Abstract

The primary mechanism that controls manganese (Mn) homeostasis in mammals is the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription factors by elevated Mn, which transcriptionally upregulates expression of the Mn efflux transporter SLC30A10 to reduce cellular/organismal Mn levels. Here, we identify an additional unexpected component of the Mn-induced and HIF-dependent homeostatic response that represses SLC30A10 expression. In cells, (1) Mn treatment upregulated expression of the transcription factor NR4A1 (also called Nur77); (2) NR4A1 knockdown increased SLC30A10 expression and reduced the sensitivity of wildtype, but not ΔSLC30A10, cells to Mn toxicity; and (3) overexpression of NR4A1 reduced SLC30A10 expression and increased sensitivity to Mn toxicity. Thus, NR4A1 is a Mn-responsive gene that contributes to the control of Mn homeostasis by repressing SLC30A10 expression. In addition, (1) in cells, the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 was attenuated by knockdown of both HIF1α and HIF2α and (2) in mice, Mn exposure upregulated expression of NR4A1 in the liver of control or tissue-specific HIF1α but not tissue-specific HIF2α knockout mice. Thus, the induction of NR4A1 by elevated Mn is HIF2 dependent. Collectively, current and prior results imply that the activation of HIF1/HIF2 during elevated Mn exposure has two opposing effects on SLC30A10 expression, direct transcriptional upregulation and indirect repression via NR4A1, that together set SLC30A10 expression to the level necessary to restore cellular Mn to the physiological range. The repressive arm of the HIF-mediated transcriptional cascade that controls SLC30A10 expression may be designed to prevent Mn deficiency, which may otherwise occur from prolonged or excessive upregulation of SLC30A10.

Keywords: manganese, NR4A1, Nur77, hypoxia-inducible factor, HIF, SLC30A10, ZnT10, metal homeostasis

Sophisticated homeostatic mechanisms ensure that intracellular levels of essential metals (e.g., iron [Fe], copper, zinc, and manganese [Mn]) are maintained within a narrow physiological range to prevent deficiency or toxicity. Mechanisms that control copper, Fe, and zinc homeostasis in mammalian systems have been known for ∼2 decades (1, 2, 3). In contrast, the primary control mechanism that regulates mammalian Mn homeostasis, via a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)–mediated transcriptional cascade, was defined only by our recent work (4, 5). HIFs are heterodimeric transcription factors formed by the association of a labile α-subunit (HIF1α and HIF2α are best characterized) with a common, stable β-subunit (6) (HIF heterodimers are named after the α-subunits). Under physiological conditions, HIFα-subunits are targeted for degradation by prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes (6), of which PHD2 is the main isoform (7). Using in vitro assays, human cell lines, and mouse models, we previously established that (1) elevated Mn inhibits PHD2 enzyme by outcompeting a catalytic Fe atom of the enzyme, which activates HIF1/HIF2-mediated transcription (4); (2) HIF1/HIF2 activation, in turn, directly increases transcription of the critical Mn efflux transporter SLC30A10 (5) (a hypoxia-response element in the SLC30A10 promoter is necessary and sufficient for the Mn-induced response (5)); and (3) SLC30A10 upregulation provides a pathway to reduce cellular and organismal Mn levels (5). Overall, the Mn-induced upregulation of SLC30A10 via HIF1/HIF2 is a critical homeostatic pathway that controls Mn levels in human-relevant mammalian systems (4, 5).

SLC30A10 is a specific Mn efflux transporter that controls brain Mn levels and protects against Mn-induced neurotoxicity via activity in the liver and intestines, which mediate Mn excretion, and direct Mn efflux activity in the brain (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). Humans harboring homozygous loss-of-function mutations in SLC30A10 develop hereditary Mn-induced neurotoxicity (8, 14, 17, 18, 19). The discovery that transcriptional upregulation of SLC30A10 is central to the homeostatic control of Mn (4, 5) is congruent with the fundamental role of SLC30A10 in controlling brain and body Mn levels (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). But, while we identified SLC30A10 as an important HIF1/HIF2 target gene (4, 5), HIFs regulate expression of numerous other genes (20). Consistent with this, our recent unbiased transcriptomic analyses in mice revealed that elevated Mn alters expression of diverse gene expression networks in the brain and liver, and HIF1 is a major driver of the Mn-induced transcriptomic changes (21, 22). Therefore, it is possible that Mn-induced changes in expression of other genes, which may or may not be HIF1/HIF2 dependent, may directly or indirectly impact SLC30A10 transcription and thereby modulate Mn homeostasis. Based on this rationale, the overall hypothesis of the current study was that, in addition to the direct transcriptional upregulation of SLC30A10 via HIF1/HIF2, there may be other regulatory processes that control SLC30A10 expression and Mn homeostasis.

In addition to gaining new insights about the control mechanisms of Mn homeostasis, the biomedical significance of Mn toxicity provides added relevance for testing our hypothesis. At elevated levels, Mn induces motor disease (8, 14, 17). Mn-induced motor disease may occur in individuals: (1) overexposed to Mn from occupational (e.g., welding, mining, etc.) or environmental (e.g., drinking water) sources (8, 14, 17); (2) with liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis) because the liver is a primary organ that excretes Mn (8, 9, 12, 14, 17); and (3) as described previously, carrying homozygous loss-of-function mutations in critical Mn transporters (e.g., SLC30A10) (8, 14, 17, 18, 19). Mn-induced motor disease is of substantial public health concern because of the extent of occupational and environmental exposure to elevated Mn in the population. As examples, estimates suggest that >100,000 welders in America are overexposed to Mn (17, 23), and that ∼2.6 million people in the United States obtain drinking water from domestic wells with an elevated Mn content (i.e., exceeding the Environmental Protection Agency health reference level of 0.3 mg Mn/l) (24). Delineating mechanisms beyond HIF1/HIF2-mediated SLC30A10 transcriptional upregulation that control Mn homeostasis should enhance understanding of the biology of Mn-induced motor disease and may contribute toward the development of treatments for this condition. Here, we test our hypothesis using a combination of cell-based and mouse studies and identify NR4A1 (also called Nur77) as an unexpected HIF-dependent repressor of SLC30A10 expression that is fundamental to the control of Mn homeostasis.

Results

Identification of NR4A1 as a Mn-responsive potential repressor of SLC30A10 expression

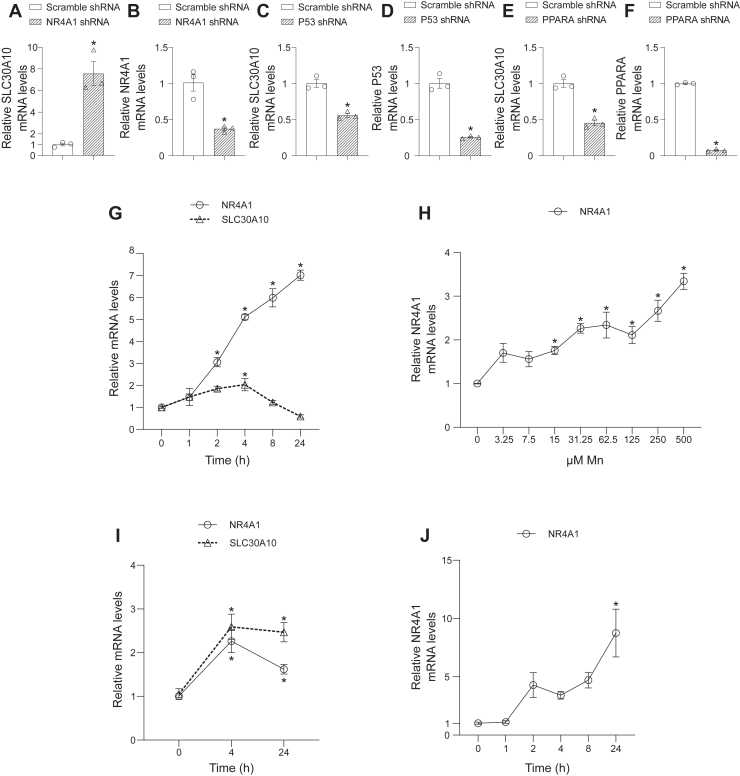

Our recent unbiased transcriptomic analyses identified several transcription factors, in addition to HIF1, as important upstream regulators of Mn-induced gene expression changes in the mouse brain and liver (22). As the first step of the current study, we assayed for the effect of a selection of these non-HIF1 upstream regulators on SLC30A10 gene expression. We used a lentivirus-shRNA system to stably knock down each transcription factor in HepG2 cells and used quantitative real-time PCR (qRT–PCR) to measure SLC30A10 expression. We primarily utilized HepG2 cells for this and most subsequent experiments because our extensive prior analyses characterized HepG2 cells as a pathophysiologically relevant cell model to study Mn homeostasis (4, 5, 22, 25). There was a strong enhancing effect of NR4A1 knockdown on SLC30A10 expression (Fig. 1, A and B), suggesting that NR4A1 may be a repressor of SLC30A10 expression. In contrast, knockdown of the other transcription factors we tested reduced SLC30A10 expression (Fig. 1, C–F), suggesting a more conventional upregulatory role for these transcription factors in modulating SLC30A10 expression. We focused subsequent studies on NR4A1 because (1) NR4A1 knockdown had a stronger effect on SLC30A10 expression than knockdown of other transcription factors we tested (Fig. 1, A–F) and (2) identification of a SLC30A10 repressor was unanticipated but likely of biological significance, as it may function together with direct transcriptional upregulation to establish the level of SLC30A10 expression necessary to restore Mn homeostasis during elevated Mn exposure.

Figure 1.

NR4A1 is aMn-responsive gene that represses SLC30A10 expression.A–F, qRT–PCR analyses in HepG2 cells stably infected with scramble shRNA or shRNA targeting NR4A1 (A & B), p53 (C & D), or PPARA (E & F). For each panel, mean expression in scramble-infected cells was normalized to 1. N = 3. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 by t test. Data points in the graphs are independent biological replicates. G and H, qRT–PCR in HepG2 cells treated with 500 μM Mn for indicated times (G) or indicated concentrations of Mn for 8 h (H). Mean expression without Mn exposure (0 h for G or 0 μM Mn for H) was normalized to 1. N = 3 for G and 4 for H. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 for difference with the no Mn condition for each gene separately by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc test. For H, the extracellular Mn EC50 was calculated using nonlinear regression and log(agonist) versus response (three parameters) with the bottom constrained to 1. I, qRT–PCR in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with 500 μM Mn for indicated times. For each gene, mean expression at 0 h was normalized to 1. N = 9. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 for difference between 0 h and other time points for each gene separately by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc test. J, qRT–PCR in HMC3 cells treated with 500 μM Mn for indicated times. Mean expression at 0 h was normalized to 1. N = 6. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 for difference with the 0 h time point by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post hoc test. Mn, manganese; qRT–PCR, quantitative RT–PCR.

If NR4A1 played a role in Mn homeostasis, it was likely that expression of NR4A1 would be responsive to changes in cellular Mn levels. To test this prediction, we assayed for the effect of Mn treatment on NR4A1 expression. Time-course analyses revealed that Mn treatment robustly increased NR4A1 expression (Fig. 1G). Mn treatment also increased SLC30A10 expression in the same experiment (Fig. 1G). Notably, the kinetics of the Mn-induced increase of NR4A1 and SLC30A10 were different. While SLC30A10 expression peaked at 4 h and returned to baseline by 8 h (Fig. 1G), consistent with our prior study (5), levels of NR4A1 remained markedly elevated even 24 h after Mn exposure (Fig. 1G). The differential temporal response of NR4A1 and SLC30A10 to elevated Mn (Fig. 1G) combined with the repressive effect of NR4A1 on SLC30A10 expression (Fig. 1, A and B) raises the possibility that a Mn-induced increase in NR4A1 may contribute to the restoration of SLC30A10 expression to baseline after the initial Mn-induced upregulation of SLC30A10 expression (see Discussion section). Mn dose–response analyses revealed that the NR4A1 upregulation was highly sensitive to Mn treatment with an extracellular Mn EC50 of ∼20 μM (95% confidence interval: 7.2–48 μM) (Fig. 1H), which is essentially in the same range as the previously reported ∼1 to 10 μM extracellular Mn EC50 for the stabilization of HIF1α and HIF2α protein, upregulation of SLC30A10 mRNA expression, and induction of HIF transcriptional activity (4). Furthermore, we validated that Mn treatment upregulated NR4A1 expression in two other cell lines, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, which are used to model dopaminergic neurons (26), and HMC3 cells that model microglia (27) (Fig. 1, I and J). SLC30A10 was also upregulated after Mn treatment in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1I) although the temporal pattern of SLC30A10 and NR4A1 upregulation in SH-SY5Y cells differed from that in the HepG2 cells (Fig. 1, G and I; HMC3 cells did not express SLC30A10). In totality, results in Figure 1 identify NR4A1 as a Mn-responsive gene in diverse cell models and provide initial evidence for a role for NR4A1 in repressing SLC30A10 expression.

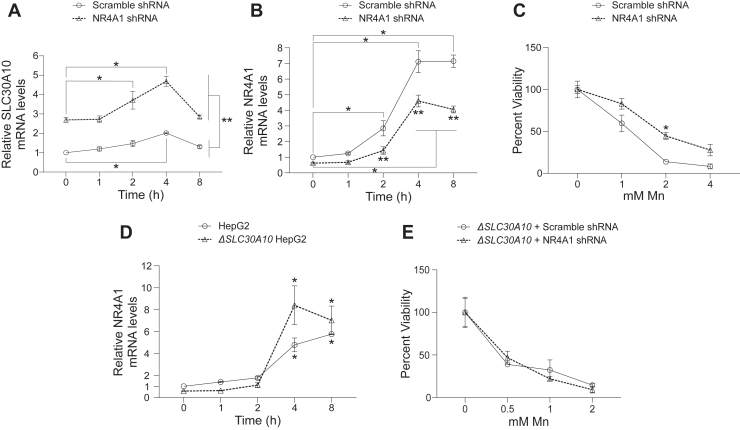

Knockdown of NR4A1 increases SLC30A10 expression and protects against Mn-induced toxicity in a SLC30A10-dependent manner

To more rigorously investigate the relationship between NR4A1 and SLC30A10 expression, we assayed for gene expression after a time course of Mn treatment using NR4A1 or control knockdown HepG2 cells. NR4A1 knockdown enhanced SLC30A10 expression at all time points after Mn treatment but did not alter the overall kinetics of the SLC30A10 response (Fig. 2A). The observed Mn-induced increase in SLC30A10 expression in NR4A1 knockdown cells (Fig. 2A) implies that NR4A1 expression does not impact the HIF1/HIF2-mediated upregulation of SLC30A10 expression. We had expected that depletion of NR4A1 may prolong the Mn-induced upregulation of SLC30A10. The similarity of the temporal pattern of SLC30A10 upregulation followed by restoration to baseline between control or NR4A1 knockdown cells (Fig. 2A), in contrast to our expectations, is likely reflective of the partial depletion of NR4A1 (Fig. 1B) and the robust Mn-induced increase in expression of residual NR4A1 (Fig. 2B) in the knockdown cells. Despite the lack of an effect of NR4A1 knockdown on the kinetics of the Mn-induced SLC30A10 response, the increase in SLC30A10 expression with knockdown of NR4A1 with or without Mn treatment indicates that NR4A1 is a repressor of SLC30A10 expression under basal and elevated Mn exposure conditions.

Figure 2.

NR4A1 knockdown enhances SLC30A10 expression with or without Mn exposure and protects against Mn-induced cell death in aSLC30A10-dependent manner.A and B, qRT–PCR in wildtype HepG2 cells stably infected with scramble shRNA or shRNA targeting NR4A1 and treated with 500 μM Mn for indicated times. Mean expression at 0 h for scramble shRNA–infected cells was normalized to 1. N = 6. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 for indicated comparisons using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. ∗∗p < 0.05 for the comparisons between scramble- or NR4A1-shRNA-infected cells at each time point by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test. C, cell viability in wildtype HepG2 cells infected with scramble shRNA or shRNA targeting NR4A1 16 h after treatment with indicated concentrations of Mn. For each infection condition, viability at 0 mM Mn was independently set to 100. N = 3. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test for differences between infection conditions at each Mn concentration. D, qRT–PCR in wildtype or ΔSLC30A10 HepG2 cells treated with 250 μM Mn for indicated times. Mean expression in wildtype cells was normalized to 1. N = 4. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 for comparisons with the 0 h time point within each infection condition using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. There was also a statistically significant difference between infection conditions (p < 0.05) at the 4 h time point by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test. E, cell viability in ΔSLC30A10 HepG2 cells infected and treated with Mn as described for C. For each infection condition, viability at 0 mM Mn was independently set to 100. N = 3. Mean ± SE. There were no differences between infection conditions at each Mn concentration using two-way ANOVA. Mn, manganese; qRT–PCR, quantitative RT–PCR.

To determine whether the NR4A1-mediated repression of SLC30A10 levels plays a role in controlling Mn homeostasis, we performed metal measurement and cell viability assays in control or NR4A1 knockdown cells. Metal analyses in cells exposed to 125 μM Mn for 16 h revealed that average intracellular Mn, but not Fe, levels of NR4A1 knockdown cells were significantly lower than control (per cell, control knockdown Mn: 136 ± 21 fg; NR4A1 knockdown Mn: 96 ± 7 fg; control knockdown Fe: 41 ± 4 fg; NR4A1 knockdown Fe: 46 ± 13 fg; p < 0.05 between knockdown conditions for Mn but not Fe by t test; mean ± SE; n = 3–6). Knockdown of NR4A1 also protected against cell death induced by elevated Mn exposure (Fig. 2C). These results suggested, but did not definitively establish, that the protective effect of NR4A1 knockdown against Mn toxicity was due to the elevation of SLC30A10 expression in NR4A1 knockdown cells. To establish causality, we needed a system in which SLC30A10 levels could not be upregulated by NR4A1 knockdown. For this, we used a ΔSLC30A10 knockout HepG2 cell line that we previously generated and described (25). Because ΔSLC30A10 cells accumulate more Mn than wildtype HepG2 cells (25), we did not expect that the Mn response of NR4A1 expression would be inhibited in the ΔSLC30A10 knockout cells. But it was still necessary to experimentally confirm this so that interpretation of subsequent assays was not confounded. In a time-course assay, the magnitude of the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 in the ΔSLC30A10 cells was comparable to or stronger than that of wildtype HepG2 cells (Fig. 2D; the enhanced upregulation of NR4A1 at specific time points after Mn exposure in the ΔSLC30A10 cells may relate to the increased accumulation of Mn in these cells (25)). Having established that the Mn responsiveness of NR4A1 was preserved in the ΔSLC30A10 cells, we repeated the NR4A1 knockdown and cell viability assay in the ΔSLC30A10 cells. Importantly, unlike wildtype HepG2 cells (Fig. 2C), knockdown of NR4A1 failed to protect ΔSLC30A10 cells against Mn-induced cell death (Fig. 2E), indicating that the protective effect of NR4A1 knockdown against Mn toxicity was SLC30A10 dependent. Overall, results of Figure 2: (1) indicate that depletion of NR4A1 increases SLC30A10 expression, which reduces sensitivity to Mn toxicity; and (2) combined with those of Figure 1, establish that NR4A1-mediated repression of SLC30A10 expression is an integral component of the homeostatic response to elevated Mn.

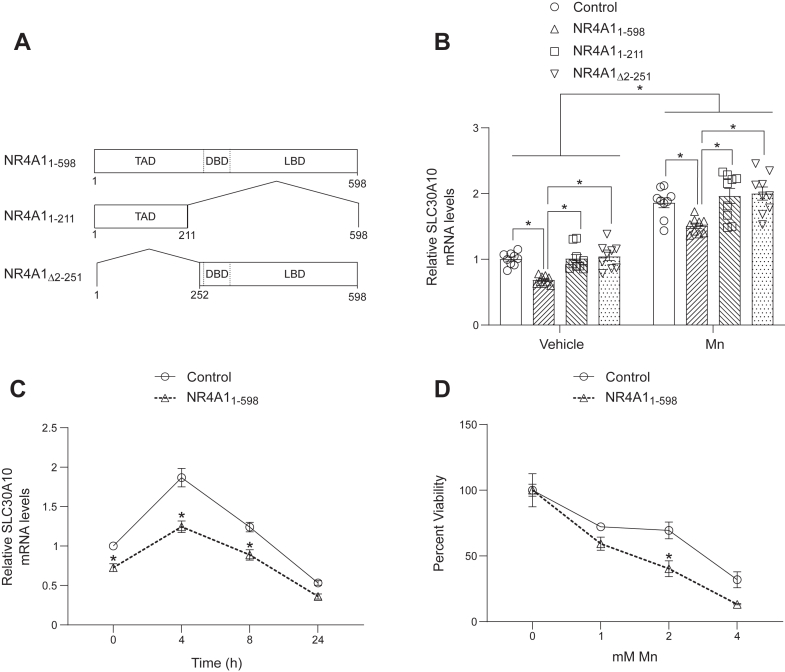

Overexpression of full-length NR4A1 reduces SLC30A10 expression and heightens sensitivity to Mn toxicity

If NR4A1-mediated repression of SLC30A10 expression is critical for controlling Mn homeostasis, the effect of overexpression of NR4A1 on SLC30A10 levels and sensitivity to Mn toxicity should be the opposite of NR4A1 knockdown. To test this prediction, we stably overexpressed full-length NR4A1 (NR4A11–598) or NR4A1 deletion mutants NR4A11–211 or NR4A1Δ2–251 in HepG2 cells (Fig. 3A) and repeated the gene expression and viability assays. NR4A1 has a N-terminal transactivation domain, a middle DNA-binding domain, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (28, 29, 30, 31, 32) (Fig. 3A). NR4A11–211 lacks the DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains (Fig. 3A), NR4A1Δ2–251 lacks the bulk of the transactivation domain (Fig. 3A), and based on prior work (28), both deletion mutants are expected to lack direct transcriptional activity. Consistent with our expectations, overexpression of NR4A11–598 reduced SLC30A10 levels under basal or elevated Mn exposure conditions (Fig. 3, B and C) and enhanced sensitivity to Mn-induced cell death (Fig. 3D). Overexpression of the deletion mutants did not impact SLC30A10 expression (Fig. 3B), indicating that transcriptional activity of NR4A1 was necessary for downstream effects on SLC30A10. The results of the overexpression experiments are (1) consistent with those of the knockdown assays; (2) provide further direct evidence for the role of NR4A1 as a repressor of SLC30A10 expression; and (3) additionally support the conclusion that the repression of SLC30A10 by NR4A1 plays a central role in regulating Mn homeostasis.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of full-length NR4A1 represses SLC30A10 expression and enhances sensitivity to Mn-induced cell death.A, schematic of NR4A1 overexpression constructs. Amino acid numbers and protein domains are indicated. B and C, qRT–PCR in HepG2 cells stably infected with indicated NR4A1 constructs or that underwent control infection (i.e., infection with lentivirus lacking a transfer plasmid) and treated with 0 or 500 μM Mn for 4 h (B) or 500 μM Mn for indicated times (C). Mean expression of control-infected cells without Mn exposure was normalized to 1. N = 9. Mean ± SE. For B, ∗p < 0.05 for indicated comparisons using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test. Also for B, there were no differences between control and NR4A11–211 or NR4A1Δ2–251 groups under vehicle or Mn exposure conditions by two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test (p > 0.05). For C, ∗p < 0.05 for comparisons between infection conditions at each time point using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test. Data points in the graphs are independent biological replicates. D, cell viability was assayed in HepG2 cells infected as indicated 16 h after treatment with indicated concentrations of Mn. For each infection condition, viability at 0 mM Mn was independently set to 100. N = 3. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test for differences between infection conditions at each Mn concentration. DBD, DNA-binding domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; Mn, manganese; qRT–PCR, quantitative RT–PCR; TAD, transactivation domain.

The Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 expression is mediated by HIF2α but not HIF1α

Having established a role for the NR4A1-mediated repression of SLC30A10 in controlling Mn homeostasis, we sought to define the mechanisms underlying the induction of NR4A1 by elevated Mn. We focused on the HIF1/HIF2 pathway because prior evidence indicates that HIF signaling directly upregulates NR4A1 expression via a hypoxia-response element in the NR4A1 promoter (29, 33). In HepG2 cells, knockdown of both HIF1α and HIF2α blocked the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 levels without affecting basal NR4A1 expression (Fig. 4, A–C). We were unable to isolate the specific HIFα isoform (i.e., HIF1α or HIF2α) required for the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 using the knockdown strategy in cells, likely because of partial knockdown of each isoform (Fig. 4, B and C) and possible compensation by the untargeted isoform in the culture system. To circumvent this challenge, we used tissue-specific HIF1α or HIF2α knockout mice that we previously described and that lack expression of the targeted HIFα isoform in the liver (22). Importantly, human-relevant Mn exposure increased NR4A1 levels in the liver of control and HIF1α, but not HIF2α, knockout mice (Fig. 4, D and E). Note that we recently reported qRT–PCR analyses of other genes using the RNA samples utilized in Figure 4, D and E (22), and we validated the knockout specificity of the HIF1α or HIF2α mutant strains in the previous study (22). Therefore, we did not repeat validation assays for knockout specificity in the current study. The knockdown and knockout assays, put together, indicate that HIF2α is required for the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1. Further validation of the specific role of HIF2α in regulating NR4A1 expression came from experiments in which we assayed for the effect of overexpression of VHL-insensitive mouse HIF1α or HIF2α mutant, which we previously described (5) and which should be stable under physiological conditions. Overexpression of the HIF2α, but not the HIF1α, mutant enhanced NR4A1 expression after Mn exposure (Fig. 4F), indicating that HIF2α is sufficient to increase the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 expression. We additionally confirmed that treatment with the PHD2 inhibitor roxadustat, which stabilizes HIF1α and HIF2α protein and increases SLC30A10 expression in the absence of Mn treatment (5), enhanced basal NR4A1 expression (Fig. 4G). The totality of the cell culture and mouse data indicate that the Mn-induced activation of NR4A1 is mediated by HIF2α. As elevated Mn directly activates HIF1/HIF2 signaling (4, 5), these results provide an explanation for the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 levels.

Figure 4.

Elevated Mn upregulates NR4A1 expression in aHIF2-dependent manner.A–C, qRT–PCR analyses in HepG2 cells stably infected with scramble shRNA or shRNAs targeting HIF1α and HIF2α and treated with 0 or 500 μM Mn for 4 h. Mean expression in scramble-infected cells without Mn exposure was normalized to 1. N = 9. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 and ns, not significant for indicated comparisons using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. D and E, qRT–PCR analyses from previously collected liver samples of endoderm-specific HIF1α or HIF2α knockout mice, with knockout of HIF1α or HIF2α in the liver, or their littermate controls treated with an oral Mn regimen (0 or ∼15 mg Mn/kg daily) from PND 1 and euthanized at PND 14. Mean expression in control genotype without Mn exposure was normalized to 1. N = 5 to 6 per group as indicated. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 and ns, not significant for indicated comparisons using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s post hoc test. F, qRT–PCR in HepG2 cells stably infected with VHL-insensitive mouse HIF1α or HIF2α constructs or that were control infected (i.e., infected with lentivirus lacking a transfer plasmid) and treated with 0 or 500 μM Mn for 4 h. Mean expression in control-infected cells without Mn treatment was normalized to 1. N = 9. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 and ns, not significant for indicated comparisons using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. G, qRT–PCR in HepG2 cells treated with 0 or 20 μM roxadustat for 16 h. Mean expression in 0 μM roxadustat-treated cells was normalized to 1. N = 9. Mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05 by t test. Data points in the graphs for all panels are independent biological replicates. Mn, manganese; PND, postnatal day; qRT–PCR, quantitative RT–PCR.

Discussion

We previously established that the primary homeostatic response to elevated Mn in mammalian systems is the activation of HIF1/HIF2 signaling because of the Mn-induced inhibition of PHD2 enzyme and the subsequent direct transcriptional upregulation of SLC30A10 by HIF1/HIF2 (4, 5). Current results show that, in addition to the upregulation of SLC30A10, a second, homeostatically important consequence of the Mn-induced activation of HIF signaling is the induction of NR4A1, which represses SLC30A10 expression. Thus, the molecular control of Mn homeostasis is designed such that a single upstream Mn-induced event (i.e., PHD2 inhibition and HIF1/HIF2 activation) directly upregulates the protective pathway that reduces cellular Mn (i.e., direct transcriptional upregulation of SLC30A10 via HIF1/HIF2) and simultaneously activates a repressive arm to attenuate and/or terminate the protective response (i.e., HIF2-mediated induction of NR4A1, which suppresses SLC30A10 expression).

Repression of SLC30A10 via NR4A1 may prevent the development of Mn deficiency from excessive or prolonged upregulation of SLC30A10 during elevated Mn exposure. Based on our data, a possible model for the control of SLC30A10 expression by the opposing effects of direct HIF1/HIF2-mediated transcriptional upregulation and NR4A1-mediated repression is as follows. NR4A1-mediated repression of SLC30A10 under basal/physiological conditions may contribute to the establishment of the physiological SLC30A10 expression level. At early time points after elevated Mn exposure, the direct upregulatory effect of HIF1/HIF2-mediated increase in SLC30A10 transcription may predominate, leading to the observed increase in SLC30A10 expression, but NR4A1 may still prevent an excessive upregulation of SLC30A10. At later time points after Mn exposure, the HIF2-dependent increase in NR4A1 levels may enhance the repressive effect of NR4A1 on SLC30A10 expression and contribute to the restoration of SLC30A10 levels toward baseline.

The differential pattern of the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 in HepG2 and SH-SY5Y cells suggests that the crosstalk between Mn exposure, HIF signaling, and NR4A1 and SLC30A10 expression is likely cell and tissue specific. The underlying mechanism is unclear, but possibilities include cell-specific differences in Mn accumulation (because of differential expression of SLC30A10 or other Mn transporters), expression or activity of HIF1/HIF2, or transcription of NR4A1.

In this study, we did not investigate the mechanism of repression of SLC30A10 expression by NR4A1. We did not identify a consensus NR4A1 DNA-binding sequence (32) in the SLC30A10 promoter, suggesting that NR4A1 may repress SLC30A10 expression via an indirect mechanism. Possibly, NR4A1 may induce transcription of another protein that acts as a repressor of SLC30A10 expression. Defining this mechanism of repression is an important direction for future research and should clarify how opposing upregulatory and repressive effects coordinately control SLC30A10 expression and Mn homeostasis.

Prior work indicates that there is a bidirectional relationship between HIF signaling and NR4A1 expression, with HIF signaling upregulating NR4A1 transcription via a hypoxia-response element in the NR4A1 promoter (29, 33) (as previously mentioned in the Results section), and NR4A1 protein exerting a nongenomic stabilizing effect on HIFα subunits and upregulating HIF signaling (29, 30, 31). HIF1 was previously identified as the relevant isoform that upregulates NR4A1 transcription (33). In contrast, our work implicates HIF2 as the HIF isoform that mediates the Mn-induced NR4A1 upregulation. Understanding the biological contexts that confer HIFα isoform specificity for NR4A1 upregulation is another important direction for future work (the difference in the specificity of the required HIF isoform between our and the prior work may relate to the difference in the signal that stabilizes HIFα subunits between the studies—that is, elevated Mn in our study and hypoxia and other Mn-independent signals in the prior work (33)). Furthermore, while a nongenomic role for NR4A1 in stabilizing HIFα subunits and enhancing HIF signaling has been reported (29, 30, 31), overexpression of NR4A1 in our study did not enhance the Mn-induced upregulation of SLC30A10, suggesting that any stabilization/activation effect of NR4A1 on HIF signaling may have limited relevance in controlling Mn homeostasis. Determining the pathophysiological conditions under which nongenomic control of HIFα protein by NR4A1 protein gains biological significance is yet another area for future investigation.

In addition to controlling Mn homeostasis, our recent work established a crucial role for HIF signaling in the onset of transcriptomic and metabolic changes that lead to Mn-induced motor disease (22). We reported that (1) Mn exposure in wildtype mice upregulates expression of genes and metabolites of diverse metabolic pathways, including the neurotoxic kynurenine pathway (22); (2) HIF1 is a major driver of the Mn-induced metabolic changes and plays an important role in the optimal expression of important kynurenine pathway genes (22); and (3) inhibition of the kynurenine pathway fully rescues Mn-induced motor disease (22). Separately, we also identified HIF1 as a major upstream regulator of transcriptomic changes in whole-body Slc30a10 knockout mice (21), which develop Mn toxicity without Mn exposure (12, 15, 16). Thus, Mn-induced activation of HIF1/HIF2 signaling is central to both the homeostatic control and neurotoxicity of Mn (4, 5, 21, 22). The exquisite Mn sensitivity of PHD2 inhibition, HIF1α/HIF2α protein stabilization, and SLC30A10 and NR4A1 upregulation (Ref. (4) and this study) suggests that the primary function of the Mn-HIF pathway is likely to rapidly respond to an increase in intracellular Mn and restore homeostasis by altering Mn efflux. In contrast, the metabolic reprogramming that contributes to the neurotoxicity of Mn may be an unavoidable consequence of HIF1/HIF2 activation because HIF signaling is a major regulator of metabolism (20). In the context of the current study, the dependence of the Mn-induced upregulation of NR4A1 on HIF2 further reinforces the fundamental role of HIF signaling in regulating Mn homeostasis. In conclusion, we identify a previously unknown HIF-mediated control mechanism of SLC30A10 expression and Mn homeostasis in mammalian systems.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture

HepG2 and human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured essentially as described previously (4, 22, 25). We previously described the ΔSLC30A10 HepG2 cell line that we generated using CRISPR (25). SH-SY5Y (#CRL-2266) and HMC3 cells (#CRL-3304) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 Nutrient Mixture (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Differentiation medium for SH-SY5Y cells was Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 Nutrient Mixture (1:1) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (reduced serum), 10 μM retinoic acid, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, consistent with prior descriptions (26). Cells were differentiated for 5 days, and experiments were then performed in the differentiation media. HMC3 cells were grown in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (27).

Lentivirus infections

These were performed exactly as described previously (22). For shRNA experiments, controls received lentivirus containing scramble shRNA. For HIF1α and HIF2α double knockdown experiments, cells were sequentially infected with lentivirus targeting HIF1α and HIF2α, and control cells were also sequentially infected with scramble shRNA–containing lentivirus. For gene overexpression experiments, controls received lentivirus without transfer plasmid. Two days after infection, puromycin (2 μg/ml) was added to the media for overexpression, but not shRNA, infections.

Constructs and cloning

shRNA target sequences are provided in Table S1. shRNAs were subcloned into the EcoR1 and Age1 restriction sites of the lentivirus transfer plasmid pLKO.1 (Addgene #8453), which we have previously described (5). For cloning NR4A11–598, a construct coding for the open reading frame of NR4A1 was obtained from DNASU (#HsCD00002281-NR4A1), amplified using forward 5′-GAT CAT GCT AGC ATG CCC TGT ATC CAA G-3′ and reverse 5′-GTA GTC GAA TTC CAA GAA GGG CAG CGT G-3′ primers, ligated into the EcoR1 and Nhe1 restriction sites of the lentivirus transfer plasmid LAMP1-mRFP-FLAG (Addgene #34611), which we have previously described (5, 34), and a stop codon was inserted after the open reading frame of NR4A1 using QuikChange. Deletion mutants NR4A11–211 and NR4A1Δ2–251 were generated from NR4A11–598 using QuikChange. All constructs were validated by sequencing. We have previously described the VHL-insensitive mouse HIF1α and HIF2α constructs (5).

qRT–PCR assays in cell culture

RNA was isolated using the PureLink RNA mini kit (Life Technologies) and reverse transcribed to complementary DNA using qScript Complementary DNA Supermix (Quanta). Real-time PCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) essentially as described previously (22) using primers provided in Table S2. Transcript levels were quantified using the ΔΔCT method using TBP as an internal control as described by us previously (22).

Cell viability assays

Cells were plated at a density of ∼25,000 cells/well in 24-well plates, treated with Mn for 16 h, and viability was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent as we described previously (25).

Metal analyses

For metal measurements in HepG2 cells, for each infection condition, 300,000 cells were plated per well of 6-well plates, treated with 125 μM Mn for 16 h, and processed for generation of cell pellets as described previously (4, 25). Metal levels were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry as described previously (4).

Mn and roxadustat treatment in cells

These were also performed as described previously (5). In brief, Mn was used as MnCl2.4H2O dissolved in water. Vehicle-treated cells received water. Mn concentrations ≤500 μM are not toxic to wildtype HepG2 cells (4, 5, 25). We used a lower range of Mn concentrations in experiments with ΔSLC30A10 HepG2 cells because, compared with wildtype HepG2 cells, the knockout cells exhibit an increase in Mn accumulation and sensitivity to Mn toxicity (25). Roxadustat was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and used at a final concentration of 20 μM. Dimethyl sulfoxide concentration did not exceed 0.1% in vehicle- or roxadustat-treated cells.

qRT–PCR from mouse tissue

Experiments with mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Austin. qRT–PCR analyses for other genes from RNA samples used in this work were previously reported (22), and these RNA samples were used to assess NR4A1 expression using primers provided in Table S2. Details about mouse strains, husbandry, genotyping, Mn exposure, euthanasia, and tissue processing and analyses for qRT–PCR are provided in the prior publication (22). Isoform and tissue specificity of knockout of HIF1α or HIF2α were confirmed in the prior study (22). To briefly summarize key details provided in Ref. (22): we used endoderm-specific HIF1α or HIF2α knockout mice, which induces knockout in the liver and other endoderm-derived tissue, generated by crossing floxed HIF1α or HIF2α mice with Foxa3-Cre mice; littermates were used as genotype controls; mice were exposed to daily oral vehicle or Mn (0 or ∼50 mg MnCl2.4H2O/kg, which amounts to ∼15 mg absolute Mn/kg) starting from postnatal day 1 (this regimen models environmental Mn exposure in humans); mice were euthanized on postnatal day 14 and tissue harvested for analyses (22).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

All data are contained in the article and supporting information.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

N. R. H. and S. M. conceptualization; S. M. validation; S. M. formal analysis; N. R. H., Y. R. L., N. S., and T. J. investigation; S. M. writing–original draft; N. R. H., D. R. S., and S. M. writing–review & editing; N. R. H. visualization; S. M. supervision; S. M. project administration; S. M. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

Supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences R01-ES024812 and R01-ES031574 (both to S. M.).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Elizabeth J. Coulson

Supporting information

References

- 1.Nemeth E., Tuttle M.S., Powelson J., Vaughn M.B., Donovan A., Ward D.M., et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306:2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaefer M., Hopkins R.G., Failla M.L., Gitlin J.D. Hepatocyte-specific localization and copper-dependent trafficking of the Wilson's disease protein in the liver. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:G639–G646. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langmade S.J., Ravindra R., Daniels P.J., Andrews G.K. The transcription factor MTF-1 mediates metal regulation of the mouse ZnT1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:34803–34809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurol K.C., Jursa T., Cho E.J., Fast W., Dalby K.N., Smith D.R., et al. PHD2 enzyme is an intracellular manganese sensor that initiates the homeostatic response against elevated manganese. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024;121 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2402538121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C., Jursa T., Aschner M., Smith D.R., Mukhopadhyay S. Up-regulation of the manganese transporter SLC30A10 by hypoxia-inducible factors defines a homeostatic response to manganese toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107673118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majmundar A.J., Wong W.J., Simon M.C. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong G.H., Takeda K. Role and regulation of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:635–641. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balachandran R.C., Mukhopadhyay S., McBride D., Veevers J., Harrison F.E., Aschner M., et al. Brain manganese and the balance between essential roles and neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:6312–6329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.009453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchens S., Jursa T.P., Melkote A., Grant S.M., Smith D.R., Mukhopadhyay S. Hepatic and intestinal manganese excretion are both required to regulate brain manganese during elevated manganese exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2023;325:G251–G264. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00047.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyva-Illades D., Chen P., Zogzas C.E., Hutchens S., Mercado J.M., Swaim C.D., et al. SLC30A10 is a cell surface-localized manganese efflux transporter, and parkinsonism-causing mutations block its intracellular trafficking and efflux activity. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:14079–14095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2329-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor C.A., Grant S.M., Jursa T., Melkote A., Fulthorpe R., Aschner M., et al. SLC30A10 manganese transporter in the brain protects against deficits in motor function and dopaminergic neurotransmission under physiological conditions. Metallomics. 2023;15 doi: 10.1093/mtomcs/mfad021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor C.A., Hutchens S., Liu C., Jursa T., Shawlot W., Aschner M., et al. SLC30A10 transporter in the digestive system regulates brain manganese under basal conditions while brain SLC30A10 protects against neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:1860–1876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zogzas C.E., Aschner M., Mukhopadhyay S. Structural elements in the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the metal transporter SLC30A10 are required for its manganese efflux activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:15940–15957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.726935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurol K.C., Aschner M., Smith D.R., Mukhopadhyay S. Role of excretion in manganese homeostasis and neurotoxicity: a historical perspective. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2022;322:G79–G92. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00299.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchens S., Liu C., Jursa T., Shawlot W., Chaffee B.K., Yin W., et al. Deficiency in the manganese efflux transporter SLC30A10 induces severe hypothyroidism in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:9760–9773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.783605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C., Hutchens S., Jursa T., Shawlot W., Polishchuk E.V., Polishchuk R.S., et al. Hypothyroidism induced by loss of the manganese efflux transporter SLC30A10 may be explained by reduced thyroxine production. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:16605–16615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.804989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor C.A., Tuschl K., Nicolai M.M., Bornhorst J., Gubert P., Varao A.M., et al. Maintaining translational relevance in animal models of manganese neurotoxicity. J. Nutr. 2020;150:1360–1369. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuschl K., Clayton P.T., Gospe S.M., Jr., Gulab S., Ibrahim S., Singhi P., et al. Syndrome of hepatic cirrhosis, dystonia, polycythemia, and hypermanganesemia caused by mutations in SLC30A10, a manganese transporter in man. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quadri M, Federico A, Zhao T, Breedveld GJ, Battisti C, Delnooz C, et al. Mutations in SLC30A10 cause parkinsonism and dystonia with hypermanganesemia, polycythemia, and chronic liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dengler V.L., Galbraith M., Espinosa J.M. Transcriptional regulation by hypoxia inducible factors. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014;49:1–15. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.838205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warden A., Mayfield R.D., Gurol K.C., Hutchens S., Liu C., Mukhopadhyay S. Loss of SLC30A10 manganese transporter alters expression of neurotransmission genes and activates hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in mice. Metallomics. 2024;16 doi: 10.1093/mtomcs/mfae007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warden A.S., Sharma N., Hutchens S., Liu C., Haggerty N.R., Gurol K.C., et al. Elevated brain manganese induces motor disease by upregulating the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2025;122 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2423628122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Racette B.A., Criswell S.R., Lundin J.I., Hobson A., Seixas N., Kotzbauer P.T., et al. Increased risk of parkinsonism associated with welding exposure. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:1356–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMahon P.B., Belitz K., Reddy J.E., Johnson T.D. Elevated manganese concentrations in United States groundwater, role of land surface-soil-aquifer connections. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:29–38. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b04055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurol K.C., Li D., Broberg K., Mukhopadhyay S. Manganese efflux transporter SLC30A10 missense polymorphism T95I associated with liver injury retains manganese efflux activity. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2023;324:G78–G88. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00213.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xicoy H., Wieringa B., Martens G.J. The SH-SY5Y cell line in Parkinson's disease research: a systematic review. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12:10. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dello Russo C., Cappoli N., Coletta I., Mezzogori D., Paciello F., Pozzoli G., et al. The human microglial HMC3 cell line: where do we stand? A systematic literature review. J. Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:259. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1288-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulsen R.E., Weaver C.A., Fahrner T.J., Milbrandt J. Domains regulating transcriptional activity of the inducible orphan receptor NGFI-B. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:16491–16496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoo Y.G., Yeo M.G., Kim D.K., Park H., Lee M.O. Novel function of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 in stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53365–53373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenis D.S., Medzikovic L., Vos M., Beldman T.J., van Loenen P.B., van Tiel C.M., et al. Nur77 variants solely comprising the amino-terminal domain activate hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and affect bone marrow homeostasis in mice and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:15070–15083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim B.Y., Kim H., Cho E.J., Youn H.D. Nur77 upregulates HIF-alpha by inhibiting pVHL-mediated degradation. Exp. Mol. Med. 2008;40:71–83. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winoto A. Genes involved in T-cell receptor-mediated apoptosis of thymocytes and T-cell hybridomas. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:51–58. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi J.W., Park S.C., Kang G.H., Liu J.O., Youn H.D. Nur77 activated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha overproduces proopiomelanocortin in von Hippel-Lindau-mutated renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:35–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zogzas C.E., Mukhopadhyay S. Putative metal binding site in the transmembrane domain of the manganese transporter SLC30A10 is different from that of related zinc transporters. Metallomics. 2018;10:1053–1064. doi: 10.1039/c8mt00115d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained in the article and supporting information.