Abstract

Background

Generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) is an autoimmune disease characterized by fluctuating muscle weakness. The MG Impairment Index (MGII) incorporates patients’ perspectives (22 items) and physician evaluation (6 items) of impairment. We evaluated the effect of rozanolixizumab using the MGII in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 MycarinG study.

Methods

Adult patients with gMG were randomized 1:1:1 to once-weekly rozanolixizumab 7 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg or placebo for 6 weeks. MGII assessment was optional. Exploratory MGII analyses included change from baseline (CFB) to Day 43 in total score and ocular/generalized subscores; higher scores reflect greater impairment. Post hoc analyses included responder rates (≥ 5.5-point improvement) and achievement of patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS; ≤ 10 points, patient-reported items only).

Results

Overall, 200 patients received rozanolixizumab 7 mg/kg (n = 66), 10 mg/kg (n = 67) or placebo (n = 67). The MGII was completed by 144/200 (72.0%) patients. Mean CFB in MGII total score was greater in the rozanolixizumab groups versus placebo; mean CFB in ocular and generalized subscores was consistent with the total score. At Day 43, 57.1%, 83.3% and 40.4% of patients, respectively, were responders, and 30.8%, 39.2% and 7.7%, respectively, achieved MGII PASS. Responsiveness correlations between MGII total score CFB and MG-ADL anchor at Day 43 demonstrated a Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.5991 (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

These findings further support efficacy analyses from MycarinG to highlight the benefit of rozanolixizumab in patients with gMG and demonstrate the utility of the MGII in evaluating patient-relevant symptoms following treatment.

Trial registration

NCT03971422 (registered May 29, 2019).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00415-025-13480-8.

Keywords: Myasthenia gravis, Generalized myasthenia gravis, Myasthenia gravis impairment index, Rozanolixizumab, Phase 3 clinical trial

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder of the postsynaptic membrane at the neuromuscular junction that is predominantly characterized by fluctuating and unpredictable muscle weakness [1]. Approximately 15% of individuals experience ocular symptoms only, while 85% have generalized MG (gMG) that can also affect the face, neck and limbs [1, 2]. Symptoms vary in frequency and severity over the course of the day or across days, and these fluctuations can have substantial emotional, physical and social impacts [2]. While several disease-specific outcome measures have been developed, the fluctuating nature of the signs and symptoms of MG can make clinical assessment challenging [3].

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are an increasingly recognized and important part of understanding the effectiveness of interventions in MG [3, 4]. The Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) is a PRO measure often used as a primary efficacy endpoint in studies investigating new gMG treatments. It is frequently complemented by assessment with Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG), which contains clinician-reported and performance outcome items [4–7]. Both the MG-ADL and QMG are validated and reliable scales that are used in clinical trials, observational studies and clinical practice to measure gMG symptom severity and response to treatment [3, 4]. The MG-ADL is an 8-item PRO measure that can be used to gain useful insights into the impact of gMG on daily activities [4–6]. The QMG is a 13-item standardized clinician assessment of muscle strength and fatigability at the time of the clinical visit and to determine any changes from previous visits [3, 7]. Limitations have been noted for both scales [8]. The MG-ADL has a variable recall period and administration instructions (both as a self-administered or interviewer-administered PRO) that may affect comparability of results across studies, while the QMG is a single timepoint assessment which may not capture disease fluctuations and lacks standardized instructions [3, 8]. Recommendations to improve the standardization of MG outcome measures, including the MG-ADL and QMG, have been made for the benefit of future clinical trials and clinical practice [4, 8, 9].

The Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index (MGII) was developed in accordance with guidelines from the US Food and Drug Administration on designing PRO measures and the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN), and incorporates the patient’s perspective and the physician’s evaluation of impairment caused by MG [10, 11]. A qualitative study using in-depth interviews with content analysis explored patient experiences to create a conceptual framework for evaluating impairments from MG [10]. The framework highlighted that fatigability, defined as the triggering or worsening of an impairment with usual activities or onset or worsening over the course of the day, was a driver of overall disease severity. The MGII was developed using this framework to ensure content validity and comprises a total of 22 patient-reported items that form the patient questionnaire and 6 examination items (Table 1) [11]. The MGII has been selected as a primary or secondary endpoint in several Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials that were recruiting patients with either gMG or ocular MG at the time of writing [12–15]. However, published reports to date on the use of the MGII as an outcome measure have been of single-center studies of retrospective chart reviews or prospective cohort data for validating the instrument in different languages [16–22]. Data describing the use of the MGII in clinical research are therefore of interest and can provide context for future studies that utilize the MGII as a trial endpoint.

Table 1.

MGII individual items with score range, grouped by theme

| Patient-reported items with score range | Examination items with score range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problems with your eyesa | Problems eatingb | Problems speaking and breathingb | Generalized symptomsb | ||||||

| Double vision throughout the day | 0–3 | Difficulty swallowing | 0–4 |

Voice changes through the day |

0–3 | Overall physical tiredness | 0–3 | Diplopiaa | 0–3 |

| Double vision with activities | 0–3 | Chewing different types of food | 0–3 | Voice changes with prolonged conversation | 0–3 | Arm weakness severity | 0–3 | Ptosisa | 0–2 |

|

Severity of double vision |

0–3 | Chewing tiredness/fatigue | 0–3 | Severity of voice changes | 0–3 | Arm weakness with prolonged use | 0–3 | Lower facial strengthb | 0–2 |

| Eyelid drooping throughout the day | 0–3 |

Speech clarity through the day |

0–3 | Leg weakness severity | 0–3 | Arm enduranceb | 0–3 | ||

|

Eyelid drooping with activity |

0–3 |

Speech clarity with prolonged conversation |

0–3 |

Leg weakness with prolonged use |

0–3 | Leg enduranceb | 0–3 | ||

|

Severity of eyelid drooping |

0–3 |

Severity of speech changes |

0–3 | Neck weakness | 0–3 | Neck enduranceb | 0–3 | ||

| Difficulty breathing | 0–4 | ||||||||

MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index

aThese items comprise the ocular subscore, with a score range of 0–23

bThese items comprise the generalized subscore, with a score range of 0–61

In the Phase 3 MycarinG study investigating the efficacy and safety of rozanolixizumab in patients with gMG, change from baseline in MGII was an optional assessment [23]. Rozanolixizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin (Ig) G4 monoclonal antibody that inhibits the neonatal Fc receptor to reduce levels of pathogenic IgG autoantibodies that are implicated in MG pathophysiology [24]. In MycarinG, statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements from baseline were observed in MG-ADL, QMG and MGC total scores with rozanolixizumab treatment compared with placebo [23]. Rozanolixizumab was also generally well tolerated at both investigated doses. The current exploratory analyses aimed to understand the effect of rozanolixizumab on symptoms of MG using the MGII in the MycarinG study, and to use the study data to highlight the advantages and disadvantages of the MGII as an outcome measure in MG. A plain language summary of this analysis is available in Online Resource 1.

Methods

Study design and patient population

MycarinG (NCT03971422) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter Phase 3 study; full details of the study design were published previously [23]. In brief, patients were ≥ 18 years of age with anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) or anti-muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) antibody-positive gMG, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Disease Class II–IVa, MG-ADL score ≥ 3 (for non-ocular symptoms), QMG score ≥ 11, and had been considered for additional therapy such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange (PLEX). Patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to receive once-weekly subcutaneous rozanolixizumab 7 mg/kg, rozanolixizumab 10 mg/kg or placebo for 6 weeks.

Outcomes and assessments

The MycarinG study’s primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline to Day 43 in MG-ADL total score. Secondary endpoints included change from baseline to Day 43 in Myasthenia Gravis Composite (MGC), QMG and MG Symptoms PRO (Muscle Weakness Fatigability, Physical Fatigue, and Bulbar Muscle Weakness scales) scores and MG-ADL responder rates (≥ 2-point improvement [6]) at Day 43.

Exploratory endpoints included change from baseline to Day 43 in MGII total score and in ocular and generalized subscores. MGII was an optional assessment for all study participants, and data were collected on paper at baseline and at Day 43. A total score with a range of 0–84 reflects overall disease severity, where higher scores reflect greater impairment [11]. Items may also be grouped to calculate an ocular subscore and a generalized subscore (Table 1). The patient questionnaire has a 2 week recall period and can be used either as a standalone instrument or with the examination items to support clinical decision-making. In MycarinG, MGII subscores were generated if there was a minimum of 7 of 8 items in the ocular domain and 18 of 20 items in the generalized domain, and the total score was calculated if both subscores were available.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were descriptive. Post hoc analyses of the MGII data collected in MycarinG included the application of previously determined thresholds for the minimal important difference (MID), i.e. the smallest change that is considered meaningful by patients at the group level or individual level. The MID for MGII total score has been established as 8.1 points at the group level and 5.5 points at the individual level [25]; the latter threshold was used to determine whether patients can be classed as responders following treatment in MycarinG.

Patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS) is a method of assessing treatment efficacy by evaluating the patient’s satisfaction with overall disease burden and whether they feel well, and not just better, following treatment [26]. PASS thresholds were previously estimated for the MGII in a separate study in which patients were asked to answer yes or no to the question, “Considering all the ways you are affected by myasthenia, if you had to stay in your current state for the next months, would you say that your current disease state status is satisfactory?” [26] Patients who achieve the PASS threshold may be classified as being well with respect to the symptoms measured by the MGII. The PASS threshold was estimated as ≤ 10 points for MGII total score (patient-reported items only). PASS thresholds were also retrospectively and indirectly determined using the MGII PASS threshold and validation cohort as ≤ 2 points for MG-ADL, ≤ 7 points for QMG and ≤ 3 points for MGC [26]. These thresholds were used to determine the proportion of patients in MycarinG achieving PASS on each scale.

An analysis of the mean change from baseline to Day 43 in MGII individual item scores was conducted in patients with baseline score ≥ 1 for that item. Items were divided into four categories described in the patient questionnaire of the MGII (“problems with your eyes,” “problems eating,” “problems speaking and breathing” and “generalized symptoms”).

The responsiveness of the MGII instrument, or sensitivity to change over time, was investigated by correlating its change from baseline scores at Day 43 with predefined MG-ADL anchor categories. Spearman’s correlation was used to determine appropriateness of the used anchor for assessing MGII responsiveness, with statistical significance at the 5% level, and a correlation coefficient ≥ 0.3 indicating that the anchor is appropriate [27]. The MG-ADL anchor categories were defined as: − 2 for achievement of minimal symptom expression (MSE; MG-ADL score 0 or 1), − 1 for ≥ 2-point improvement (i.e. clinically meaningful change in MG-ADL) without achieving MSE, 0 for ≤ 1-point change (i.e. no meaningful change), and + 1 for ≥ 2-point worsening [6]. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to assess the relationship between the MGII and MG-ADL. Medium-to-large effect sizes should be obtained in patients considered to have experienced improvement using the anchor scale(s) to conclude that the MGII measure is responsive to change [28].

Results

MycarinG study population and MGII data collection

In MycarinG, 200 patients were treated with either rozanolixizumab 7 mg/kg (n = 66), rozanolixizumab 10 mg/kg (n = 67) or placebo (n = 67). Overall, 179 (89.5%) patients had anti-AChR antibody-positive gMG and 21 (10.5%) patients had anti-MuSK antibody-positive gMG. Baseline mean (SD) MG-ADL and QMG total scores across the total population were 8.3 (3.4) and 15.6 (3.6), respectively. Full baseline disease characteristics are published elsewhere [23]. In total, 144/200 (72.0%) patients who completed the MGII assessment both at baseline and at Day 43 were included in the analysis (rozanolixizumab 7 mg/kg: n = 49; rozanolixizumab 10 mg/kg: n = 48; placebo: n = 47). There were no notable differences in baseline characteristics between these patients and the total MycarinG population.

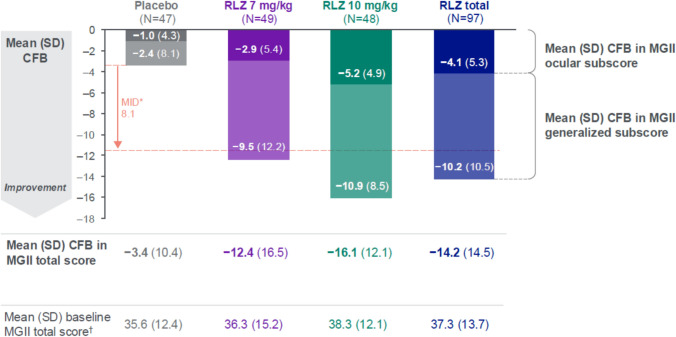

Change from baseline to Day 43 in MGII total score

Mean change from baseline to Day 43 in MGII total score was greater in both rozanolixizumab treatment groups compared with the placebo group (Fig. 1). The difference versus placebo was largest in the 10 mg/kg group, with mean change from baseline to Day 43 of − 16.1 in the 10 mg/kg group and − 12.4 in the 7 mg/kg group compared with − 3.4 in the placebo group. Mean change from baseline in the ocular and generalized subscores was consistent with results for the MGII total score. Both rozanolixizumab groups surpassed the MID threshold at the group level, measured from the mean change from baseline in the placebo group.

Fig. 1.

Mean (SD) CFB to Day 43 in MGII total score and ocular and generalized subscores with MID at the group level. Randomized set. N is the number of patients who were included in the CFB at Day 43 analysis. *MID in MGII total score is 8.1 points for groups [25]; the threshold was determined as − 11.5 points when the MID was measured from the placebo mean CFB of − 3.4. †Patients with MGII data at baseline: N = 53, N = 55, N = 54 and N = 109 in the placebo, RLZ 7 mg/kg, RLZ 10 mg/kg and RLZ total groups, respectively. Figure adapted with permission from Bril V, Drużdż A, Grosskreutz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of rozanolixizumab in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis (MycarinG): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, adaptive Phase 3 study. Lancet Neurol. 2023; 22(5):383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(23)00077-7. CFB Change from baseline, MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index, MID Minimal important difference, RLZ Rozanolixizumab, SD Standard deviation

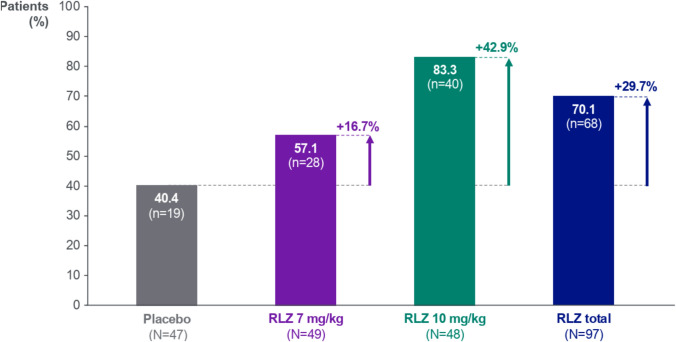

MGII response rates at Day 43

At Day 43, greater proportions of patients receiving rozanolixizumab achieved MGII response compared with those receiving placebo, defined as achieving the MID threshold of a ≥ 5.5-point improvement for individuals (Fig. 2). MGII responders comprised 70.1% of rozanolixizumab-treated patients compared with 40.4% of placebo-treated patients. The highest percentage of responders was 83.3% in the rozanolixizumab 10 mg/kg group, a response rate that was 42.9 percentage points higher than in the placebo group.

Fig. 2.

MGII response rates at Day 43. Randomized set. Responders were defined as patients who achieved the MID in MGII total score of 5.5 points for individuals [25]. Percentages are based on the number of patients with non-missing data at each visit in the randomized set. N is the number of patients in each group assessed at Day 43. MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index, MID Minimal important difference, RLZ, Rozanolixizumab

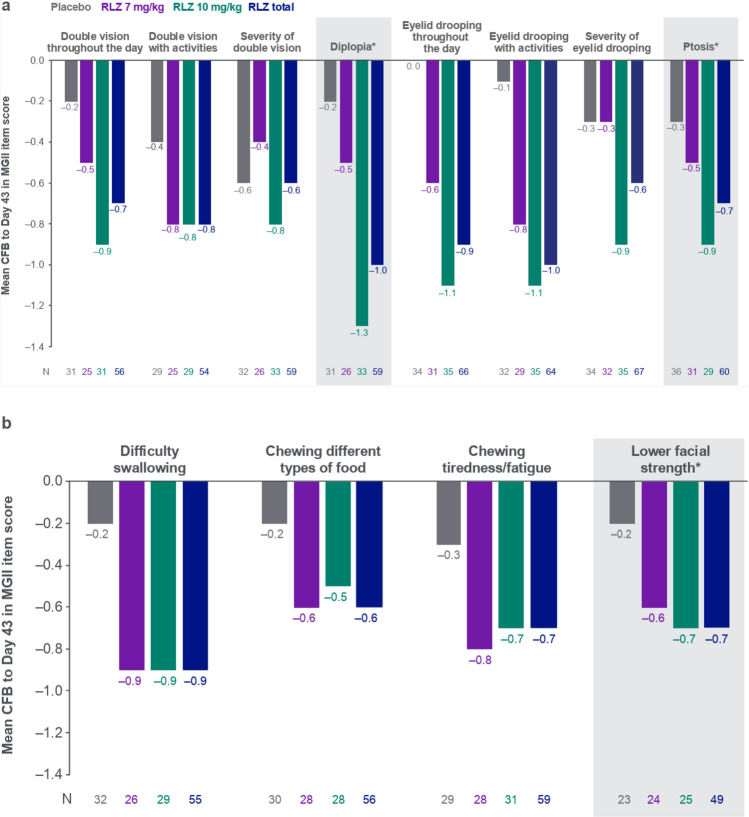

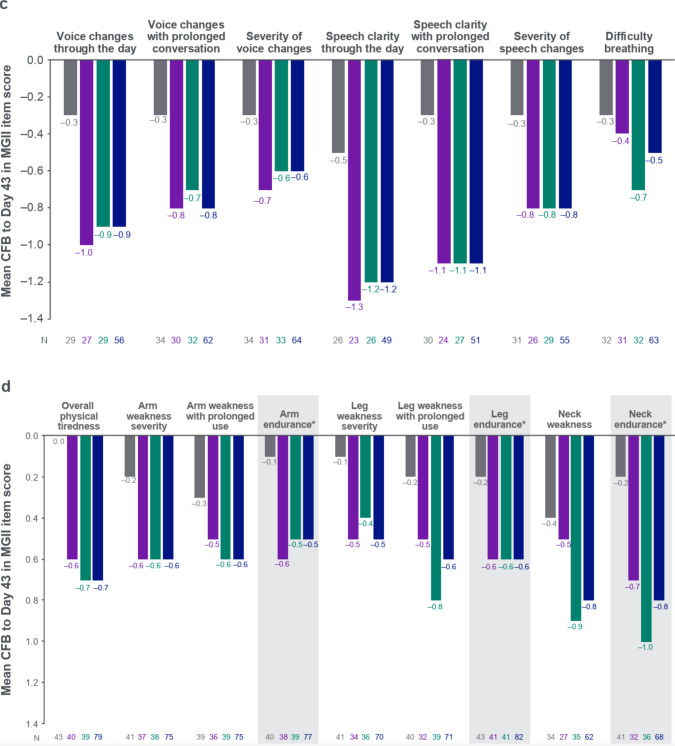

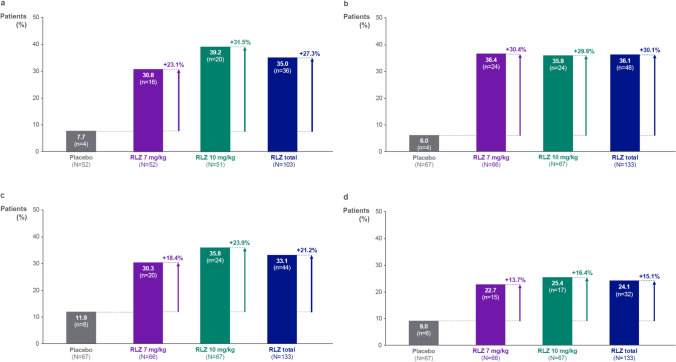

MGII item-level and shift analyses

Analysis of individual MGII items showed that the rozanolixizumab groups generally experienced greater improvements at Day 43 compared with the placebo group (Fig. 3a–d). Mean change from baseline was higher in both rozanolixizumab groups than in the placebo group for all items except for “severity of eyelid drooping” and “severity of double vision,” where the mean change in score for the 7 mg/kg group was equal to or lower than the placebo group.

Fig. 3.

CFB to Day 43 in MGII individual items, grouped by a problems with your eyes, b problems eating, c problems speaking and breathing, and d generalized symptoms. Randomized set. In patients with baseline item score ≥ 1. Baseline is the last available value prior to the first injection of study drug in the treatment period, or if missing, the screening value. *Examination item. CFB Change from baseline, MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index, RLZ Rozanolixizumab

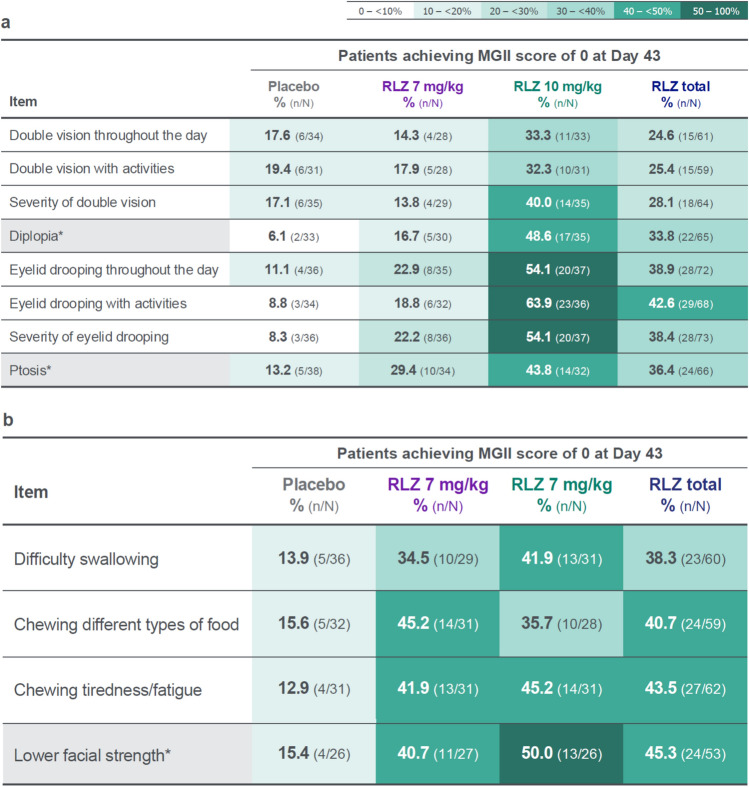

A shift analysis of patients with an item score of ≥ 1 at baseline who achieved a score of 0 at Day 43 showed that, in general, greater proportions of patients in the rozanolixizumab groups experienced an absence of symptoms measured by the MGII after treatment compared with the placebo group (Fig. 4a–d). Proportions of patients achieving a score of 0 at Day 43 were greater in the rozanolixizumab 7 mg/kg group than in the placebo group for most items except for the three patient-reported items for double vision and for “neck weakness.” This trend was not observed in the related examination items “diplopia” and “neck endurance.” Proportions of patients achieving a score of 0 at Day 43 were greater in the rozanolixizumab 10 mg/kg group than in the placebo group for all items. At least half of the patients in the 10 mg/kg group achieved a score of 0 in the three items for eyelid drooping, the three items for speech clarity/changes, and in the “lower facial strength” examination item.

Fig. 4.

Shift from score of ≥ 1 at baseline to score of 0 at Day 43 in individual items, grouped by a problems with your eyes, b problems eating, c problems speaking and breathing, and d generalized symptoms. Randomized set. Baseline is the last available value prior to the first injection of study drug in the treatment period, or if missing, the screening value. *Examination item. MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index, RLZ rozanolixizumab

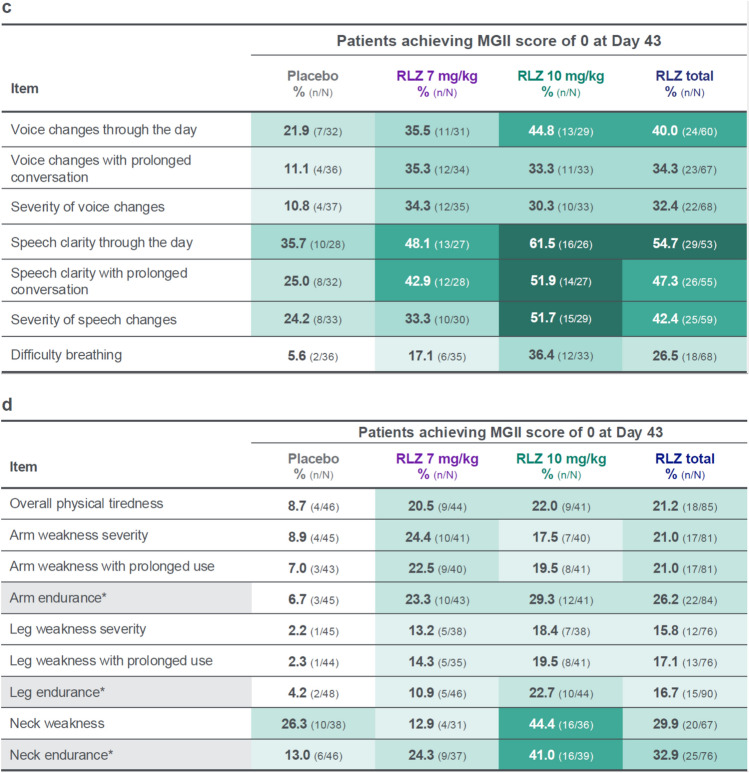

Indirect PASS responder rates

The PASS threshold for the MGII, MG-ADL, QMG and MGC scales was achieved by consistently higher proportions of patients in the rozanolixizumab groups than in the placebo group (Fig. 5a–d). A total of 36/103 (35.0%) rozanolixizumab-treated patients achieved the PASS threshold on the MGII compared with 4/52 (7.7%) placebo-treated patients. The proportions of patients achieving the PASS thresholds on the MG-ADL, QMG and MGC scales showed similar trends and were 13.7–30.4% higher in the rozanolixizumab groups compared with the placebo group. Of the 36 MGII PASS responders with rozanolixizumab, 33 (91.7%) achieved PASS on at least one other scale; 83.3% of MGII PASS responders also achieved PASS on MG-ADL, 61.1% on QMG and 55.6% on MGC.

Fig. 5.

Indirect PASS responder rates for a MGII, b MG-ADL, c QMG, and d MGC. Randomized set. MGII, MG-ADL, QMG and MGC PASS achievement were defined as having ≤ 10-point, ≤ 2-point, ≤ 7-point and ≤ 3-point total score during the treatment period, respectively. MGII PASS achievement was measured across the 22 patient-reported items only. N is the number of patients in each group assessed at Day 43. MG-ADL Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living, MGC Myasthenia Gravis Composite, MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index, PASS Patient-acceptable symptom state, QMG Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis, RLZ Rozanolixizumab

MGII responsiveness to change

Responsiveness correlations between change from baseline in MGII total score and MG-ADL anchor at Day 43 resulted in a Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.5991 (p < 0.0001; Fig. 6). An ANCOVA analysis provided least squares mean change from baseline at Day 43 that had a logical magnitude and direction across the anchor levels. Improvements in MG-ADL levels were associated with improvements in MGII. Least squares mean change from baseline was − 31.04, − 11.81, − 2.49 and 3.84 for the MG-ADL anchor level of − 2, − 1, 0 and + 1, respectively; p < 0.05 for all except for MG-ADL anchor of + 1. Similar trends were observed in the measures of effect size (− 2.26, − 0.86, − 0.18 and 0.28, respectively); these effect sizes for the groups considered to have improved (− 2 and − 1) can be considered large effects. Together, the results of these analyses suggest that the MGII is responsive to change.

Fig. 6.

Scatter plot of responsiveness correlations between CFB in MGII total score and CFB in MG-ADL anchor at Day 43. Complete case analysis including all patients in the randomized set with non-missing MGII and MG-ADL total scores at baseline and Day 43. The MG-ADL anchor was classified as − 2 if achieving MSE (MG-ADL score of 0–1), − 1 for a ≥ 2-point improvement without MSE, 0 for a change of ≤ 1, and + 1 for ≥ 2-point worsening. Correlation coefficient and p-value were based on Spearman’s correlation. CFB Change from baseline, MG-ADL Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living, MGII Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index, MSE Minimal symptom expression

Discussion

This publication presents the first data on use of the MGII in a clinical trial of a targeted therapy. The results expand upon the primary and secondary analyses from MycarinG. Despite being an optional assessment, 72.0% of patients completed the MGII at baseline and at Day 43, suggesting that there was interest in the scale among most participating clinics and that the additional assessment was not considered a burden. Improvements measured by the MGII were consistently greater in rozanolixizumab-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients, in line with the prespecified efficacy analyses from MycarinG [23], exceeded MID thresholds for MGII total score, and were generally greater in the rozanolixizumab 10 mg/kg group than in the 7 mg/kg group.

MGII ocular and generalized subscores have previously shown differential responsiveness to intervention [25]; however, in MycarinG, greater improvements were observed with rozanolixizumab than with placebo across both subscores and the vast majority of items, suggesting a consistent treatment effect with rozanolixizumab. The observation of no improvement for “overall physical tiredness” in the placebo group compared with improvements in the rozanolixizumab groups is noteworthy, given that physical fatigue is a commonly reported symptom in gMG but is not measured by the MG-ADL or QMG [2, 5, 7, 29]. The lower or comparable improvement in the 7 mg/kg group compared with the placebo group for the items “severity of double vision” and “severity of eyelid drooping” was not observed in the related examination items “ptosis” and “diplopia.” This reflects a difference between patient and clinician reports of similar symptoms, and highlights a need for both perspectives when assessing MG symptoms. While clinician assessments with no patient-reported component (such as QMG) evaluate symptoms at a single timepoint during a clinical visit, PROs may particularly help in building a more accurate picture of impairment over long periods of time, by capturing the symptom fluctuations that are inherent to gMG [4, 10]. Expert consensus recommendations include the review of ocular item subscores of gMG assessments to evaluate specific ocular symptoms which can cause considerable burden to patients [4]. The MGII ocular subscore comprises eight items and is responsive to change, suggesting that it can be used to meet this need.

With expected utilization of the MGII as a primary or secondary endpoint in upcoming Phase 2 and 3 trials, these analyses of MycarinG study data provide valuable insights into how the instrument can be used to monitor the effect of treatment on symptoms that are most relevant to patients. For example, the MGII can discriminate between patients with pure ocular and with generalized gMG, as well as between different MGFA disease classes [11]. A previous study demonstrated that the MGII was sensitive to detecting change in patients who received prednisone, IVIg or PLEX treatments, with clinical change expected within a short period of time [25]. The large effect sizes obtained using MycarinG data also indicated that the MGII is responsive to change, further supporting its use in evaluating symptoms following treatment for gMG, and it is currently being utilized as a key endpoint in an ongoing Phase 3 trial for efgartigimod in the ADAPT OCULUS study [15]. This responsiveness is clinically relevant as it suggests that the MGII can capture meaningful improvements or deteriorations, which is critical for assessing the extent of treatment efficacy. The MGII demonstrated superior sensitivity to changes in generalized weakness compared with the MG-ADL, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of generalized symptoms. Thus, compared with the MG-ADL, the MGII provides a clearer picture of a patient’s sustained functional capacity, rather than just their immediate ability. Other scales have been developed to measure the symptoms and impact of gMG most relevant to patients, including the MG Symptoms PRO, which was also used in the MycarinG study [3, 23, 30, 31].

Another advantage of the MGII lies in its patient-centric development, leading to a more comprehensive and relevant assessment of MG symptoms from the patient’s perspective [11]. Its ease of use further enhances its practical utility. Moreover, it has smaller floor effects for generalized symptoms compared with some MG-specific outcome measures, and a higher relative efficiency in its responsiveness to treatment, suggesting that it may be more responsive to change in individuals who are at the lower end of the score range (i.e. with less severe disease) [11, 21, 25]. Disadvantages of the MGII include its potentially longer administration time compared with the MG-ADL. This is primarily due to its greater number of items and examination component, which may affect its feasibility in very busy clinical settings. The MGII reliability and construct validity studies were conducted in a single academic center and it is possible that some patients with milder disease, who are often followed in community settings, may not have been fully represented in these initial validation cohorts, potentially limiting the wider relevance of these findings to the broader gMG population [11].

PASS thresholds have been suggested as a holistic evaluation of the patient’s satisfaction with their overall disease burden that can complement clinical evaluations [26]. In a single-center cross-sectional study of 100 patients with gMG, one-third reported negative PASS status (i.e. dissatisfaction), which was associated with increasing MG symptoms, fatigue, depression, low MG-related QoL and shorter disease duration [32]. While PASS has been used in non-trial settings, this is the first report of PASS thresholds being applied (indirectly) to a clinical study dataset [20, 26, 32, 33]. Indirect PASS responder rates were consistently higher in the rozanolixizumab groups than in the placebo group, and PASS achievement rates of 22.7–39.2% after one cycle of rozanolixizumab treatment would be expected to increase with further treatment cycles. It should be noted that because QMG and MGC comprise clinician-reported and performance outcome items, PASS rates for these scales may reflect low disease activity state rather than acceptable symptom state for patients [26].

Limitations of these analyses include their exploratory and post hoc nature. The MGII was an optional assessment in MycarinG which was performed at a limited number of timepoints, not at all study sites, and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, a completion rate of over 70% for the MGII was achieved. The MID thresholds for the MGII are based on data from a small number of patients [25], and future research will need to confirm them. The PASS question was not directly asked in the MycarinG study, and concordance between PASS rates was assessed using the previously determined threshold [26] rather than obtained directly from the PASS question. PASS responder rates for MG-ADL, QMG and MGC were not calculated using the PASS anchor but instead calculated based on the MGII threshold [26]; however, a recent study that used a different methodology found similar cutoffs for minimal manifestations or better status [34]. Finally, responsiveness to change was determined using an MG-ADL anchor, which is not a typical anchor; however, the thresholds used (− 2, − 1, 0 and + 1) were based on established meaningful change and MSE definitions [6].

These analyses of MGII data further support the primary and secondary efficacy findings from the Phase 3 MycarinG study to highlight the treatment benefit of rozanolixizumab in patients with gMG. This is also the first report to demonstrate the utility of the MGII in the clinical trial setting for evaluating patient-relevant symptoms following treatment for gMG.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their caregivers who contributed to this study. The authors thank Veronica Porkess, PhD, of UCB for publication and editorial support. Medical writing support was provided by Alpa Parmar, PhD, CMPP, Ogilvy Health, London, UK, and was funded by UCB, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Author contributions

Carolina Barnett-Tapia, Jos Bloemers, Fiona Grimson and Thaïs Tarancón contributed to the analysis design and to the interpretation of the data. Elena Cortés Vicente, Robert M. Pascuzzi and Kimiaki Utsugisawa contributed to the acquisition of data by enrolling patients and to the interpretation of the data. Vera Bril contributed to the design or conceptualization of the study and the analysis, to the acquisition of data by enrolling patients and to the interpretation of the data. All authors had full access to study data, reviewed, edited, and provided final approval of the manuscript content, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by UCB. Authors were not paid to participate in the publication and were given access to the data from the study.

Data availability

Underlying data from this manuscript may be requested by qualified researchers 6 months after product approval in the United States and/or Europe or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymized individual patient-level data and redacted trial documents, which may include analysis-ready datasets, study protocol, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications and clinical study report. Prior to use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org and a signed data-sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a prespecified time, typically 12 months, on a password-protected portal.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

Carolina Barnett-Tapia has served as a paid Consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx, Janssen Pharmaceuticals (now Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine), Novartis and UCB. She has received research support from MGNet, Muscular Dystrophy Canada and the US Department of Defense. She is the primary developer of the MGII and may receive royalties for its use. Elena Cortés Vicente receives public speaking honoraria and compensation for advisory boards and/or consultation fees from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx, Janssen Pharmaceuticals (now Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine) and UCB. Robert M. Pascuzzi is Professor Emeritus of Neurology at Indiana University and receives compensation for his professional work from Indiana University Health. He has no financial relationship with any pharmaceutical company and receives no compensation from any pharmaceutical company (present or past). Robert M. Pascuzzi speaks at educational seminars on a broad variety of general neurology topics for primary care physicians through the organization Medical Education Resources (an educational organization with no links or ties to any pharmaceutical or healthcare business company). Therefore, Robert M. Pascuzzi has no conflicts of interest related to this research, manuscript, presentation, or publication. Kimiaki Utsugisawa has served as a paid Consultant for argenx, Chugai Pharmaceutical, HanAll Biopharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals (now Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine), Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, UCB and Viela Bio (now Amgen); he has received speaker honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx, the Japan Blood Products Organization and UCB. Jos Bloemers is an employee and shareholder of UCB. Fiona Grimson is an employee and shareholder of UCB. Thaïs Tarancón is an employee and shareholder of UCB. Vera Bril is a Consultant for Akcea, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alnylam, argenx, CSL, Grifols, Immunovant, Ionis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals (now Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine), Momenta (now Johnson & Johnson), Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Powell Mansfield, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda Pharmaceuticals and UCB. She has received research support from Akcea, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx, CSL, Grifols, Immunovant, Ionis, Momenta (now Johnson & Johnson), Octapharma, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, UCB and Viela Bio (now Amgen).

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. A national, regional or independent ethics committee or institutional review board (depending on site) approved the protocol. All patients provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Gilhus NE, Tzartos S, Evoli A, Palace J, Burns TM, Verschuuren J (2019) Myasthenia gravis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5(1):30. 10.1038/s41572-019-0079-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson K, Parthan A, Lauher-Charest M, Broderick L, Law N, Barnett C (2023) Understanding the symptom burden and impact of myasthenia gravis from the patient’s perspective: a qualitative study. Neurol Ther 12(1):107–128. 10.1007/s40120-022-00408-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett C, Herbelin L, Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ (2018) Measuring clinical treatment response in myasthenia gravis. Neurol Clin 36(2):339–353. 10.1016/j.ncl.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meisel A, Saccà F, Spillane J, Vissing J (2024) Expert consensus recommendations for improving and standardising the assessment of patients with generalised myasthenia gravis. Eur J Neurol 31(7):e16280. 10.1111/ene.16280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, Foster B, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ (1999) Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living profile. Neurology 52(7):1487–1489. 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muppidi S, Silvestri NJ, Tan R, Riggs K, Leighton T, Phillips GA (2022) Utilization of MG-ADL in myasthenia gravis clinical research and care. Muscle Nerve 65(6):630–639. 10.1002/mus.27476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barohn RJ, McIntire D, Herbelin L, Wolfe GI, Nations S, Bryan WW (1998) Reliability testing of the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis score. Ann N Y Acad Sci 841:769–772. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guptill JT, Benatar M, Granit V, Habib AA, Howard JF Jr, Barnett-Tapia C, Nowak RJ et al (2023) Addressing outcome measure variability in myasthenia gravis clinical trials. Neurology 101(10):442–451. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000207278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruzhansky K, Li Y, Wolfe GI, Muppidi S, Guptill JT, Hehir MK, Dimachkie MM et al (2025) Standardization of myasthenia gravis outcome measures in clinical practice: a report of the MGFA task force. Muscle Nerve 72(1):56–65. 10.1002/mus.28417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett C, Bril V, Kapral M, Kulkarni A, Davis AM (2014) A conceptual framework for evaluating impairments in myasthenia gravis. PLoS ONE 9(5):e98089. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett C, Bril V, Kapral M, Kulkarni A, Davis AM (2016) Development and validation of the Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index. Neurology 87(9):879–886. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT05067348. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05067348. Accessed January 2025.

- 13.ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT05919407. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05919407. Accessed January 2025.

- 14.ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT06587867. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06587867. Accessed January 2025.

- 15.ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT06558279. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06558279. Accessed January 2025.

- 16.Alcantara M, Sarpong E, Barnett C, Katzberg H, Bril V (2021) Chronic immunoglobulin maintenance therapy in myasthenia gravis. Eur J Neurol 28(2):639–646. 10.1111/ene.14547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menon D, Alnajjar S, Barnett C, Vijayan J, Katzberg H, Fathi D, Alcantara M et al (2021) Telephone consultation for myasthenia gravis care during the COVID-19 pandemic: assessment of a novel virtual myasthenia gravis index. Muscle Nerve 63(6):831–836. 10.1002/mus.27243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vijayan J, Menon D, Barnett C, Katzberg H, Lovblom LE, Bril V (2021) Clinical profile and impact of comorbidities in patients with very-late-onset myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 64(4):462–466. 10.1002/mus.27369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urra Pincheira A, Alnajjar S, Katzberg H, Barnett C, Daniyal L, Rohan R, Bril V (2022) Retrospective study on the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 66(5):558–561. 10.1002/mus.27657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Harms R, Barnett C, Alcantara M, Bril V (2024) Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with double-seronegative myasthenia gravis. Eur J Neurol 31(1):e16022. 10.1111/ene.16022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Meel RHP, Barnett C, Bril V, Tannemaat MR, Verschuuren JJGM (2020) Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index: sensitivity for change in generalized muscle weakness. J Neuromuscul Dis 7(3):297–300. 10.3233/jnd-200484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasqualin F, Barnett C, Guidoni SV, Albertini E, Ermani M, Bonifati DM (2022) Validation of the Italian version of the Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index (MGII). Neurol Sci 43(3):2059–2064. 10.1007/s10072-021-05585-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bril V, Drużdż A, Grosskreutz J, Habib AA, Mantegazza R, Sacconi S, Utsugisawa K et al (2023) Safety and efficacy of rozanolixizumab in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis (MycarinG): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, adaptive phase 3 study. Lancet Neurol 22(5):383–394. 10.1016/s1474-4422(23)00077-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith B, Kiessling A, Lledo-Garcia R, Dixon KL, Christodoulou L, Catley MC, Atherfold P et al (2018) Generation and characterization of a high affinity anti-human FcRn antibody, rozanolixizumab, and the effects of different molecular formats on the reduction of plasma IgG concentration. MAbs 10(7):1111–1130. 10.1080/19420862.2018.1505464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett C, Bril V, Kapral M, Kulkarni AV, Davis AM (2017) Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index: responsiveness, meaningful change, and relative efficiency. Neurology 89(23):2357–2364. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000004676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendoza M, Tran C, Bril V, Katzberg HD, Barnett C (2020) Patient-acceptable symptom states in myasthenia gravis. Neurology 95(12):e1617–e1628. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000010574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J (2008) Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 61(2):102–109. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey, US [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiter AM, Verschuuren JJGM, Tannemaat MR (2020) Fatigue in patients with myasthenia gravis. a systematic review of the literature. Neuromuscul Disord 30(8):631–639. 10.1016/j.nmd.2020.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleanthous S, Mork AC, Regnault A, Cano S, Kaminski HJ, Morel T (2021) Development of the Myasthenia Gravis (MG) Symptoms PRO: a case study of a patient-centred outcome measure in rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 16(1):457. 10.1186/s13023-021-02064-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regnault A, Habib AA, Creel K, Kaminski HJ, Morel T (2024) Clinical meaningfulness and psychometric robustness of the MG Symptoms PRO scales in clinical trials in adults with myasthenia gravis. Front Neurol 15:1368525. 10.3389/fneur.2024.1368525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen LK, Jakobsson AS, Revsbech KL, Vissing J (2022) Causes of symptom dissatisfaction in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 269(6):3086–3093. 10.1007/s00415-021-10902-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez-Harms R, Barnett C, Bril V (2023) Time to achieve a patient acceptable symptom state in myasthenia gravis. Front Neurol 14:1187189. 10.3389/fneur.2023.1187189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe G, Takai Y, Nagane Y, Kubota T, Yasuda M, Akamine H, Onishi Y et al (2024) Cutoffs on severity metrics for minimal manifestations or better status in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis. Front Immunol 15:1502721. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1502721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Underlying data from this manuscript may be requested by qualified researchers 6 months after product approval in the United States and/or Europe or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymized individual patient-level data and redacted trial documents, which may include analysis-ready datasets, study protocol, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications and clinical study report. Prior to use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org and a signed data-sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a prespecified time, typically 12 months, on a password-protected portal.