ABSTRACT

Condensins are large protein complexes that play a central role in mitotic chromosome assembly in eukaryotes. Our previous mutational analyses of condensin I, combined with Xenopus egg cell‐free extracts, provided evidence that dynamic condensin‐condensin interactions, triggered by a contact between the CAP‐D2 and SMC4 subunits, underlie proper chromosome assembly and shaping. To examine whether and how the hypothesized condensin‐condensin interactions contribute to chromosome assembly, here we employed a rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB dimerization system to artificially tether CAP‐D2 and SMC4 either between different complexes (inter‐complex tethering) or within single complexes (intra‐complex tethering). The ability of the resulting complexes to assemble mitotic chromosomes was then assessed in Xenopus egg extracts. We found that inter‐complex tethering enhances condensin I loading and facilitates mitotic chromosome assembly, whereas intra‐complex tethering restricts its function. Moreover, deficiencies in the D2‐SMC4 contact caused by an SMC4 W‐loop mutation were partially compensated by inter‐complex tethering. Together, these findings provide direct evidence that condensin‐condensin interactions facilitate mitotic chromosome assembly.

Keywords: chromosome assembly, condensins, loop extrusion, mitosis, SMC ATPase, Xenopus egg extracts

By using a rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB tethering system to directly manipulate the action of recombinant condensin I complexes in Xenopus egg extracts, we demonstrate that inter‐complex tethering (in trans) enhances condensin I loading and facilitates mitotic chromosome assembly, whereas intra‐complex tethering (in cis) restricts its function.

1. Introduction

The assembly of mitotic chromosomes is a fundamental process that ensures the faithful segregation of genomic DNA into daughter cells in all eukaryotic species. Since the aesthetic descriptions by Walther Flemming in the late 19th century, this visually striking process has continued to fascinate cell biologists for more than 130 years (Flemming 1882). Despite recent progress in identifying the key components responsible for this process, the mechanistic basis of how these factors act and cooperate to assemble rod‐shaped chromosomes remains incompletely understood (Paulson et al. 2021; Hirano 2025).

It is well established that condensin complexes are the central players in mitotic chromosome assembly (Hirano 2016). Many eukaryotes possess two distinct condensin complexes, condensin I and condensin II, which share the core SMC (structural maintenance of chromosome) ATPase subunits, SMC2 and SMC4. Each condensin complex contains a unique set of non‐SMC subunits: a kleisin (CAP‐H for condensin I; CAP‐H2 for condensin II) and two HEAT‐repeat subunits (CAP‐D2 and CAP‐G for condensin I; CAP‐D3 and CAP‐G2 for condensin II). The mechanisms by which this class of elaborate molecular machines fold chromatin fibers to assemble chromosomes are under active investigation. Over the past decade, the “loop extrusion” model has emerged as a leading hypothesis for the fundamental principle of mitotic chromosome organization (Alipour and Marko 2012; Goloborodko et al. 2016). In this model, SMC protein complexes act as DNA loop extruders, initially generating a small loop from double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA) and then enlarging it by sliding toward the base of the loop. Single‐molecule imaging analyses have provided experimental support for this model, demonstrating that yeast and human condensin complexes can extrude DNA loops in an ATP‐dependent manner in vitro (Ganji et al. 2018; Kong et al. 2020). Despite these remarkable advances, however, whether loop extrusion alone is sufficient to assemble mitotic chromosomes under physiological conditions remains an open question.

Beyond the loop extrusion mechanism, alternative or additional models have been proposed to explain how condensins drive higher‐order chromosome organization (Forte et al. 2025; Hirano and Kinoshita 2025; Uhlmann 2025). For example, mathematical modeling and computer simulations suggest that condensin–condensin interactions can accelerate mitotic chromosome assembly (Sakai et al. 2018; Yamamoto et al. 2023), and that “bridging‐induced attraction,” in which condensins form multivalent bridges between chromatin loops, promotes robust compaction (Forte et al. 2024). Inspired by structural studies that revealed a physical contact between the SMC4 W‐loop and the CAP‐D2 KG‐loop (Hassler et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2020), our previous study combining mutational analyses of condensin I with Xenopus egg extracts provided evidence that this D2–SMC4 contact acts as a trigger for condensin–condensin interactions between distinct complexes, thereby contributing to condensin I‐mediated chromosome assembly (Kinoshita et al. 2022).

In the present study, to further explore the hypothesized condensin‐condensin interactions, we introduced a rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB dimerization system, widely used for artificially tethering proteins in diverse systems (Banaszynski et al. 2005; Ballister et al. 2014; Sakata et al. 2021), into recombinant condensin I complexes to manipulate their function. Our results demonstrate that inter‐complex tethering exerts a positive effect on condensin I function, whereas intra‐complex tethering exerts a negative effect. Moreover, deficiencies in the D2‐SMC4 contact can be partially compensated by inter‐complex tethering. Taken together, this artificial tethering approach provides direct evidence that condensin‐condensin interactions facilitate mitotic chromosome assembly in Xenopus egg extracts.

2. Results

2.1. Introduction of a Rapamycin‐Inducible FKBP‐FRB Dimerization System to Manipulate the Action of Condensin I

Our previous studies using mutational analyses of the recombinant condensin I complexes in combination with Xenopus egg cell‐free extracts, provided evidence that dynamic condensin‐condensin interactions, triggered by D2‐SMC4 contact, underlie proper chromosome assembly and shaping (Kinoshita et al. 2022). We reasoned that, if condensin‐condensin interactions indeed contribute to mitotic chromosome assembly, artificial tethering of CAP‐D2 and SMC4 using a rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB dimerization system might alter the functional properties of condensin I. To test this idea, we fused a 3HA‐FKBP tag to the N‐terminus of SMC4, and an FRB‐3FLAG tag to the C‐terminus of CAP‐D2 (Figure 1A). In addition, TEV cleavage sites were inserted between the tags and the subunits, enabling removal of the tags by protease treatment. Either construct was co‐expressed with the remaining four subunits using a previously described baculovirus expression system (Kinoshita et al. 2022), thereby reconstituting five‐subunit holocomplexes (Figure 1B). The resulting holocomplexes, holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB), were used for inter‐complex tethering (in trans). Alternatively, FKBP‐SMC4 and D2‐FRB were co‐expressed with the remaining three subunits, yielding holo(FKBP‐SMC4/D2‐FRB), which enabled intra‐complex tethering (in cis). The subunit composition of the purified complexes is shown in Figure 1C.

FIGURE 1.

Introduction of a rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB dimerization system to manipulate the action of condensin I. (A) Tagging strategy for condensin subunits. 3HA and FKBP tags were fused to the N‐terminus of the SMC4 subunit, whereas 3FLAG and FRB tags were fused to the C‐terminus of the CAP‐D2 subunit (left). TEV protease cleavage sites were inserted between FKBP and SMC4 and between CAP‐D2 and FRB. A schematic representation of dimerized FKBP‐FRB is shown on the right. (B) The combination of holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB) was used to induce inter‐complex tethering (in trans), whereas holo(FKBP‐SMC4/D2‐FRB) was used to induce intra‐complex tethering (in cis). In principle, it is possible that the complex designed for intra‐complex tethering (in cis) could also engage in inter‐complex tethering (in trans). However, this possibility is expected to be considerably lower than that of intra‐complex tethering, given the close proximity of the tetherable subunits within a single complex. See also the contrasting results shown below. (C) The wild‐type (WT) and FKBP/FRB‐tagged holocomplexes were purified and subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by CBB staining. (D) Schematic illustration of co‐immunoprecipitation (IP) of FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes. The 3HA tag fused to FKBP‐SMC4 enabled IP of holo(FKBP‐SMC4) with anti‐HA antibody (Ab) beads, whereas the 3FLAG tag fused to CAP‐D2‐FRB allowed detection of holo(D2‐FRB) as the co‐immunoprecipitated complex. (E) Immunoblot of the co‐IP experiment. Holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB) were incubated in the absence or presence of rapamycin to induce tethering and then subjected to IP with anti‐HA Ab. The precipitated bead samples were subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (F) Diagram of the co‐IP experiment for cleaved tags from the complexes. Two complexes for inter‐tethering were incubated with rapamycin at 4°C for 60 min and with TEV protease at 22°C for 60 min, and then subjected to IP with anti‐HA Ab. (G) Immunoblot of the co‐IP for cleaved 3HA‐FKBP and FRB‐3FLAG tags. The precipitated bead samples treated as described in (F) were subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies (input [ipt]; beads [b]).

We first tested whether holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB) could be tethered in a rapamycin‐dependent manner. To this end, the two complexes were mixed in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of rapamycin and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti‐HA antibody beads (Figure 1D). As expected, holo(D2‐FRB) was co‐precipitated with holo(FKBP‐SMC4) in a rapamycin dose‐dependent manner (Figure 1E). The efficiency of co‐precipitation between the two complexes was estimated to be ~50%, based on quantification of the FRB‐3FLAG tag signals derived from the co‐precipitated holo(D2‐FRB) (Figure 1E). This suggests that tethering occurred in approximately half, rather than all, of the complexes. In the case of holo(FKBP‐SMC4/D2‐FRB), which contained both 3HA and 3FLAG tags within a single complex, the same co‐IP approach could not be used to detect FKBP‐FRB dimerization. We therefore devised an alternative co‐IP protocol to monitor inter‐tag tethering after protease cleavage (Figure 1F). In this protocol, the complex was first incubated in the absence or presence of rapamycin, and then treated with TEV protease. The mixtures were subjected to IP using anti‐HA antibody beads to pull down the cleaved 3HA‐FKBP tag (Figure 1F). We confirmed that the cleaved FRB‐3FLAG tag was co‐precipitated with the 3HA‐FKBP tag in holo(FKBP‐SMC4/D2‐FRB) after treatment with rapamycin and TEV protease (Figure 1G). Thus, these results demonstrate that the rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB dimerization system can be applied to both inter‐ and intra‐complex tethering of recombinant condensin I complexes.

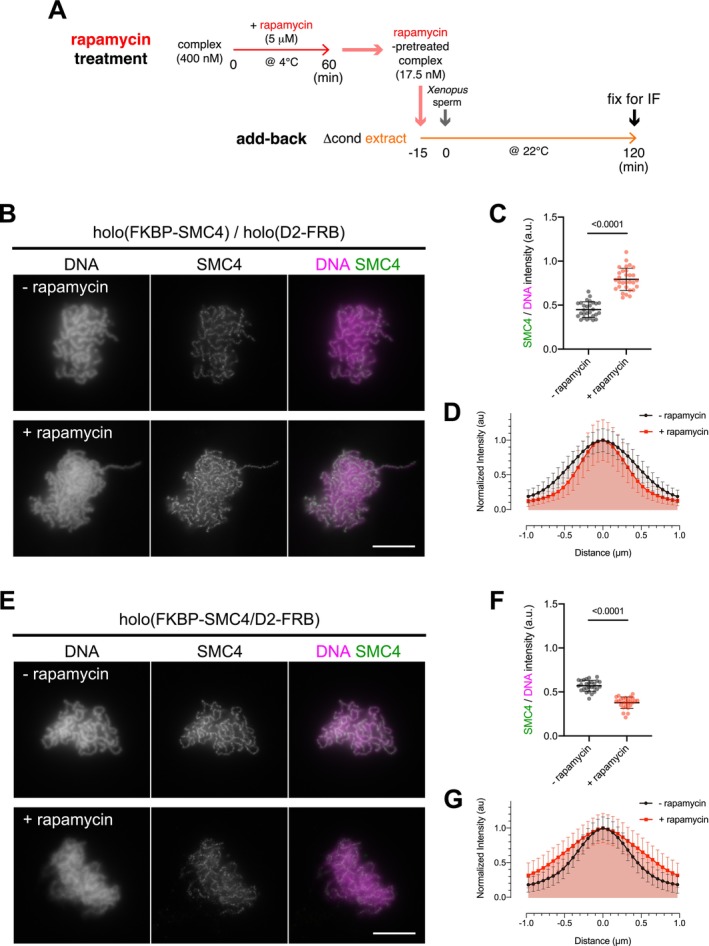

2.2. Inter‐ and Intra‐Complex Tethering Differentially Modulate Condensin I Function

To examine whether, and how, inter‐ and intra‐complex tethering affect the function of condensin I during chromosome assembly, we performed an add‐back assay in Xenopus egg extracts (Kinoshita et al. 2015, 2022). In this experimental setup, FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes were preincubated with rapamycin to induce tethering and then incubated with extracts depleted of endogenous condensins (Δcond). Xenopus sperm nuclei were subsequently added to the mixtures to initiate mitotic chromosome assembly (Figure 2A). We first tested the functional consequence of inter‐complex tethering using a combination of holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB). Complexes without rapamycin pretreatment supported the normal assembly of clustered single‐chromatid chromosomes that were positive for SMC4 signals. Remarkably, rapamycin‐pretreated complexes not only assembled chromosomes (Figure 2B) but also exhibited stronger SMC4 signals on chromosomes compared with control samples (Figure 2C). The resulting chromosomes appeared thinner in the presence of rapamycin (Figure 2D), consistent with the idea that hyperloading of condensin I promotes the formation of elongated chromosomes with shorter loops (Tane et al. 2022). We next tested the effect of intra‐complex tethering using holo(FKBP‐SMC4/D2‐FRB) in the same add‐back assay. In sharp contrast to inter‐complex tethering, rapamycin pretreatment of this complex severely impaired chromosome assembly (Figure 2E), most likely due to inefficient loading, as evidenced by reduced SMC4 signals compared with control samples (Figure 2F). Consequently, the resulting chromosomes appeared thicker than those in the controls (Figure 2G). Thus, inter‐ and intra‐complex tethering have opposing effects on condensin I loading and mitotic chromosome assembly, being positive and negative, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Inter‐ and intra‐complex tethering differentially modulate condensin I function. (A) Diagram of the add‐back assay using rapamycin‐pretreated complexes in Xenopus egg extracts. FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes were mixed with rapamycin to induce tethering at 4°C for 60 min. Rapamycin‐treated complexes were preincubated with condensin‐depleted extracts (Δcond) at 22°C for 15 min to allow mitosis‐specific modification. Following the addition of Xenopus sperm nuclei, the mixture was further incubated at 22°C for 120 min to assemble chromosomes. The reaction mixtures were then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence analyses. (B) Immunofluorescence images of samples from the add‐back assay with rapamycin‐pretreated complexes for inter‐complex tethering. Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Data from a representative experiment (out of three repeats) are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity (SMC4 signal intensity relative to DNA signal intensity) from the experiment shown in (B). The mean and SD are shown (n = 28, 30 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D) Line profiles of chromosomes. DNA signal intensities from chromosomes assembled in the experiment shown in (B) were scanned along lines drawn perpendicular to the chromosome axes (n = 20). The mean and standard deviation of the 20 profiles are plotted as normalized intensities. (E) Immunofluorescence images of samples from the add‐back assay with rapamycin‐pretreated complex for intra‐complex tethering. Fixed samples were analyzed as described in (B). Data from a representative experiment (out of three repeats) are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity from the experiment shown in (E). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 27, 26 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (G) Line profiles of chromosomes assembled in the experiment shown in (E). DNA signal intensities were scanned and are plotted as described in (D) (n = 20).

2.3. Proteolytic Cleavage of the FKBP and FRB Tags Abolishes the Functional Effects of Inter‐Complex Tethering

To verify that the contrasting effects of inter‐ and intra‐tethering of condensin I complexes on mitotic chromosome assembly result from the intended FKBP‐FRB dimerization, we tested whether proteolytic cleavage of the FKBP and FRB tags abolishes these effects (Figure 3A). To this end, we first performed a pilot experiment to determine conditions for near‐complete tag removal from pre‐tethered complexes using TEV protease (Figure S1A,B). We further confirmed that rapamycin did not interfere with efficient cleavage when added together with TEV protease (Figure S1C,D). We found that pretreating holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB) with rapamycin together with TEV protease abolished the positive effects observed with rapamycin alone in Xenopus egg extracts (Figure 3B,C). Likewise, pretreatment of holo(FKBP‐SMC4/D2‐FRB) with rapamycin and TEV protease reversed the detrimental effect of rapamycin alone (Figure 3D,E). Unexpectedly, we also observed increased loading of TEV‐treated complexes compared with control complexes in both experimental setups (Figure 3C,E). We speculate that tagging with FKBP and/or FRB may itself marginally interfere with condensin I activity, and that TEV‐mediated cleavage of the tags releases the complex from this negative influence. In any case, the add‐back assays using TEV protease demonstrate convincingly that rapamycin‐induced FKBP‐FRB dimerization alters the functional properties of condensin I, positively through inter‐complex tethering and negatively through intra‐complex tethering.

FIGURE 3.

Proteolytic cleavage of the FKBP/FRB tags abolishes the effects of dimerization. (A) Diagram of the add‐back assay using rapamycin and TEV protease‐pretreated complexes in Xenopus egg extracts. FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes were mixed with rapamycin and/or TEV protease at 22°C for 60 min. The treated complexes were preincubated with condensin‐depleted extracts (Δcond) at 22°C for 15 min, after which Xenopus sperm nuclei were added and incubated at 22°C for another 120 min to assemble chromosomes. Reaction mixtures were subsequently fixed and processed for immunofluorescence analyses. (B) Immunofluorescence images from the experiment described in (A), in which inter‐complex tethering was tested. Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity from the experiment shown in (B). The mean and SD are shown (n = 29, 29, 34, 32 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D) Immunofluorescence images from the experiment described in (A), in which intra‐complex tethering was tested. Fixed samples were analyzed as described in (B). Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity from the experiment shown in (D). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 34, 36, 33, 30 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

2.4. Inter‐Tethered Complexes Preferentially Load Onto Chromosomes Compared With Coexisting Untethered Complexes

Because the tethering efficiency was estimated to be ~50% in the co‐IP experiment (Figure 1E), untethered complexes coexisted with tethered complexes in the inter‐complex tethering assays (Figure 2B–D). We therefore considered two possible scenarios. First, inter‐tethered complexes may intrinsically acquire higher loading activity than untethered complexes. Second, loading of a small fraction of inter‐tethered complexes onto chromosomes may actively recruit untethered complexes, thereby resulting in overall hyperloading of condensin I. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we mixed inter‐tetherable complexes with a differentially labeled non‐tetherable complex and compared their loading efficiencies in Xenopus egg extracts. Inter‐tetherable complexes were labeled by fusing EGFP to the CAP‐H subunit, generating holo(FKBP‐SMC4)EGFP and holo(D2‐FRB)EGFP, whereas a non‐tetherable wild‐type (WT) holocomplex was labeled by fusing mCherry, yielding holo(WT)mCherry. After pretreating holo(FKBP‐SMC4)EGFP and holo(D2‐FRB)EGFP with rapamycin to induce inter‐complex tethering, we mixed them with holo(WT)mCherry at a 1:1 ratio and added the mixture to Xenopus egg Δcond extracts to assemble mitotic chromosomes (Figure 4A). The samples were fixed at 30 min and 120 min to represent the early and late stages of chromosome assembly, respectively. As expected, stronger EGFP signals from holo(FKBP‐SMC4)EGFP and holo(D2‐FRB)EGFP were detected in the rapamycin‐treated mixtures than in untreated controls at both early and late stages (Figure 4B,C). In contrast, mCherry signals from the non‐tetherable WT complex showed no significant difference between rapamycin‐treated and untreated samples. In this setup, chromosome structures were more clearly observed at 30 min in the presence of rapamycin than in its absence (Figure 4B, top), as reflected by the increased compaction index, defined as the average DNA intensity per unit area (Figure 4D). These results demonstrate that inter‐tethered complexes load onto chromosomes more efficiently than untethered complexes, thereby facilitating mitotic chromosome assembly.

FIGURE 4.

Inter‐tethered complexes via D2‐SMC4 preferentially load onto chromosomes compared with coexisting untethered complexes. (A) Diagram of the add‐back assay using EGFP‐tagged inter‐tetherable complexes and a single mCherry‐tagged non‐tetherable complex. A mixture of EGFP‐tagged inter‐tetherable complexes, pretreated with rapamycin, and the mCherry‐tagged non‐tetherable complex was used for the add‐back assay. Samples were fixed after 30 or 120 min of incubation for immunofluorescence analysis. (B) Immunofluorescence images from the experiment described in (A). The fixed samples were labeled with antibodies against GFP and mCherry. Different relative exposure times were used wherever indicated (0.5×). DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of immunofluorescence signal intensity per unit area from the experiment shown in (B). The mean and SD are shown (n = 34 for −rapamycin and 34 for +rapamycin at 30 min; n = 35 for −rapamycin and 30 for +rapamycin at 120 min). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test. (D) Quantification of the compaction index (the ratio of DNA intensity to DNA‐positive area) from the experiment shown at 30 min in (B). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 34, 34 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

2.5. Inter‐Complex Tethering Lowers the Amount of Condensin I Required for Chromosome Assembly

We next asked to what extent inter‐complex tethering enhances the ability of condensin I to assemble mitotic chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. To this end, we titrated the complex concentrations downward from the standard concentration of 17.5 nM, both in the absence and presence of rapamycin (Figure 5A). We found that holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB) pretreated with rapamycin exhibited higher loading efficiency than untreated complexes, even at concentrations as low as 7.0 nM (Figure 5B). Differences in chromosome morphology between rapamycin‐treated and untreated samples were most evident at 2.8 nM, as reflected by the compaction index (Figure 5C), although differences in chromosomal SMC4 signals were not detectable at this concentration (Figure 5A,B). These results suggest that inter‐complex tethering markedly reduces the amount of condensin I required for proper chromosome assembly.

FIGURE 5.

Inter‐complex tethering lowers the amount of condensin I required for chromosome assembly. (A) Titration experiment of rapamycin‐pretreated complexes for inter‐complex tethering. The add‐back assay was performed with the indicated concentrations of rapamycin‐pretreated holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity from the experiment shown in (A). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 24, 39, 36, 32 for −rapamycin; n = 35, 35, 38 +rapamycin from left to right). (C) Quantification of the compaction index (the ratio of DNA intensity to DNA‐positive area) in the structures shown at 2.8 nM in (A). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 39, 35 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

2.6. Inter‐Complex Tethering Partially Compensates for the D2‐SMC4 Deficiency of Mutant Complexes

Our previous study showed that a mutation in the W‐loop of SMC4 (W1183A substitution), which impairs D2‐SMC4 contact and causes lethality in yeast cells (Hassler et al. 2019), severely compromises the ability of condensin I to assemble chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts (Kinoshita et al. 2022). We next asked what would happen if the corresponding mutant complexes were artificially tethered by the rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB dimerization system. To this end, we introduced the SMC4 W‐loop mutation into the inter‐tetherable complexes, generating holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) and holo(SMC4W1183A/D2‐FRB) (Figure 6A–C). As expected, each mutant complex, regardless of rapamycin pretreatment, exhibited poor chromosomal loading and failed to support chromosome assembly in the add‐back assay (Figure 6D). We next combined holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) and holo(SMC4W1183A/D2‐FRB) and pretreated them in the absence or presence of rapamycin. Strikingly, rapamycin‐treated complexes, but not untreated ones, produced chromosome axis‐like structures with ~1.5‐fold stronger SMC4 signals (Figure 6E,F). These results suggest that inter‐complex tethering partially compensates for the deficiency in D2‐SMC4 contact in the SMC4 W‐loop mutant complexes.

FIGURE 6.

Inter‐complex tethering partially compensates for the D2‐SMC4 contact deficiency of mutant complexes. (A) Schematic representation of the W‐loop mutation (W1183A) introduced into the FKBP‐tagged SMC4 subunit of recombinant condensin I complexes. (B) Schematic illustration of the combination of SMC4 W‐loop mutant complexes for inter‐complex tethering. (C) The untagged and FKBP/FRB‐tagged holocomplexes harboring the W1183A mutation in SMC4 were purified and subjected to SDS‐PAGE. The gel was stained with CBB. (D) Add‐back assay with holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) or holo(SMC4W1183A/D2‐FRB). Each single complex was pretreated with rapamycin and then analyzed in the add‐back assay (17.5 nM). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Add‐back assay with the mixture of holo(FKBP‐SMC4 W1183A) and holo(SMC4W1183A/D2‐FRB). The mixture of holo(FKBP‐SMC4) and holo(D2‐FRB) was pretreated with rapamycin and then analyzed in the add‐back assay (17.5 nM each; 35 nM total). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity from the experiment shown in (E). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 40, 40 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

Finally, we asked what would happen if the mutant complex, holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A), was tethered with a WT complex, holo(D2‐FRB) (Figure S2A,B). We found that this combination also enhanced condensin I loading in the presence of rapamycin (Figure S2C–E), suggesting that the deficiency in D2‐SMC4 contact can be functionally compensated by tethering with a WT complex.

3. Discussion

In the present study, we applied a rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB tethering system to recombinant condensin I complexes and demonstrated that inter‐ and intra‐complex tethering differentially modulate condensin I function during mitotic chromosome assembly. Our analyses demonstrate that inter‐complex tethering enhances condensin I loading and facilitates chromosome assembly, whereas intra‐complex tethering restricts condensin I function (Figure 7A). We propose that the artificial inter‐complex tethering introduced here partially mimics condensin‐condensin interactions that occur on chromosomes under normal conditions, representing a productive mode of the cooperative action of condensin I (Figure 7A, right). In contrast, intra‐complex tethering is likely to compromise conformational changes of condensin I coupled to its ATPase cycle, which are required for its individual actions, including DNA engagement and subsequent loop extrusion (Figure 7A, left). In addition, intra‐complex tethering may interfere with proper condensin‐condensin interactions. It should be noted that tethering efficiency reaches only ~50% under the current conditions, suggesting that the observed functional impacts likely underestimate the full potential of this approach.

FIGURE 7.

Models. (A) Differential effects of inter‐ and intra‐complex tethering in mitotic chromosome assembly. In the early stage of chromosome assembly, the ATP‐dependent loop extrusion mechanism generates small DNA loops and expands them to form larger ones. This process primarily depends on the individual actions of condensin complexes. Intra‐complex tethering (in cis) interferes with the conformational changes of condensin I coupled to the SMC ATPase cycle, thereby restricting its loading onto chromosomes. Intra‐complex tethering may also exert negative effects on the condensin‐condensin interactions. We hypothesize that condensin‐condensin interactions facilitate mitotic chromosome assembly at the later stage by stabilizing chromosome axis structures. Inter‐complex tethering (in trans) may partially mimic the process occurring under crowded conditions, thereby facilitating chromosome assembly and stabilization. (B) Rapamycin‐induced inter‐complex tethering of WT (upper) and SMC4 W‐loop mutant (lower) complexes. In the case of WT complexes, inter‐complex tethering facilitates chromosome assembly. Although the ability of the SMC4 W‐loop mutant complexes to assemble chromosomes is severely compromised, inter‐complex tethering partially compensates for these defects, producing chromosome axis‐like structures.

Mixing experiments (Figure 4) provided evidence that inter‐complex tethering has little effect on the loading efficiency of untethered complexes coexisting in the reaction mixture, whereas titration experiments (Figure 5) showed that inter‐complex tethering lowers the amount of condensin I required for chromosome assembly. Together, these results provide additional insights into how the tethered complexes may function. Our strategy for inter‐complex tethering via D2‐SMC4 generates “asymmetric dimers” of condensin I (Figure 7A). It is formally possible that only one of the dimeric complexes remains active, while the other, though functionally inert, is passively recruited to chromosomes by its partner, thereby giving rise to an apparent increase in loading efficiency. However, our functional assays show that it is not the case: inter‐complex tethering not only enhances condensin I loading but also markedly facilitates mitotic chromosome assembly. We speculate that the observed facilitation of mitotic chromosome assembly is mediated by an elaborate mechanism that goes beyond the action of individual complexes. For example, inter‐complex tethering via D2‐SMC4 could directly alter the spatial configuration of condensin I required for chromosome axis assembly, thereby mimicking its cooperative action under crowded conditions (Figure 7A). Notably, apparent functional facilitation was also observed when two SMC4 W‐loop mutant complexes were tethered (Figure 6) or in which an SMC4 W‐loop mutant was tethered with a WT complex (Figure S2). These results strongly suggest that inter‐complex tethering can partially compensate for the deficiency in D2‐SMC4 contact (Figure 7B), thereby providing further insight into how inter‐complex tethering contributes to the robustness of chromosome axis assembly.

We hypothesize that the individual actions of condensin I (e.g., loop extrusion) in the early stages are followed by their cooperative actions (e.g., condensin‐condensin interaction) in later stages, and that such progressive changes contribute to proper chromosome assembly (Figure 7A, Hirano 2025). In the literature, diffusion capture has been proposed as an alternative mechanism to loop extrusion (Gerguri et al. 2021; Tang et al. 2023). In this context, inter‐complex tethering might enable condensin I to capture more than two strands of dsDNA, thereby facilitating chromosome assembly. Alternatively, inter‐complex tethering could contribute to the later stages of mitotic chromosome assembly through mechanisms other than condensin‐condensin interactions, such as bridging‐induced attraction (Forte et al. 2024) or phase separation (Yoshimura and Hirano 2016; Pastic et al. 2024; Takaki et al. 2025).

Finally, we wish to note several limitations of the present study. First, although the rapamycin‐inducible FKBP‐FRB tethering system established here provides a powerful tool for manipulating condensin I function, artificially induced inter‐complex tethering does not fully recapitulate physiological reactions, necessitating careful interpretation of the outcomes. Second, while Xenopus egg extracts offer a “clean” system in which endogenous condensins can be completely replaced with exogenous ones, similar tethering approaches should be applied in cells, where the consequences can be assessed under more physiological conditions. Despite these caveats, the current study provides an important starting point for addressing how precise experimental perturbations of condensin I influence the morphology of mitotic chromosomes. At the mechanistic level, the relationship between the proposed condensin‐condensin interactions and other activities, including loop extrusion, remains to be explored in order to construct an integrated model of mitotic chromosome assembly.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Plasmid Construction and Mutagenesis

The construct for dual expression of mSMC2 and mSMC4 (pRK101) was generated as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2015). For expression of 3HA‐FKBP‐tagged mSMC4, codon‐optimized cDNA encoding 3HA‐FKBP‐3TEV‐site‐mSMC4 was synthesized by Thermo Fisher and subcloned into the SpeI and NotI sites of pRK101. Codon‐optimized cDNAs encoding the human non‐SMC subunits (hCAP‐D2, hCAP‐G, and hCAP‐H) were synthesized by Thermo Fisher, and subcloned into pFastBac1 between the EcoRI and SpeI sites, as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2022). For expression of FRB‐3FLAG‐tagged hCAP‐D2, a codon‐optimized cDNA encoding hCAP‐D2‐3TEV‐site‐FRB‐3FLAG was synthesized by Thermo Fisher, and subcloned into pFastBac1 between the EcoRI and SpeI sites. For expression of EGFP‐ or mCherry‐tagged hCAP‐H, codon‐optimized cDNAs encoding EGFP and mCherry were synthesized by Thermo Fisher and subcloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pFastBac1‐HaloTag‐hCAP‐H, thereby replacing HaloTag with EGFP or mCherry (Kinoshita et al. 2022). For introduction of the W1183A substitution into 3HA‐FKBP‐tagged mSMC4, the following oligonucleotides were used: forward 5′‐AAGTCGGCGAAGAAGATTTTCAACCT‐3′ and reverse 5′‐CTTCTTCGCCGACTTCTTAGGTGGACG‐3′.

4.2. Protein Expression and Purification of Recombinant Condensin I Complexes

Condensin subunits were expressed in insect cells using the Bac‐to‐Bac baculovirus expression system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2015, 2022). In brief, DH10Bac cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were transformed with the corresponding plasmid vectors to produce bacmid DNAs, which were then used to transfect Sf9 cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for baculovirus production. High Five cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were subsequently co‐infected with recombinant baculoviruses encoding mSMC2 and mSMC4 together with hCAP‐D2, hCAP‐G, and hCAP‐H. The resulting condensin I holocomplexes were purified from cell lysates by two‐step chromatography, as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2022).

4.3. Antibodies

Primary antibodies used in the current study were as follows: anti‐XSMC4/XCAP‐C (in‐house identifier: AfR8L, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody); anti‐XSMC2/XCAP‐E (AfR9‐7L, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody); anti‐XCAP‐D2 (AfR16L, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody); anti‐XCAP‐G (AfR11‐3L, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody) (Hirano and Mitchison 1994; Hirano et al. 1997); anti‐XCAP‐D3 (AfR196‐2L, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody); anti‐XCAP‐H2 (AfR201‐4, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody) (Ono et al. 2003); anti‐mSMC4 (AfR326‐3L, affinity‐purified rabbit antibody) (Lee et al. 2011); anti‐HA tag [EPR22819‐101] (Abcam, ab236632 [RRID: AB_2864361], rabbit antibody); anti‐FLAG M2 (Sigma, F‐1804 [RRID: AB_262044], mouse antibody); anti‐GFP (MBL, 598 [RRID: AB_591816], rabbit antibody); and anti‐mCherry (Takara Bio, 632,543 [RRID: AB_2307319], mouse antibody). Secondary antibodies were as follows: horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG (PI‐1000 [RRID: AB_2336198], Vector Laboratories, goat antibody); horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐mouse IgG (Abcam, ab205719 [RRID: AB_2755049], goat antibody); Alexa Fluor 488 anti‐rabbit IgG (A‐11008 [RRID: AB_143165], Thermo Fisher Scientific, goat antibody); Alexa Fluor 568 anti‐mouse IgG (A‐10037 [RRID: AB_2534013], Thermo Fisher Scientific, donkey antibody).

4.4. Rapamycin‐Induced FKBP‐FRB Dimerization and TEV Protease‐Mediated Tag Cleavage

For immunoprecipitation experiments, the FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes (175 nM each) were incubated in TBS‐T buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween‐20) containing 0.5% BSA in the presence of increasing concentrations of rapamycin (LC Laboratories; 0–2 μM) at 4°C for 60 min. The mixture was then combined with anti‐HA antibody‐conjugated Dynabeads Protein A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 4°C for another 60 min. The beads were washed three times with TBS‐T. Input and bead fractions were subjected to SDS‐PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. For immunoprecipitation of cleaved FKBP tags, FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes (400 nM total) were incubated in TBS‐T buffer containing 0.5% BSA in the absence or presence of rapamycin (5 μM) at 4°C for 60 min. Following rapamycin treatment, the mixture was supplemented with AcTEV protease (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1 U/μL) and incubated at 22°C for another 60 min. Immunoprecipitation was then performed as described above. For pretreatment of FKBP/FRB‐tagged complexes with rapamycin and/or TEV protease for the add‐back assay, the complexes (400 nM total) were incubated in TBS‐T buffer containing 0.5% BSA in the absence or presence of rapamycin (5 μM) at 4°C, or at 22°C when AcTEV protease treatment (1 U/μL) was included, for 60 min.

4.5. Preparation of Xenopus Egg Extracts and Immunodepletion

The high‐speed supernatant of metaphase‐arrested Xenopus egg extracts (M‐HSS) was prepared as described previously (Hirano et al. 1997). Immunodepletion of Xenopus condensins I and II from the extracts was performed as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2022). A first mixture of antibodies containing 12.5 μg of affinity‐purified anti‐XCAP‐D2 and 6.25 μg each of affinity‐purified anti‐XSMC4 and anti‐XSMC2 was coupled to 100 μL of Dynabeads Protein A (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A second mixture of antibodies containing 6.25 μg each of affinity‐purified anti‐XCAP‐D3, anti‐XSMC2, anti‐XCAP‐G, and anti‐XCAP‐H2 was coupled to another 100 μL of Dynabeads Protein A. One hundred microliters of extract was incubated with the first pool of beads at 4°C for 30 min, followed by incubation with the second pool of beads for another 30 min. The supernatant after the two successive rounds of depletion was used as a condensin‐depleted extract (Δcond extract).

4.6. Add‐Back Assay in Xenopus Egg Extracts and Immunofluorescence Analyses

Chromosome assembly assays using Xenopus egg extracts were performed as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2022), with some modifications. For standard add‐back assays, Δcond extracts were supplemented with purified recombinant complexes (17.5 nM or 2.8–35 nM as indicated) that had been pretreated with rapamycin and/or TEV protease, and preincubated at 22°C for 15 min. Xenopus sperm nuclei were then added at a final concentration of 1.0 × 103 nuclei/μL and incubated at 22°C for another 120 min to assemble chromosomes. After incubation, the reaction mixtures were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence analyses, as described previously (Kinoshita et al. 2022). In our previous study, we performed co‐immunoprecipitation experiments and concluded that subunit exchange between different complexes barely occurs in Xenopus egg extracts (Kinoshita et al. 2022). We therefore consider it unlikely that a fraction of complexes designed for inter‐complex tethering (in trans) could be converted into complexes competent for intra‐complex tethering (in cis). Microscopic observations were performed using an Olympus BX63 microscope equipped with a UPlanSApo 100×/1.40 oil‐immersion lens and an ORCA‐Flash 4.0 digital CMOS camera C11440 (Hamamatsu Photonics). Image acquisition was carried out using CellSens Dimension software (Olympus). Primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence in this study were anti‐mSMC4, anti‐GFP and anti‐mCherry.

4.7. Image Analysis and Statistics

Images acquired by immunofluorescence microscopy were subjected to quantitative analysis using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). For measurement of DNA and SMC4 intensities per DNA‐positive area, DAPI signals were segmented using the threshold function, and both the signal‐positive areas and the integrated intensities of DAPI and SMC4 signals were measured using the “Analyze Particles” function. The integrated intensities of EGFP and mCherry signals per DNA‐positive area were measured in the same manner. For measurement of line profiles of chromosomes, DAPI‐positive signals were scanned along lines drawn perpendicular to the chromosome axes and quantified using the Plot Profile function. For calculation of the compaction index, the integrated intensity of DAPI signals was divided by the corresponding DAPI‐positive area. Well‐assembled chromosomes are often dispersed, and thresholding such dispersed clusters can fail to properly binarize DAPI‐positive areas. For this reason, we used the compaction index only to compare clusters of chromosomes observed either at an early stage of chromosome assembly (30 min in Figure 4D) or at a low concentration of condensin I complexes (2.8 nM in Figure 5C and 7.0 nM in Figure S2E). The total number of images of chromatid clusters analyzed for each experiment is provided in the corresponding figure legends. All datasets were processed with Excel (Microsoft), and subsequent statistical analyses and graph generation were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad).

4.8. Animal Usage

All frog experiments were conducted in compliance with the institutional regulations of the RIKEN Wako Campus.

Author Contributions

Kazuhisa Kinoshita: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Yuuki Aizawa: investigation. Tatsuya Hirano: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1: Kinetics of TEV‐dependent proteolytic cleavage of tagged subunits. (A) Diagram of the stepwise treatment of rapamycin and TEV protease of the complexes. Complexes for inter‐ and intra‐tethering were incubated with rapamycin at 4°C for 60 min and then with TEV protease at 22°C for 60 min to examine the efficiency of proteolysis of pre‐tethered complexes. (B) Immunoblot of the complexes after the two‐step treatment with rapamycin and TEV protease as shown in (A). Samples were subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) Diagram of the simultaneous treatment of rapamycin and TEV protease of the complexes. Complexes for inter‐ and intra‐tethering were incubated with both reagents at 22°C for 60 min. (D) Immunoblot of the complexes after the simultaneous treatment of rapamycin and TEV protease as shown in (C). Samples were subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies (related to Figure 3).

Figure S2: Inter‐complex tethering with a WT complex compensates for the D2‐SMC4 contact deficiency of the mutant complex. (A) Schematic illustration of the combination of SMC4 W‐loop mutant and WT complexes for inter‐complex tethering. (B) Add‐back assay with rapamycin‐pretreated holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) or holo(D2‐FRB). Each single complex was pretreated with rapamycin and then analyzed in the add‐back assay (at 17.5 nM). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Titration experiment of rapamycin‐pretreated complexes for inter‐complex tethering. The add‐back assay was performed with the indicated concentrations of rapamycin‐pretreated holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) and holo(D2‐FRB). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity (SMC4 signal intensity relative to DNA signal intensity) from the experiment shown in (C). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 20, 37, 30, 37 for −rapamycin; n = 36, 35, 38 +rapamycin from left to right). (E) Quantification of the compaction index (the ratio of DNA intensity to DNA‐positive area) in the structures shown at 7.0 nM in (C). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 37, 36 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test (related to Figure 6).

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Hirano laboratory for their critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant number 23K05649 [to K.K.]; 18H05276 and 20H05938 [to T.H.]).

Kinoshita, K. , Aizawa Y., and Hirano T.. 2025. “Condensin‐Condensin Interactions Facilitate Mitotic Chromosome Assembly in Xenopus Egg Extracts.” Genes to Cells 30, no. 6: e70065. 10.1111/gtc.70065.

Funding: This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, 23K05649, 18H05276, 20H05938.

Transmitting Editor: Tatsuo Fukagawa

Contributor Information

Kazuhisa Kinoshita, Email: kinoshita@riken.jp.

Tatsuya Hirano, Email: hiranot@riken.jp.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Alipour, E. , and Marko J. F.. 2012. “Self‐Organization of Domain Structures by DNA‐Loop‐Extruding Enzymes.” Nucleic Acids Research 40, no. 22: 11202–11212. 10.1093/nar/gks925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballister, E. R. , Riegman M., and Lampson M. A.. 2014. “Recruitment of Mad1 to Metaphase Kinetochores Is Sufficient to Reactivate the Mitotic Checkpoint.” Journal of Cell Biology 204, no. 6: 901–908. 10.1083/jcb.201311113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszynski, L. A. , Liu C. W., and Wandless T. J.. 2005. “Characterization of the FKBP.Rapamycin.FRB Ternary Complex.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 127, no. 13: 4715–4721. 10.1021/ja043277y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, W. 1882. Zellsubstanz, Kern und Zelltheilung. F.C.W. Vogel. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, G. , Boteva L., Conforto F., Gilbert N., Cook P. R., and Marenduzzo D.. 2024. “Bridging Condensins Mediate Compaction of Mitotic Chromosomes.” Journal of Cell Biology 223, no. 1: e202209113. 10.1083/jcb.202209113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte, G. , Boteva L., Gilbert N., Cook P. R., and Marenduzzo D.. 2025. “Bridging‐Mediated Compaction of Mitotic Chromosomes.” Nucleus 16, no. 1: 2497765. 10.1080/19491034.2025.2497765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganji, M. , Shaltiel I. A., Bisht S., et al. 2018. “Real‐Time Imaging of DNA Loop Extrusion by Condensin.” Science 360, no. 6384: 102–105. 10.1126/science.aar7831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerguri, T. , Fu X., Kakui Y., et al. 2021. “Comparison of Loop Extrusion and Diffusion Capture as Mitotic Chromosome Formation Pathways in Fission Yeast.” Nucleic Acids Research 49, no. 3: 1294–1312. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goloborodko, A. , Imakaev M. V., Marko J. F., and Mirny L.. 2016. “Compaction and Segregation of Sister Chromatids via Active Loop Extrusion.” eLife 5: e14864. 10.7554/eLife.14864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassler, M. , Shaltiel I. A., Kschonsak M., et al. 2019. “Structural Basis of an Asymmetric Condensin ATPase Cycle.” Molecular Cell 74, no. 6: 1175–1188.e1179. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. 2016. “Condensin‐Based Chromosome Organization From Bacteria to Vertebrates.” Cell 164, no. 5: 847–857. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. 2025. “Mitotic Genome Folding.” Journal of Cell Biology 224, no. 7: e202504075. 10.1083/jcb.202504075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. , and Kinoshita K.. 2025. “SMC‐Mediated Chromosome Organization: Does Loop Extrusion Explain It All?” Current Opinion in Cell Biology 92: 102447. 10.1016/j.ceb.2024.102447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. , Kobayashi R., and Hirano M.. 1997. “Condensins, Chromosome Condensation Protein Complexes Containing XCAP‐C, XCAP‐E and a Xenopus Homolog of the Drosophila Barren Protein.” Cell 89, no. 4: 511–521. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T. , and Mitchison T. J.. 1994. “A Heterodimeric Coiled‐Coil Protein Required for Mitotic Chromosome Condensation In Vitro.” Cell 79, no. 3: 449–458. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, K. , Kobayashi T. J., and Hirano T.. 2015. “Balancing Acts of Two HEAT Subunits of Condensin I Support Dynamic Assembly of Chromosome Axes.” Developmental Cell 33, no. 1: 94–106. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, K. , Tsubota Y., Tane S., et al. 2022. “A Loop Extrusion‐Independent Mechanism Contributes to Condensin I‐Mediated Chromosome Shaping.” Journal of Cell Biology 221, no. 3: e202109016. 10.1083/jcb.202109016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, M. , Cutts E. E., Pan D., et al. 2020. “Human Condensin I and II Drive Extensive ATP‐Dependent Compaction of Nucleosome‐Bound DNA.” Molecular Cell 79, no. 1: 99–114.e119. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. G. , Merkel F., Allegretti M., et al. 2020. “Cryo‐EM Structures of Holo Condensin Reveal a Subunit Flip‐Flop Mechanism.” Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 27, no. 8: 743–751. 10.1038/s41594-020-0457-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , Ogushi S., Saitou M., and Hirano T.. 2011. “Condensins I and II Are Essential for Construction of Bivalent Chromosomes in Mouse Oocytes.” Molecular Biology of the Cell 22, no. 18: 3465–3477. 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T. , Losada A., Hirano M., Myers M. P., Neuwald A. F., and Hirano T.. 2003. “Differential Contributions of Condensin I and Condensin II to Mitotic Chromosome Architecture in Vertebrate Cells.” Cell 115, no. 1: 109–121. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastic, A. , Nosella M. L., Kochhar A., Liu Z. H., Forman‐Kay J. D., and D'Amours D.. 2024. “Chromosome Compaction Is Triggered by an Autonomous DNA‐Binding Module Within Condensin.” Cell Reports 43, no. 7: 114419. 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, J. R. , Hudson D. F., Cisneros‐Soberanis F., and Earnshaw W. C.. 2021. “Mitotic Chromosomes.” Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 117: 7–29. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, Y. , Mochizuki A., Kinoshita K., Hirano T., and Tachikawa M.. 2018. “Modeling the Functions of Condensin in Chromosome Shaping and Segregation.” PLoS Computational Biology 14, no. 6: e1006152. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata, R. , Niwa K., Ugarte La Torre D., et al. 2021. “Opening of Cohesin's SMC Ring Is Essential for Timely DNA Replication and DNA Loop Formation.” Cell Reports 35, no. 4: 108999. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki, R. , Savich Y., Brugués J., and Jülicher F.. 2025. “Active Loop Extrusion Guides DNA‐Protein Condensation.” Physical Review Letters 134, no. 12: 128401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.128401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tane, S. , Shintomi K., Kinoshita K., et al. 2022. “Cell Cycle‐Specific Loading of Condensin I Is Regulated by the N‐Terminal Tail of Its Kleisin Subunit.” eLife 11: e84694. 10.7554/eLife.84694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M. , Pobegalov G., Tanizawa H., et al. 2023. “Establishment of dsDNA‐dsDNA Interactions by the Condensin Complex.” Molecular Cell 83, no. 21: 3787–3800.e3789. 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, F. 2025. “A Unified Model for Cohesin Function in Sisterchromatid Cohesion and Chromatin Loop Formation.” Molecular Cell 85, no. 6: 1058–1071. 10.1016/j.molcel.2025.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T. , Kinoshita K., and Hirano T.. 2023. “Elasticity Control of Entangled Chromosomes: Crosstalk Between Condensin Complexes and Nucleosomes.” Biophysical Journal 122, no. 19: 3869–3881. 10.1016/j.bpj.2023.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, S. H. , and Hirano T.. 2016. “HEAT Repeats – Versatile Arrays of Amphiphilic Helices Working in Crowded Environments?” Journal of Cell Science 129, no. 21: 3963–3970. 10.1242/jcs.185710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Kinetics of TEV‐dependent proteolytic cleavage of tagged subunits. (A) Diagram of the stepwise treatment of rapamycin and TEV protease of the complexes. Complexes for inter‐ and intra‐tethering were incubated with rapamycin at 4°C for 60 min and then with TEV protease at 22°C for 60 min to examine the efficiency of proteolysis of pre‐tethered complexes. (B) Immunoblot of the complexes after the two‐step treatment with rapamycin and TEV protease as shown in (A). Samples were subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) Diagram of the simultaneous treatment of rapamycin and TEV protease of the complexes. Complexes for inter‐ and intra‐tethering were incubated with both reagents at 22°C for 60 min. (D) Immunoblot of the complexes after the simultaneous treatment of rapamycin and TEV protease as shown in (C). Samples were subjected to SDS‐PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies (related to Figure 3).

Figure S2: Inter‐complex tethering with a WT complex compensates for the D2‐SMC4 contact deficiency of the mutant complex. (A) Schematic illustration of the combination of SMC4 W‐loop mutant and WT complexes for inter‐complex tethering. (B) Add‐back assay with rapamycin‐pretreated holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) or holo(D2‐FRB). Each single complex was pretreated with rapamycin and then analyzed in the add‐back assay (at 17.5 nM). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Titration experiment of rapamycin‐pretreated complexes for inter‐complex tethering. The add‐back assay was performed with the indicated concentrations of rapamycin‐pretreated holo(FKBP‐SMC4W1183A) and holo(D2‐FRB). Fixed samples were labeled with an antibody against SMC4, and DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Quantification of SMC4/DNA intensity (SMC4 signal intensity relative to DNA signal intensity) from the experiment shown in (C). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 20, 37, 30, 37 for −rapamycin; n = 36, 35, 38 +rapamycin from left to right). (E) Quantification of the compaction index (the ratio of DNA intensity to DNA‐positive area) in the structures shown at 7.0 nM in (C). The mean and SD are indicated (n = 37, 36 from left to right). p values were determined by a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U test (related to Figure 6).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.