of compulsive eating cycles, enhanced self-regulatory capacities enable resistance to unhealthy food stimuli and foster adherence to sustainable dietary patterns [40, 41].

A bidirectional and complex interplay exists between food addiction, self-control, and sustainable eating behaviors. Food addiction undermines individuals’ self-regulatory capacities, thereby perpetuating unhealthy eating habits, whereas enhancing self-control can interrupt this cycle and promote the adoption of sustainable, healthy dietary practices. Consistent with this perspective, the present study found that individuals classified as food-addicted exhibited significantly lower scores in both sustainable healthy eating and self-control. These findings are in line with existing literature, as previous research has shown that adolescents with lower self-control display higher food addiction symptoms [42], that healthy lifestyle factors including greater consumption of nutritious foods are inversely related to food addiction risk in young adults [43], and that reduced cognitive control and greater emotional eating are closely tied to uncontrolled eating and higher food addiction scores [44].

Examining the relationship between food addiction, self-control, and sustainable eating through the mediating role of depression may provide an important framework for determining the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Individuals with food addiction are generally reported to have higher levels of depression. This suggests that depression reinforces food addiction, creating a cyclical interaction that triggers adverse health outcomes (Burrows et al., 2018). Increasing dietary adherence has been emphasized as having positive effects on mental well-being, highlighting the necessity of addressing both nutritional and mental health dimensions together in therapeutic approaches targeting food addiction [42].

However, low levels of self-control are frequently associated with unhealthy eating habits, which can exacerbate depressive symptoms. Indeed, research has shown that individuals at risk for mental health issues often struggle with impulse control, making it difficult for them to maintain sustainable dietary practices [45].

The promotion of sustainable eating becomes more complex due to the psychological barriers posed by food addiction and depression. Although diets high in nutrient quality have positive health effects, such diets do not always align with individuals’ short-term preferences and immediate impulses. This discrepancy is particularly pronounced among individuals with low self-control (Pérignon et al., 2016). Therefore, the widespread adoption of sustainable eating behaviors necessitates an understanding and consideration of these psychological variables. Implementing environmental modifications that support healthy choices can be effective in both mitigating the effects of depression and enhancing self-control, ultimately encouraging healthier dietary decisions [46, 47].

The findings of this study indicate that depression reduces self-control, whereas self-control positively influences sustainable eating behaviors. Additionally, it was observed that as sustainable eating habits increase, levels of food addiction decrease. These results align with existing literature and suggest that depression may increase susceptibility to food addiction while weakening self-control, thereby adversely affecting individuals’ eating behaviors and food choice decisions. Nevertheless, the interpretation of sustainable eating behaviors requires consideration of cultural context, as dietary traditions and food availability differ across regions, shaping how sustainable practices are expressed. In other words, depression acts as a mediator that complicates the relationship between food addiction and self-control, exerting an indirect yet strong influence on eating behaviors. Therefore, designing effective interventions that consider these psychological dimensions is essential for developing sustainable dietary practices that support not only physical health but also mental well-being. A key strength of this study is its comprehensive and integrative approach, simultaneously examining psychological distress, self-control, and sustainable healthy eating within a single model. The relatively large sample size and the use of advanced statistical techniques, including structural equation modeling and logistic regression, further strengthen the reliability and validity of the findings. By quantifying both direct and indirect pathways, this study provides novel insights into the complex psychosocial mechanisms of food addiction, highlighting its value for both theoretical understanding and practical applications.

Although anxiety emerges as a significant predictor of food addiction, no evidence was found supporting a mediating role of self-control or sustainable eating in the relationship between anxiety and food addiction. In contrast, both self-control and sustainable eating behaviors demonstrated significant and strong mediating effects in the relationship between stress and food addiction. Indeed, previous studies have supported the tendency of individuals experiencing high levels of stress to turn to food for emotional regulation purposes [48, 49]. Within this context, self-control emerges as a crucial mediator; individuals with low self-control are more prone to unhealthy and compulsive eating behaviors under stress [14]. Furthermore, increasing knowledge and awareness related to sustainable eating, and promoting healthy food choices free from addictive properties, may play an important role in reducing stress-related tendencies toward food addiction [12, 25]. Indeed, the literature shows that improved nutritional knowledge supports healthier food selections, enabling individuals to better regulate their food intake and thereby reduce the risk of food addiction [50, 51]. Consistent with existing literature, the findings of this study indicate that while self-control and sustainable eating do not mediate the anxiety-food addiction relationship, both variables exhibit significant mediating effects in the stress-food addiction relationship.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study lies in its comprehensive and integrative design, simultaneously examining psychological distress, self-control, and sustainable healthy eating within a single model. The relatively large sample size and the use of advanced statistical techniques, including structural equation modeling and logistic regression, further enhance the robustness, reliability, and validity of the findings. By quantifying both direct and indirect pathways, this study provides novel insights into the complex psychosocial mechanisms of food addiction, highlighting its theoretical and practical significance.

The present study uniquely was integrated psychological, behavioral, and dietary dimensions in examining food addiction, employing rigorous statistical techniques, including logistic regression and structural equation modeling, to provide robust, multidimensional insights. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the cross-sectional study design prevents determination of causality; longitudinal approaches would be beneficial to confirm temporal directions among variables. Secondly, the self-report nature of the assessments may introduce social desirability and recall biases, particularly concerning sensitive constructs such as addictive behaviors and psychological distress. Thirdly, the recruitment from community health centers within a single geographical region (Elazığ, Turkey) limits the external validity, necessitating caution in generalizing findings to other populations. Lastly, potential confounders not assessed in this study—such as genetic predispositions, socioeconomic background, and specific neurobiological markers—may influence the observed relationships. Future research should aim to address these limitations by utilizing longitudinal or experimental designs, objective measures, and broader demographic sampling.

Conclusion

This study reveals the complex relationships between food addiction, psychological conditions, self-control, and sustainable eating behaviors. The findings indicate that anxiety plays a more decisive role in triggering food addiction compared to depression and stress, while self-control and sustainable dietary behaviors significantly mediate the relationship between stress and food addiction. Strengthening self-control and promoting sustainable eating habits are critical in reducing the risk of food addiction. The results provide valuable insights into the multidimensional nature of psychological processes affecting eating behaviors and may serve as a guide for developing effective strategies in public health and nutrition education interventions. From a clinical perspective, incorporating routine screening for food addiction and anxiety symptoms into mental health and nutrition services may facilitate early identification of at-risk individuals and the delivery of targeted interventions. On a public health policy level, integrating sustainable nutrition education with mental health promotion in schools, workplaces, and community programs could reduce the burden of food addiction while fostering healthier and more sustainable dietary patterns in the population. Community-based initiatives, such as school-based workshops, workplace wellness programs, and local public health campaigns, may serve as practical platforms to foster self-control skills and promote sustainable food choices, thereby mitigating the risk of food addiction at the population level. Accordingly, a comprehensive approach that integrates individual psychological support with environmental and educational measures is essential to enhance both mental well-being and sustainable dietary practices. However, given the cross-sectional design of this study, causal inferences cannot be made. Longitudinal research is required to confirm the directionality of the observed associations. Future research should further explore the long-term effects of these relationships and evaluate intervention methods in greater detail.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the students of the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at Fırat University for their invaluable assistance in data collection, and all study participants for their contributions.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. TGÜ: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Fırat University Non-Interventional Ethics Committee (Approval No: 2025/04–22). All participants were fully informed about the study procedures, and written informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their data. Participants retained the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequence.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vasiliu O. Frontiers | current status of evidence for a new diagnosis: food Addiction-A literature review. [cited 2025 Aug 15]; 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.824936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Neff KMH, Fay A, Saules KK, Foods. and Nutritional Characteristics Associated With Addictive-Like Eating. Psychol Rep [Internet]. SAGE Publications Inc; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 15];125:1937–56. 10.1177/00332941211014156 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Yu Z, Muehleman V. Eating Disorders and Metabolic Diseases. Volume 20. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2023. p. 2446. [cited 2025 Sep 24];. 10.3390/ijerph20032446. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gaspar-Pérez A, Granero R, Fernández-Aranda F, Rosinska M, Artero C, Ruiz-Torras S et al. Exploring Food Addiction Across Several Behavioral Addictions: Analysis of Clinical Relevance. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 16];17:1279. 10.3390/nu17071279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Maynard ML, Quenneville S, Hinves K, Talwar V, Bosacki SL. Interconnections between emotion Recognition, Self-Processes and psychological Well-Being in Adolescents. Adolescents [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 16];3:41–59. 10.3390/adolescents3010003

- 6.Meadows A, Nolan LJ, Higgs S. Self-perceived food addiction: Prevalence, predictors, and prognosis. Appetite [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 16];114:282–98. 10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wattick RA, Olfert MD, Claydon E, Hagedorn-Hatfield RL, Barr ML, Brode C. Early life influences on the development of food addiction in college attending young adults. Volume 28. Springer; 2023. pp. 1–13. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. 10.1007/s40519-023-01546-3. Eat Weight Disord - Stud Anorex Bulim Obes [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Conceição ISR, Garcia-Burgos D, de Macêdo PFC, Nepomuceno CMM, Pereira EM, de Cunha C. M, et al. Habits and persistent food restriction in patients with anorexia nervosa: A scoping Review. Behav sci [Internet]. Volume 13. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2023. p. 883. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. 10.3390/bs13110883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vermeulen E, Stronks K, Snijder MB, Schene AH, Lok A, de Vries JH, et al. A combined high-sugar and high-saturated-fat dietary pattern is associated with more depressive symptoms in a multi-ethnic population: the HELIUS (Healthy life in an urban Setting) study. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2017;20:2374–82. 10.1017/S1368980017001550. [cited 2025 Sep 24];. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brytek-Matera A, Obeid S, Akel M, Hallit S. How Does Food Addiction Relate to Obesity? Patterns of Psychological Distress, Eating Behaviors and Physical Activity in a Sample of Lebanese Adults: The MATEO Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 15];18:10979. 10.3390/ijerph182010979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 15];52:430–6. 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Moschis GP, Mathur A, Shannon R. Toward Achieving Sustainable Food Consumption: Insights from the Life Course Paradigm. Sustainability [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 15];12:5359. 10.3390/su12135359.

- 13.Huang Q, Liu H, Suzuki K, Ma S, Liu C. Linking what we eat to our mood: A review of Diet, dietary Antioxidants, and Depression. Antioxidants [Internet]. Volume 8. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2019. p. 376. [cited 2025 Sep 24];. 10.3390/antiox8090376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Luo Y, Zhang Y, Sun X, Dong J, Wu J, Lin X. Mediating effect of self-control in the relationship between psychological distress and food addiction among college students. Appetite [Internet]. 2022;179:106278. 10.1016/j.appet.2022.106278. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy CM, MacKillop J. Chapter 7 - Food addiction and self-regulation. In: Cottone P, Sabino V, Moore CF, Koob GF, editors. Compuls eat behav food addict [Internet]. Academic; 2019. pp. 193–216. [cited 2025 Sep 24]. 10.1016/B978-0-12-816207-1.00007-X.

- 16.Lo Dato E, Gostoli S, Tomba E. Psychological Well-Being and Dysfunctional Eating Styles as Key Moderators of Sustainable Eating Behaviors: Mind the Gap Between Intention and Action. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 24];17:2391. 10.3390/nu17152391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 1997;35:79–89. 10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00068-X. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sariçam H. The psychometric properties of Turkish version of depression anxiety stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in community and clinical samples. J Cogn-Behav Psychother Res [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 15];1. 10.5455/JCBPR.274847

- 19.Tangney JP, Boone AL, Baumeister RF. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Self-Regul Self-Control. Routledge; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Nebioglu M, Konuk N, Akbaba S, Eroglu Y. The Investigation of Validity and Reliability of the Turkish Version of the Brief Self-Control Scale. Volume 22. Taylor & Francis; 2012. pp. 340–51. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. 10.5455/bcp.20120911042732. Klin Psikofarmakol Bül-Bull Clin Psychopharmacol [Internet].

- 21.Köksal E, Bilici S, Dazıroğlu MEÇ, Gövez NE. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Sustainable and Healthy Eating Behaviors Scale | British Journal of Nutrition. Camb Core [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 15]; 10.1017/S0007114522002525 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Buyuktuncer Z, Akyol A, Ayaz A, Nergiz-Unal R, Aksoy B, Cosgun E, et al. Turkish version of the Yale food addiction scale: preliminary results of factorial structure, reliability, and construct validity. J Health Popul Nutr [Internet] BioMed Cent. 2019;38:1–8. 10.1186/s41043-019-0202-4. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniel WW, Cross CL, Biostatistics. A foundation for analysis in the health sciences. Wiley; 2018.

- 24.Huang X, Wu L, Gao L, Yu S, Chen X, Wang C, et al. Impact of Self-Monitoring on weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2021;31:4399–404. 10.1007/s11695-021-05600-w. [cited 2025 Mar 28];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiss D, Brewerton T. Separating the Signal from the Noise: How Psychiatric Diagnoses Can Help Discern Food Addiction from Dietary Restraint. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 15];12:2937. 10.3390/nu12102937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Adjibade M, Julia C, Allès B, Touvier M, Lemogne C, Srour B, et al. Prospective association between ultra-processed food consumption and incident depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. BMC Med [Internet] BioMed Cent. 2019;17:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-019-1312-y. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gómez-Donoso C, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA, Gea A, Mendonça R, de Lahortiga-Ramos D. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of depression in a mediterranean cohort: the SUN project. Eur J Nutr [Internet] Springer. 2019;59:1093–103. 10.1007/s00394-019-01970-1. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burrows T, Kay-Lambkin F, Pursey K, Skinner J, Dayas C. Food addiction and associations with mental health symptoms: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hum Nutr Diet [Internet]. 2018;31:544–72. 10.1111/jhn.12532. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piccinni A, Cargioli C, Oppo A, Vanelli F, Mauri M, Formica V et al. Is Food Addiction a Specific Feature of Individuals Seeking Dietary Treatment from Nutritionists? Clin Neuropsychiatry [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 16];20:486–94. 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20230603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Raghu SV, Bhat R. Chapter 24 - Neurobiology of food addiction. In: Bhat R, editor. Future foods [Internet]. Academic; 2022. pp. 425–31. [cited 2025 Sep 24]. 10.1016/B978-0-323-91001-9.00035-9.

- 31.Pedram P, Wadden D, Amini P, Gulliver W, Randell E, Cahill F, et al. Food addiction: its prevalence and significant association with obesity in the general Population. PLOS ONE [Internet]. Public Libr Sci. 2013;8:e74832. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074832. [cited 2025 Sep 24];. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourdier L, Fatseas M, Maria A-S, Carre A, Berthoz S. The Psycho-Affective roots of obesity: results from a French study in the general Population. Nutrients [Internet]. Volume 12. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020. p. 2962. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. 10.3390/nu12102962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Wei N-L, Quan Z-F, Zhao T, Yu X-D, Xie Q, Zeng J, et al. Chronic stress increases susceptibility to food addiction by increasing the levels of DR2 and MOR in the nucleus accumbens. Volume 15. Dove Medical; 2019. pp. 1211–29. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. 10.2147/NDT.S204818. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gordon EL, Ariel-Donges AH, Bauman V, Merlo LJ. What is the evidence for food addiction? A systematic Review. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 16];10:477. 10.3390/nu10040477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Krupa H, Gearhardt AN, Lewandowski A, Avena NM. Food Addiction. Brain sci [Internet]. Volume 14. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2024. p. 952. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. 10.3390/brainsci14100952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Sengor G, Gezer C. The association between food addiction, disordered eating behaviors and food intake. Rev Nutr [Internet]. 2020;33:e190039. 10.1590/1678-9865202033e190039. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahzad MF, Lee MSW, Hasni MJS, Rashid Y. How does addiction of fast-food turn into anti-consumption of fast-food? The mediating role of health concerns. J Consum Behav [Internet]. 2022;21:697–712. 10.1002/cb.2025. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joyner MA, Gearhardt AN, White MA. Food craving as a mediator between addictive-like eating and problematic eating outcomes. Eat Behav [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 16];19:98–101. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Feng X, Wilson A, Getting, Bigger. Quicker? Gendered socioeconomic trajectories in body mass index across the adult lifecourse: A longitudinal study of 21,403 Australians. [cited 2025 Aug 16]; 10.1371/journal.pone.0141499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Johnson F, Pratt M, Wardle J. Dietary restraint and self-regulation in eating behavior. Int J Obes [Internet] Nat Publishing Group. 2012;36:665–74. 10.1038/ijo.2011.156. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarthy MB, Collins AM, Flaherty SJ, McCarthy SN. Healthy eating habit: A role for goals, identity, and self-control? Psychol mark [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 16];34:772–85. 10.1002/mar.21021

- 42.Leary M, Pursey KM, Verdejo-Garcia A, Burrows TL. Current intervention treatments for food addiction: A systematic Review. Behav sci [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 16];11:80. 10.3390/bs11060080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Vasgare H, Gokhale D, Phalle A, Jadhav S. Assessing the magnitude and lifestyle determinants of food addiction in young adults. Eat Weight Disord - Stud Anorex Bulim Obes [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 24];30:43. 10.1007/s40519-025-01752-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Rossi AA. Tying Food Addiction to Uncontrolled Eating: The Roles of Eating-Related Thoughts and Emotional Eating. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 24];17:369. 10.3390/nu17030369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Teasdale SB, Ward PB, Rosenbaum S, Watkins A, Curtis J, Kalucy M et al. A nutrition intervention is effective in improving dietary components linked to cardiometabolic risk in youth with first-episode psychosis |. Br J Nutr Camb Core [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 16]; 10.1017/S0007114516001033 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Perignon M, Vieux F, Soler L-G, Masset G, Darmon N. Improving diet sustainability through evolution of food choices: review of epidemiological studies on the environmental impact of diets. Nutr Rev [Internet]. 2017;75:2–17. 10.1093/nutrit/nuw043. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minhas J, Mcbride JC. Perceptions of mental health professionals on nutritional psychiatry as an adjunct treatment in mainstream psychiatric settings in new South Wales, Australia. Cureus [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 16]; 10.7759/cureus.56906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Najem J, Saber M, Aoun C, El Osta N, Papazian T, Rabbaa Khabbaz L. Prevalence of food addiction and association with stress, sleep quality and chronotype: A cross-sectional survey among university students. Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2020;39:533–9. 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.02.038. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kayaoğlu K, Göküstün KK, Ay E. Evaluation of the relationship between food addiction and depression, anxiety, and stress in university students: A cross-sectional survey. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs [Internet]. 2023;36:256–62. 10.1111/jcap.12428. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hantira NY, Khalil AI, Saati HS, Ahmed HA, Kassem FK. Food Knowledge, Habits, Practices, and Addiction Among Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Investigation. Cureus [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 16]; 10.7759/cureus.47175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Ünal U. Structural equation modeling as a marketing research tool: A guideline for SEM users about critical issues and problematic practices. J Stat Appl Sci [Internet] Abdulkadir KESKİN. 2021;2:65–77. 10.52693/jsas.1015831. [cited 2025 Apr 10];. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Yu Z, Muehleman V. Eating Disorders and Metabolic Diseases. Volume 20. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2023. p. 2446. [cited 2025 Sep 24];. 10.3390/ijerph20032446. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wattick RA, Olfert MD, Claydon E, Hagedorn-Hatfield RL, Barr ML, Brode C. Early life influences on the development of food addiction in college attending young adults. Volume 28. Springer; 2023. pp. 1–13. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. 10.1007/s40519-023-01546-3. Eat Weight Disord - Stud Anorex Bulim Obes [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moschis GP, Mathur A, Shannon R. Toward Achieving Sustainable Food Consumption: Insights from the Life Course Paradigm. Sustainability [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 15];12:5359. 10.3390/su12135359.

- Nebioglu M, Konuk N, Akbaba S, Eroglu Y. The Investigation of Validity and Reliability of the Turkish Version of the Brief Self-Control Scale. Volume 22. Taylor & Francis; 2012. pp. 340–51. [cited 2025 Aug 15];. 10.5455/bcp.20120911042732. Klin Psikofarmakol Bül-Bull Clin Psychopharmacol [Internet].

- Wiss D, Brewerton T. Separating the Signal from the Noise: How Psychiatric Diagnoses Can Help Discern Food Addiction from Dietary Restraint. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 15];12:2937. 10.3390/nu12102937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wei N-L, Quan Z-F, Zhao T, Yu X-D, Xie Q, Zeng J, et al. Chronic stress increases susceptibility to food addiction by increasing the levels of DR2 and MOR in the nucleus accumbens. Volume 15. Dove Medical; 2019. pp. 1211–29. [cited 2025 Aug 16];. 10.2147/NDT.S204818. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rossi AA. Tying Food Addiction to Uncontrolled Eating: The Roles of Eating-Related Thoughts and Emotional Eating. Nutrients [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 24];17:369. 10.3390/nu17030369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.