Abstract

Background

Trauma is a heterogeneous disease entity, with high rates of mortality and morbidity observed globally. While the health systems in which trauma patients are cared for worldwide have been previously assessed to varying degrees, many of the system processes that shape trauma patient outcomes remain unknown.

Methods

We conducted a survey of 187 hospitals across 51 countries, through the GOAL-Trauma collaborative network. We explored prehospital, intrahospital and rehabilitation phases of trauma care. Data were compared across Human Development Index (HDI) tertiles, with thematic analyses performed to identify similarities and variation across settings.

Findings

Hospital-based care appeared to develop preferentially out of the three phases of trauma care, with challenges from the middle HDI tertile being more analogous to the upper HDI tertile than the lower HDI tertile. A lack of emergency medical services, limited patient finances and a lack of health literacy were common causes of prehospital delay in the lower and middle HDI tertiles. Surgeons and anaesthetists working in lower and middle HDI tertiles perform approximately 3-fold and 10-fold more operations, respectively, compared with upper HDI tertile counterparts. Across all HDI tertiles, infection was reported as the most common cause of postoperative morbidity.

Interpretation

A wide range of resources and processes exist globally in trauma care. Our findings suggest that with increasing resource availability, in-hospital care of trauma patients develops preferentially over prehospital or rehabilitation services. There is a clear need to coordinate available resources across all phases of care in order to improve outcomes among trauma patients.

Keywords: Injury, Health policy, Health systems, Health systems evaluation, Surgery

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The majority of trauma patients worldwide receive care outside of a formalised trauma system, with their healthcare shaped through more organic processes, the procedures and processes of which are poorly understood.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

There is significant global variation across all phases of trauma care.

Lower resource settings appear to experience more financial-related and procurement-related issues, while higher resource settings appear to experience more systems-level and process-level issues.

Hospital-based care appears to develop preferentially out of all the phases of trauma care.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

While there are clear targets for capacity building in trauma care from across the patient pathway, given the breadth of issues highlighted, use of a systems approach is essential if the overall standard of global trauma care is to be improved.

Introduction

Traumatic injuries result in 10% of all disability-adjusted life years globally1 and cause over 5 million deaths per year.2 Despite the disproportionately high number of trauma-related casualties in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs),3 it has been estimated that LMICs perform trauma surgery at a rate that is just 6% of the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery’s benchmark country.4 This is further compounded by a well-documented dearth of healthcare professionals (including surgeons) in LMICs.5 As a result, the need to improve trauma care and strengthen trauma systems globally has been identified as a priority by the World Health Assembly6—by improving trauma systems, medically preventable deaths can be reduced by up to 50%.7

However, development in global trauma care provision requires improvements to be made across the entire patient pathway. Comprehensive trauma care requires a complex system of intersecting processes and behaviours, all linking across co-existing healthcare services and regional infrastructure.8 A lack of emergency medical services, financial barriers and a lack of hospital infrastructure have previously been cited as individual factors that can limit a trauma service.59,12 However, when viewed through a wider lens, much less is known how their interactions impact overall trauma care at a systems level. Improvement to an individual aspect of trauma care is unlikely to improve overall patient outcomes in isolation, and a more holistic system-level view is often warranted.8

Despite the enormous global burden of trauma and its resultant economic impact,13 14 the care of trauma patients in LMICs remains an under-researched field of global health. As the vast majority of trauma patients worldwide receive care outside of a formal trauma system,15 their healthcare journey is shaped much more through organic processes, from which emerge even more complex patterns of care. Understanding these patterns and their inherent limitations is key to improving patient outcomes following trauma, yet there is still a relative paucity of published prospective data on this topic, especially in less-resourced settings.16 Evaluating such a complex system can be a challenging task, as all component parts and interactions must be assessed, not just individual patient pathways.

By surveying collaborators within an established global trauma research network, this study aimed to investigate the current characteristics, functions and limitations of hospitals worldwide that provide trauma care, across prehospital, intrahospital and rehabilitation phases of care.

Methods

Study design and setting

The GOAL-Trauma study was a prospective, international, multicentre, observational study, conducted between April 2024 and December 2024.17 The study received ethical approval from the Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE.2023.119) and was registered to ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06180668), with the study sponsored by the University of Cambridge (Cambridge, UK).

The study methodology has been previously described extensively.18 In brief, recruitment of hospitals was through open invitation, with potential collaborators contacted through a purposive snowballing technique, using pre-existing research networks, personnel contacts and social media. The study recruited 187 centres across 51 countries, representing each of the six inhabited continents and all strata in the World Bank country classification by income level.19 Each recruiting centre appointed a lead investigator (termed the ‘local lead’), who was invited to complete an online structured survey regarding trauma care at their institution.

The survey was distributed using a secure web-based system, REDCap cloud,20 21 and survey data were stored securely on the University of Cambridge password-protected servers, with no personally identifiable information involved. Only one response was permitted per hospital. The full survey can be found in the online supplemental material.

Study outcomes

The survey was designed based on previous international multicentre collaborative research studies22 and core themes identified from global trauma guidelines.23 24 The survey was further refined through expert consensus, involving clinicians and academics across a range of specialties, including prehospital medicine, surgery, anaesthesia and intensive care, with experience across a range of income settings.

Study questions were categorised into four groups: hospital characteristics and provision; prehospital phase of care; preoperative and intraoperative phase of care; postoperative and rehabilitation phase of care. The prehospital phase of care was defined as being from the time of injury to the arrival at the treating centre, the preoperative and intraoperative phase of care as from arrival at the treating centre until the end of the initial treatment or index operation, and the postoperative and rehabilitation phase as the time after the initial treatment or index operation until recovery. Select aspects of the survey also included free text responses.

Data analysis

Each hospital was stratified based on its national Human Development Index (HDI),25 with the HDI categorised into lower tertile, middle tertile and upper tertile. Data were summarised using mean and SD, median and IQR or number and percentage, where appropriate. Differences between HDI tertiles were assessed with ANOVA or χ² test where appropriate, with a p value <0.05 taken as the threshold of statistical significance.

Respondents were asked to report the number of trauma patients presenting, admitted and operated on, as well as the number of surgeons and anaesthetists. These numbers were screened for feasibility, and where inconsistencies were identified, local leads were contacted to clarify their responses; where no response was received, the data for these specific responses were excluded from analysis.

Inductive qualitative content analysis (QCA)26 was performed on the free text responses to distill recurring themes raised by the respondents. Ontologically, the QCA adopted a relativist position,27 recognising the existence of multiple and co-existing realities, whereby each participant could experience and describe their world differently.

Patient and public involvement

A patient and public involvement (PPI) discussion group was convened for the study, with individuals who had specific lived experiences relevant to the project. Throughout the protocol development stage, feedback was obtained from the PPI group that directly influenced aspects of methodology.

Results

Hospital characteristics and provision

Responses were received from every participating hospital in the GOAL-Trauma study, with 54 hospitals from 15 lower HDI tertile countries, 50 hospitals from 16 middle HDI tertile countries and 83 hospitals from 20 upper HDI tertile countries (online supplemental material). There was a predominance towards urban hospitals (173 of 187 respondents, 92.5%), government-funded hospitals (162 of 187 respondents, 86.6%) and tertiary centres (139 of 173 respondents, 74.3%) in those surveyed. Half of the hospitals reported a population served of over one million (94 of 187 respondents, 50.3%).

When asked to rank which phase of trauma care management should be improved for the greatest impact on trauma outcomes, there were significant differences across tertiles (p<0.001); those in the lower HDI tertile preferentially reported prehospital care (29 of 54 respondents, 53.7%), respondents in the middle HDI tertile stated in-hospital care (24 of 50 respondents, 48%) and those in the upper HDI tertile stated rehabilitation (36 of 83 respondents, 43.4%).

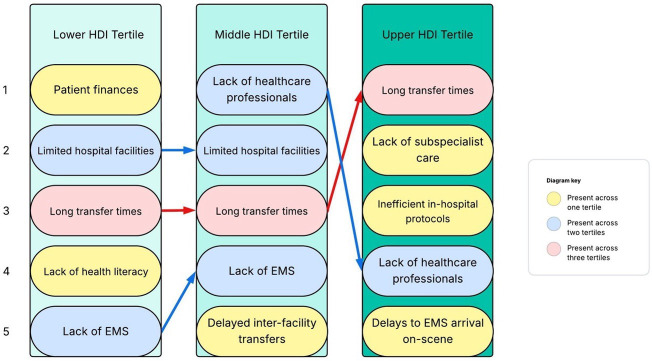

When asked about the main limitations in accessing trauma care, half of the barriers mentioned across all tertiles occurred in the prehospital environment (figure 1). Long transfer times were reported across all the HDI tertiles as a key barrier. Similarities in the barriers reported were observed between lower and middle HDI tertile respondents, respectively, with three of the five most common barriers cited across both.

Figure 1. The most common barriers reported by respondents in accessing trauma care, numbered 1 to 5, stratified by HDI tertile. EMS, emergency medical services; HDI, Human Development Index.

Prehospital phase of care

When asked for the most common reasons for delays in patients arriving to hospital following initial injury, prehospital transport and prehospital care were cited by respondents as common issues across all HDI tertiles (figure 2). While similar barriers were reported by both the lower HDI tertile and middle HDI tertile respondents, regional trauma system care and patient instability were issues reported uniquely by the respondents in the upper HDI tertile.

Figure 2. The most common reasons reported by respondents for delays in patients arriving to hospital following their initial injury, numbered 1 to 5, stratified by HDI tertile. EMS, emergency medical serviEmergency Medical Services; HDI, Human Development Index.

There was significant variation across HDI tertiles in the presence of a trauma team to assess seriously injured patients on arrival to hospital (χ² for trend, p<0.001), with the trauma team present ‘all of the time’ in 77.1% (64 of 83 respondents) of upper HDI tertile centres, compared with 60.0% (30 of 50 respondents) of middle HDI tertile centres and 37.0% (20 of 54 respondents) of lower HDI tertile centres. Similar trends were observed regarding the presence of a doctor with formal training in providing trauma care (p<0.001), with 66.3% (55 of 83 respondents) in the upper HDI tertile stating this would occur for the majority of cases, compared with 40.0% (20 of 50 respondents) in the middle tertile and 31.5% (17 of 54 respondents) in the lower HDI tertile.

Preoperative and intraoperative phase of care

The availability of several key services was significantly higher in the upper HDI tertile compared with the middle and lower tertiles. Specifically, CT imaging services (χ² for trend, p<0.001), pathology services (p<0.001) and blood transfusion services (p=0.009) were all more available in the upper HDI tertile, with a similar pattern also evident for laparoscopic surgery (p<0.001) and interventional radiology (p<0.001).

The most cited factor delaying transfer to the operating theatre for a trauma laparotomy was the lack of operating theatre availability (figure 3). Indeed, respondents from the middle HDI tertile and upper HDI tertile described the same five most common delays across these settings, while the lack of blood product availability and patient finances were more commonly cited by the lower HDI tertile respondents. A proportion of centres reported no delays in the transfer of a patient requiring a trauma laparotomy to theatre, with an increasing proportion from the lower HDI tertile respondents (5 of 54 centres, 9.3%) through to upper HDI tertile respondents (19 of 83 centres, 22.9%; χ² for trend p=0.027).

Figure 3. The most common reasons reported by respondents for delays in getting patients to the operating theatre for a trauma laparotomy, numbered 1 to 5, stratified by HDI tertile. EMS, emergency medical serviEmergency Medical Services; HDI, Human Development Index.

The availability of general surgeons (χ² for trend, p=0.515), orthopaedic surgeons (p=0.171) and obstetricians and gynaecologists (O&G, p=0.676) was equivalent across HDI tertiles (figure 4), when comparing a high availability (present ‘all of the time’ or ‘most of the time’) versus a low availability (present ‘some of the time’ or ‘never’). However, for the surgical subspecialities (paediatric surgery, neurosurgery, trauma surgery, plastic surgery, vascular surgery and cardiothoracic surgery), an increase in high availability was associated with increasing HDI tertile (p<0.001), from 48.2% in the lower HDI tertile to 58.0% in the middle HDI tertile and 64.7% in the upper HDI tertile, respectively (figure 4). Similarly, respondents from upper HDI tertiles reported a high availability of anaesthetists (p=0.003) and intensivists (p<0.001), respectively, compared with the middle HDI tertile and lower HDI tertile.

Figure 4. The reported availability of each surgical specialty, stratified by HDI tertile. HDI, Human Development Index; O&G, Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Respondents were asked to report the number of employed staff and the number of operations performed at their respective hospitals. The ratio of operations performed to general surgeon numbers was the highest in the lower HDI tertile (3.1:1) and middle HDI tertile (3.4:1), compared with the upper HDI tertile (0.9:1, p=0.001). The ratio of operations performed to anaesthetist numbers was also the highest in the lower HDI tertile (7.0:1) and middle HDI tertile (7.6:1), with a 10-fold difference compared with the upper HDI tertile (0.7:1, p=0.006). A higher proportion of patients presenting to lower HDI tertile hospitals (30.0%) were reported to undergo surgery, compared with those presenting to middle (23.0%) and upper (22.3%) HDI tertile hospitals; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.142).

Post-operative and rehabilitation phase of care

We defined an intensive care unit (ICU) as a unit ‘capable of offering at least mechanical ventilation, or capable of offering both renal replacement therapy and central vasopressor/inotrope administration’ and a high dependency unit (HDU) as a unit ‘capable of offering higher nurse to patient ratios (than the standard hospital inpatient ward) and is capable of offering continuous monitoring of physiology’. There was a high degree of access to an ICU reported by respondents across all strata, with 87.0% in the lower HDI tertile, 98.0% in the middle HDI tertile and 97.6% in the upper HDI tertile. There was more marked variation in the access to an HDU, with significant increase reported from respondents in the lower HDI tertile at 50.0%, through to the middle HDI tertile at 60.0% and the highest in the upper HDI tertile at 72.3% (χ² for trend, p=0.008).

When asked about the main barriers to ICU admission for a patient following a trauma laparotomy, the most common response across all HDI tertiles was limited bed availability. Of note, 16.7% of respondents in the lower HDI tertile described a lack of ICU equipment, such as ventilators, as a barrier; however, this was much less commonly reported by middle HDI tertile and not at all by upper HDI tertile respondents. A proportion of centres reported no barriers to ICU admission, with an increasing proportion from the lower HDI tertile respondents (3 of 54 hospitals, 5.6%) through to upper HDI tertile respondents (25 of 83 hospitals, 22.9%; χ² for trend, p<0.001).

Of the most common causes of postoperative morbidity among patients undergoing a trauma laparotomy, infection was the most commonly cited across all HDI tertiles (online supplemental material). Of note, the lack of resources and nutrition was cited as the second and third most common causes of postoperative morbidity by respondents in the lower HDI tertile.

The availability of physiotherapists (χ² for trend, p<0.001), occupational therapists (p<0.001) and dietitians (p=0.001) all showed increasing availability in the upper HDI tertile, when comparing high availability (present ‘all of the time’ or ‘most of the time’) versus low availability (present ‘some of the time’ or ‘never’). In particular, in the lower HDI tertile, respondents reported a high availability of physiotherapists in 51.9% of cases (28 of 54 respondents), of occupational therapists in 14.8% of cases (8 of 54 respondents) and of dietitians in 35.2% of cases (19 of 54 respondents).

Discussion

In this global survey of 187 hospitals from 51 countries that provide care for patients receiving trauma care, sizeable discrepancies were clear in the infrastructure, staffing and processes available across the patient pathway. It was evidenced that those in lower resource settings face more financial and procurement-related issues in an attempt to provide optimal trauma care, while those in higher resource settings encounter more system and process-level issues. Hospital-based care also appears to develop the fastest out of the three phases of trauma care, with the challenges of hospital-based care in the middle HDI tertile more analogous to the upper HDI tertile than the lower HDI tertile. However, certain barriers to care appear to be universal across settings, such as delays in prehospital care and the lack of theatre capacity. Obstacles to care highlighted in higher resource settings but not lower resource settings, such as the lack of subspecialist services, should not be seen to be absent in lower resource settings, but rather that presently they are not limiting care to the extent that other factors are. This work highlights clear targets for capacity building in trauma care from across the patient pathway; however, given the breadth of issues highlighted, a systems approach to this problem is essential if the overall standard of global trauma care is to be improved.

Effective prehospital care is essential in delivering good trauma outcomes; trauma is a time-sensitive condition and the timely delivery of definitive management is reliant on efficient prehospital care processes.28 Indeed, prehospital care was the phase of care that respondents in the lower HDI tertile reported that needed the most improvement. The lack of formal prehospital care in LMICs has been well described,9 10 29 resulting in delays to crucial investigations and interventions. However, such barriers go beyond the actual infrastructure; individuals in many settings will delay seeking initial care due to a variety of societal, cultural or financial factors, instead often seeking alternative routes before engaging with hospital-level care.30,32 Ultimately, financial barriers remain a great obstacle to accessing trauma care in many low-resource settings, and innovative approaches such as community-based health insurance must be developed to combat this key issue.33 Respondents from lower and middle HDI tertiles in our survey highlighted a trio of core concerns in this regard, with a lack of formal emergency medical services, a lack of health education and financial constraints as major barriers to prehospital care, and a recognition of the interplay between these factors is key to designing prehospital care systems in low-resource settings. Moreover, the rural-urban divide in prehospital care must be taken into consideration; rural areas are known to suffer from worse outcomes in trauma across all HDI tertiles34,38 and long transfer times, as a result of geographical distance or poor road infrastructure, were reported as issues across all tertiles, emphasising the need for equitable resource distribution across regions.

While barriers to effective prehospital care were consistent across lower and middle HDI tertiles, the predominant limitations in intrahospital care among lower HDI tertile hospitals were not seen in either the middle HDI or upper HDI tertile hospitals. Instead, middle HDI tertile centres reported similar issues as upper HDI tertiles, suggesting potentially analogous processes of care and that intrahospital care may have been more consistently invested in, compared to other phases of trauma care. Hospitals are arguably a more attractive target for investment in healthcare than the community, with a hospital being a clearly defined healthcare environment whereby the investment of resources provides a more visible and easily measurable improvement to care, as opposed to any development in the care provided within a community. However, the different phases of care are complementary and investment across all three is needed to maximise the benefit from improvement to any individual phase. Across all HDI tertiles, a lack of operating theatre availability and time to diagnosis were both reported as top causes of delay to laparotomy—the commonality of these factors across settings suggests that they could serve as metrics for benchmarking trauma care in future studies. General surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons and obstetricians play a key role in the management of trauma patients, and encouragingly they were reported to be available to manage trauma patients to a similar degree across tertiles. However, for anaesthetists, subspecialist surgeons and intensivists, this was not the case, with a clear trend in availability with increasing HDI tertile. It should also be noted that task-shifting, of both anaesthesia and surgery, is a key aspect of surgical care in low-resource settings and helps to mitigate the shortage in the healthcare workforce39; as an example, a recent study from sub-Saharan Africa found that over half of all operations within a region had been performed by non-specialist physicians.40 The provision of subspecialist surgical services should not be equated to the presence of subspecialist surgeons, and the provision of anaesthesia should not be equated to the presence of physician anaesthetists. Also of particular note was the higher number ratios of operations to general surgeons and anaesthetists in the lower and middle HDI tertiles, up to 3-fold and 10-fold respectively, compared with their upper HDI counterparts; this might represent variations in employed doctors per institution, an increased burden of patients, differences in management practice or the availability of diagnostics. Regardless, the severe shortage of surgeons and anaesthetists in the global south is well recognised5 and further worsened by migration of physicians from the global south.41 42 Therefore, staff retention must be recognised as a key part of trauma system design across all settings.

Infection was the most commonly reported cause of postoperative morbidity across HDI tertiles. If extrapolated to trauma more broadly, this represents a major area of concern across all global populations, especially in the context of rising antimicrobial resistance, with the caveat that cause and treatment of such infections are likely to differ across settings. Moreover, while ICU capabilities were reported to be available across HDI tertiles, a relative lack of HDU availability in the lower and middle HDI tertiles suggests less resilience present in these systems.43 The rehabilitation phase of care is an often under-researched aspect of trauma care, yet it was felt to be the phase of care most in need of improvement by respondents in the upper HDI tertile. This was further reinforced by the lack of allied health professionals reported, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and dietitians, especially in the lower and middle HDI tertiles.44 Many lower resource settings lack appropriate programmes to train these staff,45 and improving trauma care standards is an area that requires urgent attention. The economic burden of trauma globally is enormous,13 14 and rehabilitation is a key phase of care to ensure that people are able to return to their preinjury functional status and minimise the financial impact of injury at individual, local and national scales.

The opportunity to assess trauma care across a large number of settings with different contexts in terms of resource availability, healthcare staffing and geographical factors provides insight into the development of trauma systems. While previous studies have examined the maturation of trauma systems that have been formally implemented through government policy in high HDI countries,46 47 there are few previous literature studies examining the development of heuristic trauma systems in lower resource settings. We have identified a number of common barriers to care between different HDI tertiles across the different phases of trauma care (figure 5). Respondents from lower and middle HDI tertiles reported a number of shared challenges in the delivery of prehospital and rehabilitation care; however, the responses from those in the middle HDI to their intrahospital phase of care suggest their provision here aligns more closely with the upper HDI tertile. Many of the respondents from the middle and upper HDI tertiles cited intrafacility issues and a lack of regional trauma systems as limiting factors for care as they become resource replete, compared with more financial and procurement-related issues raised by the lower HDI tertile respondents. While there is a clear need for investment in healthcare across all phases of care, this cannot be felt to be a panacea for the issues described in this study, as systems-level and process-level issues were clearly evident in more developed regions. Different facets of trauma must be planned and coordinated to ensure that patients feel the maximum benefit of the available healthcare resources.

Figure 5. Themes across trauma systems in different HDI tertiles in prehospital, in-hospital and postoperative care and rehabilitation phases of care. EMS, emergency medical serviEmergency Medical Services; HDI, Human Development Index; ICU, intensive care unit.

Strengths and limitations

This study has surveyed a large number of hospitals that provide trauma care worldwide across a variety of settings, highlighting clear themes and areas for further work. The strengths of this study lie in the diversity of trauma systems its respondents work in, a maximal response rate received and the exploration of the complementary phases of trauma care in these diverse systems. However, the study does come with certain limitations. Many of the participating hospitals were urban and tertiary-level facilities; therefore, caution must be taken in interpreting this work for more rural settings, which are often the most marginalised in healthcare.5 11 48 Rural facilities play a key role in the care of injured patients in low-resource settings, and more work is needed to describe how the processes occur in the care of trauma patients in these hospitals. Due to the inclusion criteria of the main study,18 certain questions in this survey referred to trauma laparotomy patients specifically, potentially limiting the generalisability of these responses to all-type trauma patients. The care of patients with other types of injuries, such as fractures or traumatic brain injuries, is likely to be influenced by other factors not captured in this survey. Additionally, as the survey was responded to by local clinicians, certain responses may be vulnerable to reporting bias; while this may be suitable for broadly characterising trauma care, it is not a replacement for prospective, granular data that are generated by trauma registries. In order to provide a comparison between resource settings, we have performed a comparison between HDI tertiles; however, each HDI tertile will encompass a vast range of trauma systems that differ significantly in need, access and quality, and such disparities will occur at national, regional and local scales.

Conclusion

In this study, we have surveyed trauma care across 187 centres in 51 countries and have demonstrated a broad variation in design, implementation and resource availability. Respondents highlighted the challenges in delivering prehospital care and rehabilitation especially in lower and middle HDI tertiles, with intrahospital care appearing to develop preferentially over other phases of care. Certain barriers were ubiquitous across all settings, such as long transfer times, lack of operating theatre availability, delays to diagnosis and postoperative infection, and these common features of trauma care could potentially be used to develop future benchmarks of trauma care. This survey highlights the need for carefully planned investment in trauma care that enables provision of all three phases of care, with coordination of resources to maximise patient benefit.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the following groups for their support throughout the study: European Society for Trauma and Emergency Surgery (ESTES); Sociedad Mexicana de Medicina de Emergencia; Futur Médecin Généraliste; Life & Limb; National Trauma Research and Innovation Collaborative (NaTRIC); Moynihan Academy; Global Anaesthesia, Surgery and Obstetric Collaboration (GASOC); Royal College of Surgeons of England; Cambridge Public Health; the NIHR Global Health Research Group on Acquired Brain and Spine Injury; and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Footnotes

Funding: MFB is funded by the Royal College of Surgeons Ratanji Dalal Research Fellowship and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). ZZ is funded from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82472243 and 82272180), the China National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2023YFC3603104), the Huadong Medicine Joint Funds of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LHDMD24H150001), the China National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2022YFC2504500), a collaborative scientific project co-established by the Science and Technology Department of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the Zhejiang Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. GZY-ZJ-KJ-24082), the General Health Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province (No. 2024KY1099), the Project of Zhejiang University Longquan Innovation Center (No. ZJDXLQCXZCJBGS2024016) and Wu Jieping Medical Foundation Special Research Grant (320.6750.2024-23-07). LH, PH and TB are funded by the NIHR ref: NIHR132455 using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research; the views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government. PH is further supported by the National Institute for Health Research (Global Neurotrauma Research Group, Senior Investigator Award, Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Handling editor: Henry E E Rice

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by the Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE.2023.119). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Contributor Information

on behalf of the GOAL-Trauma Collaborative:

Aiman Aamir, Ivan Abbott, Ward Abboud, Anwar Abdalla Mohamed Abdalazeez, Mohamed Abdalla, Mohamed Abdalla, Mojtaba MohammedAlmamoon Abdallah, Sondous Abdelaal, Omar Abdelfattah, Hossam Ibrahim Abdelhady, Mohamed Abdelhady, Sarah Magdy Abdelmohsen, Abdishakur Mohamed Abdi, Abdihakim Elmi Abdishakur, Akanni Bolaji Abdulazeez, Marwa Abdulkareem, Iddrisu Tidoo Abdull-Karim, Ali Hasan Abdulla, Makama Adamu Abdullahi, Hager AdlyMohamed Aboelfadl, Alaa Abdeltawab Abouammar, Ahmed Abouelnaga, Galal Abouelnagah, Hamdoon Abu-Arish, Amr Salah AbuSuliman, Ömer Faruk Acar, Emmanuel Acquah, Salma Adam, Auwal Adamu, Bashiru Mutiu Adebayo, Abanob Adel, Olalekan Adepoju, Ovuo Adolphus, Nii Ama Adu-Aryee, Nelson Kosi Affram, Suresh Agarwal, Rona CansuKavar Ağcabay, Thomas Agyen, Kwasi Agyen-Mensah, Zakaruyyah Shaheed Ahmad, Mohammad Al Ahmad, Elaf Ahmed, Ihsan Ahmed, Hamza Ahmed, Nazir Ahmed, Shahzad Ahmed, Gamal MutwakilGamal Ahmed, Malaz KhalidYousif Ahmed, Abdulrhman AbdulmoneimKhalifa Ahmed, Mohamed SheikhHassanSh Ahmed, Marta Seid Ahmed, Ibrahim MutwakilGamal Ahmed, Abass Oluwaseyi Ajayi, Muhammad Akbar, Emmanuel Akpo, Merve Aktas, Faustin Awinbilla Akum, Arwa S. Alabide, Mohannad Marouf Aladawi, Saleh Husam Aldeligan, Alaa Nasib Aldirani, Marcos Alejo-Rivera, Maryam Alfa-Wali, Abdullah Alfandi, Mahamad AhmedAdam Alhadi, Mohamed Sherif Ali, Gokhan Alici, Bilal Alkas, Nawaf Hamad Almadi, Ahmad Almahjaa, Bayan Mohammad Alnaser, Amran Mohammad Alnaser, Abdulaziz Mohammed Alotaibi, Essiane Meva’a Aloys, Abdulaziz M. Alrwais, Nawaf AlShahwan, Malak M. A. Alsharif, Mohammad Alshraiedeh, Norah Mihmas Alsubaie, Yuksel Altinel, Michele Altomare, Estefania NikolleCardona Alvarez, Sara MadalenaCorreia Alves, Reem Alyahya, Mohamed Adel Amasha, Ahmed Amgad, Sonya Amin, Mohammed HammadJaber Amin, Jaber HamadJaber Amin, Fagbero Aminat, Habibu Aminu, Nayab Amir, Joachim Amoako, Mabel Amoako-Boateng, Antzoulas Andreas, Hasnaoui Anis, Yasantha Liyana Arachchi, Carolina Picasso Arias, Isabella Armento, Douglas Arthur, George Aryee, Ahmed Samy Ashour, Shahzad Asif, Maha Atef, Martín Avalos, Nashwa AwadEltom Awad, Ghina Awais, Gizem Kiliç Aydoğdu, Yunushan Furkan Aydoğdu, Nora Abdul Aziz, Elaf AdelHamdoun Aziz, Ibrahim AdelHamdoun Aziz, Yassir Al Azzawi, Ahmed YahiaMahadi Babiker, Mahmoud EssamSayedMohammed Badawy, Daniel Umugisha Baderhabusha, Mohamed Amgad Badr, Richard Ogirma Baidoo, Lovenish Bains, Samir AlbaseerHabiballh Bakhit, Sunder Balasubramaniam, Khuder Omar Ballan, Edoardo Ballauri, Ioannis Baloyiannis, Gerard Baltazar, Ee Jun Ban, Lasantha Bandara, Daniel Baraka, Ahmet Barcin, Emilie Barnes, Mohammed Bashir, Gary Bass, Ceri Battle, Bekena Lemessa Bayissa, Çisil Bayır, Nebiyou Simegnew Bayleyegn, Dina Bekhit, Anis Belhaj, Annamaria Di Bella, Sigrun Benediktsdottir, Valentin Bereshchenko, Katherine Cordero Bermudez, Andrew Bernstein, Aisha Masroor Bhatti, Margherita Binetti, Josué Rhukuze Birindwa, Lauren Blackburn, Muhammed Selim Bodur, Michael El Boghdady, Irini Bogiages, Ruggero Bollino, Andrea Bottari, Konstantinos Bouchagier, Ahmed Bouzid, Antoinette Bediako Bowan, Emre Bozlakoğlu, Jessica L. Brady, Olivia Braun, Luis Bravo-Cuéllar, Elma Bregaj, Adam Brooks, Joshua B. Brown, Nihat Bugdayci, Johannes JacobusPetrus Buitendag, Leta Dedefo Buta, Çağrı Büyükkasap, Kefas John Bwala, Onur Cakir, Elena Guillermina Caldani, Adnan Calik, Giacomo Calini, Obi Chukwunyere Callise, Francesca Cammelli, Andrea Campos-Serra, Burcu Canakci, Anne Carine Capois, Stefano Cardelli, Luca Carenzo, Clara LópezdeLermaMartínezde Carneros, Eliot Carrington-Windo, Carolina Cecchi, Maurizio Cecconi, Arif Burak Cekic, Martina Ceolin, Maurizio Cervellera, Mohamad K. Abou Chaar, Kamtone Chandacham, Allison Chang, Diego Chavez, Tianqi Chen, Chen Cheng, Brad Chernock, Narain Chotirosniramit, Isaac Chukwu, Stefania Cimbanassi, Stefano PieroBernardo Cioffi, Bulent Citgez, David Clarke, Rachel Coates, Rosa M. Contreras-Arias, Andy Conway-Morris, John Kyle Cook, Richard Crawford, Matt Creed, Lizzie Crudge, Diogo LebreiroMoreirada Cruz, Laura Fernandez-Gomez Cruzado, Merve Çuhadar, Rhona Cummine, Giulia Curreri, Oluwasina Dada, Ayat Mohamed AbdalzizDaffalla, Nawaz Ali Dal, Muhammad Daniyan, Juni Dasril, William Davalan, Ross Davenport, Justin Davies, Olga E. Davydova, Florence Dedey, Yisihak Shiferaw Degefu, Edward Delgado, Muhammed Taha Demirpolat, Chammika Desman, Kürşat Dikmen, Klevis Doçi, Christopher Dodgion, Agron Dogjani, Amaia Garcia Domínguez, Luca Di Donato, Jiangnan Dong, Reece Doonan, Hannah Dowel, Hang Du, Elena Dumitru, Nurseda Dundar, Tom Edmiston, Montha Edris, Raymond Atah Eghonghon, Andy Eglinton, Tanya Egodage, Oluwayemisi E. Ekor, Samuel Ekpemo, Ahmed El-Borollosy, Ahmed Elasad, Alaa Elbadrawy, Mohanad ElsafiMossaad Elbashier, Ali AbdelmonimMohamedElhassan Elbashir, Toka Elboraay, Abdalla Nasser Eldiasti, Basma Sharaf Eldin, Mohammed Eldoadoa, Mohamed Attia Elfadali, Mohamed S. Elgendy, Mariam Hatem Elgliand, Hazem Elhadidi, Ola Abdallah Eljizoly, Abdallah Elkhouly, Engy Elkoury, Dina Elmagdoub, Ayub Hassan Elmi, Asmaa Elmorshdy, Aesha Elmorshdy, Sara Elmorshdy, Abdelrahman Elmorshdy, Mahmoud Saad Elnadi, Roba OsamaMukhtarElnour, Mohey AldienAhmedElamin Elnour, Farah Elsaied, Mahmoud M. Elsayed, Mahmoud M. Elsayed, Ahmed Elshaboury, Abdalla Magdi Elshal, Sara Elsheikh, Mohammed Tageldin ElhadiEltahir, Zachary Englert, Uche Eni, Donald Tweneboah Enti, Gülçin Ercan, Beyza Izem Erdem, Muhammer Ergenç, Ahmet Sencer Ergin, Joshua Erhabor, Cenk Ersavas, Manar Essam, Begoña Estraviz-Mateos, Abdi Lemma Eticha, Kayahan Eyuboglu, Mohamed R. Ezz, Daniele Del Fabbrio, Komal Faheem, Gihad Shaman Fakhri, Kara Faktor, Oluleke Falade, Ge Fangxia, Raneen Farash, Ahmad Faraz, Fay FathimaImtiaz Fareed, Ayatallah Ahmed Farrag, Sunguralp Farsak, Rabika Fatima, Massimo Fedi, Filipa Carvas Feliciano, Fatih Feratoglu, RogérioBellini Figueiredo Filho, Francesco Fleres, Mariaceleste Colón Flores, Laura Fortuna, Eslam Fouda, Haoya Fu, Clotilde Fuentes-Orozco, Matteo Fumagalli, Jade Fyfe, Yasmena Gaber, Oussama Gaidi, Aditi Gaikwad, Elena Galindo, Stephen Gboya Gana, Feroz Ganchi, Fei Gao, Sophie Gasson, Nuno Gatta, Opeyemi Gbadegesin, Olaogun Julius Gbenga, Bisrat Kidane Gebremedhin, Jaclyn Gellings, Sandra Gelvez, Lidya Gemechu, Tigist Girma Gemechu, Nirav Ghandi, Sandro Giannessi, Angeles Giavarini, Simone Giudici, Hüseyin Göbüt, Ahmed K. Gohar, Rawan Mohamed Gomaa, Inês Carolino Gomes, Maria Gonsalves, Alejandro González-Ojeda, Nuri Emrah Göret, Stavros Gourgiotis, Chris Groombridge, Jeremy Grushka, Senyo Gudugbe, Ayaz Gul, Osman Bilgin Gulcicek, Taygun Gulsen, Sidra Gulzar, Kanchana Gunarathne, Kosala Gunasekara, Sivaraj Gunasekaran, Muhammet Gündal, Isaac Gundu, Ali Guner, Xuchang Guo, Araceli Rodríguez Gutiérrez, Emmanuel Yeboah Gyabaah, Musab Hafiz, Fayza Haider, Lucy Hall, Sedra Hamad, Ali Hamdan, Mohamed Eldiasti Hamed, Faiza Hameed, Nada Hany, Timothy Hardcastle, Shanmugaraj Harikrishanth, Hamza Haroon, Lilav Hasan, Abdullahi Said Hashi, Ammar Hegazi, Asmaa Maher AlbashaHejazi, Abiyere Henry, Abdullah Hilal, Lauren Holt, Ob-Uea Homchan, Moataz OsmanMahjoub Homida, Mohammed Hoque-Uddin, Sara-Jane Horne, Daniel Horner, Parker Hu, Michael Hughes, Phebe LimJen Hui, Halil Hussein, Chik Ian, María E. Ibarra-Tapia, Noon Ibrahim, Mohamed AbdEl-Rahman MohamedIbrahim, Ahmed Ibrahim, Shaker AbakerAdam Ibrahim, Awab HamdiDyaaeldin Ibrahim, David Bamidele Idowu, Ifeanyichukwu Emmanuel Ihedoro, Lambert Iji, Emmanuel Ikwutah, Aris Ioannidis, Nazish Iqbal, Mehmood Ishaq, Rami Ismail, Mohamed Abdihafid Issak, Ahmed Itaimi, Parkhomenko Ivan, Yasuhito Iwao, Rasha Jabari, Gavin Rubin Jacks, Zeeshan Muhammad Jaffer, Sarah Jamil, Aqsa Jawaid, Sharon Jay, Gayan Jayarathne, Bingumal Jayasundara, Kamal Jayasuriya, Hollie Jenkinson, Jeyapalan Jeyaruban, Guan Jian, Aminat Oluwabukola Jimoh, Lee Jingwen, Tidarat Jirapongcharoenlap, Tomasz Jodlowski, Hala SamiraMhd Othman, Joha MuhammadNur SyamimbinCheJohan, Ehdaa Kallas, Atahan Karaaslan, Haluk Kerim Karakullukcu, Sarah Kassis, Sergei Katorkin, Konstantina Katsiafliaka, Yang Ke, Daniel LeeJin Keat, Eyüp Kebapçı, Monty Khajanchi, Elnageh Khalf, Mariam Khalil, Omar Khalil, Soukat Ali Khan, Ghulam Younis Khan, Muhammad Faisal Khan, Tariq Hayat Khan, Sanya Ashraf Khaskheli, Shahida Khatoon, Rached Khelili, Feriha Fatima Khidri, Tiong Chiong Kian, Konstantina Kitsou, Connie KoayChia Ern, Rachel Koch, Karien de Kock, Anil TahaKodalak, Malin Kollind, Prokopenko Kostiantyn, Jessica Krizo, Hendrik Johannes Kruger, Vincent Kudoh, Varun Kumar, Sandesh Kumar, Yogesh Kumar, Philemon Kumassah, Nwanneka Louisa Kwentoh, Arthur Kwizera, Crystal Kyaw, Parkhomenko Kyrylo, Naadiyah Laher, Kokila Lakhoo, Sanee Lalani, Aitor Landaluce-Olavarria, César F. HuarotoLandeo, Estelle Laney, Andrew Leather, Quinston Lee, Vasileios Leivaditis, Francesca Leo, David Leon, David Leshikar, Yu-Kai Li, Jin Li, Leonid A. Lichman, Yee Siew Lim, Rayssa EduardadeMoura Lima, Sylvia Ling, Andrey Litvin, Jie Liu, Songqiao Liu, Heura Llaquet-Bayo, Saray Quinto Llopis, Nazia Lodhi, Carl Stephane Lominy, Jose Maria Lopez, Fernando López-Ortega, Kerl GiovanniPierreLouis, Kai Lu, Yanqiu Lu, Qi-Yu Lu, Wan-Ling Luo, Qiancheng Luo, Davide Luppi, Ongeziwe Lusawana, Federico Luvisetto, Simone Mackie, Mohie El-DinMostafa Madany, Michael Oluwaseun Magbagbeola, Fatima SalaheldinMohamedMahdi, Hussayn Mefreh Mahfouz, Ahmed AwadelkareemOmer Mahmoud, Moustafa El Mahrouki, Patrick Maison, Shumani Makhadi, Hana Waleed Makki, Remon Mamdouh, Thamaneeyan Manivannan, Hazem Reyad Mansour, Nawar Mansour, Juba Mansouri, Orla Mantle, Silvia Marchesi, Isabela deAlmeida Marcos, Rodrigo SalvadorPederzoli Marecos, Mohamed Ezzat Marei, Fady Markos, Elizabeth Marshall, Francesco Matarazzo, Setoni Mathibela, Reem Hani Matter, Georgios Matzakanis, Mohd Rashid Mazlan, Carmelo Mazzeo, Adele Mazzoleni, Iain McClure, Andrew McCombie, Matt McKenna, Gerard McKnight, Georgia Melia, Amir Iqbal Memon, Wong Chiew Meng, Carlos Pilasi Menichetti, Ahmed Menif, Philip Mensah, Taher Merchant, Minale Mengiste Merene, Serhat Meric, Amr Meselhi, Andrea Meza, Areeb Mian, Omolola Segunfunmi Michael, Adugna Getachew Mideksa, LouvenserMinthor Du Mingjun, Antoine Mulungano Mirindi, Nathan Mitchell, Jesuthasan Mithushan, Maeyane Moeng, Abd Elrahim Mohamadin, Abdulkadir Nor Mohamed, Ola Mohamed, Rashad G. Mohamed, Amr Mohamed, Basmala Mohamed, Aya MustafaAhmed Mohamed, Mohamed Elobeid ElaminMohamed, Suleyman Abdullahi Mohamed, Ali H. J. Mohammad, Mariam M. Mohammed, Feroza Mohammed, Ibrahim AwadOsmanMohammed, Alaa MohammedAli Mohammed, Ahmed TahirBadri Mohammed, Lugen OsamaYousef Mohammed, Shailesh Mohandas, Lebone Mohlala, Lilamarie Moko, Jenna Molinari, Erica Monati, Diogo Lopes Monteiro, Kirusha Moodley, Ramani Moonesinghe, Steffania Morales, Claudia Cristina LopesMoreira, Dimitrios Moris, Martin Tangnaa Morna, Mohammed ElsaidElseir Mostafa, Josias Nshimiye Muhoza, George Duke Mukoro, Francesk Mulita, Sophie Mundell, Javaria Muneer, Ambreen Munir, Anna Muñoz-Campaña, Abdelnour AliAhmed Musa, Razaz Mahde EsmaeelMusa, Aya Musbahi, Asad Mushtaq, Muhammed Mustapha, Adam Rajab Mwinyi, Narious Naalene, Sumbul Nadeem, Rubab Nafees, Shanisa Naidoo, Ravi Naidoo, Syed Ali Naqi, Ashok Kumar Narsani, Mohammed Nassif, Angélica M. Nava-Franco, Sameena Naz, Ionut Negoi, Edward J. Nevins, YiJiang Ni, Hongying Ni, Phifer Nicholson, Laura Nicol, Adamu Bala Ningi, Daniel Nishijima, Believe Ozioma Nomayo-Oriabure, Michael Nortey, Alisia Nortjie, Abeer Kamil Noureldin, Josephine Nsaful, Bachelard CissaWa Numbe, Carlos M Nuño-Guzmán, Nchomboh McRyan Nwenasi, Chido Nyatsambo, Luis Fernando Pino, OConor O’Flynn, Maaz Obaid, Helen Odion-Obomhense, Cosmas Okeke, Kenneth Okpokiri, Boladuro Emmanuel Olawale, Abdirahman Ahmed Omar, Ahmed MoawiaBasher Omer, Scott Osahon Omorogbe, Bogdan Oprita George Oosthuizen, Philippa Orchard, Emmanuel Osamwonyi Oriabure, Steve-Nation Oriakhi, Jesús J Orozco-Camacho, Ahmet Batuhan Oruc, Ruth Bossuet Osias, Abdulrahman Osman, Kemunto Otoki, Majd Oweidat, Sam Owen-Smith, Frank Owusu, Emmanuel Owusu Ofori, Ömer Faruk Özkan, Adnan Özpek, Hamdi Ozsahin, Matteo Pagani, Simona Pangallo, Dimitra Papaspyrou, Roberto Martínez Pardavila, Muzaffar Parker, Robert Parker, Dan Parry, Giovanni Pascale, Mohamed Quraish Patel, Stavro Paulo, Phil Pearce, Dilan Pehlivan, Nadia Pellicano, Aintzane Lizarazu Perez, Davina Perini, Zane Perkins, Benedetta Pesi, Patrizio Petrone, Annalisa Piccolo, Agustina Pienovi, Lavinia Piombetti, Hassan Pirhay, Noah Pirozzi, Nami Ünal Polat, Iñigo Augusto Ponce, Michael Powar, Yavuz Poyrazoğlu, Ponnuthurai Pratheepan, Tiffany L. Pratt, Nick Preda, Riaan Pretorius, Mihiri Priyangani, Sarah Provencher, Rudo Pswarayi, Zhang Qi, Bayan Qneiby, Elizabeth Quartson, Francis Quenin, Olivia Quinn, Muhammed Ali Rahimi, Ganiyu Adebisi Rahman, Sajith Ranathunga George Ramsay, Aman Rawal, Howard Read, Eder LeonardoCaceres Reatiga, Nicolas Jokshan Reddy, Frédeline Immacula Régis, Francesco Renzi, Luis F. Reyes, Karyna Reyes, Wassim Riahi, Claire Victoria Riley, Giacomo Ripamonti, Mario NapoleónMéndez Rivera, İnas Rizaoglu, Jacob Robinson, Viraj Rohana, Felipe JRomo-Pérez, Harrison Roocroft, Matteo Rottoli, Lecia Chen Rouwen, Wang Ruilan, Mostafa Foly Saadawi, Esraa Saber, Ahmed Saidani, Aitor Sainz-Lete, Abdurrahman Hashi Salad, Mohamed Salah, Raoof Saleh, Esraa Y Salem, Simona Di Salvatore, Fatudimu Oluwafemi Samuel, María Paula Sánchez, Sergio Jiram VázquezSánchez, Natalia Sánchez-Thompson, Joudy Sandouk, Ahmet Necati Şanli, Mauro Santarelli, Leonor deCostaLourençoe ÁviladosSantos, Imad-ud-din Saqib, Samer Sara, Kemal Tolga Saraçoğlu, Chamaidi Sarakatsianou, Khalid Sarhan, Lodovico Sartarelli, Mohd HadyShukriAbdul Satar, Kota Sato, Alperen Ibrahim Sayar, Noureldin Mahmoud Sayed, Alparslan Saylar, Cosmo Scurr, Hakeem Seidu-Aroza, Ziad Selim, Mekonnen Feyissa Senbu, Giuseppe Sera, Andreev Pavel Sergeevich, Mónica Serrano-Navidad, Yannick Nordín Servín, Mohamed Magdy Shaapan, Katherine Shafer, Mahruhk Shafique, Shiraz Shaikh, Mariam Anwer Shaldan, Ghina Shamsi, Osama Al Shaqran, Omar A Sharaf, Wafaa Shehada, Munther DM Shehada, Nirman Shehzad, Kenneth ChunKok Sheng, Wegene Tadesse Shenkutie, Mai Mohamed Sherif, Hussayn Shinwari, Teresa Sinicropi, Stanislav Smoliar, Yalçın Sönmez, André LuisSilvadeSousa, Annabel Stafford, Nichole Starr, Eya Mvondo Stephane, Daniel Stephens, Christopher Michael FranciscoStrong, Paula Strong, Duminda Subasinghe, Vitus Nduka Sunday, Fiona Sweeney, Benali Tabeti, Hosam IbrahimAbdelhamid Taha, Heba Taher, Collins Takyi, Altaf Ahmed Talpur, Daniel Tamatey, Jay Roe Tan, Yousef Tanas, Jiyan Tang, Saad Tariq, Carla Tasca, Birhanu Tasew, Ibtesam Tasleem, John Taylor, Amanda Teichman, Ramazan Kubilay Tekcan, Erdinç Tekel, Yahsze Teo, Pavel Tereshchenko, Marco Tescione, Rachel Thavayogan, Jerry GooTiongThye, Anisse Tidjane, Tim Fabrice Tientcheu, Osias Tilahun, Abel Wondewosen Tilahun, Maximiliano Titarelli, Khalid Tolba, Larissa CristinaSoaresBarboza de Toledo, Valeria Tonin, Serdar Topaloglu, Hüsna Tosun, Racem Trigui, Teo Li Tserng, David Keya Tsongo, Cem Tuğmen, Korhan Tuncer, Gizem Kılınç Tuncer, Hayaki Uchino, Omar Ugas, Rindi Uhlich, Ikram Din Ujjan, Linus Ukwumonu Ukwubile, Mehmet Ulusahin, Serdar Ünlü, Tevfik Kıvılcım Uprak, Kisi Urgessa, Mehmet Arif Usta, Ludovica Vacca, Garantzioti Vasiliki, Sebastián E. Vélez, Francois Viljoen, Rosita De Vincenti, Diego Visconti, Angeliki Vouchara, Paul Vulliamy, Rodayna Wael, Saleh Al Wageeh, Howard Wain, Christopher Wakeman, Laura Walker, Jing Wang, Zhengquan Wang, Nan Wang, Shengfeng Wang, Qing-Bo Wang, Kaixuan Wang, Ali Muhammad Waryah, Mahtab Washdil, Marc Ong Weijie, Lauren Wilson, Githma Wimalasena, Sagara Wimalge, Devorah Wineberg, Jared Wohlgemut, Christopher Wolff, Yen Sin Wong, Evan Wong, Theodore Wordui, Changde Wu, Lim Woan Wui, Liu Xiao, Keliang Xie, Fang Xingming, Teoh Yu Xuan, Teoh Chia Xuan, Li Xueqi, Azhar AliHamoud AbdoAlYafrosi, Mohamed Musa Yassin, Erkan Yavuz, Aydın Yavuz, Büşra Yeşilova, Banu Yigit, Ali Cihat Yildirim, Yonas Yilma, Mehmet Yilmaz, Mabel WongTze Ying, Oloruntoba Yinka, Mehmet Arda Yıldırım, Susan Yoong, Omar Tarek Younes, Ibrahim Mohamed Younes, Zubair Ahmed Yousfani, Mariam Youssef, Helen Yu, Ewan Yung, Dina Zahran, Zaidi Zakaria, Andee Dzulkarnaen Zakaria, Julio Zeballos, Helmi Zebda, Alaa Mohamed Zeid, Lamees AdilAbdulbaqi Zeinalabedeen, Mahmut Zenciroglu, Sezgin Zeren, Jun Zhang, Zhongheng Zhang, Haoyue Zhang, Zheqing Zhang, Tian Zhaoxing, Ryan AngMing Zhi, Mingkai Zhou, Aya Ziada, Maurizio Zizzo, Mohamad NurFirdausBin Zulkifli, Michael F Bath, Joachim Amoako, Katharina Kohler, Charlotte Hammer, Abdullahi Said Hashi, Zhongheng Zhang, Monty Khajanchi, Daniel Umugisha Baderhabusha, Luca Carenzo, Max Marsden, Raoof Saleh, Eder Caceres, Carlos MNuño-Guzmán, Tom Edmiston, Laura Hobbs, Brandon G. Smith, Peter Hutchinson, Zane Perkins, Thomas G Weiser, Timothy C Hardcastle, and Tom Bashford

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Malekpour M-R, Rezaei N, Azadnajafabad S, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of injuries, and burden attributable to injuries risk factors, 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Public Health (Fairfax) 2024;237:212–31. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2024.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Injuries and violence: the facts 2014. 2014. [09-Jul-2025]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241508018 Available. Accessed.

- 3.Global alliance for care of the injured. [05-Aug-2025]. https://www.who.int/initiatives/global-alliance-for-care-of-the-injured Available. Accessed.

- 4.Edmiston T, Bath MF, Ratnayake A, et al. What Is the Need for and Access to Trauma Surgery in Low‐ and Middle‐Income Countries? A Scoping Review. World j surg. 2025;49:1928–40. doi: 10.1002/wjs.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet. 2015;386:569–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mock C, Arafat R, Chadbunchachai W, et al. What World Health Assembly Resolution 60.22 means to those who care for the injured. World J Surg. 2008;32:1636–42. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gosselin RA, Charles A, Joshipura M, et al. Disease control priorities, third edition (volume 1): essential surgery. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2015. Surgery and trauma care; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bashford T, Clarkson PJ, Menon DK, et al. Unpicking the Gordian knot: a systems approach to traumatic brain injury care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e000768. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattarai HK, Bhusal S, Barone-Adesi F, et al. Prehospital Emergency Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2023;38:495–512. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X23006088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinder F, Mehmood S, Hodgson H, et al. Barriers to Trauma Care in South and Central America: a systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2022;32:1163–77. doi: 10.1007/s00590-021-03080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alayande B, Chu KM, Jumbam DT, et al. Disparities in Access to Trauma Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Narrative Review. Curr Trauma Rep. 2022;8:66–94. doi: 10.1007/s40719-022-00229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao TE, Chu K, Hardcastle TC, et al. Trauma care and its financing around the world. J Trauma Acute Care Surg . 2024;97:e60–4. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham SM, Chokotho L, Mkandawire N, et al. Injury: a neglected global health challenge in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13:e613–5. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(25)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wesson HKH, Boikhutso N, Bachani AM, et al. The cost of injury and trauma care in low- and middle-income countries: a review of economic evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:795–808. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds TA, Stewart B, Drewett I, et al. The Impact of Trauma Care Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Annu Rev Public Health . 2017;38:507–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cote MP, Hamzah R, Alty IG, et al. Current status of implementation of trauma registries’ in LMICs & facilitators to implementation barriers: A literature review & consultation. Indian J Med Res. 2024;159:322–30. doi: 10.25259/IJMR_2420_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bath MF, Amoako J, Kohler K, et al. Global variation in patient factors, interventions, and postoperative outcomes for those undergoing trauma laparotomy: an international, prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13:e1837–48.:S2214-109X(25)00303-1. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(25)00303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bath MF, Kohler K, Hobbs L, et al. Evaluating patient factors, operative management and postoperative outcomes in trauma laparotomy patients worldwide: a protocol for a global observational multicentre trauma study. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e083135. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-083135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World bank country classifications by income level for 2024-2025. [09-Jul-2025]. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025 Available. Accessed.

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark D, Joannides A, Adeleye AO, et al. Casemix, management, and mortality of patients rreseceiving emergency neurosurgery for traumatic brain injury in the Global Neurotrauma Outcomes Study: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:438–49. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guidelines for essential trauma care. [09-Jul-2025]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-essential-trauma-care Available. Accessed.

- 24.ACS Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. [05-Jan-2025]. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/quality/verification-review-and-consultation-program/standards/ Available. Accessed.

- 25.Human Development Reports Human development report 2023-24. [11-Mar-2025]. https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2023-24 Available. Accessed.

- 26.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs . 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JK. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2008. Relativism. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron PA, Gabbe BJ, Smith K, et al. Triaging the right patient to the right place in the shortest time. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:226–33. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mould-Millman N-K, Dixon JM, Sefa N, et al. The State of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems in Africa. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32:273–83. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X17000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mould-Millman N-K, Rominski SD, Bogus J, et al. Barriers to Accessing Emergency Medical Services in Accra, Ghana: Development of a Survey Instrument and Initial Application in Ghana. Glob Health Sci Pract . 2015;3:577–90. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yempabe T, Edusei A, Donkor P, et al. Factors affecting utilization of traditional bonesetters in the Northern Region of Ghana. Afr J Emerg Med. 2021;11:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraser MS, Wachira BW, Flaxman AD, et al. Impact of traffic, poverty and facility ownership on travel time to emergency care in Nairobi, Kenya. Afr J Emerg Med. 2020;10:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eze P, Ilechukwu S, Lawani LO. Impact of community-based health insurance in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE . 2023;18:e0287600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kong V, Odendaal J, Sartorius B, et al. Civilian cerebral gunshot wounds: a South African experience. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:186–9. doi: 10.1111/ans.13846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuma P, Orsi R, Dunn J, et al. Traumatic injury and access to care in rural areas: leveraging linked data and geographic information systems for planning and advocacy. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19 doi: 10.22605/RRH5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleet R, Lauzier F, Tounkara FK, et al. Profile of trauma mortality and trauma care resources at rural emergency departments and urban trauma centres in Quebec: a population-based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028512. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel PD, Kelly KA, Chen H, et al. Measuring the effects of institutional pediatric traumatic brain injury volume on outcomes for rural-dwelling children. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2021;28:638–46. doi: 10.3171/2021.7.PEDS21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raatiniemi L, Liisanantti J, Niemi S, et al. Short-term outcome and differences between rural and urban trauma patients treated by mobile intensive care units in Northern Finland: a retrospective analysis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:91. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bognini MS, Oko CI, Kebede MA, et al. Assessing the impact of anaesthetic and surgical task-shifting globally: a systematic literature review. Health Policy Plan. 2023;38:960–94. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czad059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adde HA, van Duinen AJ, Sherman LM, et al. A Nationwide Enumeration of the Surgical Workforce, its Production and Disparities in Operative Productivity in Liberia. World J Surg. 2022;46:486–96. doi: 10.1007/s00268-021-06379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lantz A, Holmer H, Finlayson SRG, et al. Measuring the migration of surgical specialists. Surgery. 2020;168:550–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clemens MA, Pettersson G. New data on African health professionals abroad. Hum Resour Health. 2008;6 doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Health systems resilience toolkit: a WHO global public health good to support building and strengthening of sustainable health systems resilience in countries with various contexts. [03-Aug-2025]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240048751 Available. Accessed.

- 44.Hardcastle TC. Trauma Rehabilitation Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Adv Hum Biol. 2021;11:S1–2. doi: 10.4103/aihb.aihb_94_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agho AO, John EB. Occupational therapy and physiotherapy education and workforce in Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa countries. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15 doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0212-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levi A, Gupta S, Balasubramaniam S, et al. Lessons learned: The thematic analysis of eight countries with mature trauma systems. Injury. 2025;56:112260. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2025.112260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scharringa S, Dijkink S, Krijnen P, et al. Maturation of trauma systems in Europe. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2024;50:405–16. doi: 10.1007/s00068-023-02282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farmer PE, Kim JY. Surgery and global health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg. 2008;32:533–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9525-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.