Abstract

A dodecameric protease complex with a tetrahedral shape (TET) was isolated from Haloarcula marismortui, a salt-loving archaeon. The 42 kDa monomers in the complex are homologous to metal-binding, bacterial aminopeptidases. TET has a broad aminopeptidase activity and can process peptides of up to 30–35 amino acids in length. TET has a central cavity that is accessible through four narrow channels (<17 Å wide) and through four wider channels (21 Å wide). This architecture is different from that of all the proteolytic complexes described to date that are made up by rings or barrels with a single central channel and only two openings.

Keywords: aminopeptidase/archaea/Halobium/protease/proteolysis

Introduction

The control of the half-life of proteins in the cytosol is a key cellular function accomplished by a small set of high molecular weight self-compartmentalizing proteases (Baumeister et al., 1998). In archaea and eukaryotes, proteins are broken down to oligopeptides by the endopeptidase activities of the proteasome (Akopian et al., 1997). In bacteria, proteins are processed by other protease families named Clp, Lon and HslVU (De Mot et al., 1999). The bacterial-like ATP-dependent protease Lon is also present in all archaea for which genome data are available, together with the proteasome system. Compartmentalization confines the peptidase activity to inner cavities that are only accessible for unfolded polypeptides. ATP-dependent regulatory complexes (PAN for archaea and ClpA for bacteria) bind to target proteins and act as reverse chaperones (unfoldases) in order to allow the access of the polypeptide chain into the active sites of the proteases (Weber-Ban et al., 1999; Benaroudj and Goldberg, 2000). In addition to the energy-dependent proteasome systems, four energy-independent protease complexes have been characterized. The tricorn protease (TRI) from Thermoplasma acidophilum is a hexamer of 6 × 120 kDa that possesses trypsin- and chymotrypsin- like activities (Tamura et al., 1996; Walz et al., 1997; Brandstetter et al., 2001). TRI can self-assemble in vivo into a giant icosahedral structure, which is thought to form the organizing center of a multienzyme proteolytic system and to act in synergy with at least three other monomeric aminopeptidasic factors (Tamura et al., 1998). TPPII is another giant protease complex in mammalian cells and consists of a stack of eight ring-shaped segments (Geier et al., 1999). It possesses both exoproteolytic (tripeptidyl peptidase) and endoproteolytic (trypsin-like) activities. The yeast bleomycin hydrolase and its bacterial counterpart PepC are cysteine proteases that form hexamers of 300 kDa (Joshua-Tor et al., 1995). Finally, the Bacillus subtilis DppA d-aminopeptidase consists of two pentameric, stacked rings (Remaut et al., 2001). All these large proteases are self-compartmentalizing and are metalloenzymes. They all have a ring (barrel)-shaped oligomeric structure, comparable with that of the proteasome, with an internal cavity that is lined with the protease active sites and two narrow channels leading to the central cavity that are only accessible to unfolded polypeptides.

It has been suggested that these energy-independent protease complexes are, either alone or together with other aminopeptidases (TRI), responsible for cleaving and eliminating the peptides generated by the endoproteolytic activity of the energy-dependent proteasome (Tamura et al., 1998). However, they may also be part of a rescue mechanism when the proteasome system does not function optimally. In an experiment where mammalian cells were adapted progressively to a proteasome inhibitor, the cells showed adaptation by overproducing other proteases that, among other activities, mediated peptide loading of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules (Glas et al., 1998). The in vitro catalytic properties of these newly overproduced proteases correspond to those of TPPII and TRI (Tamura et al., 1998; Geier et al., 1999). This could imply that these normally energy-independent proteases somehow interact with energy-dependent unfoldases (Wickner et al., 1999). Consistent with this idea, it was found that proteasome inhibitors also strongly induce molecular chaperones (Zhou et al., 1996). Here, we describe the isolation and characterization of TET, a novel energy-independent protease complex with a tetrahedral shape.

Results

The three-dimensional structure of TET, a dodecameric tetrahedral complex

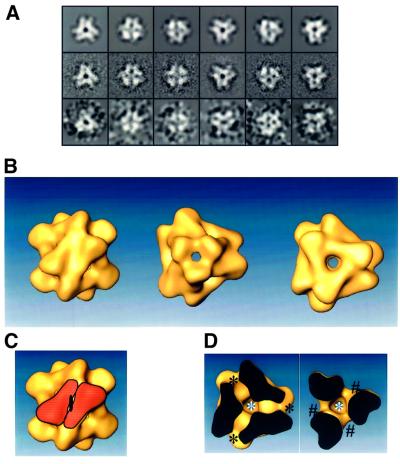

TET was detected as a large triangular complex by negative stain electron microscopy (EM) in the course of the purification of the proteasome from the extreme halophilic archaeon Haloarcula marismortui. The complex was purified to homogeneity and found to contain a single protein species with a mol. wt of 42 kDa (Figure 1). The mass of the complex was estimated by gel filtration to be in the range of 500 kDa. A three-dimensional reconstruction of the complex at 17 Å resolution was determined by image analysis of particles taken from electron micrographs, by using a projection matching method. For this EM analysis, we had to use the negative staining method instead of cryoEM because the complex was isolated from halophilic bacteria in 2 M salt. CryoEM is not possible at this salt concentration due to the high electron scattering of the medium leading to loss or inversion of contrast. The complex has a tetrahedral shape made of 12 subunits and with an edge of 150 Å (Figure 2). Each edge is made up of an antiparallel association of two monomers, as shown in Figure 2C. Six of these anti parallel pairs form the regular tetrahedron. The structure is not completely closed or tight. The connection between the different edges occurs only near the vertices of the structure, leaving some channels from the outside to the inside of the structure. There are two types of channel: one type in the middle of each facet with a diameter of 21 Å, and the second on the vertices with a smaller opening (<17 Å). These eight channels emerge into a central cavity with a diameter of 35 Å (Figure 2D).

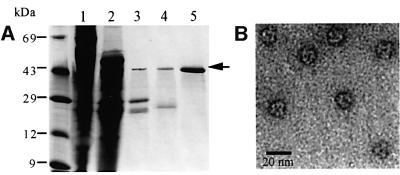

Fig. 1. Isolation and electron microscopy of TET. (A) SDS–PAGE of protein fractions from the different steps of the purification process. Proteins from H.marismortui were fractionated based on their differential sensitivity to heat denaturation and solubility in PEG 8000. A 15% PEG protein pellet was resuspended (lane 1) and fractionated on a DE52 ion exchange column (lane 2). The high molecular weight proteins were obtained by using a G4000 SW size exclusion column (TosoHaas) mounted on an HPLC chain (lane 3). The fractions were examined by electron microscopy and those that contained a triangular-shaped complex were pooled and loaded on a MonoQ-anion exchange column. The peak that contained the complex (lane 4) was purified further on a G3000 SW column. The obtained protein (lane 5) was found to be pure by mass spectrometry analysis. (B) Electron micrograph of a preparation of the purified protein negatively stained with uranyl acetate. The scale bar represents 20 nm.

Fig. 2. Image analysis and three-dimensional reconstruction of TET. (A) Reprojections of the three-dimensional structure of TET (top row) compared with the corresponding class averages used to calculate the three-dimensional reconstruction (middle row) and with some corresponding raw images (bottom row). The class averages were only phase flipped (see Materials and methods) and the raw images filtered to 25 Å to facilitate their interpretation. The size of each square is 225 × 225 Å. (B) Three-dimensional structure of TET at 17 Å resolution viewed down a 2-fold axis (left), a 3-fold vertex (middle) and a 3-fold facet (right). (C) Same view as (B) left, but with one antiparallel dimer highlighted in orange. (D) Visualization of the two types of channel in TET. The complex is in the same orientation as in (B) right, with the foreground cut out until the level of the three vertices (left) and the center of the three facets (right). The narrow channels on the vertices are marked with asterisks and the wider channels on the facets with hash symbols. The two views also show the diameter of the inner cavity.

TET is an aminopeptidase

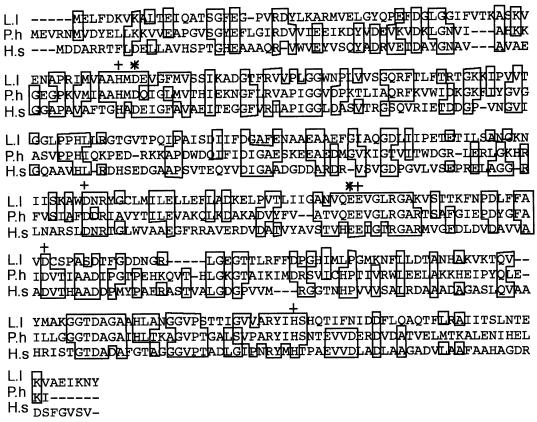

The sequence of the protein was determined by nano-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry of tryptic peptides. The protein is homologous to a 42 kDa protein that was identified originally as an endoglucanase in the genome of Halobacterium sp. (Ng et al., 2000). However, comparison with other sequence databases revealed a homology of the Halobacterium protein with several other proteins that are all weakly homologous to M42 aminopeptidases. Alignment with two assigned M42 aminopeptidases from bacterial and archaeal species revealed a significant homology (21.7 and 27% identity, respectively; Figure 3). Furthermore, the sequence alignment revealed that the residues involved in the predicted metal-binding site and in the putative active site were conserved.

Fig. 3. Alignment of two assigned bacterial and archaeal M42 aminopeptidase sequences with the sequence of the TET protein from Halobacterium sp. The residues that are conserved in at least two sequences are boxed. L.l, Lactococcus lactis, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. X81089; P.h, Pyrococcus horikoshii, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AP000006; H.s, Halobacterium sp. NRC1, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AE005064. Crosses indicate the amino acids that are putatively involved in metal binding, and asterisks indicate the putative active sites residues (according to MEROPS, a protease databank available online at: http://www.merops.ac.uk).

Aminopeptidases are exoproteases that catalyze the sequential removal of amino acid residues from the N-terminus of peptides (Taylor, 1993). Many aminopeptidase activities have been described, but only a few assigned enzymes have been sequenced (Gonzales and Robert-Baudouy, 1996). In order to check whether the purified protein was indeed a peptidase and to identify its nature, we first tested its activity against chromogenic substrates. The chromophore pNA group of mono-, di- and tri-Ala-pNA was shown to be released by TET at 3400, 2950 and 1800 µmol/h/mg, respectively. In the case of tri-Ala-pNA, a lag time was observed that could be due to the removal of the first two alanyl residues before release of pNA, suggesting aminopeptidase activity. In addition, the N-terminally blocked Suc-Ala-Ala-pNA was not digested, showing that a free N-terminus is required for processing and that the enzyme does not have deblocking activity. Pre-incubation of the protein with 1 mM of the chelating agent orthophenanthroline fully abolished the enzymatic activity, which confirmed the metallopeptidase identity of the enzyme.

TET can autonomously process large peptides

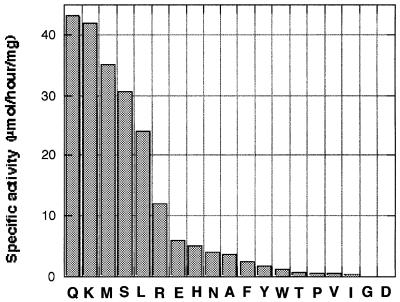

For further characterization of TET substrate specificity, we tested its activity against 19 mono-amino acyl compounds, either chromogenic (pNA) or fluorogenic (AMC) (Figure 4). The results showed that TET possesses a broad specificity with a preference for neutral and basic residues, while aromatic and branched residues are cleaved more slowly. Asp-pNA and Gly-pNA were found to remain undigested. However, as shown below, these residues can be released from peptides. We then tested the peptidase activity against synthetic peptides of various lengths (Table I). All cleavable peptides were processed sequentially from their N-terminus and neither endopeptidase nor carboxypeptidase activities were detected. A typical example is shown for the digestion of the 10 residue peptide AIT-Ad2 (AITIGNKND) (Figure 5). Aliquots were removed from the reaction mixture during incubation of the peptide with the aminopeptidase. The digestion products were separated by HPLC on a reversed-phase column and identified by MALDI mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequencing. The full-length peptide disappeared completely from the reaction mixture within 15 min. Three newly generated peptides accumulated and disappeared progressively with time. These results clearly showed that the protein degraded the peptide sequentially from its N-terminus. The observed specificity for all the tested peptides agrees with the results obtained with the mono-amino acyl-pNAs or -AMCs (compare Figure 4 and Table I). All accumulating fragments that were identified by mass spectrometry have a ‘difficult’ residue at their N-terminus (T, V, I, G or D), whereas fragments beginning at an ‘easy’ residue (K, M, S, L or R) were not, or very poorly, detected. The only differences observed in the digestion patterns of the mono-amino acyl-pNAs or -AMCs and of the peptides were that Asp-pNA and Gly-pNA were not cleaved whereas aspartic acid and glycine residues could be released from peptides MBL(176–185), C12L, DRO144 and DRO174 (Table I). This observation indicated that residues on the C-terminal side of the cleavage site on the peptide have an influence on the cleavage reaction. Other factors could also modulate the cleavage efficiency. In the case of DRO144, only two accumulating products (–3 and –10) were observed, starting at the first and the third aspartyl residues, respectively. No fragment starting at the second aspartyl residue was detected, indicating that this aspartyl residue was cleaved more readily by the enzyme. TET could cleave Pro-pNA at a rate comparable with that of Val- or Ile-pNA (Figure 4). However, X-Pro bonds are resistant to TET, as observed for the uncleaved Ala-Pro-pNA and the peptide C12L (Table I), where the fragment –3 (TPQDLNTML) accumulated over time and no further digestion was detected even after 5 days incubation at 40°C. This was also observed for the digestion of DRO174, where the only accumulating fragment started at residue –8 (SPED…) (Table I). Finally, TET was also able to cleave cysteinyl residues, as shown in the case of the peptide C12L (Table I), showing that, apart from X-Pro bonds, all residues could be released by TET. The rate of release of the first residue indicates that the shortest peptides (9–12 residues) were cleaved more efficiently than peptides of ≥19 residues, and cleavage was absent for peptides of 40 amino acids long (Table I). This length effect may be due to steric factors disfavoring the entrance of long peptides into the cavity of TET.

Fig. 4. Substrate specificity of TET. The hydrolytic reactions were measured by using chromogenic (pNA) or fluorogenic (AMC) monoacyl compounds as described in Materials and methods.

Table I. Effect of peptide lengths and sequence on the TET aminopeptidase activity.

| Peptide namea | Sequenceb | Significant fragmentsc | % of remaining intact peptide/cleavage timed |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIT-Ad2 | AITIGNKND (9) | –1, –2, –3 | 0%/30 min |

| MBL(176–185) | VDLTGNRLTY (10) | –1, –3, –4 | 0%/90 min |

| C12L | CGATPQDLNTML (12) | –1, –2, –3 | 25%/150 min |

| Tub-Cter | VDSVEGEGEEEGEE (14) | –1 | 96%/20 h |

| DRO144 | IYMDKIRDLLDVSKVNLSV (19) | –3, –10 | 43%/3 h, 31%/15 h |

| DRO174 | GATERFVSSPEDVFEVIEEGKSNRHIA (27) | –8 | 95%/3 h |

| RBPCoAtr | MQVTMKSSAVSGQRVGGARVATRSVRRAQLQV (32) | –1, –2 | 90%/3 h, 34%/20 h |

| ColX-NC2 | VFYAERYQMPTGIKGPLPNTKTQFFIPYTIKSKGIAVRG (39) | None | 100%/3 h |

| DiE-Ad3-pK20 | AKRARLSTEFNPVYPYEDEE-(K)20 (40) | None | 100%/15 h |

aPeptides were submitted to cleavage by TET and the reaction products were identified as described in Figure 5. All peptides were synthesized using an automatic synthesizer Applied Biosystems 430A and Boc chemistry, and purified by reversed-phase HPLC. The purity and identity of the synthetic peptides were assessed by reversed-phase HPLC and electrospray mass spectrometry.

bThe number of amino acids is indicated in parentheses.

cOnly fragments markedly accumulating during the assay are indicated. In some cases, some fragments could not be detected as they were not retained by the C18 column, or identified by mass spectrometry due to their low molecular weight.

dThe percentage of remaining intact peptide was determined by measuring the chromatographic peak heights of detected peptides.

Fig. 5. TET acts sequentially on peptide substrates. (A) Chromato graphic profiles of the degradation of the nine residue peptide AIT-Ad2. TET (0.5 µg) was mixed together with 10 nM of peptide. At the indicated times, aliquots were removed from the reaction mixture and the proteolytic products were resolved from the peptide substrates by analytical reversed-phase HPLC and identified by MALDI mass spectrometry. The N-terminal sequences of all accumulating peptides are indicated. (B) The peak areas in (A) were plotted against time.

Discussion

Aminopeptidases are ubiquitous exopeptidases that are of critical biological and medical importance because of their role in protein maturation, determination of protein stability and in the metabolism of biologically active peptides (Gonzales and Robert-Baudouy, 1996). In these processes, aminopeptidases with complementary specific activities act synergistically. Regarding their contribution to protein degradation pathways, in vivo experiments suggested that bestatin-sensitive aminopeptidases operate in the very last steps by eliminating small peptides (2–3mers) (Botbol and Scornik, 1991). In T.acidophilum, in vitro studies strongly supported that this process may involve the co-operation between TRI and its three interacting monomeric aminopeptidasic factors (Tamura et al., 1998). The occurence of TRI in other genomes appears to be patchy; in particular, no TRI homolog has been found in Halobium. Here, we demonstrated that TET can autonomously process a broad range of peptides whatever their amino acid composition. Our data suggest that a major biological function of TET could be the final degradation of the pool of peptides released by the proteasome (6–12mers) or Lon (3–24mers) (Kisselev et al., 1999). Thus, TET may be a functional homolog of the TRI aminopeptidase system described for Thermo plasma.

Until this work, all the large oligomeric proteases were found to correspond to the ring or barrel model. Even bleomycin hydrolase, a cysteine exopeptidase, was found to have a striking similarity to the proteasome (Joshua-Tor et al., 1995). Therefore, the aminopeptidase TET represents a new type of large protease complex. The existence of channels with dimensions that are similar to those of TRI suggests that TET, like the proteasome, is self-compartmentalized with the active sites situated in the inner cavity. Since the largest opening that gives access tothecentralcavity is 21Å wide, only partially unfolded peptides will have access to the active sites. The asymmetrical character of the channels suggests a vectorial transit of the peptide chain, the largest opening being the best candidate to be the entry gate, while the smallest could be the exit for the free amino acids.

Materials and methods

Protein purification

Haloarcula marismortui cells were grown and harvested as described (Franzetti et al., 2001). A 10 g aliquot of cells was resuspended in 2.5 vols of homogenate buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2, 2 M NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mg of DNase I (Roche)] and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with agitation before lysis by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged for 30 min at 15 000 g. Polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) was added [5% final (w/v)] to the supernatant. After a 15 min 10 000 g centrifugation, the supernatant PEG 8000 concentration was increased to 15%. The extract was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 28 ml of homogenate buffer, boiled for 5 min and quickly placed on ice for 15 min. The extract was centrifuged at 15 000 g for 15 min, and 50 ml of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2, 3 M (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM DTT were added to the supernatant. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 15 000 g for 15 min, filtered and loaded on a DE 52 ion exchange column (Whatman) that was equilibrated in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 2 M (NH4)2SO4, 1.5 M NaCl. Bound proteins were eluted stepwise in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 1.75 M (NH4)2SO4, 1.9 M NaCl. The fraction was dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 2 M KCl, and concentrated by using an Amicon centriprep 30 device. Size exclusion chromatography with samples containing TET were run on a G4000 SW column (0.78 × 60 cm, TosoHaas) mounted on an HPLC chain with a flow rate of 0.9 ml/min. The protein sample was then diluted 10 times with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2, loaded on a MonoQ HR 5X5 column (Amersham-Pharmacia) and eluted with a 20 ml linear gradient from 0.2 to 2 M KCl in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2. TET complex was then finally purified on a G3000 SW column. The fraction containing TET was dialyzed against 3 M KCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6 and contained only TET as judged by mass spectrometry analysis.

Peptidase assays

The hydrolytic reactions on mono-amino acyl peptides were measured by using chromogenic (pNA) or fluorogenic (AMC) compounds from Bachem. Specific activity measurements were initiated by addition of 0.2 µg of enzyme to 100 µl of pre-warmed assay mixture containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 2 M KCl and 100 µM of peptide. The hydrolysis of the substrate was monitored in a continuous rate assay at 40°C. Linear rates of increasing fluorescence intensity (excitation wavelength of 370 nm and emission at 460 nm) or optical density at 406 nm were recorded for up to 30 min.

For proteolytic assays, 0.5 µg of TET was mixed together with 10 nM of peptide in 100 µl of 2 M KCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6. At determined times, 15 µl aliquots were removed and added to 85 µl of 6 M guanidinium–HCl in order to stop the reaction. The cleavage products were resolved from the peptide substrates by analytical reversed-phase HPLC on a Vydac C18 column (0.46 × 25 cm) using a linear gradient of acetonitrile (0–30%) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid over 30 min. The separated fragments were collected and identified by MALDI mass spectrometry. N-terminal sequence analyses were performed on an Applied Biosystems model 477A protein sequencer, and amino acid phenylthiohydantoin derivatives were identified and quantified online with a model 120A HPLC system.

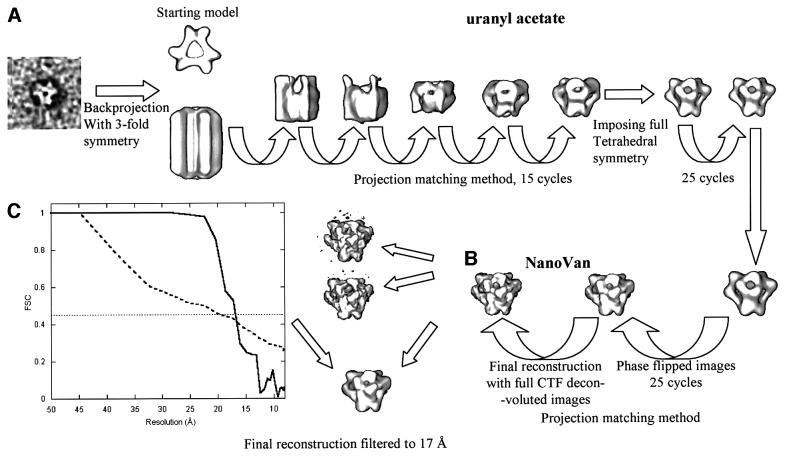

Electron microscopy

Samples at 0.1 mg/ml in 2 M KCl were negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate or 1% methylamine vanadate, CH3NH2VO3 (‘NanoVan’, Nanoprobes, Inc., Stony Brook, NY). We used NanoVan because of its natural pH value of 8, whereas uranyl acetate is at pH 4. Further, NanoVan spreads very evenly on the carbon film, giving a smooth background. It does not seem to stand up towards the sides of the complex and does not give a very dark stained ring around the particles. We also found that this stain is more stable under the electron beam than uranyl acetate, as claimed in http://www.nanoprobes.com/MSANV.html. The images were taken under low dose conditions on a JEOL EXII electron microscope at 100 kV accelerating voltage. Kodak SO3 film was developed for 9 min in three times diluted developer. The best micrographs were selected using an optical bench (no astigmatism or drift) and scanned with a Zeiss scanner at 14 µm pixel size (3.5 Å on the sample scale). The entire image analysis procedure is pictured in Figure 6. The image analysis procedure was started by selecting 1300 particles stained with uranyl acetate in 64 × 64 pixel squares from five micrographs by using Ximdisp (Crowther et al., 1996). The images were low pass filtered to 25 Å resolution in order to exclude the first zero of the phase contrast transfer function (CTF). A starting model was created using one centered raw image that showed a clear 3-fold axis. This single image was back projected using 3-fold symmetry in a 64 × 64 × 64 box and the height of the reconstruction was limited to 1.5 times the apparent diameter of the particle (Figure 6; the method of making this kind of starting model was used before in Schoehn et al., 2000). This starting model was then used in the projection matching method implemented in SPIDER (Frank et al., 1996; Roseman et al., 1996; Schoehn et al., 2000). After 15 cycles of refinement (projection of the model, comparison with the raw images, class average, three-dimensional reconstruction by back projection) and by imposing just one 3-fold axis, the tetrahedral shape of the reconstruction became obvious (Figure 6A, right). Because of the tetrahedral shape of the 3-fold reconstruction and because the reprojections of the tetrahedral structure fitted very well with the raw images (Figure 2, see in particular the 2-fold axis of the images in the second row), we imposed full tetrahedral symmetry to the reconstruction (point group 32). This symmetry is consistent with the size of the complex [12 × 42 kDa (≈500 kDa)]. The number of reprojections was lowered according to the new asymmetric unit (point group 32). A further 25 cycles of refinement were performed until the reconstruction was stable. Then 4000 particles stained with 1% NanoVan were selected from 12 micrographs using the X3D program. For each micrograph, we calculated a power spectrum to determine the defocus (Conway and Steven, 1999). In order to do this, we used a full search method that determined the best amplitude contrast percentage and defocus by applying a root mean square method (J. Conway, personal communication). In all the micrographs, the amplitude contrast was ∼25% and the defocus values were between 1 and 2.5 µm. The full set of particles was corrected using these values in two different ways: simple phase flip or full CTF deconvolution (Conway and Steven, 1999). The information was low pass filtered to 12 Å and we used the phase-flipped set of particles to continue the refinement starting with the final uranyl acetate model. This model was reprojected in 114 orientations equally distributed in the tetrahedral asymmetric unit and the refinement was done using the same projection matching method as described above (Figure 6B). Seventy-five percent of the images that had the highest correlation coefficient with the reprojection of the model were included in the reconstruction. The final reconstruction was calculated using the full CTF deconvoluted set of images (Figure 6B, left). The resolution limit was estimated by splitting the data randomly into two halves, making separate reconstructions from each half of the data set. These reconstructions were then compared by Fourier shell correlation (FSC) (cross-correlation coefficient between the three-dimensional volumes as a function of spatial frequency) in SPIDER (thick line in Figure 6C). The horizontal line represent the 0.45 correlation cut-off, and the crossing of this line and the FSC curve gives a resolution of 17 Å. The dashed curve is the 3σ threshold curve corrected for the tetrahedral symmetry (multiplied by √12 because of the tetrahedral symmetry; Orlova et al., 1997). The threshold curve crosses the FSC curve at a resolution of ∼16 Å. The two estimates of the resolution are consistent with each other. For the iso-surface representation, we included the correct molecular weight of the complex using an average protein density of 0.84 Da/Å3.

Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the image analysis procedure used to calculate a model for TET. (A) The scheme closely follows the description given in the electron microscopy section of Materials and methods, with the definition of the starting model (left) derived from a 3-fold symmetrical view of TET negatively stained with uranyl acetate, followed by 15 cycles of refinement by the projection matching method. When the tetrahedral shape was apparent (right), this symmetry was imposed and a model from the uranyl-stained particle was derived by 25 cycles of projection matching. This model was then used to perform 25 additional cycles of refinement using NanoVan-stained particles, as indicated in Materials and methods (B). The final reconstruction was made by using the full CTF deconvoluted images. The resolution of the reconstruction was determined by two methods (C) and found to be ∼17 Å, and the final reconstruction was subsequently filtered to this resolution.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank James Conway (IBS) for his help with the CTF correction and for helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Akopian T.N., Kisselev,A.F. and Goldberg,A.L. (1997) Processive degradation of proteins and other catalytic properties of the proteasome from Thermoplasma acidophilum. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 1791–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister W., Walz,J., Zuhl,F. and Seemuller,E. (1998) The proteasome: paradigm of a self-compartmentalizing protease. Cell, 92, 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benaroudj N. and Goldberg,A.L. (2000) PAN, the proteasome-activating nucleotidase from archaeabacteria, is a protein-unfolding molecular chaperone. Nature Cell Biol., 2, 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstetter H., Kim,J.S., Groll,M. and Huber,R. (2001) Crystal structure of the tricorn protease reveals a protein disassembly line. Nature, 414, 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botbol V. and Scornik,O.A. (1991) Measurement of instant rates of protein degradation in the livers of intact mice by the accumulation of bestatin-induced peptides. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 2151–2157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J.F. and Steven,A.C. (1999) Methods for reconstructing density maps of ‘single’ particles from cryoelectron micrographs to subnanometer resolution. J. Struct. Biol., 128, 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther R.A., Henderson,R. and Smith,J.M. (1996) MRC image processing programs. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mot R., Nagy,I., Walz,J. and Baumeister,W. (1999) Proteasomes and other self-compartmentalizing proteases in prokaryotes. Trends Microbiol., 7, 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J., Radermacher,M., Penczek,P., Zhu,J., Li,Y., Ladjadj,M. and Leith,A. (1996) SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualisation of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzetti B., Schoehn,G., Ebel,C., Gagnon,J., Ruigrok,R.W. and Zaccai,G. (2001) Characterization of a novel complex from halophilic archaebacteria, which displays chaperone-like activities in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 29906–29914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier E., Pfeifer,G., Wilm,M., Lucchiari-Hartz,M., Baumeister,W., Eichmann,K. and Niedermann,G. (1999) A giant protease with potential to substitute for some functions of the proteasome. Science, 283, 978–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glas R., Bogyo,M., McMaster,J.S., Gaczynska,M. and Ploegh,H.L. (1998) A proteolytic system that compensates for loss of proteasome function. Nature, 392, 618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales T. and Robert-Baudouy,J. (1996) Bacterial aminopeptidases: properties and functions. FEMSMicrobiol. Rev., 18, 319–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshua-Tor L., Xu,H.E., Johnston,S.A. and Rees,D.C. (1995) Crystal structure of a conserved protease that binds DNA: the bleomycin hydrolase, Gal6. Science, 269, 945–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev A.F., Akopian,T.N., Woo,K.M. and Goldberg,A.L. (1999) The sizes of peptides generated from protein by mammalian 26 and 20S proteasomes. Implications for understanding the degradative mechanism and antigen presentation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 3363–3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng W.V. et al. (2000) From the cover: genome sequence of Halobacterium species NRC-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 12176–12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlova E.V., Dube,P., Harris,J.R., Beckman,.E, Zemlin,F., Markl,J. and van Heel,M. (1997) Structure of keyhole limpet hemocyanin type 1 (KLH1) at 15 Å resolution by electron cryomicroscopy and angular reconstitution. J. Mol. Biol., 271, 417–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaut H., Bompard-Gilles,C., Goffin,C., Frere,J.M. and Van Beeumen,J. (2001) Structure of the Bacillus subtilisd-aminopeptidase DppA reveals a novel self-compartmentalizing protease. Nature Struct. Biol., 8, 674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseman A.M., Chen,S., White,H., Braig,K. and Saibil,H.R. (1996) The chaperonin ATPase cycle: mechanism of allosteric switching and movements of substrate-binding domains in GroEL. Cell, 87, 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoehn G., Quaite-Randall,E., Jimenez,J.L., Joachimiak,A. and Saibil,H.R. (2000) Three conformations of an archaeal chaperonin, TF55 from Sulfolobus shibatae. J. Mol. Biol., 296, 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T., Tamura,N., Cejka,Z., Hegerl,R., Lottspeich,F. and Baumeister,W. (1996) Tricorn protease—the core of a modular proteolytic system. Science, 274, 1385–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura N., Lottspeich,F., Baumeister,W. and Tamura,T. (1998) The role of tricorn protease and its aminopeptidase-interacting factors in cellular protein degradation. Cell, 95, 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. (1993) Aminopeptidases: towards a mechanism of action. Trends Biochem. Sci., 18, 167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz J., Tamura,T., Tamura,N., Grimm,R., Baumeister,W. and Koster,A.J. (1997) Tricorn protease exists as an icosahedral supermolecule in vivo. Mol. Cell, 1, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner S., Maurizi,M.R. and Gottesman,S. (1999) Posttranslational quality control: folding, refolding and degrading proteins. Science, 286, 1888–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Ban E.U., Reid,B.G., Miranker,A.D. and Horwich,A.L. (1999) Global unfolding of a substrate protein by the Hsp100 chaperone ClpA. Nature, 401, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Wu,X. and Ginsberg,H.N. (1996) Evidence that a rapidly turning over protein, normally degraded by proteasomes, regulates hsp72 gene transcription in HepG2 cells. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 24769–24775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]