Abstract

Sarcopenia, a chronic degenerative condition associated with aging, is characterized by a significant decline in muscle mass and strength. Puerarin, a major active isoflavone extracted from Pueraria lobata, exhibits potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. However, its therapeutic effects on sarcopenia remain unclear. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the therapeutic effects and underlying molecular mechanisms of puerarin in ameliorating sarcopenia in naturally aged mice. Twenty-month-old male C57BL/6 J aged mice were randomly divided into two groups based on body weight: the puerarin group (puerarin dissolved in double-distilled water, 150 mg/kg/day) and the control group (equal volume of double-distilled water). After an 8-week intervention, changes in muscle mass and function between the two groups were compared. Techniques such as HE staining, immunofluorescence staining, ELISA, transmission electron microscopy, Western blot, and qRT-PCR were employed to evaluate the positive effects of puerarin on sarcopenia in naturally aged mice. Furthermore, serum proteomics and muscle transcriptomics were used to analyze the molecular mechanisms underlying the anti-muscle atrophy effects of puerarin. The results demonstrated that puerarin significantly improved body composition, enhanced muscle mass and function, and exerted its effects by modulating inflammatory cytokines, reducing oxidative stress, and inhibiting the expression of apoptosis proteins in skeletal muscle. Additionally, integrated proteomics and transcriptomics analyses suggested that the anti-muscle atrophy mechanisms of puerarin might be related to the TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway. These findings highlight puerarin's potential as a therapeutic agent for sarcopenia, providing a foundation for further research and clinical application.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10753-025-02274-9.

Keywords: Sarcopenia, Puerarin, Proteomics, Transcriptomics, Inflammation

Introduction

With the intensification of population aging, age-related chronic diseases have become pressing public health concerns, among which sarcopenia, or muscle-wasting syndrome, stands out. This condition, a progressive and systemic skeletal muscle disorder, is marked by an accelerated decline in skeletal muscle mass and functionality [1]. While not directly causing death, sarcopenia substantially degrades the elderly's quality of life. The inevitable loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, part of normal aging, escalates the likelihood of adverse outcomes, including falls, fractures, physical disability, and even death among older individuals [2]. Research indicates that the risk of falls is significantly elevated in sarcopenic patients compared to non-sarcopenic ones [3].

Currently, the clinical interventions available for treating sarcopenia are limited, primarily encompassing exercise, nutritional supplementation, and pharmacological treatments [4–6]. Exercise and dietary therapies, however, are not effective interventions for elderly sarcopenia patients, many of whom may be unwilling or unable to endure effective exercise regimens, particularly those with severe sarcopenia. Furthermore, gastrointestinal dysfunction, common among the elderly, can impair nutrient intake and energy provision. Although pharmacological treatment represents a beneficial approach for managing sarcopenia in the elderly, no drugs have yet received clinical approval for this purpose. Puerarin, a major active isoflavone derived from Pueraria lobata, displays several biological activities, including bone protection, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative properties [7]. Considering puerarin’s potential in osteoporosis and the intricate connection between the skeletal and muscular systems, investigating whether puerarin can ameliorate or treat sarcopenia merits further study. To date, research on puerarin’s efficacy in treating sarcopenia remains sparse.

Given the central role of aging as a risk factor for numerous musculoskeletal disorders, including osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and sarcopenia, the use of naturally aged mice model provides the closest replication of the aging process. Consequently, employing an aged mouse model is deemed most suitable for sarcopenia research [8]. Mice have an average lifespan of approximately 24 months, with those at 3 months of age analogous to 20-year-old humans, and those between 18 and 24 months comparable to humans aged 56 to 69 years [9]. Therefore, studies on natural aging predominantly utilize mice that are at least 18 months old. Furthermore, biomarkers associated with aging are primarily detected in mice aged at least 18 months [10]. Research indicates that, in comparison with 10-week-old C57BL/6 J mice, those aged 18 months display diminished grip strength, reduced endurance, and significantly decreased muscle volume and mass, all of which are indicative of sarcopenia [11]. In terms of gender selection, male mice are often preferred due to their longer lifespans and the reduction in data variability caused by hormonal cyclical changes [12]. In light of this context, 20-month-old male C57BL/6 J mice were chosen as the sarcopenia model for natural aging in this study to investigate the intervention effects of puerarin.

To deepen the understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which puerarin mitigates muscle atrophy in aged sarcopenic mice, an in-depth proteomic analysis was performed on the serum proteins of these aged mice, along with high-throughput transcriptome sequencing of skeletal muscle samples. The study employed Data Independent Acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry techniques for high-throughput, high-precision proteomic analysis of serum samples. Unlike Data Dependent Acquisition (DDA), DIA offers the significant advantage of comprehensively scanning all ions within the spectral range without pre-selecting specific precursor ions [13]. This approach facilitates the reconstruction and identification of proteins and their peptides from complex samples, thereby enriching the data available for further analysis [14]. The examination of changes in serum protein expression patterns, particularly those involved in inflammation, muscle metabolism, and cellular signaling, has elucidated potential targets and biological effects of puerarin. Additionally, transcriptomic analysis on skeletal muscle contributes to the observation of gene transcription level differences in the muscle tissues of aged sarcopenic mice following puerarin intervention, thus uncovering key signaling pathways critical to puerarin's therapeutic effects on sarcopenia.

Methods

Construction of the Naturally aged Sarcopenia Model and Puerarin INTERVENTION

To ensure experimental homogeneity, 12 littermate C57BL/6 J mice were raised until 20 months of age prior to intervention. These 20-month-old mice were designated as a model for naturally aged sarcopenia. After a week of acclimatization in an SPF-grade animal facility, the mice were randomly assigned to two experimental groups, each comprising six mice. The intervention protocols were as follows: (1) Puerarin intervention group: received daily gavage of 150 mg/kg puerarin solution for eight weeks; (2) Control group: received daily gavage of an equivalent volume of saline solution for the same duration. The concentration of puerarin was based on previous studies [15]. Puerarin was sourced from Abcam (abs47000513). All experimental procedures strictly adhered to the guidelines approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Life Sciences at Fudan University.

Assessment of Muscle Function

The muscle function of mice was evaluated using two methods: grip strength testing and the rotarod endurance test. In the grip strength test, mice were positioned on the force plate of a grip meter (Yiyan Company, Jinan, China) where the tail was gently pulled to induce the forelimbs to grasp a horizontal bar. The force was incrementally increased until the forelimbs released, and the force at this point was recorded. The procedure was repeated three times with a 10-min interval between each test to ensure adequate rest, and the highest value from the three measurements was recorded as the result. For the rotarod endurance test, the ability of the mice to maintain motor coordination, balance, and fatigue resistance was assessed using a rod that increased in speed from 4 to 40 revolutions per minute (Calvin Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). Prior to the formal test, mice underwent five preparatory trials, each lasting 2 min at 4 revolutions per minute with a 10-min rest between trials. The test concluded either when the mice fell or after a maximum duration of 5 min, with the endurance time recorded as an indirect measure of muscle function and stamina.

Analysis of Body Composition

Prior to body composition analysis, each mouse was fasted for four hours. Subsequently, body composition, including fat mass and lean mass, was measured using an EchoMRI body composition analyzer, following the standard operating procedure of the instrument. Mice were positioned within the instrument's stabilizing column to ensure immobility during the process. For accuracy, measurements were conducted three times and averaged to determine the body composition. During anatomical sampling, all mice were anesthetized. Approximately 1 mL of blood was collected into a heparinized EP tube. After resting at room temperature for two hours, the blood samples were subjected to high-speed centrifugation. The supernatant plasma was subsequently collected and stored at −80 °C for further ELISA and serum proteomics analyses. Major muscle tissues from the lower limbs, including the quadriceps (QUAD), gastrocnemius (GAS), anterior tibialis (TA), soleus (SOL), and extensor digitorum longus (EDL), were harvested using blunt dissection with toothless tweezers, and surface fat was meticulously removed. Muscle weights were recorded, with the average weight from corresponding bilateral sites representing the actual weight of each muscle. Post-sampling, muscle tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80 °C for future molecular biology experiments, or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for paraffin or frozen sectioning, preparing for subsequent histological staining.

H&E Staining

For the H&E staining of skeletal muscle tissues, paraffin-embedded sections were first stained with hematoxylin for 5 to 10 min to stain the nuclei. After staining, the sections were rinsed under running water to remove excess dye and then washed with deionized water. Eosin was applied to counterstain the cytoplasm, with the staining duration adjusted between 30 s and 3 min as needed. Following counterstaining, the sections were dehydrated through sequential immersion in 70%, 80%, 90% ethanol, and finally in absolute ethanol, each for 10 s. The sections were then cleared in xylene, twice, for 5 min each. Mounting was performed using neutral resin. The staining results were evaluated under a microscope, revealing blue-stained nuclei and cytoplasm ranging from pink to red. Additionally, photographs of areas with clear and complete tissue structures were taken for further analysis, and muscle fiber size was quantified using Image J software.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Initially, frozen sections were retrieved from a −20 °C freezer and allowed to reach room temperature before being immersed in PBST for 10 min. Subsequently, sections were placed into boiling antigen retrieval solution, with the duration of heating tailored between 30 to 60 min depending on the tissue antigens requiring retrieval. Following antigen retrieval, sections were washed three times with PBS to eliminate any residual solution. Tissue margins were delineated with a hydrophobic pen, and 5% goat serum was applied within these boundaries to block non-specific binding for one hour at room temperature. After blocking, sections were incubated with diluted primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Post-primary antibody incubation, sections were washed thrice with PBS to remove unbound antibodies and then treated with diluted secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Following secondary antibody incubation, a mounting medium was applied, finalizing the slide preparation.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Gastrocnemius muscle tissues were rapidly excised and cut into small fragments within 1 to 3 min. The fragments were stored at 4 °C in fresh fixative. The samples were washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h in the dark, and washed again. Dehydration was done with graded ethanol and acetone at room temperature. Tissues were infiltrated with a 1:1 and 1:2 mixture of acetone and Epon 812 at 37 °C, followed by pure resin. Polymerization occurred at 60 °C for 48 h. Thin Sects. (60–80 nm) were cut, mounted on copper grids, stained with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and air-dried overnight. The sections were examined under a transmission electron microscope.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

In this study, serum inflammatory and oxidative stress markers were quantified in aged mice using ELISA. Mouse Inflammatory Cytokine ELISA Kits (ELK Biotechnology) were utilized to measure plasma levels of six cytokines: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-15, TNF-α, and GDF15. The kits demonstrated sensitivities ranging from 3.0 to 6.4 pg/mL and detection limits of 7.82 to 1000 pg/mL. Additionally, levels of GSH and MDA were assessed using ELISA kits from Shanghai Hengyuan Biotech, with GSH showing a sensitivity of 1.25 ng/L and MDA 0.075 nmol/L. All procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the manufacturers' protocols.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from muscle tissues using the Trizol method, involving tissue lysis in Trizol reagent, phase separation with chloroform, precipitation with isopropanol, and washing with ethanol. The purified RNA was dissolved in RNase-free water. RNA concentration and purity were assessed via spectrophotometric measurements at 260 nm and 280 nm. Following quantification, RNA samples were reverse transcribed into cDNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) was then performed using gene-specific primers (listed in Table S1) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. Gene expression levels were normalized to an internal reference gene and analyzed using the comparative CT method to ensure accurate quantification of gene expression profiles.

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins were extracted from muscle tissues by homogenization in a lysis buffer enriched with protease inhibitors, followed by centrifugation to collect the supernatant. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay. For analysis, proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and blocked to minimize non-specific binding. Membranes were probed with specific primary and secondary antibodies, and target proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence. Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software, with antibody details provided in Table S2.

Quantitative Proteomics Analysis

Plasma samples were initially treated with magnetic beads to enrich proteins, capturing low-abundance proteins through a series of washing and incubation steps. Enzymatic digestion of the proteins was performed on-bead, and the resulting peptides were desalted using centrifugation steps with methanol and buffers. The desalted peptides were analyzed via nanoLC-MS/MS using an Evosep One system coupled to a timsTOF Pro2 mass spectrometer with a nano-electrospray ion source and a PePSep C18 column. Chromatographic separation was achieved with a gradient of acetonitrile, water, and formic acid. Data processing and analysis were conducted with Spectronaut software, utilizing the Pulsar search engine for database searching, qualitative analysis, and spectral library construction for peptide and protein quantification. Advanced bioinformatics procedures were applied to the DIA proteomics data. These included differential expression protein screening to identify changes in protein levels, COG annotation for functional categorization, subcellular localization analysis, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses for identifying enriched biological pathways, and the construction of a Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) network to explore protein interactions.

RNA Sequencing

In this study, RNA was extracted from gastrocnemius muscle tissues of aged mice. The quality and integrity of the RNA were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis, a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. After verifying the sample quality, mRNA was isolated by exploiting the polyA tail feature using oligo(dT) magnetic beads. The isolated mRNA was then fragmented and reverse-transcribed to synthesize double-stranded cDNA. Subsequently, the double-stranded cDNA underwent end repair and adapter ligation, followed by magnetic bead purification and size selection to ensure library quality. The resulting libraries were subjected to quality control and then sequenced on the Illumina platform, generating a large number of short reads. Bioinformatic analysis was conducted to quantitatively assess gene expression in the gastrocnemius muscle transcriptomes of the two groups, identifying differentially expressed genes following puerarin intervention. These genes were further analyzed for GO and KEGG enrichment.

Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were obtained from at least three biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.4 software. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD). For the complex analysis of high-throughput proteomics and transcriptomics data, R software (version 4.1.3) was utilized to ensure the scientific rigor and accuracy of the study findings.

Results

Puerarin Delays Muscle Mass Loss in Aged Sarcopenic Mice

The primary lower limb muscle groups were excised and weighed from two groups of aged mice. As shown in Fig. 1A, the muscle mass of aged mice treated with puerarin was noticeably higher compared to untreated aged mice. Quantitative analysis of muscle mass (Fig. 1B-F) revealed that aged mice receiving puerarin intervention had significantly greater mass in key lower limb muscles, except for SOL, compared to untreated mice (p < 0.05). This effect was particularly pronounced in the TA and EDL, indicating that puerarin treatment might delay muscle mass loss in aged mice. Baseline body weights of the two groups did not show significant differences, ensuring consistent initial conditions. After the 8-week intervention, the body weight gain of puerarin-treated aged mice was significantly higher than that of untreated mice (Fig. 1G, p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Puerarin prevents muscle mass loss in aged sarcopenic mice. A Comparative images of muscle specimens from two groups of aged mice. B Comparison of TA muscle mass between the two groups C Comparison of EDL muscle mass between the two groups. D Comparison of GAS muscle mass between the two groups. E Comparison of SOL muscle mass between the two groups. F Comparison of QUAD muscle mass between the two groups. G Body weight changes (% of initial body weight) between the two groups. BW stands for body weight. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Muscle Function Evaluation and Body Composition Analysis

Muscle function parameters of two groups of aged mice were assessed using a grip strength meter and a rotarod fatigue tester. As shown in Fig. 2A, aged mice treated with puerarin demonstrated significantly improved muscle strength in the grip strength test, with an average grip strength of 120.01 g, compared to 89.93 g in untreated aged sarcopenic mice (p < 0.01). Additionally, in the rotarod fatigue test (Fig. 2B), puerarin-treated aged mice maintained an average time of 189.2 s on the rotarod, significantly longer than the 140.1 s observed in untreated aged mice (p < 0.05), indicating enhanced muscle endurance due to puerarin intervention. Body composition analysis revealed that the lean body mass of untreated aged sarcopenic mice was significantly lower than that of puerarin-treated aged mice (Fig. 2C, p < 0.05). Concurrently, the fat mass in the puerarin-treated group showed a significant decreasing trend compared to the untreated group (Fig. 2D, p < 0.05). Previous study has established a correlation between abnormal fat deposition and muscle dysfunction [16]. As age increases, ectopic fat deposition in skeletal muscles becomes more prevalent, potentially contributing to muscle atrophy and functional decline [17].

Fig. 2.

Puerarin mitigates the loss of muscle function and decline in lean body mass in aged sarcopenic mice. A Comparison of grip strength between the two groups of aged mice. B Comparison of the duration on the rotarod between the two groups of aged mice. C Comparison of lean body mass between the two groups of aged mice. D Comparison of fat body mass between the two groups of aged mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Puerarin Inhibits Muscle Fiber Area Reduction and Expression of Muscle Atrophy Markers in Aged Sarcopenic Mice

As shown in Fig. 3A, the cross-sectional area of TA muscle fibers in aged mice treated with puerarin was significantly larger than that in untreated aged mice. Quantitative analysis of HE-stained muscle fibers (Fig. 3B) revealed that the number of smaller muscle fibers decreased while the number of larger muscle fibers increased in puerarin-treated aged mice compared to untreated controls. Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1, two E3 ubiquitin ligases, are widely recognized as key molecular markers in the process of skeletal muscle atrophy [18]. To further determine whether puerarin ameliorates muscle atrophy in aged sarcopenic mice, the expression of muscle atrophy markers in muscle tissues from both groups was examined. As depicted in Fig. 3D-F, the protein levels of Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 were significantly lower in the puerarin-treated aged mice compared to the untreated group. Additionally, the qRT-PCR analysis of TA muscle tissues from both groups showed that the mRNA levels of Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 were also significantly reduced in the puerarin-treated group (Fig. 3G-H). These results suggest that puerarin inhibits muscle atrophy by regulating the expression of atrophy-related factors at both the transcriptional and protein levels.

Fig. 3.

Puerarin inhibits the reduction of muscle fiber area and expression of muscle atrophy markers in aged sarcopenic mice. A Representative pictures of H&E staining of TA muscle in two groups of aged mice. B Distribution diagram of muscle fiber area in the TA between the two groups of aged mice. C Comparison of the average muscle fiber area in the TA between the two groups of aged mice. D Expression levels of atrophy marker proteins in the TA of two groups at the protein level. E Statistical diagram of grayscale values differences for Atrogin-1 protein between the two groups. F Statistical diagram of grayscale values differences for MuRF-1 protein between the two groups. G Relative mRNA expression levels of Atrogin-1 in the TA between the two groups. H Relative mRNA expression levels of MuRF-1 in the TA between the two groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Puerarin Promotes the Transition from Slow to Fast Muscle Fibers in Aged Sarcopenic Mice

To investigate the effect of puerarin on the transition of skeletal muscle fiber types in naturally aged sarcopenia model, the proportion of fast and slow muscle fibers in the GAS muscle of aged mice was analyzed using immunofluorescence staining. The results (Fig. 4A-C) showed a significant increase in the proportion of fast muscle fibers and a relative decrease in slow muscle fibers in the skeletal muscle of aged mice treated with puerarin. This suggests that puerarin promotes the transition from slow to fast muscle fibers in aged mice. Additionally, RNA was extracted from the GAS muscle for qRT-PCR analysis to evaluate changes in the mRNA expression levels of four myosin heavy chain genes. The results (Fig. 4D-E) indicated that the expression levels of Myh1, Myh2, Myh4, and Myh7 were significantly higher in the puerarin-treated group compared to the untreated group, with Myh1 and Myh2 showing particularly notable increases (p < 0.01). These findings demonstrate that puerarin significantly promotes the generation of type II muscle fibers.

Fig. 4.

Puerarin promotes the transition from slow to fast muscle fibers in aged sarcopenic mice. A Immunofluorescence staining results for the GAS muscle between the two groups. B Proportion of Type I fibers in the GAS muscle between the two groups. C Proportion of Type II fibers in the GAS muscle between the two groups. D Comparison of mRNA expression levels of fast-twitch fiber genes Myh1, Myh2, and Myh4 in the GAS muscle between the two groups. E Comparison of mRNA expression levels of the slow-twitch fiber gene Myh7 in the GAS muscle between the two groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Puerarin Improves Muscle Fiber Ultrastructure and Inhibits Apoptotic Protein Expression in Aged Sarcopenic Mice

TEM images of the GAS muscle (Fig. 5A) revealed that in the naturally aged sarcopenia model, muscle fibers exhibited irregular sarcomere patterns, the presence of apoptotic bodies, disrupted mitochondrial morphology, reduced mitochondrial numbers, and lipid droplet accumulation—hallmarks of muscle aging and atrophy. In contrast, muscle fibers from puerarin-treated aged mice showed more regular sarcomere patterns, more intact mitochondrial structures, and fewer lipid droplets, suggesting that puerarin may mitigate age-related muscle fiber aging and apoptosis. To evaluate the anti-apoptotic effects of puerarin, we analyzed the expression of apoptotic proteins in muscle tissue. As shown in Fig. 5B-C, phosphorylated P53 protein levels were significantly lower in the muscle of puerarin-treated aged mice compared to untreated aged mice. P53 is a crucial regulator of apoptosis, activated in response to DNA damage or other stress signals [19]. Upon activation, P53 is phosphorylated and regulates various downstream molecules, including Bax and Bcl-2, which are key regulatory factors in apoptosis [20]. We also found that the expression of Bax protein was significantly reduced in the muscle tissues of puerarin-treated aged mice, while Bcl-2 protein expression slightly increased, leading to a significantly lower Bax/Bcl-2 ratio (Fig. 5D-F). These results indicate that puerarin exerts a protective effect against muscle fiber apoptosis by modulating the expression of apoptosis-related proteins.

Fig. 5.

Puerarin reduces skeletal muscle cell apoptosis in aged sarcopenic mice. A The TEM pictures show that puerarin effectively reduces the destruction of muscle microstructure in aged sarcopenic mice. Black arrows indicate apoptotic bodies. B Expression levels of apoptotic proteins at the protein level in the GAS muscle between the two groups. C Statistical diagram of relative grayscale value differences for phosphorylated P53 protein between the two groups. D Statistical diagram of grayscale value differences for Bax protein between the two groups. E Statistical diagram of grayscale value differences for Bcl-2 protein between the two groups. F Differences in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio between the two groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001

Puerarin Modulates Serum Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers in Aged Sarcopenic Mice

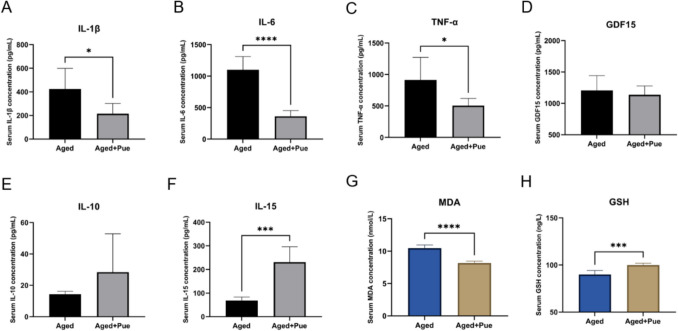

To evaluate the potential impact of puerarin on the chronic inflammatory state in the naturally aged sarcopenia model, the levels of six serum inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-15, and GDF15) were measured in two groups of aged mice. As shown in Fig. 6A-F, the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly reduced in puerarin-treated aged mice, indicating a notable anti-inflammatory effect of puerarin. Concurrently, the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-15 exhibited higher levels in the puerarin-treated group, with IL-15 showing a statistically significant increase. Aging is often associated with a decline in antioxidant capacity, and the accumulation of oxidative stress damage is a key factor in muscle function deterioration [21]. To assess the potential regulatory effects of puerarin on oxidative stress in aged sarcopenic mice, serum levels of GSH and MDA were compared between the two groups. As depicted in Fig. 6G-H, puerarin-treated aged mice showed a significant reduction in serum MDA levels and a significant increase in GSH levels, suggesting that puerarin may mitigate oxidative stress-induced damage.

Fig. 6.

Puerarin modulates the expression of inflammatory and antioxidant factors in aged sarcopenic mice. A Comparison of serum IL-1β levels between the two groups of mice. B Comparison of serum IL-6 levels between the two groups of mice. C Comparison of serum TNF-α levels between the two groups of mice. D Comparison of serum GDF15 levels between the two groups of mice. E Comparison of serum IL-10 levels between the two groups of mice. F Comparison of serum IL-15 levels between the two groups of mice. G Comparison of serum MDA levels between the two groups of mice. H Comparison of serum GSH levels between the two groups of mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Quantitative Proteomics Analysis

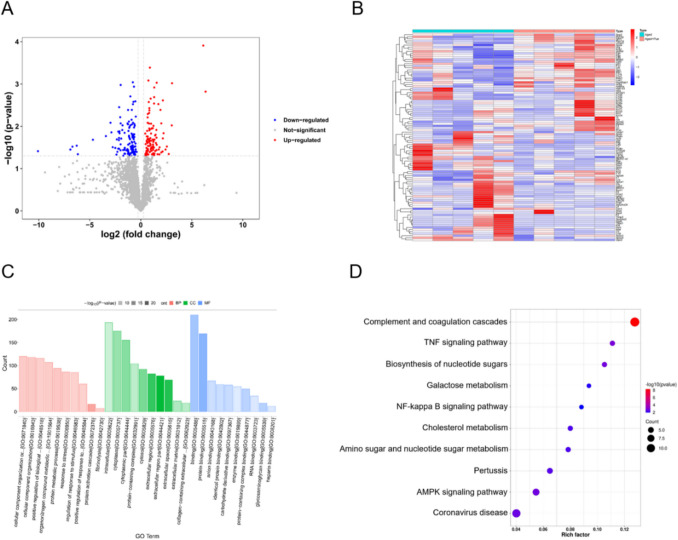

In this study, high-depth quantitative analysis of the serum samples from two groups of aged mice was conducted, identifying 2,966 proteins using the DIA mode. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were selected based on a p-value less than 0.05 and an absolute Log2FC greater than 0.5. A total of 250 DEPs were identified, including 111 upregulated and 139 downregulated proteins. The volcano plot and heatmap (Fig. 7A-B) visually illustrate these changes in protein expression. Subcellular localization analysis (Fig. S1A) revealed that the majority of DEPs were distributed in the secretory pathway (84 proteins, 33.6%), followed by the cytoplasm (78 proteins, 31.2%) and the nucleus (54 proteins, 21.6%). Besides, these DEPs were assigned to 26 different COG categories (Fig. S1B), with the most abundant categories being signal transduction mechanisms (category T), post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones (category O), and cytoskeleton-related proteins (category Z).

Fig. 7.

Comprehensive analysis of differentially expressed proteins in aged sarcopenic mice treated with puerarin. A Volcano plot of differentially expressed proteins. B Heatmap of protein expression changes. C GO functional enrichment analysis. D KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

To further understand the enrichment of these DEPs in terms of biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF), GO functional enrichment analysis was performed (Fig. 7C). In the BP category, these proteins were enriched in structural composition, biological regulation, metabolic processes, and responses to external stimuli. In the CC category, these proteins were predominantly located in the cytoplasm, nucleus, and cell membrane, consistent with the subcellular localization results. In the MF category, these proteins were mainly enriched in ion binding, enzymatic activity, and protein complex binding. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (Fig. 7D) indicated that several inflammation-related pathways were downregulated in the puerarin-treated group, including the TNF signaling pathway and NF-κB signaling pathway, which are critical for immune and inflammatory responses. On the other hand, pathways involved in complement and coagulation cascades were significantly upregulated, reflecting the complex modulation of inflammation-related processes by puerarin. Additionally, the PPI network (Figure S1C) detailed the interactions among these DEPs, with protein connectivity analysis (Fig. S1D) showing that Fga, Fgg, and C3 had the highest number of interactions with other proteins.

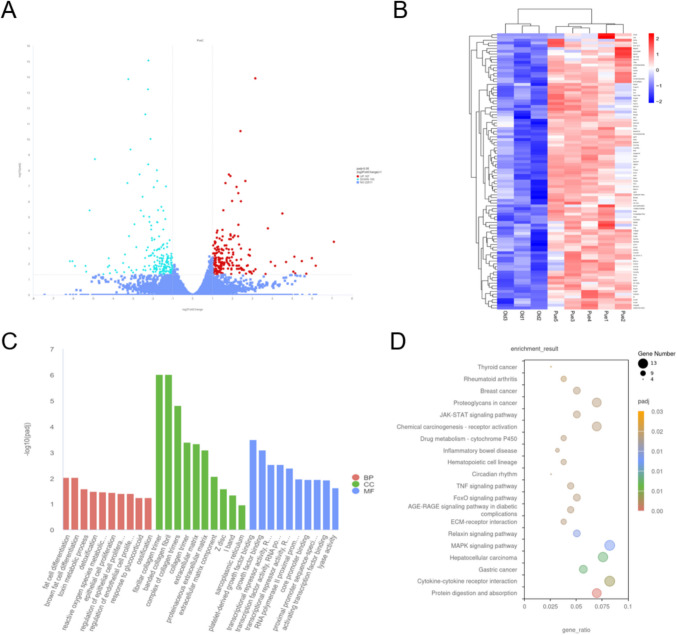

RNA Sequencing Analysis of Gastrocnemius Muscle

To elucidate the specific effects of puerarin on muscle gene expression in aged sarcopenic mice, high-throughput transcriptome sequencing was performed on gastrocnemius muscle samples from two groups of aged mice. Genes were classified as differentially expressed if their absolute Log2FC value exceeded 1 and the adjusted p-value was below 0.05. Consequently, 380 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified, including 187 upregulated and 193 downregulated genes. The expression changes of these genes following puerarin treatment were visualized using volcano plots and heatmaps (Fig. 8A-B). GO enrichment analysis (Fig. 8C) showed that in the BP category, DEGs were primarily related to brown fat cell differentiation, oxidation–reduction process, glycogen synthesis and degradation, and cellular response to stress. In the CC category, DEGs were significantly associated with various cellular structures, particularly mitochondria and protein complexes. In the MF category, DEGs were mainly enriched in functions related to ATP binding, protein binding, and oxidoreductase activity. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (Fig. 8D) indicated that puerarin treatment significantly affected multiple key biological pathways in aged sarcopenic mice, including the TNF signaling pathway, FoxO signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, protein digestion and absorption, and inflammatory bowel disease pathway.

Fig. 8.

Transcriptomic analysis of the effects of puerarin treatment on gas muscle in aged sarcopenic mice. A Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in GAS muscle. B Heatmap of gene expression in GAS muscle post-Puerarin treatment. C GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. D KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes

Puerarin Mitigates Muscle Atrophy in Aged Sarcopenic Mice by Inhibiting the TNF-α/NF-κB Pathway

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of serum proteomics and muscle transcriptomics indicated that inflammation-related pathways might be the key mechanisms through which puerarin exerts its effects. The TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway plays a critical role in immune and inflammatory responses. Therefore, the expression of key proteins in the TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway was examined in the muscle tissues of both groups of aged mice. As shown in Fig. 9, puerarin treatment resulted in reduced expression levels of TNF-α in the muscle tissues of aged mice. Additionally, the phosphorylation levels of Ikkα, Ikkβ, P65, and IκBα were significantly decreased, indicating that puerarin effectively inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in the naturally aged sarcopenia model.

Fig. 9.

Puerarin reduces muscle atrophy in aged sarcopenic mice by inhibiting the TNF-α/NF-kB Pathway. A Expression levels of proteins in the TNF-α/NF-kB signaling pathway in the QUAD muscle between the two groups of mice at the protein level. B Statistical diagram of grayscale value differences for TNF-α protein in the muscles between the two groups. C Statistical diagram of relative grayscale value differences for phosphorylated Ikkα protein between the two groups. D Statistical diagram of relative grayscale value differences for phosphorylated Ikkβ protein between the two groups. E Statistical diagram of relative grayscale value differences for phosphorylated P65 protein between the two groups. F Statistical diagram of relative grayscale value differences for phosphorylated IκBα protein between the two groups. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Figure S2 shows that several key NF-κB regulated genes, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, were significantly downregulated in the puerarin-treated group compared to the control group. These inflammatory markers, which play a critical role in the pathogenesis of muscle atrophy, exhibited statistically significant reductions, suggesting that puerarin effectively modulates the NF-κB-driven inflammatory response in muscle. Furthermore, the gene encoding IκBα, NFKBIA, was significantly downregulated in the puerarin-treated group, which aligns with the suppression of NF-κB activation, as IκBα acts as a negative regulator of this pathway.

Discussion

Sarcopenia, a chronic degenerative condition that progresses with aging, is characterized by significant reductions in protein content, organelle number, cytoplasmic volume, muscle fiber diameter, as well as muscle strength and endurance [22]. As a major contributor to falls, disabilities, and decreased quality of life in the elderly, sarcopenia poses substantial challenges to individual health and the overall healthcare system. In the context of global population aging, developing effective prevention and treatment strategies has become an urgent focus in public health research.

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are considered key drivers in the onset and progression of sarcopenia, with their effects intensifying with age [23]. Puerarin, a natural compound extracted from Pueraria lobata, has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [24, 25]. However, the effects of puerarin on naturally aged sarcopenia model and its underlying molecular mechanisms have not been previously reported. This study aims to investigate the therapeutic potential and underlying molecular mechanisms of puerarin in treating age-related sarcopenia. By comprehensively assessing its impact on body composition, muscle mass and function, tissue morphology, serum proteomics, and muscle transcriptomics in the naturally aged sarcopenia model, we seek to provide a deeper understanding of puerarin's efficacy in combating sarcopenia.

Body composition analysis revealed that puerarin intervention increased lean body mass and reduced fat mass in aged sarcopenic mice. The accumulation of adipose tissue is closely associated with the development of sarcopenia, particularly intramuscular fat, which negatively affects muscle mass and function [26]. Although we did not directly assess intramuscular lipid accumulation using advanced imaging techniques, previous studies suggest that puerarin may influence lipid metabolism and energy expenditure [27]. Future studies should employ lipid-specific imaging techniques to further explore puerarin’s role in regulating muscle fat composition.

The results of this research indicate that long-term puerarin intervention significantly enhances muscle mass in aged sarcopenic mice, particularly in the TA and EDL. This improvement is reflected not only in increased muscle mass but also in enhanced muscle function. Compared to untreated aged sarcopenic mice, those treated with puerarin exhibited greater grip strength and longer retention time on the rotarod, suggesting that puerarin helps to improve muscle strength and endurance. These improvements may stem from puerarin's positive effects on metabolic and energy-generating processes within muscle cells [28], indicating that puerarin combats age-related muscle functional decline by promoting efficient energy utilization and enhancing metabolic activity.

We also observed that puerarin intervention significantly improved the morphological characteristics of muscle tissue in aged mice, particularly by increasing muscle fiber cross-sectional area and the number of large muscle fibers. These morphological changes are important indicators of increased muscle mass and enhanced function, reflecting improved muscle remodeling and regeneration capacity. Age-related muscle atrophy is typically accompanied by a reduction in muscle fiber cross-sectional area and a shift in fiber type, leading to declines in muscle strength and endurance [29]. The increase in muscle fiber cross-sectional area may be associated with puerarin-activated muscle regeneration and repair mechanisms, including the promotion of satellite cell activation and differentiation, which are crucial for muscle fiber reconstruction and repair in aging muscles [30]. Additionally, TEM observations showed that puerarin effectively reduced the ultrastructural damage of muscle fibers in aged sarcopenic mice, further indicating puerarin's ability to improve muscle structural integrity at the cellular level.

Muscle fiber type conversion plays a crucial role in adapting to various physical activities or pathological conditions [31]. Fast-twitch fibers are suited for rapid and powerful contractions, while slow-twitch fibers are essential for endurance and prolonged activities [32]. Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence staining suggests that puerarin intervention promotes the conversion of slow-twitch to fast-twitch fibers in aged sarcopenic mice. Additionally, the expression of the myosin heavy chain genes Myh1, Myh2, Myh4, and Myh7 was significantly higher in the puerarin-treated group compared to the untreated group, with Myh1 and Myh2 showing particularly notable increases. Myh1 and Myh2 encode myosin heavy chains primarily found in fast-contracting, fatigue-prone Type IIx and Type IIa muscle fibers [33], further confirming that puerarin promotes the proliferation of fast-twitch fibers. Interestingly, the expression of Myh7, a gene encoding slow-twitch fibers, also increased in the puerarin-treated group. This finding suggests that the effects of puerarin on muscle fiber type conversion may be more complex than initially anticipated. It is hypothesized that puerarin intervention increases the expression of both fast and slow-twitch fiber genes, but the increase in fast-twitch fibers is more pronounced, leading to an observed increase in the proportion of fast-twitch fibers through immunofluorescence staining. This seemingly paradoxical result may reflect the diverse nature of muscle adaptive remodeling, indicating that puerarin may optimize muscle composition through multiple pathways to address the challenges of aging.

Inflammatory cytokines play a complex role in the development of sarcopenia, exhibiting pleiotropic and dose-dependent effects that depend on the duration and concentration of their secretion [34]. Elevated levels of IL-6 and TNF-α have been associated with reduced grip strength, decreased limb muscle mass, and lower knee extension strength in the elderly [35, 36]. Additionally, active IL-1β, secreted following inflammasome-dependent caspase-1 activation, is implicated in the process of inflammatory aging and the development of sarcopenia [37]. Conversely, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-15 has been shown to positively regulate myotube hypertrophy and mitigate the deleterious inflammatory effects induced by TNF-α, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target for sarcopenia [38]. A clinical cross-sectional study also highlighted a significant association between reduced serum IL-15 levels and the incidence of sarcopenia in the elderly [39]. In this study, puerarin treatment significantly reduced serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in aged sarcopenic mice, while markedly increasing levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-15. These results suggest that puerarin has the potential to inhibit the progression of sarcopenia by modulating the expression of inflammatory cytokines. Moreover, IL-15 is known to promote the breakdown of adipose tissue and effectively reduce obesity, thereby contributing to the regulation of body composition [40]. Therefore, it is plausible that puerarin improves body composition by significantly increasing serum IL-15 levels, reducing fat mass, and increasing lean mass in aged mice.

Proteomics and transcriptomics analyses provide deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms by which puerarin delays muscle atrophy in aged sarcopenic mice. These high-throughput technologies allow us to comprehensively analyze the effects of puerarin on sarcopenia at the molecular level, including the regulation of protein expression and gene expression changes. In serum proteomics analysis, 250 DEPs were identified, with 111 upregulated and 139 downregulated. These DEPs are involved in various biological processes and pathways, reflecting the broad impact of puerarin on muscle tissue metabolism, inflammatory responses, and cellular stress responses. Muscle transcriptomics analysis revealed 380 DEGs, including 187 upregulated and 193 downregulated genes. These gene expression changes suggest that puerarin may delay muscle atrophy by affecting energy metabolism, cellular stress responses, and the function of cellular structures such as mitochondria. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated that these differentially expressed proteins and genes are mainly enriched in complement and coagulation cascades, TNF signaling pathway, protein digestion and absorption, FoxO signaling pathway, and NF-kappa B signaling pathway. The regulation of these pathways suggests that puerarin may exert its therapeutic effects by influencing these pathways, with the inhibition of the TNF-α/NF-κB pathway being a key mechanism in reducing muscle atrophy. Notably, while KEGG enrichment analysis of serum proteomics showed significant impacts on both the TNF signaling pathway and NF-kappa B signaling pathway by puerarin intervention, transcriptomics analysis only observed gene enrichment in the TNF signaling pathway and not in the NF-kappa B signaling pathway. This discrepancy may be due to the activation mechanism of the NF-kappa B pathway, which is primarily regulated through the phosphorylation of key proteins rather than direct changes in gene expression levels. Therefore, while the NF-kappa B signaling pathway is regulated at the protein level, these phosphorylation changes are not reflected in the transcriptomics data, leading to the lack of significant enrichment of the NF-kappa B signaling pathway in the transcriptomics analysis.

Although this study successfully demonstrated the efficacy of puerarin in ameliorating muscle atrophy in an aged sarcopenic mouse model, several limitations remain. First, while the naturally aging sarcopenic mouse model is an effective tool for simulating human sarcopenia, it cannot fully replicate the complex physiological and pathological conditions of humans. Therefore, the actual effectiveness and safety of puerarin in treating human sarcopenia need to be validated through clinical trials. Additionally, the potential effects of puerarin on muscle satellite cells were not explored in this study, and this represents an important avenue for future research. Moreover, while this study aimed to examine potential changes in muscle lipid metabolism, more advanced techniques such as Bodipy or Perilipin immunofluorescence staining should be employed in future investigations to obtain more definitive evidence regarding lipid deposition and distribution within skeletal muscle tissue. Finally, although we evaluated oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in serum, the lack of direct measurement in skeletal muscle tissue represents a limitation of the current study, which we plan to address in future research.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively evaluated the therapeutic effects of puerarin on a naturally aged sarcopenia model using serum proteomics, muscle transcriptomics, and molecular biology techniques (Fig. 10). The results demonstrated that puerarin significantly improved body composition, enhanced muscle mass and function, and exerted its effects by modulating inflammatory cytokines, reducing oxidative stress, and inhibiting the expression of apoptosis proteins in muscle. Notably, puerarin may slow the progression of muscle atrophy by inhibiting the TNF-α/NF-κB signaling pathway. These findings not only further establish the potential of puerarin as a therapeutic agent for sarcopenia in the elderly but also provide a solid scientific foundation for deeper investigation into its mechanisms of action and the development of future therapeutic strategies.

Fig. 10.

A Proposed Molecular Mechanism of Puerarin in Ameliorating Muscle Atrophy in Aged Sarcopenic Mice

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

Yongqian Fan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Conceptualization, Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Software, Funding acquisition. Shengwu Yang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. Fengjian Yang: Methodology, Validation, Software, Data curation, Investigation. Tao Cui: Visualization, Validation, Resources, Formal analysis. Shangjin Lin: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources. Ying Cheng: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Software, Investigation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Fractures of Huadong Hospital (No. LCZX2208).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental protocols carried out in this study were conducted in full compliance with the guidelines and were authorized by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Life Sciences at Fudan University.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Shangjin Lin, Ying Cheng and Tao Cui are co-first authors of this article.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shengwu Yang, Email: yangshengwu@wmu.edu.cn.

Yongqian Fan, Email: from2018@sina.com.

References

- 1.Dao, T., A.E. Green, Y.A. Kim, et al. 2020. Sarcopenia and muscle aging: a brief overview. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 35 (4): 716–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argiles, J.M., S. Busquets, B. Stemmler, et al. 2015. Cachexia and sarcopenia: mechanisms and potential targets for intervention. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 22:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung, S., E.M. Reijnierse, V.K. Pham, et al. 2019. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 10 (3): 485–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erlich, A.T., L.D. Tryon, M.J. Crilly, et al. 2016. Function of specialized regulatory proteins and signaling pathways in exercise-induced muscle mitochondrial biogenesis. Integr Med Res 5 (3): 187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips, S.M., and W. Martinson. 2019. Nutrient-rich, high-quality, protein-containing dairy foods in combination with exercise in aging persons to mitigate sarcopenia. Nutrition Reviews 77 (4): 216–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remelli, F., A. Vitali, A. Zurlo, et al. 2019. Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia in Older Persons. Nutrients 11 (12): 2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, S., S. Zhang, S. Wang, et al. 2020. A comprehensive review on Pueraria: Insights on its chemistry and medicinal value. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 131:110734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hambright, W.S., L.J. Niedernhofer, J. Huard, et al. 2019. Murine models of accelerated aging and musculoskeletal disease. Bone 125:122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng, F., F. Xie, and O. Muzik. 2018. Alteration of copper fluxes in brain aging: a longitudinal study in rodent using (64) CuCl(2)-PET/CT. Aging & Disease 9 (1): 109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutta, S., and P. Sengupta. 2016. Men and mice: relating their ages. Life Sciences 152:244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, C., and J.K. Hwang. 2020. The 5,7-Dimethoxyflavone Suppresses Sarcopenia by Regulating Protein Turnover and Mitochondria Biogenesis-Related Pathways. Nutrients 12 (4): 1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumann, C.W., D. Kwak, and L.V. Thompson. 2019. Sex-specific components of frailty in C57BL/6 mice. Aging (Albany NY) 11 (14): 5206–5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitata, R.B., J.C. Yang, and Y.J. Chen. 2023. Advances in data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry towards comprehensive digital proteome landscape. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 42 (6): 2324–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang, Y., L. Lin, and L. Qiao. 2021. Deep learning approaches for data-independent acquisition proteomics. Expert Review of Proteomics 18 (12): 1031–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, W., B. Gao, L. Qin, and X. Wang. 2022. Puerarin improves skeletal muscle strength by regulating gut microbiota in young adult rats. J Orthop Translat. 21 (35): 87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mengeste, A.M., A.C. Rustan, and J. Lund. 2021. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 29 (10): 1582–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buch, A., E. Carmeli, L.K. Boker, et al. 2016. Muscle function and fat content in relation to sarcopenia, obesity and frailty of old age–An overview. Experimental Gerontology 76:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumucio, J.P., and C.L. Mendias. 2013. Atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and sarcopenia. Endocrine 43 (1): 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, H., M. Guo, H. Wei, et al. 2023. Targeting p53 pathways: Mechanisms, structures, and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 8 (1): 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zavileyskiy, L., and V. Bunik. 2022. Regulation of p53 function by formation of non-nuclear heterologous protein complexes. Biomolecules 12 (2): 327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belenguer-Varea, A., F.J. Tarazona-Santabalbina, J.A. Avellana-Zaragoza, et al. 2020. Oxidative stress and exceptional human longevity: systematic review. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 149: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandri, M. 2008. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology (Bethesda, Md.) 23:160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, L., M. Li, C. Deng, et al. 2022. Potential therapeutic strategies for skeletal muscle atrophy. Antioxidants (Basel) 12 (1): 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, L., L. Liu, and M. Wang. 2021. Effects of puerarin on chronic inflammation: focus on the heart, brain, and arteries. Aging Med (Milton) 4 (4): 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, X., R. Huang, and J. Wan. 2023. Puerarin: a potential natural neuroprotective agent for neurological disorders. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 162:114581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, C.W., K. Yu, N. Shyh-Chang, et al. 2022. Pathogenesis of sarcopenia and the relationship with fat mass: descriptive review. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 13 (2): 781–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung, H.W., A.N. Kang, S.Y. Kang, et al. 2017. The root extract of Pueraria lobata and its main compound, puerarin, prevent obesity by increasing the energy metabolism in skeletal muscle. Nutrients 9 (1): 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen, X.F., L. Wang, Y.Z. Wu, et al. 2018. Effect of puerarin in promoting fatty acid oxidation by increasing mitochondrial oxidative capacity and biogenesis in skeletal muscle in diabetic rats. Nutrition & Diabetes 8 (1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naruse, M., S. Trappe, and T.A. Trappe. 2023. Human skeletal muscle-specific atrophy with aging: a comprehensive review. J Appl Physiol (1985) 134 (4): 900–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White, T.P., and K.A. Esser. 1989. Satellite cell and growth factor involvement in skeletal muscle growth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 21 (5 Suppl): S158–S163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereyra, A.S., C.T. Lin, D.M. Sanchez, et al. 2022. Skeletal muscle undergoes fiber type metabolic switch without myosin heavy chain switch in response to defective fatty acid oxidation. Mol Metab 59:101456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latchman, H. K., S.G. Wette, D.J. Ellul, et al. 2023. Fiber type identification of human skeletal muscle. Journal of Visualized Experiments 199:e63456. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Wang, C., F. Yue, and S. Kuang. 2017. Muscle histology characterization using H&E staining and muscle fiber type classification using immunofluorescence staining. Bio Protoc 7 (10): e2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antuna, E., C. Cachan-Vega, J.C. Bermejo-Millo, et al. 2022. Inflammaging: implications in sarcopenia. Int J Mol Sci 23 (23): 15039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaap, L.A., S.M. Pluijm, D.J. Deeg, et al. 2006. Inflammatory markers and loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength. American Journal of Medicine 119 (6): 526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuttle, C., L. Thang, and A.B. Maier. 2020. Markers of inflammation and their association with muscle strength and mass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 64:101185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dinarello, C.A. 2006. Interleukin 1 and interleukin 18 as mediators of inflammation and the aging process. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 83 (2): 447S-455S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Leary, M.F., G.R. Wallace, A.J. Bennett, et al. 2017. IL-15 promotes human myogenesis and mitigates the detrimental effects of TNF-alpha on myotube development. Science and Reports 7 (1): 12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yalcin, A., K. Silay, A.R. Balik, et al. 2018. The relationship between plasma interleukin-15 levels and sarcopenia in outpatient older people. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 30 (7): 783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalinkovich, A., and G. Livshits. 2017. Sarcopenic obesity or obese sarcopenia: a cross talk between age-associated adipose tissue and skeletal muscle inflammation as a main mechanism of the pathogenesis. Ageing Research Reviews 35:200–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.