Abstract

Riemerella anatipestifer (R. anatipestifer) poses a serious threat to poultry, leading to substantial economic losses to the poultry industry. The escalating prevalence of antibiotic resistance in R. anatipestifer underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic agents. In this study, we demonstrated that Sophoraflavanone G (SFG), a lavandulylated flavanone derived from Sophora flavescens, exhibits rapid bactericidal activity against R. anatipestifer in vitro and shows a low propensity for inducing drug resistance. Mechanistic studies indicate that SFG binds to phosphatidylglycerol, compromising the structural and functional integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane in R. anatipestifer, which results in the leakage of intracellular contents. Further studies demonstrate that SFG disrupts bacterial proton motive force, promotes the intracellular accumulation of ATP and reactive oxygen species, and inhibits DNA and RNA biosynthesis. In the peritonitis model, SFG treatment significantly reduced the bacterial load in the tissues of infected ducklings and attenuated the tissue damage caused by R. anatipestifer infection. In conclusion, SFG represents a promising antibacterial agent with a low propensity for resistance development, offering potential for combating R. anatipestifer infections.

Keywords: Sophoraflavanone G, Riemerella anatipestifer, Antibacterial

Introduction

Riemerella anatipestifer (R. anatipestifer), a Gram-negative bacterium, is a major pathogen responsible for several waterfowl diseases (Segers et al., 1993), including septicemia, pericarditis, and perihepatitis (Yehia et al., 2023). These infections cause substantial economic losses in the global waterfowl industry. R. anatipestifer exhibits extensive antigenic diversity across numerous serotypes (Ke et al., 2022). Consequently, existing vaccines targeting single serotypes often show limited efficacy in disease control (Kang et al., 2018). Antibiotic therapy represents an important immediate therapeutic strategy for managing R. anatipestifer infections (Tang et al., 2018). However, indiscriminate or prolonged antibiotic use in animal agriculture has exacerbated multidrug resistance in R. anatipestifer, thereby diminishing the efficacy of conventional antimicrobials against this pathogen (Huang et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2018; Umar et al., 2021; Hao et al., 2025). Consequently, the development of novel antimicrobial agents is urgently required for managing R. anatipestifer infections.

Plants synthesize a diverse array of bioactive compounds as part of their evolutionary defense mechanisms against microbial pathogens, making these metabolites valuable reservoirs for antimicrobial drug discovery (Cowan, 1999). Flavonoids, the largest and most structurally diverse class of plant-derived natural products, have garnered significant attention as antimicrobial agents owing to their well-established bacteriostatic and bactericidal properties (Cushnie et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2024). In contrast to conventional antibiotics, bioactive constituents derived from traditional Chinese medicine not only exhibit inherent bactericidal activity but also provide a promising strategy to circumvent bacterial multidrug resistance (Wang et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020).

Sophora flavescens, a traditional Chinese medicinal herb, is clinically used for the treatment of dermatological disorders and bacterial diarrhea (He et al., 2015). Contemporary pharmacological studies have identified Sophora flavescens as a rich source of alkaloids and flavonoids that exhibit diverse pharmacological activities (Lin et al., 2023). Sophoraflavanone G (SFG), a lavandulylated flavanone derived from Sophora flavescens, exhibits potent antibacterial activity (Li et al., 2022; Weng et al., 2024). Furthermore, SFG shows synergistic effects when combined with conventional antibiotics, thereby markedly enhancing their antimicrobial efficacy (Sakagami et al., 1998; Sun et al., 2020). This compound exhibits favorable pharmacological properties and holds promise as a leading candidate with respect to antibacterial efficacy and safety. In this study, we evaluated the antibacterial activity of SFG both in vitro and in vivo against R. anatipestifer infection and preliminarily elucidated its antibacterial mechanism, thereby highlighting its potential as a promising lead compound for antibacterial drug development.

Methods and materials

Bacterial strains and chemicals

The R. anatipestifer strain ATCC 11845, and 10 clinical R. anatipestifer isolates were used in this study (Table 1). Tryptic soy broth (TSB; Huankai, Guangzhou, China) or tryptic soy agar (TSA; Huankai, Guangzhou, China) were utilized for routine cultivation of R. anatipestifer. Sophoraflavanone G (SFG;≥98.0 %) was provided by Yuanye Technology Co. (China). Phosphatidylglycerol (PG, 841188P, ≥99 %), phosphatidyl-ethanolamine (PE, 840027P, ≥99 %), and cardiolipin (CL, 841199P, ≥99 %) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Table 1.

MIC and MBC of SFG for different kinds of bacteria.

| Strains | MIC (μg/mL) | MBC(μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Riemerella anatipestifer ATCC 11845 | 2 | 4 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | >256 | - |

| Salmonella ATCC 14028 | >256 | - |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 | >256 | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | 4 | 8 |

| GDH21D4 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D5 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D6 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D7 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D8 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D22 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D23 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D24 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D25 | 2 | 4 |

| GDH21D26 | 2 | 4 |

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of SFG was determined by the standard broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guideline (CLSI, 2020). Bacterial overnight cultures were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard, followed by two-fold serial dilution of the agent in TSB. Equal volumes of bacterial inoculum were dispensed into pre-sterilized 96-well microtiter plates and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) is the lowest concentration that reduces bacterial colonies by 99.9 %. The synergistic activity between SFG and PG, CL, PE were measured by using checkerboard assays.

In vitro time-killing curves

Overnight cultures of R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 were diluted to approximately 106 CFU/mL in TSB. Bacterial suspensions were treated with SFG at varying concentrations (1×, 2×, and 4×MIC), and incubated at 37°C with agitation at 180 rpm. At 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h post-inoculation, 100 μL aliquots of the cultures were serially diluted, and samples were plated onto TSA plates.

Resistance Studies

R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 cultures were subcultured into fresh broth containing SFG at subinhibitory concentrations (0.25–4×MIC). Following 24 h incubation at 37°C with 180 rpm agitation, bacteria demonstrating growth at the highest SFG concentration were selected as progenitor cultures for subsequent passages. Concurrently, the MIC of SFG against the passaged strains was determined via broth microdilution method. Florfenicol (FLR) and 1 % DMSO were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. This serial passaging procedure was repeated for 21 sequential passages. Post-passage bacterial suspensions were cryopreserved in 30 % glycerol broth at −80°C.

Safety assessment

The hemolytic activity of SFG was assessed using a defibrinated sheep erythrocyte assay. 2 % defibrinated sheep blood erythrocytes were treated with various concentrations of SFG (0–32μg/mL) for 1 h. PBS containing 2.5 % Triton X-100 and PBS alone served as the positive and negative controls, respectively. The fluorescence value at OD543 nm was measured to evaluate the rate of hemolysis, and the following formula was used to evaluate the rate of hemolysis, Equation (1):

Membrane permeability assay

The fluorescent dye Propidium iodide assay was used to determine the cell membrane permeability. Overnight cultures of R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 cells were washed and resuspended in PBS (pH=7.4), adjusted to a final concentration of OD600=0.5. Bacterial suspensions were first incubated with PI (0.5 µM) for 30 min, followed by treatment with SFG for 1 h at 37°C. Then PI with an excitation wavelength of 535 nm and emission wavelength of 615 nm was measured using an EnSight multimode plate reader.

Membrane potential assay

Membrane potential (Δψ) alterations in R. anatipestifer induced by SFG were assessed using 3,3′-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide [DiSC3(5)] (Beyotime, China). R. anatipestifer cells were washed thrice with 5 mM HEPES containing 20 mM glucose (pH=7.2) and adjusted to a final concentration of OD600 = 0.5. The cell suspensions were then incubated with 1 µM DiSC3(5) at 37°C for 30 min. Following treatment with varying concentrations of SFG, fluorescence was quantified at excitation and emission wavelengths of 622 nm and 670 nm.

ΔpH Assay

The intracellular pH (ΔpH) in R. anatipestifer was measured using the pH-sensitive fluorescent probe 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM) (Beyotime, China). BCECF-AM (5 mM) was incubated with bacterial suspension for 30 min, subsequently, incubated with SFG at 37°C for 30 min. Fluorescence was quantified at excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 nm and 535 nm.

Intracellular protein leakage test

To evaluate SFG-induced cell membrane damage, protein leakage was quantified in the culture supernatant using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime, China). R. anatipestifer was treated with SFG at various concentrations for 1 h. After incubation, cells were centrifuged (12,000×g, 10 min, 4°C), and the protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using the BCA kit. Set up three parallel tests for each test and repeat each test three times.

Intracellular macromolecule detection

The effects of SFG on DNA and RNA synthesis in R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 cells were assessed using the fluorescent dyes Hoechst 33342 (HO) and pyronin Y (PY). Briefly, 0.5 μg/mL HO and 2 μg/mL PY were incubated with bacterial suspension for 30 min, subsequently, incubated with SFG at 37°C for 1 h. The excitation and emission wavelengths of HO and PY are 350/461 nm and 530/580 nm respectively.

ATP determination

ATP levels in R. anatipestifer were measured using an Enhanced ATP Assay Kit. Bacterial suspensions were treated with SFG at varying concentrations (37°C, 1 h) to quantify extracellular ATP levels. Relative ATP concentrations were determined using EnSight multimode plate reader.

ROS detection

The effect of SFG on the ROS level in R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 was measured using the fluorescent dye DCFH-DA. DCFH-DA (10 μM) was incubated with bacterial suspension for 30 min, subsequently, incubated with SFG at 37°C for 1 h. Then the fluorescence value was determined by EnSight multimode plate reader, with the excitation wavelength at 488 nm and emission wavelength at 525 nm.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The structural alterations of R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 were examined using scanning electron microscopy. Briefly, bacterial cultures were collected, washed, resuspended in PBS, and treated with SFG at various concentrations for 1 h. After treatment, samples were fixed in 2.5 % glutaraldehyde solution. Ultrastructural observations were conducted using a Hitachi SU 8010 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Establishment of peritonitis model

Two-week-old male Cherry Valley ducklings (100±20 g) were used. Ducks were provided with an antimicrobial-free balanced diet and water ad libitum. Ducklings were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 6): (i) negative control (sterile PBS), (ii) positive control (infected, untreated), (iii) SFG low dose (5 mg/kg body weight), and (iv) SFG high dose (10 mg/kg body weight). Infectious peritonitis was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mL of a bacterial suspension at a concentration of 108 CFU/mL. (Qiu et al., 2016). At 3 h post-infection, the treatment groups received intramuscular SFG. At 24 h post-infection, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, and cerebral tissues were collected for bacterial load quantification. Prior to sampling, all animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. For histological evaluation, organs were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for microscopic examination. All procedures were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of South China Agricultural University (Approval No. SCAU-2024C085) and conducted in accordance with institutional and national animal welfare guidelines.

Statistical analysis

All the above experiments were repeated three times to ensure accuracy. The pictures were drawn using GraphPad Prism 10 software (GraphPad Software, USA). All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. ns, not significant. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Results

SFG is a potential antimicrobial agent

SFG exhibited potent antibacterial activity against both R. anatipestifer ATCC11845 and clinically isolated strains, with a consistent MIC of 2 μg/mL and an MBC of 4 μg/mL (Table 1). Furthermore, we found that SFG exhibited strong antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus but showed no activity against Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli (Table 1). Time-killing experiment revealed that SFG exerts pronounced concentration-dependent bactericidal effects (Fig. 1A). At 1×MIC, SFG eliminated most bacterial cells within 8 hours. At 2× and 4× MIC, SFG achieving 99.99 % bacterial eradication within 2 h and 1 h, respectively, demonstrating rapid and highly effective bactericidal activity.

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of the in vitro antibacterial activity of SFG. (A) In vitro time-killing curves of SFG against R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845. (B) Changes in the MIC of SFG and FLR for R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 after 21 days of serial passage. (C) Hemolytic activity of SFG on defibrillated sheep blood erythrocytes.

In serial passaging experiments, SFG demonstrated a low potential for resistance development, with only a 2-fold increase in MIC over 21 days, in contrast to florfenicol, which exhibited a 1024-fold increase under identical conditions. Safety assessment indicated a high selectivity index for SFG (Fig. 1B). The safety evaluation results show that no significant hemolytic activity was observed at therapeutically relevant concentrations (Fig. 1C).

SFG Disrupts R. anatipestifer cell membrane

Using R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 as a model organism, this study investigated the effects of SFG on the bacterial cell membrane. First, we employed SEM to examine the effects of SFG on bacterial morphology. After exposure to SFG at 1× MIC for 1 h, pores and ruptures were observed in the bacterial cell membrane. At 2× MIC, cells exhibited extensive membrane collapse accompanied by irregular surface depressions. Quantification of membrane permeability using PI revealed concentration-dependent enhancement by SFG (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, significant protein leakage in SFG-treated cells was confirmed by BCA assay quantification (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

The antibacterial mechanism of SFG against R. anatipestifer. (A) Bacterial morphology affected by SFG control group and treatment group. (B) The effect of different concentrations of SFG treatment on cell membrane permeability of R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 detected by dye PI. (C) Protein leakage in R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 cells after SFG treatment. (D) The effect of SFG treatment on Δψ of R. anatipestifer cells. (E) The effect of SFG treatment on ΔpH of R. anatipestifer cells. (F) The effect of major cell membrane components on the antimicrobial activity of SFG.

We next investigated the effect of SFG on the PMF. SFG treatment induced a concentration-dependent dissipation of the bacterial Δψ (Fig. 2D), while exerting minimal effects on the ΔpH (Fig. 2E). To evaluate the influence of membrane composition on the antibacterial activity of SFG, checkerboard assays were conducted with major membrane PE, PG, and CL. The results indicated that exogenous supplementation of PG reduced the inhibitory activity of SFG against R. anatipestifer in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2F). However, the addition of CL and PE had minimal impact on the antibacterial activity of SFG, demonstrating that PG in the cell membrane of R. anatipestifer likely serves as the potential target for SFG.

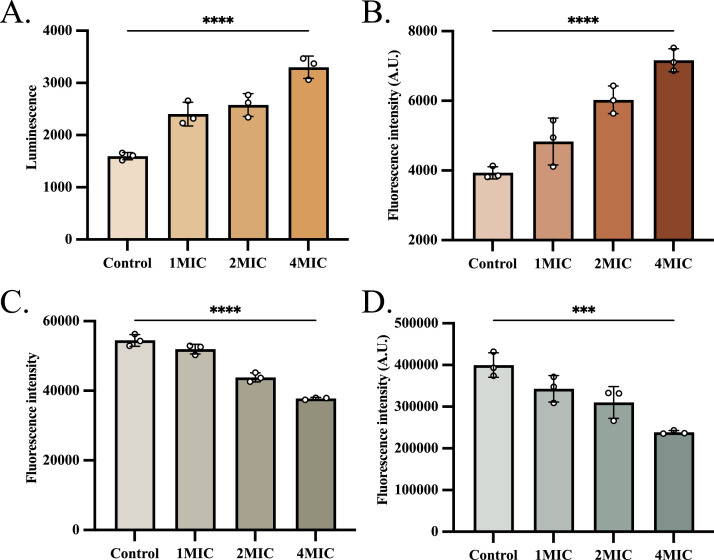

SFG disrupts the homeostasis of the intracellular physiological environment

We evaluated intracellular energy metabolism and nucleic acid metabolism to further elucidate the antibacterial mechanism of SFG. First, we quantified the total ATP levels in bacteria and found that SFG significantly enhanced ATP synthesis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). In addition, SFG treatment markedly increased intracellular ROS levels (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we assessed the effects of SFG on nucleic acid biosynthesis using fluorescent dyes. The results revealed that SFG significantly inhibited the biosynthesis of both DNA (Fig. 3C) and RNA (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

The effect of SFG on intracellular physiological pathways in R. anatipestifer. (A) The effect of SFG on intracellular ATP levels of R. anatipestifer. (B) The effect of SFG on ROS levels of R. anatipestifer. (C) The effect of SFG on DNA levels of R. anatipestifer. (D) The effect of SFG on RNA levels of R. anatipestifer.

SFG exhibited potent in vivo anti-R. anatipestifer activity

Given the potent in vitro antibacterial activity of SFG against R. anatipestifer, we evaluated its in vivo efficacy in a duckling model of peritonitis infection. Compared with negative control, SFG-treated ducks showed significantly reduced bacterial burdens in the brain, liver, lungs, and kidneys (Fig. 4B). Notably, treatment with SFG at 10 mg/kg reduced the bacterial load in the kidneys of ducklings by more than 3.3log10CFU/g (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 4.

The efficacy of SFG against R. anatipestifer in vivo. (A) Experimental protocol for induction of peritonitis in ducklings via R. anatipestifer infection. (B) Bacterial loads in the liver, kidney, lung, and brain tissues of ATCC11845-infected ducks after treatment with SFG. (C) Histologic analysis of different organs using HE staining. Pathological changes in liver, kidney, lung, brain and spleen histology after SFG treatment.

Histopathological analysis demonstrated marked inflammatory cell infiltration and nuclear pyknosis in tissues of positive control ducklings.However, SFG treatment markedly alleviated these pathological changes, with the spleen showing no significant differences compared with the negative control. In conclusion, these results demonstrate that SFG exerts effective therapeutic activity against R.anatipestifer infection in vivo.

Discussion

The global challenge of antimicrobial resistance continues to escalate (Collaborators, 2022), underscoring the urgent need for novel agents effective against drug-resistant bacterial infections. Although plant-derived bioactive compounds have long been used for various therapeutic purposes, their potential to combat clinically relevant pathogens and address multidrug resistance remains largely underexplored. As one of the most abundant groups of bioactive compounds in plants, flavonoids have been extensively investigated for their considerable pharmacological potential in treating diverse diseases (Wen et al., 2021).

This study investigated the antibacterial activity and underlying mechanism of action of SFG, a bioactive compound derived from Sophora flavescens. SFG exhibited potent inhibitory effects against both the reference strain R. anatipestifer ATCC 11845 and clinically isolated strains, demonstrating rapid bactericidal activity within a short timeframe. Moreover, in contrast to florfenicol, prolonged subinhibitory exposure to SFG did not result in notable resistance development in R. anatipestifer. Toxicity represents a major constraint in the clinical translation of antimicrobial agents (Tamma et al., 2017). No significant hemolytic activity was observed at therapeutically relevant concentrations. Even at 8×MIC, the hemolysis rate remained below 25 % (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these findings suggest that SFG represents a promising antibacterial agent with favorable efficacy and safety profiles.

SFG exhibits potent antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria but shows no inhibitory effect on Gram-negative species, with the notable exception of R. anatipestifer. Given the similar phospholipid composition of the cell membranes in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Dias et al., 2018), it is reasonable to propose that the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria with the exception of R. anatipestifer prevents SFG from reaching the phospholipid bilayer. Intriguingly, SFG displayed synergistic activity with colistin against Gram-negative pathogens such as Escherichia coli (Fig. S). This synergy is likely due to colistin-mediated disruption of the outer membrane, which facilitates SFG penetration and subsequent antibacterial action. In Gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane constitutes a major permeability barrier (Sperandeo et al., 2017), and the ability of antimicrobial agents to cross this barrier is a key determinant of their antibacterial efficacy. Therefore, we propose that structural differences in the outer membrane represent the primary reason forthe lack of antibacterial activity of SFG against other Gram-negative pathogens, in contrast to its efficacy against R. anatipestifer.

The integrity and functionality of the bacterial cell membrane are essential for survival, rendering it an attractive target for antimicrobial agents with significant therapeutic potential. The disruptive effect of SFG on the cell membrane of R. anatipestifer was corroborated by SEM, membrane permeability assay and protein leakage assays. Compromise of membrane integrity by SFG resulted in functional impairment of the bacterial membrane. Irreversible cellular damage is typically associated with altered permeability, leading to leakage of intracellular components such as proteins and nucleic acids (Dan et al., 2023). The proton motive force (PMF), generated through respiration-driven transmembrane potential (Δψ) and proton gradient (ΔpH) (Chen et al., 2016), serves as the primary cellular energy reservoir and is maintained through compensatory mechanisms. SFG treatment induced a concentration-dependent dissipation of Δψ. Despite its minimal impact on ΔpH, this dissipation was sufficient to disrupt PMF homeostasis. Since maintenance of transmembrane potential is critical for processes including energy production and solute transport, disruption of membrane potential serves as a reliable indicator of membrane damage and dysfunction (Stratford et al., 2019).

Energy derived from cellular respiration is stored as the PMF, which drives ATP synthesis (Vahidi et al., 2016). ATP serves as a universal energy currency that fuels numerous anabolic processes. Furthermore, ROS play crucial roles in bacterial physiology (Van Acker et al., 2017). However, excessive ROS accumulation causes oxidative damage to cellular components (Hong et al., 2019). SFG treatment induces significant elevation of intracellular ATP levels and ROS overproduction, ultimately disrupting bacterial intracellular homeostasis. Macromolecules such as DNA and RNA are essential for bacterial replication and survival. SFG profoundly suppressed DNA and RNA biosynthesis, thereby disrupting critical bacterial physiological pathways.

In the duckling peritonitis model, we observed that a low dose of SFG exerted only a limited antibacterial effect in brain tissue, whereas increasing the dose markedly reduced the bacterial burden in the brain. This finding suggests that higher doses of SFG may be required for the effective treatment of meningitis caused by R. anatipestifer. Histopathological analysis further demonstrated that SFG treatment markedly attenuated inflammatory alterations in duckling organs. Notably, spleen tissue from SFG-treated ducks showed histological features comparable to the negative control group, indicating that SFG may confer certain advantages in the management of bloodstream infections.

Conclusion

SFG is a safe antibacterial lead compound that exhibits potent bactericidal activity against R. anatipestifer and demonstrates a low propensity for resistance development. It efficiently penetrates the bacterial extracellular membrane and binds to PG, compromising membrane integrity. This disruption triggers leakage of intracellular contents and perturbs cellular homeostasis, ultimately leading to bacterial death. Collectively, these results highlight SFG as a promising therapeutic candidate for the treatment of R. anatipestifer infections.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of South China Agricultural University.

Fig. S The antibacterial effects of SFG synergy with Colistin.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yangyang Li: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Yixin Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. Wanxin Lin: Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Peng Wan: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Junhai Pan: Validation, Methodology. Huanzhong Ding: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Aknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers 2023YFD1800904 and 2023YFD1800900).

Footnotes

Scientific section: Microbiology and Food Safety

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2025.106000.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Chen M.T., Lo C.J. Using biophysics to monitor the essential protonmotive force in bacteria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;915:69–79. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-32189-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI . 30th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2020. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborators Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999;12(4):564–582. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie T.P., Lamb A.J. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;26(5):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan W., Gao J., Zhang J., Cao Y., Liu J., Sun Y., Wang J., Dai J. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of canthin-6-one against Staphylococcus aureus and its application on beef preservation. Food Control. 2023;147:10. [Google Scholar]

- Dias C., Pais J.P., Nunes R., Blázquez-Sánchez M.T., Marquês J.T., Almeida A.F., Serra P., Xavier N.M., Vila-Viçosa D., Machuqueiro M., Viana A.S., Martins A., Santos M.S., Pelerito A., Dias R., Tenreiro R., Oliveira M.C., Contino M., Colabufo N.A., de Almeida R.F.M., Rauter A.P. Sugar-based bactericides targeting phosphatidylethanolamine-enriched membranes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):4857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06488-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J., Zhang J., He X., Wang Y., Su J., Long J., Zhang L., Guo Z., Zheng Y., Wang M., Sun Y. Unveiling the silent threat: a comprehensive review of Riemerella anatipestifer - from pathogenesis to drug resistance. Poult. Sci. 2025;104(4) doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2025.104915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Fang J., Huang L., Wang J., Huang X. Sophora flavescens ait.: traditional usage, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;172:10–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Zeng J., Wang X., Drlica K., Zhao X. Post-stress bacterial cell death mediated by reactive oxygen species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u S. a. 2019 May 14;116(20):10064–10071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901730116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Yuan H., Liu M.F., Zhao X.X., Wang M.S., Jia R.Y., Chen S., Sun K.F., Yang Q., Wu Y., Chen X.Y., Cheng A.C., Zhu D.K. Type B chloramphenicol acetyltransferases are eesponsible for chloramphenicolN eesistance in Riemerella anatipestifer. China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:297. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M., Seo H.S., Soh S.H., Jang H.K. Immunogenicity and safety of a live Riemerella anatipestifer vaccine and the contribution of IgA to protective efficacy in Pekin ducks. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;222:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke T., Yang D., Yan Z., Yin L., Shen H., Luo C., Xu J., Zhou Q., Wei X., Chen F. Identification and pathogenicity analysis of the pathogen causing spotted spleen in muscovy duck. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.846298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Chai W.C., Wang Z.Y., Tang K.J., Chen J.Y., Venter H., Semple S.J., Xiang L. Bioactivity-guided isolation of compounds from Sophora flavescens with antibacterial activity against Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022;36(17):4340–4348. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2021.1983570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Chen X.J., He L., Yan X.L., Li Q.R., Zhang X., He M.H., Chang S., Tu B., Long Q.D., Zeng Z. Systematic elucidation of the bioactive alkaloids and potential mechanism from Sophora flavescens for the treatment of eczema via network pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023;301 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H.Y., Liu M.F., Wang M.S., Zhao X.X., Jia R.Y., Chen S., Sun K.F., Yang Q., Wu Y., Chen X.Y., Biville F., Zou Y.F., Jing B., Cheng A.C., Zhu D.K. A novel resistance gene, lnu(H), conferring resistance to lincosamides in Riemerella anatipestifer CH-2. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2018;51(1):136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z., Cao C., Qu Y., Lu Y., Sun M., Zhang Y., Zhong J., Zeng Z. In vivo activity of cefquinome against Riemerella anatipestifer using the pericarditis model in the duck. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;39(3):299–304. doi: 10.1111/jvp.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakagami Y., Mimura M., Kajimura K., Yokoyama H., Linuma M., Tanaka T., Ohyama M. Anti-MRSA activity of sophoraflavanone G and synergism with other antibacterial agents. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1998;27(2):98–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segers P., Mannheim W., Vancanneyt M., De Brandt K., Hinz K.H., Kersters K., Vandamme P. Riemerella anatipestifer gen. nov., comb. nov., the causative agent of septicemia anserum exsudativa, and its phylogenetic affiliation within the Flavobacterium-Cytophaga rRNA homology group. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1993;43(4):768–776. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-4-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandeo P., Martorana A.M., Polissi A. Lipopolysaccharide biogenesis and transport at the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2017;1862(11):1451–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford J.P., Edwards C., Ghanshyam M.J., Malyshev D., Delise M.A., Hayashi Y., Asally M. Electrically induced bacterial membrane-potential dynamics correspond to cellular proliferation capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u S. a. 2019;116(19):9552–9557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901788116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.L., Sun S.C., He J.M., Lan J.E., Gibbons S., Mu Q. Synergism of sophoraflavanone G with norfloxacin against effluxing antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;56(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamma P.D., Avdic E., Li D.X., Dzintars K., Cosgrove S.E. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMa Intern. Med. 2017;177(9):1308–1315. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T., Wu Y., Lin H., Li Y., Zuo H., Gao Q., Wang C., Pei X. The drug tolerant persisters of Riemerella anatipestifer can be eradicated by a combination of two or three antibiotics. BMC. Microbiol. 2018;18(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar Z., Chen Q., Tang B., Xu Y., Wang J., Zhang H., Ji K., Jia X., Feng Y. The poultry pathogen Riemerella anatipestifer appears as a reservoir for Tet(X) tigecycline resistance. Environ. Microbiol. 2021;23(12):7465–7482. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahidi S., Bi Y., Dunn S.D., Konermann L. Load-dependent destabilization of the gamma-rotor shaft in FOF1 ATP synthase revealed by hydrogen/deuterium-exchange mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. u S. a. 2016;113(9):2412–2417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520464113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker H., Coenye T. The role of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic-mediated killing of bacteria. Trends. Microbiol. 2017;25(6):456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Li L., Wang X., Li X., Zhang Y., Yu J., Jiang J., You X., Xiong Y.Q. Hypericin enhances beta-lactam antibiotics activity by inhibiting sarA expression in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2019;9(6):1174–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen K., Fang X., Yang J., Yao Y., Nandakumar K.S., Salem M.L., Cheng K. Recent eesearch on flavonoids and their biomedical applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021;28(5):1042–1066. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200713184138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng Z., Zeng F., Wang M., Guo S., Tang Z., Itagaki K., Lin Y., Shen X., Cao Y., Duan J.A., Wang F. Antimicrobial activities of lavandulylated flavonoids in Sophora flavences against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus via membrane disruption. J. Adv. Res. 2024;57:197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2023.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Jiang L., Ran W., Zhong K., Zhao Y., Gao H. Antimicrobial activities of natural flavonoids against foodborne pathogens and their application in food industry. Food Chem. 2024;460(Pt 1) doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wei L., Wang Y., Ding L., Guo Y., Sun X., Kong Y., Guo L., Guo T., Sun L. Inhibitory effect of the Traditional Chinese medicine ephedra sinica granules on Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumolysin. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020;43(6):994–999. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b20-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehia N., Salem H.M., Mahmmod Y., Said D., Samir M., Mawgod S.A., Sorour H.K., AbdelRahman M., Selim S., Saad A.M., El-Saadony M.T., El-Meihy R.M., Abd E.M., El-Tarabily K.A., Zanaty A.M. Common viral and bacterial avian respiratory infections: an updated review. Poult. Sci. 2023;102(5) doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.